Published online Feb 15, 2026. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v18.i2.115199

Revised: November 22, 2025

Accepted: December 11, 2025

Published online: February 15, 2026

Processing time: 108 Days and 22 Hours

Surgical resection is the core treatment for localized gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumors (LGISTs). Advances in minimally invasive techniques have led to the use of both endoscopic and laparoscopic resections; however, there is con

To systematically compare the perioperative outcomes and mid-term oncological efficacy of endoscopic vs laparoscopic resection for LGISTs, and provide an evidence-based reference for clinical surgical approach selection.

Patients with LGIST who underwent surgery in our hospital between January 2023 and January 2024 were retrospectively enrolled. After 1:1 propensity score matching, 45 patients who received endoscopic resection were assigned to the endoscopic group, and 45 patients who underwent laparoscopic resection were included in the laparoscopic group. Intraoperative indicators (such as operation time, blood loss, R0 resection rate), postoperative recovery indicators (including hospital stay, time to first flatus), complication rate, and mid-term oncological outcomes [1-year/3-year recurrence-free survival (RFS), overall survival (OS)] were compared between the two groups. Multivariate Cox regression was used to identify prognostic factors.

After matching, the baseline data of the two groups were comparable (P > 0.05). The endoscopic group was superior to the laparoscopic group in terms of ope

In carefully selected LGIST cases, endoscopic resection achieves comparable mid-term oncological efficacy to that of laparoscopic resection, while offering the advantages of shorter operation time, less blood loss, and faster postoperative recovery. It can therefore be a minimally invasive treatment option for eligible patients, with surgical decision-making based on tumor characteristics and multidisciplinary assessments.

Core Tip: This study compared the efficacy of endoscopic and laparoscopic resection for localized gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumors (LGISTs) using propensity score matching to control for baseline bias. Endoscopic resection was found to be superior in terms of reduced operation time, blood loss, and postoperative hospital stay, while achieving comparable mid-term oncological outcomes (3-year recurrence-free survival and overall survival) to laparoscopic resection. Tumor size, mitotic count, and National Institutes of Health risk stratification were key factors affecting prognosis, and the surgical approach had no direct influence on recurrence risk. The study provides evidence-based support for “prioritizing minimally invasive endoscopic treatment for carefully selected LGIST patients”.

- Citation: Huang L, Li JT, Zhou WJ, Wu QF. Endoscopic vs laparoscopic resection for gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumors: Oncological outcomes. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2026; 18(2): 115199

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v18/i2/115199.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v18.i2.115199

Gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST), the most common mesenchymal tumor of the gastrointestinal tract, occurs most frequently in the stomach (50%-63%) and small intestine (29%-35%)[1-3]. Most GISTs are sporadic and, apart from several rare tumor syndromes, no risk factors have been identified[4]. The clinical manifestations of GIST vary. Some patients are asymptomatic, leading to incidental detection of the tumor during abdominal imaging examinations, surgeries for un

Localized GIST (LGIST) is the most common form of GIST seen on initial presentation. These tumors are confined to the wall of the primary gastrointestinal tract with possible restricted invasion of adjacent tissues (e.g., perigastric fat, small intestinal mesentery), with no distant metastasis (such as liver or lung metastasis), peritoneal seeding, or major vascular invasion. This GIST subtype responds better to treatment and is associated with a more favorable prognosis. While surgical resection remains the mainstay of LGIST treatment, the optimal surgical approach is disputed and is currently a focus of clinical research. The development of minimally invasive techniques has expanded the surgical options from traditional open surgery to laparoscopic and endoscopic resection. Surgical resection for LGISTs with tumor diameters > 2 cm is recommended in guidelines worldwide[10,11]. Among these approaches, laparoscopic surgery represents a standard minimally invasive procedure for tumors < 5 cm in diameter located at “favorable sites”, such as the anterior gastric wall and greater curvature. In addition, endoscopic techniques, including endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) and endoscopic full-thickness resection (EFTR), have demonstrated significant potential in treating small GISTs (especially those ≤ 2 cm) due to their unique advantages of using natural orifices for insertion, thereby avoiding trauma to the abdominal wall. These advantages have led to increased acceptance and application of these techniques[12]. However, the use of endoscopic techniques in the treatment of large-diameter LGISTs (e.g., 2-5 cm) remains highly controversial. The core of the controversy lies in whether endoscopic resection can achieve oncological radicality (R0 resection rate) and long-term recurrence-free survival (RFS) rates equivalent to those of laparoscopic surgery for larger and more complex tumors, as well as their ability to control the risks of intraoperative perforation and tumor rupture[13]. More

This single-center, retrospective study consecutively enrolled patients with LGIST who had undergone surgical treatment at JiuJiang No. 1 People’s Hospital, Jiujiang City Key Laboratory of Cell Therapy Hospital between January 1, 2023, and January 1, 2024. Patients were divided into the endoscopic resection (ESD/EFTR) and laparoscopic surgery groups based on the surgical procedure performed.

Inclusion criteria: (1) Definitive diagnosis of primary gastric GIST confirmed by postoperative pathological analysis of paraffin sections or preoperative endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy (confirmed by postoperative pathology), with positive immunohistochemical staining for CD117 and/or DOG1; (2) Preoperative imaging and EUS assessments consistent with American Joint Committee on Cancer T1-T2 staging, tumor diameter of 1.0-10.0 cm, distance from the cardia or pylorus of ≥ 3.0 cm, and originating from the submucosa or superficial muscularis propria of the gastric wall; (3) Pathological risk stratification of very low, low, or intermediate risk according to the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines, based on tumor size and mitotic count (in 50 HPFs); (4) Underwent pure endoscopic resection (ESD/endoscopic submucosal excavation) or local laparoscopic resection, with no combination of the two procedures; (5) Preoperative American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status classification of I-II, with no severe cardiopulmonary, hepatic, or renal dysfunction, coagulation disorders, or other surgical contraindications; and (6) Complete records of postoperative 30-day complications and 1-year/3-year recurrence during follow-up available in the medical records system or follow-up registry.

Exclusion criteria: (1) Presence of distant metastasis, invasion of adjacent organs, or serosal penetration; tumor diameter < 1.0 cm/> 10.0 cm, or distance from the cardia/pylorus < 3.0 cm; (2) Previous treatment with targeted agents (e.g., imatinib), argon plasma coagulation (APC), radiofrequency ablation, or other therapies before surgery; (3) History of abdominal surgery, or the presence of multiple gastric GISTs; (4) Comorbidity with other types of malignant tumor (including past history), ASA class III-IV diseases, acute infections, or psychiatric disorders potentially influencing recovery or follow-up; (5) Absence of key data in the medical records, follow-up duration < 1 year, or incomplete in

Ultimately, a total of 103 patients meeting the inclusion and exclusion criteria were enrolled in the analysis.

All patients were evaluated before surgery by a multidisciplinary team (MDT) consisting of gastrointestinal surgeons, gastroenterologists, oncologists, and radiologists. The surgical plan was determined collectively based on the tumor size, location (distance from the cardia/pylorus), growth pattern (intraluminal/exophytic), and estimated surgical risk.

Preoperative preparation: Routine preoperative preparation was undertaken for both groups: (1) Fasting for 12 hours and nil by mouth for 4 hours before surgery; (2) Patients undergoing EFTR or laparoscopic surgery received bowel preparation by oral administration of polyethylene glycol electrolyte powder one day before surgery; (3) Antiplatelet and anticoagulant drugs were discontinued seven days before surgery, while low-molecular-weight heparin bridging therapy and low-molecular-weight heparin were stopped 12 hours before surgery; (4) Prophylactic second-generation ce

Surgical procedures in the endoscopic group: The surgical approach was selected based on EUS findings.

The use of ESD was indicated for tumors that showed predominantly intraluminal growth with no tight adhesion to the serosa. The key steps were as follows: (1) A mixed solution (glycerin fructose-indigo carmine-epinephrine) was administered submucosally to create a submucosal cushion with a lifting sign height ≥ 5 mm; (2) A circumferential mucosal incision was made 5 mm from the edge of the lesion after marking; (3) The submucosal layer was dissected for complete resection of the tumor, avoiding damage to the muscularis propria; and (4) Hemostasis of visible vessel stumps on the wound surface was performed using hot biopsy forceps or APC.

The use of EFTR was indicated for tumors with transmural growth or tight adhesion to the serosa. The key steps were as follows: (1) The submucosal injection and marking steps were performed as described for ESD above; (2) After circumferential mucosal incision, dissection was continued until the creation of an intentionally controlled perforation (diameter ≤ 2 cm) of the serosa, enabling complete full-thickness resection of the tumor; and (3) The wound was closed with endoclips and nylon loops using the “purse-string suture” technique to ensure no air leakage.

The surgical team involved in this study had extensive experience in minimally invasive endoscopic surgery. Each surgeon performed more than 150 ESD/EFTR procedures annually, including over 50 cases of gastric GIST resection. The center conducts approximately 120-150 endoscopic resections for gastric GIST each year, with a technical success rate of over 95% for complex cases (such as tumors in unfavorable locations or with transmural growth).

Surgical procedures in the laparoscopic group: Patients were placed in a supine position, and general anesthesia was administered, followed by establishment of a CO2 pneumoperitoneum (intra-abdominal pressure maintained at 12 mmHg). A standard five-port technique was used (a 10 mm umbilical observation port, and four 5 mm working ports at other sites). After exploration of the abdomen to confirm the location of the tumor and its relationship with surrounding blood vessels, the surgical approach was selected based on the tumor size and location: (1) For tumors < 5 cm in diameter located in the gastric body or fundus, local laparoscopic resection was performed, in which the gastric wall was incised 1 cm from the tumor edge using an ultrasonic scalpel, after which the tumor was completely resected before layered suturing of the gastric wall; and (2) For tumors ≥ 5 cm in diameter or located in the gastric antrum, laparoscopic wedge resection was performed. This involved the use of a linear cutting stapler to transect the gastric wall and tumor 1 cm from the tumor edge, ensuring a margin of ≥ 1 cm from the tumor edge. All resected tissue was placed in a retrieval bag and extracted through an enlarged trocar site. R0 resection was the primary goal for all surgeries.

Postoperative management: All patients received perioperative care based on the enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocol. This involved: (1) Early postoperative mobilization (bedside activity at 6 h postoperatively, ambulation at 24 hours postoperatively); (2) Initiation of a liquid diet 24 hours (endoscopic group) or 48 hours (laparoscopic group) after surgery, with a gradual transition to a semi-liquid and soft diet; and (3) Pain assessment using the visual analog scale (VAS); patients with a VAS score ≥ 4 received intravenous flurbiprofen axetil for analgesia.

Postoperative evaluation and adjuvant therapy: (1) Assessment of complications: Complications [bleeding (hema

Assessments by the MDT were conducted based on the results of the postoperative NIH risk stratification and molecular testing. All high-risk patients received adjuvant therapy with imatinib mesylate. Treatment dosage and duration were adjusted according to the type of gene mutation: A dosage of 400 mg/day for at least three years was recommended for patients with mutations in exon 11 of c-KIT, while an initial dosage of 600-800 mg/day was used for those with mutations in exon 9. Patients with the D842V mutation in PDGFRA, who are inherently resistant to imatinib, were not recommended for adjuvant imatinib therapy. All treatment recommendations were implemented after full communication with the patients and their families.

Demographic and clinical data included information on sex, age, body mass index (BMI), initial symptoms, preoperative comorbidities, tumor size, mitotic count, tumor location, growth pattern, and cytological morphology. Tumor location was categorized into “favorable sites” (including the gastric fundus, anterior wall of the gastric body, and greater curvature) and “unfavorable sites” (including the esophagogastric junction, lesser curvature of the gastric body, posterior wall of the gastric body, gastric antrum, and pylorus) according to the NCCN guidelines and relevant literature. Tumor growth patterns were classified as “intraluminal” (main body of the tumor protruding into the gastric lumen) or “exophytic” (main body of the tumor protruding outside the gastric lumen) based on preoperative imaging and EUS assessments.

Intraoperative outcomes: These included the operation time, intraoperative blood loss (estimated by suction volume + gauze blood absorption in the endoscopic group, and by the difference between the irrigation fluid volume and suction fluid volume + gauze blood absorption in the laparoscopic group), R0 resection rate, rate of intraoperative tumor rupture, and rate of conversion to open surgery (laparoscopic group).

Postoperative recovery outcomes included the time to first flatus, time to first oral intake of liquid, time to ambulation, and length of postoperative hospital stay.

Postoperative complications: All complications occurring within 30 days after surgery were recorded, and their severity was graded using the Clavien-Dindo classification system. Focus was placed on the incidence of bleeding, perforation, intra-abdominal infection, and pulmonary infection.

Oncological outcomes represented the 1-year and 3-year rates of RFS and overall survival (OS).

All patients were followed up postoperatively through telephone calls. The follow-up time points were set at 1 months, 3 months, 6 months, 12 months, 18 months, and 24 months after surgery. The information obtained included the patient's survival status, symptoms, and occurrence of complications, all of which were included in the electronic medical record system. Abdominal enhanced computed tomography was performed at 6 months, 12 months, and 24 months postoperatively to assess tumor recurrence. The follow-up period ended on September 1, 2025.

Tumor location: Based on the NCCN guidelines and published research, the gastric anatomical sites were divided into favorable and unfavorable site groups. Tumors included in the favorable site group were those located in the gastric fundus, anterior wall of the gastric body, and greater curvature, while the unfavorable site group comprised tumors located in the esophagogastric junction, lesser curvature of the gastric body, posterior wall of the gastric body, gastric antrum, and pylorus. In the laparoscopic group, 23 cases were included in the favorable site subgroup, with 22 cases in the unfavorable site subgroup, while in the endoscopic group, 23 cases were classified as being in favorable sites and 22 as being located in unfavorable sites.

Tumor growth pattern: Based on the relationship between the main body of the tumor and the gastric wall, tumors were divided into intraluminal and exophytic groups. The laparoscopic group included 23 cases of intraluminal tumors and 22 cases of exophytic tumors, while the endoscopic group contained 25 cases of intraluminal tumors and 20 of exophytic tumors.

Data were analyzed using SPSS 27.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States). Data distributions were analyzed, and data conforming to a normal distribution are presented as mean ± SD and were compared using independent-samples t-tests. Non-normally distributed continuous data are presented as median (interquartile range) and compared using the Mann-Whitney U test. Categorical variables are expressed as n (%), and intergroup comparisons were performed using the χ2 test or Fisher's exact test. To control for selection bias, 1:1 PSM was performed for variables with inconsistencies in baseline characteristics between the two groups, using age, sex, BMI, tumor size, mitotic count, tumor location, growth pattern, and cytological morphology as covariates. Survival rates (OS and RFS) were analyzed using Kaplan-Meier curves, with intergroup comparisons using log-rank tests. The significance level was set at α = 0.05, and a P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

A total of 123 eligible patients were initially screened. After 1:1 PSM, 90 patients were ultimately included in the analysis, with the endoscopic and laparoscopic groups each containing 45 patients. After matching, there were no statistically significant differences between the groups in terms of baseline data (including age, sex, BMI, tumor size, mitotic count, NIH risk stratification, tumor location, and growth pattern, all P > 0.05; Table 1). The significant selection bias present before matching was effectively controlled.

| Variable | Pre-matching | P value | Post-matching | P value | ||

| Endoscopic (n = 50) | Laparoscopic (n = 73) | Endoscopic (n = 45) | Laparoscopic (n = 45) | |||

| Demographic data | ||||||

| Age (years) | 57.9 ± 10.1 | 59.8 ± 9.7 | 0.285 | 58.5 ± 9.8 | 58.9 ± 10.2 | 0.841 |

| Gender (male) | 28 (56.0) | 40 (54.8) | 0.892 | 25 (55.6) | 24 (53.3) | 0.829 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.8 ± 2.9 | 24.3 ± 3.1 | 0.341 | 24.0 ± 2.8 | 24.1 ± 3.0 | 0.867 |

| Tumor characteristics | ||||||

| Tumor size (cm) | 2.8 (2.0-3.8) | 4.3 (3.0-5.8) | < 0.001 | 3.5 (2.6-4.4) | 3.6 (2.7-4.5) | 0.723 |

| Mitotic count (/50 HPF) | 2 (1-4) | 4 (2-6) | 0.003 | 3 (1-5) | 3 (2-5) | 0.435 |

| NIH risk stratification | ||||||

| Very low/low risk | 35 (70.0) | 38 (52.1) | 0.009 | 28 (62.2) | 26 (57.8) | 0.654 |

| Intermediate risk | 15 (30.0) | 35 (47.9) | 17 (37.8) | 19 (42.2) | ||

| Tumor location | ||||||

| Favorable sites | 38 (76.0) | 30 (41.1) | < 0.001 | 23 (51.1) | 23 (51.1) | 1 |

| Unfavorable sites | 12 (24.0) | 43 (58.9) | 22 (48.9) | 22 (48.9) | ||

| Growth pattern | ||||||

| Intraluminal | 35 (70.0) | 35 (47.9) | 0.002 | 25 (55.6) | 23 (51.1) | 0.832 |

| Exophytic | 15 (30.0) | 38 (52.1) | 20 (44.4) | 22 (48.9) | ||

Notably, before matching, patients in the laparoscopic group had significantly larger tumor sizes (4.3 cm vs 2.8 cm, P < 0.001), higher mitotic counts (4/50 HPFs vs 2/50 HPFs, P = 0.003), higher proportions of intermediate-risk tumors (47.9% vs 30.0%, P = 0.009), and higher proportions of tumors located at unfavorable sites (58.9% vs 24.0%, P < 0.001) compared with the endoscopic group. This distribution was consistent with the clinical decision-making logic of surgical approach selection based on the complexity of the tumor.

Surgery was successfully completed in all patients, with no intraoperative deaths. As shown in Table 2, the endoscopic group exhibited significantly superior perioperative outcomes: Shorter operation time (80 minutes vs 95 minutes, P = 0.002), less intraoperative blood loss (25 mL vs 55 mL, P < 0.001), and shorter postoperative hospital stay (5 days vs 7 days, P < 0.001). The rates of R0 resection (97.8% vs 95.6%, P = 0.617) and intraoperative tumor rupture (2.2% vs 4.4%, P = 1.000) were comparable between the two groups. The overall complication rate was lower in the endoscopic group than that in the laparoscopic group (11.1% vs 22.2%), although the difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.152).

| Variable | Endoscopic (n = 45) | Laparoscopic (n = 45) | Test statistic | P value |

| Overall comparison | ||||

| Operation time (minute) | 80 (65-100) | 95 (80-120) | Z = -3.112 | 0.002 |

| Intraoperative blood loss (mL) | 25 (15-35) | 55 (40-90) | Z = -5.421 | < 0.001 |

| R0 resection rate | 43 (95.6) | 44 (97.8) | Fisher | 0.617 |

| Intraoperative tumor rupture | 1 (2.2) | 2 (4.4) | Fisher | 1.000 |

| Postoperative hospital stays (days) | 5 (4-7) | 7 (6-9) | Z = -4.225 | < 0.001 |

| Postoperative complications (Clavien-Dindo ≥ II) | 5 (11.1) | 10 (22.2) | χ2 = 2.051 | 0.152 |

| Subgroup analysis by location | ||||

| Favorable sites | n = 23 | n = 23 | ||

| Operation time (minute) | 75 (60-90) | 85 (70-100) | Z = -2.315 | 0.021 |

| Intraoperative blood loss (mL) | 20 (10-30) | 50 (35-70) | Z = -4.521 | < 0.001 |

| Unfavorable sites | n = 22 | n = 22 | ||

| Operation time (minute) | 90 (75-110) | 110 (95-135) | Z = -2.987 | 0.003 |

| Intraoperative blood loss (mL) | 30 (20-45) | 65 (50-105) | Z = -4.678 | < 0.001 |

| Subgroup analysis by growth pattern | ||||

| Intraluminal | n = 25 | n = 23 | ||

| Operation time (minute) | 70 (55-85) | 90 (75-105) | Z = -3.224 | 0.001 |

| Exophytic | n = 20 | n = 22 | ||

| Operation time (minute) | 95 (80-115) | 100 (85-125) | Z = -0.912 | 0.362 |

The results of the subgroup analysis further revealed the influence of the anatomical characteristics of the tumor on outcomes.

By tumor location: Irrespective of whether the tumor was located in a favorable or unfavorable site, the endoscopic group showed significant advantages in terms of operation time and intraoperative blood loss (both P < 0.05). Notably, surgery at unfavorable sites was associated with a significantly longer operative time and higher blood loss compared to surgery for tumors in favorable sites.

By growth pattern: For intraluminal tumors, the duration of surgery in the endoscopic group was significantly shorter than that in the laparoscopic group (70 minutes vs 90 minutes, P = 0.001), while for exophytic tumors, the operation time did not differ significantly between the two approaches (95 minutes vs 100 minutes, P = 0.362).

No significant difference in the overall complication rate (Clavien-Dindo ≥ grade II) was observed between the endoscopic and laparoscopic groups in the overall matched cohort (11.1% vs 22.2%, P = 0.152). Although a higher incidence of infectious complications (intra-abdominal infection and pulmonary infection) was seen in the laparoscopic group, the intergroup difference was not statistically significant. Among the three perforation cases, two were planned controlled perforations performed during EFTR (1 case in the endoscopic group and 0 cases in the laparoscopic group) that were successfully closed via endoscopic suturing, and one was an unexpected rupture that occurred during ESD (endoscopic group: 0 cases, laparoscopic group: 1 case) and was managed by conservative treatment. All complications were resolved after active intervention, and there were no severe complications of grade IV or above or deaths. Details are shown in Table 3.

| Complication type & management | Total (n = 90) | Endoscopic (n = 45) | Laparoscopic (n = 45) | P value |

| Overall complications (Clavien-Dindo ≥ II) | 15 (16.7) | 5 (11.1) | 10 (22.2) | 0.152 |

| By grade | ||||

| Grade II | 10 (11.1) | 4 (8.9) | 6 (13.3) | 0.506 |

| Grade IIIa | 4 (4.4) | 1 (2.2) | 3 (6.7) | 0.617 |

| Grade IIIb | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.2) | 1.000 |

| Grade IV-V | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | - |

| By type | ||||

| Bleeding - endoscopic hemostasis/transfusion | 6 (6.6) | 2 (4.4) | 4 (8.8) | 0.398 |

| Perforation/fistula - conservative treatment/aspiration drainage | 3 (3.3) | 1 (2.2) | 2 (4.4) | 1.000 |

| Intra-abdominal infection - antibiotics/aspiration drainage | 3 (3.3) | 2 (4.4) | 1 (2.2) | 1.000 |

| Pulmonary infection - antibiotic treatment | 4 (4.4) | 1 (2.2) | 3 (6.7) | 0.617 |

| Others | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.2) | 1.000 |

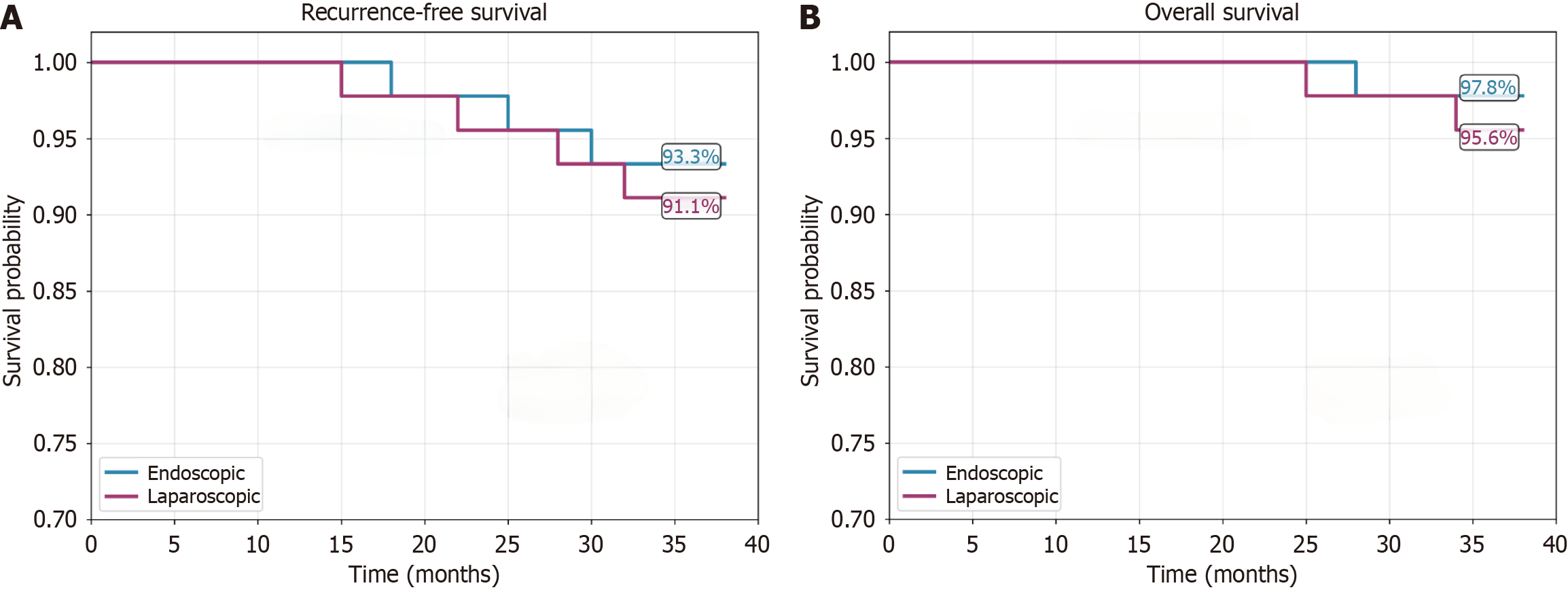

All patients completed follow-up, with a median follow-up duration of 32 months. The 3-year RFS rates were 93.3% in the endoscopic group and 91.1% in the laparoscopic group (P = 0.695), while the 3-year OS rates were 97.8% and 95.6%, respectively (P = 1.000). Seven patients had experienced recurrence by the last follow-up (3 in the endoscopic group and 4 in the laparoscopic group), and 3 patients had died (see Figure 1 and Table 4).

| Survival outcome | Endoscopic (n = 45) | Laparoscopic (n = 45) | Test statistic | P value |

| Median follow-up (months) | 32 (26-38) | 32 (26-38) | - | 0.935 |

| Recurrence events, n (%) | 3 (6.7) | 4 (8.9) | - | 0.695 |

| Death events, n (%) | 1 (2.2) | 2 (4.4) | - | 1.000 |

| RFS rate (%) | ||||

| 1-year | 100 | 100 | χ2 = 0.152 | 0.695 |

| 3-year | 93.3 | 91.1 | ||

| OS rate (%) | ||||

| 1-year | 100 | 100 | χ2 = 0.000 | 0.991 |

| 3-year | 97.8 | 95.6 | ||

To identify independent risk factors for recurrence, multivariate analysis was conducted by including multiple variables in a Cox proportional hazards model. The results showed that tumor size (HR = 1.38, 95%CI: 1.12-1.70, P = 0.002), mitotic count (HR = 1.18, 95%CI: 1.04-1.34, P = 0.010), and NIH risk stratification (intermediate-risk vs low-risk: HR = 5.12, 95%CI: 1.88-13.93, P = 0.001) were independent risk factors for RFS. In contrast, the surgical approach (laparoscopic vs endoscopic) was not an independent prognostic factor (P = 0.558). It should be noted that the conclusion of the surgical approach not being an independent prognostic factor is preliminary due to the small sample (90 cases) and low levels of recurrence (7 cases); larger cohorts and longer follow-up are needed to confirm this. Details are provided in Table 5.

| Variable | HR | 95%CI | P value |

| Surgical approach (laparoscopic vs endoscopic) | 1.32 | 0.52-3.35 | 0.558 |

| Age (per 1-year increase) | 1.01 | 0.96-1.07 | 0.668 |

| Tumor size (per 1-cm increase) | 1.38 | 1.12-1.70 | 0.002 |

| Mitotic count (per 1 increase/50 HPF) | 1.18 | 1.04-1.34 | 0.010 |

| NIH risk stratification (intermediate vs low) | 5.12 | 1.88-13.93 | 0.001 |

| Tumor location (unfavorable vs favorable) | 1.65 | 0.60-4.52 | 0.328 |

GISTs differ fundamentally from gastric adenocarcinomas in terms of their biological behavior. Most LGISTs exhibit expansive growth with an extremely low rate of lymph node metastasis, with their prognosis depending primarily on the type of genetic mutation involved and their NIH risk stratification, rather than on the extent of lymphadenectomy. This characteristic indicates that the core goal of surgery is the achievement of complete resection with negative margins (R0 resection), rather than extensive lymphadenectomy[14]. Therefore, on the premise of ensuring negative margins, endoscopic resection, which is theoretically less invasive, can lead to oncological outcomes comparable to those of laparoscopic surgery. Moreover, endoscopic resection reduces surgical trauma and speeds postoperative recovery due to its advantage of transluminal surgery via natural orifices. There is currently no consensus on the optimal treatment strategy for LGISTs, with controversy surrounding “the selection and applicable scope of minimally invasive surgical ap

However, endoscopic resection has not yet been fully accepted nor routinely applied in clinical practice. On one hand, there is widespread concern about its oncological safety, as, compared with laparoscopic or open surgery, it is more difficult to achieve complete (R0) resection using endoscopy. Incomplete resection can occur due to the limited operating space, especially when the tumor is associated with transmural growth or adhesion to the serosal layer, thereby in

This study comprehensively compared the short- and long-term outcomes of endoscopic and laparoscopic resection for LGISTs. After controlling for baseline differences using PSM, the study systematically compared the perioperative and medium- to long-term oncological outcomes of the two surgical approaches. The principal finding was that for selected LGIST cases, endoscopic resection showed significant advantages, as assessed by perioperative indicators, while achie

In terms of resection completeness, there were cases of incomplete resection in both groups. Zhao et al[19], in a retrospective analysis comparing endoscopic and surgical resection for gastric GISTs with diameters < 5 cm, reported an R1 resection rate in the endoscopic group of 4.7% (4/85). This was presumably related to unclear boundaries between the tumor and muscular layer tissue during endoscopic resection, as well as difficulties in the identification of tumor margins[14,18]. However, R1 resection has been found not to increase the risk of postoperative recurrence[20]. A study showed that endoscopically treated cases in which the tumor margins were difficult to identify due to piecemeal snare resection were more common when using immature early-stage endoscopic techniques, while en bloc resection could be achieved using EFTR[21]. Furthermore, cases of resection failure were observed to involve factors such as increased difficulty of endoscopic resection of exophytic lesions and limited operating space during tunnel resection[22]. It has also been observed that cases of resection failure using laparoscopy were associated with tumors located at sites unfavorable for laparoscopic manipulation[14]. In the present study, after balancing the sample size and baseline data between the two groups via PSM, there was no significant difference in the rate of complete resection between the endoscopic and laparoscopic groups, indicating that despite incomplete resection in a small number of cases in the endoscopic group, the dif

In terms of safety, the primary complications in the endoscopic group were perforation and infection. These complications are associated with increased risks of postoperative perforation and peritonitis due to incomplete closure of intraoperative perforations, prolonged dissection time, and larger wound surfaces. Notably, perforation in the endoscopic group was mostly the result of planned controlled perforations during EFTR, which form an inherent part of the surgical procedure and can be repaired effectively using mature endoscopic closure techniques. In contrast, unexpected perforations occurring during ESD are technical complications that require timely intervention. This distinction indicates that the safety profile of endoscopic resection should be interpreted in terms of the specific surgical technique, and planned controlled perforations should not be equated with unanticipated complications in risk weighting. Shedding of the tumor into the abdominal cavity during endoscopic resection has also been reported; this can be prevented by grasping the lesion with a snare or foreign-body forceps during EFTR[23]. The complications in the laparoscopic group were mainly infection and bleeding, potentially related to surgical trauma and stress[24]. Zhao et al[19] compared 152 cases of gastric GISTs with diameters < 5 cm treated by either endoscopic resection (85 cases) or open surgery (67 cases), and found that the incidence of intraoperative and postoperative complications in the endoscopic group was lower than that in the open-surgery group (5.9% vs 6.4%, P < 0.01), with intraoperative bleeding being the main complication in the latter (63.6%, 7/11). However, the tumor diameters in the endoscopic group were smaller than those in the open-surgery group (2.8 cm vs 4.3 cm, P < 0.05). A meta-analysis including 1165 cases comparing endoscopic and laparoscopic resection for gastric GISTs found that there was no significant difference in the incidence of complications between the two groups; however, the analysis had the problem of inconsistencies in tumor sizes between groups[25]. Zhu et al[26] compared 85 cases of gastric GISTs with diameters of 2-5 cm treated using endoscopic (43 cases) or laparoscopic (42 cases) resection, and observed a significantly higher rate of complications in the endoscopic group compared to the laparoscopic group (35.6% vs 0%, P < 0.01), with all complications in the endoscopic group being intraoperative and postoperative perforation. The discrepancy in complication rates between our study and that of Zhu et al[26] may be attributed to three key factors. First, differences in patient baseline characteristics: Zhu et al[26] included only GISTs located at the esophagogastric junction, which are known to have a high risk for complications, while our study covered a broader range of tumor locations, including fa

In terms of perioperative indicators, the findings of Zhao et al[19] are consistent with those of the present study, showing that the endoscopic group had lower hospitalization costs, earlier resumption of oral feeding, and shorter postoperative hospital stay. The present study further confirmed that for selected patients with gastric GIST, endoscopic resection had significant advantages over laparoscopic resection in terms of perioperative indicators (operation time, intraoperative blood loss, postoperative hospital stays; P < 0.05), and achieved comparable medium-term oncological outcomes. Notably, despite the higher technical difficulty of endoscopic resection, its oncological radicality was not compromised, as seen in the comparable rates of R0 resection and intraoperative tumor rupture between the two groups, confirming that in high-level medical centers, endoscopic techniques also adhere to the principle of tumor-free surgery. After a median follow-up of 32 months, no significant differences were observed in the RFS and OS rates between the two groups, while multivariate Cox analysis confirmed that tumor size, mitotic count, and NIH risk stratification were independent predictors of prognosis, although surgical approach was not predictive. This suggests that after achieving R0 resection, the choice between endoscopic and laparoscopic surgery does not influence the risk of recurrence determined by the inherent biological characteristics of the tumor.

The results of this study have important clinical implications in showing that endoscopic resection represents a feasible alternative to laparoscopic surgery for the treatment of selected patients with gastric GIST. For intermediate- to low-risk tumors ≤ 3 cm in diameter located at favorable sites, such as the gastric fundus and gastric body, endoscopic surgery may be the preferred option due to its minimal invasiveness. For tumors located at unfavorable sites, such as the gastric antrum and cardia, although the subgroup analysis showed that endoscopic resection also had significant advantages, due to the high level of technical difficulty, it should be performed in experienced medical centers after careful evaluation by a MDT. The MDT evaluation should include a comprehensive assessment of the anatomical characteristics of the tumor, the technical feasibility of endoscopic resection, and patient preferences, to maximize benefits.

This study has several limitations. First, it was a single-center retrospective analysis. Although PSM was used to reduce bias, selection bias, and the presence of confounding factors cannot be avoided completely. Second, while the sample size was sufficient to detect differences in perioperative indicators, there was insufficient statistical power to assess low-probability events such as long-term recurrence and survival. This thus represents an important interim report on the mid-term outcomes of endoscopic and laparoscopic resection for LGISTs. While the median follow-up of 32 months provides reliable evidence for short-to-medium-term safety and efficacy, long-term recurrence (e.g., five years or longer) remains to be verified. Our research team is currently conducting an extended follow-up of the cohort, with a planned duration of 5-8 years to confirm the long-term oncological equivalence of the two surgical approaches. For intermediate-risk patients, in particular, prolonged follow-up could clarify whether endoscopic resection can maintain comparable RFS rates to those of laparoscopic resection beyond three years. Longer follow-up times and larger sample sizes may be needed to confirm the long-term oncological equivalence of the two surgical approaches. Third, endoscopic surgery is associated with a steep learning curve, and the results of this study may therefore reflect outcomes obtainable at high-level medical centers, requiring verification of generalizability in a wider range of institutions. In the future, multicenter, prospective, randomized controlled trials are needed to provide higher-level evidence. In addition, longer follow-up (five years or more) is crucial for evaluating the long-term efficacy of the two surgical approaches. Preoperative imaging radiomics models based on artificial intelligence may provide greater accuracy in predicting tumor behavior, thereby providing support for the individualized selection of the optimal surgical approach.

The results of this study indicate that endoscopic resection is a safe and effective minimally invasive option for the treatment of carefully selected patients with LGISTs. While preserving the oncological efficacy of laparoscopic surgery, endoscopic resection offers significant advantages in reducing surgical trauma and accelerating patient recovery. The selection of surgical approach should be individualized, based on the anatomical characteristics of the tumor, MDT assessment, and the condition of the patient, rather than simply following traditional practices. The findings of this study support the application of endoscopic techniques to the treatment of gastric GISTs.

| 1. | Li GZ, Raut CP. Targeted therapy and personalized medicine in gastrointestinal stromal tumors: drug resistance, mechanisms, and treatment strategies. Onco Targets Ther. 2019;12:5123-5133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Giudice F, Salerno S, Badalamenti G, Muto G, Pinto A, Galia M, Prinzi F, Vitabile S, Lo Re G. Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors: Diagnosis, Follow-up and Role of Radiomics in a Single Center Experience. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 2023;44:194-204. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Cheng BQ, Du C, Li HK, Chai NL, Linghu EQ. Endoscopic resection of gastrointestinal stromal tumors. J Dig Dis. 2024;25:550-558. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Serrano C, Martín-Broto J, Asencio-Pascual JM, López-Guerrero JA, Rubió-Casadevall J, Bagué S, García-Del-Muro X, Fernández-Hernández JÁ, Herrero L, López-Pousa A, Poveda A, Martínez-Marín V. 2023 GEIS Guidelines for gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2023;15:17588359231192388. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 28.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Joensuu H. KIT and PDGFRA Variants and the Survival of Patients with Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumor Treated with Adjuvant Imatinib. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15:3879. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Strauss G, George S. Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors. Curr Oncol Rep. 2025;27:312-321. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | Sun Y, Yue L, Xu P, Hu W. An overview of agents and treatments for PDGFRA-mutated gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Front Oncol. 2022;12:927587. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Rajravelu RK, Ginsberg GG. Management of gastric GI stromal tumors: getting the GIST of it. Gastrointest Endosc. 2020;91:823-825. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Keun Park C, Lee EJ, Kim M, Lim HY, Choi DI, Noh JH, Sohn TS, Kim S, Kim MJ, Lee HK, Kim KM. Prognostic stratification of high-risk gastrointestinal stromal tumors in the era of targeted therapy. Ann Surg. 2008;247:1011-1018. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Casali PG, Abecassis N, Aro HT, Bauer S, Biagini R, Bielack S, Bonvalot S, Boukovinas I, Bovee JVMG, Brodowicz T, Broto JM, Buonadonna A, De Álava E, Dei Tos AP, Del Muro XG, Dileo P, Eriksson M, Fedenko A, Ferraresi V, Ferrari A, Ferrari S, Frezza AM, Gasperoni S, Gelderblom H, Gil T, Grignani G, Gronchi A, Haas RL, Hassan B, Hohenberger P, Issels R, Joensuu H, Jones RL, Judson I, Jutte P, Kaal S, Kasper B, Kopeckova K, Krákorová DA, Le Cesne A, Lugowska I, Merimsky O, Montemurro M, Pantaleo MA, Piana R, Picci P, Piperno-Neumann S, Pousa AL, Reichardt P, Robinson MH, Rutkowski P, Safwat AA, Schöffski P, Sleijfer S, Stacchiotti S, Sundby Hall K, Unk M, Van Coevorden F, van der Graaf WTA, Whelan J, Wardelmann E, Zaikova O, Blay JY; ESMO Guidelines Committee and EURACAN. Gastrointestinal stromal tumours: ESMO-EURACAN Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2018;29:iv68-iv78. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 270] [Cited by in RCA: 297] [Article Influence: 37.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 11. | von Mehren M, Kane JM, Agulnik M, Bui MM, Carr-Ascher J, Choy E, Connelly M, Dry S, Ganjoo KN, Gonzalez RJ, Holder A, Homsi J, Keedy V, Kelly CM, Kim E, Liebner D, McCarter M, McGarry SV, Mesko NW, Meyer C, Pappo AS, Parkes AM, Petersen IA, Pollack SM, Poppe M, Riedel RF, Schuetze S, Shabason J, Sicklick JK, Spraker MB, Zimel M, Hang LE, Sundar H, Bergman MA. Soft Tissue Sarcoma, Version 2.2022, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2022;20:815-833. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 245] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Li J, Ye Y, Wang J, Zhang B, Qin S, Shi Y, He Y, Liang X, Liu X, Zhou Y, Wu X, Zhang X, Wang M, Gao Z, Lin T, Cao H, Shen L; Chinese Society Of Clinical Oncology Csco Expert Committee On Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumor. Chinese consensus guidelines for diagnosis and management of gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Chin J Cancer Res. 2017;29:281-293. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 142] [Cited by in RCA: 148] [Article Influence: 16.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 13. | An W, Sun PB, Gao J, Jiang F, Liu F, Chen J, Wang D, Li ZS, Shi XG. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a retrospective cohort study. Surg Endosc. 2017;31:4522-4531. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Ajani JA, D'Amico TA, Bentrem DJ, Corvera CU, Das P, Enzinger PC, Enzler T, Gerdes H, Gibson MK, Grierson P, Gupta G, Hofstetter WL, Ilson DH, Jalal S, Kim S, Kleinberg LR, Klempner S, Lacy J, Lee B, Licciardi F, Lloyd S, Ly QP, Matsukuma K, McNamara M, Merkow RP, Miller AM, Mukherjee S, Mulcahy MF, Perry KA, Pimiento JM, Reddi DM, Reznik S, Roses RE, Strong VE, Su S, Uboha N, Wainberg ZA, Willett CG, Woo Y, Yoon HH, McMillian NR, Stein M. Gastric Cancer, Version 2.2025, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines In Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2025;23:169-191. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | von Mehren M, Kane JM, Riedel RF, Sicklick JK, Pollack SM, Agulnik M, Bui MM, Carr-Ascher J, Choy E, Connelly M, Dry S, Ganjoo KN, Gonzalez RJ, Holder A, Homsi J, Keedy V, Kelly CM, Kim E, Liebner D, McCarter M, McGarry SV, Mesko NW, Meyer C, Pappo AS, Parkes AM, Petersen IA, Poppe M, Schuetze S, Shabason J, Spraker MB, Zimel M, Bergman MA, Sundar H, Hang LE. NCCN Guidelines® Insights: Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors, Version 2.2022. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2022;20:1204-1214. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 21.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Abdalla TSA, Pieper L, Kist M, Thomaschewski M, Klinkhammer-Schalke M, Zeissig SR, Tol KK, Wellner UF, Keck T, Hummel R. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors of the upper GI tract: population-based analysis of epidemiology, treatment and outcome based on data from the German Clinical Cancer Registry Group. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2023;149:7461-7469. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Romandini D, Sobczuk P, Cicala CM, Serrano C. Next questions on gastrointestinal stromal tumors: unresolved challenges and future directions. Curr Opin Oncol. 2025;37:358-364. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Dai Y, Feng Q, Huang J. Is endoscopic resection better than laparoscopic resection for gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumors? J Gastrointest Oncol. 2023;14:1894-1895. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Zhao Y, Pang T, Zhang B, Wang L, Lv Y, Ling T, Zhang X, Huang Q, Xu G, Zou X. Retrospective Comparison of Endoscopic Full-Thickness Versus Laparoscopic or Surgical Resection of Small (≤ 5 cm) Gastric Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors. J Gastrointest Surg. 2020;24:2714-2721. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Liu YB, Liu XY, Fang Y, Chen TY, Hu JW, Chen WF, Li QL, Cai MY, Qin WZ, Xu XY, Wu L, Zhang YQ, Zhou PH. Comparison of safety and short-term outcomes between endoscopic and laparoscopic resections of gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumors with a diameter of 2-5 cm. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;37:1333-1341. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Guo HM, Sun Y, Cai S, Miao F, Zheng Y, Yu Y, Zhao ZF, Liu L. A novel technique for endoscope progression in gastroscopy resection: forward-return way for dissection of stromal tumor in the muscularis propria of the gastric fundus. Front Oncol. 2023;13:1077201. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kim SH. Recent Advances in Endoscopic Treatment Techniques for Subepithelial Lesions. Korean J Helicobacter Up Gastrointest Res. 2025;25:216-223. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Zhu L, Khan S, Hui Y, Zhao J, Li B, Ma S, Guo J, Chen X, Wang B. Treatment recommendations for small gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumors: positive endoscopic resection. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2019;54:297-302. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Rhodin KE, DeLaura IF, Horne E, Bartholomew A, Howell TC, Kanu E, Masoud S, Lidsky ME, Nussbaum DP, Blazer DG 3rd. Impact of Tumor Size and Management on Survival in Small Gastric Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors. J Gastrointest Surg. 2023;27:2076-2084. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Zhu H, Zhao S, Jiao R, Zhou J, Zhang C, Miao L. Comparison of endoscopic versus laparoscopic resection for gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumors: A preliminary meta-analysis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;35:1858-1868. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Zhu S, Liu Z, Zhang J, Dai N, Ullah S, Zhang G, Zhang S, Liu P, Fu Y, Zheng S, Zhou Z, Xu Y, Chang L, Guo C, Cao X. Endoscopic versus laparoscopic resection of gastrointestinal stromal tumors at the esophagogastric junction using propensity score matching analysis. Sci Rep. 2025;15:15916. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/