Published online Jan 15, 2026. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v18.i1.109735

Revised: July 24, 2025

Accepted: November 28, 2025

Published online: January 15, 2026

Processing time: 202 Days and 2.6 Hours

Elderly patients with colorectal cancer (CRC) can judge the risk of postoperative complications and oncological outcomes due to visceral obesity, which can pro

To explore the effect of visceral obesity on postoperative complications and on

A total of 150 elderly patients who underwent radical surgery for CRC at Inner Mongolia Medical University and Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region People’s Hospital from January 2021 to June 2024 were retrospectively analyzed. Patients were divided into the abdominal [visceral fat area (VFA) ≥ 100.00 cm2, n = 80] and non-abdominal (VFA < 100.00 cm2, n = 70) obesity groups according to the VFA measured by preoperative computed tomography. The two groups showed no significant differences in age, sex, tumor location, tumor-node-metastasis stage, and underlying disease (P > 0.05). All patients underwent standardized laparoscopic assisted surgery and received unified perioperative management. Complications, nutritional status, changes in biochemical indicators, and tumor recurrence and metastasis were evaluated postoperatively.

The overall incidence of postoperative complications was significantly higher in the abdominal obesity group than in the non-abdominal obesity group (P < 0.05). The pulmonary infection on postoperative day (POD) 3 (P = 0.038), anastomotic leakage on POD 7 (P = 0.042), and moderate-to-severe complications (Clavien-Dindo class III, P = 0.03) were significantly different. With respect to biochemical indicators, the white blood cell count, neutrophil percentage, and C-reactive protein level in the abdominal obesity group continuously increased after surgery (P < 0.05); the albumin level on POD 1 was even lower (P = 0.024). Regarding tumor markers, carcinoembryonic antigen (P = 0.039) and carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (P = 0.048) levels were significantly higher in the abdominal obesity group at 3 months after surgery, and local recurrence rates were higher than those in the non-abdominal obesity group at 30 days and 3 months after surgery (P < 0.05). Abdominal obesity was an independent risk factor for postoperative complications (odds ratio: 3.843, P = 0.001), overall survival [hazard ratio (HR): 1.937, P = 0.011], and disease-free survival (HR: 1.769, P = 0.018).

Visceral obesity significantly increases the risk of postoperative complications in elderly patients with CRC and may adversely affect short-term tumor prognosis. Preoperative risk identification and interventions for abdominal obesity should be strengthened to improve perioperative safety and postoperative rehabilitation quality.

Core Tip: This study highlights the critical impact of visceral obesity on postoperative complications and short-term oncological outcomes in elderly patients undergoing colorectal cancer surgery. Patients with elevated visceral fat area showed higher risks of infection, anastomotic leakage, inflammatory response, and tumor recurrence. Visceral obesity was also identified as an independent predictor of overall and disease-free survival. These findings underscore the importance of preoperative risk stratification and targeted perioperative interventions for improving outcomes in this high-risk population.

- Citation: Zhou J, Wang BP, Su RN, Zhang S, Gao YW. Impact of visceral obesity on postoperative complications and oncological outcomes in elderly patients with colorectal cancer. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2026; 18(1): 109735

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v18/i1/109735.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v18.i1.109735

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common malignant tumor globally and the second leading cause of cancer-related mortality, particularly in the elderly population[1]. In China, aging demographics and changing lifestyles have contributed to the rising incidence of CRC among older adults.

With advancements in medical technology and the expansion of screening coverage, an increasing number of elderly patients can now undergo radical surgeries. However, the high incidence of postoperative complications and the heterogeneity of the long-term prognosis of tumors remain the main constraints on the effectiveness of clinical treatment[2]. At the same time, as a metabolic abnormal phenotype, visceral obesity has attracted extensive attention in recent years for its role in tumor prognosis[3].

Compared to the traditional body mass index (BMI), visceral obesity can reflect the deposition state of visceral fat more accurately. As an active endocrine organ, the latter can secrete a variety of pro-inflammatory factors, including tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin-6 (IL-6), adipokines, leptin, adiponectin and chemokines, and is involved in the proliferation of tumor cells, angiogenesis, immune escape and microenvironment remodeling[4,5]. Visceral obesity in elderly CRC patients with CRC may exacerbate perioperative risks through multiple mechanisms. Abundant visceral fat makes abdominal surgery more difficult, prolongs the operation time, and increases the risk of hemorrhage and complications related to anastomosis[6]. By contrast, adipose tissue-mediated chronic low-grade inflammation inhibits the immune system, delays postoperative recovery, and promotes micrometastasis, leading to an increased risk of tumor recurrence and metastasis[7]. Multiple cohort studies have shown that the incidence of postoperative complications is significantly increased and the 5-year overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival (DFS) rates are significantly decreased in CRC patients with a high visceral fat area (VFA), suggesting that visceral obesity is an important predictor of tumor outcomes[8]. Although some studies have explored the relationship between obesity and the prognosis of CRC, they have mostly focused on the overall population and lack special analysis of elderly patients. However, this popu

A total of 150 elderly patients with CRC at the Inner Mongolia Medical University and Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region People’s Hospital (a tertiary care center) from January 2021 to June 2024 were retrospectively analyzed in this study. All patients were confirmed to have colorectal adenocarcinomas based on postoperative pathology. Patients were divided into the abdominal (VFA ≥ 100.00 cm2, n = 80) and non-abdominal (VFA < 100.00 cm2, n = 70) obesity groups according to the intra-abdominal VFA measured by preoperative computed tomography (CT). The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Aged ≥ 65 years; (2) Had primary colorectal adenocarcinoma, as confirmed by postoperative pathology; (3) Underwent standard radical surgery (D3 dissection or total mesorectal excision); (4) Completed abdominal computed tomography (CT) examination within 3 months preoperatively; (5) Had measurable VFA; and (6) Had complete records of postoperative complications, with a follow-up duration of ≥ 12 months. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Patients who received chemoradiotherapy before surgery (n = 12); (2) Patients with severe underlying diseases, such as cardiac dysfunction with New York Heart Association grade ≥ III, Child-Pugh C cirrhosis, and end-stage renal disease

