Published online Jan 15, 2026. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v18.i1.110102

Revised: July 5, 2025

Accepted: November 13, 2025

Published online: January 15, 2026

Processing time: 227 Days and 19.1 Hours

Inappropriate selection of patients with early gastric cancer (EGC) for endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) may lead to non-curative resection, necessitating additional gastrectomy. Conversely, inappropriate selection for gastrectomy may result in overtreatment, adversely affecting patients’ quality of life. Few have systematically evaluated the concordance between therapeutic indications under current Japanese guidelines and pathological criteria in EGC. To minimize non

To evaluate EGC clinical decision accuracy by comparing therapeutic indication with postoperative pathological criteria and analyzing factors influencing discrepancies.

A retrospective analysis was conducted on 796 EGC cases diagnosed at Peking University Third Hospital between January 2010 and December 2022. Cases were categorized into three groups: Same-estimated (preoperative therapeutic indica

The accuracy rates of preoperative evaluation for ESD and gastrectomy indications were 73.0% (321/430) and 76.0% (278/366), respectively. The overall discrepancy rate was 25.6% (204/796). Multivariate analysis identified tumor location in the upper-third stomach (odds ratio = 2.158, 95% confidence interval: 1.373-3.390, P = 0.001) was significantly associated with a higher likelihood of being underestimated and undifferentiated histologic type on preoperative biopsy (odds ratio = 2.005, 95% confidence interval: 1.036-3.879, P = 0.039) was more likely to be over

The accuracy of preoperative EGC indications is 74.4%. Upper-third stomach and undifferentiated histology are primary discrepancy predictors. Upper-third tumors are prone to underestimation, while undifferentiated tumors are prone to overestimation.

Core Tip: Current Japanese guideline-based therapeutic indications for early gastric cancer show 74.4% concordance with postoperative pathological criteria in this cohort of 796 patiensts (2010-2022). Key discordance risk factors are tumors in the upper third stomach (prone to pathological underestimation) and undifferentiated histology (prone to overestimation). These findings necessitate heightened preoperative vigilance: endoscopic reevaluation with mapping biopsies for proximal lesions to address technical challenges and avoid non-curative and secondary resections.

- Citation: Jize MYG, Wu W, Ding SG, Zhang J. Discrepancies between preoperative assessment and final pathological criteria in early gastric cancer. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2026; 18(1): 110102

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v18/i1/110102.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v18.i1.110102

Endoscopic resection (ER) is a minimally invasive alternative to gastrectomy for mucosal and submucosal neoplastic lesions. For early gastric cancer (EGC) with lymph node metastasis (LNM) risk < 1%, endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) offers advantages, such as reduced trauma and preserved gastric function, making it the preferred treatment in select cases[1-3]. ER is a localized treatment limited to lesions with low incidence of LNM. However, preoperative imaging cannot definitively exclude LNM, necessitating the reliance on post-ER pathology for accurate assessment[4]. Discrepancies between preoperative indications and postoperative criteria are common[5,6]. While some EGC patients undergo gastrectomy but are later deemed ineligible based on postoperative findings, improper patient selection for surgery can result in unnecessary interventions and compromised quality of life[7]. Conversely, certain EGC patients initially meeting the criteria for ESD may ultimately require additional surgical management due to unexpected pathological outcomes[8,9].

The current Japanese Gastric Cancer Treatment Guidelines (2021; 6th edition)[4] (hereinafter, Japanese Guidelines) provide a key framework for managing EGC. However, the evidence grades and recommendation levels for ER - particularly for undifferentiated EGC (UD-EGC) - differ across Japan, China, South Korea, and Western countries due to regional heterogeneity in EGC pathological characteristics. Recently, ER indications have expanded globally. As non-Japanese guidelines lag slightly behind, we aim to validate the Japanese Guidelines’ applicability in non-Japanese populations and discuss their adaptation to promote ER for UD-EGC outside Japan[10]. Growing evidence[11-13] confirms significant interregional variations in EGC pathology and treatment response, underscoring the need for ongoing validation and state-level customization of clinical guidance based on real-world practice.

This study aimed to evaluate the applicability of the Japanese Gastric Cancer Treatment Guidelines 2021 (6th edition)[4] in 796 ESD and surgical specimens of EGC by assessing the concordance rate between preoperative endoscopic biopsy and final histopathological diagnosis, analyzing factors contributing to diagnostic discrepancies. We evaluated these discrepancies and their contributing factors to optimize clinical decision-making. While previous studies explored associations between tumor size, location, ulceration, and noncurative resection, few systematically evaluated concordance between preoperative indications and postoperative pathological criteria in EGC. Although Jeon et al[8] identified significant endoscopic-pathological discrepancies, their study excluded surgical candidates. To minimize noncurative resection risks while sparing low-risk patients from unnecessary surgery, we identified clinically useful predictors of indication-pathology discordance before treatment initiation. Furthermore, because Song et al[14] validated expanded indications globally via multinational cohorts, we also assessed Japanese guideline suitability in non-Japanese popula

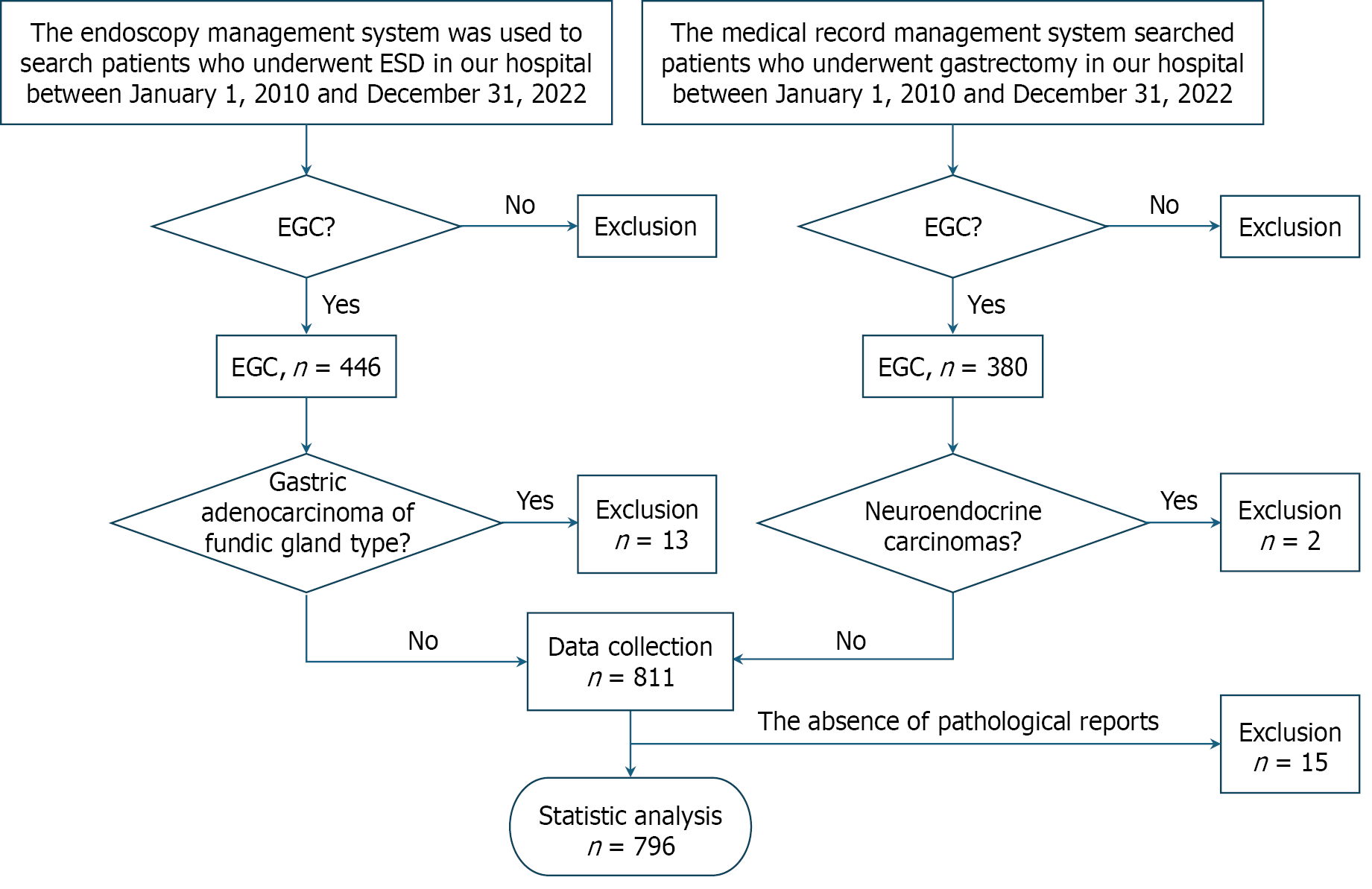

This retrospective study analyzed patients diagnosed with EGC at Peking University Third Hospital from January 2010 to December 2022. The cohort comprised 446 patients treated with ER and 380 patients that were surgically managed. Among 826 initially identified lesions, 28 were excluded: 13 cases of gastric adenocarcinoma of fundic gland type, 2 neuroendocrine carcinomas, and 15 cases with incomplete preoperative or postoperative pathological data. The final analysis included 796 histologically confirmed EGC lesions (Figure 1). Fundic gland type gastric adenocarcinomas and neuroendocrine carcinomas were excluded given their pathological distinction from gastric adenocarcinomas, fundamen

This study evaluated 796 EGC cases through preoperative examination and categorized them into two therapeutic indication groups according to the Japanese guidelines[4]: 537 lesions (67.5%) met ESD indications and 259 (32.5%) required surgical intervention. We then evaluated pathological outcomes according to the endoscopic curability (eCura) classification system. Final pathological evaluation of resected specimens further classified cases into ESD criteria (eCura A/B); and surgical criteria (eCura C-2), while expanded criteria cases (eCura C-1) received treatment based on follow-up findings. Based on the concordance between preoperative therapeutic indications and final pathological criteria, cases were stratified into three groups: Same-estimated, underestimated, and overestimated. For same-estimated cases, post

Histological discrepancy: Pathologic types were classified into two types according to the World Health Organization classification of gastric cancer as epithelial tumors and carcinoid tumors[15]. For analytical purposes, tumors were categorized as differentiated (well or moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma), undifferentiated (poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma, signet ring cell carcinoma, or mixed-type carcinoma).

Comorbidity: Presence of ≥ 1 systemic diseases (hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, cardiovascular disease, cere

Tumor characteristics: Macroscopic morphological classification according to the Paris endoscopic classification system[16] categorizing lesions as elevated (types 0-I and 0-IIa), flat (type 0-IIb) or depressed (types 0-IIc and 0-III) and detailed dimensional assessment incorporating tumor size measurements and ulceration status evaluation through a combination of endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) for depth analysis, white light imaging for initial characterization, and magnifying narrow-band imaging (NBI) for precise margin delineation and surface pattern analysis. And comprehensive metastasis evaluation using contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) combined with EUS for assessment of nodal involve

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 22.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States) with rigorous methodology implemented as follows: Continuous variables were assessed for normality using Shapiro-Wilk tests. Normally distributed data are presented as mean ± SD; non-normally distributed data are expressed as median (interquartile range). Categorical variables were analyzed using χ2 tests, with Fisher’s exact test applied when any expected cell frequency was ≤ 5. Data are presented as frequencies (percentages) for categorical variables. Our analytical approach proceeded in two stages: First, univariate analysis (χ2 or Fisher’s exact test) identified potential risk factors using a significance threshold of P < 0.05. Subsequently, all significant variables were entered into multivariate logistic regression models to determine independent predictors. Results are reported as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and corresponding regression coefficients. Throughout all analyses, statistical significance was defined as two-tailed P < 0.05.

This retrospective analysis evaluated 796 patients with histologically confirmed EGC. The cohort exhibited a male predominance (70.0%, n = 557) and the age showed right-skewed distribution (Shapiro-Wilk P < 0.01) with a median 64 years (interquartile range 57-71). Treatment modalities were distributed between ER (54.0%, n = 430) and surgical intervention (46.0%, n = 366). Comparative analysis between preoperative endoscopic assessment and postoperative pathological evaluation revealed significant stratification: (1) Concordant group (same-estimated): 74.4% (n = 592); (2) Therapeutic upgrade group (underestimated lesions requiring treatment intensification): 20.4% (n = 162); and (3) Therapeutic de-escalation group (overestimated lesions eligible for less invasive management): 5.3% (n = 42). These findings demonstrate that while three-quarters of cases were accurately staged preoperatively, one-quarter exhibited clinically significant discrepancies that could substantially impact therapeutic decision-making. The substantial pro

The cohort comprised 796 cases with the following preoperative treatment allocation: ESD indications (67.5%, 537/796) and surgical indications (32.5%, 259/796) (Tables 1 and 2). In our study of 430 endoscopically treated patients, 130 underwent non-curative resections after ESD, yielding a non-curative resection rate of 30.23%. Following ESD, the additional surgery rate was 6.15% (8/130). Subsequent management included additional ESD in 34 patients and regular follow-up in 88 patients. Among the 85 patients that did not receive any further treatment, reasons included patient preference (n = 38), advanced age (n = 7), comorbidities (n = 5), and unknown factors (n = 35). Notably, among 42 cases meeting expanded ESD criteria (eCura C-1), 81.0% (34/42) achieved curative resection through ESD, while 19.0% (8/42) required surgical conversion. Of these converted cases, 62.5% (5/8) were subsequently deemed pathologically suitable for ESD, suggesting potential overtreatment.

| Variable | Total | Post-ESD criteria | ||

| Absolute criteria | Expand criteria | Surgery criteria | ||

| Pre-ESD indication | ||||

| Absolute indication | 407 | 256 (62.9) | 40 (9.9) | 109 (26.8) |

| Surgery indication | 25 | 2 (8.0) | 2 (8.0) | 21 (84.0) |

| Total | 430 | 258 (59.7) | 44 (9.8) | 130 (30.1) |

| Variable | Total | Post-surgery criteria | |

| ESD criteria | Surgery criteria | ||

| Pre-surgery indication | |||

| Surgery indication | 234 | 38 (10.40) | 196 (53.60) |

| ESD indication | 132 | 82 (22.40) | 50 (3.60) |

| Total | 366 | 120 (32.80) | 246 (67.20) |

Univariate analysis of the three diagnostic discrepancy groups (same-estimated, underestimated, and overestimated) revealed distinct patterns (Tables 3 and 4). Among baseline characteristics, neither age (P = 0.350) nor sex distribution (P = 0.847) showed significant associations. Similarly, lifestyle factors including alcohol consumption (P = 0.255) and established risk factors such as family history of gastric cancer (P = 0.109) and Helicobacter pylori infection status (P = 0.200) were not significantly different between groups. Similarly, tumor morphological features including maximum diameter (P = 0.072), macroscopic appearance (P = 0.698), and ulceration presence (P = 0.415) were not significantly different across groups.

| Variable | Same (n = 592) | Under (n = 162) | Over (n = 42) | χ2 value | P value |

| Age | 2.097 | 0.350 | |||

| ≤ 60 | 228 (38.5) | 52 (32.7) | 14 (33.3) | ||

| > 60 | 364 (61.5) | 107 (67.3) | 28 (66.7) | ||

| Sex | 0.332 | 0.847 | |||

| Male | 411 (69.4) | 116 (71.6) | 30 (71.4) | ||

| Female | 181 (30.6) | 46 (28.4) | 12 (28.6) | ||

| History of smoking | 6.215 | 0.044 | |||

| No | 391 (66.0) | 90 (55.6) | 27 (64.3) | ||

| Yes | 201 (34.0) | 72 (44.4) | 15 (35.7) | ||

| History of alcohol consumption | 2.732 | 0.255 | |||

| No | 432 (73.0) | 110 (67.9) | 26 (65.0) | ||

| Yes | 160 (27.0) | 52 (32.1) | 14 (35.0) | ||

| Family history | 4.436 | 0.109 | |||

| No | 510 (86.1) | 148 (91.4) | 34 (81.0) | ||

| Yes | 82 (13.9) | 14 (8.6) | 8 (19.0) | ||

| Helicobacter pylori infection | 3.220 | 0.200 | |||

| No | 421 (71.1) | 104 (64.2) | 31 (73.8) | ||

| Yes | 171 (28.9) | 58 (35.8) | 11 (26.2) |

| Variable | Same (n = 592) | Under (n = 162) | Over (n = 42) | χ2 value | P value |

| Pre-endoscopic findings | |||||

| Location | 8.132 | < 0.001 | |||

| Upper | 111 (18.8) | 65 (38.3) | 12 (30.0) | ||

| Middle | 232 (39.2) | 51 (31.5) | 14 (32.5) | ||

| Lower | 249 (42.1) | 49 (30.2) | 16 (37.5) | ||

| Size (cm) | 8.590 | 0.072 | |||

| ≤ 2 cm | 401 (67.7) | 112 (69.1) | 23 (57.5) | ||

| > 2 cm and ≤ 3 cm | 122 (20.6) | 37 (22.8) | 9 (22.5) | ||

| > 3 cm | 69 (11.7) | 12 (8.0) | 10 (20.0) | ||

| Gross type | 2.204 | 0.698 | |||

| Elevated | 282 (47.6) | 74 (45.7) | 16 (38.1) | ||

| Flat | 220 (37.2) | 65 (40.1) | 20 (47.6) | ||

| Depressed | 90 (15.2) | 23 (14.2) | 6 (14.3) | ||

| Presence of ulcers | 1.761 | 0.415 | |||

| No | 423 (71.5) | 117 (72.2) | 34 (81.0) | ||

| Yes | 169 (28.5) | 45 (27.8) | 8 (19.0) | ||

| Pathology | 53.839 | < 0.001 | |||

| Differentiated | 411 (69.9) | 156 (96.3) | 24 (57.1) | ||

| Undifferentiated | 178 (30.1) | 6 (3.7) | 18 (42.9) | ||

However, three variables emerged as significantly associated with diagnostic discrepancies: Smoking history (P = 0.044), anatomical tumor location (P = 0.001), and histopathological classification (P < 0.001). These suggest that tumor location, particularly in the upper gastric third, and undifferentiated histopathology represent important determinants of assessment accuracy, while traditional demographic and morphological parameters show limited predictive value. The borderline significance of smoking history (P = 0.044) requires cautious interpretation given multiple comparisons, suggesting a need for validation in larger cohorts.

Multivariate logistic regression analysis revealed two independent predictors of discordance between preoperative assessments and final pathology (Tables 5 and 6): Upper gastric third location (OR = 2.158, 95%CI: 1.373-3.390, P = 0.001), with 38.3% of these lesions being significantly underestimated (P < 0.001), and undifferentiated histopathology (OR = 2.005, 95%CI: 1.036-3.879, P = 0.039), where 42.9% of cases demonstrated significant overestimation (P < 0.001). These findings underscore the distinct diagnostic challenges posed by proximal gastric lesions and poorly differentiated histopathology, necessitating improved preoperative staging techniques for upper gastric tumors and optimized biopsy protocols for undifferentiated carcinomas to guide precision treatment planning.

| Variable | P value | Exp(B) | 95% confidence interval | ||

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| Under-estimated | |||||

| History of smoking | Yes | 0.108 | 1.357 | 0.935 | 1.969 |

| No | Reference | ||||

| Location | Upper | < 0.001 | 2.158 | 1.373 | 3.390 |

| Middle | 0.536 | 1.151 | 0.738 | 1.794 | |

| Lower | Reference | ||||

| Pathology | Undifferentiated | < 0.001 | 0.104 | 0.045 | 0.241 |

| Differentiated | Reference | ||||

| Over-estimated | |||||

| History of smoking | Yes | 0.871 | 0.945 | 0.483 | 1.846 |

| No | Reference | ||||

| Location | Upper | 0.790 | 1.984 | 0.888 | 4.435 |

| Middle | 0.851 | 0.916 | 0.436 | 1.923 | |

| Lower | Reference | ||||

| Pathology | Undifferentiated | 0.416 | 2.005 | 1.036 | 3.879 |

| Differentiated | Reference | ||||

| Variable | P value | Exp(B) | 95% confidence interval | ||

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| Under-estimated | |||||

| History of smoking | Yes | 0.331 | 1.436 | 0.692 | 2.980 |

| No | Reference | ||||

| Location | Upper | 0.851 | 1.087 | 0.454 | 2.602 |

| Middle | 0.592 | 1.257 | 0.545 | 2.896 | |

| Lower | Reference | ||||

| Pathology | Undifferentiated | < 0.001 | 0.052 | 0.018 | 0.146 |

| Differentiated | Reference | ||||

In this comparative analysis of 796 EGC cases, clinically significant discrepancies emerged between preoperative biopsies and final pathology (Table 7). Critical diagnostic variances occurred in tumor diameter measurement (13.9%, 111/796), invasion depth assessment (25.3%, 201/796), and histopathological classification (17.1%, 136/796). Pathology reclassification analysis demonstrated frequent diagnostic upgrades (69.9%, 95/136). Notably, ulceration evaluation errors occurred in 4.9% (39/796) of cases, with biopsy-based overestimations constituting 84.6% (33/39) of cases.

