Published online Jan 27, 2026. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v18.i1.113040

Revised: October 2, 2025

Accepted: November 25, 2025

Published online: January 27, 2026

Processing time: 156 Days and 6.6 Hours

Colorectal cancer (CRC) in older adults presents unique management challenges due to age-related physiological changes and comorbidities. However, this demo

To characterise the perioperative features and outcomes of older CRC patients undergoing surgery at a tertiary hospital in Malaysia.

A cross-sectional study was conducted using patient records of older individuals (≥ 65 years old) diagnosed with CRC and who underwent surgery at USM Spe

The study included 98 participants (57.1% males, 82.7% Malay), with the majority aged 65-69 years (44.9%). BMI indicated a significant association with age group (P = 0.023), with obesity more prevalent among individuals aged 70-74 years and 75-79 years. Type of operation (P = 0.046) and PN stage (P = 0.027) were also significantly associated with age group. Adjuvant treatment demonstrated a significant association with recurrence and follow-up (P = 0.006). Multivariate analysis revealed that BMI, ischaemic heart disease, and M stage were statistically significant predictors of patient survival after follow-up. Overweight patients were 11.22 times more likely to survive than those who were underweight [adjusted odds ratio (aOR) = 11.22, P = 0.016], whereas patients with ischaemic heart disease (aOR = 0.07, P = 0.027) or M1 stage disease (aOR = 0.24, P = 0.014) had significantly lower survival odds.

BMI, ischaemic heart disease, and metastatic status are critical determinants of survival, highlighting the importance of comprehensive preoperative assessment and individualised management strategies in this vulnerable population. Further larger-scale, longitudinal studies are needed to improve outcomes among older adults with CRC.

Core Tip: This study assessed perioperative outcomes and prognostic factors in 98 older patients with colorectal cancer (CRC; ≥ 65 years) who underwent surgery at a Malaysian tertiary hospital. Body mass index, ischaemic heart disease, and metastatic status (M stage) were identified as significant predictors of survival. Overweight patients showed better survival outcomes, whereas those with ischaemic heart disease or metastasis had poorer outcomes. Our study provides valuable regional insights into perioperative characteristics and prognostic factors in older CRC patients. These findings highlight the importance of comprehensive preoperative assessment and individualised management strategies, as well as the need for larger-scale, longitudinal studies to optimise care and improve outcomes in this vulnerable population.

- Citation: Sultan A, Zakaria Z, Riaz S, Goni MD, Zakaria AD. Perioperative characteristics and outcomes of colorectal cancer in elderly patients. World J Gastrointest Surg 2026; 18(1): 113040

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v18/i1/113040.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v18.i1.113040

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is characterised by unregulated cell growth originating in the colon, encompassing the ascending, transverse, descending, and sigmoid colon, as well as rectum[1]. The most common clinical manifestation of CRC is haematochezia, especially in patients with tumours in the recto-sigmoidal region. Patients commonly present with altered bowel habits, rectal bleeding, and abdominal discomfort. Other signs and symptoms include fever, anaemia, weight loss, and the presence of an abdominal mass[2].

CRC is classified as a "lifestyle or behavioural" disease, linked to factors such as unhealthy dietary practices rich in calories and animal fat, alcohol intake, smoking, Helicobacter pylori infection, obesity, and physical inactivity[3,4]. Its pathogenesis is multifactorial. The epithelial cells of the colorectal mucosa may develop hyperplasia, atypical hyperplasia (mild, moderate, severe), and adenomatous changes, which can eventually progress to carcinoma[5].

CRC ranks as the third most common malignancy globally and is the second leading cause of cancer-related mortality, with 916000 fatalities recorded in 2020[6,7]. Its incidence differs across geographical regions, being most common in North America, Western Europe, and Oceania, while exhibiting lower prevalence rates in Africa, Asia, and South America[8]. Compared to other Asian countries such as Japan, South Korea, and Singapore, the incidence rate of CRC is lower in Malaysia[9]. Currently, a noticeable upward trend in the incidence and mortality of CRC is observed in Asian countries, including Malaysia[10]. This trend may be attributed to increased screening initiatives, diminished prevalence of risk factors, and/or enhanced treatment options in these nations.

In Malaysia, CRC is the second most prevalent cancer, accounting for 13.5% of all newly diagnosed cancer cases from 2012 to 2016[11]. In 2020, Lim et al[12] reported that more than half of the CRC patients recorded rectal tumours (51.8%) compared to colonic tumours (43.3%). The risk of CRC increases with age, with over 80% of CRC cases in Malaysia being diagnosed in individuals aged over 50. The age-standardised incidence rate was 14.8 per 100000 for men, compared to 11.1 per 100000 for women. However, several studies reported no significance difference between sexes in Malaysia[13]. CRC incidence also varies by ethnicity, being highest among the Chinese community, followed by Malay and Indian populations[11].

The prognosis for CRC is significantly influenced by the stage at diagnosis, with 5-year survival rates of 90% and 80% for stages 1 and 2, 30%-60% for stage 3, and approximately 5%-10% for stage 4[14]. Malaysia, classified as a higher-middle-income nation, reported an overall 5-year survival rate of 46.5% between 1997 and 2000[12]. The five-year survival rate for CRC patients in Malaysia ranges from 34% to 60%. A specific cohort in Kuala Lumpur recorded a 5-year survival rate of 60.5%, whereas a study from Kelantan indicated a rate of 34.3%[15,16]. These variations are likely attributable to differences in the demographic and clinical profiles of CRC patients at diagnosis, as well as disparities in access to early diagnostic procedures and treatment across different clinical settings.

A large percentage of CRC cases in Malaysia are reported in the late stage in the elderly population, resulting in a poor prognosis and significantly elevating the healthcare burden due to increased treatment costs and reduced quality of life in later stages[16]. Currently, Malaysia, despite its multiethnic population, lacks a formalised national CRC screening program. The rising socioeconomic status and adoption of a more westernised lifestyle in developing Asian countries, such as Malaysia, may be correlated with a rising incidence of CRC. The country is experiencing population ageing, accompanied by rising affluence and a heightened prevalence of CRC risk factors, including a westernised diet, obesity, and smoking[17].

Surgical resection currently offers the most promising chance of cure for patients with CRC[18]. The proportion of elderly patients requiring surgery for CRC is increasing[19]. Treatment of elderly CRC patients remains challenging due to comorbidities, frailty, malnutrition, and impaired cognitive and functional status, despite advancements in surgical techniques and perioperative care[20]. Such complex patients are at higher risk for various postoperative complications after major surgery, including infectious complications and anastomotic leakage. Furthermore, elderly patients face an increased risk of mortality in the event of postoperative complications because of the impaired functional reserve. These risks often impact the surgeon’s decision-making, particularly in elderly patients with left sided CRC, where Hartmann’s procedure may be preferred over primary anastomosis[21].

Additionally, there is a lack of research examining the relationship between the overall survival rate of CRC patients within developing regions of Malaysia and its demographic and clinical characteristics. Despite numerous studies recording survival outcomes for CRC patients in various tertiary hospitals across Malaysia[22], no local studies have investigated perioperative survival outcomes in Kelantan, a developing state, within the past decade. It is important to establish the correlation between perioperative characteristics and treatment outcomes on overall survival to enhance cancer treatment and facilitate early detection.

As a result, we conducted this study to determine the 5-year overall survival rate of CRC patients who were treated at USM Specialist Hospital, a tertiary hospital in Kelantan, Malaysia, between January 2017 and December 2021. Furthermore, we evaluated the characteristics of CRC and examined the impact of clinical and treatment-related factors among elderly patients.

This is a cross-sectional study design using secondary data and STROBE guidelines conducted between January 2017 and December 2021. Retrospective chart review is a method used to retrieve data from patients’ medical records to address the research question. The study included all patients who were examined for CRC and had undergone surgery at USM Specialist Hospital, Kelantan, Malaysia.

Patient selection was based on specific inclusion and exclusion criteria. Included were medical records of male and female patients aged 65 years and above who underwent elective or emergency surgery, with pathologically confirmed primary adenocarcinoma located from the appendix to the rectum. Both laparoscopic and open surgical techniques were considered, along with patients who received neoadjuvant or adjuvant chemotherapy. Records of patients with recurrent cancer, metastases from other primary tumours, or those who underwent diversion without resection, as well as patients who did not undergo surgery or received palliative surgery, were also included. Patients aged below 65 years and cases with incomplete data were excluded.

Data was extracted from the patient folders and operation records for all patients who met the inclusion and exclusion criteria over the last 5 years.

The data was entered into Microsoft Excel. The Statistical Package for Social Science version 27 was used for all statistical analysis. Descriptive statistics were applied for data tabulation. Categorical variables such as gender, body mass index (BMI), and age group were described by n (%), and compared via the use of the χ2 test. The numerical variables were presented as mean ± SD and compared using the Student’s t-test. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

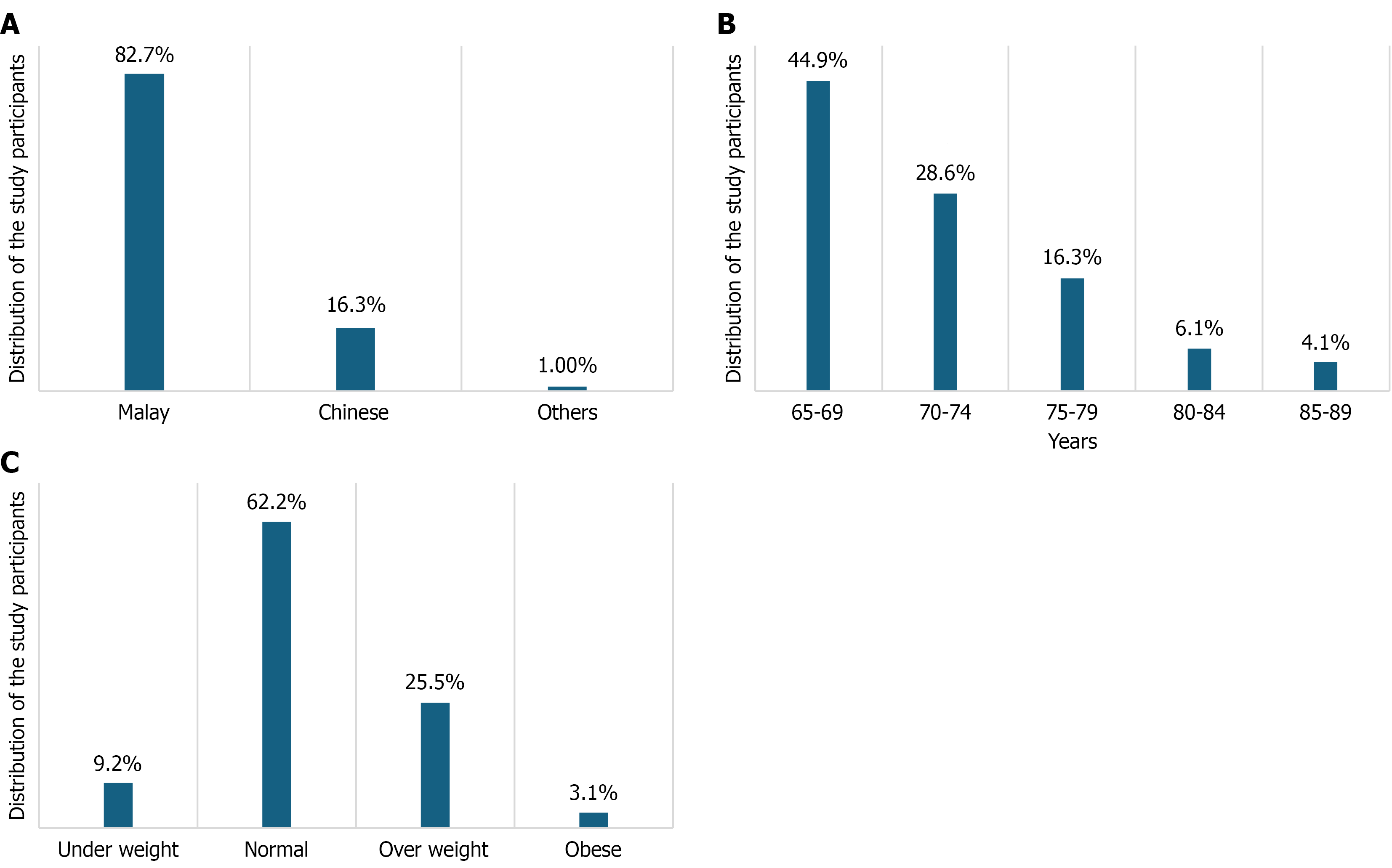

The study cohort comprised 98 elderly CRC patients, with a slight male predominance. A total of 56 patients (57.1%) were male and 42 (42.9%) were female. Ethnically, the sample was predominantly Malay, accounting for 81 participants (82.7%), followed by Chinese with 16 (16.3%), and one participant from other ethnic groups (1.0%; Figure 1A). The majority of patients were in the 65-69 years age bracket (n = 44, 44.9%), followed by 28 (28.6%) aged 70-74 years (Figure 1B). BMI analysis indicated that most patients had a normal BMI (n = 61, 62.2%), while 25 (25.5%) were classified as overweight (Figure 1C).

When examining the association between patient characteristics and age groups, BMI was the sole characteristic demonstrating a statistically significant association (P = 0.023; Table 1). The prevalence of obesity was notably highest among those aged 70-74 years and 75-79 years, each accounting for 33.3% of obese individuals within their respective age brackets. Gender distribution, with 40.5% of females and 48.2% of males in the 65-69 years group, did not differ significantly across age groups (P = 0.382), suggesting a consistent male predominance throughout the elderly cohort. Similarly, ethnicity did not exhibit a significant association with age groups (P = 0.724), with the overall ethnic composition remaining stable across different elderly age ranges.

| Characteristics | 65-69 years | 70-74 years | 75-79 years | 80-84 years | 85-89 years | χ2 (df) | P value |

| Gender | |||||||

| Female | 17 (40.5) | 10 (23.8) | 8 (19.0) | 4 (9.5) | 3 (7.1) | 4.31 (4) | 0.382 |

| Male | 27 (48.2) | 18 (32.1) | 8 (14.3) | 2 (3.6) | 1 (1.8) | ||

| Ethnicity | |||||||

| Malay | 39 (48.1) | 22 (27.2) | 12 (14.8) | 5 (6.2) | 3 (3.7) | 4.52 (8) | 0.724 |

| Chinese | 5 (31.3) | 5 (31.3) | 4 (25.0) | 1 (6.3) | 1 (6.3) | ||

| Others | 0 (0) | 1 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| BMI | |||||||

| Underweight | 2 (22.2) | 3 (33.3) | 1 (11.1) | 3 (33.3) | 0 (0) | 25.43 (12) | 0.023a |

| Normal | 28 (45.9) | 15 (24.6) | 12 (19.7) | 2 (3.3) | 4 (6.6) | ||

| Overweight | 14 (56.0) | 9 (36.0) | 2 (8.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Obese | 0 (0) | 1 (33.3) | 1 (33.3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| CEA (ng/mL) | 73.89 ± 174.25 | 329.25 ± 1318.30 | 63.18 ± 136.3 | 17.17 ± 16.64 | 4.63 ± 2.14 | - | 0.603 |

| CKD | |||||||

| No | 41 (45.6) | 26 (28.9) | 14 (15.6) | 6 (6.7) | 3 (3.3) | 2.59 (4) | 0.632 |

| Yes | 3 (37.5) | 2 (25.0) | 2 (25.0) | 0 (0) | 1 (12.5) | ||

| Hypertension | |||||||

| No | 17 (54.8) | 9 (29.0) | 3 (9.7) | 1 (3.2) | 1 (3.2) | 2.93 (4) | 0.598 |

| Yes | 27 (40.3) | 19 (28.4) | 13 (19.4) | 5 (7.5) | 3 (4.5) | ||

| Hyperlipidaemia | |||||||

| No | 35 (47.3) | 22 (29.7) | 10 (13.5) | 5 (6.8) | 2 (2.7) | 3.60 (4) | 0.49 |

| Yes | 9 (37.5) | 6 (25.0) | 6 (25.0) | 1 (4.2) | 2 (8.3) | ||

| Ischaemic heart disease | |||||||

| No | 37 (44.0) | 23 (27.4) | 14 (16.7) | 6 (7.1) | 4 (4.8) | 2.10 (4) | 0.753 |

| Yes | 7 (50.0) | 5 (35.7) | 2 (14.3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| ASA classification | |||||||

| Grade 1 | 5 (50.0) | 4 (40.0) | 1 (10.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 21.50 (16) | 0.186 |

| Grade 2 | 29 (50.9) | 16 (28.1) | 6 (10.5) | 4 (7.0) | 2 (3.5) | ||

| Grade 3 | 8 (29.6) | 8 (29.6) | 8 (29.6) | 2 (7.4) | 1 (3.7) | ||

| Grade 4 | 1 (50.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (50.0) | ||

| Grade 5 | 1 (50.0) | 0 (0) | 1 (50.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Tumour location | |||||||

| Left sided | 22 (40.7) | 17 (31.5) | 9 (16.7) | 3 (5.6) | 3 (5.6) | 17.74 (20) | 0.605 |

| Low rectum | 9 (56.3) | 4 (25.0) | 3 (18.8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Mid rectum | 5 (83.3) | 1 (16.7) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Multiple | 2 (66.7) | 1 (33.3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Right sided | 6 (37.5) | 3 (18.8) | 4 (25.0) | 2 (12.5) | 1 (6.3) | ||

| Upper rectum | 0 (0) | 2 (66.7) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Adjuvant | |||||||

| No | 37 (45.1) | 21 (25.6) | 14 (17.1) | 6 (7.3) | 4 (4.9) | 15.18 (16) | 0.418 |

| Chemoradiotherapy | 2 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Chemotherapy | 1 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Concurrent chemotherapy | 4 (33.3) | 7 (58.3) | 1 (8.3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Radiotherapy | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (100) | 0 | 0 (0) | ||

Preoperative carcinoembryonic antigen levels (e.g., 73.89 ± 174.25 ng/mL for 65-69 years) also showed no significant association with age (P = 0.603), indicating comparable baseline tumour marker levels across elderly age categories. The presence of chronic kidney disease (CKD) did not vary significantly by age group (P = 0.632), implying that this comorbidity was not disproportionately higher in older elderly patients. Likewise, hypertension (P = 0.598), hyperlipidemia (P = 0.490), and ischemic heart disease (IHD; P = 0.753) showed no significant association with age groups, suggesting these comorbidities were relatively evenly distributed across the elderly spectrum in this cohort.

American Society of Anesthesiologists classification, an assessment of operative risk, did not vary significantly across age groups (P = 0.186), indicating a generally consistent physiological status for surgery regardless of the specific elderly age subgroup. Tumour location (P = 0.605) and the type of preoperative adjuvant treatment (P = 0.418) also showed no significant association with age groups, indicating that anatomical distribution of CRC and the use of preoperative therapies were not influenced by the patient age within the elderly cohort.

Analysis of the relationship between participants’ pathology and age groups revealed significant associations with both the type of operation (P = 0.046) and PN stage (P = 0.027; Table 2). Open surgeries were more commonly performed in the younger elderly (65-69 years: 46.2%) but also notably prevalent in the very old (80-84 years: 12.8%; 85-89 years: 7.7%). In contrast, laparoscopic procedures were more prevalent among those aged 70-74 years (35.6%) and 75-79 years (16.9%), suggesting varied surgical approaches across different elderly age categories.

| Characteristics | 65-69 years | 70-74 years | 75-79 years | 80-84 years | 85-89 years | χ2 (df) | P value |

| Preoperative | 3.17 (4) | 0.558 | |||||

| No | 31 (41.9) | 23 (31.1) | 13 (17.6) | 5 (6.8) | 2 (2.7) | ||

| Yes | 13 (54.2) | 5 (20.8) | 3 (12.5) | 1 (4.2) | 2 (8.3) | ||

| Treatment type | 4.79 (8) | 0.756 | |||||

| Neoadjuvant | 7 (43.8) | 7 (43.8) | 2 (12.5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Palliative surgery | 1 (33.3) | 1 (33.3) | 1 (33.3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Surgery | 36 (45.6) | 20 (25.3) | 13 (16.5) | 6 (7.6) | 4 (5.1) | ||

| Operation type | 9.43 (4) | 0.046 | |||||

| Laparoscopy | 26 (44.1) | 21 (35.6) | 10 (16.9) | 1 (1.7) | 1 (1.7) | ||

| Open surgery | 18 (46.2) | 7 (17.9) | 6 (15.4) | 5 (12.8) | 3 (7.7) | ||

| PT stage | 10.61 (12) | 0.544 | |||||

| T1 | 1 (50.0) | 0 (0) | 1 (50.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| T2 | 10 (50.0) | 7 (35.0) | 1 (5.0) | 1 (5.0) | 1 (5.0) | ||

| T3 | 17 (34.0) | 16 (32.0) | 4 (8.0) | 3 (6.0) | 3 (6.0) | ||

| T4 | 16 (61.5) | 5 (19.2) | 1 (3.8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| PN stage | 16.83 (8) | 0.027 | |||||

| N0 | 20 (44.4) | 7 (15.6) | 13 (28.9) | 2 (4.4) | 3 (6.7) | ||

| N1 | 11 (42.3) | 11 (42.3) | 1 (3.8) | 3 (11.5) | 0 (0) | ||

| N2 | 13 (48.1) | 10 (37.0) | 2 (7.4) | 1 (3.7) | 1 (3.7) | ||

| M stage | 4.48 (4) | 0.357 | |||||

| M0 | 11 (37.9) | 8 (27.6) | 5 (17.2) | 2 (6.9) | 3 (10.3) | ||

| M1 | 33 (47.8) | 20 (29.0) | 11 (15.9) | 4 (5.8) | 1 (1.4) | ||

| Stage | 11.99 (12) | 0.431 | |||||

| Stage 1 | 3 (42.9) | 0 (0) | 2 (28.6) | 1 (14.3) | 1 (14.3) | ||

| Stage 2 | 5 (35.7) | 5 (35.7) | 3 (21.4) | 0 (0) | 1 (7.1) | ||

| Stage 3 | 3 (37.5) | 3 (37.5) | 0 (0) | 1 (12.5) | 1 (12.5) | ||

| Stage 4 | 33 (47.8) | 20 (29.0) | 11 (15.9) | 4 (5.8) | 1 (1.4) | ||

| Tumour size (mm) | 27.70 ± 25.11 | 17.80 ± 18.52 | 24.36 ± 21.22 | 21.98 ± 12.45 | 12.81 ± 4.82 | - | 0.341 |

Regarding lymph node involvement, the N2 stage was most common among participants aged 65-69 years (48.1%), whereas the N1 stage was more frequently observed in those aged 70-74 years (42.3%) and 80-84 years (11.5%). The N0 stage was most common in the 75-79 years (28.9%) and 85-89 years (6.7%) age groups, indicating potential differences in nodal burden distribution across elderly age cohorts. In this study, lymph node status (N0, N1, N2) was classified according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer 8th edition TNM system, based on the number of metastatic lymph nodes identified on postoperative histopathology. The M stage was primarily determined using preoperative imaging (computed tomography scan) and, where available, confirmed by postoperative histopathology, ensuring consistency with standard staging practices. Preoperative characteristics (P = 0.558) and overall treatment type (P = 0.756) did not significantly vary by age group, indicating consistent approaches to initial management regardless of age. Furthermore, PT stage (P = 0.544), M stage (P = 0.357), overall cancer stage (P = 0.431), and tumour size (P = 0.341) showed no significant association with age groups, implying that the extent of disease at presentation, including distant metastasis and tumour burden, was comparable across different elderly age ranges.

Examination of postoperative characteristics and their association with age groups revealed that adjuvant treatment was significantly associated with age groups (P = 0.006; Table 3). Among patients receiving adjuvant treatment, 52.2% were in the 65-69 years group, compared to 29.0% of those not receiving adjuvant treatment in the same age group. This record suggests that younger elderly patients are more likely to undergo adjuvant therapy, which may reflect considerations of treatment tolerance and anticipated benefit. For other postoperative characteristics, there was no significant association with age groups. The time to pass gas (P = 0.068) and stool (P = 0.194) did not vary significantly across age groups, suggesting similar patterns of bowel function recovery regardless of age within the elderly cohort. The time to initiation of oral feeding (P = 0.217) also showed no significant association with age, indicating a comparable pace of nutritional recovery across age groups.

| Characteristics | 65-69 years | 70-74 years | 75-79 years | 80-84 years | 85-89 years | χ2 (df) | P value |

| Gas | 35.95 (20) | 0.068 | |||||

| No | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Day 1 | 21 (45.7) | 13 (28.3) | 7 (15.2) | 3 (6.5) | 2 (4.3) | ||

| Day 2 | 13 (40.6) | 11 (34.4) | 5 (15.6) | 3 (9.4) | 0 (0) | ||

| Day 3 | 4 (44.4) | 3 (33.3) | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0) | 1 (11.1) | ||

| Day 4 | 6 (66.7) | 1 (11.1) | 2 (22.2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Day 5 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (100) | ||

| Stool | 34.23 (28) | 0.194 | |||||

| No | 0 (0) | 1 (50.0) | 1 (50.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Day 1 | 13 (39.4) | 10 (30.3) | 7 (21.2) | 1 (3.0) | 2 (6.1) | ||

| Day 2 | 12 (60.0) | 7 (35.0) | 1 (5.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Day 3 | 7 (46.7) | 3 (20.0) | 4 (26.7) | 1 (6.7) | 0 (0) | ||

| Day 4 | 4 (50.0) | 2 (25.0) | 0 (0) | 2 (25.0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Day 5 | 4 (40.0) | 3 (30.0) | 2 (20.0) | 1 (10.0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Day 6 | 2 (50.0) | 1 (25.0) | 1 (25.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Day 7 | 2 (33.3) | 1 (16.7) | 0 (0) | 1 (16.7) | 2 (33.3) | ||

| Oral feeding | 23.27 (16) | 0.217 | |||||

| No | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Day 1 | 37 (44.6) | 24 (28.9) | 14 (16.9) | 4 (4.8) | 4 (4.8) | ||

| Day 2 | 6 (50.0) | 4 (33.3) | 1 (8.3) | 1 (8.3) | 0 (0) | ||

| Day 5 | 1 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Day 6 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (100) | 0 (0) | ||

| Postop stay (day) | 9.75 ± 11.26 | 9.14 ± 6.56 | 12.31 ± 21.93 | 6.17 ± 1.33 | 7.00 ± 2.45 | - | 0.828 |

| Postop complication | 16.88 (24) | 0.775 | |||||

| Grade 1 | 31 (44.3) | 20 (28.6) | 11 (15.7) | 6 (8.6) | 2 (2.9) | ||

| Grade 2 | 4 (57.1) | 2 (28.6) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (14.3) | ||

| Grade 3 | 1 (33.3) | 1 (33.3) | 1 (33.3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Grade 3a | 0 (0) | 1 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Grade 3b | 4 (80.0) | 1 (20.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Grade 4b | 1 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Grade 5 | 3 (27.3) | 3 (27.3) | 4 (36.4) | 0 (0) | 1 (9.1) | ||

| Reoperation | 3.18 (4) | 0.535 | |||||

| No | 39 (42.9) | 26 (28.6) | 16 (17.6) | 6 (6.6) | 4 (4.4) | ||

| Yes | 5 (71.4) | 2 (28.6) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Adjuvant treatment | 13.81 (4) | 0.006 | |||||

| No | 9 (29.0) | 8 (25.8) | 10 (32.3) | 1 (3.2) | 3 (9.7) | ||

| Yes | 35 (52.2) | 20 (29.9) | 6 (9.0) | 5 (7.5) | 1 (1.5) | ||

| Recurrence | 4.52 (4) | 0.358 | |||||

| No | 22 (40.0) | 14 (25.5) | 11 (20.0) | 5 (9.1) | 3 (5.5) | ||

| Yes | 22 (51.2) | 14 (32.6) | 5 (11.6) | 1 (2.3) | 1 (2.3) | ||

| Follow-up | 4.81 (4) | 0.316 | |||||

| No | 29 (43.9) | 16 (24.2) | 12 (18.2) | 6 (9.1) | 3 (4.5) | ||

| Survive | 15 (46.9) | 12 (37.5) | 4 (12.5) | 0 (0) | 1 (3.1) |

Postoperative hospital stays (P = 0.828), measured as mean duration (e.g., 9.75 ± 11.26 days for patients aged 65-69 years), was not significantly associated with age, implying similar lengths of hospitalisation across different the elderly age groups. Postoperative complications, classified by Clavien-Dindo grades, did not significantly vary by age group (P = 0.775). While a higher prevalence of grade 4b complications was observed in patients aged 65-69 years (100%) and grade 3a in those aged 70-74 years (100%), these specific observations were not statistically significant when considering the overall distribution of all complication grades across all age groups. Reoperation rates (P = 0.535), recurrence rates (P = 0.358), and follow-up status (P = 0.316) also did not show a significant association with age, suggesting consistent needs for repeat surgeries, risk of cancer recurrence, and successful follow-up rates across the elderly cohort.

Analysis of factors associated with survival after follow-up identified BMI, IHD, and M stage as statistically significant predictors (Table 4). For BMI, overweight individuals were found to be 11.22 times more likely to survive compared to underweight patients [adjusted odds ratio (aOR) = 11.22, 95% confidence interval (95%CI): 1.57-80.31, P = 0.016]. This observation highlights the critical importance of adequate nutritional status for survival in elderly CRC patients, as being underweight presents a significant survival disadvantage. The presence of IHD significantly reduced survival, with affected individuals being 93% less likely to survive compared to those without IHD (aOR = 0.07, 95%CI: 0.01-0.74, P = 0.027). This record underscores IHD as a significant comorbidity negatively impacting long-term outcomes in this elderly cohort. Furthermore, M stage (distant metastasis) was a strong predictor of survival, with patients at M1 stage being 76% less likely to survive compared to those with M0 stage (aOR = 0.24, 95%CI: 0.08-0.75, P = 0.014). This finding is consistent with the established oncology principles, which distant metastatic disease is a major determinant of prognosis.

| Variable | aOR (95%CI) | Wald | P value |

| BMI | |||

| Underweight | 1 | ||

| Normal | 0.75 (0.13-4.44) | 0.1 | 0.752 |

| Overweight | 11.22 (1.57-80.31) | 5.797 | 0.016 |

| Obese | 0.76 (0.04-16.21) | 0.03 | 0.862 |

| Ischaemic heart disease | |||

| No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 0.07 (0.01-0.74) | 4.919 | 0.027 |

| M stage | |||

| M0 | 1 | ||

| M1 | 0.24 (0.08-0.75) | 6.013 | 0.014 |

CRC represents a significant global health burden, with its incidence steadily rising, particularly within older populations[23]. As life expectancy increases, a growing number of older adults are diagnosed with CRC, presenting unique challenges in their management due to age-related physiological changes, increased comorbidities, and potential functional limitations[24]. Despite this, older patients have historically been underrepresented in clinical trials, leading to a paucity of specific evidence-based guidelines for their treatment. Our study aimed to characterise the perioperative features and outcomes of older CRC patients undergoing surgery at a tertiary hospital in Malaysia, thereby contributing valuable regional data to better understand this vulnerable patient group and optimise their care. Critically, our findings reveal that BMI, ischaemic heart disease, and M stage are statistically significant predictors of patient survival, with adjuvant treatment also showing a significant association with recurrence and follow-up. Elderly CRC patients frequently present with comorbidities such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, IHD, and CKD, alongside functional limitations including frailty, impaired mobility, malnutrition, and sarcopenia, all of which complicate surgical decision-making and postoperative recovery. By examining patient characteristics, operative data, and postoperative outcomes, including survival, this research provides insights into local epidemiology and factors influencing prognosis, ultimately informing improved risk stratification and personalised treatment strategies to address existing gaps in the literature.

Our study observed a significant proportion of older patients, with the majority falling within the 65-69 years (44.9%) and 70-74 years (28.6%) age groups. This observation aligns with global trends illustrating an increasing incidence of CRC in older populations, where over half of new CRC diagnoses in the United States occur in individuals over 65 years[25]. Regarding gender, our findings indicate a male predominance (57.1% males vs 42.9% females). A recent study evaluating the global CRC incidence rates by Darmadi et al[24] revealed similar findings in 2025. Of 1931590 CRC cases worldwide, 55.5% occurred in males. Other studies, particularly in Asian contexts, also report a higher incidence in males, which is consistent with our results[26]. Moreover, mortality rates among men are higher compared to females. Conversely, some studies have reported a higher increase in CRC incidence among women aged 50-74 years compared to men, particularly among octogenarian cohorts[27,28]. Although incidence and crude mortality rates were higher among men and Chinese patients, our analysis found no significant differences in survival or cure rates by gender or ethnicity. This finding indicates that while disease burden varies across demographic groups, treatment outcomes in terms of survival remain independent of these factors. Our findings further illustrate that adjuvant therapy was significantly associated with a reduced risk of recurrence, supporting existing evidence that adjuvant chemotherapy can improve outcomes even in elderly CRC patients.

A key strength of our study is its focus on a predominantly Malay (82.7%) and Chinese (16.3%) population. This study provides crucial data from Southeast Asia, a region less frequently highlighted in broader cross-sectional studies which often focus on Western populations such as those utilising data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey in the United States. This regional focus helps to contextualise the unique epidemiological patterns and treatment responses across different ethnic groups. A previous retrospective study from Malaysia reported contrasting results, indicating that CRC incidence was the highest among Chinese patients, followed by Malays[29]. Another recent study from Malaysia reported a near equal distribution of incidence between Chinese (47%) and Malay (41.3) populations[11]. These differences in findings could be attributed to regional demographic variations, thereby necessitating further studies involving larger cohorts.

In this study, most participants had a normal BMI (62.2%), but the highest prevalence of obesity was observed in the 70-74 years and 75-79 years groups (33.3% each), with a significant association between BMI and age group (P = 0.023). This finding supports the general understanding of obesity as a risk factor for CRC[30]. However, contrasting findings exist with some research indicates that obese BMI is associated with early-onset CRC (18-49 years), but not necessarily with older adults (≥ 50 years)[31]. A study by Liu et al[30] in 2019 reported that obesity nearly doubled the risk of early-onset CRC among women. Additionally, studies exploring other adiposity measures like relative fat mass (RFM) or a body shape index, suggest complex, age-modified relationships with CRC prevalence[32]. RFM has been reported to be strongly associated with CRC prevalence among the elderly. However, another study reported that underweight CRC patients had worse survival than non-underweight patients[33]. These varying findings underscore the need for further research into the nuanced effects of BMI and body composition on CRC across different age and ethnic groups. In our cohort, recurrence was significantly associated with both adjuvant therapy and follow-up status, underscoring the importance of sustained surveillance and treatment adherence in reducing the likelihood of cancer recurrence.

In addition, this study identified M stage (metastatic status) as a significant predictor of survival. This observation is consistent with established prognostic factors for CRC, which include the degree of tumour penetration, nodal in

Furthermore, our finding that ischaemic heart disease significantly predicts patient survival is in line with previous literature. Patients with pre-existing cardiovascular diseases (CVD) including ischaemic heart disease are reported to have poorer outcomes than those without CVD[38]. Elderly CRC patients often present with multiple comorbidities, which significantly increase the risk of postoperative complications, morbidity, and mortality. Studies have specifically linked sarcopenia, when combined with nutritional disorders and open surgical approaches, to increased short-term postoperative complications in older patients with CRC[39].

This study also found a significant association between adjuvant treatment and both recurrence and follow-up status. These findings are consistent with a previous study by Zare-Bandamiri et al[38] in 2017, which reported adjuvant therapy had a significant association with cancer recurrence. This supports the evidence that adjuvant chemotherapy can benefit older patients with stage III colon cancer, with its effectiveness being independent of age and comorbidity[39]. However, a persistent challenge remains with older patients are often less likely to receive standard adjuvant therapy due to concerns about treatment toxicity, existing comorbidities, and overall quality of life. This discrepancy between the potential benefit and actual receipt of treatment highlights a crucial area for improved clinical guidelines and patient management in geriatric oncology.

The limitations of this study include, firstly, its cross-sectional design, which captures data at a single point in time and inherently limits our ability to establish causal relationships between observed characteristics and outcomes. Furthermore, the relatively small sample size of 98 participants, while providing initial insights, restricts the generalisability of our findings to the broader elderly CRC population in Malaysia or other regions. A larger cohort would enable more robust statistical analysis, facilitate the detection of subtler associations, and allow for more precise risk stratification. Future research employing longitudinal designs and larger, multi-centre cohorts would therefore offer a more comprehensive and reliable understanding of perioperative characteristics and long-term outcomes in this important patient group.

In summary, our study on older CRC patients in a Malaysian tertiary hospital revealed a male predominance within a predominantly Malay and Chinese cohort. While most patients presented with a normal BMI, obesity was significantly associated with specific older age groups. Surgically, both the type of operation and lymph node involvement were significantly associated with age, while adjuvant treatment was found to be significantly linked to recurrence and follow-up. Crucially, our findings highlight that BMI, ischaemic heart disease, and the presence of distant metastases (M stage) are statistically significant predictors of patient survival. These insights are vital for tailoring perioperative management and prognostic assessment in older CRC patients in this region, contributing to a more nuanced understanding of this vulnerable population. Investigating the reasons behind differential adjuvant treatment in older age groups is also crucial to ensure equitable access to potentially beneficial therapies, whilst also examining the effectiveness and toxicity of these treatments in real-world older patient populations. Finally, comparative studies involving other Asian and Western cohorts, utilising standardised data collection methods, would contribute to a more comprehensive global understanding of CRC management in older adults.

The authors would like to express gratitude to Associate Professor Maya Mazuwin Yahya, Head of the Department of Surgery, and all faculty members for their assistance and contributions to this study.

| 1. | Viale PH. The American Cancer Society's Facts & Figures: 2020 Edition. J Adv Pract Oncol. 2020;11:135-136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 21.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Siegel RL, Jakubowski CD, Fedewa SA, Davis A, Azad NS. Colorectal Cancer in the Young: Epidemiology, Prevention, Management. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2020;40:1-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 19.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Beckmann KR, Bennett A, Young GP, Cole SR, Joshi R, Adams J, Singhal N, Karapetis C, Wattchow D, Roder D. Sociodemographic disparities in survival from colorectal cancer in South Australia: a population-wide data linkage study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Perron L, Daigle JM, Vandal N, Guertin MH, Brisson J. Characteristics affecting survival after locally advanced colorectal cancer in Quebec. Curr Oncol. 2015;22:e485-e492. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Bu H, Li YL. Pathology. 9th ed. Li YL, Lai MD, Wang YL, Wang GP, Tao YS, editors. Beijing: People's Medical Publishing House, 2018. |

| 6. | Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75126] [Cited by in RCA: 68881] [Article Influence: 13776.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (202)] |

| 7. | Xi Y, Xu P. Global colorectal cancer burden in 2020 and projections to 2040. Transl Oncol. 2021;14:101174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 687] [Cited by in RCA: 1591] [Article Influence: 318.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (7)] |

| 8. | Pardamean CI, Sudigyo D, Budiarto A, Mahesworo B, Hidayat AA, Baurley JW, Pardamean B. Changing Colorectal Cancer Trends in Asians: Epidemiology and Risk Factors. Oncol Rev. 2023;17:10576. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Sung JJ, Ng SC, Chan FK, Chiu HM, Kim HS, Matsuda T, Ng SS, Lau JY, Zheng S, Adler S, Reddy N, Yeoh KG, Tsoi KK, Ching JY, Kuipers EJ, Rabeneck L, Young GP, Steele RJ, Lieberman D, Goh KL; Asia Pacific Working Group. An updated Asia Pacific Consensus Recommendations on colorectal cancer screening. Gut. 2015;64:121-132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 332] [Cited by in RCA: 330] [Article Influence: 30.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Erratum: Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70:313. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 310] [Cited by in RCA: 476] [Article Influence: 79.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 11. | Muhamad NA, Ma'amor NH, Rosli IA, Leman FN, Abdul Mutalip MH, Chan HK, Yusof SN, Tamin NSI, Aris T, Lai NM, Abu Hassan MR. Colorectal cancer survival among Malaysia population: data from the Malaysian National Cancer Registry. Front Oncol. 2023;13:1132417. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Lim KG, Lee CS, Chin DHJ, Ooi YS, Veettil SK, Ching SM, Burud IAS, Zakaria J. Clinical characteristics and predictors of 5-year survival among colorectal cancer patients in a tertiary hospital in Malaysia. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2020;11:250-259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Magaji BA, Moy FM, Roslani AC, Law CW. Survival rates and predictors of survival among colorectal cancer patients in a Malaysian tertiary hospital. BMC Cancer. 2017;17:339. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Haggar FA, Boushey RP. Colorectal cancer epidemiology: incidence, mortality, survival, and risk factors. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2009;22:191-197. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1215] [Cited by in RCA: 1425] [Article Influence: 95.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Ghazali AK, Musa KI, Naing NN, Mahmood Z. Prognostic factors in patients with colorectal cancer at Hospital Universiti Sains Malaysia. Asian J Surg. 2010;33:127-133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Wan Puteh SE, Saad NM, Aljunid SM, Abdul Manaf MR, Sulong S, Sagap I, Ismail F, Muhammad Annuar MA. Quality of life in Malaysian colorectal cancer patients. Asia Pac Psychiatry. 2013;5 Suppl 1:110-117. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Yusoff SN, Zulkifli Z. Rethinking of old age: the emerging challenge for Malaysia. Int Proc Econ Dev Res. 2014;71:69-73. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 18. | Syful Azlie MF, Hassan MR, Junainah S, Rugayah B. Immunochemical faecal occult blood test for colorectal cancer screening: a systematic review. Med J Malaysia. 2015;70:24-30. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Itatani Y, Kawada K, Sakai Y. Treatment of Elderly Patients with Colorectal Cancer. Biomed Res Int. 2018;2018:2176056. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Robinson TN, Wu DS, Pointer L, Dunn CL, Cleveland JC Jr, Moss M. Simple frailty score predicts postoperative complications across surgical specialties. Am J Surg. 2013;206:544-550. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 311] [Cited by in RCA: 385] [Article Influence: 29.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Hallam S, Mothe BS, Tirumulaju R. Hartmann's procedure, reversal and rate of stoma-free survival. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2018;100:301-307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Lu J, Tan KY. Colorectal cancer: Getting the perspective and context right. World J Clin Oncol. 2024;15:599-602. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Chong RC, Ong MW, Tan KY. Managing elderly with colorectal cancer. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2019;10:1266-1273. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Darmadi D, Mohammadian-Hafshejani A, Kheiri S. Global Disparities in Colorectal Cancer: Unveiling the Present Landscape of Incidence and Mortality Rates, Analyzing Geographical Variances, and Assessing the Human Development Index. J Prev Med Hyg. 2025;65:E499-E514. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Fu M, Li Y, Wang J. Incidence and Mortality of Colorectal Cancer in Asia in 2022 and Projections for 2050. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2025;40:1143-1156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Alsadhan N, Pujades-Rodriguez M, Alhurishi SA, Shuweihdi F, Brennan C, West RM. Temporal trends in age and stage-specific incidence of colorectal cancer in Saudi Arabia: A registry-based cohort study between 1997 and 2017. Cancer Epidemiol. 2024;93:102699. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Abu Hassan MR, Ismail I, Mohd Suan MA, Ahmad F, Wan Khazim WK, Othman Z, Mat Said R, Tan WL, Mohammed SRNS, Soelar SA, Nik Mustapha NR. Incidence and mortality rates of colorectal cancer in Malaysia. Epidemiol Health. 2016;38:e2016007. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Ye P, Xi Y, Huang Z, Xu P. Linking Obesity with Colorectal Cancer: Epidemiology and Mechanistic Insights. Cancers (Basel). 2020;12:1408. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 17.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 29. | Xu W, He Y, Wang Y, Li X, Young J, Ioannidis JPA, Dunlop MG, Theodoratou E. Risk factors and risk prediction models for colorectal cancer metastasis and recurrence: an umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses of observational studies. BMC Med. 2020;18:172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 17.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Liu PH, Wu K, Ng K, Zauber AG, Nguyen LH, Song M, He X, Fuchs CS, Ogino S, Willett WC, Chan AT, Giovannucci EL, Cao Y. Association of Obesity With Risk of Early-Onset Colorectal Cancer Among Women. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5:37-44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 424] [Cited by in RCA: 388] [Article Influence: 55.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 31. | Wang Y, Song S, Zhang L, Zhang J. Association between relative fat mass and colorectal cancer: a cross-sectional study. Front Nutr. 2025;12:1555435. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Chen K, Collins G, Wang H, Toh JWT. Pathological Features and Prognostication in Colorectal Cancer. Curr Oncol. 2021;28:5356-5383. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 171] [Article Influence: 34.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Amir PN, Avoi R, Yusof SN, Syed Abdul Rahim SS, Robinson F, Giloi N, Abd Rahim MA, Oo Tha N, Ibrahim MY, Jeffree MS, Hayati F. Survival Rate and Prognostic Factors for Colorectal Cancer in Sabah, Borneo, Malaysia: A Retrospective Cohort of a Population-Based Study. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2022;23:1885-1892. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Lewis SL, Stewart KE, Garwe T, Sarwar Z, Morris KT. Retrospective Cohort Analysis of the Effect of Age on Lymph Node Harvest, Positivity, and Ratio in Colorectal Cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14:3817. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Liu T, Jiao S, Gao S, Shi Y. Optimal lymph node yield for long-term survival in elderly patients with right-sided colon cancer: a large population-based cohort study. BMC Cancer. 2025;25:590. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | O'Neill C, Donnelly DW, Harbinson M, Kearney T, Fox CR, Walls G, Gavin A. Survival of cancer patients with pre-existing heart disease. BMC Cancer. 2022;22:847. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Leščák Š, Košíková M, Jenčová S. Sarcopenia as a Prognostic Factor for the Outcomes of Surgical Treatment of Colorectal Carcinoma. Healthcare (Basel). 2025;13:726. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Zare-Bandamiri M, Fararouei M, Zohourinia S, Daneshi N, Dianatinasab M. Risk Factors Predicting Colorectal Cancer Recurrence Following Initial Treatment: A 5-year Cohort Study. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2017;18:2465-2470. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Wildes TM, Kallogjeri D, Powers B, Vlahiotis A, Mutch M, Spitznagel EL Jr, Tan B, Piccirillo JF. The Benefit of Adjuvant Chemotherapy in Elderly Patients with Stage III Colorectal Cancer is Independent of Age and Comorbidity. J Geriatr Oncol. 2010;1:48-56. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/