| Factor | Abdominal obesity group (n = 80) | Non-abdominal obesity group (n = 70) | χ2/t | P value |

| Age (years) | 72.63 ± 5.32 | 71.91 ± 5.58 | 0.788 | 0.432 |

| Male | 52 (65.00) | 45 (64.29) | 0.005 | 0.943 |

| Tumor site | ||||

| Carcinoma of colon | 45 (56.25) | 38 (54.29) | 0.057 | 0.811 |

| Rectal cancer | 35 (43.75) | 32 (45.71) | ||

| TNM stage I-II | 34 (42.50) | 29 (41.43) | 0.018 | 0.893 |

| TNM stage III | 46 (57.50) | 41 (58.57) | ||

| Combined hypertension | 38 (47.50) | 32 (45.71) | 0.038 | 0.845 |

| Combined diabetes | 22 (27.50) | 18 (25.71) | 0.05 | 0.824 |

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region People’s Hospital. Retrospective data usage complied with the institutional guidelines, and the requirement for informed consent was waived owing to the anonymized nature of the data analysis.

Therapeutic methods: Both groups of patients underwent standardized radical surgery for CRC performed by the same medical team to ensure operational consistency. Surgery included total mesorectal excision and D3 lymph node dissection, both of which were performed laparoscopically. The surgical equipment used was the Einstein Vision 3D laparoscopic system manufactured by Aesculap GmbH, Germany, which has high-definition stereoscopic vision to help accurately identify tumor boundaries and lymph node structures during surgery, thereby improving the precision and safety of the operation. Intraoperatively, the GEN11 ultrasonic high-frequency surgical integrated system (Johnson & Johnson) was used for vascular closure and tissue cutting, thus effectively reducing bleeding and thermal injury. All patients underwent intestinal tract preparation before surgery. Sterile conditions were maintained intraoperatively. An abdominal drainage tube was placed after surgery. The timing of extraction was determined based on the drainage volume and nature within 3-5 days after surgery. After surgery, all patients received the same perioperative mana

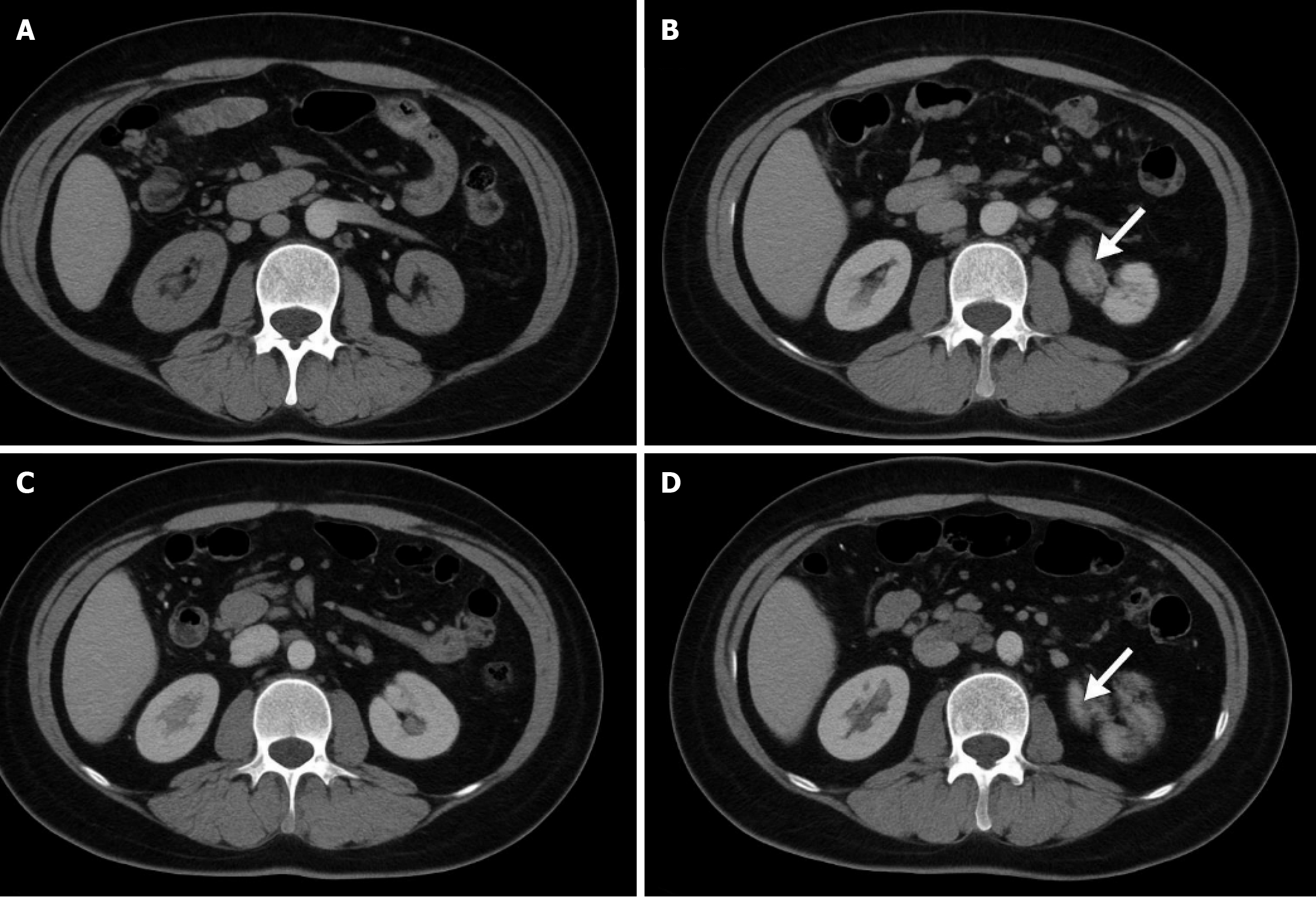

Detection methods: (1) VFA: GE Revolution CT was used to scan the horizontal axis of the navel (layer thickness, 1.25 mm). The fat area in the peritoneum was delineated using the Mimics Innovation Suite software (Version 21.0, Materialize). The HU value was set in the range of -190 to -30, and the VFA (cm2) was automatically calculated. Inde

All test results were recorded by a specially assigned person and crosschecked by two people. The data were uniformly entered into an electronic database. All operations were performed in strict compliance with the Clinical Laboratory Regulations (CLSI Standards) and hospital operating procedures to ensure objectivity and traceability of the data.

