Published online Dec 26, 2025. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v17.i12.112389

Revised: September 7, 2025

Accepted: November 7, 2025

Published online: December 26, 2025

Processing time: 147 Days and 8.5 Hours

Cardiac sarcoidosis (CS) is an infiltrative disease with manifestations such as non-sustained ventricular tachycardia (NSVT) and heart failure (HF). Antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) and antiphospholipid positivity (APP) are prothr

A 54 year old male with HF presented with several cardiopulmonary symptoms. Chest imaging showed bilateral patchy and reticulonodular infiltrates. Subse

Fibrotic CS with active SS and APS/APP has not been previously described in literature. This case utilized a modified approach for the management of this combination of diseases. As immunosuppressants such as steroids have limited utility in fibrotic sarcoidosis and a potential for thromboembolic complications in the presence of APP, an accelerated transition to non-thrombotic immunosuppressants can be advantageous in the long term treatment of this combination of diseases.

Core Tip: Fibrotic cardiac sarcoidosis with concomitant active systemic sarcoidosis and antiphospholipid positivity are unreported in literature. The various systemic manifestations of this combination of diseases require intricate medical management. As traditional immunosuppressants have limited utility in burnt sarcoidosis and concurrent antiphospholipid positivity raises risks for thromboembolic disease, essential management strategies include close monitoring of antiphospholipid disease and timely tapering from thrombotic to non-thrombotic immunosuppressants.

- Citation: Khasnavis S, Sakul S, Novakovic M, Adinugraha P, Mehta D. Cardiac sarcoidosis with a twist - active and fibrotic sarcoid with antiphospholipid positivity: A case report. World J Cardiol 2025; 17(12): 112389

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8462/full/v17/i12/112389.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4330/wjc.v17.i12.112389

Sarcoidosis is an autoimmune phenomenon characterized by granulomatous inflammation of the lungs, skin, heart, liver, parotid glands, gastrointestinal tract, and other organ systems[1]. The etiology of this autoimmune development is idiopathic and of debate to this day, considered in part to be from hypersensitivity to unknown foreign antigens[1,2]. The diagnosis of sarcoidosis is frequently obtained from a combination of clinical presentation, laboratory tests, and imaging modalities[1,2]. The general treatment for sarcoidosis involves systemic steroid therapy, although the optimal duration of immunosuppressive therapy continues to be a subject of investigation[1,2].

Sarcoid involvement in the heart is seen in anywhere from 5% to 25% of sarcoidosis cases[1,2]. Cardiac involvement, known as cardiac sarcoidosis (CS), can manifest with potentially devastating complications such as conduction ab

The concurrence of sarcoidosis with other autoimmune diseases has been noted most frequently in cases involving multiple myeloma and Sjogren’s syndrome[5-7]. However, sarcoidosis is rarely seen in combination with antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) or antiphospholipid positivity (APP). APS and APP are characterized by positive laboratory testing for lupus anticoagulant, anticardiolipin (ACL), or beta-2-microglobulin (B2M) antibodies. Their diagnoses require that one or more of the three antibodies must be positive on two or more laboratory tests 3 months apart[6]. APS is distinguished from APP by the presence of thromboembolic phenomena such as deep vein thromboses, pulmonary emboli, cerebrovascular accidents, and myocardia infarctions[6,7]. It has been theorized that the concurrence of APS and APP with sarcoidosis is a result of immune dysregulation and autoimmunity[8]. Moreover, these prothrombotic phenomena have been described in cases of pulmonary sarcoidosis but not CS[8-14]. We present here a case of burnt CS with active SS and APP and go on to describe the management steps for this complex case presentation.

Shortness of breath and palpitations.

The patient was a 54-year-old male who presented to the emergency department complaining of intermittent dyspnea and palpitations. These symptoms had been present for a total of 3 weeks. They were associated with left chest pressure and dizziness/Lightheadedness. The symptoms were non progressive and not related to any other symptoms. He denied headache, syncope, blurred vision, hearing loss, chest pain, cough, sputum, fever, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, constipation, weakness, numbness, or urinary issues. Symptoms were not related to activity, rest, or any particular environmental setting.

The patient had past history of heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) 20%, interstitial lung disease of unknown etiology, chronic kidney disease 3b, pulmonary hypertension, and chronic marijuana use daily for 10 years.

The patient's home medications were metoprolol tartrate, sacubitril valsartan, empagliflozin, and pantoprazole. He denied allergies and smoking cigarettes. He consumed alcohol 1-2 times a month. He denied supplements, recent travels, sick contacts, partners, and sexually transmitted infections. His home environment was notable for ongoing construction and exposure to smoke, dust, and mold over a 3-year period. He worked as a chef and denied toxic exposures there. Family history was noncontributory.

Vitals were blood pressure 95/60 mmHg, heart rate 63 beats per minute, temperature 36.5 °C, respirations 20 breaths per minute, and SpO2 100% on room air. The physical examination was notable for a regularly irregular heart rate and periods of regular tachycardia.

