Published online Dec 15, 2025. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v16.i12.112830

Revised: October 11, 2025

Accepted: October 23, 2025

Published online: December 15, 2025

Processing time: 130 Days and 22.4 Hours

Cotadutide (MEDI0382) is a twincretin that acts as an agonist for both the glucagon-like peptide-1 and glucagon receptors. Several randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have been published evaluating the use of cotadutide in individuals with type 2 diabetes (T2D), showing promising results. However, the efficacy and safety of the drug use have been inadequately explored by systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

To assess the clinical efficacy and safety of cotadutide in individuals with T2D having overweight or obesity.

The systematic reviews and meta-analyses have been registered with International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (CRD42024511703), and the protocol summary can be accessed online. Several databases and registries, including MEDLINE (via PubMed), Scopus, Web of Science, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, and ClinicalTrials.gov, were systematically searched using related terms from their inception to May 15, 2025, for RCTs involving individuals with T2D receiving cotadutide in the intervention group. Review Manager web was used to conduct meta-analysis using random-effects models. The co-primary outcomes of interest were the changes in glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) and the percent changes in body weight from baseline. The results of the outcomes were expressed as mean differences (MDs) or risk ratios (RRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The analysis of outcomes was stratified according to whether the control group received a placebo, denoted as the placebo control group (PCG), or an active comparator, referred to as the active control group (ACG).

Nine RCTs (mostly phase 2 RCTs, n = 1525) with study durations varying from 28 days to 54 weeks that met all the inclusion criteria were analyzed; five studies had a low overall risk of bias, while the other four had some concerns. Compared to the PCG, greater reductions in HbA1c were achieved with cotadutide 100 μg (MD -0.77%, 95%CI:

Cotadutide demonstrated glycemic control and weight-loss benefits in short-term, small RCTs (mostly phase 2). However, small sample sizes, very low to low certainty of evidence, and the absence of data on long-term cardiovascular and renal outcomes highlight substantial uncertainties, warranting cautious interpretation and further investigation in larger, longer-term trials to establish its safety and efficacy profile.

Core Tip: Cotadutide, a dual glucagon-like peptide-1/glucagon receptor agonist, effectively lowers glycated hemoglobin and body weight in people with type 2 diabetes and overweight or obesity. A meta-analysis of nine randomized controlled trials reveals modest reductions in blood sugar and weight compared to the placebo, with efficacy similar to that of active comparators. Common side effects include gastrointestinal symptoms (nausea, vomiting, dyspepsia, constipation, decreased appetite) without an excess risk of serious adverse events. Continued use should weigh the benefits of glucose and weight control against the risk of gastrointestinal side effects. Cotadutide’s safety and long-term outcomes require further research; however, it shows promise as a potential therapeutic option for metabolic disorders.

- Citation: Kamrul-Hasan ABM, Dutta D, Nagendra L, Basavarajappa SD, Girijashankar HB, Joshi A, Pappachan JM. Glycemic control, weight-loss effects, and safety of cotadutide in individuals with type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Diabetes 2025; 16(12): 112830

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9358/full/v16/i12/112830.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4239/wjd.v16.i12.112830

Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists (RAs) have transformed the treatment landscape for type 2 diabetes (T2D) and obesity by promoting both glycemic control and weight loss. These agents enhance glucose-dependent insulin secretion, suppress glucagon release, slow gastric emptying, and increase satiety, leading to reduced food intake and significant weight loss. Their use has demonstrated superior reductions in glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) and body mass index compared to other second-line diabetes therapies, with additional benefits for cardiovascular risk profiles[1]. With recent research progress, dual agonists targeting both the GLP-1 and glucagon receptors (GRs) - such as survodutide, cotadutide, oxyntomodulin, and mazdutide - have been developed[2]. These drugs harness the insulinotropic and appetite-suppressing effects of GLP-1, in conjunction with the energy expenditure and hepatic fat reduction associated with GR activation. This dual pathway approach represents a promising advancement in diabetes and obesity management, offering improved metabolic outcomes that surpass those achievable with current single-agonist therapies[3]. Cotadutide (MEDI0382) is a twincretin, acting as a dual agonist for GLP-1 and GRs, activating them in a 5:1 ratio[4]. Cotadutide is a synthetic linear peptide composed of natural amino acids and a palmitic acid side chain, resulting in balanced dual GLP-1 and GR agonist activity[4]. The unique and overlapping effects of GLP-1 and glucagon support using dual RAs for cardiometabolic diseases. GLP-1 exerts insulinotropic, anorexigenic, and cardioprotective effects, while glucagon affects white and brown adipose tissue through catabolic and thermogenic pathways, enhancing energy expenditure, lipid oxidation, and hepatic metabolic flexibility. Their synergistic actions promote weight loss, improved glycemic control, and a reduced risk of hypoglycemia, along with broad cardiometabolic benefits[5,6]. Thus, as a dual GLP-1 and GR agonist, cotadutide enhances blood glucose regulation through insulinotropic effects and facilitates disease-modifying actions by modulating appetite and energy expenditure, thereby promoting weight loss[5].

Preclinical studies have demonstrated that activating the GLP-1 receptor counteracts glucagon-induced hepatic glucose production[4,7]. In rodent models of metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease, cotadutide administration led to a reduction in hepatic glycogen content, decreased inflammation, improved hepatic mitochondrial function, and reduced steatosis and liver fibrosis[7]. Multiple randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have been published assessing the safety and effectiveness of cotadutide as an anti-diabetic medication in individuals with T2D having overweight or obesity[8-16]. Parker et al[14] and Selvarajah et al[16] included individuals with chronic kidney disease. Many studies, including that of Nahra et al[12], have also examined hepatic outcomes in adults with overweight or obesity and T2D. Ali et al[17] published a systematic review (SR) and meta-analysis (MA) on the impact of cotadutide in patients with T2D in 2022. However, that SR/MA included only four RCTs and did not provide a detailed assessment of the safety profile[17]. De Block et al[18] also published another SR/MA in 2021, evaluating the efficacy and safety of high-dose GLP-1, GLP-1/glucose-dependent insulinotropic peptide, and GLP-1/GR agonists in T2D; however, they included only two published trials of cotadutide[18]. Therefore, it is crucial to conduct a comprehensive updated SR/MA that evaluates the safety and effectiveness of cotadutide in T2D, including all published RCTs to date. With this background, we conducted this SR/MA to thoroughly assess and summarize the safety profile, glycemic control, and weight-loss effects of cotadutide in individuals with T2D who have overweight or obesity. The primary outcomes of this SR/MA were the changes in HbA1c and the percent changes in body weight from baseline, while the secondary outcomes included the changes in fasting plasma glucose (FPG), absolute changes in body weight, and adverse events (AEs).

This SR/MA was conducted following the procedures outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions and is reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses checklist[19,20]. It has been registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (CRD

Several databases and registries were systematically searched, including MEDLINE (via PubMed), Scopus, Web of Science, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, and ClinicalTrials.gov. The search spanned these sources from their inception to May 15, 2025. Using the Boolean operators “AND” and “OR”, the following terms were searched: “glucagon-like peptide-1/glucagon dual agonist”, “twincretin”, “cotadutide”, “MEDI0382”, “type 2 diabetes”, “type 2 diabetes mellitus”, “non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus”, “T2DM”, and “T2D”. The search terms targeted the titles, abstracts, and keywords of the documents, with no language restriction, to find published studies. The full search strategies are provided in Supplementary material. Additionally, the process included reviewing the references cited in the articles gathered for this research, as well as relevant journals.

The Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcomes, and Study design served as the framework for establishing eligibility criteria for the clinical trials in this SR/MA. The patient population consisted of individuals with T2D; the intervention was the use of cotadutide in the treatment group; the control included patients either on placebo or any other approved glucose-lowering drug (GLD) for managing T2D; the outcomes assessed included the impact on HbA1c, body weight, and AEs; and the RCTs were considered the study type for inclusion. Only those studies were included in this SR/MA that had at least two treatment arms/groups, with one having patients with T2D on cotadutide either alone or as part of a standard treatment regimen, and the other arm/group receiving either a placebo or any other GLD in place of cotadutide. Nonrandomized trials, retrospective studies, pooled analyses of clinical trials, conference proceedings, case reports, and articles that did not provide data on outcomes of interest were excluded. Clinical trials that included animals, healthy humans, or individuals without T2D, as well as RCTs involving patients with type 1 diabetes, were also excluded. The study selection process involved four independent authors who, after removing duplicates, assessed titles and abstracts according to predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. This screening eliminated clearly irrelevant studies, allowing potentially eligible ones to move forward. After the authors reached a consensus, they retrieved and in

The co-primary outcomes of interest were the changes in HbA1c and the percent changes in body weight from baseline. The secondary outcomes included the changes in FPG, absolute changes in body weight, and AEs, including gas

Four authors independently extracted data using standard forms. When multiple publications from the same study group were identified, results were combined, and relevant data from each report were included in the analysis. Data on primary and secondary outcomes, as mentioned above, were collected. Patient characteristics, including demographic details and comorbidities, from both included and excluded studies in the analysis, were recorded in a table. Any disagreements were resolved by consensus.