| Postoperative pathology | Pretreatment diagnosis | n = 796 | Misdiagnosis rate (%) |

| Tumor diameter | |||

| ≤ 3 cm | ≤ 3 cm (accurate) | 626 (78.6) | |

| > 3 cm (misdiagnosis) | 33 (4.2) | 14.0 | |

| > 3 cm | ≤ 3 cm (misdiagnosis) | 78 (9.8) | |

| > 3 cm (accurate) | 59 (7.4) | ||

| Depth | |||

| Mucosal invasion | Mucosal invasion or submucosal invasion: < 500 μm (accurate) | 577 (72.2) | |

| Submucosal invasion: ≥ 500 μm (misdiagnosis) | 37 (4.7) | 25.3 | |

| Submucosal invasion | Mucosal invasion or submucosal invasion: < 500 μm (misdiagnosis) | 164 (20.6) | |

| Submucosal invasion: ≥ 500 μm (accurate) | 20 (2.5) | ||

| Ulcerative findings | |||

| Absence | Absence (accurate) | 217 (27.1) | |

| Presence (misdiagnosis) | 33 (4.1) | 4.9 | |

| Presence | Absence (misdiagnosis) | 6 (0.8) | |

| Presence (accurate) | 542 (68.0) | ||

| Main histology | |||

| Differentiated type | Differentiated type (accurate) | 499 (62.7) | 17.1 |

| Undifferentiated type (misdiagnosis) | 41 (5.2) | ||

| Undifferentiated type | Differentiated type (misdiagnosis) | 95 (11.9) | |

| Undifferentiated type (accurate) | 161 (20.2) | ||

These findings underscore three critical clinical challenges: (1) The 25.3% depth underestimation rate reflects limi

Further analysis of pathological parameters among the three diagnostic groups (same-estimated, underestimated, and overestimated) revealed significant variations in multiple critical features (Table 8). Lesions in the underestimated group typically exhibited deeper submucosal invasion (51.9% vs 18.1%), while overestimated cases were predominantly characterized by undifferentiated histology (35.7% vs 7.4%) and more frequent ulceration (17.5% vs 3.5%). These findings underscore three critical clinical considerations: Tumor dimensional assessment and ulcer status serve as essential parameters for pretreatment evaluation accuracy, inherent histological heterogeneity represents a major contributor to diagnostic discordance, and existing staging protocols may need optimization, particularly for undifferentiated and deeply invasive subtypes.

| Variable | Same (n = 592) | Under (n = 162) | Over (n = 42) | χ2 value | P value |

| Diagnosis of tumor diameter | 15.067 | < 0.001 | |||

| Accurate diagnosis | 526 (88.9) | 126 (77.8) | 33 (82.5) | ||

| Misdiagnosis | 66 (11.1) | 36 (22.2) | 9 (21.4) | ||

| Diagnosis of depth | 76.933 | < 0.001 | |||

| Accurate diagnosis | 485 (81.9) | 78 (48.1) | 32 (76.2) | ||

| Misdiagnosis | 107 (18.1) | 84 (51.9) | 10 (23.8) | ||

| Diagnosis of ulcerative findings | 16.047 | < 0.001 | |||

| Accurate diagnosis | 571 (96.5) | 151 (93.2) | 35 (82.5) | ||

| Misdiagnosis | 21 (3.5) | 11 (6.8) | 7 (17.5) | ||

| Diagnosis of main histology | |||||

| Accurate diagnosis | 548 (92.6) | 85 (52.5) | 27 (64.3) | 155.227 | < 0.001 |

| Misdiagnosis | 44 (7.4) | 77 (47.5) | 15 (35.7) |

The multivariate logistic regression analysis identified several significant factors associated with diagnostic discrepancies between preoperative assessment and postoperative findings. Compared with the same-estimated, tumor diameter misclassification (OR = 2.555, 95%CI: 1.515-4.309, P < 0.001), depth of infiltration underestimation (OR = 4.641, 95%CI: 3.049-7.064, P < 0.001), ulcerative findings discrepancy (OR = 3.065, 95%CI: 1.346-6.979, P = 0.008) and histological type misdiagnosis (OR = 11.220, 95%CI: 7.030-17.908, P < 0.001) were significantly common in the underestimated group. Therefore, during preoperative evaluation for ESD, tumor diameter, depth of infiltration, ulcerative findings, and main histology type should be carefully assessed (Table 9). The analysis revealed statistically significant differences in misdiagnosis rates between overestimated and accurate cases, particularly for tumor size (OR = 2.339, 95%CI: 1.044-5.242, P = 0.039), ulcerative findings (OR = 6.805, 95%CI: 2.612-17.729, P < 0.001) and main histology type (OR = 7.691, 95%CI: 3.774-15.797, P < 0.001). Consequently, special attention should be paid to the preoperative evaluation of tumor diameter, ulcerative findings, and main histology type when planning gastrectomy procedures (Table 10).

| Variable | P value | Exp(B) | 95% confidence interval | ||

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| Under-estimated | |||||

| Diagnosis of tumor diameter | Accurate diagnosis | Reference | |||

| Misdiagnosis | < 0.001 | 2.555 | 1.515 | 4.309 | |

| Diagnosis of depth | Accurate diagnosis | Reference | |||

| Misdiagnosis | < 0.001 | 4.641 | 3.049 | 7.064 | |

| Diagnosis of ulcerative findings | Accurate diagnosis | Reference | |||

| Misdiagnosis | 0.008 | 3.065 | 1.346 | 6.979 | |

| Diagnosis of main histology | Accurate diagnosis | Reference | |||

| Misdiagnosis | < 0.001 | 11.220 | 7.030 | 17.908 | |

| Over-estimated | |||||

| Diagnosis of tumor diameter | Accurate diagnosis | Reference | |||

| Misdiagnosis | 0.039 | 2.339 | 1.044 | 5.242 | |

| Diagnosis of depth | Accurate diagnosis | Reference | |||

| Misdiagnosis | 0.372 | 1.414 | 0.660 | 3.030 | |

| Diagnosis of ulcerative findings | Accurate diagnosis | Reference | |||

| Misdiagnosis | < 0.001 | 6.805 | 2.612 | 17.729 | |

| Diagnosis of main histology | Accurate diagnosis | Reference | |||

| Misdiagnosis | < 0.001 | 7.691 | 3.774 | 15.797 | |

| Variable | P value | Exp(B) | 95% confidence interval | ||

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| Under-estimated | |||||

| Diagnosis of tumor diameter | Accurate diagnosis | Reference | |||

| Misdiagnosis | 0.838 | 1.092 | 0.469 | 2.544 | |

| Diagnosis of depth | Accurate diagnosis | Reference | |||

| Misdiagnosis | 0.003 | 3.281 | 1.504 | 7.156 | |

| Diagnosis of ulcerative findings | Accurate diagnosis | Reference | |||

| Misdiagnosis | 0.135 | 0.450 | 0.158 | 1.282 | |

| Diagnosis of main histology | Accurate diagnosis | Reference | |||

| Misdiagnosis | 0.307 | 1.459 | 0.707 | 3.010 | |

In this study, we observed a discrepancy rate of 25.6% between preoperative indications and postoperative pathologic criteria for EGC treatment. Specifically, 27.7% (112/405) of lesions initially deemed suitable for ESD were postoperatively classified as non-curative, necessitating additional gastrectomy. Conversely, 16.2% (42/259) of cases preoperatively assessed as gastrectomy candidates were ultimately found to be free of LNM and eligible for endoscopic indications.

Among ESD-treated patients, 25 had been preoperatively classified as gastrectomy indications, with 84% (21/25) con

Previous studies have demonstrated that the upper gastric location is a risk factor for nonradical ESD resection in EGC[21-26]. This is attributed to the anatomical complexity of the cardia and gastric fundus, where both the gastric wall and submucosa are thinner than in other regions, with small lymphocapillaries directly above the muscularis mucosae[27]. Consequently, these areas represent technically challenging sites for endoscopic procedures, leading to higher rates of deep submucosal invasion and positive margins in upper-third tumors. Thus, in our study, tumors located in the upper third were more frequently underestimated due to noncurative resection.

If upper gastric cancer is underestimated, ESD may be incorrectly selected, resulting in non-curative resection, the need for additional surgery, or progression of residual tumors to advanced stages. Besides, the thin wall of the upper gastric segment, adjacent to large blood vessels and esophagus, is easy to perforate or bleed intraoperatively. If the extent of tumor is underestimated before surgery, the difficulty of surgery increases abruptly, the rate of intermediate open abdomen rises, and the risk of anastomotic fistula increases after surgery[27].

Multiple studies have confirmed that UD-EGC is a risk factor for noncurative resection[21-26]. These tumors exhibit greater propensity for deep invasion and extensive intramural spreading. Consequently, the actual tumor size in resected specimens frequently exceeds endoscopic estimates[22,24,28]. Preoperative diagnosis of mixed-type EGC remains challenging due to the absence of standardized criteria[29]. Initial biopsies may misclassify mixed-type EGCs as purely undifferentiated[21]. When biopsy reveals UD-EGC but suspected differentiated components are endoscopically visible, clinicians should strongly consider mixed-type histology. This recognition could prevent unnecessary gastrectomy in eligible cases. Therefore, in our study, undifferentiated tumors were more frequently overestimated. As further sup

Because of overestimation of tumor pathologic type, total gastrectomy may be chosen instead of distal resection, resulting in significant impairment of quality of life. Overestimation of staging may lead to overuse of adjuvant chemotherapy with increased chemotherapy toxicity and no survival benefit. Undifferentiated carcinoma that is overestimated as a deep infiltration may result in loss of opportunity for ESD, with the patient being forced to undergo a more invasive surgical procedure, repeated tests and over-intervention. Overestimation of lesion extent may lead to multiple biopsies, repeated imaging, and even secondary surgery, resulting in increased diagnostic costs for patients.

We suggest that for upper gastric lesions, mandatory EUS combined with magnifying NBI should be used for in-depth evaluation, and biopsy must follow the multisite sampling scheme of “center-margin-junction”, supplemented with immunohistochemistry to confirm the differentiation status when indolent cell carcinoma is suspected. Advanced imaging techniques enable real-time histological analysis of living tissue during routine endoscopy and can reduce the number of biopsies needed for correct diagnosis, thereby minimizing the risk of sampling error[30]. For controversial cases (e.g., technical difficulties in the upper third of gastric tumors or unclear borders of undifferentiated carcinoma), multidisciplinary collaboration help avoid decision-making bias to ultimately achieve precise individualized treatment.

In this study, the depth of infiltration and pathologic types were the most common reasons for the differences. However, pre-treatment screening assessments had a limited role in predicting tumor infiltration depth. Depth of infiltration is highly correlated with LNM, and routine assessment using EUS did not improve the accuracy of predicting depth of invasion compared to endoscopy[31]. Diagnosis can often only be confirmed by pathological evaluation of the resected specimen. In predicting tumor infiltration depth, the overall accuracy by conventional endoscopy was 73%-82%, with endoscopy accurately detecting mucosal carcinomas and EUS effectively salvaging endoscopically overrated lesions. Previous studies have shown that the combined use of endoscopy and EUS results in a combined accuracy that can be greater than 85%[31,32]. Regarding LNM assessment, preoperative evaluation by contrast-enhanced CT alone identified 76 patients with suspected lymph node involvement in this study. In contrast, EUS combined with contrast-enhanced CT identified 53 patients with suspected involvement. According to postoperative pathology criteria, only 39 cases were ultimately confirmed to have LNM. Thus, the EUS + CT combination achieved 90.45% diagnostic accuracy (vs 73.59% for CT alone). Notably, in this non-blinded clinical series, some enlarged lymph nodes initially suspected of regional metastasis were pathologically confirmed as reactive lymphoid hyperplasia. Previous studies have demonstrated that EUS has superior sensitivity to CT for detecting regional LNM[33]. Therefore, combining EUS with CT reduces regional LNM rates, a direction warranting further exploration. These limitations in preoperative evaluation are the main reason for the discrepancy between pre-EGC indications and postoperative pathologic criteria. If possible, further studies are needed on more accurate methods to predict the presence of LNM.

This study benefits from a large cohort of ESD and gastrectomy-treated EGCs, with comprehensive analysis of indication-pathology discrepancies and associated risk factors - key data for refining therapeutic decision-making. However, this study was a single-center retrospective study, and it is indeed possible that there was selection bias. While we acknowledge that regional variations in medical practice may introduce potential selection bias, our findings remain applicable to EGC patients receiving care in tertiary hospitals within China. Further studies are needed to validate our preliminary findings. Beyond this, limitations include potential selection bias, variability in preoperative assessments (e.g., inconsistent use of NBI/EUS), and inter-endoscopist differences in lesion evaluation.

While preoperative endoscopy correctly identified EGC indications in 74.4% of cases, discrepancies were strongly associated with upper-third tumors and undifferentiated histology. To optimize outcomes, we recommend heightened vigilance for upper-third lesions, including preoperative counseling about possible non-curative ESD, and second-line assessment of undifferentiated tumors to avoid unnecessary gastrectomy when ESD may suffice.

We sincerely thank Yan-Yan Shi for invaluable guidance and critical review of the manuscript. We are grateful to Ying-Tong Chen for guiding us in manuscript writing. Special thanks to Jing-Jin Tan, Ji-Li Wang, Wei-Yang Shu, Xin Huang and my family for their unwavering support.

| 1. | Shichijo S, Uedo N, Kanesaka T, Ohta T, Nakagawa K, Shimamoto Y, Ohmori M, Arao M, Iwatsubo T, Suzuki S, Matsuno K, Iwagami H, Inoue S, Matsuura N, Maekawa A, Nakahira H, Yamamoto S, Takeuchi Y, Higashino K, Ishihara R, Fukui K, Ito Y, Narahara H, Ishiguro S, Iishi H. Long-term outcomes after endoscopic submucosal dissection for differentiated-type early gastric cancer that fulfilled expanded indication criteria: A prospective cohort study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;36:664-670. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Guo A, Du C, Tian S, Sun L, Guo M, Lu L, Peng L. Long-term outcomes of endoscopic submucosal dissection versus surgery for treating early gastric cancer of undifferentiated-type. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99:e20501. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ahn JY, Kim YI, Shin WG, Yang HJ, Nam SY, Min BH, Jang JY, Lim JH, Kim J-, Lee WS, Lee BE, Joo MK, Park JM, Lee HL, Gweon TG, Park MI, Choi J, Tae CH, Kim YW, Park B, Choi IIJ. Comparison between endoscopic submucosal resection and surgery for the curative resection of undifferentiated-type early gastric cancer within expanded indications: a nationwide multi-center study. Gastric Cancer. 2021;24:731-743. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese Gastric Cancer Treatment Guidelines 2021 (6th edition). Gastric Cancer. 2023;26:1-25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 199] [Cited by in RCA: 813] [Article Influence: 271.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 5. | Abdelfatah MM, Barakat M, Lee H, Kim JJ, Uedo N, Grimm I, Othman MO. The incidence of lymph node metastasis in early gastric cancer according to the expanded criteria in comparison with the absolute criteria of the Japanese Gastric Cancer Association: a systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2018;87:338-347. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kim YI, Kim HS, Kook MC, Cho SJ, Lee JY, Kim CG, Ryu KW, Kim YW, Choi IJ. Discrepancy between Clinical and Final Pathological Evaluation Findings in Early Gastric Cancer Patients Treated with Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection. J Gastric Cancer. 2016;16:34-42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Na JE, Lee H, Min YW, Min BH, Lee JH, Rhee PL, Kim KM, Kim JJ. Clinical feasibility and oncologic safety of primary endoscopic submucosal dissection for clinical submucosal invasive early gastric cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2021;147:3051-3061. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Jeon SW, Park HW, Kwon YH, Nam SY, Lee HS. Endoscopic Indication of Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection for Early Gastric Cancer Is Not Compatible with Pathologic Criteria in Clinical Practice. Dig Dis Sci. 2019;64:373-381. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Sohn SH, Lee SH, Kim KO, Jang BI, Kim TN. Therapeutic outcomes of endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancer: single-center study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;29:61-67. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Hirai Y, Abe S, Makiguchi ME, Sekiguchi M, Nonaka S, Suzuki H, Yoshinaga S, Saito Y. Endoscopic Resection of Undifferentiated Early Gastric Cancer. J Gastric Cancer. 2023;23:146-158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Chiarello MM, Fico V, Pepe G, Tropeano G, Adams NJ, Altieri G, Brisinda G. Early gastric cancer: A challenge in Western countries. World J Gastroenterol. 2022;28:693-703. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 12. | Nam MJ, Oh SJ, Oh CA, Kim DH, Bae YS, Choi MG, Noh JH, Sohn TS, Bae JM, Kim S. Frequency and predictive factors of lymph node metastasis in mucosal cancer. J Gastric Cancer. 2010;10:162-167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Fang WL, Huang KH, Lan YT, Chen MH, Chao Y, Lo SS, Wu CW, Shyr YM, Li AF. The Risk Factors of Lymph Node Metastasis in Early Gastric Cancer. Pathol Oncol Res. 2015;21:941-946. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Song JH, Lee S, Park SH, Kottikias A, Abdulmohsen A, Alrashidi N, Cho M, Kim YM, Kim HI, Hyung WJ. Applicability of endoscopic submucosal dissection for patients with early gastric cancer beyond the expanded indication for endoscopic submucosal dissection. Surg Endosc. 2022;36:8349-8357. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Fléjou JF. [WHO Classification of digestive tumors: the fourth edition]. Ann Pathol. 2011;31:S27-S31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 196] [Article Influence: 13.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | The Paris endoscopic classification of superficial neoplastic lesions: esophagus, stomach, and colon: November 30 to December 1, 2002. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:S3-43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1117] [Cited by in RCA: 1370] [Article Influence: 59.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (13)] |

