Published online Jan 27, 2026. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v18.i1.113046

Revised: October 9, 2025

Accepted: November 19, 2025

Published online: January 27, 2026

Processing time: 140 Days and 1.5 Hours

Traditional laparoscopic total mesorectal excision (LaTME) presents challenges in patients with low rectal cancer, including difficult surgical exposure and positive margin risks.

To compare the short-term outcomes of laparoscopic-assisted transanal total mesorectal excision (TaTME) and LaTME for mid-to-low rectal cancer.

A retrospective analysis of 138 patients with rectal cancer was conducted, and they were divided into the TaTME group (n = 66) and the LaTME group (n = 72). Surgical indicators, pathological outcomes, recovery parameters, inflammatory markers, and anal function were compared.

The two groups showed comparable baseline characteristics (P > 0.05). The TaTME group demonstrated superior intraoperative performance with signi

TaTME demonstrates superior short-term outcomes in surgical safety, oncological quality, and functional recovery to LaTME, warranting clinical promotion.

Core Tip: This retrospective study compared laparoscopic-assisted transanal total mesorectal excision (TaTME) with traditional laparoscopic total mesorectal excision in 138 patients with mid-to-low rectal cancer. TaTME demonstrated significant advantages including reduced intraoperative blood loss, superior oncological outcomes with lower circumferential resection margin positivity rates and higher lymph node harvest, accelerated postoperative recovery, attenuated inflammatory response, and better anal function preservation. Multivariate analysis identified TaTME as an independent protective factor for good anal function. These findings suggest TaTME is a safer and more effective surgical approach for mid-to-low rectal cancer, warranting broader clinical adoption.

- Citation: Huang Q, Li Y, Feng SD, Fang YC, Zhou YH, Li DW, Liao ZW. Short-term outcomes of laparoscopic-assisted transanal vs laparoscopic total mesorectal excision for mid-to-low rectal cancer. World J Gastrointest Surg 2026; 18(1): 113046

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v18/i1/113046.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v18.i1.113046

Rectal cancer, one of the most common malignant tumors of the digestive tract globally, has shown an increasing annual incidence and has become an important disease threatening human health. According to global cancer statistics, rectal cancer accounts for 5% of all malignant tumors and is the fourth most common cancer type in adults. The incidence of rectal cancer significantly varies by region, with higher rates in Japan, Eastern Europe, and Northern Europe (≥ 15 cases/100000/year), whereas rates are relatively lower in Africa and Asia. Notably, China, as a high-incidence area for rectal cancer in East Asia, has shown increasing trends in both incidence and mortality rates in recent years; some regions have incidence rates higher than the global average, posing enormous challenges to China’s healthcare system[1-3].

Currently, the treatment for rectal cancer has developed into a comprehensive treatment model that centers on surgical treatment, combined with medical radiotherapy and chemotherapy, biological targeted therapy, and other approaches. In this comprehensive treatment system, surgical treatment remains the most critical component, directly affecting patient prognosis and quality of life[4,5]. However, owing to the deep pelvic location, complex anatomical structure, and proximity of the rectum to important organs such as the bladder, prostate, and uterus, rectal cancer surgery presents considerable technical difficulty and challenges[6].

Since Bill Heald first proposed the concept of total mesorectal excision (TME) in 1982, this surgical concept has been continuously refined through over 30 years of clinical practice and has been established as the current “gold standard” for radical rectal cancer surgery[7]. TME emphasizes the complete excision of the rectal mesentery within the anatomical plane formed during embryonic development, maximally clearing possible micrometastases while protecting the pelvic autonomic nerves, thereby significantly reducing local recurrence rates and improving the long-term survival and quality of life of patients. With the vigorous development of minimally invasive surgical techniques, traditional open TME has gradually been replaced by laparoscopic TME (LaTME)[8,9].

Clinical randomized controlled studies have confirmed that LaTME has equivalent oncological outcomes to open TME while having advantages in minimally invasive aspects, such as reduced intraoperative blood loss, faster postoperative gastrointestinal function recovery, less postoperative pain, and shorter hospital stays. These advantages have led to the widespread use and recognition of LaTME in clinical practice[10-12]. However, LaTME has certain limitations. First, this technique has a relatively long learning curve and requires high technical skills from surgeons. Second, for certain special patient groups, including those with obesity, patients with narrow pelvis, and male patients with enlarged prostate, the purely transabdominal top-down approach can still pose challenges in adequately exposing the distal rectal surgical field. This difficulty may increase the risk of positive distal and circumferential margins and potential iatrogenic injury to related organs. For low rectal cancers specifically, the transanal bottom-up approach of transanal TME (TaTME) directly overcomes the visualization challenges inherent to LaTME's top-down technique. The transanal approach provides superior magnified visualization of the distal rectum after insufflation, enabling more precise identification of the mesorectal fascia and ensuring adequate distal and circumferential margins. This is particularly advantageous in patients with narrow pelvis, obesity, or bulky tumors where traditional laparoscopic instruments struggle to reach the pelvic floor. Furthermore, the direct access to the distal dissection plane allows better preservation of pelvic autonomic nerves, potentially reducing postoperative genitourinary and anorectal dysfunction.

Against this background, TaTME emerged as a new surgical approach that has received much attention in the field of gastrointestinal surgery recently. The core concept of TaTME is the transanal approach, which involves dissecting the rectal mesentery layer by layer from bottom to top following TME principles until the inferior mesenteric vessels’ root is reached, achieving radical rectal cancer resection. In 2010, some studies successfully performed the world’s first TaTME on a patient with rectal cancer after neoadjuvant chemotherapy, marking the official introduction of this technique[13,14].

According to whether laparoscopic technology is combined, TaTME can be divided into complete [pure natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery (NOTES) TaTME] and laparoscopic-assisted TaTME. Although a complete transanal operation is technically feasible and conforms to the principles of NOTES, it first contacts the tumor site, which inhibits complete exploration of the abdominal cavity and assessment of tumor invasion and lymph node metastasis. As a result, it does not conform to the basic principles of radical tumor surgery, leading to a gradual decline in its clinical application. In contrast, laparoscopic-assisted TaTME combines the respective advantages of transabdominal and transanal app

The technical advantages of laparoscopic-assisted TaTME are mainly reflected in certain aspects. First, the transanal approach allows for clear exposure of the surgical field after rectal insufflation and magnification, which increases the accuracy in identifying lesions and surrounding tissue structures. Second, the mobilization and excision of distal rectal mesentery are more convenient, particularly for patients with low rectal cancer, ensuring negative circumferential resection margins (CRMs) of surgical specimens. Finally, this technique can cover the lower, middle, and upper segments of the rectum, demonstrating good applicability[16].

Despite encouraging preliminary research results, no high-level domestic and international evidence-based medical evidence can comprehensively confirm the safety, feasibility, and effectiveness of laparoscopic-assisted TaTME. With regard to postoperative anal function recovery, whether laparoscopic-assisted TaTME is truly superior to LaTME remains controversial, as objective functional assessment data are lacking. Additionally, research on the effect of this technique on body inflammatory response, postoperative pain degree, and complication rates is relatively limited. Therefore, conducting high-quality clinical controlled studies has important clinical significance and academic value to comprehensively evaluate the short-term efficacy of laparoscopic-assisted TaTME and provide reliable evidence-based medical evidence for clinical practice.

This retrospective study collected clinical data from patients who underwent radical rectal cancer surgery at Shanghai Cancer Hospital and Renhe Hospital, Baoshan District, between October 2019 and October 2020. The hospital ethics committee approved the research protocol, and all patients signed informed consent forms.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Preoperative colonoscopy and pathological biopsy confirmation of rectal adenocarcinoma; (2) Age 18-85 years; (3) Middle and low rectal cancer with tumor distance from the dentate line < 5 cm; (4) Rectal tumor maximum diameter < 5 cm; (5) Clinical staging assessed by magnetic resonance imaging or endoscopic ultrasound of the pelvis as cT1-3N0-2M0; (6) Tumor not invading the levator ani complex or external sphincter; (7) Normal preoperative anal function with good sphincter contraction function; (8) Absence of emergency surgery indications such as intestinal obstruction or perforation; (9) Exclusion of distant metastasis and local recurrence cases; (10) May or may not have received preoperative neoadjuvant radiochemotherapy; and (11) Complete clinical data and follow-up information available.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Mental disorders or cognitive dysfunction, combined acute intestinal ob

According to the surgical approach, 138 patients who met the inclusion criteria were divided into the TaTME group (laparoscopic-assisted TaTME, n = 66) and LaTME group (traditional LaTME, n = 72). Surgical approach selection was determined through multidisciplinary team (MDT) meetings involving colorectal surgeons, radiologists, and oncologists. The MDT reviewed preoperative imaging [magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography], tumor characteristics (location, size, T-stage), patient anatomy [pelvic dimensions, body mass index (BMI)], and surgeon expertise. TaTME was preferentially considered for tumors ≤ 5 cm from the anal verge, narrow pelvis (interspinous distance < 10 cm), or predicted difficult distal access based on MRI assessment. LaTME was selected when conventional laparoscopic access was deemed adequate. All patients were counseled regarding both approaches, and final decisions incorporated patient preferences. All surgeries were performed by attending physicians with extensive experience in laparoscopic rectal cancer surgery.

This investigation documented multiple categories of data: (1) Demographic and clinical characteristics at baseline [including participant age, gender, BMI, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification, anatomical tumor site, carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) levels before surgery, initial clinical stage, and whether neoadjuvant therapy was administered]; (2) Operative parameters (encompassing procedural duration, volume of blood lost during surgery, frequency of intraoperative transfusions, incidence of organ damage during the procedure, rate of protective stoma creation, and instances requiring conversion to open technique); (3) Histopathological findings (comprising maximum tumor dimension, distance to the distal resection margin, CRM involvement, total number of lymph nodes retrieved, count of metastatic lymph nodes, pathological TNM classification, degree of cellular differentiation, and presence of vascular infiltration); and (4) Postoperative rehabilitation metrics [Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) pain intensity scores, timing of initial passage of flatus, timing of first defecation, duration of postoperative hospitalization, and adverse events occurring within the initial 30-day postoperative period].

Pain intensity following surgery was quantified using the VAS system (scaled from 0 to 10) at three time points: The first, second, and third days after the operation. Classification of postoperative adverse events followed the Clavien-Dindo grading system, encompassing three categories: (1) Anastomosis-specific complications (including leakage at the anastomotic site, hemorrhage from the anastomosis, and narrowing of the anastomotic junction); (2) Complications common to surgical procedures (such as surgical site infections, abscess formation in the pelvic cavity, bowel obstruction, and inability to void urine); and (3) Systemic complications (including respiratory tract infections, formation of deep venous thrombi, and events affecting the cardiovascular system).

Assessment of inflammatory markers involved obtaining 5 mL peripheral venous blood samples under fasting conditions during early morning hours on the first three postoperative days. Serum levels of tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interleukin (IL)-2, and IL-6 were quantified through enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay methodology. Evaluation of anal sphincter function occurred at the 3-month postoperative mark, utilizing three instruments: (1) The Wexner incontinence scoring system (ranging 0-20, with elevated scores reflecting diminished function); (2) The Kirwan classification of anal function (spanning grades I through V); and (3) The ligament advanced reinforcement system (LARS) scoring system.

The investigation designated the 30-day postoperative complication rate as its principal outcome measure, specifically focusing on Clavien-Dindo grade ≥ II events, which encompassed anastomotic leakage, bleeding episodes, surgical site infections, pelvic abscess development, and bowel obstruction. Additional outcome measures comprised multiple domains: (1) Technical surgical parameters (including procedural time, intraoperative hemorrhage volume, rate of conversion to open approach, and frequency of intraoperative organ injury); (2) Oncological parameters (encompassing positive CRM rate, lymph node yield, and R0 resection achievement rate); (3) Postoperative convalescence indicators (including pain severity, time required for gastrointestinal function restoration, and hospitalization duration); (4) Inflammatory markers (tracking postoperative fluctuations in serum TNF-α, IL-2, and IL-6 concentrations); (5) Functional assessment (results of anal function evaluation at 3 months postoperatively); and (6) Quality of life metrics (quality of life scores obtained 3 months after surgery).

The present investigation employed mean ± SD for representing continuous data, whereas categorical data were displayed as n (%). Between-group comparisons of continuous variables utilized independent sample t-tests, while categorical variables were analyzed using χ2 tests or Fisher's exact probability tests when appropriate. Statistical significance was determined using two-tailed tests, with α set at 0.05. For determining risk factors associated with suboptimal postoperative anal function, the analytical approach proceeded in stages. First, univariate logistic regression screening identified potential predictive variables. Subsequently, variables demonstrating P < 0.05 during univariate screening were incorporated into a multivariate logistic regression framework to derive odds ratios accompanied by their corresponding 95%CI.

No significant differences were found between the two groups in terms of age, sex, BMI, ASA score, tumor location, preoperative CEA level, preoperative clinical staging, and neoadjuvant treatment proportion (P > 0.05). In the TaTME and LaTME groups, the average ages were 62.4 ± 11.2 years and 64.1 ± 10.8 years; male proportion were 60.6% (40/66) and 63.9% (46/72); average BMI were 23.8 ± 3.2 kg/m2 and 24.3 ± 3.5 kg/m2; tumor distances from the anal verge were 3.2 ± 1.1 cm and 3.4 ± 1.3 cm, respectively. Moreover, in the TaTME and LaTME groups, the preoperative CEA levels were 8.9 ± 12.4 ng/mL and 9.7 ± 15.2 ng/mL (P = 0.743), 87.9% (58/66) and 84.7% (61/72) had ASA scores I and II (P = 0.569), 28.8% (19/66) and 31.9% (23/72) had neoadjuvant radiochemotherapy (P = 0.683), and 75.8% (50/66) and 77.8% (56/72) had cT3 stage tumor (P = 0.777), respectively. Moreover, no significant differences in comorbidities (hypertension, diabetes, and coronary heart disease) and previous abdominal surgery history were found between the two groups (P > 0.05; Table 1).

| Variable | Transanal total mesorectal excision group (n = 66) | Laparoscopic total mesorectal excision group (n = 72) | Statistical value | P value |

| Age (years) (mean ± SD) | 62.4 ± 11.2 | 64.1 ± 10.8 | t = 0.928 | 0.356 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 40 (60.6) | 46 (63.9) | χ2 = 0.148 | 0.701 |

| Female | 26 (39.4) | 26 (36.1) | ||

| Body mass index (kg/m2) (mean ± SD) | 23.8 ± 3.2 | 24.3 ± 3.5 | t = 0.878 | 0.382 |

| American Society of Anesthesiologists score | ||||

| Grades I and II | 58 (87.9) | 61 (84.7) | χ2 = 0.284 | 0.569 |

| Grade III | 8 (12.1) | 11 (15.3) | ||

| Distance from the anal verge (cm) (mean ± SD) | 3.2 ± 1.1 | 3.4 ± 1.3 | t = 0.974 | 0.332 |

| Preoperative carcinoembryonic antigen level (ng/mL) (mean ± SD) | 8.9 ± 12.4 | 9.7 ± 15.2 | t = 0.329 | 0.743 |

| Clinical T stage | ||||

| cT1 and cT2 | 16 (24.2) | 16 (22.2) | χ2 = 0.082 | 0.777 |

| cT3 | 50 (75.8) | 56 (77.8) | ||

| Clinical N stage | ||||

| cN0 | 28 (42.4) | 32 (44.4) | χ2 = 0.056 | 0.813 |

| cN1 and cN2 | 38 (57.6) | 40 (55.6) | ||

| Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy | 19 (28.8) | 23 (31.9) | χ2 = 0.167 | 0.683 |

| Tumor differentiation | ||||

| Well-moderate | 58 (87.9) | 61 (84.7) | χ2 = 0.284 | 0.594 |

| Poor | 8 (12.1) | 11 (15.3) | ||

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Hypertension | 24 (36.4) | 28 (38.9) | χ2 = 0.095 | 0.758 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 12 (18.2) | 16 (22.2) | χ2 = 0.350 | 0.554 |

| Coronary artery disease | 8 (12.1) | 11 (15.3) | χ2 = 0.284 | 0.594 |

| Previous abdominal surgery | 6 (9.1) | 9 (12.5) | χ2 = 0.415 | 0.519 |

The TaTME group had significantly less intraoperative blood loss than the LaTME group (78.4 ± 28.6 mL vs 118.7 ± 35.2 mL, P < 0.001).

The significantly reduced blood loss in TaTME (78.4 ± 28.6 mL vs 118.7 ± 35.2 mL, P < 0.001; 95%CI: 28.7-51.9) likely results from improved surgical field visualization after transanal insufflation, allowing precise identification and management of mesorectal vessels, particularly the middle and inferior rectal vessels. The magnified view and direct access reduce inadvertent tissue trauma during distal dissection. The intraoperative transfusion rates were 4.5% (3/66) in the TaTME group and 11.1% (8/72) in the LaTME group; this difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.154). No major intraoperative bleeding occurred in either group. The intraoperative transfusion volume was 180 ± 45 mL in the TaTME group and 220 ± 68 mL in the LaTME group (P = 0.312). The intraoperative hemoglobin decrease was 18.3 ± 8.7

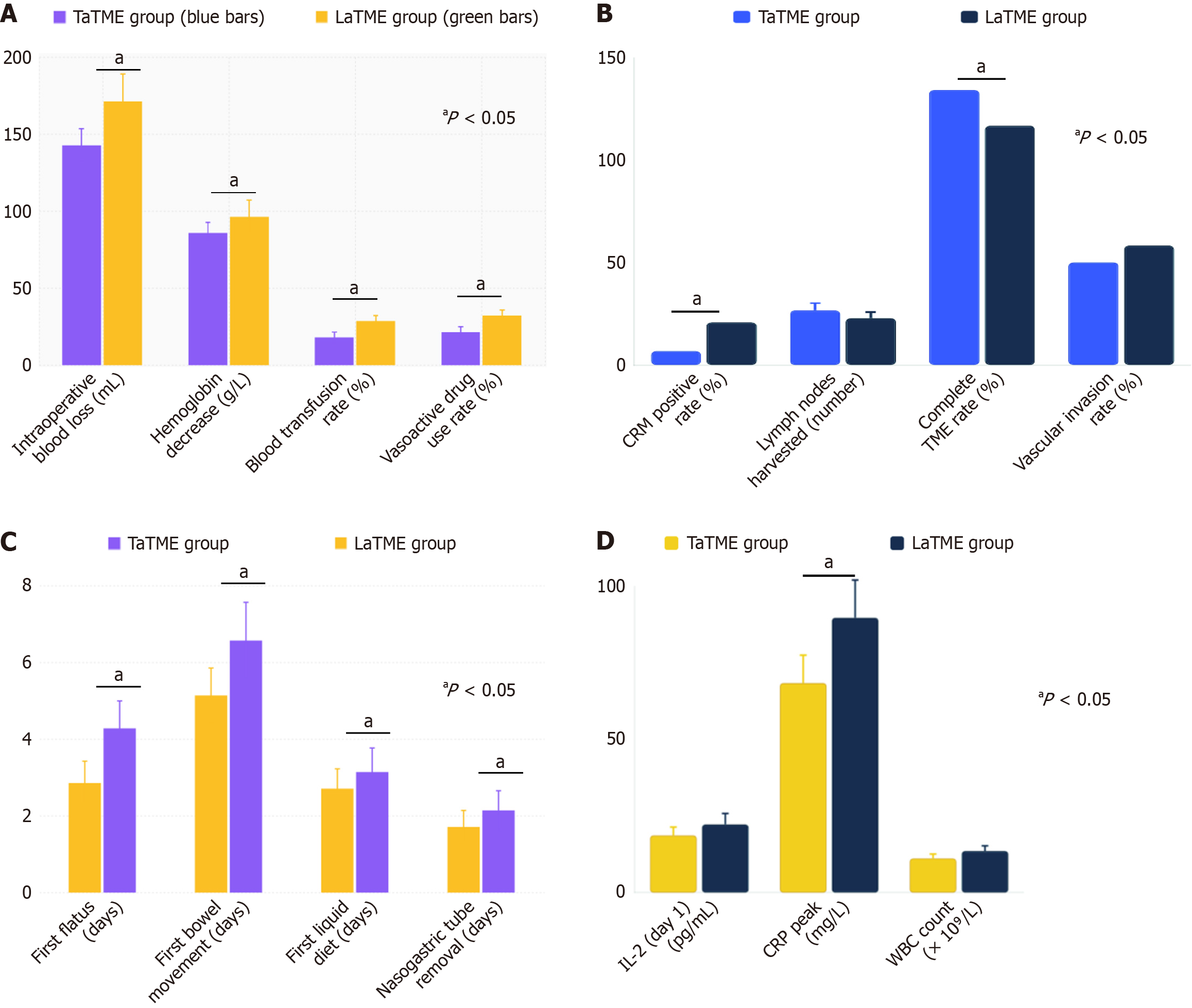

The TaTME group demonstrated significantly lesser intraoperative blood loss (78.4 ± 28.6 mL vs 118.7 ± 35.2 mL), lesser reduction in hemoglobin levels (18.3 ± 8.7 g/L vs 26.8 ± 12.4 g/L), and lower rates of blood transfusion (4.5% vs 11.1%) and vasoactive drug usage (6.1% vs 15.3%) than the LaTME group. These findings indicate that TaTME is associated with superior intraoperative hemodynamic stability and reduced surgical trauma (Figure 1A).

The TaTME group had a significantly lower CRM-positive rate than the LaTME group (4.5% vs 13.9%, P = 0.032). The lower CRM-positive rate in TaTME (4.5% vs 13.9%, P = 0.032; 95%CI: 1.2%-17.6%) is clinically significant, as positive CRM is strongly associated with local recurrence rates of 15%-20% compared to < 5% with negative margins, and represents an independent predictor of disease-free survival in rectal cancer patients. The TaTME group had a higher total lymph node harvest (17.8 ± 4.6 vs 15.2 ± 4.1, P = 0.001). However, no significant between-group differences were found in tumor maximum diameter (3.8 ± 1.2 cm vs 4.1 ± 1.4 cm), distal margin distance (2.8 ± 0.9 cm vs 2.6 ± 0.8 cm), TNM staging distribution, and tumor differentiation degree (P > 0.05). The TaTME group had a higher proportion of patients who had complete TME in the rectal mesentery integrity TME grading (89.4% vs 77.8%, P = 0.048). The positive lymph node count was not significantly different between the groups (2.3 ± 2.1 vs 2.7 ± 2.4, P = 0.312). The vascular invasion positive rates were 33.3% (22/66) and 38.9% (28/72) (P = 0.477), and the neural invasion positive rates were 18.2% (12/66) and 23.6% (17/72), respectively (P = 0.424). The proportions of patients with pathological stage pT3 were 72.7% (48/66) in the TaTME group and 75.0% (54/72) in the LaTME group (P = 0.748), and the R0 resection rate was 100% in both groups. The tumor regression grade (TRG) in patients receiving neoadjuvant treatment showed a good response rate (TRG 0 and 1) of 68.4% (13/19) in the TaTME group, which was higher than the 52.2% (12/23) in the LaTME group, but not showing a significance difference (P = 0.278).

The TaTME group demonstrated superior pathological outcomes with significantly lower CRM-positive rate (4.5% vs 13.9%, P = 0.032), higher lymph node harvest (17.8 ± 4.6 vs 15.2 ± 4.1, P = 0.001), and improved complete TME rate (89.4% vs 77.8%, P = 0.048) than the LaTME group. These findings indicate that the transanal approach provides better oncological quality with enhanced precision in mesorectal dissection and more thorough lymphadenectomy while maintaining comparable rates of vascular invasion between the two surgical techniques (Figure 1B).

The time to first flatus was significantly earlier in the TaTME group than in the LaTME group (2.1 ± 0.8 days vs 2.8 ± 1.2 days, P = 0.001). The time to the first bowel movement was also significantly earlier in the TaTME group than in the LaTME group (3.4 ± 1.1 days vs 4.2 ± 1.5 days, P = 0.002). However, no significant between-group difference was found in postoperative diet recovery time (P = 0.156). The postoperative bowel sound recovery time was 18.6 ± 6.3 hours in the TaTME group, significantly earlier than the 24.8 ± 8.7 hours in the LaTME group (P < 0.001), and the times to first liquid diet were 1.8 ± 0.6 days and 2.2 ± 0.9 days, respectively (P = 0.003). The nasogastric tube removal time was 1.2 ± 0.4 days in the TaTME group and 1.6 ± 0.7 days in the LaTME group (P = 0.001). The incidence of postoperative abdominal distension was 12.1% (8/66) in the TaTME group vs 25.0% (18/72) in the LaTME group (P = 0.05). The rates of po

The TaTME group demonstrated significantly faster gastrointestinal recovery with shorter times to first flatus (2.1 ± 0.8 days vs 2.8 ± 1.2 days, P = 0.001), first bowel movement (3.4 ± 1.1 days vs 4.2 ± 1.5 days, P = 0.002), first liquid diet (1.8 ± 0.6 days vs 2.2 ± 0.9 days, P = 0.003), and nasogastric tube removal (1.2 ± 0.4 days vs 1.6 ± 0.7 days, P = 0.001) than the LaTME group. These findings indicate that the transanal approach promotes enhanced postoperative recovery of gastrointestinal function, contributing to faster patient rehabilitation and potentially shorter hospital stays. TaTME was associated with accelerated gastrointestinal recovery, which translated into shorter postoperative hospital stays (7.8 ± 2.1 days vs 9.4 ± 2.8 days; mean difference 1.6 days, 95%CI: 0.7-2.5, P = 0.001) and a trend toward fewer 30-day readmissions [2/66 (3.0%) vs 7/72 (9.7%), P = 0.176; Figure 1C].