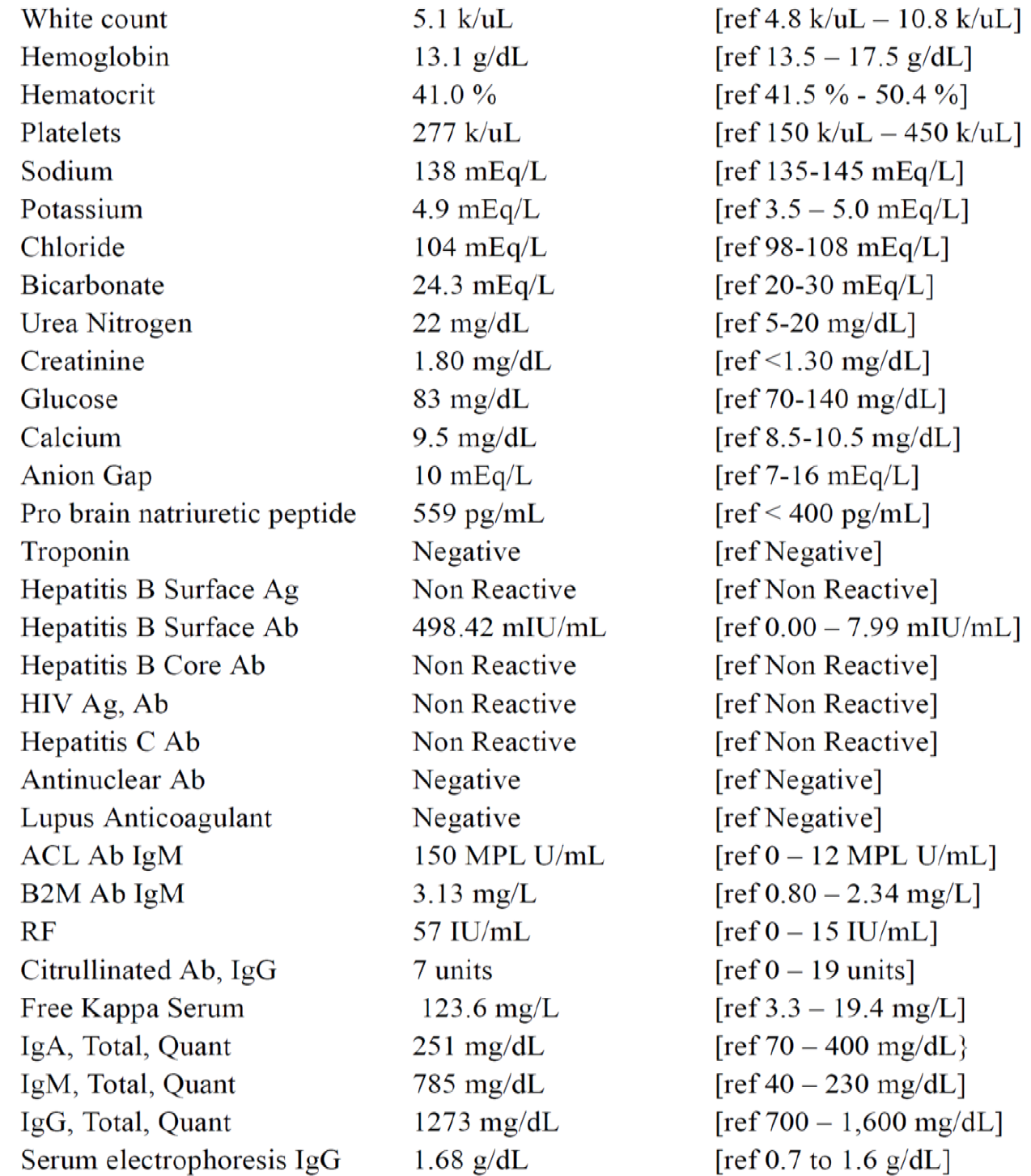

Complete blood cell count, complete metabolic profile (CMP), cardiac testing, infectious testing, and rheumatologic testing were ordered (Figure 1). CMP was notable for elevated creatinine, urea nitrogen, and pro brain natriuretic peptide. Rheumatologic testing was notable for ACL, B2M, and rheumatoid factor. Tests for tuberculosis, human immunodeficiency virus, and other infectious etiologies were negative.

