Published online Feb 15, 2026. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v17.i2.112500

Revised: October 16, 2025

Accepted: December 18, 2025

Published online: February 15, 2026

Processing time: 192 Days and 2.9 Hours

Diabetic kidney disease (DKD) continues to pose a substantial public health challenge, in which cellular senescence is recognized as a pivotal driver of disease progression. While formononetin (FN) has been documented to exhibit anti-senescence properties, its potential as a therapeutic agent for DKD and the mo

To evaluate the efficacy of FN using an in vitro model of high glucose (HG)-induced injury in MPC-5 podocytes. Transcriptomic profiling was employed to assess the influence of FN on global gene expression and to identify key signaling pathways affected by FN treatment. Furthermore, we sought to investigate the anti-senescence effects of FN and its regulatory role in the p53 signaling pathway in vitro.

To elucidate the functional role of MDM2 in the anti-senescence mechanism of FN, MDM2 expression was silenced in MPC-5 cells using gene-specific knockdown. Finally, a mouse model of DKD was generated by combining a high-fat diet with intraperitoneal streptozotocin injections, and the therapeutic as well as anti-senescence effects of FN were evaluated in vivo.

In the HG-induced MPC-5 cell model, FN treatment significantly enhanced cell viability and reduced the secretion of senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) factors in the supernatant. Transcriptomic analysis revealed the p53 signaling pathway as a central target of FN under HG conditions. FN treatment markedly suppressed β-galactosidase (β-GAL) activity, upregulated the expression of MDM2 and CCND1, downregulated the expression of p53 and p21, and inhibited p53 transcriptional activity in MPC-5 cells. These protective effects were abrogated upon MDM2 silencing. In DKD mice, FN administration improved renal function, alleviated histopathological damage, reduced renal SASP levels and β-GAL activity, and normalized the expression of key proteins in the p53 pathway.

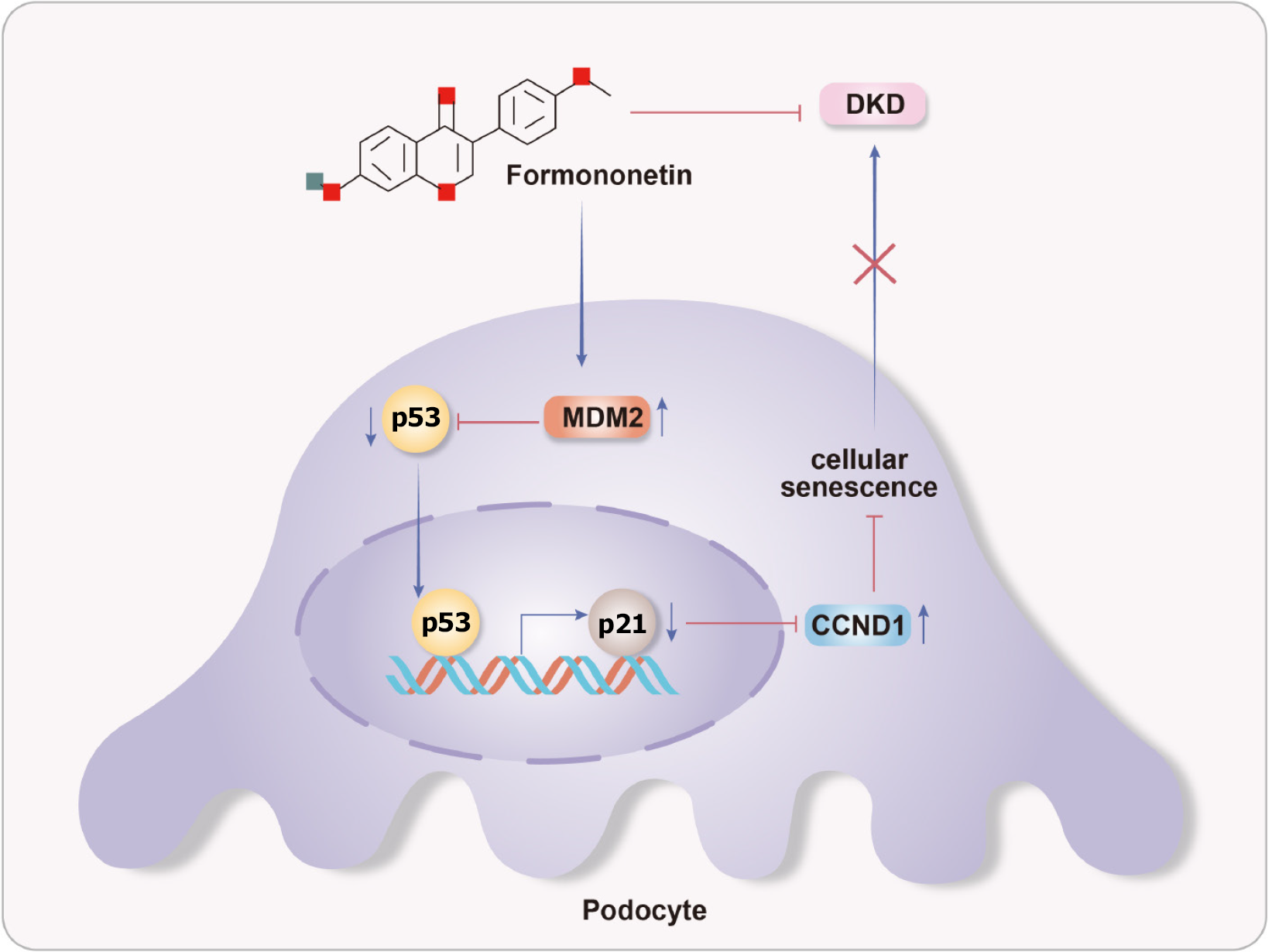

Our findings demonstrate that FN confers significant therapeutic benefits against DKD in both cellular and animal models. The mechanism underlying these benefits involves the delay of cellular senescence through suppression of the p53 signaling pathway.

Core Tip: Transcriptomic profiling identified the p53 signaling pathway as the key mechanism through which formononetin (FN) alleviates diabetic kidney disease (DKD). FN upregulates MDM2 expression, thereby inhibiting p53 transcriptional activity—as confirmed by dual-luciferase reporter assay—and downregulating p21, leading to reduced senescence markers (β-galactosidase and senescence-associated secretory phenotype factors) in both podocytes and DKD mice. Notably, MDM2 gene silencing abrogates the anti-senescent effects of FN, establishing MDM2 as essential to its action. Overall, FN improves renal function and pathology by targeting the p53/MDM2/p21 axis to attenuate cellular senescence.

- Citation: Ji Y, Liu RX, He PY, Zhou YM, Li YC, Guo J, Nie B, Liu YN, Liu WJ. Formononetin inhibits p53 signaling pathway activation to delay cellular senescence and ameliorates diabetic kidney disease. World J Diabetes 2026; 17(2): 112500

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9358/full/v17/i2/112500.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4239/wjd.v17.i2.112500

Diabetic kidney disease (DKD), a major microvascular complication of diabetes, affects approximately 20%-40% of diabetic individuals[1]. Epidemiological studies indicate a continuously rising prevalence of DKD in China, presenting a substantial public health burden[2]. The onset of DKD is typically insidious, with most patients exhibiting no specific clinical symptoms during early stages. As the disease progresses, however, hypertension, limb edema, and proteinuria frequently develop. Notably, proteinuria not only signifies disease advancement but also perpetuates a “proteinuria-nephrotoxicity” vicious cycle by promoting tubulointerstitial injury and glomerulosclerosis, thereby accelerating the decline of renal function[3]. Current clinical management adopts a multi-target strategy, emphasizing strict glycemic control, blood pressure regulation, and maintenance of internal homeostasis to delay renal deterioration. While existing therapies effectively slow disease progression, their long-term utility is often limited by adverse effects and the de

Podocytes, situated on the outer surface of the glomerular basement membrane, are essential components of the glomerular filtration barrier. Injury to these cells is recognized as a pivotal mechanism driving the initiation and pro

The anti-senescence potential of natural products derived from traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) is increasingly recognized. For instance, icariin has been shown to inhibit renal cell senescence and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) by modulating multiple senescence-related pathways, thereby mitigating DKD progression[9,10]. Similarly, salidroside alleviates HG-induced podocyte senescence and apoptosis through its anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activities[11-13]. Other natural compounds, including emodin[14], berberine[15], and tea polyphenols[16], have also demonstrated efficacy in improving DKD outcomes by targeting cellular senescence. Investigating the mechanisms through which TCM-derived natural products counteract podocyte senescence may thus provide valuable insights for novel DKD interventions.

Formononetin (FN), a bioactive isoflavone isolated from Astragalus membranaceus, is known for its antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties[17]. Previous studies have demonstrated that FN attenuates renal tubular injury and mitochondrial dysfunction in DKD models. Specifically, FN reduces renal interstitial fibrosis by suppressing Smad3 expression and extracellular matrix deposition in db/db mice[18], and it restores mitochondrial dynamics (e.g., regulating Drp1, Fis1, and Mfn2) while inhibiting apoptosis via the Sirt1/PGC-1α pathway in streptozotocin (STZ)-induced diabetic rats[19]. Furthermore, in HG-stimulated glomerular mesangial cells, FN activates the Nrf2/ARE signaling pathway in a Sirt1-dependent manner, mitigating oxidative stress and reducing expression of fibrotic markers such as fibronectin and ICAM-1[20]. Despite these documented renoprotective effects, it remains unclear whether FN’s benefits in DKD involve the modulation of cellular senescence. In this study, we first established a HG-induced injury model in MPC-5 podocytes to evaluate the therapeutic efficacy of FN in vitro. We then performed transcriptomic analysis to examine FN’s impact on global gene expression in MPC-5 cells under HG conditions and to identify potential mechanistic targets for further validation. Finally, we developed a DKD mouse model to assess the in vivo therapeutic and anti-senescence effects of FN. Our findings aim to provide experimental evidence supporting the development of multi-target strategies for DKD and to facilitate the clinical translation of FN.

MPC-5 cells (CL-0855) were purchased from Wuhan Pricella Biotechnology Co., Ltd. Healthy male C57BL/6 mice, aged six to seven weeks, were supplied by SiPeiFu (Production License No. SYXK[Beijing] 2019-0030). All animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Dongzhimen Hospital (Approval No. DZMYY-24-07). Detailed information regarding the kits and antibodies used is provided in the Supplementary material.

Cell culture, modeling, transfection and grouping: MPC-5 cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin at 37 °C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator. The medium was refreshed two to three times per week, and cells were subcultured at split ratios ranging from 1:2 to 1:4.

To establish a HG-induced injury model, MPC-5 cells were exposed to glucose concentrations of 0 mmol/L, 50

To validate the role of MDM2 in FN's anti-senescence mechanism, MPC-5 cells were transfected with shMDM2 or short hairpin negative control using lipofectamine 3000 for 6 hours. The medium was then replaced with fresh culture medium, and subsequent interventions were applied before senescence markers were assessed. The shMDM2 sequence used was: SS: GACAGAGAAUGAUGCUAAAGA; AS: UUUAGCAUCAUUCUCUGUCAG.

MTT assay: After applying the respective treatments as outlined in section “Cell culture, modeling, transfection and grouping”, cells were incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for 24 hours. Then, 10.0 μL of MTT solution (5 mg/mL) was added to each well, followed by incubation for 4 hours. The supernatant was carefully removed, and 150 μL of dimethyl sulfoxide was added to dissolve the formazan crystals. Absorbance was measured at 490 nm using a microplate reader.

Transcriptomics analysis: Total RNA was extracted from each sample group and subjected to rigorous quality control to assess purity, concentration, and integrity. Libraries were constructed from qualified samples and sequenced on the Illumina platform. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between the HG vs control and H-FN vs HG groups were identified using the DESeq2 algorithm, with thresholds set at |Log2(FoldChange)| ≥ 1 and Padj ≤ 0.05. Kyoto En

Molecular docking: The 3D structure of MDM2 (PDB ID: 1T4E) was retrieved from the Protein Data Bank (https://www1.rcsb.org/), and the structure of FN was obtained from PubChem. Water molecules and the native ligand were removed from the protein structure using PyMOL 2.3.0. The small molecule was energy-minimized using Chem3D (2020 version). AutoDock Tools 1.5.6 was used to prepare the protein and generate the pdbqt file. Semi-flexible docking was performed using AutoDock Vina v1.2.0, with the ligand set as flexible and the protein as rigid. The exhaustiveness was set to 8, and a maximum of 9 output conformations were generated.

Modeling, grouping, and drug administration: After one week of acclimatization, 60 mice were randomly allocated to a control group (n = 10) and a DKD modeling group (n = 50). The DKD model was induced as previously described[21] by feeding a high-fat diet (HFD) for 8 weeks followed by a single intraperitoneal injection of STZ (30 mg/kg). Type 2 diabetes mellitus was confirmed by fasting blood glucose (FBG) ≥ 16.7 mmol/L. DKD diagnosis was based on persistent FBG ≥ 16.7 mmol/L combined with 24-hour urine total protein (24h-UTP) ≥ 20 mg. After successful modeling, the 50 mice were randomly divided into five groups (n = 10 per group): DKD model, irbesartan (IRB; 0.2 g/kg/day), and L-FN (25 mg/kg/day), M-FN (50 mg/kg/day), and H-FN (100 mg/kg/day) groups. Control and DKD groups received 0.2 mL normal saline daily by gavage. All treatments continued for 4 weeks, with weekly monitoring of FBG and body weight. After 4 weeks, urine, blood, and kidney tissue samples were collected for analysis.

Urine samples were collected from all groups, and 24h-UTP levels were measured using commercial reagent kits according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Blood samples were centrifuged at 400 × g for 15 minutes to obtain serum. Serum creatinine (Cr) and blood urea nitrogen (BUN) levels were determined using corresponding assay kits as per the provided protocols.

Kidney tissues from the right kidney of each group were fixed, dehydrated, and embedded in paraffin, followed by sectioning at a thickness of 4-5 μm. Hematoxylin and eosin, periodic acid-Schiff, and Masson’s trichrome staining were performed as previously described[21]. Stained sections were examined under a light microscope and evaluated by histological scoring or quantitative analysis according to established criteria[22].

For immunohistochemistry, kidney sections were deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated through a graded ethanol series. Antigen retrieval was carried out using citrate buffer (pH = 6.0) under microwave heating. Endogenous peroxidase activity was quenched with 3% hydrogen peroxide. Sections were then incubated with the following rabbit-derived primary antibodies: Anti-nephrin (Affinity, DF7501; 1:100), anti-p21 (Bioss, bs-55160R; 1:50), anti-Ki67 (Proteintech, 28074-1-AP; 1:2000), and anti-α-smooth muscle actin (Proteintech, 14395-1-AP; 1:3000). After washing, a poly-horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-rabbit secondary antibody (CELNOVTE, SD5300) was applied according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Immunoreactivity was visualized using DAB substrate, and nuclei were counterstained with hematoxylin. Finally, sections were dehydrated, cleared, and mounted for microscopic observation. Images were acquired at 200 × magnification; scale bars represent 50 μm. The immunopositive area was quantified using ImageJ software by measuring DAB-stained regions after setting appropriate thresholds.

Renal tissues from each in vivo experimental group were homogenized, and total protein concentration was determined using the BCA assay. For in vitro experiments, cell culture supernatants were collected, and levels of interleukin-1β (IL-1β), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) were measured using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Absorbance was read at 450 nm with a reference wavelength of 630 nm on a microplate reader.

Renal tissues from mice or cultured cells were homogenized, and total protein concentrations were quantified using the BCA assay. β-galactosidase (β-GAL) activity was measured with commercial assay kits following the manufacturer’s protocols. For senescence-associated β-GAL (SA-β-GAL) staining, cells were washed with PBS and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 minutes at room temperature. After fixation, cells were washed again and incubated with SA-β-GAL staining solution (Beyotime, BL861B) prepared as instructed. Staining was carried out at 37 °C in a dry, CO2-free incubator for 16 hours. Cells were then washed with PBS and observed under a light microscope at 100 × magnification. Senescent cells were identified by blue cytoplasmic staining. Images were captured for documentation and analysis.

Approximately 100 mg of renal tissue or cultured cells were lysed in 1 mL of RIPA buffer (Perseebio, PBW003W0) supplemented with 1 mmol/L PMSF (Perseebio, PBW007W0) on ice. Total protein was isolated and quantified using the BCA assay. Proteins were separated by electrophoresis on 4%-12% precast gels (LABLEAD, P41215, P00815; Perseebio, PBW030W1) and transferred (Perseebio, PBW031W0) onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore, United States). Membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat milk (Perseebio, PBW034W1) in TBST for 1 hour at room temperature, then incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies. After washing, membranes were incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (bs-0295G-HRP; 1:5000) for 2 hours at room temperature. Protein bands were visualized using ECL plus chemiluminescence reagent (Perseebio, PBW041W0) and imaged with an automated imaging system (ProteinsimPle, United States). Signal intensities were quantified using ImageJ.

Total RNA was extracted from renal tissues using TRNzol Universal Reagent (Tiangen, DP424). RNA concentration and purity were assessed spectrophotometrically. Complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized from 1 μg total RNA using the RevertAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo, K1622). Quantitative real-time PCR was performed on an ABI7500 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems) using 2 × SYBR Green qPCR Master Mix (Selleck, B21203). Each 20 μL reaction contained 10 μL master mix, 1 μL cDNA, 0.4 μL each of forward and reverse primers (10 μM), and 8.2 μL nuclease-free ddH2O (Tiangen, RT121-02). The thermal cycling protocol consisted of initial denaturation at 95 °C for 10 minutes, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 seconds and 60 °C for 60 seconds. All samples were run in triplicate using MicroAmTM Fast Optical 96-Well Plates (ABI, 4316813) sealed with Optical Adhesive Films (ABI, 4314320). Primer sequences are provided in Supplementary Table 1. Relative mRNA expression levels were calculated using the 2-ΔΔCT method with β-actin as the internal reference gene.

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (IBM). Quantitative data are expressed as mean ± SD. Normality was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Differences among groups were evaluated by one-way ANOVA, and pairwise comparisons were conducted using Tukey’s HSD post hoc test. A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. GraphPad Prism version 8.0 was used for data visualization.

