Published online Feb 15, 2026. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v18.i2.115224

Revised: November 28, 2025

Accepted: December 29, 2025

Published online: February 15, 2026

Processing time: 97 Days and 22.1 Hours

With the aging of the population, the proportion of older patients with colorectal cancer (CRC) is increasing annually. Preoperative frailty and chronic inflammatory responses may increase the risk of postoperative complications and affect long-term survival.

To assess modified frailty index (mFI) and systemic immune-inflammation index (SII) for predicting postoperative prognosis in older patients with CRC.

We retrospectively analyzed 247 older patients with CRC who underwent radical resection. The SII was calculated as platelet count × neutrophil count/lymphocyte count. Patients were grouped by complication occurrence. Univariate and mul

The 30-day complication rate was 12.55%. Multivariate logistic regression analysis identified smoking history [odds ratio (OR) = 4.822], prolonged operation time (OR = 1.037), and elevated preoperative mFI (OR = 9.342) and SII (OR = 1.002) as independent risk factors for postoperative complications (P < 0.05). On survival analysis, the average recurrence-free survival (RFS) for patients with a low mFI was 47.04 months [95% confidence interval (CI): 45.30-48.79], significantly better than the 33.83 months (95%CI: 31.31-36.36) for patients with a high mFI (log-rank, P < 0.001). The average RFS for patients with a low SII was 47.00 months (95%CI: 45.07-48.94), significantly better than the 40.06 months (95%CI: 31.37-43.74) for those with a high SII (log-rank, P < 0.001).

In older patients with CRC, the preoperative mFI and SII were significantly correlated with postoperative complications and RFS, warranting closer attention to early recurrence detection and intervention.

Core Tip: Preoperative assessment using the modified frailty index and systemic immune-inflammation index provides valuable predictive ability for evaluating surgical risk and prognosis in older patients undergoing colorectal cancer resection. Incorporating these indices into clinical practice can help healthcare providers stratify older patients with colorectal cancer based on surgical risk, allowing targeted perioperative management to improve recovery and survival rates.

- Citation: Qi XS, Xie J, Liu NL, Yang L. Relationship between preoperative modified frailty index, immune-inflammation index, and outcomes of colorectal cancer surgery in older patients. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2026; 18(2): 115224

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v18/i2/115224.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v18.i2.115224

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is a major global public health concern, ranking as third in the incidence of malignant tumors and second in the fatality rate[1]. Asia bears the heaviest burden in terms of regional distribution, followed by Europe and North America[1]. Notably, the International Agency for Research on Cancer predicts that, by 2040, the global annual number of new CRC cases will surge by 63%, and the number of deaths will increase by 73%[2]. In older patients, the efficacy and safety of surgical treatment face challenges owing to characteristics such as decline in physiological function, multiple comorbidities, and impaired immune function. The traditional assessment system mainly relies on tumor-node-metastasis-based tumor staging and organ function tests[3], which make it difficult to comprehensively reflect the unique physiological reserve decline and multimorbidity state in older patients, leading to clinical decision-making biases and inaccurate prognosis predictions.

In recent years, the concept of frailty has gained widespread attention in geriatrics, referring to a state of reduced stress resistance due to a decline in multisystem physiological reserves[4]. The modified frailty index (mFI), which quantifies 11 clinical indicators, effectively captures the preoperative frailty characteristics of older patients and demonstrates superior performance in predicting postoperative complications compared to traditional assessment tools[5]. Additionally, the systemic immune-inflammation index (SII), a composite indicator integrating neutrophil, lymphocyte, and platelet counts, objectively reflects the host immune-inflammatory balance and has shown significant value in the prognostic assessment of various malignancies[6,7].

However, the impact of preoperative mFI and SII on surgical outcomes in older patients with CRC remains unclear. A systematic investigation of the relationship between these two indicators and surgical complications, postoperative recovery, and long-term prognosis is of great significance for establishing a more precise risk assessment system and guiding individualized treatment decisions. This retrospective study, based on the perspective of clinical translational medicine, aimed to systematically explore the predictive power of preoperative mFI and SII on short-term complications and prognosis after radical surgery in older patients with CRC.

This retrospective study analyzed 274 patients who underwent curative CRC resection at the Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University between January 2021 and October 2024. The inclusion criteria were: (1) First-time CRC diagnosis with complete clinicopathological data available; (2) Age ≥ 60 years, undergoing curative CRC surgery with postoperative pathological confirmation; (3) No neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy or immunotherapy prior to diagnosis; (4) No long-term use of corticosteroids or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; and (5) No other concurrent malignancies. The exclusion criteria were: (1) Preoperative or intraoperative detection of distant metastasis; (2) Active infection at the time of surgery; (3) Blood transfusion within the last 3 months; (4) Hematologic/immune disorders or other primary tumors; and (5) Severe hepatic or renal dysfunction. This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University.

Excel 2019 was used to collect and record the following patient information: General clinical data, blood cell counts in the most recent routine blood tests, treatment details, postoperative pathological reports, postoperative complications, and follow-up information: (1) General clinical data: Age, sex, body mass index, smoking history, and history of alcohol consumption; (2) Routine blood tests: Levels of white blood cells, neutrophils, platelets, lymphocytes, etc.; (3) Treatment details: Surgical time and intraoperative blood loss; (4) Tumor characteristics: Tumor location (rectum or colon), size, degree of differentiation, tumor-node-metastasis stage, etc.; (5) Postoperative complications within 30 days: Cardiovas

(1) Analysis of independent risk factors for 30-day postoperative complications: The patients were divided into com

The data were analyzed using SPSS 25.0 statistical software. Continuous data were expressed as mean ± SD, and com

This study included 247 older patients who underwent radical surgery for CRC, with a postoperative 30-day compli

The postoperative complication and non-complication groups had statistically significant differences in age, body mass index, smoking history, drinking history, operation time, tumor size, degree of tumor differentiation, preoperative mFI, and preoperative SII (P < 0.05; Table 1).

| Variable | Complication group (n = 31) | Non-complication group (n = 216) | t/χ2 | P value |

| Age (years) | 73.87 ± 6.34 | 71.17 ± 6.46 | 2.182 | 0.030 |

| Sex | 1.767 | 0.184 | ||

| Male | 21 (7.74) | 119 (55.09) | ||

| Female | 10 (32.26) | 97 (44.91) | ||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.12 ± 1.48 | 22.60 ± 1.30 | 2.074 | 0.039 |

| Smoking history | 8.786 | 0.003 | ||

| Yes | 18 (58.06) | 67 (31.02) | ||

| No | 13 (41.94) | 149 (68.98) | ||

| Drinking history | 4.461 | 0.035 | ||

| Yes | 17 (54.84) | 76 (35.19) | ||

| No | 14 (46.15) | 140 (64.81) | ||

| Operation time (minutes) | 182.42 ± 22.32 | 162.78 ± 20.59 | 4.915 | < 0.001 |

| Preoperative bleeding (mL) | 125.32 ± 26.39 | 123.17 ± 27.42 | 0.411 | 0.681 |

| Tumor site | 0.883 | 0.347 | ||

| Rectum | 14 (45.16) | 117 (54.17) | ||

| Colon | 17 (54.84) | 99 (45.83) | ||

| Tumor size | 12.114 | 0.001 | ||

| < 5 cm | 9 (29.03) | 134 (62.04) | ||

| ≥ 5 cm | 22 (70.97) | 82 (37.96) | ||

| Degree of tumor differentiation | 7.960 | 0.019 | ||

| High | 15 (48.39) | 101 (46.76) | ||

| Moderately | 7 (22.58) | 89 (41.20) | ||

| Poorly | 9 (29.03) | 26 (12.04) | ||

| TNM stage | 1.372 | 0.504 | ||

| I | 9 (29.03) | 71 (32.87) | ||

| II | 14 (45.16) | 108 (50.00) | ||

| III | 8 (25.81) | 37 (17.13) | ||

| Pre-operative mFI (points) | 6.19 ± 1.19 | 4.12 ± 0.86 | 9.338 | < 0.001 |

| Pre-operative SII (× 109/L) | 1091.43 ± 584.13 | 760.80 ± 370.50 | 3.064 | 0.004 |

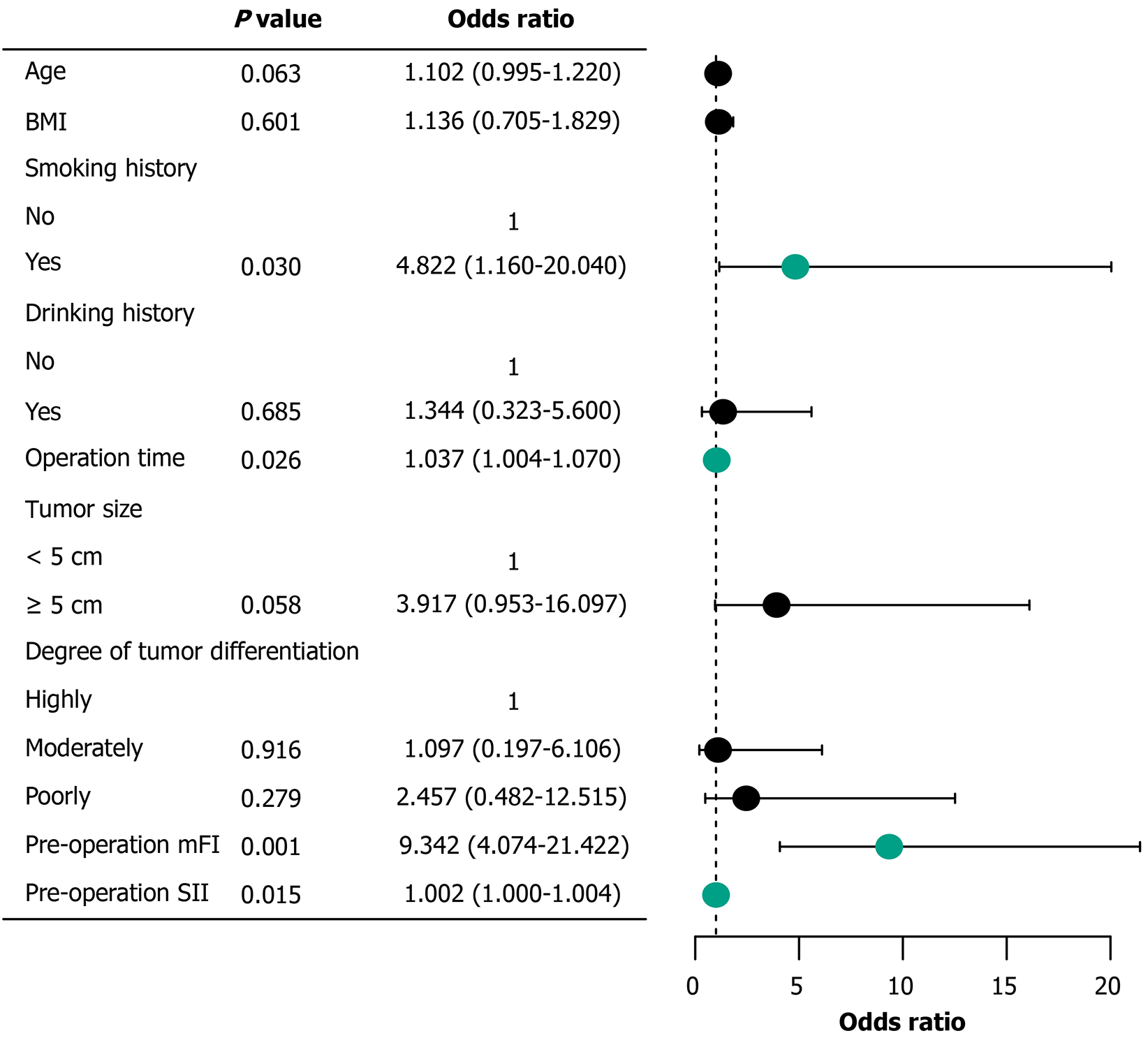

On conducting a multivariate logistic regression analysis on the nine variables with statistically significant differences in the univariate analysis, 4 variables showed statistical significance (P < 0.05): History of smoking, operation time, preo

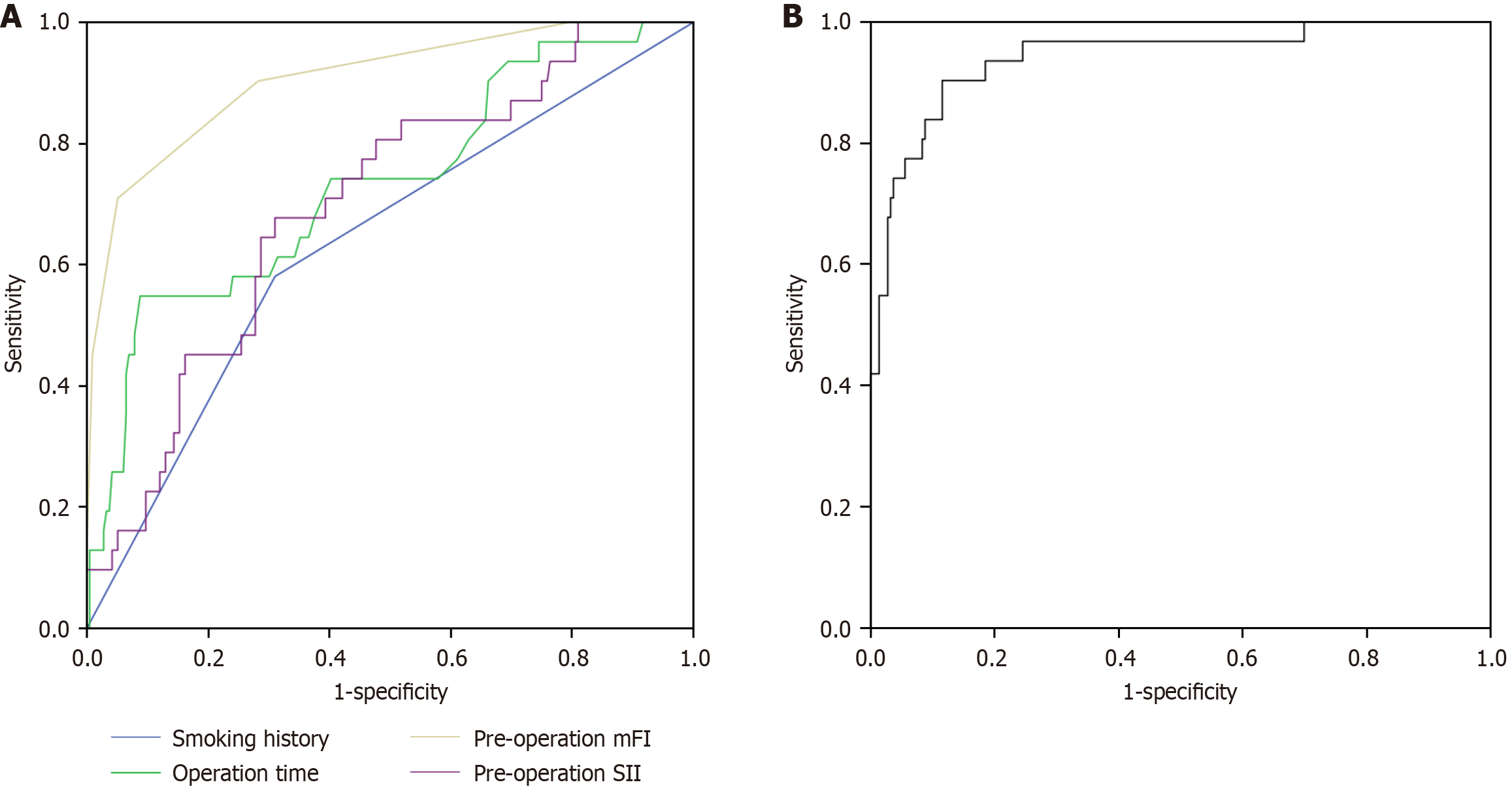

The area under the curve (AUC) values for predicting postoperative complications were 0.635 for smoking history [95% confidence interval (CI): 0.528-0.743]; 0.731, operative time (95%CI: 0.629-0.833); 0.906, preoperative mFI (95%CI: 0.845-0.968); and 0.698, preoperative SII (95%CI: 0.604-0.792). The corresponding sensitivities were 58.1%, 54.8%, 71.0%, and 67.7%, with specificities of 69.0%, 91.2%, 94.9%, and 69.0%, respectively (Figure 2A). Through logistic binary regression modeling combining the mFI and SII, a joint predictive factor was established as an independent test variable. This combined model demonstrated an AUC of 0.941 (95%CI: 0.893-0.989), with a sensitivity of 90.3% and a specificity of 88.4% (Figure 2B).

The preoperative mFI increased with the severity of complications, but the difference was not statistically significant (F = 1.758, P = 0.179). The preoperative SII significantly differed between the groups with different Clavien-Dindo grades of postoperative complications (F = 12.976, P < 0.001; Table 2).

| Postoperative complications | n | Pre-operative mFI | Pre-operative SII |

| IV grade | 1 | 8.00 ± 0.00 | 2945.22 ± 0.00 |

| III grade | 4 | 7.00 ± 0.00 | 1163.70 ± 79.74 |

| II grade | 16 | 6.06 ± 1.29 | 1249.71 ± 514.24 |

| I grade | 10 | 5.90 ± 1.10 | 623.90 ± 151.40 |

| F | 1.758 | 12.976 | |

| P value | 0.179 | < 0.001 |

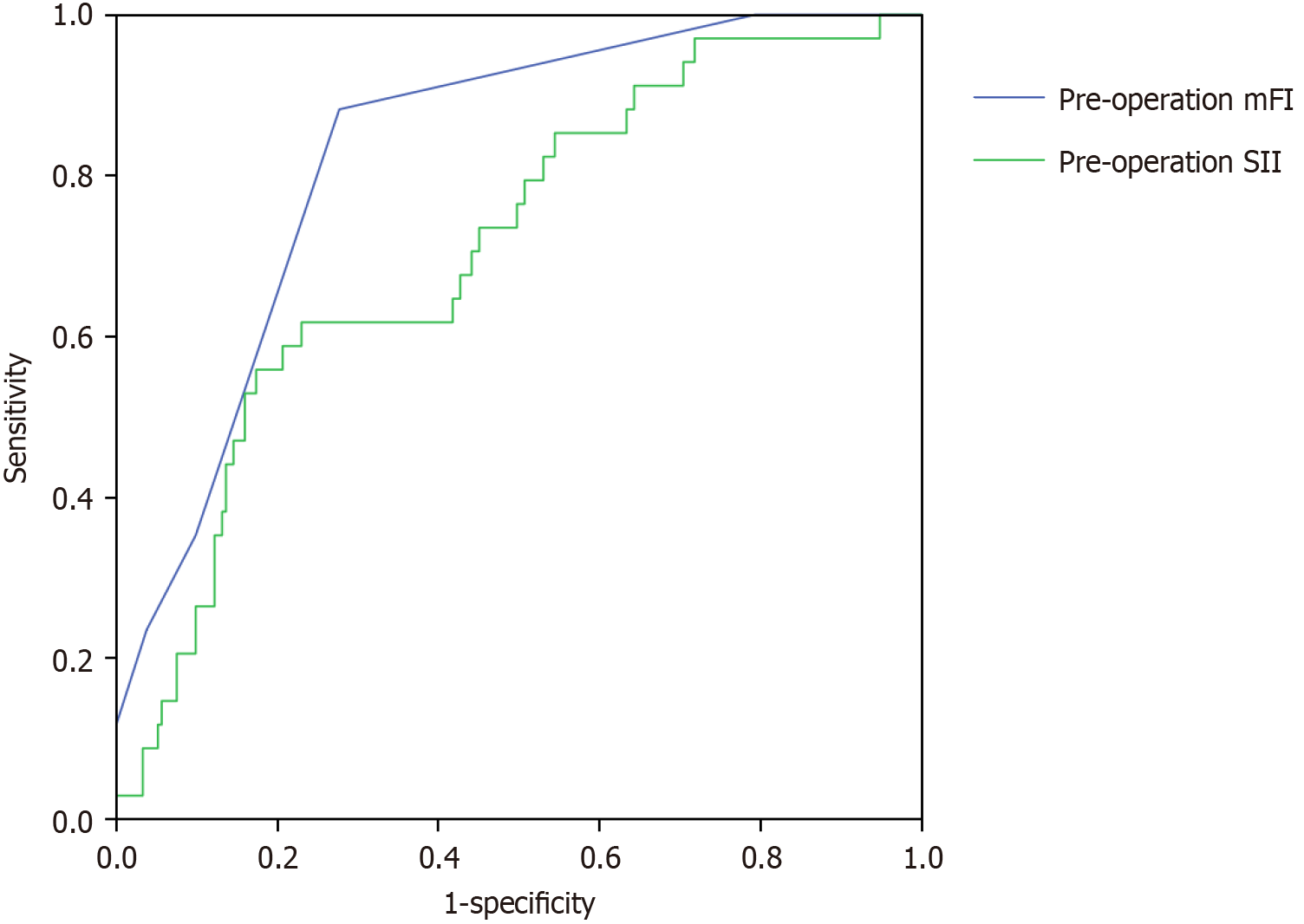

Follow-up was performed in 247 patients for a duration of 7-52 months and a median of 32 months. Postoperative recurrence occurred in 34 patients (recurrence rate, 13.77%). The cut-off value for the mFI was 4.5, with a sensitivity of 88.2% and specificity of 72.3%. The cutoff value for the SII was 927.45, with a sensitivity of 61.8% and a specificity of 77.0% (Figure 3).

Based on the ROC analysis results, the patients were divided into: High (mFI ≥ 4.5, n = 89) and low (mFI < 4.5, n = 158) mFI groups and high (SII ≥ 927.45 × 109/L, n = 70) and low (SII < 927.45 × 109/L, n = 177) SII groups. Compared with those in the low mFI group, the patients in the high mFI group were older, had a longer surgical duration, and a significantly higher proportion of tumors ≥ 5 cm (P < 0.05). Compared to those in the low-SII group, the patients in the high-SII group had a significantly prolonged surgical duration (P < 0.05; Table 3).

| Variable | Pre-operative mFI | t/χ2 | Pre-operative SII | t/χ2 | ||

| Low group (n = 158) | High group (n = 89) | Low group (n = 177) | High group (n = 70) | |||

| Age (years) | 70.84 ± 6.17 | 72.71 ± 6.90 | 2.193a | 71.27 ± 6.50 | 72.13 ± 6.48 | 0.941 |

| Sex | 0.173 | 0.142 | ||||

| Male | 88 (55.70) | 52 (58.43) | 99 (55.93) | 41 (58.57) | ||

| Female | 70 (44.30) | 37 (41.57) | 78 (44.07) | 29 (41.43) | ||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 22.62 ± 1.28 | 22.74 ± 1.43 | 0.637 | 22.71 ± 1.32 | 22.56 ± 1.36 | 0.780 |

| Smoking history | 1.488 | 2.130 | ||||

| Yes | 50 (31.65) | 35 (39.33) | 56 (31.64) | 29 (41.43) | ||

| No | 108 (68.35) | 54 (60.67) | 121 (68.36) | 41 (58.57) | ||

| Drinking history | 0.171 | 1.831 | ||||

| Yes | 61 (38.61) | 32 (35.96) | 62 (35.03) | 31 (44.29) | ||

| No | 97 (61.39) | 57 (64.04) | 115 (64.97) | 39 (55.71) | ||

| Operation time (minutes) | 163.11 ± 20.68 | 169.03 ± 23.21 | 2.068a | 162.72 ± 21.33 | 171.63 ± 21.69 | 2.944a |

| Preoperative bleeding (mL) | 123.35 ± 26.60 | 123.58 ± 28.53 | 0.064 | 122.90 ± 27.78 | 124.79 ± 26.01 | 0.488 |

| Tumor site | 1.909 | 2.103 | ||||

| Rectum | 89 (56.33) | 42 (47.19) | 99 (55.93) | 32 (45.71) | ||

| Colon | 69 (43.67) | 47 (52.81) | 78 (44.07) | 38 (54.29) | ||

| Tumor size | 9.573a | 0.178 | ||||

| < 5 cm | 103 (65.19) | 40 (44.94) | 101 (57.06) | 42 (60.00) | ||

| ≥ 5 cm | 55 (34.81) | 49 (55.06) | 76 (42.94) | 28 (40.00) | ||

| Degree of tumor differentiation | 4.688 | 0.129 | ||||

| High | 70 (44.30) | 46 (51.69) | 82 (46.33) | 34 (48.57) | ||

| Moderate | 69 (43.67) | 27 (30.34) | 70 (39.55) | 26 (37.14) | ||

| Poor | 19 (12.03) | 16 (17.98) | 25 (14.12) | 10 (14.29) | ||

| TNM stage | 0.094 | 1.731 | ||||

| I | 51 (32.28) | 29 (32.58) | 55 (31.07) | 25 (35.71) | ||

| II | 79 (50.00) | 43 (48.31) | 92 (51.98) | 30 (42.86) | ||

| III | 28 (17.72) | 17 (19.10) | 30 (16.95) | 15 (21.43) | ||

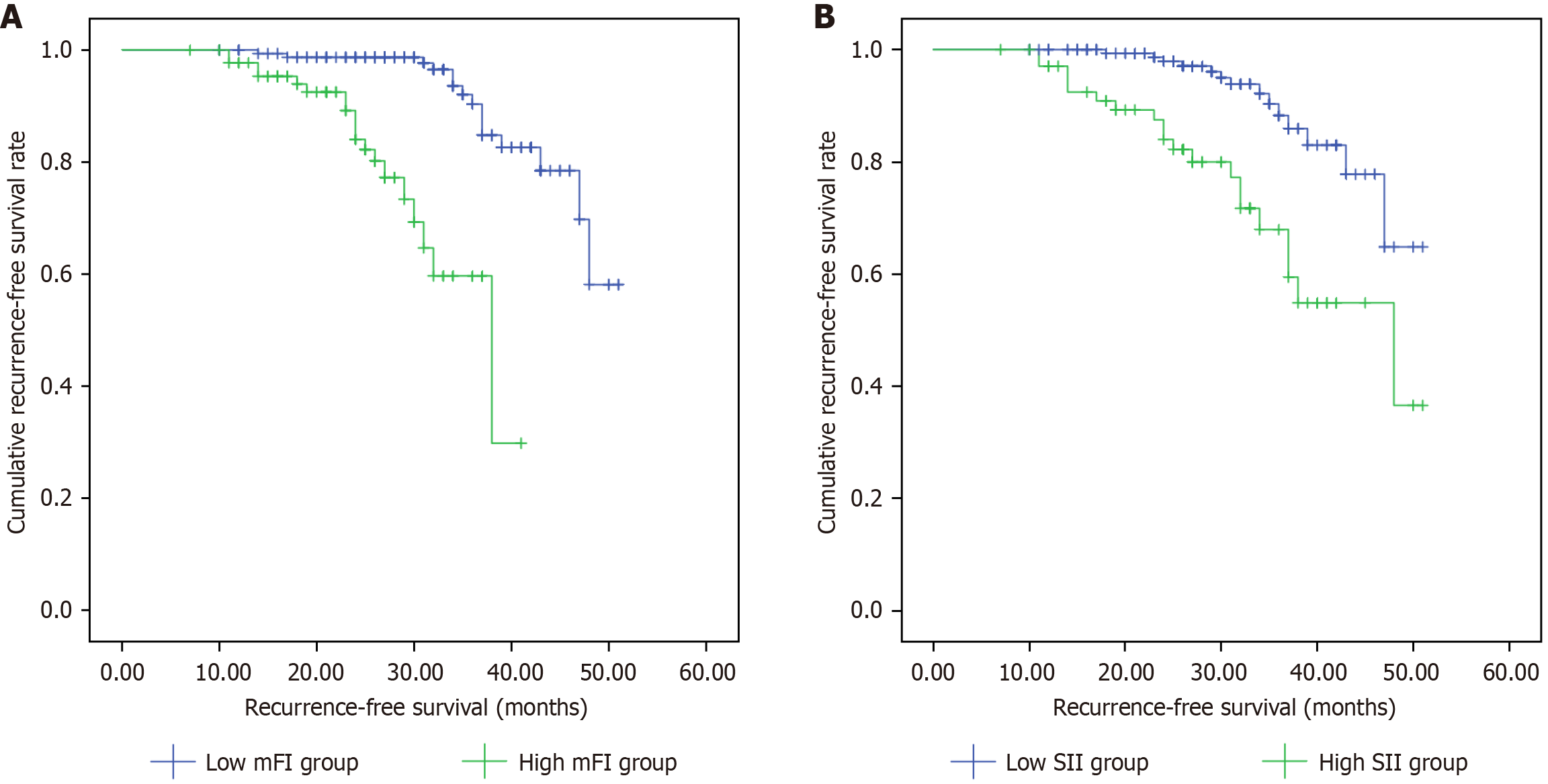

The mean RFS in the low mFI group was 47.04 months (95%CI: 45.30-48.79), significantly longer than 33.83 months (95%CI: 31.31-36.36) in the high mFI group, with a statistically significant difference between groups (log-rank test: χ2 = 32.787, P < 0.001; Figure 4A). Similarly, the mean RFS was 47.00 months (95%CI: 45.07-48.94) in the low SII group com

Although radical surgery remains the primary treatment for CRC[8], older patients face a significantly higher risk of postoperative complications and mortality owing to physiological decline and a high prevalence of chronic diseases, resulting in reduced surgical tolerance. However, the existing surgical risk assessment systems (such as the American Standards Association classification) primarily target the general population, lack quantitative criteria specifically for older patients, and are susceptible to subjective influences. Frailty, a core manifestation of geriatric syndrome, is closely associated with adverse postoperative outcomes[4]. The frailty index can effectively quantify the health status of older patients[9,10]; however, its comprehensive assessment requires clinical adaptation. In contrast, the mFI enables rapid calculation using data from medical histories and physical examinations to predict surgical outcomes. The mFI is strongly correlated with complications and mortality following hepatic and colectomy procedures[11,12]. The SII, derived from the neutrophil, lymphocyte, and platelet counts, reflects the inflammatory status of the patient. Both the inflammatory state and immune function significantly influence postoperative complications, recurrence, and mortality. Retrospective analyses indicate that the preoperative SII serves as a valuable predictor of complications in patients with advanced ovarian cancer and lung resection[13,14]. Therefore, we hypothesized that the preoperative mFI and SII may effectively predict postoperative complications and prognosis in patients with CRC.

The incidence of complications within 30 days after radical surgery in older patients with CRC was 12.55%, which is consistent with the complication rates reported previously[15,16]. A history of smoking showed the strongest correlation with postoperative complications [odds ratio (OR) = 4.822]. This might be related to the multi-system damage caused by smoking. Harmful substances in tobacco can cause microcirculatory disorders[17], reduce tissue oxygen supply, and delay wound healing. Furthermore, smoking suppresses immune function, particularly by reducing the phagocytic function of alveolar macrophages, thereby significantly increasing the risk of postoperative pulmonary infections[18]. In addition, smoking can affect collagen synthesis, which may explain the higher incidence of anastomotic leakage observed in smokers in this study[19].

Prolonged surgical time (OR = 1.037) was another significant risk factor. For every additional minute of surgery, the risk of complications increased by 3.7%, consistent with the findings of Cai et al[20]. A retrospective analysis by de’Angelis et al[21] of 1549 patients with nonmetastatic right colon adenocarcinoma found that, when the surgery time exceeded 200 minutes, the risk of noninfectious complications after laparoscopic right hemicolectomy significantly increased. Additionally, meta-analysis results have suggested that surgery durations ≥ 180 minutes significantly in

This study confirmed that preoperative mFI is a reliable indicator for predicting postoperative complications in older patients with CRC. The results show that an elevated mFI (OR = 9.342) is significantly associated with the occurrence of postoperative complications, with an excellent predictive performance (AUC = 0.906). This finding is highly consistent with the prospective study by Zhang et al[24], which confirmed through propensity score matching analysis that patients in the frailty group had a significantly higher risk of intra-abdominal infection (10.7% vs 1.3%) and that frailty is an independent risk factor for infection (OR = 12.014). In addition, a systematic review[25] further confirmed that frailty was significantly associated with multiple adverse prognostic indicators such as postoperative complications, mortality, and prolonged hospital stay. A meta-analysis by Xia et al[12] that included 16 studies with 245747 patients also showed that patients with frailty had a significantly higher risk of postoperative complications (OR = 1.94). Additionally, the mean mFI increased with the severity of postoperative complications, suggesting that preoperative frailty may be associated with the severity of complications, although this association was not statistically significant. This lack of significance may be due to the small sample size (particularly in the grade IV complication group, which included only one case), resulting in insufficient statistical power. As patients with frailty have diminished physiological reserves, they exhibit a reduced tolerance to surgical stress and are more prone to severe complications. However, the mFI may be limited by its composite assessment indicators (e.g., comorbidities and functional status), which may not fully capture the factors directly related to surgical risk. In contrast, a high preoperative SII was significantly associated with more severe postoperative complications, indicating that the systemic inflammatory status is a key driver of adverse postoperative outcomes.

In terms of prognosis, this study found that the median RFS of patients in the low mFI group was significantly better than that of the high mFI group (47.04 months vs 33.83 months). A meta-analysis showed that patients with frailty had significantly worse overall survival [relative risk (RR) = 2.21], cancer-specific survival (RR = 4.60), and RFS (RR = 1.72)[26]. Zhou et al[27] found in a systematic review that patients with frailty had higher mortality risks of 99%, 376%, and 473% at 30 days, 90 days, and 1 year postoperatively, respectively. From the perspective of pathophysiological mecha

This study demonstrated that the SII, as an accessible and cost-effective biomarker, can effectively predict posto

Regarding prognosis, patients in the low-SII group showed significantly superior RFS than those in the high-SII group (47.00 months vs 40.06 months). Consistent with the conclusions of Feng et al[29] on the predictive value of the SII, our findings specifically highlight SII’s clinical relevance in older populations. Some studies proposed SII cutoff (≥ 451.05) and dynamic monitoring approach demonstrated comparable predictive performance in our cohort, suggesting that perioperative SII trends may hold greater clinical significance than single measurements[31,32]. Notably, our study identified an optimal SII cutoff of 927.45, showing a substantial discrepancy with Sun et al’s threshold[31] (≥ 451.05). In a retrospective study, Chen et al’s ROC analysis[33] established SII > 340 as the high-value threshold, whereas Xie et al[34] recommended 649.45 as the appropriate cutoff while investigating the predictive role of SII in metastatic CRC using a median-based methodology.

These variations in the proposed SII cutoffs likely stem from differences in the study inclusion criteria, threshold determination methods, sample characteristics, follow-up durations, and testing timings. For instance, immune-function decline and chronic-inflammatory state are more pronounced among older adults, potentially leading to differences in SII-value distribution from that in younger patients or the general population. The immune system of older adults exhibits “immunosenescence”, characterized by decline in lymphocyte function, changes in neutrophil activity, and elevated levels of chronic inflammatory markers. Accordingly, the SII values of older adults may be relatively high under normal physiological conditions, thereby affecting the determination of the critical value. Although we did not conduct further analysis on the predictive efficacy of SII in different tumor stages and age subgroups, existing studies have shown that the higher the tumor stage, the more significant the inflammatory response. This inflammatory response may be further exacerbated in older patients with CRC, leading to increased SII values. Therefore, the SII cutoff values may need to be further calibrated in different tumor stages and age subgroups.

In older patients with CRC, the combined effect of the mFI and SII may significantly influence the risk of postoperative complications and prognosis through multiple mechanisms. The frail state (high mFI) directly weakens the patient’s physiological reserve and tolerance to surgical stress and may also indirectly increase the SII value by exacerbating chronic inflammatory responses. Conversely, the systemic inflammatory state reflected by a high SII will further deplete the patient’s physiological reserve and weaken the immune defense capacity, thus forming a vicious cycle. When a patient has both a high mFI and high SII, the risk of postoperative complications is significantly increased and may shorten the patient’s RFS period. Our research results show that the predictive efficacy of combining the mFI and SII is superior to that of a single indicator (AUC = 0.941), which further supports the possible synergistic effect between them. This finding suggests that multidimensional assessment can more accurately predict the risk of postoperative complications.

The mFI and SII assess the risk status of patients from different angles: The mFI primarily reflects the patient’s physiological reserve and organ function status, whereas the SII evaluates the patient’s pathological state from inflammatory and immune perspectives. The integration of the mFI and SII combines the patient’s preoperative baseline condition and immune-inflammation balance, enabling the early identification of high-risk patients. The combined assessment method has significant advantages in clinical practice. As noted by Sun et al[32], an ideal predictive model should balance comprehensive evaluation with clinical operability. The mFI is based on routine clinical indicators, and the SII is derived from basic blood tests. Combining these indicators does not add to the clinical workload but provides a more comprehensive risk assessment. Therefore, in patients with both frailty and inflammation, more proactive preoperative interventions and closer postoperative monitoring are required.

This study has some limitations. For example, retrospective studies carry risks of data completeness and measurement bias. Some confounding factors (such as the severity of specific comorbidities, preoperative nutritional status, surgical methods, and concomitant medications) may not have been fully controlled. The included patients mainly came from tertiary medical centers, which may not fully represent the characteristics of older patients in community hospitals. The 11 indicators included in the calculation of the mFI were recorded differently in various medical institutions. The calculation of the SII is affected by laboratory methods and the timing of blood sampling. Future work is needed to further refine the risk assessment system through prospective studies and mechanistic exploration, ultimately achieving individualized and precise surgical treatment strategies for older patients.

Overall, smoking history, prolonged surgical time, an elevated preoperative mFI, and an elevated SII were independent risk factors of complications in older patients undergoing laparoscopic CRC resection. Combining the mFI and SII has a good predictive ability for postoperative complications. In addition, preoperative mFI and SII levels were associated with RFS in patients with CRC after surgery. It is recommended that mFI and SII assessments be incorporated into routine clinical practice to achieve more precise perioperative management.

| 1. | Ionescu VA, Gheorghe G, Bacalbasa N, Chiotoroiu AL, Diaconu C. Colorectal Cancer: From Risk Factors to Oncogenesis. Medicina (Kaunas). 2023;59:1646. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 35.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Morgan E, Arnold M, Gini A, Lorenzoni V, Cabasag CJ, Laversanne M, Vignat J, Ferlay J, Murphy N, Bray F. Global burden of colorectal cancer in 2020 and 2040: incidence and mortality estimates from GLOBOCAN. Gut. 2023;72:338-344. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 511] [Cited by in RCA: 1311] [Article Influence: 437.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (13)] |

| 3. | Delattre JF, Selcen Oguz Erdogan A, Cohen R, Shi Q, Emile JF, Taieb J, Tabernero J, André T, Meyerhardt JA, Nagtegaal ID, Svrcek M. A comprehensive overview of tumour deposits in colorectal cancer: Towards a next TNM classification. Cancer Treat Rev. 2022;103:102325. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Kim DH, Rockwood K. Frailty in Older Adults. N Engl J Med. 2024;391:538-548. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 365] [Article Influence: 182.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Youssef S, Malik S, Ali A, Rao M. Modified Rockwood frailty index is predictive of adverse outcomes in elderly populations undergoing major abdominal surgery: is it a practical tool though? Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2021;406:1245-1246. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Nakamoto S, Ohtani Y, Sakamoto I, Hosoda A, Ihara A, Naitoh T. Systemic Immune-Inflammation Index Predicts Tumor Recurrence after Radical Resection for Colorectal Cancer. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2023;261:229-238. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kou J, Huang J, Li J, Wu Z, Ni L. Systemic immune-inflammation index predicts prognosis and responsiveness to immunotherapy in cancer patients: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Clin Exp Med. 2023;23:3895-3905. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Biller LH, Schrag D. Diagnosis and Treatment of Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: A Review. JAMA. 2021;325:669-685. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 398] [Cited by in RCA: 1732] [Article Influence: 346.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 9. | Veronese N, Custodero C, Cella A, Demurtas J, Zora S, Maggi S, Barbagallo M, Sabbà C, Ferrucci L, Pilotto A. Prevalence of multidimensional frailty and pre-frailty in older people in different settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res Rev. 2021;72:101498. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 144] [Cited by in RCA: 170] [Article Influence: 34.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Gu C, Lu A, Lei C, Wu Q, Zhang X, Wei M, Wang Z. Frailty index is useful for predicting postoperative morbidity in older patients undergoing gastrointestinal surgery: a prospective cohort study. BMC Surg. 2022;22:57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Bludevich BM, Emmerick I, Uy K, Maxfield M, Ash AS, Baima J, Lou F. Association Between the Modified Frailty Index and Outcomes Following Lobectomy. J Surg Res. 2023;283:559-571. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Xia L, Yin R, Mao L, Shi X. Prevalence and impact of frailty in patients undergoing colorectal cancer surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis based on modified frailty index. J Surg Oncol. 2024;130:604-612. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Köse O, Köse E, Gök K, Bostancı MS. The Role of the Systemic Immune-Inflammation Index in Predicting Postoperative Complications in Ovarian Cancer Patients: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Cancers (Basel). 2025;17:1124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Xiaowei M, Wei Z, Qiang W, Yiqian N, Yanjie N, Liyan J. Assessment of systemic immune-inflammation index in predicting postoperative pulmonary complications in patients undergoing lung cancer resection. Surgery. 2022;172:365-370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Ohkuma M, Takano Y, Goto K, Okamoto A, Koyama M, Abe T, Nakano T, Takeda Y, Kosuge M, Eto K. Significance of Naples prognostic score for postoperative complications after colorectal cancer surgery. Surg Today. 2025;55:1481-1487. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | McGovern J, Grayston A, Coates D, Leadbitter S, Hounat A, Horgan PG, Dolan RD, McMillan DC. The relationship between the modified frailty index score (mFI-5), malnutrition, body composition, systemic inflammation and short-term clinical outcomes in patients undergoing surgery for colorectal cancer. BMC Geriatr. 2023;23:9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Korneeva NV, Sirotin BZ. Microcirculatory Bed, Microcirculation, and Smoking-Associated Endothelial Dysfunction in Young Adults. Bull Exp Biol Med. 2017;162:824-828. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Sørensen LT. Wound healing and infection in surgery: the pathophysiological impact of smoking, smoking cessation, and nicotine replacement therapy: a systematic review. Ann Surg. 2012;255:1069-1079. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 500] [Cited by in RCA: 470] [Article Influence: 33.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Bédard A, Valji RH, Jogiat U, Verhoeff K, Turner SR, Karmali S, Kung JY, Bédard ELR. Smoking status predicts anastomotic leak after esophagectomy: a systematic review & meta-analysis. Surg Endosc. 2024;38:4152-4159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Cai W, Wang L, Wang W, Zhou T. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the risk factors of surgical site infection in patients with colorectal cancer. Transl Cancer Res. 2022;11:857-871. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | de'Angelis N, Schena CA, Piccoli M, Casoni Pattacini G, Pecchini F, Winter DC, O'Connell L, Carcoforo P, Urbani A, Aisoni F, Martínez-Pérez A, Celentano V, Chiarugi M, Tartaglia D, Coccolini F, Arces F, Di Saverio S, Frontali A, Fuks D, Denet C, Genova P, Guerrieri M, Ortenzi M, Kraft M, Pellino G, Vidal L, Lakkis Z, Antonot C, Perrotto O, Vertier J, Le Roy B, Micelli Lupinacci R, Milone M, De Palma GD, Petri R, Santangelo A, Scabini S, De Rosa R, Tonini V, Valverde A, Bianchi G, Carra MC, Zorcolo L, Deidda S, Restivo A, Andolfi E, Paquet JC, Bartoletti S, Orci L, Ris F, Espin E; MERCY Study Collaborating Group. Impact of operation duration on postoperative outcomes of minimally-invasive right colectomy. Colorectal Dis. 2022;24:1505-1515. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Xu Z, Qu H, Kanani G, Guo Z, Ren Y, Chen X. Update on risk factors of surgical site infection in colorectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2020;35:2147-2156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Xu Z, Qu H, Gong Z, Kanani G, Zhang F, Ren Y, Shao S, Chen X, Chen X. Risk factors for surgical site infection in patients undergoing colorectal surgery: A meta-analysis of observational studies. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0259107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Zhang H, Zhang H, Wang W, Ye Y. Effect of preoperative frailty on postoperative infectious complications and prognosis in patients with colorectal cancer: a propensity score matching study. World J Surg Oncol. 2024;22:154. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Michaud Maturana M, English WJ, Nandakumar M, Li Chen J, Dvorkin L. The impact of frailty on clinical outcomes in colorectal cancer surgery: a systematic literature review. ANZ J Surg. 2021;91:2322-2329. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Chen S, Ma T, Cui W, Li T, Liu D, Chen L, Zhang G, Zhang L, Fu Y. Frailty and long-term survival of patients with colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2022;34:1485-1494. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Zhou Y, Zhang XL, Ni HX, Shao TJ, Wang P. Impact of frailty on short-term postoperative outcomes in patients undergoing colorectal cancer surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2024;16:893-906. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Gottesman D, McIsaac DI. Frailty and emergency surgery: identification and evidence-based care for vulnerable older adults. Anaesthesia. 2022;77:1430-1438. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Feng L, Xu R, Lin L, Liao X. Effect of the systemic immune-inflammation index on postoperative complications and the long-term prognosis of patients with colorectal cancer: a retrospective cohort study. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2022;13:2333-2339. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Akgul C, Colapkulu-Akgul N, Gunes A. Prognostic Value of Systemic Inflammatory Markers and Scoring Systems in Predicting Postoperative 30-Day Complications and Mortality in Colorectal Cancer Surgery: A Retrospective Cross-Sectional Analysis. Ann Ital Chir. 2024;95:636-647. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Sun J, Zhong X, Yin X, Wu H, Li L, Yang R. Construction and validation of a nomogram for predicting disease-free survival after radical resection of rectal cancer using perioperative inflammatory indicators. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2024;15:668-680. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Sun J, Yang R, Wu H, Li L, Gu Y. Prognostic value of preoperative combined with postoperative systemic immune-inflammation index for disease-free survival after radical rectal cancer surgery: a retrospective cohort study. Transl Cancer Res. 2024;13:371-380. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Chen JH, Zhai ET, Yuan YJ, Wu KM, Xu JB, Peng JJ, Chen CQ, He YL, Cai SR. Systemic immune-inflammation index for predicting prognosis of colorectal cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:6261-6272. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 250] [Cited by in RCA: 528] [Article Influence: 58.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (12)] |

| 34. | Xie QK, Chen P, Hu WM, Sun P, He WZ, Jiang C, Kong PF, Liu SS, Chen HT, Yang YZ, Wang D, Yang L, Xia LP. The systemic immune-inflammation index is an independent predictor of survival for metastatic colorectal cancer and its association with the lymphocytic response to the tumor. J Transl Med. 2018;16:273. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 12.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/