Published online Jan 27, 2026. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v18.i1.112954

Revised: September 12, 2025

Accepted: December 2, 2025

Published online: January 27, 2026

Processing time: 159 Days and 24 Hours

Post-colonoscopy colorectal cancer (PCCRC) remains an important issue in en

To explore clinical features of PCCRC and correlation factors.

A retrospective cohort analysis enrolled patients diagnosed with colorectal cancer (CRC) via colonoscopy at West China Hospital, Sichuan University, between January 1, 2022, and December 30, 2024. Demographic data, tumor characteristics, endoscopic findings, and miss records were extracted from electronic medical records and telephone follow-ups. An exploratory analysis was performed to identify causes of missed diagnosis during endoscopy.

Among 5411 colonoscopies in 2047 CRC patients, 66 prior examinations (27 colonoscopies in 17 non-PCCRC patients; 39 colonoscopies in 25 PCCRC patients) failed to establish diagnosis. The overall miss rate was 1.2%, with a PCCRC rate of 0.7%. Compared to the non-PCCRC group, advanced age was significantly associated with PCCRC (P = 0.006). The most common location that occurred PCCRC was sigmoid colon. PCCRC cases had higher rate of prior CRC surgery (41.0%). For endoscopists, PCCRC cases with CRC surgery increased the risk of judgement error. Insertion time demonstrated a positive correlation with missed diagnosis risk, whereas withdrawal time exhibited a negative correlation.

The incidence of PCCRC remains significant. Beyond tumor characteristics, endoscopist proficiency and procedural factors critically impact detection accuracy.

Core Tip: The incidence of post-colonoscopy colorectal cancer (CRC) remains significant. Patients with advanced age or prior CRC surgical history are associated with an elevated risk of post-colonoscopy CRC and may warrant shorter surveillance intervals for follow-up colonoscopy. The proficiency of the endoscopist can also influence the incidence of post-colonoscopy CRC. Enhancing technical proficiency among endoscopists and prolonging withdrawal time during colonoscopy may reduce post-colonoscopy CRC risk.

- Citation: Li Y, Wang CY, Li YX, Wu ZJ, Guo LJ. Clinical features of post-colonoscopy colorectal cancer and real-world multi-scale correlation analysis. World J Gastrointest Surg 2026; 18(1): 112954

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v18/i1/112954.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v18.i1.112954

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common cancer and the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide[1]. Post-colonoscopy CRC (PCCRC) refers to colorectal carcinomas diagnosed within a defined interval after a complete colonoscopy in which no malignancy was detected during the index examination[2]. According to the World Endoscopy Organization criteria, PCCRC encompasses cancers diagnosed 6-36 months post-procedure[3]. This metric has emerged as a crucial quality indicator for colonoscopy, as high-quality examinations should prevent CRC through early detection[4].

Reported PCCRC rates vary across studies, with pooled estimates ranging from 0.7% to 9.0%[5-7]. This heterogeneity reflects disparities in colonoscopy quality, including operator expertise, technological resources, and patient preparation[8]. Notably, PCCRC represents not only a healthcare quality deficit but also correlates with adverse prognoses; studies have demonstrated significantly higher cancer-specific mortality in patients with PCCRC than in their non-PCCRC counterparts[9].

With expanding global CRC screening initiatives, reducing PCCRC incidence has become a critical objective in both clinical practice and public health[8,10]. However, dedicated research remains limited. This retrospective cohort study investigated the clinical characteristics of PCCRC to provide clinicians with diagnostic insights and inform them about procedural optimization.

This retrospective cohort study was conducted at West China Hospital of Sichuan University. The study protocol was approved by the hospital’s Institutional Review Board. Given the retrospective nature of the study, the Institutional Review Board granted a waiver for the requirement of informed consent.

Patients meeting the following criteria were included: (1) Those diagnosed with CRC via endoscopic histopathological biopsy at West China Hospital between January 1, 2022, and December 30, 2024; and (2) Those with documented colonoscopy records within the ten years preceding CRC diagnosis. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Incomplete medical records; and (2) Indeterminate localization of the anorectal lesions. A total of 2047 histologically confirmed CRC cases and 5411 colonoscopies were included and categorized into three cohorts.

A total of 2005 patients (97.9%) with 5345 prior colonoscopies (98.8%) had colorectal neoplasia successfully detected.

Seventeen patients (0.8%) with 27 prior colonoscopies (0.5%) had missed lesions that did not meet the 6- to 36-month interval criterion.

Twenty-five patients (1.2%) with 39 prior colonoscopies (0.7%) had missed lesions that met the 6- to 36-month interval criterion.

Based on criteria established in prior research: (1) PCCRC: A case in which CRC was diagnosed 6-36 months after a colonoscopy that failed to detect colorectal neoplasia; (2) Non-PCCRC: A case in which CRC was diagnosed after a colonoscopy that failed to detect colorectal neoplasia, but the interval between the negative colonoscopy and diagnosis fell outside the 6-36 months window; (3) Confirmed diagnosis: A case with pathologically confirmed CRC with no history of negative colonoscopy results before diagnosis; (4) Overall miss-rate: Calculated as the sum of PCCRC and non-PCCRC cases divided by the total number of eligible patients and expressed as a percentage; (5) PCCRC rate: Calculated as the number of PCCRC cases divided by the total number of eligible patients, expressed as a percentage; (6) High miss-rate endoscopist: An endoscopist who performed > 2000 colonoscopies during the three-year study period and whose PCCRC rate was within the highest quartile; (7) Zero-miss endoscopist: An endoscopist who performed > 2000 colonoscopies during the study period and had zero PCCRC cases; and (8) Low miss-rate endoscopist: An endoscopist who performed > 2000 colonoscopies during the study period but was not classified as either high miss-rate or zero-miss.

All colonoscopy reports and corresponding imaging data were meticulously reviewed to ascertain the reason for the missed lesion and were categorized as follows: (1) Exposure error: Lesions were missed due to inadequate visualization of the colonic mucosa during index colonoscopy; (2) Judgement error: Lesions visible in archived endoscopic images but not recognized or diagnosed as neoplastic lesions during the initial procedure; (3) Biopsy error: Lesions documented, reported, and biopsied during the index colonoscopy with pathology results interpreted as non-neoplastic; and (4) Poor preparation: Visualization hampered by poor bowel preparation quality.

The following data were collected for analysis: (1) Demographics: Age and sex; (2) Endoscopic data: Number of prior colonoscopies and details of index colonoscopies (date, endoscopic diagnosis, and availability of archived high-definition images); (3) Tumor characteristics: Location, histological type, and differentiation grade; and (4) Endoscopist characteristics: Total lifetime colonoscopy volume, number of polyps ≥ 5 mm detected, mean insertion time, mean withdrawal time, and mean number of photographic documentation images per procedure. All data were cross-verified by two independent researchers to ensure completeness and accuracy, thereby minimizing the risk of data entry errors.

Continuous variables were described using the mean (SD), and categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages. For between-group comparisons of continuous variables, the Welch t-test or analysis of variance was used. For between-group comparisons of categorical variables, Fisher’s exact test was employed when the expected frequency was < 5; otherwise, the χ2 test was used. Post-hoc power analysis revealed a statistical power of 100%. For the confirmed diagnosis, non-PCCRC, and PCCRC groups, multinomial logistic regression was performed using PCCRC as the reference group to analyze the associations between various clinical characteristics. For endoscopists categorized as zero-miss, low miss-rate, and high miss-rate, ordinal logistic regression was used to evaluate the factors influencing miss rates. All statistical analyses were conducted using the R software (version 5.4.1).

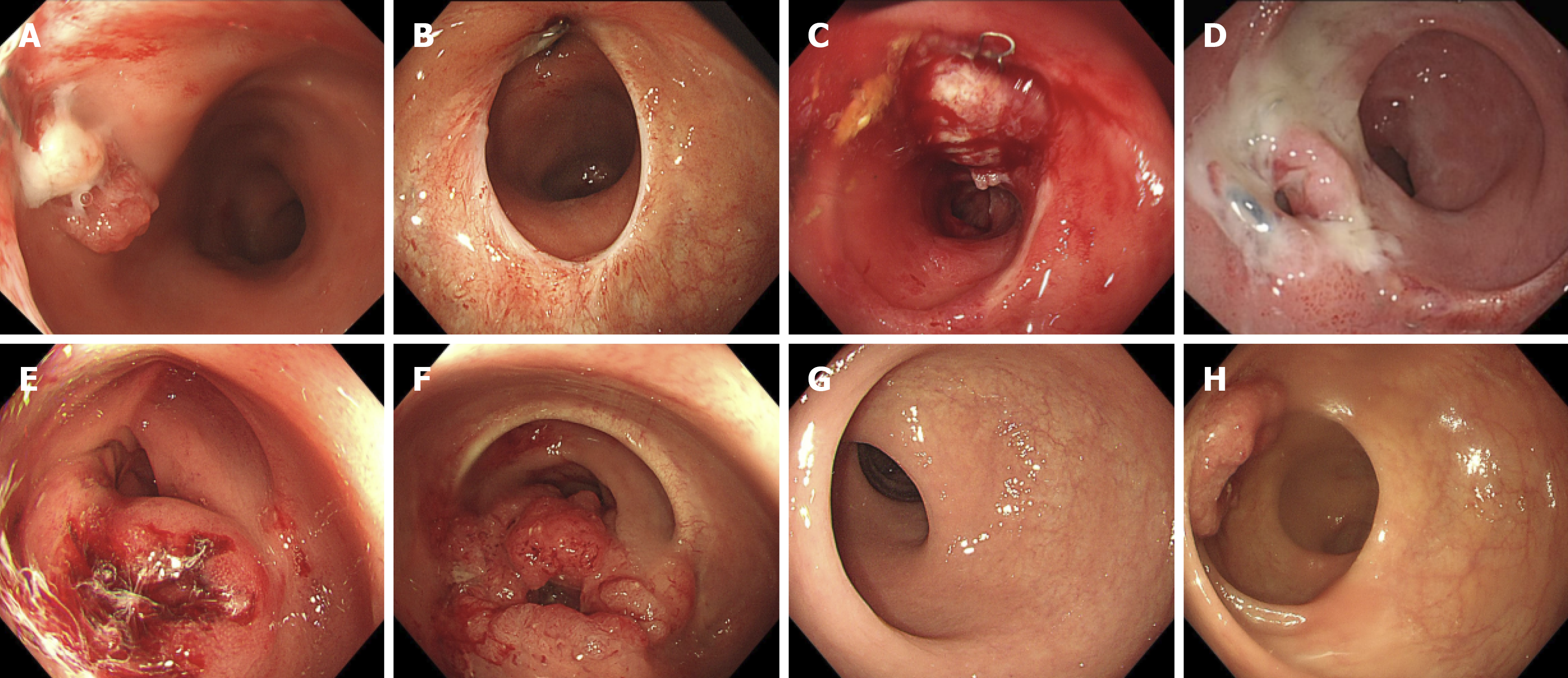

This study included 5411 endoscopies from 2047 patients with pathologically confirmed colorectal tumors stratified into three groups based on missed diagnoses and PCCRC. Age distribution differed significantly among the groups (P = 0.008). The PCCRC group had a significantly higher proportion of patients aged ≥ 60 years (71.79%) compared with the other groups. Tumor location varied: The rectum was the most common site in the missed diagnosis group (58.15%), whereas the sigmoid colon was the most frequently missed location in the PCCRC group. The PCCRC group also had a significantly higher proportion of anastomotic-site tumors (20.51%). The detailed baseline characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Cases of missed CRC are presented in Figure 1.

| Characteristic | Confirmed diagnosis | Non-PCCRC | PCCRC | P value |

| Sex | 0.3551 | |||

| Male | 3306 (61.85) | 20 (74.07) | 26 (66.67) | |

| Female | 2039 (38.15) | 7 (25.93) | 13 (33.33) | |

| Age | 0.0081 | |||

| < 60 | 2523 (47.20) | 18 (66.67) | 11 (28.21) | |

| ≥ 60 | 2822 (52.80) | 9 (33.33) | 28 (71.79) | |

| Location | < 0.0012 | |||

| Ileocecal region | 130 (2.43) | 1 (3.70) | 4 (10.26) | |

| Ascending colon | 314 (5.87) | 1 (3.70) | 3 (7.69) | |

| Hepatic flexure | 125 (2.34) | 1 (3.70) | 0 (0.00) | |

| Transverse colon | 122 (2.28) | 4 (14.81) | 1 (2.56) | |

| Splenic flexure | 21 (0.39) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | |

| Descending colon | 197 (3.69) | 3 (11.11) | 4 (10.26) | |

| Sigmoid colon | 1266 (23.69) | 6 (22.22) | 12 (30.77) | |

| Rectum | 3108 (58.15) | 10 (37.04) | 7 (17.95) | |

| Anastomotic site | 62 (1.16) | 1 (3.70) | 8 (20.51) | |

| Sedation | 0.0461 | |||

| Present | 3019 (56.48) | 18 (66.67) | 29 (74.36) | |

| Absent | 2326 (43.52) | 9 (33.33) | 10 (25.64) | |

| Bowl preparation | 0.0042 | |||

| Excellent | 590 (11.04) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (2.56) | |

| Good | 2118 (39.63) | 14 (51.85) | 15 (38.46) | |

| Inadequate | 927 (17.34) | 11 (40.74) | 9 (23.08) | |

| Poor | 1015 (18.99) | 2 (7.41) | 11 (28.21) | |

| Unclear | 695 (13.00) | 0 (0.00) | 3 (7.69) | |

| Adenoma3 | 0.7741 | |||

| Present | 1264 (65.12) | 15 (60.00) | 12 (70.59) | |

| Absent | 677 (34.88) | 10 (40.00) | 5 (29.41) | |

A total of 16 cases (25.6%) in the PCCRC group had a history of prior CRC surgery. Regarding missed diagnosis causes, “inadequate visualization” ranked highest in both groups (73.91% vs 62.50%, P = 0.260), while “failure to recognize” occurred exclusively in the surgery group (18.75%). A statistically significant difference was observed in tumor location between the groups (P < 0.001), with sigmoid colon lesions predominating in the non-surgery group (47.83%) and anastomotic site involvement being the most common in the surgery group (56.25%). The mean diagnostic delay was significantly longer in patients without surgical history (22 ± 10 months vs 16 ± 8 months, P = 0.039). The detailed PCCRC characteristics are presented in Table 2.

