Published online Feb 15, 2026. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v18.i2.113959

Revised: November 9, 2025

Accepted: December 11, 2025

Published online: February 15, 2026

Processing time: 148 Days and 17.7 Hours

Chronic atrophic gastritis (CAG) is a significant precancerous condition of gastric cancer (GC). CAG often lacks typical symptoms in its early stages, and clinical di

To construct and validate a CAG risk prediction model to achieve noninvasive and accurate identification of high-risk patients.

This study included 1268 subjects from a GC screening program. Multimodal data, including serological marker, demographic, lifestyle, and family history data, were collected. Subjects were grouped by pathological biopsy results. Least absolute shrinkage and selection operator regression was used for feature selection. A model was constructed using the random forest algorithm, evaluated with metrics such as the area under the curve (AUC), and interpreted using the SHapley Additive exPlanation (SHAP) method. The model was validated in an independent external cohort, and a web-based prediction platform was developed using Shiny.

Six key features were ultimately included: Age, Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection status, pepsinogen I/II ratio (PGR), smoking history, alcohol consumption history, and family history of GC. The model achieved AUCs of 0.8542 and 0.8073 in the training and testing sets, respectively, and an AUC of 0.8505 in the external validation cohort, demonstrating good generalizability and stability. SHAP analysis indicated that H. pylori infection, age, and PGR were the most important variables influencing CAG risk. The final model was successfully embedded into a web-based platform for convenient clinical application.

The random forest-based CAG prediction model is a highly accurate and interpretable tool with significant clinical utility in early screening and identifying high-risk patients.

Core Tip: This study addresses the need for a noninvasive method to screen for chronic atrophic gastritis (CAG), a key precancerous condition of gastric cancer (GC). We developed and validated a random forest machine learning model using data from 1268 subjects. The model accurately predicts CAG risk using six easily obtainable features: Helicobacter pylori infection status, age, pepsinogen ratio, smoking history, alcohol use history, and family history of GC. The model demonstrated high accuracy and generalizability (area under the curve > 0.85). A user-friendly web calculator was created for clinical application, providing a practical tool for the early identification of high-risk individuals.

- Citation: Cao H, Han JL, Wu H, Si SP, Ding LJ, Ji L, Zhang HZ, Yin J, Zhou ZY, Zhang YN, Lv ZF, Tian WY, Zhan Q, Wang H, An FM. Risk prediction for chronic atrophic gastritis using a random forest model: A multicenter study. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2026; 18(2): 113959

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v18/i2/113959.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v18.i2.113959

Gastric cancer (GC) is among the most prevalent malignant tumors worldwide, with a disease burden that shows significant geographical disparities. According to global cancer statistics, East Asia accounts for approximately 60% of all GC cases, and China alone contributes to approximately half of the world’s new cases and deaths annually, posing a severe public health challenge[1]. The Correa cascade is widely recognized as one of the primary pathways involved in the development of intestinal-type GC. This theory posits that gastric carcinogenesis is a multistage, progressive process that includes chronic atrophic gastritis (CAG), intestinal metaplasia, dysplasia, and ultimately adenocarcinoma[2]. CAG is a common gastric disease and a crucial precancerous condition for patients with GC. CAG is characterized by a reduction in the number of gastric mucosal glands and mucosal atrophy and is often accompanied by intestinal metaplasia and dysplasia. Most patients exhibit no obvious symptoms or only nonspecific gastric discomfort[3]. Studies have shown that the risk of developing GC in patients with CAG is 4-6 times greater than that in the normal population[4].

The 2019 British Society of Gastroenterology guidelines on the diagnosis and management of patients at risk of gastric adenocarcinoma indicate that the prevalence of CAG is relatively low in Western populations (0%-8.3%), while it is sig

Machine learning, a technology that uses algorithms to automatically learn patterns from large datasets for prediction or classification, has been widely applied in the medical field in recent years[8]. Compared with traditional statistical models, machine learning models offer several significant advantages. First, they can handle high-dimensional, complex data, making them suitable for clinical scenarios with multiple interacting variables. Second, their superior ability to model nonlinear relationships allows for a more accurate reflection of the complex mechanisms of disease development. Furthermore, machine learning models have strong self-optimization and generalization capabilities, enabling accurate predictions on new data after training. Machine learning has been used in areas such as computer-aided diagnosis in digestive endoscopy and risk prediction and prognosis estimation for gastrointestinal tumors[9]. However, a precise prediction model for CAG risk before endoscopic examination is lacking.

In this study, we aimed to develop and validate an interpretable machine learning model using the random forest algorithm for the early and accurate prediction of CAG risk in the general population. We used the SHapley Additive exPlanation (SHAP) method to explain feature importance and interpret the model’s predictions to identify relevant risk factors for CAG, providing reliable clinical evidence for screening high-risk individuals before endoscopy. To facilitate clinical application and promotion, we further developed a visual web-based platform using the Shiny framework, allowing clinicians to intuitively obtain individual CAG risk predictions with simple operation and high practicality.

The research protocol was submitted to and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Wuxi People's Hospital (Approval No. KY23001) and registered in the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (ChiCTR2400085856). All participants provided signed informed consent before joining the study and were fully informed about the study's content, purpose, potential risks, and personal rights. All the data used by the application underwent strict deidentification before being used for model building and deployment on the Shiny platform. All identifiers (such as names and ID numbers) have been removed. Furthermore, users cannot access, download, or deduce any single patient's raw data or identifiable information from any interface on the Shiny platform.

