Published online Jan 15, 2026. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v18.i1.113662

Revised: September 29, 2025

Accepted: November 14, 2025

Published online: January 15, 2026

Processing time: 134 Days and 18.2 Hours

Early screening, preoperative staging, and diagnosis of lymph node metastasis are crucial for improving the prognosis of gastric cancer (GC).

To evaluate the diagnostic value of combined multidetector computed tomogra

In this retrospective study clinical and imaging data of 134 patients with sus

The combined use of MDCT and gastrointestinal endoscopy demonstrated a sensitivity of 98.53%, specificity of 97.06%, accuracy of 98.04%, positive predictive value of 98.53%, and negative predictive value of 97.06% for diagnosing GC. These factors were all significantly higher than those of MDCT or endoscopy alone (P < 0.05). The accuracy rates of the combined approach for detecting clinical T and N stages were 97.06% and 92.65%, respec

The combined application of MDCT and gastrointestinal endoscopy enhanced diagnostic accuracy for GC, pro

Core Tip: Combining multidetector computed tomography and gastrointestinal endoscopy significantly improved diagnostic performance for gastric cancer screening, preoperative T and N staging, and lymph node metastasis detection compared with either modality alone. The combined approach demonstrated superior sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy, offering greater concordance with postoperative pathological findings. This integrative strategy supports more informed clinical decision-making and optimized preoperative planning.

- Citation: Ye LP, Zhang YP, Chen G, Wu YX, He CL, Wang D, Mei Q. Combined multidetector computed tomography and gastrointestinal endoscopy for gastric cancer screening, preoperative staging, and lymph node metastasis detection. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2026; 18(1): 113662

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v18/i1/113662.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v18.i1.113662

Gastric cancer (GC) is one of the most common malignant tumors, ranking fifth in global incidence and fourth in cancer-related mortality. In China GC has the third highest incidence and mortality rate among all cancer types, accounting for approximately 44.0% of new GC cases and 48.6% of GC–related deaths worldwide[1]. The high mortality rate is largely attributable to the low rate of early screening, which often results in missed opportunities for timely diagnosis. The prognosis of GC is strongly associated with clinical stage with early GC demonstrating favorable outcomes and a 5-year survival rate exceeding 90%[2]. Therefore, early screening is particularly important. In addition, preoperative staging and accurate assessment of lymph node metastasis are essential for developing optimal treatment strategies for patients with GC.

At present the main preoperative diagnostic methods for GC include upper gastrointestinal barium meal examination, gastrointestinal endoscopy, and multidetector computed tomography (MDCT). Barium meal fluoroscopy can reveal the contour and filling defects of lesions, but its diagnostic value is limited for early GC with inconspicuous mucosal changes[3]. Gastrointestinal endoscopy allows direct visualization of the morphology and extent of the lesion; however, its ability to assess the depth of tumor invasion and lymph node metastasis is limited, particularly in early GC with subtle mucosal changes[4]. MDCT can clearly display gastric wall thickness, enhancement patterns, and relationships with surrounding tissues, and it is the most commonly used method for preoperative staging of GC. Nevertheless, its diagnostic accuracy for early GC is reduced due to the absence of marked gastric wall thickening[5]. In addition, MDCT has certain limita

To improve diagnostic accuracy this study evaluated the combined application of MDCT and gastrointestinal endo

A consecutive series of patients presenting with gastrointestinal symptoms and clinically suspected of GC at our insti

Inclusion criteria: (1) Age between 18 and 80 years; (2) Presence of upper gastrointestinal symptoms (e.g., epigastric pain, dyspepsia, weight loss, hematemesis, or melena) warranting investigation for GC; (3) Scheduled to undergo both stan

Exclusion criteria: (1) Previous history of any antitumor therapy (e.g., chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or targeted therapy) prior to the diagnostic work-up; (2) A definitive histological diagnosis of GC established prior to the current presentation; (3) History of major abdominal or gastric surgery that could significantly alter gastric anatomy or imaging interpretation; (4) Diagnosis of any concurrent or previous other malignant tumors; (5) Known history of extragastric lymphoma or suspicion of gastric involvement by lymphoma; (6) Incomplete pathological data or loss to follow-up before surgery; and (7) Contraindications to either MDCT (e.g., severe contrast allergy, renal insufficiency) or gastrointestinal endoscopy (e.g., high risk of perforation, severe cardiopulmonary comorbidities).

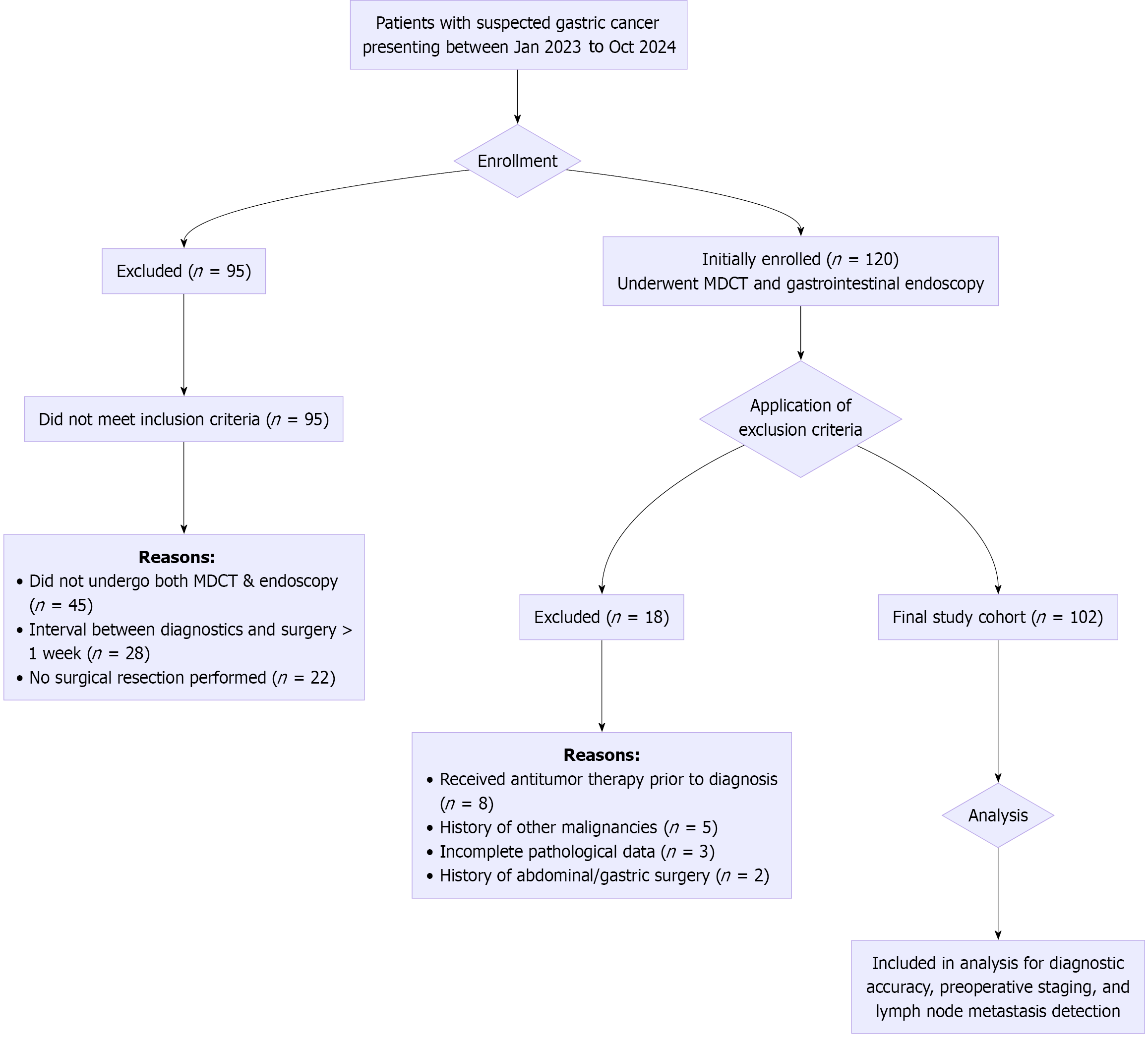

Patient enrollment and selection: The patient selection process is summarized in Figure 1. During the study period a total of 215 patients were initially assessed for eligibility. Among them, 95 were excluded for not meeting the inclusion criteria, primarily due to the absence of both MDCT and endoscopy exams, prolonged intervals between diagnostics and surgery, or lack of surgical intervention. Subsequently, 120 patients who preliminarily met the criteria and provided informed consent were enrolled for further evaluation. After applying the exclusion criteria, 18 patients were excluded: 8 due to receipt of neoadjuvant therapy prior to definitive diagnosis; 5 due to a history of other malignancies; 3 due to incomplete pathological data; and 2 due to a history of major abdominal surgery. Consequently, 102 patients were finally included in the analysis cohort (Figure 1).

A German Siemens SOMATOM Sensation 64-slice MDCT scanner was used. All patients fasted and abstained from drinking water for at least 12 h before scanning. To reduce gastrointestinal peristalsis, 20 mg of scopolamine (Chengdu First Pharmaceutical, National Drug Approval No. H51021969) was administered intramuscularly 10 min prior to the examination. For gastric distension each patient orally ingested 600-800 mL of warm water approximately 30 min before image acquisition.

The scanning range extended from the diaphragm to the lower pole of the kidneys. The acquisition parameters were as follows: Tube voltage, 120 kV; tube current, 220 mA; slice collimation, 64 mm × 0.6 mm; rotation time, 0.5 s; and pitch, 1.2. Although the primary dataset for initial clinical reporting had a slice thickness of 5 mm, thin-section axial images with a reconstruction thickness of 0.75 mm and an increment of 0.5 mm were routinely generated for all patients. Multiplanar reconstructions (MPR) in the coronal and sagittal planes were also performed on the workstation to facilitate detailed assessment of the gastric wall and perigastric structures.

After unenhanced scanning contrast-enhanced scanning was performed using a power injector. Iodixanol injection (Shanghai Bracco Xinyi Co., Ltd., National Drug Approval No. H20073014) was administered via the antecubital vein at a dose of 1.5 mL/kg body weight and an injection rate of 2.5-3.0 mL/s. Triphasic scanning was performed using a bolus-tracking technique. The arterial phase (30-35 s delay), portal venous phase (60-70 s delay), and equilibrium phase (120-180 s delay) were acquired. The arterial phase was optimized for assessing vascular involvement and hyperenhancing tumors while the portal venous phase was primarily used for tumor staging and lymph node assessment.

All patients underwent a comprehensive endoscopic evaluation. The procedure began with standard white-light endoscopy (WLE) using a high-definition endoscope (Fujifilm EG-580UR) to visually inspect the location, size, morpho

This was immediately followed by EUS using the same endoscope, which was an electronic ultrasound endoscope capable of both functions. Therefore, all 102 patients in the final cohort underwent both standard WLE and EUS exami

Prior to EUS gastric air was aspirated, and degassed water was injected to submerge the lesion site, creating an acoustic window. The ultrasound probe was used to scan the gastric wall, which was visualized as a five-layer structure. The depth of tumor invasion was assessed based on the disruption, thickening, or irregularity of these layers. Sector scanning was then performed to evaluate perigastric and regional lymph nodes (e.g., perigastric, celiac, hepatoduodenal) and adjacent organs (e.g., pancreas, liver) for metastasis.

EUS: The staging criteria were: (1) T1a. Tumor invades the first and second mucosal layers, characterized by thickening, irregularity, or discontinuity; (2) T1b. Tumor invades the third submucosal layer with defects, discontinuity, thickening, and blurred structural boundaries; (3) T2. Tumor invades the muscularis propria, showing wall thickening, central depression, blurring of layers 1-3, and heterogeneous echoes; (4) T3. Tumor invades the serosal layer without affecting the visceral peritoneum or adjacent structures with structural defects of the gastric wall and blurred layered echoes; and (5) T4. Tumor invades the serosal layer and involves surrounding organs with evidence of adjacent organ infiltration and low-echo lesions extending into the fifth high-echo layer[6].

Metastatic lymph nodes: Defined by EUS as having clear borders, low echogenicity, round shape, and a diameter ≥ 10 mm.

Non-metastatic lymph nodes: Defined as hyperechoic with unclear borders, oval shape, and diameter < 10 mm. N stage assessment was: N0. No regional lymph node metastasis; N1. One to two metastatic lymph nodes; N2. Three to six re

Multislice MDCT: T staging by MDCT was: T1. Thickening of the gastric wall along the lesser curvature with a clear fat layer, mucosal thickening with abnormal enhancement, and tumor confined to the gastric wall; T2. Same as T1 with additional tumor invasion into the muscular layer; T3. Marked gastric wall thickening with tumor involvement of the serosal layer, showing clear boundaries with surrounding organs; and T4. Pronounced thickening of the gastric antrum wall with tumor extension into surrounding tissues[7].

N stage assessment: The evaluation was based on lymph node metastasis with a short-axis diameter of abdominal wall lymph nodes ≥ 6 mm and gastric wall lymph nodes ≥ 8 mm. N staging was consistent with the classification determined by EUS.

Postoperative pathological staging criteria: The following criteria were used for T staging: T0. Tumor confined to the mucosal layer; T1. Invasion of the submucosa; T2. Invasion of the muscularis propria; T3. Invasion of the subserosal connective tissue; T4a. Tumor invasion of the serosa; and T4b. Tumor invasion of surrounding organs. The following criteria were used for N staging: N0. No lymph node metastasis; N1. One to two regional lymph node metastases; N2. Three to six lymph node metastases; and N3. Seven or more lymph node metastases.

Our first aim was to compare the diagnostic value of MDCT combined with gastrointestinal endoscopy for GC, including sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value. Our second aim was to evaluate the diagnostic consistency of the combined method in preoperative clinical staging of GC (T and N stage). Our final aim was to assess the detection rate of lymph node metastasis in GC using the combined method.

MDCT interpretation: All MDCT images, including thin-section axial and MPRs, were independently reviewed by two abdominal radiologists (with 10 and 8 years of experience in gastrointestinal imaging, respectively) who were blinded to the endoscopic findings, pathological results, and the final clinical diagnosis. Each radiologist recorded their assessment of the T stage, N stage, and the presence of lymph node metastasis. In cases of disagreement a final consensus reading was held to determine the MDCT diagnosis for study purposes.

EUS interpretation: Similarly, the EUS images and videos were independently reviewed by two endoscopists (with 9 and 7 years of experience in EUS, respectively) who were blinded to the MDCT results and final pathological staging. They independently assessed the T stage, N stage, and lymph node status. A consensus reading was also performed to resolve any discrepancies.

Pathological analysis: All surgical specimens were fixed, paraffin-embedded, sectioned, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Immunohistochemical analysis was performed when necessary. Two pathologists, who were blinded to the MDCT and EUS findings, independently reviewed all slides. The pathological T and N stages, determined according to the AJCC 8th edition criteria, served as the gold standard.

Interobserver agreement for T and N staging between the two readers for both MDCT and EUS was calculated using Cohen’s kappa (κ) or weighted kappa statistics. The strength of agreement was interpreted as follows: < 0.20, poor; 0.21-0.40, fair; 0.41-0.60, moderate; 0.61-0.80, substantial; and 0.81-1.00, almost perfect.

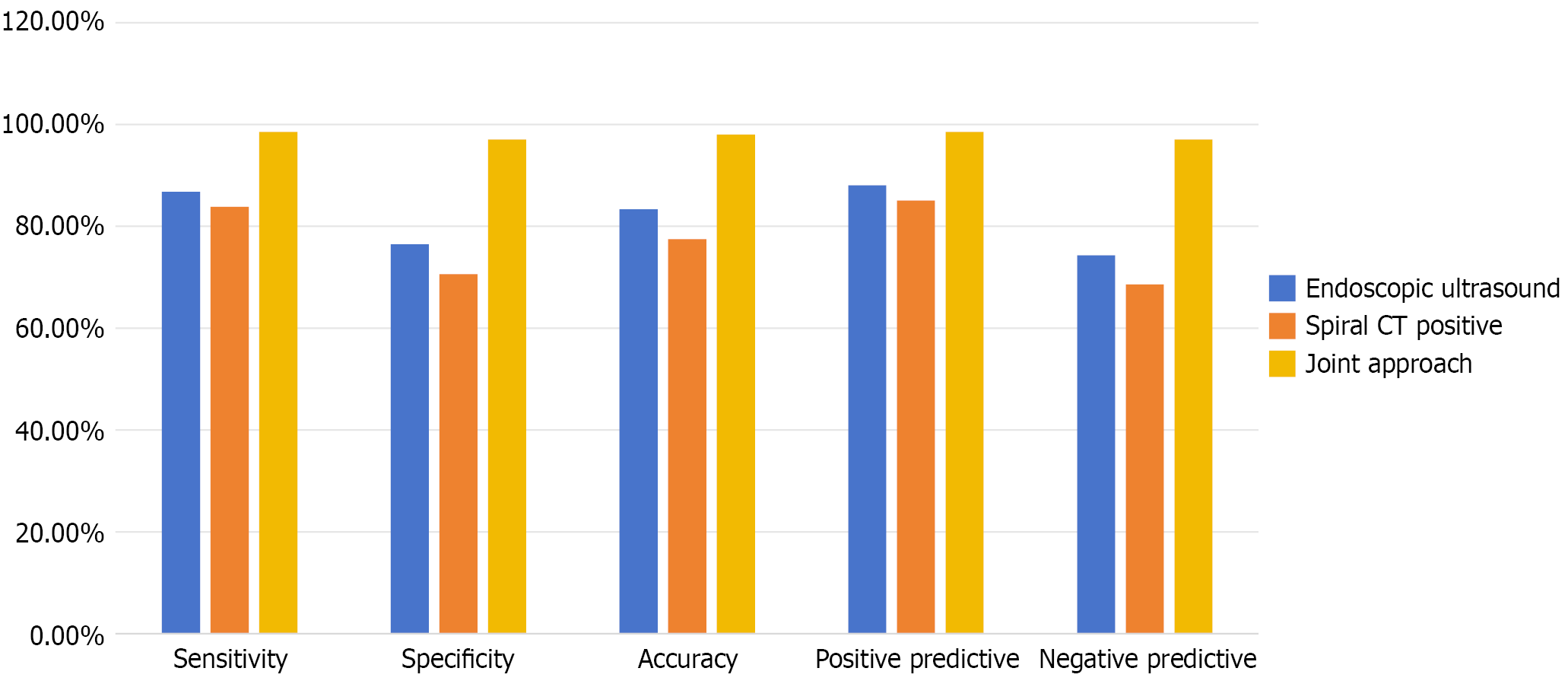

Among the 102 patients suspected of having GC, 68 cases (66.67%) were confirmed by surgical pathology. The diagnostic accuracy of the combined application of MDCT and gastrointestinal endoscopy was significantly higher than that of either modality alone (P < 0.05) (Table 1 and Figure 2).

| Methods | Pathological examination | Total | Sensitivity, % | Specificity, % | Accuracy, % | Positive predictive value, % | Negative predictive value, % | |

| Positive | Negative | |||||||

| Endoscopic ultrasound positive | 59 | 8 | 67 | 86.76 (59/68) | 76.47 (26/34) | 83.33 (85/102) | 88.06 (59/67) | 74.29 (26/35) |

| Negative | 9 | 26 | 35 | |||||

| Total | 68 | 34 | 102 | |||||

| MDCT positive | 57 | 10 | 67 | 83.82 (57/68) | 70.59 (24/34) | 77.45 (79/102) | 85.07 (57/67) | 68.57 (24/35) |

| Negative | 11 | 24 | 35 | |||||

| Total | 68 | 34 | 102 | |||||

| Joint approach positive | 67 | 1 | 68 | 98.53 (67/68) | 97.06 (33/34) | 98.04 (100/102) | 98.53 (67/68) | 97.06 (33/34) |

| Negative | 1 | 33 | 34 | |||||

| Total | 68 | 34 | 102 | |||||

| χ2 | 8.918 | 8.667 | 19.373 | 7.925 | 9.683 | |||

| P value | 0.012 | 0.013 | 0.001 | 0.019 | 0.008 | |||

The combination of MDCT and gastrointestinal endoscopy demonstrated high diagnostic concordance for clinical T and N staging of GC (κ = 0.864, P < 0.05) as shown in Tables 2 and 3. The overall accuracy for N staging (i.e. correct assignment to N0-N3 categories) was 92.65% with the combined approach (Tables 2 and 3).

| Pathology | Cases | Gastrointestinal endoscopy | Accuracy, % | MDCT | Accuracy, % | MDCT + gastrointestinal endoscopy | Accuracy, % | |||||||||

| T1 | T2 | T3 | T4 | T1 | T2 | T3 | T4 | T1 | T2 | T3 | T4 | |||||

| T1 | 12 | 10 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 83.33 | 11 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 91.67 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100.00 |

| T2 | 18 | 1 | 16 | 1 | 0 | 88.88 | 2 | 15 | 1 | 0 | 83.33 | 1 | 17 | 0 | 0 | 94.44 |

| T3 | 26 | 0 | 3 | 22 | 1 | 84.62 | 0 | 2 | 23 | 1 | 88.46 | 0 | 1 | 25 | 0 | 96.15 |

| T4 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 10 | 83.33 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 10 | 83.33 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 100.00 |

| Total | 68 | 11 | 21 | 25 | 11 | 85.29 | 13 | 18 | 26 | 11 | 86.76 | 13 | 18 | 25 | 11 | 97.06 |

| Pathology | Cases | Gastrointestinal endoscopy | Accuracy, % | 95%CI | MDCT | Accuracy, % | 95%CI | MDCT + gastrointestinal endoscopy | Accuracy, % | 95%CI | |||||||||

| N0 | N1 | N2 | N3 | N0 | N1 | N2 | N3 | N0 | N1 | N2 | N3 | ||||||||

| N0 | 18 | 15 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 83.33 | (58.58-96.42) | 16 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 88.89 | (65.29-98.62) | 17 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 94.44 | (72.71-99.86) |

| N1 | 19 | 4 | 13 | 2 | 0 | 68.42 | (43.45-87.42) | 3 | 16 | 0 | 0 | 84.21 | (60.42-96.62) | 1 | 17 | 1 | 0 | 89.47 | (66.86-98.70) |

| N2 | 21 | 0 | 4 | 17 | 0 | 80.95 | (58.09-94.55) | 0 | 4 | 17 | 0 | 80.95 | (58.09-94.55) | 0 | 1 | 20 | 0 | 95.24 | (76.18-99.88) |

| N3 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 3 | 30.00 | (6.67-65.25) | 0 | 0 | 5 | 5 | 50.00 | (18.71-81.29) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 9 | 90.00 | (55.50-99.75) |

| Total | 68 | 19 | 20 | 26 | 3 | 70.59 | (58.32-81.00) | 19 | 21 | 22 | 5 | 79.41 | (67.94-88.26) | 18 | 19 | 22 | 9 | 92.65 | (83.68-97.57) |

Fifty patients (73.53%) of the 68 patients with pathologically confirmed GC were found to have lymph node metastasis. The detection accuracy for lymph node metastasis was 66.00% (33/50) with gastrointestinal endoscopy, 76.00% (38/50) with MDCT, and 92.00% (46/50) with the combined approach. The differences were statistically significant (χ2 = 10.023, P = 0.001).

A male patient was admitted with “poor appetite and belching for over 1 month”. WLE revealed a large ulcer on the lesser curvature of the gastric body with a cauliflower-like appearance, friable texture, and a tendency to bleed easily (Figure 3A). Plain and contrast-enhanced abdominal CT demonstrated marked thickening of the gastric wall on the lesser curvature side with progressive moderate enhancement. The serosal surface of the lesion remained smooth, whereas multiple enlarged lymph nodes, some fused, were observed in the surrounding adipose tissue (Figure 3B and C). EUS revealed an irregular surface structure at the lesion site with heterogeneous echogenicity, disruption of the five-layer gastric wall structure, and poorly defined lesion margins (Figure 3D and E).

The incidence and mortality rates of GC remain high, and its development is associated with multiple factors, including Helicobacter pylori infection, diet, environmental exposures, and genetic predisposition[8]. The prognosis of patients with GC is closely related to tumor stage, lymph node metastasis, and tissue differentiation. Therefore, early screening, accurate preoperative staging, and reliable assessment of lymph node metastasis are crucial for effective treatment planning and improved prognosis.

MDCT is widely used in clinical practice, offering high spatial resolution and clear imaging. It can accurately depict tumor location and extent and detect omental and peritoneal metastases as well as distant spread[9]. However, in the early stages of GC, tumor invasion may not be apparent and can lead to relatively high rates of missed or incorrect diagnoses.

Gastrointestinal endoscopy is an effective diagnostic method, allowing direct visualization of lesion location, size, morphology, and extent. However, conventional endoscopy cannot reliably assess the depth of tumor invasion or lymph node involvement, limiting its accuracy for clinical staging[10]. In this context, EUS can be employed to directly visualize the five-layer structure of the gastric wall and delineate mucosal morphology, thereby providing valuable information for diagnosis and staging[11]. Nevertheless, because of its limited field of view, EUS is less effective when tumors extend into the submucosa or muscularis propria, restricting its diagnostic utility.

To address these limitations this study employed a combined diagnostic approach using MDCT and gastrointestinal endoscopy, aiming to integrate the strengths of both modalities and compensate for their individual shortcomings, thereby enhancing diagnostic accuracy. The results of this study showed that the combined application of MDCT and gastrointestinal endoscopy achieved a diagnostic sensitivity of 98.53%, specificity of 97.06%, accuracy of 98.04%, PPV of 98.53%, and negative predictive value of 97.06%. These indices were significantly higher than those of either MDCT or endoscopy alone (P < 0.05), indicating that the combined approach substantially improved GC detection and demon

This improved diagnostic performance can be attributed to several factors. MDCT enables comprehensive scanning of the entire stomach in a single breath-hold, and its capability for MPR provides multi-angled gastric imaging that is not influenced by respiratory motion, body fat, or gastric air, thereby assisting radiologists in accurately interpreting gastric anatomy. In addition, MDCT can clearly depict tumor morphology, extent, and precise location as well as its relationship with surrounding structures, thereby improving detection rates[12].

When combined with gastrointestinal endoscopy, which allows direct visualization of mucosal structures and morphology, the layered structure of the gastric wall and adjacent tissues can be clearly demonstrated. This facilitates assessment of the depth and extent of tumor invasion, providing critical information for diagnosis[13]. The combined use of MDCT and gastrointestinal endoscopy enables comprehensive, multidimensional evaluation of gastric structure and pathology, broadening the scanning scope with CT while allowing direct mucosal observation via endoscopy. This integrative approach enhances GC detection and offers greater clinical diagnostic value.

In the clinical management of GC, therapeutic strategies are selected according to tumor stage. Factors such as tumor invasion depth, lymph node metastasis, and involvement of adjacent organs play a decisive role in treatment planning. Patients with early-stage GC may undergo endoscopic mucosal resection or endoscopic submucosal dissection, whereas those in stage T1 may benefit from laparoscopic surgery. For advanced GC neoadjuvant chemotherapy or chemoradiotherapy prior to surgery can improve outcomes[14]. Therefore, early diagnosis and accurate preoperative staging, particularly the identification of lymph node metastasis, are critical for improving survival and avoiding both overtreatment and undertreatment.

This study showed that the diagnostic accuracy of combined MDCT and gastrointestinal endoscopy for clinical T staging of GC was 97.06%, significantly higher than that of MDCT alone (86.76%) or gastrointestinal endoscopy alone (85.29%) with statistically significant differences (P < 0.05). Compared with the recent single-center cohort study by Kim et al[15] (EUS T staging accuracy: 66.4%) and the CT-EUS tandem study by Lee et al[16] (EUS T staging PPV: 85.6%), this combined approach improved T staging accuracy by 11.5%-13.8% and N staging accuracy by 12.2%-21.3%. These findings suggest that optimizing scanning parameters and applying EUS hydrotubation techniques may further enhance the synergistic effects of combined modalities in regional populations.

These findings, together with results from other studies, suggest that combining MDCT with gastrointestinal endo

Gastrointestinal endoscopy on the other hand allows direct observation of lesion contours and mucosal changes, providing valuable information for assessing tumor invasion depth and T staging. Nevertheless, necrotic or fibrotic tissue on the mucosal surface may attenuate ultrasound echo signals or obscure thickened gastric walls and protruding lesions, thereby lowering the resolution for T staging. In addition, when tumors are accompanied by inflammatory reactions or fibrosis, the resulting blurring of the boundary between the muscularis propria and submucosa may lead to over staging[18]. Therefore, the combined use of MDCT and gastrointestinal endoscopy with each method complementing the other can significantly improve the overall accuracy of T staging in GC.

Lymph nodes are the primary pathway of metastasis in GC. Complete dissection of perigastric lymph nodes improves survival and prognosis. Research indicates that the accuracy of detecting lymph node metastasis with combined gas

However, as the number of lymph nodes increases, metastatic nodes may fuse with normal nodes, thereby increasing the diagnostic challenge. Gastrointestinal endoscopy has a limited scanning range and low sensitivity for detecting distant lymph node metastasis. Furthermore, normal fibrous tissue, local inflammation, and indistinct margins can interfere with endoscopic assessment. MDCT on the other hand lacks histopathological specificity, making it difficult to differentiate inflammatory lymphadenopathy from metastatic involvement. Therefore, the combined use of MDCT and gastrointestinal endoscopy enables detailed observation of subtle changes in lesion morphology and facilitates the detection of distant metastatic lymph nodes, ultimately improving the accuracy of lymph node metastasis detection.

In this study we employed modality-specific size criteria for defining metastatic lymph nodes: A short-axis diameter of ≥ 6 mm for abdominal nodes and ≥ 8 mm for gastric wall nodes on MDCT vs a diameter of ≥ 10 mm on EUS. This discrepancy warrants further discussion as it represents a potential source of bias when comparing the diagnostic performance of the two techniques.

The rationale for these differing thresholds is rooted in the inherent technical and physical principles of each modality. MDCT relies on morphological characteristics, and prior literature suggests that using a lower size threshold (e.g., 6-8 mm) helps to increase sensitivity for detecting metastatic deposits albeit at the potential cost of specificity as benign reactive hyperplasia can also cause lymph node enlargement [Citation, e.g., a relevant CT staging paper]. EUS with its superior spatial resolution allows for the detailed assessment of nodal architecture, echogenicity, and borders. Conse

This methodological difference could inherently bias the comparative performance in favor of the combined approach. The lower size threshold of MDCT might lead to overestimation (false positives) in reactive nodes while higher, feature-dependent assessment of EUS might miss smaller but histologically confirmed metastatic nodes (false negatives). The strength of the combined approach lies in its ability to synthesize these divergent pieces of evidence. For instance, a node measuring 9 mm on CT might be considered suspicious, but if EUS reveals it to be hyperechoic and oval with an indis

Therefore, the observed superior performance of the combined approach is not merely additive but potentially syner

The strengths of this study included a consecutive, single-center cohort with complete data (no missing values), the use of postoperative pathology as the gold standard, and the achievement of > 97% accuracy for both T and N staging with a readily available 64-slice CT plus conventional EUS protocol that outperformed previously published international series.

This study had several limitations that should be considered when interpreting its findings. First, its single-center and retrospective nature may introduce selection bias and limits the generalizability of our results to other populations, particularly in regions with different GC epidemiology or healthcare resources. The high diagnostic accuracy observed, while encouraging, requires validation in a larger, multi-institutional prospective cohort to confirm its reproducibility and external validity. Second, our study focused on T and N staging but did not include a formal assessment of distant metastasis (M staging), which is a critical component of comprehensive cancer staging. The integration of additional imaging modalities, such as positron emission tomography CT, in future studies could provide a more holistic view of the impact of the combined approach. Third and importantly our analysis was centered on diagnostic accuracy. We did not investigate the direct impact of this combined strategy on clinical decision-making or patient outcomes. Key questions remain unanswered: How often does the combined approach definitively alter the surgical plan (e.g., leading to endo

Furthermore, the combined approach is not without potential drawbacks, including increased procedural time, higher immediate healthcare costs, and exposure to additional procedural risks (e.g., prolonged sedation for endoscopy/EUS and contrast-related risks for CT). A formal cost-effectiveness and risk-benefit analysis is needed to determine whether the gains in diagnostic precision translate into tangible clinical benefits that outweigh these potential harms. Therefore, we recommend that future research should not only focus on validating these diagnostic performance metrics prospec

The combination of MDCT and gastrointestinal endoscopy improved GC detection, offering higher sensitivity and spe

| 1. | Farinati F, Pelizzaro F. Gastric cancer screening in Western countries: A call to action. Dig Liver Dis. 2024;56:1653-1662. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | López MJ, Carbajal J, Alfaro AL, Saravia LG, Zanabria D, Araujo JM, Quispe L, Zevallos A, Buleje JL, Cho CE, Sarmiento M, Pinto JA, Fajardo W. Characteristics of gastric cancer around the world. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2023;181:103841. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 233] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 3. | Gertsen EC, de Jongh C, Brenkman HJF, Mertens AC, Broeders IAMJ, Los M, Boerma D, Ten Bokkel Huinink D, van Leeuwen L, Wessels FJ, van Hillegersberg R, Ruurda JP. The additive value of restaging-CT during neoadjuvant chemotherapy for gastric cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2020;46:1247-1253. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Sacerdotianu VM, Ungureanu BS, Iordache S, Filip MM, Pirici D, Liliac IM, Saftoiu A. Accuracy of Endoscopic Ultrasonography for Gastric Cancer Staging. Curr Health Sci J. 2022;48:88-94. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Sandø AD, Fougner R, Grønbech JE, Bringeland EA. The value of restaging CT following neoadjuvant chemotherapy for resectable gastric cancer. A population-based study. World J Surg Oncol. 2021;19:212. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Washington K. 7th edition of the AJCC cancer staging manual: stomach. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:3077-3079. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 702] [Cited by in RCA: 820] [Article Influence: 54.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Li S, Yun M, Hong G, Tian L, Yang A, Liu L. Development and validation of a nomogram for preoperative prediction of level VII nodal spread in papillary thyroid cancer: Radiologic-pathologic correlation. Surg Oncol. 2021;37:101520. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | López Sala P, Leturia Etxeberria M, Inchausti Iguíñiz E, Astiazaran Rodríguez A, Aguirre Oteiza MI, Zubizarreta Etxaniz M. Gastric adenocarcinoma: A review of the TNM classification system and ways of spreading. Radiologia (Engl Ed). 2023;65:66-80. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Cha DI, Lee J, Jeong WK, Kim ST, Kim JH, Hong JY, Kang WK, Kim KM, Kim SW, Choi D. Prediction of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition molecular subtype using CT in gastric cancer. Eur Radiol. 2022;32:1-11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Tsujii Y, Hayashi Y, Ishihara R, Yamaguchi S, Yamamoto M, Inoue T, Nagai K, Ogiyama H, Yamada T, Nakahara M, Kizu T, Kanesaka T, Matsuura N, Ohta T, Nakamatsu D, Yoshii S, Shinzaki S, Nishida T, Iijima H, Takehara T. Diagnostic value of endoscopic ultrasonography for the depth of gastric cancer suspected of submucosal invasion: a multicenter prospective study. Surg Endosc. 2023;37:3018-3028. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Conti CB, Agnesi S, Scaravaglio M, Masseria P, Dinelli ME, Oldani M, Uggeri F. Early Gastric Cancer: Update on Prevention, Diagnosis and Treatment. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20:2149. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 36.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Brown AE, Nakakura EK. Optimal Staging for Gastric Cancer Starts With High-Resolution Computed Tomography. JAMA Surg. 2021;156:e215330. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Aslanian HR, Muniraj T, Nagar A, Parsons D. Endoscopic Ultrasound in Cancer Staging. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2024;34:37-49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Park JY, Jeon TJ. Diagnostic evaluation of endoscopic ultrasonography with submucosal saline injection for differentiating between T1a and T1b early gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2022;28:6564-6572. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kim SJ, Lim CH, Lee BI. Accuracy of Endoscopic Ultrasonography for Determining the Depth of Invasion in Early Gastric Cancer. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2022;33:785-792. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Lee KG, Shin CI, Kim SG, Choi J, Oh SY, Son YG, Suh YS, Kong SH, Lee HJ, Kim SH, Lee KU, Kim WH, Yang HK. Can endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) improve the accuracy of clinical T staging by computed tomography (CT) for gastric cancer? Eur J Surg Oncol. 2021;47:1969-1975. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | O'Sullivan NJ, Temperley HC, Horan MT, Curtain BMM, O'Neill M, Donohoe C, Ravi N, Corr A, Meaney JFM, Reynolds JV, Kelly ME. Computed tomography (CT) derived radiomics to predict post-operative disease recurrence in gastric cancer; a systematic review and meta-analysis. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. 2024;53:717-722. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Shinmura K, Yamamoto Y, Inaba A, Okumura K, Nishihara K, Kumahara K, Sunakawa H, Furue Y, Ito R, Sato D, Minamide T, Suyama M, Takashima K, Nakajo K, Murano T, Kadota T, Yoda Y, Hori K, Oono Y, Ikematsu H, Yano T. The safety and feasibility of endoscopic submucosal dissection using a flexible three-dimensional endoscope for early gastric cancer and superficial esophageal cancer: A prospective observational study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;37:749-757. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/