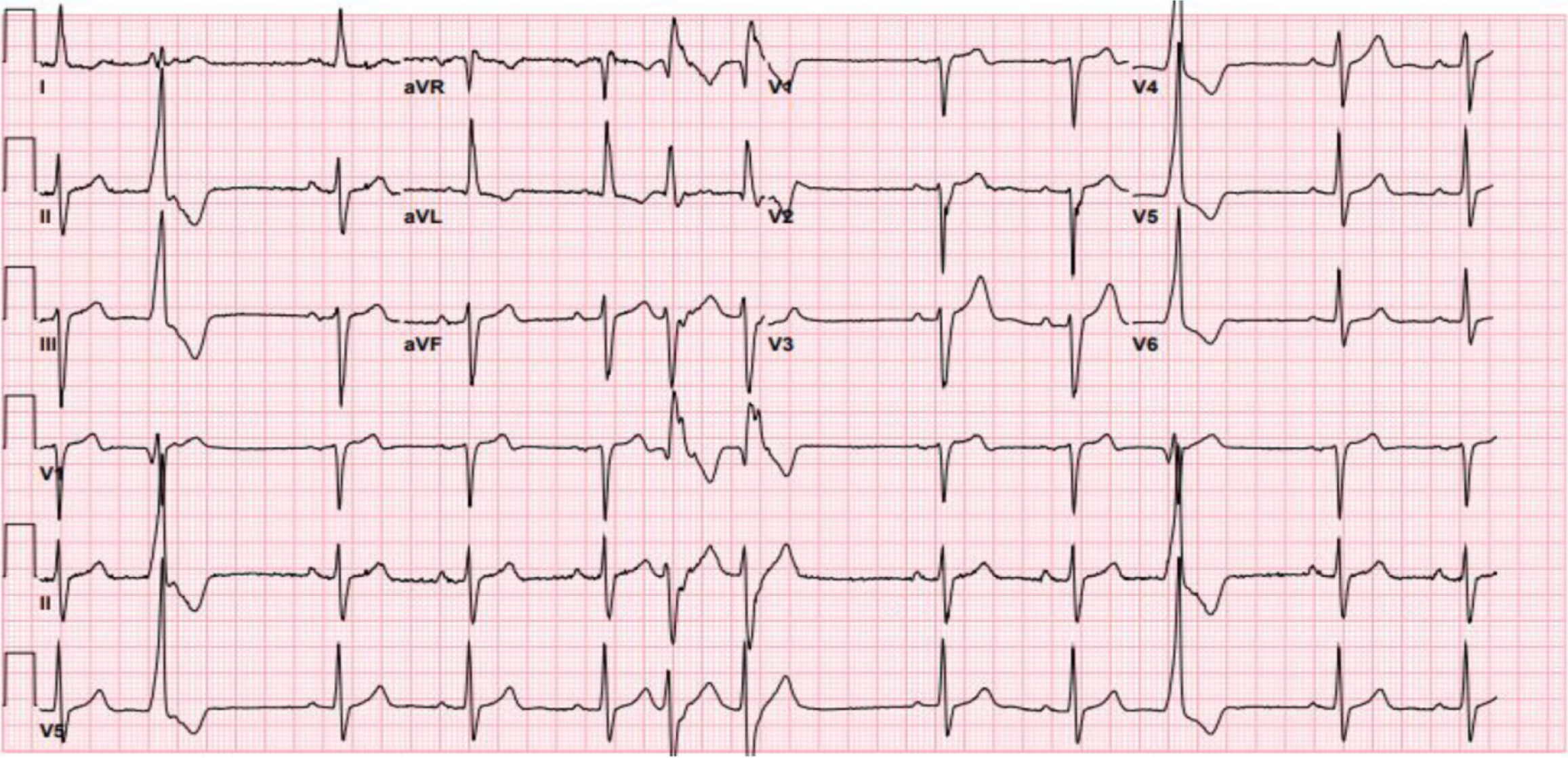

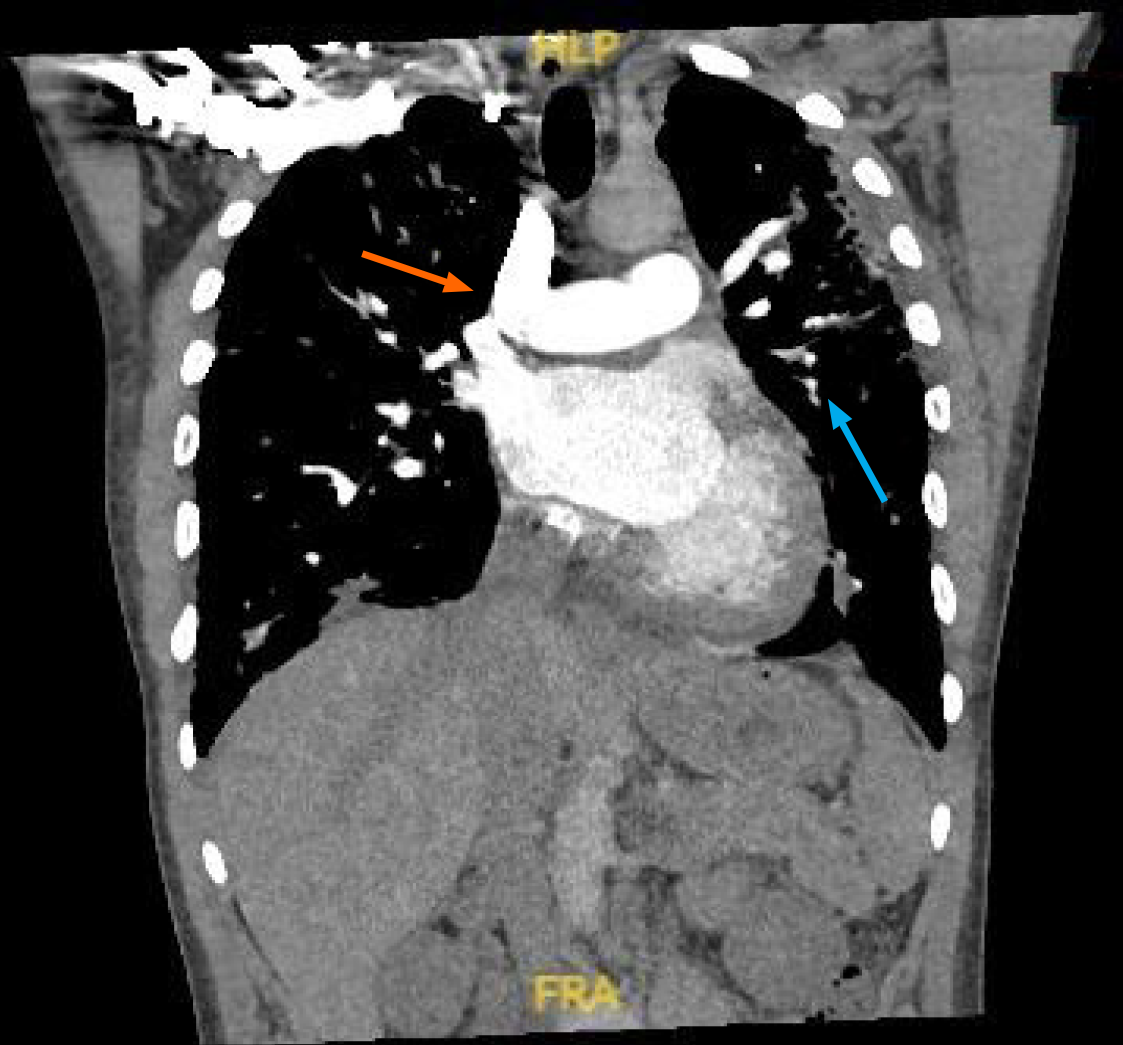

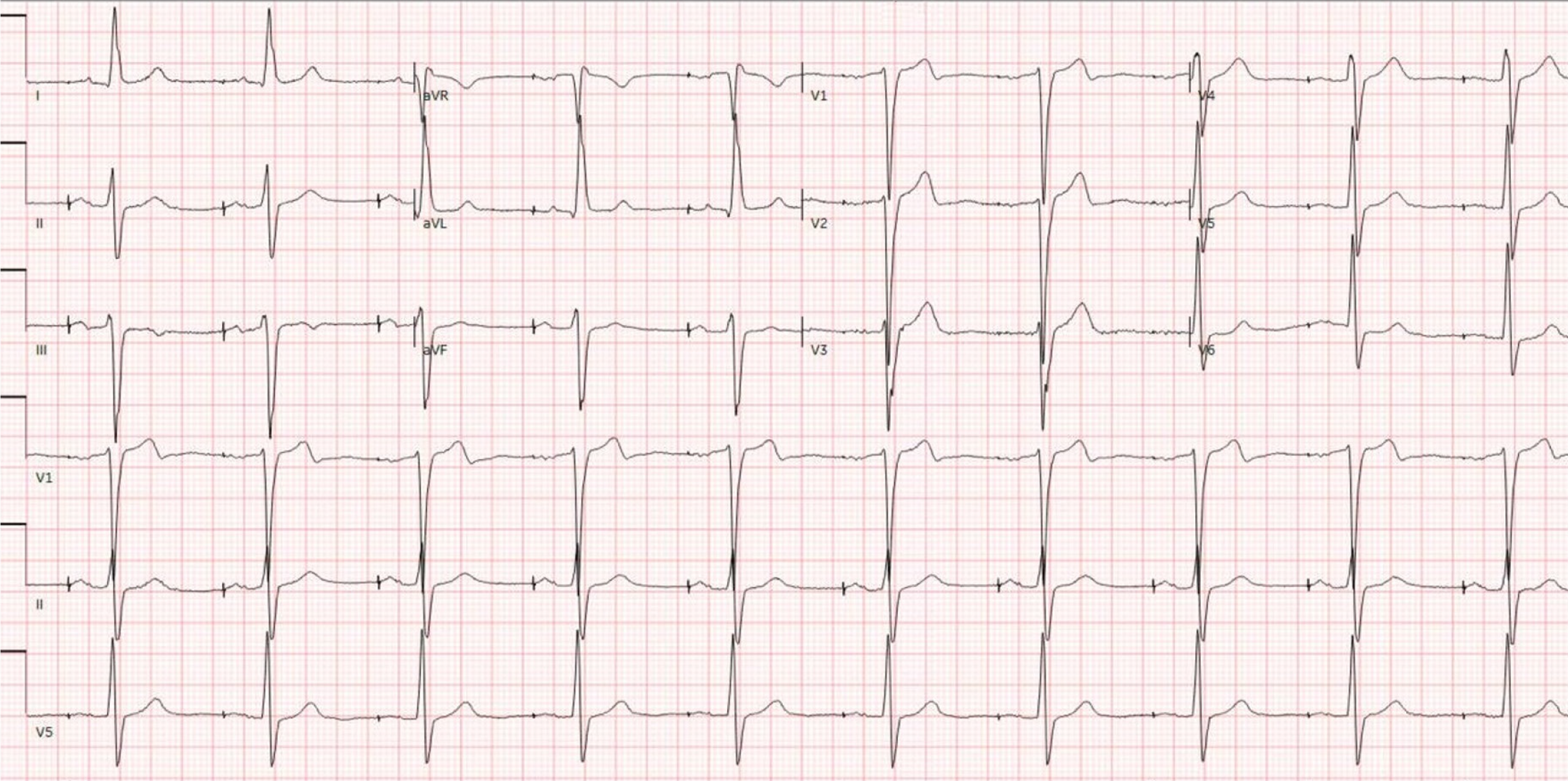

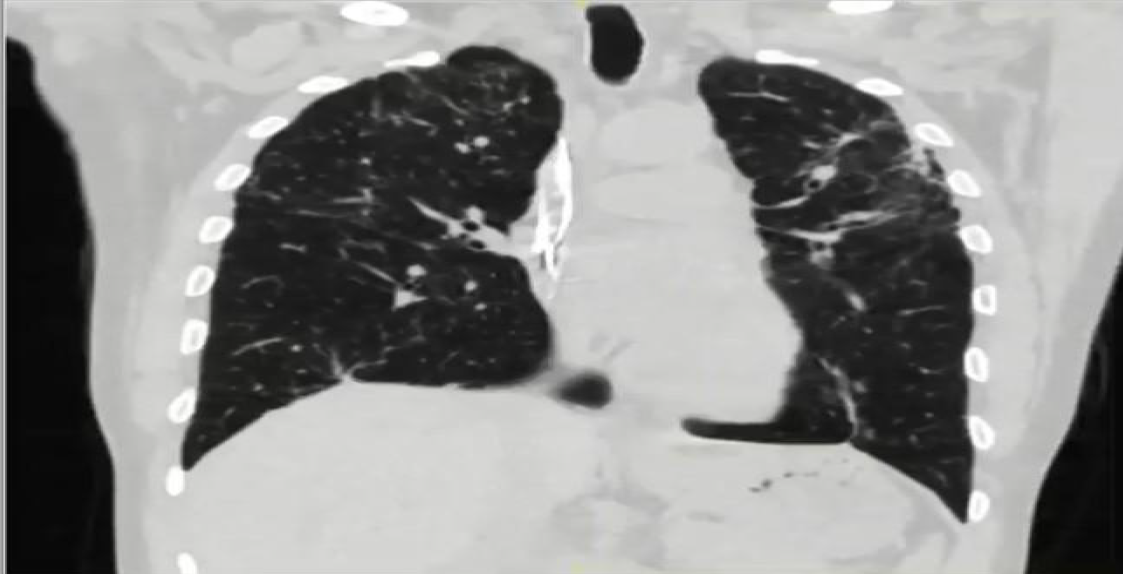

Telemetry showed a high premature ventricular complex (PVC) burden coupled with episodes of non-sustained ventricular tachycardia (NSVT). Electrocardiogram (ECG) showed frequent PVCs (Figure 2). Chest X-ray showed coarse reticulonodular infiltrates with diffuse lung nodules and bronchial wall thickening. Computed tomography angiogram (CTA) of the chest (Figure 3) demonstrated diffuse pulmonary nodules in all lung lobes and dilated main pulmonary trunk consistent with pulmonary hypertension.

Transthoracic echocardiogram showed dilated left ventricle (LV) with normal thickness; echo also showed systolic dysfunction with ejection fraction 20% and diffuse hypokinesis.

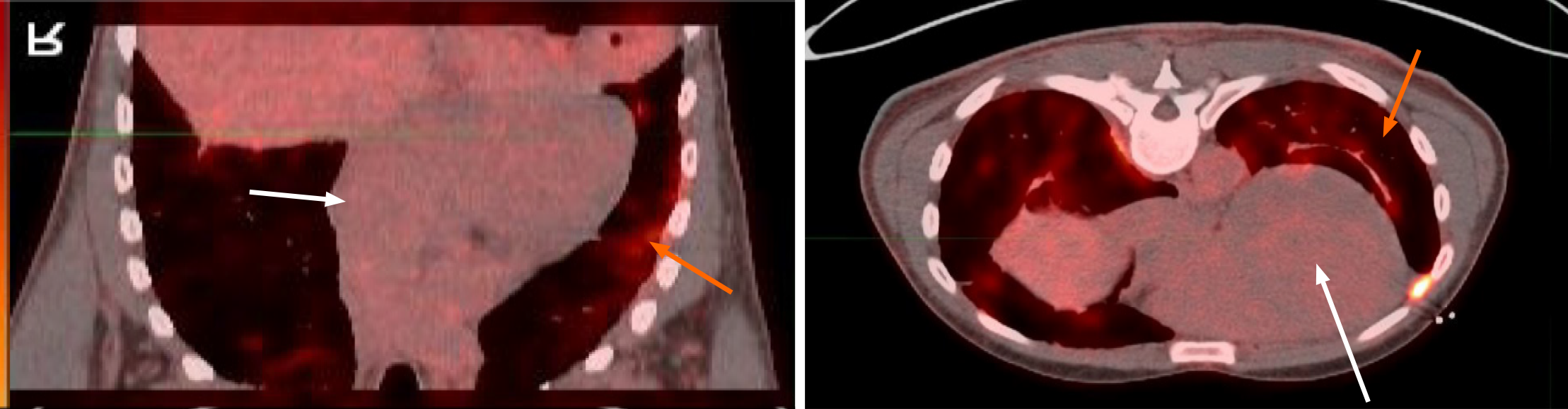

Endoscopic bronchial ultrasound with bronchoalveolar lavage showed increased CD4: CD8 ratio without malignant cells. cMRI was performed and showed LV dilation with severe systolic dysfunction, global hypokinesis, and LGE (Figure 4). Whole body PET revealed patchy perfusion abnormalities in the basal to mid inferior wall and mid septal segments (Figure 5). It also revealed FDG uptake in the lungs without FDG uptake in the heart. Left heart catheterization showed normal coronary arteries, right sided pressures, pulmonary vascular resistance index, pulmonary capillary wedge, left ventricular end diastolic pressure, cardiac output, and valvular function.

Multidisciplinary expert consultation and care was carried out for this case. Consultations were made to general cardiology, critical care cardiology, electrophysiology, heart failure, rheumatology, hematology, and pulmonology services. After inputs from these various specialists, the patient was initiated on the medical therapies described above and also underwent imaging as described above. After discharge, the patient continued to follow up with these specialists for further management.

The patient was diagnosed with burnt CS and active SS. He was also diagnosed with irreversible NSVT and APP syndrome. Differentials included interstitial lung fibrosis, sarcoidosis, amyloidosis, lung malignancy, myositis, premature atrial/ventricular contractions, ventricular tachycardia, supraventricular tachycardia, decompensated heart failure, myocarditis, ischemic heart disease, acute coronary syndrome, orthostatic hypotension, and community/hospital acquired pneumonia.

High dose prednisone of 40 mg daily was begun with a plan for slow taper and switch to methotrexate (MTX). Given initial positive testing for ACL and B2M antibodies, the patient was instructed to follow up in 3 months time for repeat testing. He was discharged on GDMTs along with prednisone 40 mg daily. One week later in cardiology clinic, he was started on mexiletine for NSVTs and on low dose MTX for SS. MTX was increased biweekly from 7.5 mg weekly to 15 mg weekly. Prednisone was tapered down to 10 mg daily within the first 5 months. After these first 5 months, ACL IgM and B2M IgM levels were still positive at 147 U/mL and > 150 GPI units respectively. No thromboembolic events were observed. Given confirmation of APP, aspirin 81 mg daily was begun. Prednisone was then tapered down to 5 mg daily for 5 months followed by 2.5 mg daily for 2 weeks and then stopped.

At one year follow up in cardiology clinic, the patient reported feeling well. He had not had any concerning palpitations, shortness of breath, leg swelling, or chest discomfort requiring hospitalization. He had also quit smoking marijuana. His clinical status continually improved and he remained free of major heart failure, arrhythmia, and thromboembolic events over 1.5 years of follow up. A repeat ECG at 1.5 years after admission showed resolution of PVCs and NSVTs with maintenance of atrial paced rhythm (Figure 6). A repeat echocardiogram at 1.5 years after admission showed persistently low but slight improved left ventricular ejection fraction of 39%. Systolic dysfunction and hypokinesis from prior echo were unchanged. A repeat chest CTA at 1 year after admission showed improvement of pulmonary sarcoid nodules (Figure 7). There was no evidence of disease progression or superimposed acute infection/exacerbation.

The profound complications of CS have been detailed very thoroughly in current literature including but not limited to conduction block, recurrent PVCs, NSVT, HFrEF, and valvular disease[1,2]. In CS, therapeutic management is more involved due to the numerous complications associated with inflammation of the heart. Prior evidence has been conflicted as to whether corticosteroids play a role in improving cardiac function[3]. While certain studies have suggested that the benefit is limited to HFrEF with ejection fraction greater than 35%, others have suggested the opposite effect of benefit in HFrEF with ejection fraction less than 35%[3]. As such CS management usually calls upon various immunosuppressants, rate/rhythm control agents, GDMTs, and in severe cases implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICDs)/cardiac resynchronization therapy[3,4]. Among immunosuppressants, the utility of corticosteroids in active CS has been a subject of much debate. Newer studies recommend steroids as first line therapy for atrioventricular block starting at 30-40 mg and tapering according to response; these studies concur with prior findings showing that steroids have limited utility in severe HFrEF[3,4]. Moreover, it is known that steroid therapy can increase risk for thromboembolism, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and hyperglycemia, with the probability of thrombi increasing exponentially per year of dosing higher than 17.5 mg[3,4]. In regards to further control of inflammation, methotrexate, azathioprine, and biologics are considered excellent transition medications during the taper of steroids and are prescribed in accordance to patient comorbidities[3,4].

Aside from immunosuppressants, the management of CS HFrEF follows the recommendations for routine HFrEF management. As such, GDMTs are prescribed according to patients' comorbidities[3,4]. The decision to implant ICDs and resynchronization therapy follows established guidelines pertaining to ejection fraction, New York symptom classification, QRS duration, and arrhythmias[3,4].

While the utility of immunosuppressants in active SS and CS is well established, their utility in fibrotic CS is not[3,4]. Moreover, a strategic approach to the management of burnt CS has only been described in a select few studies[3,4]. Notably, these cases did not present with concomitant APS or APP. Overall, the utility of immunosuppressants in fibrotic CS continues to be a subject for future investigation; therapeutics at this time are limited to antiarrhythmics, GDMTs, cardiac devices, and transplantation[3-5]. Moreover, the management of pulmonary SS with APS has been described in select few cases and involves combination of immunosuppressive therapy with anticoagulation[6-9]. Certain factors are known to elevate the risk of thromboembolism in SS. Among these factors are APS and APP both of which are linked to vascular events in pulmonary SS[8]. Notably, immunosuppressant and anticoagulation combination has been successful in reducing pulmonary symptoms and minimizing the likelihood of a thrombotic event[8-11]. The optimal duration of steroid therapy in these cases varies according to patient response and comorbidities but generally has been up to 12 months and beyond[12-15]. Given the infrequency at which fibrotic CS is reported and encountered, cases and guidelines for the overall management of it continue to be very limited. Moreover, the impact of immunosuppressants on active pulmonary and cardiac sarcoidosis is known but their impact on pulmonary hypertension is unknown; at best it has been shown that steroids do not significantly alter the hemodynamics of pulmonary flow even after treatment of left heart and lung sarcoid[16-20].

The incidence of fibrotic CS with systemic SS and APP has not been previously reported in literature. This is the first case to describe the complexity in managing a rare combination of diseases. Consistent with prior guidelines, ICD, GDMTs, and rhythm control were utilized in the patient. Given the presence of active SS, the decision was made to start on high dose prednisone and gradually transition to MTX. However, the presence of APP and potential side effects of steroid therapy raised concerns for long term vascular complications. The decision was made to begin lowering the steroid dose early and to transition to full dose methotrexate within 3 months of starting steroids. Using this approach, the prednisone was tapered at a faster rate and the total length of therapy was approximately 10 months. Although an early taper of steroids can present the risk of incomplete therapy and recurrence, the overall benefits of this taper outweighed the risks. Likewise, the overall benefits and risks of biologic therapy were taken into consideration; MTX was a preferable option for long term treatment as the patient was not at risk of infections or hepatic disease. The overlap of prednisone and MTX tapers assured that immunosuppression would remain adequate before, during, and after the transition phase. Moreover, aspirin therapy was begun to prevent vascular complications of APP; routine monitoring was done for vascular events that would suggest progression to APS and necessitate anticoagulation. This strategy was successful as evidenced by the patient's symptomatic improvement along with the regression of pulmonary disease and the absence of thromboembolic events at follow up. These findings are consistent with findings from other studies which also demonstrated the minimization of vascular complications such as stroke, deep vein thrombi, retinal artery occlusion, and pulmonary emboli after appropriate measures were taken to protect against clots. Notably, the titers of antiphospholipid antibodies in our case decreased as biologic therapy was ramped up, demonstrating a positive correlation with sarcoid activity. This serves as further evidence that sarcoidosis is linked to other autoimmune conditions such as APP/APS through an unspecified autoimmune process. Although there was no evidence of worsening heart failure, coronary disease, valvular disease, or arrhythmias due to immunosuppressants, the cardiac benefit of immunosuppressants was unknown and at best there may have been minimal enhancement in cardiac function. Altogether, the improvement in cardiac function was more likely the synergistic impact of GDMTs, ICD, rhythm control, and lifestyle adjustments (Table 1).

| Timeline | Events |

| Day 1 | A 54-year-old male with non-ischemic heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, interstitial lung disease, pulmonary hypertension, and chronic marijuana presents with recurrent palpitations and dyspnea. Telemetry shows a high burden of PVCs and NSVT. Chest X-ray and computed tomography demonstrate lung nodules with fibrosis |

| Day 4 | Bronchial ultrasound and alveolar lavage confirm pulmonary sarcoidosis. Escalation of rate control therapy fails to resolve PVCs and NSVTs |

| Day 6 | Initiation of rhythm control therapy decreases and eventually resolves arrhythmias. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging showed left ventricular dilation with severe systolic dysfunction, global hypokinesis, and patchy uptake |

| Day 9 | Positron emission tomography has system FDG but no cardiac FDG, confirming active systemic sarcoidosis (SS) and burnt CS. ACL and B2M antibodies are positive, raising concern for APP and antiphospholipid syndrome. Medical and device therapy are begun for burnt CS and prednisone for SS |

| Day 16 | MTX is begun with plan for taper up and prednisone for taper down |

| Day 166 | Repeat ACL and B2M antibodies are positive in the absence of thromboembolic events. APP is confirmed; aspirin therapy is begun and prednisone taper is accelerated |

| Day 280 | Transition to MTX is complete and prednisone discontinued |

| Day 360 | Follow up imaging demonstrates resolution of arrhythmias and pulmonary disease; no thromboembolic phenomena are observed |

Overall our case demonstrates a multilayered approach to the management of CS and APP; a combination of medical and device therapies were required for achieving a good outcome, particularly given the irreversibility of fibrotic CS. However, much remains to be understood about the active and fibrotic stages of CS particularly in combination with APP/APS. Given the unclear overall benefits of immunosuppressive therapy in CS as well as the risks for vascular events with APP/APS, future investigations will be crucial to establish the optimal management strategies for this combination of diseases.