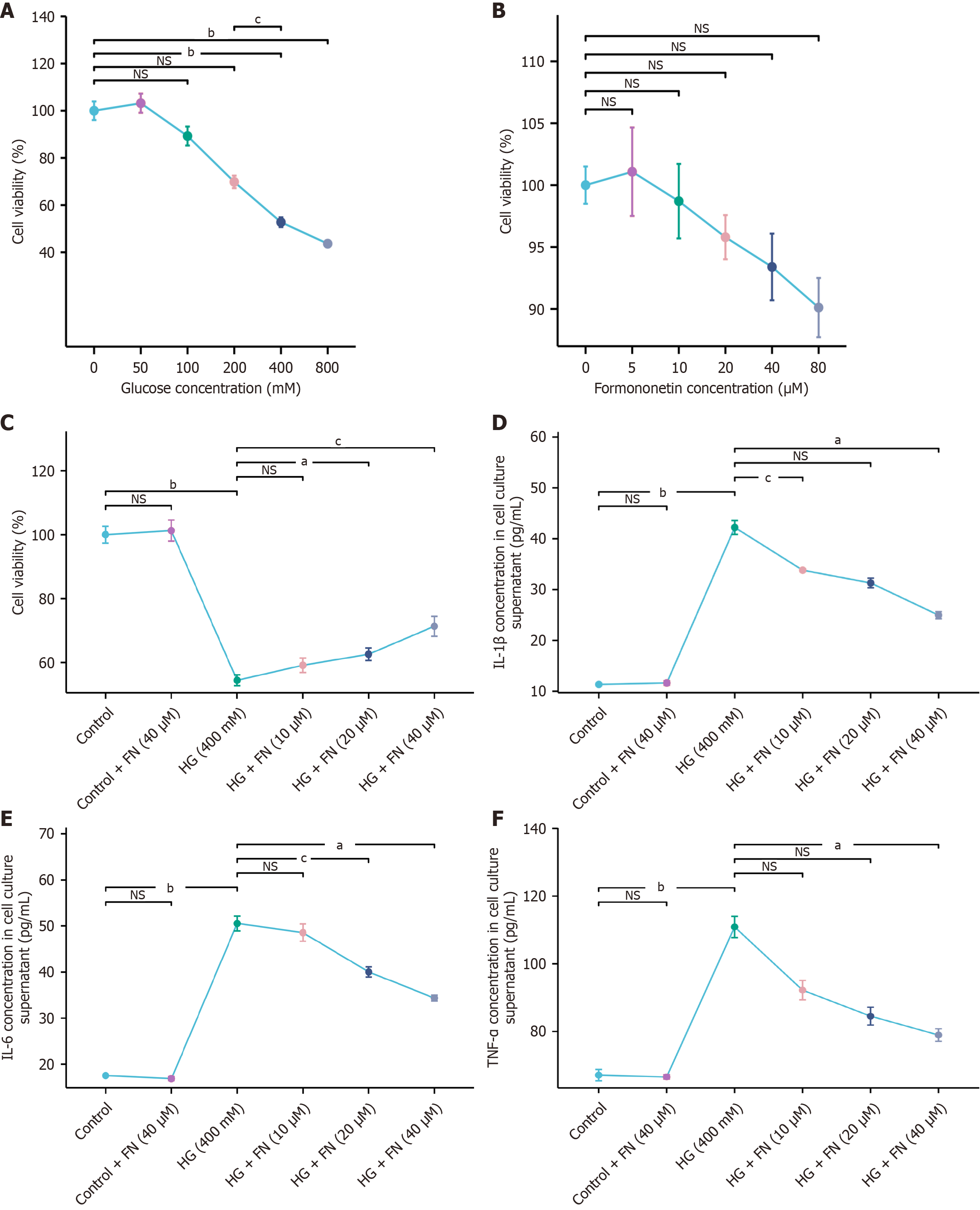

To establish an in vitro model of podocyte injury, MPC-5 cells were exposed to increasing concentrations of glucose. The MTT assay indicated that 400 mmol/L glucose reduced cell viability by approximately 50%, while 800 mmol/L further decreased viability to about 20%. Consequently, 400 mmol/L glucose was selected for subsequent modeling (Figure 1A). To determine non-cytotoxic concentrations of FN, cells were treated with various doses of FN. Concentrations up to 40 μM showed no significant effect on viability, whereas 80 μM markedly reduced it. Therefore, FN doses of 10 μM, 20 μM, and 40 μM were chosen for further experiments (Figure 1B). As illustrated in Figure 1C, HG significantly suppressed MPC-5 cell viability, and FN treatment restored viability in a dose-dependent manner. Moreover, ELISA results indicated that FN reduced the secretion of senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) factors—IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α—in the cell culture supernatant (Figure 1D-F).

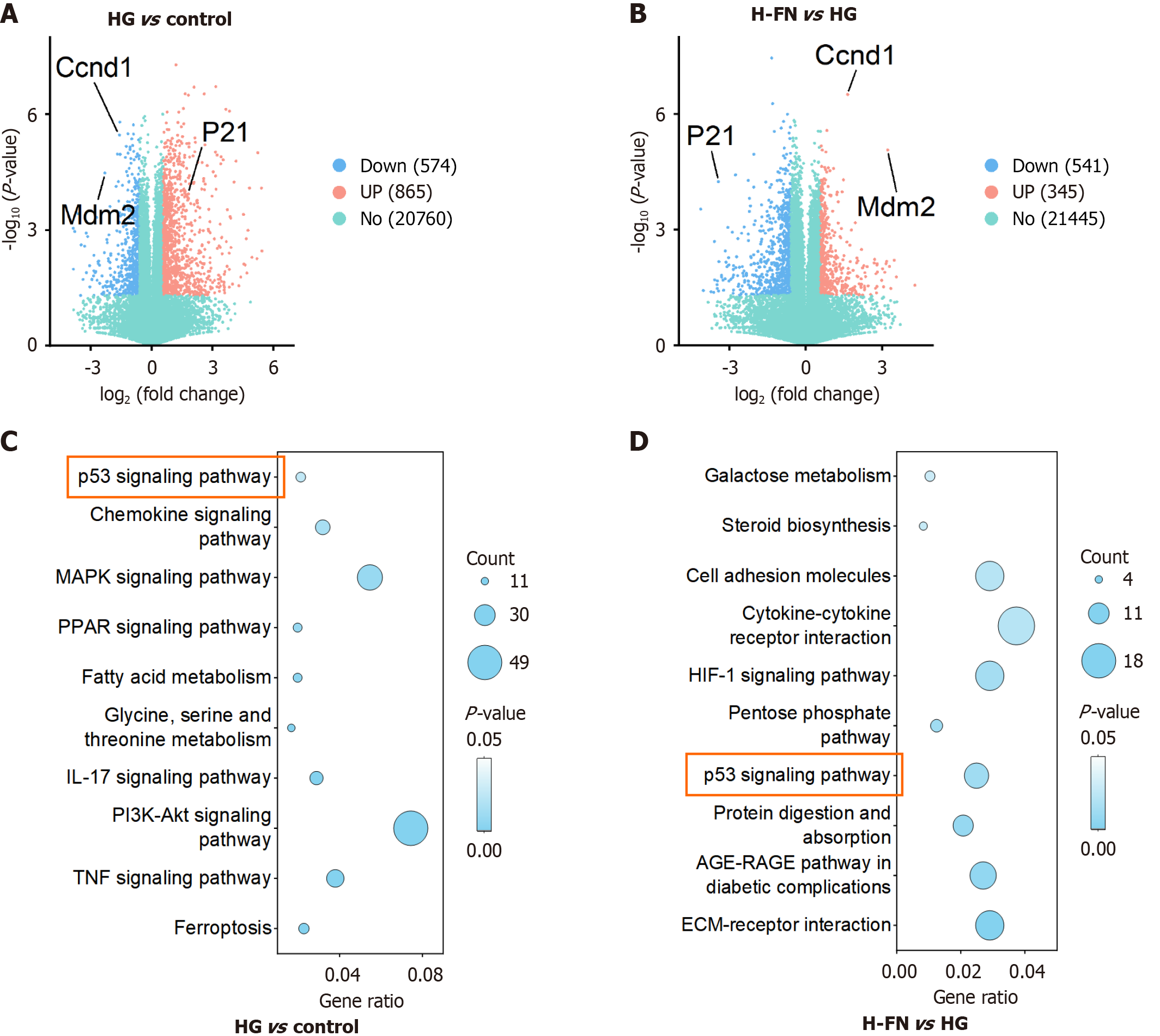

We conducted transcriptomic profiling of cells from the control, HG, and HG + H-FN groups. DEGs were identified using the thresholds of |Log2(FoldChange)| ≥ 1 and Padj ≤ 0.05 for comparisons between HG vs control and H-FN vs HG. The results were visualized using volcano plots (Figure 2A and B). Subsequent KEGG pathway enrichment analysis revealed that DEGs from the HG vs control comparison were primarily enriched in the following pathways (Figure 2C): P53 signaling, chemokine signaling, MAPK signaling, PPAR signaling, fatty acid metabolism, glycine, serine and threonine metabolism, IL-17 signaling, PI3K-Akt signaling, TNF signaling, and ferroptosis. In contrast, the DEGs from the HG + H-FN vs HG comparison were mainly enriched in extracellular matrix-receptor interaction, the AGE-RAGE signaling pathway in diabetic complications, protein digestion and absorption, p53 signaling, pentose phosphate pathway, HIF-1 signaling, cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction, cell adhesion molecules, steroid biosynthesis and galactose metabolism (Figure 2D). Notably, the p53 signaling pathway was significantly enriched in both comparisons, suggesting that FN may mitigate DKD progression largely through modulation of the p53 signaling pathway.

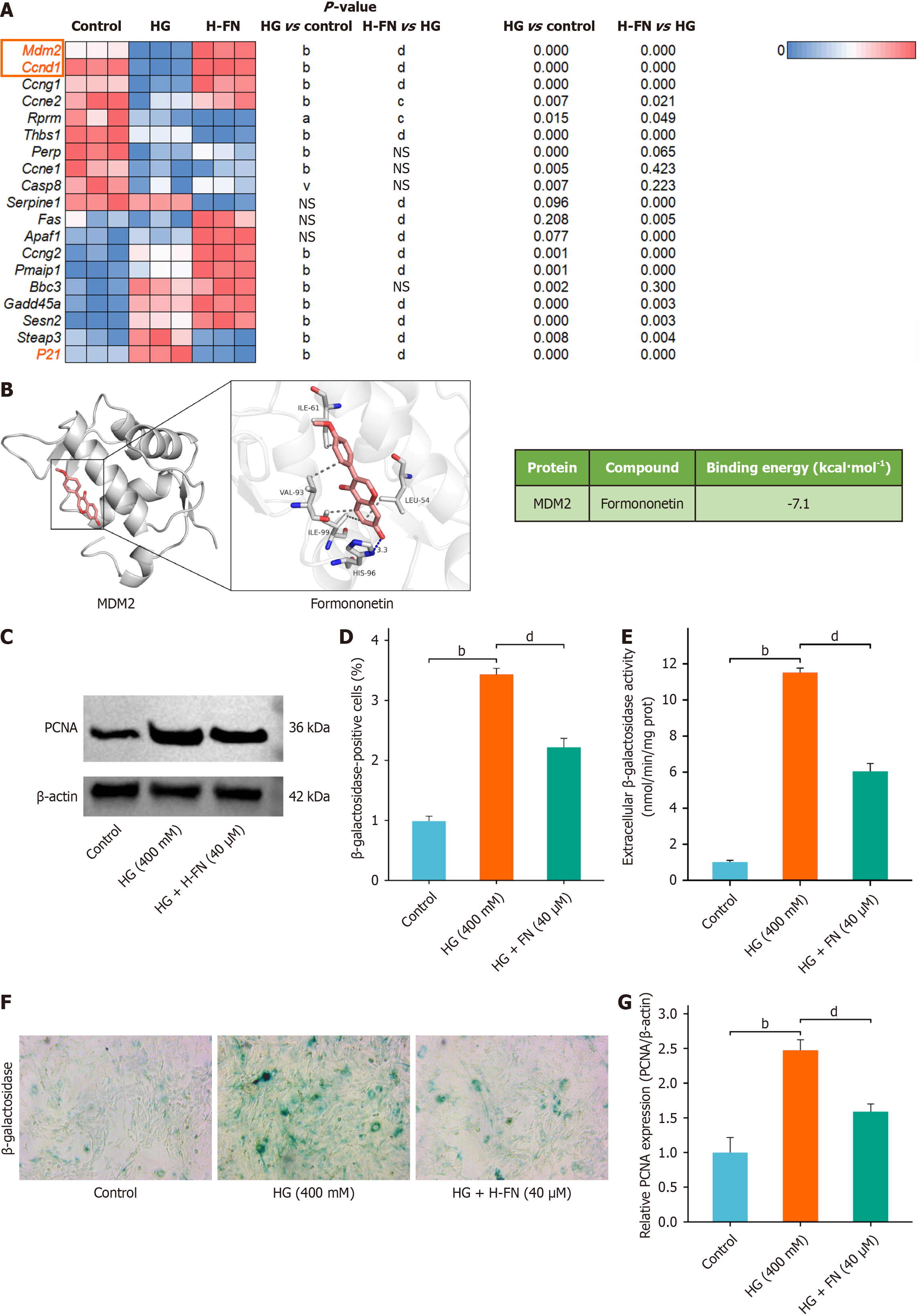

Analysis of p53 pathway-related gene expression from transcriptomic data showed that HG exposure significantly downregulated MDM2 and CCND1 expression and upregulated p21. FN treatment reversed these changes (Figure 3A). Molecular docking analysis revealed that FN interacts with MDM2 via hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions (Figure 3B). Specifically, FN forms one hydrogen bond with residue HIS96 at a distance of 3.3 Å, and engages in multiple hydrophobic interactions with ILE61, VAL93, ILE99, and LEU54. The calculated binding energy was -7.1 kcal/mol, indicating strong binding affinity and favorable free energy, supporting the likelihood of FN exerting pharmacological effects through this interaction.

Given the known link between the p53 pathway and cellular senescence, we further evaluated the anti-senescence effect of FN in a HG-induced MPC-5 injury model (Figure 3C). β-GAL activity assays showed that HG significantly increased β-GAL activity in MPC-5 cells, while FN treatment markedly reduced it (Figure 3D). Cell staining results were consistent with these trends (Figure 3E).

Proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) plays an important role in the development of DKD, particularly in regulating renal cell proliferation and fibrosis under HG conditions. Western blot analysis revealed that HG increased PCNA protein expression, which was attenuated by FN treatment (Figure 3F and G).

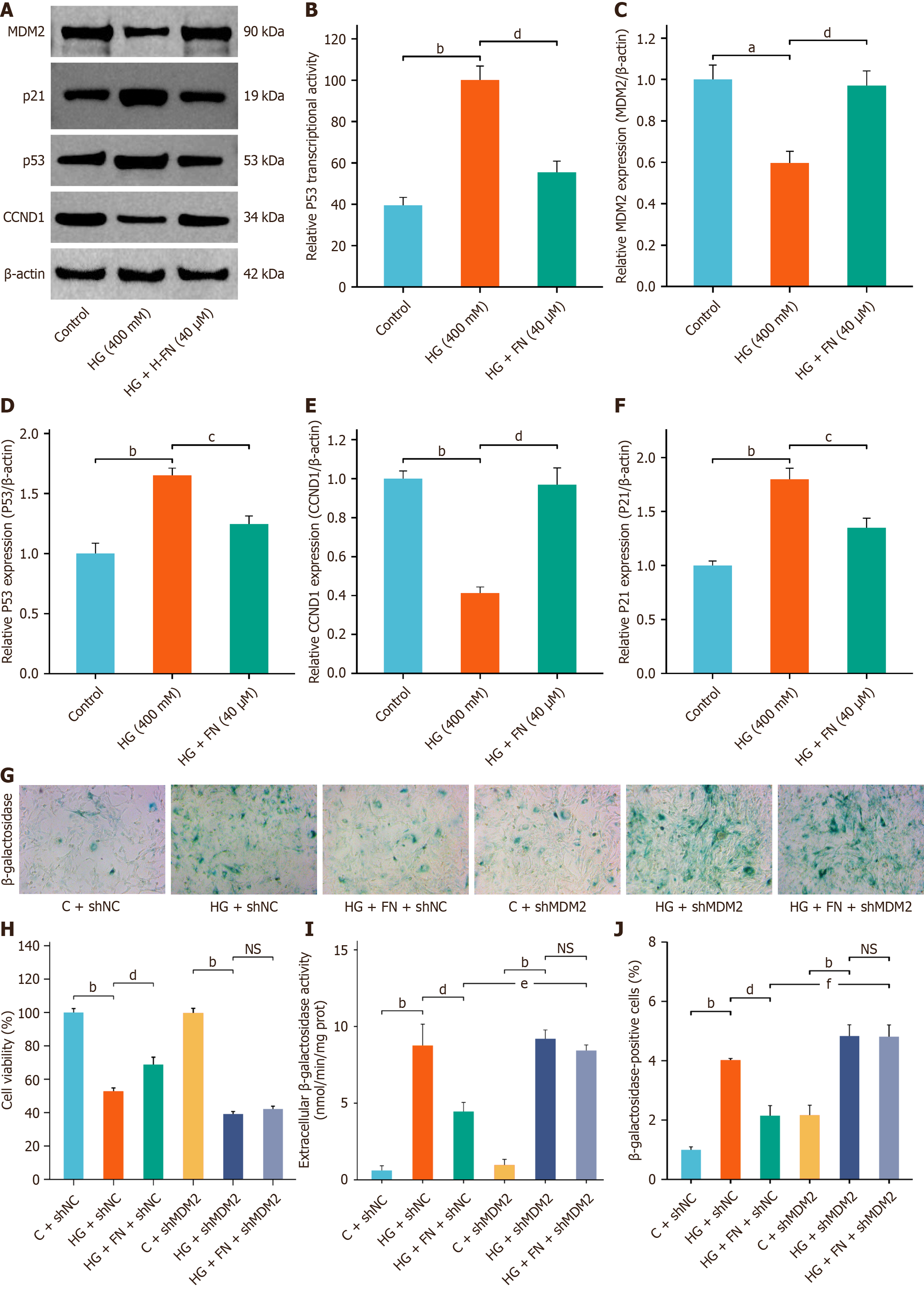

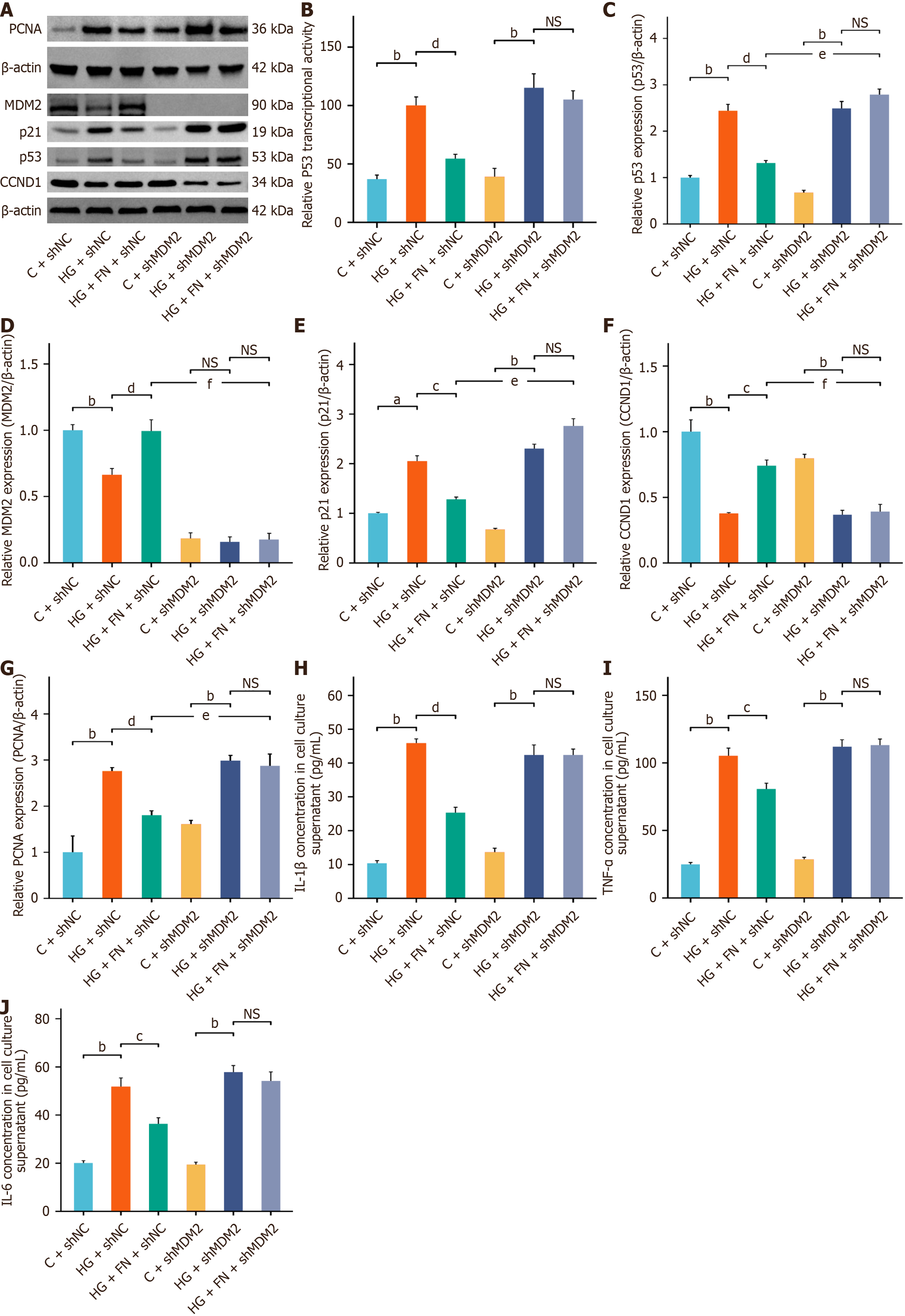

Dual-luciferase reporter assays further demonstrated that FN significantly inhibited p53 transcriptional activity (Figure 4A and B). Western blot confirmed that FN upregulated MDM2 and CCND1 protein expression while downregulating p53 and p21 (Figure 4A and C-F). Building upon our previous findings, we hypothesize that FN exerts its anti-senescence effects by modulating MDM2 expression, thereby suppressing hyperactivation of the p53 signaling pathway. Given that MDM2 serves as a critical upstream regulator of p53, we further investigated FN's anti-senescence role by silencing the MDM2 gene in MPC-5 cells. MTT assay results demonstrated that MDM2 silencing significantly reduced MPC-5 cell viability and abrogated the protective effect of FN on cell survival (Figure 4G and H). Moreover, MDM2 knockdown attenuated the regulatory influence of FN on the expression of the SASP. Both β-GAL activity assays and β-GAL staining confirmed that MDM2 silencing eliminated the inhibitory effect of FN on β-GAL activity in MPC-5 cells (Figure 4G, I and J).

Dual-luciferase reporter assays showed that MDM2 silencing enhanced p53 transcriptional activity and counteracted the inhibitory effect of FN on p53 (Figure 5A and B). Western blot analysis further confirmed that MDM2 knockdown abolished the regulatory effects of FN on the protein expression (Figure 5A and C-G) of MDM2, CCND1, p53, PCNA, and p21. ELISA results indicated that MDM2 silencing elevated the secretion of SASP factors—specifically IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α—in the culture supernatant (Figure 5H-J). Taken together, these results demonstrate that MDM2 silencing attenuates the anti-senescence benefits of FN in the HG-induced MPC-5 cell injury model.

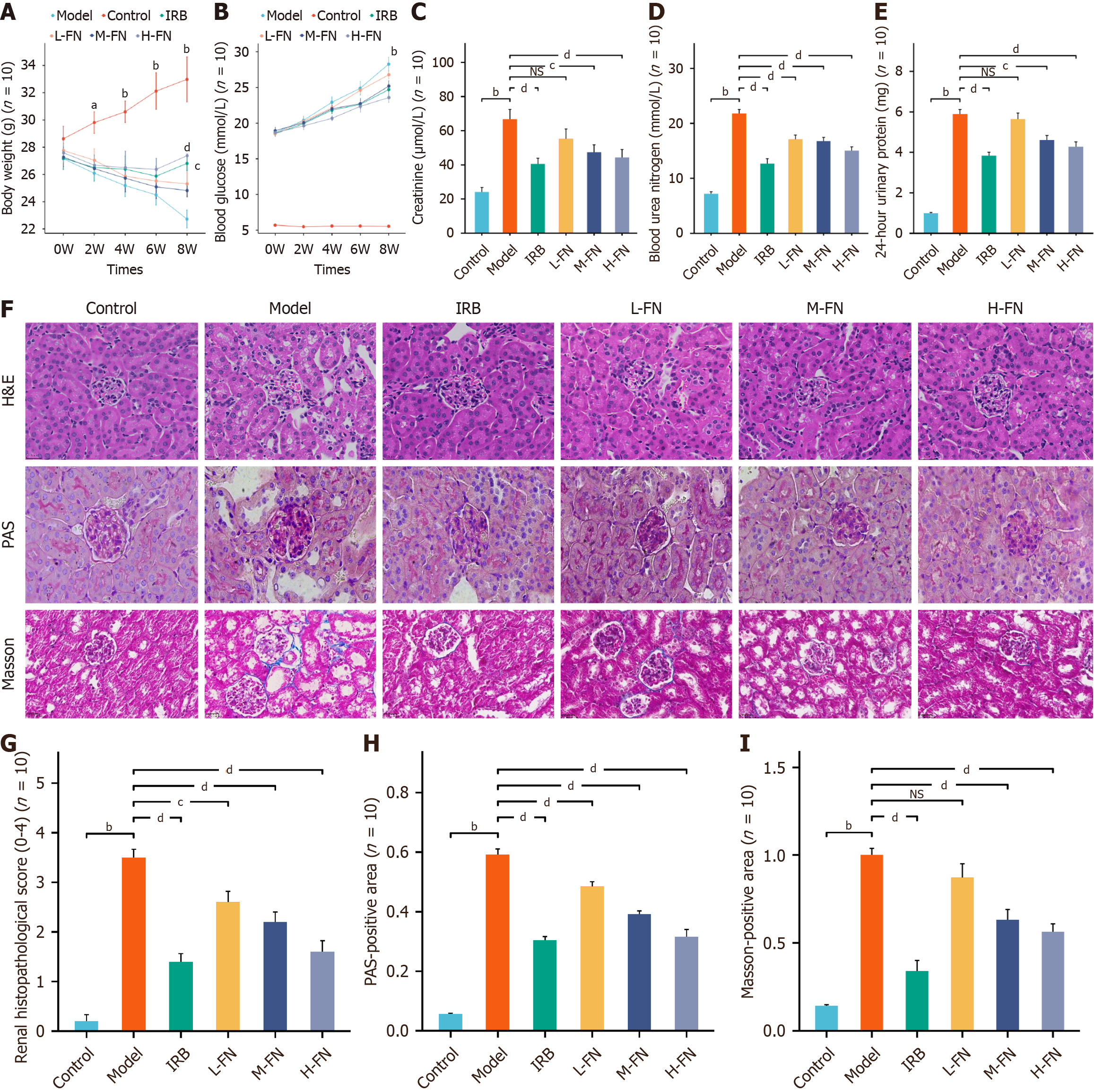

Building on our in vitro findings, we established a DKD mouse model to evaluate the in vivo therapeutic potential of FN. Body weight (Figure 6A) monitoring indicated that DKD mice experienced significant weight loss compared with control animals, whereas the IRB- and FN-treated groups exhibited varying degrees of weight recovery over time. FBG levels (Figure 6B) were significantly elevated in DKD mice relative to controls. The IRB and H-FN groups showed moderate reductions in FBG, while the L-FN and M-FN groups did not differ significantly from untreated DKD mice. Renal function analysis revealed marked increases in serum Cr, BUN, and 24h-UTP levels in DKD mice compared with controls (Figure 6C-E). Both IRB and FN treatments reversed these alterations to varying degrees. Histopathological examination demonstrated severe renal injury in DKD mice (Figure 6F-I), characterized by glomerular hypertrophy, basement membrane thickening, increased extracellular matrix deposition, and enhanced fibrosis. Importantly, IRB and FN intervention ameliorated these pathological changes.

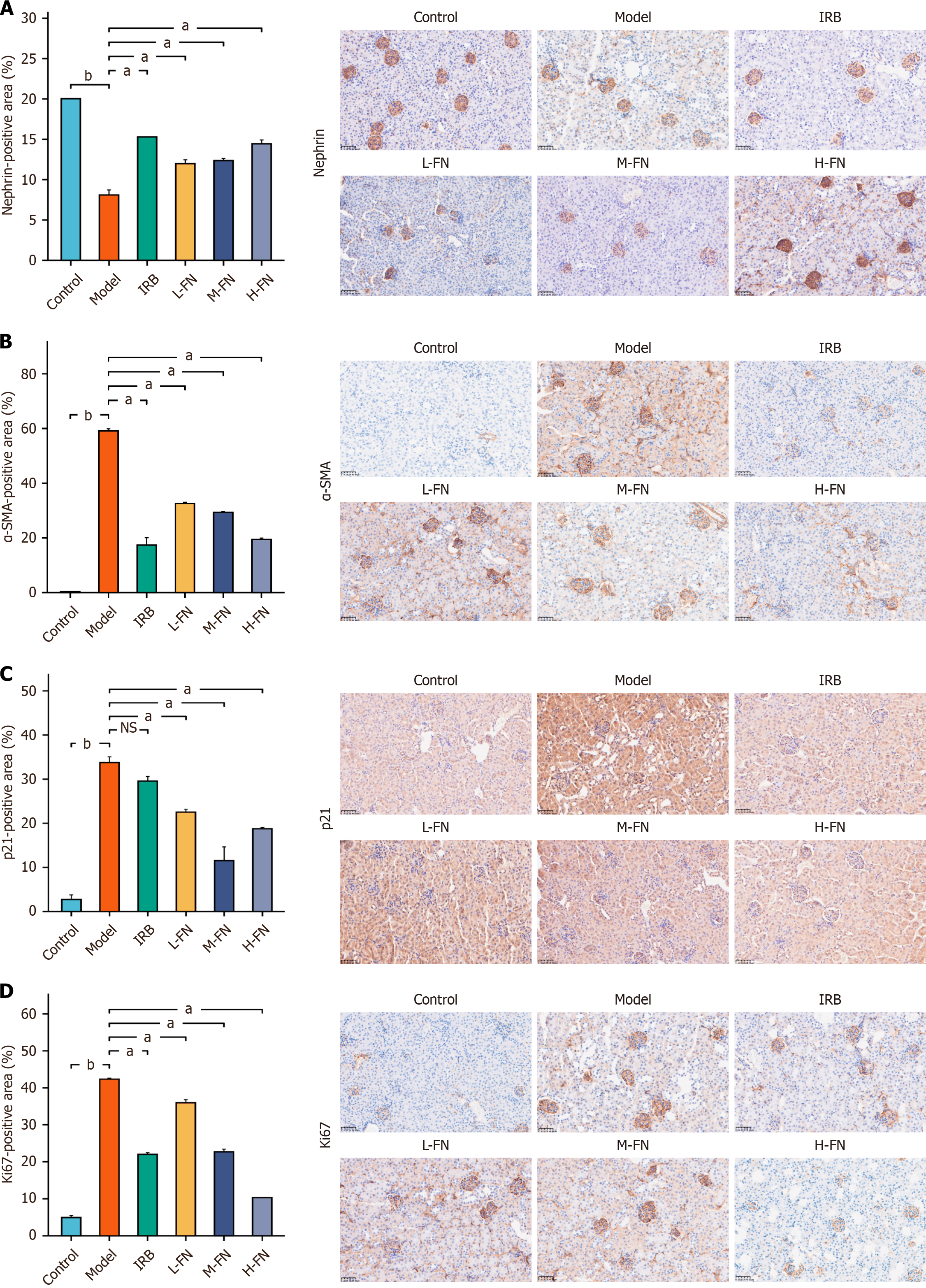

To evaluate the expression of nephrin, a podocyte-specific marker, IHC was performed to examine the slit diaphragm between podocyte foot processes in renal tissues from each experimental group. Representative results are shown in the figure above. In the negative control group, nephrin immunostaining (Figure 7A) was the most intense, whereas a pronounced reduction was observed in DKD mice. Compared with the DKD group, the positive area of nephrin was significantly increased in IRB- and all FN-treated groups. Immunohistochemical analysis further revealed substantial changes in the expression of α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), p21, and Ki67 across groups (Figure 7B-D). In the DKD model group, α-SMA expression was markedly upregulated compared with the normal group, suggesting activation of fibrogenic cells. FN treatment at low, medium, and high doses resulted in a dose-dependent decrease in α-SMA ex

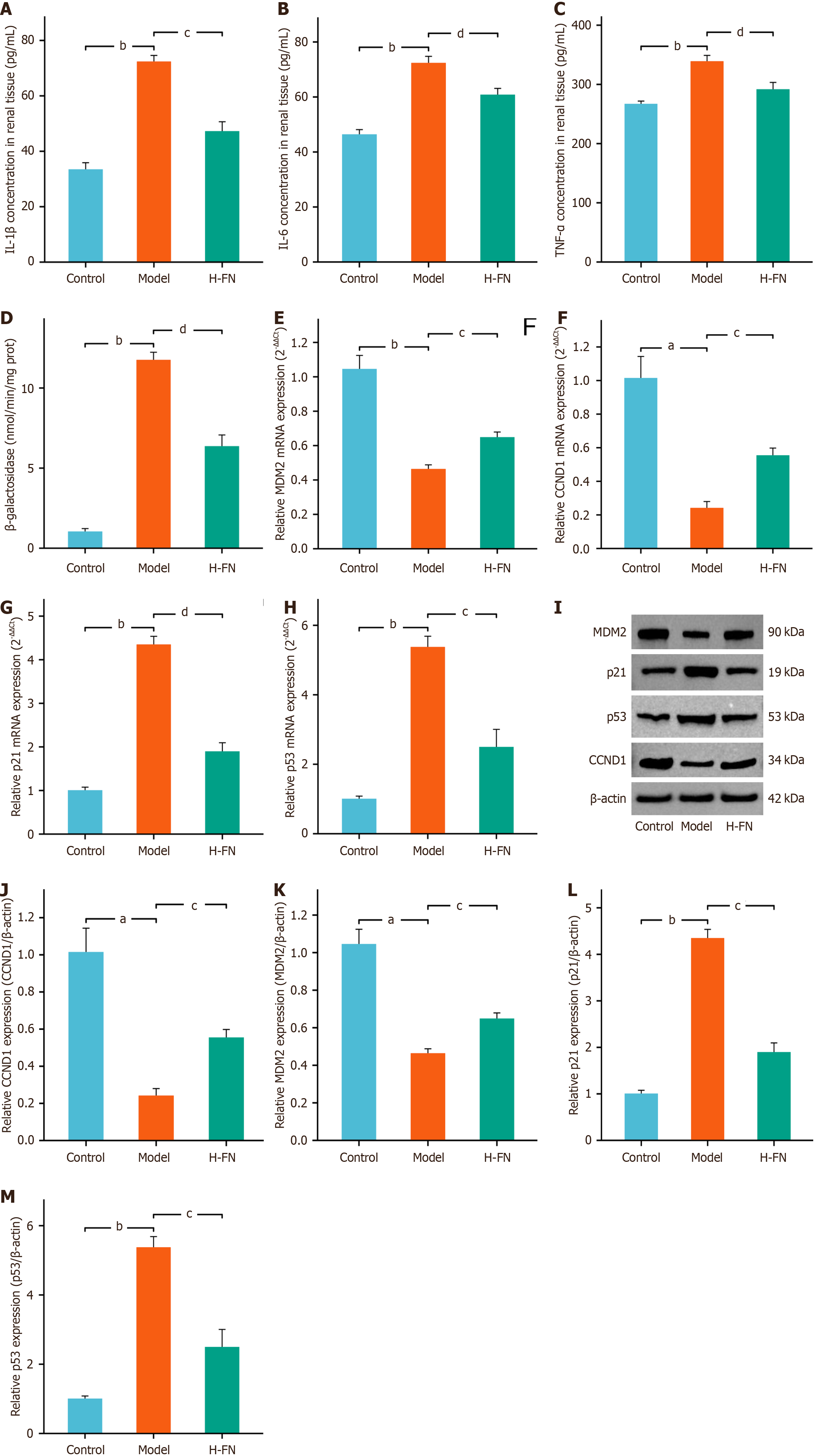

We next evaluated the anti-senescence effects of FN in vivo. ELISA results indicated that FN treatment markedly suppressed the levels of SASP factors, such as IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α, in the renal tissues of DKD mice (Figure 8A-C). β-GAL activity assays further demonstrated that FN significantly reduced β-GAL activity in renal tissues (Figure 8D). Moreover, RT-qPCR (Figure 8E-H) and Western blot (Figure 8I-M) analyses revealed that FN led to a distinct upregulation of MDM2 and CCND1 and a concurrent downregulation of p53 and p21 at both the gene and protein levels. These findings collectively suggest that FN exerts its anti-aging effects in DKD mice, at least in part, through modulation of the p53 signaling pathway.

DKD substantially compromises patient health and quality of life, while imposing a considerable socioeconomic burden. Although FN has shown promise as a therapeutic candidate for DKD[22], its mechanisms of action remain incompletely understood. In this study, we systematically evaluated the efficacy of FN using both in vitro and in vivo DKD models.

We employed the HG-induced MPC-5 cell injury model, a well-established in vitro system, to evaluate the protective effects of FN against podocyte damage and to explore the underlying pathological mechanisms. This model reliably recapitulates the characteristic podocyte injury occurring in the diabetic hyperglycemic microenvironment, providing a robust platform for drug screening and mechanistic investigation[23]. Our findings indicate that FN significantly enhanced the viability of MPC-5 cells exposed to HG, supporting its potential to alleviate HG-induced podocyte toxicity. Since HG-induced cellular senescence represents a key driver in the pathogenesis of DKD, we further quantified the levels of SASP factors, including IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α, in cell culture supernatants to assess the anti-senescence effects of FN. The results revealed that FN treatment markedly suppressed SASP factor secretion in HG-stimulated MPC-5 cells, indicating its ability to attenuate cellular senescence.

For in vivo investigations, a DKD mouse model was established by combining a HFD with intraperitoneal injection of STZ. This model faithfully recapitulates the natural progression of DKD, beginning with metabolic syndrome, pro

To elucidate the molecular mechanisms underlying FN's renoprotective effects, we performed transcriptomic sequencing on control, HG, and HG + H-FN treated cells. The p53 signaling pathway was identified as a key pathway differentially regulated in both the HG vs control and H-FN vs HG comparisons, suggesting that FN may exert its therapeutic action through modulation of this pathway. Further analysis revealed that FN treatment significantly altered the expression of senescence-associated genes within the p53 pathway, including MDM2, p21, and CCND1. These findings imply a potential role for FN in delaying cellular senescence. MDM2, a nuclear protein with multifaceted biological functions, is expressed in glomeruli and plays an essential role in podocyte cell cycle regulation[27]. MDM2 facilitates the ubiquitination of p53, leading to its proteasomal degradation and thereby maintaining low basal levels of p53 in cells. This regulatory mechanism helps prevent inappropriate cell cycle arrest or apoptosis under physiological conditions[28]. Notably, multiple studies have indicated that HG conditions suppress both the expression and activity of MDM2, resulting in dysregulated cell cycle control and accelerated cellular senescence[28,29]. Consequently, targeting the MDM2-p53 axis has emerged as a promising therapeutic strategy to counteract cellular senescence[28]. As a key tumor suppressor protein, p53 plays a central role in regulating cell cycle progression and can induce either arrest or apoptosis depending on cellular context. Its activity—tightly modulated by the extracellular microenvironment—is critically implicated in the establishment and maintenance of cellular senescence.

HG stimulation activates p53, prompting its nuclear translocation and enhancing its transcriptional activity, which subsequently induces cell cycle arrest and cellular senescence[30]. Elevated expression levels of p53 and p21 have been observed in renal tissues from patients with DKD, and these levels correlate with disease severity[31,32]. In addition, p53 has been implicated in podocyte senescence and apoptosis in animal models of DKD[33,34]. Inhibition of p53 activation in these models effectively attenuates renal injury, particularly cellular senescence[35,36]. Hyperactivation of p53 promotes the accumulation of p21[37], a cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor that binds to and inhibits CCND1—a key regulator of the G1/S phase transition. This inhibition induces G1 phase arrest and promotes a senescent phenotype. Senescent cells secrete numerous SASP factors, which disrupt tissue repair and remodeling processes[38]. Under persistent HG conditions, CCND1 expression is suppressed while p21 is upregulated, further aggravating cell cycle arrest, senescence, and the progression of DKD toward end-stage renal disease[39].

The role of CCND1 in terminally differentiated cells such as podocytes is complex and context-dependent. In dividing cells, such as stem or progenitor cells, CCND1 acts as a positive regulator of the G1/S transition by forming complexes with CDK4/6 to promote cell cycle progression; in this setting, its upregulation is typically associated with physiological growth signals. However, in terminally differentiated podocytes, which lack a complete mitotic program, forced cell cycle re-entry can lead to mitotic catastrophe and cell death—a recognized mechanism of podocyte loss in glomerular diseases. In the present study, cellular senescence is regarded as a stable form of cell cycle arrest. Our investigation focuses on broader aging phenotypes and the regulation of the p53 signaling pathway, rather than drawing mechanistic conclusions based solely on changes in CCND1 expression. Targeting p21 has emerged as a promising therapeutic strategy to delay cellular senescence and alleviate renal injury in DKD[40]. Consistent with this notion, our in vitro and in vivo experiments demonstrated that FN treatment upregulates MDM2 and CCND1 expression, while downregulating p53 and p21 at both transcriptional and protein levels. These results suggest that FN exerts anti-senescence effects by inhibiting hy

To validate the molecular target of FN, we performed MDM2 gene silencing in MPC-5 cells in vitro. The loss of MDM2 significantly attenuated the anti-senescent effects of FN, confirming that FN exerts its therapeutic actions in DKD primarily through MDM2-mediated inhibition of the p53 signaling pathway. Although our findings demonstrate that FN delays cellular senescence and ameliorates DKD pathology via modulation of the p53 pathway, the precise binding mechanism between FN and MDM2, as well as the upstream regulatory signals controlling MDM2 expression, remain to be fully elucidated. Future studies employing proteomics, chromatin immunoprecipitation, and other mechanistic approaches will be essential to decipher the comprehensive regulatory network through which FN fine-tunes p53 signaling.

PCNA serves as a well-established marker of cell proliferation and has also been identified as an early and significant indicator of EMT, a process central to phenotypic alterations in renal cells[41]. In DKD, PCNA expression undergoes marked changes and serves as a valuable indicator of renal cellular proliferation and injury. In experimental models of this condition, elevated PCNA expression is associated with increased proliferative activity, reflecting either com

Finally, given the multifactorial pathogenesis of DKD, which involves oxidative stress, inflammation, and fibrosis, among other processes, it is essential to investigate whether FN influences additional key pathways. A broader understanding of its multi-target mechanisms will provide deeper insight into its therapeutic potential and support its future clinical translation.

Our study demonstrates that FN exerts therapeutic effects against DKD in both cellular and animal models. Mechanistically, FN delays cellular senescence by inhibiting hyperactivation of the p53 signaling pathway. We provide the first evidence that FN mitigates podocyte senescence through suppression of p53 pathway activation, offering novel insights into DKD pathogenesis and extending the application of cellular senescence theory to chronic kidney disease. The role of the p53-MDM2-p21 axis in DKD-associated senescence is well-documented (Figure 9). In this work, molecular docking revealed a strong binding affinity between FN and MDM2, and gene silencing experiments further confirmed MDM2 as a key mediator of FN’s anti-senescence effects. However, this study has certain limitations. We did not examine specific p53 phosphorylation sites (e.g., Ser15 and Ser20) or assess MDM2-mediated ubiquitination, leaving it unclear whether FN directly inhibits p53 transcriptional activity or promotes its degradation. Moreover, while we used HG to induce cellular injury and senescence, future studies should incorporate established aging models—including drug-induced senescence systems—to more directly evaluate how FN modulates the senescence process, affects cell division dynamics, and alters cellular morphology.

| 1. | Gupta S, Dominguez M, Golestaneh L. Diabetic Kidney Disease: An Update. Med Clin North Am. 2023;107:689-705. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 210] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Sun H, Saeedi P, Karuranga S, Pinkepank M, Ogurtsova K, Duncan BB, Stein C, Basit A, Chan JCN, Mbanya JC, Pavkov ME, Ramachandaran A, Wild SH, James S, Herman WH, Zhang P, Bommer C, Kuo S, Boyko EJ, Magliano DJ. IDF Diabetes Atlas: Global, regional and country-level diabetes prevalence estimates for 2021 and projections for 2045. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2022;183:109119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3033] [Cited by in RCA: 5846] [Article Influence: 1461.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (37)] |

| 3. | Samsu N. Diabetic Nephropathy: Challenges in Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Biomed Res Int. 2021;2021:1497449. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 605] [Article Influence: 121.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Tye SC, Denig P, Heerspink HJL. Precision medicine approaches for diabetic kidney disease: opportunities and challenges. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2021;36:3-9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Zha D, Wu X. Nutrient sensing, signaling transduction, and autophagy in podocyte injury: implications for kidney disease. J Nephrol. 2023;36:17-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Verzola D, Gandolfo MT, Gaetani G, Ferraris A, Mangerini R, Ferrario F, Villaggio B, Gianiorio F, Tosetti F, Weiss U, Traverso P, Mji M, Deferrari G, Garibotto G. Accelerated senescence in the kidneys of patients with type 2 diabetic nephropathy. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2008;295:F1563-F1573. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 173] [Cited by in RCA: 244] [Article Influence: 13.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Wu YS, Liang S, Li DY, Wen JH, Tang JX, Liu HF. Cell Cycle Dysregulation and Renal Fibrosis. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9:714320. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Dong W, Jia C, Li J, Zhou Y, Luo Y, Liu J, Zhao Z, Zhang J, Lin S, Chen Y. Fisetin Attenuates Diabetic Nephropathy-Induced Podocyte Injury by Inhibiting NLRP3 Inflammasome. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:783706. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Zang L, Gao F, Huang A, Zhang Y, Luo Y, Chen L, Mao N. Icariin inhibits epithelial mesenchymal transition of renal tubular epithelial cells via regulating the miR-122-5p/FOXP2 axis in diabetic nephropathy rats. J Pharmacol Sci. 2022;148:204-213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Zhang S, Li Y, Wang Q. Icariin Attenuates Human Renal Tubular Epithelial Cell Senescence by Targeting PAK2 via miR-23b-3p. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2024;25:2278-2289. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Lu H, Li Y, Zhang T, Liu M, Chi Y, Liu S, Shi Y. Salidroside Reduces High-Glucose-Induced Podocyte Apoptosis and Oxidative Stress via Upregulating Heme Oxygenase-1 (HO-1) Expression. Med Sci Monit. 2017;23:4067-4076. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Pei D, Tian S, Bao Y, Zhang J, Xu D, Piao M. Protective effect of salidroside on streptozotocin-induced diabetic nephropathy by inhibiting oxidative stress and inflammation in rats via the Akt/GSK-3β signalling pathway. Pharm Biol. 2022;60:1732-1738. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Liu Q, Chen J, Zeng A, Song L. Pharmacological functions of salidroside in renal diseases: facts and perspectives. Front Pharmacol. 2023;14:1309598. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Ji J, Tao P, Wang Q, Cui M, Cao M, Xu Y. Emodin attenuates diabetic kidney disease by inhibiting ferroptosis via upregulating Nrf2 expression. Aging (Albany NY). 2023;15:7673-7688. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Hassanein EHM, Ibrahim IM, Abd-Alhameed EK, Mohamed NM, Ross SA. Protective effects of berberine on various kidney diseases: Emphasis on the promising effects and the underlined molecular mechanisms. Life Sci. 2022;306:120697. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Cao D, Zhao M, Wan C, Zhang Q, Tang T, Liu J, Shao Q, Yang B, He J, Jiang C. Role of tea polyphenols in delaying hyperglycemia-induced senescence in human glomerular mesangial cells via miR-126/Akt-p53-p21 pathways. Int Urol Nephrol. 2019;51:1071-1078. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Huang Q, Chen H, Yin K, Shen Y, Lin K, Guo X, Zhang X, Wang N, Xin W, Xu Y, Gui D. Formononetin Attenuates Renal Tubular Injury and Mitochondrial Damage in Diabetic Nephropathy Partly via Regulating Sirt1/PGC-1α Pathway. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:901234. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Ahmed QU, Ali AHM, Mukhtar S, Alsharif MA, Parveen H, Sabere ASM, Nawi MSM, Khatib A, Siddiqui MJ, Umar A, Alhassan AM. Medicinal Potential of Isoflavonoids: Polyphenols That May Cure Diabetes. Molecules. 2020;25:5491. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Lv J, Zhuang K, Jiang X, Huang H, Quan S. Renoprotective Effect of Formononetin by Suppressing Smad3 Expression in Db/Db Mice. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2020;13:3313-3324. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Zhuang K, Jiang X, Liu R, Ye C, Wang Y, Wang Y, Quan S, Huang H. Formononetin Activates the Nrf2/ARE Signaling Pathway Via Sirt1 to Improve Diabetic Renal Fibrosis. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11:616378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Lv S, Li H, Zhang T, Su X, Sun W, Wang Q, Wang L, Feng N, Zhang S, Wang Y, Cui H. San-Huang-Yi-Shen capsule ameliorates diabetic nephropathy in mice through inhibiting ferroptosis. Biomed Pharmacother. 2023;165:115086. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Cai X, Cao H, Wang M, Yu P, Liang X, Liang H, Xu F, Cai M. SGLT2 inhibitor empagliflozin ameliorates tubulointerstitial fibrosis in DKD by downregulating renal tubular PKM2. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2025;82:159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Zhang S, Zhang S, Bai X, Wang Y, Liu Y, Liu W. Thonningianin A ameliorated renal interstitial fibrosis in diabetic nephropathy mice by modulating gut microbiota dysbiosis and repressing inflammation. Front Pharmacol. 2024;15:1389654. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Li X, Zhao S, Xie J, Li M, Tong S, Ma J, Yang R, Zhao Q, Zhang J, Xu A. Targeting the NF-κB p65-MMP28 axis: Wogonoside as a novel therapeutic agent for attenuating podocyte injury in diabetic nephropathy. Phytomedicine. 2025;138:156406. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Zhang T, Sun W, Wang L, Zhang H, Wang Y, Pan B, Li H, Ma Z, Xu K, Cui H, Lv S. Rosa laevigata Michx. Polysaccharide Ameliorates Diabetic Nephropathy in Mice through Inhibiting Ferroptosis and PI3K/AKT Pathway-Mediated Apoptosis and Modulating Tryptophan Metabolism. J Diabetes Res. 2023;2023:9164883. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Parving HH, Lehnert H, Bröchner-Mortensen J, Gomis R, Andersen S, Arner P; Irbesartan in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes and Microalbuminuria Study Group. The effect of irbesartan on the development of diabetic nephropathy in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:870-878. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2280] [Cited by in RCA: 2129] [Article Influence: 85.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Saito R, Rocanin-Arjo A, You YH, Darshi M, Van Espen B, Miyamoto S, Pham J, Pu M, Romoli S, Natarajan L, Ju W, Kretzler M, Nelson R, Ono K, Thomasova D, Mulay SR, Ideker T, D'Agati V, Beyret E, Belmonte JCI, Anders HJ, Sharma K. Systems biology analysis reveals role of MDM2 in diabetic nephropathy. JCI Insight. 2016;1:e87877. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Yang Y, Wang B, Dong H, Lin H, Yuen-Man Ho M, Hu K, Zhang N, Ma J, Xie R, Cheng KK, Li X. The mitochondrial enzyme pyruvate carboxylase restricts pancreatic β-cell senescence by blocking p53 activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2024;121:e2401218121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Mei H, Jing T, Liu H, Liu Y, Zhu X, Wang J, Xu L. Ursolic Acid Alleviates Mitotic Catastrophe in Podocyte by Inhibiting Autophagic P62 Accumulation in Diabetic Nephropathy. Int J Biol Sci. 2024;20:3317-3333. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Rufini A, Tucci P, Celardo I, Melino G. Senescence and aging: the critical roles of p53. Oncogene. 2013;32:5129-5143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 471] [Cited by in RCA: 807] [Article Influence: 62.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Zhang Y, Zhao Y, Liu YQ, Fang YP, Sun L, Wei SZ, Zhu XD, Zhang XL. High glucose induces renal tubular epithelial cell senescence by inhibiting autophagic flux. Hum Cell. 2025;38:43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Ma Z, Li L, Livingston MJ, Zhang D, Mi Q, Zhang M, Ding HF, Huo Y, Mei C, Dong Z. p53/microRNA-214/ULK1 axis impairs renal tubular autophagy in diabetic kidney disease. J Clin Invest. 2020;130:5011-5026. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 163] [Article Influence: 32.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Pei Z, Chen Y, Zhang Y, Zhang S, Wen Z, Chang R, Ni B, Ni Q. Hirsutine mitigates ferroptosis in podocytes of diabetic kidney disease by downregulating the p53/GPX4 signaling pathway. Eur J Pharmacol. 2025;991:177289. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Cheng Y, Yang Q, Feng B, Yang X, Jin H. Roxadustat regulates the cell cycle and inhibits proliferation of mesangial cells via the hypoxia-inducible factor-1α/P53/P21 pathway. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2025;13:1503477. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Xia Y, Jiang H, Chen J, Xu F, Zhang G, Zhang D. Low dose Taxol ameliorated renal fibrosis in mice with diabetic kidney disease by downregulation of HIPK2. Life Sci. 2023;320:121540. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Guo W, Tian D, Jia Y, Huang W, Jiang M, Wang J, Sun W, Wu H. MDM2 controls NRF2 antioxidant activity in prevention of diabetic kidney disease. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res. 2018;1865:1034-1045. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Liu L, Wu M, Chen Y, Cheng Y, Liu S, Zhang X, Xie Q, Cao L, Wei L, Fang Y, Jafri A, Sferra TJ, Shen A, Li L. Downregulating FGGY carbohydrate kinase domain containing promotes cell senescence by activating the p53/p21 signaling pathway in colorectal cancer. Int J Mol Med. 2025;55:81. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Huang W, Hickson LJ, Eirin A, Kirkland JL, Lerman LO. Cellular senescence: the good, the bad and the unknown. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2022;18:611-627. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 352] [Cited by in RCA: 756] [Article Influence: 189.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Scott-Drechsel DE, Rugonyi S, Marks DL, Thornburg KL, Hinds MT. Hyperglycemia slows embryonic growth and suppresses cell cycle via cyclin D1 and p21. Diabetes. 2013;62:234-242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Al-Dabet MM, Shahzad K, Elwakiel A, Sulaj A, Kopf S, Bock F, Gadi I, Zimmermann S, Rana R, Krishnan S, Gupta D, Manoharan J, Fatima S, Nazir S, Schwab C, Baber R, Scholz M, Geffers R, Mertens PR, Nawroth PP, Griffin JH, Keller M, Dockendorff C, Kohli S, Isermann B. Reversal of the renal hyperglycemic memory in diabetic kidney disease by targeting sustained tubular p21 expression. Nat Commun. 2022;13:5062. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Li B, Sun G, Yu H, Meng J, Wei F. Exosomal circTAOK1 contributes to diabetic kidney disease progression through regulating SMAD3 expression by sponging miR-520h. Int Urol Nephrol. 2022;54:2343-2354. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/