Published online Dec 26, 2025. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v17.i12.112126

Revised: September 17, 2025

Accepted: October 30, 2025

Published online: December 26, 2025

Processing time: 159 Days and 13.6 Hours

Left ventricular noncompaction (LVNC) is a genetic cardiomyopathy. It is characterized by intensely developed trabeculae in the ventricles with deep intertrabecular lacunae. LVNC manifests as arrhythmias and heart failure with a predisposition for thrombus formation.

To study predictors of arrhythmic, thromboembolic events and adverse outcomes (death/transplantation) in adult patients with LVNC.

Adult patients with LVNC were included (n = 125; mean follow-up: 14 months). Electrocardiography, echocardiography, and 24-hour electrocardiography monitoring were performed. Other procedures were conducted for some patients including: Coronary angiography; cardiac magnetic resonance imaging; cardiac computed tomography; genetic testing; myocardial pathological examination; and anti-cardiac antibody level estimation. Primary endpoints were death, heart transplantation, combined endpoint (death + transplantation), and sudden cardiac death. Secondary endpoints were intracardiac thrombosis, embolic events, myo

LVNC manifestations included non-sustained VT, thrombosis/embolism, sustained VT, and sudden cardiac death. Non-sustained VT was associated with the New York Heart Association (NYHA) chronic heart failure (CHF) class, poor R-wave progression, superimposed myocarditis, and higher mortality. Thrombosis/embolism was associated with NYHA CHF class ≥ 3, right ventricular end-diastolic diameter ≥ 3 cm, right atrium volume ≥ 67 mL, left ventricle end-diastolic diameter ≥ 6.3 cm, and velocity time integral ≤ 11.2 cm. Sustained VT was associated with premature ventricular contractions (PVCs), low QRS voltage, and atrioventricular block. PVCs > 500/day were predictive of defibrillator intervention. Fatal outcomes were associated with E wave/A wave ratio > 1.9, left ventricle ejection fraction < 35%, NYHA CHF class ≥ 3, VT, and myocarditis.

Frequent PVCs, non-sustained VT, low QRS voltage, and signs of systolic dysfunction on echocardiogram are predictors of life-threatening events in patients with LVNC.

Core Tip: Left ventricular noncompaction (LVNC) is associated with a high risk of thrombosis/embolism and arrhythmias. We investigated the predictors of these types of events in 125 patients with LVNC over an average follow-up of 14 months. Following electrocardiography, echocardiography, 24-hour electrocardiogram monitoring, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging, cardiac computed tomography, genetic testing, myocardial morphological examination, and laboratory examination, the acquired data were analyzed. Frequent premature ventricular contractions, non-sustained ventricular tachycardia, low QRS voltage, and signs of systolic dysfunction must be considered for risk assessment in patients with LVNC.

- Citation: Blagova OV, Varionchik NV, Pavlenko EV, Sedov VP, Lutokhina YA. Predictors of life-threatening events in adult patients with left ventricular noncompaction. World J Cardiol 2025; 17(12): 112126

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8462/full/v17/i12/112126.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4330/wjc.v17.i12.112126

Left ventricular noncompaction (LVNC) is the excessive development of muscle trabeculae and the formation of deep recesses. It essentially forms a left ventricular myocardium with a two-layered structure[1,2]. LVNC is a visually recognizable pathology of the myocardial structure with a genetic component. This is evident by the association of LVNC with congenital heart defects, arrhythmogenic, hypertrophic and restrictive cardiomyopathies, the presence of pathogenic mutations in a wide spectrum of genes responsible for cardiac structure and function, and the high frequency of familial forms of LVNC[3,4]. The prevalence of LVNC is estimated to be 0.014%-3% in the adult population[5,6]. It occurs in 0.05%-0.27% of adults referred for echocardiography[7].

The pathogenesis of LVNC typically occurs during embryogenesis[8]. It is possible for excessive left ventricular trabeculation to be present secondary to physiological and pathological conditions including pregnancy[9], intensive sports training[10], sickle cell anemia[11], etc. However, the evidence supporting the secondary nature of LVNC is not con

While LVNC was included as an unclassifiable cardiomyopathy in the 2007 European classification[14], it is no longer considered a cardiomyopathy according to the 2023 European Society of Cardiology cardiomyopathy recommendations[15]. LVNC has typical clinical features that make it an independent nosological unit. Clinical manifestations of LVNC are derived from its pathogenesis including inadequate blood supply under the noncompacted layer. Fibrosis formation leads to life-threatening arrhythmia and conduction abnormalities. Systolic dysfunction, ventricular dilatation, and deep recesses contribute to thrombi formation and thromboembolism. These complications make LVNC one of the most unfavorable forms of cardiomyopathies. Currently, there are no special guidelines regarding therapeutic management of patients with LVNC. Risk stratification of patients with LVNC and recommendations for the prevention of specific complications have not been developed.

It is essential to study predictors of adverse events in patients with LVNC to develop specific treatment approaches. The objective of this study was to identify the factors that predict the occurrence of arrhythmic, thromboembolic events and adverse outcomes including death and heart transplantation in adult patients with LVNC.

This was an observational study conducted at the Department of Cardiology, University Clinic, I.M. Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University (Sechenov University), Moscow, Russia. The majority of patients were recruited when treated at the hospital between January 2010 and March 2019. Several patients were observed as outpatients. The end of the follow-up period was March 2020. The study is mostly prospective, partly to a small extent retrospective (several patients were recruited retrospectively and then called for follow-up and further observed prospectively).

Inclusion criteria were age older than 18 years and the presence of signs of LVNC from at least one of the following imaging techniques: Ratio of noncompact to compact layers more than 2:1 by echocardiography or more than 2.3:1 by cardiac multispiral computed tomography or cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI); visualization of more than 3 trabeculae in the left ventricle at the end of diastole; synchronous movement of compact and noncompact layers in systole; and the presence of interlacunar blood flow[1,16-19].

Exclusion criteria were age less than 18 years and refusal to participate in the study.

