INTRODUCTION

Gastric cancer (GC) ranks fifth in incidence and fifth in mortality among cancers globally[1]. Pathogenic factors of GC include Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection, tobacco use, alcohol intake, age, high salt intake, and insufficient fruit and vegetable intake. Among them, H. pylori infection represents the major risk factor for GC. Nearly 50% of the global population are infected with H. pylori, and almost all cases of GC are associated with H. pylori infection[2,3]. Some studies show that eradication of H. pylori can reduce the incidence of GC. Because early H. pylori infection usually lacks obvious symptoms, patients often seek medical care at the stage of chronic gastritis or intestinal metaplasia. H. pylori infection causes alterations in the immune microenvironment, epigenetic regulation, DNA damage, and so on, resulting in cellular malignant transformation[4]. Although H. pylori may have been eradicated after antibiotic treatment, the damage already caused to cells and tissues means that some patients still progress to GC[5]. However, due to the lack of follow-up and effective diagnostic methods for this high-risk population, many of these patients are diagnosed with GC at invasive or metastatic stages, for which the five-year survival rate is below 30%[6].

For early-stage GC patients, endoscopic diagnosis is the primary method. In East Asia, this approach can detect over 50% of early GC cases, with a five-year survival rate of over 90% after treatment[7,8]. Because of the invasiveness of endoscopy and its limited accessibility worldwide, a large proportion of patients are still diagnosed at advanced stages[9]. Therefore, to improve the survival of both patients who have cleared H. pylori infection and other high-risk populations, the development of novel diagnostic biomarkers is urgently needed.

Non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) are a class of RNAs that do not encode proteins, including microRNAs (miRNAs), circular RNAs (circRNAs), long ncRNAs (lncRNAs), and others[10]. They can regulate gene expression through various mechanisms and are involved in tumor initiation, progression, and drug resistance. Due to their close association with tumors, ncRNAs have been used as biomarkers for disease diagnosis and prognosis. This editorial describes ncRNA biomarkers related to H. pylori infection in GC, aiming to explore their potential application in the early diagnosis of H. pylori-associated GC.

MIRNAS AND GC DIAGNOSIS

MiRNAs are endogenous short ncRNAs (containing about 22 nucleotides) that function as epigenetic regulators and play a pivotal role in post-transcriptional gene regulation. MiRNAs target cytosolic mRNAs by binding to complementary sequences with the 3’-untranslated regions (3’-UTRs), the 5’-untranslated regions, or protein-coding regions. In GC, some miRNAs are dysregulated after H. pylori infection and are associated with GC carcinogenesis.

MiR-584 is upregulated following H. pylori infection and exhibits increased expression during the early stages of tumor development, but it is downregulated in advanced GC with invasiveness and lymph node metastasis, suggesting that it may serve as an early biomarker for GC[11]. Wang et al[12] analyzed clinical samples and found that among the highly expressed miRNAs in H. pylori-positive samples, miR-143-3p was associated with tumor stage, lymph node metastasis, as well as higher overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival. Through binding to the 3’-UTR of AKT2, miR-143-3p negatively regulates cell growth, apoptosis, migration, and invasion of GC. Additionally, miRNAs in body fluids are also suitable for the early diagnosis of GC. The serum levels of miR-18a-3p and miR-4286 were upregulated in H. pylori-infected GC samples. MiR-18a-3p is positively correlated with the depth of invasion; miR-4286 was positively associated with tumor grade, tumor size, and lymph node metastasis. These observations indicate that miR-18a-3p and miR-4286 have potential as biomarkers in H. pylori-related GC[13]. Song et al[14] reported that miR-7 and miR-153 are downregulated in H. pylori-infected GC patients, indicating their potential as diagnostic biomarkers for early-stage GC. In addition, Iwasaki et al[15] found that miR-6807-5p and miR-6856-5p could be detected in urine and serve as independent biomarkers for distinguishing GC. A combined diagnostic approach that integrates miR-6807-5p and miR-6856-5p with H. pylori infection status showed high diagnostic accuracy, effectively distinguishing GC patients from healthy individuals. Furthermore, So et al[7] established that a 12-miRNA biomarker panel combined with serum profiles, patient age, H. pylori serology, and the pepsinogen I:II ratio significantly enhanced the diagnostic accuracy for GC, yielding an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.884 and a specificity of 69.4%, without compromising sensitivity. These findings highlight the value of multiplex biomarker integration in enhancing the reliability of GC detection.

The latest issue of the World Journal of Gastroenterology published an interesting paper titled “Helicobacter pylori-induced miR-136 is a potential predictor of early-stage gastric cancer”[16]. In this research, the authors first predicted that miR-136 interacts with PDCD11, using the TargetScan7.1 database. After that, they measured the expression levels of miR-136 and PDCD11 in human GC samples that were either positive or negative for H. pylori infection. The results showed that miR-136 was upregulated in H. pylori-positive GC samples, while PDCD11 was downregulated. Linear regression analysis revealed a significant negative correlation between miR-136 and PDCD11 at both the mRNA and protein levels. To further validate the relationship between miR-136 and PDCD11, the authors established an H. pylori infection model by co-culturing GC cells with H. pylori. They found that miR-136 expression was significantly upregulated, while PDCD11 expression was markedly downregulated in GC cell lines following H. pylori infection, suggesting a potential interaction between miR-136 and PDCD11 in GC cells.

Additionally, in vitro experiments were conducted to investigate the role of miR-136 in GC progression. Overexpression of miR-136 promoted the proliferation and migration of H. pylori-infected GC cells. A luciferase reporter assay using a plasmid carrying the PDCD11 promoter demonstrated that PDCD11 expression decreased following miR-136 overexpression, while PDCD11 expression increased after miR-136 inhibition. The same trend was also observed at the protein level. Furthermore, co-overexpression of miR-136 and PDCD11 suppressed the proliferation and migration induced by miR-136 overexpression, indicating that H. pylori-induced miR-136 promotes GC cell proliferation and migration by targeting PDCD11. In a GC mouse xenograft model, inhibition of miR-136 or co-overexpression of miR-136 and PDCD11 exhibited significant antitumor effects.

The authors also predicted that NF-κB regulates miR-136 expression through its promoter. A luciferase assay carrying the miR-136 promoter demonstrated that treatment with the NF-κB inhibitor Bay 11-7821 blocked H. pylori-induced miR-136 upregulation, suggesting that H. pylori infection upregulates miR-136 expression via NF-κB.

In summary, through bioinformatics analysis as well as in vitro and in vivo experiments, the authors identified the NF-κB/miR-136/PDCD11 axis as a regulator of GC cell growth and migration, providing a novel therapeutic target for GC. Furthermore, since miR-136 is specifically upregulated in H. pylori-infected GC tissues, it also holds potential as a biomarker for early-stage GC in H. pylori-infected patients.

CIRCRNAS AND GC DIAGNOSIS

CircRNAs are a class of single-stranded, covalently closed RNA molecules formed through back-splicing of mRNA or exon skipping. CircRNAs are relatively more stable and resistant to RNase degradation. They regulate cellular processes by acting as miRNA “sponges”, transcriptional regulators, or protein templates[17]. Abnormal expression of circRNAs has been observed in various tumors and is closely associated with tumor initiation, progression, and metastasis. Increasing evidence suggests that circRNAs may serve as promising candidate biomarkers for cancer diagnosis.

Many circRNAs associated with GC are aberrantly expressed following H. pylori infection. Zhao et al[18] found that circ-PGD (has-circ-0009735) is upregulated in both H. pylori infection and GC. Knockdown of circ-PGD can counteract epithelial-mesenchymal transition activation induced by H. pylori infection and reduce cell migration, whereas its overexpression promotes cell migration. Circ-PGD exacerbates the inflammatory response induced by H. pylori infection by promoting the expression of IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α through the phosphorylation of p65. Circ_0046854 is produced by the back-splicing of exons 10 and 11 of the ANKRD12 gene. Ma et al[19] reported that circ_0046854 is upregulated in clinical H. pylori-positive GC tissue samples. Furthermore, knockdown of circ_0046854 inhibited H. pylori-induced cell proliferation and apoptosis suppression via the circ_0046854/microRNA-511-3p/CSF1 axis. Zhang et al[20] used rTip-α to treat MKN28 cells to establish an H. pylori infection model and observed that circ-FNDC3B expression was upregulated, while miR-942 and miR-510 were downregulated. Simultaneously, CD44 and CDH1 were both upregulated at the mRNA level, suggesting that circ-FNDC3B promotes GC development following H. pylori infection by regulating gene expression through miR-942 and miR-510. Circ-15430, located within the ABL2 gene, is downregulated in H. pylori-positive GC tissues and in the MGC-803 cell line infected with H. pylori. Low expression of circ-15430 can reverse H. pylori-induced autophagy. Additionally, circ-15430 expression is decreased in GC tissues and cell lines, and knockout of circ-15430 promotes cell proliferation and migration while inhibiting apoptosis and autophagy via the miR-382-5p/ZCCHC14 axis[21]. Upregulation of circ-15430, together with H. pylori infection, contributes to GC development and may have potential for the early diagnosis of GC following H. pylori infection. Guo et al[22] found that in AGS and BGC823 cell lines, H. pylori infection upregulates circMAN1A2 expression in a CagA-independent manner. CircMAN1A2 promotes GC progression through the miR-1236-3p/MTA2 axis. Additionally, circMAN1A2 levels in tumor tissues from clinical patients were significantly higher than those in adjacent normal tissues, and its expression further increased with tumor progression. Moreover, plasma levels of circMAN1A2 in GC patients were significantly higher than those in healthy individuals, suggesting that circMAN1A2 could serve as a promising biomarker for GC.

LNCRNAS AND GC DIAGNOSIS

LncRNAs lack protein-coding potential and are typically defined as transcripts longer than 200 nucleotides. LncRNAs play key roles in cellular signaling and regulation, and their dysregulation has been observed in many diseases, including GC[23]. LINC00152 and LNCH19 are upregulated in both tumor tissues and serum samples of GC patients. Early investigations have demonstrated that the expression levels of LINC00152 and LNCH19 are positively correlated with the incidence of GC. Moreover, patients infected with H. pylori who exhibit elevated levels of LINC00152 or LNCH19 are at an increased risk of developing GC. Further research has revealed that LNCH19 facilitates GC progression following H. pylori infection by enhancing the NF-κB-mediated inflammatory response. This finding suggests that LINC00152 and LNCH19 may serve as potential diagnostic biomarkers for GC, particularly in patients infected with H. pylori[24,25]. Yang et al[26] found that XLOC-004122 and XLOC-014388 are downregulated in H. pylori-infected gastric mucosa, indicating their potential as early diagnostic biomarkers. Through analysis of public databases, one study confirmed that the lncRNAs RP11-169F17.1 and RP11-669N7.2 not only have potential as novel prognostic and diagnostic indicators for GC but also may play important roles in H. pylori-induced duodenal ulcers and gastritis[27]. Zhu et al[28], using microarrays on human gastric epithelial cells, identified several lncRNAs exhibiting aberrant expression following H. pylori infection. The lncRNAs with abnormal expression after H. pylori infection, including n345630, XLOC_004787, LINC00152, n378726, XLOC_005517, n408024, LINC00473, and XLOC_13370, were found to be upregulated, whereas XLOC_004787, n345630, LINC00473, and n378726 were downregulated. Jia et al[29] reported that the expression of THAP9-AS1 lncRNA increases in GC cells following H. pylori infection, and overexpression of THAP9-AS1 lncRNA promotes GC cell growth and migration. Zhou et al[30] found that lncRNA-AF147447 is downregulated following H. pylori infection; this lncRNA inhibits GC cell proliferation and metastasis by targeting MUC2 and miR-34c. Notably, high expression of HOXA-AS2 is significantly associated with larger tumor size, lymph node metastasis, and H. pylori infection in GC patients, suggesting that its expression level may be related to GC development. HOXA-AS2 is upregulated after H. pylori infection and promotes GC progression via the HOXA-AS2/miR-509-3p/MMD2 axis[31,32]. Lnc-PLCB1 is downregulated via METTL14-mediated m6A methylation and IRF2-mediated transcriptional regulation. The downregulation of lnc-PLCB1 promotes GC cell proliferation and migration, and its expression in GC tissues is lower than that in normal tissues[33]. Compared with non-tumor tissues, FOXD2-AS1 is significantly upregulated in tumor samples. High FOXD2-AS1 expression is also significantly associated with lymph node metastasis and H. pylori infection, suggesting that FOXD2-AS1 may serve as an effective biomarker for GC[34]. A study in an Iranian population indicated that lnc-OC1 is upregulated in GC tissues, and H. pylori-positive GC patients exhibit significantly higher Lnc-OC1 expression compared to H. pylori-negative patients[35].

CONCLUSION

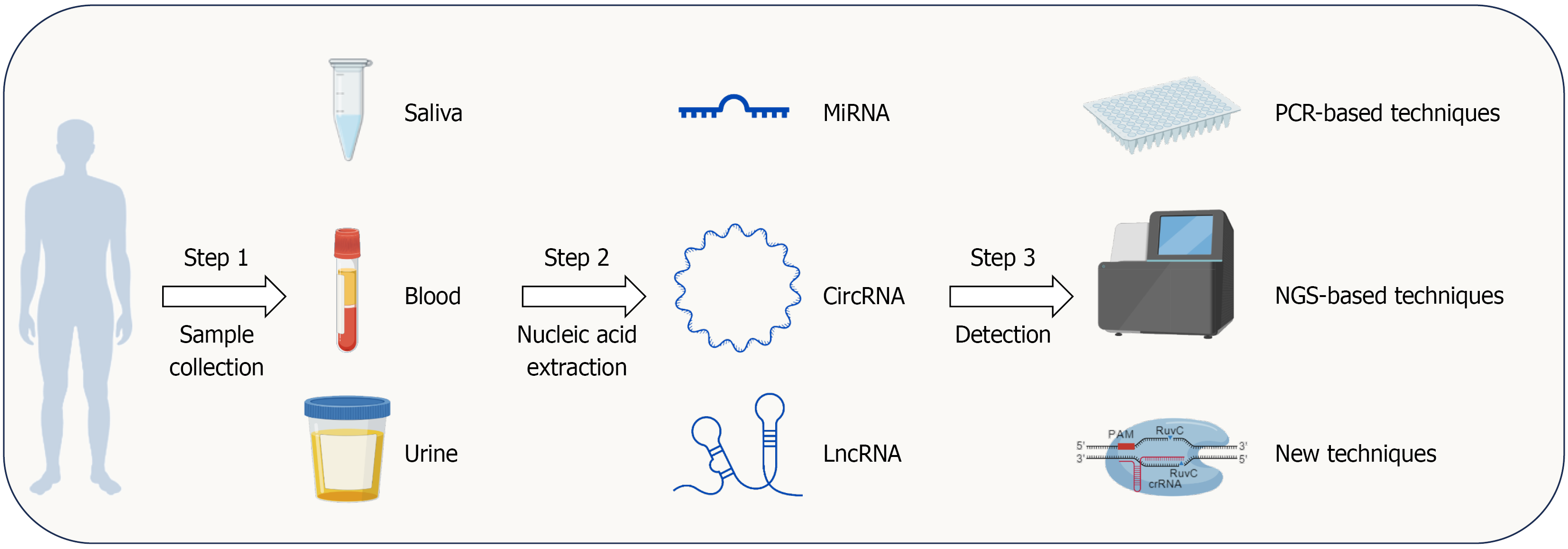

In this editorial, we discuss the role of ncRNAs in the early diagnosis of H. pylori-related GC. Multiple miRNAs are dysregulated in H. pylori-infected GC, including miR-584, miR-143-3p, miR-18a-3p, miR-204, and miR-163. Chen et al[16] further investigated the role of miR-136 in promoting tumor growth and metastasis. The study proposed the NF-κB/miR-136/PDCD11 axis, revealing its potential as a biomarker for the early detection of H. pylori-related GC. Additionally, many circRNAs are also dysregulated in H. pylori-infected GC, including circ-PGD, circ-0046854, circ-FNDC3B, circ-15430, circ-MAN1A2, and others. According to the Correa cascade, the progression of GC follows the following sequence: Normal gastric mucosa, chronic superficial gastritis, chronic atrophic gastritis, intestinal metaplasia, intraepithelial neoplasia, and intestinal-type GC[36]. H. pylori plays an inducing and accelerating role in this process. Moreover, H. pylori infection triggers host inflammation, which promotes tumorigenesis[6]. The combination of circ-PGD overexpression and H. pylori infection significantly upregulates IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α, highlighting the pivotal role of circRNAs in H. pylori-associated GC development. LncRNAs, another type of widely dysregulated ncRNAs in tumor tissues, are also altered in H. pylori-associated GC, including LINC00152, LNCH19, XLOC-004122, XLOC-014388, and others. The dysregulation of multiple lncRNAs indicates their potential as diagnostic biomarkers for GC. There are many technologies for biopsy ncRNA detection, including PCR-based detection techniques such as real-time PCR and digital PCR; next-generation sequencing-based techniques, including RNA sequencing, whole exome sequencing, and microfluidics; and other new techniques, including molecular beacon and CRISPR/Cas system assisted detection (Cas12a system)[37]. Based on our previous description, ncRNAs can be detected in blood, saliva, and urine, which is convenient and non-invasive (Figure 1). In addition to serving as biomarkers for early-stage GC, ncRNAs can also function as prognostic markers for GC. circ_0008315 is upregulated in GC, cisplatin-resistant GC cells, and cisplatin-resistant GC organoid model. High circ_0008315 expression is associated with poor OS in GC patients[38]. Wang et al[39] reported that an APAF1-binding lncRNA is upregulated in GC tissues and is associated with drug resistance, suggesting its potential as a prognostic marker for GC. Although multiple ncRNAs are upregulated in H. pylori-infected GC tissues, and many studies have identified ncRNAs with potential as early diagnostic biomarkers for GC, their clinical application still faces many challenges. First, some ncRNAs lack specificity[40]. For example, although miR-584 is upregulated in H. pylori-infected GC, it is also elevated in the serum of lung cancer patients and in hepatocellular cancer tissues[41,42]. Similarly, circFNDC3B is upregulated in oral squamous cell carcinoma, esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, and other tumor types[43,44]. Multi-marker panels effectively enhance the specificity of ncRNAs. For example, So et al[7] simultaneously tested 12 miRNAs alongside other biomarkers to diagnose early-stage GC, achieving a specificity of 69.4%. In the detection of lung adenocarcinoma, a seven-miRNA panel achieved an AUC of 0.85[45]. However, the use of multi-marker panels also raises concerns regarding the convenience and cost of detection. Second, the levels of many ncRNAs in serum have not been shown to be associated with early-stage GC. As a result, developing these ncRNAs as biomarkers may require invasive examinations, further limiting their general applicability. Third, the expression levels of ncRNAs in serum are relatively low, imposing higher demands on detection accuracy and sensitivity. With advancements in sequencing technologies, this problem is gradually being addressed. In addition, there is a lack of standardized sample processing protocols and analysis methods for ncRNA detection, which limits the development of ncRNA biomarkers for clinical applications.

Figure 1 The workflow for non-coding RNA-based liquid biopsy in clinical screening.

Non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) from blood, saliva, and urine have been reported as potential biomarkers for Helicobacter pylori-infected gastric cancer (GC). Clinically, blood, saliva, and urine can be collected from patients, followed by nucleic acid extraction in the lab. After that, PCR, next-generation sequencing, or other techniques can be used to detect GC-associated ncRNAs. This figure was created with BioGDP.com[46]. LncRNA: Long non-coding RNA; MiRNA: MicroRNA; CircRNA: Circular RNA; NGS: Next-generation sequencing.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Oncology

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report’s classification

Scientific Quality: Grade C

Novelty: Grade B

Creativity or Innovation: Grade C

Scientific Significance: Grade C

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P-Reviewer: Wei X, Professor, China S-Editor: Lin C L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Zhang L