Outcome indicators: (1) Monitoring of postoperative complications: Complications were assessed according to the Clavien-Dindo classification, which was divided into grades I and V. The observation time points were 1, 2, 3, and 6 days after surgery, and before hospital discharge, which were cross-checked and evaluated by two senior attending physicians. Monitoring contents included pulmonary infection (body temperature > 38.0 °C and WBC count > 10.00 × 109/L ac

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 26.0. Measurement data were expressed as mean ± SD, enumeration data were expressed as n (%), and intra-group comparisons were performed using t-test and χ2 test. An independent sample t test or analysis of variance was used for comparisons between groups. Non-normally distributed data were expressed as medians (quartiles) [M (P25, P75)], and inter-group comparisons were made using the Mann-Whitney U test. The Kaplan-Meier survival curve was constructed using the time of the first occurrence of postoperative complications as the endpoint variable, and the difference in the cumulative incidence of postoperative complications between the abdominal and non-abdominal obesity groups was compared using the log-rank test. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to analyze the independent factors influencing the postoperative complications of abdominal obesity. Whether there were complications after operation (0 = no, 1 = yes) was taken as the dependent variable, and possible relevant clinical factors such as sex, age, BMI, abdominal obesity (waist circumference ≥ 90.00 cm for men and ≥ 85.00 cm for women) and combined basic diseases were included as the independent variables to screen the factors with statistical significance. At the same time, the Cox proportional hazard regression model was used to assess the impact of abdominal obesity on the OS and DFS of patients. With the follow-up time as the time variable and death or tumor recurrence as the endpoint event, the covariates of abdominal obesity, surgery, pathological stage, and whether or not to receive adjuvant treatment were included, and the hazard ratio (HR) and its 95% confidence interval were calculated. All statistical tests were performed bilaterally, and P < 0.05 indicated that the difference was statistically significant.

The overall incidence of postoperative complications was significantly higher in the abdominal obesity group than in the non-abdominal obesity group. The pulmonary infection on POD 3 (P = 0.038), anastomotic leakage on POD 7 (P = 0.042), and moderate-to-severe complications (Clavien-Dindo class III, P = 0.03) were significantly different (Table 2).

| Complications | Time point | Abdominal obesity group (n = 80) | Non-abdominal obesity group (n = 70) | χ2/t | P value |

| Pulmonary infection | Day 1 | 10 (12.50) | 4 (5.71) | 2.031 | 0.154 |

| Day 3 | 16 (20.00) | 6 (8.57) | 4.319 | 0.038 | |

| Incision infection | Day 3 | 7 (8.75) | 3 (4.29) | 1.132 | 0.287 |

| Urinary system infection | Day 3 | 6 (7.50) | 2 (2.86) | 1.392 | 0.238 |

| Intestinal obstruction | Day 7 | 7 (8.75) | 3 (4.29) | 1.132 | 0.287 |

| Anastomotic leakage | Day 7 | 8 (10.00) | 2 (2.86) | 4.121 | 0.042 |

| Postoperative haemorrhage | Before discharge | 5 (6.25) | 1 (1.43) | 2.143 | 0.143 |

| Deep vein thrombosis | Before discharge | 4 (5.00) | 0 (0.00) | 3.677 | 0.055 |

| Clavien-Dindo class ≥ III | Before discharge | 15 (18.75) | 5 (7.14) | 4.726 | 0.03 |

The WBC count (1 day before surgery, P = 0.034; POD 1, P = 0.015; POD 3, P = 0.03; POD 7, P = 0.01), NEUT% (1 day before surgery, P = 0.031; POD 1, P = 0.037; POD 3, P = 0.013; POD 7, P = 0.018), and CRP level (1 day before surgery, P = 0.048; POD 1, P = 0.015; POD 3, P = 0.022; POD 7, P = 0.016) in the abdominal obesity group continuously increased after surgery. The ALB level on POD 1 was even lower (P = 0.024). The two groups exhibited no significant difference in TP level at any time point (P > 0.05) (Table 3).

| Time point | Abdominal obesity group (n = 80) | Non-abdominal obesity group (n = 70) | χ2/t | P value |