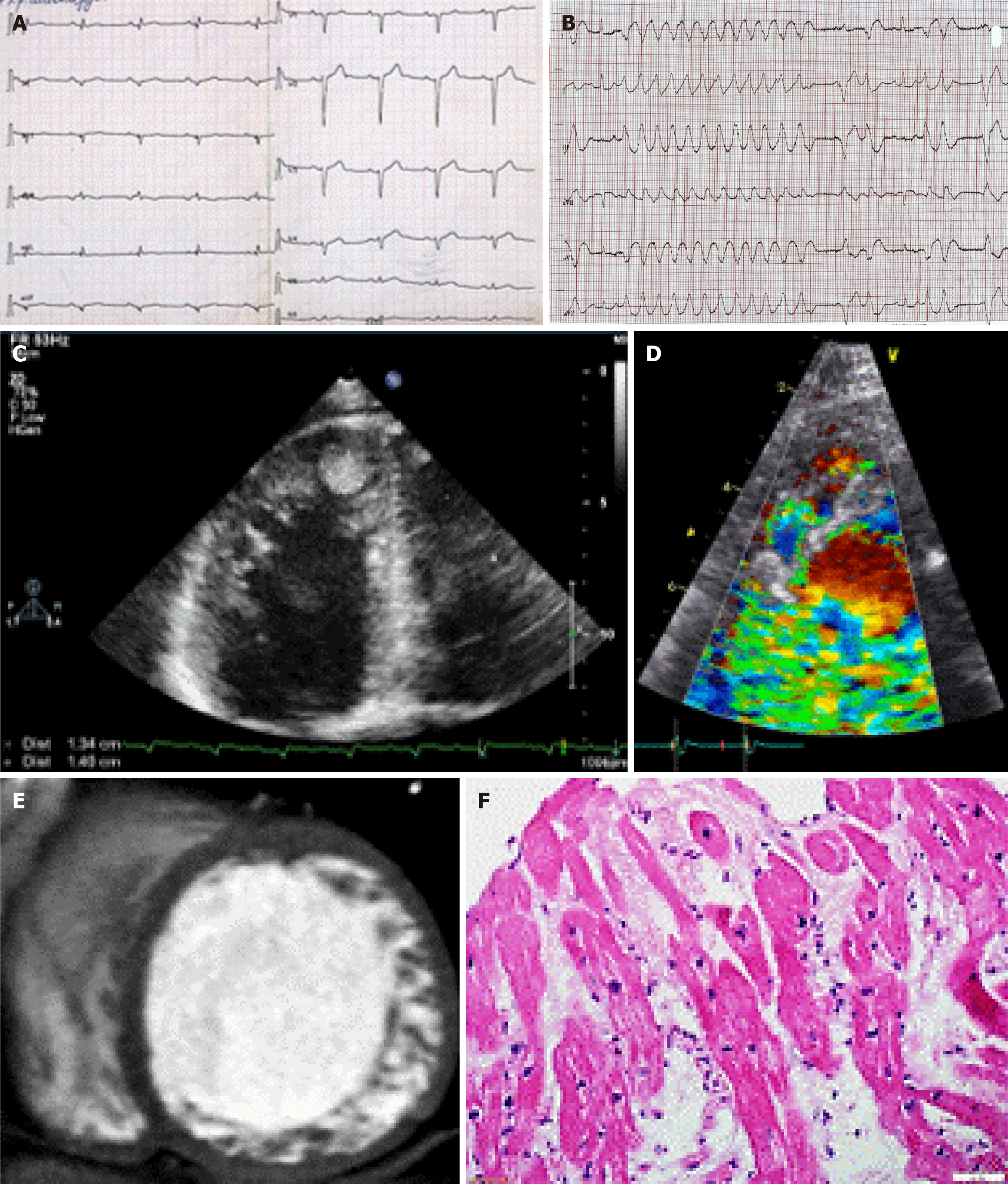

Electrocardiography (ECG, n = 125), echocardiography (n = 125), 24-hour ECG monitoring (n = 125), coronary angiography (n = 33), cardiac MRI (n = 60), cardiac computed tomography (n = 90), and laboratory tests were conducted. The diagnosis of LVNC was confirmed by two imaging modalities in 74 cases and by three imaging modalities in 21 cases (Figure 1). To diagnose superimposed myocarditis we assessed the level of anti-heart antibodies by indirect immunofluorescence (n = 102) and/or performed pathological examination of the myocardium (n = 26), including endomyo

Almost half of the patients (n = 51) underwent genetic testing for myosin heavy chain 7 (MYH7), myosin binding protein C3 (MYBPC3), tropomyosin 1, troponin I3, troponin T2, actin, alpha, cardiac muscle 1, tafazzin, Z-band alternatively spliced PDZ-motif protein, myosin light chain 2, myosin light chain 3, and transmembrane protein 43 on the Ion Torrent platform using the Ion AmpliSeq oligoprimer panel (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, United States) with all findings confirmed by Sanger sequencing. Genetic testing was performed at the Genetics Medical Laboratory at Petrovsky National Research Centre of Surgery (Moscow, Russia).

Primary endpoints were death, heart transplantation, combined endpoint (death + heart transplantation), and sudden cardiac death (SCD). Secondary endpoints were intracardiac thrombosis, embolic events, myocardial infarction (necrosis), sustained ventricular tachycardia (VT), and appropriate implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) interventions.

Statistical processing of the data was performed using SPSS software package version 21 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States). Quantitative indicators were summarized as mean ± SD or median with first and third quartiles. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to assess normality of the distribution. The Student’s t-test, Mann-Whitney U test, and Wilcoxon tests were applied to assess the statistical significance of differences in quantitative variables. Fisher’s exact test (using a 2 × 2 contingency table) was performed to compare qualitative binary variables. Differences were considered significant when the P-value was < 0.05.

Correlation analysis determined potential predictors. For continuous variables that confirmed their significance, the area under the curve (AUC) was estimated using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves. Thresholds for continuous variables were determined using ROC analysis (points with the closest sensitivity and specificity). Linear regression, logistic regression, and Cox regression analysis were performed for the identification of possible predictors of adverse outcomes. Univariate analysis was performed on all variables that showed significance, and multivariate analysis was performed on the same variables.

The study included 125 adult patients with LVNC, including 74 males (59.2%) and 51 females (40.8%) with a mean age of 46.4 ± 15.1 years. The median follow-up was 14 months (range: 4.0-41.0). The principal manifestations of LVNC were heart failure [n = 46, 37.0%, New York Heart Association (NYHA) class III-IV], rhythm abnormalities (n = 92, 73.6%), conduction abnormalities (n = 66, 52.8%; Figure 1), thromboembolic events (n = 29, 23.2%; Figure 1), and SCD (n = 11, 8.9%). Echocardiography showed a decrease in myocardial contractility and dilatation of the left heart chambers. The mean left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was 38.6% ± 14.0% (Table 1).

