INTRODUCTION

Indocyanine green fluorescence (ICG) is taken up by hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) but is not removed because of the downregulation of ligandin and other transporter proteins in neoplastic liver tissue[1]. This property has led to the wide use of ICG in the clinical management of HCC. Over the past ten years, numerous papers have been published on the use of ICG fluorescence in liver surgery for treating HCC. Recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses have shown that laparoscopic liver resection guided by ICG for treating HCC significantly increases the rate of tumor margin-negative (R0) resection, reduces intraoperative time and blood loss, and decreases the rate of intraoperative transfusions and postoperative complications[2]. For liver tumors formed by nonhepatocyte cells, such as epithelial cells found in colorectal liver metastases (CRLM), the rim-type fluorescence signal is due to the compressed hepatocytes surrounding the metastatic lesion that have decreased bile excretion ability. The European Association of Endoscopic Surgery strongly recommends the use of ICG fluorescence imaging in combination with intraoperative ultrasound to improve the detection of superficial liver metastases[3]. In a minimally invasive setting, ICG can also be used to assess surgical margins in real time by evaluating the integrity of the fluorescent rim around lesions during wedge resection[4]. Recent studies have shown that patients who underwent ICG-guided liver resection for CRLM had a higher rate of R0 resection than non-ICG patients[5,6]. Laparoscopic liver resection for CRLM using ICG improves not only R0 resection rates but also perioperative outcomes (shorter operative times and less blood loss) and reduces margin recurrence[7]. Conversely, there is little evidence regarding the use of ICG for other nonhepatocyte liver tumors, neuroendocrine tumors liver metastases (NETMs), uveal melanoma, breast cancer, or intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC). According to the literature, 21%-90% of patients affected by neuroendocrine tumors develop liver metastases, with 12%-74% of these patients presenting with metastases at the time of diagnosis[8]. Only liver resection with clear margins (R0) can improve the prognosis due to the large burden and high risk of recurrence; therefore, parenchymal-sparing liver resection is the right choice. The role of ICG in patients undergoing parenchyma-sparing liver resection for NETM remains unclear. Recently, Wang et al[9] reported a retrospective observational study investigating the use of ICG for detecting and assessing the margins of NETM. The authors compared two groups of patients: Those who underwent ICG-guided liver resection (31 patients) and those who underwent resection without ICG imaging (20 patients). They reported that ICG fluorescence imaging effectively ensured the safety of surgical margins, achieving R0 resection in 97% of cases compared with 75% in the group without ICG fluorescence guidance. However, although the recurrence-free survival (RFS) Kaplan-Meier curve of patients in the ICG group showed a better trend, the difference was not statistically significant[9]. Another application of ICG is the detection of liver metastases from uveal melanoma. This is due to the high risk of multiple small metastases that cannot be identified by preoperative imaging and can only be observed with ICG fluorescence[10]. Additionally, ICCs themselves do not take up ICG dye, and the surrounding hepatic surface is stained due to cholestasis caused by tumor compression or bile duct infiltration. According to these preliminary studies, most mass-forming (MF) ICCs exhibit negative or rim-fluorescence patterns, whereas the periductal infiltrating (PI) and mixed-type periductal infiltrating (MF-PI) ICCs exhibit segmental fluorescence[11,12]. During surgery, segmental fluorescence on the liver surface helps surgeons estimate the extent of liver resection. The presence of fluorescence may indicate compression or invasion of the bile ducts in this area. Therefore, resection should extend beyond the fluorescent regions to achieve R0 resection. In a retrospective pilot study evaluating the feasibility of ICG as a real-time navigation tool, the authors reported that the scheduled operation was changed intraoperatively for two patients due to fluorescence imaging[12]. ICG can also be used to identify superficial satellite nodules[11].

ICG FLUORESCENCE WAS USED TO IDENTIFY THE SEGMENTAL HEPATIC REGION

In hepatobiliary surgery, ICG can be adopted for precise delineation of hepatic segments during anatomical liver resection for HCC. The first application dates back to 2008, when Aoki et al[13] reported using ICG imaging to identify segmental hepatic regions and obtain greater precision during parenchymal transection. Two different techniques for visualizing segmental hepatic anatomy with ICG have been described. In positive visualization, ICG is directly injected into a segmental portal branch. In the negative staining technique, after the segmental portal pedicle is selectively clamped, ICG is injected intravenously[14-17].

Recent studies have also shown that complete resection of all ischemic liver tissue from healthy liver tissue is an independent predictor of long-term outcomes[18]. Moreover, during major hepatectomies, intrahepatic biliary anatomy can be evaluated using intraoperative fluorescent cholangiography with ICG to avoid severe complications such as biliary injury[19].

ICG FLUORESCENCE TO TARGET SUPERFICIAL LESIONS IN PATIENTS WITH MACRONODULAR CIRRHOSIS

In minimally invasive surgeries, such as laparoscopy or robotic surgeries, small superficial lesions may be missed due to the limited ability of ultrasound to visualize small lesions on an irregular liver surface and the presence of air between the probe and the Glissonian surface[20,21].

Therefore, identifying lesions that must be removed in patients with macronodular cirrhosis can be very challenging. ICG fluorescence fusion images can mimic the tactile feedback of the hand and improve ultrasound imaging, assisting in the identification of superficial nodules.

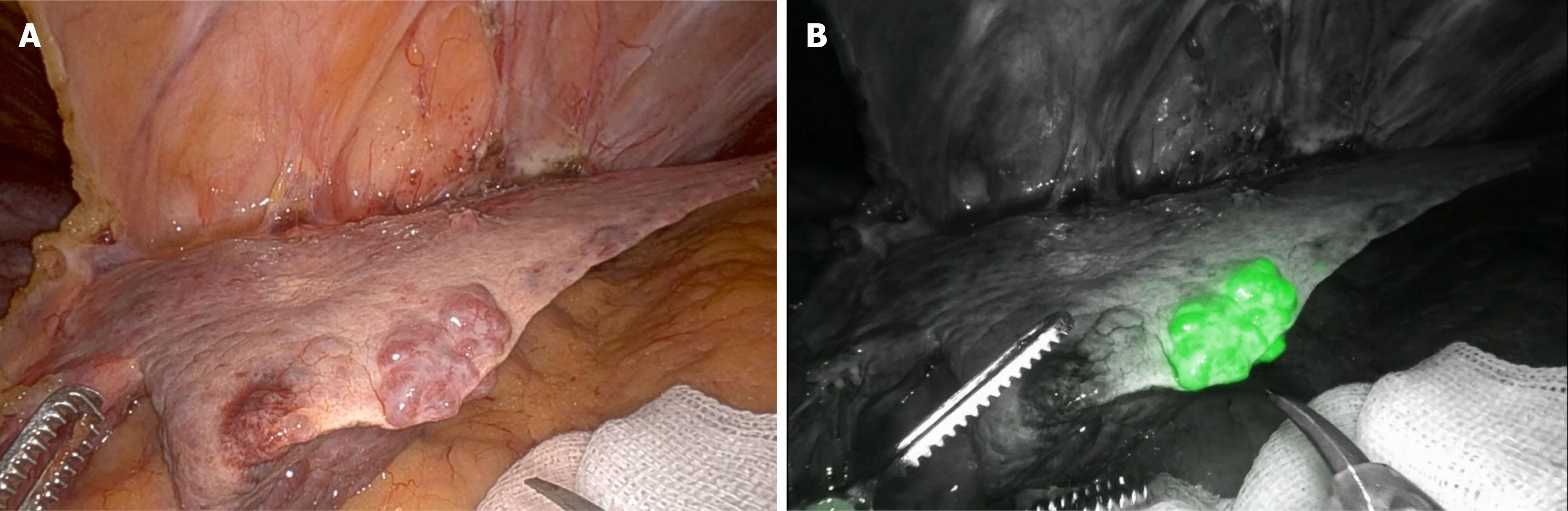

Kudo et al[22] first proposed the use of laparoscopic ICG fluorescence imaging for the real-time identification of subcapsular hepatic lesions. Seventeen patients were included in the pioneering study, including 10 with HCC. ICG fluorescence staining successfully revealed 12 out of 16 (75%) HCCs. All lesions identified by ICG were close to the liver surface and were not identified by laparoscopic inspection (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Hepatocellular carcinoma at the edge of the left lobe in patient with.