| WBC count (× 109/L) | ||||

| 1 day before surgery | 7.45 ± 1.25 | 6.80 ± 1.10 | 2.136 | 0.034 |

| Day 1 | 10.24 ± 2.43 | 9.02 ± 1.98 | 2.463 | 0.015 |

| Day 3 | 9.90 ± 2.10 | 8.60 ± 1.85 | 2.184 | 0.03 |

| Day 7 | 9.05 ± 1.85 | 7.80 ± 1.50 | 2.632 | 0.01 |

| NEUT% | ||||

| 1 day before surgery | 63.50 ± 8.40 | 60.75 ± 7.90 | 2.182 | 0.031 |

| Day 1 | 72.45 ± 9.50 | 68.60 ± 8.30 | 2.104 | 0.037 |

| Day 3 | 69.80 ± 8.30 | 65.30 ± 7.00 | 2.545 | 0.013 |

| Day 7 | 68.20 ± 7.80 | 64.10 ± 6.90 | 2.391 | 0.018 |

| CRP (mg/L) | ||||

| 1 day before surgery | 5.35 ± 1.85 | 4.90 ± 1.20 | 1.983 | 0.048 |

| Day 1 | 21.50 ± 8.75 | 18.80 ± 7.60 | 2.465 | 0.015 |

| Day 3 | 16.75 ± 6.10 | 14.90 ± 5.30 | 2.305 | 0.022 |

| Day 7 | 11.25 ± 4.90 | 9.80 ± 4.20 | 2.438 | 0.016 |

| ALB (g/L) | ||||

| 1 day before surgery | 38.75 ± 5.40 | 40.00 ± 4.20 | 1.621 | 0.107 |

| Day 1 | 31.50 ± 5.30 | 33.20 ± 4.70 | 2.264 | 0.024 |

| Day 3 | 34.00 ± 4.80 | 35.20 ± 4.30 | 1.847 | 0.067 |

| Day 7 | 36.50 ± 4.00 | 37.30 ± 3.80 | 1.472 | 0.142 |

| TP (g/L) | ||||

| 1 day before surgery | 60.00 ± 5.10 | 61.30 ± 4.60 | 1.174 | 0.242 |

| Day 1 | 57.20 ± 5.80 | 58.10 ± 5.30 | 1.132 | 0.258 |

| Day 3 | 58.00 ± 6.00 | 59.50 ± 5.80 | 1.059 | 0.291 |

| Day 7 | 59.20 ± 5.60 | 60.00 ± 5.40 | 1.312 | 0.191 |

The levels of CEA (3 months after surgery, P = 0.039) and CA19-9 (1 day before surgery, P = 0.034; 3 months after surgery, P = 0.048) were significantly higher in the abdominal obesity group (Table 4).

| Time point | Abdominal obesity group (n = 80) | Non-abdominal obesity group (n = 70) | χ2/t | P value |

| CEA (ng/mL) | ||||

| 1 day before surgery | 3.90 ± 1.15 | 3.70 ± 1.00 | 1.001 | 0.318 |

| Day 7 | 5.80 ± 2.30 | 5.20 ± 2.00 | 1.402 | 0.162 |

| Month 3 | 6.10 ± 2.40 | 5.30 ± 2.10 | 2.092 | 0.039 |

| CA19-9 (U/mL) | ||||

| 1 day before surgery | 32.50 ± 5.80 | 30.20 ± 4.50 | 2.136 | 0.034 |

| Day 7 | 35.00 ± 6.20 | 33.10 ± 5.70 | 1.21 | 0.227 |

| Month 3 | 37.00 ± 6.80 | 34.60 ± 5.40 | 1.983 | 0.048 |

The local recurrence rates were higher than those in the non-abdominal obesity group 30 days (P = 0.046) and three months (P = 0.037) after surgery (P < 0.05). There was no significant difference between the two groups in terms of distant metastasis or recovery of the operative area (P > 0.05; Table 5).

| Time point | Abdominal obesity group (n = 80) | Non-abdominal obesity group (n = 70) | χ2/t | P value |

| Postoperative day 30 | Local recurrence: 15 (18.75) | Local recurrence: 7 (10.00) | 3.984 | 0.046 |

| Distant metastasis: 6 (7.50) | Distant metastasis: 4 (5.71) | 1.123 | 0.29 | |

| Poor recovery in the operation area: 4 (5.00) | Poor recovery in the operation area: 3 (4.29) | 0.978 | 0.323 | |

| Good recovery was achieved in the operation area: 55 (68.75) | Good recovery was achieved in the operation area: 56 (80.00) | 2.586 | 0.108 | |

| 3 months after surgery | Local recurrence: 18 (22.50) | Local recurrence: 9 (12.86) | 4.351 | 0.037 |

| Distant metastasis: 7 (8.75) | Distant metastasis: 5 (7.14) | 0.743 | 0.389 | |

| Poor recovery in the operation area: 5 (6.25) | Poor recovery in the operation area: 3 (4.29) | 1.169 | 0.28 | |

| Good recovery was achieved in the operation area: 50 (62.50) | Good recovery was achieved in the operation area: 53 (75.71) | 2.833 | 0.092 |

Dietary intake (day 7, P = 0.043) and body weight change (P = 0.029) in the abdominal obesity group were significantly lower than in the non-abdominal obesity group. Regarding the recovery of gastrointestinal function, patients in the abdominal obesity group had longer defecation times (day 3, P = 0.038; day 7, P = 0.042). The PG-SGA showed that the nutritional status of the abdominal obesity group was poor (week 1, P = 0.032; week 4, P = 0.021) (Table 6).

| Time point | Abdominal obesity group | Non-abdominal obesity group | χ2/t | P value |

