Published online Feb 15, 2026. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v18.i2.115179

Revised: November 18, 2025

Accepted: December 19, 2025

Published online: February 15, 2026

Processing time: 108 Days and 1.6 Hours

Follicular thyroid carcinoma (FTC) is the second most common subtype of thyroid malignancy, with distant metastases most often to the bones, lungs, brain, and liver, and only rarely to other sites. Rectal follicular thyroid-like carcinoma is a rare condition characterized by infiltration of FTC within the rectal wall. There are almost no literature reports.

We report a case of rectal thyroid-like follicular carcinoma in a 61-year-old woman. The patient presented with intermittent rectal bleeding, and a colono

Rectal follicular thyroid-like carcinoma may arise from malignant struma ovarii, highlighting the need to consider ovarian origins in atypical metastases of FTC.

Core Tip: We report a rare case of rectal follicular thyroid-like carcinoma. This case highlights the necessity of including an ovarian origin in the differential diagnosis when encountering metastases of follicular thyroid carcinoma in atypical lo

- Citation: Li JL, Cheng C, Zhang P, Fan J, Zhang L, Zhu LR, Tao KX, Cai M. Rectal follicular thyroid-like carcinoma: A case report and review of literature. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2026; 18(2): 115179

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v18/i2/115179.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v18.i2.115179

Follicular thyroid carcinoma (FTC) accounts for 10%-15% of all thyroid malignancies. It typically metastasizes hematogenous to the bones, lungs, brain, and liver, while spread to other organs is uncommon[1,2]. However, when distant organs show metastasis of thyroid carcinoma, malignant struma ovarii (MSO) should also be considered in the differential diagnosis. Struma ovarii is a highly differentiated monodermal teratoma composed predominantly (> 50%) of thyroid tissue, and accounts for < 3% of all ovarian teratomas[3,4]. MSO represents approximately 5% of struma ovarii and is characterized by malignant thyroid tissue within the ovary. Distant metastasis of MSO is exceedingly rare, with few reports in the literature[5,6]. Here, we present a case of rectal follicular thyroid-like carcinoma, and review the clinical, pathological, and therapeutic implications of FTC and struma ovarii.

A 61-year-old woman presented with a 1-week history of intermittent rectal bleeding.

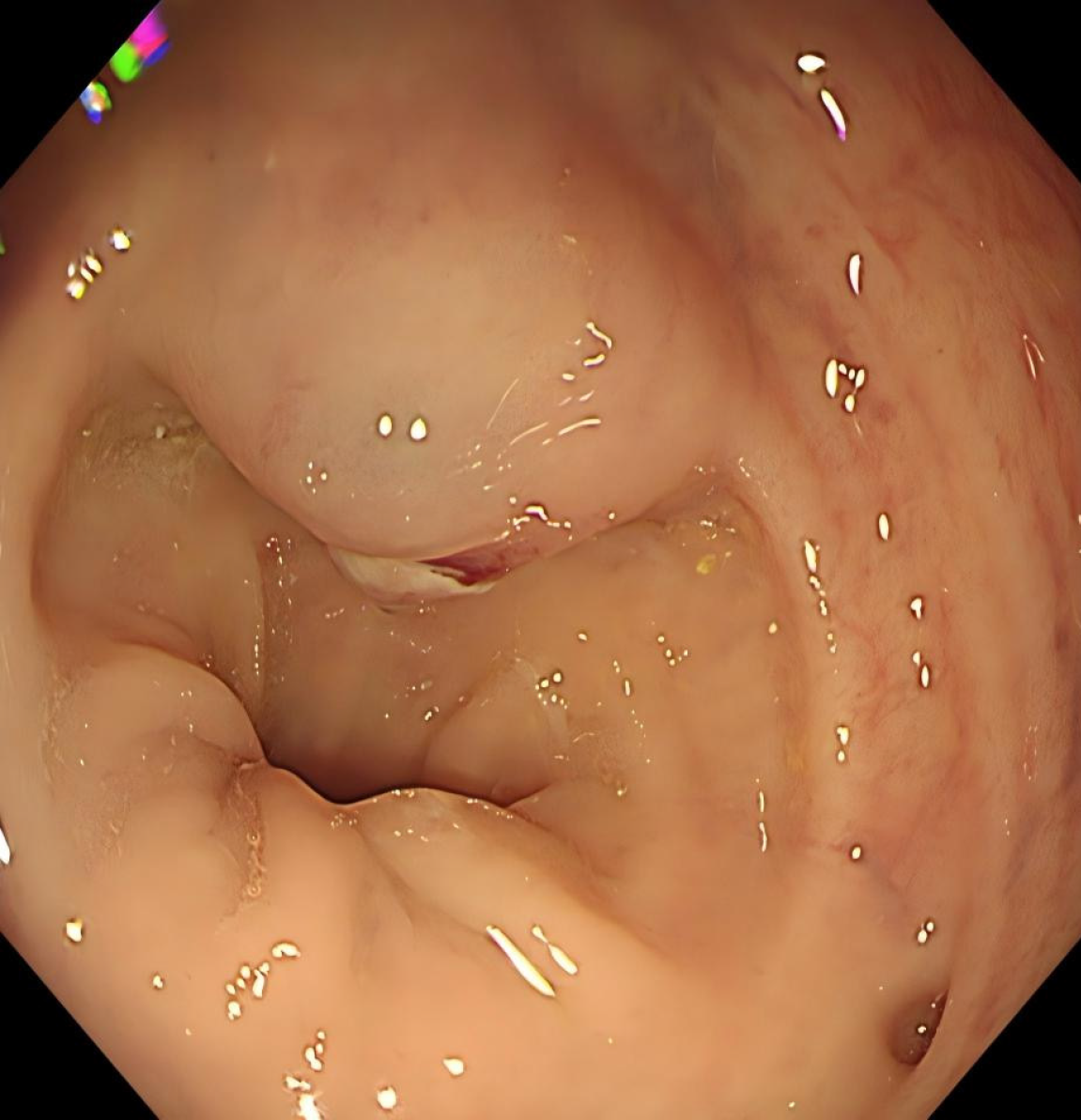

The patient was admitted to Union Hospital due to intermittent rectal bleeding. Colonoscopy revealed a 2.0 cm × 3.0 cm elevated lesion with surface ulceration located 10 cm from the anal verge (Figure 1). Endoscopic ultrasound demonstrated poor delineation of the mucosal and muscularis propria layers, appearing as a mixed echogenic solid mass.

The patient had a history of right oophorectomy and adnexectomy for ovarian teratoma 20 years earlier.

The patient denied any family history of malignant tumors.

The abdomen was flat and soft. Surgical incision scars were seen on the abdomen. Digital rectal examination revealed blood staining of the finger cots.

Laboratory examination revealed no abnormalities.

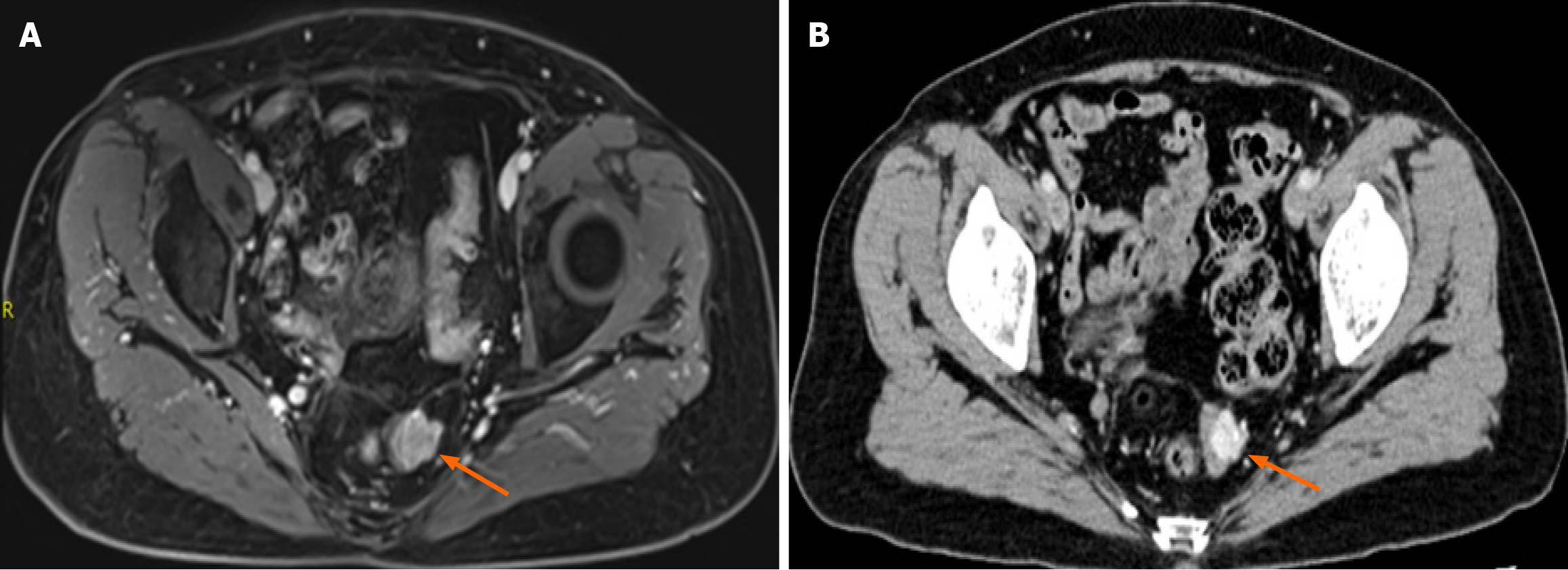

Pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed focal thickening of the upper rectal wall with a nodular mass protruding into the lumen (Figure 2A). Contrast-enhanced abdominal computed tomography (CT) confirmed localized rectal wall thickening with mild enhancement (Figure 2B).

Based on CT, endoscopy, and other relevant examinations, the patient was diagnosed with rectal thyroid-like follicular carcinoma.

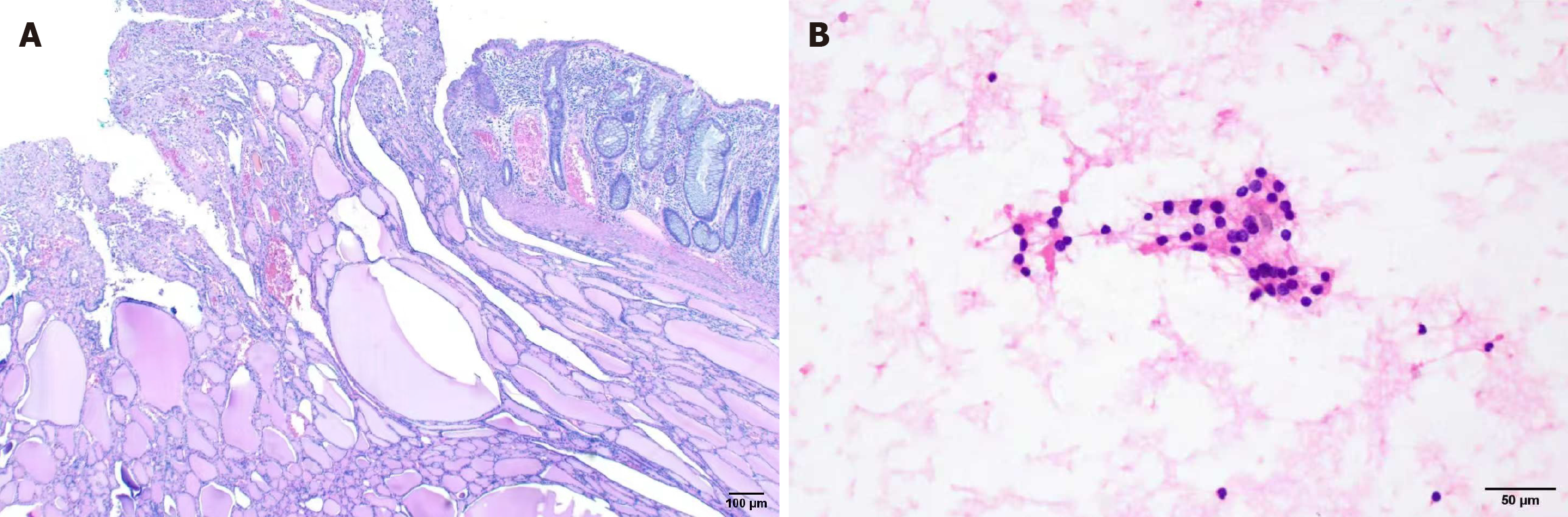

After an informed discussion, a laparoscopic partial rectal resection was performed for the tumor. Pathological examination revealed infiltration of thyroid tissue within the mucosa and muscularis propria of the rectal wall, with features of malignancy, consistent with metastatic FTC (Figure 3A).

The postoperative course was uneventful, and rectal bleeding resolved. Postoperative thyroid function tests were within normal limits. Neck ultrasound demonstrated a solid nodule in the right thyroid lobe, measuring approximately 16.7 mm × 12.6 mm× 9.1 mm (American College of Radiology Thyroid Imaging Reporting and Data System 4). It was classified as Bethesda II according to the fine needle aspiration cytology, indicating a benign nodule (Figure 3B). The patient was discharged on postoperative day 7. Follow-up MRI of the hepatobiliary system, retroperitoneum, and pelvis two months postoperatively revealed no evidence of tumor metastasis. At 6 months postoperatively, the patient was still alive.

FTC typically occurs in middle-aged and elderly women, with incidence increasing with age. The prognosis is generally less favorable in the elderly[7]. FTC spreads predominantly via the hematogenous route, most commonly to bone, lung, brain, and liver, while metastasis to other sites is uncommon[8,9]. Struma ovarii is itself rare, representing < 3% of ovarian teratomas, and less than 5% of these cases are malignant[4,5]. MSO usually involves a unilateral ovary and is most common in premenopausal women, with an average age of 45[10]. Retrospective data suggest that MSO typically metastasizes within the pelvis and abdomen, with rare spread to the liver, lungs, bones, or brain, and no clear correlation between metastatic sites and histological morphology[11-13]. Some studies suggest that molecular changes such as epidermal growth factor receptor or B-Raf proto-oncogene mutations may be related to malignant transformation and distant metastasis of struma ovarii, although the precise mechanisms remain uncertain[5,13-15].

When FTC is found in distant tissues, establishing the primary site is critical. In ovarian metastasis of FTC, the lesion consists exclusively of thyroid carcinoma cells, whereas SO contains other teratoma components[16]. Struma ovarii lacks the ability to invade and metastasize. However, distant metastases of MSO only contain malignant thyroid tissue, which is consistent with the characteristics of cancer cells in distant metastases of thyroid cancer[11]. Therefore, when FTC cells appear in the rectal wall, the primary tumor site must be confirmed. For patients diagnosed with struma ovarii, thyroid examination remains necessary. In this case, thyroid function tests were normal. The ultrasound showed a right-lobe nodule classified as American College of Radiology Thyroid Imaging Reporting and Data System 4, and fine-needle aspiration yielded Bethesda II (benign). Given the patient’s history of ovarian teratoma resection 20 years earlier, the rectal lesion was most consistent with MSO.

The clinical presentation of FTC is often dominated by local compression or metastatic disease. Bone metastases may manifest with pain, palpable masses, or pathological fractures, whereas lung metastases can present with cough, sputum production, or dyspnea[7]. The clinical manifestations of MSO are nonspecific. Retrospective studies indicate that many patients are asymptomatic, with tumors incidentally discovered during routine imaging or surgery[17]. When symptoms occur, they often resemble those of other ovarian tumors, such as abdominal pain, pelvic mass, ascites, or abnormal uterine bleeding, as well as symptoms related to distant metastasis[17]. Additionally, 5%-8% of patients may experience thyroid dysfunction[11,18].

For thyroid disease, ultrasound is the preferred imaging modality for evaluating nodules, and fine-needle aspiration cytology remains the diagnostic gold standard[19]. Evaluation of thyroid function is necessary. It typically includes thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), free thyroxine, free triiodothyronine, anti-thyroid peroxidase antibodies, and anti-thyroglobulin (Tg) antibodies[20]. In MSO, laboratory findings are nonspecific. When associated with thyrotoxicosis, laboratory findings of MSO may include suppressed TSH, elevated Tg, and increased free triiodothyronine/free thyroxine levels. This is similar to the findings in patients with primary hyperthyroidism[21]. Imaging studies suggest the presence of ovarian struma, but cannot provide a differential diagnosis. Struma ovarii usually appears as a solid mass with smooth margins and multicyclic components. On CT, cystic regions appear hyperdense, with approximately half showing contrast enhancement of the cyst wall[22]. On MRI, solid portions enhance significantly, while cystic contents typically show low to intermediate signal on T1 and low signal on T2[23]. Distant metastases from MSO share imaging features with thyroid carcinoma metastases, appearing as irregular or rounded soft-tissue nodules of variable size. Definitive diagnosis of MSO, therefore, relies on histopathological evaluation of surgical specimens.

At present, there is a lack of consensus regarding the standard treatment protocol for MSO. Surgical resection remains the mainstay, ranging from ovarian cystectomy to salpingo-oophorectomy, hysterectomy, and excision of metastatic foci, depending on patient age and fertility considerations[24]. Combination chemotherapy has shown limited benefit, distinguishing MSO from other malignant germ cell tumors[25]. In addition to surgical treatment, some authors advocate thyroidectomy and postoperative I-131 therapy, treating it as thyroid cancer even when the thyroid is unaffected[26,27]. However, due to insufficient long-term follow-up data, the long-term efficacy of this treatment for MSO remains un

Prognosis of FTC is poorer than that of papillary thyroid carcinoma and depends on patient age, tumor size, stage, completeness of resection, response to radioiodine, and the extent of vascular invasion[29]. In contrast, struma ovarii generally carries a favorable overall prognosis. No clear correlation has been demonstrated between surgical strategy and progression-free survival[13]. Reports suggest that maintaining TSH in the lower normal range may improve patient survival[30]. Additionally, elevated serum Tg and Tg antibody serve as useful markers for recurrence and metastasis, similar to thyroid cancer[30]. Therefore, regular surveillance in accordance with thyroid cancer guidelines is recom

We report a rare case of rectal thyroid-like follicular carcinoma, most likely arising from malignant transformation of struma ovarii. This report reviews the clinical manifestations, pathological features, treatment strategies, and prognostic outcomes associated with both FTC and struma ovarii. Our findings aim to serve as a useful reference for clinicians in the diagnosis and management of similar cases in the future.

| 1. | Staubitz JI, Musholt PB, Musholt TJ. The surgical dilemma of primary surgery for follicular thyroid neoplasms. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019;33:101292. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Parameswaran R, Shulin Hu J, Min En N, Tan WB, Yuan NK. Patterns of metastasis in follicular thyroid carcinoma and the difference between early and delayed presentation. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2017;99:151-154. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ostör G, Tóth I, Hrubyné Tóth Z, Bazsa S. [Cystic struma ovarii, a rare form of ovarian tumor--case report, and review of the literature]. Orv Hetil. 2007;148:2285-2287. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Wolff EF, Hughes M, Merino MJ, Reynolds JC, Davis JL, Cochran CS, Celi FS. Expression of benign and malignant thyroid tissue in ovarian teratomas and the importance of multimodal management as illustrated by a BRAF-positive follicular variant of papillary thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2010;20:981-987. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Doganay M, Gungor T, Cavkaytar S, Sirvan L, Mollamahmutoglu L. Malignant struma ovarii with a focus of papillary thyroid cancer: a case report. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2008;277:371-373. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Dardik RB, Dardik M, Westra W, Montz FJ. Malignant struma ovarii: two case reports and a review of the literature. Gynecol Oncol. 1999;73:447-451. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Boucai L, Zafereo M, Cabanillas ME. Thyroid Cancer: A Review. JAMA. 2024;331:425-435. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 343] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Haigh PI. Follicular thyroid carcinoma. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2002;3:349-354. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Yamazaki H, Sugino K, Katoh R, Matsuzu K, Kitagawa W, Nagahama M, Saito A, Ito K. Management of follicular thyroid carcinoma. Eur Thyroid J. 2024;13:e240146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Siegel MR, Wolsky RJ, Alvarez EA, Mengesha BM. Struma ovarii with atypical features and synchronous primary thyroid cancer: a case report and review of the literature. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2019;300:1693-1707. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Zhu Y, Wang C, Zhang GN, Shi Y, Xu SQ, Jia SJ, He R. Papillary thyroid cancer located in malignant struma ovarii with omentum metastasis: a case report and review of the literature. World J Surg Oncol. 2016;14:17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Chan SW, Farrell KE. Metastatic thyroid carcinoma in the presence of struma ovarii. Med J Aust. 2001;175:373-374. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Asaturova A, Magnaeva A, Tregubova A, Kometova V, Karamurzin Y, Martynov S, Lipatenkova Y, Adamyan L, Palicelli A. Malignant Clinical Course of "Proliferative" Ovarian Struma: Diagnostic Challenges and Treatment Pitfalls. Diagnostics (Basel). 2022;12:1411. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Schmidt J, Derr V, Heinrich MC, Crum CP, Fletcher JA, Corless CL, Nosé V. BRAF in papillary thyroid carcinoma of ovary (struma ovarii). Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:1337-1343. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Tate G, Tajiri T, Suzuki T, Mitsuya T. Mutations of the KIT gene and loss of heterozygosity of the PTEN region in a primary malignant melanoma arising from a mature cystic teratoma of the ovary. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2009;190:15-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Tondi Resta I, Sande CM, LiVolsi VA. Neoplasms in Struma Ovarii: A Review. Endocr Pathol. 2023;34:455-460. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Yoo SC, Chang KH, Lyu MO, Chang SJ, Ryu HS, Kim HS. Clinical characteristics of struma ovarii. J Gynecol Oncol. 2008;19:135-138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Makani S, Kim W, Gaba AR. Struma Ovarii with a focus of papillary thyroid cancer: a case report and review of the literature. Gynecol Oncol. 2004;94:835-839. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Alexander EK, Cibas ES. Diagnosis of thyroid nodules. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2022;10:533-539. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 134] [Article Influence: 33.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Durante C, Hegedüs L, Czarniecka A, Paschke R, Russ G, Schmitt F, Soares P, Solymosi T, Papini E. 2023 European Thyroid Association Clinical Practice Guidelines for thyroid nodule management. Eur Thyroid J. 2023;12:e230067. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 228] [Article Influence: 76.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Matsuda K, Maehama T, Kanazawa K. Malignant struma ovarii with thyrotoxicosis. Gynecol Oncol. 2001;82:575-577. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Jung SI, Kim YJ, Lee MW, Jeon HJ, Choi JS, Moon MH. Struma ovarii: CT findings. Abdom Imaging. 2008;33:740-743. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Yamauchi S, Kokabu T, Kataoka H, Yoriki K, Takahata A, Mori T. Computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, and positron emission tomography/computed tomography findings for the diagnosis of malignant struma ovarii: A case report. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2023;49:1456-1461. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Rosenblum NG, LiVolsi VA, Edmonds PR, Mikuta JJ. Malignant struma ovarii. Gynecol Oncol. 1989;32:224-227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Ukita M, Nakai H, Kotani Y, Tobiume T, Koike E, Tsuji I, Suzuki A, Mandai M. Long-term survival in metastatic malignant struma ovarii treated with oral chemotherapy: A case report. Oncol Lett. 2014;8:2458-2462. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Gild ML, Heath L, Paik JY, Clifton-Bligh RJ, Robinson BG. Malignant struma ovarii with a robust response to radioactive iodine. Endocrinol Diabetes Metab Case Rep. 2020;2020:19-0130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | DeSimone CP, Lele SM, Modesitt SC. Malignant struma ovarii: a case report and analysis of cases reported in the literature with focus on survival and I131 therapy. Gynecol Oncol. 2003;89:543-548. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | McGill JF, Sturgeon C, Angelos P. Metastatic struma ovarii treated with total thyroidectomy and radioiodine ablation. Endocr Pract. 2009;15:167-173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Sobrinho-Simões M, Eloy C, Magalhães J, Lobo C, Amaro T. Follicular thyroid carcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2011;24 Suppl 2:S10-S18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Deng J, Ng YHG, Chew SH, Lim YK. Metastatic follicular carcinoma arising from struma ovarii. BMJ Case Rep. 2022;15:e247697. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/