| Parameter | Frequency or mean value, n = 125 |

| Age, years | 46.4 ± 15.1 |

| Sex, male, % | 59.2 |

| Death, % | 14.4 |

| Transplantation, % | 6.4 |

| Death + transplantation, % | 19.2 |

| Sudden cardiac death, % | 8.9 |

| LVEF, % | 38.6 ± 14.0 |

| LVEDD, cm | 6.1 ± 0.9 (3.8-8.2) |

| LVEDV, mL | 158.1 ± 67.8 (29.0-501.0) |

| LVESV, mL | 102.3 ± 58.6 (19.0-386.0) |

| E/A ratio | 1.33 (0.95-2.30) |

| IVS thickness, mm | 10.0 (8.0-11.0) |

| LA volume, mL | 97.1 ± 38.1 (30.0-190.0) |

| RA volume, mL | 63.0 (47.0-88.3) |

| RVEDD, cm | 3.0 ± 0.7 |

| SPAP, mmHg | 36.1 ± 16.9 |

| Ventricular tachycardia, % | 50.4 |

| Premature ventricular beats > 500/day, % | 47.2 |

| Atrial fibrillation/flutter, % | 30.4 |

| Sick sinus syndrome, % | 10.5 |

| AV block, I-III degree, % | 14.5 |

| Bundle branch block, % | 42.3 |

| NYHA chronic heart failure, III-IV, % | 36.8 |

| Thrombosis + embolism, % | 23.2 |

| Presence of superimposed myocarditis, % | 54.0 |

| Myocardial infarction (necrosis), % | 15.0 |

| Angina pectoris, % | 20.0 |

| Arterial hypertension, % | 41.8 |

The diagnosis of superimposed myocarditis was based on the results of the myocardial morphological study (Figure 1) or complex noninvasive clinical, laboratory, and instrumental examination based on a previously developed algorithm[20]. The frequency of combined LVNC and myocarditis was 54.0% (n = 67). Pathogenic mutations were detected in 13 patients (10.4%) in the MYBPC3, MYH7, titin, desmoplakin, desmin, and lysosomal associated membrane protein 2 genes. Variants with unknown clinical significance in the MYH7, MYBPC3, actin, alpha, cardiac muscle 1, and transmembrane protein 43 genes were detected in 7 patients.

The incidence of all fatal outcomes in patients with LVNC was 14.4% (n = 18). Heart transplantation was performed in 8 patients of which 2 patients died after surgery. The frequency of achieving the combined endpoint of death + transplantation was 19.2% (n = 24). In 6 patients SCD was definite, and in 5 patients SCD was assumed with high probability (8.9%, n = 11). In the remaining cases the cause of death was terminal heart failure, thromboembolic events, or complications after heart transplantation.

Lethal outcomes were strongly associated with more severe left ventricular dysfunction [LVEF: 26.6% ± 12.3% vs 40.7% ± 13.2%, P < 0.001; E/A ratio: 2.47 ± 0.99 vs 1.50 ± 0.75, P < 0.001; left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT) velocity-time integral (VTI): 8.6 ± 2.1 vs 12.7 ± 3.6, P < 0.001; NYHA chronic heart failure (CHF) severity class: 3 (2.00-3.25) vs 2 (1.00-3.00), P = 0.001; presence of VT: 77.8% vs 48.6%, P = 0.011, including non-sustained VT (72.2% vs 45.8%, P = 0.014); and the presence of superimposed myocarditis: 83.3% vs 41.1%, P = 0.006]. In all the lethal cases, patients had signs of CHF at the time of LVNC diagnosis.

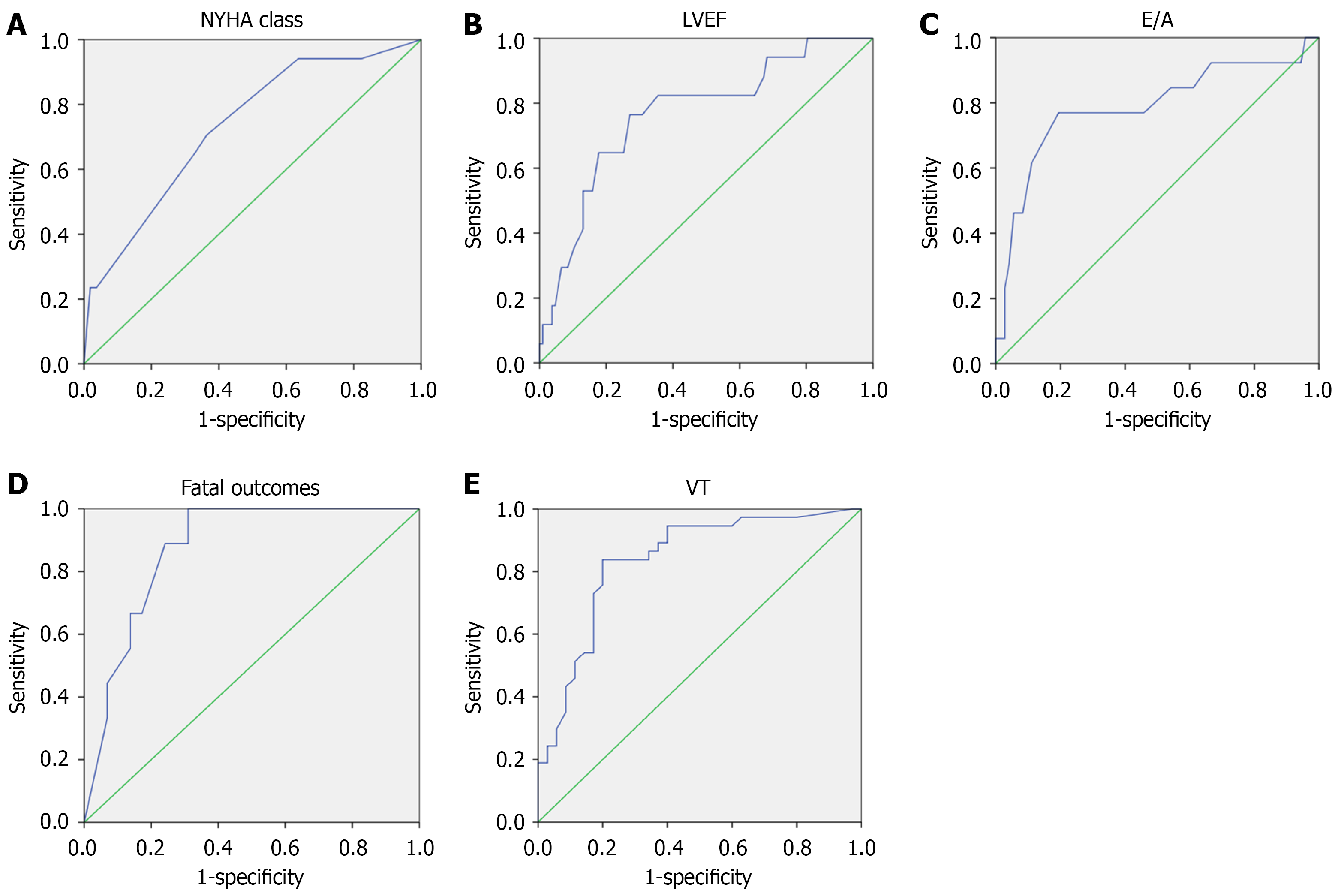

In the ROC analysis (Figure 2A-C), the variables with the greatest prognostic significance for the development of a fatal outcome were E/A ratio (AUC = 0.786, P = 0.001), LVEF (AUC = 0.767, P < 0.001), NYHA CHF class (AUC = 0.731, P = 0.002), and LVOT VTI (AUC = 0.820, P = 0.002). The ROC analysis thresholds were: E/A ratio = 1.92 (sensitivity: 77%; specificity: 76%); LVEF = 32.5% (sensitivity: 77%; specificity: 73%); and LVOT VTI = 10.7 (sensitivity: 70%, specificity: 68%). The presence of myocarditis was also associated with a fatal outcome (sensitivity: 84%; specificity: 51%; P = 0.02).