| Dietary intake and body weight change (kcal) | ||||

| Day 1 | 1200.00 ± 150.00 | 1300.00 ± 180.00 | 1.607 | 0.115 |

| Day 7 | 1300.00 ± 160.00 | 1400.00 ± 170.00 | 2.026 | 0.043 |

| Body weight change (kg) | -2.80 ± 0.90 | -2.20 ± 0.80 | 2.213 | 0.029 |

| Gastrointestinal function recovery (exhaust and defecation time) (hour) | ||||

| Day 3 | 48.00 ± 12.00 | 42.00 ± 10.00 | 2.078 | 0.038 |

| Day 7 | 72.00 ± 14.00 | 65.00 ± 13.00 | 2.075 | 0.042 |

| PG-SGA scale | ||||

| Week 1 | 8.30 ± 2.10 | 7.20 ± 1.90 | 2.136 | 0.032 |

| Week 4 | 9.10 ± 2.30 | 7.80 ± 2.10 | 2.369 | 0.021 |

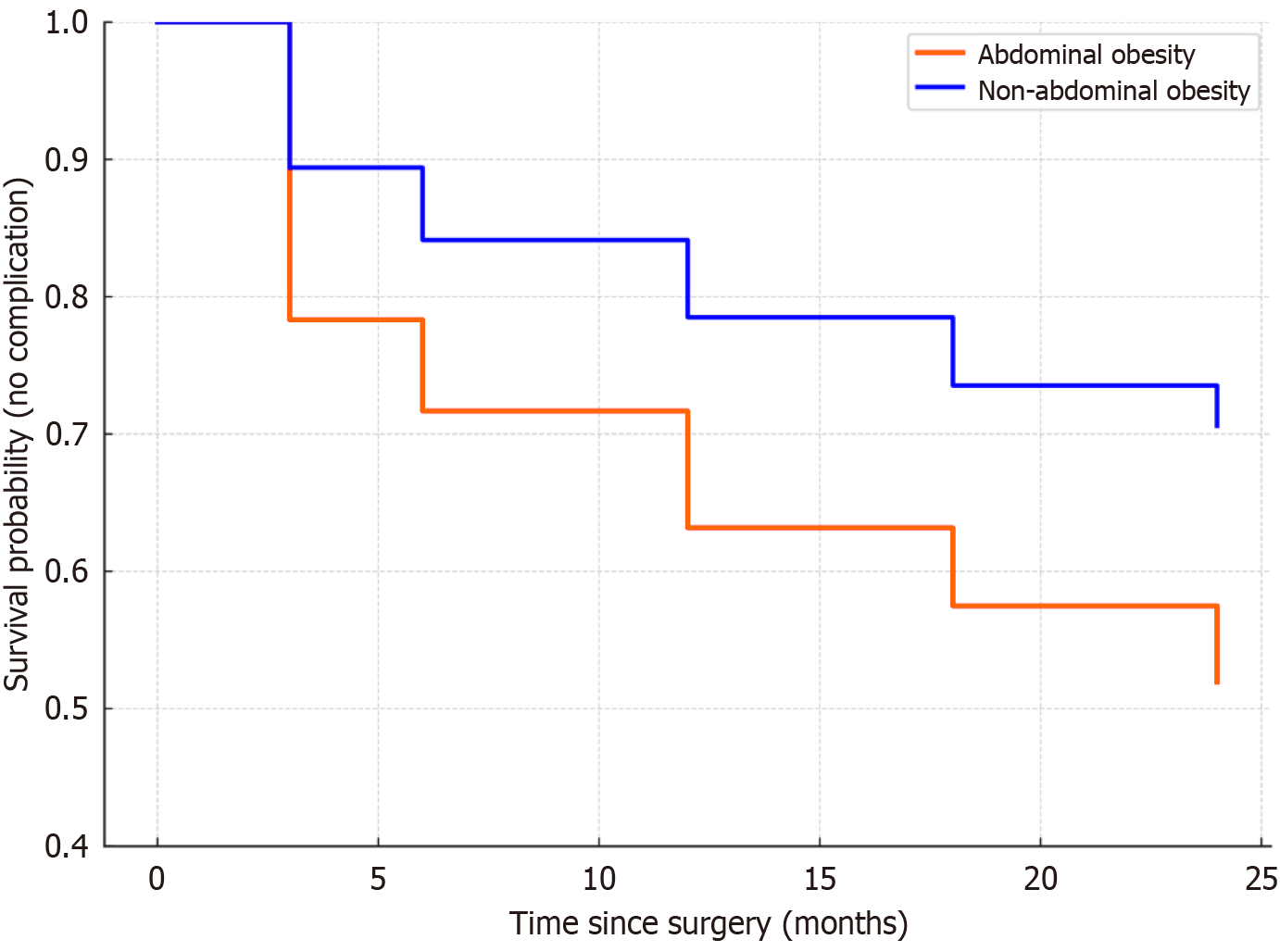

The survival curve of the abdominal obesity group showed a significantly steeper decline over the 24-month follow-up period than the non-abdominal obesity group, indicating that the time to the first postoperative complication was shorter in patients with abdominal obesity. The abdominal obesity group demonstrated a notably higher risk of complications within the first 3-6 months, and a sustained elevated risk up to 18 months postoperatively. The log-rank test indicated a significant difference in the cumulative incidence of postoperative complications between the abdominal obesity group and the non-abdominal obesity group (χ2 = 5.817, P = 0.016; Figure 2).