The Supplementary material of the relevant studies were carefully reviewed. Any relevant information was obtained through written email communication with the corresponding author of the relevant article and was thoughtfully incorporated into the MA. A thorough scrutiny of key numerical data, including the number of individuals screened and randomized, as well as a meticulous examination of intention-to-treat, as-treated, and per-protocol populations, was diligently conducted. Additionally, attrition rates, including dropouts, losses to follow-up, and withdrawals, were thoroughly investigated.

Three authors independently performed the risk of bias (RoB) assessment using version 2 of the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool for randomized trials (RoB2)[21]. The domains covered by RoB2 encompass all types of bias currently recognized as affecting the results of RCTs, such as bias arising from the randomization process, bias due to deviations from intended interventions, bias from missing outcome data, bias in outcome measurement, and bias in the selection of reported results. The RoB judgment categorized each domain into one of three levels: Low RoB, some concerns, or high RoB. The least favorable assessment across the bias domains was considered the overall RoB for the result[21]. All disagreements were settled through consensus. The Risk-of-bias VISualization (robvis) web app was used to create RoB plots[22].

The Review Manager computer program, version 7.2.0, was used to conduct meta-analyses and generate forest plots[23]. The results of the outcomes were expressed as mean differences (MDs) for continuous variables and as risk ratios (RRs) for dichotomous variables with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The analysis of outcomes was stratified according to whether the control group received a placebo, denoted as the placebo control group (PCG), or an active comparator (any other approved GLD), referred to as the active control group (ACG). The left side of the forest plot favored the cotadutide group, while the right side favored the PCG or ACG. Random-effects analysis models were selected to address the expected heterogeneity resulting from variations in population characteristics and study duration. The inverse variance statistical method was utilized in all instances. CI calculated by the Wald-type method. Tau2 was estimated by the DerSimonian and Laird method. The SR/MA included forest plots that combined data from at least two trials. A significance level of P < 0.05 was applied.

The assessment of heterogeneity was initially performed by examining forest plots. Subsequently, χ2 tests were conducted using N-1 degrees of freedom and a significance level of 0.05 to assess statistical significance. The I2 test was also used in the subsequent analysis. Thresholds for I² values were 25% for low heterogeneity, 50% for moderate heterogeneity, and 75% for high heterogeneity[24].

The Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation methodology evaluated the quality of evidence for the primary outcomes of the MA[25]. The process of creating the summary of findings table and assessing the quality of evidence as “high”, “moderate”, “low”, or “very low” has been previously described[26].

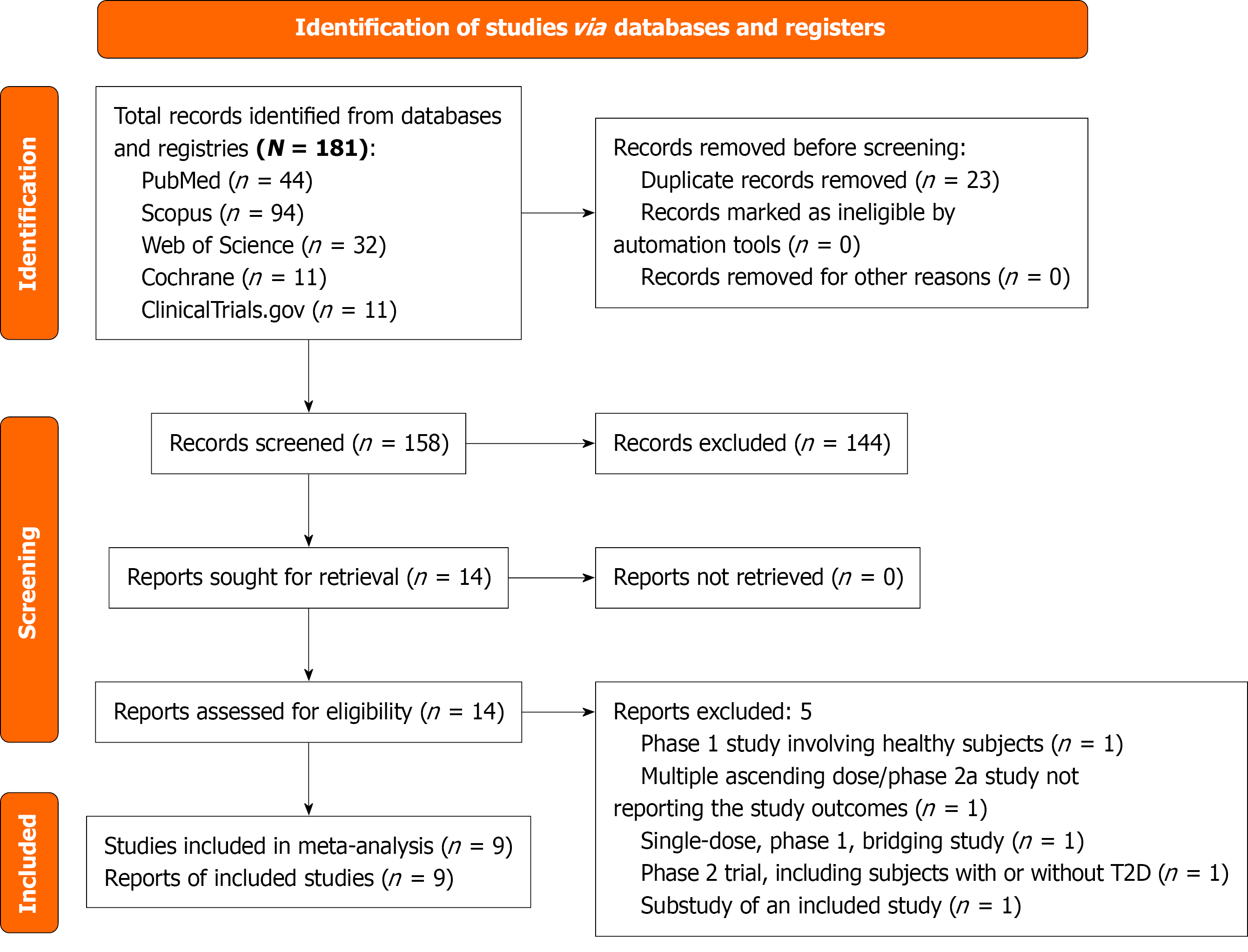

The initial search retrieved 181 articles, which were narrowed down to 14 after screening titles, abstracts, and full texts. A comprehensive review yielded nine RCTs with nine published reports, involving 1525 subjects that met all the inclusion criteria (Figure 1)[8-16]. Five studies were excluded: Ambery et al[27] was a phase 1 RCT conducted among healthy humans, Bosch et al[28] was a multiple ascending dose/phase 2a study that did not report the outcomes of interest, Klein et al[29] was a singledose, phase 1, bridging study and not all the study subjects had diabetes, Shankar et al[30] was a phase 2 trial involving subjects with metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease with or without T2D, and Yu et al[31] was a sub study of the included study by Selvarajah et al[16].

The details of the studies included in this meta-analysis are presented in Table 1. The Ambery et al’s study[27] was a combined multiple-ascending dose and Phase 2a trial; we included the Phase 2a portion, which had two arms: MEDI0382 at up to 200 μg/day and placebo[8]. The Asano et al’s study[9] was divided into two parts: Phase 1 and phase 2a. The phase 2a segment, which involved three groups receiving cotadutide at doses of 100 μg/day, 200 μg/day, and 300 μg/day, along with a placebo group, was specifically investigated[9]. The Asano et al’s study[10] was a phase 1 trial that included a cotadutide group receiving 600 μg or the highest dose tolerated clinically, along with a placebo group. The Golubic et al’s study[11] was a phase 2a trial that included a cotadutide 200 μg group and a placebo group. The Nahra et al’s study[12] was a phase 2b trial with three groups receiving cotadutide at doses of 100 μg/day, 200 μg/day, and 300 μg/day, along with two control groups: One group received liraglutide (up to 1.8 mg/day) and a placebo group. Parker et al’s study[13], a phase 2b trial, had two cohorts: The trial drug was up-titrated weekly in cohort 1 and biweekly in cohort 2. We considered only cohort 1 (comprising a cotadutide 300 μg group and a placebo group) for the analysis in this SR/MA, as it had a similar titration schedule to those of the other included trials. Another Phase 2a trial, Parker et al’s study[14], had a cotadutide 300 μg group and a placebo group. The Parker et al’s study[15] was a phase 2a trial comprising two parts: Part A (referred to as Parker 2023-A in this article) included a cotadutide 300 μg group and a placebo group, while part B (referred to as Parker 2023-B) involved a cotadutide 300 μg group, a placebo group, and a liraglutide group (up to 1.8 mg/day)[15]. The Selvarajah et al’s study[16] was a phase 2b trial with three groups of cotadutide (100 μg/day, 300 μg/day, and 600 μg/day), along with two control groups: A placebo group and a se

| Ref. | Trial ID | Country | Phase of the trial | Major inclusion criteria | Trial arms (sample size, n) | Age (years) | Male (%) | Weight (kg) | BMI kg/m2 | HbA1c (%) | Trial duration |

| Ambery et al[8] | NCT02548585 | Germany | Phase 2a | Age: 18-65 years; HbA1c: 6.5%-8.5%; BMI: 27-40 kg/m2 | MEDI0382 up to 200 μg (n = 25) | 57.7 ± 6.0 | 52 | 95.9 ± 18.9 | 32.0 ± 4.4 | 7.2 ± 0.6 | 41 days |

| Placebo (n = 26) | 56.0 ± 7.2 | 58 | 99.9 ± 15.1 | 33.4 ± 3.4 | 7.3 ± 0.7 | ||||||

| Asano et al[9] | NCT03645421 | Japan | Phase 2a | Age: ≥20 years; HbA1c: 7%-10.5%; BMI: 24-40 kg/m2 | Cotadutide 100 μg (n = 15) | 56.7 ± 10.7 | 53 | 77.08 ± 14.21 | 28.82 ± 4.70 | 7.71 ± 0.44 | 48 days |

| Cotadutide 200 μg (n = 15) | 58.7 ± 11.3 | 87 | 73.05 ± 8.29 | 26.42 ± 1.81 | 8.2 ± 0.82 | ||||||

| Cotadutide 300 μg (n = 15) | 57.5 ± 9.2 | 87 | 76.68 ± 9.97 | 26.99 ± 2.32 | 7.77 ± 0.85 | ||||||

| Placebo (n = 16) | 60.0 ± 8.6 | 81 | 78.33 ± 12.8 | 28.53 ± 4.15 | 8.15 ± 0.90 | ||||||

| Asano et al[10] | NCT04208620 | Japan | Phase 1 | Age: 20-74 years; HbA1c: 6.5%-8.5%; BMI: 25-35 kg/m2 | Cotadutide 600 μg or HCTD (n = 12) | 58.5 (34-69) | 58.3 | 77.05 (62.3-84.8) | 27.185 (25.21-34.71) | 7.41 ± 0.67 | 10 weeks (70 days) |

| Placebo (n = 4) | 60.0 (46-63) | 75.0 | 79.50 (69.8-80.5) | 28.045 (26.17-32.12) | 7.95 ± 0.45 | ||||||

| Golubic et al[11] | NCT03596177 | United Kingdom | Phase 2a | Age: 30-75 years; HbA1c: ≤ 8%; BMI: 28-40 kg/m2 | Cotadutide 200 μg (n = 19) | 59.5 ± 8.4 | 94.7 | 99.3 ± 10.8 | 32.2 ± 2.2 | 53 (5) mmol/mol | 42 days |

| Placebo (n = 9) | 62.2 ± 7.2 | 77.8 | 101.4 ± 16.0 | 34.5 ± 2.8 | 50 (4) mmol/mol | ||||||

| Nahra et al[12] | NCT03235050 | Eight countries | Phase 2b | Age: ≥18 years; HbA1c: 7%-10.5%; BMI: ≥ 25 kg/m2 | Cotadutide 100 μg (n = 256) | 57.6 ± 9.9 | 43 | 99.0 ± 20.3 | 35.0 ± 5.7 | 8.1 ± 0.9 | 54 weeks (378 days) |

| Cotadutide 200 μg (n = 256) | 57.3 ± 9.9 | 43 | 98.1 ± 20.2 | 34.9 ± 5.4 | 8.2 ± 1.0 | ||||||

| Cotadutide 300 μg (n = 256) | 56.3 ± 10.2 | 50 | 100.8 ± 19.6 | 35.2 ± 5.4 | 8.1 ± 1.1 | ||||||

| Liraglutide 18 mg (n = 110) | 55.5 ± 9.8 | 46 | 102.1 ± 22.7 | 35.4 ± 6.1 | 8.1 ± 1.0 | ||||||

| Placebo (n = 112) | 57.3 ± 9.5 | 51 | 98.1 ± 19.8 | 34.2 ± 5.1 | 8.2 ± 1.1 | ||||||

| Parker et al[13] | NCT03244800 | Germany | Phase 2b | Age: ≥ 18 years; HbA1c: 6.5%-8.5%; BMI: 27-40 kg/m2 | Cohort 1: Cotadutide 300 μg (n = 26) | 58.7 ± 8.5 | 73 | 95.6 ± 17.2 | 31.5 ± 3.5 | 7.26 ± 0.58 | 49 days |

| Cohort 1: Placebo (n = 13) | 60.2 ± 5.6 | 69 | 93.8 ± 21.0 | 31.6 ± 3.8 | 7.19 ± 0.52 | ||||||

| Parker et al[14] | NCT03550378 | United Kingdom | Phase 2a | Age: 18-84 years; HbA1c: 6.5%-10.5%; BMI: 25-45 kg/m2; CKD (eGFR 30-59 mL/minute/1.73 m2) | Cotadutide 300 μg (n = 21) | 71.1 ± 7.4 | 57.1 | 94.7 ± 17.6 | 32.4 ± 4.1 | 7.85 ± 0.7 | 32 days |

| Placebo (n = 20) | 70.9 ± 4.7 | 45 | 91.6 ± 15.8 | 32.9 ± 5.5 | 7.88 ± 1.3 | ||||||

| Parker et al[15] | NCT03555994 | Sweden and Netherlands | Phase 2a (Part A) | Age: ≥ 18 years; HbA1c: ≤ 8%; BMI: 27-40 kg/m2 | Cotadutide 300 μg (n = 12) | 65.8 ± 7.3 | 58 | 96.2 ± 7.7 | 31.8 ± 3.0 | 6.5 ± 0.6 | 28 days |

| Placebo (n = 9) | 69.3 ± 5.7 | 67 | 99.6 ± 20.1 | 32.7 ± 4.8 | 6.3 ± 0.7 | ||||||

| Phase 2a (Part B) | Similar to part A | Cotadutide 300 μg (n = 9) | 61.8 ± 7.5 | 67 | 94.0 ± 14.6 | 31.9 ± 4.0 | 6.8 ± 0.66 | 35 days | |||

| Placebo (n = 11) | 64.0 ± 10.7 | 82 | 93.4 ± 11.8 | 30.08 ± 4.0 | 7.1 ± 0.63 | ||||||

| Liraglutide 1.8 mg (n = 10) | 65.2 ± 9.1 | 60 | 91.5 ± 10.1 | 30.2 ± 2.3 | 6.8 ± 0.73 | ||||||

| Selvarajah et al[16] | NCT04515849 | Multiple countries | Phase 2b | Age: 18-79 years; HbA1c: 6.5%-12.5%; BMI: ≥ 25 kg/m2 (≥ 23 kg/m2 in Japan); CKD (eGFR 20-90 mL/minute/1.73 m2, UACR > 50 mg/mL) | Cotadutide 100 μg (n = 52) | 67.2 ± 7.3 | 82.7 | 93.79 ± 19.94 | 32.15 ± 5.22 | 8 ± 1.07 | 14 weeks (98 days) |

| Cotadutide 300 μg (n = 49) | 65.7 ± 8.8 | 93.9 | 94.01 ± 18.79 | 32.26 ± 5.76 | 7.91 ± 1.1 | ||||||

| Cotadutide 600 μg (n = 51) | 66.1 ± 7.4 | 80.4 | 93.69 ± 22.66 | 32.14 ± 5.65 | 8.1 ± 1.12 | ||||||

| Placebo (n = 51) | 69.5 ± 7.3 | 74.5 | 93.15 ± 19.28 | 32.33 ± 6.05 | 7.84 ± 0.81 | ||||||

| Semaglutide 1 mg (n = 45) | 67.0 ± 7.3 | 73.3 | 97.52 ± 19.45 | 34.41 ± 6.54 | 8.04 ± 1.18 |

The specific and overall RoB in the included studies is illustrated in Supplementary Figure 1. Five studies (n = 55.5%) had a low overall RoB[8,9,13,14,15], and the other four (n = 45.5%) had some concerns[10,11,12,16]. All trials with some bias concerns had biases due to missing outcome data, except for Selvarajah et al[16], where deviations from intended interventions caused the bias. Publication bias was not formally assessed because there were not enough RCTs (at least 10) in the forest plots[32]. However, publication bias was strongly suspected given a small number of early-phase, sponsor-funded RCTs.

The certainty of evidence grades for the primary outcomes of the MA are provided in Supplementary Table 2.

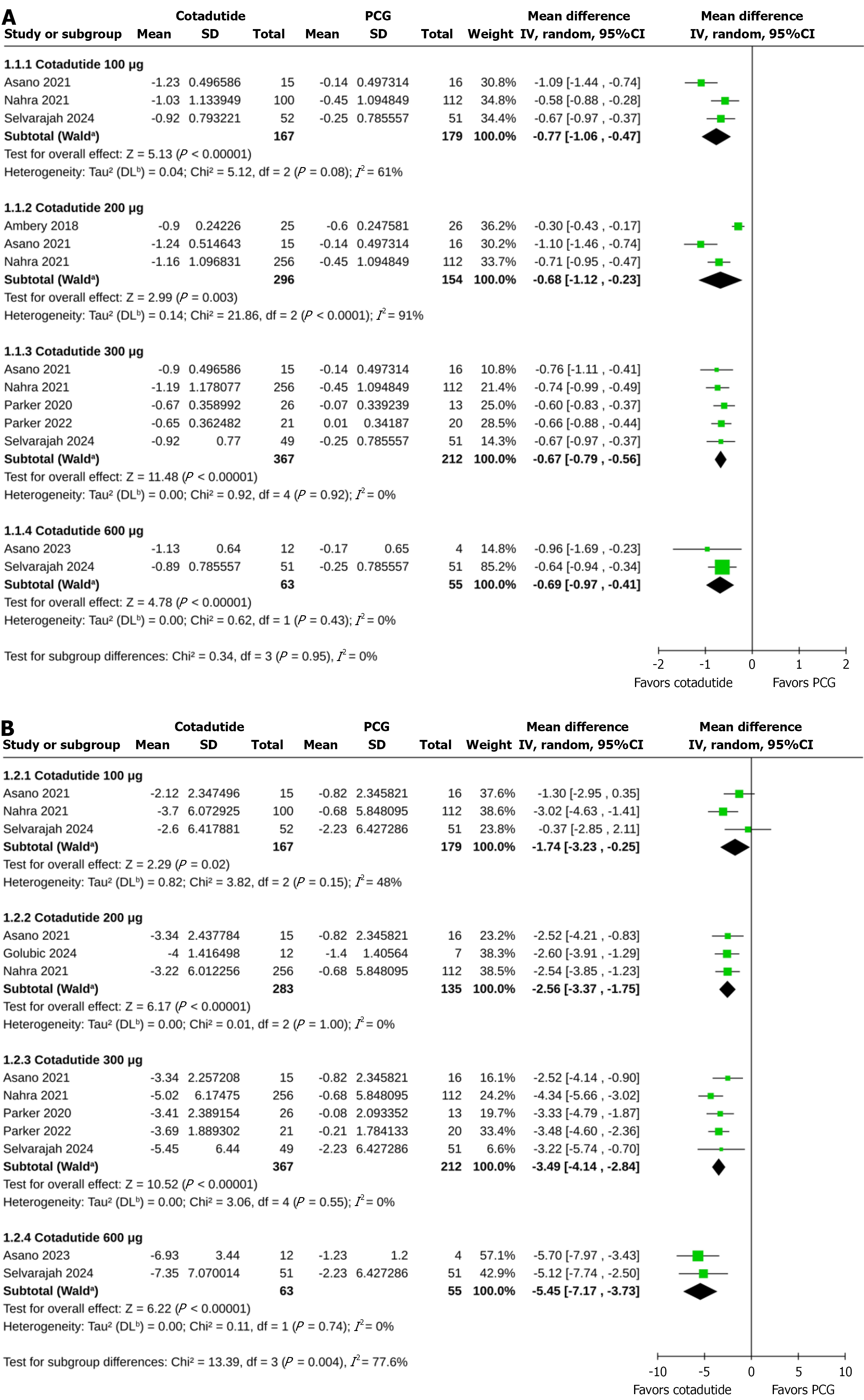

HbA1c: Compared to the PCG, greater reductions in HbA1c were achieved with cotadutide 100 μg (MD -0.77%, 95%CI: -1.06 to -0.47, P < 0.00001, I2 = 61%, very low certainty of evidence), 200 μg (MD -0.68%, 95%CI: -1.12 to -0.23, P = 0.003, I2 = 91%, very low certainty of evidence), 300 μg (MD -0.67%, 95%CI: -0.79 to -0.56, P < 0.00001, I2 = 0%, low certainty of evidence), and 600 μg (MD -0.69%, 95%CI: -0.97 to -0.41, P < 0.00001, I2 = 0%, very low certainty of evidence) with no subgroup differences across the cotadutide doses (P for subgroup differences = 0.95; Figure 2A). Due to an insufficient number of studies, subgroup analysis based on trial durations was only possible for cotadutide 300 μg vs placebo. The reduction in HbA1c with cotadutide 300 μg compared to PCG was similar in trials of < 10 weeks (MD -0.65%, 95%CI: -0.80 to -0.51, P < 0.00001, I2 = 0%) and ≥ 10 weeks duration (MD -0.71%, 95%CI: -0.90 to -0.52, P < 0.00001, I2 = 0%; P for subgroup differences = 0.63; Supplementary Figure 2). Compared to the ACG, cotadutide 100 μg (MD 0.21%, 95%CI: 0.00-0.42, P = 0.05, I2 = 0%) and 300 μg (MD 0.12%, 95%CI: -0.17 to 0.41, P = 0.43, I2 = 59%) achieved similar changes in HbA1c (Supplementary Figure 3).

Percent change in body weight: Cotadutide 100 μg (MD -1.74%, 95%CI: -3.23 to -0.25, P = 0.02, I2 = 48%, very low certainty of evidence), 200 μg (MD -2.56%, 95%CI: -3.37 to -1.75, P < 0.00001, I2 = 0%, very low certainty of evidence), 300 μg (MD -3.49%, 95%CI: -4.14 to -2.84, P < 0.00001, I2 = 0%, very low certainty of evidence), and 600 μg (MD -5.45%, 95%CI: -7.17 to -3.73, P < 0.00001, I2 = 0%, very low certainty of evidence) achieved greater percent reductions in body weight from baseline than the PCG; the extent of weight loss increased with higher doses of cotadutide (P for subgroup differences = 0.004; Figure 2B). The percent reduction in body weight with cotadutide 300 μg compared to PCG was similar in trials of < 10 weeks (MD -3.21%, 95%CI: -4.00 to -2.43, P < 0.00001, I2 = 0%) and ≥ 10 weeks (MD -4.10%, 95%CI: -5.27 to -2.93, P < 0.00001, I2 = 0%) duration (P for subgroup differences = 0.22; Supplementary Figure 4). Compared to the ACG, the percent reduction in body weight was similar with cotadutide 100 μg (MD 1.93%, 95%CI: -2.74 to 6.60, P = 0.42, I2 = 91%) and cotadutide 300 μg (MD -0.24%, 95%CI: -3.39 to 2.92, P = 0.88, I2 = 82%; Supplementary Figure 5).

FPG: Compared to the PCG, greater reductions in FPG were achieved with cotadutide 100 μg (MD -1.69 mmol/L, 95%CI: -3.10 to -0.28, P = 0.02, I2 = 89%), 200 μg (MD -1.83 mmol/L, 95%CI: -2.43 to -1.22, P < 0.00001, I2 = 77%), and 300 μg (MD -1.89 mmol/L, 95%CI: -2.41 to -1.37, P < 0.00001, I2 = 74%) with no subgroup differences across the cotadutide doses (P for subgroup differences = 0.37; Supplementary Figure 6). Cotadutide 300 μg and ACG achieved identical changes in FPG (MD -0.12 mmol/L, 95%CI: -0.44 to 0.20, P = 0.46, I2 = 0%; Supplementary Figure 7).

Absolute changes in body weight: Greater absolute reductions in body weight were achieved with cotadutide 200 μg (MD -2.24 kg, 95%CI: -2.88 to -1.60, P < 0.00001, I2 = 0%), and 300 μg (MD -3.11 kg, 95%CI: -3.82 to -2.41, P < 0.00001, I2 = 40%) compared to the PCG, with no subgroup differences across the cotadutide doses (P for subgroup differences = 0.18; Supplementary Figure 8). Cotadutide 300 μg and ACG achieved identical absolute changes in body weight (MD -0.93 kg, 95%CI: -2.44 to 0.58, P = 0.23, I2 = 30%; Supplementary Figure 9).

The safety outcomes of cotadutide (pooled and individual doses) compared to placebo are summarized in Table 2. In all RCTs, AEs were categorized according to the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities system organ class and preferred terms. Cotadutide (pooled doses) increased the risk of treatment-emergent AEs (TEAEs) compared to placebo (RR = 1.20, 95%CI: 1.07-1.35, P = 0.002, I2 = 24%); however, this risk was only significant for the 300 μg dose of cotadutide, not for the other doses. The risk of treatment-related AEs (TRAEs) was greater with pooled doses (RR = 1.96, 95%CI: 1.50-2.56, P < 0.00001, I2 = 26%) and with doses of 200 μg and 300 μg of cotadutide. The risk of serious AEs was not higher with pooled (RR = 0.99, 95%CI: 0.62-1.58, P = 0.97, I2 = 0%) or individual doses of cotadutide than PCG. An increased risk of discontinuing the study drug due to AEs was observed with pooled doses of cotadutide (RR = 2.54, 95%CI: 1.39-4.64, P = 0.002, I2 = 0%); however, this risk was only significant for the 200 μg dose and not for the other doses. The risk of any gastrointestinal AEs was higher with pooled doses (RR = 1.86, 95%CI: 1.45-2.38, P < 0.00001, I2 = 0%) and with doses of 200 μg and 300 μg of cotadutide. Cotadutide did not increase the risk of abdominal distension (for pooled doses: RR = 2.73, 95%CI: 0.69-10.77, P = 0.15, I2 = 0%), abdominal pain (for pooled doses: RR = 1.18, 95%CI: 0.45-3.13, P = 0.73, I2 = 0%), or gastroesophageal reflux disease (for pooled doses: RR = 2.12, 95%CI: 0.46-9.78, P = 0.33, I2 = 0%). The risk of dyspepsia was increased with pooled (RR = 3.46, 95%CI: 1.71-7.02, P = 0.0006, I2 = 0%), 200 (RR = 4.22, 95%CI: 1.41-12.63, P = 0.01, I2 = 0%), and 300 μg (RR = 4.07, 95%CI: 1.81-9.15, P = 0.0007, I2 = 0%) doses of cotadutide but not with its 100 and 600 μg doses. The risk of nausea was increased with the pooled doses (RR = 3.13, 95%CI: 2.21-4.45, P < 0.00001, I2 = 0%), as well as with all individual doses (100 μg, 200 μg, 300 μg, and 600 μg) of cotadutide. Higher risk of vomiting was observed with pooled (RR = 3.84, 95%CI: 2.13-6.91, P < 0.00001, I2 = 0%), 200 μg (RR = 4.55, 95%CI: 2.14-9.68, P < 0.0001, I2 = 0%), and 300 μg (RR = 3.88, 95%CI: 2.00-7.55, P < 0.0001, I2 = 0%) doses of cotadutide but not with its 100 μg and 600 μg doses. The risk of eructation was higher with 200 μg (RR = 5.13, 95%CI: 1.20-21.99, P = 0.03, I2 = 0%) but not with the pooled or the other doses of cotadutide. The pooled doses (RR = 2.26, 95%CI: 1.16-4.40, P = 0.02, I2 = 0%) and 300 μg dose (RR = 2.74, 95%CI: 1.06-7.13, P = 0.04, I2 = 0%) of cotaduide increased the risk of constipation; such effects were not observed with other doses. Cotadutide did not increase the risk diarrhea (for pooled doses: RR = 1.16, 95%CI: 0.61-2.19, P = 0.65, I2 = 26%) or flatulence (for pooled doses: RR = 1.49, 95%CI: 0.43-5.18, P = 0.53, I2 = 0%). More subjects experienced decreased appetite with cotadutide at its pooled doses (RR = 3.81, 95%CI: 1.80-8.06, P = 0.0005, I2 = 0%) and doses of 200 μg and 300 μg, but not at the 100 μg dose. The risks of fatigue (for pooled doses: RR = 2.34, 95%CI: 0.92-5.95, P = 0.07, I2 = 0%) and headache (for pooled doses: RR = 1.59, 95%CI: 0.91-2.77, P = 0.11, I2 = 0%) were not increased with cotadutide. A higher risk of dizziness was observed with cotadutide 300 μg (RR = 2.40, 95%CI: 1.07-5.37, P = 0.03, I2 = 0%), but not with pooled or other individual doses of cotadutide. Cotadutide had an identical risk of hypoglycemia to placebo (for pooled doses: RR = 1.16, 95%CI: 0.64-2.09, P = 0.77, I2 = 0%).

| Outcome variables (categorical) | Cotadutide dose | Number of studies reporting the outcome | Number of participants with outcome/participants analyzed | Pooled effect size, RR (95%CI) | I2 (%) | P value | |

| Cotadutide | PCG | ||||||

| TEAEs | All doses | 9 | 739/931 | 175/269 | 1.20 (1.07-1.35) | 24 | 0.002 |

| 100 μg/day | 3 | 124/170 | 114/179 | 1.13 (0.99-1.29) | 0 | 0.08 | |

| 200 μg/day | 4 | 252/314 | 103/161 | 1.21 (0.98-1.49) | 50 | 0.07 | |

| 300 μg/day | 6 | 313/387 | 146/232 | 1.26 (1.12-1.41) | 6 | 0.0001 | |

| 600 μg/day | 2 | 50/60 | 40/55 | 1.46 (0.51-4.22) | 50 | 0.48 | |

| TRAEs | All doses | 5 | 418/697 | 57/185 | 1.96 (1.50-2.56) | 26 | < 0.00001 |

| 200 μg/day | 3 | 184/299 | 42/145 | 1.97 (1.21-3.20) | 67 | 0.007 | |

| 300 μg/day | 3 | 188/298 | 39/152 | 2.40 (1.82-3.15) | 0 | < 0.00001 | |

| Serious AEs | All doses | 9 | 84/931 | 20/269 | 0.99 (0.62-1.58) | 0 | 0.97 |

| 100 μg/day | 3 | 17/170 | 17/179 | 1.06 (0.56-2.00) | 0 | 0.86 | |

| 200 μg/day | 4 | 35/314 | 13/161 | 1.18 (0.65-2.14) | 0 | 0.59 | |

| 300 μg/day | 6 | 27/387 | 19/232 | 0.81 (0.46-1.43) | 0 | 0.47 | |

| 600 μg/day | 2 | 5/60 | 5/55 | 1.06 (0.33-3.44) | NA | 0.92 | |

| Discontinuation of the study drug due to AEs | All doses | 7 | 134/880 | 10/230 | 2.54 (1.39-4.64) | 0 | 0.002 |

| 100 μg/day | 3 | 15/170 | 9/179 | 1.31 (0.22-7.83) | 71 | 0.76 | |

| 200 μg/day | 3 | 47/289 | 5/135 | 3.75 (1.65-8.56) | 0 | 0.002 | |

| 300 μg/day | 5 | 62/361 | 10/219 | 2.40 (0.92-6.29) | 27 | 0.08 | |

| 600 μg/day | 2 | 10/60 | 4/55 | 2.66 (0.89-7.90) | NA | 0.08 | |

| Any GI AEs | All doses | 4 | 380/675 | 47/155 | 1.86 (1.45-2.38) | 0 | < 0.00001 |

| 200 μg/day | 2 | 167/281 | 44/138 | 1.81 (1.25-2.60) | 44 | 0.001 | |

| 300 μg/day | 2 | 163/282 | 33/125 | 2.17 (1.60-2.96) | 0 | < 0.00001 | |

| Abdominal distension | All doses | 5 | 10/264 | 0/133 | 2.73 (0.69-10.77) | 0 | 0.15 |

| 100 μg/day | 2 | 1/67 | 0/67 | 2.94 (0.12-70.61) | NA | 0.51 | |

| 200 μg/day | 2 | 6/40 | 0/42 | 13.50 (0.80-227.75) | NA | 0.07 | |

| 300 μg/day | 4 | 3/106 | 0/107 | 2.76 (0.45-16.72) | 0 | 0.27 | |

| Abdominal pain | All doses | 7 | 11/308 | 4/153 | 1.18 (0.45-3.13) | 0 | 0.73 |

| 100 μg/day | 2 | 0/67 | 1/67 | 0.33 (0.01-7.85) | NA | 0.49 | |

| 200 μg/day | 3 | 3/58 | 2/49 | 0.87 (0.16-4.92) | 0 | 0.88 | |

| 300 μg/day | 5 | 6/132 | 2/120 | 1.67 (0.49-5.71) | 0 | 0.42 | |

| Dyspepsia | All doses | 8 | 82/886 | 6/253 | 3.46 (1.71-7.02) | 0 | 0.0006 |

| 100 μg/day | 2 | 8/155 | 2/163 | 3.67 (0.91-14.77) | 0 | 0.07 | |

| 200 μg/day | 3 | 27/299 | 3/145 | 4.22 (1.41-12.63) | 0 | 0.01 | |

| 300 μg/day | 5 | 46/372 | 5/216 | 4.07 (1.81-9.15) | 0 | 0.0007 | |

| 600 μg/day | 2 | 1/60 | 0/55 | 1.15 (0.06-23.88) | NA | 0.93 | |

| GERD | All doses | 6 | 9/282 | 0/140 | 2.12 (0.46-9.78) | 0 | 0.33 |

| 100 μg/day | 2 | 1/67 | 0/67 | 2.94 (0.12-70.61) | NA | 0.51 | |

| 200 μg/day | 3 | 1/58 | 0/49 | 1.26 (0.06-27.82) | NA | 0.88 | |

| 300 μg/day | 4 | 4/106 | 0/107 | 3.66 (0.61-21.81) | 0 | 0.15 | |

| Nausea | All doses | 9 | 312/931 | 28/269 | 3.13 (2.21-4.45) | 0 | < 0.00001 |

| 100 μg/day | 3 | 31/170 | 15/179 | 2.22 (1.25-3.95) | 0 | 0.007 | |

| 200 μg/day | 4 | 118/314 | 20/161 | 3.05 (1.98-4.68) | 0 | < 0.00001 | |

| 300 μg/day | 6 | 142/387 | 21/232 | 3.47 (2.29-5.27) | 0 | < 0.00001 | |

| 600 μg/day | 2 | 21/60 | 2/55 | 6.82 (1.93-24.13) | 0 | 0.003 | |

| Vomiting | All doses | 9 | 154/931 | 9/269 | 3.84 (2.13-6.91) | 0 | < 0.00001 |

| 100 μg/day | 3 | 15/170 | 6/179 | 2.45 (0.99-6.05) | 0 | 0.05 | |

| 200 μg/day | 4 | 68/314 | 6/161 | 4.55 (2.14-9.68) | 0 | < 0.0001 | |

| 300 μg/day | 6 | 63/387 | 8/232 | 3.88 (2.00-7.55) | 0 | < 0.0001 | |

| 600 μg/day | 2 | 8/60 | 1/55 | 4.13 (0.75-22.66) | 0 | 0.10 | |

| Eructation | All doses | 6 | 39/854 | 2/229 | 2.74 (0.89-8.41) | 0 | 0.08 |

| 100 μg/day | 2 | 2/152 | 1/163 | 1.41 (0.09-22.80) | 38 | 0.81 | |

| 200 μg/day | 3 | 21/299 | 1/145 | 5.13 (1.20-21.99) | 0 | 0.03 | |

| 300 μg/day | 4 | 16/352 | 1/196 | 2.79 (0.62-12.48) | 0 | 0.18 | |

| Constipation | All doses | 8 | 55/914 | 7/249 | 2.26 (1.16-4.40) | 0 | 0.02 |

| 100 μg/day | 3 | 4/170 | 4/179 | 0.99 (0.26-3.83) | 0 | 0.99 | |

| 200 μg/day | 4 | 19/314 | 5/161 | 2.20 (0.88-5.51) | 0 | 0.09 | |

| 300 μg/day | 5 | 24/366 | 4/212 | 2.74 (1.06 -7.13) | 0 | 0.04 | |

| 600 μg/day | 2 | 8/64 | 2/55 | 2.25 (0.55-9.27) | 0 | 0.26 | |

| Diarrhea | All doses | 8 | 117/905 | 22/256 | 1.16 (0.61-2.19) | 26 | 0.65 |

| 100 μg/day | 3 | 18/170 | 12/179 | 1.58 (0.79-3.14) | 0 | 0.19 | |

| 200 μg/day | 4 | 57/314 | 17/161 | 1.14 (0.38-3.39) | 64 | 0.81 | |

| 300 μg/day | 5 | 38/361 | 15/219 | 1.37 (0.65-2.86) | 11 | 0.41 | |

| 600 μg/day | 2 | 4/60 | 2/55 | 1.47 (0.32-6.67) | 0 | 0.62 | |

| Flatulence | All doses | 5 | 9/242 | 2/117 | 1.49 (0.43-5.18) | 0 | 0.53 |

| 200 μg/day | 2 | 1/43 | 1/33 | 0.67 (0.07-6.10) | 0 | 0.72 | |

| 300 μg/day | 3 | 5/96 | 1/84 | 2.45 (0.50-12.08) | 0 | 0.27 | |

| Decreased appetite | All doses | 8 | 70/919 | 5/265 | 3.81 (1.80-8.06) | 0 | 0.0005 |

| 100 μg/day | 3 | 3/170 | 2/179 | 1.34 (0.14-13.05) | 31 | 0.80 | |

| 200 μg/day | 4 | 25/314 | 1/161 | 6.39 (1.79-22.84) | 0 | 0.004 | |

| 300 μg/day | 6 | 37/387 | 5/232 | 3.57 (1.56-8.20) | 0 | 0.003 | |

| Fatigue | All doses | 4 | 19/224 | 4/110 | 2.34 (0.92-5.95) | 0 | 0.07 |

| 300 μg/day | 3 | 10/96 | 4/84 | 1.72 (0.58-5.15) | 4 | 0.33 | |

| Dizziness | All doses | 8 | 51/920 | 11/265 | 1.51 (0.80-2.87) | 0 | 0.20 |

| 100 μg/day | 3 | 5/167 | 4/179 | 1.36 (0.37-4.98) | 0 | 0.64 | |

| 200 μg/day | 4 | 17/314 | 8/161 | 1.19 (0.52-2.74) | 0 | 0.68 | |

| 300 μg/day | 6 | 27/388 | 6/232 | 2.40 (1.07-5.37) | 0 | 0.03 | |

| Headache | All doses | 8 | 64/887 | 14/253 | 1.59 (0.91-2.77) | 0 | 0.11 |

| 100 μg/day | 2 | 4/152 | 4/163 | 1.08 (0.28-4.25) | 0 | 0.91 | |

| 200 μg/day | 3 | 26/299 | 7/145 | 1.75 (0.48-6.33) | 58 | 0.40 | |

| 300 μg/day | 5 | 30/373 | 10/216 | 1.60 (0.81-3.17) | 0 | 0.18 | |

| 600 μg/day | 2 | 4/63 | 1/55 | 2.14 (0.36-12.92) | 0 | 0.41 | |

| Hypoglycemia | All doses | 4 | 35/223 | 11/110 | 1.16 (0.64-2.09) | 0 | 0.63 |

| 300 μg/day | 3 | 13/95 | 11/84 | 1.11 (0.53-2.33) | 0 | 0.77 | |

Table 3 summarizes the safety outcomes of cotadutide, both pooled and individual doses, compared to the ACG. Compared to the ACG, the pooled doses of cotadutide did not significantly increase the risks of TEAEs (RR = 1.07, 95%CI: 0.83-1.36, P = 0.62, I2 = 77%), TRAEs (RR = 1.71, 95%CI: 0.77-3.80, P = 0.1, I2 = 84%), serious AEs (RR = 1.34, 95%CI: 0.75-2.41, P = 0.32, I2 = 0%), and discontinuing the study drug due to AEs (RR = 2.26, 95%CI: 0.15-34.46, P = 0.56, I2 = 91%). The risks of abdominal pain (RR = 0.89, 95%CI: 0.09-8.33, P = 0.92, I2 = 0%), dyspepsia (RR = 1.07, 95%CI: 0.83-1.36, P = 0.62, I2 = 77%), GERD (RR = 0.65, 95%CI: 0.16-2.58, P = 0.54, I2 = 0%), nausea (RR = 1.64, 95%CI: 0.57-4.70, P = 0.35, I2 = 82%), vomiting (RR = 1.61, 95%CI: 0.26-9.97, P = 0.61, I2 = 81%), eructation (RR = 1.09, 95%CI: 0.01-101.81, P = 0.97, I2 = 78%), constipation (RR = 1.47, 95%CI: 0.60-3.60, P = 0.39, I2 = 0%), diarrhea (RR = 1.70, 95%CI: 0.34-8.51, P = 0.52, I2 = 77%), decreased appetite (RR = 0.67, 95%CI: 0.09-5.23, P = 0.70, I2 = 73%), fatigue (RR = 2.03, 95%CI: 0.45-9.09, P = 0.35, I2 = 0%), dizziness (RR = 1.98, 95%CI: 0.41-9.46, P = 0.39, I2 = 26%), and headache (RR = 1.72, 95%CI: 0.33-8.96, P = 0.52, I2 = 37%) were statistically not higher with pooled cotadutide doses and ACG. The 100 μg and 200 μg doses of cotadutide also did not increase the risk of any of the AEs mentioned above compared to the ACG.

| Outcome variables (categorical) | Cotadutide dose | Number of studies reporting the outcome | No. of participants with outcome/participants analyzed | Pooled effect size, RR (95%CI) | I2 (%) | P value | |

| Cotadutide | ACG | ||||||

| TEAEs | All doses | 3 | 610/772 | 115/165 | 1.07 (0.83-1.36) | 77 | 0.62 |

| 100 μg/day | 2 | 118/155 | 107/155 | 1.05 (0.84-1.31) | 67 | 0.65 | |

| 300 μg/day | 3 | 251/313 | 115/165 | 1.07 (0.81-1.41) | 76 | 0.63 | |

| TRAEs | All doses | 2 | 356/621 | 32/120 | 1.71 (0.77-3.80) | 84 | 0.19 |

| 300 μg/day | 2 | 162/265 | 32/120 | 1.76 (0.75-4.14) | 86 | 0.19 | |

| Serious AEs | All doses | 3 | 80/772 | 12/165 | 1.34 (0.75-2.41) | 0 | 0.32 |

| 100 μg/day | 2 | 17/155 | 12/155 | 1.42 (0.70-2.87) | 0 | 0.33 | |

| 300 μg/day | 3 | 25/313 | 12/165 | 1.10 (0.57-2.15) | 0 | 0.78 | |

| Discontinuation of the study drug due to AEs | All doses | 3 | 121/772 | 9/165 | 2.26 (0.15-34.46) | 91 | 0.56 |

| 100 μg/day | 2 | 15/155 | 9/155 | 1.30 (0.05-37.17) | 90 | 0.88 | |

| 300 μg/day | 3 | 57/313 | 9/165 | 1.80 (0.04-73.66) | 92 | 0.76 | |

| Abdominal pain | All doses | 2 | 3/161 | 1/55 | 0.89 (0.09-8.33) | 0 | 0.92 |

| 300 μg/day | 2 | 1/58 | 1/55 | 0.92 (0.06-14.25) | NA | 0.95 | |

| Dyspepsia | All doses | 3 | 610/772 | 115/165 | 1.07 (0.83-1.36) | 77 | 0.62 |

| 100 μg/day | 2 | 118/155 | 107/155 | 1.05 (0.84-1.31) | 67 | 0.65 | |

| 300 μg/day | 3 | 251/313 | 115/165 | 1.07 (0.81-1.41) | 76 | 0.63 | |

| GERD | All doses | 2 | 6/161 | 4/55 | 0.65 (0.16-2.58) | 0 | 0.54 |

| 300 μg/day | 2 | 2/58 | 4/55 | 0.60 (0.12-2.96) | 0 | 0.53 | |

| Nausea | All doses | 3 | 243/772 | 29/165 | 1.64 (0.57-4.70) | 82 | 0.35 |

| 100 μg/day | 2 | 29/155 | 28/155 | 0.86 (0.27-2.79) | 79 | 0.80 | |

| 300 μg/day | 3 | 116/313 | 29/165 | 1.72 (0.47-6.37) | 82 | 0.41 | |

| Vomiting | All doses | 3 | 116/772 | 10/165 | 1.61 (0.26-9.97) | 81 | 0.61 |

| 100 μg/day | 2 | 12/155 | 9/155 | 1.04 (0.08-13.28) | 85 | 0.97 | |

| 300 μg/day | 3 | 46/313 | 10/165 | 1.38 (0.17-11.19) | 79 | 0.76 | |

| Eructation | All doses | 2 | 28/764 | 1/155 | 1.09 (0.01-101.81) | 78 | 0.97 |

| 100 μg/day | 2 | 2/155 | 1/155 | 1.31 (0.07-23.51) | 42 | 0.85 | |

| 300 μg/day | 2 | 12/305 | 1/155 | 1.97 (0.06-64.31) | 63 | 0.70 | |

| Constipation | All doses | 3 | 34/772 | 6/165 | 1.47 (0.60-3.60) | 0 | 0.39 |

| 100 μg/day | 2 | 3/155 | 4/155 | 0.70 (0.16-3.12) | 0 | 0.64 | |

| 300 μg/day | 3 | 17/313 | 6/165 | 1.59 (0.60-4.19) | 0 | 0.35 | |

| Diarrhea | All doses | 3 | 102/772 | 10/165 | 1.70 (0.34-8.51) | 77 | 0.52 |

| 100 μg/day | 2 | 17/155 | 10/155 | 1.42 (0.23-8.97) | 81 | 0.71 | |

| 300 μg/day | 3 | 33/313 | 10/165 | 1.59 (0.47-5.35) | 50 | 0.45 | |

| Decreased appetite | All doses | 3 | 36/772 | 11/165 | 0.67 (0.09-5.23) | 73 | 0.70 |

| 100 μg/day | 2 | 3/155 | 9/155 | 0.44 (0.01-27.33) | 81 | 0.69 | |

| 300 μg/day | 3 | 16/313 | 11/165 | 0.70 (0.07-6.61) | 71 | 0.76 | |

| Fatigue | All doses | 2 | 7/161 | 2/55 | 2.03 (0.45-9.09) | 0 | 0.35 |

| 300 μg/day | 2 | 3/58 | 2/55 | 1.39 (0.15-13.21) | 34 | 0.78 | |

| Dizziness | All doses | 3 | 38/773 | 3/165 | 1.98 (0.41-9.46) | 26 | 0.39 |

| 100 μg/day | 2 | 5/152 | 1/155 | 2.78 (0.26-30.23) | 30 | 0.40 | |

| 300 μg/day | 3 | 20/314 | 3/165 | 2.63 (0.46-15.08) | 38 | 0.28 | |

| Headache | All doses | 3 | 43/773 | 3/165 | 1.72 (0.33-8.96) | 37 | 0.52 |

| 100 μg/day | 2 | 4/152 | 2/155 | 1.59 (0.10-26.25) | 55 | 0.75 | |

| 300 μg/day | 3 | 21/314 | 3/165 | 1.85 (0.23-14.77) | 48 | 0.56 | |

This review summarizes the outcomes of nine RCTs (mostly phase 2 RCTs, n = 1525) with study durations ranging from 28 days to 378 days, comparing cotadutide with PCG/ACG. While five studies had a low RoB, the other four had some concerns. Compared to the PCG, greater reductions in HbA1c from baseline were achieved with cotadutide 100 μg (MD

Several incretin co-agonists have been studied in recent years, demonstrating outstanding beneficial effects in the therapeutic landscape for patients with obesity and T2D. The percentage reductions in HbA1c, ranging from 0.67% to 0.77% based on short-term RCTs included in this review, indicate that cotadutide is as effective as the first-generation GLP-1 RAs such as lixisenatide and exenatide[33], though the efficacy is clearly lower than the newer generation GLP-1 RAs like liraglutide, dulaglutide, and semaglutide[33-36]. However, the glycemic effectiveness appears lower than that of the other twincretin drug in the same class (GLP-1RA/glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide receptor agonist)-mazdutide (HbA1c reduction-2.09%), as shown in another network MA[33]. It’s essential to note that the RCTs in this review had a short duration and involved fewer participants, which may have impacted the glycemic outcomes. Our results suggest that the weight loss potential of cotadutide surpasses that of GLP-1RA drugs such as lixisenatide, exenatide, liraglutide, and dulaglutide, as well as twincretin mazdutide, and is comparable to semaglutide (at the highest dose)[33]. While all the published RCTs have included patients with T2D and obesity, there is no evidence specifically examining cotadutide in individuals with obesity without diabetes. However, considering the weight loss potential at par with semaglutide[36], especially at higher doses, cotadutide might be useful even for obese patients without diabetes. This idea, emerging from our review, requires evaluation in future studies. Additionally, the risk of developing sarcopenia due to weight loss from other incretin agonist therapies remains uncertain and should be explored in future cotadutide research[37].

The AEs associated with cotadutide treatment were similar to ACG, indicating that using this drug for managing diabesity is reasonably safe, comparable to other incretin-based therapies. Gastrointestinal AEs were the primary issues faced by the treatment group, as expected. However, additional evidence is necessary to determine how these AEs can be minimized in routine clinical practice, ensuring the proper use of this important drug for treating diabesity. Slow up-titration of dose can be an option for reducing gastrointestinal AEs to improve tolerability, as recommended in the case of other GLP-1RAs[38]. This should be investigated in future RCTs.

Including all available clinical studies, all of which are RCTs (mostly with low RoB), is the main strength of this SR/MA. However, we acknowledge certain limitations. The included RCTs were limited in number, all being early-phase (8 phase 2, 1 phase 1) sponsor-funded studies with small sample sizes. The effect size for many outcomes has wide CIs. A wide range of trial durations (28-378 days), combining short and longer studies, may bias pooled estimates. The heterogeneity observed for most outcomes is moderate to high, and the potential sources of this heterogeneity were not explored, which undermines the reliability of the polled estimates. The certainty of evidence for the primary outcome was very low to low, raising questions about the applicability of the results to clinical practice. Lack of wide ethnic and geographic diversity in the studied populations is also crucial. Moreover, for a very common and lifelong ailment like diabetes and obesity, the duration of treatment or follow-up is limited. Cardiovascular outcomes and other metabolic or physical outcomes, such as improvements in hepatic steatosis, sleep apnea, osteoarthritis, and neurocognitive outcomes, were not evaluated in the included RCTs, similar to recent major studies with newer antidiabetic agents. These limitations should be properly addressed in future large multinational RCTs with cotadutide to establish this as a promising drug molecule for managing diabetes and obesity.

Based on short-term, early-phase, small-scale RCTs with moderate to low RoB, cotadutide demonstrated modest improvements in glycemic control and weight reduction. However, treatment was associated with a higher incidence of gastrointestinal AEs, indicating some tolerability concerns. Furthermore, the existing evidence, rated as very low to low certainty, further underestimates its therapeutic potential as an antidiabetic medication. More extensive, long-term multinational RCTs are necessary to better understand the cardiometabolic benefits, safety profile, and long-term outcomes of cotadutide. This will help inform clinical practices and improve its use in managing diabetes and obesity.

We thank Dr. Marina George Kudiyirickal BDS, MJDF (RCS), MSc, PhD for the help in creating the audio core tip of this paper.

| 1. | Arredouani A. GLP-1 receptor agonists, are we witnessing the emergence of a paradigm shift for neuro-cardio-metabolic disorders? Pharmacol Ther. 2025;269:108824. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Enyew Belay K, Jemal RH, Tuyizere A. Innovative Glucagon-based Therapies for Obesity. J Endocr Soc. 2024;8:bvae197. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Jiang Y, Zhu H, Gong F. Why does GLP-1 agonist combined with GIP and/or GCG agonist have greater weight loss effect than GLP-1 agonist alone in obese adults without type 2 diabetes? Diabetes Obes Metab. 2025;27:1079-1095. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Henderson SJ, Konkar A, Hornigold DC, Trevaskis JL, Jackson R, Fritsch Fredin M, Jansson-Löfmark R, Naylor J, Rossi A, Bednarek MA, Bhagroo N, Salari H, Will S, Oldham S, Hansen G, Feigh M, Klein T, Grimsby J, Maguire S, Jermutus L, Rondinone CM, Coghlan MP. Robust anti-obesity and metabolic effects of a dual GLP-1/glucagon receptor peptide agonist in rodents and non-human primates. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2016;18:1176-1190. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 154] [Cited by in RCA: 206] [Article Influence: 20.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Stachteas P, Nasoufidou A, Karakasis P, Koiliari M, Karagiannidis E, Koufakis T, Fragakis N, Patoulias D. Efficacy of Dual Glucagon and Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists Across the Cardiometabolic Continuum: A Review of Current Clinical Evidence. Rev Cardiovasc Med. 2025;26:39691. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Zaffina I, Pelle MC, Armentaro G, Giofrè F, Cassano V, Sciacqua A, Arturi F. Effect of dual glucose-dependent insulinotropic peptide/glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist on weight loss in subjects with obesity. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023;14:1095753. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Boland ML, Laker RC, Mather K, Nawrocki A, Oldham S, Boland BB, Lewis H, Conway J, Naylor J, Guionaud S, Feigh M, Veidal SS, Lantier L, McGuinness OP, Grimsby J, Rondinone CM, Jermutus L, Larsen MR, Trevaskis JL, Rhodes CJ. Resolution of NASH and hepatic fibrosis by the GLP-1R/GcgR dual-agonist Cotadutide via modulating mitochondrial function and lipogenesis. Nat Metab. 2020;2:413-431. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 207] [Article Influence: 34.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ambery P, Parker VE, Stumvoll M, Posch MG, Heise T, Plum-Moerschel L, Tsai LF, Robertson D, Jain M, Petrone M, Rondinone C, Hirshberg B, Jermutus L. MEDI0382, a GLP-1 and glucagon receptor dual agonist, in obese or overweight patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomised, controlled, double-blind, ascending dose and phase 2a study. Lancet. 2018;391:2607-2618. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 185] [Cited by in RCA: 234] [Article Influence: 29.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Asano M, Sekikawa A, Kim H, Gasser RA Jr, Robertson D, Petrone M, Jermutus L, Ambery P. Pharmacokinetics, safety, tolerability and efficacy of cotadutide, a glucagon-like peptide-1 and glucagon receptor dual agonist, in phase 1 and 2 trials in overweight or obese participants of Asian descent with or without type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2021;23:1859-1867. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Asano M, Sekikawa A, Sugeno M, Matsuoka O, Robertson D, Hansen L. Safety/tolerability, efficacy and pharmacokinetics of 600-μg cotadutide in Japanese type 2 diabetes patients with a body mass index of 25 kg/m(2) or higher: A phase I, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2023;25:2290-2299. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Golubic R, Kennet J, Parker V, Robertson D, Luo D, Hansen L, Jermutus L, Ambery P, Ryaboshapkina M, Surakala M, Laker RC, Venables M, Koulman A, Park A, Evans M. Dual glucagon-like peptide-1 and glucagon receptor agonism reduces energy intake in type 2 diabetes with obesity. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2024;26:2634-2644. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Nahra R, Wang T, Gadde KM, Oscarsson J, Stumvoll M, Jermutus L, Hirshberg B, Ambery P. Effects of Cotadutide on Metabolic and Hepatic Parameters in Adults With Overweight or Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes: A 54-Week Randomized Phase 2b Study. Diabetes Care. 2021;44:1433-1442. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 231] [Article Influence: 46.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Parker VER, Robertson D, Wang T, Hornigold DC, Petrone M, Cooper AT, Posch MG, Heise T, Plum-Moerschel L, Schlichthaar H, Klaus B, Ambery PD, Meier JJ, Hirshberg B. Efficacy, Safety, and Mechanistic Insights of Cotadutide, a Dual Receptor Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 and Glucagon Agonist. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020;105:dgz047. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 14.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Parker VER, Hoang T, Schlichthaar H, Gibb FW, Wenzel B, Posch MG, Rose L, Chang YT, Petrone M, Hansen L, Ambery P, Jermutus L, Heerspink HJL, McCrimmon RJ. Efficacy and safety of cotadutide, a dual glucagon-like peptide-1 and glucagon receptor agonist, in a randomized phase 2a study of patients with type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2022;24:1360-1369. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 13.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Parker VER, Robertson D, Erazo-Tapia E, Havekes B, Phielix E, de Ligt M, Roumans KHM, Mevenkamp J, Sjoberg F, Schrauwen-Hinderling VB, Johansson E, Chang YT, Esterline R, Smith K, Wilkinson DJ, Hansen L, Johansson L, Ambery P, Jermutus L, Schrauwen P. Cotadutide promotes glycogenolysis in people with overweight or obesity diagnosed with type 2 diabetes. Nat Metab. 2023;5:2086-2093. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Selvarajah V, Robertson D, Hansen L, Jermutus L, Smith K, Coggi A, Sánchez J, Chang YT, Yu H, Parkinson J, Khan A, Chung HS, Hess S, Dumas R, Duck T, Jolly S, Elliott TG, Baker J, Lecube A, Derwahl KM, Scott R, Morales C, Peters C, Goldenberg R, Parker VER, Heerspink HJL; study investigators. A randomized phase 2b trial examined the effects of the glucagon-like peptide-1 and glucagon receptor agonist cotadutide on kidney outcomes in patients with diabetic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2024;106:1170-1180. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Ali MM, Hafez A, Abdelgalil MS, Hasan MT, El-Ghannam MM, Ghogar OM, Elrashedy AA, Abd-ElGawad M. Impact of Cotadutide drug on patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Endocr Disord. 2022;22:113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | De Block CEM, Dirinck E, Verhaegen A, Van Gaal LF. Efficacy and safety of high-dose glucagon-like peptide-1, glucagon-like peptide-1/glucose-dependent insulinotropic peptide, and glucagon-like peptide-1/glucagon receptor agonists in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2022;24:788-805. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. 2nd Edition. Chichester (UK): John Wiley & Sons, 2019. |

| 20. | Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hróbjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S, McGuinness LA, Stewart LA, Thomas J, Tricco AC, Welch VA, Whiting P, Moher D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44932] [Cited by in RCA: 50781] [Article Influence: 10156.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 21. | Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, Elbers RG, Blencowe NS, Boutron I, Cates CJ, Cheng HY, Corbett MS, Eldridge SM, Emberson JR, Hernán MA, Hopewell S, Hróbjartsson A, Junqueira DR, Jüni P, Kirkham JJ, Lasserson T, Li T, McAleenan A, Reeves BC, Shepperd S, Shrier I, Stewart LA, Tilling K, White IR, Whiting PF, Higgins JPT. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2019;366:l4898. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6581] [Cited by in RCA: 18532] [Article Influence: 2647.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | McGuinness LA, Higgins JPT. Risk-of-bias VISualization (robvis): An R package and Shiny web app for visualizing risk-of-bias assessments. Res Synth Methods. 2021;12:55-61. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 613] [Cited by in RCA: 3231] [Article Influence: 538.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | RevMan: Systematic review and meta-analysis tool for researchers worldwide. The Cochrane Collaboration. [cited 30 June 2025]. Available from: https://revman.cochrane.org/info. |

| 24. | Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557-560. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39087] [Cited by in RCA: 48459] [Article Influence: 2106.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 25. | Guyatt G, Oxman AD, Akl EA, Kunz R, Vist G, Brozek J, Norris S, Falck-Ytter Y, Glasziou P, DeBeer H, Jaeschke R, Rind D, Meerpohl J, Dahm P, Schünemann HJ. GRADE guidelines: 1. Introduction-GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64:383-394. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4813] [Cited by in RCA: 7714] [Article Influence: 482.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Kamrul-Hasan ABM, Alam MS, Talukder SK, Dutta D, Selim S. Efficacy and Safety of Omarigliptin, a Novel Once-Weekly Dipeptidyl Peptidase-4 Inhibitor, in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Endocrinol Metab (Seoul). 2024;39:109-126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Ambery PD, Klammt S, Posch MG, Petrone M, Pu W, Rondinone C, Jermutus L, Hirshberg B. MEDI0382, a GLP-1/glucagon receptor dual agonist, meets safety and tolerability endpoints in a single-dose, healthy-subject, randomized, Phase 1 study. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2018;84:2325-2335. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Bosch R, Petrone M, Arends R, Vicini P, Sijbrands EJG, Hoefman S, Snelder N. Characterisation of cotadutide's dual GLP-1/glucagon receptor agonistic effects on glycaemic control using an in vivo human glucose regulation quantitative systems pharmacology model. Br J Pharmacol. 2024;181:1874-1885. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Klein G, Petrone M, Yang Y, Hoang T, Hazlett S, Hansen L, Flor A. Pharmacokinetics and Safety of Cotadutide, a GLP-1 and Glucagon Receptor Dual Agonist, in Individuals with Renal Impairment: A Single-Dose, Phase I, Bridging Study. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2023;62:881-890. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Shankar SS, Daniels SJ, Robertson D, Sarv J, Sánchez J, Carter D, Jermutus L, Challis B, Sanyal AJ. Safety and Efficacy of Novel Incretin Co-agonist Cotadutide in Biopsy-proven Noncirrhotic MASH With Fibrosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024;22:1847-1857.e11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Yu H, Parker V, Selvarajah V, Hansen L, Robertson D, Hamrén B, Khan A, Parkinson J. Pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) modelling of cotadutide effect in patients with chronic kidney disease and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2025;91:2672-2683. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Song F, Eastwood AJ, Gilbody S, Duley L, Sutton AJ. Publication and related biases. Health Technol Assess. 2000;4:1-115. [PubMed] |

| 33. | Yao H, Zhang A, Li D, Wu Y, Wang CZ, Wan JY, Yuan CS. Comparative effectiveness of GLP-1 receptor agonists on glycaemic control, body weight, and lipid profile for type 2 diabetes: systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMJ. 2024;384:e076410. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 268] [Reference Citation Analysis (12)] |

| 34. | Xie Z, Hu J, Gu H, Li M, Chen J. Comparison of the efficacy and safety of 10 glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists as add-on to metformin in patients with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023;14:1244432. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Wen Z, Sun W, Wang H, Chang R, Wang J, Song C, Zhang S, Ni Q, An X. Comparison of the effectiveness and safety of GLP-1 receptor agonists for type 2 diabetes mellitus patients with overweight/obesity: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2025;222:111999. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Guo X, Zhou Z, Lyu X, Xu H, Zhu H, Pan H, Wang L, Yang H, Gong F. The Antiobesity Effect and Safety of GLP-1 Receptor Agonist in Overweight/Obese Patients Without Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Horm Metab Res. 2022;54:458-471. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Karakasis P, Patoulias D, Fragakis N, Mantzoros CS. Effect of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists and co-agonists on body composition: Systematic review and network meta-analysis. Metabolism. 2025;164:156113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 74.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Gorgojo-Martínez JJ, Mezquita-Raya P, Carretero-Gómez J, Castro A, Cebrián-Cuenca A, de Torres-Sánchez A, García-de-Lucas MD, Núñez J, Obaya JC, Soler MJ, Górriz JL, Rubio-Herrera MÁ. Clinical Recommendations to Manage Gastrointestinal Adverse Events in Patients Treated with Glp-1 Receptor Agonists: A Multidisciplinary Expert Consensus. J Clin Med. 2022;12:145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 188] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/