In the univariate regression analysis using the logistic regression method, all variables retained their significance (E/A ratio > 1.9, P = 0.001; LVEF < 35%, P = 0.001; LVOT VTI < 11, P = 0.02; NYHA CHF class ≥ 3, P = 0.007; presence of myocarditis, P = 0.013; and presence of VT, P = 0.025). A mathematical model including all predictors was obtained (P = 0.036), and ROC analysis was performed showing an AUC of 0.874 (P < 0.001; Figure 2D).

We also analyzed predictors of arrhythmic and thromboembolic adverse events, which along with CHF progression are specific mechanisms of death in patients with LVNC, including SCD. The most common arrhythmias were ventricular rhythm disturbances. Non-sustained VT was present in 45.6% of cases, sustained VT in 13.6% of cases, and premature ventricular contractions (PVCs) in 47.2% of cases. The most common conduction disturbances were bundle branch blocks. Left bundle branch block was present in 22.4% of cases, anterior or posterior hemiblock in 13.6%, and right bundle branch block in 11.2% of cases. Atrioventricular blocks (grade I-III) were detected in 14.5% of cases.

Non-sustained VT and sustained VT were associated with the severity of CHF (P = 0.01), reduced LVEF (34.8% vs 42.4%, P = 0.002), presence of myocarditis (69.4% vs 38.7%, P = 0.001), poor R-wave progression in the chest leads (49.1% vs 23.6%, P = 0.005), low QRS voltage (22.8% vs 5.4%, P = 0.007), and prolonged QRS duration (119 ms vs 100 ms, P = 0.001; Table 2). Mortality in patients with VT (non-sustained and sustained) was significantly higher than in patients without these arrhythmias (20.6% vs 6.5%, P = 0.019). All the patients who developed sustained VT previously had signs of CHF at the time of LVNC diagnosis.

| Parameter | Ventricular tachycardia (non-sustained and sustained) | P value | |

| Present | Absent | ||

| n | 65 | 60 | |

| Mortality, % | 20.6 | 6.5 | 0.019 |

| NYHA CHF class | 2.25 (1.90-3.00) | 2.00 (0.75-3.00) | 0.010 |

| Myocarditis, % | 69.4 | 38.7 | 0.001 |

| LVEF, % | 34.8 ± 13.6 | 42.4 ± 13.4 | 0.002 |

| LVEDD, cm | 6.2 ± 0.8 | 5.9 ± 0.9 | 0.035 |

| SPAP, mmHg | 40.7 ± 16.4 | 31.8 ± 16.3 | 0.015 |

| LA volume, mL | 103.8 ± 38.5 | 90.5 ± 36.8 | 0.026 |

| Low QRS voltage by ECG, % | 22.8 | 5.4 | 0.007 |

| QRS duration by ECG, ms | 119 (100-140) | 100 (90-114) | 0.001 |

| Poor R wave progression, % | 49.1 | 23.6 | 0.005 |

| LBBB or RBBB, % | 56.5 | 27.9 | 0.001 |

| Duration of disease, months | 60 (16.0-133.5) | 24.5 (24.5-70.8) | 0.026 |

ROC analysis showed a high prognostic value of these predictors (Table 3). The threshold with the optimal ratio of sensitivity and specificity according to the ROC analysis was 2.25 for NYHA CHF class, 6.1 cm for left ventricular end diastolic diameter (LVEDD), 39.5% for LVEF, 105 ms for QRS duration, and 32 mmHg for systolic pulmonary artery pressure.

| Variable | AUC | Asymptotic significance | Asymptotic 95%CI | |

| Lower limit | Upper limit | |||

| NYHA CHF class | 0.630 | 0.013 | 0.532 | 0.727 |

| Poor R wave progression | 0.627 | 0.021 | 0.522 | 0.732 |

| Low QRS voltage | 0.587 | 0.110 | 0.482 | 0.692 |

| QRS duration | 0.678 | 0.001 | 0.579 | 0.777 |

| Myocarditis | 0.653 | 0.003 | 0.556 | 0.750 |

| LVEF | 0.654 | 0.003 | 0.558 | 0.751 |

| LVEDD | 0.608 | 0.039 | 0.508 | 0.709 |

| SPAP | 0.684 | 0.003 | 0.573 | 0.795 |

In the univariate regression analysis, all indicators retained their significance except left ventricular end diastolic volume (LVEDV): NYHA CHF class ≥ 3 (P = 0.03); LVEDD > 6.1 cm (P = 0.048); LVEF < 40% (P = 0.04); QRS duration > 105 ms (P = 0.01); systolic pulmonary artery pressure > 32 mmHg (P = 0.006); presence of myocarditis (P < 0.001); poor R-wave progression in the chest leads (P = 0.005); and low QRS voltage (P = 0.02). The mathematical model including the significant predictors was developed (P = 0.001) with an AUC of 0.837 (P < 0.001; Figure 2E).