A: Laparoscopic view; B: Indocyanine green-window view.

In a prospective study including 22 patients affected by primary and metastatic liver tumors, Boogerd et al[23] reported that ICG/near-infrared (NIR) fluorescence imaging had the highest sensitivity (92.3%) among all preoperative [computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging scans of the abdomen] and intraoperative [visual inspection, laparoscopic ultrasound (LUS), and ICG/NIR fluorescence] imaging modalities.

Similar findings were reported by Piccolo et al[24] in a prospective study of 18 patients with primary and metastatic liver tumors. The authors compared preoperative imaging (CT and MRI scans of the abdomen) with LUS and ICG/NIR fluorescence imaging. Twenty-nine tumors (100%) were correctly identified using ICG/NIR fluorescence imaging, whereas 21 tumors (72.4%) were correctly identified using only LUS. The lesions that could not be identified using LUS were smaller (< 1 cm) and located in the posterolateral segments or at the edge of the liver in patients with macronodular alterations.

Based on the available data, we suggest that in minimally invasive surgery, where tactile feedback is absent, ICG fluorescence plays a critical role in the detection of superficial HCC in patients with macronodular cirrhosis.

ICG FLUORESCENCE GUIDANCE FOR LAPAROSCOPIC THERMAL ABLATION

Laparoscopic microwave ablation of HCC is typically performed under ultrasound guidance. However, the presence of macronodular cirrhosis and an irregular liver surface makes it difficult to detect superficial nodules due to inadequate contact between the probe and the liver surface. ICG fluorescence can overcome these difficulties. In some cases, ICG can also be used to evaluate tumor residues after thermal ablation. Fewer studies have evaluated these topics[25-27]. In a retrospective study[26], the authors compared patients who underwent laparoscopic microwave ablation with and without the aid of ICG fluorescence (29 vs 32 patients, respectively). Five additional lesions were found in the first group, which were detected only via ICG fluorescence and not identified by preoperative imaging. There was no difference in overall survival between the two groups of patients, but the authors reported significantly lower RFS among patients treated with the integration of the two techniques (LUS + ICG).

Similar data were presented by Hu et al[27], who evaluated 40 liver lesions in 27 patients who underwent fluorescence-assisted laparoscopic thermal ablation (radiofrequency and microwave) in a prospective study. The detection rate of HCCs through ICG fluorescence was 82.5% (33 out of 40 lesions). ICG fluorescence staining revealed 4 additional lesions that had not been identified preoperatively and could not be seen on intraoperative ultrasound. Technical success was defined as the achievement of a necrotic zone with at least a 5-mm ablative margin around the outer edge of the ICG fluorescence image. Complete necrosis of the lesion was achieved in 92.5% (37/40) of the patients, and local tumor progression occurred in 7.5% (3/40) of patients.

In conclusion, we believe that ICG fluorescence guidance for laparoscopic thermal ablation is feasible and useful; however, the available data requires further studies involving larger numbers of patients.

ICG FLUORESCENCE PATTERNS AND TUMOR CHARACTERISTICS

Hepatocytes take up ICG dye via two specific transmembrane transport systems: Organic anion-transporting polypeptides and sodium taurocholate-cotransporting polypeptides. These proteins are present at higher levels in cancerous hepatocytes than in normal liver tissue. Therefore, HCC typically exhibit homogeneous or partial fluorescence. Rim-type fluorescence occurs in only a few cases and is due to decreased levels of these specific portal uptake transporters. However, there are many different ICG pattern classifications, and few studies have correlated fluorescence patterns with the pathological features of HCCs[28-33].

Ishizawa et al[29] first identified three patterns of ICG fluorescence in HCCs: Total, partial, and rim fluorescence. The authors reported that, compared to patients with rim-type ICG fluorescence, patients with total or partial ICG fluorescence had better cancer cell differentiation, a smaller tumor diameter, and a lower incidence of microvascular invasion. Similar data were recently shown in a Western prospective cohort study[30].

Piccolo et al[30] evaluated the correlation between ICG patterns and HCC differentiation grade. They divided the lesions into two groups: Total fluorescence (where all tumoral tissue showed strong, homogeneous fluorescence; n = 9/33; 27.3%) and nontotal fluorescence (where there was partial or rim fluorescence; n = 24/33; 72.7%).

They reported a statistical correlation between ICG patterns and differentiation grade. Almost all lesions with a uniform fluorescence pattern were well-differentiated HCCs (G1-G2), whereas a partial or rim fluorescence pattern was more prevalent among moderately and poorly differentiated HCCs (G3-G4) (88.9% vs 11.1%; 37.5% vs 62.5%; P = 0.025).

In contrast, Kaibori et al[31] classified resected specimens into two groups: The high-cancerous (HC) group, where high ICG fluorescence was present in the neoplastic area, and the high-surrounding (HS) group, where high ICG fluorescence was present in the surrounding liver tissue.

The authors reported that patients in the HC group had a significantly higher incidence of cirrhosis; a higher 15-minute clearance retention rate (R15) as measured using the LiMON® test; and lower levels of total bilirubin, aspartate transaminase, alanine transaminase, and platelets than patients in the HS group.

Poorly differentiated HCCs were more common in the rim-type subgroup. Tashiro et al[32] reported a similar classification, dividing HCCs into two groups based on ICG fluorescence: Rim-negative and rim-positive. The rim-negative group was further divided into two subtypes: Total and partial fluorescence. The authors reported that cirrhosis was significantly more prevalent among patients in the rim-positive group. Furthermore, well-differentiated HCCs were more prevalent among the total fluorescence types than in the other subgroups.

Recently, hepatobiliary surgeons from Paul-Brousse Hospital proposed a more complex classification, in which they evaluated the fluorescence of both the tumor and the surrounding liver tissue separately[33]. HCCs with intralesional ICG fluorescence were categorized into three groups: (1) Uniform emission; (2) Heterogeneous emission; and (3) No emission. Each of these subtypes was also classified into two subgroups according to the presence or absence of rim-like ICG fluorescence in the peritumoral liver tissue.

Patients with HCCs that showed homogeneous fluorescence within the lesion had a lower necrosis rate and higher serum alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) levels. Conversely, rim emission was associated with peritumoral vascular changes, lower differentiation, and lower serum AFP levels.

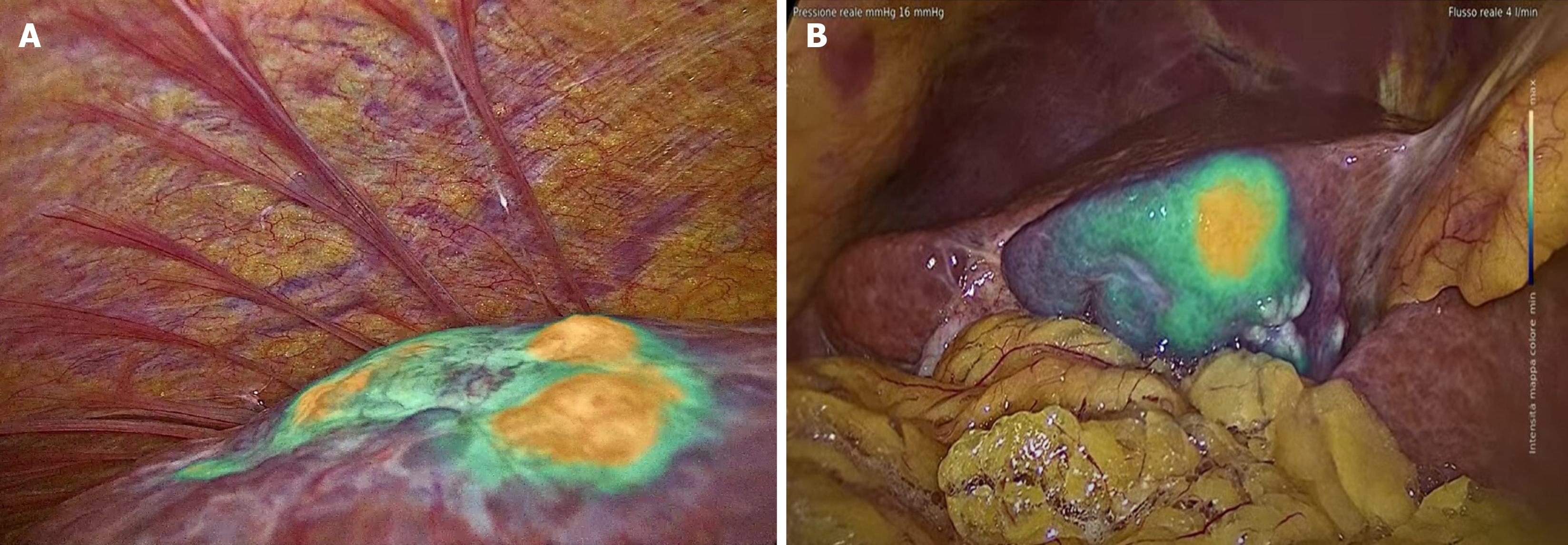

Of particular interest is the correlation between ICG fluorescence patterns and microinvasive components, such as vascular microinfiltration of the portal or hepatic veins, infiltration of the bile ducts, and the presence of satellite nodules. In our experience, HCCs with vascular microinfiltration exhibit more nodules with intense ICG fluorescence during surgery (Figure 2; intensity maps of IMAGE1 S™ Rubina®, Karl Storz Endoscope). We also report a rare case of HCC with microinvasive components due to periductal infiltration. This presented as a homogeneous and intensely fluorescent area of neoplastic tissue around the peritumoral area (Figure 3; intensity maps of IMAGE1 S™ Rubina®, Karl Storz Endoscope).

Figure 2 Indocyanine green fluorescence patterns and microinvasive components.

A: Hepatocellular carcinoma with vascular micro-invasion, indocyanine green (ICG)-window view showed more nodules with intense ICG fluoresce; B: Hepatocellular carcinoma with microinvasive components due to periductal infiltrating growth, which showed a homogeneous and intense area of neoplastic tissue with partial fluorescence around the peritumoral area (intensity maps of IMAGE1 S™ Rubina®, Karl Storz Endoscope).

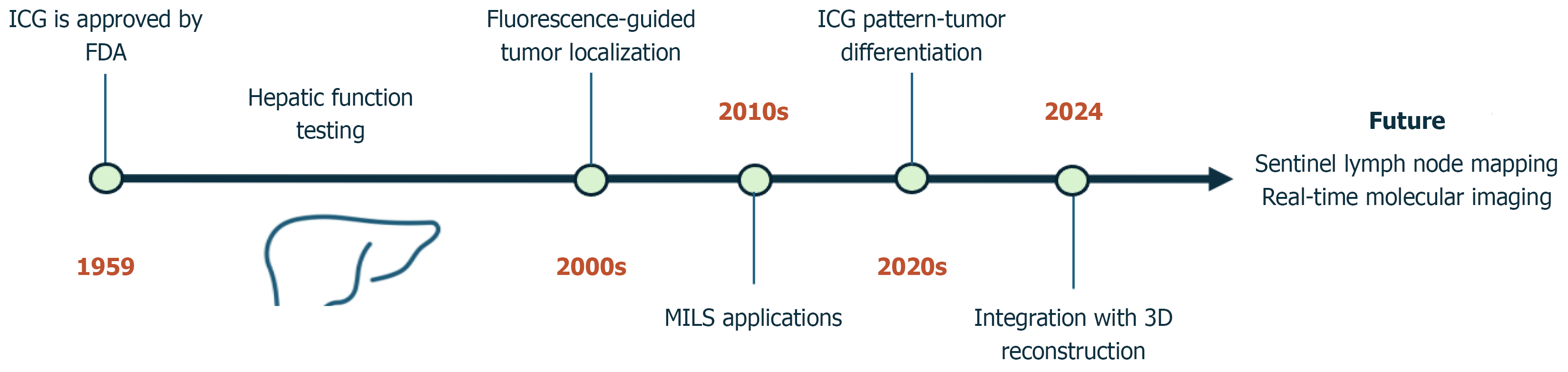

Figure 3 Indocyanine green evolution timeline.

ICG: Indocyanine green; MILS: Minimally invasive liver surgery; FDA: Food and Drug Administration.

CONCLUTION

ICG technology is currently widely used in hepatobiliary surgery for staining liver segments during anatomical liver resection, detecting liver tumors, and identifying tumor characteristics and fluorescence patterns.

Although some limitations should be considered, ICG fluorescence helps surgeons identify curved intersegmental planes during laparoscopic anatomical segmentectomy; however, the dye is also absorbed by the liver, reducing its effectiveness over time. Recently, some authors have proposed the use of trans-arterial-positive ICG staining as a solution. The day before or on the day of surgery, patients undergo selective artery embolization using an ICG-Lipiodol® mixture and a gelatin sponge to identify the hepatic subsegment[34,35].

When ICG fluorescence is used to detect liver nodules, technical drawbacks include tissue penetration depth (up to 8 mm from the liver surface) and the timing of ICG injection before surgery. Biliary excretion of the ICG dye is usually impaired in patients with liver cirrhosis. Although the correct timing has yet to be standardized, ICG is currently injected between 7 and 14 days before scheduled liver resection.

Another factor to consider is that this technique produces a high percentage of false positives. ICG fluorescence can occur in benign nodules, such as adenomas, regenerative nodules, biliary hamartomas, and focal nodular hyperplasia[36,37].

A new area of research in the use of ICG in HCC involves investigating the lymphatic drainage of liver tumors (Figure 3)[38-40].

Ruzzenente et al[40] proposed the use of ICG fluorescence to identify lymphatic outflow pathways and sentinel lymph nodes (SLNs) during surgery for liver and biliary cancers. The study protocol involved the peritumoral administration of 1 mL of a solution obtained by diluting 25 mg of ICG in 20 mL of water for injection. After the injection, a specific infrared camera (Stryker™) was used to detect fluorescence. Visualization of the lymphatic outflow pathway was obtained for 77.8% (n = 14) of the patients. Specifically, the hepato-celiac (left route) was visualized in 10 patients, the hepato-cholecystic-retropancreatic (right route) in 3 patients, and the diaphragmatic route in 2 patients. The median time for visualization was 3 minutes after ICG injection. The SLN was detected in 13 patients (77.2%), with a median visualization time of 5 minutes. The SLN was localized along the common hepatic artery (Station 8) in 6 patients, in the hepatoduodenal ligament (Station 12) in 5 patients, and at the posterior aspect of the pancreatic head (Station 13) in 2 patients. Histological examination of the SLN confirmed the presence of lymphatic tissue in 92.3% of the patients (n = 12) and neoplastic cells in 25% of the patients (metastatic SLN, n = 3). Despite these promising initial results, we believe that further studies are needed to confirm them.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Oncology

Country of origin: Italy

Peer-review report’s classification

Scientific Quality: Grade C, Grade C, Grade C

Novelty: Grade C, Grade C, Grade C

Creativity or Innovation: Grade C, Grade C, Grade C

Scientific Significance: Grade C, Grade C, Grade C

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P-Reviewer: Sun GY, PhD, Associate Research Scientist, China; Tan BB, PhD, Chief Physician, Professor, China S-Editor: Qu XL L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zhang L