Published online Jan 27, 2026. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v18.i1.113350

Revised: September 17, 2025

Accepted: November 10, 2025

Published online: January 27, 2026

Processing time: 145 Days and 10.2 Hours

Pancreaticobiliary maljunction (PBM) is a congenital disease in which the pan

To clarify the clinical impact of and risk factors for HL after CBD surgery.

A retrospective study was conducted with 223 CBD patients who underwent EHBR across three tertiary hospitals to investigate postoperative complications. An exploratory analysis was performed to identify factors associated with HL development. Risk factors were subsequently identified using least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) analysis.

HL was observed in 15/223 (6.7%) patients. Two of those patients developed liver failure owing to biliary cirrhosis; one died, and the other received liver transplantation. Two patients required major hepatectomy. The majority of the remaining patients required repeated enteroscopic and/or percutaneous lithotomy procedures. LASSO analysis revealed older age at surgery as an independent risk factor for HL; the time-dependent receiver operating characteristic analysis at 6 years after surgery revealed a cutoff age of 31 years.

HL following CBD surgery has a markedly deleterious clinical impact. Advanced age at the time of CBD surgery was identified as an independent risk factor for HL.

Core Tip: A total of 223 patients with congenital biliary dilatation (CBD) who underwent extrahepatic bile duct resection were retrospectively examined to clarify the clinical impact of hepatolithiasis (HL) that developed after CBD surgery. Among these 223 patients, 15 (6.7%) developed HL. Among these 15 patients, 2 developed biliary cirrhosis: (1) One died of liver failure; and (2) The other required liver transplantation. Two additional patients required major hepatectomy. Most of the remaining 11 patients underwent repeated hospitalization for lithotomy. Statistical analysis revealed that older age at the time of CBD surgery was an independent risk factor for the development of HL.

- Citation: Asano F, Matsuyama R, Kumamoto T, Shinkai M, Morioka D, Shinoda S, Endo I. Clinical characteristics of and risk factors for hepatolithiasis developed after surgery for congenital biliary dilatation. World J Gastrointest Surg 2026; 18(1): 113350

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v18/i1/113350.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v18.i1.113350

Pancreaticobiliary maljunction (PBM) is a rare congenital anatomical disorder that is more prevalent in Asian populations (approximately 1 in 1000 individuals)[1] than in Western populations (approximately 1 in 50000-150000 individuals)[2]. Furthermore, a sex disparity in its incidence is observed, with a male-to-female ratio estimated at approximately 1:3[3]. PBM has the following two subtypes: Congenital biliary dilatation (CBD) and PBM without bile duct dilatation [no

The true long-term pathophysiological characteristics of NDPBM have yet to be clarified, and no existing treatment strategies for NDPBM have reached a global consensus[7]. In contrast, a treatment strategy for CBD is becoming established. This strategy recommends immediate surgery after diagnosis, i.e., extrahepatic bile duct resection (EHBR) with bilioenteric bypass[7].

Patients with either CBD or NDPBM require life-long medical vigilance, as they are likely to develop long-term co

In the present study, we conducted an exploratory examination of 223 CBD patients who underwent EHBR to clarify their clinical characteristics and to identify the risk factors for HL that developed after CBD surgery. As a secondary objective, this study aimed to determine the cutoff value of the risk factor identified in the primary objective.

We retrospectively investigated the clinicopathological variables of the 223 patients who underwent CBD surgery at three collaborating tertiary hospitals: (1) Two university hospitals; and (2) One children’s hospital. The Institutional Review Boards of these three institutions approved this study [No. F241000006 (same in the two university hospitals) and No. C119-2024-92].

From 1983 to 2019, a total of 250 patients underwent surgery for CBD. Of these, 25 patients were excluded because of the diagnosis of BTC at the time of CBD diagnosis or because of other organ malignancies discovered preoperatively or postoperatively. Additionally, two patients who underwent cholecystectomy alone were excluded because the purpose of this study was to identify the risk factors for HL that developed after EHBR. This study included the remaining 223 patients who underwent EHBR. As this was an exploratory study, the sample size was determined from the perspective of feasibility.

CBD was diagnosed when the diameter of the common bile duct was 6 mm or greater in children and 10 mm or greater in adult patients[13]; the morphological types were classified using the Todani classification[14]. We evaluated the following variables: (1) Patient demographics; (2) Todani classification; (3) Short-term and long-term complications; and (4) Clinical outcomes. More detailed clinicopathological features were examined in patients who developed HL postoperatively. Patient follow-up continued until December 2022 or until patient death. Adult patients were defined as patients aged 15 years or older at the time of CBD surgery. Short-term complications were defined as those that developed within 30 days after surgery, whereas long-term complications were defined as those that developed more than 30 days after surgery.

The surgical procedures for CBD were consistent across all three institutions. The CBD surgery consisted of EHBR and Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy. The location of bile duct resection was ultimately decided on the basis of the findings of intraoperative cholangiography and/or preoperative magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP). The proximal side was separated at the common hepatic duct, and the distal side was separated at the intrapancreatic bile duct. The two sides were cut as far apart as possible. However, the proximal duct was divided so as not to form plural orifices; ductoplasty to incise the stenotic area was added to mitigate stenosis in cases where stenotic lesions were observed at the site more proximal to the cut end. The jejunum used for hepaticojejunostomy was mobilized retrocolically. Absorbable sutures were used in all cases. The decision of whether to perform anastomosis using intermittent or continuous suture was left to the surgeon’s preference. A drainage tube was inserted behind the hepaticojejunostomy. Bile cultures were performed according to the decision of the attending surgeon. Laparoscopic surgery was introduced in 2009 for pediatric patients and in 2010 for adults. The surgical approach to bile duct resection and reconstruction was consistent between the open and laparoscopic procedures.

The follow-up, as described below, was conducted at the discretion of the attending physician. For pediatric patients, ultrasonography was performed at intervals ranging from 6 months to 12 months, and MRCP was performed as necessary. For adult patients, blood analysis, including white blood cell count and serum liver enzyme levels, was performed at every outpatient visit at intervals of 6-12 months. Computed tomography (CT) or MRCP was performed at least once a year. Cholangitis was diagnosed on the basis of fever and laboratory findings, including elevated inflammatory markers and abnormal liver function tests. Additionally, CT or magnetic resonance imaging was used as part of the diagnostic process in certain cases. Anastomotic stenosis was defined as focal narrowing at the site of the biliary anastomosis[15], and anastomotic leakage was defined as the persistent presence of bile-colored fluid in the drain or according to the criteria established by the International Study Group of Liver Surgery[16].

The main objective of this study was to identify the risk factors for HL development following CBD surgery. We first performed an exploratory data analysis and extracted the causative factors for HL. Afterward, we used least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) regularization in a Cox proportional hazards model to determine the in

In addition, to evaluate the prediction performance of the factors identified by LASSO, we used time-dependent receiver operating curve (td-ROC) analysis and calculated the area under the curve (AUC) and the cutoff for the Youden index. HL-free survival estimates were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method. The survival curves were compared by the log-rank test.

Binomial confidence intervals were calculated using the Wilson score method without continuity correction. Fisher’s exact test was used to assess categorical variables, whereas the Brunner-Munzel test was used to analyze continuous variables. A two-tailed P value < 0.05 was considered definitively significant. All the statistical analyses were carried out using the free statistical software R version 4.4.1[19].

Patient demographics are shown in Table 1. In brief, 153 (69%) of the patients were women and 70 were men. The median age at the time of CBD surgery was 5.3 years (range from 29 days to 77 years). Among the 223 patients, 164 (74%) were pediatric patients, and 59 were adults. According to the Todani classification, 79 patients (35%) had type Ia disease, 52 (23%) had type Ic disease, and 92 (41%) had type IV-A disease. No patients had undergone biliary surgery prior to CBD surgery. The median body weight of the patients was 15.0 kg (range: 4.0-91.6 kg). Comorbid metabolic diseases were observed in 10 patients (4%). A total of 183 patients (82%) presented with preoperative symptoms, including abdominal pain, vomiting, abdominal tumor, or jaundice. Additionally, 98 patients (44%) had cholecystolithiasis and/or choledocholithiasis prior to undergoing CBD surgery. Intraoperative or postoperative bile culture was performed for 37 patients (17%), of which 32 (86%) yielded negative results. Laparoscopic surgery was performed in 48 pediatric patients (29%) and 4 adult patients (7%).

| Characteristics | Study sample (n = 223) |

| Male/female | 70 (31)/153 (69) |

| Age at surgery (year), median (range) | 5.2 (0.07-77) |

| Child/adult | 164 (74)/59 (26) |

| Todani classification | |

| Ia | 79 (35) |

| Ic | 52 (23) |

| IV-A | 92 (41) |

| Preoperative conditions | |

| Symptoms1 | 183 (82) |

| Stones in bile tract | 98 (44) |

The short-term complications are summarized in Table 2. Among the 223 patients, 42 (19%) experienced short-term complications; 23 (14% of the pediatric patients) were children, and the remaining 19 (32% of the adult patients) were adults. The short-term complications were as follows: (1) Anastomotic bile leakage in 14 patients (33%); (2) Cholangitis in five (12%); (3) Intra-abdominal abscess in four (10%); (4) Pancreatic fistula in three (7%); (5) Bilioenteric anastomotic stenosis in one; and (6) Acute pancreatitis in one.

| Characteristics | Short-term (n = 42) | Long-term (n = 37) | ||

| Child (n = 23) | Adult (n = 19) | Child (n = 12) | Adult (n = 25) | |

| Male/female | 7 (30)/16 (70) | 8 (42)/11 (58) | 3 (25)/9 (75) | 9 (36)/16 (64) |

| Age at surgery (year), median (interquartile range) | 1.9 (4.2) | 45.0 (20.0) | 3.8 (5.9) | 50.0 (31.0) |

| Todani classification | ||||

| Ia | 9 (39) | 5 (26) | 3 (25) | 10 (40) |

| Ic | 4 (17) | 3 (16) | 3 (25) | 4 (16) |

| IV-A | 10 (43) | 11 (58) | 6 (50) | 11 (44) |

| Complications | ||||

| Anastomotic leakage | 11 (48) | 3 (16) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Surgical site infection | 4 (17) | 4 (21) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Acute cholangitis | 1 (4) | 4 (21) | 3 (25) | 23 (92) |

| Delayed gastric emptying | 4 (17) | 1 (5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Intra-abdominal abscess | 1 (4) | 3 (16) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Pancreatic fistula | 1 (4) | 2 (11) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Anastomotic stenosis | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | 1 (8) | 7 (28) |

| Intestinal obstruction | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | 6 (50) | 1 (4) |

| Acute pancreatitis | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | 3 (25) | 2 (8) |

| Hepatolithiasis | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (17) | 13 (52) |

| Pancreatic stones | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (8) |

| Biliary cirrhosis | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (5) |

| Bile tract cancer | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

Six of the 14 patients with bilioenteric anastomotic leakage required surgery; five of the six patients underwent bilioenteric reanastomosis, and the remaining patient recovered following drainage surgery. The other eight patients recovered with conservative treatment alone. Among the five patients with cholangitis, one developed stenosis of the Y-limb jejunojejunostomy, and reanastomosis of the Y-limb successfully resolved the cholangitis. The remaining four patients with cholangitis were relieved by conservative treatment alone.

The long-term complications are summarized in Table 2. The median postoperative observation period for the 223 patients was 10 years (range: 0.3-39 years). Long-term complications occurred in 37 patients (16%), including cholangitis in 23 (62%), HL in 15 (41%), bilioenteric anastomotic stenosis in eight (22%), and biliary cirrhosis in two (5%). Among the 42 patients with short-term complications, 10 experienced long-term complications (23.8%; 95%CI: 13.5%-38.5%, Wilson score interval). Among the 15 patients with HL, five (33%) had previously experienced bilioenteric anastomotic stenosis.

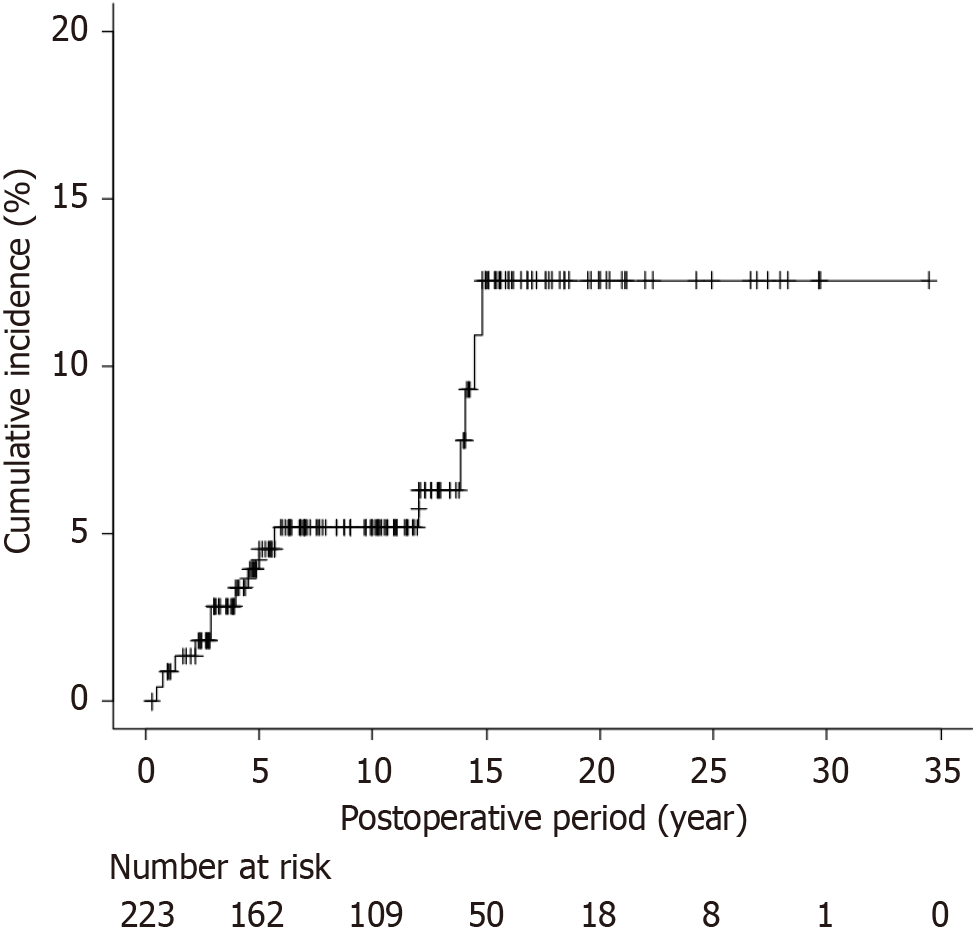

Among the 223 patients, 15 (6.7%) developed HL postoperatively (Table 3). No sex difference was observed, with five males (33%) and ten females (67%) (P = 1.000). The median age at the time of CBD surgery among the 15 patients was 55 years (1.2-67 years). The median age at the diagnosis of HL was 59 years (15-80 years). The median duration from surgery to the diagnosis of HL was 4.5 years (0.5-14.5 years) (Figure 1). The observation period was longer in patients with HL (median 14.5 years) than in those without HL (10.0 years) (P = 0.03). Among the 15 patients, the Todani classification was Ia for five patients, Ic for three, and IV-A for seven. The HL was located in the common hepatic duct in three patients, unilobe in 12 patients, and bilobe in two patients (two patients showed locational overlap). Ten of the 15 patients had major biliary stenosis (bilioenteric anastomotic stenosis or stenosis of the common hepatic duct, right hepatic duct, or left hepatic duct). Three of the 15 patients had stenosis of the second or more proximal bile duct divergence. Two of the 15 patients with HL exhibited no biliary stenosis. In these two patients, intrahepatic stones formed in either the first or second biliary divergence.

| Characteristics | HL (n = 15) | Without HL (n = 208) |

| Male/female | 5 (33)/10 (67) | 65 (31)/143 (69) |

| Todani classification | ||

| Ia | 5 (33) | 74 (36) |

| Ic | 3 (20) | 49 (24) |

| Ia or Ic | 8 (53) | 123 (59) |

| IV-A | 7 (47) | 85 (41) |

| Age at surgery (year), median (IQR) | 55.0 (22.7) | 12.5 (16.7) |

| Child/adult | 2 (13)/13 (87) | 161 (77)/47 (23) |

| Preoperative condition | ||

| Stones in bile tract | 3 (20) | 95 (46) |

| With symptoms | 8 (53) | 175 (84) |

| Postoperative observation period (year), median (IQR) | 14.5 (8.8) | 10.0 (10.0) |

| Postoperative short-term complications | ||

| All | 4 (27) | 38 (18) |

| Anastomotic leakage | 0 (0) | 14 (7) |

| Acute cholangitis | 2 (13) | 3 (1) |

| Anastomotic stenosis | 0 (0) | 1 (0.5) |

| Intra-abdominal abscess | 0 (0) | 4 (2) |

| Pancreatic fistula | 0 (0) | 3 (1) |

| Acute pancreatitis | 0 (0) | 1 (0.5) |

| Clavien-Dindo classification ≥ 3 | 1 (7) | 12 (6) |

| Postoperative long-term complications | ||

| Anastomotic stenosis | 5 (33) | 3 (1) |

| Acute pancreatitis | 0 (0) | 5 (2) |

The initial treatment for HL was enteroscopic lithotomy for seven patients, percutaneous lithotomy for three patients, hepatectomy for two patients, conservative treatment with oral ursodeoxycholic acid alone for two patients, and observation alone for one patient. Eight of the 12 patients who underwent HL removal had recurrent stones. The six patients who did not have recurrent HL included two patients who underwent hepatectomy in which the biliary stenotic lesion was removed and four patients who underwent endoscopic dilatation of the biliary stenosis. Two of the fifteen patients had recurrent stones and developed biliary cirrhosis, which ultimately resulted in liver failure; one patient died of liver failure 14 years after CBD surgery and was the only patient who died during the study period. The other patient required a liver transplant 19 years after CBD surgery.

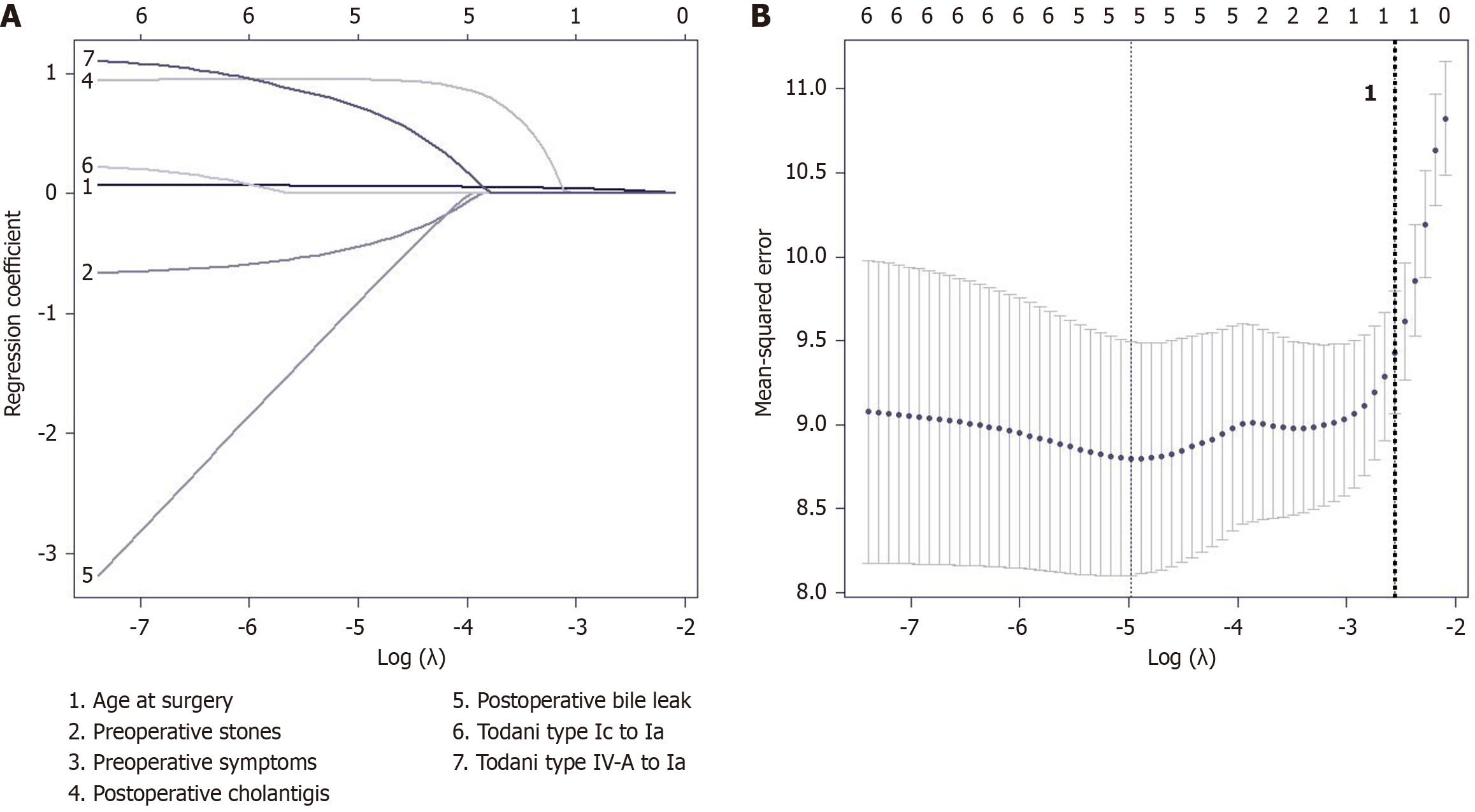

To identify the causative factors of HL, we first performed an exploratory data analysis and extracted six variables: (1) Age at the time of EHBR; (2) Todani classification; (3) Presence of preoperative lithiasis; (4) Preoperative symptoms; (5) Acute cholangitis observed during the short-term postoperative period; and (6) Anastomotic leakage. Reoperation for anastomotic stenosis was not included in the analysis because of the limited number of eligible patients. LASSO regularization, which included these six variables, identified age at the time of EHBR as the sole independent causative factor for postoperative HL, and Todani type was not retained in the final selection (Figure 2). Employing tenfold cross-validation yielded a hazard ratio of 1.028 for age at the time of EHBR (Table 4). The events per variable (EPV) was 2.5.

| Variables | Hazard ratio | 95%CI |

| Age at surgery | 1.028 | 1.0-1.0448 |

| Todani type Ic | 1.0 | 1.0-1.0000 |

| Todani type IV-A | 1.0 | 1.0-1.0000 |

| Preoperative conditions | ||

| Stones in bile tract | 1.0 | 1.0-1.0000 |

| Symptoms | 1.0 | 1.0-1.0000 |

| Short-term complications | ||

| Acute cholangitis | 1.0 | 1.0-5.8948 |

| Anastomotic leakage | 1.0 | 1.0-1.0000 |

The observation period was relatively long; therefore, cases of HL were categorized on the basis of the timing of surgery (i.e., before and after the year 2000) and the type of surgical technique performed (open or laparoscopic). HL occurred in nine patients (6.2%) before 2000 and in six patients (7.7%) after 2000. With respect to surgical technique, all HL cases were observed following open surgery; no cases were reported after laparoscopic surgery.

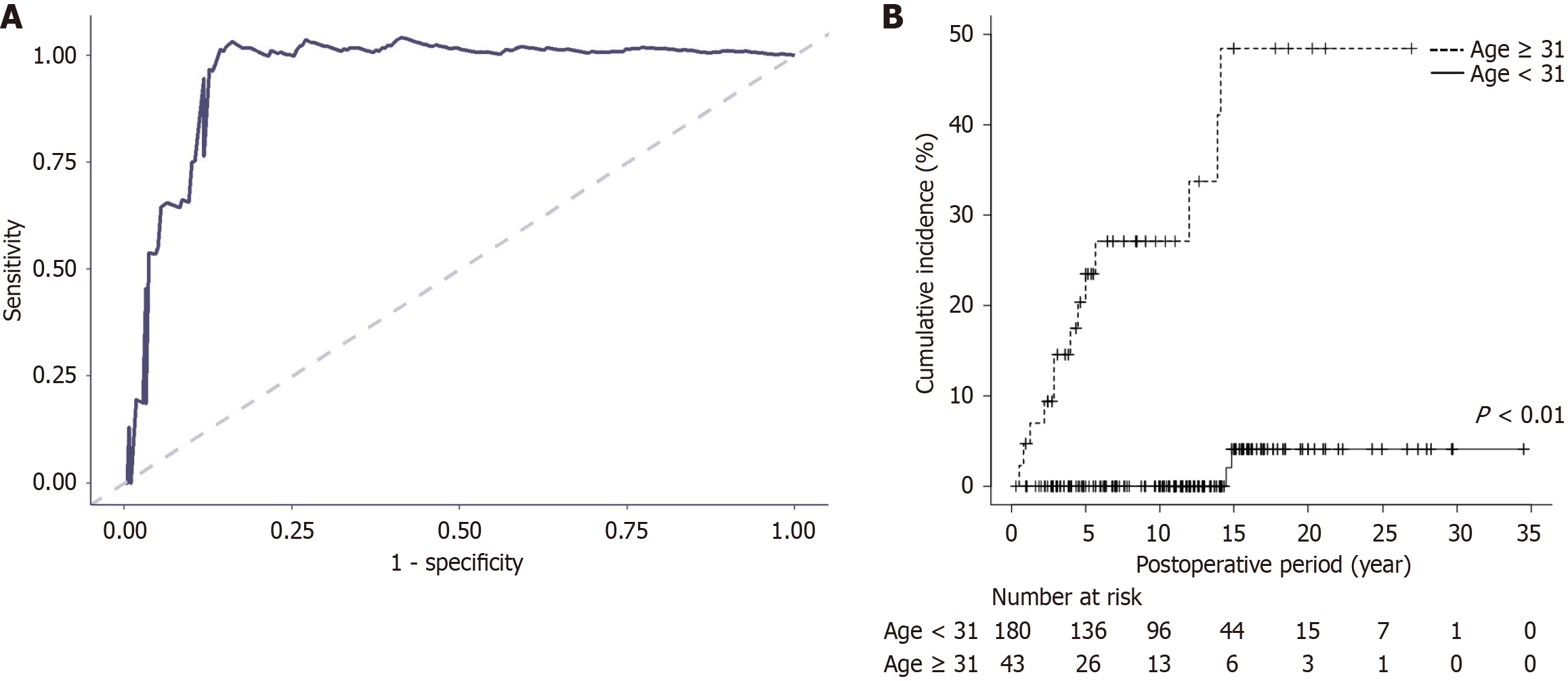

The td-ROC curve at 6 years after CBD surgery was used to evaluate the ability of the patients’ age at surgery to predict their risk of developing HL. The td-ROC curve revealed 31 years of age at the time of surgery as the optimal cutoff value on the basis of the Youden index, with an AUC of 0.935 (Figure 3A). A comparison of the cumulative incidence of HL between patients who underwent CBD surgery at age 31 or older and those younger than 31 years revealed a significant difference: The 20-year cumulative incidence rate was 50% in the older group and 5% in the younger group (P < 0.01; Figure 3B). The Brunner-Munzel test revealed that the observation period following CBD surgery was not significantly different between the two groups (8.4 years in the older group vs 10.3 years in the younger group, P = 0.832). These findings suggest that patients who are older at the time of CBD surgery are more susceptible to developing HL than younger patients are.

This study demonstrated the deleterious clinical impact of HL on the long-term postoperative course after CBD surgery. The worst clinical outcomes observed among the 223 patients who underwent CBD surgery in this study were death owing to liver failure caused by persistent cholangitis and the need for liver transplantation. These two patients had the most unfavorable clinical progression, which was attributed to biliary cirrhosis resulting from HL. Therefore, HL can be considered a contributing factor to this unfavorable outcome. Moreover, even among patients who survived HL, the majority required repeated treatments. In other words, the clinical course of HL patients in this study confirmed that HL after CBD surgery is not only significantly life-threatening, but also a critical factor impairing patients’ quality of life.

This study aimed to explore risk factors for HL but identified a limited number of events. Since LASSO is designed to prevent overfitting even with smaller EPV values, we chose to use LASSO for the analysis in this study. The LASSO findings, which indicate that advanced age at CBD surgery is an independent risk factor for HL, are not supported by clinical evidence. However, several basic studies have suggested that older patients who undergo CBD surgery are more susceptible to HL. Duch et al[20] demonstrated that the function of the bile duct wall was impaired by cholestasis in a pig obstructive jaundice model. The duration of cholestasis was correlated with the degree of bile duct elasticity reduction and the thickness of the bile duct wall. Moreover, thickening of the bile duct wall was caused by the proliferation of collagenous tissue that lacks contractility, thereby impairing the peristalsis of the bile duct. These findings suggest that once the bile duct develops cholestasis, the function of the bile duct wall is impaired, leading to sustained cholestasis[21]. In addition, in a pig cholestasis model, Dang et al[22] found that the function of the bile duct wall impaired by cholestasis was more likely to recover in individuals with a short duration of cholestasis than in those with a long duration of cholestasis. Reflecting the results of these studies, our findings revealed that CBD was almost always accompanied by cholestasis, that the function of the remnant bile duct was more likely to recover in patients who underwent surgery at a younger age than in those who underwent surgery at an older age, and that persistent cholestasis may be more likely to remain in older patients, increasing their susceptibility to HL.

In clinical practice, early surgery may prevent HL. Regular health checkups using ultrasound for individuals in their 20s, for example, may facilitate early diagnosis of CBD. However, an age of 31 years at the time of surgery is specifically predictive within the first six postoperative years, and moreover, only 19% of CBD patients were diagnosed at age 31 or older. Therefore, implementing early surgery to prevent HL is impractical at present. Nonetheless, early diagnosis of HL remains achievable. Given the elevated risk of BTC in CBD patients, lifelong vigilance is essential[23,24]. Nevertheless, postoperative follow-up may unintentionally be discontinued during the long observation period. This study suggests that early diagnosis can improve clinical outcomes for patients with HL. Therefore, life-long medical vigilance at ap

We acknowledge several limitations in this study. First, this study examined a patient cohort over a considerably long period of 36 years. During this extended period, there have been substantial changes in the diagnostic methods for CBD and in the definition of complications. Furthermore, diagnostic modalities, surgical techniques, and patient management have undoubtedly been refined. Consequently, surgical outcomes may have varied between earlier and later cases. This variation could affect the generalizability of the present study. Second, only 15 patients developed HL. The results of the statistical analyses may therefore have limited generalizability. Third, the present study was retrospective in nature. Therefore, unavoidable bias in the study variables may affect the findings. Fourth, the follow-up protocols in this study differed between pediatric and adult patients. The protocols were, however, comparable to those described in the literature[32,33]. This heterogeneity may have contributed to differences in the diagnosis and detection rate of HL. In future studies, MRCP-based postoperative follow-up may be warranted for both pediatric and adult patients. Fifth, some of the censored cases in this study were due to unknown reasons, which may suggest the presence of competing-risk bias. Despite these limitations, however, this study is the first to demonstrate the clinical significance of HL that develops after CBD surgery, as well as the independent risk factors for HL. We believe that the findings will have a beneficial effect on the future management and treatment of CBD.

In conclusion, HL developed after CBD surgery in 6.7% of the patients and had a deleterious effect on their clinical course. Statistical analysis revealed that advanced age at the time of surgery is an independent risk factor for HL. Early surgical intervention for younger CBD patients is needed to prevent the development of HL as well as BTC. In other words, early diagnosis of CBD is critical for performing CBD surgery on younger patients. Moreover, early detection of HL after CBD surgery is an effective measure for improving the clinical outcome of patients with HL following surgery. For this purpose, life-long follow-up at appropriate intervals is necessary. The establishment of a supportive social system is indispensable for achieving these goals.

| 1. | Miyano T, Yamataka A. Choledochal cysts. Curr Opin Pediatr. 1997;9:283-288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Lenriot JP, Gigot JF, Ségol P, Fagniez PL, Fingerhut A, Adloff M. Bile duct cysts in adults: a multi-institutional retrospective study. French Associations for Surgical Research. Ann Surg. 1998;228:159-166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kamisawa T, Kaneko K, Itoi T, Ando H. Pancreaticobiliary maljunction and congenital biliary dilatation. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;2:610-618. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Ono Y, Kaneko K, Tainaka T, Sumida W, Ando H. Pancreaticobiliary maljunction without bile duct dilatation in children: distinction from choledochal cyst. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2008;46:555-560. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kamisawa T, Ando H, Suyama M, Shimada M, Morine Y, Shimada H; Working Committee of Clinical Practice Guidelines for Pancreaticobiliary Maljunction; Japanese Study Group on Pancreaticobiliary Maljunction. Japanese clinical practice guidelines for pancreaticobiliary maljunction. J Gastroenterol. 2012;47:731-759. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 143] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Morine Y, Shimada M, Takamatsu H, Araida T, Endo I, Kubota M, Toki A, Noda T, Matsumura T, Miyakawa S, Ishibashi H, Kamisawa T, Shimada H. Clinical features of pancreaticobiliary maljunction: update analysis of 2nd Japan-nationwide survey. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2013;20:472-480. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ishibashi H, Shimada M, Kamisawa T, Fujii H, Hamada Y, Kubota M, Urushihara N, Endo I, Nio M, Taguchi T, Ando H; Japanese Study Group on Congenital Biliary Dilatation (JSCBD). Japanese clinical practice guidelines for congenital biliary dilatation. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2017;24:1-16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | de Kleine RH, Ten Hove A, Hulscher JBF. Long-term morbidity and follow-up after choledochal malformation surgery; A plea for a quality of life study. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2020;29:150942. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Takeshita N, Ota T, Yamamoto M. Forty-year experience with flow-diversion surgery for patients with congenital choledochal cysts with pancreaticobiliary maljunction at a single institution. Ann Surg. 2011;254:1050-1053. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Urushihara N, Fukumoto K, Fukuzawa H, Mitsunaga M, Watanabe K, Aoba T, Yamoto M, Miyake H. Long-term outcomes after excision of choledochal cysts in a single institution: operative procedures and late complications. J Pediatr Surg. 2012;47:2169-2174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Amano H, Shirota C, Tainaka T, Sumida W, Yokota K, Makita S, Takimoto A, Tanaka Y, Hinoki A, Kawashima H, Uchida H. Late postoperative complications of congenital biliary dilatation in pediatric patients: a single-center experience of managing complications for over 20 years. Surg Today. 2021;51:1488-1495. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ohtsuka H, Fukase K, Yoshida H, Motoi F, Hayashi H, Morikawa T, Okada T, Nakagawa K, Naitoh T, Katayose Y, Unno M. Long-term outcomes after extrahepatic excision of congenital choladocal cysts: 30 years of experience at a single center. Hepatogastroenterology. 2015;62:1-5. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Sakaguchi T, Suzuki S, Suzuki A, Fukumoto K, Jindo O, Ota S, Inaba K, Kikuyama M, Nakamura S, Konno H. Late postoperative complications in patients with pancreaticobiliary maljunction. Hepatogastroenterology. 2007;54:585-589. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Todani T, Watanabe Y, Toki A, Morotomi Y. Classification of congenital biliary cystic disease: special reference to type Ic and IVA cysts with primary ductal stricture. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2003;10:340-344. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 137] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 15. | Verdonk RC, Buis CI, Porte RJ, van der Jagt EJ, Limburg AJ, van den Berg AP, Slooff MJ, Peeters PM, de Jong KP, Kleibeuker JH, Haagsma EB. Anastomotic biliary strictures after liver transplantation: causes and consequences. Liver Transpl. 2006;12:726-735. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 214] [Cited by in RCA: 243] [Article Influence: 12.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Tanaka Y, Tainaka T, Hinoki A, Shirota C, Sumida W, Yokota K, Oshima K, Makita S, Amano H, Takimoto A, Kano Y, Uchida H. Risk factors and outcomes of bile leak after laparoscopic surgery for congenital biliary dilatation. Pediatr Surg Int. 2021;37:235-240. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Tibshirani R. Regression Shrinkage and Selection Via the Lasso. J R Stat Soc Series B Stat Methodol. 1996;58:267-288. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8558] [Cited by in RCA: 7072] [Article Influence: 884.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Pavlou M, Ambler G, Seaman S, De Iorio M, Omar RZ. Review and evaluation of penalised regression methods for risk prediction in low-dimensional data with few events. Stat Med. 2016;35:1159-1177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 198] [Cited by in RCA: 251] [Article Influence: 25.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | The R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. 2024. Available from: https://www.R-project.org. |

| 20. | Duch BU, Andersen HL, Smith J, Kassab GS, Gregersen H. Structural and mechanical remodelling of the common bile duct after obstruction. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2002;14:111-122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Duch BU, Andersen H, Gregersen H. Morphometric and biomechanical remodelling following reopening of the obstructed bile duct. Physiol Meas. 2003;24:N23-N34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Dang Q, Gregersen H, Duch B, Kassab GS. Indicial response functions of growth and remodeling of common bile duct postobstruction. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2004;286:G420-G427. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Ono S, Fumino S, Shimadera S, Iwai N. Long-term outcomes after hepaticojejunostomy for choledochal cyst: a 10- to 27-year follow-up. J Pediatr Surg. 2010;45:376-378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Ohashi T, Wakai T, Kubota M, Matsuda Y, Arai Y, Ohyama T, Nakaya K, Okuyama N, Sakata J, Shirai Y, Ajioka Y. Risk of subsequent biliary malignancy in patients undergoing cyst excision for congenital choledochal cysts. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;28:243-247. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Aspelund G, Mahdi EM, Rothstein DH, Wakeman DS; American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Surgery's Delivery of Surgical Care Committee. Transitional care for patients with surgical pediatric hepatobiliary disease: Choledochal cysts and biliary atresia. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;34:966-974. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Cullis PS, Fouad D, Goldstein AM, Wong KKY, Boonthai A, Lobos P, Pakarinen MP, Losty PD. Major surgical conditions of childhood and their lifelong implications: comprehensive review. BJS Open. 2024;8:zrae028. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Uecker M, Ure B, Quitmann JH, Dingemann J. Need for transition medicine in pediatric surgery - health related quality of life in adolescents and young adults with congenital malformations. Innov Surg Sci. 2021;6:151-160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Kabeya Y, Goto A, Hayashino Y, Suzuki H, Furukawa TA, Yamazaki K, Izumi K, Noda M. Psychological and Situational Factors Affecting Dropout from Regular Visits in Diabetes Practice: The Japan Diabetes Outcome Intervention Trial-2 Large Scale Trial 004 (J-DOIT2-LT004). JMA J. 2022;5:427-437. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Koea J, O'Grady M, Agraval J, Srinivasa S. Defining an optimal surveillance strategy for patients following choledochal cyst resection: results of a systematic review. ANZ J Surg. 2022;92:1356-1364. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Ueno T, Deguchi K, Masahata K, Nomura M, Watanabe M, Kamiyama M, Tazuke Y, Yoshioka T, Nose S, Okuyama H. Treatment and follow-up of late onset intra hepatic bile duct stones in congenital biliary dilatation. Pediatr Surg Int. 2022;39:20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Shirota C, Kawashima H, Tainaka T, Sumida W, Yokota K, Makita S, Amano H, Takimoto A, Hinoki A, Uchida H. Double-balloon endoscopic retrograde cholangiography can make a reliable diagnosis and good prognosis for postoperative complications of congenital biliary dilatation. Sci Rep. 2021;11:11052. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Madadi-Sanjani O, Wirth TC, Kuebler JF, Petersen C, Ure BM. Choledochal Cyst and Malignancy: A Plea for Lifelong Follow-Up. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2019;29:143-149. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Aota T, Kubo S, Takemura S, Tanaka S, Amano R, Kimura K, Yamazoe S, Shinkawa H, Ohira G, Shibata T, Horiike M. Long-term outcomes after biliary diversion operation for pancreaticobiliary maljunction in adult patients. Ann Gastroenterol Surg. 2019;3:217-223. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/