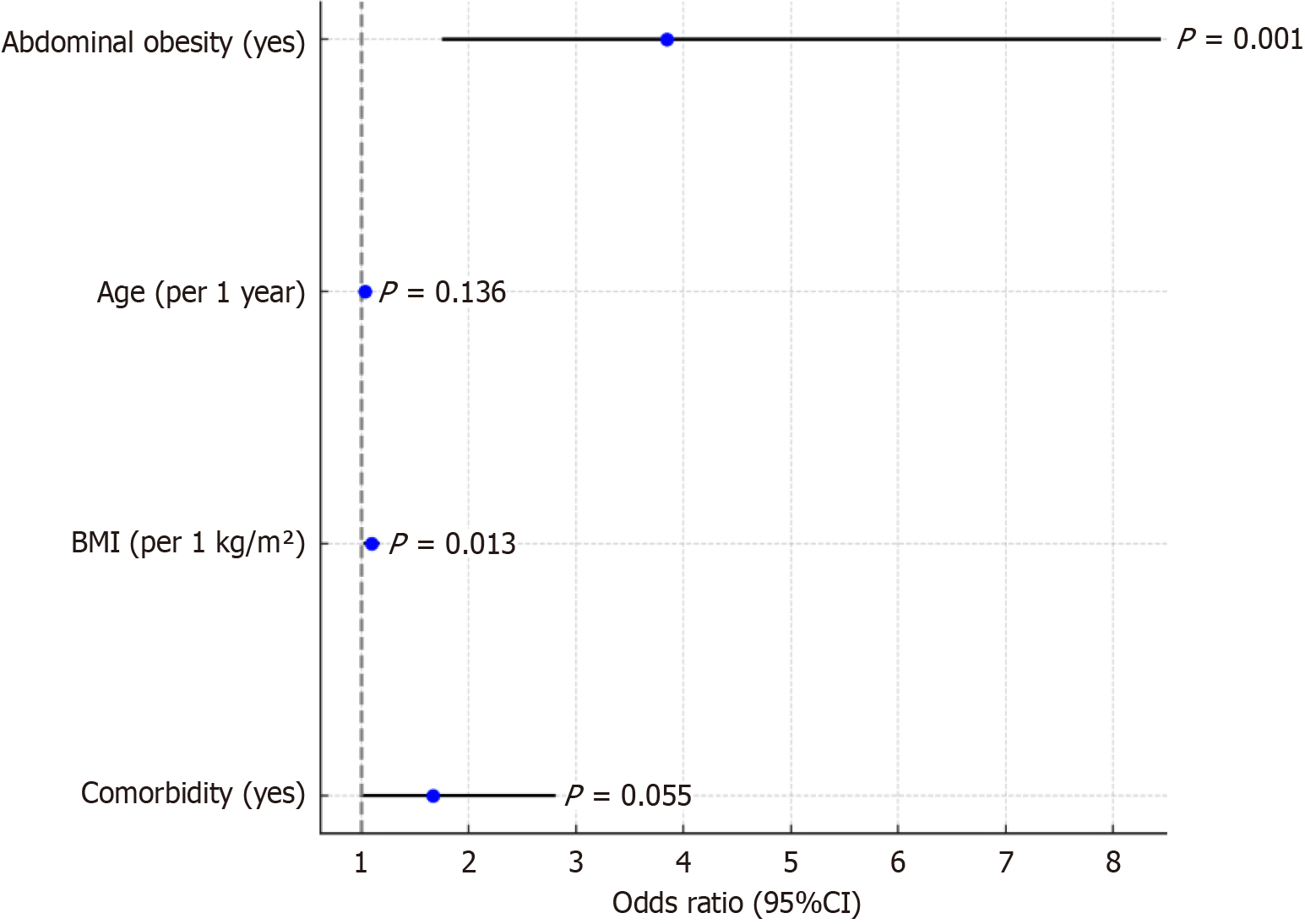

Logistic regression analysis showed that abdominal obesity (OR: 3.843, P = 0.001) and increased BMI (OR: 1.093, P = 0.013) were independent risk factors for postoperative complications and that the combination of basic diseases was nearly significant (P = 0.055; Table 7 and Figure 3).

| Factor | β | SE | Wald χ2 | P value | OR | 95%CI |

| Constant term | -0.564 | 0.245 | 5.178 | 0.023 | 0.569 | 0.332-0.979 |

| Abdominal obesity (yes) | 1.345 | 0.412 | 10.512 | 0.001 | 3.843 | 1.750-8.451 |

| Age (1 year for each additional) | 0.032 | 0.021 | 2.227 | 0.136 | 1.033 | 0.991-1.077 |

| BMI (per 1 kg/m2 increase) | 0.089 | 0.036 | 6.165 | 0.013 | 1.093 | 1.018-1.174 |

| Combined basic disease (yes) | 0.512 | 0.265 | 3.693 | 0.055 | 1.668 | 0.986-2.808 |

The results of the Cox regression analysis showed that abdominal obesity was an independent risk factor for OS (HR: 1.937, P = 0.011) and DFS (HR: 1.769, P = 0.018). Pathological staging and adjuvant treatment also significantly affected prognosis (Table 8).

| Factor | β | P value | HR | 95%CI |

| OS | ||||

| Constant term | -1.14 | 0.004 | 0.32 | - |

| Abdominal obesity (yes) | 0.661 | 0.011 | 1.937 | 1.158-3.243 |

| Pathological staging (III) | 1.079 | 0.001 | 2.941 | 1.606-5.388 |

| Adjuvant treatment (no) | 0.794 | 0.007 | 2.212 | 1.237-3.954 |

| DFS | ||||

| Constant term | -0.921 | 0.012 | 0.398 | - |

| Abdominal obesity (yes) | 0.57 | 0.018 | 1.769 | 1.102-2.842 |

| Pathological staging (III) | 1.147 | < 0.001 | 3.15 | 1.778-5.582 |

In this study, visceral obesity was taken as the breakthrough point to explore its impact on postoperative complications and the long-term prognosis of tumors in elderly patients with CRC. The results showed that the abdominal obesity group had adverse trends in the incidence of postoperative complications, biochemical inflammation, deterioration of immune nutritional status, and a continuous increase in tumor markers, further confirming the adverse effects of visceral obesity as a potentially high-risk metabolic phenotype in elderly patients with CRC. The incidence of postoperative complications, such as pulmonary infection, incision infection, and anastomotic leakage, was significantly higher in the abdominal obesity group than in the non-abdominal obesity group. This condition is closely related to factors such as a narrow field of vision during abdominal surgery, poor blood supply to adipose tissues, and a persistent inflammatory state caused by visceral obesity[9]. Consistent with previous studies, the more visceral fat accumulated, the more difficult the operation and the higher the risk of anastomosis tension and ischemia, thus increasing the probability of fistula formation and infection[10]. The high-definition laparoscopy and energy platform adopted in this study improved the accuracy during surgery; however, it was still difficult to completely offset the structural and anatomical challenges posed by abdominal obesity[11]. In terms of inflammation and the immune response, the postoperative CRP and NEUT% values in the abdominal obesity group were consistently higher than those in the non-abdominal obesity group, indi