| 17. | Schlemper RJ, Riddell RH, Kato Y, Borchard F, Cooper HS, Dawsey SM, Dixon MF, Fenoglio-Preiser CM, Fléjou JF, Geboes K, Hattori T, Hirota T, Itabashi M, Iwafuchi M, Iwashita A, Kim YI, Kirchner T, Klimpfinger M, Koike M, Lauwers GY, Lewin KJ, Oberhuber G, Offner F, Price AB, Rubio CA, Shimizu M, Shimoda T, Sipponen P, Solcia E, Stolte M, Watanabe H, Yamabe H. The Vienna classification of gastrointestinal epithelial neoplasia. Gut. 2000;47:251-255. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1463] [Cited by in RCA: 1574] [Article Influence: 60.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Wang P, Zhao X, Wang R, Xu D, Yang H. Risk factors for pathological upgrading and noncurative resection in patients with gastric mucosal lesions after endoscopic submucosal dissection. BMC Gastroenterol. 2024;24:253. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Ryu DG, Choi CW, Kang DH, Kim HW, Park SB, Kim SJ, Nam HS. Pathologic outcomes of endoscopic submucosal dissection for gastric epithelial neoplasia. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e11802. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Kim TS, Min BH, Kim KM, Yoo H, Kim K, Min YW, Lee H, Rhee PL, Kim JJ, Lee JH. Risk-Scoring System for Prediction of Non-Curative Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection Requiring Additional Gastrectomy in Patients with Early Gastric Cancer. J Gastric Cancer. 2021;21:368-378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Toyokawa T, Inaba T, Omote S, Okamoto A, Miyasaka R, Watanabe K, Izumikawa K, Fujita I, Horii J, Ishikawa S, Morikawa T, Murakami T, Tomoda J. Risk factors for non-curative resection of early gastric neoplasms with endoscopic submucosal dissection: Analysis of 1,123 lesions. Exp Ther Med. 2015;9:1209-1214. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 22. | Fu QY, Cui Y, Li XB, Chen P, Chen XY. Relevant risk factors for positive lateral margin after en bloc endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric adenocarcinoma. J Dig Dis. 2016;17:244-251. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Kim EH, Park JC, Song IJ, Kim YJ, Joh DH, Hahn KY, Lee YK, Kim HY, Chung H, Shin SK, Lee SK, Lee YC. Prediction model for non-curative resection of endoscopic submucosal dissection in patients with early gastric cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;85:976-983. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Xu P, Wang Y, Dang Y, Huang Q, Wang J, Zhang W, Zhang Y, Zhang G. Predictive Factors and Long-Term Outcomes of Early Gastric Carcinomas in Patients with Non-Curative Resection by Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection. Cancer Manag Res. 2020;12:8037-8046. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Embaye KS, Zhang C, Ghebrehiwet MA, Wang Z, Zhang F, Liu L, Qin S, Qin L, Wang J, Wang X. Clinico-pathologic determinants of non-e-curative outcome following en-bloc endoscopic submucosal dissection in patients with early gastric neoplasia. BMC Cancer. 2021;21:92. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Guo L, Ding Y, Wen J, Miao M, Hu K, Ye G. Risk factors and predictive nomogram for non-curative resection in patients with early gastric cancer treated with endoscopic submucosal dissection: a retrospective cohort study. World J Surg Oncol. 2025;23:213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Akashi Y, Noguchi T, Nagai K, Kawahara K, Shimada T. Cytoarchitecture of the lamina muscularis mucosae and distribution of the lymphatic vessels in the human stomach. Med Mol Morphol. 2011;44:39-45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Bang CS, Yang YJ, Lee JJ, Baik GH. Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection of Early Gastric Cancer with Mixed-Type Histology: A Systematic Review. Dig Dis Sci. 2020;65:276-291. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Kim Y, Yoon HJ, Kim JH, Chun J, Youn YH, Park H, Kwon IG, Choi SH, Noh SH. Effect of histologic differences between biopsy and final resection on treatment outcomes in early gastric cancer. Surg Endosc. 2020;34:5046-5054. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Sumiyama K. Past and current trends in endoscopic diagnosis for early stage gastric cancer in Japan. Gastric Cancer. 2017;20:20-27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Tsujii Y, Kato M, Inoue T, Yoshii S, Nagai K, Fujinaga T, Maekawa A, Hayashi Y, Akasaka T, Shinzaki S, Watabe K, Nishida T, Iijima H, Tsujii M, Takehara T. Integrated diagnostic strategy for the invasion depth of early gastric cancer by conventional endoscopy and EUS. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;82:452-459. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Kim SJ, Choi CW, Kang DH, Kim HW, Park SB, Nam HS, Shin DH. Factors associated with the efficacy of miniprobe endoscopic ultrasonography after conventional endoscopy for the prediction of invasion depth of early gastric cancer. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2017;52:864-869. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | van Vliet EP, Heijenbrok-Kal MH, Hunink MG, Kuipers EJ, Siersema PD. Staging investigations for oesophageal cancer: a meta-analysis. Br J Cancer. 2008;98:547-557. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 336] [Cited by in RCA: 349] [Article Influence: 19.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |