Published online Feb 15, 2026. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v18.i2.113995

Revised: October 23, 2025

Accepted: December 10, 2025

Published online: February 15, 2026

Processing time: 147 Days and 18.4 Hours

Gastric cancer remains a leading cause of global cancer mortality, with limited advances in its prevention and treatment owing to an incomplete understanding of its pathogenesis. Among the key precancerous lesions, spasmolytic polypep

Core Tip: Gastric cancer is one of the most common cancers worldwide, with exceptionally high morbidity and fatality rates. A thorough investigation of the pathophysiology of spasmolytic polypeptide-expressing metaplasia (SPEM) is required. SPEM serves as a critical nexus between mucosal repair and gastric carcinogenesis and is a valuable target for early detection and intervention. To gain a deeper understanding of SPEM, this review summarizes its recent mechanistic roles in gastric mucosal diseases. By elucidating these mechanisms, this review aims to provide deeper insights into the research and prevention of SPEM-related diseases.

- Citation: Yang RR, Yan YR, Li YF. Recent advances in spasmolytic polypeptide expressing metaplasia research. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2026; 18(2): 113995

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v18/i2/113995.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v18.i2.113995

Spasmolytic polypeptide-expressing metaplasia (SPEM) is an adaptive metaplastic cell lineage that develops in the gastric mucosa in response to injury. Although traditionally regarded as a reparative program, its strong association with gastric cancer development has led to SPEM redefinition as a critical precursor lesion and an important target for its prevention. Gastric cancer is a major global health burden and ranks as the fifth most common malignancy worldwide in terms of both incidence and mortality[1]. Its development often follows the classic Correa cascade, a multistep progression from normal gastric mucosa to invasive carcinoma through chronic gastritis, atrophic gastritis, intestinal metaplasia (IM), and dysplasia stages[2]. Throughout this process, persistent atrophy and inflammation drive the development of metaplastic lesions such as SPEM and IM, which are recognized as precancerous conditions. Consequently, SPEM is regarded as a key target for the prevention and control of gastric cancer.

The stomach epithelium exhibits considerable self-renewal capacity and cellular plasticity, enabling periodic differentiation and dedifferentiation of gastric epithelial cells, a property that inherently increases the susceptibility to carcinogenesis[3]. Under acute or chronic inflammatory conditions, parietal cell loss from the normal gastric mucosa marks the onset of oxyntic atrophy, which is a prerequisite for the emergence of SPEM[4]. Beyond parietal cell loss, depletion of chief cells has also been identified as an initiating factor in gastric mucosal injury[5,6].

SPEM concept emerged from observations of aberrant epithelial lineages in Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori)-infected mice[7], and is now recognized as an adaptive, repair-oriented cellular conversion. SPEM is characterized by the expression of trefoil factor 2 (TFF2) and mucin 6 (MUC6)[8,9]. In contrast, IM is generally regarded as the outcome of transdifferentiation toward an intestinal phenotype, featuring the presence of MUC-containing goblet cells, Paneth cells, and absorptive enterocytes, along with TFF3 and MUC2 expression[10]. SPEM is typically located deep in the fundic gland. In contrast, IM is present in the gland lumen, and evidence suggests that IM likely evolves from SPEM[4,11]. Consequently, SPEM and IM detection in clinical specimens is crucial for risk stratification and early intervention in gastric cancer.

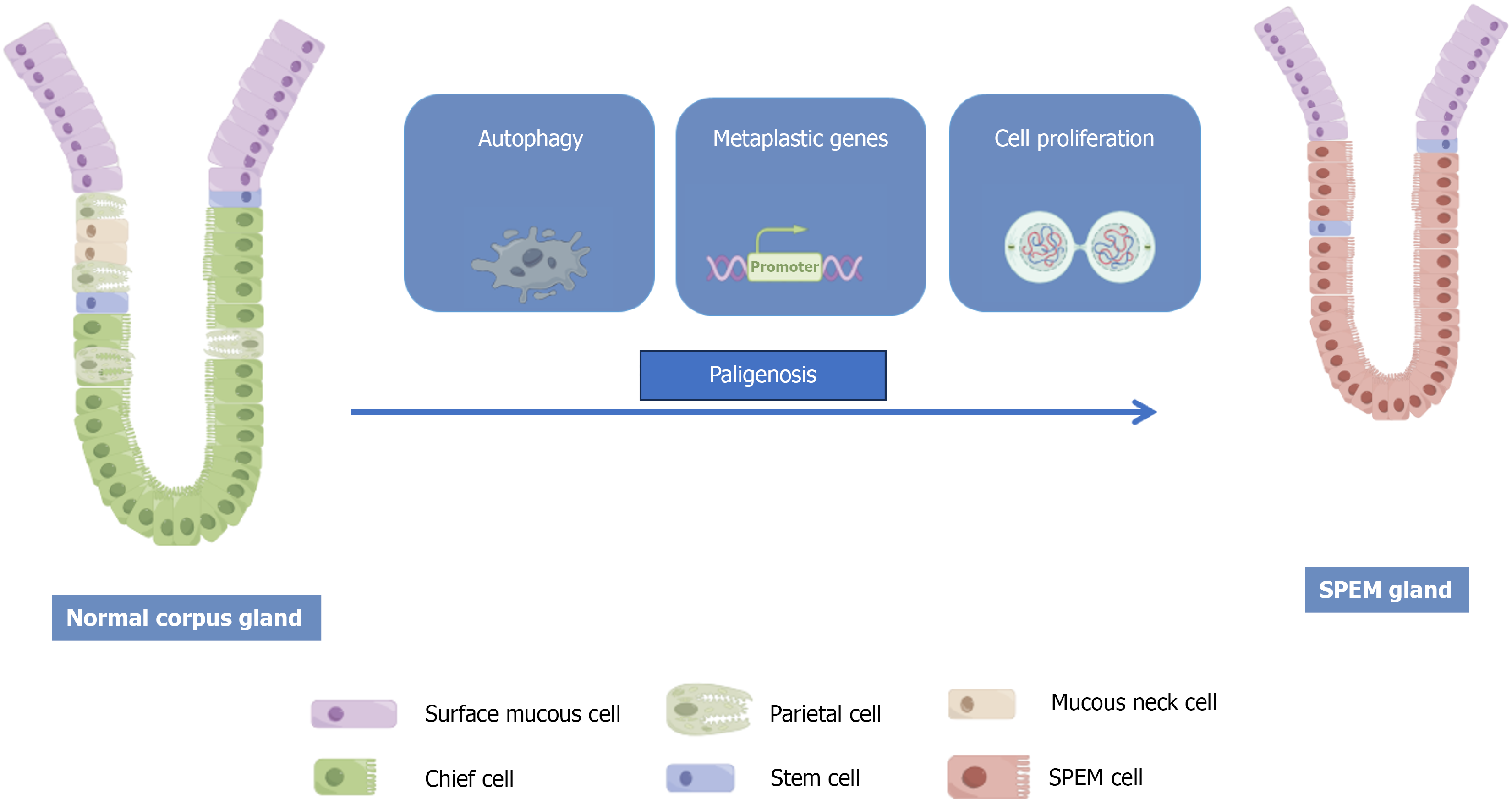

The cellular origin of SPEM, which is central to understanding its initiation, is the subject of active investigation and debate. While the predominant model centers on the transdifferentiation of mature chief cells, emerging evidence suggests alternative cellular sources that highlight the plasticity of the gastric epithelium. Cell differentiation is the developmental mechanism by which a cohort of multipotent progenitors gives rise to diverse specialized cell lineages, each with unique morphological and functional properties[3]. In the stomach, tissue repair after injury involves reprogramming fully differentiated cells back into a less-differentiated proliferative state to replenish lost cells. Pathologists refer to this stereotypical cycle of cellular phenotypic changes as paligenosis.

The cellular origin of SPEM has not been fully determined; however, the most widely accepted explanation is that it arises from the transdifferentiation of mature chief cells[12], also known as pyloric metaplasia, which is histologically defined by the luminal proliferation of MUC5AC-positive cells, concurrent with parietal cell loss and replacement of chief cells by basally emerging SPEM cells[7]. Through an evolutionarily conserved process termed “paligenosis”, mature gastric chief cells can be reprogrammed, re-enter the cell cycle, and transform into SPEM cells (Figure 1)[13].

A preliminary exploration of the process of chief cell transdifferentiation into SPEM cells has been reported. This process begins with the dedifferentiation of chief cells, which is marked by the key molecular event of muscle, intestine, stomach expression 1 (MIST1) downregulation[14]. This process begins with the disruption of normal cellular mor

In the early stages of pathogenesis, activating transcription factor 3 is upregulated, which induces autophagy and lysosomal activity to dismantle the characteristic structures of differentiated chief cells[16]. Chief cell reprogramming is initiated by sulforaphane (Sfn)[17] and is accompanied by MIST1 downregulation[14] and upregulation of aquaporin 5 (AQP5)[18] and SRY-Box transcription factor 9 (SOX9)[19]. Notably, SFN loss in chief cells abrogates SOX9 expression. SOX9 itself is also known to promote metaplasia in Barrett’s esophagus[20].

In the later stages, transdifferentiated cells begin to produce cytoplasmic granules expressing TFF2 or MUC6, a process facilitated by interleukin (IL)-13[3,21]. The concurrent shrinkage of zymogen granules and the upregulation of MUC granule formation are likely associated with the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS). ROS function as inducible upstream signals in pathogenesis and are essential for normal progression. Furthermore, both acute and chronic inflammation can increase cellular ROS levels[22]. In response to oxidative stress, cells activate the CD44v9-xCT pathway[23]. Ultimately, downregulation of DNA damage induced transcript 4 (DDIT4) allows SPEM cells to reactivate mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) complex 1 signaling, thereby acquiring a proliferative phenotype[24,25].

SPEM development is influenced by factors beyond epithelial cells, particularly dynamic interactions with the underlying mesenchyme (stroma). However, the specific role of the stroma in the progression of precancerous gastric lesions remains unclear. Evidence suggests that telocytes, a specialized type of mesenchymal cell, may drive metaplastic progression by secreting signaling molecules, such as Wnt and bone morphogenetic protein (BMP), thereby providing critical microenvironmental support for epithelial cells undergoing phenotypic changes[26]. The Wnt pathway is known for its key role in gastric development and regeneration, whereas BMP signaling has been implicated in the differentiation of both gastric and intestinal epithelial cells[27,28]. Furthermore, fibroblasts have been identified as the key promoters of direct carcinogenesis in SPEM cells[29].

Besides the stromal influences, the SPEM cellular origin is an area of active research. An alternative hypothesis posits that neck and progenitor cells located in the glandular isthmus also give rise to SPEM[30-32]. This suggests that chief cells are not the only cells capable of undergoing paligenosis. Notably, parietal cell precursors, which are derived from isthmus stem cells, highly express the orphan nuclear receptor gene estrogen-related receptor gamma. Deficiency in estrogen-related receptor gamma leads to impaired parietal cell differentiation, a disruption that may indirectly facilitate SPEM development[33].

SPEM emerges in inflammatory, atrophic, and precancerous lesions as an initial response to diffuse gastric injury, representing the reprogramming of the epithelium towards a proliferative, reparative state[34]. Morphologically, SPEM is characterized by the transdifferentiation of zymogen-secreting chief cells into mucus-producing cells, which constitutes a key mucosal repair mechanism[35]. Although this response is initially adaptive, persistent inflammatory insult can lead to repeated repair cycles, thereby increasing the risk of neoplastic progression.

Inflammation is the primary trigger for this cascade, with H. pylori infection being the predominant risk factor. H. pylori activates the expression of numerous inflammatory mediators, promoting immune cell infiltration, oxidative stress, and aberrant epithelial proliferation[36]. A critical virulence factor for its survival and pathogenicity is lipopolysaccharide[37]. Lipopolysaccharide can downregulate protective cytokines, such as IL-33, impair mucosal repair[38], and induce excessive ROS accumulation, leading to DNA damage and epithelial cell death[39].

The gastric epithelium responds to such injuries through cellular plasticity, a fundamental adaptive process that balances damage and repair. Plasticity is a prerequisite for SPEM development. The nature of the epithelial response depends on the injury pattern. Localized injury often results in altered differentiation, marked by Tff2 expression and Sox9 upregulation[40], whereas diffuse injury typically triggers the full SPEM program. Notably, SPEM predominantly arises following oxyntic gland atrophy and loss of parietal cells[41]. While epithelial cells exhibit varying sensitivities to inflammatory signals, interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) has been established as a key driver that induces parietal cell atrophy, initiating the sequence of events leading to metaplasia[42,43].

Inflammation is a requisite driver for the progression of SPEM towards a more aggressive phenotype[44]. H. pylori can exploit this process to expand its ecological niche within the gastric mucosa[45]. Within the inflammatory milieu, the immune cells and their secreted cytokines are central to SPEM development. For instance, the activation of IL-33 and M2-type macrophages at the injury site is critical for SPEM progression[44,46,47].

At the molecular level, lineage markers upregulation, such as TFF2 and MUC6[34], along with CD44v9, helps mitigate ROS-induced oxidative stress[48]. Changes in CD44v9 expression are also linked to the downregulation of miR-148a, a potential regulator of cell fate determination[49]. Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) signaling pathway role in gastric mucosal differentiation is well-established; however, the specific functions of its ligands - including transforming growth factor-α, amphiregulin, and heparin-binding epidermal growth factor-like growth factor - in SPEM remain understudied[50]. A recent study using a mouse model of acute parietal cell atrophy induced by DMP-777 demonstrated that SFN promotes mucosal repair by activating the EGFR/extracellular signal-regulated kinase pathway, thereby mediating the transdifferentiation of chief cells into SPEM cells, a process accompanied by upregulation of the AQP5 water channel[17].

When the gastric mucosa develops IM, which is characterized by the appearance of intestinal goblet cells[51], SPEM can persist in the basal layer of the incomplete IM. This subtype is associated with a high risk of gastric carcinogenesis. SPEM is widely considered a key precursor of gastric cancer. Persistent SPEM cells, under the combined pressure of a chronic inflammatory microenvironment, genetic alterations, and epigenetic dysregulation, can progressively accumulate oncogenic mutations, ultimately leading to invasive carcinoma[52,53].

In summary, SPEM is a crucial repair response to gastric mucosal injury that aims to restore epithelial integrity through cellular reprogramming. However, when driven by persistent insults such as H. pylori infection, glandular atrophy, and microenvironmental dysregulation, this reparative mechanism can become dysregulated. Instead of restoring homeostasis, they may initiate a pathogenic sequence that begins with metaplasia and progresses to precancerous lesions and cancer.

Owing to the inherent limitations in studying the pathogenesis and interventions directly in humans, mouse models have become indispensable for investigating spasmolytic SPEM and gastric precancerous progression. Their physiological relevance to humans, coupled with established genetic tools and cost-effectiveness, makes them a tractable and widely adopted system. Its key advantages include experimental controllability and phenotypic uniformity. Through genetic engineering, researchers can precisely manipulate gene expression or cell lineages in vivo, enabling the systematic observation of gastric mucosal changes and establishing clear causal links between molecular perturbations and histological phenotypes. Commonly utilized SPEM models fall into three categories: (1) The H. pylori infection-induced SPEM model, which recapitulates chronic inflammation-driven pathogenesis; (2) Acute chemical injury-induced SPEM models, which probe SPEM origins during repair and regeneration; and (3) Genetically engineered models that directly test molecular mechanisms by activating or deleting specific genes. The models used are listed in Table 1[8,54-73].

| Mouse model | SPEM | SPEM for proliferation capacity | Intestinal metaplasia | Inflammatory infiltrate | Invasive glandular production | Intestinalized |

| H. pylori infection-induced SPEM models | ||||||

| Helicobacter felis or H. pylori infection[54-57] | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Acute chemical injury induced SPEM models | ||||||

| DMP-777 treatment[8,54,56,58] | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| L635 treatment[54-56] | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| High-dose tamoxifen treatment[59,60] | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| Genetically engineered mouse models | ||||||

| SOX9 overexpression mice[61] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| LKB1/PTEN deficient mice[62] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Gastrin-deficient mice[63] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| IL-1β transgenic mice[64] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| H/K-IFN-γ transgenic mice[65] | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Conditional K-Ras activation mouse[66,67] | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| AR knockout mice[68] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Mist1-Kras mice[69,70] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| TGFα transgenic mice (MT-TGFα or Doxi-TGFα)[71-73] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Animal models are indispensable for investigating the pathogenesis and identifying potential therapeutic targets. However, these models cannot fully recapitulate the complexity of human diseases; therefore, their findings require validation in clinical studies. For instance, H. pylori infection can successfully establish a mouse model of SPEM, and lesions have also been identified in humans[57]. Mouse models offer a tractable platform for the systematic study of the multistep pathogenesis. Crucially, studies in mice have demonstrated that SPEM is reversible[68]; direct evidence in humans remains limited, although eradicating H. pylori may halt its progression, particularly in the early stages[73]. The reversibility of IM is still debated. Therefore, advancing gastric cancer prevention requires an integrated strategy. Mouse models provide mechanistic insights and identify therapeutic candidates, as demonstrated by the signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) inhibitor STA-21, which limits early metaplasia[74]. These findings must then be validated in clinically relevant human models, such as patient-derived gastric organoids, to confirm their efficacy, as exemplified by luteolin reversing premalignant lesions (SPEM/IM)[75], and to accelerate clinical translation.

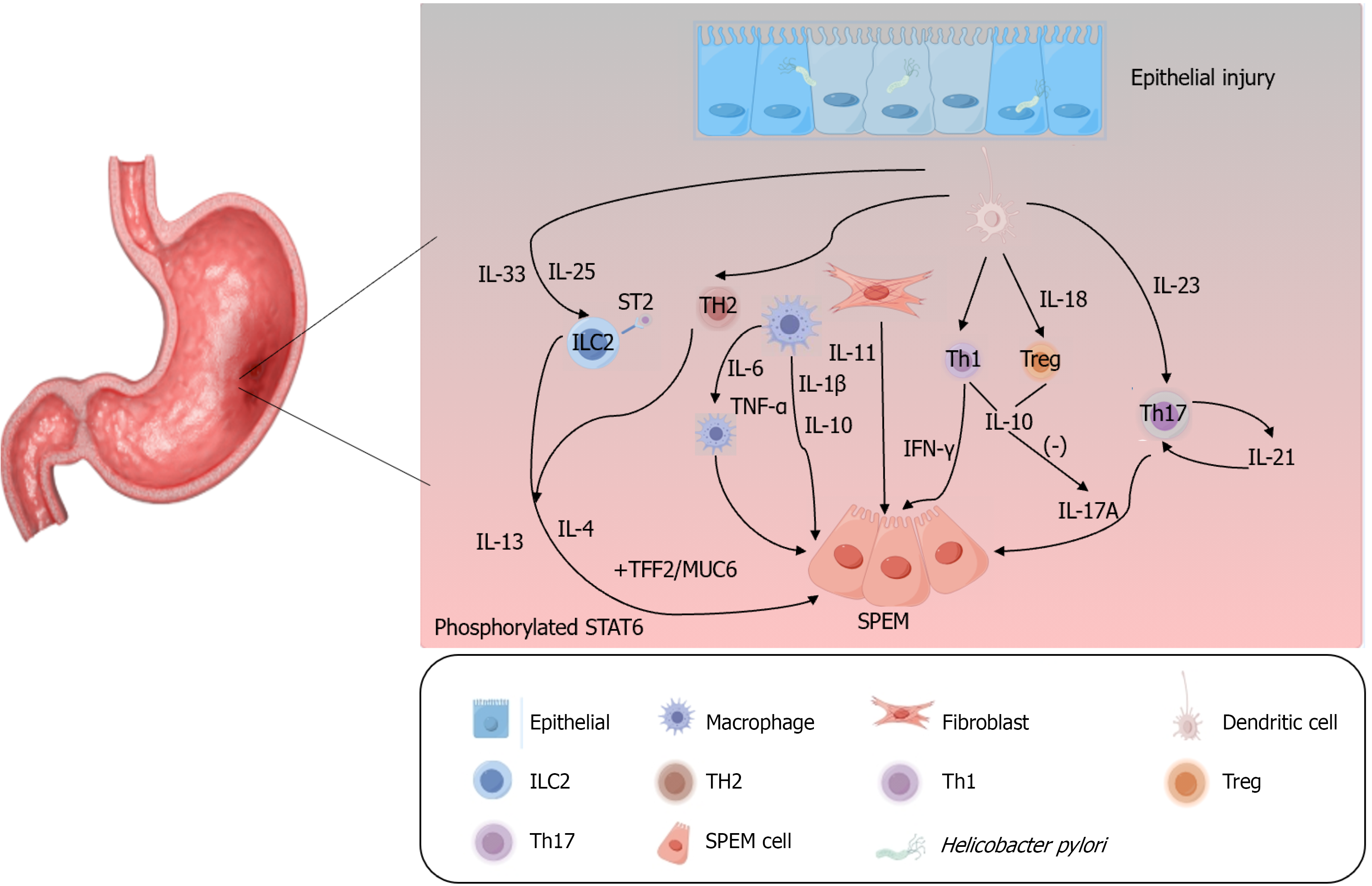

Cytokines play a pivotal role in shaping the tumor microenvironment, orchestrating the initiation and progression of SPEM, and significantly promoting gastric cancer development[76]. Chronic inflammation represents the initial step in diffuse gastric cancer[77] with common etiologies including autoimmune responses (accompanied by the involvement of multiple cytokines) and H. pylori infection, both of which lead to parietal cell atrophy and SPEM[42,78,79]. Inflammatory cytokines act as auxiliary signals following parietal cell loss and are critical for SPEM induction and progression[80]. H. pylori infection elicits the release of numerous cytokines, such as IL-1β, IL-6, IL-17, IFN-γ, and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α)[81]. These include pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-6, IFN-γ) and anti-inflammatory cytokines (IL-10, IL-18). An imbalance between these subsets disrupts inflammatory processes, thereby contributing to metaplasia and tumorigenesis[82]. As a key component of type I immune responses, IFN-γ fosters an inflammatory milieu and serves as a major driver of SPEM development[42,43]. IL-17A, a canonical pro-inflammatory cytokine primarily secreted by T helper 17 (Th17) cells, is regulated by IL-23, a critical factor for Th17 cell differentiation and maintenance. IL-10, released by regulatory T (Treg) cells, inhibits Th17-induced inflammation; the Th17/Treg balance sustains gastric mucosal immune homeostasis while potentially promoting persistent inflammation[76,83]. H. pylori modulates immune escape mechanisms and polarizes dendritic cells (DCs) to secrete IL-23, which induces and maintains Th17 cells. The subsequent secretion of IL-17 and IL-21 by Th17 cells amplifies the Th17 response via IL-21-mediated positive feedback[84]. Additionally, IFN-γ and IL-17A directly induce gastric epithelial cell death, which is essential for subsequent parietal cell atrophy and SPEM progression[42,79]. TNF-α, a pro-inflammatory cytokine secreted by macrophages, activates multiple inflammation-related downstream signaling pathways and enhances gastric cancer cell metastasis[85,86]. While the precise mechanism of IL-1β in gastric cancer remains elusive, existing data indicate that IL-1β acts as a key mediator of inflammatory responses, contributing to gastric precancerous lesions and suppressing gastric acid secretion, thereby facilitating gastric cancer development[81,87]. IL-6, a pleiotropic cytokine that acts primarily via the IL-6/STAT3 pathway, contributes to both inflammation and gastric cancer progression and promotes M2 macrophage polarization[88,89]. M2 macrophages play critical roles in gastric cancer progression and participate in angiogenesis, tumor invasion, metastasis, and the

Notably, IL-33, a member of the IL-1 family, plays a crucial role in driving SPEM as emphasized in recent studies[21,77,92,93]. IL-13 is also important for the maturation and proliferation of SPEM cells[21]. Type II immune responses have been implicated as key contributors to epithelial metaplasia, with IL-33 identified as a critical inducer and type II cytokines (IL-4 and IL-13) as major drivers[77,78]. IL-33 release and signaling trigger the upregulation of type 2 inflammatory cytokines, including IL-4 and IL-13[94]. IL-13 not only serves as a key regulator of SPEM cell generation but also promotes the maturation and proliferation of SPEM lineages[21,93]. Type 2 innate lymphoid cells play a vital role in the IL-33/IL-13 axis by initiating the release of IL-13 and IL-4, activating mast cells, and promoting M2 macrophage pola

Other IL-1 family members also modulate SPEM activity. IL-36 triggers the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-12, fostering a chronic inflammatory environment that perpetuates a cycle of mucosal damage and repair, thus sustaining SPEM. It can also enhance the invasive and metastatic potential of gastric cancer. Conversely, IL-38 effectively counteracts the pro-inflammatory effects of IL-36[95,96]. Given their shared family affiliations, it is plausible that IL-36 and IL-33 act synergistically to coactivate the IL-13 pathway, thereby promoting the transdifferentiation of chief cells and contributing to the initial formation of SPEM.

Besides cytokine networks, the Hippo pathway effector Yes-associated protein (YAP) is implicated in metaplastic progression. Analysis of human gastric tumor tissue revealed that nuclear YAP and HE4 expression was upregulated in metaplastic regions[97]. Both YAP and HE4 were highly expressed in SPEM and IM, suggesting that YAP activation may promote the development of these precancerous lesions, potentially through the positive regulation of SPEM-related genes such as HE4. Immune regulation also plays a counterbalancing role. In autoimmune gastritis, IL-27 has been identified as an inhibitor of CD4+ T cell-mediated inflammation in the gastric mucosa, thereby exerting a protective effect against gastritis and SPEM[46].

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are endogenously expressed noncoding RNAs that post-transcriptionally regulate gene expression by binding to target mRNAs through sequence complementarity. They play pivotal roles in a wide array of biological processes, including cell development, differentiation, and proliferation[98-101]. The dysregulation of specific miRNAs has been implicated in gastric carcinogenesis. In SPEM, miRNAs, such as miR-21, miR-155, and miR-223, were upregulated, whereas miR-148a was downregulated. Downregulation of miR-148a may be a key event in the initiation of chief cell reprogramming[102]. During IM, lesions are influenced by other miRNAs, including miR-1, miR-30, miR-194, and miR-490[103].

A notable example is miR-30a, which is highly expressed in mucus neck cells and chief cells of normal gastric tissue in both mice and humans. However, its expression is significantly downregulated in mouse models of SPEM and IM (induced by DMP-777 or L635), including in human clinical samples of these lesions. This downregulation was observed in both GSII-positive SPEM and GSII-negative IM tissues. Reduced miR-30a levels have also been observed in human gastric cancer cells, suggesting its potential role as an early biomarker and therapeutic target to prevent gastric carcinogenesis[101,104].

Furthermore, downregulation of miR-7 has been identified as an early event in the metaplasia-carcinoma sequence. In SPEM tissues, decreased miR-7 expression was associated with the upregulation of TFF2[105]. From a therapeutic perspective, a study found that 18β-glycyrrhetinic acid suppresses proliferation, induces cell cycle arrest, and promotes apoptosis in gastric cancer cells. This compound acts by regulating the miR-328-3p/STAT3 signaling pathway and promoting autophagic flux, highlighting a potential novel pharmacological strategy for gastric cancer treatment[100].

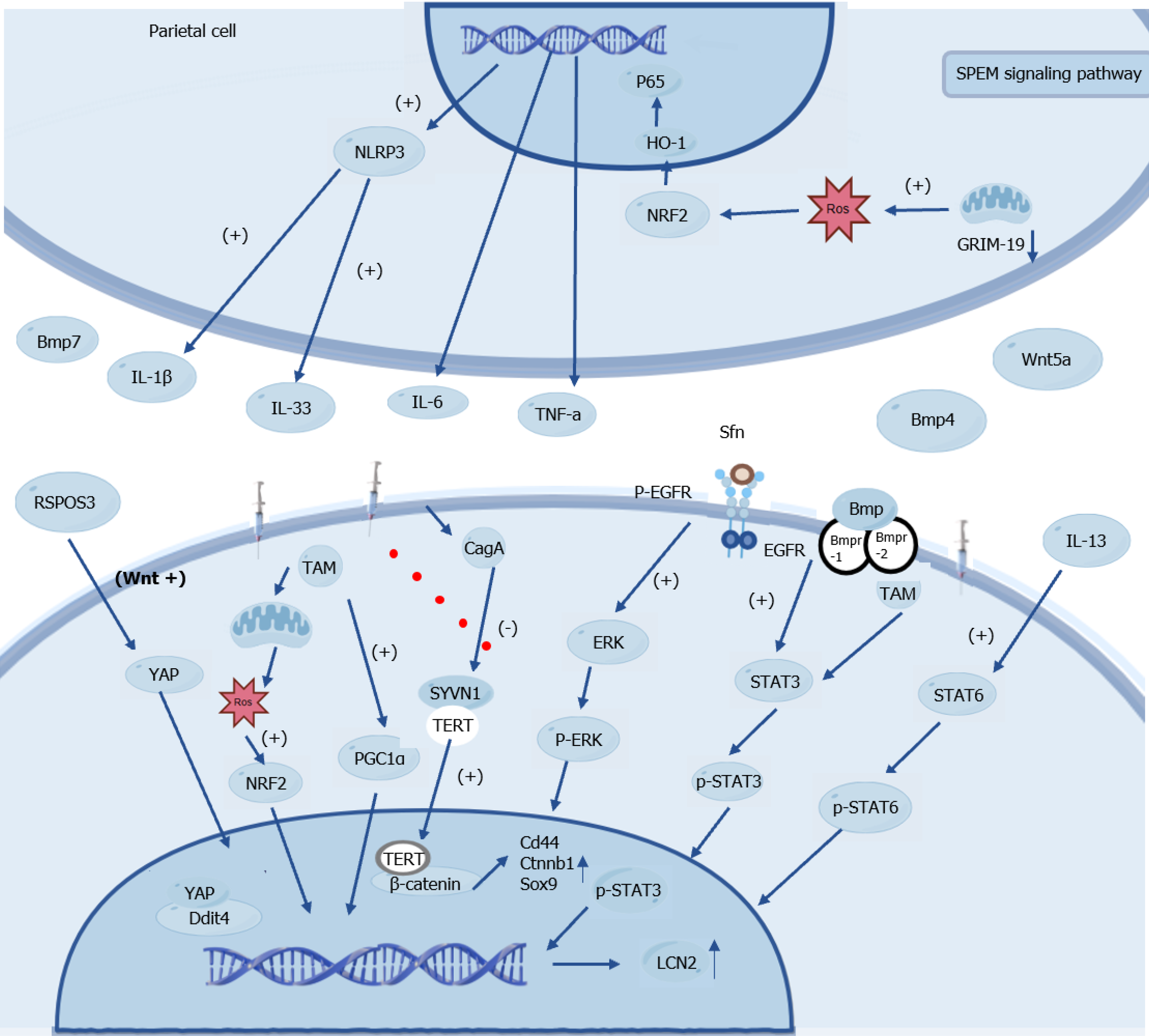

Research into the molecular mechanisms of SPEM has revealed a highly interconnected regulatory network, with key signaling pathways - including STAT3, nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB), mTOR, and Wnt/β-catenin - synergistically driving the phenotypic transformation of gastric epithelial cells to promote SPEM development and maintenance (Figure 3).

Wnt proteins are secreted glycoproteins whose core effector, β-catenin, plays crucial roles in cell adhesion and gene transcription[106,107]. The Wnt signaling pathway plays a pivotal role in gastric development and homeostasis. H. pylori infection can upregulate AQP5 via its virulence factor cytotoxin-associated gene A, which in turn leads to aberrant activation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway. This activation not only drives the progression of gastritis but also serves as a key mechanism inducing host cell dedifferentiation and SPEM formation[57,108].

During this process, ROS act as key signaling molecules. On one hand, ROS can further activate the Wnt/β-catenin pathway to mediate hyperproliferation[109]. Conversely, chief cells can employ the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma co-activator-1 alpha-xCT-glutathione peroxidase 4 axis to regulate mitochondrial activity and manage ROS levels; a failure in ROS clearance impedes SPEM development and promotes cell death[22]. Telocytes within the microenvironment secrete signaling molecules such as Wnt5a, Bmp4, and Bmp7[26]. Substantial evidence indicates that sustained activation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway is closely associated with gastric cancer development, progression, and invasiveness of gastric cancer. The drug nitazoxanide effectively mitigates SPEM by inhibiting this pathway, providing an experimental basis for its potential as a therapeutic strategy[57,110].

The mTOR signaling pathway is involved in the development of pathogenesis. Its activity is regulated by key factors including Ddit4 and the transcription factor Sox9, which coordinate cell cycle progression to drive cellular repro

R-spondin 3, a Wnt signaling enhancer known to regulate stem cell behavior in various organs[112,113], transiently activates YAP to promote regeneration after acute injury. However, during chronic H. pylori infection, sustained R-spondin 3 overexpression synergizes with signaling pathways such as mTOR and cytokines such as IL-33, driving glandular hyperplasia and the development of precancerous lesions and demonstrating long-range regulatory capabilities[114].

The NF-κB signaling pathway serves as a central regulator of innate and adaptive immunity and is extensively involved in controlling cell proliferation, apoptosis, migration, invasion, and inflammatory responses. It is primarily activated via the canonical pathway and plays a key role in gastric mucosal lesion development[115]. Studies have shown that deletion of the mitochondrial protein gene associated with retinoid-IFN-induced mortality 19 in parietal cells triggers SPEM formation via the ROS-NF-κB axis. This process depends on IκB degradation and p65 nuclear translocation, mediated by the IKK kinase complex, in which the catalytic subunit IKKα serves as a core signaling component. The resulting aberrant NF-κB activation induces the release of inflammatory factors such as IL-6 and TNF-α, and cooperates with the NLR family pyrin domain-containing 3/IL-33 pathway to promote SPEM development[116,117]. Additionally, miR-130b plays a central role in driving gastric metaplasia by activating the NF-κB pathway[118]. The Mongolian gerbil H. pylori infection model further confirmed that SPEM lesion formation is closely associated with sustained activation of the NF-κB pathway[119].

STAT3 is a key transcription factor linking chronic inflammation to gastric tumorigenesis. Upon H. pylori infection, cytokines, such as IL-6 and IL-11, bind to their receptors and trigger STAT3 phosphorylation at tyrosine 705. Phosphorylated STAT3 (p-STAT3) dimerizes and translocates to the nucleus, where it activates the transcription of genes involved in proliferation, apoptosis, and invasion. STAT3 signaling evolves from transient activation in early infection to sustained activation in tumors, driving the progression of gastric mucosal lesions and correlating with poor prognosis[120-122]. Concurrently, high expression levels of IL-6, p-STAT3, and Ki67 have been observed in SPEM lesions[123]. Aberrant STAT3 activation interacts with multiple regulatory mechanisms; for example, the inhibition of BMP signaling exacerbates inflammation and promotes SPEM through STAT3 upregulation[124]. In the DMP-777 mouse model, evidence suggests that SFN may engage the STAT3 pathway during the later stages of carcinogenesis[17]. Activated Ras is involved in the development of metaplasia in Mist1-Kras mouse principal cells[69]. IL-13 directly promotes SPEM cell proliferation and maturation via the STAT6 pathway[21].

Th17 cells play a significant role in autoimmune diseases, functioning in balance with Treg cells[125,126]. Tregs are lymphocytes that negatively regulate immune responses[127]. Inflammation is primarily mediated by IFN-γ-producing CD4+ T cells (Th1) and IL-17-producing CD4+ T cells (Th17)[128]. In autoimmune gastritis, STAT3 is a downstream signaling protein required for Th17 cell differentiation, and inhibition of STAT3 restores the Th17/Treg balance, thereby reducing inflammation and limiting early chemotactic changes[74]. A recent study has elucidated the immunosuppressive role of Tregs. Tregs secrete the anti-inflammatory cytokine, IL-13, which subsequently activates the STAT3 signaling pathway in gastric cancer cells through p-STAT3. This IL-13-driven p-STAT3 activation enhances the self-renewal capacity[129]. Furthermore, STAT3 acts synergistically with other oncogenic drivers. It cooperates with activated Ras to promote pathogenic sequences involved in gastric mucosal atrophy, hyperproliferation, and SPEM formation[130]. Its sustained activation can also be fueled by non-inflammatory stimuli such as the accumulation of deoxycholic acid during progression to IM[131].

Luteolin, a natural flavonoid compound widely present in various medicinal plants, has been shown to effectively block activation of the STAT3/Lipocalin 2 oncogenic signaling axis in a tamoxifen-induced mouse model in preclinical studies. Luteolin curbs the progression of metaplastic lesions in vivo by directly binding to STAT3 and inhibiting tyrosine phosphorylation. Luteolin curbs the progression of metaplastic lesions at the model level[75]. This demonstrates that targeted disruption of STAT3 signaling is a viable strategy for intercepting the metaplasia-carcinoma sequence.

The complex, intricate molecular network governing SPEM unveils a strategic roadmap for clinical intervention. Moving beyond a one-size-fits-all approach, we propose a precision defense framework aimed at intercepting the metaplasia-carcinoma sequence at its most vulnerable points. Based on the current understanding of SPEM’s multi-pathway regulatory networks, a stratified interventional framework has emerged. For early detection, the integrated assessment of TFF2/MUC6/CD44v9 protein expression profiles with characteristic miRNA signatures (miR-148a/miR-30a/miR-21) in the gastric mucosa or body fluids enables precise risk stratification of premalignant lesions. Therapeutically, beyond fundamental H. pylori eradication[55], targeting key pathway nodes shows promise as inhibitors of the IL-33/IL-13 axis and STAT3 signaling hub (e.g., luteolin), along with EGFR/extracellular signal-regulated kinase pathway agonists (e.g., SFN), providing targeted chemoprevention against the inflammation-metaplasia cascade. Additional potential targets include the Wnt/β-catenin pathway (modulated by nitazoxanide in preclinical studies), mTOR signaling, and the YAP-DDIT4 axis in cellular dedifferentiation. Implementation requires biomarker-guided patient stratification using markers such as CD44 and p-STAT3. Synthetic lethality strategies that leverage ROS metabolic characteristics and combination therapies represent promising research directions for establishing a comprehensive SPEM management system.

Based on the synthesis of recent advances regarding the cellular origins of SPEM and its key signaling pathways - such as NF-κB, YAP, STAT3, and Wnt/β-catenin - it must be noted that current investigations into these pathways remain incomplete, with a limited number of experimental studies. Nevertheless, these pathways collectively regulate the initiation and progression of SPEM, underscoring the need to prioritize signaling pathway research in future investigative strategies. Accumulating evidence has demonstrated that SPEM is not merely an adaptive repair response of the gastric mucosa to injury, but more importantly, a precancerous lesion that actively promotes gastric carcinogenesis. As a dynamic biological process at the crossroads of regeneration and cancer, SPEM represents a crucial target for early-stage targetable interventions. Therefore, deepening our understanding of SPEM mechanisms is essential for the early detection and prevention of gastric cancer.

I would like to sincerely thank my supervisor, Professor Tai-Peng Tan, for his invaluable guidance, unwavering support, and profound intellectual inspiration throughout this research. His expertise in cancer research and rigorous academic insights were instrumental in shaping this work. I am also grateful for his patience and encouragement, which have greatly facilitated my academic growth. This study would not have been possible without his generous mentorship.

| 1. | Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024;74:229-263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5690] [Cited by in RCA: 12644] [Article Influence: 6322.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (6)] |

| 2. | Li W, Zhang T. Precancerous pathways to gastric cancer: a review of experimental animal models recapitulating the correa cascade. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2025;13:1620756. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Goldenring JR, Mills JC. Cellular Plasticity, Reprogramming, and Regeneration: Metaplasia in the Stomach and Beyond. Gastroenterology. 2022;162:415-430. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 134] [Article Influence: 33.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Goldenring JR, Nam KT, Wang TC, Mills JC, Wright NA. Spasmolytic polypeptide-expressing metaplasia and intestinal metaplasia: time for reevaluation of metaplasias and the origins of gastric cancer. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:2207-2210, 2210.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 153] [Cited by in RCA: 163] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Deng Z, Zhu J, Ma Z, Yi Z, Tuo B, Li T, Liu X. The mechanisms of gastric mucosal injury: focus on initial chief cell loss as a key target. Cell Death Discov. 2023;9:29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Burclaff J, Osaki LH, Liu D, Goldenring JR, Mills JC. Targeted Apoptosis of Parietal Cells Is Insufficient to Induce Metaplasia in Stomach. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:762-766.e7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Schmidt PH, Lee JR, Joshi V, Playford RJ, Poulsom R, Wright NA, Goldenring JR. Identification of a metaplastic cell lineage associated with human gastric adenocarcinoma. Lab Invest. 1999;79:639-646. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Nomura S, Yamaguchi H, Ogawa M, Wang TC, Lee JR, Goldenring JR. Alterations in gastric mucosal lineages induced by acute oxyntic atrophy in wild-type and gastrin-deficient mice. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2005;288:G362-G375. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Hoffmann W. TFF2, a MUC6-binding lectin stabilizing the gastric mucus barrier and more (Review). Int J Oncol. 2015;47:806-816. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Jencks DS, Adam JD, Borum ML, Koh JM, Stephen S, Doman DB. Overview of Current Concepts in Gastric Intestinal Metaplasia and Gastric Cancer. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2018;14:92-101. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Can N, Oz Puyan F, Altaner S, Ozyilmaz F, Tokuc B, Pehlivanoglu Z, Kutlu KA. Mucins, trefoil factors and pancreatic duodenal homeobox 1 expression in spasmolytic polypeptide expressing metaplasia and intestinal metaplasia adjacent to gastric carcinomas. Arch Med Sci. 2020;16:1402-1410. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Burclaff J, Willet SG, Sáenz JB, Mills JC. Proliferation and Differentiation of Gastric Mucous Neck and Chief Cells During Homeostasis and Injury-induced Metaplasia. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:598-609.e5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Brown JW, Cho CJ, Mills JC. Paligenosis: Cellular Remodeling During Tissue Repair. Annu Rev Physiol. 2022;84:461-483. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Lennerz JK, Kim SH, Oates EL, Huh WJ, Doherty JM, Tian X, Bredemeyer AJ, Goldenring JR, Lauwers GY, Shin YK, Mills JC. The transcription factor MIST1 is a novel human gastric chief cell marker whose expression is lost in metaplasia, dysplasia, and carcinoma. Am J Pathol. 2010;177:1514-1533. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Brown JW, Lin X, Nicolazzi GA, Liu X, Nguyen T, Radyk MD, Burclaff J, Mills JC. Cathartocytosis: Jettisoning of cellular material during reprogramming of differentiated cells. Cell Rep. 2025;44:116070. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Radyk MD, Spatz LB, Peña BL, Brown JW, Burclaff J, Cho CJ, Kefalov Y, Shih CC, Fitzpatrick JA, Mills JC. ATF3 induces RAB7 to govern autodegradation in paligenosis, a conserved cell plasticity program. EMBO Rep. 2021;22:e51806. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Won Y, Sohn Y, Lee SH, Goldstein A, Gangula R, Mallal S, Goldenring JR. Stratifin Is Necessary for Spasmolytic Polypeptide-Expressing Metaplasia Development After Acute Gastric Injury. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2025;19:101521. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Lee SH, Jang B, Min J, Contreras-Panta EW, Presentation KS, Delgado AG, Piazuelo MB, Choi E, Goldenring JR. Up-regulation of Aquaporin 5 Defines Spasmolytic Polypeptide-Expressing Metaplasia and Progression to Incomplete Intestinal Metaplasia. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;13:199-217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Willet SG, Thanintorn N, McNeill H, Huh SH, Ornitz DM, Huh WJ, Hoft SG, DiPaolo RJ, Mills JC. SOX9 Governs Gastric Mucous Neck Cell Identity and Is Required for Injury-Induced Metaplasia. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;16:325-339. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Souza RF, Spechler SJ. Mechanisms and pathophysiology of Barrett oesophagus. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;19:605-620. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Contreras-Panta EW, Lee SH, Won Y, Norlander AE, Simmons AJ, Peebles RS Jr, Lau KS, Choi E, Goldenring JR. Interleukin 13 Promotes Maturation and Proliferation in Metaplastic Gastroids. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024;18:101366. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Miao ZF, Sun JX, Huang XZ, Bai S, Pang MJ, Li JY, Chen HY, Tong QY, Ye SY, Wang XY, Hu XH, Li JY, Zou JW, Xu W, Yang JH, Lu X, Mills JC, Wang ZN. Metaplastic regeneration in the mouse stomach requires a reactive oxygen species pathway. Dev Cell. 2024;59:1175-1191.e7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Meyer AR, Engevik AC, Willet SG, Williams JA, Zou Y, Massion PP, Mills JC, Choi E, Goldenring JR. Cystine/Glutamate Antiporter (xCT) Is Required for Chief Cell Plasticity After Gastric Injury. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;8:379-405. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Miao ZF, Sun JX, Adkins-Threats M, Pang MJ, Zhao JH, Wang X, Tang KW, Wang ZN, Mills JC. DDIT4 Licenses Only Healthy Cells to Proliferate During Injury-induced Metaplasia. Gastroenterology. 2021;160:260-271.e10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Miao ZF, Cho CJ, Wang ZN, Mills JC. Autophagy repurposes cells during paligenosis. Autophagy. 2021;17:588-589. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Sohn Y, Flores Semyonov B, El-Mekkoussi H, Wright CVE, Kaestner KH, Choi E, Goldenring JR. Telocyte Recruitment During the Emergence of a Metaplastic Niche in the Stomach. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024;18:101347. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Maloum F, Allaire JM, Gagné-Sansfaçon J, Roy E, Belleville K, Sarret P, Morisset J, Carrier JC, Mishina Y, Kaestner KH, Perreault N. Epithelial BMP signaling is required for proper specification of epithelial cell lineages and gastric endocrine cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2011;300:G1065-G1079. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Auclair BA, Benoit YD, Rivard N, Mishina Y, Perreault N. Bone morphogenetic protein signaling is essential for terminal differentiation of the intestinal secretory cell lineage. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:887-896. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Lee SH, Contreras Panta EW, Gibbs D, Won Y, Min J, Zhang C, Roland JT, Hong SH, Sohn Y, Krystofiak E, Jang B, Ferri L, Sangwan V, Ragoussis J, Camilleri-Broët S, Caruso J, Chen-Tanyolac C, Strasser M, Gascard P, Tlsty TD, Huang S, Choi E, Goldenring JR. Apposition of Fibroblasts With Metaplastic Gastric Cells Promotes Dysplastic Transition. Gastroenterology. 2023;165:374-390. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Hayakawa Y, Fox JG, Wang TC. The Origins of Gastric Cancer From Gastric Stem Cells: Lessons From Mouse Models. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;3:331-338. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Hayakawa Y, Wang TC. Isthmus Progenitors, Not Chief Cells, Are the Likely Origin of Metaplasia in eR1-CreERT; LSL-Kras(G12D) Mice. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:2078-2079. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Hata M, Kinoshita H, Hayakawa Y, Konishi M, Tsuboi M, Oya Y, Kurokawa K, Hayata Y, Nakagawa H, Tateishi K, Fujiwara H, Hirata Y, Worthley DL, Muranishi Y, Furukawa T, Kon S, Tomita H, Wang TC, Koike K. GPR30-Expressing Gastric Chief Cells Do Not Dedifferentiate But Are Eliminated via PDK-Dependent Cell Competition During Development of Metaplasia. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:1650-1666.e15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Adkins-Threats M, Arimura S, Huang YZ, Divenko M, To S, Mao H, Zeng Y, Hwang JY, Burclaff JR, Jain S, Mills JC. Metabolic regulator ERRγ governs gastric stem cell differentiation into acid-secreting parietal cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2024;31:886-903.e8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Engevik AC, Feng R, Choi E, White S, Bertaux-Skeirik N, Li J, Mahe MM, Aihara E, Yang L, DiPasquale B, Oh S, Engevik KA, Giraud AS, Montrose MH, Medvedovic M, Helmrath MA, Goldenring JR, Zavros Y. The Development of Spasmolytic Polypeptide/TFF2-Expressing Metaplasia (SPEM) During Gastric Repair Is Absent in the Aged Stomach. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;2:605-624. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Meyer AR, Goldenring JR. Injury, repair, inflammation and metaplasia in the stomach. J Physiol. 2018;596:3861-3867. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 12.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Garabatos N, Angelats E, Santamaria P. Mechanistic and therapeutic advances in immune-mediated gastrointestinal disorders. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2025;156:1133-1159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Chey WD, Howden CW, Moss SF, Morgan DR, Greer KB, Grover S, Shah SC. ACG Clinical Guideline: Treatment of Helicobacter pylori Infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2024;119:1730-1753. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 144] [Article Influence: 72.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Gonciarz W, Krupa A, Moran AP, Tomaszewska A, Chmiela M. Interference of LPS H. pylori with IL-33-Driven Regeneration of Caviae porcellus Primary Gastric Epithelial Cells and Fibroblasts. Cells. 2021;10:1385. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Sah DK, Arjunan A, Lee B, Jung YD. Reactive Oxygen Species and H. pylori Infection: A Comprehensive Review of Their Roles in Gastric Cancer Development. Antioxidants (Basel). 2023;12:1712. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Aihara E, Matthis AL, Karns RA, Engevik KA, Jiang P, Wang J, Yacyshyn BR, Montrose MH. Epithelial Regeneration After Gastric Ulceration Causes Prolonged Cell-Type Alterations. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;2:625-647. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Goldenring JR, Nomura S. Differentiation of the gastric mucosa III. Animal models of oxyntic atrophy and metaplasia. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2006;291:G999-1004. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Osaki LH, Bockerstett KA, Wong CF, Ford EL, Madison BB, DiPaolo RJ, Mills JC. Interferon-γ directly induces gastric epithelial cell death and is required for progression to metaplasia. J Pathol. 2019;247:513-523. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Bockerstett KA, DiPaolo RJ. Regulation of Gastric Carcinogenesis by Inflammatory Cytokines. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;4:47-53. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Petersen CP, Weis VG, Nam KT, Sousa JF, Fingleton B, Goldenring JR. Macrophages promote progression of spasmolytic polypeptide-expressing metaplasia after acute loss of parietal cells. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:1727-38.e8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Sáenz JB, Vargas N, Mills JC. Tropism for Spasmolytic Polypeptide-Expressing Metaplasia Allows Helicobacter pylori to Expand Its Intragastric Niche. Gastroenterology. 2019;156:160-174.e7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Bockerstett KA, Petersen CP, Noto CN, Kuehm LM, Wong CF, Ford EL, Teague RM, Mills JC, Goldenring JR, DiPaolo RJ. Interleukin 27 Protects From Gastric Atrophy and Metaplasia During Chronic Autoimmune Gastritis. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;10:561-579. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Ding L, Chakrabarti J, Sheriff S, Li Q, Thi Hong HN, Sontz RA, Mendoza ZE, Schreibeis A, Helmrath MA, Zavros Y, Merchant JL. Toll-like Receptor 9 Pathway Mediates Schlafen(+)-MDSC Polarization During Helicobacter-induced Gastric Metaplasias. Gastroenterology. 2022;163:411-425.e4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Wada T, Ishimoto T, Seishima R, Tsuchihashi K, Yoshikawa M, Oshima H, Oshima M, Masuko T, Wright NA, Furuhashi S, Hirashima K, Baba H, Kitagawa Y, Saya H, Nagano O. Functional role of CD44v-xCT system in the development of spasmolytic polypeptide-expressing metaplasia. Cancer Sci. 2013;104:1323-1329. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Shimizu T, Sohn Y, Choi E, Petersen CP, Prasad N, Goldenring JR. Decrease in MiR-148a Expression During Initiation of Chief Cell Transdifferentiation. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;9:61-78. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Nam KT, Varro A, Coffey RJ, Goldenring JR. Potentiation of oxyntic atrophy-induced gastric metaplasia in amphiregulin-deficient mice. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:1804-1819. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Correa P. A human model of gastric carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 1988;48:3554-3560. [PubMed] |

| 52. | Goldenring JR. Spasmolytic polypeptide-expressing metaplasia (SPEM) cell lineages can be an origin of gastric cancer. J Pathol. 2023;260:109-111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Kumagai K, Shimizu T, Nikaido M, Hirano T, Kakiuchi N, Takeuchi Y, Minamiguchi S, Sakurai T, Teramura M, Utsumi T, Hiramatsu Y, Nakanishi Y, Takai A, Miyamoto S, Ogawa S, Seno H. On the origin of gastric tumours: analysis of a case with intramucosal gastric carcinoma and oxyntic gland adenoma. J Pathol. 2023;259:362-368. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Nam KT, Lee HJ, Sousa JF, Weis VG, O'Neal RL, Finke PE, Romero-Gallo J, Shi G, Mills JC, Peek RM Jr, Konieczny SF, Goldenring JR. Mature chief cells are cryptic progenitors for metaplasia in the stomach. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:2028-2037.e9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 233] [Cited by in RCA: 245] [Article Influence: 15.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Yoshizawa N, Takenaka Y, Yamaguchi H, Tetsuya T, Tanaka H, Tatematsu M, Nomura S, Goldenring JR, Kaminishi M. Emergence of spasmolytic polypeptide-expressing metaplasia in Mongolian gerbils infected with Helicobacter pylori. Lab Invest. 2007;87:1265-1276. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Weis VG, Sousa JF, LaFleur BJ, Nam KT, Weis JA, Finke PE, Ameen NA, Fox JG, Goldenring JR. Heterogeneity in mouse spasmolytic polypeptide-expressing metaplasia lineages identifies markers of metaplastic progression. Gut. 2013;62:1270-1279. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | He L, Zhang X, Zhang S, Wang Y, Hu W, Li J, Liu Y, Liao Y, Peng X, Li J, Zhao H, Wang L, Lv YF, Hu CJ, Yang SM. H. Pylori-Facilitated TERT/Wnt/β-Catenin Triggers Spasmolytic Polypeptide-Expressing Metaplasia and Oxyntic Atrophy. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2025;12:e2401227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Goldenring JR, Ray GS, Coffey RJ, Meunier PC, Haley PJ, Barnes TB, Car BD. Reversible drug-induced oxyntic atrophy in rats. Gastroenterology. 2000;118:1080-1093. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Huh WJ, Khurana SS, Geahlen JH, Kohli K, Waller RA, Mills JC. Tamoxifen induces rapid, reversible atrophy, and metaplasia in mouse stomach. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:21-24.e7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 179] [Cited by in RCA: 201] [Article Influence: 14.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Saenz JB, Burclaff J, Mills JC. Modeling Murine Gastric Metaplasia Through Tamoxifen-Induced Acute Parietal Cell Loss. Methods Mol Biol. 2016;1422:329-339. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Chen Q, Weng K, Lin M, Jiang M, Fang Y, Chung SSW, Huang X, Zhong Q, Liu Z, Huang Z, Lin J, Li P, El-Rifai W, Zaika A, Li H, Rustgi AK, Nakagawa H, Abrams JA, Wang TC, Lu C, Huang C, Que J. SOX9 Modulates the Transformation of Gastric Stem Cells Through Biased Symmetric Cell Division. Gastroenterology. 2023;164:1119-1136.e12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Fang KT, Hung H, Lau NYS, Chi JH, Wu DC, Cheng KH. Development of a Genetically Engineered Mouse Model Recapitulating LKB1 and PTEN Deficiency in Gastric Cancer Pathogenesis. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15:5893. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Zavros Y, Eaton KA, Kang W, Rathinavelu S, Katukuri V, Kao JY, Samuelson LC, Merchant JL. Chronic gastritis in the hypochlorhydric gastrin-deficient mouse progresses to adenocarcinoma. Oncogene. 2005;24:2354-2366. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Tu S, Bhagat G, Cui G, Takaishi S, Kurt-Jones EA, Rickman B, Betz KS, Penz-Oesterreicher M, Bjorkdahl O, Fox JG, Wang TC. Overexpression of interleukin-1beta induces gastric inflammation and cancer and mobilizes myeloid-derived suppressor cells in mice. Cancer Cell. 2008;14:408-419. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 702] [Cited by in RCA: 700] [Article Influence: 38.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Syu LJ, El-Zaatari M, Eaton KA, Liu Z, Tetarbe M, Keeley TM, Pero J, Ferris J, Wilbert D, Kaatz A, Zheng X, Qiao X, Grachtchouk M, Gumucio DL, Merchant JL, Samuelson LC, Dlugosz AA. Transgenic expression of interferon-γ in mouse stomach leads to inflammation, metaplasia, and dysplasia. Am J Pathol. 2012;181:2114-2125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Matkar SS, Durham A, Brice A, Wang TC, Rustgi AK, Hua X. Systemic activation of K-ras rapidly induces gastric hyperplasia and metaplasia in mice. Am J Cancer Res. 2011;1:432-445. [PubMed] |

| 67. | Chung WC, Zhou Y, Atfi A, Xu K. Downregulation of Notch Signaling in Kras-Induced Gastric Metaplasia. Neoplasia. 2019;21:810-821. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Nam KT, Lee HJ, Mok H, Romero-Gallo J, Crowe JE Jr, Peek RM Jr, Goldenring JR. Amphiregulin-deficient mice develop spasmolytic polypeptide expressing metaplasia and intestinal metaplasia. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:1288-1296. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Choi E, Hendley AM, Bailey JM, Leach SD, Goldenring JR. Expression of Activated Ras in Gastric Chief Cells of Mice Leads to the Full Spectrum of Metaplastic Lineage Transitions. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:918-30.e13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 138] [Article Influence: 13.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Jang B, Kim H, Lee SH, Won Y, Kaji I, Coffey RJ, Choi E, Goldenring JR. Dynamic tuft cell expansion during gastric metaplasia and dysplasia. J Pathol Clin Res. 2024;10:e352. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Gabriel TT, Park JD, Madala SK, Coffey RJ, Huh WJ. Development of Mouse Models for Ménétrier's Disease. J Vis Exp. 2025;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Garcia-Carracedo D, Yu CC, Akhavan N, Fine SA, Schönleben F, Maehara N, Karg DC, Xie C, Qiu W, Fine RL, Remotti HE, Su GH. Smad4 loss synergizes with TGFα overexpression in promoting pancreatic metaplasia, PanIN development, and fibrosis. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0120851. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Nomura S, Settle SH, Leys CM, Means AL, Peek RM Jr, Leach SD, Wright CV, Coffey RJ, Goldenring JR. Evidence for repatterning of the gastric fundic epithelium associated with Ménétrier's disease and TGFalpha overexpression. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:1292-1305. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Zhang A, Niu L, Ni Y, Liu W, Gao X, Chang L, Cao P. STAT3 inhibition mitigates experimental autoimmune gastritis by restoring Th17/Treg immune balance. Immunol Res. 2025;73:90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Hao X, Yuan S, Ning J, Zhou Y, Lang Y, Han X, Meng Q, Xiong Y, Cui R, Gong Y, Ma C, Xu W, Wang Y, Guo X, Wang C, Zhang J, Fu W, Ding S. Luteolin improves precancerous conditions of the gastric mucosa by binding STAT3 and inhibiting LCN2 expression. Int J Biol Sci. 2025;21:3397-3415. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Li W, Huang X, Han X, Zhang J, Gao L, Chen H. IL-17A in gastric carcinogenesis: good or bad? Front Immunol. 2024;15:1501293. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Privitera G, Williams JJ, De Salvo C. The Importance of Th2 Immune Responses in Mediating the Progression of Gastritis-Associated Metaplasia to Gastric Cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2024;16:522. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Li CM, Chen Z. Autoimmunity as an Etiological Factor of Cancer: The Transformative Potential of Chronic Type 2 Inflammation. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9:664305. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Bockerstett KA, Osaki LH, Petersen CP, Cai CW, Wong CF, Nguyen TM, Ford EL, Hoft DF, Mills JC, Goldenring JR, DiPaolo RJ. Interleukin-17A Promotes Parietal Cell Atrophy by Inducing Apoptosis. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;5:678-690.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Li ML, Hong XX, Zhang WJ, Liang YZ, Cai TT, Xu YF, Pan HF, Kang JY, Guo SJ, Li HW. Helicobacter pylori plays a key role in gastric adenocarcinoma induced by spasmolytic polypeptide-expressing metaplasia. World J Clin Cases. 2023;11:3714-3724. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Yuan XY, Zhang Y, Zhao X, Chen A, Liu P. IL-1β, an important cytokine affecting Helicobacter pylori-mediated gastric carcinogenesis. Microb Pathog. 2023;174:105933. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 82. | Zhou L, Tang C, Li X, Feng F. IL-6/IL-10 mRNA expression ratio in tumor tissues predicts prognosis in gastric cancer patients without distant metastasis. Sci Rep. 2022;12:19427. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 83. | Kang JH, Park S, Rho J, Hong EJ, Cho YE, Won YS, Kwon HJ. IL-17A promotes Helicobacter pylori-induced gastric carcinogenesis via interactions with IL-17RC. Gastric Cancer. 2023;26:82-94. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 84. | Dewayani A, Fauzia KA, Alfaray RI, Waskito LA, Doohan D, Rezkitha YAA, Abdurachman A, Kobayashi T, I'tishom R, Yamaoka Y, Miftahussurur M. The Roles of IL-17, IL-21, and IL-23 in the Helicobacter pylori Infection and Gastrointestinal Inflammation: A Review. Toxins (Basel). 2021;13:315. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 85. | Mozooni Z, Ghadyani R, Soleimani S, Ahangar ER, Sheikhpour M, Haghighi M, Motallebi M, Movafagh A, Aghaei-Zarch SM. TNF-α, and TNFRs in gastrointestinal cancers. Pathol Res Pract. 2024;263:155665. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 86. | Hwang MA, Won M, Im JY, Kang MJ, Kweon DH, Kim BK. TNF-α Secreted from Macrophages Increases the Expression of Prometastatic Integrin αV in Gastric Cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;24:376. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 87. | Hong JB, Zuo W, Wang AJ, Lu NH. Helicobacter pylori Infection Synergistic with IL-1β Gene Polymorphisms Potentially Contributes to the Carcinogenesis of Gastric Cancer. Int J Med Sci. 2016;13:298-303. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 88. | Yu B, de Vos D, Guo X, Peng S, Xie W, Peppelenbosch MP, Fu Y, Fuhler GM. IL-6 facilitates cross-talk between epithelial cells and tumor- associated macrophages in Helicobacter pylori-linked gastric carcinogenesis. Neoplasia. 2024;50:100981. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 89. | Liang P, Zhang Y, Jiang T, Jin T, Chen Z, Li Z, Chen Z, He F, Hu J, Yang K. Association between IL-6 and prognosis of gastric cancer: a retrospective study. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2023;16:17562848231211543. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 90. | Oertli M, Sundquist M, Hitzler I, Engler DB, Arnold IC, Reuter S, Maxeiner J, Hansson M, Taube C, Quiding-Järbrink M, Müller A. DC-derived IL-18 drives Treg differentiation, murine Helicobacter pylori-specific immune tolerance, and asthma protection. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:1082-1096. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 211] [Cited by in RCA: 255] [Article Influence: 18.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 91. | Lee SY, Jhun J, Woo JS, Lee KH, Hwang SH, Moon J, Park G, Choi SS, Kim SJ, Jung YJ, Song KY, Cho ML. Gut microbiome-derived butyrate inhibits the immunosuppressive factors PD-L1 and IL-10 in tumor-associated macrophages in gastric cancer. Gut Microbes. 2024;16:2300846. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 33.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 92. | Ge Y, Janson V, Dong Z, Liu H. Role and mechanism of IL-33 in bacteria infection related gastric cancer continuum: From inflammation to tumor progression. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. 2025;1880:189296. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 93. | Petersen CP, Meyer AR, De Salvo C, Choi E, Schlegel C, Petersen A, Engevik AC, Prasad N, Levy SE, Peebles RS, Pizarro TT, Goldenring JR. A signalling cascade of IL-33 to IL-13 regulates metaplasia in the mouse stomach. Gut. 2018;67:805-817. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 13.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 94. | Liu X, Ma Z, Deng Z, Yi Z, Tuo B, Li T, Liu X. Role of spasmolytic polypeptide-expressing metaplasia in gastric mucosal diseases. Am J Cancer Res. 2023;13:1667-1681. [PubMed] |

| 95. | Byrne J, Baker K, Houston A, Brint E. IL-36 cytokines in inflammatory and malignant diseases: not the new kid on the block anymore. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2021;78:6215-6227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 96. | Zhang Y, Liu Y, Guan X, Qu M, Wu D, Liu N, Lin Z, Liu Y, Wang H, Yang L. IL-36-related genes predict prognosis of gastric cancer. Front Oncol. 2025;15:1566993. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 97. | Loe AKH, Rao-Bhatia A, Wei Z, Kim JE, Guan B, Qin Y, Hong M, Kwak HS, Liu X, Zhang L, Wrana JL, Guo H, Kim TH. YAP targetome reveals activation of SPEM in gastric pre-neoplastic progression and regeneration. Cell Rep. 2023;42:113497. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 98. | Garzon R, Marcucci G, Croce CM. Targeting microRNAs in cancer: rationale, strategies and challenges. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2010;9:775-789. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1216] [Cited by in RCA: 1222] [Article Influence: 76.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 99. | Li D, Zhang Y, Li Y, Wang X, Wang F, Du J, Zhang H, Shi H, Wang Y, Gao Y, Feng Y, Yan J, Xue Y, Yang Y, Zhang J. miR-149 Suppresses the Proliferation and Metastasis of Human Gastric Cancer Cells by Targeting FOXC1. Biomed Res Int. 2021;2021:1503403. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 100. | Yang Y, Nan Y, Du YH, Huang SC, Lu DD, Zhang JF, Li X, Chen Y, Zhang L, Yuan L. 18β-glycyrrhetinic acid promotes gastric cancer cell autophagy and inhibits proliferation by regulating miR-328-3p/signal transducer and activator of transcription 3. World J Gastroenterol. 2023;29:4317-4333. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 101. | Min J, Han TS, Sohn Y, Shimizu T, Choi B, Bae SW, Hur K, Kong SH, Suh YS, Lee HJ, Kim JS, Min JK, Kim WH, Kim VN, Choi E, Goldenring JR, Yang HK. microRNA-30a arbitrates intestinal-type early gastric carcinogenesis by directly targeting ITGA2. Gastric Cancer. 2020;23:600-613. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 102. | Chong Y, Yu D, Lu Z, Nie F. Role and research progress of spasmolytic polypeptideexpressing metaplasia in gastric cancer (Review). Int J Oncol. 2024;64:33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 103. | Wang N, Wu S, Zhao J, Chen M, Zeng J, Lu G, Wang J, Zhang J, Liu J, Shi Y. Bile acids increase intestinal marker expression via the FXR/SNAI2/miR-1 axis in the stomach. Cell Oncol (Dordr). 2021;44:1119-1131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 104. | Cao Y, Wang D, Mo G, Peng Y, Li Z. Gastric precancerous lesions:occurrence, development factors, and treatment. Front Oncol. 2023;13:1226652. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 105. | Chen WQ, Tian FL, Zhang JW, Yang XJ, Li YP. Preventive and inhibitive effects of Yiwei Xiaoyu granules on the development and progression of spasmolytic polypeptide-expressing metaplasia lesions. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2021;13:1741-1754. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 106. | Ke J, Xu HE, Williams BO. Lipid modification in Wnt structure and function. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2013;24:129-133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 107. | Xu W, Kimelman D. Mechanistic insights from structural studies of beta-catenin and its binding partners. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:3337-3344. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 176] [Cited by in RCA: 204] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 108. | Zuo W, Yang H, Li N, Ouyang Y, Xu X, Hong J. Helicobacter pylori infection activates Wnt/β-catenin pathway to promote the occurrence of gastritis by upregulating ASCL1 and AQP5. Cell Death Discov. 2022;8:257. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 109. | Pang Q, Tang Z, Luo L. The crosstalk between oncogenic signaling and ferroptosis in cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2024;197:104349. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 110. | Koushyar S, Powell AG, Vincan E, Phesse TJ. Targeting Wnt Signaling for the Treatment of Gastric Cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:3927. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 111. | Willet SG, Lewis MA, Miao ZF, Liu D, Radyk MD, Cunningham RL, Burclaff J, Sibbel G, Lo HG, Blanc V, Davidson NO, Wang ZN, Mills JC. Regenerative proliferation of differentiated cells by mTORC1-dependent paligenosis. EMBO J. 2018;37:e98311. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 151] [Article Influence: 18.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 112. | Greicius G, Kabiri Z, Sigmundsson K, Liang C, Bunte R, Singh MK, Virshup DM. PDGFRα(+) pericryptal stromal cells are the critical source of Wnts and RSPO3 for murine intestinal stem cells in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115:E3173-E3181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 170] [Cited by in RCA: 235] [Article Influence: 29.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 113. | Sigal M, Logan CY, Kapalczynska M, Mollenkopf HJ, Berger H, Wiedenmann B, Nusse R, Amieva MR, Meyer TF. Stromal R-spondin orchestrates gastric epithelial stem cells and gland homeostasis. Nature. 2017;548:451-455. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 167] [Article Influence: 18.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 114. | Fischer AS, Müllerke S, Arnold A, Heuberger J, Berger H, Lin M, Mollenkopf HJ, Wizenty J, Horst D, Tacke F, Sigal M. R-spondin/YAP axis promotes gastric oxyntic gland regeneration and Helicobacter pylori-associated metaplasia in mice. J Clin Invest. 2022;132:e151363. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 115. | Hoesel B, Schmid JA. The complexity of NF-κB signaling in inflammation and cancer. Mol Cancer. 2013;12:86. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2313] [Cited by in RCA: 2619] [Article Influence: 201.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 116. | Israël A. The IKK complex, a central regulator of NF-kappaB activation. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2:a000158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 494] [Cited by in RCA: 690] [Article Influence: 43.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 117. | Zeng X, Yang M, Ye T, Feng J, Xu X, Yang H, Wang X, Bao L, Li R, Xue B, Zang J, Huang Y. Mitochondrial GRIM-19 loss in parietal cells promotes spasmolytic polypeptide-expressing metaplasia through NLR family pyrin domain-containing 3 (NLRP3)-mediated IL-33 activation via a reactive oxygen species (ROS) -NRF2- Heme oxygenase-1(HO-1)-NF-кB axis. Free Radic Biol Med. 2023;202:46-61. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 118. | Ding L, Li Q, Chakrabarti J, Munoz A, Faure-Kumar E, Ocadiz-Ruiz R, Razumilava N, Zhang G, Hayes MH, Sontz RA, Mendoza ZE, Mahurkar S, Greenson JK, Perez-Perez G, Hanh NTH, Zavros Y, Samuelson LC, Iliopoulos D, Merchant JL. MiR130b from Schlafen4(+) MDSCs stimulates epithelial proliferation and correlates with preneoplastic changes prior to gastric cancer. Gut. 2020;69:1750-1761. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 119. | Shimizu T, Choi E, Petersen CP, Noto JM, Romero-Gallo J, Piazuelo MB, Washington MK, Peek RM Jr, Goldenring JR. Characterization of progressive metaplasia in the gastric corpus mucosa of Mongolian gerbils infected with Helicobacter pylori. J Pathol. 2016;239:399-410. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 120. | Dong J, Cheng XD, Zhang WD, Qin JJ. Recent Update on Development of Small-Molecule STAT3 Inhibitors for Cancer Therapy: From Phosphorylation Inhibition to Protein Degradation. J Med Chem. 2021;64:8884-8915. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 160] [Article Influence: 32.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 121. | Zhang X, Soutto M, Chen Z, Bhat N, Zhu S, Eissmann MF, Ernst M, Lu H, Peng D, Xu Z, El-Rifai W. Induction of Fibroblast Growth Factor Receptor 4 by Helicobacter pylori via Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 3 With a Feedforward Activation Loop Involving SRC Signaling in Gastric Cancer. Gastroenterology. 2022;163:620-636.e9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 122. | Kitamura H, Ohno Y, Toyoshima Y, Ohtake J, Homma S, Kawamura H, Takahashi N, Taketomi A. Interleukin-6/STAT3 signaling as a promising target to improve the efficacy of cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Sci. 2017;108:1947-1952. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 133] [Cited by in RCA: 218] [Article Influence: 24.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 123. | El-Zaatari M, Kao JY, Tessier A, Bai L, Hayes MM, Fontaine C, Eaton KA, Merchant JL. Gli1 deletion prevents Helicobacter-induced gastric metaplasia and expansion of myeloid cell subsets. PLoS One. 2013;8:e58935. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 124. | Todisco A. Regulation of Gastric Metaplasia, Dysplasia, and Neoplasia by Bone Morphogenetic Protein Signaling. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;3:339-347. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 125. | Gharibi T, Barpour N, Hosseini A, Mohammadzadeh A, Marofi F, Ebrahimi-Kalan A, Nejati-Koshki K, Abdollahpour-Alitappeh M, Safaei S, Baghbani E, Baradaran B. STA-21, a small molecule STAT3 inhibitor, ameliorates experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis by altering Th-17/Treg balance. Int Immunopharmacol. 2023;119:110160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 126. | Zhao P, Li J, Tian Y, Mao J, Liu X, Feng S, Li J, Bian Q, Ji H, Zhang L. Restoring Th17/Treg balance via modulation of STAT3 and STAT5 activation contributes to the amelioration of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease by Bufei Yishen formula. J Ethnopharmacol. 2018;217:152-162. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 127. | Taylor NA, Vick SC, Iglesia MD, Brickey WJ, Midkiff BR, McKinnon KP, Reisdorf S, Anders CK, Carey LA, Parker JS, Perou CM, Vincent BG, Serody JS. Treg depletion potentiates checkpoint inhibition in claudin-low breast cancer. J Clin Invest. 2017;127:3472-3483. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 13.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 128. | Nguyen TL, Khurana SS, Bellone CJ, Capoccia BJ, Sagartz JE, Kesman RA Jr, Mills JC, DiPaolo RJ. Autoimmune gastritis mediated by CD4+ T cells promotes the development of gastric cancer. Cancer Res. 2013;73:2117-2126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |