Published online Dec 26, 2025. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v17.i12.112141

Revised: August 13, 2025

Accepted: November 11, 2025

Published online: December 26, 2025

Processing time: 159 Days and 3 Hours

As cardiovascular mortality continues to increase globally, percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) with stent placement stands out as a cutting-edge and highly effective treatment for severe cardiovascular diseases. However, the inherent invasiveness of any endovascular procedure introduces the risk of coronary vessel and myocardial damage.

To evaluate the utility of a novel electrocardiographic metric in detecting subtle myocardial injuries after coronary stenting.

This investigation was conducted in 2021 at the Kyiv Heart Institute of the Ministry of Healthcare of Ukraine. The study involved 23 patients who underwent PCI, each subjected to a meticulous preoperative examination. A paired measurement approach was employed, encompassing 3-minutes electrocardiogram (ECG) recordings both before and several hours following the operation, using a compact ECG device. Each pair of ECG underwent a thorough analysis, scrutinizing 240 primary and computed ECG parameters.

The analysis delineated a distinct subgroup exhibiting significant myocardial damage post-stenting. This subgroup was characterized by an older average age and more stents than their counterparts. Notably, a concurrent re

The newly devised electrocardiographic metric is a significant advancement in the early detection of myocardial damage following PCI, able to capture not only physiological but also psychoemotional changes.

Core Tip: The inherent invasiveness of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) introduces the risk of coronary vessel and myocardial damage. The aim of this study is to evaluate the utility of a novel electrocardiographic metric in detecting subtle myocardial injuries after coronary stenting. The study involved 23 patients who underwent PCI. A paired measurement approach was employed both before and several hours following the operation, using a proprietary electrocardiogram scoring system. The analysis delineated a distinct subgroup exhibiting significant myocardial damage post-stenting. The newly devised electrocardiographic metric proves to be a significant advancement in the early detection of myocardial damage following PCI.

- Citation: Chaikovsky IA, Dziuba DO, Kryvova OA, Malakhov KS, Romanchuk OP, Todurov BM, Loskutov ОA. Mild myocardial injury during percutaneous coronary intervention based on minor changes on electrocardiogram and heart rate variability. World J Cardiol 2025; 17(12): 112141

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8462/full/v17/i12/112141.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4330/wjc.v17.i12.112141

In recent decades, despite all the scientific progress, the number of people with cardiovascular diseases is increasing worldwide, mainly due to the equally worldwide dominating obesity epidemic. Cardiovascular mortality is relentlessly increasing with each passing year. It is responsible for approximately half of all lethal cases in the United States and Europe[1,2]. According to the American Heart Association data for last year, 7.5% of men and 6.2% of women suffer from coronary heart disease while 3% of citizens over the age of 20 experience myocardial infarction. In Ukraine, the number of patients with coronary heart disease is rapidly approaching 10 million, confidently taking the lead.

Therefore, it is clear that the need to improve methods for heart disease detection is extremely urgent. First of all, this applies to non-invasive methods that are the most accessible and safe. Analysis of the electrical activity of the heart is still the most common, affordable and cheapest method of objective examination of the heart. However, the sensitivity and specificity of routine electrocardiographic examination are not high enough. It is known, for example, that the resting electrocardiogram (ECG), assessed by its routine criteria, remains normal in approximately 50% of patients with chronic coronary heart disease, including during episodes of chest discomfort[3]. Improving diagnostics is possible only through implementing innovative technologies.

Among the other treatment options for severe forms of coronary heart disease, X-ray-controlled endovascular angioplasty with stent placement [i.e. percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI)] is one of the most effective and up-to-date. Introduction of new diagnostic and treatment options for cardiac patients, namely the increase in the number and quality of coronary artery stenting, presents new opportunities for the patients. The number of PCI procedures among all surgical interventions for cardiovascular diseases is increasing annually. According to the Medical Statistics Center of the Ministry of Healthcare of Ukraine, in 3 years (from 2014 to 2017) the number of endovascular interventions on heart arteries in Ukraine doubled[4].

However, any endovascular intervention on its own inevitably causes at least some damage to the coronary vessels and myocardium. The resulting PCI vascular trauma over a relatively short period (from weeks to months) triggers a complex inflammatory and reparative process that leads to endothelialization and formation of a neointimal pathological lining. According to histopathological findings, post stent implantation neointimal hyperplasia mainly consists of proliferating smooth muscle cells in the proteoglycan-rich extracellular matrix[5].

Therefore, since the first years of the widespread usage of X-ray-monitored endovascular coronary interventions, researchers have been aiming at developing diagnostic methods of myocardial damage and clearing up its prognostic value for mortality, recurrent need for revascularization, and myocardial infarction rate during the first several years after the intervention[6-8].

Nowadays, such damage is conventionally diagnosed by detecting perioperative elevation of myocardial biomarkers, namely CK-MB and troponin. Numerous studies about the link between elevated CK-MB and troponin levels and mortality and serious cardiovascular events (especially in the short-term perspective) were conducted, however the results of these studies were non-homogeneous. A lot of questions remain controversial, particularly the question of the CK-MB and troponin prognostic value ratio (the data about the significance of elevated troponin is especially controversial), threshold levels at which biomarker elevation gains prognostic value, and general perioperative indications for measuring these markers.

The uncertainty of these aspects and the desire to minimize costs results in most hospitals not conducting routine perioperative measurement of myocardial biomarkers. Even in the United States it is true for about 75% of hospitals. At the same time there is a trend of lower mortality and higher compliance in hospitals which regularly conduct perioperative measurement of the biomarkers mentioned above, reflecting the better overall quality of care in these hospitals.

In earlier studies on myocardial damage during endovascular coronary interventions the analysis of myocardial markers was combined with analysis of ECGs. First, the formation of pathological Q waves was studied. It was found that this wave rarely forms during endovascular angioplasty and coronary stenting. Lately it resulted in decreased interest in electrocardiography as a method of perioperative control of myocardial damage. In this context, the advanced analysis of ECG might be highly demanded.

The only way to increase the diagnostic value of ECG examination is the development of a proper information technology[9,10]. Such opportunities emerge due the creation of new metrics-numerical parameters by which one can assess the aspects of functioning of various human organs and systems that were inaccessible before. As a result, firstly, new ways to improve the diagnostic accuracy of a certain method within its traditional application scenarios are discovered and, secondly, familiar methods find unconventional uses in new areas. In this context, the innovative technology to analyze subtle changes of ECG was developed, aiming to make any ECG record conclusive[11,12].

The ECG scaling methodology, based on known approach of Z scoring[13] and its companion software are intended to quantify even very small shifts in the ECG signal[14]. The procedure entails: (1) Measuring as many ECG and heart rate variability (HRV) features as feasible; and (2) Locating each value along a continuum from physiological normality to overt pathology. Conceptually, this mirrors a standardized Z-score framework, in which numerical-typically point-based—scores are derived from distributions observed within a reference group; accordingly, computation requires the group mean and standard deviation[15].

It is obvious that individual ECG and HRV indicators reflect only partial aspects of the phenomenon under study; in addition, they can be multidirectional. Therefore, in order to draw a certain conclusion, a generalizing index is needed that synthesizes the effect of individual components. We have constructed several composite indices, starting with the most integral, designed to assess the functional state of a person in general, and up to more specific indices, designed to assess individual important aspects of the functional state.

The purpose of this study was to investigate the value of a new electrocardiographic metric for detecting subtle myocardial damage due to coronary stenting.

The study was initiated on May 1 2021 using the Kyiv Heart Institute of the Ministry of Healthcare of Ukraine facilities. Twenty-three patients were examined, with a mean age of 58.8 ± 11.2 years. All patients had undergone coronary artery stenting. Fifteen patients received PCI as a part of the acute Q-infarction treatment, including eight for chronic coronary heart disease (CAD), stable angina Canadian Cardiovascular Society class II-III. All patients received intraoperative analgosedation. The mean duration of the intervention was 40.2 ± 21.1 minutes, while the mean number of stents was 1.8 ± 0.9 (Supplementary material).

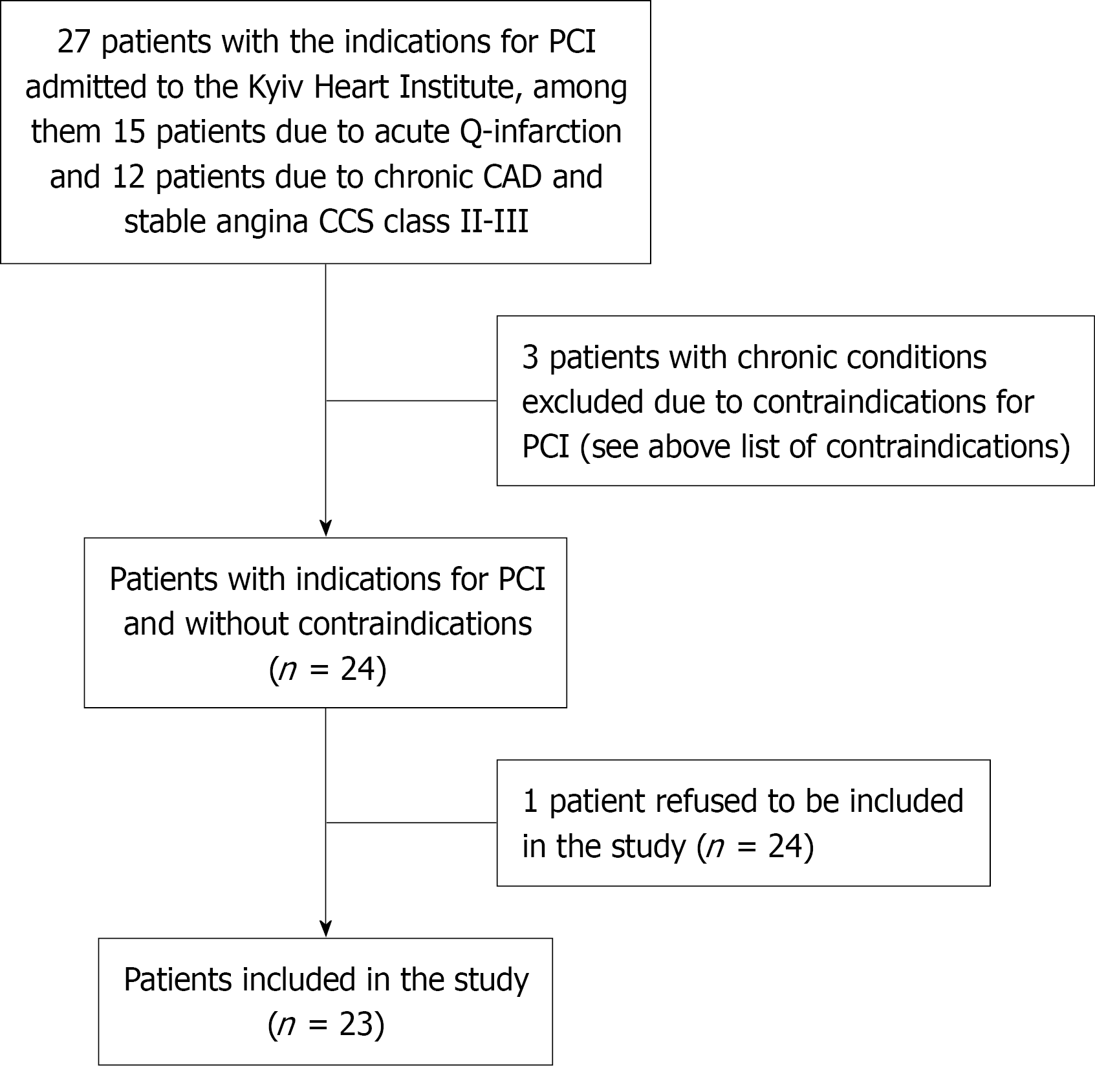

Exclusion criteria were as follows: Age over 75 years, liver dysfunction, progressive renal failure, acute and chronic infection, cardiac insufficiency, anemia, inflammation, peripheral vascular disease, pregnancy, suspected systemic thrombotic diseases, diabetes, cancer, other heart diseases, thyroid dysfunction, and autoimmune diseases. The process of patient enrollment is presented in Figure 1. The preoperative clinical and laboratory parameters as well as anthropometric values are presented in Table 1.

| Parameter | Value |

| Age (years) | 63.4 ± 5.3 |

| Sex (male/female) | 16/7 |

| BMI (kg/m²) | 28.4 ± 5.2 |

| AH | 20 (86.9) |

| Hb (g/L) | 136.3 ± 17.1 |

| Ht | 41.2 ± 4.4 |

| Тr (109/L) | 231.3 ± 38.2 |

| PTI | 93.4 ± 10.5 |

| Urea (mmol/L) | 6.4 ± 2.2 |

| Cr (μmol/L) | 94.7 ± 22.5 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 23 (100) |

| Heart failure | 21 (91.3) |

| Pulmonary hypertension | 7 (30.4) |

| Pulmonary disease | 9 (39.1) |

| Vessel disease | 12 (52.2) |

After surgical intervention, all patients underwent a modified computer ECG with its subsequent analysis using an innovative scaling method. Recently, an innovative ECG and HRV scaling method was developed by the Institute of Cybernetics of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine. Original software was also developed based on this method.

The program was developed on a hierarchical principle. It consists of four levels: (1) The lowest level is comprised of multiple separate parameters describing: (a) Various aspects of HRV; (b) Amplitude and time parameters, as well as shape of ECG waves; and (c) Presence of main rate, rhythm and sequence of myocardial contractions abnormalities (in other words-arrhythmias); (2) The second level is comprised of groups of related parameters with proximity to each other in the physiological sense; (3) The third level is represented by three integral sections, each representing a different aspect of cardiovascular system functioning that can be assessed through ECG, namely sections of regulation assessment, state of the myocardium, and arrhythmia diagnostics; and (4) The fourth and highest level is the collective integral criteria of the cardiovascular system’s functional status.

Multiple quantitative parameters registered by the program and used for analysis have different units of measurement (sec, mV and so on) or none at all. Naturally, there is a problem with converting data to be sufficiently compact and suitable for analysis and to also be convenient for making conclusions and decisions (i.e. switching to, for example, dimensionless parameters). In order to solve this, a functional scaling method is used. An interval scale from 0 to 100 notional points, divided into 4 equal intervals (0-25, 26-50, 51-75, 76-100) is used. These intervals match the four grades of status (i.e. normal, mild, moderate, and severe abnormalities respectively). All the while, the median value of the normal range of each particular parameter is in absolute units (e.g., in sec) and is taken as 100 points on the interval scale of functional status used. Thus, for each parameter, four intervals of absolute values are determined which match four equally wide (25 points each) intervals on the scale. During the next step, linear relations between discrete parameter values in absolute units and the corresponding amount of points for this discrete value are established within each interval. As a result, a linear correspondence scale between absolute parameter values and the amount of points on the functional status scale is obtained for each parameter. With the transfer to higher analysis levels the generalization and aggregation of information obtained on the previous level occurs. The composite index, present in this software, was formed based on the evaluation of conventional and original parameters of HRV as well as characteristics of ECG waves and complexes. The integral value is determined based on the values of individual parameters within each of the composite indices by averaging them. The integral value of the higher-level composite index is formed by averaging the integral values of the “lower” composite indices. The final results also presented in the frame of 100 points interval scale. The scale was developed based on the analysis of seven different databases of healthy volunteers, with a total sample size of about 17000 people. Various statistical tests were then carried out to demonstrate the homogeneity and robustness of the resulting matrix of results.

The suggested scaling method was invented precisely for solving practical problems and already has rather widespread applications[15-17] in solving various tasks in different areas of clinical medicine, sports medicine, and occupational health as well as in large-scale population studies[18]. This ECG scaling method is also used for the analysis of large ECG data arrays as part of Oxford Population Health study[19].

It is worth mentioning that the suggested scaling method includes both a series of adapted conventional algorithms for physician-led ECG assessment (cardiac rhythm abnormalities, morphological analysis of ECG figures) and ECG analysis algorithms that have proven useful in large international studies prognostic value for predicting serious cardiovascular events. Last but not least, analysis of psychoemotional state was performed through the HRV analysis using a modified McCraty algorithm (United States) based on a neurovisceral integration model[20].

In this study, paired measurements were used, namely 3-minutes-long ECG registration both prior to and several hours after the surgery. The examination was conducted using the fully certified “Cardio+P” innovative device, developed by V.M. Glushkov Institute of Cybernetics of the National Academy of Sciences and manufactured by “Metekol” LLC. Twenty-three pairs of ECGs were analyzed in total. Two-hundred and forty primary and calculated ECG parameters were analyzed for each ECG, among which there were eleven complex parameters (from 0 to 100 points).

Statistical processing of the results of this study was conducted using the STATISTICA 10 software package. Quantitative values were presented as the mean ± SD (in case of normal distribution). Anomaly detection in the data (the presence of outliers) was conducted using variance range criteria and the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. In order to test the hypothesis about the type of distribution, Shapiro-Wilk's W test (recommended for small samples) was used. Identification of homogeneous groups among patients was performed using the K-means clustering algorithm with a modified v-fold cross-validation scheme to determine the optimal number of clusters from the data. Cross-validation can be particularly useful for small datasets, since all available data are used as efficiently as possible for both training and validation. With v-fold cross-validation, the dataset is divided into V subsets. The clustering algorithm is re-applied by varying k from 1 to n on different subsets. One is used as a test set, the others for training. The results of the iterations are then compared using a plot of average distances vs different k (the Elbow method).

Repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to analyze the impact of the stenting factor. The effect of stenting was determined using the most commonly reported effect size estimation for ANOVA: The partial eta squared (ɳ2). For multiple comparisons by repeated-measures ANOVA of the mean composite indicators in the three patient subgroups, Bonferroni correction was used, as is customary for small numbers of groups.

The statistical significance of mean value change overall complex parameters prior to and after the stenting was tested using a t-test for two dependent samples (in case of normal distribution); in all other cases, a non-parametric Wilcoxon test was used. P value significance level was set to 0.05 in compliance to conventional medico-biological study guidelines.

Simple visual analysis of complex parameter diagrams prior to and after the stenting shows that the studied group is non-homogeneous, indicating the probable presence of separate clusters. Furthermore, significant individual differences were observed both in the values of complex indicators at the beginning of the study and in the trends of indicators, which is another sign of the heterogeneity of the group.

In order to identify homogeneous groups (clusters), the K-means cluster analysis method was applied. Homogenous groups were formed based on four criteria representing differences in complex (composite) parameters values prior to and after stenting. For this purpose, complex parameters that changed the most and met the conditions of K-means algorithm application (normal distribution) were selected. These parameters were the following: “Complex myocardial status parameter” (CP MS), “Complex functional status assessment” (CA FS), “Complex serious cardiovascular events risk assessment” (CA CVE), and finally “Universal score” (Uscore).

By using the K-means algorithm with 10-fold cross-validation, three clusters were identified that were most different from each other in such complex parameter changes as regulation (CA FS) and myocardial status (ΔCP MS). The usage of cross-validation allows for identification of the optimal number of clusters and minimizing the error of assigning a patient to a certain cluster. Cluster 1 included 5 patients with the most negative complex parameter changes (decrease compared to initial values).

Cluster 2 included 7 patients with positive deviations (the end values are higher). Cluster 3 included 11 patients with insignificant deviations in complex parameters. Table 2 shows the changes in composite parameters and the number of patients for each of the three clusters.

| Cases | ΔCP MS | ΔCA FS | ΔCA CVE | ΔUscore | P value | |

| The whole group | 23 | -2.2 | -2.3 | -0.3 | -2.5 | |

| Cluster 1 | 5 | -9.2 | -20.0 | -26.2 | -17.4 | 0.002560 |

| Cluster 2 | 7 | 6.3 | 13.9 | 10.3 | 9.7 | 0.000001 |

| Cluster 3 | 11 | -4.4 | -4.6 | 4.6 | -3.5 | 0.000015 |

Basic patient preoperative parameters analysis in different clusters showed that patients from the first cluster were somewhat older (63.7 years vs 58.5 years in cluster 2 and 54.1 years in cluster 3). Patients in cluster 1 also had a higher average number of implanted stents (1.7 vs 1.2 for two other clusters). The majority of patients in cluster 3 suffered from chronic CAD (7 out of 11) in clusters 1 and 2 (from acute myocardial infarction).

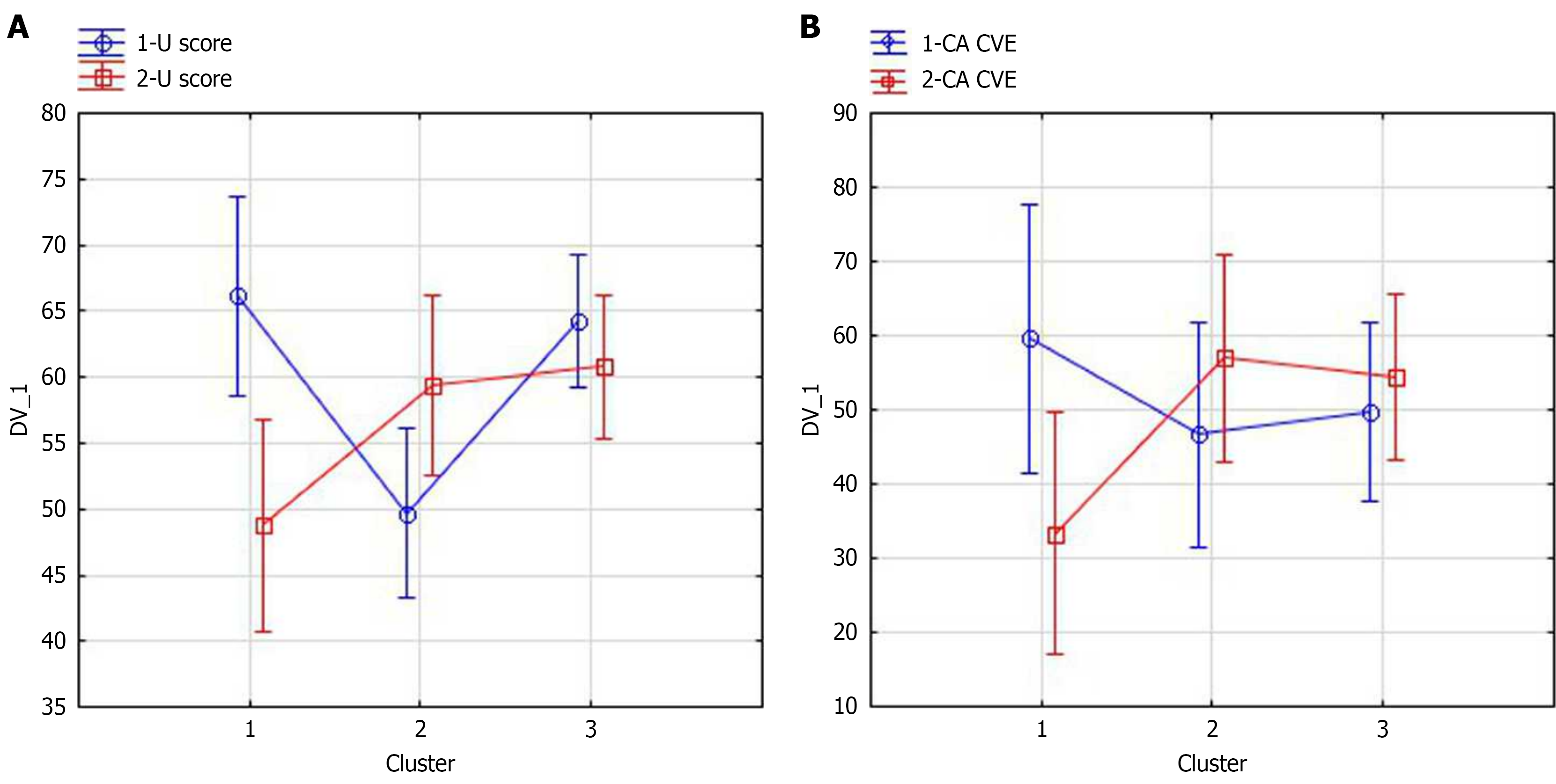

The changes of certain complex parameters in cluster used by repeated-measures ANOVA in clusters defined are shown in Figure 2. As we can see, in both cases, after the stenting, complex parameter values in cluster 2 increased (positive changes), while in cluster 1 these values decreased (negative changes). The impact of stenting on the change in the complex parameters in clusters was assessed (for Uscore: Partial ɳ2= 0.67, 95%CI: 0.45-0.88, P = 0.00001, for CA CVE partial ɳ2= 0.46, 95%CI: 0.20-0.60, P = 0.0018). Note that for cluster 1 the decrease in Uscore is statistically significant according the Bonferroni post hoc test P = 0.00004), as well as a decrease CA CVE (P = 0.02).

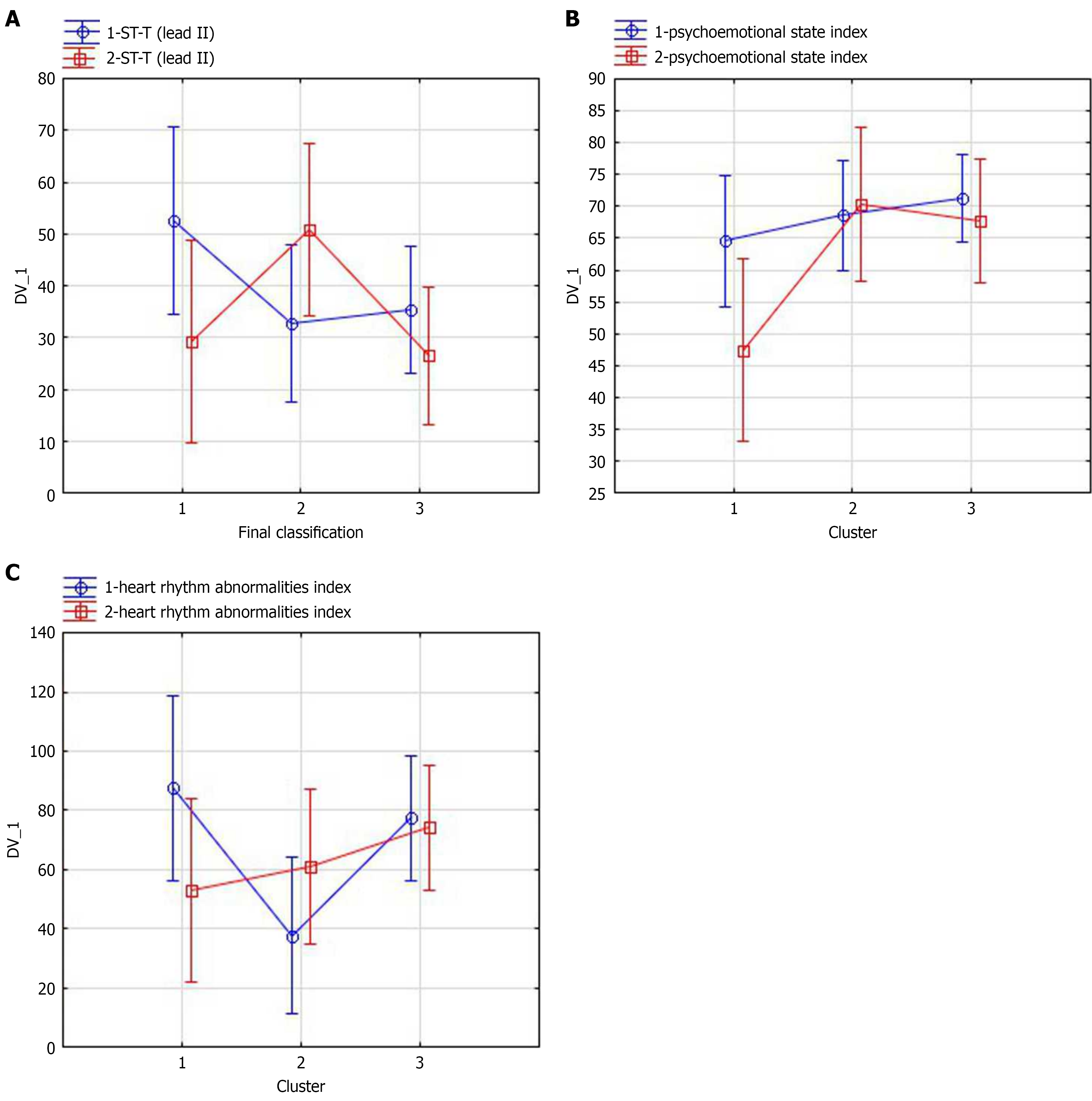

The next step was to identify specific ECG and HRV parameters that change the most after stenting and thus contribute to the complex parameter dynamics. For this purpose, the Feature selection procedure was used for features related to the corresponding complex parameters. The F-test was used for variable selection. Table 3 shows the primary signs of ECG, identified as the best predictors for complex indicators on the entire dataset. Figure 3 demonstrate the changes of several selected ECG and HRV parameters.

| Electrocardiogram and heart rate variability parameters | F-value | P-value |

| T wave amplitude in lead II | 30.817 | 0.000 |

| T wave amplitude in lead AvR | 21.883 | 0.000 |

| QRS-T angle in frontal plane | 8.622 | 0.0001 |

| Heart rhythm abnormalities index | 4.449 | 0.008 |

| HF-QRS | 3.429 | 0.021 |

| alpha T angle in frontal plane | 2.867 | 0.022 |

| Psychoemotional state index | 1.964 | 0.094 |

It should be noted that changes in primary indicators were less pronounced; for some indicators in the clusters, they changed in different directions. The average T wave amplitude (lead II) decreased after stenting (t-test for dependent samples ΔT wave amplitude = 35.5 µV, P = 0.039). The impact of stenting was estimated by ɳ2= 0.069, 95%CI: 0.01-0.08, P = 0.19. The average T wave amplitude (lead AvR) increased after stenting in all clusters, but most of all in the cluster 1 [Wilcoxon test ΔT wave amplitude (lead AvR) = -50.2 µV, P = 0.07].

After the stenting, the average QRS-T angle in the frontal plane in cluster 1 increased (ΔQRS-T angle = 34.8º) according to Wilcoxon test P = 0.043, indicating negative changes in myocardial, while in other clusters it decreased somewhat, namely in cluster 2 (ΔQRS-T angle = 24.4º, P = 0.027).

The integral characteristic of interval ST-T shape in lead II (mainly T wave amplitude) dynamics is shown in Figure 3A. The effect of stenting on various changes in the clusters was significant (ɳ2= 0.33, 95%CI: 0.18-0.41, P = 0.016), and the changes in ST-T shape in the clusters are multidirectional.

It is interesting to see the psychoemotional state trends based on HRV. Prior to stenting, psychoemotional state index in all subgroups was roughly the same; however, after stenting, it decreased in cluster 1 only (from 64.7 to 44.4 points; Figure 3B).

Prior to stenting, the subgroups differed significantly in heart rhythm abnormalities levels; namely, there were more significant heart rhythm abnormalities in cluster 2. After stenting, heart rhythm abnormalities in this group became less significant. At the same time, the opposite changes were observed in group 1. The detected heart rhythm abnormalities became more significant, demonstrating negative dynamics (Figure 3C). The impact of stenting on various changes in heart rhythm abnormalities in the clusters was significant (ɳ2= 0.34, 95%CI: 0.21-0.54, P = 0.015).

It is important to note that routine ECG interpretation systems, which are more general such as the Minnesota score and the University College London algorithm and more ischemic heart disease-specific such as the Selvester score, failed to detect significant changes in the studied subgroups after stenting.

Although electrocardiography has been in use for over a century (the first mass-produced devices appeared in 1905), it remains the most widely used, readily available, and low-cost objective tool for cardiac assessment. In recent years, its sphere of application has broadened well beyond traditional clinical settings.

This expansion has been propelled by advances over the last decade and a half, including modern digital approaches to ECG preprocessing/analysis, device miniaturization, and cloud-based ECG processing ecosystems. Most notably, increasingly sophisticated mathematical transforms and interpretive strategies now enable detection of subtle signal changes, improving sensitivity. Consequently, ECG serves not only to reveal structural heart disease in clinical practice, but also to support assessments in non-clinical environments.

As Stern memorably observed in 2006[21], ECG remains the cardiologist’s closest ally. Today, its utility extends to numerous medical and even non-medical fields. Our own work has shown that mathematically enhanced ECG analysis yields actionable information not only for clinical cardiology, but also for pediatrics, traumatology, rehabilitation, and in operational evaluations of military personnel, including in field conditions[22].

Our study also reflects another current trend in functional diagnostics. Recent advancements in cardiac imaging and diagnostics have underscored the need for integrated approaches that combine various physiological signals[23]. That study's findings underscored the incremental diagnostic value provided by the conjoint analysis of ECG and HRV parameters. Our methodology builds upon the premise that multimodal data synthesis can enhance the predictive accuracy for myocardial damage beyond what is achievable through single-parameter analysis.

The scientific novelty of our research lies in the development and application of a sophisticated ECG and HRV scaling method designed to detect subtle myocardial changes immediately following PCI with stent placement. This innovative approach transcends the capabilities of conventional ECG analysis by employing modern electrocardiographic indices that provide a more granular and insightful evaluation of myocardial electrical homogeneity.

Consistent with our earlier investigations, the joint use of ECG and HRV metrics provides the strongest diagnostic yield. In particular, HRV-based indices indicated a decline in the psychoemotional state within subgroup 1 (i.e., the cohort with intervention-related myocardial injury). Because single ECG or HRV features capture only fragments of the underlying physiology-and may even shift in opposite directions-drawing a robust conclusion about subtle myocardial damage requires an integrative summary metric. While the technical construction can vary, a rigorous workflow should include: (1) A priori justification of the composite indicator for the intended task; (2) Selection of data appropriate to the problem; (3) Multivariate analysis with appropriate normalization; (4) Identification of informative constituent variables with removal of redundant/collinear features; and (5) Aggregation of the retained indicators into a single composite score. We implemented this full sequence. At the same time, depending on the clinical context, specific partial indicators can be the most sensitive for detecting fine-grained changes.

Constructing a composite index represents a significant advancement over traditional single-parameter measures. Its ability to encapsulate multifaceted aspects of myocardial health offers a nuanced view that single metrics often fail to convey. This approach aligns with the growing consensus that cardiovascular health cannot be fully represented by discrete, isolated clinical findings but is better understood through the integrative analysis of multiple indicators. In practice, these are contemporary electrocardiographic indices that share a common pathophysiological substrate. Each, by different means, probes the electrical uniformity of the myocardium: The greater the electrical heterogeneity-i.e., dispersion in the amplitude and duration of transmembrane action potentials-the higher the probability of major cardiovascular events. In-depth ECG analysis based on AI is increasingly being used in clinical research. However, it's important to note that the ECG is also becoming a useful tool outside the hospital and even the doctor's office. In this regard, we would like to highlight our own experience: We successfully use advanced ECG and HRV analysis to determine the combat readiness of military personnel in the field. We also use ECG analysis, particularly proprietary composite indices, in rehabilitation, elite athlete training, and other fields. The identification of electrocardiographic indexes as key informants of myocardial electrical homogeneity presents intriguing clinical implications. These indexes, reflecting the underpinnings of myocardial pathology, could provide an early warning system for clinicians. This would allow for the prognostication of adverse events, potentially guiding more timely therapeutic interventions.

The angle between QRS complex and T wave peaks is in fact an improved Wilson ventricular gradient, known since 1934. Quite large-scale studies conducted recently have shown that this simple marker is a strong predictor of cardiovascular events and mortality in the general population.

Singular value decomposition of T wave represents the complexity of ventricular repolarization. Such an approach allows a comparison between the morphology of the T wave across the 12 leads and quantification of T-wave abnormalities in an observer-independent way[24].

This work is the first study dedicated to assessment of minor changes on ECG using the original scaling method immediately after coronary stenting. However, it has certain limitations. Firstly, the number of patients is small. Therefore, it is especially important to prove the statistical reliability of the findings. In our study, ECG recordings were repeated on the same sample of patients twice (before and after stenting). It is well known that the analysis of repeated measurements requires a smaller sample size and the use of repeated-measures ANOVA is effective. We performed repeated-measures ANOVA to estimate the effect size, using eta-squared and partial eta-squared based on the pre- and post-stenting outcomes for the identified subgroups. Effect sizes, as an estimate of the proportion of variance in the dependent variable explained by an independent variable, were expressed as partial eta-squared; the proportion of variance explained by the model equates to the sum of all the ɳ2. For example, the effect size for the stenting factor on the complex indicators in subgroups for Uscore was F = 5.39, P = 0.03, partial ɳ2 = 0.22, power = 0.59. The effect size for the interaction (stenting factor vs cluster) for Uscore was F = 20.4 partial ɳ2= 0.67, P = 0.00001, power = 0.99. For CA CVE, the effect size for the interaction (stenting factor vs cluster) was F = 8.7, partial ɳ2= 0.46, P = 0.0018, power = 0.94. Thus, a statistically significant difference was found between the effects of stenting on these parameters in the subgroups.

Second, we did not compare trajectories of minor ECG alterations with circulating biomarkers of myocardial injury or inflammation. Finally, we have not yet assessed the prognostic implications of the detected ECG changes-namely, relationships with mortality, repeat revascularization, or incident myocardial infarction over the first several years post-procedure. Consequently, the planned larger-scale studies will not only aim to corroborate the current findings but they will also seek to evaluate the longitudinal impact of the detected ECG changes on clinical outcomes. Additionally, exploring the interplay between these electrocardiographic changes and other clinical parameters, such as patient-reported symptoms and exercise capacity, will further refine the utility of the composite index in post-stenting patient management.

The current study introduces and validates an innovative ECG and HRV scaling method, demonstrating its utility in capturing and interpreting minor changes on the ECG immediately after PCI with stent insertion. The advanced ECG parameters, pivotal in this novel analytical approach, have emerged as more informative and precise than traditional ECG interpretation systems, which need to be revised for the subtle nuances required in post-PCI assessments.

Our research identified a specific patient subgroup, subgroup 1, which exhibited myocardial damage attributable to the stenting process. This subgroup not only showed differential ECG changes but was also distinguished by a higher average number of stents implanted, indicating a potentially more significant procedural impact on cardiac function. The delineation of this subgroup within the broader patient population signals the potential for individualized monitoring and management strategies in the post-operative care of patients undergoing PCI.

Further, the integration of HRV analysis provided additional depth to our findings, revealing a decrease in the psychoemotional state index within subgroup 1. This psychological dimension, in tandem with the physiological data gleaned from ECG analysis, paints a complete picture of the post-stenting condition, affirming the multifaceted nature of the cardiac response to stent placement.

Future research, particularly with larger patient cohorts and including biomarker trends, will be instrumental in reinforcing these findings and translating them into practice, with the ultimate aim of enhancing patient outcomes following coronary interventions.

The authors are sincerely grateful to Mrs. Anna Starynska (CardiolyseOy, Finland) for long-term support in relation to data management.

| 1. | Movsisyan NK, Vinciguerra M, Medina-Inojosa JR, Lopez-Jimenez F. Cardiovascular Diseases in Central and Eastern Europe: A Call for More Surveillance and Evidence-Based Health Promotion. Ann Glob Health. 2020;86:21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Benjamin EJ, Virani SS, Callaway CW, Chamberlain AM, Chang AR, Cheng S, Chiuve SE, Cushman M, Delling FN, Deo R, de Ferranti SD, Ferguson JF, Fornage M, Gillespie C, Isasi CR, Jiménez MC, Jordan LC, Judd SE, Lackland D, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth L, Liu S, Longenecker CT, Lutsey PL, Mackey JS, Matchar DB, Matsushita K, Mussolino ME, Nasir K, O'Flaherty M, Palaniappan LP, Pandey A, Pandey DK, Reeves MJ, Ritchey MD, Rodriguez CJ, Roth GA, Rosamond WD, Sampson UKA, Satou GM, Shah SH, Spartano NL, Tirschwell DL, Tsao CW, Voeks JH, Willey JZ, Wilkins JT, Wu JH, Alger HM, Wong SS, Muntner P; American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2018 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2018;137:e67-e492. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4163] [Cited by in RCA: 4944] [Article Influence: 618.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Simoons ML, Hugenholtz PG. Estimation of the probability of exercise-induced ischemia by quantitative ECG analysis. Circulation. 1977;56:552-559. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Sokolov MY, Danylchuk IV, Besh DI, Klantsa AI, Kolesnyk VO, Rafalyuk OI, Salo VM, Salo SV, Sorokhtey LV, Furkalo SM. Реєстр перкутанних коронарних втручань: зміни за останні роки (2010–2022). Ukr J Cardiol. 2024;31:7-33. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 5. | Kim MS, Dean LS. In-stent restenosis. Cardiovasc Ther. 2011;29:190-198. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Warren SG, Wagner GS, Bethea CF, Roe CR, Oldham HN, Kong Y. Diagnostic and prognostic significance of electrocardiographic and CPK isoenzyme changes following coronary bypass surgery: correlation with findings at one year. Am Heart J. 1977;93:189-196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Babu GG, Walker JM, Yellon DM, Hausenloy DJ. Peri-procedural myocardial injury during percutaneous coronary intervention: an important target for cardioprotection. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:23-31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 138] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Califf RM, Abdelmeguid AE, Kuntz RE, Popma JJ, Davidson CJ, Cohen EA, Kleiman NS, Mahaffey KW, Topol EJ, Pepine CJ, Lipicky RJ, Granger CB, Harrington RA, Tardiff BE, Crenshaw BS, Bauman RP, Zuckerman BD, Chaitman BR, Bittl JA, Ohman EM. Myonecrosis after revascularization procedures. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;31:241-251. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 359] [Cited by in RCA: 363] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Callard F, Perego E. How and why patients made Long Covid. Soc Sci Med. 2021;268:113426. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 484] [Cited by in RCA: 525] [Article Influence: 105.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Chaikovsky IA, Primin MA, Kazmirchuk AP. Development and implementation in medical practice of new information technologies and metrics for the analysis of subtle changes in the electromagnetic field of the human heart. Vìsn Nac Akad Nauk Ukr. 2021;2:33-43. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 11. | Chaikovsky I. Electrocardiogram scoring beyond the routine analysis: subtle changes matters. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2020;17:379-382. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Method of ECG evaluating based on universal scoring system. [cited 3 November 2025]. Available from: https://www.freepatentsonline.com/y2018/0199845.html. |

| 13. | Colan SD. The why and how of Z scores. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2013;26:38-40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Wong D, Bonnici T, Knight J, Gerry S, Turton J, Watkinson P. A ward-based time study of paper and electronic documentation for recording vital sign observations. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2017;24:717-721. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Chaikovsky I, Kryvova O, Kazmirchyk A, Mjasnikov G, Sofienko S, Bugay A, Stadniuk L, Tverezovskyi M. Assessment of the Post-Traumatic Damage of Myocardium in Patients with Combat Trauma Using a Data Mining Analysis of an Electrocardiogram. 2019 Signal Processing Symposium (SPSympo), Krakow, Poland, 2019: 34-38. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 16. | Apykhtin K, Chaikovsky I, Yaroslavska S, Starynska A, Stadnyk L. GW29-e0521 Adaptation of cardiovascular system to work in the night shifts of doctors and nurses. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72:C243. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Patrick Neary J, Baker TP, Jamnik V, Gledhill N, Chaikovsky I, Frolov YA, Wasiliew VE. Multimodal Approach to Cardiac Screening of Elite Ice Hockey Players During the NHL Scouting Combine. Med Sci Sport Exer. 2014;46:742. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kaverinskiy V, Chaikovsky I, Mnevets A, Ryzhenko T, Bocharov M, Malakhov K. Scalable Clustering of Complex ECG Health Data: Big Data Clustering Analysis with UMAP and HDBSCAN. Computation. 2025;13:144. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 19. | Clarke R, Chaikovsky I, Wright N, Du H, Chen Y, Guo Y, Bian Z, Li L, Chen Z. Independent relevance of left ventricular hypertrophy for risk of ischaemic heart disease in 25,000 Chinese adults. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:ehaa946.2938. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Bradley RT, McCraty R, Atkinson M, Tomasino D, Daugherty A, Arguelles L. Emotion self-regulation, psychophysiological coherence, and test anxiety: results from an experiment using electrophysiological measures. Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback. 2010;35:261-283. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Stern S. Electrocardiogram: still the cardiologist's best friend. Circulation. 2006;113:e753-e756. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Chaikovsky I, Primin M, Nedayvoda I, Kazmirchuk A, Frolov Y, Boreyko M. New metrics to assess the subtle changes of the heart's electromagnetic field. In: Pal K, Ari S, Bit A, Bhattacharyya S, editors. Advanced Methods in Biomedical Signal Processing and Analysis. Academic Press, 2023: 257-310. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 23. | Counseller Q, Aboelkassem Y. Recent technologies in cardiac imaging. Front Med Technol. 2022;4:984492. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Priori SG, Mortara DW, Napolitano C, Diehl L, Paganini V, Cantù F, Cantù G, Schwartz PJ. Evaluation of the spatial aspects of T-wave complexity in the long-QT syndrome. Circulation. 1997;96:3006-3012. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/