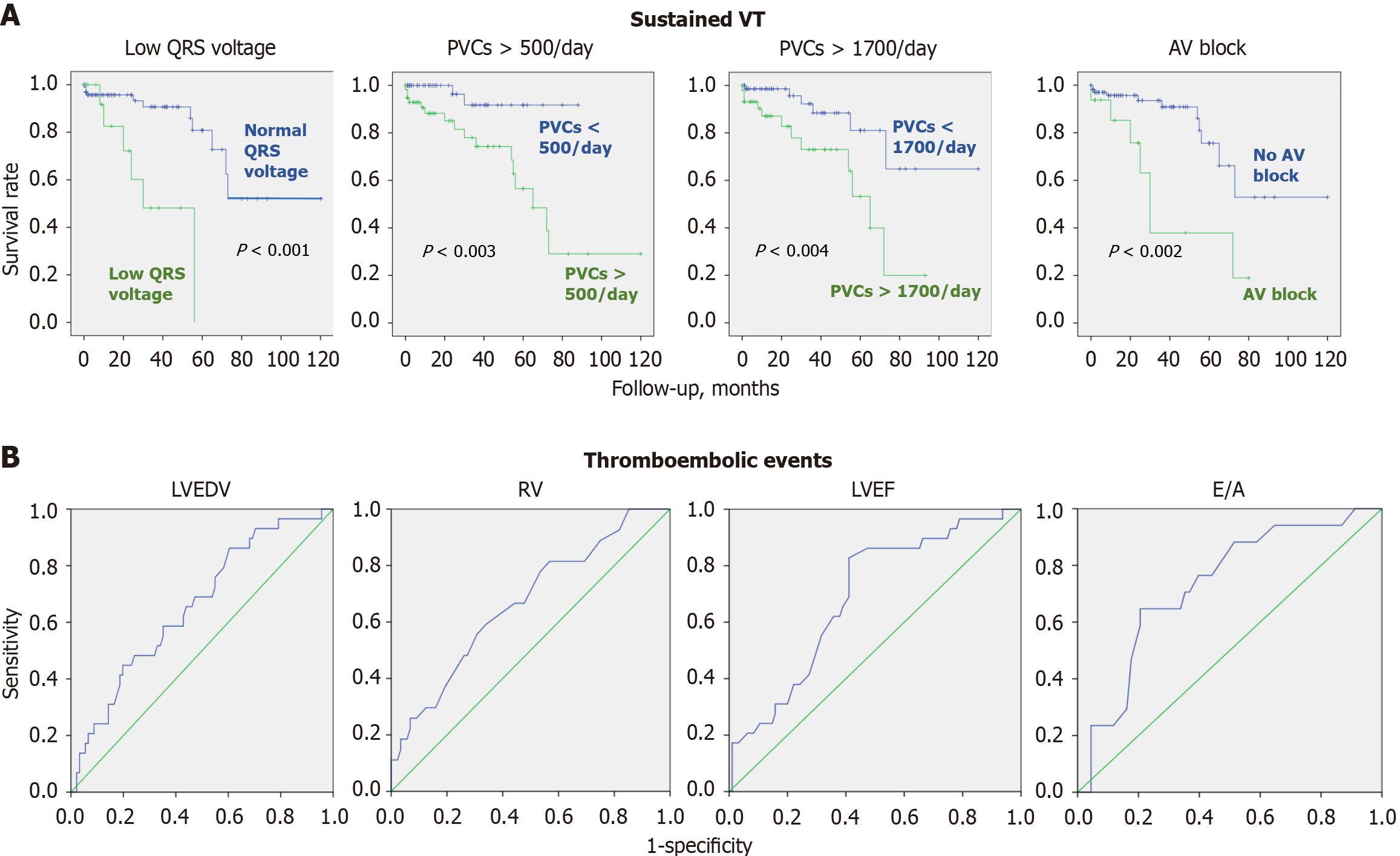

Predictors of sustained VT were analyzed separately. The most significant prognostic indicator for the development of sustained VT according to the results of the ROC analysis was the presence of frequent PVCs at the time of LVNC diagnosis (AUC = 0.75, P = 0.001). The threshold of 1700 PVCs per 24 hours had a sensitivity of 67% and a specificity of 68%. Regression analysis was performed using Cox regression, and Kaplan-Meier curves were constructed for the development of sustained VT (Figure 3). In a single-factor Cox regression analysis, low QRS voltage had the most significance for the development of sustained VT (P < 0.001) because low voltage reflects the severity of myocardial lesions and electrical heterogeneity of the myocardium.

Pacemakers were implanted in 7 patients. Defibrillators were implanted in 38 patients with LVNC, including 28 implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICDs) and 10 cardiac resynchronization therapy with a defibrillator. At a mean follow-up of 14 months, appropriate ICD interventions for VT/ventricular fibrillation (anti-tachycardia pacing and/or defibrillation) were recorded in 34.2% of cases. ICD interventions were associated with sustained VT known in the anamnesis at the time of LVNC diagnosis. The association of ICD interventions with the presence of frequent PVCs was noted (Table 4). This variable should be accounted for when deciding the appropriateness of an ICD implantation for patients with LVNC. Univariate regression analysis for PVCs > 500/day revealed a P-value of 0.008[21,22]. In the ROC analysis of the quantitative index of the PVC frequency (AUC = 0.793, P = 0.004), the threshold value was more than 1300 PVCs/day (sensitivity 64% and specificity 68%).

| Parameter | Appropriate ICD interventions | P value | |

| Present | Absent | ||

| n | 14 | 24 | |

| Myocarditis, % | 84.6 | 56 | 0.078 |

| Mortality, % | 15.4 | 16 | 0.672 |

| PVC > 500 per 24 hours, % | 92.3 | 36 | 0.001 |

| Sustained VT, % | 100 | 0 | < 0.001 |

| Non-sustained VT, % | 69.2 | 84 | 0.257 |

| LVEF, % | 37.5 ± 10.2 | 33.2 ± 14.1 | 0.168 |

Definite emboli were clinically recorded in 10 patients (8.0%), with 7 patients having had a stroke, 1 patient having had a thromboembolism in the renal artery, 1 patient having had an embolism in the ophthalmic artery, and the autopsy-confirmed development of an embolic myocardial infarction in 1 patient without atherosclerotic lesions of the coronary arteries. Myocardial infarction (necrosis) was recorded in 8 patients with intact coronary arteries and proven intracardiac thrombosis, making the embolic mechanism of infarction the most likely.

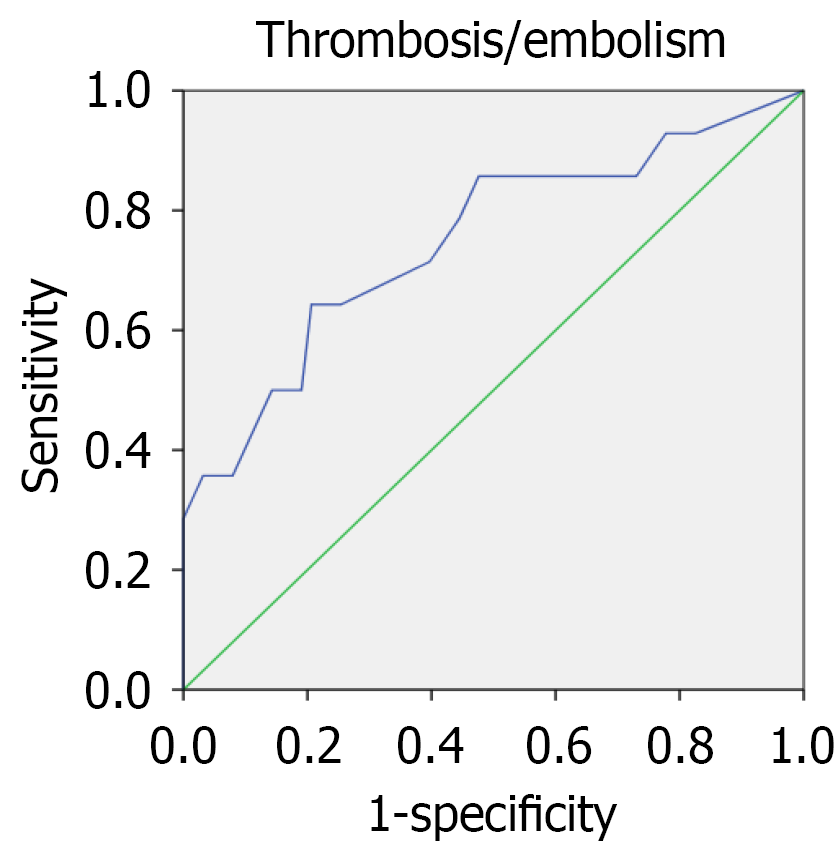

Cumulatively, intracardiac thrombosis and embolic events were reported in 22.4% of cases. In 19 cases oral anticoagulants were not prescribed at the time of the event, and in 7 cases thrombosis or embolism developed when anticoagulants were not taken regularly or were discontinued. The development of thrombosis and embolism was strongly associated with increased left and right ventricular dimensions [LVEDD: 6.5 cm vs 5.9 cm, P = 0.006; left ventricular LVEDV: 184.2 mL vs 149.6 mL, P = 0.005; left ventricular end-systolic volume: 126.7 mL vs 94.1 mL, P = 0.01; right ventricle end diastolic diameter (RVEDD): 3.4 cm vs 2.9 cm, P = 0.002], increased left atrium volume (109.3 mL vs 93.2 mL, P = 0.014), impaired left ventricular systolic (LVEF: 31.3% vs 40.8%, P = 0.001) and diastolic function (Е/А ratio: 2.1 vs 1.5, P = 0.01), and an increase in the NYHA class of heart failure (class 3 vs class 2, P = 0.006; Table 5 and Figure 3). There were no differences in the incidence of atrial fibrillation between patients with and without thrombosis/embolism. Among patients with atrial fibrillation, 64% had not received anticoagulants at the time of thromboembolic complications (atrial fibrillation was diagnosed at the same time or after the embolism). All patients with atrial fibrillation without thromboembolic complications were prescribed anticoagulant therapy. CHF symptoms at the LVNC diagnosis were associated with higher risk of thromboembolism.

| Parameter | Thrombosis and/or embolism | P value | |

| Present | Absent | ||

| n | 28 | 97 | |

| NYHA CHF class | 3 (2.0-3.0) | 2 (1.0-3.0) | 0.006 |

| LVEF, % | 31.3 ± 11.7 | 40.8 ± 13.9 | 0.001 |

| LVEDD, cm | 6.5 ± 0.9 | 5.9 ± 0.8 | 0.006 |

| LVEDV, mL | 184.2 ± 60.8 | 149.6 ± 66.5 | 0.005 |

| LVESV, mL | 126.7 ± 62.9 | 94.1 ± 53.4 | 0.010 |

| LA volume, mL | 109.3 ± 31.8 | 93.2 ± 39.2 | 0.014 |

| RVEDD, cm | 3.4 ± 0.8 | 2.9 ± 0.6 | 0.002 |

| Е/А ratio | 2.1 ± 0.8 | 1.5 ± 0.9 | 0.010 |

| LVOT VTI | 10.0 ± 3.5 | 12.7 ± 3.5 | 0.016 |

| Atrial fibrillation, % | 39.3 | 27.8 | 0.210 |

| Duration of disease, months | 22.5 (4.8-51.0) | 53.0 (13.0-120.0) | 0.020 |

According to the ROC analysis data (Table 6), the threshold with the optimal sensitivity to specificity ratio for CHF was 2.25 (i.e., NYHA class 2-3), for LVEF was 35.5%, for LVEDD was 6.3 cm, for LVEDV was 153 mL, for RVEDD was 3.1 cm, for left atrium volume was 98 mL, and for E/A ratio was 1.65. In the univariate regression analysis, all associated factors influenced the prognosis significantly including: NYHA CHF class ≥ 3 (P = 0.013); LVEF < 35% (P = 0.014); LVEDD > 6.3 cm (P = 0.008); LVEDV > 153 mL (P = 0.046); RVEDD > 3.1 cm (P = 0.013); left atrium volume > 98 mL (P = 0.043); and E/A ratio > 1.65 (P = 0.047). The mathematical model, which included the E/A ratio, LVEF, LVEDV, and RVEDD had a P-value of 0.03. The ROC analysis showed an AUC of 0.749 (P = 0.004; Figure 4).

| Variable | AUC | Asymptotic significance | Asymptotic 95%CI | |

| Lower limit | Upper limit | |||

| LVEDD | 0.671 | 0.006 | 0.555 | 0.786 |

| LVEDV | 0.674 | 0.005 | 0.564 | 0.784 |

| LVEF | 0.688 | 0.002 | 0.583 | 0.793 |

| RVEDD | 0.669 | 0.009 | 0.550 | 0.788 |

| LA volume | 0.655 | 0.014 | 0.550 | 0.759 |

| Е/А ratio | 0.707 | 0.010 | 0.575 | 0.833 |

| NYHA CHF class | 0.667 | 0.007 | 0.546 | 0.787 |

Intracardiac thrombosis, systemic emboli, ventricular arrhythmias, and SCD were typical complications in patients with LVNC. These observations reflect distinctive features of this cardiomyopathy. The myocardium structure with prominent trabeculae and deep recesses facilitates thrombi formation, and systolic dysfunction exacerbates the process. Inadequate blood supply under the noncompacted layer and fibrosis formation leads to electrical instability and arrhythmias.

Myocarditis was diagnosed in half of our patients. Pathogenic mutations were detected in 13 patients with the simultaneous presence of myocarditis and pathogenic mutations in 8 patients. This combination suggests that genetically altered myocardium predisposes patients to inflammation, refuting the hypothesis of secondary occurrence of hypertrabeculation in patients with severe myocarditis. Our analysis revealed a significant influence of myocarditis on the development of several complications in LVNC.

The most common arrhythmic events were ventricular rhythm disturbances, namely sustained VT, non-sustained VT, and frequent PVCs. Atrial fibrillation was less common, especially in patients with atrial dilatation. There was an association between ventricular rhythm disturbances and a decrease in LVEF, the severity of CHF, and the presence of superimposed myocarditis. ECG in patients with VT frequently revealed poor R-wave progression in the chest leads, prolonged QRS complex duration, and low QRS voltage, reflecting diffuse myocardial damage. Low QRS voltage is considered one of the diagnostic criteria for arrhythmogenic RV cardiomyopathy[23], and some studies have shown its correlation with adverse outcomes in other cardiomyopathies[24]. However, the prognostic value of low QRS voltage in LVNC has not been investigated.

Currently, there are no clear recommendations for ICD implantation in patients with LVNC. According to the European Society of Cardiology guidelines, ICD implantation is indicated in patients with LVNC using the same criteria as in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy IIaC (LVEF < 35%, presence of sustained VT)[25]. In patients with preserved LVEF but late gadolinium enhancement on MRI, it is suggested to consider a family history of SCD and the presence of non-sustained VT[26]. A meta-analysis of the efficacy of ICD therapy in 275 patients with LVNC showed that appropriate interventions were registered in 25% of patients, but the analysis of appropriate shock predictors was not performed over a follow-up period of 3 years[27].

In the present study the incidence of appropriate ICD interventions exceeded 32% with a significantly shorter follow-up period (average 14 months). We established a prognostic role of frequent PVCs to appropriate interventions: A threshold of 1300 PVCs/day indicated intervention was necessary. The frequency of PVCs should be considered an additional selection criterion for ICD implantation. Additionally, the prognostic role of myocarditis was demonstrated for the first time after diagnosis in 85% of patients with interventions compared with 56% of patients without interventions.

The incidence of thromboembolic complications was 22.4%, which is comparable with the results of other studies (0%-38%)[28]. Intracardiac thrombus formation in LVNC is favored due to the presence of a loose, spongy, noncompact layer with deep intertrabecular lacunae and a decrease in left ventricular systolic function. However, in our study massive thrombosis did not always lead to embolism. The presence of thrombi in heart chambers was not confirmed in every case of embolism. We can assume that in these cases the thrombus was in the intertrabecular lacunae, making diagnosis difficult, or that the thrombus was completely detached with the development of an embolism.

