Published online Feb 15, 2026. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v17.i2.112475

Revised: October 12, 2025

Accepted: November 27, 2025

Published online: February 15, 2026

Processing time: 193 Days and 4.2 Hours

Diabetic nephropathy (DN) is a major complication of diabetes, yet therapeutic strategies that specifically target its pathogenesis are still lacking.

To evaluate the therapeutic potential of fibroblast growth factor 1 (FGF1) in DN and explore its underlying mechanisms.

DN was induced in vivo using a type 2 diabetes mouse model, and in vitro using human kidney-2 (HK-2) cells treated with high glucose and palmitate acid (HGPA). Renal function, lipid accumulation and fibrosis were evaluated by urinary albumin creatinine ratio, Oil Red O staining and adipose differentiation-related protein expression, and Sirius Red staining, respectively. Oxygen consumption rate of HGPA-treated HK-2 cells with or without FGF1 was measured using the Seahorse XF Analyzer.

FGF1 treatment reduced urinary albumin excretion, ameliorated glomerular hypertrophy, attenuated renal fibrosis and inflammation, and diminished lipid accumulation in diabetic kidneys. Analysis of fatty acid metabolism revealed that cluster of differentiation 36, a key regulator of long-chain fatty acids uptake, was upregulated, while carnitine palmitoyl transferase 1A, a rate-limiting enzyme in fatty acid beta-oxidation (FAO), was downregulated in diabetic kidneys and HGPA-treated HK-2 cells. FGF1 treatment normalized the expression of both cluster of differentiation 36 and carnitine palmitoyl transferase 1A and enhanced FAO in HGPA-treated HK-2 cells. Mechanistically, FGF1 restored AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) activity and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha expression, both of which were suppressed in DN and HGPA-treated HK-2 cells. Notably, pharmacological inhibition of AMPK or FAO abolished the protective effect of FGF1.

FGF1 alleviates DN by inhibiting fatty acid uptake and promoting lipid catabolism via AMPK activation and FAO enhancement.

Core Tip: Fibroblast growth factor 1 (FGF1) can effectively ameliorate diabetic nephropathy as reflected by improved renal function and alleviation of kidney morphological abnormalities. FGF1 alleviates renal lipid accumulation, as evidenced by decreased triglyceride content and repressed adipose differentiation-related protein expression, via inhibiting fatty acid uptake and promoting lipid catabolism in diabetic kidney. Mechanical studies demonstrated that FGF1 modulates renal lipid metabolism via restoring AMP-activated protein kinase activity and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha expression.

- Citation: Li YJ, Ge HY, Zhang GG, Chen HY, Xi YJ, Wang K, Huang YL, Zhang C, Fan X, Yan XQ. Fibroblast growth factor 1 alleviates diabetic nephropathy by reducing renal lipid accumulation in diabetic kidney. World J Diabetes 2026; 17(2): 112475

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9358/full/v17/i2/112475.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4239/wjd.v17.i2.112475

Diabetic nephropathy (DN) is a major complication of both type 1 and type 2 diabetes and represents the leading cause of chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease[1]. With the global rise in diabetes prevalence, DN has become a significant public health concern. DN is characterized by a decline in glomerular filtration function[2] and marked albuminuria[3], often accompanied by renal and glomerular hypertrophy, fibrosis, and mesangial matrix expansion[4,5]. Diabetes promotes inflammation, oxidative stress, extracellular matrix protein accumulation, and renal fibrosis, ultimately leading to progressive renal dysfunction[6]. Current therapeutic strategies for DN mainly focus on intensive control of blood pressure and blood glucose, lipid lowering, and lifestyle and/or dietary modifications[4]. However, treatments that specifically target the underlying pathogenesis of DN remain limited[7]. Recent studies have shown lipid accumulation in the kidneys of DN patients[8] and in experimental animal models[9,10], which is believed to contribute to inflammation and renal injury[10-12]. Conversely, pharmacological inhibition of lipid accumulation by sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors[13] or nucleotide binding and oligomerization domain-containing protein, leucine-rich repeat-containing protein, and pyrin domain-containing protein 3 inflammasome-specific inhibitors[14] has shown protective effects in DN models, suggesting that lipid metabolism pathway may be a promising therapeutic target[15].

Fibroblast growth factor 1 (FGF1), a member of the paracrine FGF subfamily, has long been used clinically to promote skin wound healing, ulcer regeneration, ischemia recovery[16], and nerve repair[17]. More recently, FGF1 has attached attention for its unexpected metabolic roles[18], including regulation of metabolic homeostasis, insulin sensitization, and adipose tissue remodeling, thereby showing therapeutic potential in obesity[18], diabetes[19], and diabetic complications[20]. Our collaborators have previously demonstrated that both wild-type FGF1 and its non-mitogenic variant FGF1ΔHBS can prevent diabetic cardiomyopathy in mouse models[21,22]. Our recent findings also demonstrated FGF1ΔHBS improves nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in late-stage db/db mice. Furthermore, emerging evidence from our group and others suggests that FGF1 may protect against DN through anti-inflammatory[23] and anti-oxidative mechanisms[24]. However, the contribution of FGF1’s metabolic effects to this protection remains poorly understood.

In the present study, we demonstrate that FGF1 significantly delays the progression of DN in type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) mice, as evidenced by improved renal function and alleviation of kidney morphological abnormalities. Notably, FGF1 reduced lipid accumulation in diabetic kidney and high glucose and palmitate acid (HGPA)-treated renal tubule epithelial human kidney-2 (HK-2) cells by promoting fatty acid metabolism. These protective effects are mediated through the activation of carnitine palmitoyl transferase 1A (CPT1a) and AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) signaling pathways.

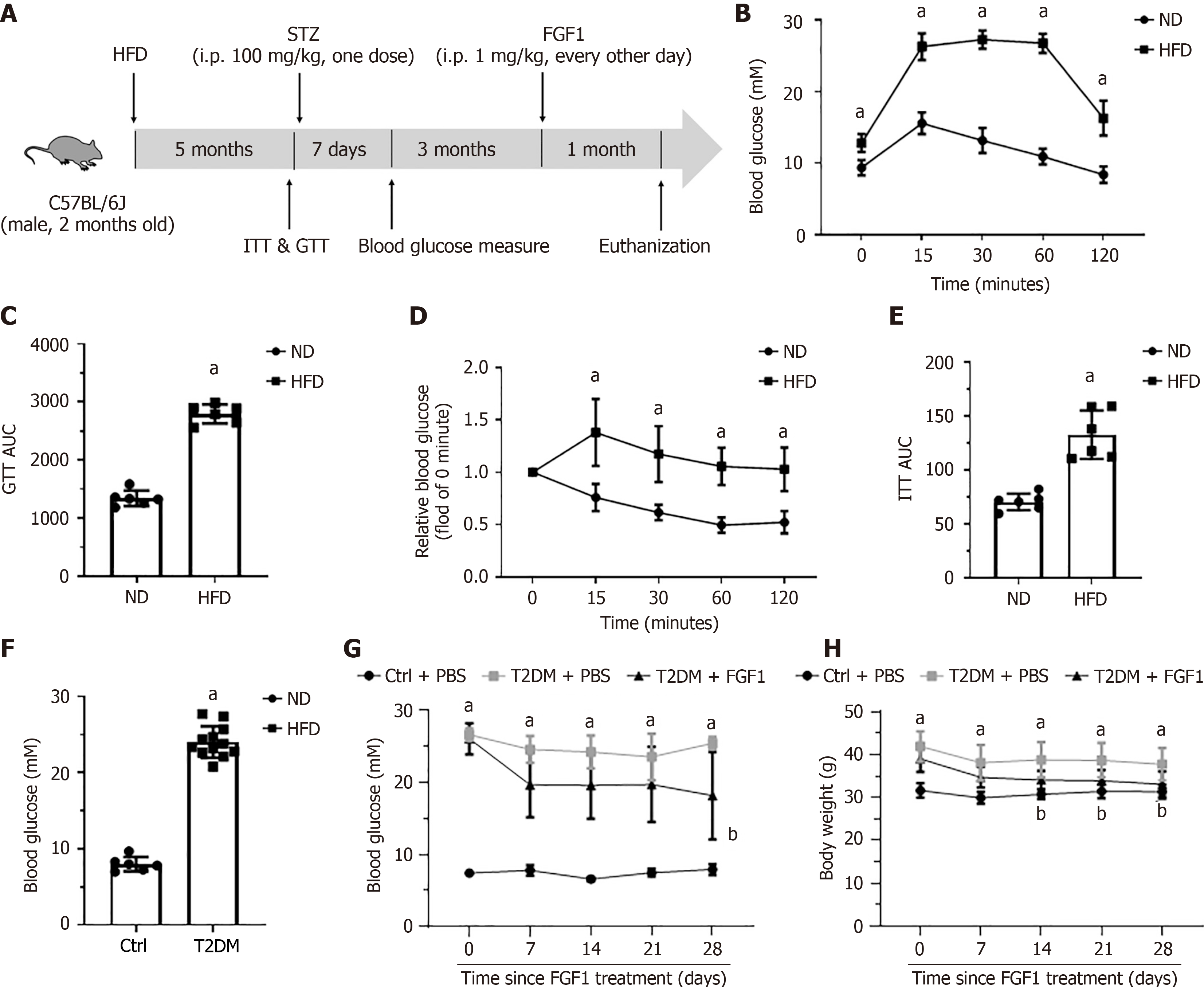

Eight-week-old male C57BL/6 mice (Charles River, Beijing, China) were used to establish T2DM mouse models. Mice were maintained at 22 ± 2 °C with a 12 hours light/dark cycle. T2DM in mice was induced by feeding high-fat diet (HFD) (60 kcal% fat, D12492, research diets, New Brunswick, NJ, United States) for 5 months followed by a single intraperitoneal injection of 100mg/kg streptozotocin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, United States). One-week post-injection, blood glucose levels were measured, and mice with blood glucose levels exceeding 13.7 mmol/L were considered diabetic. Control mice were fed a low-fat diet (10% kcal fat, D12450J, research diets) and injected with equivalent volume of saline. Three months after diabetes onset, T2DM mice were randomly divided into two groups: (1) T2DM + FGF1; and (2) T2DM + phosphate buffered saline (PBS). The T2DM + FGF1 group received intraperitoneal injections of FGF1 (0.5 mg/kg every other day), while the T2DM + PBS group received an equivalent volume of PBS. After one month of treatment, mice were sacrificed, and urine, plasma, and kidney tissues were collected for further analyses. All animal experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Wenzhou Medical University, and conducted in accordance with its guidelines.

Urinary albumin creatinine ratio (UACR) was used to evaluate kidney functions. Urine was collected before sacrifice. Urine albumin concentration was measured using a Microalbumin Assay Kit (H127-1-1, Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing, Jiangsu Province, China), and urine creatinine levels were measured using a Creatinine Assay Kit (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing, Jiangsu Province, China). UACR was calculated as: UACR = [urine albumin (μg/mL)]/[urine creatinine excretion (μmol/mL)].

Triglyceride (TG) levels in plasma, kidney tissues and human renal proximal tubular epithelial cells (HK-2) were measured using a Triglyceride Colorimetric Assay Kit (Cayman Chemical, Michigan, MI, United States). Plasma TG was detected following the manufacturer’s instructions. For TG detection in kidney, tissues were homogenized in assay reagent and lysed on ice for 30 minutes, followed by centrifugation at 13800 × g for 15 minutes at 4 °C. Supernatants were collected for TG and protein quantification. For TG detection in HK-2 cells, the assay reagent was added to the culture dish, cells were collected using a scraper, lysed on ice for 30 minutes, and centrifuged at 12000 rpm for 15 minutes at 4 °C. Supernatants were used for further assays. TG levels in kidney tissues and HK-2 cells were normalized to total protein content.

Kidney tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight, dehydrated in a graded alcohol series, cleared with xylene, and embedded in paraffin. Sections (5 μm) were deparaffinized, rehydrated and stained with hematoxylin and eosin to examine overall morphology, and with Masson’s trichrome and Sirius Red to assess fibrosis. For immunohistochemistry, sections were subjected to antigen retrieval in 10 mmol/L sodium citrate after de-paraffinization and rehydration. Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked with 3% hydrogen peroxide for 30 minutes. Sections were blocked with 5% fetal bovine serum for 1 hour, then incubated overnight at 4 °C with an anti-adipose differentiation-related protein (ADRP) primary antibody (1:100, Proteintech, 15294-1-AP, Wuhan, Hubei Province, China). After washing with PBST (PBS + 0.1% Triton X-100), sections were incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (1:100, ZENBIO, Chengdu, Sichuan Province, China) at room temperature for 1 hour. Staining was visualized using diaminobenzidine (A600140, Sangon Biotech), followed by hematoxylin counterstaining. Images were acquired using a Nikon light microscope (Tokyo, Japan).

HK-2 cells were cultured in DMEM/F12 (1:1) supplemented with 10% FBS (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, United States) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Solarbio, Beijing, China) at 37 °C with 5% CO2. A diabetic-like condition was mimicked using 30 mmol/L glucose and 100 μM palmitate (HGPA)[25]. HK-2 cells were treated with HGPA or vehicles in the presence or absence of FGF1 (100 ng/mL). For mechanistic studies, HK-2 cells were pre-treated for 30 minutes with either etomoxir [40 μM, mixed cellulose ester], a CPT1a selective inhibitor, or Compound C (10 μM, mixed cellulose ester), an AMPK inhibitor, before exposure to HGPA or vehicle.

