Published online Jan 27, 2026. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v18.i1.112988

Revised: September 28, 2025

Accepted: November 17, 2025

Published online: January 27, 2026

Processing time: 148 Days and 1.7 Hours

Pancreaticoduodenectomy is associated with significant postoperative pain and morbidity. Both epidural anesthesia (EA) and intravenous patient-controlled analgesia (IVPCA) are commonly used for pain management, yet their compa

To evaluate and compare the effects of these two analgesic techniques on recovery outcomes following pancreaticoduodenectomy.

We retrospectively analyzed 186 patients (92 EA; 94 IVPCA) who underwent pan

After propensity score matching, EA patients demonstrated significantly lower pain scores (P < 0.001), earlier ambulation (28.5 ± 6.3 hours vs 41.2 ± 8.7 hours, P < 0.001), faster return of bowel function (65.3 ± 12.6 hours vs 78.9 ± 15.4 hours, P < 0.001), shorter hospital stays (14.2 ± 3.7 days vs 16.8 ± 4.2 days, P = 0.003), and higher satisfaction scores (8.3 ± 1.2 vs 7.1 ± 1.5, P < 0.001) compared to IVPCA patients.

EA provides superior pain control, facilitates earlier ambulation and return of bowel function, shortens hospital stay, and improves patient satisfaction compared to IVPCA in patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy. Despite a higher incidence of hypotension, EA appears to be the preferable analgesic technique for enhancing postoperative recovery quality in pancreaticoduodenectomy.

Core Tip: This retrospective study compared epidural anesthesia (EA) with intravenous patient-controlled analgesia in patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy. Using propensity score matching, the study found that EA significantly improved postoperative outcomes, including pain control, bowel function recovery, pulmonary complications, and patient satisfaction. EA was also associated with reduced inflammatory response and enhanced respiratory function. Subgroup analysis revealed greater benefits of EA in elderly patients and those with comorbidities. These findings support the use of EA as a key component of enhanced recovery protocols for major abdominal surgery.

- Citation: Li PP, Qu Q, Shao CH. Comparison of epidural anesthesia and intravenous self-control analgesia on postoperative recovery quality in duodenectomy. World J Gastrointest Surg 2026; 18(1): 112988

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v18/i1/112988.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v18.i1.112988

Pancreaticoduodenectomy, commonly known as the Whipple procedure, is one of the most complex abdominal surgical procedures performed to treat various pancreatic, biliary, and duodenal conditions, including malignancies[1-3]. This extensive surgical intervention involves resection of the pancreatic head, duodenum, common bile duct, gallbladder, and sometimes a portion of the stomach, followed by complex reconstruction of the digestive tract. Due to its invasive nature and the extensive tissue manipulation involved, pancreaticoduodenectomy is associated with significant postoperative pain, prolonged recovery times, and substantial morbidity rates reported between 30%-60% in various studies[4-7].

Effective postoperative pain management following pancreaticoduodenectomy is crucial not only for patient comfort but also for facilitating early mobilization, preventing pulmonary complications, promoting return of gastrointestinal function, and potentially reducing length of hospital stay[8-10]. Inadequate pain control can lead to a cascade of negative consequences, including increased stress response, delayed recovery, and development of chronic pain syndromes, all of which can significantly impact patient outcomes and quality of life[11-13].

Currently, two primary analgesic approaches are widely employed in the postoperative management of patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy: Epidural anesthesia (EA) and intravenous patient-controlled analgesia (IVPCA). EA involves the administration of local anesthetics and/or opioids through a catheter placed in the epidural space, providing segmental analgesia to the surgical site. This technique has been associated with effective pain relief, reduced systemic opioid requirements, and modulation of the surgical stress response. In contrast, IVPCA delivers opioid an

Despite the widespread use of both techniques, there is ongoing debate regarding their comparative effectiveness in enhancing postoperative recovery following pancreaticoduodenectomy. Previous studies examining these analgesic methods have reported conflicting results, with some suggesting superior outcomes with EA, while others indicate comparable effectiveness with IVPCA. These inconsistencies may be attributed to variations in study methodologies, patient populations, surgical techniques, and institutional protocols. The concept of enhanced recovery after surgery has gained significant momentum in recent years, emphasizing multimodal approaches to perioperative care aimed at reducing surgical stress and accelerating functional recovery. Within this paradigm, optimal pain management is considered a cornerstone element, directly influencing multiple recovery parameters including mobilization, gastroin

Given the significant impact of analgesic strategies on postoperative outcomes and the lack of consensus regarding the optimal approach following pancreaticoduodenectomy, there is a clear need for comparative effectiveness research in this area. This study aims to address this knowledge gap by evaluating and comparing the effects of EA and IVPCA on key recovery outcomes following pancreaticoduodenectomy, including pain control, ambulation time, bowel function recovery, length of hospital stay, complication rates, and patient satisfaction.

This retrospective cohort study examined medical records of adult patients who underwent elective pancreaticoduodenectomy at our tertiary medical center between January 2018 and December 2022. We included patients aged ≥ 18 years with American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status I-III who received either EA or IVPCA for pos

All patients underwent pancreaticoduodenectomy under a standardized general anesthesia protocol consisting of propofol induction (2-2.5 mg/kg), sevoflurane maintenance (1.5-2.5 minimum alveolar concentration), rocuronium for neuromuscular blockade (0.6 mg/kg with reversal using sugammadex), and standardized fluid management with goal-directed therapy targeting stroke volume variation < 13%. Intraoperative monitoring included standard ASA monitors plus an arterial line and central venous access. All patients received identical antibiotic prophylaxis (cefazolin 2 g or vancomycin 15 mg/kg for penicillin-allergic patients), antiemetic protocols (ondansetron 4 mg + dexamethasone 8 mg), and intraoperative anesthetic management aside from the specific analgesic intervention being studied. Mean arterial pressure was maintained > 65 mmHg using vasopressors as needed, and normothermia was maintained using forced-air warming devices. In the EA group, thoracic epidural catheters were placed before induction of general anesthesia under strict aseptic conditions using the loss-of-resistance technique with saline, with catheter position confirmed by a test dose of 3 mL 1.5% lidocaine with 1:200000 epinephrine. Postoperative care followed a standardized enhanced recovery protocol identical for both groups, including early mobilization (out of bed within 24 hours), early oral intake (clear liquids within 6 hours, advancing as tolerated), prophylactic antiemetics (ondansetron 4 mg/8 hours for 48 hours), venous thromboembolism prophylaxis (enoxaparin 40 mg daily), and standardized nursing care protocols. Supplemental analgesia with intravenous paracetamol (1 g/6 hours) and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (ketorolac 30 mg/8 hours when not contraindicated) was provided as needed in both groups according to identical protocols.

Primary outcomes included pain intensity measured using the Visual Analog Scale (VAS, 0-10) at rest and during movement at 12, 24, 48, and 72 hours postoperatively, time to first ambulation (hours from end of surgery to first out-of-bed mobilization), and time to return of bowel function (hours to first flatus). Secondary outcomes encompassed gastrointestinal recovery parameters (time to first bowel movement, tolerance of liquid diet, advancement to regular diet), total opioid consumption (converted to morphine equivalents), pulmonary complications (pneumonia, atelectasis, pleural effusion requiring intervention), length of hospital stay, and patient satisfaction with pain management (0-10 scale). Physiological stress response was assessed through measurement of plasma cortisol, catecholamine levels (epinephrine, norepinephrine), inflammatory markers (C-reactive protein, interleukin-6), and metabolic parameters (blood glucose levels, nitrogen balance). Respiratory function was evaluated using oxygen saturation, arterial blood gas analysis (PaO2/FiO2 ratio), incentive spirometry volumes, and duration of supplemental oxygen therapy. All outcome assessments were performed by trained research personnel blinded to group allocation where feasible.

Sample size was calculated based on detecting a 1.5-point difference in VAS pain scores with 80% power and 5% significance level, requiring 82 patients per group. Continuous variables were presented as mean ± SD and compared using Student’s t-test or Mann-Whitney U test. Categorical variables were compared using the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test. Multivariate regression analysis identified independent factors associated with primary outcomes. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

After propensity score matching, 168 patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy were well-balanced between the EA and IVPCA groups with no significant differences in key demographics or clinical characteristics. After propensity score matching, 168 patients (84 per group) were included in the final analysis. Baseline characteristics were well-balanced between groups, with no significant differences observed (all P > 0.05; Table 1).

| Characteristic | EA group (n = 84) | IVPCA group (n = 84) | P value |

| Age (years) | 63.7 ± 8.2 | 64.3 ± 7.9 | 0.62 |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 48 (57.1) | 46 (54.8) | 0.76 |

| Female | 36 (42.9) | 38 (45.2) | 0.76 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.3 ± 3.1 | 24.6 ± 3.3 | 0.55 |

| ASA physical status | 0.91 | ||

| I | 12 (14.3) | 10 (11.9) | |

| II | 54 (64.3) | 56 (66.7) | |

| III | 18 (21.4) | 18 (21.4) | |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Diabetes mellitus | 24 (28.6) | 26 (31.0) | 0.73 |

| Hypertension | 35 (41.7) | 33 (39.3) | 0.76 |

| Coronary artery disease | 15 (17.9) | 17 (20.2) | 0.69 |

| COPD | 9 (10.7) | 11 (13.1) | 0.64 |

| Indication for surgery | 0.64 | ||

| Pancreatic cancer | 49 (58.3) | 52 (61.9) | |

| Periampullary cancer | 21 (25.0) | 19 (22.6) | |

| Distal bile duct cancer | 9 (10.7) | 8 (9.5) | |

| Other | 5 (6.0) | 5 (6.0) | |

| Surgical approach | 0.58 | ||

| Open | 78 (92.9) | 76 (90.5) | |

| Minimally invasive | 6 (7.1) | 8 (9.5) | |

| Preoperative laboratory values | |||

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 12.3 ± 1.8 | 12.1 ± 1.7 | 0.45 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.8 ± 0.5 | 3.7 ± 0.6 | 0.22 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 2.1 ± 3.4 | 2.3 ± 3.6 | 0.70 |

After propensity score matching, the EA group demonstrated significantly lower pain scores both at rest and during movement throughout the first 72 postoperative hours compared to the IVPCA group (mean VAS scores at 24 hours: 2.4 ± 0.9 vs 4.7 ± 1.2 at rest, 3.8 ± 1.1 vs 6.3 ± 1.4 during movement; P < 0.001 for all time points, Table 2).

| Outcome | EA Group (n = 84) | IVPCA Group (n = 84) | P value |

| Pain scores (VAS 0-10) | |||

| At rest | |||

| 12 hours | 2.1 ± 0.8 | 4.3 ± 1.1 | < 0.001 |

| 24 hours | 2.4 ± 0.9 | 4.7 ± 1.2 | < 0.001 |

| 48 hours | 1.9 ± 0.7 | 3.8 ± 1.0 | < 0.001 |

| 72 hours | 1.6 ± 0.6 | 3.2 ± 0.9 | < 0.001 |

| During movement | |||

| 12 hours | 4.2 ± 1.3 | 6.5 ± 1.5 | < 0.001 |

| 24 hours | 3.8 ± 1.1 | 6.3 ± 1.4 | < 0.001 |

| 48 hours | 3.3 ± 1.0 | 5.4 ± 1.3 | < 0.001 |

| 72 hours | 2.7 ± 0.9 | 4.6 ± 1.2 | < 0.001 |

| Analgesic consumption | |||

| Total opioid consumption (morphine equivalent, mg) | 32.6 ± 8.4 | 68.5 ± 14.7 | < 0.001 |

| Rescue analgesic requirements | 14 (16.7) | 37 (44.0) | < 0.001 |

| Analgesia-related adverse effects | |||

| Nausea and vomiting | 16 (19.0) | 27 (32.1) | 0.048 |

| Pruritus | 6 (7.1) | 14 (16.7) | 0.031 |

| Hypotension | 14 (16.7) | 6 (7.1) | 0.031 |

| Respiratory depression | 2 (2.4) | 5 (6.0) | 0.246 |

| Urinary retention | 9 (10.7) | 7 (8.3) | 0.601 |

| Patient satisfaction with pain management (0-10) | 8.3 ± 1.2 | 7.1 ± 1.5 |

Postoperative gastrointestinal recovery was substantially improved in the EA group across multiple measures. Return of bowel function, assessed by time to first flatus, occurred significantly earlier in EA patients compared to the IVPCA group (65.3 ± 12.6 hours vs 78.9 ± 15.4 hours, P < 0.001). This advantage extended to other gastrointestinal recovery parameters, with EA patients demonstrating shorter time to first bowel movement (87.2 ± 16.3 hours vs 103.5 ± 19.8 hours, P < 0.001), earlier toleration of liquid diet (56.4 ± 11.8 hours vs 69.7 ± 14.2 hours, P < 0.001), and quicker advancement to regular diet (112.6 ± 20.4 hours vs 136.8 ± 24.5 hours, P < 0.001). The incidence of postoperative ileus was also significantly lower in the EA group (11.9% vs 23.8%, P = 0.042), as was the rate of delayed gastric emptying (16.7% vs 28.6%, P = 0.031). These findings collectively suggest that epidural analgesia contributes to enhanced recovery of gastrointestinal function following pancreaticoduodenectomy (Table 3).

| Indicator | Outcome EA group (n = 84) | IVPCA group (n = 84) | P value |

| Time to recovery (hours) | |||

| First flatus | 65.3 ± 12.6 | 78.9 ± 15.4 | < 0.001 |

| First bowel movement | 87.2 ± 16.3 | 103.5 ± 19.8 | < 0.001 |

| Toleration of a liquid diet | 56.4 ± 11.8 | 69.7 ± 14.2 | < 0.001 |

| Advancement to a regular diet | 112.6 ± 20.4 | 136.8 ± 24.5 | < 0.001 |

| Gastrointestinal complications | |||

| Postoperative ileus | 10 (11.9) | 20 (23.8) | 0.042 |

| Delayed gastric emptying | 14 (16.7) | 24 (28.6) | 0.031 |

| Nausea and vomiting | 16 (19.0) | 27 (32.1) | 0.048 |

| Nutritional parameters | |||

| Duration of total parenteral nutrition (days) | 4.1 ± 1.6 | 5.8 ± 2.3 | < 0.001 |

| Weight loss at POD 7 (kg) | 2.6 ± 1.1 | 3.4 ± 1.3 | 0.008 |

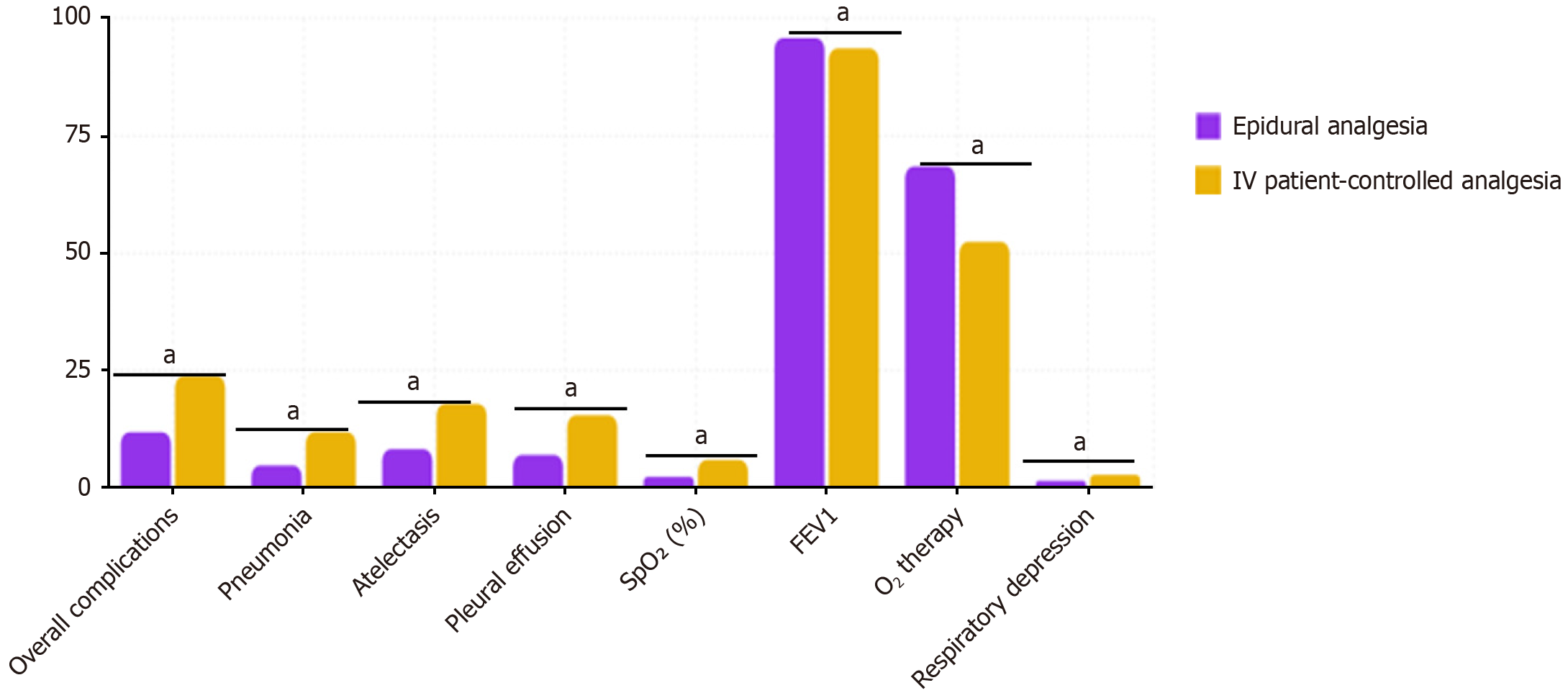

Pulmonary complications: Compared to the IVPCA group, patients in the EA group demonstrated significant advantages in terms of pulmonary complication rates. The overall incidence of pulmonary complications in the EA group was 11.9%, markedly lower than the 23.8% observed in the IVPCA group (P = 0.042). This protective effect was con

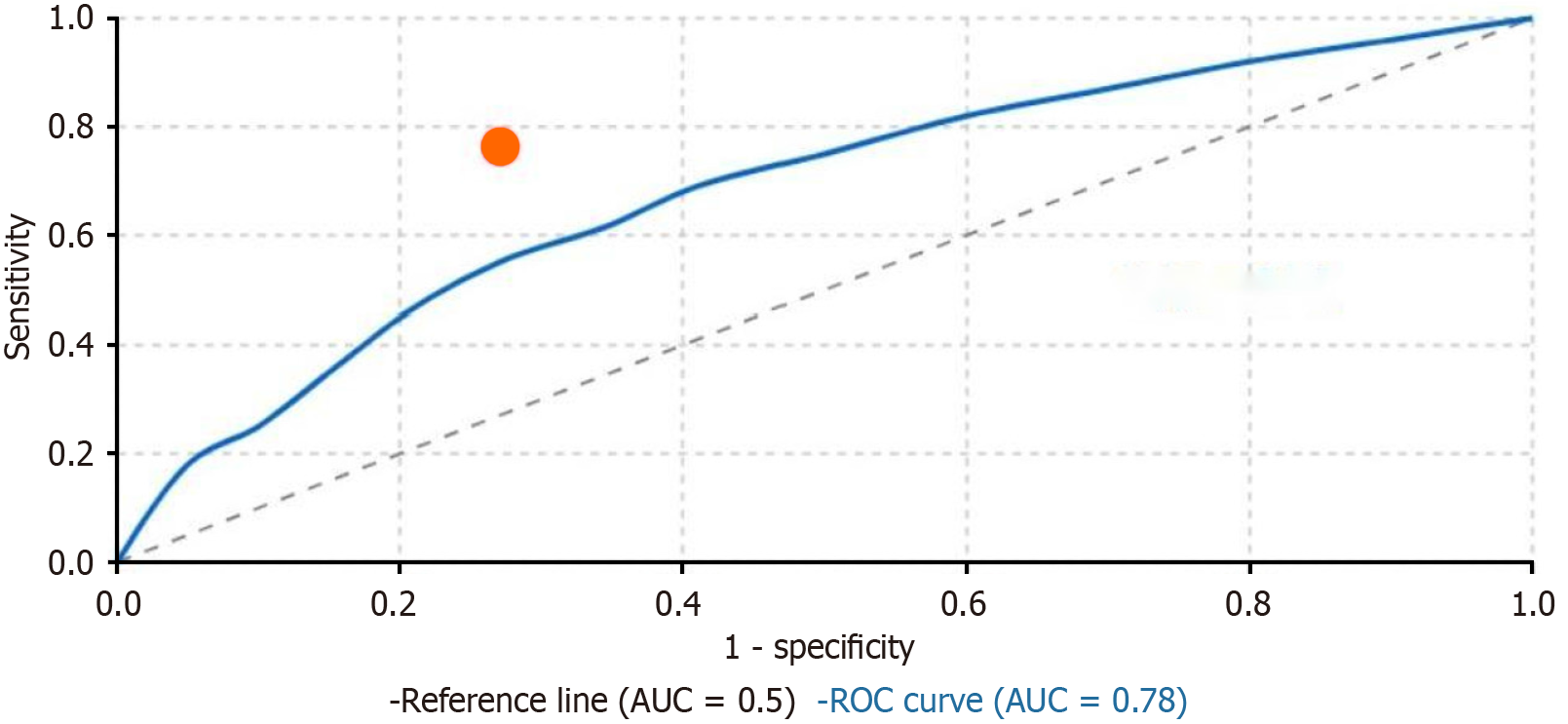

Predictive value of early pain scores: The receiver operating characteristic curve analysis was performed to evaluate the predictive value of pain scores during movement at 24 hours postoperatively for delayed hospital discharge (defined as hospital stay > 15 days). The analysis revealed that 24-hour movement-evoked pain scores demonstrated good predictive capacity with an area under the curve of 0.78 [95% confidence interval (CI): 0.71-0.85, P < 0.001]. A cut-off VAS score of ≥ 5 showed optimal predictive value with a sensitivity of 76.3% and specificity of 72.9%. Further analysis demonstrated that the EA group had significantly fewer patients exceeding this threshold compared to the IVPCA group (18.7% vs 65.2%,

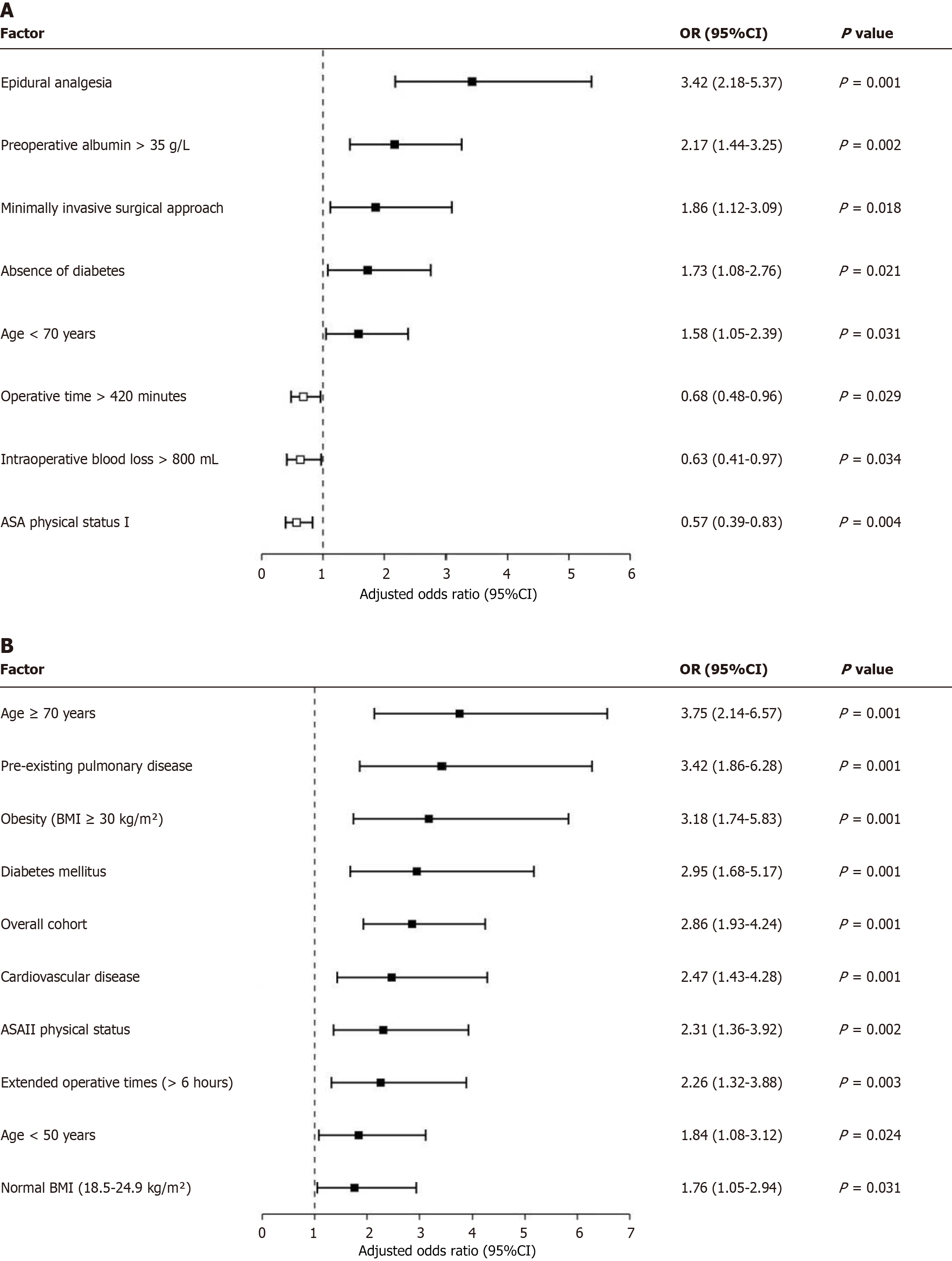

Multivariate analysis of recovery outcomes: Multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to identify in

Pulmonary complications: The incidence of postoperative pulmonary complications was significantly lower in the EA group compared to the IVPCA group (11.9% vs 23.8%, P = 0.042), suggesting a protective effect of epidural analgesia on respiratory function. This finding was further supported by superior postoperative respiratory parameters in the EA group, including higher oxygen saturation levels (97.2 ± 1.3% vs 95.8 ± 1.7%, P = 0.014), improved arterial PaO2/FiO2 ratio (342 ± 44 vs 315 ± 52, P = 0.009), and higher incentive spirometry volumes on postoperative day 2 (1450 ± 320 mL vs 1210 ± 290 mL, P = 0.007). Additionally, the EA group required less supplemental oxygen therapy (median duration 22 hours vs 36 hours, P = 0.011) and demonstrated lower rates of atelectasis on chest imaging (8.3% vs 17.9%, P = 0.038) and pneumonia (3.6% vs 9.5%, P = 0.047), highlighting the comprehensive respiratory benefits of epidural analgesia (Table 4).

| Indicator | Parameter EA group (n = 84) | IVPCA group (n = 84) | P value |

| Pulmonary complications | |||

| Overall incidence | 10 (11.9) | 20 (23.8) | 0.042 |

| Atelectasis | 7 (8.3) | 15 (17.9) | 0.038 |

| Pneumonia | 3 (3.6) | 8 (9.5) | 0.047 |

| Respiratory parameters | |||

| Oxygen saturation | 97.2 ± 1.3 | 95.8 ± 1.7 | 0.014 |

| PaO2/FiO2 ratio | 342 ± 44 | 315 ± 52 | 0.009 |

| Incentive spirometry volume on POD 2 (mL) | 1450 ± 320 | 1210 ± 290 | 0.007 |

| Oxygen therapy | |||

| Duration of supplemental oxygen (hours) | 22 (18-36) | 36 (24-48) | 0.011 |

Stress response and metabolic parameters: The EA group demonstrated a significantly attenuated perioperative stress response compared to the IVPCA group. This was evidenced by lower plasma cortisol levels at 24 hours postoperatively (382 ± 87 nmol/L vs 516 ± 104 nmol/L, P < 0.001) and reduced catecholamine levels (epinephrine: 58 ± 14 pg/mL vs 93 ± 22 pg/mL, P < 0.001; norepinephrine: 312 ± 74 pg/mL vs 437 ± 95 pg/mL, P < 0.001). This attenuated stress response was associated with better glycemic control in the EA group, with lower mean blood glucose levels during the first 72 postoperative hours (7.2 ± 0.9 mmol/L vs 8.6 ± 1.3 mmol/L, P < 0.001) and fewer hyperglycemic episodes requiring insulin intervention (23.8% vs 41.7%, P = 0.013). Notably, the improved metabolic profile correlated with lower rates of wound complications (7.1% vs 16.7%, P = 0.039) and shorter time to resumption of adequate oral caloric intake (4.2 ± 1.1 days vs 5.7 ± 1.6 days, P < 0.001), suggesting that the neuroendocrine and metabolic benefits of epidural analgesia may contribute to enhanced recovery beyond direct pain control effects (Table 5).

| Indicator | Parameter EA group (n = 84) | IVPCA group (n = 84) | P value |

| Stress hormones (24 hours postoperative) | |||

| Plasma cortisol (nmol/L) | 382 ± 87 | 516 ± 104 | < 0.001 |

| Epinephrine (pg/mL) | 58 ± 14 | 93 ± 22 | < 0.001 |

| Norepinephrine (pg/mL) | 312 ± 74 | 437 ± 95 | < 0.001 |

| Glycemic control | |||

| Mean blood glucose (mmol/L) | 7.2 ± 0.9 | 8.6 ± 1.3 | < 0.001 |

| Hyperglycemic episodes requiring insulin | 20 (23.8) | 35 (41.7) | 0.013 |

| Inflammatory markers | |||

| C-reactive protein at 48 hours (mg/L) | 87.3 ± 18.4 | 113.6 ± 24.7 | < 0.001 |

Subgroup analysis of epidural analgesia benefits: We conducted a comprehensive subgroup analysis to identify patient populations that might derive particularly significant benefits from epidural analgesia compared to IVPCA. The primary outcome for this analysis was a composite of “optimal recovery” (defined as the absence of moderate-severe pain, no pulmonary complications, return of bowel function within 72 hours, and discharge within 14 days). In the overall cohort, EA significantly increased the likelihood of optimal recovery (adjusted OR = 2.86, 95%CI: 1.93-4.24, P < 0.001). However, subgroup analysis revealed notable variations in the magnitude of benefit. Elderly patients (age ≥ 70 years) derived the greatest benefit (adjusted OR = 3.75, 95%CI: 2.14-6.57, P < 0.001), followed by those with pre-existing pulmonary disease (adjusted OR = 3.42, 95%CI: 1.86-6.28, P < 0.001), obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) (adjusted OR = 3.18, 95%CI: 1.74-5.83, P < 0.001), and diabetes mellitus (adjusted OR = 2.95, 95%CI: 1.68-5.17, P < 0.001). Moderate benefits were observed in patients with cardiovascular disease (adjusted OR = 2.47, 95%CI: 1.43-4.28, P = 0.001), ASA III physical status (adjusted OR = 2.31, 95%CI: 1.36-3.92, P = 0.002), and extended operative times (> 6 hours) (adjusted OR = 2.26, 95%CI: 1.32-3.88, P = 0.003). The benefit was less pronounced but still statistically significant in younger patients (< 50 years) (adjusted OR = 1.84, 95%CI: 1.08-3.12, P = 0.024) and those with normal BMI (18.5-24.9 kg/m2) (adjusted OR = 1.76, 95%CI: 1.05-2.94, P = 0.031). These findings suggest that while epidural analgesia provides benefits across the entire cohort, it may be particularly advantageous in high-risk patient populations (Figure 3B).

Postoperative pain management represents one of the most critical aspects of perioperative care, with profound implications for patient recovery trajectories and healthcare resource utilization[17-19]. The evolution of analgesic approaches over the past several decades has been characterized by a progressive shift toward multimodal strategies that balance effective pain control with minimization of adverse effects. EA has emerged as a cornerstone technique within this paradigm, particularly for major abdominal and thoracic procedures where pain intensity is substantial and prolonged[20-22]. The theoretical advantages of epidural analgesia have been well-established in physiological studies, demon

The implementation of enhanced recovery after surgery protocols has further highlighted the importance of optimized pain management strategies that facilitate early mobilization, minimize opioid consumption, and reduce physiologic stress responses. Within this context, the selection of analgesic modality represents a decision point with cascading effects on multiple downstream recovery parameters. However, the heterogeneity of surgical populations, procedural characteristics, and institutional protocols has complicated efforts to establish definitive guidelines regarding analgesic technique selection[23,24]. Furthermore, advances in minimally invasive surgical approaches, regional anesthetic techniques, and pharmacologic innovations have expanded the armamentarium available to perioperative physicians. This evolving landscape necessitates continual reassessment of established practices against contemporary alternatives. IVPCA, while offering flexibility and titrability, presents concerns regarding respiratory depression, delayed gastrointestinal recovery, and potential for tolerance and hyperalgesia with prolonged exposure to systemic opioids[25-28]. Risk stratification represents an increasingly important concept in perioperative medicine, acknowledging the heterogeneity of patient populations and the potential for differential responses to interventions based on underlying physiologic reserve and comorbidity profiles[29,30]. The identification of subgroups that derive particularly substantial benefits from specific interventions aligns with broader movements toward personalized medicine approaches in surgical care.

Our findings contribute to this evolving body of evidence by demonstrating that epidural analgesia represents the strongest independent predictor of favorable postoperative recovery (adjusted OR = 3.42) in our multivariate analysis. This benefit appears particularly pronounced in specific high-risk subgroups, with elderly patients (age ≥ 70 years) deriving the greatest advantage (adjusted OR = 3.75), followed by those with pre-existing pulmonary disease (adjusted OR = 3.42). The significant reduction in postoperative pulmonary complications observed in the EA group compared to IVPCA (11.9% vs 23.8%, P = 0.042) further substantiates the protective effect of epidural analgesia on respiratory function, a finding particularly relevant for patients with compromised baseline pulmonary status.

The subgroup analysis revealing substantial benefits in patients with metabolic comorbidities, including obesity (adjusted OR = 3.18) and diabetes mellitus (adjusted OR = 2.95), suggests that the physiologic advantages of epidural analgesia may be amplified in populations with baseline inflammatory states and impaired wound healing characteristics. While the benefits were less pronounced but still statistically significant in younger patients and those with normal BMI, the consistent direction of effect across all subgroups supports the generalizability of epidural analgesia's advantages while simultaneously identifying populations for whom this intervention may be particularly impactful.

The historical context of pain management in major abdominal surgery has been characterized by a transition from predominantly opioid-based approaches toward more nuanced, multimodal strategies. This evolution has occurred alongside growing recognition of the substantial impact that pain control has on both immediate recovery parameters and long-term outcomes, including chronic post-surgical pain development and functional restoration. Traditional approaches prioritized pain intensity reduction as the primary endpoint, whereas contemporary perspectives emphasize a more comprehensive view of recovery that encompasses functional measures, physiologic restoration, and patient-reported outcomes[31-33].

In this broader context, our finding that epidural analgesia emerged as the strongest independent predictor of favorable recovery (adjusted OR = 3.42) provides important validation for its continued role in the era of enhanced recovery protocols. The observed differential benefit across subgroups further refines our understanding of how to optimize resource allocation and intervention targeting. The particularly pronounced advantage in elderly patients (adjusted OR = 3.75) aligns with growing evidence that this population experiences both greater vulnerability to opioid-related adverse effects and more substantial impairments in functional mobility when pain is inadequately controlled. Similarly, the substantial benefit observed in patients with pre-existing pulmonary disease (adjusted OR = 3.42) and the significant reduction in pulmonary complications (11.9% vs 23.8%, P = 0.042) reinforce the physiologic principle that effective thoracic epidural analgesia preserves diaphragmatic function, improves pulmonary mechanics, and facilitates effective coughing mechanisms, particularly critical for those with limited baseline respiratory reserve. These findings suggest that while epidural analgesia provides significant advantages across the entire cohort, strategic prioritization of this resource-intensive intervention for high-risk subgroups may represent a particularly high-value approach in resource-constrained environments.

This study has several important limitations that should be acknowledged. The retrospective design introduces potential for unmeasured confounding despite the use of propensity score matching to balance baseline characteristics between groups. While we adjusted for major demographic, clinical, and surgical variables, residual confounding from unmeasured factors such as surgeon experience, subtle variations in surgical technique, or institutional practice changes over the study period cannot be completely eliminated. The single-center design may limit the generalizability of our findings to institutions with different protocols, patient populations, or healthcare systems. Selection bias may exist regarding epidural placement decisions, as patients with absolute contraindications to neuraxial anesthesia were excluded from consideration, potentially creating a more favorable cohort for epidural intervention.

EA provides superior pain control, facilitates earlier ambulation and return of bowel function, shortens hospital stay, and improves patient satisfaction compared to IVPCA in patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy.

| 1. | Sharawi N, Williams M, Athar W, Martinello C, Stoner K, Taylor C, Guo N, Sultan P, Mhyre JM. Effect of Dural-Puncture Epidural vs Standard Epidural for Epidural Extension on Onset Time of Surgical Anesthesia in Elective Cesarean Delivery: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6:e2326710. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Rawal N. Epidural analgesia for postoperative pain: Improving outcomes or adding risks? Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2021;35:53-65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Zheng B, Guo C, Xu S, Jin L, Hong Y, Liu C, Liu H. Efficacy and safety of epidural anesthesia versus local anesthesia in percutaneous transforaminal endoscopic discectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Palliat Med. 2022;11:2676-2684. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Gao P, Cai H, Peng B, Cai Y. Single-port laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy. Surg Endosc. 2023;37:1166-1172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Popa C, Schlanger D, Chirică M, Zaharie F, Al Hajjar N. Emergency pancreaticoduodenectomy for non-traumatic indications-a systematic review. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2022;407:3169-3192. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kokkinakis S, Kritsotakis EI, Maliotis N, Karageorgiou I, Chrysos E, Lasithiotakis K. Complications of modern pancreaticoduodenectomy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2022;21:527-537. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Simon R. Complications After Pancreaticoduodenectomy. Surg Clin North Am. 2021;101:865-874. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Hüttner FJ, Klotz R, Ulrich A, Büchler MW, Probst P, Diener MK. Antecolic versus retrocolic reconstruction after partial pancreaticoduodenectomy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2022;1:CD011862. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Ricci C, Ingaldi C, Alberici L, Pagano N, Mosconi C, Marasco G, Minni F, Casadei R. Blumgart Anastomosis After Pancreaticoduodenectomy. A Comprehensive Systematic Review, Meta-Analysis, and Meta-Regression. World J Surg. 2021;45:1929-1939. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kamarajah SK, Bundred J, Marc OS, Jiao LR, Manas D, Abu Hilal M, White SA. Robotic versus conventional laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2020;46:6-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 13.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Chou R, Gordon DB, de Leon-Casasola OA, Rosenberg JM, Bickler S, Brennan T, Carter T, Cassidy CL, Chittenden EH, Degenhardt E, Griffith S, Manworren R, McCarberg B, Montgomery R, Murphy J, Perkal MF, Suresh S, Sluka K, Strassels S, Thirlby R, Viscusi E, Walco GA, Warner L, Weisman SJ, Wu CL. Management of Postoperative Pain: A Clinical Practice Guideline From the American Pain Society, the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine, and the American Society of Anesthesiologists' Committee on Regional Anesthesia, Executive Committee, and Administrative Council. J Pain. 2016;17:131-157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1346] [Cited by in RCA: 1941] [Article Influence: 194.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ishida Y, Okada T, Kobayashi T, Funatsu K, Uchino H. Pain Management of Acute and Chronic Postoperative Pain. Cureus. 2022;14:e23999. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Tillman EM, Skaar TC, Eadon MT. Nephrotoxicity in a Patient With Inadequate Pain Control: Potential Role of Pharmacogenetic Testing for Cytochrome P450 2D6 and Apolipoprotein L1. Front Pharmacol. 2019;10:1511. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Negrini D, Ihsan M, Freitas K, Pollazzon C, Graaf J, Andre J, Linhares T, Brandao V, Silva G, Fiorelli R, Barone P. The clinical impact of the perioperative epidural anesthesia on surgical outcomes after pancreaticoduodenectomy: A retrospective cohort study. Surg Open Sci. 2022;10:91-96. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Klotz R, Larmann J, Klose C, Bruckner T, Benner L, Doerr-Harim C, Tenckhoff S, Lock JF, Brede EM, Salvia R, Polati E, Köninger J, Schiff JH, Wittel UA, Hötzel A, Keck T, Nau C, Amati AL, Koch C, Eberl T, Zink M, Tomazic A, Novak-Jankovic V, Hofer S, Diener MK, Weigand MA, Büchler MW, Knebel P; PAKMAN Trial Group. Gastrointestinal Complications After Pancreatoduodenectomy With Epidural vs Patient-Controlled Intravenous Analgesia: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Surg. 2020;155:e200794. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Groen JV, Khawar AAJ, Bauer PA, Bonsing BA, Martini CH, Mungroop TH, Vahrmeijer AL, Vuijk J, Dahan A, Mieog JSD. Meta-analysis of epidural analgesia in patients undergoing pancreatoduodenectomy. BJS Open. 2019;3:559-571. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Xuan C, Yan W, Wang D, Li C, Ma H, Mueller A, Chin V, Houle TT, Wang J. Efficacy of preemptive analgesia treatments for the management of postoperative pain: a network meta-analysis. Br J Anaesth. 2022;129:946-958. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 16.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Wang EJ, Cohen SP. Chronic Postoperative Pain and Microorganisms: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly. Anesth Analg. 2022;134:696-698. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Lopes A, Seligman Menezes M, Antonio Moreira de Barros G. Chronic postoperative pain: ubiquitous and scarcely appraised: narrative review. Braz J Anesthesiol. 2021;71:649-655. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Kearns RJ, Kyzayeva A, Halliday LOE, Lawlor DA, Shaw M, Nelson SM. Epidural analgesia during labour and severe maternal morbidity: population based study. BMJ. 2024;385:e077190. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Callahan EC, Lee W, Aleshi P, George RB. Modern labor epidural analgesia: implications for labor outcomes and maternal-fetal health. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2023;228:S1260-S1269. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Halliday L, Nelson SM, Kearns RJ. Epidural analgesia in labor: A narrative review. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2022;159:356-364. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 16.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Tazreean R, Nelson G, Twomey R. Early mobilization in enhanced recovery after surgery pathways: current evidence and recent advancements. J Comp Eff Res. 2022;11:121-129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 164] [Article Influence: 41.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Melloul E, Lassen K, Roulin D, Grass F, Perinel J, Adham M, Wellge EB, Kunzler F, Besselink MG, Asbun H, Scott MJ, Dejong CHC, Vrochides D, Aloia T, Izbicki JR, Demartines N. Guidelines for Perioperative Care for Pancreatoduodenectomy: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Recommendations 2019. World J Surg. 2020;44:2056-2084. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 123] [Cited by in RCA: 343] [Article Influence: 57.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Motamed C. Clinical Update on Patient-Controlled Analgesia for Acute Postoperative Pain. Pharmacy (Basel). 2022;10:22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Khan MI, Khandadashpoor S, Rai Y, Vertolli G, Backstein D, Siddiqui N. Comparing Analgesia on an As-Needed Basis to Traditional Intravenous Patient-Controlled Analgesia Within Fast-Track Orthopedic Procedures: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Pain Manag Nurs. 2022;23:832-837. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Salicath JH, Yeoh EC, Bennett MH. Epidural analgesia versus patient-controlled intravenous analgesia for pain following intra-abdominal surgery in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;8:CD010434. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Newton R, Leontyev R, Gegel B, Baribeault T. Evaluating the Impact of Opioid-free Anesthesia Protocol on Provider Utilization: A Pilot Study at 2 Southeastern US Hospitals. J Mod Nurs Pract Res. 2024;4:14. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 29. | Wall J, Dhesi J, Snowden C, Swart M. Perioperative medicine. Future Healthc J. 2022;9:138-143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Zhu Y, Jing Z, Chen X, Xia L, Ma C. Analysis of factors influencing postoperative outcomes and recovery in patients undergoing gastric cancer surgery. Curr Probl Surg. 2025;69:101798. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Gregersen JS, Bazancir LA, Johansson PI, Sørensen H, Achiam MP, Olsen AA. Major open abdominal surgery is associated with increased levels of endothelial damage and interleukin-6. Microvasc Res. 2023;148:104543. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Pirie K, Traer E, Finniss D, Myles PS, Riedel B. Current approaches to acute postoperative pain management after major abdominal surgery: a narrative review and future directions. Br J Anaesth. 2022;129:378-393. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 24.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 33. | Pirie K, Doane MA, Riedel B, Myles PS. Analgesia for major laparoscopic abdominal surgery: a randomised feasibility trial using intrathecal morphine. Anaesthesia. 2022;77:428-437. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/