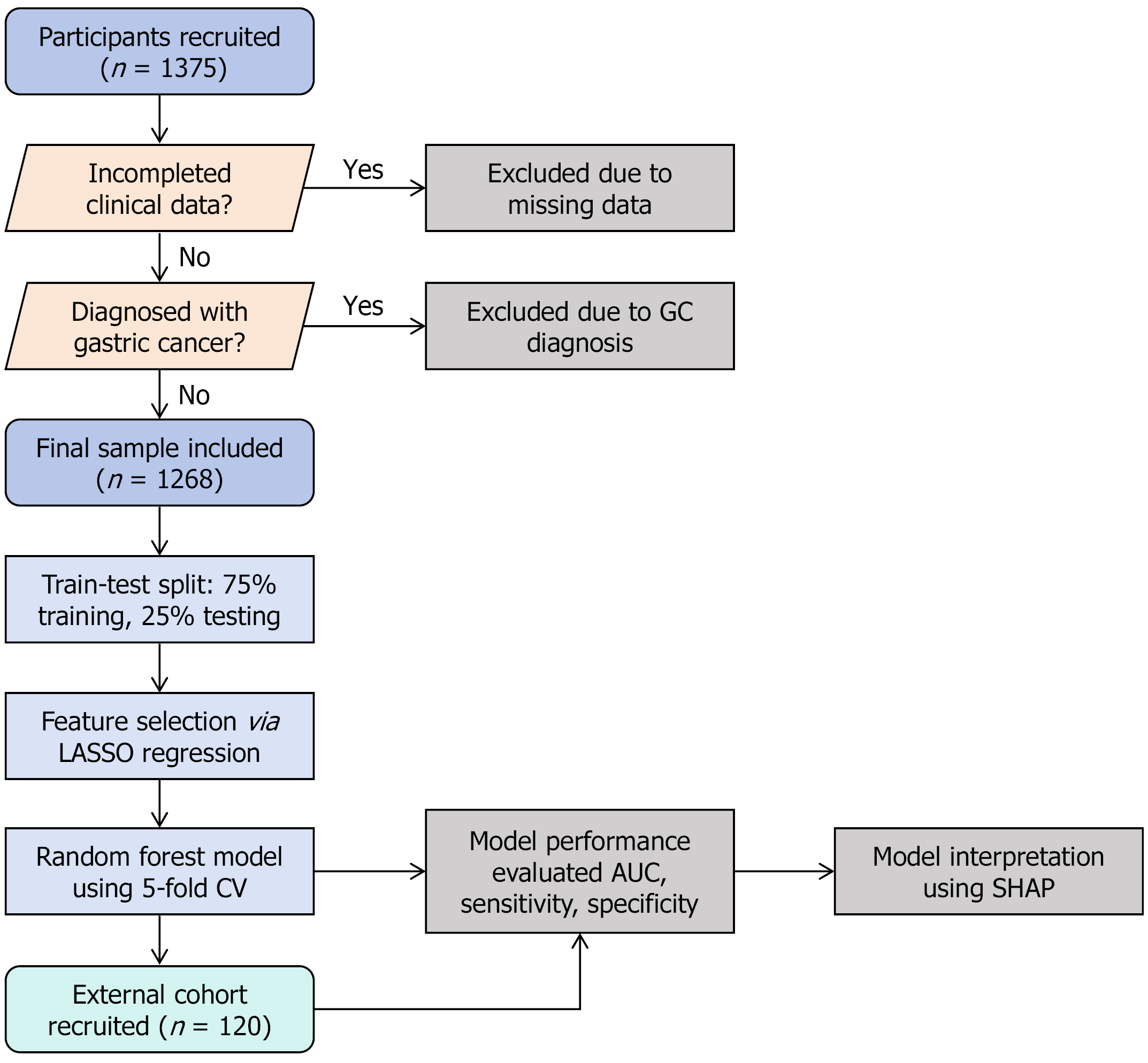

This retrospective study analyzed data from patients in a GC screening cohort in our city from October 2022 to December 2023. Starting in October 2022, permanent residents over 40 years old were invited to participate in the project in community batches. By December 2023, a total of 1375 participants had been recruited. General information from the subjects, including sex, age, body mass index (BMI), and education level; lifestyle habits, including smoking history, alcohol consumption, tea consumption, dietary temperature preference, fresh fruit intake frequency, salt intake, sleep duration, and sleep quality; and medical history, including hypertension, diabetes, and family history of cancer and GC, was collected through face-to-face questionnaires. We also investigated nonspecific symptoms of chronic gastritis, such as recurrent abdominal discomfort. After the face-to-face questionnaire was completed, each participant underwent serum Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) antibody testing, pepsinogen I (PGI) and pepsinogen II (PGII) detection, and upper gastrointestinal endoscopy with biopsy and pathological examination. Participants lacking pathological biopsy reports or serological indicators, as well as patients diagnosed with GC, were excluded. Finally, 1268 participants with complete baseline data were included in the study.

Serum H. pylori antibody detection was performed using a colloidal gold immunochromatographic assay (Hangzhou AllTest Biotech Co., Ltd.). During the test, a serum sample was added to the sample well of the test strip. The components in the serum reacted with the H. pylori antigen labeled with colloidal gold particles. The mixture then moved up the strip using capillary action. If positive, the gold-labeled H. pylori antigen first binds to the H. pylori antibody in the sample, and this complex is then captured by the anti-human antibody immobilized on the membrane, resulting in a purplish-red band in the test region. If negative, no purplish-red band appears in the test region. A purplish-red band always appeared in the control region, regardless of the presence of H. pylori antibodies. This served as a standard for adequate sample volume and proper chromatographic flow, as well as an internal control for the reagent. The test strip was removed from its original packaging and used within one hour. The sample was placed on a clean, flat surface, and 3 drops (approximately 75 μL) of the bubble-free serum sample were added vertically to the sample well. The results were read within 10-20 minutes after the purplish-red band appeared; readings after 20 minutes were considered invalid. PGI and PGII levels were measured using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit (Wuxi Jiangyuan Industrial & Trade Corp.). Standards and serum samples (50 μL per well) along with buffer (150 μL per well) were added to the microplate, incubated at 25 °C for 1 hour, and then washed 4 times with washing solution. Sm/Eu-labeled anti-PG or PG monoclonal antibodies diluted 50-fold (200 μL per well) were subsequently added, and the samples were incubated at 25 °C for 1 hour and then washed 6 times. A color-enhancing agent (200 μL per well) was added, the samples were incubated at 25 °C for 5 minutes, and the optical density was read at a wavelength of 450 nm[10].

Referring to the Sydney System OLGIM 5-point biopsy standard for CAG diagnosis and adapting to local conditions, we adopted a 3-point biopsy method. Specifically, biopsies were taken from the lesser curvature of the gastric antrum 2-3 cm from the pylorus, the lesser curvature of the gastric body 4 cm proximal to the gastric angle, and the greater curvature of the gastric body 8 cm proximal to the cardia. A diagnosis of CAG was made if atrophy combined with intestinal metaplasia was found in one or more biopsy sites. All pathological results were independently analyzed by two senior pathologists. In cases of disagreement, a higher-level expert reviewed the slides to make a final diagnosis.

In this study, a machine learning prediction model based on the random forest algorithm was constructed to assess the risk of CAG in subjects. A retrospective cohort design was used, which included 1268 subjects from the local GC screening program with complete clinical data. The following data were collected: (1) Serological markers, such as H. pylori antibody test results and PGI/II ratio (PGR); (2) Demographic characteristics, such as gender, age, BMI, and education level; (3) Lifestyle factors, such as long-term smoking history (smoking for more than 6 months), long-term alcohol consumption history (drinking more than 3 times/week), long-term tea consumption history (drinking more than once/week), dietary temperature preference, fresh fruit intake frequency, salt intake, sleep duration, and sleep quality (frequent inability to fall asleep within 30 minutes, waking up easily at night, or early awakening); (4) Clinical symptoms, such as recurrent abdominal discomfort (e.g., abdominal pain, anorexia, bloating, heartburn); and (5) Medical history, such as a history of hypertension, diabetes, and family history of cancer and GC in first-degree relatives. The included feature variables are described in Table 1. The dataset was split into a training set (75%) and a testing set (25%). Least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) regression was used for feature selection to identify the features most relevant to CAG risk[11]. We subsequently developed and validated a random forest machine learning model using 5-fold cross-validation and optimized it using the tidymodels package in R. After the optimal model was constructed, its performance was evaluated using various metrics, including the area under the curve (AUC), calibration curves, decision curves, specificity, and sensitivity. To enhance the model’s transparency and interpretability, the SHAP method was employed to explain the prediction results and clarify the impact of each feature on the predictions[12].

| Research variable | Categories | Coding |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 0 | |

| Female | 1 | |

| Education level | ||

| Junior high school or below | 0 | |

| Above junior high school | 1 | |

| Recurrent abdominal discomfort symptoms | ||

| None | 0 | |

| Present | 1 | |

| Long-term smoking history (smoking duration greater than 6 months) | ||

| None | 0 | |

| Present | 1 | |

| Long-term alcohol consumption history (drinking frequency greater than 3 times per week) | ||

| None | 0 | |

| Present | 1 | |

| Long-term tea drinking history (tea consumption frequency greater than once per week) | ||

| None | 0 | |

| Present | 1 | |

| Frequency of fresh fruit intake | ||

| Less than 5 times per week | 0 | |

| Greater than 5 times per week | 1 | |

| Dietary temperature preference | ||

| Moderate temperature | 0 | |

| Overly hot or cold | 1 | |

| Salt intake | ||

| Normal or less | 0 | |

| Excessive | 1 | |

| Sleep quality | ||

| Fair or good | 0 | |

| Poor | 1 | |

| Hypertension history | ||

| None | 0 | |

| Present | 1 | |

| Diabetes history | ||

| None | 0 | |

| Present | 1 | |

| Family history of tumors | ||

| None | 0 | |

| Present | 1 | |

| Family history of gastric cancer | ||

| None | 0 | |

| Present | 1 | |

| H. pylori infection history | ||

| Negative | 0 | |

| Positive | 1 | |

| Pepsinogen ratio | ||

| Age | ||

| Body mass index | ||

| Sleep duration | ||

For external validation of the model, we selected a cohort of 120 subjects from another early GC screening program conducted in a different region of the province starting in March 2025 to assess the accuracy of our constructed model (Figure 1).

Random forest is a popular machine learning model that belongs to the bagging technique in ensemble learning[13]. Model stability and accuracy can be improved by constructing multiple decision trees and integrating their prediction results. During training, the model performs multiple bootstrap sampling operations from the original data to generate several subdatasets, each of which is used to train one decision tree. In the node-splitting process of each tree, a random subset of features is selected to increase the model's diversity. For classification tasks, the random forest determines the final class by majority vote. This method excels in handling high-dimensional data, assessing feature importance, and has strong resistance to overfitting.

One of the key hyperparameters of the random forest algorithm, mtry, was set to the square root of the number of variables. For the parameters trees and min_n, we used a cross-validated grid search to find the optimal combination. The process involved randomly generating 100 combinations of trees and min_n, with the number of trees ranging from 100 to 1000 and min_n ranging from 10 to 50. We then constructed models with each of the 100 hyperparameter combinations and obtained the AUC value for each model. Finally, we selected the hyperparameters of the model with the best AUC values (trees = 234, min_n = 48) for subsequent research.

To facilitate the application of the model in a clinical setting, the final prediction model was integrated into a web-based platform using a Shiny application. By inputting the actual values of the six features required by the model, the app

Data analysis was performed using R language (version 4.4.0). Normally distributed data are expressed as the mean ± SD, whereas nonnormally distributed data are expressed as the median (interquartile range). The t tests or Mann-Whitney U tests were used for intergroup comparisons. Categorical variables were compared using the χ2 test or Fisher's exact test. LASSO feature selection was visualized using the glmnet package, and SHAP analysis was visualized using the shapviz package. A P value < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance for all analyses.

After those subjects with missing clinical data or a pathological diagnosis of GC were excluded, 1268 subjects were initially enrolled. This cohort comprised 619 CAG subjects and 649 non-CAG subjects. For continuous variables, the median PGR in the CAG group was 9.81 (IQR: 7.33-12.35), which was significantly lower than the 12.10 (IQR: 10.10-14.20) in the non-CAG group (P < 0.001). With respect to H. pylori infection history, the positivity rate in the CAG group was 76.90%, which was markedly higher than the 27.12% positivity rate in the non-CAG group (P < 0.001). The median age in the CAG group was 59 years (IQR: 53.50-64.00), which was significantly greater than the 56 years (IQR: 50.00-61.00) in the non-CAG group (P < 0.001). BMI did not differ significantly between the two groups, with a median of 23.51 (IQR: 21.63-25.44) in the CAG group and 23.38 (IQR: 21.36-25.39) in the non-CAG group (P = 0.762). Daily sleep duration was 7 hours (IQR: 6-8 hours) in both groups, with no significant difference (P = 0.394). Poor sleep quality was reported by 28.27% of the patients in the CAG group and 30.82% of the patients in the non-CAG group, but the difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.321). In terms of gender distribution, males constituted 46.85% of the CAG group, which was higher than the 37.29% of males in the non-CAG group. Females composed 53.15% of the CAG group, which was lower than the 62.71% of females in the non-CAG group (P < 0.001). Furthermore, among males, 45.49% had non-atrophic gastritis, and 54.51% had atrophic gastritis. Among females, 55.30% had non-atrophic gastritis, and 44.70% had atrophic gastritis. These results indicate a statistically significant difference in the distribution of the diagnosis of gastritis between the genders (χ² = 11.89, P < 0.001). In terms of education level, 75.12% of those in the CAG group had a lower education level, and 71.65% of those in the non-CAG group had a lower education level; 24.88% and 28.35% of those in the CAG and non-CAG groups, respectively, had higher education levels (P = 0.162). No significant difference in the distribution of the diagnosis of gastritis based on education level was observed (χ² = 1.95; P = 0.162). The prevalence of abdominal discomfort symptoms was 17.77% in the CAG group and 22.03% in the non-CAG group, which was not statistically significant (P = 0.058). With respect to lifestyle habits, long-term smokers accounted for 34.25% of the CAG group, which was higher than the 22.65% in the non-CAG group (P < 0.001). Long-term alcohol drinkers accounted for 19.71% of the CAG group and 16.33% of the non-CAG group, but the difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.118). In addition, long-term tea drinkers accounted for 32.63% of the CAG group, which was higher than the 26.81% in the non-CAG group (P = 0.023). In terms of dietary preferences, 14.54% of the participants in the CAG group preferred very cold or very hot food, similar to 14.48% in the non-CAG group (P = 0.978). Excessive salt intake was reported by 5.65% of the patients in the CAG group and 4.01% of the patients in the non-CAG group (P = 0.170). Hypertension was present in 35.06% of the patients in the CAG group and 32.51% of those in the non-CAG group (P = 0.338). Diabetes was present in 10.34% of the patients in the CAG group and 9.86% of the patients in the non-CAG group (P = 0.778). A family history of cancer was reported by 31.02% of the patients in the CAG group and 30.35% in the non-CAG group (P = 0.798). A family history of GC was reported by 12.44% of the patients in the CAG group, which was higher than the 9.09% reported in the non-CAG group (P = 0.054; Table 2). In summary, compared with the non-CAG group, the CAG group had significantly lower PGR levels and a higher rate of H. pylori infection and was older. A significant sex difference was noted, with a greater proportion of males in the CAG group. Otherwise, the proportions of long-term smokers and tea drinkers were significantly greater in the CAG group.

| Variables | Total (n = 1268) | Non-CAG (n = 649) | CAG (n = 619) | Statistic | P value |

| PGR, M (Q1, Q3) | 11.10 (8.57, 13.60) | 12.10 (10.10, 14.20) | 9.81 (7.33, 12.35) | Z1 = -10.79 | < 0.001a |

| Age (year), M (Q1, Q3) | 57.00 (52.00, 63.00) | 56.00 (50.00, 61.00) | 59.00 (53.50, 64.00) | Z1 = -6.28 | < 0.001a |

| BMI (kg/m2), M (Q1, Q3) | 23.44 (21.50, 25.39) | 23.38 (21.36, 25.39) | 23.51 (21.63, 25.44) | Z1 = -0.30 | 0.762 |

| Sleep, M (Q1, Q3) | 7.00 (6.00, 8.00) | 7.00 (6.00, 8.00) | 7.00 (6.00, 8.00) | Z1 = -0.85 | 0.394 |

| Gender | χ2 = 11.89 | < 0.001a | |||

| Male | 532 (41.96) | 242 (37.29) | 290 (46.85) | ||

| Female | 736 (58.04) | 407 (62.71) | 329 (53.15) | ||

| Education level | χ2 = 1.95 | 0.162 | |||

| Junior high school or below | 930 (73.34) | 465 (71.65) | 465 (75.12) | ||

| Above junior high school | 338 (26.66) | 184 (28.35) | 154 (24.88) | ||

| Symptoms | χ2 = 3.61 | 0.058 | |||

| None | 1015 (80.05) | 506 (77.97) | 509 (82.23) | ||

| Present | 253 (19.95) | 143 (22.03) | 110 (17.77) | ||

| Smoke | χ2 = 21.00 | < 0.001a | |||

| None | 909 (71.69) | 502 (77.35) | 407 (65.75) | ||

| Present | 359 (28.31) | 147 (22.65) | 212 (34.25) | ||

| Long-term tea drinking history2 | χ2 = 5.15 | 0.023a | |||

| None | 892 (70.35) | 475 (73.19) | 417 (67.37) | ||

| Present | 376 (29.65) | 174 (26.81) | 202 (32.63) | ||

| Dietary temperature preference | χ2 = 0.00 | 0.978 | |||

| Moderate temperature | 1084 (85.49) | 555 (85.52) | 529 (85.46) | ||

| Overly hot or cold | 184 (14.51) | 94 (14.48) | 90 (14.54) | ||

| Salt intake | χ2 = 1.88 | 0.170 | |||

| Normal or less | 1207 (95.19) | 623 (95.99) | 584 (94.35) | ||

| Excessive | 61 (4.81) | 26 (4.01) | 35 (5.65) | ||

| Drink | χ2 = 2.45 | 0.118 | |||

| None | 1040 (82.02) | 543 (83.67) | 497 (80.29) | ||

| Present | 228 (17.98) | 106 (16.33) | 122 (19.71) | ||

| Fruit | χ2 = 10.48 | 0.001a | |||

| Less than 5 times per week | 617 (48.66) | 287 (44.22) | 330 (53.31) | ||

| Greater than 5 times per week | 651 (51.34) | 362 (55.78) | 289 (46.69) | ||

| Asleep | χ2 = 0.99 | 0.321 | |||

| None | 893 (70.43) | 449 (69.18) | 444 (71.73) | ||

| Present | 375 (29.57) | 200 (30.82) | 175 (28.27) | ||

| Hypertension | χ2 = 0.92 | 0.338 | |||

| None | 840 (66.25) | 438 (67.49) | 402 (64.94) | ||

| Present | 428 (33.75) | 211 (32.51) | 217 (35.06) | ||

| Diabetes | χ2 = 0.08 | 0.778 | |||

| None | 1140 (89.91) | 585 (90.14) | 555 (89.66) | ||

| Present | 128 (10.09) | 64 (9.86) | 64 (10.34) | ||

| Tumor | 0.798 | ||||

| None | 879 (69.32) | 452 (69.65) | 427 (68.98) | ||

| Present | 389 (30.68) | 197 (30.35) | 192 (31.02) | ||

| Gastric | χ2 = 3.71 | 0.054 | |||

| None | 1132 (89.27) | 590 (90.91) | 542 (87.56) | ||

| Present | 136 (10.73) | 59 (9.09) | 77 (12.44) | ||

| H. pylori | χ2 = 314.29 | < 0.001a | |||

| Negative | 616 (48.58) | 473 (72.88) | 143 (23.10) | ||

| Positive | 652 (51.42) | 176 (27.12) | 476 (76.90) |

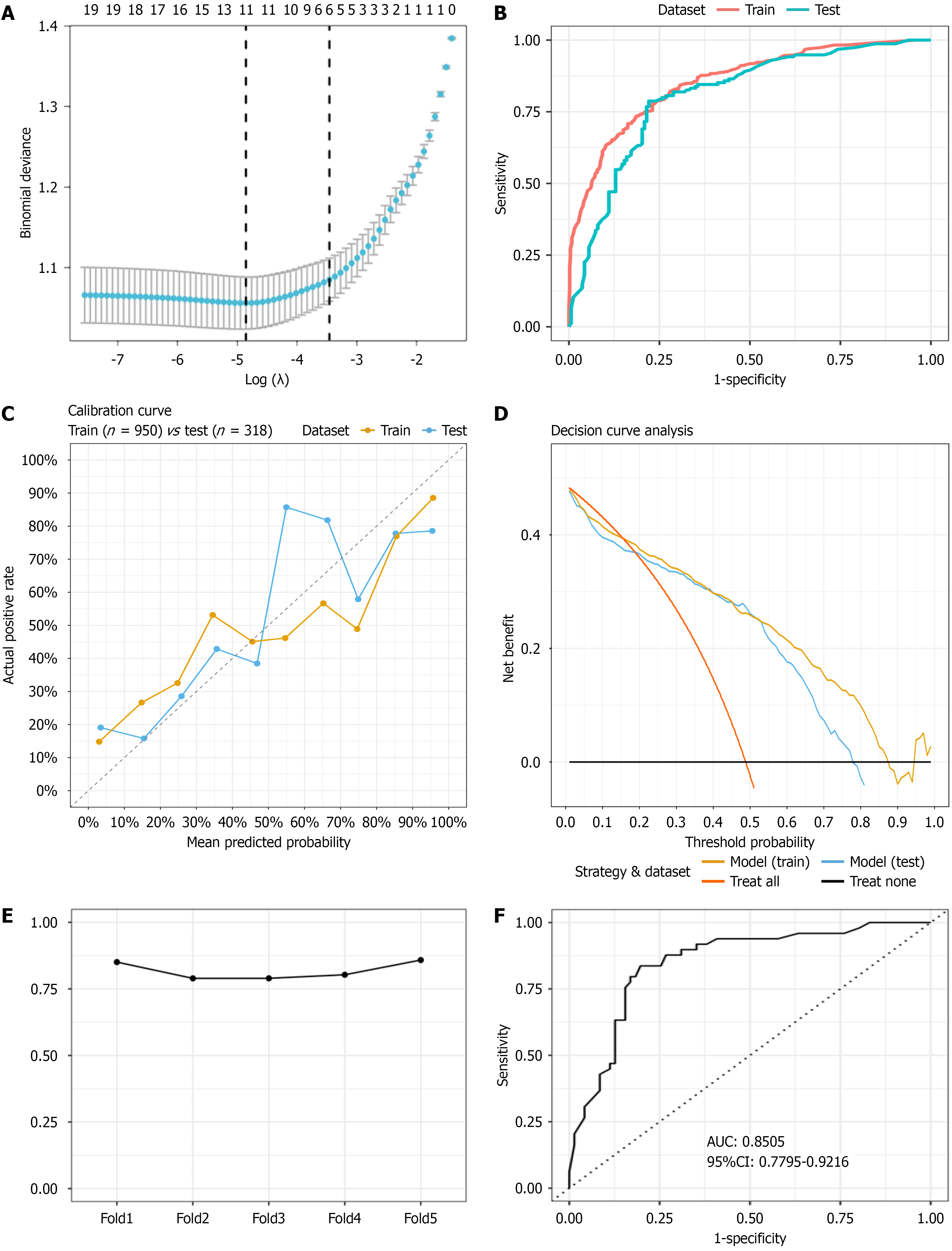

The 1268 enrolled patients were divided into a training set (n = 950) and a testing set (n = 318). LASSO regression, a penalized estimation method, was used to construct an optimization objective function with a penalty term, achieving both variable selection and model complexity adjustment. LASSO regression (λ.1se = 0.031458; Figure 2A) revealed six key features for CAG, namely, H. pylori status, PGR, smoking history, alcohol consumption history, age, and family history of GC. These six key variables were ultimately included in the model construction.

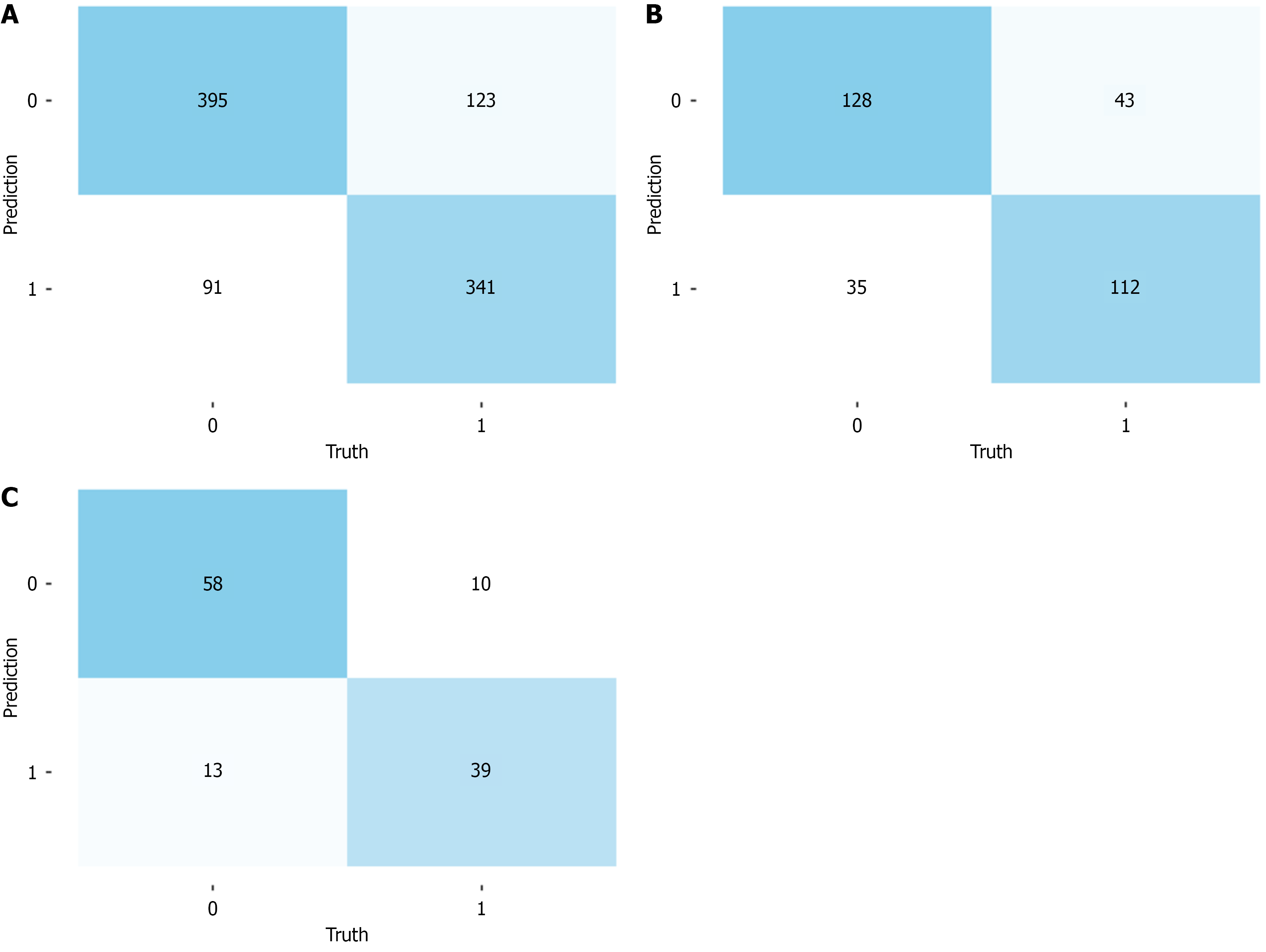

In this study, a 5-fold repeated training model was constructed and evaluated using the AUC[14], specificity, and sensitivity for both the training and testing sets. The model achieved an AUC of 0.8542 (95%CI: 0.8307-0.8777) in the training set (Figure 2B). The confusion matrix for the training set revealed that the model identified 341 true positives, 395 true negatives, 91 false positives, and 123 false negatives, with a specificity of 81.27% (95%CI: 77.46%-84.59%) and a sensitivity of 73.49% (95%CI: 69.18%-77.4%; Figure 3A). In the testing set, the AUC was 0.8073 (95%CI: 0.759-0.8557; Figure 2B). The confusion matrix for the testing set revealed 112 true positives, 128 true negatives, 35 false positives, and 43 false negatives, with a specificity of 78.53% (95%CI: 71.27%-84.4%) and a sensitivity of 72.26% (95%CI: 64.40%-78.99%; Figure 3B). The clinical utility of the model was assessed using calibration curves and decision curve analysis, which revealed stable performance between the training and testing sets (Figure 2C and D). The stability validation based on 5-fold cross-validation showed an average AUC of 0.818, which also indicated that the model’s performance was stable (Figure 2E). Finally, we compared the predictive performance between our random forest model and the traditional logistic regression model. The results indicated that our random forest model slightly outperformed the logistic regression model on both the training and testing sets (Table 3).

| Data | Model | AUC (95%CI) | Sensitivity (95%CI) | Specificity (95%CI) |

| Train | Random forest | 0.8542 (0.8307-0.8777) | 0.7349 (0.6918-0.774) | 0.8127 (0.7746-0.8459) |

| Logistic | 0.8208 (0.7940-0.8475) | 0.7284 (0.6889-0.7679) | 0.7802 (0.7425-0.8179) | |

| Test | Random forest | 0.8073 (0.759-0.8557) | 0.7226 (0.644-0.7899) | 0.7853 (0.7127-0.844) |

| Logistic | 0.8064 (0.7587-0.8540) | 0.7178 (0.6487-0.7869) | 0.7806 (0.7155-0.8458) |

To validate the predictive ability of the model, a cohort of 120 subjects from an early cancer screening program in another city within the province was selected for external validation. The results of the external validation cohort analysis revealed that the model achieved an AUC of 0.8505 (95%CI: 0.7795-0.9216; Figure 2F). The confusion matrix revealed 39 true positives, 58 true negatives, 13 false positives, and 10 false negatives, with a specificity of 81.69% (95%CI: 70.36%-89.52%) and a sensitivity of 79.59% (95%CI: 65.24%-89.28%; Figure 3C). Although the external dataset of this study demonstrated that the model has a certain degree of stability and generalization ability, but the external set is small and the precision of these estimates is limited.

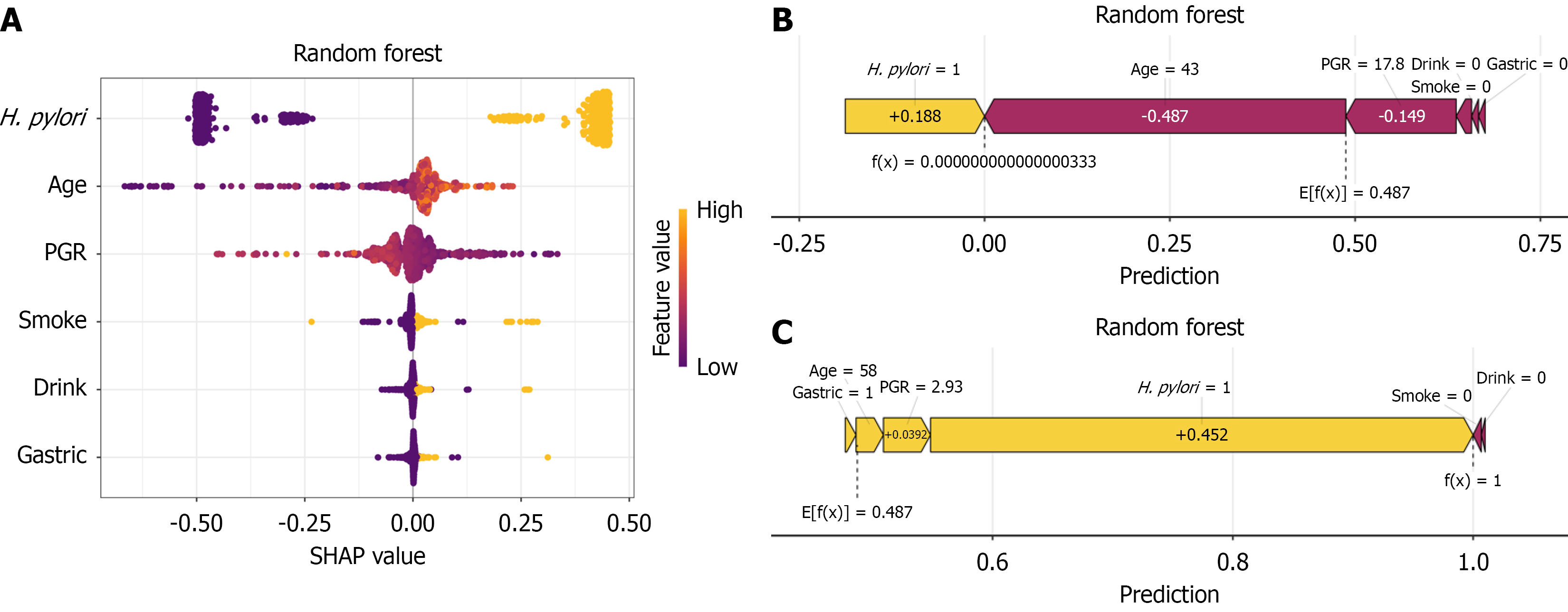

Using the SHAP interpretability framework[15], this study systematically analyzed the decision-making mechanism of the random forest model for predicting CAG risk. Features were ranked by importance from high to low: H. pylori infection status, age, pepsinogen ratio, smoking history, alcohol consumption history, and family history of GC. Positive H. pylori status, decreased PGR, advanced age, long-term alcohol consumption, long-term smoking, and a family history of GC contributed positively to the prediction, significantly increasing CAG risk (Figure 4A). To further understand the model’s decision making at the individual level, we conducted a detailed interpretability analysis of the two representative samples shown in Figure 4B and C. A 43-year-old subject with no history of smoking, alcohol consumption, or a family history of GC who was positive for serum H. pylori antibodies and who had a PGR of 17.8 is shown in Figure 3B. This subject had a low SHAP value, and the model predicted a tendency toward non-atrophic gastritis. A 58-year-old subject with no history of smoking or alcohol consumption, a family history of GC, a positive serum H. pylori antibody test, and a PGR of 2.93 is shown in Figure 3C. This subject had a high SHAP value, and the model predicted a tendency toward atrophic gastritis. By visualizing the SHAP values for these samples, we can clearly identify the specific impact of each feature on the model's predictions for these particular instances.

The final prediction model was integrated into a web application for use in clinical settings. By inputting the actual values for the six features required by the model, the application can automatically predict a patient's CAG risk. The web application can be accessed online at the following link: https://hanjl.shinyapps.io/CAGpredictionRF/ (Supplementary Figure 1).

In recent years, GC prediction models based on metabolomics, radiomics, and endoscopic data have made significant breakthroughs in clinical application. Some studies have constructed high-precision GC diagnostic and prognostic models by integrating plasma metabolite features with machine learning algorithms[16], and the performance of these models is significantly superior to that of traditional tumor markers and clinical judgment. These models not only accurately distinguish early GC but also achieve risk stratification through dynamic monitoring of metabolite changes, providing a basis for personalized treatment. Although the severity of CAG is positively correlated with GC risk[17], models that precisely predict the risk of progression from chronic gastritis to atrophic intestinal metaplasia are currently lacking. By integrating multimodal data such as demographic characteristics, lifestyle, family history, and serological markers to construct a risk assessment system, this study provides reliable clinical evidence for screening high-risk populations for CAG before endoscopy, potentially enhancing the overall effectiveness of the GC prevention and control system.

In this study, a random forest algorithm was used to construct a machine learning prediction model, and the risk factors and predictive efficacy for CAG were systematically explored. LASSO regression was used to select the core predictors closely related to CAG. The results revealed that H. pylori infection, age, PGR, smoking history, alcohol consumption history, and family history of GC were closely associated with CAG.

As one of the core predictors identified by our model, H. pylori infection is the most significant cause of chronic gastritis[7]. The adhesion and virulence of H. pylori disrupt the mucosal barrier. H. pylori also regulate the release of inflammatory factors, causing chronic inflammation and immune dysregulation. Through multitarget, multilevel pathogenic mechanisms, persistent H. pylori infection ultimately leads to the destruction and functional loss of gastric mucosal glands, representing a core driver of CAG development[18]. A prospective study on CAG revealed that two-thirds of patients had evidence of H. pylori infection[19]. A meta-analysis revealed that the incidence of CAG in H. pylori -positive patients was five times greater than that in H. pylori-negative patients, indicating a close relationship between the development of CAG and H. pylori infection[20]. Our SHAP analysis of the prediction model also revealed that H. pylori positivity is the most important feature for predicting CAG risk, which is consistent with previous findings.

Age, the second most important core predictor in our model, has been confirmed in multiple studies to be associated with CAG risk. The GC management guidelines issued by the British Society of Gastroenterology clearly state a positive correlation between the risk of CAG and age[5]. A United States study analyzing more than 480000 subjects who underwent endoscopy over a six-year period revealed a clear age-related trend in the prevalence of chronic active gastritis, which increased from 5% at age 20 to 12% at age 40. Similarly, the prevalence of CAG increases with age, from approximately 5% at age 60 to 10% at age 80, with an approximate 5% increase for every subsequent decade of life[21]. Notably, this age-dependent characteristic of CAG onset is closely related to H. pylori infection. The cumulative duration of persistent H. pylori infection, coupled with increasing damage to the gastric mucosa from inflammation, leads to a continuous increase in the risk of CAG[22].

PGR is the third core predictor in our model and serves as a sensitive indicator for assessing gastric mucosal function. Its decreased expression is closely related to the onset of CAG[23]. PGR serum concentrations objectively reflect the secretory capacity of the gastric mucosal glands. Consequently, serum PGR concentrations serve as an important biological marker for assessing the presence of extensive glandular atrophy in the gastric mucosa[24]. Our analysis also revealed that as the PGR decreases, the risk of CAG progressively increases.

Diet and lifestyle are important factors influencing the progression and evolution of chronic gastritis, especially CAG[7]. Our study included variables closely related to lifestyle habits, such as smoking history, alcohol consumption history, tea consumption history, dietary temperature preference, fresh fruit intake frequency, salt intake, and sleep duration and quality. The results suggest a possible association among smoking, alcohol consumption, and CAG. A community survey revealed that 12.5% of residents with chronic diseases smoked daily, with chronic gastritis being the most prevalent condition[25]. Harmful substances in cigarettes can cause vasoconstriction in the gastric submucosa, leading to poor blood circulation in the stomach and interfering with prostaglandin synthesis, thereby damaging the gastric mucosal barrier and increasing the likelihood of CAG[26]. Our study revealed that long-term alcohol consumption increases the risk of CAG; however, current research on the impact of alcohol on precancerous gastric lesions is inconclusive. A large-scale cohort study in a Korean population revealed that even low levels of alcohol consumption independently increased the risk of developing CAG and gastrointestinal metaplasia[27]. A retrospective study in Japan also revealed a greater trend toward atrophy in individuals who consumed ≥ 20 g of alcohol daily for ≥ 5 days a week. Sake drinkers had a greater degree of atrophy, whereas wine drinkers had a relatively low degree[28]. Previous studies have indicated that excessive alcohol consumption directly damages the gastric mucosa. This damage can also promote H. pylori infection and accelerate the progression of atrophic gastritis[29]. However, some studies have suggested that moderate alcohol consumption might have a protective effect on CAG through mechanisms such as promoting H. pylori clearance[30]. Future research requires larger cohorts and more detailed studies to explore the impact of alcohol consumption on gastric mucosal atrophy. Although some literature suggests that long-term tea consumption, high-salt diets, and the intake of fresh fruits and vegetables can also affect the development of CAG[31-33], our study did not identify tea consumption habits, fresh fruit intake frequency, or salt intake as key predictive features for CAG risk. Possible reasons include the use of simplified questionnaires that may miss crucial exposure information and the existence of dose-effect thresholds for some exposure factors that may not have been reached by the subjects in our study. Additionally, confounding factors or compensatory mechanisms of protective factors that were not effectively captured by the statistical model might have been overlooked. The role of these factors in the risk of CAG requires further in-depth prospective studies to be validated by dynamically observing the relationship between lifestyle changes and the progression of gastric mucosal pathology.

As an important genetic susceptibility factor for GC, a family history of GC may increase the risk of GC and its precancerous lesions through mechanisms such as epigenetic modifications or remodeling of the tumor microenvironment[34]. However, the existing epidemiological evidence is controversial. In East Asia, where the H. pylori infection rate has long been high (approximately 60%-90%)[35], a family history of GC may more likely reflect the familial clustering of H. pylori infection rather than an independent genetic susceptibility marker. In the prediction model constructed in this study, although a family history of GC was considered an independent risk factor for CAG, its contribution to overall risk pre

The advantage of the random forest model lies not only in its high accuracy and robustness but also in its ability to assess feature importance, which helps identify key predictors and potential risk factors, providing significant guidance for clinical practice. The importance of building disease prediction models is to identify high-risk patients and reduce the risk for individuals who might fall into high-risk categories, thereby benefiting patients as a whole. Therefore, the clinical interpretability of machine learning models is highly valuable in medical practice. The Shiny platform is widely used in the development of prediction models because it can generate interactive graphical interfaces for users locally or online, which is beneficial for presenting research findings to a broad audience[37,38]. In this study, a machine learning model based on random forest was constructed to predict the risk of CAG in patients. For clinical application, we converted the prediction model into a web-based calculator using the Shiny application. Health care professionals can use this calculator to intuitively obtain a patient’s predicted risk of CAG, making it convenient for clinical use and promotion.

This study has several limitations. Firstly, our cohort population was based on the GC screening recommendations from the Chinese population GC risk management public guidelines (2023 edition)[17], which included only individuals aged 40 years and above and excluded individuals under the age of 40. As a result, the proportion of CAG patients in our model cohort was much higher (48.8%) than the prevalence of CAG in real-world. This discrepancy may affect the interpretation of the model’s performance in clinical practice. For example, in real-world populations with a lower disease prevalence, the clinical value of the model may be significantly reduced, leading to an increase in false-positive results. The model we developed may be more applicable for risk stratification and auxiliary identification in older populations in high-risk areas. In the future, we will use weighting, resampling, and other techniques to simulate real-world disease rates during model training, and include populations from different disease risk areas to further enhance the model's ge

In this study, a predictive tool for CAG was successfully developed by constructing a machine learning model based on the random forest algorithm. The model demonstrates high prediction accuracy and can effectively predict CAG by identifying and evaluating key predictive factors. After further optimization and promotion, the model constructed in this study is expected to enable early intervention at the precancerous stage for GC prevention and control, assist in the precise identification and scientific management of high-risk populations, and thus effectively reduce the incidence risk of GC.

| 1. | Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394-424. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53206] [Cited by in RCA: 56651] [Article Influence: 7081.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (134)] |

| 2. | Cheng HC, Yang YJ, Yang HB, Tsai YC, Chang WL, Wu CT, Kuo HY, Yu YT, Yang EH, Cheng WC, Chen WY, Sheu BS. Evolution of the Correa's cascade steps: A long-term endoscopic surveillance among non-ulcer dyspepsia and gastric ulcer after H. pylori eradication. J Formos Med Assoc. 2023;122:400-410. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Yin J, Yi J, Yang C, Xu B, Lin J, Hu H, Wu X, Shi H, Fei X. Weiqi Decoction Attenuated Chronic Atrophic Gastritis with Precancerous Lesion through Regulating Microcirculation Disturbance and HIF-1α Signaling Pathway. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2019;2019:2651037. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Song H, Ekheden IG, Zheng Z, Ericsson J, Nyrén O, Ye W. Incidence of gastric cancer among patients with gastric precancerous lesions: observational cohort study in a low risk Western population. BMJ. 2015;351:h3867. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 182] [Cited by in RCA: 219] [Article Influence: 19.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Banks M, Graham D, Jansen M, Gotoda T, Coda S, di Pietro M, Uedo N, Bhandari P, Pritchard DM, Kuipers EJ, Rodriguez-Justo M, Novelli MR, Ragunath K, Shepherd N, Dinis-Ribeiro M. British Society of Gastroenterology guidelines on the diagnosis and management of patients at risk of gastric adenocarcinoma. Gut. 2019;68:1545-1575. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 425] [Cited by in RCA: 456] [Article Influence: 65.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Dinis-Ribeiro M, Lopes C, da Costa-Pereira A, Guilherme M, Barbosa J, Lomba-Viana H, Silva R, Moreira-Dias L. A follow up model for patients with atrophic chronic gastritis and intestinal metaplasia. J Clin Pathol. 2004;57:177-182. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Chinese Society of Gastroenterology, Chinese Society of Digestive Oncology. [Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of chronic gastritis in China (2022, Shanghai)]. Zhonghua Xiaohua Zazhi. 2023;43:145-175. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 8. | Forte GC, Altmayer S, Silva RF, Stefani MT, Libermann LL, Cavion CC, Youssef A, Forghani R, King J, Mohamed TL, Andrade RGF, Hochhegger B. Deep Learning Algorithms for Diagnosis of Lung Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14:3856. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Taninaga J, Nishiyama Y, Fujibayashi K, Gunji T, Sasabe N, Iijima K, Naito T. Prediction of future gastric cancer risk using a machine learning algorithm and comprehensive medical check-up data: A case-control study. Sci Rep. 2019;9:12384. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Zhao J, Tian W, Zhang X, Dong S, Shen Y, Gao X, Yang M, Lv J, Hu F, Han J, Zhan Q, An F. The diagnostic value of serum trefoil factor 3 and pepsinogen combination in chronic atrophic gastritis: a retrospective study based on a gastric cancer screening cohort in the community population. Biomarkers. 2024;29:384-392. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Frost HR, Amos CI. Gene set selection via LASSO penalized regression (SLPR). Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:e114. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Jiang C, Xiu Y, Qiao K, Yu X, Zhang S, Huang Y. Prediction of lymph node metastasis in patients with breast invasive micropapillary carcinoma based on machine learning and SHapley Additive exPlanations framework. Front Oncol. 2022;12:981059. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Breiman L. Random Forests. Mach Learn. 2001;45:5-32. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56052] [Cited by in RCA: 36278] [Article Influence: 2790.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Obuchowski NA, Bullen JA. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves: review of methods with applications in diagnostic medicine. Phys Med Biol. 2018;63:07TR01. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 136] [Cited by in RCA: 327] [Article Influence: 40.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Ponce-Bobadilla AV, Schmitt V, Maier CS, Mensing S, Stodtmann S. Practical guide to SHAP analysis: Explaining supervised machine learning model predictions in drug development. Clin Transl Sci. 2024;17:e70056. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 185] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Chen Y, Wang B, Zhao Y, Shao X, Wang M, Ma F, Yang L, Nie M, Jin P, Yao K, Song H, Lou S, Wang H, Yang T, Tian Y, Han P, Hu Z. Metabolomic machine learning predictor for diagnosis and prognosis of gastric cancer. Nat Commun. 2024;15:1657. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 50.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 17. | Chinese Gastric Cancer Association of Chinese Anti-Cancer Association; Chinese Society of Upper Gastrointestinal Surgeons of Chinese Medical Doctor Association; Chinese Health Risk Management Collaboration-Gastric Cancer Group. [Chinese Guideline on Risk Management of Gastric Cancer in the General Public(2023 Edition)]. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2023;103:2837-2849. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Fischbach W, Malfertheiner P. Helicobacter Pylori Infection. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2018;115:429-436. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 19. | Annibale B, Negrini R, Caruana P, Lahner E, Grossi C, Bordi C, Delle Fave G. Two-thirds of atrophic body gastritis patients have evidence of Helicobacter pylori infection. Helicobacter. 2001;6:225-233. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Adamu MA, Weck MN, Gao L, Brenner H. Incidence of chronic atrophic gastritis: systematic review and meta-analysis of follow-up studies. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25:439-448. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 21. | Genta RM, Turner KO, Sonnenberg A. Demographic and socioeconomic influences on Helicobacter pylori gastritis and its pre-neoplastic lesions amongst US residents. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;46:322-330. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Chinese Society of Gastroenterology; Cancer Collaboration Group of Chinese Society of Gastroenterology; Chinese Medical Association. Guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of chronic gastritis in China (2022, Shanghai). J Dig Dis. 2023;24:150-180. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Du QP, Cao JB, Guo HB, Li HR. [Correlation between pepsinogen subgroup determination and atrophic gastritis with cost-effectiveness analysis]. Zhongguo Yaowu Jingjixue. 2011;1:64-71. |

| 24. | Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O'Morain CA, Gisbert JP, Kuipers EJ, Axon AT, Bazzoli F, Gasbarrini A, Atherton J, Graham DY, Hunt R, Moayyedi P, Rokkas T, Rugge M, Selgrad M, Suerbaum S, Sugano K, El-Omar EM; European Helicobacter and Microbiota Study Group and Consensus panel. Management of Helicobacter pylori infection-the Maastricht V/Florence Consensus Report. Gut. 2017;66:6-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2220] [Cited by in RCA: 2085] [Article Influence: 231.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 25. | Sun HY, Sun YM, Sun JY, Dong CQ, Chen H, Shi JD. [Analysis of health status and influencing factors among community residents based on an intelligent health monitoring system]. Zhonghua Huli Zazhi. 2020;55:1836-1843. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 26. | Wirth HP, Yang M. Different Pathophysiology of Gastritis in East and West? A Western Perspective. Inflamm Intest Dis. 2016;1:113-122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Kim K, Chang Y, Ahn J, Yang HJ, Ryu S. Low Levels of Alcohol Consumption and Risk of Intestinal Metaplasia: A Cohort Study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2020;29:2633-2641. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Ozeki K, Hada K, Wakiya Y. Factors Influencing the Degree of Gastric Atrophy in Helicobacter pylori Eradication Patients with Drinking Habits. Microorganisms. 2024;12:1398. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Zhang L, Eslick GD, Xia HH, Wu C, Phung N, Talley NJ. Relationship between alcohol consumption and active Helicobacter pylori infection. Alcohol Alcohol. 2010;45:89-94. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Gao L, Weck MN, Stegmaier C, Rothenbacher D, Brenner H. Alcohol consumption and chronic atrophic gastritis: population-based study among 9,444 older adults from Germany. Int J Cancer. 2009;125:2918-2922. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Feinle-Bisset C, Azpiroz F. Dietary and lifestyle factors in functional dyspepsia. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;10:150-157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Duncanson K, Burns G, Pryor J, Keely S, Talley NJ. Mechanisms of Food-Induced Symptom Induction and Dietary Management in Functional Dyspepsia. Nutrients. 2021;13:1109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Nomura A, Grove JS, Stemmermann GN, Severson RK. A prospective study of stomach cancer and its relation to diet, cigarettes, and alcohol consumption. Cancer Res. 1990;50:627-631. [PubMed] |

| 34. | Yaghoobi M, McNabb-Baltar J, Bijarchi R, Hunt RH. What is the quantitative risk of gastric cancer in the first-degree relatives of patients? A meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:2435-2442. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 35. | Zhou XZ, Lyu NH, Zhu HY, Cai QC, Kong XY, Xie P, Zhou LY, Ding SZ, Li ZS, Du YQ; National Clinical Research Center for Digestive Diseases (Shanghai), Gastrointestinal Early Cancer Prevention & Treatment Alliance of China (GECA), Helicobacter pylori Study Group of Chinese Society of Gastroenterology and Chinese Alliance for Helicobacter pylori Study. Large-scale, national, family-based epidemiological study on Helicobacter pylori infection in China: the time to change practice for related disease prevention. Gut. 2023;72:855-869. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 36.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Hansford S, Kaurah P, Li-Chang H, Woo M, Senz J, Pinheiro H, Schrader KA, Schaeffer DF, Shumansky K, Zogopoulos G, Santos TA, Claro I, Carvalho J, Nielsen C, Padilla S, Lum A, Talhouk A, Baker-Lange K, Richardson S, Lewis I, Lindor NM, Pennell E, MacMillan A, Fernandez B, Keller G, Lynch H, Shah SP, Guilford P, Gallinger S, Corso G, Roviello F, Caldas C, Oliveira C, Pharoah PD, Huntsman DG. Hereditary Diffuse Gastric Cancer Syndrome: CDH1 Mutations and Beyond. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1:23-32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 481] [Cited by in RCA: 508] [Article Influence: 46.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Teng X, Han K, Jin W, Ma L, Wei L, Min D, Chen L, Du Y. Development and validation of an early diagnosis model for bone metastasis in non-small cell lung cancer based on serological characteristics of the bone metastasis mechanism. EClinicalMedicine. 2024;72:102617. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Zhen M, Chen H, Lu Q, Li H, Yan H, Wang L. Machine Learning-Based Predictive Model for Mortality in Female Breast Cancer Patients Considering Lifestyle Factors. Cancer Manag Res. 2024;16:1253-1265. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/