This study clearly demonstrates that visceral obesity significantly increases the risk of perioperative complications. The main reason is that a large amount of visceral fat deposition not only blocks the anatomical signs and increases the difficulty and operation time of the operation, but also affects the visibility of blood vessels and intestinal tubes, thus reducing the degree of surgical refinement and increasing the tension of the anastomosis, thereby improving the risk of anastomotic leakage[19]. Simultaneously, patients with visceral obesity usually have high intra-abdominal pressure and difficulty in maintaining pneumoperitoneum during surgery, further increasing the risk of bleeding and postoperative recovery time. Visceral adipose tissues are prone to mechanical damage during surgery, releasing a large amount of adipocyte debris and inflammatory factors, resulting in the aggravation of postoperative abdominal inflammation[20]. From the perspective of immune inflammation, the inflammatory indicators of patients with visceral obesity after surgery are significantly increased, and recovery is slow, revealing the existence of a “chronic inflammatory background”. Studies have shown that visceral adipose tissue is an active endocrine organ that can continuously secrete pro-inflammatory factors (such as TNF-α and IL-6), chemokines (such as monocyte chemoattractant protein-1) and adipokines (such as leptin and resistin) to form a “low-grade chronic inflammation”[21]. In this state, the acute inflammatory reaction caused by postoperative trauma cannot be stopped quickly, but may present a magnification effect owing to the high load of basic inflammation, leading to more common complications of postoperative infection and poor healing of patients. Leptin can promote angiogenesis and tumor cell proliferation, whereas adiponectin is decreased in obesity, resulting in impaired anti-inflammatory and antiproliferative effects. Collectively, these factors promote the growth and recurrence of postoperative micrometastases. In terms of tumor biological mechanisms, a key pathway by which visceral obesity affects tumor outcomes is the “metabolism-immunity-inflammation axis”[22]. Studies have shown that visceral fat activates tumor cell metabolism and enhances the anti-apoptotic ability through the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway. HIF-1α signal can promote the expression of hypoxia-inducible factor and accelerate angiogenesis. The JAK/STAT pathway activates the pro-inflammatory pathway and interferes with T cell-mediated immune surveillance[23]. In this study, we also observed that the CEA and CA19-9 decreased slowly in patients with visceral obesity after surgery, suggesting that the residual lesions had a stronger resistance to immune clearance, or there was “hidden survival” of tumor cells. In recent years, many transcriptome and metabolome studies have revealed that visceral obesity can promote the transformation of colorectal tumors into more aggressive molecular subtypes by altering the metabolite spectrum and immune cell infiltration patterns in the microenvironment of colorectal tumors. Compared with previous studies focusing on BMI or simple obesity, this study used VFA to measure the intra-abdominal fat area, which can more accurately assess the impact of visceral obesity on patients with tumors. The traditional BMI cannot distinguish between muscles and fat. Particularly in the elderly, the “hidden obesity” with normal BMI but actual existence of muscle deficiency and visceral fat accumulation cannot be ignored. The results of this study support that “VFA ≥ 100 cm2” is the cutoff value for the determination of visceral obesity, and this indicator shows good sensitivity and specificity in multiple prediction models. In the elderly population, the effect of visceral obesity is complex. On the one hand, the basal metabolic rate of the elderly is decreased, and adipose tissues are more inclined to visceral deposition; on the other hand, coinfection of immune aging and chronic diseases (such as diabetes and hypertension) further weakens its anti-tumor ability, thus amplifying the negative effects of visceral obesity[24]. This also indicates that visceral obesity should be considered as a core consideration in the con

In this study, we quantified the impact of visceral obesity (with VFA as the index) on postoperative complications and long-term prognosis of CRC in the elderly and identified it as an important independent risk factor with significant cli

The limitation lies in its single-center retrospective design with a limited sample size. Covariates such as myopathy were not included, and future studies should adopt multicenter prospective designs to explore the molecular mechanisms through metabolomics and immunohistochemistry. Additionally, an investigation into the potential of fat-reduction interventions to improve postoperative outcomes is warranted.

In summary, this study has clearly pointed out that visceral obesity is an independent factor contributing to the increase in postoperative complications and poor long-term prognosis of elderly patients with CRC. Therefore, implementing prehabilitation programs targeting visceral fat reduction - such as 12-week preoperative regimens combining high-protein nutrition support (1.5 g/kg/day) and moderate-intensity aerobic exercise (150 minutes/week) - may improve surgical outcomes. It systematically affects tumor treatment outcomes through multiple mechanisms, including increased technical difficulty in surgery, postoperative inflammation amplification, activation of tumor pathways by metabolic abnormalities, and immune escape. Therefore, in clinical practice, visceral obesity should be considered an important index for preoperative evaluation. Targeted nutrition, exercise intervention, and perioperative management are expected to improve the overall treatment benefit for elderly patients with CRC. Future economic evaluations should assess the cost-effectiveness of routine VFA measurements using computed tomography. Preliminary modeling suggests that this approach may reduce costs when targeting high-risk populations by reducing complication-related expenditures.

| 1. | Molenaar CJL, Minnella EM, Coca-Martinez M, Ten Cate DWG, Regis M, Awasthi R, Martínez-Palli G, López-Baamonde M, Sebio-Garcia R, Feo CV, van Rooijen SJ, Schreinemakers JMJ, Bojesen RD, Gögenur I, van den Heuvel ER, Carli F, Slooter GD; PREHAB Study Group. Effect of Multimodal Prehabilitation on Reducing Postoperative Complications and Enhancing Functional Capacity Following Colorectal Cancer Surgery: The PREHAB Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Surg. 2023;158:572-581. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 201] [Cited by in RCA: 301] [Article Influence: 100.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Zhang H, Zhang H, Wang W, Ye Y. Effect of preoperative frailty on postoperative infectious complications and prognosis in patients with colorectal cancer: a propensity score matching study. World J Surg Oncol. 2024;22:154. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Li Z, Yan G, Liu M, Li Y, Liu L, You R, Cheng X, Zhang C, Li Q, Jiang Z, Ruan J, Ding Y, Li W, You D, Liu Z. Association of Perioperative Skeletal Muscle Index Change With Outcome in Colorectal Cancer Patients. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2024;15:2519-2535. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Wang J, Chen Y, He J, Yin C, Xie M. Sarcopenia Predicts Postoperative Complications and Survival of Colorectal Cancer Patients Undergoing Radical Surgery. Br J Hosp Med (Lond). 2024;85:1-17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Chen Q, Chen J, Deng Y, Bi X, Zhao J, Zhou J, Huang Z, Cai J, Xing B, Li Y, Li K, Zhao H. Personalized prediction of postoperative complication and survival among Colorectal Liver Metastases Patients Receiving Simultaneous Resection using machine learning approaches: A multi-center study. Cancer Lett. 2024;593:216967. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Steinbrück I, Ebigbo A, Kuellmer A, Schmidt A, Kouladouros K, Brand M, Koenen T, Rempel V, Wannhoff A, Faiss S, Pech O, Möschler O, Dumoulin FL, Kirstein MM, von Hahn T, Allescher HD, Gölder SK, Götz M, Hollerbach S, Lewerenz B, Meining A, Messmann H, Rösch T, Allgaier HP. Cold Versus Hot Snare Endoscopic Resection of Large Nonpedunculated Colorectal Polyps: Randomized Controlled German CHRONICLE Trial. Gastroenterology. 2024;167:764-777. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 18.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Høydahl Ø, Edna TH, Xanthoulis A, Lydersen S, Endreseth BH. Octogenarian patients with colon cancer - postoperative morbidity and mortality are the major challenges. BMC Cancer. 2022;22:302. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Hai ZX, Peng D, Li ZW, Liu F, Liu XR, Wang CY. The effect of lymph node ratio on the surgical outcomes in patients with colorectal cancer. Sci Rep. 2024;14:17689. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Matsubara D, Soga K, Ikeda J, Konishi T, Uozumi Y, Takeda R, Kanazawa H, Komatsu S, Shimomura K, Taniguchi F, Shioaki Y, Otsuji E. Laparoscopic Surgery for Elderly Colorectal Cancer Patients With High American Society of Anesthesiologists Scores. Anticancer Res. 2023;43:5637-5644. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Feng Y, Cheng XH, Xu M, Zhao R, Wan QY, Feng WH, Gan HT. CT-determined low skeletal muscle index predicts poor prognosis in patients with colorectal cancer. Cancer Med. 2024;13:e7328. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Cho HJ, Lee HS, Kang J. Varying clinical relevance of sarcopenia and myosteatosis according to age among patients with postoperative colorectal cancer. J Nutr Health Aging. 2024;28:100243. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kumamoto T, Takamizawa Y, Miyake M, Inoue M, Moritani K, Tsukamoto S, Eto K, Kanemitsu Y. Clinical utility of sarcopenia dynamics assessed by psoas muscle volume in patients with colorectal cancer. World J Surg. 2024;48:2098-2108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Liu XY, Li ZW, Zhang B, Liu F, Zhang W, Peng D. Effects of preoperative bicarbonate and lactate levels on short-term outcomes and prognosis in elderly patients with colorectal cancer. BMC Surg. 2023;23:127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Shang W, Yuan W, Liu R, Yan C, Fu M, Yang H, Chen J. Factors contributing to the mortality of elderly patients with colorectal cancer within a year after surgery. J Cancer Res Ther. 2022;18:503-508. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Ma YK, Qu L, Chen N, Chen Z, Li Y, Jiang ALM, Ismayi A, Zhao XL, Xu GP. Effect of multimodal opioid-sparing anesthesia on intestinal function and prognosis of elderly patients with hypertension after colorectal cancer surgery. BMC Surg. 2024;24:341. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Abe T, Matsuda T, Sawada R, Hasegawa H, Yamashita K, Kato T, Harada H, Urakawa N, Goto H, Kanaji S, Oshikiri T, Kakeji Y. Patients younger than 40 years with colorectal cancer have a similar prognosis to older patients. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2023;38:191. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Tian Y, Li R, Wang G, Xu K, Li H, He L. Prediction of postoperative infectious complications in elderly patients with colorectal cancer: a study based on improved machine learning. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2024;24:11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Chen WZ, Shen ZL, Zhang FM, Zhang XZ, Chen WH, Yan XL, Zhuang CL, Chen XL, Yu Z. Prognostic value of myosteatosis and sarcopenia for elderly patients with colorectal cancer: A large-scale double-center study. Surgery. 2022;172:1185-1193. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Jiang W, Xia Y, Liu Y, Cheng S, Wang W, Guan Z, Dou H, Zhang C, Wang H. Impact of Preoperative Neutrophil to Prealbumin Ratio Index (NPRI) on Short-Term Complications and Long-Term Prognosis in Patients Undergoing Laparoscopic Radical Surgery for Colorectal Cancer. Mediators Inflamm. 2024;2024:4465592. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Xue Y, Li S, Guo S, Kuang Y, Ke M, Liu X, Gong F, Li P, Jia B. Evaluation of the advantages of robotic versus laparoscopic surgery in elderly patients with colorectal cancer. BMC Geriatr. 2023;23:105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Wang L, Wu Y, Deng L, Tian X, Ma J. Construction and validation of a risk prediction model for postoperative ICU admission in patients with colorectal cancer: clinical prediction model study. BMC Anesthesiol. 2024;24:222. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kanehara R, Goto A, Watanabe T, Inoue K, Taguri M, Kobayashi S, Imai K, Saito E, Katanoda K, Iwasaki M, Ohashi K, Noda M, Higashi T. Association between diabetes and adjuvant chemotherapy implementation in patients with stage III colorectal cancer. J Diabetes Investig. 2022;13:1771-1778. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Shiraishi T, Tominaga T, Ono R, Noda K, Hashimoto S, Oishi K, Takamura Y, Nonaka T, Hisanaga M, Ishii M, Takeshita H, To K, Ishimaru K, Sawai T, Nagayasu T. Short- and Long-term Outcomes After Colonic Stent Insertion as a Bridge to Surgery in Elderly Colorectal Cancer Patients. Anticancer Res. 2024;44:1637-1643. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 24. | Fujimoto T, Tamura K, Nagayoshi K, Mizuuchi Y, Oh Y, Nara T, Matsumoto H, Horioka K, Shindo K, Nakata K, Ohuchida K, Nakamura M. Osteosarcopenia: the coexistence of sarcopenia and osteopenia is predictive of prognosis and postoperative complications after curative resection for colorectal cancer. Surg Today. 2025;55:78-89. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |