Published online Feb 15, 2026. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v17.i2.112856

Revised: October 16, 2025

Accepted: December 23, 2025

Published online: February 15, 2026

Processing time: 171 Days and 1 Hours

Diabetes is linked to extended hospitalization and a heightened risk of complications in multiple surgical settings. However, its precise influence on outcomes in patients undergoing meningioma resection is still inadequately comprehended.

To determine if diabetes prolongs hospital stay and elevates the risk of infection, cerebral edema, and neurological complications in patients undergoing menin

A retrospective study was conducted on 516 primary meningioma patients who underwent surgical resection between January 2018 and January 2022. Patients were categorized into non-diabetes (n = 411) and diabetes (n = 105) groups according to a clinical history of type 2 diabetes for a minimum of 6 months preceding diagnosis. The collected data encompassed baseline demographics, perioperative variables, blood glucose levels, inflammatory markers, brain edema grading, Karnofsky Performance Status, length of stay, and postoperative com

Significant differences in glycated hemoglobin levels were observed, with elevated values in the diabetes group (P < 0.05). The diabetes group exhibited higher rates of secondary or tertiary wound healing complications due to infection, lower postoperative albumin, higher postoperative platelet counts, white blood cell counts, C-reactive protein levels, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha levels (all P < 0.05). The diabetes group exhibited higher incidence of postoperative cerebral edema (P = 0.015), lower postoperative Karnofsky Performance Status scores (P = 0.011), longer hospital stays (P < 0.001), and longer intensive care unit stays (P < 0.001). Additionally, the diabetes group exhibited higher rates of seizures (P = 0.003) and wound infections (P < 0.001) and more complications (P < 0.001). Long-term outcomes showed higher tumor recurrence (P = 0.004) and mortality rates (P = 0.036) in the diabetes group, corroborated by Cox regression analysis as independent risk factors (recurrence: Adjusted hazard ratio = 8.92, P = 0.009; mortality: Adjusted hazard ratio = 10.12, P = 0.048).

Diabetes markedly extends hospital stay and elevates the risk of infection, cerebral edema, and neurological complications in patients with meningioma, underscoring the necessity for meticulous perioperative management and long-term follow-up for diabetic individuals undergoing meningioma surgery.

Core Tip: This retrospective study suggests that diabetes may be a significant modifier of recovery after meningioma surgery. Our findings indicate that patients with diabetes mellitus (DM) experienced higher rates of surgical site infection, clinically significant cerebral edema requiring intervention, prolonged hospitalization, and poorer long-term functional status. Furthermore, DM was associated with an increased risk of tumor recurrence and mortality in time-to-event analysis, suggesting a potential independent association. These results highlight the potential importance of recognizing DM as a key comorbidity that warrants careful perioperative management and vigilant long-term follow-up in this patient population.

- Citation: Zhang YF, Ma W, Chen L, Sun SK, Gao L. Diabetes prolongs hospitalization and increases infection, cerebral edema, and neurological complications in meningioma patients: A retrospective study. World J Diabetes 2026; 17(2): 112856

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9358/full/v17/i2/112856.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4239/wjd.v17.i2.112856

Meningiomas represent the most prevalent primary brain tumors, accounting for approximately one-third of all central nervous system neoplasms[1,2]. These tumors usually originate from the arachnoid cap cells and are predominantly benign, although they can lead to considerable morbidity because of their location and size[3]. Surgical resection is the principal treatment approach for symptomatic meningiomas, focusing on complete removal while reducing neurological deficits[4]. Postoperative complications, including infection, cerebral edema, and neurological deficits, pose a considerable concern because they affect patient outcomes, especially in individuals with comorbidities, such as diabetes[5].

Diabetes is a chronic metabolic condition marked by hyperglycemia due to impairments in insulin secretion, action, or both[6]. It affects over 400 million individuals worldwide and is linked to various systemic complications, including cardiovascular disease, nephropathy, and neuropathy[7]. In neurosurgical contexts, diabetes has been linked to impaired wound healing, increased susceptibility to infections, and altered inflammatory responses, all of which may affect outcomes in patients with meningioma[8]. Hyperglycemia results in the production of advanced glycation end-products (AGEs), which disrupt collagen synthesis and cross-linking and thereby undermine wound integrity[9]. Additionally, hyperglycemia exacerbates oxidative stress and inflammation, hindering the healing process[10]. Diabetic patients demonstrate diminished immune function, which is marked by impaired neutrophil chemotaxis and phagocytosis and increases the risk of postoperative infections. Furthermore, diabetes-induced microvascular dysfunction may lead to inadequate tissue perfusion, delaying wound healing and increasing the rates of ischemic complications[11]. These mechanisms indicate that diabetic patients with meningioma may encounter increased risks during and after surgery, requiring meticulous management strategies.

Cerebral edema constitutes a notable concern in neurosurgical patients, especially those undergoing meningioma resection. This condition is often induced by surgical trauma and may result in elevated intracranial pressure, brain herniation, and severe neurological impairments. Diabetes may aggravate cerebral edema by influencing vascular permeability and endothelial function. Hyperglycemia disrupts the blood-brain barrier, promoting vasogenic edema and hindering astrocyte function, which is essential for sustaining osmotic balance within the brain[12,13]. Consequently, diabetic patients may face an increased risk of postoperative cerebral edema, which can complicate recovery, necessi

Neurological complications after meningioma surgery include a spectrum of problems ranging from temporary cognitive impairment to permanent neurological deficits. The etiology of these complications is multifactorial, and diabetes introduces additional risk factors that can exacerbate neurological damage. For instance, diabetic neuropathy and retinopathy are recognized complications of chronic hyperglycemia, indicating potential for similar deleterious effects on the central nervous system. Moreover, diabetes-related cerebrovascular changes, such as small vessel disease and accelerated atherosclerosis, may impair cerebral blood flow and oxygen delivery, increasing the risk of ischemic events during and after surgery[14,15].

Given the high prevalence of diabetes and its known detrimental effects on surgical outcomes, understanding its impact on patients undergoing meningioma resection is essential. Previous studies have explored the relationship between diabetes and postoperative complications in various surgical domains. However, data specifically pertaining to neurosurgery, especially meningioma resection, are scarce. This study aims to investigate whether diabetes prolongs hospital stay and increases the risk of infection, cerebral edema, and neurological complications in patients undergoing meningioma resection. By elucidating these relationships, we aim to enhance clinical practice and optimize perioperative management strategies for diabetic patients undergoing neurosurgical interventions.

This retrospective study seeks to assess whether diabetes mellitus prolongs hospital stay and elevates the risk of infection, cerebral edema, and neurological complications in patients with meningioma. A total of 516 patients with primary meningioma who underwent meningioma resection surgery at Tangdu Hospital, Fourth Military Medical University, from January 2018 to January 2022, were included. All procedures in this study complied with the ethical standards set by the institutional and national ethics committees for human experimentation and were consistent with the Declaration of Helsinki of 1964 and its subsequent amendments. The study received approval from the institutional review board of the hospital. Given that the study utilized anonymized patient data, which presented no potential risk or effect on patient care, the institutional review board and ethics committee of the hospital opted to waive the requirement for informed consent for this retrospective study.

Inclusion criteria: (1) Patients aged ≥ 18 years; (2) Primary meningioma confirmed according to European Association of Neuro-Oncology guideline[16]; (3) Patients who underwent surgical resection for meningioma; (4) Absence of wound infections or inflammations due to other causes; and (5) Complete medical records and follow-up data.

Exclusion criteria: (1) Secondary or recurrent meningioma; (2) Patients with a current or past history of other cancers besides meningioma; (3) Patients with severe cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, respiratory diseases, or severe liver and kidney dysfunction; (4) Patients with a record of alcohol abuse or human immunodeficiency virus infection; and (5) Pregnant or lactating women.

The patients were categorized into two groups according to their clinical history of type 2 diabetes mellitus for a minimum of six months preceding the imaging diagnosis of an intracranial meningioma, which was consistently confirmed at diagnosis by standard criteria [glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) ≥ 6.5% and/or fasting plasma glucose ≥ 7.0 mmol/L][6]: (1) Non-diabetics group; and (2) Diabetics group. A total of 411 patients without a previous diagnosis of type 1 or type 2 diabetes comprised the non-diabetics group, whereas 105 patients with a prior diagnosis of type 2 diabetes constituted the diabetics group. The treatment modalities for diabetes, including oral hypoglycemic agents, insulin therapy, and dietary interventions, were recorded. The study’s primary objective was to compare outcomes on the basis of the presence or absence of diabetes. Treatment was excluded as a stratification variable in the primary analysis because of the diversity of regimens. All diabetic patients underwent standard perioperative glycemic management.

The surgery was performed under general anesthesia with the aid of endotracheal intubation. Conventional microsurgical techniques were employed for tumor resection. Upon the completion of tumor reduction or excision, the bone flap was repositioned, and the scalp was re-draped. Resected bone was excised, and cranioplasty for aesthetically significant defects was performed using titanium mesh (BLGWIII0608, Shangshen, China) and/or methyl methacrylate (80-62-6, Kaisai, China). Upon incision, all patients were administered 10 mg of Decadron (D1756, LABLEAD, China),

Baseline data collection: Baseline demographic and clinical information will be collected from the medical record system for all enrolled patients. Tumor grading is categorized as World Health Organization (WHO) grade I, II, or III according to the assessment of the resected tumor by a neuropathologist.

Perioperative data: The extent of surgical resection is categorized as either gross total resection or incomplete resection, determined by the analysis of immediate postoperative magnetic resonance imaging scans conducted by a neuroradiologist. During the surgical procedure, any infections necessitating irrigation, hematomas necessitating evacuation, and hydrocephalus necessitating shunting are documented.

Blood glucose measurement: Preoperative blood glucose level is ascertained from the most recent fasting blood glucose measurement prior to the surgical date. The postoperative blood glucose level is defined as the mean blood glucose of the patient from the conclusion of surgery until hospital discharge. The plasma glucose concentration was quantified utilizing the Beckman Glucose Analyzer II (Beckman, United States).

Stages of surgical wound healing: Wound healing can be classified into three types based on the severity of injury and infection: (1) Primary intention healing; (2) Secondary intention healing; and (3) Tertiary intention healing. Primary intention healing transpires in wounds characterized by minimal tissue loss, clean edges, lack of infection, and tight closure after suturing, such as surgical incisions. This wound type demonstrates mild inflammation; epithelial regeneration occurs within 24-48 hours, granulation tissue rapidly fills the wound by the third day, collagen fibers develop within five days or six days, and complete healing occurs within two or three weeks, resulting in a linear scar. Secondary intention healing occurs in wounds characterized by substantial tissue loss, irregular margins, misalignment, or the presence of infection, in contrast to primary healing. Regeneration can only commence following the control of infection and the excision of necrotic tissue owing to the presence of extensive necrotic tissue or severe inflammation induced by infection. These wounds demonstrate substantial contraction, with abundant granulation tissue proliferating from the wound base and margins to occupy the defect. Tertiary intention healing, or healing beneath a scab, refers to the process in which blood and necrotic debris at the wound surface desiccate to create a dark brown, rigid crust, while healing transpires beneath the scab. The regeneration of epithelial tissue ultimately results in the detachment of the scab, although this process is prolonged. The epidermis must initially dissolve the scab for regeneration, as the scab's desiccated environment hinders bacterial proliferation and offers protection to the wound. However, if the scab obstructs the drainage of exudate and worsens infection, it may impede healing[17].

Blood tests: Prior to and following surgery, 5 mL of fasting venous blood is obtained from patients before 8 AM for the assessment of inflammatory markers. The blood is subjected to centrifugation at 3000 × g for five minutes, after which the supernatant is retrieved. The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay is employed to identify serum levels of C-reactive protein (CRP), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α). This process employs CRP (ab260058, Abcam, United States), IL-6 (ab178013, Abcam, United States), and TNF-α (ab181421, Abcam, United States) kits. A DxH800 hematology analyzer (Beckman Coulter, United States) is utilized to quantify albumin, platelets, and leukocytes. Every blood test result is replicated three times to ensure accuracy.

Brain edema: The extent of brain edema in patients is assessed and graded before and after surgery by using computed tomography scans, and patients whose condition has worsened postoperatively compared to preoperatively are documented. Brain edema is categorized as follows: (1) Mild edema is defined as an extent of ≤ 2 cm; (2) Moderate edema as > 2 cm but ≤ 3 cm; and (3) Severe edema as > 3 cm[18]. To assess the clinical impact, the occurrence of new neurological deficits or indicators of elevated intracranial pressure (e.g., headache, vomiting, altered consciousness) attributable to cerebral edema was documented. The necessity for particular interventions beyond standard postoperative care, including intensified dehydrating therapy (e.g., supplementary boluses of mannitol or hypertonic saline) or subsequent decompressive surgery, was recorded.

Perioperative Karnofsky Performance Status score: An observer evaluates the Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS) score through clinical assessments conducted during preoperative consultations, the initial postoperative visit, and six months following surgery. The KPS scores ranges from 0 to 100. A total of 100 indicates that the patient is asymptomatic and capable of engaging in normal activities, whereas 0 denotes mortality. Elevated scores indicate improved physical condition.

Length of stay: The duration of postoperative hospitalization and ICU admission for each patient is documented, along with any postoperative emergency department (ED) visits occurring within 90 days post-surgery. The length of stay variable is defined as the duration in days from surgery to discharge. The ICU length of stay variable is defined as the duration, in days, that a patient remains in the ICU after surgical resection. A postoperative ED presentation variable was established for patients presenting to the ED within 90 days following surgery. The medical records of each patient were examined to identify entries documenting pertinent ED visits at external hospitals or Tangdu Hospital, Fourth Military Medical University.

Postoperative complications: He follow-up duration is defined as the interval between surgery and the final consultation with the attending neurosurgeon. All anticipated components of postoperative complications encountered by each patient during the follow-up period are documented. Postoperative complications encompass the following occurrences subsequent to surgery and within the follow-up period: (1) Seizure; (2) Urinary tract infection; (3) Deep vein thrombosis; (4) External ventricular drainage or ventriculoperitoneal shunt placement; (5) Any surgical site infection (SSI); (6) Pneumonia, transfusion; (7) Cerebrovascular accident; and (8) Any additional complication. SSI was categorized based on the criteria established by the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/National Healthcare Safety Network[19] as superficial incisional SSI (involving skin/subcutaneous tissue), deep incisional SSI (involving deep soft tissues), or organ/space SSI (such as meningitis and intracranial abscess).

This study employed IBM SPSS Statistics version 29.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States) for data processing and statistical analysis. Categorical variables were expressed as n (%). The χ2 test was employed for the evaluation of categorical data. Continuous variables adhering to a normal distribution were presented as mean ± SD. An independent samples t-test was employed for normally distributed continuous data. Univariable and multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression models were employed to calculate hazard ratio (HR) with 95%CI for long-term time-to-event outcomes, specifically tumor recurrence and mortality.

Demographic characteristics were analyzed between the diabetics (n = 105) and non-diabetics group (n = 411) (Table 1). No significant differences were observed in age, body mass index, gender, ethnicity, educational attainment, residential location, or income level (all P > 0.05). The balanced demographics of the two groups enhance the reliability of subsequent analyses, reducing potential confounding effects.

| Parameters | Diabetics group (n = 105) | Non-diabetics group (n = 411) | t/χ2 | P value |

| Age (years) | 55.14 ± 6.65 | 56.46 ± 7.44 | 1.653 | 0.099 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 28.72 ± 4.53 | 28.93 ± 3.25 | 0.451 | 0.652 |

| Gender | 0.058 | 0.809 | ||

| Male | 43 (40.95) | 163 (39.66) | ||

| Female | 62 (59.05) | 248 (60.34) | ||

| Ethnicity | 0.227 | 0.634 | ||

| Han | 97 (92.38) | 385 (93.67) | ||

| Other | 8 (7.62) | 26 (6.33) | ||

| Education level | 0.825 | 0.364 | ||

| High school or below | 79 (75.24) | 326 (79.32) | ||

| Tertiary and above | 26 (24.76) | 85 (20.68) | ||

| Residence location | 0.082 | 0.775 | ||

| Rural | 35 (33.33) | 131 (31.87) | ||

| Urban | 70 (66.67) | 280 (68.13) | ||

| Income level (thousand/month) | 3.74 ± 1.45 | 3.98 ± 1.21 | 1.551 | 0.123 |

No significant differences were observed in tumor location (P = 0.705), maximum tumor diameter (P = 0.607), maximum tumor diameter stratification (P = 0.789), WHO grade (P = 0.672), and postoperative follow-up duration (P = 0.960) between the diabetics and non-diabetics groups (all P > 0.05; Table 2). Significant differences were observed in HbA1c levels (P < 0.001), and the diabetics group exhibited higher values (7.01% ± 0.46%) than the non-diabetics group (4.45% ± 0.56%). The diabetics group exhibited an average diabetes duration of 3.56 ± 1.04 years. These results underscore the divergent glycemic control status between the two groups, whereas other clinical characteristics remain equitable.

| Parameters | Diabetics group (n = 105) | Non-diabetics group (n = 411) | t/χ2 | P value |

| Tumor location | 0.143 | 0.705 | ||

| Convexity/falx | 62 (59.05) | 251 (61.07) | ||

| Skull base | 43 (40.95) | 160 (38.93) | ||

| Tumor max diameter (cm) | 4.23 ± 0.54 | 4.26 ± 0.41 | 0.515 | 0.607 |

| Tumor max diameter stratification | 0.072 | 0.789 | ||

| Less than 5 cm | 67 (63.81) | 268 (65.21) | ||

| Greater than or equal to 5 cm | 38 (36.19) | 143 (34.79) | ||

| World Health Organization grade | 0.794 | 0.672 | ||

| I | 76 (72.38) | 303 (73.72) | ||

| II | 21 (20.00) | 86 (20.92) | ||

| III | 8 (7.62) | 22 (5.35) | ||

| Postoperative follow-up (months) | 38.72 ± 1.02 | 38.71 ± 1.21 | 0.050 | 0.960 |

| Glycated hemoglobin (%) | 7.01 ± 0.46 | 4.45 ± 0.56 | 48.368 | < 0.001 |

| Duration of diabetes (years) | 3.56 ± 1.04 | - |

No significant differences were observed in perioperative characteristics between the diabetics and non-diabetics groups regarding the extent of surgical resection (P = 0.648), infection necessitating washout (P = 0.176), hematoma requiring evacuation (P = 0.201), and hydrocephalus necessitating shunt (P = 0.201; all P > 0.05; Table 3). The comparable perioperative outcomes, including surgical resection extent and complication rates, indicate that diabetes does not substantially influence these specific perioperative parameters.

| Parameters | Diabetics group (n = 105) | Non-diabetics group (n = 411) | χ2 | P value |

| Extent of surgical resection | 0.209 | 0.648 | ||

| GTR | 83 (79.05) | 333 (81.02) | ||

| No GTR | 22 (20.95) | 78 (18.98) | ||

| Infection requiring washout | 9 (8.57) | 21 (5.11) | 1.830 | 0.176 |

| Hematoma requiring evacuation | 2 (1.90) | 1 (0.24) | 1.637 | 0.201 |

| Hydrocephalus requiring shunt | 2 (1.90) | 1 (0.24) | 1.637 | 0.201 |

Significant differences in infection-related parameters were observed between the groups (Table 4). Pre-operative blood glucose levels and wound healing grading exhibited a significant difference (P < 0.001), and 73 diabetics attained primary wound healing without infection unlike 376 non-diabetics. Conversely, 32 diabetics underwent secondary or tertiary wound healing with infection, compared with 35 non-diabetics. Postoperative albumin levels were significantly lower in diabetics (291.78 ± 13.10 vs 300.97 ± 13.72; P < 0.001). Postoperative platelet counts (269.08 ± 6.62 vs 266.67 ± 7.44; P = 0.003), white blood cell counts (15.61 ± 4.98 vs 14.52 ± 3.63; P = 0.037), CRP levels (133.94 ± 18.12 vs 128.63 ± 18.24; P = 0.008), and TNF-α levels (61.17 ± 7.42 vs 59.31 ± 7.52; P = 0.024) were significantly higher in the diabetics group. No significant differences were observed in post-operative blood glucose levels, preoperative albumin, preoperative platelet count, preoperative white blood cell count, preoperative CRP, preoperative IL-6, or postoperative IL-6 (all P > 0.05). The results indicate that diabetic patients possess an elevated risk of wound infections and exhibit unique postoperative inflammatory responses.

| Parameters | Diabetics group (n = 105) | Non-diabetics group (n = 411) | t/χ2 | P value |

| Grading of wound healing | 35.698 | < 0.001 | ||

| Primary wound healing without infection | 73 (69.52) | 376 (91.48) | ||

| Secondary and tertiary wound healing with infection | 32 (30.48) | 35 (8.52) | ||

| Pre-operative blood glucose (mg/dL) | 151.54 ± 17.61 | 119.85 ± 15.93 | 17.795 | < 0.001 |

| Post-operative blood glucose (mg/dL) | 190.50 ± 14.20 | 189.70 ± 12.40 | 0.572 | 0.568 |

| Preoperative albumin (mg/L) | 378.42 ± 13.41 | 379.52 ± 13.51 | 0.750 | 0.454 |

| Postoperative albumin (mg/L) | 291.78 ± 13.10 | 300.97 ± 13.72 | 6.185 | < 0.001 |

| Preoperative platelet count (109/L) | 145.52 ± 7.41 | 145.42 ± 6.68 | 0.134 | 0.894 |

| Postoperative platelet count (109/L) | 269.08 ± 6.62 | 266.67 ± 7.44 | 3.019 | 0.003 |

| Preoperative white blood cell count (109/L) | 5.93 ± 1.24 | 5.83 ± 1.31 | 0.671 | 0.502 |

| Postoperative white blood cell count (109/L) | 15.61 ± 4.98 | 14.52 ± 3.63 | 2.104 | 0.037 |

| Preoperative CRP (mg/L) | 3.21 ± 1.31 | 2.96 ± 1.01 | 1.815 | 0.072 |

| Postoperative CRP (mg/L) | 133.94 ± 18.12 | 128.63 ± 18.24 | 2.664 | 0.008 |

| Preoperative IL-6 (ng/mL) | 20.53 ± 2.23 | 20.16 ± 2.63 | 1.475 | 0.142 |

| Postoperative IL-6 (ng/mL) | 28.42 ± 5.67 | 27.26 ± 5.41 | 1.945 | 0.052 |

| Preoperative TNF-α (pg/mL) | 51.35 ± 7.56 | 50.85 ± 7.78 | 0.591 | 0.555 |

| Postoperative TNF-α (pg/mL) | 61.17 ± 7.42 | 59.31 ± 7.52 | 2.267 | 0.024 |

Significant differences in postoperative cerebral edema parameters were observed between the diabetics and non-diabetics groups (P = 0.015; Table 5). Specifically, 27 (25.71%) patients in the Diabetics group experienced postoperative cerebral edema, whereas 64 (15.57%) patients in the non-diabetics group did. Diabetic patients exhibited markedly elevated rates of cerebral edema necessitating targeted medical or surgical intervention (7.62% vs 1.95%; P = 0.007). No significant differences were observed in preoperative cerebral edema (P = 0.943), symptomatic cerebral edema (P = 0.373), or postoperative exacerbation of cerebral edema (P = 0.221).

| Parameters | Diabetics group (n = 105) | Non-diabetics group (n = 411) | χ2 | P value |

| Preoperative cerebral edema | 12 (11.43) | 48 (11.68) | 0.005 | 0.943 |

| Postoperative cerebral edema | 27 (25.71) | 64 (15.57) | 5.923 | 0.015 |

| Postoperative cerebral edema worsens | 21 (20.00) | 62 (15.09) | 1.497 | 0.221 |

| Symptomatic cerebral edema | 11 (10.48) | 32 (7.79) | 0.792 | 0.373 |

| Cerebral edema requiring intervention | 8 (7.62) | 8 (1.95) | 7.168 | 0.007 |

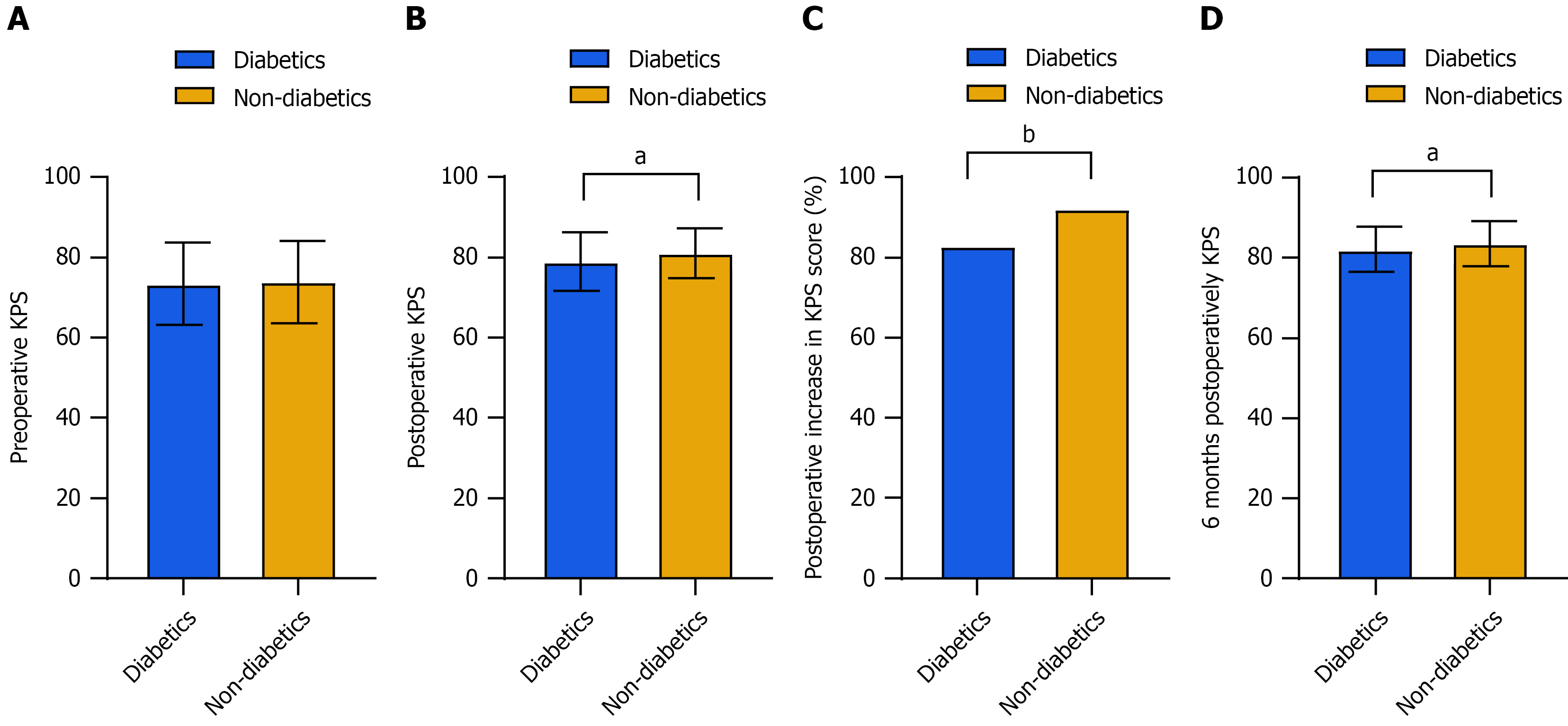

Significant differences were observed in KPS scores when comparing the diabetic group to the non-diabetic group: (1) Postoperative KPS scores (79.04 ± 7.36 vs 81.06 ± 6.24; P = 0.011); (2) Postoperative increase in KPS scores (82.86% vs 92.21%; P = 0.004); and (3) KPS scores at six months postoperatively (82.13 ± 5.56 vs 83.56 ± 5.57; P = 0.019; Figure 1). No significant difference was observed in preoperative KPS scores (P = 0.708). The findings suggest that diabetic patients have lower postoperative KPS scores and a lower probability of KPS scores enhancement postoperatively, indicating that diabetes adversely affects postoperative recovery and quality of life.

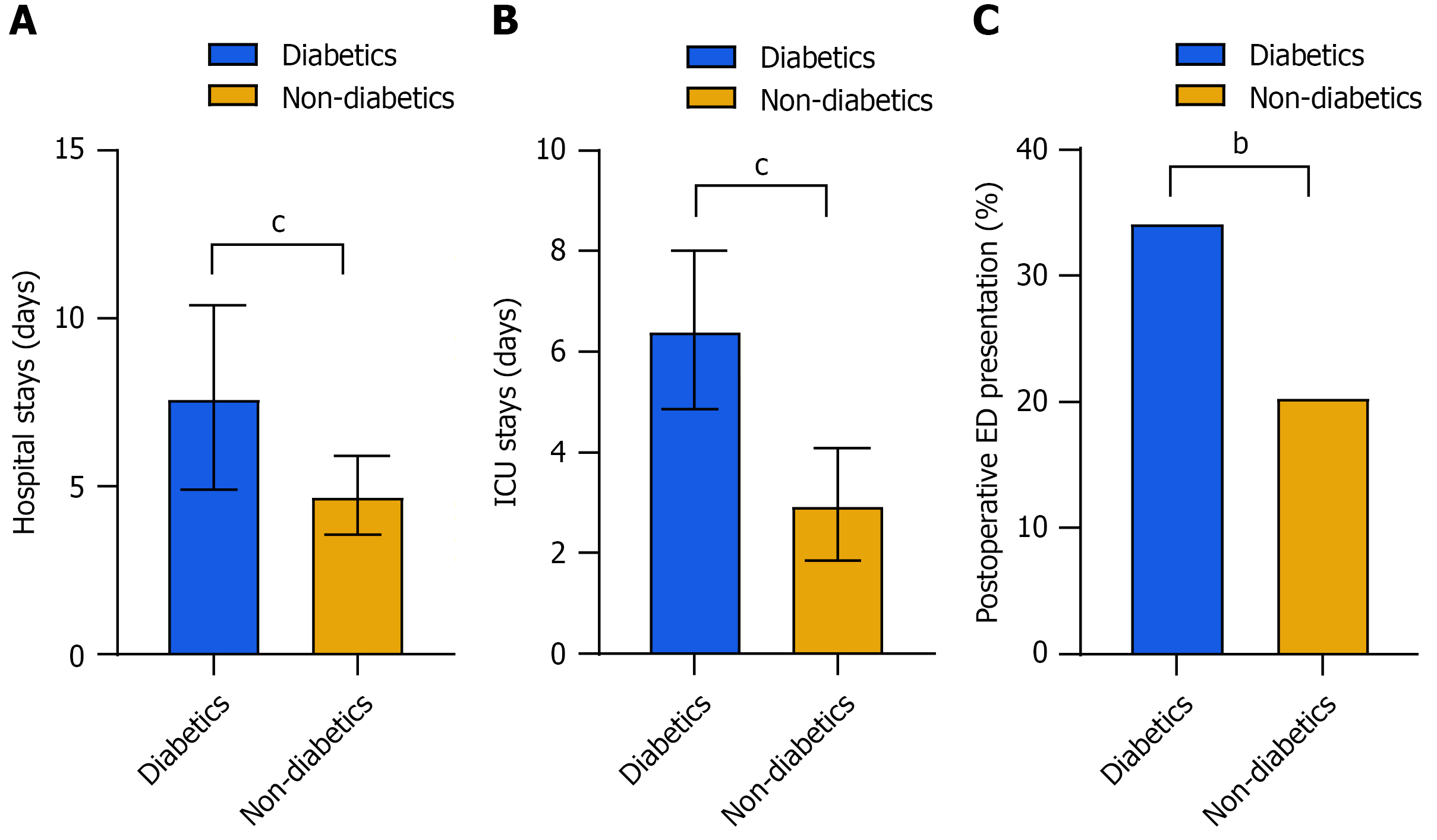

Significant differences were observed in hospitalization and ED visits between the diabetics and non-diabetics groups (Figure 2). The Diabetics group had a significantly longer hospital stay (7.65 ± 2.74 vs 4.73 ± 1.18; P < 0.001). The duration of ICU stays was significantly longer in the diabetics group (6.43 ± 1.57 days vs 2.97 ± 1.12 days; P < 0.001). A greater percentage of diabetic patients visited the ED postoperatively (P = 0.003). These findings indicate that diabetic patients exhibit elevated healthcare utilization and an augmented risk of complications.

Significant differences in postoperative complications were observed between the diabetics and non-diabetics groups (Table 6). The diabetics group exhibited a significantly higher incidence of seizure (P = 0.003) and SSI (P < 0.001) and more complications (P < 0.001). No significant differences were observed in external ventricular drainage/ventriculoperitoneal shunt (P = 0.392), cerebrovascular accident (P = 0.126), urinary tract infection (P = 0.309), transfusion (P = 0.590), pneumonia (P = 0.309), or deep vein thrombosis (P = 0.392). These findings underscore the elevated risk of specific complications in individuals with diabetes.

| Parameters | Diabetics group (n = 105) | Non-diabetics group (n = 411) | χ2 | P value |

| Seizure | 13 (12.38) | 19 (4.62) | 8.654 | 0.003 |

| External ventricular drainage/ventriculoperitoneal shunt | 2 (1.90) | 2 (0.49) | 0.732 | 0.392 |

| Any SSI | 8 (7.62) | 2 (0.49) | 18.792 | < 0.001 |

| Superficial incisional SSI | 5 (4.76) | 1 (0.24) | ||

| Deep incisional SSI | 3 (2.86) | 1 (0.24) | ||

| Organ/space SSI | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Cerebrovascular accident | 7 (6.67) | 12 (2.92) | 2.339 | 0.126 |

| Urinary tract infection | 3 (2.86) | 4 (0.97) | 1.034 | 0.309 |

| Transfusion | 2 (1.90) | 3 (0.73) | 0.290 | 0.590 |

| Pneumonia | 3 (2.86) | 4 (0.97) | 1.034 | 0.309 |

| Deep vein thrombosis | 2 (1.90) | 2 (0.49) | 0.732 | 0.392 |

| Any complications | 33 (31.43) | 42 (10.22) | 30.286 | < 0.001 |

Significant differences were observed when comparing long-term outcomes between the diabetic group and the non-diabetic group (Table 7). The diabetic cohort exhibited a markedly elevated tumor recurrence rate (4.76% vs 0.49%; P = 0.004), signifying an augmented risk for tumor recurrence. The diabetic cohort exhibited a higher mortality rate (2.86% vs 0.24%; P = 0.036), indicating an increased long-term mortality risk.

| Parameters | Diabetics group (n = 105) | Non-diabetics group (n = 411) | χ2 | P value |

| Tumor recurrence rate | 5 (4.76) | 2 (0.49) | 8.452 | 0.004 |

| Mortality rate | 3 (2.86) | 1 (0.24) | 4.419 | 0.036 |

To account for follow-up time and adjust for potential confounders, we conducted a Cox proportional hazards regression analysis (Table 8). In univariable analysis, diabetes was linked to a markedly elevated risk of tumor recurrence (HR = 9.45; 95%CI: 1.84-48.47; P = 0.007) and mortality (HR = 11.45; 95%CI: 1.18-111.18; P = 0.036). Following adjustments for age, WHO grade, and extent of resection, diabetes persisted as a significant independent predictor of tumor recurrence (adjusted HR = 8.92; 95%CI: 1.73-45.87; P = 0.009) and exhibited a pronounced trend towards elevated mortality (adjusted HR = 10.12, 95%CI: 1.00-102.55; P = 0.048).

| Outcome | Variable | Univariable analysis HR (95%CI) | P value | Multivariable analysis HR (95%CI) | P value |

| Tumor recurrence | Diabetes | 9.45 (1.84-48.47) | 0.007 | 8.92 (1.73-45.87) | 0.009 |

| Age | 1.02 (0.94-1.11) | 0.623 | 1.02 (0.94-1.11) | 0.642 | |

| WHO grade (II/III) | 1.58 (0.31-8.07) | 0.583 | 1.42 (0.27-7.38) | 0.677 | |

| Extent of surgical resection (non-GTR) | 2.15 (0.42-10.97) | 0.356 | 1.89 (0.37-9.71) | 0.445 | |

| Mortality | Diabetes | 11.45 (1.18-111.18) | 0.036 | 10.12 (1.00-102.55) | 0.048 |

| Age | 1.06 (0.95-1.18) | 0.288 | 1.06 (0.95-1.18) | 0.295 | |

| WHO grade (II/III) | 2.11 (0.19-23.10) | 0.543 | 1.75 (0.16-19.33) | 0.650 | |

| Extent of surgical resection (non-GTR) | 3.01 (0.27-33.10) | 0.365 | 2.56 (0.23-28.65) | 0.443 |

This study aimed to assess the influence of diabetes on hospital duration and postoperative complications in patients undergoing meningioma resection. Our research reveals significant distinctions between diabetic and non-diabetic patients, providing insights into the mechanisms underlying these differences and their implications for clinical practice.

One notable difference observed was in HbA1c level, reflecting divergent glycemic control status between diabetic and non-diabetic patients. Increased HbA1c levels in diabetic patients indicate persistent hyperglycemia, which is associated with numerous detrimental outcomes via various mechanisms. Chronic hyperglycemia leads to the production of AGEs, which disrupt collagen synthesis and cross-linking and thereby compromise wound integrity. Oxidative stress and inflammation hinder the healing process. AGEs can activate pro-inflammatory pathways, resulting in heightened expression of cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-6, which aggravate tissue damage and impede recovery[20,21]. These mechanisms collectively contribute to elevated infection rates and prolonged healing times in diabetic patients.

Diabetic patients exhibited an elevated risk of wound infections and distinct postoperative inflammatory responses. Reduced postoperative albumin levels and elevated white blood cell counts and CRP and TNF-α levels in diabetic patients indicate a heightened inflammatory state. Previous studies have shown that hyperglycemia impairs neutrophil function, reducing chemotaxis and phagocytosis, which are crucial processes for combating infections[22]. Diabetes-related microvascular dysfunction leads to inadequate tissue perfusion, thereby impairing immune response and wound healing. The interplay of compromised immune function and educed tissue perfusion fosters an environment favorable for bacterial colonization and infection[23]. Efficient regulation of blood glucose levels during the perioperative phase is crucial to reduce these risks.

Postoperative cerebral edema was more common in diabetic patients than in non-diabetic patients. Hyperglycemia compromises the blood–brain barrier, promotes vasogenic edema, and impairs astrocyte function, which is essential for preserving osmotic balance within the brain[24,25]. Astrocytes maintain ion homeostasis and facilitate water transport; their impairment from hyperglycemia may result in excessive fluid retention and cerebral edema[26,27]. In the context of meningioma surgery, hyperglycemia-induced blood-brain barrier disruption may be further intensified by surgical trauma and the tumor's inherent biology[28]. Hyperglycemia has been demonstrated to upregulate vascular endothelial growth factor, a crucial mediator of vascular permeability commonly found in meningiomas, potentially fostering a conducive environment for significant postoperative edema[29]. Moreover, chronic hyperglycemia induces oxidative stress, which compromises endothelial cells and exacerbates the disruption of the blood–brain barrier. This disruption allows proteins and fluids to infiltrate the brain parenchyma, exacerbating cerebral edema. Close monitoring and prompt intervention strategies, such as corticosteroid or mannitol administration, may be essential for the effective management of this complication[30,31].

Diabetic patients demonstrated reduced postoperative KPS scores and a diminished probability of KPS scores enhancement following surgery. This finding indicates that diabetes may adversely affect postoperative recovery and quality of life. Chronic hyperglycemia can result in multiple systemic complications, such as cardiovascular disease and neuropathy, potentially impairing overall functional status[32]. Furthermore, the psychological strain of managing a chronic illness such as diabetes can influence patients' mental well-being and motivation, thereby affecting their overall quality of life[33]. Comprehensive perioperative care incorporating multidisciplinary support is crucial for enhancing outcomes in diabetic patients undergoing meningioma resection.

Diabetic patients endured prolonged hospital and ICU admissions, as well as an increased incidence of postoperative presentations to the ED. The elevated healthcare utilization indicates the increased risk of complications in diabetic patients. Prolonged hospitalizations and ICU admissions elevate healthcare expenses and subject patients to heightened risks, including nosocomial infections[34,35]. Therefore, customized perioperative management strategies are crucial for alleviating the strain on healthcare resources and enhancing patient outcomes.

Diabetic patients exhibited a higher risk of tumor recurrence and mortality over the long term. Chronic hyperglycemia may promote tumor growth through various mechanisms, such as insulin resistance and altered angiogenesis. Insulin resistance leads to compensatory hyperinsulinemia, which can stimulate tumor growth by activating insulin-like growth factor 1 receptors. Additionally, hyperglycemia-induced oxidative stress and inflammation create a microenvironment conducive to tumor progression. The increased risk of complications and prolonged recovery times may also contribute to poorer long-term outcomes[36,37]. Optimizing glycemic control and implementing comprehensive follow-up care are crucial to improving long-term prognosis in diabetic patients undergoing meningioma resection.

Several limitations should be considered when interpreting our findings. First, as a retrospective study, our design may introduce selection bias and restrict the generalizability of our findings. The absence of multivariable adjustment for potential confounders limits our capacity to make robust causal inferences. Second, despite our efforts to account for several key variables, unmeasured confounders may still affect the observed relationships. The limited number of long-term events in our cohort presents considerable difficulties in establishing strong causal relationships. Future prospective studies with larger sample sizes and longer follow-up periods are needed to validate our findings. Although this study focused on the effect of the diabetic state, future prospective studies incorporating continuous glucose monitoring to assess the role of perioperative glycemic variability on complications would provide valuable insights. Further research should focus on identifying specific biomarkers and developing targeted interventions to mitigate the adverse effects of diabetes on surgical outcomes in patients with meningioma. By addressing these gaps, we can enhance our un

In conclusion, our study suggests that diabetes may prolong hospital stay and elevate the risk of infection, cerebral edema, and neurological complications in patients undergoing meningioma resection. These findings highlight the necessity for meticulous perioperative management and prolonged follow-up for diabetic patients. Although additional research is necessary to clarify the mechanisms behind these associations, our findings offer significant insights that may enhance clinical practice and inform strategies to improve outcomes in this at-risk population.

This study reveals that diabetes markedly extends hospital duration and heightens the risk of postoperative complications, such as infections, cerebral edema, and neurological deficits, in patients undergoing meningioma resection. Diabetic patients exhibited elevated HbA1c levels, indicating poor glycemic control, which resulted in compromised wound healing and heightened inflammatory responses. They experienced more frequent wound infections, heightened cerebral edema, diminished KPS scores, and a higher incidence of seizures. These findings underscore the need for optimized perioperative management and comprehensive follow-up care, which can improve outcomes in diabetic patients with meningioma. Efficient blood glucose regulation and specific interventions are essential for reducing these risks and improving patient recovery.

| 1. | Lotsch C, Warta R, Herold-Mende C. The Molecular and Immunological Landscape of Meningiomas. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25:9631. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Khan M, Hanna C, Findlay M, Lucke-Wold B, Karsy M, Jensen RL. Modeling Meningiomas: Optimizing Treatment Approach. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2023;34:479-492. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Azab MA, Cole K, Earl E, Cutler C, Mendez J, Karsy M. Medical Management of Meningiomas. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2023;34:319-333. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Deng Y, Yu L, Lv Y, Liu X, Chu J, Gao Z, Hao S, Ji N. Surgical Resection of Large Primary Intraosseous Meningiomas (6 Case Reports). World Neurosurg. 2023;175:e336-e343. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Schartz D, Furst T, Ellens N, Kohli GS, Rahmani R, Akkipeddi SMK, Schmidt T, Bhalla T, Mattingly T, Bender MT. Preoperative Embolization of Meningiomas Facilitates Reduced Surgical Complications and Improved Clinical Outcomes : A Meta-analysis of Matched Cohort Studies. Clin Neuroradiol. 2023;33:755-762. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Harreiter J, Roden M. [Diabetes mellitus: definition, classification, diagnosis, screening and prevention (Update 2023)]. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2023;135:7-17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Hadebe L, Houreld NN. Therapeutic Potential of Photobiomodulation in Diabetic Complications. Discov Med. 2024;36:1987-1997. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Zheng XL, Chen L, Fan CL, Xiao SJ, Chen SB, Yang FM. Hyperbaric Lidocaine Aggravates Diabetic Neuropathic Pain by Targeting p38 MAPK/ERK and PINK1/Parkin-Mediated Mitophagy Signaling Pathway. Discov Med. 2024;36:992-1001. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Sideris G, Davoutis E, Panagoulis E, Maragkoudakis P, Nikolopoulos T, Delides A. A Systematic Review of Intracranial Complications in Adults with Pott Puffy Tumor over Four Decades. Brain Sci. 2023;13:587. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Tseng CC, Huang YC, Tu PH, Yip PK, Chang TW, Lee CC, Chen CC, Chen NY, Liu ZH. Impact of Diabetic Hyperglycemia on Clinical Outcomes in Patients with Diabetes Mellitus Following Traumatic Brain Injury. Turk Neurosurg. 2023;33:548-555. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Crowley K, Scanaill PÓ, Hermanides J, Buggy DJ. Current practice in the perioperative management of patients with diabetes mellitus: a narrative review. Br J Anaesth. 2023;131:242-252. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Xu Q, Yang Y, Huang Q, Xie L, Feng Y, Yang L. Extracellular(Serum) Levels of Matrix Metalloproteinases in Pediatric Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus and Association with Diabetic Ketoacidosis and Cerebral Edema. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2025;18:819-830. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Namatame K, Igarashi Y, Nakae R, Suzuki G, Shiota K, Miyake N, Ishii H, Yokobori S. Cerebral edema associated with diabetic ketoacidosis: Two case reports. Acute Med Surg. 2023;10:e860. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Li S, Yang D, Zhou X, Chen L, Liu L, Lin R, Li X, Liu Y, Qiu H, Cao H, Liu J, Cheng Q. Neurological and metabolic related pathophysiologies and treatment of comorbid diabetes with depression. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2024;30:e14497. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 18.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | García-Casares N, González-González G, de la Cruz-Cosme C, Garzón-Maldonado FJ, de Rojas-Leal C, Ariza MJ, Narváez M, Barbancho MÁ, García-Arnés JA, Tinahones FJ. Effects of GLP-1 receptor agonists on neurological complications of diabetes. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2023;24:655-672. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Goldbrunner R, Stavrinou P, Jenkinson MD, Sahm F, Mawrin C, Weber DC, Preusser M, Minniti G, Lund-Johansen M, Lefranc F, Houdart E, Sallabanda K, Le Rhun E, Nieuwenhuizen D, Tabatabai G, Soffietti R, Weller M. EANO guideline on the diagnosis and management of meningiomas. Neuro Oncol. 2021;23:1821-1834. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 559] [Cited by in RCA: 465] [Article Influence: 93.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Wang J, Shou J, Gao H, Wang B, Ding P, Yang P. Analysis of risk factors affecting wound healing and wound infection after meningioma resection. Int Wound J. 2024;21:e14870. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Metter RB, Rittenberger JC, Guyette FX, Callaway CW. Association between a quantitative CT scan measure of brain edema and outcome after cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2011;82:1180-1185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 200] [Cited by in RCA: 188] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Mangram AJ, Horan TC, Pearson ML, Silver LC, Jarvis WR. Guideline for Prevention of Surgical Site Infection, 1999. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Hospital Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. Am J Infect Control. 1999;27:97-132; quiz 133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1992] [Cited by in RCA: 2082] [Article Influence: 77.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Matić P, Atanasijević I, Stojković VM, Soldatović I, Tanasković S, Babić S, Gajin P, Lozuk B, Vučurević G, Đoković A, Živić R, Đulejić V, Nešković M, Babić A, Ilijevski N. Impact of haemoglobin A1c on wound infection in patients with diabetes with implanted synthetic graft. J Wound Care. 2024;33:136-142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Lee SH, Kim SH, Kim KB, Kim HS, Lee YK. Factors Influencing Wound Healing in Diabetic Foot Patients. Medicina (Kaunas). 2024;60:723. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kim SH, Yoon SM, Ahn JH, Choi YJ. Effect of Remimazolam and Propofol on Blood Glucose and Serum Inflammatory Markers in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: A Clinical Trial with Prospective Randomized Control. Medicina (Kaunas). 2025;61:523. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Li Y, Lin L, Zhang W, Wang Y, Guan Y. Genetic association of type 2 diabetes mellitus and glycaemic factors with primary tumours of the central nervous system. BMC Neurol. 2024;24:458. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Li L, Wang M, Ma YM, Yang L, Zhang DH, Guo FY, Jing L, Zhang JZ. Selenium inhibits ferroptosis in hyperglycemic cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury by stimulating the Hippo pathway. PLoS One. 2023;18:e0291192. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Joya A, Plaza-García S, Padro D, Aguado L, Iglesias L, Garbizu M, Gómez-Vallejo V, Laredo C, Cossío U, Torné R, Amaro S, Planas AM, Llop J, Ramos-Cabrer P, Justicia C, Martín A. Multimodal imaging of the role of hyperglycemia following experimental subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2024;44:726-741. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Shiferaw MY, Laeke T/Mariam T, Aklilu AT, Akililu YB, Worku BY. Diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) induced cerebral edema complicating small chronic subdural hematoma/hygroma/ at Zewuditu memorial hospital: a case report. BMC Endocr Disord. 2022;22:6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Scutca AC, Nicoară DM, Mang N, Jugănaru I, Brad GF, Mărginean O. Correlation between Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio and Cerebral Edema in Children with Severe Diabetic Ketoacidosis. Biomedicines. 2023;11:2976. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Orešković D, Madero Pohlen A, Cvitković I, Alen JF, Raguž M, Álvarez-Sala de la Cuadra A, Bazarra Castro GJ, Bušić Z, Konstantinović I, Ledenko V, Martínez Macho C, Müller D, Žarak M, Jovanov-Milosevic N, Chudy D, Marinović T. Chronic hyperglycemia and intracranial meningiomas. BMC Cancer. 2024;24:488. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Selke P, Strauss C, Horstkorte R, Scheer M. Effect of Different Glucose Levels and Glycation on Meningioma Cell Migration and Invasion. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25:10075. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Memarian S, Zolfaghari A, Gharib B, Rajabi MM. The incidence of cerebral edema in pediatric patients with diabetic ketoacidosis: a retrospective study. BMC Res Notes. 2025;18:152. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Abramo TJ, Szlam S, Hargrave H, Harris ZL, Williams A, Meredith M, Hedrick M, Hu Z, Nick T, Gonzalez CV. Bihemispheric Cerebral Oximetry Monitoring's Functionality in Suspected Cerebral Edema Diabetic Ketoacidosis With Therapeutic 3% Hyperosmolar Therapy in a Pediatric Emergency Department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2022;38:e511-e518. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Randhawa KS, Choi CB, Shah AD, Parray A, Fang CH, Liu JK, Baredes S, Eloy JA. Impact of Diabetes Mellitus on Adverse Outcomes After Meningioma Surgery. World Neurosurg. 2021;152:e429-e435. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Tenreiro K, Hatipoglu B. Mind Matters: Mental Health and Diabetes Management. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2025;110:S131-S136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Zhang Y, Tan H, Jia L, He J, Hao P, Li T, Xiao Y, Peng L, Feng Y, Cheng X, Deng H, Wang P, Chong W, Hai Y, Chen L, You C, Fang F. Association of preoperative glucose concentration with mortality in patients undergoing craniotomy for brain tumor. J Neurosurg. 2023;138:1254-1262. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Gruenbaum SE, Guay CS, Gruenbaum BF, Konkayev A, Falegnami A, Qeva E, Prabhakar H, Nunes RR, Santoro A, Garcia DP, Quiñones-Hinojosa A, Bilotta F. Perioperative Glycemia Management in Patients Undergoing Craniotomy for Brain Tumor Resection: A Global Survey of Neuroanesthesiologists' Perceptions and Practices. World Neurosurg. 2021;155:e548-e563. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Harborg S, Kjærgaard KA, Thomsen RW, Borgquist S, Cronin-Fenton D, Hjorth CF. New Horizons: Epidemiology of Obesity, Diabetes Mellitus, and Cancer Prognosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2024;109:924-935. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 26.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Bahardoust M, Mousavi S, Moezi ZD, Yarali M, Tayebi A, Olamaeian F, Tizmaghz A. Effect of Metformin Use on Survival and Recurrence Rate of Gastric Cancer After Gastrectomy in Diabetic Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Observational Studies. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2024;55:65-76. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/