Fibrotic CS with active systemic SS and APP is an unreported phenomenon. This combination of diseases requires close monitoring for arrhythmias, heart failure, valve disease, and thromboembolism. Given the limited utility of immunosuppressants in fibrotic sarcoidosis and potential for vascular events with concurrent APP, a faster transition to non-thrombogenic biologics for active SS and close monitoring for progression to APS are desirable management strategies.

| 1. | Aftab A, Szeto S, Aftab Z, Bokhari S. Cardiac sarcoidosis: diagnosis and management. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2024;11:1394075. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Sallam S, Shahrori Z, Rana M, Sullivan C. A Case of Burnt-Out Cardiac Sarcoidosis Presenting With Sustained Ventricular Tachycardia. Cureus. 2022;14:e28931. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Birnie DH, Nery PB, Ha AC, Beanlands RS. Cardiac Sarcoidosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68:411-421. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 275] [Cited by in RCA: 429] [Article Influence: 47.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Cheng RK, Kittleson MM, Beavers CJ, Birnie DH, Blankstein R, Bravo PE, Gilotra NA, Judson MA, Patton KK, Rose-Bovino L; American Heart Association Heart Failure and Transplantation Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology, and Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing. Diagnosis and Management of Cardiac Sarcoidosis: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2024;149:e1197-e1216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 147] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 60.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Hussain K, Shetty M. Cardiac Sarcoidosis. 2024 Mar 1. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Ina Y, Takada K, Yamamoto M, Sato T, Ito S, Sato S. Antiphospholipid antibodies. A prognostic factor in sarcoidosis? Chest. 1994;105:1179-1183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Singh R, Conway MD, Wilson WA. Antiphospholipid syndrome in a patient with sarcoidosis: a case report. Lupus. 2002;11:756-758. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Pathak R, Khanal R, Aryal MR, Giri S, Karmacharya P, Pathak B, Acharya U, Bhatt VR. Sarcoidosis and Antiphospholipid Syndrome: A Systematic Review of Cases. N Am J Med Sci. 2015;7:379-383. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Carragoso A, Silva JR, Capelo J, Faria B, Gaspar O. A patient with sarcoidosis and antiphospholipid syndrome. Eur J Intern Med. 2008;19:e80-e81. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 10. | Esen BA, Kıyan E, Küçükkaya RD, Tabak L, Aktürk F, Arseven O, Okumuş G, İnanç M. Antiphospholipid Syndrome Presenting As Massive Pulmonary Embolism in a Patient With Sarcoidosis. Electron J Gen Med. 2005;2:173-176. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Takahashi F, Toba M, Takahashi K, Tominaga S, Sato K, Morio Y, Nakao Y, Tajima K, Miura K, Uekusa T, Fukuchi Y. Pulmonary sarcoidosis and antiphospholipid syndrome. Respirology. 2006;11:506-508. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kolluri N, Elwazir MY, Rosenbaum AN, Maklady FA, AbouEzzeddine OF, Kapa S, Blauwet LA, Chareonthaitawee P, McBane RD 2nd, Bois JP. Effect of Corticosteroid Therapy in Patients With Cardiac Sarcoidosis on Frequency of Venous Thromboembolism. Am J Cardiol. 2021;149:112-118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Yatsynovich Y, Dittoe N, Petrov M, Maroz N. Cardiac Sarcoidosis: A Review of Contemporary Challenges in Diagnosis and Treatment. Am J Med Sci. 2018;355:113-125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Korthals D, Bietenbeck M, Könemann H, Doldi F, Ventura D, Schäfers M, Mohr M, Wolfes J, Wegner F, Yilmaz A, Eckardt L. Cardiac Sarcoidosis-Diagnostic and Therapeutic Challenges. J Clin Med. 2024;13:1694. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Vereckei A, Besenyi Z, Nagy V, Radics B, Vágó H, Jenei Z, Katona G, Sepp R. Cardiac Sarcoidosis: A Comprehensive Clinical Review. Rev Cardiovasc Med. 2024;25:37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Trivieri MG, Spagnolo P, Birnie D, Liu P, Drake W, Kovacic JC, Baughman R, Fayad ZA, Judson MA. Challenges in Cardiac and Pulmonary Sarcoidosis: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76:1878-1901. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 143] [Cited by in RCA: 154] [Article Influence: 25.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Liu A, Price LC, Sharma R, Wells AU, Kouranos V. Sarcoidosis Associated Pulmonary Hypertension. Biomedicines. 2024;12:177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Ruiz-Irastorza G, Crowther M, Branch W, Khamashta MA. Antiphospholipid syndrome. Lancet. 2010;376:1498-1509. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 625] [Cited by in RCA: 563] [Article Influence: 35.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Sharma OP. Sarcoidosis and other autoimmune disorders. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2002;8:452-456. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Qiao H, Tian H, Jiang M, Li J, Lan T, Lu M. Multimodality imaging in cardiac sarcoidosis: A case series of diverse phenotypes. J Clin Imaging Sci. 2025;15:5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/