On postoperative day 1, TNF-α, IL-2, and IL-6 levels were high in both groups; however, the TaTME group had a smaller increase. On postoperative day 2, the TNF-α level was significantly lower in the TaTME group than in the LaTME group (28.4 ± 8.2 pg/mL vs 35.7 ± 1 0.3 pg/mL, P = 0.001), and IL-6 level was also significantly lower (42.6 ± 12.8 pg/mL vs 56.3 ± 15.7 pg/mL, P < 0.001). On postoperative day 3, the inflammatory indicators of the TaTME group recovered faster and were all significantly lower than those of the LaTME group (P < 0.05). On postoperative day 1, the IL-2 levels were 18.7 ± 5.4 pg/mL in the TaTME group and 22.3 ± 7.1 pg/mL in the LaTME group (P = 0.003). The C-reactive protein (CRP) peak was significantly lower in the TaTME group (68.4 ± 18.2 mg/L vs 89.7 ± 24.6 mg/L, P < 0.001). The white blood cell (WBC) count peaks were 11.2 × 109/L ± 2.8 × 109/L in the TaTME group and 13.6 × 109/L ± 3.4 × 109/L in the LaTME group (P < 0.001). Among postoperative day 3 indicators, the TaTME and LaTME groups recorded TNF-α levels of 15.2 ± 4.8 pg/mL and 21.7 ± 6.9 pg/mL (P < 0.001), IL-6 levels of 22.4 ± 7.3 pg/mL and 32.8 ± 10.5 pg/mL (P < 0.001), and IL-2 levels of 12.3 ± 3.7 pg/mL and 16.8 ± 5.2 pg/mL (P < 0.001), respectively. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate recovery to normal time was 5.2 ± 1.6 days in the TaTME group, which was significantly shorter than the 7.8 ± 2.4 days in the LaTME group (P < 0.001).

This comprehensive comparison demonstrates that the TaTME group exhibited significantly lower postoperative inflammatory cytokine levels (TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-2) and reduced inflammatory markers (CRP and WBC count) than the LaTME group across multiple time points, with significance indicated by asterisks. The inflammatory marker assessment has potential clinical utility. Postoperative day 2 IL-6 levels ≥ 50 pg/mL identified patients at risk for poor anal function [odds ratio (OR) = 3.186, P = 0.008], suggesting that early inflammatory profiling could guide intensified rehabilitation protocols, including targeted pelvic floor physiotherapy and biofeedback training. Furthermore, persistently elevated inflammatory markers may warrant closer surveillance for complications, enabling early intervention. The TaTME approach also showed faster recovery with shorter inflammatory marker normalization times and lower inflammatory burden on postoperative day 3, suggesting that the transanal surgical technique is associated with reduced tissue trauma and enhanced postoperative recovery compared with conventional laparoscopic surgery (Figure 1D).

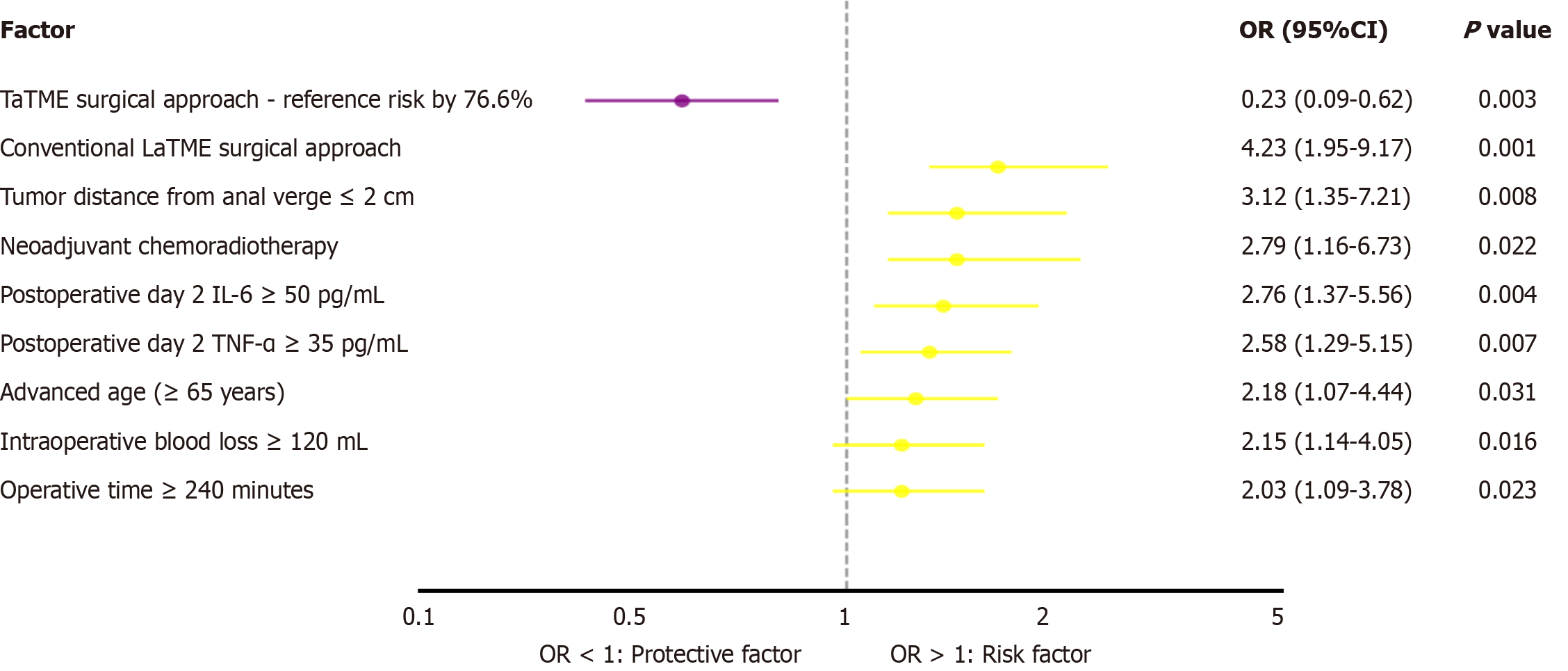

Univariate analysis of poor anal function at 3 months postoperatively (Wexner score > 10 points) showed that age ≥ 65 years (P = 0.031), tumor distance from the anal verge ≤ 2 cm (P = 0.008), neoadjuvant radiochemotherapy (P = 0.045), operative time ≥ 240 minutes (P = 0.023), intraoperative blood loss ≥ 120 mL (P = 0.016), postoperative day 2 IL-6 ≥ 50 pg/mL (P = 0.004), postoperative day 2 TNF-α ≥ 35 pg/mL (P = 0.007), and traditional LaTME surgical approach (P < 0.001) were risk factors for poor anal function. Multivariate analysis showed that TaTME was an independent protective factor for good postoperative anal function (OR = 0.234; 95%CI: 0.089-0.615, P = 0.003), whereas tumor distance from the anal verge ≤ 2 cm (OR = 4.567; 95%CI: 1.892-11.023, P = 0.001), postoperative day 2 IL-6 ≥ 50 pg/mL (OR = 3.186; 95%CI: 1.345-7.548, P = 0.008), and neoadjuvant radiochemotherapy (OR = 2.789; 95%CI: 1.156-6.734, P = 0.022) were independent risk factors for poor anal function. Subgroup analysis showed that in patients with tumor distance from anal verge ≤ 3 cm, the proportion of patients with no-LARS symptoms in the TaTME group at 3 months postoperatively was 71.4% (25/35), which was significantly higher than the 52.5% (21/40) in the LaTME group (P = 0.026). Predictive model construction showed that the model containing the surgical approach, tumor location, and postoperative inflammatory indicators had good predictive performance for poor anal function (area under the curve = 0.782; 95%CI: 0.698-0.866).

This forest plot demonstrates that TaTME serves as a significant protective factor against poor anal function at 3 months postoperatively (OR = 0.23; 95%CI: 0.09-0.62, P = 0.003), reducing the risk by 76.6% compared with conventional LaTME, which represents the highest risk factor (OR = 4.23; 95%CI: 1.95-9.17, P < 0.001). The analysis also identified several independent risk factors, including tumor distance from anal verge ≤ 2 cm, neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy, high postoperative inflammatory markers (IL-6 and TNF-α), advanced age, excessive intraoperative blood loss, and prolonged operative time, all of which significantly increase the likelihood of anal dysfunction following rectal cancer surgery (Figure 2).

Rectal cancer, the third most common malignant tumor globally, has shown a continuous upward trend in incidence over the past two decades, particularly in developed countries and rapidly developing economic regions. This trend is closely related to multiple factors, such as population aging, lifestyle changes, and westernization of dietary patterns. The treatment strategy for rectal cancer has undergone major transformations from palliative to radical treatment and from traditional open surgery to minimally invasive procedures, with each technological advancement bringing better quality of life and prognosis for patients.

TME, as a milestone technique in the surgical treatment of rectal cancer, centers on complete mesenteric excision along the anatomical planes formed during embryonic development, maximally clearing tumors and their potential micrometastases[17,18]. The introduction of this concept has completely transformed the surgical philosophy for rectal cancer, reducing local recurrence rates from 25%-40% with traditional surgery to 5%-10%, significantly improving patients’ long-term survival rates. TME requires not only technical precision but also a deep understanding of pelvic anatomical structures, particularly accurate grasp of fascial layers around the rectum, vascular distribution, and nerve pathways[19,20].

With the vigorous development of minimally invasive surgical techniques, laparoscopic technology has gradually been applied to rectal cancer surgery. LaTME combines the oncological principles of traditional open TME with minimally invasive technology, ensuring surgical radicality while reducing surgical trauma[21,22]. The magnified laparoscopic view allows surgeons to more clearly identify anatomical layers, and precise instrument manipulation reduces damage to surrounding tissues, thereby decreasing intraoperative blood loss, shortening recovery time, and reducing postoperative pain. These advantages have led to the wide adoption of LaTME, becoming one of the standard surgical procedures for rectal cancer treatment[23-25].

However, LaTME has also exposed some inherent limitations in its clinical application. First, this technique has a relatively long learning curve, requiring surgeons to have extensive laparoscopic operative experience and deep understanding of the pelvic anatomy[26,27]. For beginners, mastering this technique often requires completing 50-100 cases to reach a stable level. Second, purely transabdominal LaTME faces significant technical challenges for certain special patient populations, such as patients with obesity, patients with a narrow pelvis, and male patients with prostatic hypertrophy. In these cases, the narrow pelvic space limits laparoscopic instrument manipulation, making exposure of the distal rectal surgical field challenging, potentially leading to prolonged operative time, increased blood loss, and even affecting surgical radicality[28].

LaTME has inherent technical difficulties when dealing with low rectal cancer. Owing to the need for top-down layer-by-layer separation of the rectal mesentery, when the tumor location is too low, surgeons often find it challenging to obtain ideal surgical field exposure; specifically, fine operations around the lower rectum and anal canal become extremely difficult. The adequacy of distal and circumferential margins may be affected in such situations, increasing the risk of local recurrence. Protection of pelvic autonomic nerves also becomes more challenging, potentially affecting patients’ postoperative sexual and urinary function[29].

Based on these technical challenges and clinical needs, TaTME has been employed. The core innovation of TaTME lies in changing the traditional surgical approach, adopting a transanal bottom-up operative method, thereby gaining unique advantages in low rectal cancer treatment. This “bottom-up” surgical concept not only solves the technical problems of traditional LaTME in low rectal cancer treatment but also provides surgeons with a new surgical perspective and operative space[30].

The theoretical advantages of TaTME are mainly reflected in several aspects. First, after rectal insufflation, the transanal approach can obtain clear and magnified surgical fields, making the boundaries between the tumor and surrounding normal tissues clearer and facilitating precise tumor excision. Second, this approach makes distal rectal mesentery mobilization and excision more convenient, particularly for lower rectal cancers, thereby ensuring negative CRMs. Additionally, the transanal approach can better protect pelvic autonomic nerves, thereby reducing the occurrence of postoperative functional disorders[31].

From a surgical technical perspective, TaTME can be divided into pure transanal and laparoscopic-assisted modes. Although the pure transanal technique is technically feasible, it carries theoretical risks of tumor cell dissemination because it approaches the tumor site first, inhibiting complete assessment of intra-abdominal conditions; thus, its clinical application has gradually decreased. In contrast, laparoscopic-assisted TaTME retains the advantages of traditional LaTME while overcoming its deficiencies in low rectal cancer management, representing the mainstream direction of current technological development[32].

Laparoscopic-assisted TaTME typically includes laparoscopic mesenteric vessel management, pelvic lateral lymph node dissection, and transanal rectal mesenteric separation and specimen extraction. This combined approach fully leverages the advantages of both techniques, ensuring oncological safety while improving surgical precision and safety. The dual monitoring mechanism during surgery makes the procedure safer and more controllable, reducing complication occurrence[33].

From the perspective of patient selection, TaTME is particularly suitable for patients with middle-low rectal cancer, particularly those with lower tumor positions and relatively difficult pelvic anatomical conditions. TaTME also shows good applicability for patients who have received neoadjuvant radiochemotherapy, achieving better anatomical layer identification and precise operation in postradiation fibrotic tissues.

Despite TaTME showing numerous theoretical and practical advantages, it still faces some challenges and controversies in clinical application. The first issue is technique standardization and quality control. Given that TaTME is a relatively new technique, surgical skills and quality control may vary among centers and surgeons, which could affect the consistency and reproducibility of surgical results. The second issue is the learning curve. Although TaTME simplifies surgical operations in some aspects, mastering this technique still requires specialized training and accumulation of experience. An important consideration for TaTME adoption is the learning curve. Studies suggest that proficiency in TaTME requires 30-50 cases for experienced laparoscopic surgeons, with outcomes stabilizing after this initial learning phase. In our institution, all TaTME procedures were performed by surgeons who had completed structured training programs and surpassed the learning curve threshold, minimizing potential bias from operator experience.

Furthermore, regarding the long-term oncological safety and functional outcomes of TaTME, large-scale, long-term follow-up evidence-based medicine evidence is still lacking. Although the short-term research results are encouraging, its long-term efficacy and safety still need verification through more high-quality clinical studies. More in-depth com

This study has several limitations. First, the retrospective design and non-randomized treatment allocation introduce potential selection bias. Second, the sample size of 138 patients, while adequate for short-term outcome assessment, limits subgroup analyses. Third, the 3-month follow-up period is insufficient to evaluate long-term oncological outcomes such as local recurrence and overall survival. Future multicenter randomized controlled trials with larger sample sizes and 5-year follow-up are needed to definitively establish TaTME's long-term oncological safety and functional outcomes.

Through a retrospective analysis of 138 patients with rectal cancer, this study systematically compared the short-term efficacy of laparoscopic-assisted TaTME with that of traditional LaTME. The results showed that TaTME demonstrated significant advantages in multiple aspects. These findings provide important evidence-based medicine for the clinical application of TaTME.

Regarding surgical technical indicators, the TaTME group had significantly less intraoperative blood loss than the LaTME group, which may be related to the clear surgical field and precise operation provided by the transanal approach. The surgical space formed after transanal insufflation allows surgeons to more accurately identify vascular structures, thereby reducing unnecessary tissue damage. Meanwhile, the dual-approach surgical method makes vessel management safer and more controllable, thereby reducing the risk of intraoperative bleeding.

The improvement in pathological indicators is clinically significant. The significantly reduced CRM-positive rate in the TaTME group is directly related to patients’ long-term prognosis and risk of local recurrence. Positive CRM is an important predictor of postoperative local recurrence and long-term survival in rectal cancer, and its reduction means improved surgical radicality. Meanwhile, the increased number of lymph nodes harvested in the TaTME group indicates its advantages in lymph node dissection, which is important for accurate tumor staging and formulation of postoperative treatment strategy.

The improvement in postoperative recovery indicators reflects the minimally invasive advantages of TaTME. Shortened gastrointestinal function recovery time, reduced hospital stay, and decreased degree of pain not only improve patient satisfaction but also reduce medical costs. The significant reduction in inflammatory response indicators further confirms the advantages of TaTME in reducing surgical trauma, which may be an important mechanism for promoting rapid postoperative recovery.

Most importantly, the TaTME group had significantly better anal function at 3 months postoperatively than the LaTME group. This finding has important clinical value because protection of anal function directly affects patients’ quality of life. Fine operations through the transanal approach and better protection of pelvic nerve structures are the main reasons for anal function improvement.

This study demonstrates that laparoscopic-assisted TaTME offers superior short-term outcomes in surgical safety, oncological quality, and functional preservation compared to LaTME for mid-to-low rectal cancer.

| 1. | Igaki T, Kitaguchi D, Kojima S, Hasegawa H, Takeshita N, Mori K, Kinugasa Y, Ito M. Artificial Intelligence-Based Total Mesorectal Excision Plane Navigation in Laparoscopic Colorectal Surgery. Dis Colon Rectum. 2022;65:e329-e333. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Mirza MB, Gamboa AC, Irlmeier R, Hopkins B, Regenbogen SE, Hrebinko KA, Holder-Murray J, Wiseman JT, Ejaz A, Wise PE, Ye F, Idrees K, Hawkins AT, Balch GC, Khan A. Association of Surgical Approaches and Outcomes in Total Mesorectal Excision and Margin Status for Rectal Cancer. J Surg Res. 2024;300:494-502. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Park JS, Lee SM, Choi GS, Park SY, Kim HJ, Song SH, Min BS, Kim NK, Kim SH, Lee KY. Comparison of Laparoscopic Versus Robot-Assisted Surgery for Rectal Cancers: The COLRAR Randomized Controlled Trial. Ann Surg. 2023;278:31-38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 33.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Eid Y, Alves A, Lubrano J, Menahem B. Does previous transanal excision for early rectal cancer impair surgical outcomes and pathologic findings of completion total mesorectal excision? Results of a systematic review of the literature. J Visc Surg. 2018;155:445-452. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Lau SYC, Choy KT, Yang TWW, Heriot A, Warrier SK, Guest GD, Kong JC. Defining the learning curve of transanal total mesorectal excision: a systematic review and meta-analysis. ANZ J Surg. 2022;92:355-364. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Teste B, Rullier E. Intraoperative complications during laparoscopic total mesorectal excision. Minerva Surg. 2021;76:332-342. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Yi Chi Z, Gang O, Xiao Li F, Ya L, Zhijun Z, Yong Gang D, Dan R, Xin L, Yang L, Peng Z, Yi L, Dong L, De Chun Z. Laparoscopic total mesorectal excision versus transanal total mesorectal excision for mid and low rectal cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2024;103:e36859. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Liu H, Zeng Z, Zhang H, Wu M, Ma D, Wang Q, Xie M, Xu Q, Ouyang J, Xiao Y, Song Y, Feng B, Xu Q, Wang Y, Zhang Y, Hao Y, Luo S, Zhang X, Yang Z, Peng J, Wu X, Ren D, Huang M, Lan P, Tong W, Ren M, Wang J, Kang L; Chinese Transanal Endoscopic Surgery Collaborative (CTESC) Group. Morbidity, Mortality, and Pathologic Outcomes of Transanal Versus Laparoscopic Total Mesorectal Excision for Rectal Cancer Short-term Outcomes From a Multicenter Randomized Controlled Trial. Ann Surg. 2023;277:1-6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 19.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Sylla P, Sands D, Ricardo A, Bonaccorso A, Polydorides A, Berho M, Marks J, Maykel J, Alavi K, Zaghiyan K, Whiteford M, Mclemore E, Chadi S, Shawki SF, Steele S, Pigazzi A, Albert M, DeBeche-Adams T, Moshier E, Wexner SD. Multicenter phase II trial of transanal total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer: preliminary results. Surg Endosc. 2023;37:9483-9508. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Antoun A, Chau J, Alsharqawi N, Kaneva P, Feldman LS, Mueller CL, Lee L. P338: summarizing measures of proficiency in transanal total mesorectal excision-a systematic review. Surg Endosc. 2021;35:4817-4824. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kong JC, Prabhakaran S, Fraser A, Warrier S, Heriot AG. Predictors of Surgical Difficulty in Laparoscopic Total Mesorectal Excision. Pol Przegl Chir. 2021;93:33-39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Fang J, Wei B, Zheng Z, Xiao J, Han F, Huang M, Xu Q, Wang X, Hong C, Wang G, Ju Y, Su G, Deng H, Zhang J, Li J, Yang X, Chen T, Huang Y, Huang J, Liu J, Wei H; Chinese Postoperative Urogenital Function (PUF) Research Collaboration Group. Preservation versus resection of Denonvilliers' fascia in total mesorectal excision for male rectal cancer: follow-up analysis of the randomized PUF-01 trial. Nat Commun. 2023;14:6667. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Veltcamp Helbach M, Koedam TWA, Knol JJ, Velthuis S, Bonjer HJ, Tuynman JB, Sietses C. Quality of life after rectal cancer surgery: differences between laparoscopic and transanal total mesorectal excision. Surg Endosc. 2019;33:79-87. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Feng Q, Yuan W, Li T, Tang B, Jia B, Zhou Y, Zhang W, Zhao R, Zhang C, Cheng L, Zhang X, Liang F, He G, Wei Y, Xu J; REAL Study Group. Robotic versus laparoscopic surgery for middle and low rectal cancer (REAL): short-term outcomes of a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;7:991-1004. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 379] [Cited by in RCA: 308] [Article Influence: 77.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Chaouch MA, Hussain MI, Carneiro da Costa A, Mazzotta A, Krimi B, Gouader A, Cotte E, Khan J, Oweira H. Robotic versus laparoscopic total mesorectal excision with lateral lymph node dissection for advanced rectal cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2024;19:e0304031. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | de'Angelis N, Marchegiani F, Martínez-Pérez A, Biondi A, Pucciarelli S, Schena CA, Pellino G, Kraft M, van Lieshout AS, Morelli L, Valverde A, Lupinacci RM, Gómez-Abril SA, Persiani R, Tuynman JB, Espin-Basany E, Ris F; European MRI and Rectal Cancer Surgery (EuMaRCS) Study Group. Robotic, transanal, and laparoscopic total mesorectal excision for locally advanced mid/low rectal cancer: European multicentre, propensity score-matched study. BJS Open. 2024;8:zrae044. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Burghgraef TA, Sikkenk DJ, Verheijen PM, Moumni ME, Hompes R, Consten ECJ. The learning curve of laparoscopic, robot-assisted and transanal total mesorectal excisions: a systematic review. Surg Endosc. 2022;36:6337-6360. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Keller DS, Berho M, Perez RO, Wexner SD, Chand M. The multidisciplinary management of rectal cancer. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;17:414-429. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 229] [Article Influence: 38.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Abdelsamad A, Mohammed MK, Serour ASAS, Khalil I, Wesh ZM, Rashidi L, Langenbach MR, Gebauer F, Mohamed KA. Robotic-assisted versus laparoscopic-assisted extended mesorectal excision: a comprehensive meta-analysis and systematic review of perioperative and long-term outcomes. Surg Endosc. 2024;38:6464-6475. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Ihnát P. TaTME (transanal total mesorectal excision) - state of the art. Rozhl Chir. 2021;100:522-526. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Rutgers MLW, Bemelman WA, Khan JS, Hompes R. The role of transanal total mesorectal excision. Surg Oncol. 2022;43:101695. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Grieco M, Marcellinaro R, Russo G, Menditto R, Compalati I, Passafiume F, Carlini M. The role of transanal total mesorectal excision in the treatment of rectal cancer: a systematic review. Minerva Surg. 2023;78:421-432. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Tuan NA, Duc NM, Van Hiep P, Van Sy T, Van Du N, Khuong NT. The Efficacy of Transanal Total Mesorectal Excision: a Preliminary Vietnamese Report. Med Arch. 2020;74:216-223. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | You K, Hwang JA, Sohn DK, Lee DW, Park SS, Han KS, Hong CW, Kim B, Kim BC, Park SC, Oh JH. Exfoliate cancer cell analysis in rectal cancer surgery: comparison of laparoscopic and transanal total mesorectal excision, a pilot study. Ann Coloproctol. 2023;39:502-512. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Aubert M, Mege D, Panis Y. Total mesorectal excision for low and middle rectal cancer: laparoscopic versus transanal approach-a meta-analysis. Surg Endosc. 2020;34:3908-3919. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Škrovina M, Macháčková M, Martínek L, Benčurik V, Dosoudil M, Bartoš J, Anděl P, Hlavíková H. Total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer - laparoscopic versus robotic approach. Rozhl Chir. 2021;100:527-532. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Kagami S, Funahashi K, Koda T, Ushigome T, Kaneko T, Suzuki T, Miura Y, Nagashima Y, Yoshida K, Kurihara A. Transanal down-to-up dissection of the distal rectum as a viable approach to achieve total mesorectal excision in laparoscopic sphincter-preserving surgery for rectal cancer near the anus: a study of short- and long-term outcomes of 123 consecutive patients from a single Japanese institution. World J Surg Oncol. 2022;20:363. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Yoshimitsu K, Mori S, Tanabe K, Wada M, Hamada Y, Yasudome R, Kurahara H, Arigami T, Sasaki K, Koriyama C, Higashi M, Nakajo A, Ohtsuka T. Transanal Total Mesorectal Excision Considering the Embryology Along the Fascia in Rectal Cancer Patients. Anticancer Res. 2023;43:3597-3605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Ryu S, Kitagawa T, Goto K, Nagashima A, Kobayashi T, Shimada J, Ito R, Nakabayashi Y. Transanal Total Mesorectal Excision for Extended Surgery in the Early Stage After Introduction. Anticancer Res. 2023;43:2211-2217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Spinelli A, Foppa C, Carvello M, Sacchi M, De Lucia F, Clerico G, Carrano FM, Maroli A, Montorsi M, Heald RJ. Transanal Transection and Single-Stapled Anastomosis (TTSS): A comparison of anastomotic leak rates with the double-stapled technique and with transanal total mesorectal excision (TaTME) for rectal cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2021;47:3123-3129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Serra-Aracil X, Zarate A, Bargalló J, Gonzalez A, Serracant A, Roura J, Delgado S, Mora-López L; Ta-LaTME study Group. Transanal versus laparoscopic total mesorectal excision for mid and low rectal cancer (Ta-LaTME study): multicentre, randomized, open-label trial. Br J Surg. 2023;110:150-158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Ourô S, Ferreira M, Roquete P, Maio R. Transanal versus laparoscopic total mesorectal excision: a comparative study of long-term oncological outcomes. Tech Coloproctol. 2022;26:279-290. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Deijen CL, Velthuis S, Tsai A, Mavroveli S, de Lange-de Klerk ES, Sietses C, Tuynman JB, Lacy AM, Hanna GB, Bonjer HJ. COLOR III: a multicentre randomised clinical trial comparing transanal TME versus laparoscopic TME for mid and low rectal cancer. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:3210-3215. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 217] [Cited by in RCA: 268] [Article Influence: 24.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/