Published online Feb 15, 2026. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v17.i2.112534

Revised: September 8, 2025

Accepted: December 16, 2025

Published online: February 15, 2026

Processing time: 182 Days and 1 Hours

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) is widely present in the human gastric mucosa and is closely associated with a variety of gastric diseases. Recent studies have found that H. pylori infection is closely associated with diabetic patients and may adversely affect their glucose metabolism and organ function. However, the effect of H. pylori infection on pathological changes in the body during a diabetic state remains unclear.

To investigate the effects of H. pylori infection on the physiology and pathological changes in the organs of diabetic mice.

The diabetic mice models were established using streptozotocin (STZ). The mice were infected with H. pylori through oral gavage, with their fasting blood glucose (FBG) and body weight monitored dynamically over a period of 1 to 13 months after infection. Pathological changes in major organs (including the pancreas, stomach, liver, and kidneys) were assessed, along with apoptosis levels in these tissues. The expression of H. pylori virulence factors in the liver and alterations in the intestinal microbiota were also analyzed.

H. pylori infection led to significant fluctuations in FBG in diabetic mice from the 1st to 9th month, with FBG levels remaining consistently elevated. Body weight increased gradually but remained significantly lower than that of both uninfected diabetic mice and non-diabetic controls. Pancreatic islet cell numbers decreased, accompanied by persistent inflammation and tissue damage for over 9 months. H. pylori colonized the stomach for at least 7 months, causing irreversible gastric mucosal inflammation; by the 13th month, diffuse dense inflammatory infiltration occupying the entire submucosal layer was observed. Progressive damage was observed in liver and kidney tissues, with marked expression of H. pylori virulence factors in the liver by the 9th month. Additionally, significant gut microbiota dysbiosis was observed.

The STZ-induced diabetic mouse model with H. pylori infection can significantly prolong the colonization time of H. pylori in the stomach and exacerbate the degree of damage to the stomach, liver, and kidney organs.

Core Tip: This study investigates the effects of Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection on physiological functions and multiorgan pathology in diabetic mice. By establishing diabetic mouse models and subsequently performing H. pylori gavage, we monitored dynamic changes in blood glucose, organ damage, histopathology, and gut microbiota over a 13-month infection period. These findings may provide new insights for clinical interventions in patients with comorbid diabetes and H. pylori infection.

- Citation: Yang WP, Zeng JH, Wu BL, Zhou WT, Luo JZ, Dai YY, Yang SX, Huang ZS, Huang YQ. Pathological effects of diabetic mice with Helicobacter pylori infection. World J Diabetes 2026; 17(2): 112534

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9358/full/v17/i2/112534.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4239/wjd.v17.i2.112534

Diabetes, a chronic metabolic disease, exhibits a rising incidence in China[1]. It severely compromises patients' quality of life and threatens public health security. The Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection rate in the Chinese population is approximately 50%. This pathogen is closely associated with gastrointestinal diseases, including chronic gastritis and gastric cancer[2,3]. Although research has revealed the close association between H. pylori infection and diabetes[4-7], the impact on the body resulting from diabetes and H. pylori infection is long-lasting and involves intricate pathogenesis. Therefore, there is an urgent need to establish experimental animal models to explore the relationship between diabetes and H. pylori infection. Currently, no long-term experimental data from animal studies are available to elucidate the intrinsic correlation between these two conditions. For mice that develop diabetes following pancreatic damage and are subsequently infected with H. pylori, no studies have addressed: (1) The spectrum of organ damage; (2) Organs most susceptible to pathological alterations; or (3) The temporal progression of injury severity. Therefore, the present study investigates the pathological characteristics of H. pylori infection in diabetic mice to further elucidate the relationship between H. pylori and diabetes, providing references for preventing and treating H. pylori-induced complications.

In this study, 54 male C57BL/6 mice (aged 5-6 weeks; batch No. 44829700007558) were housed under specific pathogen-free conditions and obtained from Guangdong Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology Co., Ltd. Animal license: SCXK [Yue] 2022-0063; ethics approval No. 2022092901. H. pylori strain HPBS001 was isolated, cultured, and identified in our laboratory, followed by gastric adaptation for colonization. Blood glucose test strips were purchased from Roche Diagnostics (batch No. 26020933). Streptozotocin (STZ) (C8H15N3O7) and citrate buffer components (citric acid, batch No. C10723907; sodium citrate, batch No. C10712912) were sourced from Shanghai Macklin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd.

Under light-protected conditions, Solution A (citric acid, C6H8O7; 21 g/L) and Solution B (sodium citrate dihydrate, Na3C6H5O7·2H2O; 29.4 g/L) were prepared. These solutions were mixed at specified volume ratios (1:1.32 or 1:1 v/v), and the pH of the resultant mixture was adjusted to 4.0-4.5 using a calibrated pH meter. A 0.1 mol/L citrate buffer was formulated by dissolving STZ to achieve a 5 mg/mL solution. Mice received intraperitoneal injections at 0.15 mL/10 g body weight (equivalent to 75 mg/kg STZ). Three injections, each at a dose of 75 mg/kg, can induce reversible pancreatic injury, thereby preventing experimental animals from dying prematurely due to acute hyperglycemia. The low-dose protocol only triggers pancreatic β-cell apoptosis, while most of the exocrine pancreas remains undamaged, which results in "relatively mild" overall pancreatic injury; the pancreas exhibits a state of recovery in the late stage of the experiment, which is consistent with the findings of Wang-Fischer and Garyantes[8]. The animals were divided into four groups: Normal group (n = 8), H. pylori infection group (n = 8), diabetes group (n = 8), and H. pylori-combined diabetes group (n = 29). The specific modeling methods are as follows: All mice were housed in a controlled environment (temperature: 23 ±

The above-mentioned 29 diabetic mice and mice in the H. pylori-infected mice 9 (n = 8) were fasted for 12 hours with free access to water and administered the H. pylori (HPBS001) suspension (1 × 109 colony-forming units/mL) prepared using a Brain Heart Infusion medium through gavage, with each receiving 0.5 mL. During gavage, the bacterial suspension was maintained on ice. Post-gavage, viability was verified by plating 100 μL aliquots onto Columbia blood agar plates. After gavage, mice were fasted without water access for 4 hours, and the procedure was repeated every other day for five cycles. Strain identification: Colony morphology appeared as acicular translucent forms. Gram staining was performed on the colonies followed by microscopic examination. Bacterial DNA was extracted, PCR amplification was conducted, and the presence of cytotoxin-associated gene A (CagA) was detected. Throughout this study, all experimental procedures adhered to biosafety protocols.

In the present study, diabetic mice were administered H. pylori suspension through gavage. Subsequently, their FBG levels and body weight changes were measured in the 1st, 3th, 5th, 7th, 9th, 11th, and 13th months, and the relevant data were recorded in detail.

Tissues collected from the pancreas, stomach, liver, and kidneys were immediately fixed in 4% formaldehyde (FA; HCHO) to preserve structural integrity. Samples were delivered to Services Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Wuhan, China) for processing. Tissues underwent deparaffinization with xylene (C8H10) and gradient ethanol (EtOH; C2H5OH). Cell nuclei were stained bluish-purple with hematoxylin (C16H14O6), while cytoplasm and extracellular matrix were stained eosinophilic (red/pink) with eosin (C20H8Br₄O). After dehydration and mounting, the morphological and pathological changes in the tissues were analyzed microscopically.

The collected pancreatic tissues were immediately placed in 4 °C transmission electron microscopy (TEM) fixative to preserve ultrastructural integrity. Samples were processed by Shanghai MicroPort Medical (Group) Co., Ltd. (China). Tissues were dehydrated through sequential immersion in graded ethanol (EtOH) and acetone (C3H6O), followed by metal sputter coating to enhance conductivity. Processed samples were imaged using scanning TEM.

In the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th, 5th, 6th, 7th, 9th, and 13th months after diabetic mice were administered H. pylori suspension through gavage, three randomly selected mice were euthanized by cervical dislocation after a 12-hour fasting period, and half of tissues from their stomach was immediately placed in 4% FA for subsequent histopathological examination. The other half of the collected stomach tissues was weighed and homogenized, then diluted 10-fold, 100-fold, and 1000-fold. The tissues were evenly coated on Columbia agar plates containing 10% serum, and incubated in a three-gas incubator [85% nitrogen (N2), 10% carbon dioxide (CO2), and 5% oxygen (O2)] for 72 to 96 hours. The colony morphology was observed and transparent, small colonies were counted accurately to calculate the number of H. pylori bacteria per g of gastric tissue.

The paraffin-embedded tissue blocks were delivered to Sevier Biotechnology Co., Ltd. in Wuhan, China, where the blocks were deparaffinized and rehydrated. Proteinase K (PK) was used to digest proteins in the tissue samples and expose DNA break sites, and the remaining PK was washed with phosphate-buffered saline. TUNEL staining was performed to incorporate fluorescently labeled deoxyuridine triphosphate into the DNA break sites. These samples were then washed, mounted, and prepared for microscopic observation and image collection.

Paraffin-embedded liver blocks were delivered to Sevier Biotechnology Co., Ltd. in Wuhan for dewaxing and hydration as part of antigen retrieval, which exposes the antigen epitopes. Subsequently, nonspecific binding sites were blocked, and the samples were incubated with the primary and secondary antibodies. Thereafter, the samples were stained using a diaminobenzidine reagent, and hematoxylin was applied for counterstaining. Finally, the samples were dehydrated and mounted for microscopic observation.

Sterile Eppendorf (EP) tubes and forceps were used to collect fecal samples, which were then stored at -80 °C. Samples were collected both before establishing the mouse models and at the 1st, 5th, 9th, and 13th months after model establishment. For each collection time point, three EP tubes were used, with each tube containing 8-9 fecal pellets. Subsequently, the samples were sent to Fengzi Biomedical Technology Co., Ltd. (Nanjing, China) for 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene sequencing. There, genomic DNA was extracted from the samples using a DNA extraction kit (Omega Bio-tek, Norcross, GA, United States). The hypervariable regions of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene were amplified and sequenced using the MiSeq platform. Analysis of the microbiome’s beta diversity and canonical correspondence analysis (CCA) revealed significant differences in microbiota composition. The α-diversity, including species richness and the diversity of undi

All results are expressed as mean ± SD. For comparisons between two groups, an independent samples t-test was used. For comparisons among multiple groups, a two-way ANOVA was employed to assess the main effects of group and time as well as their interaction, followed by Bonferroni correction to control the family-wise error rate. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 26.0, with P < 0.05 defined as statistically significant. The graphs were generated using GraphPad Prism 9.5 (GraphPad Software, Boston, MA, United States).

Colonies of H. pylori observed on solid medium were pinhead-sized, semi-transparent, with neat edges, smooth surfaces, and uniform textures. Gram staining and microscopic examination revealed slightly curved bacterial cells with a negative Gram stain reaction, appearing red. PCR detection confirmed successful extraction of bacterial DNA, and amplification of the CagA gene using PCR technology yielded specific bands at the expected molecular weight position upon electrophoresis. These results confirmed that the strain carries the CagA gene (Figure 1).

H. pylori-infected diabetic mice exhibited fluctuating FBG levels beginning at month 1 post-infection. The mean ± SD is shown in Table 1. By month 5, the mean FBG level peaked at 21.13 mmol/L. At month 7, FBG decreased to 17.00 mmol/L, subsequently returning to near month-1 levels (11.33 mmol/L) by month 9. By month 13, FBG approached levels observed in normal mice (Figure 2A and B). Compared to diabetic-only controls, H. pylori-infected diabetic mice showed significantly greater FBG fluctuations, indicating potential exacerbation of diabetes progression by H. pylori infection. After H. pylori infection in diabetic mice, in the 1st month, the number of pancreatic islet cells decreased, and the damage intensified. Both the volume and number of cells showed a downward trend, with expanded intercellular spaces, partial cell necrosis, vacuolar degeneration, and cell death, resulting in a hollow appearance of the islets (Figure 2C). In the 5th month, the islet structure became further disorganized, with cells disordered in their arrangement, and significant infiltration of inflammatory cells such as lymphocytes and monocytes, a result similar to that of the 1st month. By the 9th month, the islet volume increased, and the number of islet cells showed an upward trend. By the 13th month, islets significantly increased, but their edges remained irregular. The normal organization of the islet had not yet been restored, with unclear boundaries and disordered arrangement of pancreatic cells. At the 5th month after diabetes mellitus induction, TEM revealed a significant decrease in zymogen granule number in diabetic mice compared with age-matched normal control mice (Figure 2D).

| Month | Group | |||

| Normal (n = 8) | Helicobacter pylori (n = 8) | Diabetes (n = 8) | Helicobacter pylori + diabetes (n = 8) | |

| 1 | 7.08 ± 0.41 | 6.72 ± 0.74 | 14.25 ± 1.56 | 13.48 ± 3.12 |

| 3 | 7.07 ± 1.23 | 6.98 ± 0.64 | 22.18 ± 1.77 | 14.98 ± 5.24 |

| 5 | 7.37 ± 0.87 | 7.27 ± 0.63 | 22.03 ± 1.99 | 21.13 ± 5.11 |

| 7 | 6.87 ± 1.65 | 6.78 ± 0.81 | 14.08 ± 3.29 | 17.01 ± 6.45 |

| 9 | 6.77 ± 1.35 | 7.23 ± 0.79 | 9.42 ± 2.27 | 11.33 ± 6.54 |

| 11 | 7.03 ± 0.43 | 6.72 ± 0.66 | 7.97 ± 1.54 | 10.48 ± 1.64 |

| 13 | 6.80 ± 0.97 | 7.32 ± 0.79 | 6.88 ± 0.89 | 7.83 ± 1.14 |

From month 1 to 13 post-infection, all experimental groups exhibited increasing body weight, yet H. pylori-infected diabetic mice consistently weighed less than diabetic-only controls. This weight deficit was more pronounced compared to normal mice before month 6 (Figure 3A and B). The mean ± SD is shown in Table 2. The severity of chronic gastric mucosal inflammation was quantified and scored using the modified Sydney system combined with literature consensus[11], with the infiltration depth of lymphocytes and plasma cells as the core indicators. The specific scoring criteria are as follows: Score 0 (Absent): No or a minimal number of chronic inflammatory cells infiltrate the mucosa, with a normal distribution. Score 1 (Mild): Chronic inflammatory cells are scattered in the superficial layer of the mucosa, not exceeding 1/3 of the mucosal thickness. Score 2 (Moderate): Chronic inflammatory cells are diffusely distributed in the superficial and deep layers of the mucosa, reaching 2/3 of the mucosal thickness but not involving the entire layer; lymphoid follicles may be present. Score 3 (Severe): A large number of chronic inflammatory cells diffusely infiltrate the entire layer of the mucosa with dense distribution, which may be accompanied by significant lymphoid follicle formation. At the 13th month, no obvious inflammatory infiltration was observed in the normal group, whereas all other groups showed submucosal penetration of inflammatory cells (consistent with severe gastritis). Notably, the diabetes combined with H. pylori infection group had already developed severe gastritis as early as month 1, with progressively worsening inflammation that peaked at month 13-significantly more severe than all control groups.

| Month | Group | |||

| Normal (n = 8) | Helicobacter pylori (n = 8) | Diabetes (n = 8) | Helicobacter pylori + diabetes (n = 8) | |

| 1 | 27.12 ± 0.98 | 24.82 ± 0.68 | 22.98 ±1.18 | 19.31 ± 1.33 |

| 3 | 30.15 ± 0.85 | 26.53 ± 0.38 | 25.13 ± 0.52 | 22.48 ± 1.49 |

| 5 | 30.58 ± 0.73 | 26.58 ± 0.62 | 25.05 ± 0.41 | 23.37 ± 1.56 |

| 7 | 30.65 ± 0.88 | 27.15 ± 0.86 | 25.68 ± 0.76 | 23.61 ± 1.43 |

| 9 | 30.90 ± 0.87 | 28.43 ± 0.49 | 25.15 ± 1.82 | 25.83 ± 0.94 |

| 11 | 31.02 ± 0.73 | 29.00 ± 0.48 | 26.82 ± 0.79 | 25.94 ± 1.65 |

| 13 | 32.06 ± 1.09 | 30.70 ± 0.95 | 28.03 ± 0.87 | 27.24 ± 1.79 |

In the H. pylori-infected diabetic mouse model, histopathological changes in gastric mucosal tissues were observed as follows: During the 1st month post-infection, superficial gastritis was evident, characterized by a mild infiltration of inflammatory cells within the mucosal layer. These infiltrates were predominantly neutrophils, accompanied by a small number of lymphocytes, with partial extension into the submucosal layer. By the 5th month, a marked increase in inflammatory cell infiltration was noted in the submucosa, primarily consisting of mononuclear cells (predominantly lymphocytes and plasma cells) along with fibrous tissue hyperplasia. Inflammatory cells infiltrated the submucosa, while fibroblast proliferation was observed in both the lamina propria of the gastric mucosa and the submucosal layer. At the 9th month, significant inflammatory cell infiltration was detected in the gastric mucosa, mainly composed of lymphocytes and plasma cells. The number of inflammatory cells in the submucosa and perivascular regions increased, accompanied by extensive fibroblast proliferation, with inflammation extending to the gastric muscular layer. By the 13th month, chronic atrophic gastritis had developed, presenting with late-stage inflammatory manifestations dominated by lymphocytes and fibroblasts. The highest density of inflammatory cells was observed in the mucosal and submucosal layers, accompanied by prominent fibroblastic proliferation. Additionally, spherical binucleated cells and atypical hyperplasia were identified in the gastric muscular layer (Figure 3C). Gastric H. pylori colonization peaked at month 1, with a secondary peak at month 5. After month 9, bacterial loads declined to undetectable levels by plate counting (Figure 3D).

These findings indicate that H. pylori infection induces progressive pathological changes in the gastric mucosa of diabetic mice. Initial changes were characterized by mild inflammatory cell infiltration; despite a reduction in H. pylori colonization at later stages, persistent increases in inflammatory cell infiltration and fibroblast proliferation were still observed. This suggests that H. pylori infection causes sustained and irreversible damage to the gastric mucosa in diabetic mice.

The severity of liver inflammation was quantitatively evaluated using the internationally accepted and widely recognized liver inflammatory activity grading system[12]. The grading criteria are as follows: G0: No inflammation; G1: Inflammation confined to the portal areas; G2: Mild inflammation in the lobules without hepatocyte necrosis, or mild piecemeal necrosis accompanied by hepatocyte necrosis or acidophilic bodies in the lobules; G3: Moderate piecemeal necrosis, with severe focal hepatocyte necrosis in the lobules; G4: Severe piecemeal necrosis, with confluent necrosis (including bridging necrosis) observed in the lobules. At the 13th month, no obvious liver inflammation was observed in mice of the normal group; the liver inflammation in the H. pylori-infected group reached Grade G3; the liver inflammation in the diabetic group reached Grade G3 at the 13th month; for the diabetic mice combined with H. pylori infection group, liver inflammation first appeared at the 5th month (reaching Grade G2), progressed to Grade G3 at the 9th month, and further developed to Grade G4 at the 13th month (Figure 4).

The severity of renal inflammation was graded using the modified Banff criteria combined with the pathological features of acute interstitial nephritis[13]. The grading standards are as follows: Grade 1 (mild inflammation): A small number of inflammatory cells infiltrate the renal interstitium [≤ 10 cells per high-power field (HPF)], which are confined to the perivascular area or renal tubular interstitium, with no obvious renal tubular injury. Grade 2 (Moderate inflammation): The degree of inflammatory cell infiltration is significantly increased compared with Grade 1 (11-30 cells per HPF), with diffuse distribution in the renal interstitium, accompanied by focal tubulitis (i.e., inflammatory cells invading renal tubular epithelium) or mild degeneration of tubular epithelium (e.g., vacuolization). Grade 3 (severe inflammation): A large number of inflammatory cells infiltrate the renal interstitium (> 30 cells per HPF), which may be accompanied by renal tubular injury; in addition, eosinophil or plasma cell infiltration may be present, along with extensive renal tubular damage (e.g., tubular atrophy, brush border loss, or necrosis). At the 13th month, no obvious inflammation was observed in the normal group and the H. pylori-infected group. The diabetic group showed a small accumulation of inflammatory cells, reaching moderate inflammation (Grade 2). For the diabetic mice combined with H. pylori infection group, severe inflammation (Grade 3) was observed at the 9th month; by the 13th month, a massive accumulation of inflammatory cells was noted, which remained consistent with severe inflammation (Figure 4).

In diabetic mice infected with H. pylori, at the 1st month, due to the short duration, no significant pathological changes were observed in the liver tissue. In the 5th month, inflammatory responses were evident, with inflammatory cells aggregating into clusters. Some hepatocytes showed ballooning degeneration, with a significant increase in their size and sparse cytoplasm, and a reduction in staining intensity. By the 9th month, a large number of inflammatory cells infiltrated and aggregated into clusters, mainly consisting of lymphocytes and plasma cells, leading to an obscured liver tissue structure. In the 13th month, the number of liver cysts significantly increased, inflammatory cells densely aggregated, the hepatic cord structure became unclear, and the inflammatory lesions were prominent. Renal tissue: At the 1st, 5th, and 9th months, the pathological changes were not significant. However, in the 13th month, the glomerular volume significantly expanded, with an increase in area and a marked thickening of the basement membrane. There was also significant fibroblast proliferation in the renal interstitium, with infiltration by a large number of inflammatory cells (Figure 4). Compared to diabetic mice without H. pylori infection, diabetic mice with a 9-month course of intragastric H. pylori infection exhibited more severe pathological changes and inflammation in both the liver and kidneys. Both organs showed pathological alterations, with liver damage being more prominent and inflammation developing earlier. This may be associated with the fact that H. pylori or its virulence factors are more easily transmitted to the liver via the digestive system.

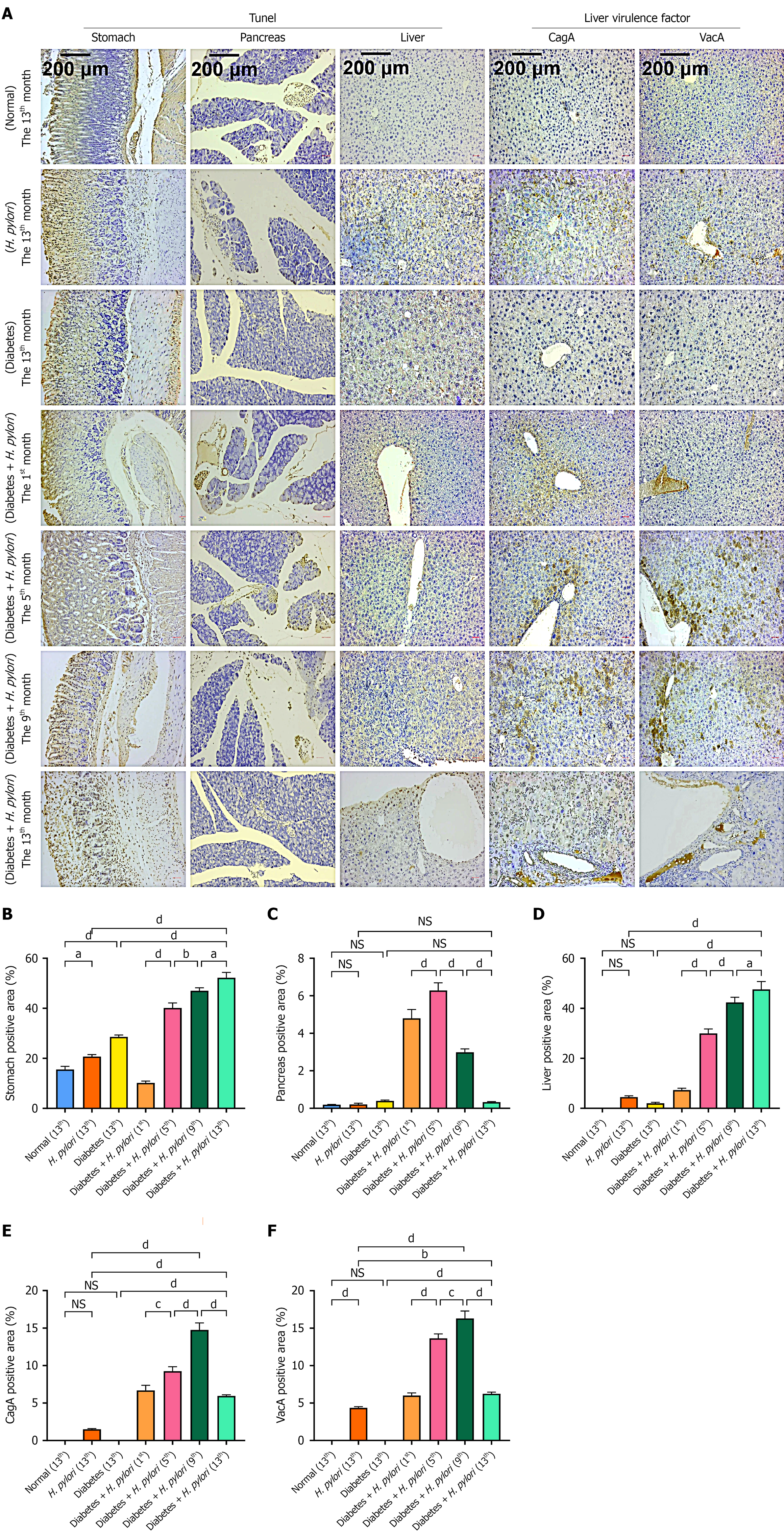

TUNEL staining was performed on the gastric, pancreatic, and hepatic tissues of H. pylori-infected diabetic mice, along with measurement of H. pylori virulence factors in the liver (Figure 5), using ImageJ software for semi-quantitative measurement. The results revealed that in the pancreas, in the 1st month, all islets were positive, with severe apoptosis of islet cells. In the 5th month, apoptosis of pancreatic cells adjacent to the islets was observed. In the 9th month, apoptosis in the islets remained severe. In the 13th month, no significant apoptosis was observed. In the liver and kidneys, the rate of cell apoptosis increased with the duration of infection. Apoptotic cells in the gastric tissue significantly increased in the 1st month, with more than half of the mucosal layer affected. In the 5th month, the number further increased, affecting more than two-thirds of the layer. In the 9th month, the apoptosis rate significantly rose, and apoptotic cells nearly covered the entire mucosal layer. In the 13th month, apoptotic cells had accumulated throughout the entire field of view, involving both the mucosal and submucosal layers. The apoptosis in the liver tissue, similar to that in the gastric tissue, became increasingly severe with time. Compared with diabetic mice, H. pylori-infected diabetic mice exhibited more severe apoptosis in gastric, pancreatic, and hepatic cells. H. pylori virulence factor assays showed that the virulence factors CagA and VacA, detectable as brownish-yellow staining, were present at all time points from the 1st to the 13th month. In the 5th and 9th months, the staining was more pronounced, particularly in the cytoplasm, mainly localized to the hepatocyte cell membrane and cytoplasm. The virulence factors of H. pylori, such as CagA, can enter the liver through exosome-mediated pathways and be absorbed by hepatocytes[14], Thereby, they persist in the liver for an extended period.

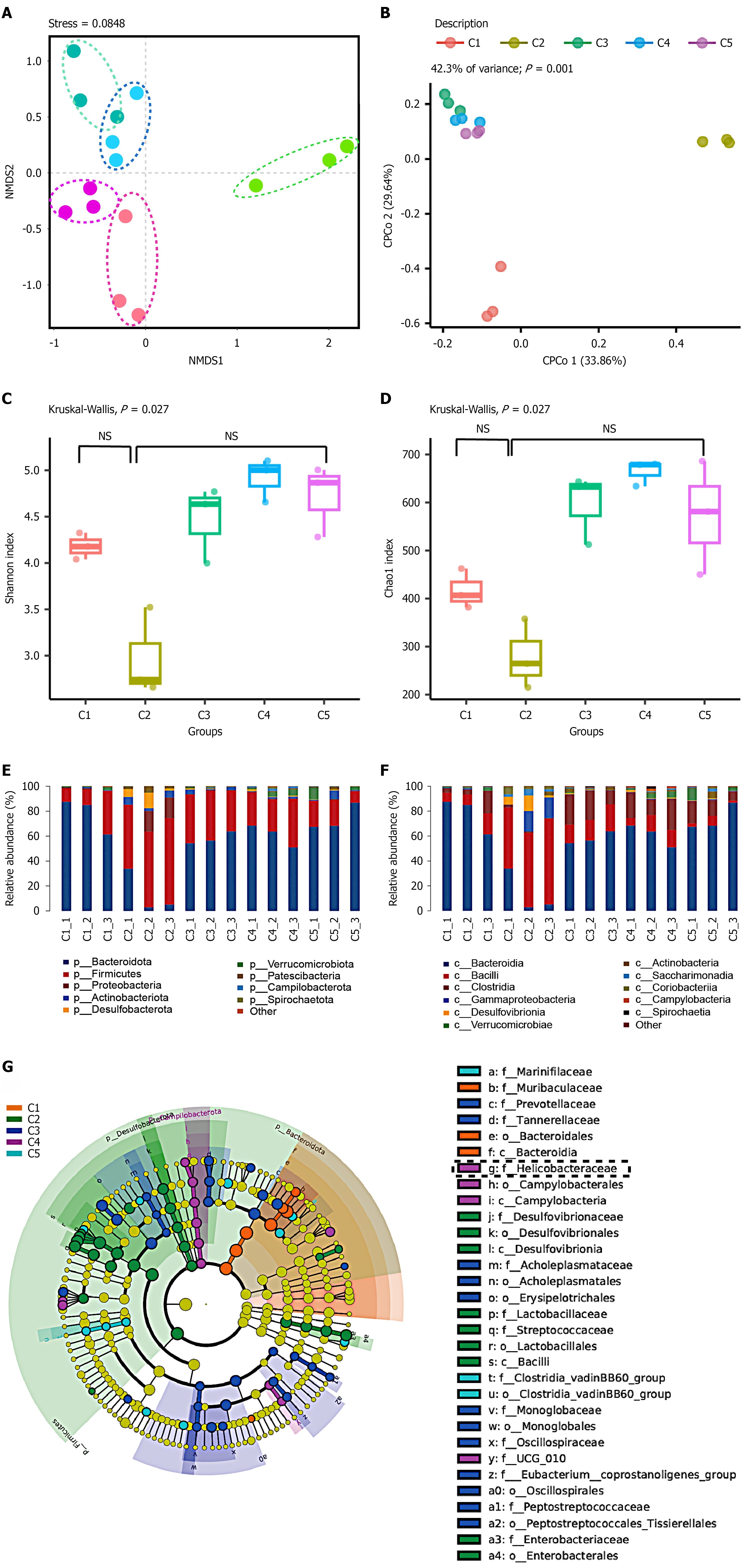

16S rRNA sequencing and bioinformatics analyses were performed on the fecal samples from diabetic mice infected with H. pylori. The results showed that H. pylori infection significantly disrupted the gut microbiota structure in diabetic mice, potentially promoting the proliferation of pathogenic bacteria while inhibiting the growth of beneficial bacteria by regulating the intestinal microenvironment and immune response. Beta diversity of the microbiome and CCA analyses (Figure 6A and B) revealed that significant differences in microbiota distribution were observed between the pre-infection and post-infection time points in the 1st, 5th, 9th, and 13th months (C1-C5), with the contrast between pre- and post-gavage particularly pronounced (C1 vs C2, 3, 4, 5). At different time points, no significant differences in α-diversity were observed between groups, but significant differences in overall microbial community composition were detected (Figure 6C and D). In the 1st month (C2), the abundance (assessed by the Chao1 index) and diversity (represented by the Simpson index) of the gut microbiota showed a declining trend initially. However, as FBG levels and H. pylori colonization density decreased, these indicators gradually improved. Taxonomic analyses evaluated the relative abundance of species at the phylum and genus levels (Figure 6E and F). Before infection (C1), the gut microbiota of the mice was primarily composed of Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, and Actinobacteria. In the 1st month post-infection (C2), the abundance of the harmful bacterium Bacteroidetes increased, with this trend continuing in later stages. LefSe analysis (Figure 6G) showed that after H. pylori-suspension gavage (C1 vs C2, 3, 4, and 5), the gut microbiota was significantly disrupted. The abundance of other potentially harmful bacterial genera, such as Streptococcus, was significantly higher than in other groups. As FBG levels and H. pylori colonization decreased (C4 and C5), the gut microbiota of the mice gradually returned to a balanced state.

In the present study, STZ was used to induce diabetes in mice by damaging pancreatic β-cells[15-17]. After modeling, the diabetic mice were administered H. pylori suspension through gavage, and the pathological characteristics were observed at different time points over a 13-month period. The results revealed widespread pathological effects, including fluctuations in FBG levels, changes in body weight, exacerbation of pancreatic cell and organ damage, increased apoptosis, significant effects of virulence factors, and gut microbiota dysbiosis.

After H. pylori infection, both the FBG levels and pancreatic function had improved by the 9th month post-infection, and were nearly normal by the 13th month. This may be attributed to the STZ induction, where STZ was administered only three times at a dose of 75 mg/kg each. As the low-dose treatment resulted in mild damage without continuous injury, pancreatic tissue or islet cell damage could be repaired over a period of about 5-13 months. This result is in agreement with that of Wang-Fischer et al[8], where some models also showed recovery beginning in the 36th week post-STZ induction.

By the 9th month post-infection, although the pathological examination of the pancreas and FBG levels showed significant improvement, both conditions remained relatively severe. Compared to uninfected diabetic mice, H. pylori-infected diabetic mice showed greater blood glucose variability, suggesting H. pylori affects fasting glucose stability in STZ-induced models. Infected diabetic mice trended toward weight gain, with a more pronounced weight difference vs. normal groups at 1 month post-infection, linked to H. pylori colonization and pancreatic damage. Although H. pylori colonization was undetectable by the 9th month, gastric mucosal inflammation continued to progress by the 13th month-indicating that chronic tissue damage persisted despite the reduction in bacterial load. This finding has significant implications for diabetic patients achieving H. pylori eradication, as inflammation may persist after bacterial clearance.

Diabetic mice infected with H. pylori exhibited liver and kidney tissue damage, with pathological progression similar to that of gastric mucosal injury, and the degree of inflammation progressively worsened. Particularly in the liver, the inflammatory lesions and tissue damage at 9 months were significantly more severe than those at 5 months. Although blood glucose levels gradually recovered and the colonization level of H. pylori decreased after 9 months, liver damage further intensified by 13 months, accompanied by the formation of hepatic cysts. The kidneys also showed significant inflammatory infiltration at 13 months, indicating that early damage had resulted in irreversible effects. Diabetic mice infected with H. pylori also exhibited damage in other organs, a result similar to the finding of Pan et al[18], who reported that H. pylori may cause kidney damage.

Zhang et al[14] reported that H. pylori can induce hepatocyte proliferation, migration, and inflammatory responses. Goo et al[19] found that H. pylori infection can promote the development of liver fibrosis. Therefore, the present study also focuses on the effects of H. pylori infection on organ apoptosis and virulence factors in diabetic mice. TUNEL assay results showed that the number of apoptotic cells in organs such as the stomach, liver, and kidneys of diabetic mice infected with H. pylori significantly increased over time. Although the colonization level of H. pylori decreased by the 9th month, the blood glucose level recovered by the 13th month. The detection of H. pylori virulence factors CagA and VacA in liver tissue revealed that although the levels of these virulence factors in the liver decreased after 9 months, they persisted in liver tissue. These results suggest that for patients with diabetes who are infected with H. pylori, it is crucial to eradicate H. pylori, closely monitor liver and kidney status, and take timely and effective medical measures.

The colonization of H. pylori in diabetic mice is correlated with FBG levels, and it can persist for up to 7 months, which is approximately 1 month longer than the usual colonization period (4-6 months). This indicates that H. pylori exhibits a longer colonization duration in the stomach of diabetic mice, which may be associated with the impaired integrity of the gastric mucosal barrier in diabetic mice. Diabetic mice may be accompanied by immune dysfunction, such as abnormal neutrophil function and disordered T-cell response by Alba-Loureiro et al[20] and Martinez et al[21], which all impair the clearance of H. pylori. Diabetic mice often exhibit gastric mucosal changes, including mucosal barrier disruption and gastric microenvironment alteration by Thaiss CA et al[22], and these changes create favorable conditions for the colonization of H. pylori. According to Azami et al’s report[23], H. pylori infection may be associated with metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance. H. pylori was undetectable by the plate method at the 9th month, but it was still detected in the gut microbiota at the 13th month, and organ damage was more severe, indicating that the damage previously incurred was irreversible. Therefore, for diabetic patients infected with H. pylori, in addition to regular FBG management, it is crucial to involve the radical treatment of H. pylori infection to mitigate its potential impact on the progression of diabetes.

H. pylori infection can trigger inflammatory responses[24], alter the gut microbiota[25], and impair the body’s immune function[26]. In the present study, through 16S rRNA sequencing and bioinformatics analyses, we found that H. pylori infection significantly disrupted the gut microbiota structure in diabetic mice, promoted the proliferation of pathogenic bacteria, and inhibited the growth of beneficial bacteria. For instance, the abundances of Bacteroides and Streptococcus were increased; moreover, elevated levels of these two genera may impair intestinal barrier integrity, leading to the leakage of endotoxins and other toxic substances into the bloodstream. They also disrupt the metabolic balance of the gut microbiota and trigger chronic low-grade inflammatory responses. Additionally, the potential functional impact of increased Bacteroides abundance in diabetic hosts may exacerbate systemic inflammation, while the over proliferation of streptococci may increase the risk of local or systemic infections. This may be related to the changes in the intestinal microenvironment and immune response abnormalities induced by H. pylori infection.

In summary, we conducted a 13-month longitudinal study to investigate the effects of H. pylori infection in STZ-treated mice, with monitoring of FBG changes, histopathological alterations in the stomach, liver, and kidneys, and gut microbiota dynamics. As previously noted, the diabetes induction protocol employed herein-three injections of STZ at 75 mg/kg-induced acute and reversible pancreatic injury, with hyperglycemia persisting for 9 months and FBG levels normalizing by the 13th month. Nevertheless, by the 9th month, H. pylori-infected mice exhibited typical pathological damage to the stomach and liver, characterized by dense infiltration of inflammatory cells (neutrophils and lymphocytes). At this time point, H. pylori colonization levels had declined below the detection limit, yet organ damage continued to progress. These observations confirm that early organ injury induced by H. pylori infection in STZ-treated mice is irreversible. Collectively, our findings demonstrate that even when pancreatic injury is reversible and FBG levels return to normal, H. pylori infection still exacerbates pathological damage to the stomach, liver, and kidneys in STZ-treated mice.

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support provided by Youjiang Medical University for Nationalities in conducting this research.

| 1. | Xu Y, Lu J, Li M, Wang T, Wang K, Cao Q, Ding Y, Xiang Y, Wang S, Yang Q, Zhao X, Zhang X, Xu M, Wang W, Bi Y, Ning G. Diabetes in China part 1: epidemiology and risk factors. Lancet Public Health. 2024;9:e1089-e1097. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Cao X, Yang Y, Zhang Y, Ji R, Zhao X, Zheng W, Yang A. Impact of Helicobacter pylori on the gastric microbiome in patients with chronic gastritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis protocol. BMJ Open. 2023;13:e050476. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ma D, Meng FD. [Diagnosis and treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection and early gastric cancer]. Zhonghua Nei Ke Za Zhi. 2020;59:392-394. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Zhou X, Zhang C, Wu J, Zhang G. Association between Helicobacter pylori infection and diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2013;99:200-208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kayar Y, Pamukçu Ö, Eroğlu H, Kalkan Erol K, Ilhan A, Kocaman O. Relationship between Helicobacter pylori Infections in Diabetic Patients and Inflammations, Metabolic Syndrome, and Complications. Int J Chronic Dis. 2015;2015:290128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Li Z, Zhang J, Jiang Y, Ma K, Cui C, Wang X. Association of Helicobacter pylori infection with complications of diabetes: a single-center retrospective study. BMC Endocr Disord. 2024;24:152. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Mansori K, Moradi Y, Naderpour S, Rashti R, Moghaddam AB, Saed L, Mohammadi H. Helicobacter pylori infection as a risk factor for diabetes: a meta-analysis of case-control studies. BMC Gastroenterol. 2020;20:77. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Wang-Fischer Y, Garyantes T. Improving the Reliability and Utility of Streptozotocin-Induced Rat Diabetic Model. J Diabetes Res. 2018;2018:8054073. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 12.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Saadane A, Lessieur EM, Du Y, Liu H, Kern TS. Successful induction of diabetes in mice demonstrates no gender difference in development of early diabetic retinopathy. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0238727. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Furman BL. Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetic Models in Mice and Rats. Curr Protoc. 2021;1:e78. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 515] [Article Influence: 103.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 11. | Dixon MF, Genta RM, Yardley JH, Correa P. Classification and grading of gastritis. The updated Sydney System. International Workshop on the Histopathology of Gastritis, Houston 1994. Am J Surg Pathol. 1996;20:1161-1181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3221] [Cited by in RCA: 3624] [Article Influence: 120.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (6)] |

| 12. | Shu X, Sun H, Yang X, Jia Y, Xu P, Cao H, Zhang K. Correlation of effective hepatic blood flow with liver pathology in patients with hepatitis B virus. Liver Res. 2021;5:243-250. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Al-Othman YA, Metcalf BD, Kroneman O, Gold JM, Zarouk S, Li W, Kanaan HD, Zhang PL. Grading T Lymphocyte-Mediated Acute Interstitial Nephritis Following Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 2025;55:172-178. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Zhang J, Ji X, Liu S, Sun Z, Cao X, Liu B, Li Y, Zhao H. Helicobacter pylori infection promotes liver injury through an exosome-mediated mechanism. Microb Pathog. 2024;195:106898. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Nikolakopoulou P, Chatzigeorgiou A, Kourtzelis I, Toutouna L, Masjkur J, Arps-Forker C, Poser SW, Rozman J, Rathkolb B, Aguilar-Pimentel JA; German Mouse Clinic Consortium, Wolf E, Klingenspor M, Ollert M, Schmidt-Weber C, Fuchs H, Gailus-Durner V, Hrabe de Angelis M, Tsata V, Monasor LS, Troullinaki M, Witt A, Anastasiou V, Chrousos G, Yi CX, García-Cáceres C, Tschöp MH, Bornstein SR, Androutsellis-Theotokis A. Streptozotocin-induced β-cell damage, high fat diet, and metformin administration regulate Hes3 expression in the adult mouse brain. Sci Rep. 2018;8:11335. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Elsner M, Guldbakke B, Tiedge M, Munday R, Lenzen S. Relative importance of transport and alkylation for pancreatic beta-cell toxicity of streptozotocin. Diabetologia. 2000;43:1528-1533. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 201] [Cited by in RCA: 213] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Lennikov A, ElZaridi F, Yang M. Modified streptozotocin-induced diabetic model in rodents. Animal Model Exp Med. 2024;7:777-780. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Pan W, Zhang H, Wang L, Zhu T, Chen B, Fan J. Association between Helicobacter pylori infection and kidney damage in patients with peptic ulcer. Ren Fail. 2019;41:1028-1034. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Goo MJ, Ki MR, Lee HR, Yang HJ, Yuan DW, Hong IH, Park JK, Hong KS, Han JY, Hwang OK, Kim DH, Do SH, Cohn RD, Jeong KS. Helicobacter pylori promotes hepatic fibrosis in the animal model. Lab Invest. 2009;89:1291-1303. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Alba-Loureiro TC, Munhoz CD, Martins JO, Cerchiaro GA, Scavone C, Curi R, Sannomiya P. Neutrophil function and metabolism in individuals with diabetes mellitus. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2007;40:1037-1044. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 198] [Cited by in RCA: 230] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 21. | Martinez N, Ketheesan N, Martens GW, West K, Lien E, Kornfeld H. Defects in early cell recruitment contribute to the increased susceptibility to respiratory Klebsiella pneumoniae infection in diabetic mice. Microbes Infect. 2016;18:649-655. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Thaiss CA, Levy M, Grosheva I, Zheng D, Soffer E, Blacher E, Braverman S, Tengeler AC, Barak O, Elazar M, Ben-Zeev R, Lehavi-Regev D, Katz MN, Pevsner-Fischer M, Gertler A, Halpern Z, Harmelin A, Aamar S, Serradas P, Grosfeld A, Shapiro H, Geiger B, Elinav E. Hyperglycemia drives intestinal barrier dysfunction and risk for enteric infection. Science. 2018;359:1376-1383. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 416] [Cited by in RCA: 680] [Article Influence: 85.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Azami M, Baradaran HR, Dehghanbanadaki H, Kohnepoushi P, Saed L, Moradkhani A, Moradpour F, Moradi Y. Association of Helicobacter pylori infection with the risk of metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2021;13:145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Wei YF, Li X, Zhao MR, Liu S, Min L, Zhu ST, Zhang ST, Xie SA. Helicobacter pylori disrupts gastric mucosal homeostasis by stimulating macrophages to secrete CCL3. Cell Commun Signal. 2024;22:263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Zang H, Wang J, Wang H, Guo J, Li Y, Zhao Y, Song J, Liu F, Liu X, Zhao Y. Metabolic alterations in patients with Helicobacter pylori-related gastritis: The H. pylori-gut microbiota-metabolism axis in progression of the chronic inflammation in the gastric mucosa. Helicobacter. 2023;28:e12984. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Chen D, Wu L, Liu X, Wang Q, Gui S, Bao L, Wang Z, He X, Zhao Y, Zhou J, Xie Y. Helicobacter pylori CagA mediated mitophagy to attenuate the NLRP3 inflammasome activation and enhance the survival of infected cells. Sci Rep. 2024;14:21648. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/