| Characteristic | CRC surgery history | P value | |

| Absent (n = 23) | Present (n = 16) | ||

| Sex | 0.1071 | ||

| Male | 13 (56.52) | 13 (81.25) | |

| Female | 10 (43.48) | 3 (18.75) | |

| Age | 0.7342 | ||

| < 60 | 6 (26.09) | 5 (31.25) | |

| ≥ 60 | 17 (73.91) | 11 (68.75) | |

| Reason | 0.2602 | ||

| Poor preparation | 4 (17.39) | 2 (12.50) | |

| Exposure error | 17 (73.91) | 10 (62.50) | |

| Biopsy error | 2 (8.70) | 1 (6.25) | |

| Judgement error | 0 (0.00) | 3 (18.75) | |

| Location | < 0.0012 | ||

| Ileocecal region | 1 (4.35) | 3 (18.75) | |

| Ascending colon | 3 (13.04) | 0 (0.00) | |

| Transverse colon | 1 (4.35) | 0 (0.00) | |

| Descending colon | 2 (8.70) | 2 (12.50) | |

| Sigmoid colon | 11 (47.83) | 1 (6.25) | |

| Rectum | 5 (21.74) | 1 (6.25) | |

| Anastomotic site | 0 (0.00) | 9 (56.25) | |

| Differentiation | 0.1172 | ||

| Well-differentiated | 1 (4.35) | 4 (25.00) | |

| Moderately differentiated | 15 (65.22) | 6 (37.50) | |

| Poorly differentiated | 7 (30.43) | 6 (37.50) | |

| Missed diagnosis duration (month), mean ± SD | 22 ± 10 | 16 ± 8 | 0.0393 |

Age ≥ 60 years was significantly associated with reduced likelihood of non-PCCRC compared to younger patients [non-PCCRC vs PCCRC, odds ratio (OR) = 0.22, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.08-0.64, P = 0.006]. Lesions at the anastomotic site were associated with decreased odds of confirmed diagnosis (confirmed diagnosis vs PCCRC, OR = 0.07, 95%CI: 0.03-0.18, P < 0.001). Conversely, rectal lesions were associated with increased odds of confirmed diagnosis (confirmed diagnosis vs PCCRC, OR = 3.64, 95%CI: 1.42-9.36, P = 0.007). The detailed analysis results are presented in Table 3.

| Outcome | Characteristic | n | Event n | OR | 95%CI | P value |

| Non-PCCRC | Sex | |||||

| Female | 2059 | 7 | Reference | Reference | - | |

| Male | 3352 | 20 | 1.47 | 0.49-4.47 | 0.493 | |

| Age | ||||||

| < 60 | 2552 | 18 | Reference | Reference | - | |

| ≥ 60 | 2859 | 9 | 0.22 | 0.08-0.64 | 0.006 | |

| Location | ||||||

| Sigmoid colon | 1284 | 6 | Reference | Reference | - | |

| Ileocecal region | 135 | 1 | 0.41 | 0.04-4.67 | 0.471 | |

| Ascending colon | 318 | 1 | 0.61 | 0.05-7.40 | 0.696 | |

| Hepatic flexure | 126 | 1 | 2.97 × 109 | 1.01 × 109, 8.71 × 109 | < 0.001 | |

| Transverse colon | 127 | 4 | 8.50 | 0.75, 96.48 | 0.084 | |

| Splenic flexure | 21 | 0 | 0.01 | 0.01-0.01 | < 0.001 | |

| Descending colon | 204 | 3 | 1.62 | 0.26-9.92 | 0.603 | |

| Rectum | 3125 | 10 | 2.45 | 0.61-9.84 | 0.207 | |

| Anastomotic site | 71 | 1 | 0.31 | 0.03-3.25 | 0.327 | |

| Sedation | ||||||

| Absent | 2345 | 9 | Reference | Reference | - | |

| Present | 3066 | 18 | 0.48 | 0.14-1.59 | 0.229 | |

| Bowl preparation | ||||||

| Good | 2147 | 14 | Reference | Reference | - | |

| Excellent | 591 | 0 | 0.00 | - | - | |

| Inadequate | 947 | 11 | 1.06 | 0.33-3.41 | 0.917 | |

| Poor | 1028 | 2 | 0.21 | 0.04-1.17 | 0.075 | |

| Unclear | 698 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00-0.00 | < 0.001 | |

| Confirmed diagnosis | Sex | |||||

| Female | 2059 | 2039 | Reference | Reference | - | |

| Male | 3352 | 3306 | 0.83 | 0.42-1.65 | 0.598 | |

| Age | ||||||

| < 60 | 2552 | 2523 | Reference | Reference | - | |

| ≥ 60 | 2859 | 2822 | 0.50 | 0.24-1.02 | 0.056 | |

| Location | ||||||

| Sigmoid colon | 1284 | 1266 | Reference | Reference | - | |

| Ileocecal region | 135 | 130 | 0.31 | 0.10-1.01 | 0.052 | |

| Ascending colon | 318 | 314 | 1.10 | 0.30-4.04 | 0.880 | |

| Hepatic flexure | 126 | 125 | 1.95 × 109 | 6.64 × 108, 5.73 × 109 | < 0.001 | |

| Transverse colon | 127 | 122 | 1.34 | 0.17-10.48 | 0.782 | |

| Splenic flexure | 21 | 21 | 1.19 × 109 | 1.19 × 105, 1.19 × 105 | < 0.001 | |

| Descending colon | 204 | 197 | 0.50 | 0.16-1.57 | 0.232 | |

| Rectum | 3125 | 3108 | 3.64 | 1.42-9.36 | 0.007 | |

| Anastomotic site | 71 | 62 | 0.07 | 0.03-0.18 | < 0.001 | |

| Sedation | ||||||

| Absent | 2345 | 2326 | Reference | Reference | - | |

| Present | 3066 | 3019 | 0.64 | 0.29-1.41 | 0.269 | |

| Bowl preparation | ||||||

| Good | 2147 | 2118 | Reference | Reference | - | |

| Excellent | 591 | 590 | 2.12 | 0.26-17.42 | 0.483 | |

| Inadequate | 947 | 927 | 0.63 | 0.27-1.47 | 0.286 | |

| Poor | 1028 | 1015 | 0.74 | 0.32-1.70 | 0.485 | |

| Unclear | 698 | 695 | 1.78 | 0.50-6.40 | 0.374 | |

Factors associated with endoscopist missed diagnosis multivariable regression analysis revealed that an increase in insertion time increases the risk of missed diagnosis (adjusted OR = 0.98, 95%CI: 0.95-1.00, P = 0.045). Increase in withdrawal time reduces the risk of missed diagnosis (adjusted OR = 1.02, 95%CI: 1.01-1.05, P = 0.011). The endoscopist’s mean number of images captured per procedure and polyp detection rate (PDR) (≥ 5 mm) were not significantly associated with their miss rate. The detailed analysis results are presented in Table 4.

| Characteristic | Univariable | Multivariable | ||||||

| n | OR | 95%CI | P value | n | OR | 95%CI | P value | |

| Withdrawal time (second) | 29 | 0.99 | 0.97-1.01 | 0.224 | 29 | 0.98 | 0.95-1.00 | 0.045 |

| Insertion time (second) | 29 | 1.02 | 1.01-1.04 | 0.016 | 29 | 1.02 | 1.01-1.05 | 0.011 |

| Standardized count of detected polyps (> 5 mm) | 29 | 1.00 | 1.00-1.00 | 0.184 | 29 | 1.00 | 1.00-1.00 | 0.640 |

| Picture | 29 | 1.06 | 0.98-1.15 | 0.156 | 29 | 1.01 | 0.90-1.13 | 0.903 |

PCCRC, defined as CRC diagnosed within a specified interval following colonoscopy examination, serves as a direct indicator of colonoscopy quality and effectiveness. Large-scale epidemiological studies have revealed significant geographical variations in PCCRC rates[11]. A Swedish nationwide cohort study (2001-2010) encompassing 16319 patients with CRC reported a PCCRC rate of 7.9%[12]. United Kingdom hospital statistics (2003-2009) indicated a substantially higher proportion of PCCRC (12.1%) among 67202 CRC cases[13]. Conversely, an Australian study (2011-2018) documented a lower PCCRC rate (within 3 years) of 2.16%[14]. In the present study, the PCCRC incidence was 0.7%, comparable to the rates (0.7%-1.7%) reported for high-definition colonoscopy in a Japanese study[6].

The prevalence of PCCRC is high in certain patient populations. Multiple studies have consistently demonstrated an elevated PCCRC risk among older adults, women, and those with a history of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) or diverticular disease[4,5,14]. A United Kingdom multicenter study revealed that 61% of IBD-associated CRCs were classified as PCCRC, a proportion significantly higher than that in the general CRC population[15]. Swedish registry data indicated a markedly increased PCCRC risk in IBD[16]. In this study, compared to the confirmed diagnosis and non-PCCRC groups, the probability of PCCRC occurrence was significantly higher in individuals ≥ 60 years of age. This suggests that shortening the surveillance interval for colonoscopy in patients of advanced age may be warranted.

Tumor location is also a significant influencing factor[9,17]. A meta-analysis revealed a significantly higher incidence of proximal PCCRC (9.7%) than of distal PCCRC (5.4%)[7]. In the present study, missed neoplasia were predominantly located in the sigmoid colon, which might be attributed to limited PCCRC data or racial group differences. Furthermore, a history of prior intestinal surgery is also a significant risk factor for PCCRC, which may be explained by the following reasons: First, altered anatomical structures may impair endoscopic visualization and reduce CRC detection rates. Second, endoscopists may lack adequate knowledge about anastomotic site lesions. An important reason for missed PCCRC in these cases was a judgment error; a review of endoscopic images confirmed that the lesions were photographed but incorrectly identified as benign.