There were no significant differences in the frequency of atrial fibrillation and atrial flutter between patients with and without thrombosis/embolism. Atrial fibrillation and atrial flutter are related to the high frequency of anticoagulant prescription to treat these arrhythmias. Thromboembolic complications were associated with heart chamber dilation, reduced left ventricular systolic and impaired diastolic function, and deterioration in the NYHA CHF class. These parameters can be used as additional criteria for determining the prescription of anticoagulants in patients with LVNC.

Previously, an attempt to clarify the indications for anticoagulant therapy in patients with LVNC was made by Stöllberger et al[29] in 169 patients with LVNC, including those without atrial fibrillation. They concluded that the CHADS2 and CHADS2-VASc scales can be used to assess the risk of thromboembolic events in patients with LVNC independent of atrial fibrillation. However, this approach is currently not widely used in clinical practice. The expert document on arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy considers atrial fibrillation and previous thromboembolic events or left ventricular thrombosis (class I, evidence B level) and left ventricular dysfunction (class IIb, evidence B level) as indications for the prescription of anticoagulants[30].

A review discussed the appropriateness of anticoagulants in LVNC irrespective of the degree of myocardial dys

A common complication of LVNC is the development of myocardial necrosis (16% in the present study), including embolism to the coronary arteries[31]. This mechanism was confirmed at autopsy in 1 patient. It was assumed with high probability due to the absence of other causes in several other patients. In more than half of our patients with myocardial infarction, the coronary arteries were intact. Other mechanisms of necrosis in LVNC include myocarditis[31], impaired blood supply under the noncompact layer, and coagulation pathology leading to thrombosis in the coronary arteries (data from our clinical experience).

The main predictors of mortality in this study were severity of CHF (NYHA class 3 or more), LVEF less than 35%, LVOT VTI less than 11.0 cm, E/A ratio greater than 1.9, non-sustained VT, and superimposed myocarditis. The im

Patients with LVNC have several characteristic features that distinguish them from other cardiomyopathies and lead to the development of specific complications. Multicenter prospective studies are needed to assess the prognostic significance of the predictors of life-threatening LVNC complications identified in this study to develop differentiated recommendations for their prevention.

One of the limitations of this study was the relatively small sample size. However, it is important to note that this is the largest single-center cohort of adult patients with LVNC. The single-center design of our study allowed our research team to directly monitor the outcomes of each patient included in the study, and patients were assessed according to a single protocol (a feature that is hard to control in multicenter studies). The relatively short follow-up period may underestimate the incidence of adverse outcomes. However, the incidence of endpoints was high even during the follow-up period that ranged from 4 months to 41 months, emphasizing the aggressive course of LVNC and the importance of searching for predictors of fatal outcomes. Another limitation of the present study was the inability to perform genetic testing in all patients due to financial constraints. Genetic testing could improve the accuracy of predicting adverse events. However, the genetic nature of this cardiomyopathy is not fully understood, and low DNA diagnostic yield is typical for LVNC, requiring the use of broad panels or whole exome sequencing.

LVNC in adults is associated with a high risk of life-threatening conditions. The main predictors of sustained VT were frequent PVCs, low QRS voltage, and atrioventricular block. The presence of non-sustained VT was strongly associated with a higher mortality rate. The presence of more than 500 PVCs per day indicates the consideration of appropriate ICD interventions. Predictors of thromboembolism and criteria for the anticoagulant therapy administration should include NYHA CHF class ≥ 3, RVEDD ≥ 3 cm, right atrium volume ≥ 67 mL, LVEDD ≥ 6.3 cm, and LVOT VTI reduction ≤ 11.2 cm. Superimposed myocarditis should be actively detected and treated.

| 1. | Captur G, Muthurangu V, Cook C, Flett AS, Wilson R, Barison A, Sado DM, Anderson S, McKenna WJ, Mohun TJ, Elliott PM, Moon JC. Quantification of left ventricular trabeculae using fractal analysis. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2013;15:36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 149] [Cited by in RCA: 160] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Yang ZG, Liu ZJ, Zhang XX, Wang L. Prognostic factors associated with left ventricular non-compaction: A PRISMA-compliant meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2022;101:e30337. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Hirono K, Ichida F. Left ventricular noncompaction: a disorder with genotypic and phenotypic heterogeneity-a narrative review. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther. 2022;12:495-515. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Finsterer J, Stöllberger C. Left Ventricular Noncompaction Syndrome: Genetic Insights and Therapeutic Perspectives. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2020;22:84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Oechslin EN, Attenhofer Jost CH, Rojas JR, Kaufmann PA, Jenni R. Long-term follow-up of 34 adults with isolated left ventricular noncompaction: a distinct cardiomyopathy with poor prognosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;36:493-500. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 853] [Cited by in RCA: 813] [Article Influence: 31.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Almeida AG, Pinto FJ. Non-compaction cardiomyopathy. Heart. 2013;99:1535-1542. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ronderos R, Avegliano G, Borelli E, Kuschnir P, Castro F, Sanchez G, Perea G, Corneli M, Zanier MM, Andres S, Aranda A, Conde D, Trivi M. Estimation of Prevalence of the Left Ventricular Noncompaction Among Adults. Am J Cardiol. 2016;118:901-905. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Rojanasopondist P, Nesheiwat L, Piombo S, Porter GA Jr, Ren M, Phoon CKL. Genetic Basis of Left Ventricular Noncompaction. Circ Genom Precis Med. 2022;15:e003517. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Gati S, Papadakis M, Papamichael ND, Zaidi A, Sheikh N, Reed M, Sharma R, Thilaganathan B, Sharma S. Reversible de novo left ventricular trabeculations in pregnant women: implications for the diagnosis of left ventricular noncompaction in low-risk populations. Circulation. 2014;130:475-483. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 230] [Cited by in RCA: 225] [Article Influence: 18.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Poscolieri B, Bianco M, Vessella T, Gervasi S, Palmieri V, Zeppilli P. Identification of benign form of ventricular non-compaction in competitive athletes by multiparametric evaluation. Int J Cardiol. 2014;176:1134-1136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Piga A, Longo F, Musallam KM, Veltri A, Ferroni F, Chiribiri A, Bonamini R. Left ventricular noncompaction in patients with β-thalassemia: uncovering a previously unrecognized abnormality. Am J Hematol. 2012;87:1079-1083. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Caselli S, Ferreira D, Kanawati E, Di Paolo F, Pisicchio C, Attenhofer Jost C, Spataro A, Jenni R, Pelliccia A. Prominent left ventricular trabeculations in competitive athletes: A proposal for risk stratification and management. Int J Cardiol. 2016;223:590-595. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Pavlenko EV, Blagova OV, Varionchik NV, Nedostup AV, Sedov VP, Polyak ME, Zaklyazminskaya EV. Register of adult patients with noncompact left ventricular myocardium: classification of clinical forms and a prospective assessment of progression. Russ J Cardiol. 2019;2:12-25. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 14. | Elliott P, Andersson B, Arbustini E, Bilinska Z, Cecchi F, Charron P, Dubourg O, Kühl U, Maisch B, McKenna WJ, Monserrat L, Pankuweit S, Rapezzi C, Seferovic P, Tavazzi L, Keren A. Classification of the cardiomyopathies: a position statement from the European Society Of Cardiology Working Group on Myocardial and Pericardial Diseases. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:270-276. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1766] [Cited by in RCA: 1943] [Article Influence: 102.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Arbelo E, Protonotarios A, Gimeno JR, Arbustini E, Barriales-Villa R, Basso C, Bezzina CR, Biagini E, Blom NA, de Boer RA, De Winter T, Elliott PM, Flather M, Garcia-Pavia P, Haugaa KH, Ingles J, Jurcut RO, Klaassen S, Limongelli G, Loeys B, Mogensen J, Olivotto I, Pantazis A, Sharma S, Van Tintelen JP, Ware JS, Kaski JP; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2023 ESC Guidelines for the management of cardiomyopathies. Eur Heart J. 2023;44:3503-3626. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 699] [Cited by in RCA: 1495] [Article Influence: 498.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (8)] |

