Published online Feb 15, 2026. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v17.i2.112859

Revised: September 22, 2025

Accepted: November 20, 2025

Published online: February 15, 2026

Processing time: 183 Days and 4 Hours

Diabetic gastrointestinal autonomic neuropathy (DGAN) is a common yet under

To identify potential metabolite biomarkers capable of identifying DGAN among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM).

This cross-sectional study included 26 patients with clinically defined DGAN and 69 patients with uncomplicated T2DM. Fifteen individual BAs were quantified in fasting serum using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Gastro

Orthogonal partial least squares discriminant analysis of serum BAs revealed clear separation between the T2DM and DGAN groups, identifying taurolitho

These findings highlighted the association between altered BA profiles and DGAN in patients with T2DM. Combining BA profiling with conventional clinical data could facilitate the early identification of DGAN and offer new insights into early screening and BA-targeted interventions. While these findings offer valuable insights, they should nevertheless be viewed as hypothesis-generating and require further validation in larger, multicenter cohorts.

Core Tip: This study revealed an association between altered bile acid (BA) profiles and diabetic gastrointestinal autonomic neuropathy. Combining BA profiling with conventional clinical data could facilitate the early identification of DGAN and offer new insights into early screening and BA-targeted interventions.

- Citation: Zhu KY, Wang SJ, Li J, Ma PP, Feng SS, Guo L, Lu YB, Dong L, Ding DF. Association of serum bile acid profiles with the risk of gastrointestinal autonomic neuropathy in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. World J Diabetes 2026; 17(2): 112859

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9358/full/v17/i2/112859.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4239/wjd.v17.i2.112859

Diabetic gastrointestinal autonomic neuropathy (DGAN), traditionally represented by diabetic gastroparesis, is one of the most common diabetic complications[1]. Its pre

Patients with DGAN experience significant distress owing to recurrent gastro

Gastric emptying scintigraphy, the diagnostic gold standard[7], has limited availability because of the requirement for specialized nuclear medicine equipment. This technique is also associated with radiation exposure and high costs, and it is contraindicated in both children and pregnant females. Moreover, this technique evaluates gastric emptying but not pan-enteric function, and it often reveals a poor correlation between symptom severity and gastric emptying abnormalities[8].

Breath tests and acoustic imaging exhibit limited accuracy because of interference from pulmonary/hepatic dysfunction and medications (e.g., antacids, antibiotics), thus displaying 30%-40% discordance rates compared with scintigraphy[9,10]. Wireless capsule endoscopy and pressure mapping are cost-prohibitive[11], and they lack standar

Non-invasive, low-cost diagnostic tools suitable for population-level applications that can detect abnormalities prior to symptom onset are urgently needed. Thus, combining peripheral blood metabolic markers with conventional risk factors could be useful for developing early risk stratification models. Longitudinal studies demonstrated positive correlations among delayed gastric emptying, persistent elevation of glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), and frequent acute hypergly

In diabetes chronic intestinal inflammation, mucosal barrier disruption, and gastrointestinal dysbiosis collectively disrupt bile acid (BA) metabolism and transport[18]. Hepatocyte-synthesized BAs enter the small intestine for digestive functions, undergo ileal reabsorption, and return to the liver via enterohepatic circulation. Physiologically, < 5% of circulating BAs reach the colon. However, excessive ileal BA delivery or reabsorption failure increases colonic BA influx, thereby altering secretion and motility and causing BA malabsorption[19] and BA diarrhea[20]. BA dysregulation induces enteric neuropathy and motility disorders[21,22]. However, the relationship between BA alterations and gastrointestinal motility, specifically in DGAN, remains unclear.

In this hospital-based cross-sectional study, we aimed to characterize the serum BA profile in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) with or without DGAN and explore its correlation with gastrointestinal motility parameters and clinical indicators, establish an early risk stratification model for DGAN based on altered BA metabolism in patients with T2DM, and identify specific BA species that are highly associated with DGAN risk and elucidate their potential roles in the pathogenesis of gastrointestinal dysmotility.

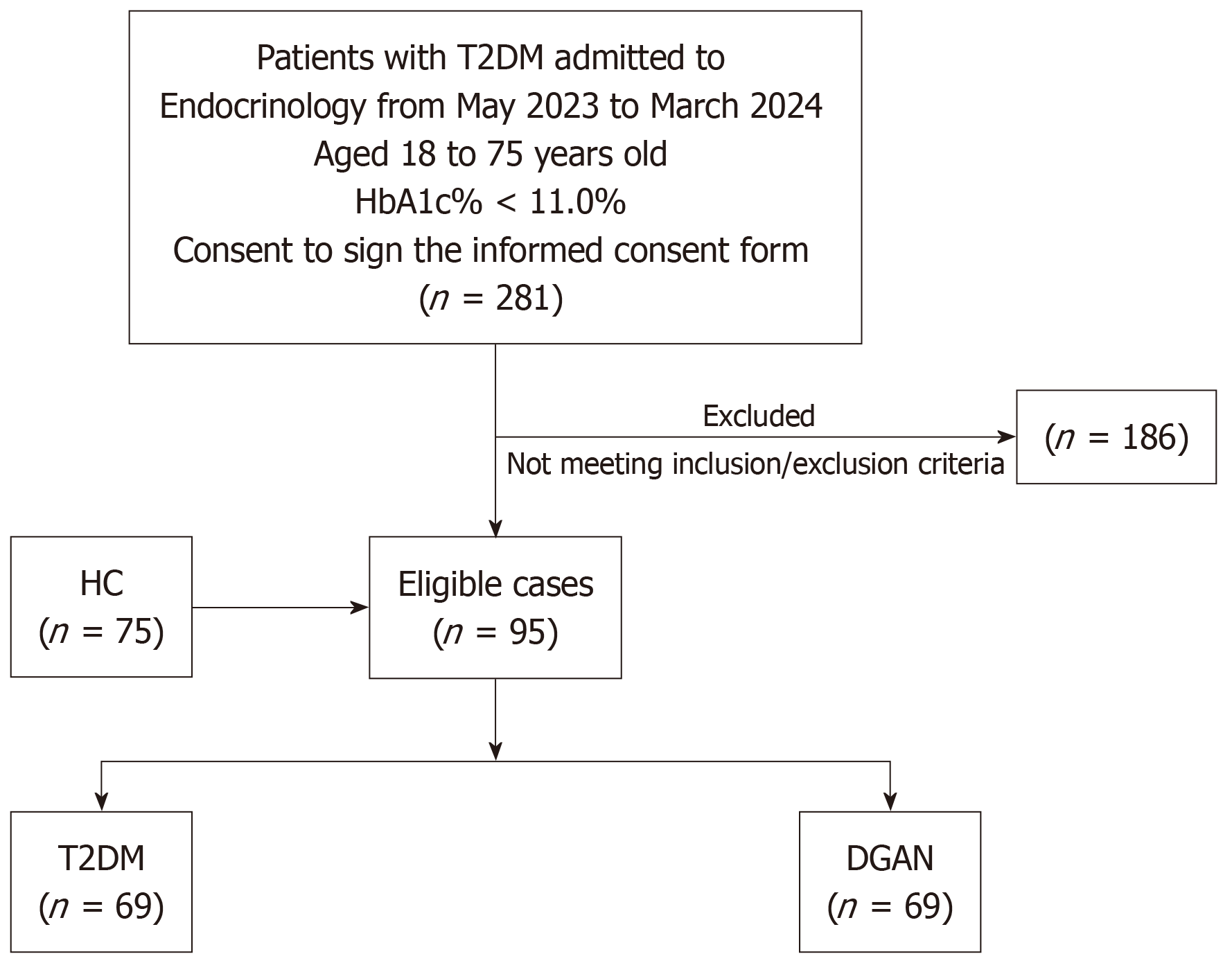

In total 26 patients diagnosed with DGAN and 69 patients with uncomplicated T2DM were selected from the Endocrinology Department of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University between May 2023 and March 2024. Additionally, 75 healthy controls (HCs) who underwent health examinations at the Physical Examination Center of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University were included in the study. The flow diagram of participant inclusion is illustrated is Figure 1. This study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University (2024-KY-232-01).

The inclusion criteria were as follows: Age of 18-75 years; meeting the 1999 World Health Organization diagnostic criteria for T2DM; HbA1c < 11.0%; and available complete clinical parameters and metagenomic data. The exclusion criteria were as follows: History of antibiotic use for > 3 consecutive days within 6 weeks prior to recruitment; probiotic/prebiotic/synbiotic supplementation within 12 weeks; presence of clinically significant psychiatric/neurological disorders or epilepsy; comorbid gastrointestinal disorders (e.g., irritable bowel syndrome, ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease, gastrointestinal malignancies, thyroid dysfunction, severe malnutrition); previous gastrointestinal surgery (including gastrectomy, fundoplication, and colostomy); current use of metformin, Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists, or other glucose-lowering agents with known gastrointestinal side effects; severe diabetic complications, cardiocerebrovascular diseases, or hepatic/renal/hematopoietic system disorders; alcohol abuse, defined as > 5 drinking occasions/week with consumption exceeding 100 g of distilled spirits, 250 g of rice wine, or five bottles ( ≥ 2500 mL) of beer; pregnancy or lactation; physical disability, cognitive impairment, or communication barriers affecting study compliance; and inability to commit to the study schedule.

The diagnostic criteria for DGAN were as follows: Meeting the 1999 World Health Organization diagnostic criteria for T2DM; compliance with either the 2022 American College of Gastroenterology Clinical Guideline: Gastroparesis or the 2021 Chinese Medical Association Expert Consensus on Diagnosis and Treatment of Diabetic Neuropathy; and the presence of ≥ 1 gastrointestinal symptom (dysphagia, regurgitation, nausea/vomiting, early satiety, bloating, diarrhea, constipation, or fecal incontinence), > 60% gastric retention at 2 h or > 10% gastric retention at 4 h post-ingestion of standardized solid-phase test meal, and exclusion of medication-induced or organic causes of gastrointestinal symptoms. Although patients were diagnosed based on gastroparesis criteria, they exhibited a spectrum of gastrointestinal symptoms, reflecting the pan-enteric nature of DGAN.

Height, weight, supine right upper arm blood pressure, and body mass index (BMI, kg/m2) were recorded for all patient groups. Additionally, the Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale (GSRS) questionnaire[23] was administered to patients with DGAN.

Blood samples were collected from the patients upon admission after an overnight fast (≥ 8 h). Biochemical parameters, including fasting blood glucose, fasting C-peptide (FC-P), 2-h postprandial C-peptide (2hC-P), and HbA1c levels, were measured. The duration of diabetes was defined as the interval between the initial diagnosis of diabetes and current hospital admission.

Upon admission fasting conditions were maintained, and 4 mL of venous blood were collected using vacuum blood collection tubes containing coagulation enhancers. Within 2 h the blood samples were centrifuged at 16000 × g for 10 min to separate the serum, which was then stored at -80 °C until further analysis. Thawed serum samples were analyzed by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry using a Jasper HPLC-Triple Quad 4500MD system (AB SCIEX, Framingham, MA, United States). The analysis included the measurement of six primary Bas [cholic acid, chenodeoxycholic acid, glycocholic acid (GCA), glycochenodeoxycholic acid, taurocholic acid (TCA), and taurochenodeoxycholic acid (TCDCA)] and nine serum BAs [deoxycholic acid (DCA), lithocholic acid, ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA), glycodeoxycholic acid (GDCA), glycolithocholic acid (GLCA), glycoursodeoxycholic acid (GUDCA), taurodeoxycholic acid (TDCA), taurolithocholic acid (TLCA), and tauroursodeoxycholic acid (TUDCA)].

Data are presented as the median (interquartile range). Statistical analysis among the three groups was performed using the unpaired Wilcoxon rank sum test. The ability of different BAs to discriminate between patients with uncomplicated T2DM and those with DGAN was assessed using fold change (FC) with FC ≥ |2|[24] used as the biomarker screening criterion. Orthogonal partial least squares discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA) was performed to determine the classification differences between patients with uncomplicated T2DM and those with DGAN. The discriminatory ability of different BAs was ranked using variable importance in projection (VIP) with VIP ≥ 1[25] used as the biomarker screening criterion. Spearman’s correlation analysis was performed to explore the correlations among clinical indicators, GSRS scores, and BAs. Stepwise simple and multiple regression analyses were performed to optimize diagnostic indicators. Receiver operating characteristic curve analysis was used to evaluate the performance of the diagnostic model by calculating the area under the curve (AUC). Statistical significance was denoted by P < 0.05 (two-tailed). All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 25.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, United States), GraphPad Prism 9.5 software (GraphPad, Boston, MA, United States), and SIMCA 14.1 (Sartorius, Göttingen, Germany).

Participants with uncomplicated T2DM and those with DGAN exhibited higher systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, and fasting blood glucose levels than the HCs (Table 1 and Figure 1) in addition to lower high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels. Furthermore, hemoglobin and aspartate aminotransferase levels were lower in the DGAN group than in the HC and T2DM groups. Compared with the findings in the T2DM group, the DGAN group had a younger age, lower BMI, HbA1c, FC-P, 2hC-P, and triglyceride (TG) levels, and a higher urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio (UACR). However, the duration of diabetes did not differ significantly between the DGAN and T2DM groups. Regarding patients’ histories, individuals with DGAN often had associated autonomic and peripheral neuropathies. Many patients presented with ketoacidosis at the time of T2DM diagnosis. Insulin was commonly used as a primary hypoglycemic therapy. However, insulin did not have a clear effect on gastrointestinal motility.

| Variables | HC (n = 75) | T2DM (n = 69) | DGAN (n = 26) | P value | P1 value | P2 value | P3 value |

| Gender (F, %) | 45, 52.30 | 28, 32.20 | 9, 34.60 | 0.951 | 1.000 | 0.810 | 0.813 |

| Age (years) | 56.00 (48.50, 65.00) | 58.00 (52.00, 64.00) | 46.00 (33.00, 63.00) | 0.060 | 0.467 | 0.053 | 0.024a |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 22.03 (20.67, 23.28) | 25.73 (24.11, 25.73) | 23.45 (20.62, 26.54) | < 0.001b | < 0.001b | 0.067 | 0.050a |

| Duration of diabetes, in months | - | 97.65 (24.00, 97.65) | 102.00 (36.00, 192.00) | 0.490 | - | - | 0.490 |

| Duration of GI, in months | - | - | 1.50 (0.29, 15.00) | - | - | - | - |

| SBP, mmHg | 119.00 (108.00, 127.00) | 130.00 (125.00, 143.00) | 127.50 (110.00, 150.00) | < 0.001b | < 0.001b | 0.003b | 0.424 |

| DBP, mmHg | 74.00 (67.50, 82.00) | 82.00 (78.00, 88.00) | 86.50 (76.00, 98.00) | < 0.001b | < 0.001b | < 0.001b | 0.224 |

| WBC, × 109/L | 6.19 (5.11, 7.56) | 6.81 (5.93, 7.44) | 5.96 (4.77, 7.30) | 0.113 | 0.088 | 0.484 | 0.096 |

| Hb, g/L | 134.00 (124.00, 147.00) | 137.03 (126.00, 147.00) | 129.00 (112.00, 137.00) | 0.014a | 0.236 | 0.042a | 0.003b |

| PLT, × 109/L | 224.00 (165.50, 257.50) | 219.70 (201.00, 229.00) | 211.50 (171.00, 262.00) | 0.994 | 0.944 | 0.825 | 0.968 |

| CRP, mg/L | 0.00 (0.00, 1.28) | 1.00 (0.00, 2.04) | 2.10 (1.00, 3.60) | 0.024a | 0.007b | 0.746 | 0.109 |

| FBG, mmol/L | 5.24 (4.90. 5.54) | 8.49 (6.00, 10.00) | 6.50 (5.00, 9.00) | < 0.001b | < 0.001b | 0.001b | 0.104 |

| HbA1c, % | - | 8.93 (7.40, 10.00) | 7.93 (6.60, 10.40) | < 0.001b | - | - | < 0.001b |

| FC-P, nmol/L | - | 0.81 (0.55, 0.83) | 0.45 (0.25, 0.65) | < 0.001b | - | - | < 0.001b |

| 2hC-P, nmol/L | - | 1.84 (1.15, 1.84) | 0.73 (0.34, 1.17) | < 0.001b | - | - | < 0.001b |

| BUN, mmol/L | 5.28 (4.32, 6.34) | 5.59 (4.60, 6.45) | 4.81 (4.28, 6.02) | 0.296 | 0.297 | 0.435 | 0.149 |

| SCr, µmol/L | 66.10 (52.95, 76.40) | 68.90 (58.90, 76.10) | 68.45 (49.70, 76.10) | 0.528 | 0.253 | 0.989 | 0.571 |

| eGFR, mL/min/1.73 m2 | 100.10 (100.10, 100.89) | 94.83 (93.49, 103.37) | 102.36 (88.93, 119.02) | 0.011a | 0.005b | 0.360 | 0.052 |

| UACR, mg/g | - | 32.51 (7.61, 87.32) | 66.19 (11.53, 694.73) | 0.010a | - | - | 0.010a |

| TG, mmol/L | 1.48 (1.05, 1.52) | 2.08 (1.29, 2.51) | 1.39 (1.08, 2.08) | 0.001b | < 0.001b | 0.645 | 0.031a |

| TC, mmol/L | 4.36 (4.04, 4.40) | 4.25 (3.64, 4.97) | 4.11 (3.59, 4.64) | 0.657 | 0.614 | 0.361 | 0.650 |

| LDL-C, mmol/L | 2.62 (2.28, 2.70) | 2.88 (2.25, 3.32) | 2.64 (2.18, 3.37) | 0.018a | 0.002b | 0.528 | 0.439 |

| HDL-C, mmol/L | 1.34 (1.24, 1.34) | 1.11 (0.96, 1.20) | 1.12 (0.94, 1.22) | < 0.001b | < 0.001b | < 0.001b | 0.986 |

| ALB, g/L | 43.10 (39.85, 46.85) | 42.39 (39.90, 44.20) | 38.45 (36.30, 44.10) | 0.044a | 0.249 | 0.024a | 0.060 |

| ALT, U/L | 15.40 (10.00, 19.10) | 18.70 (12.50, 24.20) | 14.05 (10.00, 21.00) | 0.012a | 0.004b | 0.816 | 0.061 |

| AST, U/L | 17.60 (14.75, 21.95) | 19.20 (14.80, 23.05) | 14.35 (11.70, 20.10) | 0.027a | 0.264 | 0.027a | 0.009b |

| Smoking history | 17 (22.70) | 17 (24.60) | 4 (15.40) | 0.640 | 0.838 | 0.579 | 0.414 |

| Drinking history | 17 (22.70) | 17 (24.60) | 7 (26.90) | 0.914 | 0.838 | 0.791 | 1.000 |

| Diabetic family history | 3 (4.00) | 10 (14.50) | 2 (7.70) | 0.079 | 0.040a | 0.601 | 0.500 |

| Hypertension | 0 | 25 (36.20) | 13 (50.00) | < 0.001b | < 0.001b | < 0.001b | 0.247 |

| Cerebral infarction | 0 | 10 (14.50) | 3 (11.50) | 0.004b | < 0.001b | 0.016a | 0.750 |

| Coronary atherosclerotic heart disease | 0 | 7 (10.10) | 2 (7.70) | 0.018a | 0.005b | 0.064 | 1.000 |

| Diabetic ketosis | - | 1 (1.40) | 11 (42.30) | < 0.001b | - | - | < 0.001b |

| Diabetic nephropathy | - | 9 (13.00) | 5 (19.20) | 0.515 | - | - | 0.515 |

| Diabetic autonomic neuropathy | - | 0 (0.00) | 10 (38.50) | < 0.001b | - | - | < 0.001b |

| Diabetic peripheral neuropathy | - | 18 (26.10) | 16 (61.50) | 0.002b | - | - | 0.002b |

| Diabetic retinopathy | - | 3 (4.30) | 4 (15.40) | 0.086 | - | - | 0.086 |

| Sulfonylureas | - | 4 (5.80) | 2 (7.70) | 1.000 | - | - | 1.000 |

| Glinides | - | 3 (4.30) | 1 (3.80) | 1.000 | - | - | 1.000 |

| Metformin | - | 14 (20.30) | 9 (34.60) | 0.181 | - | - | 0.181 |

| TZDs | - | 0 (0.00) | 1 (3.80) | 0.275 | - | - | 0.275 |

| AGI | - | 2 (2.90) | 1 (3.80) | 1.000 | - | - | 1.000 |

| SGLT-2i | - | 9 (13.00) | 4 (15.40) | 1.000 | - | - | 1.000 |

| DPP-4i | - | 3 (4.30) | 2 (7.70) | 0.604 | - | - | 0.604 |

| Insulin | - | 10 (14.50) | 17 (65.40) | < 0.001b | - | - | < 0.001b |

| GLP-1Ra | - | 6 (8.70) | 2 (7.70) | 1.000 | - | - | 1.000 |

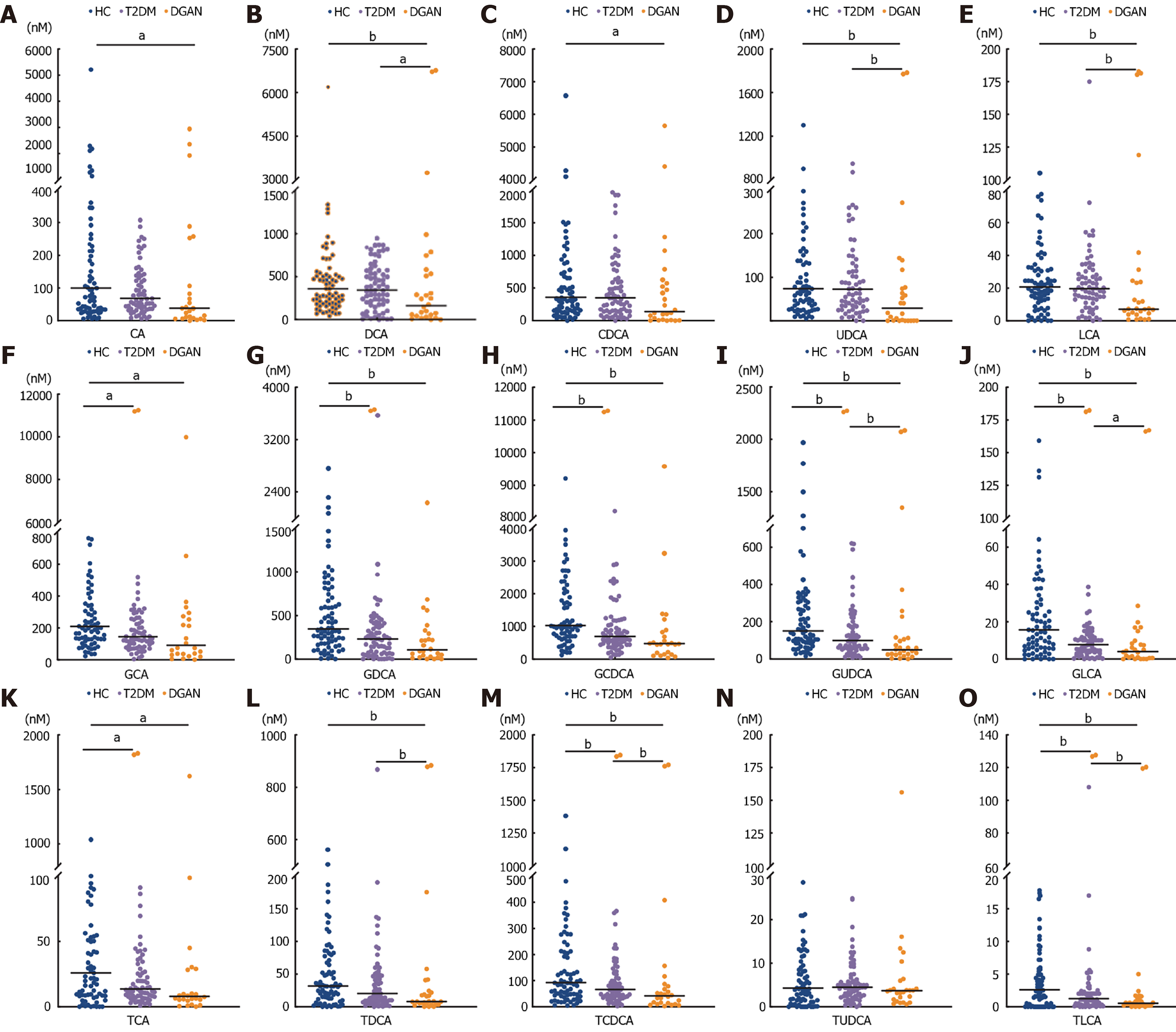

We quantified 15 different BAs in the HC, T2DM, and DGAN groups (Table 1 and Figure 2). Compared with the findings in the HC group, the levels of eight of ten conjugated BAs (GCA, GLCA, GDCA, glycochenodeoxycholic acid, GUDCA, TCA, TLCA, and TCDCA) were lower in both the T2DM and DGAN groups. Furthermore, DCA, UDCA, lithocholic acid, GUDCA, GLCA, TCA, TCDCA, TDCA, and TLCA levels were lower in the T2DM group than in the HC group, whereas the levels of these BAs were lower in the DGAN group than in the T2DM group. Further analysis revealed that the levels of GUDCA, GLCA, TCDCA, and TLCA sequentially decreased in the HC, T2DM, and DGAN groups (all P < 0.05).

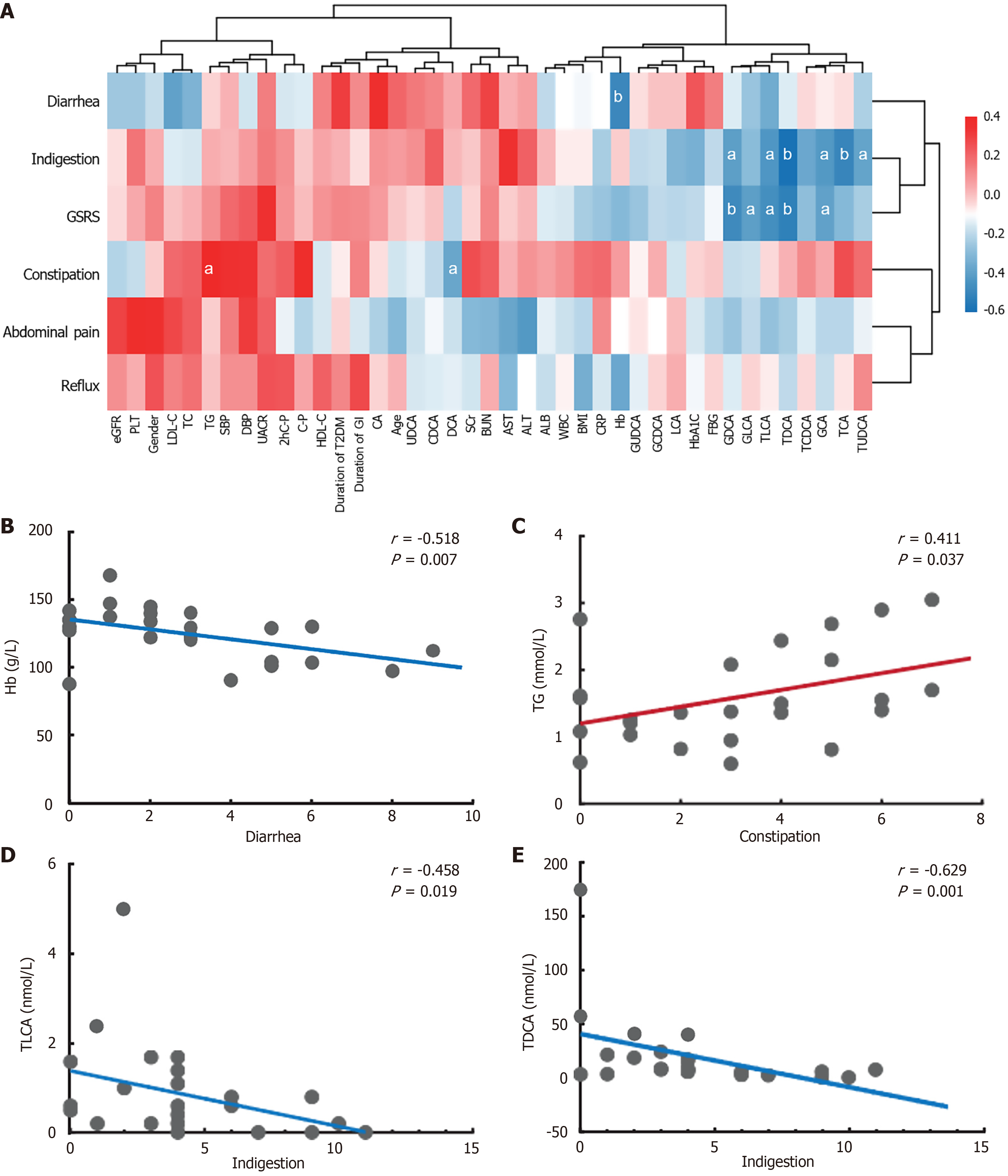

Regarding the correlations among clinical indicators, BA levels, and GSRS scores in the T2DM and DGAN groups (Figure 3A), we observed predominantly negative correlations between clinical indicators and GSRS scores. Specifically, constipation exhibited a significant positive correlation with TG levels (r = 0.411, P < 0.05; Figure 3B). By contrast diarrhea was negatively correlated with hemoglobin levels (r = -0.518, P < 0.01; Figure 3C). Spearman’s correlation analysis between BA levels and GSRS scores highlighted a strong negative correlation between DCA levels and constipation (r =

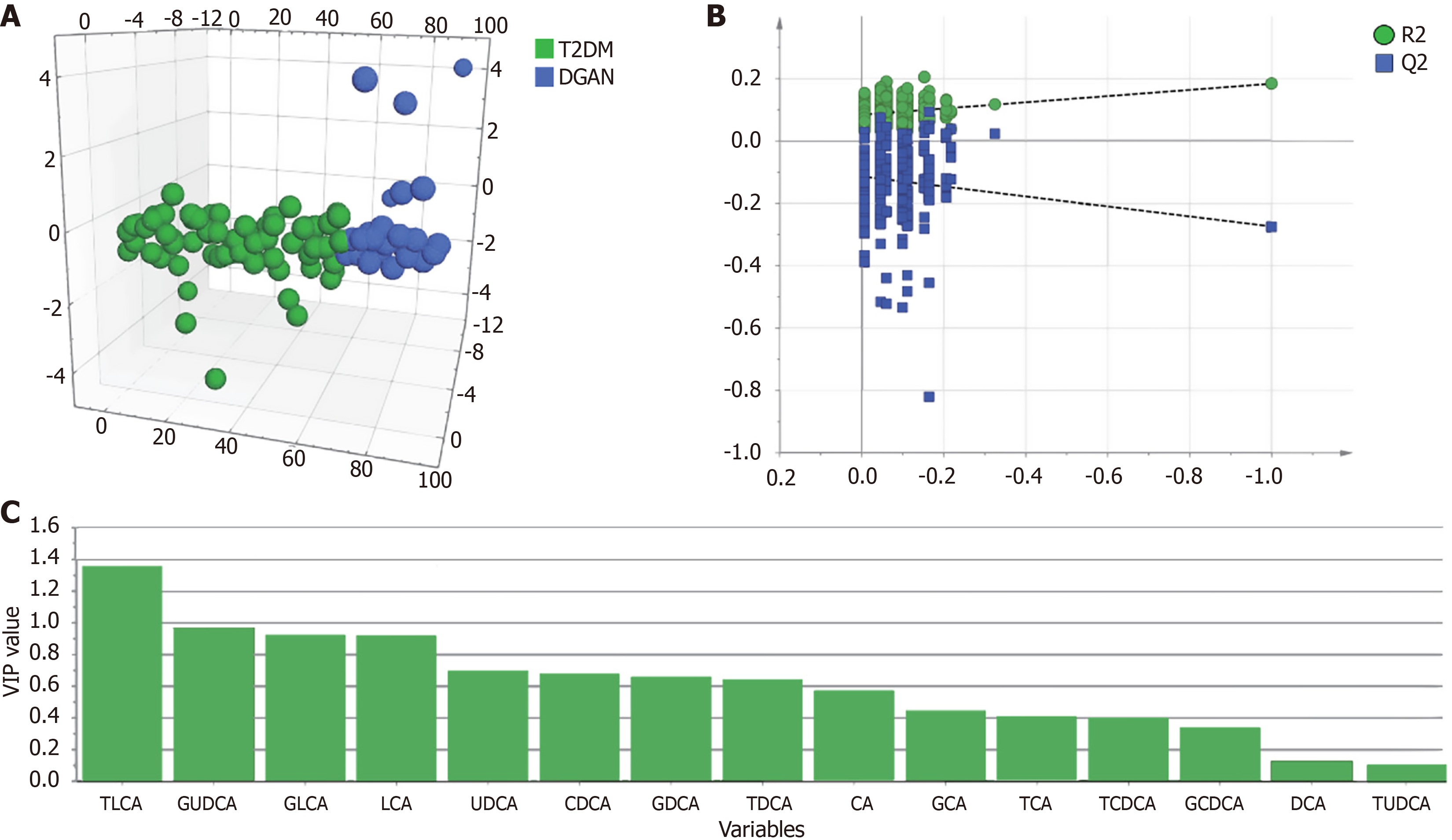

To identify biomarkers that differentiate patients with uncomplicated T2DM from those with DGAN, we employed OPLS-DA using a comprehensive panel of 15 BAs. Using SIMCA 14.1, we normalized the data to ensure comparability. The OPLS-DA model as hypothesis-generating effectively delineated patients with uncomplicated T2DM from those with DGAN (Figure 4). The negative Q2 value indicated that the OPLS-DA model lacked independent predictive value; it was used primarily for variable selection (identifying TLCA) rather than for classification. We evaluated the significance of these metabolites in the differentiated groups based on VIP scores and FC (Table 2 and Figure 4C). TLCA had VIP scores exceeding 1, highlighting its potential as a discriminative biomarker. Additionally, FC was lower than 0.5 for TLCA. We then selected clinical indicators and BAs that exhibited statistical significance (P < 0.05, univariate analysis), VIP > 1, and FC < 0.5 between the T2DM and DGAN groups. Only meaningful data are presented in Table 2. These metabolites were deemed differential and subsequently used for logistic regression analysis.

To refine the variable selection process and mitigate the risk of overfitting, we performed penalized regression [least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO)] regression analysis on the 22 clinical variables. The optimal penalty parameter (λ) was determined via ten-fold cross-validation, which identified 12 variables with non-zero coefficients for inclusion in the subsequent regression models (Supplementary Figure 1). Multivariable logistic regression models were constructed using the 12 variables selected by LASSO regression (Supplementary Table 1). Model 1 included age, BMI, hemoglobin, FC-P, 2hC-P, UACR, albumin, and conjugated BAs (CA, GLCA, TCA, TDCA, TUDCA). Model 2 included all model 1 variables plus TLCA. The odds ratios (ORs) and P values for all variables were highly consistent between the two models, demonstrating remarkable robustness. Several variables, including BMI (model 1, P = 0.078; model 2, P = 0.069), CA (model 1, P = 0.060; model 2, P = 0.058), and 2hC-P (model 1, P = 0.111; model 2, P = 0.094), exhibited near-significant associations, identifying them as potential predictors worthy of further investigation. Although the incorporation of TLCA in model 2 (OR = 1.241, P = 0.553) did not achieve statistical significance, its successful estimation provides a reliable basis and a novel direction for future investigations.

We further evaluated the potential confounding effects of key glucose-lowering medications (insulin and metformin) (Supplementary Table 2). When these medications were included as covariates in the multivariable logistic regression model, insulin use emerged as the strongest independent risk factor for DGAN (OR = 54.73, P = 0.001) while the associations of TLCA and FC-P were no longer statistically significant (both P > 0.5). To address potential confounding effects of glucose-lowering medications, we performed a correlation analysis including the medication status and its interaction with TLCA levels. As presented in Supplementary Table 3, both insulin use (F = 7.777, P = 0.008) and TLCA levels (F = 3.135, P < 0.001) remained significantly associated with the group classification (DGAN vs T2DM) after adjusting for these factors. Notably, metformin use (P = 0.003) and insulin use (P = 0.01) were significantly associated with TLCA levels, suggesting that the relationship between TLCA and DGAN risk can be modulated by medication use.

This result strongly suggested that disease severity and treatment stage were the primary drivers of DGAN risk. Given that insulin use is highly correlated with β cell failure (reflected by low FC-P levels) and overall metabolic dysregulation, we posited that alterations in TLCA levels may be intrinsically linked to this severe disease phenotype rather than acting as an independent causal factor. As the primary aim of this study was to explore the association between BA metabolism and DGAN and considering that including highly collinear clinical treatment variables alongside pathophysiological biomarkers may introduce a risk of overadjustment, we retained the biologically plausible variables (age, FC-P, TLCA) identified in our initial analyses for the subsequent construction of the predictive model.

Univariate regression analysis (Table 3) identified age, BMI, hemoglobin, FC-P, 2hC-P, albumin, and TLCA as protective factors against DGAN, whereas UACR emerged as a risk factor. In the multivariate logistic regression analysis (Table 4), we adjusted for numerous confounding factors (P < 0.05, univariate analysis) in model 1. Age exhibited an independent protective effect against the development of DGAN. Interestingly, FC-P and UACR lost their roles as protective and risk factors. In model 2 the protective factors included FC-P and TLCA in addition to age. Based on VIP scores, univariate analysis results, and logistic regression findings, TLCA was identified as a significant biomarker.

| Variables | Univariate logistic regression analysis | |

| OR (95%CI) | P value | |

| Clinical indicators | ||

| Gender, F, % | 1.131 (0.436-2.935) | 0.800 |

| Age, years | 0.941 (0.904-0.978) | 0.002b |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 0.759 (0.635-0.907) | 0.002b |

| Duration of diabetes, months | 1.002 (0.997-1.008) | 0.388 |

| SBP, mmHg | 0.999 (0.973-1.025) | 0.929 |

| DBP, mmHg | 1.029 (0.988-1.071) | 0.172 |

| WBC, × 109/L | 0.855 (0.650-1.123) | 0.260 |

| Hb, g/L | 0.962 (0.936-0.989) | 0.006b |

| PLT, × 109/L | 1.000 (0.992-1.008) | 0.995 |

| CRP, mg/L | 1.068 (0.987-1.157) | 0.103 |

| FBG, mmol/L | 0.874 (0.732-1.044) | 0.137 |

| HbA1c, % | 0.895 (0.720-1.113) | 0.320 |

| FC-P, nmol/L | 0.062 (0.011-0.339) | 0.001b |

| 2hC-P, nmol/L | 0.185 (0.078-0.438) | < 0.001b |

| BUN, mmol/L | 0.873 (0.683-1.117) | 0.281 |

| SCr, µmol/L | 1.004 (0.991-1.017) | 0.555 |

| eGFR, mL/min/1.73 m2 | 1.013 (0.990-1.036) | 0.264 |

| UACR, mg/g | 1.001 (1.000-1.003) | 0.037a |

| TG, mmol/L | 0.551 (0.327-1.929) | 0.065 |

| TC, mmol/L | 0.985 (0.677-1.433) | 0.937 |

| LDL-C, mmol/L | 0.864 (0.540-1.382) | 0.542 |

| HDL-C, mmol/L | 0.393 (0.052-2.972) | 0.365 |

| ALB, g/L | 0.895 (0.808-0.992) | 0.034a |

| ALT, U/L | 0.960 (0.916-1.006) | 0.088 |

| AST, U/L | 0.948 (0.887-1.012) | 0.111 |

| BAs characteristics | ||

| CA, nmol/L | 1.001 (1.000-1.002) | 0.070 |

| DCA, nmol/L | 1.000 (0.999-1.001) | 0.813 |

| CDCA, nmol/L | 1.000 (1.000-1.001) | 0.386 |

| UDCA, nmol/L | 0.997 (0.993-1.001) | 0.169 |

| LCA, nmol/L | 0.996 (0.979-1.014) | 0.673 |

| GCA, nmol/L | 1.000 (1.000-1.001) | 0.276 |

| GLCA, nmol/L | 0.948 (0.886-1.014) | 0.120 |

| GDCA, nmol/L | 1.000 (0.999-1.001) | 0.663 |

| GCDCA, nmol/L | 1.000 (1.000-1.000) | 0.832 |

| GUDCA, nmol/L | 0.999 (0.996-1.002) | 0.561 |

| TCA, nmol/L | 1.003 (0.998-1.007) | 0.226 |

| TLCA, nmol/L | 0.603 (0.377-0.964) | 0.035a |

| TDCA, nmol/L | 0.985 (0.968-1.003) | 0.106 |

| TCDCA, nmol/L | 1.001 (0.999-1.003) | 0.201 |

| TUDCA, nmol/L | 1.014 (0.986-1.043) | 0.333 |

| Variables | Multivariate logistic regression analysis | |||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |||

| OR (95%CI) | P value | OR (95%CI) | P value | |

| Age, years | 0.919 (0.851-0.993) | 0.033a | 0.882 (0.779-0.998) | 0.047a |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 0.961 (0.737-1.252) | 0.768 | 1.127 (0.813-1.562) | 0.471 |

| Hb, g/L | 0.987 (0.935-1.042) | 0.642 | 0.955 (0.884-1.032) | 0.243 |

| FC-P, nmol/L | 0.060 (0.001-2.406) | 0.135 | 0.000 (0.000-0.253) | 0.017a |

| 2hC-P, nmol/L | 0.348 (0.063-1.936) | 0.228 | 0.660 (0.107-4.072) | 0.654 |

| UACR, mg/g | 1.002 (0.998-1.006) | 0.302 | 1.003 (0.997-1.008) | 0.330 |

| ALB, g/L | 0.859 (0.694-1.063) | 0.163 | 0.824 (0.601-1.130) | 0.231 |

| TLCA, nmol/L | / | / | 0.160 (0.040-0.631) | 0.009b |

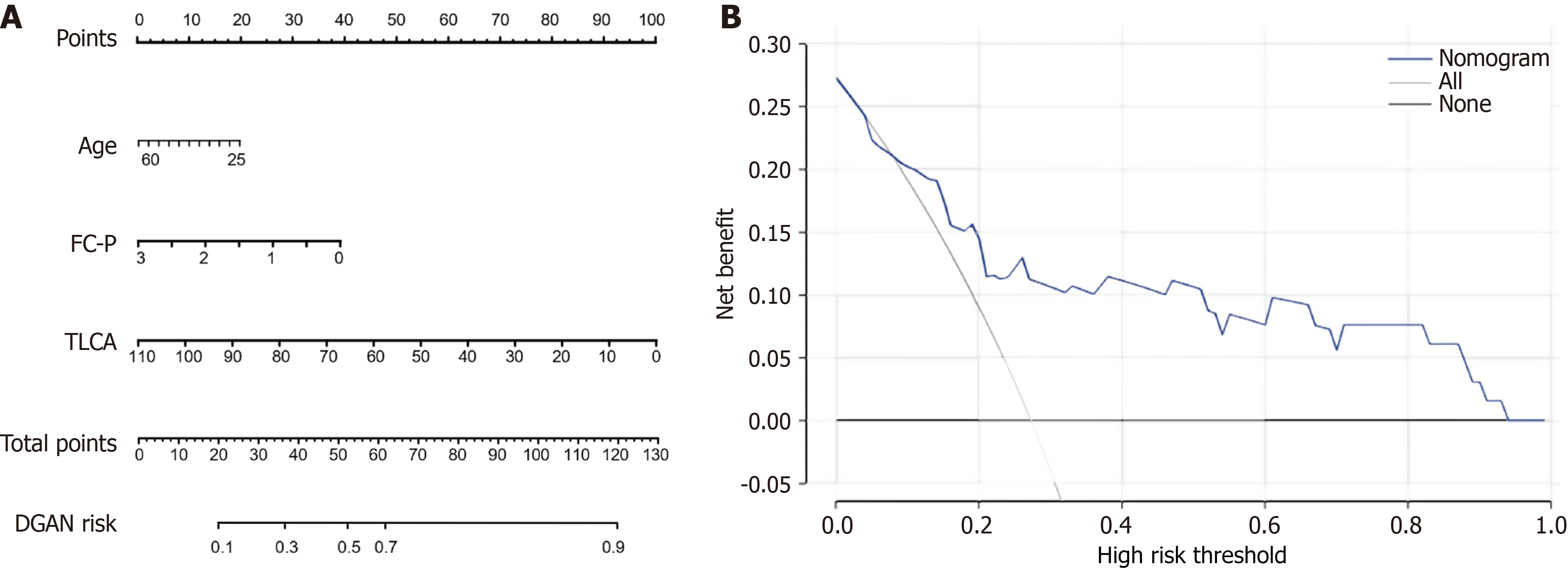

The results of the receiver operating characteristic analysis of the DGAN risk-prediction model are presented in Table 5. The AUCs for age, FC-P, and TLCA in discriminating between T2DM and DGAN were 0.651, 0.760, and 0.678 (P < 0.05), respectively. The AUC of model 2 for distinguishing T2DM and DGAN was 0.970 (95% confidence interval: 0.937-1.000), indicating greater predictive ability than the individual differentiating parameters and model 1 (AUC = 0.933, 95% confidence interval: 0.878-0.989). Moreover, these independent variables were combined to create a predictive model for identifying DGAN in patients with T2DM (Figure 5A). The clinical validity of this predictive model was assessed using decision curve analysis (Figure 5B), indicating that when the threshold probabilities ranged from 9.0% to 68.0%, a higher net clinical benefit was achieved compared with those of hypothetical testing scenarios. The Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test for the nomogram model (Supplementary Table 4) indicated good calibration: P = 0.096. The Integrated Discrimination Improvement for adding TLCA to the clinical model was 5.1% (P < 0.01), indicating an improvement in predictive performance. Thus, the inclusion of TLCA significantly enhanced the clinical diagnosis of DGAN.

| Variables | AUC (95%CI) | P value | Cutoff value | Sensitivity | Specificity |

| Age, years | 0.651 (0.504-0.797) | 0.024a | 0.450 | 0.462 | 0.942 |

| FC-P, nmol/L | 0.760 (0.648-0.872) | < 0.001b | 0.188 | 0.885 | 0.638 |

| TLCA, nmol/L | 0.678 (0.565-0.791) | < 0.001b | 0.219 | 0.923 | 0.435 |

| Model 1 | 0.933 (0.878-0.989) | < 0.001b | 0.277 | 0.885 | 0.884 |

| Model 2 | 0.970 (0.937-1.000) | < 0.001b | 0.392 | 0.923 | 0.957 |

This study provided an integrated clinical-metabolic portrait of DGAN. Three observations warrant further emphasis. First, broad suppression of conjugated BA levels was observed in diabetes with this suppression deepening in DGAN. Four species, namely GUDCA, GLCA, TCDCA, and most strikingly TLCA, declined stepwise from HC to uncomplicated T2DM to DGAN. Second, TLCA emerged as an independent protective factor, and its depletion was correlated with higher GSRS scores. The inclusion of TLCA in the multivariable model increased the AUC to 0.97, and its superior clinical net benefit was verified by decision curve analysis. Lastly, several readily available clinical variables distinguished DGAN from T2DM and yielded additional pathophysiological clues.

We observed that patients with T2DM with DGAN were predominantly younger individuals who were insulin-dependent. Moreover, these patients often presented with diabetic ketoacidosis as an initial manifestation of T2DM. This indicated severely impaired pancreatic function. Their younger age, combined with their busy and irregular lifestyles, likely influenced the neglect of their health. This prevented the timely detection of glycemic fluctuations and associated physical changes. Consequently, they often sought medical attention only when symptoms became severe. At this stage prolonged poor glycemic control might have caused hyperglycemia-induced toxicity, leading to gastrointestinal autonomic neuropathy.

Although these patients are relatively young, they exhibit various neurological complications, such as chest tightness, resting palpitations, urinary retention, peripheral numbness, and tingling. This underscores the importance of early glycemic management in preventing diabetes-related complications. Furthermore, HbA1c ≥ 7.0% increases the risk of gastric motility disorders, such as gastroparesis[26]. Counterintuitively, although HbA1c ≥ 7.0% increases gastroparesis risk[16], patients with DGAN had significantly lower HbA1c and C-peptide levels than those with uncomplicated T2DM.

This finding was not associated with DGAN development in univariate analysis, but it can be explained by two non-exclusive mechanisms: A rapidly-progressive phenotype characterized by premature β cell failure, which leads to a catabolic state with significant weight loss prior to glycemic stabilization; and chronic gastrointestinal symptoms, such as reduced appetite, vomiting, and food aversion, causing malnutrition and consequently lower BMI and HbA1c levels. This finding is consistent with that of Yuan et al[27] with corroborating biochemical evidence illustrating that reductions in hemoglobin levels correlating with diarrhea severity (suggesting malabsorption) and a negative constipation-TG association reflecting impaired chylomicron absorption during slowed intestinal transit.

Traditionally, the gold standards for diagnosing DGAN are gastric emptying scintigraphy and the gastric emptying breath test[2,28,29]. However, the administration of specific test meals can exacerbate symptoms in patients with frequent vomiting and severe constipation. Therefore, beyond early clinical identification based on symptoms, potential biomarkers must be explored. Our findings provide novel diagnostic and therapeutic insights. BAs are signaling molecules that influence multiple systems and play a crucial role in gastrointestinal diseases, such as digestive tract tumors, BA diarrhea, and bile reflux[7,27]. However, their relationship with DGAN remains underexplored.

In our study the comparison of serum BA profiles among HCs, patients with T2DM, and patients with DGAN revealed the protective role of TLCA in DGAN development. TLCA levels were negatively correlated with dyspeptic symptoms in patients with DGAN. The inclusion of TLCA improved the diagnostic sensitivity and specificity of the regression model, suggesting its potential as a biomarker for DGAN. TLCA was initially identified in bovine bile and gallstones, and it is a secondary BA derived from the primary BA UDCA. TLCA has also been detected in human bile[30]. As a high-affinity ligand for akeda G-protein-coupled receptor 5 (TGR5)[29,31], TLCA promotes GLP-1 secretion through the TGR5-cAMP-Ca2+ pathway in L cells of the mouse intestine[22], resulting in improved glucose metabolism[32,33]. Simultaneously, TLCA levels were lower in patients with diabetes than in HCs[34] as also reflected in our study.

Beyond its role in stimulating gut hormone secretion, TLCA level activation exerts anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective effects. More than 50% of intestinal neurons in the mouse enteric nervous system express TGR5[35]. BAs can act on TGR5 in the intestine to promote defecation in mice[36]. In murine models TGR5 signaling attenuates 5-hydroxytryptamine and nitric oxide release from macrophages, reduces endothelial adhesion molecule expression, and modulates neural inflammation[31]. These actions are particularly relevant in the context of diabetic neuropathy in which chronic low-grade inflammation and oxidative stress contribute to neuronal damage. Moreover, TGR5 is expressed in human enteric neurons and enterochromaffin cells, suggesting a direct pathway through which BAs can influence gut motility and sensory function[36]. This association might be linked to the downstream pathways of gastrointestinal receptors; however, the underlying mechanisms require further validation through animal experiments[22,31-33].

An apparent discrepancy exists between circulating TLCA levels in humans (in the nanomolar range) and the micromolar concentrations typically required to activate TGR5 in vitro, raising questions about its mechanistic relevance in vivo. This paradox can likely be explained by the localized nature of BA signaling. BAs primarily act in specific anatomical compartments, such as the intestinal lumen, biliary tree, and portal venous system, in which their concentrations can reach millimolar levels, far exceeding those in serum and becoming sufficient to robustly activate TGR5[37,38]. The high first-pass clearance (70%-90%) by the liver ensures that systemic BA concentrations reflect downstream “spillover” rather than local activity[37]. Thus, measuring peripheral blood TCLA levels might underestimate its local bioactivity at target sites. Serum TLCA levels likely serve as a surrogate marker reflecting systemic disruption of enterohepatic circulation, rather than directly representing bioactive concentrations at neuronal TGR5 sites.

The strategic distribution of TGR5 in the human digestive tract supports its functional importance. TGR5 is expressed in regions with the highest BA concentration (ileum) or greatest bioactive potential (colon), positioning it as a key sensor for BA signals that regulate metabolism, immunity, and motility[39]. Although its expression pattern in the enteric nervous system might differ from that in mice[35], the functional activity of TGR5 in human gastrointestinal epithelial and immune cells is well established. For instance, TGR5 expression progressively increases during the progression from precancerous lesions to invasive carcinoma in the biliary epithelium[40], and its expression is elevated in gastric cancer in which it promotes metaplasia[41]. These findings unequivocally demonstrate an active TGR5 pathway in human gastrointestinal tissues.

Moreover, direct evidence from human diseases supports the relevance of the TLCA-TGR5 axis. Patients with T2DM exhibit significantly lower serum TLCA levels than HCs[34] and reduced expression of key BA transporters in the gastrointestinal tract[42], consistent with our observation and inversely corroborating our findings in mice.

An important finding of this study is the widespread suppression of conjugated BAs, a pattern highly consistent with ileal dysfunction. DGAN likely impairs ileal reabsorption of BAs via the apical sodium-dependent BA transporter transporter, leading to increased fecal loss and a reduced circulating pool. This is supported by the established link between diabetic and abnormal BA metabolism[43]. Furthermore, intestinal inflammation and barrier defects (common in DGAN) can directly disrupt apical sodium-dependent BA transporter function, promoting colonic BA accumulation and diarrhea[44].

However, the interpretation of our findings must be considered in the context of glucose-lowering medications. A sensitivity analysis adjusting for insulin and metformin use indicated that the association of TLCA and FC-P with DGAN was attenuated while insulin use itself emerged as a powerful predictor (Supplementary Table 3). This result strongly suggests that disease severity and treatment stage are the primary drivers of DGAN risk. We interpret this finding from the following perspective: The serum BA profile, particularly TLCA, may serve as a sensitive biomarker for this rapidly progressive, insulin-dependent, high DGAN-risk diabetic phenotype. In other words, BA metabolic dysregulation may be an intrinsic component of this high-risk phenotype rather than a treatment-independent predictor.

Including therapeutic variables alongside fundamental metabolic biomarkers in the same model may pose a risk of overadjustment as the treatment itself is predicated on the severity of the disease, a state that is likely mediated at least in part by mechanisms such as BA metabolic disruption. Consequently, we propose that for risk stratification models aimed at early identification, utilizing BA biomarkers that reflect underlying physiological states hold greater prospective value and biological relevance than relying on treatment decisions (such as insulin use). Future prospective studies involving repeated measurements of the BA profile prior to the initiation of insulin therapy in patients are warranted to clarify the causal relationship with DGAN risk.

The strengths of this study included the simultaneous assessment of detailed BA spectra, validated symptom scoring, and rigorous multivariate modeling. However, this study had some limitations. These include its cross-sectional design, modest overall sample size, and notably the particularly small sample size of the DGAN group (n = 26) that inherently limited the robustness and generalizability of our predictive model despite the use of LASSO regression. Consequently, this work is exploratory, and the observed discriminatory performance (AUC = 0.970) must be viewed as preliminary. Recruitment from a single center and the lack of direct measurements of the gastrointestinal microbiota or fecal BA output are additional constraints. Therefore, causality remains inferential, and external validation in larger, multicenter cohorts is required before any routine clinical recommendation can be offered; we have planned subsequent studies for this purpose.

Longitudinal cohorts should determine whether declining TLCA precedes symptom onset and predicts responses to BA-centered therapies. Although we adjusted for the use of key anti-diabetic medications (such as metformin and insulin), we did not comprehensively collect information on the use of other glucose-lowering or lipid-lowering drugs. Additionally, although the exclusion of metformin and GLP-1 receptor agonists was methodologically necessary to limit confounding effects on gastrointestinal function and BA metabolism, this might have reduced the generalizability of our findings as these drugs are first-line therapies for T2DM. Furthermore, important confounding factors that can influence BA profiles and disease risk, such as dietary patterns, physical activity, and the specific duration and severity of diabetes, were not included in our analysis. These unmeasured residual confounding factors might have influenced our results. DGAN involves pan-enteric dysfunction, and our gastroparesis-focused diagnostic criterion represents a limitation as the study cohort may not fully reflect colonic or intestinal dysmotility underlying symptoms such as diarrhea or constipation. Future studies with more detailed prospective data collection are warranted to further validate our findings.

A simple risk assessment model based on five clinical indicators and serum BAs could reliably predict DGAN risk in patients with T2DM. Timely and effective interventions could prevent gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with T2DM. This predictive model could assist clinicians in assessing the risk in patients with T2DM. Furthermore, it could be used to design future clinical trials aimed at preventing DGAN in individuals with T2DM.

The authors acknowledge resources and support from the Experimental Center of The Second Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University.

| 1. | Bharucha AE, Kudva YC, Prichard DO. Diabetic Gastroparesis. Endocr Rev. 2019;40:1318-1352. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 155] [Article Influence: 22.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 2. | Shen S, Xu J, Lamm V, Vachaparambil CT, Chen H, Cai Q. Diabetic Gastroparesis and Nondiabetic Gastroparesis. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2019;29:15-25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Sangnes DA, Dimcevski G, Frey J, Søfteland E. Diabetic diarrhoea: A study on gastrointestinal motility, pH levels and autonomic function. J Intern Med. 2021;290:1206-1218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Wei L, Ji L, Miao Y, Han X, Li Y, Wang Z, Fu J, Guo L, Su Y, Zhang Y. Constipation in DM are associated with both poor glycemic control and diabetic complications: Current status and future directions. Biomed Pharmacother. 2023;165:115202. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Concepción Zavaleta MJ, Gonzáles Yovera JG, Moreno Marreros DM, Rafael Robles LDP, Palomino Taype KR, Soto Gálvez KN, Arriola Torres LF, Coronado Arroyo JC, Concepción Urteaga LA. Diabetic gastroenteropathy: An underdiagnosed complication. World J Diabetes. 2021;12:794-809. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 6. | Feldman M, Schiller LR. Disorders of gastrointestinal motility associated with diabetes mellitus. Ann Intern Med. 1983;98:378-384. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 446] [Cited by in RCA: 409] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Camilleri M, Kuo B, Nguyen L, Vaughn VM, Petrey J, Greer K, Yadlapati R, Abell TL. ACG Clinical Guideline: Gastroparesis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2022;117:1197-1220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 227] [Cited by in RCA: 183] [Article Influence: 45.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Notghi A, James G, Hay PD. British Nuclear Medicine Society Clinical Guidelines for Gastric empty. Nucl Med Commun. 2023;44:563-570. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Solnes LB, Sheikhbahaei S, Ziessman HA. Nuclear Scintigraphy in Practice: Gastrointestinal Motility. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2018;211:260-266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Camilleri M, Iturrino J, Bharucha AE, Burton D, Shin A, Jeong ID, Zinsmeister AR. Performance characteristics of scintigraphic measurement of gastric emptying of solids in healthy participants. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2012;24:1076-e562. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 139] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Cao Q, Deng R, Pan Y, Liu R, Chen Y, Gong G, Zou J, Yang H, Han D. Robotic wireless capsule endoscopy: recent advances and upcoming technologies. Nat Commun. 2024;15:4597. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Tao J, Campbell JN, Tsai LT, Wu C, Liberles SD, Lowell BB. Highly selective brain-to-gut communication via genetically defined vagus neurons. Neuron. 2021;109:2106-2115.e4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 18.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kilpatrick ES, Rigby AS, Atkin SL. The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial: the gift that keeps giving. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2009;5:537-545. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Pop-Busui R. Autonomic diabetic neuropathies: A brief overview. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2023;206 Suppl 1:110762. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Aleppo G, Calhoun P, Foster NC, Maahs DM, Shah VN, Miller KM; T1D Exchange Clinic Network. Reported gastroparesis in adults with type 1 diabetes (T1D) from the T1D Exchange clinic registry. J Diabetes Complications. 2017;31:1669-1673. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 16. | Yuan HL, Zhang X, Chu WW, Lin GB, Xu CX. Risk factor analysis and nomogram for predicting gastroparesis in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Heliyon. 2024;10:e26221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Du Y, Neng Q, Li Y, Kang Y, Guo L, Huang X, Chen M, Yang F, Hong J, Zhou S, Zhao J, Yu F, Su H, Kong X. Gastrointestinal Autonomic Neuropathy Exacerbates Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis in Adult Patients With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2021;11:804733. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Schirmer M, Garner A, Vlamakis H, Xavier RJ. Microbial genes and pathways in inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2019;17:497-511. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 249] [Cited by in RCA: 670] [Article Influence: 111.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Camilleri M, Vijayvargiya P. The Role of Bile Acids in Chronic Diarrhea. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;115:1596-1603. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Chang C, Jiang J, Sun R, Wang S, Chen H. Downregulation of Serum and Distal Ileum Fibroblast Growth Factor19 in Bile Acid Diarrhoea Patients. Dig Dis Sci. 2022;67:872-879. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Katsuma S, Hirasawa A, Tsujimoto G. Bile acids promote glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion through TGR5 in a murine enteroendocrine cell line STC-1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;329:386-390. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 521] [Cited by in RCA: 604] [Article Influence: 28.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Brighton CA, Rievaj J, Kuhre RE, Glass LL, Schoonjans K, Holst JJ, Gribble FM, Reimann F. Bile Acids Trigger GLP-1 Release Predominantly by Accessing Basolaterally Located G Protein-Coupled Bile Acid Receptors. Endocrinology. 2015;156:3961-3970. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 210] [Cited by in RCA: 273] [Article Influence: 24.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Svedlund J, Sjödin I, Dotevall G. GSRS--a clinical rating scale for gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome and peptic ulcer disease. Dig Dis Sci. 1988;33:129-134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 884] [Cited by in RCA: 1084] [Article Influence: 28.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Zhang J, Huang X, Wang X, Gao Y, Liu L, Li Z, Chen X, Zeng J, Ye Z, Li G. Identification of potential crucial genes in atrial fibrillation: a bioinformatic analysis. BMC Med Genomics. 2020;13:104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Wiklund S, Johansson E, Sjöström L, Mellerowicz EJ, Edlund U, Shockcor JP, Gottfries J, Moritz T, Trygg J. Visualization of GC/TOF-MS-based metabolomics data for identification of biochemically interesting compounds using OPLS class models. Anal Chem. 2008;80:115-122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 906] [Cited by in RCA: 914] [Article Influence: 48.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Krishnasamy S, Abell TL. Diabetic Gastroparesis: Principles and Current Trends in Management. Diabetes Ther. 2018;9:1-42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 13.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Yuan HL, Zhang X, Peng DZ, Lin GB, Li HH, Li FX, Lu JJ, Chu WW. Development and Validation of a Risk Nomogram Model for Predicting Constipation in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2023;16:1109-1120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Muller PA, Koscsó B, Rajani GM, Stevanovic K, Berres ML, Hashimoto D, Mortha A, Leboeuf M, Li XM, Mucida D, Stanley ER, Dahan S, Margolis KG, Gershon MD, Merad M, Bogunovic M. Crosstalk between Muscularis Macrophages and Enteric Neurons Regulates Gastrointestinal Motility. Cell. 2014;158:1210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Kawamata Y, Fujii R, Hosoya M, Harada M, Yoshida H, Miwa M, Fukusumi S, Habata Y, Itoh T, Shintani Y, Hinuma S, Fujisawa Y, Fujino M. A G protein-coupled receptor responsive to bile acids. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:9435-9440. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1060] [Cited by in RCA: 1271] [Article Influence: 55.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Xie C, Huang W, Young RL, Jones KL, Horowitz M, Rayner CK, Wu T. Role of Bile Acids in the Regulation of Food Intake, and Their Dysregulation in Metabolic Disease. Nutrients. 2021;13:1104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 15.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Kida T, Tsubosaka Y, Hori M, Ozaki H, Murata T. Bile acid receptor TGR5 agonism induces NO production and reduces monocyte adhesion in vascular endothelial cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2013;33:1663-1669. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Parker HE, Wallis K, le Roux CW, Wong KY, Reimann F, Gribble FM. Molecular mechanisms underlying bile acid-stimulated glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion. Br J Pharmacol. 2012;165:414-423. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 187] [Cited by in RCA: 179] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Keitel V, Cupisti K, Ullmer C, Knoefel WT, Kubitz R, Häussinger D. The membrane-bound bile acid receptor TGR5 is localized in the epithelium of human gallbladders. Hepatology. 2009;50:861-870. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 200] [Cited by in RCA: 224] [Article Influence: 13.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Chen B, Bai Y, Tong F, Yan J, Zhang R, Zhong Y, Tan H, Ma X. Glycoursodeoxycholic acid regulates bile acids level and alters gut microbiota and glycolipid metabolism to attenuate diabetes. Gut Microbes. 2023;15:2192155. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Poole DP, Godfrey C, Cattaruzza F, Cottrell GS, Kirkland JG, Pelayo JC, Bunnett NW, Corvera CU. Expression and function of the bile acid receptor GpBAR1 (TGR5) in the murine enteric nervous system. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2010;22:814-825, e227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 175] [Cited by in RCA: 177] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Alemi F, Poole DP, Chiu J, Schoonjans K, Cattaruzza F, Grider JR, Bunnett NW, Corvera CU. The receptor TGR5 mediates the prokinetic actions of intestinal bile acids and is required for normal defecation in mice. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:145-154. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 232] [Cited by in RCA: 282] [Article Influence: 21.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Marin JJ, Macias RI, Briz O, Banales JM, Monte MJ. Bile Acids in Physiology, Pathology and Pharmacology. Curr Drug Metab. 2015;17:4-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 136] [Article Influence: 13.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Ticho AL, Malhotra P, Dudeja PK, Gill RK, Alrefai WA. Intestinal Absorption of Bile Acids in Health and Disease. Compr Physiol. 2019;10:21-56. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 159] [Article Influence: 22.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Perino A, Schoonjans K. TGR5 and Immunometabolism: Insights from Physiology and Pharmacology. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2015;36:847-857. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Kim H, Kim HJ, Park YT, Kim JS. Clinical Significance of Sphingosine 1-phosphate Receptor 2 and Takeda G Protein-coupled Receptor 5 in Extrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma Patients. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2023;32:371-376. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Carino A, Graziosi L, D'Amore C, Cipriani S, Marchianò S, Marino E, Zampella A, Rende M, Mosci P, Distrutti E, Donini A, Fiorucci S. The bile acid receptor GPBAR1 (TGR5) is expressed in human gastric cancers and promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition in gastric cancer cell lines. Oncotarget. 2016;7:61021-61035. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Nerild HH, Gilliam-Vigh H, Ellegaard AM, Forman JL, Vilsbøll T, Sonne DP, Brønden A, Knop FK. Expression of Bile Acid Receptors and Transporters Along the Intestine of Patients With Type 2 Diabetes and Controls. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2025;110:e660-e666. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Xiao L, Pan G. An important intestinal transporter that regulates the enterohepatic circulation of bile acids and cholesterol homeostasis: The apical sodium-dependent bile acid transporter (SLC10A2/ASBT). Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2017;41:509-515. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Lefebvre P, Cariou B, Lien F, Kuipers F, Staels B. Role of bile acids and bile acid receptors in metabolic regulation. Physiol Rev. 2009;89:147-191. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1046] [Cited by in RCA: 1269] [Article Influence: 74.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/