Colonoscopy quality-related factors, such as PDR, may affect PCCRC rates. Multiple studies have reported an inverse correlation between adenoma detection rate or PDR and the risk of PCCRC[8,18-20]. However, in our study, the PDR for polyps ≥ 5 mm did not significantly impact the endoscopist miss rate. This may be because the PCCRC rate was relatively low at our center. Colonoscopy withdrawal time influenced the quality of colonoscopy[21]. In our study, longer insertion time was associated with a higher risk of PCCRC, potentially reflecting lower endoscopist proficiency. Conversely, a longer withdrawal time was associated with a lower PCCRC risk, indicating that an adequate mucosal inspection time effectively reduces PCCRC occurrence. The average number of images captured per procedure showed no significant difference between groups, likely because all exceeded the minimum threshold of 40 images. Although image quality (anatomical coverage and clarity) may hold greater research value than quantity alone, data for such analyses were not available in this study.

The strengths of this study lie in its multidimensional approach, integrating data on patient and tumor characteristics as well as endoscopist-related factors to comprehensively analyze potential contributors to PCCRC. Notably, our findings highlight the significant impact of the complex intestinal environment at anastomotic sites resulting from prior surgery on PCCRC risk. Furthermore, the use of consecutive patient data from a single high-volume center ensures consistency in data quality and management. Moving forward, we plan to conduct prospective, multicenter studies to further validate our conclusions, and will incorporate more comprehensive clinical data such as history of familial adenomatous polyposis and IBD to enhance our research.

This study has some limitations that warrant a cautious interpretation of the results. First, as this was a single-center retrospective study, selection bias may have compromised the reliability of our conclusions. Second, the subjective classification of missed lesions lacks standardized diagnostic criteria or blinded expert reviews, which introduce a potential misclassification bias. Third, the small sample size precluded meaningful subgroup analyses such as assessing the impact of sedation or specific lesion locations on PCCRC.

This study identified key clinical characteristics associated with PCCRC. Enhancing endoscopist training, standardizing examination protocols, and utilizing advanced endoscopic technologies are essential for achieving high-quality examinations.

| 1. | Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75126] [Cited by in RCA: 68846] [Article Influence: 13769.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (202)] |

| 2. | Adler J, Robertson DJ. Interval Colorectal Cancer After Colonoscopy: Exploring Explanations and Solutions. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:1657-64; quiz 1665. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Rutter MD, Beintaris I, Valori R, Chiu HM, Corley DA, Cuatrecasas M, Dekker E, Forsberg A, Gore-Booth J, Haug U, Kaminski MF, Matsuda T, Meijer GA, Morris E, Plumb AA, Rabeneck L, Robertson DJ, Schoen RE, Singh H, Tinmouth J, Young GP, Sanduleanu S. World Endoscopy Organization Consensus Statements on Post-Colonoscopy and Post-Imaging Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology. 2018;155:909-925.e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 152] [Cited by in RCA: 284] [Article Influence: 35.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Burr NE, Derbyshire E, Taylor J, Whalley S, Subramanian V, Finan PJ, Rutter MD, Valori R, Morris EJA. Variation in post-colonoscopy colorectal cancer across colonoscopy providers in English National Health Service: population based cohort study. BMJ. 2019;367:l6090. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 14.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Muñoz García-Borruel M, Hervás Molina AJ, Rodríguez Perálvarez ML, Moreno Rincón E, Pérez Medrano I, Serrano Ruiz FJ, Casáis Juanena LL, Pleguezuelo Navarro M, Naranjo Rodríguez A, Villar Pastor C. Post-colonoscopy colorectal cancer: Characteristics and predictive factors. Med Clin (Barc). 2018;150:1-7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Iwatate M, Kitagawa T, Katayama Y, Tokutomi N, Ban S, Hattori S, Hasuike N, Sano W, Sano Y, Tamano M. Post-colonoscopy colorectal cancer rate in the era of high-definition colonoscopy. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:7609-7617. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kang JH, Evans N, Singh S, Samadder NJ, Lee JK. Systematic review with meta-analysis: the prevalence of post-colonoscopy colorectal cancers using the World Endoscopy Organization nomenclature. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2021;54:1232-1242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Gubbiotti A, Spadaccini M, Badalamenti M, Hassan C, Repici A. Key factors for improving adenoma detection rate. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;16:819-833. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Dossa F, Sutradhar R, Saskin R, Hsieh E, Henry P, Richardson DP, Leake PA, Forbes SS, Paszat LF, Rabeneck L, Baxter NN. Clinical and endoscopist factors associated with post-colonoscopy colorectal cancer in a population-based sample. Colorectal Dis. 2021;23:635-645. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 10. | Rivero-Sánchez L, Grau J, Augé JM, Moreno L, Pozo A, Serradesanferm A, Díaz M, Carballal S, Sánchez A, Moreira L, Balaguer F, Pellisé M, Castells A; PROCOLON group. Colorectal cancer after negative colonoscopy in fecal immunochemical test-positive participants from a colorectal cancer screening program. Endosc Int Open. 2018;6:E1140-E1148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Winter J, Clark G, Steele R, Thornton M. Post-colonoscopy cancer rates in Scotland from 2012 to 2018: A population-based cohort study. Colorectal Dis. 2025;27:e17298. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Forsberg A, Hammar U, Ekbom A, Hultcrantz R. Post-colonoscopy colorectal cancers in Sweden: room for quality improvement. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;29:855-860. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Cheung D, Evison F, Patel P, Trudgill N. Factors associated with colorectal cancer occurrence after colonoscopy that did not diagnose colorectal cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;84:287-295.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Lamba M, Khaing MM, Ma X, Ryan K, Appleyard M, Leggett B, Grimpen F. Post-colonoscopy cancer rate at a tertiary referral hospital in Australia: A data linkage analysis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;38:740-746. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kabir M, Thomas-Gibson S, Ahmad A, Kader R, Al-Hillawi L, Mcguire J, David L, Shah K, Rao R, Vega R, East JE, Faiz OD, Hart AL, Wilson A. Cancer Biology or Ineffective Surveillance? A Multicentre Retrospective Analysis of Colitis-Associated Post-Colonoscopy Colorectal Cancers. J Crohns Colitis. 2024;18:686-694. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Forsberg A, Widman L, Bottai M, Ekbom A, Hultcrantz R. Postcolonoscopy Colorectal Cancer in Sweden From 2003 to 2012: Survival, Tumor Characteristics, and Risk Factors. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18:2724-2733.e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 17. | Baile-Maxía S, Mangas-Sanjuan C, Sala-Miquel N, Barquero C, Belda G, García-Del-Castillo G, García-Herola A, Penalva JC, Picó MD, Poveda MJ, de-Vera F, Zapater P, Jover R. Incidence, characteristics, and predictive factors of post-colonoscopy colorectal cancer. United European Gastroenterol J. 2024;12:309-318. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 18. | Anderson JC, Rex DK, Mackenzie TA, Hisey W, Robinson CM, Butterly LF. Higher Serrated Polyp Detection Rates Are Associated With Lower Risk of Postcolonoscopy Colorectal Cancer: Data From the New Hampshire Colonoscopy Registry. Am J Gastroenterol. 2023;118:1927-1930. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Schwarz S, Hornschuch M, Pox C, Haug U. Polyp detection rate and cumulative incidence of post-colonoscopy colorectal cancer in Germany. Int J Cancer. 2023;152:1547-1555. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Macken E, Van Dongen S, De Brabander I, Francque S, Driessen A, Van Hal G. Post-colonoscopy colorectal cancer in Belgium: characteristics and influencing factors. Endosc Int Open. 2019;7:E717-E727. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Vavricka SR, Sulz MC, Degen L, Rechner R, Manz M, Biedermann L, Beglinger C, Peter S, Safroneeva E, Rogler G, Schoepfer AM. Monitoring colonoscopy withdrawal time significantly improves the adenoma detection rate and the performance of endoscopists. Endoscopy. 2016;48:256-262. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/