Mitochondrial fatty acid beta-oxidation (FAO) was assessed using the Seahorse XFe96 Analyzer (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, United States) as previously described[26]. HK-2 cells (2 × 104/well) were plated in Seahorse XFe96 plates and treated as indicated. Oxygen consumption rate (OCR) was measured following sequential injections of oligomycin (1.5 μM), carbonyl cyanide-p-trifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone (1.5 μM), and rotenone/antimycin A (0.5 μM).

Lipid accumulation in HK-2 cells was detected by Oil Red O Staining Kit (Solarbio, Beijing, China). Cells were fixed in 10% buffered formalin for 30 minutes at room temperature, stained with Oil Red O for 1 hour, washed with 60% isopropanol, and counterstained with haematoxylin for 1 minute. Images were captured by light microscopy (Nikon).

HK-2 cells were seeded on glass slides and treated as indicated. Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 minutes at room temperature, permeabilized with 0.5% TritonX-100 for 5 minutes, blocked with 10% goat serum, and incubated overnight at 4 °C with anti-ADRP or anti-F4/80 antibody (1:200). After washing with PBST for three times, cells were incubated with fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1:100) at room temperature for 1 hour. Slides were mounted with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole containing medium and imaged using a fluorescence microscope (Nikon).

Western blot was performed as previously described. Kidney tissues or HK-2 cells were lysed in radio-immunoprecipitation assay buffer (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, United States) at 4 °C for 1 hour. Lysates were centrifuged at 12000 rpm for 15 minutes at 4 °C, and supernatants were collected and protein concentration was determined with a BCA kit (Beyotime, Shanghai, China). Equal amounts of protein were separated on 8%-10% sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gel and transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membrane (Merck). Membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat milk for 1 hour, then incubated overnight at 4 °C with the following primary antibodies against cluster of differentiation 36 (CD36) (1:1000, Abcam), CPT1a (1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology), β-tubulin (1:5000, Zen-bio), ADRP (1:500, Zen-bio), peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha (PPARα) (1:1000, Abcam). After 3 washes with tris-buffered saline (pH = 7.2) containing 0.05% tween 20 (TBST), membranes were incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies for 1 hour at room temperature. After 3 washes with TBST, protein bands were visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence detection kit (Solarbio, Beijing, China) and quantified using Image J. Band intensities were normalized to β-tubulin.

Total RNA was extracted from kidney tissues or HK-2 cells using an RNA Extraction Kit (Tiangen, Beijing, China). Total RNA (1 μg) was reverse-transcribed into complimentary DNA using a High-Capacity Complimentary DNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Takara, Beijing, China). RT-qPCR was performed using a SYBR Green PCR Master Mix Kit (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions on a QuantStudio3 Real-Time PCR Machine (Thermofisher, Waltham, MA, United States). The β-actin and GAPDH served as internal loading controls for kidney tissues and HK-2 cells, respectively. Primer sequences used are listed in Table 1.

| Name | Forward primer | Reverse primer |

| Mice β-actin | CTGACCGAGCGTGGCTACAG | GAGCCTCAGGGCATCGGAAC |

| Mice collagen IV | ATCCCTGGCTCACAGGGTGT | CTGGATGGCCGATGTTCCCC |

| Mice IL-1β | TGCTGGTGTGTGACGTTCCC | GGTGGGTGTGCCGTCTTTCA |

| Mice IL-6 | TGGTGACAACCACGGCCTTC | GCCTCCGACTTGTGAAGTGGT |

| Mice ADRP | TGACTGGCAGCGTGGAAAG | AGACAGGGACTCCAGCCGTT |

| Mice CPT1a | ACCCCTCCCTGGGCATGATT | CGGCTCATTTTGCCGTGCTC |

| Mice PPARα | GACCGTCACGGAGCTCACAG | CGCGATCAGCATCCCGTCTT |

| Human GAPDH | GCGGGGCTCTCCAGAACATC | TCCACCACTGACACGTTGGC |

| Human collagen IV | CCAGGACATCACCATCCCGC | TGCTGCCTCTCCTCCACTGT |

| Human IL-1β | ACAGCAAGGGCTTCAGGCAG | TGTCCCTGGAGGTGGAGAGC |

| Human IL-6 | GCCTTCGGTCCAGTTGCCTT | TGCCGTCGAGGATGTACCGA |

Data are represented as mean ± SD. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 8 software by one-way analysis of variance. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All experiments were independently repeated at least three times.

To assess the therapeutic efficacy of FGF1 in advanced DN associated with T2DM, a T2DM mouse model was established using 8-week-old male C57BL/6 mice (Figure 1A). After 5 months of HFD feeding, the glucose tolerance test and insulin tolerance test revealed impaired glucose and insulin tolerances compared to mice fed a normal diet (Figure 1B-E). Seven days after streptozotocin injection, blood glucose measurement showed a significant increase in blood glucose levels in HFD-fed mice compared to normal-diet-fed controls (Figure 1F). Following the onset of diabetes, HFD feeding continued for an additional 3 months, after which FGF1 was administered every other day for 1 month. Body weight and blood glucose levels were monitored throughout the treatment period. The results showed that the T2DM mice maintained hyperglycemia (Figure 1G) and elevated body weight (Figure 1H). In contrast, FGF1 treatment significantly reduced blood glucose level and body weight (Figure 1G and H).

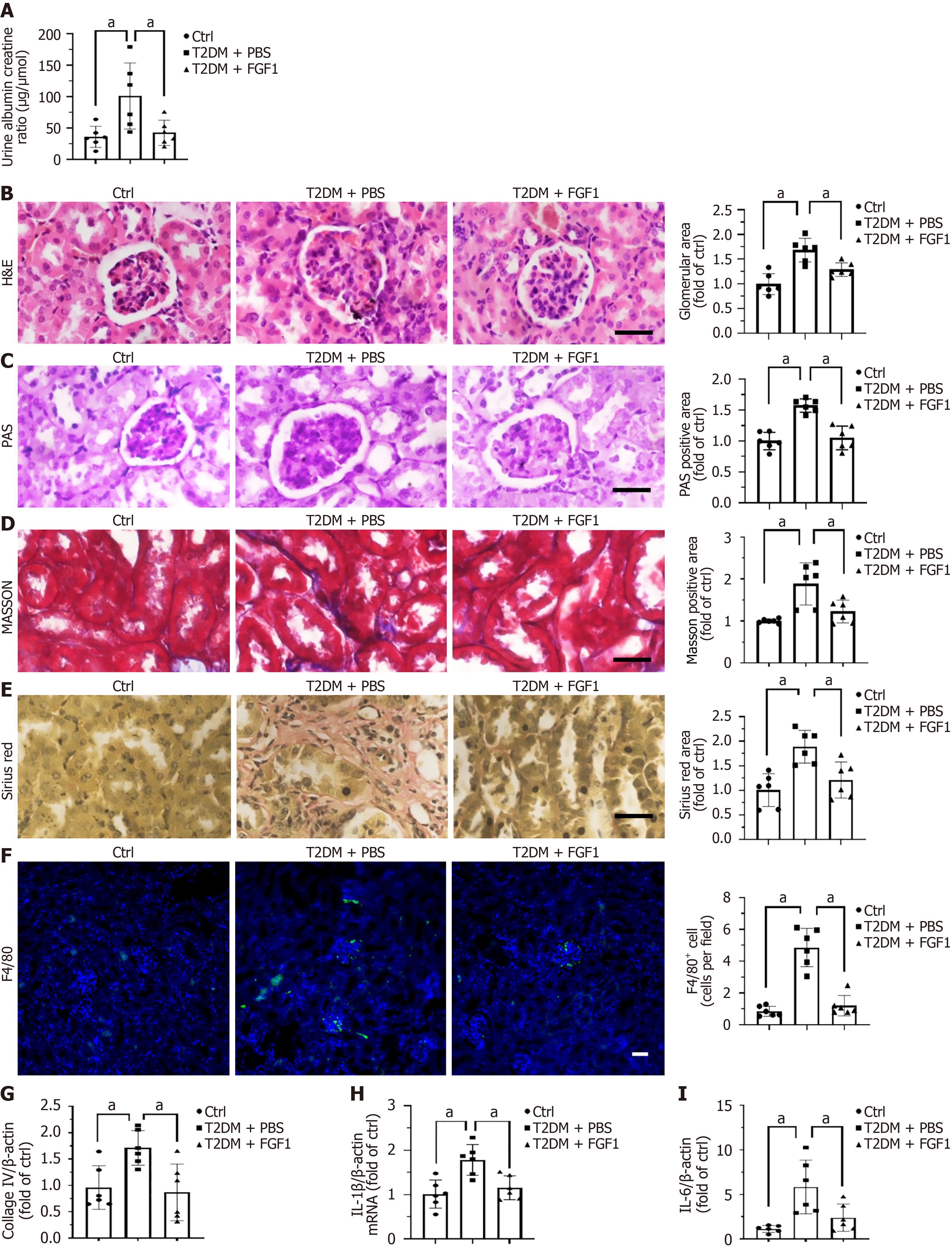

After 1 month of FGF1 treatment, urine samples were collected, and urine albumin and creatinine concentrations were measured (Figure 2). The results showed that FGF1 treatment significantly reduced the albumin-to-creatinine ratio in T2DM mice (Figure 2A). In addition, FGF1 administration improved renal histopathological features. Hematoxylin and eosin staining revealed glomerular enlargement in T2DM mice, which was markedly alleviated following FGF1 treatment (Figure 2B). Moreover, FGF1 treatment significantly reduced periodic acid–Schiff-positive staining areas in the glomeruli of T2DM mice, indicating attenuated mesangial matrix accumulation in glomeruli (Figure 2C). Both Masson’s trichrome staining (Figure 2D) and Sirius Red staining (Figure 2E) showed significantly reduced collagen deposition in renal tubules, further supported by decreased collagen IV mRNA expression (Figure 2G) in FGF1-treated T2DM mice, suggesting attenuation of renal fibrosis. Furthermore, FGF1 treatment also markedly reduced the expression of the inflammatory cytokines interleukin (IL)-1β and IL-6 in the kidney of T2DM mice (Figure 2H and I), as well as the infiltrated macrophage (Figure 2F). Together, these findings indicate that FGF1 improves diabetes-induced renal dysfunction, mitigates fibrosis, and suppresses renal inflammation.

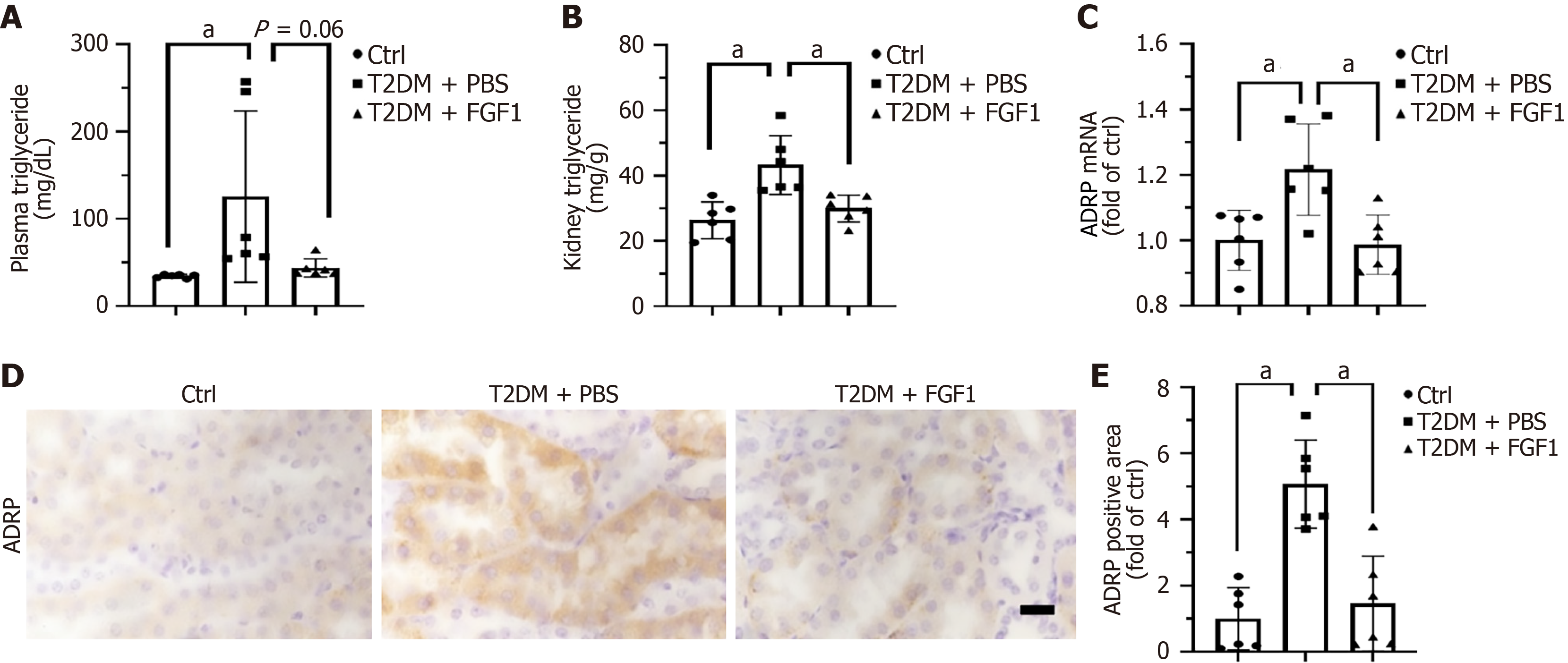

Lipid accumulation has emerged as a key pathophysiological mechanism in DN[27]. After confirming that FGF1 improves diabetes-induced renal dysfunction and histopathological changes, we evaluated its effects on lipid metabolism. First, we observed that FGF1 significantly reduced serum TG levels in T2DM mice (Figure 3A), suggesting its potential roles in mitigating systemic lipid dysregulation. To determine whether FGF1 directly reduces lipid accumulation in the kidney, we measured renal TG levels. The results showed a marked reduction in TG following FGF1 treatment in T2DM mice (Figure 3B). Additionally, ADRP, a structural component of lipid droplets known to promote lipid accumulation and droplet formation, was used as a marker for lipid accumulation[11]. Both RT-qPCR (Figure 3C) and immunohistochemical analysis (Figure 3D and E) results revealed that ADRP expression was elevated in the kidneys of T2DM mice but significantly reduced after FGF1 treatment. Immunohistochemical analysis revealed that ADRP expression was elevated in the kidneys of T2DM mice but significantly reduced after FGF1 treatment (Figure 3D). These results indicate that FGF1 effectively reduces lipid accumulation in the kidney of T2DM mice. Moreover, ADRP expression was primarily localized in renal tubules (Figure 3D), indicating that lipid accumulation predominantly occurs in the tubular compartment.

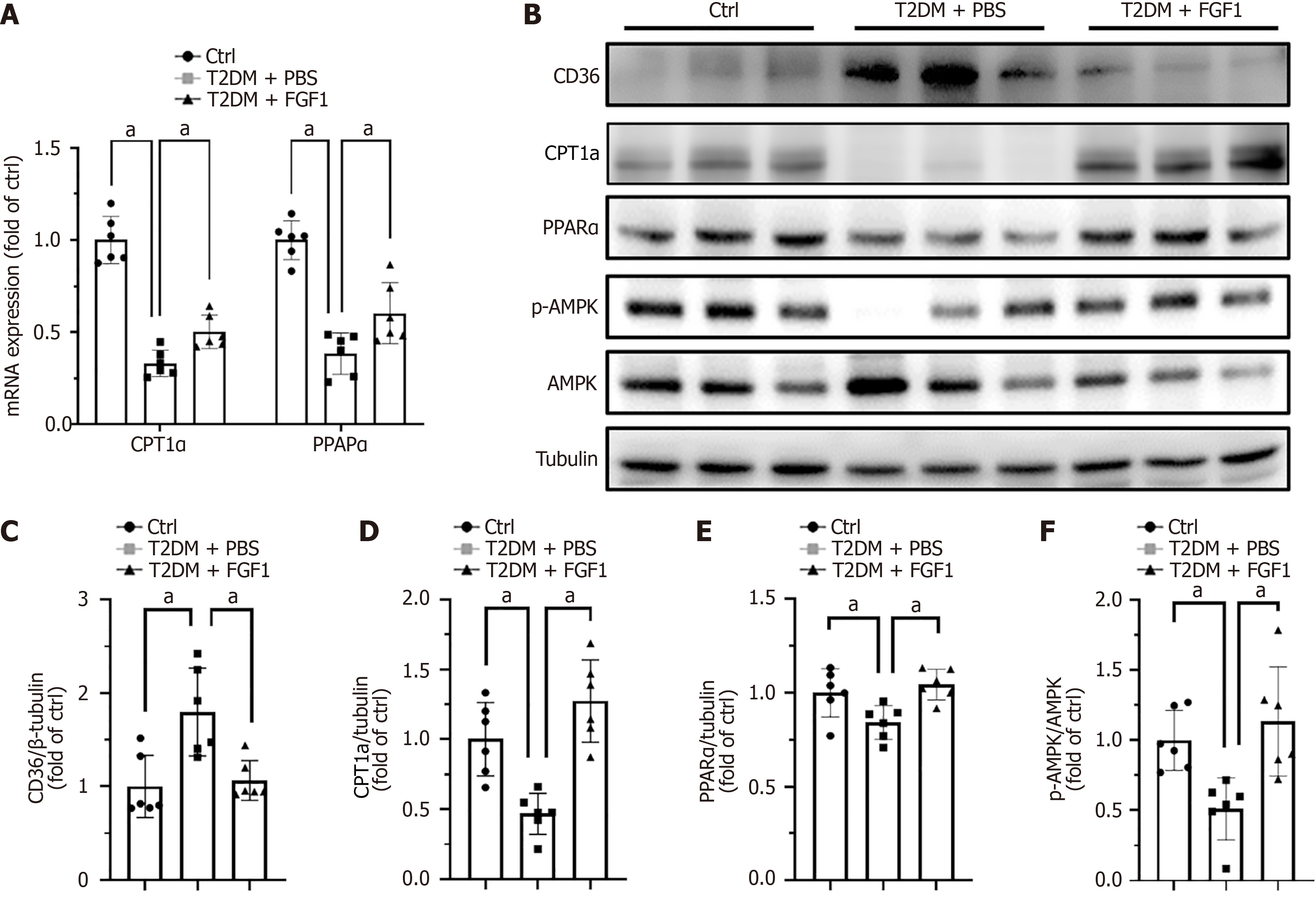

As noted above, FGF1 reduced lipid accumulation in the kidney. Based on this observation, we investigated whether FGF1 regulates the expression of genes involved in fatty acid metabolism in the kidneys of T2DM mice. The mRNA expression levels of CPT1a and PPARα, two key genes in fatty acid metabolism, were significantly upregulated by FGF1 (Figure 4A). Lipid homeostasis in the kidney is maintained by a dynamic balance between lipid uptake and lipid metabolism. Disruption of this balance can lead to lipid accumulation[28]. To explore how FGF1 affects lipid accumulation in DN, we examined the expression or activation of key proteins involved in lipid uptake and metabolism. The expression of CD36, a fatty acid translocase responsible for the uptake of long-chain fatty acids in the kidney[29], was elevated in T2DM kidneys and was reversed following FGF1 treatment (Figure 4B and C). Conversely, FAO, the primary pathway for fatty acid metabolism in tubular epithelial cells[27], is regulated by CPT1a, a critical rate-limiting enzyme that mediates fatty acid transport into mitochondria[30]. The expression of CPT1a was markedly reduced in the kidney of T2DM mice and restored by FGF1 treatment (Figure 4B and D). In addition, FAO is tightly regulated by several signaling molecules, including PPARα and AMPK[28]. In our study, PPARα expression was significantly downregulated in the kidney of T2DM mice but restored by FGF1 treatment (Figure 4B and E). A similar pattern was observed for AMPK activation (Figure 4B and F). These findings suggest that FGF1 may ameliorate lipid accumulation in the kidney by simultaneously decreasing lipid uptake and enhancing fatty acid metabolism.

To determine whether the beneficial effects of FGF1 on renal function and lipid accumulation in kidney are mediated through the correction of hyperlipidemia or via a direct action on renal tubules, we investigated the effects of FGF1 on HK-2 cells, a human renal tubular epithelial cell line. HK-2 cells were treated with culture medium containing 30 mmol/L glucose and 100 μM palmitate (HGPA) to mimic the hyperglycemic and hyperlipidemic conditions characteristic of T2DM. HGPA treatment significantly increased collagen IV expression in HK-2 cells, whereas FGF1 administration markedly reduced this effect (Figure 5A). In addition, FGF1 repressed HGPA-induced upregulation of the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β (Figure 5B) and IL-6 (Figure 5C). These findings indicate that FGF1 alleviates fibrosis and inflammation in renal tubular cells, in line with our in vivo observations in T2DM mice. Furthermore, HGPA treatment led to a marked increase in intracellular TG content, which was significantly reduced following FGF1 treatment (Figure 5D). Oil Red O staining confirmed that the lipid accumulation induced by HGPA was attenuated by FGF1 treatment (Figure 5E and F). Immunofluorescence analysis revealed that the elevated expression of ADRP observed in HGPA-treated HK-2 cells was also diminished after FGF1 treatment (Figure 5G and H), which was further validated by RT-qPCR (Figure 5I) and western blot (Figure 5J and K). Collectively, these results demonstrate that FGF1 can directly act on renal tubular cells to alleviate fibrosis, inflammation, and lipid accumulation under diabetic-like conditions.

Given that FGF1 regulates the gene expression involved in fatty acid metabolism and ameliorates lipid accumulation in the kidneys of T2DM mice, we investigated whether FGF1 could similarly enhance lipid metabolism and FAO in HGPA-treated HK-2 cells. First, FAO activation was assessed using a Seahorse XFe96 Analyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, United States). The results showed that HGPA-treated HK-2 cells administered with FGF1 exhibited higher baseline OCRs and greater carbonyl cyanide-4 (trifluoromethoxy) phenylhydrazone-induced increases in OCRs, indicating that FGF1 enhanced fatty acid metabolic activity in these cells (Figure 6A and B). Furthermore, the expression levels of CD36 (Figure 6C and D), CPT1a (Figure 6C and E), and PPARα (Figure 6C and F), along with AMPK activation (Figure 6C and G), were all suppressed by HGPA treatment but were restored following FGF1 administration. These findings suggest that FGF1 alleviates lipid accumulation in DN by modulating the expression of genes involved in fatty acid metabolism.

To confirm the importance of regulating FAO in FGF1-induced amelioration of lipid accumulation, FAO was inhibited using etomoxir, a CPT1a antagonist. Pretreatment with etomoxir significantly increased the TG content in HGPA + FGF1-treated HK-2 cells (Figure 7A). Consistent results were observed with Oil Red O staining (Figure 7B and C) and ADRP expression, as detected by both immunofluorescence (Figure 7D and E) and western blot (Figure 7F and G). These findings indicate that inhibition of FAO compromises the lipid-lowering effect of FGF1, underscoring the essential role of FAO in mediating FGF1’s protective action against lipid accumulation in DN.

To further elucidate the mechanism by which FGF1 regulates lipid accumulation, we assessed the expression of key proteins involved in FAO. The AMPK pathway is known to play a critical role in lipid metabolism[31]. To confirm the involvement of AMPK in the lipid-lowering effects of FGF1, we used compound C, an AMPK inhibitor, to inhibit AMPK pathway. Treatment with compound C reversed the beneficial effects of FGF1, as evidenced by increased Oil Red O staining (Figure 8A and B), elevated TG content (Figure 8C), and upregulated ADRP expression (Figure 8D and E) in HGPA + FGF1-treated HK-2 cells. These findings suggest that the inhibition of AMPK abolishes the lipid-lowering effect of FGF1 in HGPA-treated HK-2 cells.

DN is one of the most common complications in diabetes. It is widely believed that inflammation, oxidative stress, the accumulation of extracellular matrix proteins, and renal fibrosis under diabetic conditions contribute to the development and progression of DN, ultimately leading to renal dysfunction[6]. However, the mechanistic links between metabolic disorders in diabetes and renal inflammation remain poorly understood. Previous studies have shown that lipid accumulation occurs in the kidneys of both DN patients and diabetic animal models[8,10], and that ectopic lipid deposition promotes inflammation and tubular injury in DN[11]. In the present study, we demonstrated that FGF1 treatment mar

The kidney plays a key role in maintaining internal homeostasis by excreting metabolic waste; regulating the water, electrolyte, and acid-base balance; and performing endocrine functions. Approximately 70% of glomerular filtrate and its solutes are reabsorbed in the proximal tubules, a process requiring significant energy expenditure[28]. Consequently, proximal tubular epithelial cells are rich in mitochondria and primarily rely on FAO for energy. Lipid homeostasis in the kidney is maintained by a dynamic balance between lipid uptake and FAO. Notably, FAO dysregulation has been implicated in kidney disease pathogenesis; its impairment can promote fibrosis[32], while enhancing FAO has been shown to attenuate it[33]. Several studies have reported suppressed FAO in diabetic kidneys due to hyperglycemia, hyperlipidemia, and elevated levels of advanced glycation end products[8,10] Notably, Rong et al[34] found that berberine reduces lipid accumulation in diabetic kidney by promoting FAO in renal tubular epithelial cells. Consistent with this, our data show that FGF1 enhances FAO in HK-2 cells (Figure 6A and B), contributing to its protective effect against DN. Together with findings from other studies, our results underscore the importance of FAO in defending against DN and other kidney diseases.

Pharmacological inhibition of FAO, for example by blocking CPT1a, leads to increased renal lipid accumulation, whereas CPT1a overexpression promotes FAO and mitigates lipid accumulation[33]. This research indicates that promoting FAO is a promising therapeutic strategy for DN. We also found that inhibiting CPT1a expression abolished the ability of FGF1 to reduce lipid accumulation (Figure 7), suggesting that FGF1 promotes FAO by upregulating CPT1a expression. Several key metabolic regulators, including PPAR-α and AMPK, are known to modulate FAO[28]. Xie et al[32] reported that AMPK plays a crucial role in alleviating kidney fibrosis via FAO promotion, while Wu et al[31] demonstrated that annexin A1 attenuates DN by enhancing lipid metabolism through the AMPK/PPARα pathway. Our previous studies showed that FGF1ΔHBS activates AMPK in diabetic heart[21] and PPARα in diabetic kidney[4]. In this study, we observed that AMPK activation was suppressed in DN (Figure 4B and F) and HGPA-treated HK-2 cells but was restored following FGF1 treatment (Figure 6C and G). Notably, the inhibition of AMPK reversed FGF1’s protective effect against lipid accumulation (Figure 6D-G), indicating that AMPK activation mediates the FGF1-induced enhancement of FAO.

In addition to promoting FAO, improvement in systemic lipid profiles and reduced fatty acid uptake may also contribute to the renoprotective effects of FGF1. The metabolic effects of FGF1 have been well documented[23,35]. In this study, we found that FGF1 improves dyslipidemia in diabetic mice (Figure 3A). CD36, a key fatty acid translocase responsible for long-chain fatty acid uptake in kidney[29], was upregulated in both diabetic kidneys (Figure 4B) and HK-2 cells (Figure 6C). FGF1 downregulated CD36 expression in both contexts, thereby limiting lipid uptake and accumulation in the kidney. Clinical translation of FGF1 has been limited by its mitogenic activity, which raises concerns about tumorigenesis[36]. Fortunately, our recent study showed that a mutant form of FGF1 lacking its three heparin-binding sites (FGF1ΔHBS) retains full metabolic activity but exhibits significantly reduced mitogenic potential[37], offering a safer alternative for therapeutic development.

Our study reveals that FGF1 significantly attenuates the progression of DN and protects proximal tubular epithelial cells in T2DM mice. This protective effect is mediated through enhanced FAO and reduced lipid accumulation via AMPK activation, along with suppression of CD36 expression (Figure 8F).

| 1. | Cai T, Ke Q, Fang Y, Wen P, Chen H, Yuan Q, Luo J, Zhang Y, Sun Q, Lv Y, Zen K, Jiang L, Zhou Y, Yang J. Sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibition suppresses HIF-1α-mediated metabolic switch from lipid oxidation to glycolysis in kidney tubule cells of diabetic mice. Cell Death Dis. 2020;11:390. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 138] [Article Influence: 23.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Cohen MP, Lautenslager GT, Shearman CW. Increased urinary type IV collagen marks the development of glomerular pathology in diabetic d/db mice. Metabolism. 2001;50:1435-1440. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Sharma K, McCue P, Dunn SR. Diabetic kidney disease in the db/db mouse. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2003;284:F1138-F1144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 326] [Cited by in RCA: 396] [Article Influence: 17.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Lin Q, Chen O, Wise JP Jr, Shi H, Wintergerst KA, Cai L, Tan Y. FGF1(ΔHBS) delays the progression of diabetic nephropathy in late-stage type 2 diabetes mouse model by alleviating renal inflammation, fibrosis, and apoptosis. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 2022;1868:166414. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Hong SW, Isono M, Chen S, Iglesias-De La Cruz MC, Han DC, Ziyadeh FN. Increased glomerular and tubular expression of transforming growth factor-beta1, its type II receptor, and activation of the Smad signaling pathway in the db/db mouse. Am J Pathol. 2001;158:1653-1663. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 157] [Cited by in RCA: 168] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Wang Y, Wang Y, Luo M, Wu H, Kong L, Xin Y, Cui W, Zhao Y, Wang J, Liang G, Miao L, Cai L. Novel curcumin analog C66 prevents diabetic nephropathy via JNK pathway with the involvement of p300/CBP-mediated histone acetylation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1852:34-46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Samsu N. Diabetic Nephropathy: Challenges in Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Biomed Res Int. 2021;2021:1497449. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 605] [Article Influence: 121.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Herman-Edelstein M, Scherzer P, Tobar A, Levi M, Gafter U. Altered renal lipid metabolism and renal lipid accumulation in human diabetic nephropathy. J Lipid Res. 2014;55:561-572. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 281] [Cited by in RCA: 522] [Article Influence: 40.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Wang Z, Jiang T, Li J, Proctor G, McManaman JL, Lucia S, Chua S, Levi M. Regulation of renal lipid metabolism, lipid accumulation, and glomerulosclerosis in FVBdb/db mice with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2005;54:2328-2335. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 214] [Cited by in RCA: 257] [Article Influence: 12.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Yuan Y, Sun H, Sun Z. Advanced glycation end products (AGEs) increase renal lipid accumulation: a pathogenic factor of diabetic nephropathy (DN). Lipids Health Dis. 2017;16:126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Yang W, Luo Y, Yang S, Zeng M, Zhang S, Liu J, Han Y, Liu Y, Zhu X, Wu H, Liu F, Sun L, Xiao L. Ectopic lipid accumulation: potential role in tubular injury and inflammation in diabetic kidney disease. Clin Sci (Lond). 2018;132:2407-2422. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Zhang Y, Ma KL, Liu J, Wu Y, Hu ZB, Liu L, Lu J, Zhang XL, Liu BC. Inflammatory stress exacerbates lipid accumulation and podocyte injuries in diabetic nephropathy. Acta Diabetol. 2015;52:1045-1056. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Wang XX, Levi J, Luo Y, Myakala K, Herman-Edelstein M, Qiu L, Wang D, Peng Y, Grenz A, Lucia S, Dobrinskikh E, D'Agati VD, Koepsell H, Kopp JB, Rosenberg AZ, Levi M. SGLT2 Protein Expression Is Increased in Human Diabetic Nephropathy: SGLT2 Protein Inhibition Decreases Renal Lipid Accumulation, Inflammation, and the Development of Nephropathy in Diabetic Mice. J Biol Chem. 2017;292:5335-5348. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 171] [Cited by in RCA: 261] [Article Influence: 29.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Wu M, Yang Z, Zhang C, Shi Y, Han W, Song S, Mu L, Du C, Shi Y. Inhibition of NLRP3 inflammasome ameliorates podocyte damage by suppressing lipid accumulation in diabetic nephropathy. Metabolism. 2021;118:154748. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Article Influence: 27.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Shen Y, Chen W, Han L, Bian Q, Fan J, Cao Z, Jin X, Ding T, Xian Z, Guo Z, Zhang W, Ju D, Mei X. VEGF-B antibody and interleukin-22 fusion protein ameliorates diabetic nephropathy through inhibiting lipid accumulation and inflammatory responses. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2021;11:127-142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Nabel EG, Yang ZY, Plautz G, Forough R, Zhan X, Haudenschild CC, Maciag T, Nabel GJ. Recombinant fibroblast growth factor-1 promotes intimal hyperplasia and angiogenesis in arteries in vivo. Nature. 1993;362:844-846. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 276] [Cited by in RCA: 261] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Ni HC, Tseng TC, Chen JR, Hsu SH, Chiu IM. Fabrication of bioactive conduits containing the fibroblast growth factor 1 and neural stem cells for peripheral nerve regeneration across a 15 mm critical gap. Biofabrication. 2013;5:035010. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Jonker JW, Suh JM, Atkins AR, Ahmadian M, Li P, Whyte J, He M, Juguilon H, Yin YQ, Phillips CT, Yu RT, Olefsky JM, Henry RR, Downes M, Evans RM. A PPARγ-FGF1 axis is required for adaptive adipose remodelling and metabolic homeostasis. Nature. 2012;485:391-394. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 193] [Cited by in RCA: 231] [Article Influence: 16.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Scarlett JM, Rojas JM, Matsen ME, Kaiyala KJ, Stefanovski D, Bergman RN, Nguyen HT, Dorfman MD, Lantier L, Wasserman DH, Mirzadeh Z, Unterman TG, Morton GJ, Schwartz MW. Central injection of fibroblast growth factor 1 induces sustained remission of diabetic hyperglycemia in rodents. Nat Med. 2016;22:800-806. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Huang HW, Yang CM, Yang CH. Beneficial Effects of Fibroblast Growth Factor-1 on Retinal Pigment Epithelial Cells Exposed to High Glucose-Induced Damage: Alleviation of Oxidative Stress, Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress, and Enhancement of Autophagy. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25:3192. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Wang D, Yin Y, Wang S, Zhao T, Gong F, Zhao Y, Wang B, Huang Y, Cheng Z, Zhu G, Wang Z, Wang Y, Ren J, Liang G, Li X, Huang Z. FGF1(ΔHBS) prevents diabetic cardiomyopathy by maintaining mitochondrial homeostasis and reducing oxidative stress via AMPK/Nur77 suppression. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2021;6:133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 16.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Zhao YZ, Zhang M, Wong HL, Tian XQ, Zheng L, Yu XC, Tian FR, Mao KL, Fan ZL, Chen PP, Li XK, Lu CT. Prevent diabetic cardiomyopathy in diabetic rats by combined therapy of aFGF-loaded nanoparticles and ultrasound-targeted microbubble destruction technique. J Control Release. 2016;223:11-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Liang G, Song L, Chen Z, Qian Y, Xie J, Zhao L, Lin Q, Zhu G, Tan Y, Li X, Mohammadi M, Huang Z. Fibroblast growth factor 1 ameliorates diabetic nephropathy by an anti-inflammatory mechanism. Kidney Int. 2018;93:95-109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 15.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Wang D, Jin M, Zhao X, Zhao T, Lin W, He Z, Fan M, Jin W, Zhou J, Jin L, Zheng C, Jin H, Zhao Y, Li X, Ying L, Wang Y, Zhu G, Huang Z. FGF1(ΔHBS) ameliorates chronic kidney disease via PI3K/AKT mediated suppression of oxidative stress and inflammation. Cell Death Dis. 2019;10:464. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Dai X, Wang K, Fan J, Liu H, Fan X, Lin Q, Chen Y, Chen H, Li Y, Liu H, Chen O, Chen J, Li X, Ren D, Li J, Conklin DJ, Wintergerst KA, Li Y, Cai L, Deng Z, Yan X, Tan Y. Nrf2 transcriptional upregulation of IDH2 to tune mitochondrial dynamics and rescue angiogenic function of diabetic EPCs. Redox Biol. 2022;56:102449. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Liu L, Ning X, Wei L, Zhou Y, Zhao L, Ma F, Bai M, Yang X, Wang D, Sun S. Twist1 downregulation of PGC-1α decreases fatty acid oxidation in tubular epithelial cells, leading to kidney fibrosis. Theranostics. 2022;12:3758-3775. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 15.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | van der Rijt S, Leemans JC, Florquin S, Houtkooper RH, Tammaro A. Immunometabolic rewiring of tubular epithelial cells in kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2022;18:588-603. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Gao Z, Chen X. Fatty Acid β-Oxidation in Kidney Diseases: Perspectives on Pathophysiological Mechanisms and Therapeutic Opportunities. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:805281. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Zhao J, Rui HL, Yang M, Sun LJ, Dong HR, Cheng H. CD36-Mediated Lipid Accumulation and Activation of NLRP3 Inflammasome Lead to Podocyte Injury in Obesity-Related Glomerulopathy. Mediators Inflamm. 2019;2019:3172647. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Schlaepfer IR, Joshi M. CPT1A-mediated Fat Oxidation, Mechanisms, and Therapeutic Potential. Endocrinology. 2020;161:bqz046. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 171] [Cited by in RCA: 510] [Article Influence: 85.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Wu L, Liu C, Chang DY, Zhan R, Zhao M, Man Lam S, Shui G, Zhao MH, Zheng L, Chen M. The Attenuation of Diabetic Nephropathy by Annexin A1 via Regulation of Lipid Metabolism Through the AMPK/PPARα/CPT1b Pathway. Diabetes. 2021;70:2192-2203. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 16.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Xie YH, Xiao Y, Huang Q, Hu XF, Gong ZC, Du J. Role of the CTRP6/AMPK pathway in kidney fibrosis through the promotion of fatty acid oxidation. Eur J Pharmacol. 2021;892:173755. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Miguel V, Tituaña J, Herrero JI, Herrero L, Serra D, Cuevas P, Barbas C, Puyol DR, Márquez-Expósito L, Ruiz-Ortega M, Castillo C, Sheng X, Susztak K, Ruiz-Canela M, Salas-Salvadó J, González MAM, Ortega S, Ramos R, Lamas S. Renal tubule Cpt1a overexpression protects from kidney fibrosis by restoring mitochondrial homeostasis. J Clin Invest. 2021;131:e140695. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 223] [Cited by in RCA: 257] [Article Influence: 51.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Rong Q, Han B, Li Y, Yin H, Li J, Hou Y. Berberine Reduces Lipid Accumulation by Promoting Fatty Acid Oxidation in Renal Tubular Epithelial Cells of the Diabetic Kidney. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12:729384. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Yan X, Su Y, Fan X, Chen H, Lu Z, Liu Z, Li Y, Yi M, Zhang G, Gu C, Wang K, Wu J, Sun D, Zhang Y, Zhang C, Dai X, Zheng C. Liraglutide Improves the Angiogenic Capability of EPC and Promotes Ischemic Angiogenesis in Mice under Diabetic Conditions through an Nrf2-Dependent Mechanism. Cells. 2022;11:3821. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Liu Z, Hartman YE, Warram JM, Knowles JA, Sweeny L, Zhou T, Rosenthal EL. Fibroblast growth factor receptor mediates fibroblast-dependent growth in EMMPRIN-depleted head and neck cancer tumor cells. Mol Cancer Res. 2011;9:1008-1017. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Huang Z, Tan Y, Gu J, Liu Y, Song L, Niu J, Zhao L, Srinivasan L, Lin Q, Deng J, Li Y, Conklin DJ, Neubert TA, Cai L, Li X, Mohammadi M. Uncoupling the Mitogenic and Metabolic Functions of FGF1 by Tuning FGF1-FGF Receptor Dimer Stability. Cell Rep. 2017;20:1717-1728. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/