| 16. | Petersen SE, Selvanayagam JB, Wiesmann F, Robson MD, Francis JM, Anderson RH, Watkins H, Neubauer S. Left ventricular non-compaction: insights from cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:101-105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 804] [Cited by in RCA: 838] [Article Influence: 39.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Jacquier A, Thuny F, Jop B, Giorgi R, Cohen F, Gaubert JY, Vidal V, Bartoli JM, Habib G, Moulin G. Measurement of trabeculated left ventricular mass using cardiac magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis of left ventricular non-compaction. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:1098-1104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 323] [Cited by in RCA: 335] [Article Influence: 20.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Stacey RB, Andersen MM, St Clair M, Hundley WG, Thohan V. Comparison of systolic and diastolic criteria for isolated LV noncompaction in CMR. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;6:931-940. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Grothoff M, Pachowsky M, Hoffmann J, Posch M, Klaassen S, Lehmkuhl L, Gutberlet M. Value of cardiovascular MR in diagnosing left ventricular non-compaction cardiomyopathy and in discriminating between other cardiomyopathies. Eur Radiol. 2012;22:2699-2709. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 146] [Cited by in RCA: 144] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Blagova OV, Osipova YV, Nedostup AV, Kogan EA, Sulimov VA. [Clinical, laboratory and instrumental criteria for myocarditis, established in comparison with myocardial biopsy: A non-invasive diagnostic algorithm]. Ter Arkh. 2017;89:30-40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Sattar Y, Hashmi MF. Premature Ventricular Complex. 2025 Feb 16. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Kiliç ME, Arayici ME, Yilancioglu RY, Turan OE, Ozcan EE, Yilmaz MB. Frequent premature ventricular complexes and risk of atrial fibrillation, heart failure, stroke and mortality: a meta-analysis. Heart. 2025;heartjnl-2025. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Corrado D, Anastasakis A, Basso C, Bauce B, Blomström-Lundqvist C, Bucciarelli-Ducci C, Cipriani A, De Asmundis C, Gandjbakhch E, Jiménez-Jáimez J, Kharlap M, McKenna WJ, Monserrat L, Moon J, Pantazis A, Pelliccia A, Perazzolo Marra M, Pillichou K, Schulz-Menger J, Jurcut R, Seferovic P, Sharma S, Tfelt-Hansen J, Thiene G, Wichter T, Wilde A, Zorzi A. Proposed diagnostic criteria for arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy: European Task Force consensus report. Int J Cardiol. 2024;395:131447. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 53.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Valentini F, Anselmi F, Metra M, Cavigli L, Giacomin E, Focardi M, Cameli M, Mondillo S, D'Ascenzi F. Diagnostic and prognostic value of low QRS voltages in cardiomyopathies: old but gold. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2022;29:1177-1187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Zeppenfeld K, Tfelt-Hansen J, de Riva M, Winkel BG, Behr ER, Blom NA, Charron P, Corrado D, Dagres N, de Chillou C, Eckardt L, Friede T, Haugaa KH, Hocini M, Lambiase PD, Marijon E, Merino JL, Peichl P, Priori SG, Reichlin T, Schulz-Menger J, Sticherling C, Tzeis S, Verstrael A, Volterrani M; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2022 ESC Guidelines for the management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death. Eur Heart J. 2022;43:3997-4126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 719] [Cited by in RCA: 1851] [Article Influence: 462.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (11)] |

| 26. | Bennett CE, Freudenberger R. The Current Approach to Diagnosis and Management of Left Ventricular Noncompaction Cardiomyopathy: Review of the Literature. Cardiol Res Pract. 2016;2016:5172308. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Tukker M, Schinkel AFL, Dereci A, Caliskan K. Clinical outcomes of implantable cardioverter-defibrillator therapy in noncompaction cardiomyopathy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart Fail Rev. 2023;28:241-248. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Chimenti C, Lavalle C, Magnocavallo M, Alfarano M, Mariani MV, Bernardini F, Della Rocca DG, Galardo G, Severino P, Di Lullo L, Miraldi F, Fedele F, Frustaci A. A proposed strategy for anticoagulation therapy in noncompaction cardiomyopathy. ESC Heart Fail. 2022;9:241-250. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Stöllberger C, Wegner C, Finsterer J. CHADS2- and CHA2DS2VASc scores and embolic risk in left ventricular hypertrabeculation/noncompaction. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2013;22:709-712. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 30. | Towbin JA, McKenna WJ, Abrams DJ, Ackerman MJ, Calkins H, Darrieux FCC, Daubert JP, de Chillou C, DePasquale EC, Desai MY, Estes NAM 3rd, Hua W, Indik JH, Ingles J, James CA, John RM, Judge DP, Keegan R, Krahn AD, Link MS, Marcus FI, McLeod CJ, Mestroni L, Priori SG, Saffitz JE, Sanatani S, Shimizu W, van Tintelen JP, Wilde AAM, Zareba W. 2019 HRS expert consensus statement on evaluation, risk stratification, and management of arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy. Heart Rhythm. 2019;16:e301-e372. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 652] [Cited by in RCA: 558] [Article Influence: 79.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (6)] |

| 31. | Blagova OV, Pavlenko EV, Varionchik NV, Nedostup AV, Sedov VP, Kogan ЕA, Zaydenov VА, Kupriyanova АG, Donnikov AЕ, Kadochnikova VV, Gagarina NV, Mershina EA, Sinitsyn VЕ, Polyak МЕ, Zaklyazminskaya EV. Myocarditis as a legitimate phenomenon in non-compaction myocardium: Diagnostics, management and influence on outcomes. Russ J Cardiol. 2018;2:44-52. [DOI] [Full Text] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/