Published online Dec 15, 2025. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v17.i12.113661

Revised: September 18, 2025

Accepted: November 5, 2025

Published online: December 15, 2025

Processing time: 102 Days and 17 Hours

Primary gastrointestinal diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (PGI-DLBCL), the most prevalent extranodal non-Hodgkin lymphoma, poses significant diagnostic and therapeutic challenges due to its non-specific symptoms and poor prognosis.

To develop and validate a risk model for the early identification of PGI-DLBCL using Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection-Cox regression, with the aim of guiding clinical decision-making.

The clinical data of patients diagnosed with PGI-DLBCL at the Tumor Hospital Affiliated to Xinjiang Medical University were analyzed retrospectively from Jan

A total of 319 patients with PGI-DLBCL were included and divided into training (n = 223) and validation (n = 96) cohorts. The median age was 55 years, with 48.9% male and 51.1% female patients. Key clinical features included Eastern Coope

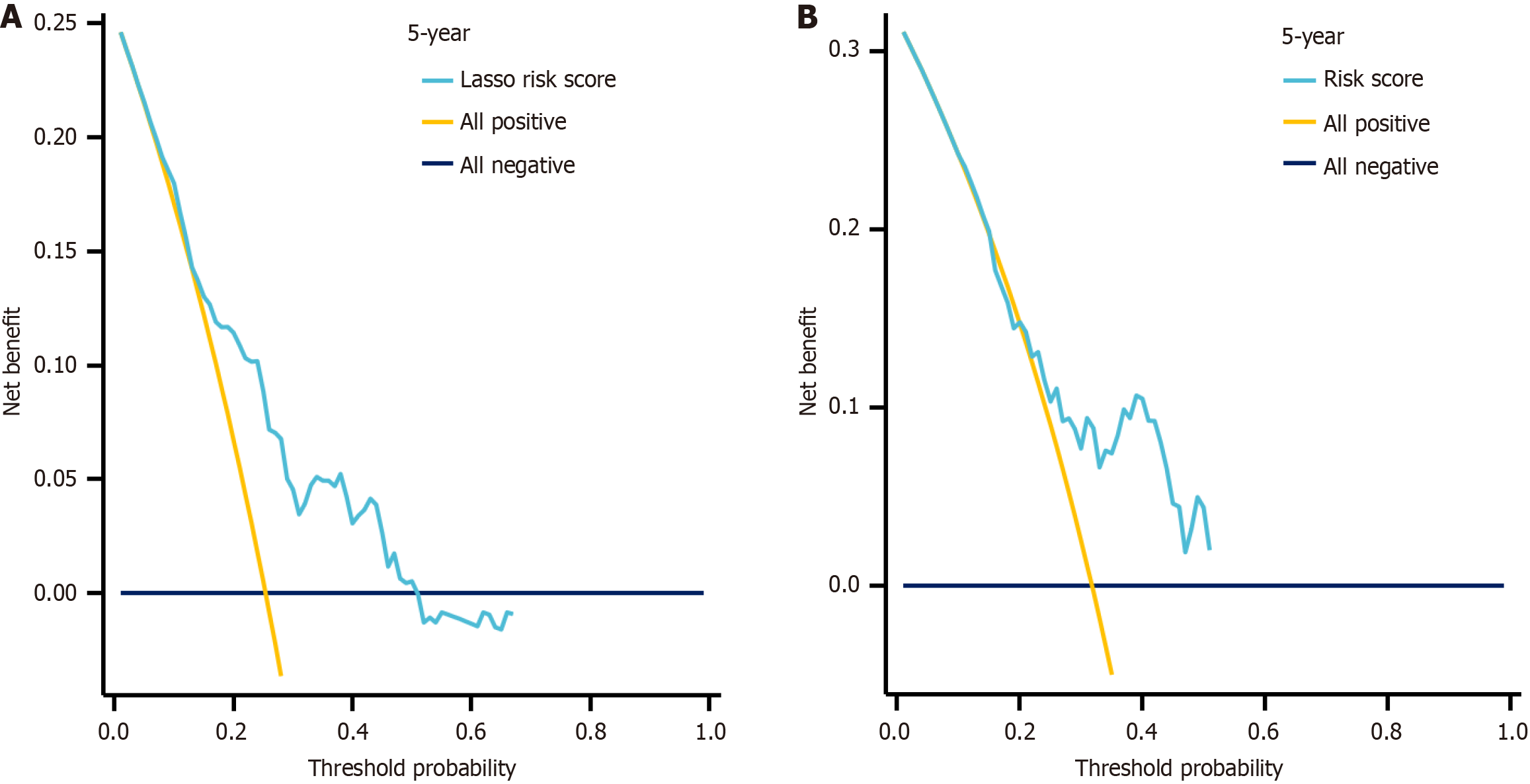

PGI-DLBCL in our cohort showed distinctive clinical features and a predominance of the non-germinal center B-cell-like subtype. Decision curve analysis confirmed the clinical applicability of our prognostic model. Although molecular biomarkers will be needed to improve predictive precision, our model offers a practical tool for early risk identification and individualized management in clinical practice.

Core Tip: Primary gastrointestinal diffuse large B-cell lymphoma predominantly affects elderly men over 60 years, with abdominal pain, distension, and significant weight loss as common initial symptoms. Lesions are primarily located in the gastric body, antrum, and colon, often presenting as ulcerative or raised masses on endoscopy. Key independent prognostic risk factors include age > 60 years, presence of B symptoms, and elevated serum lactate dehydrogenase > 250 U/L, which correlate with poor survival outcomes and necessitate early diagnosis and targeted therapy.

- Citation: Ma JJ, Zhang H, Wang CC, Ji WL, Zhao Y, Li XX. Clinical characteristics and prognostic analysis of three hundred and nineteen cases of primary gastrointestinal diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2025; 17(12): 113661

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v17/i12/113661.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v17.i12.113661

Primary gastrointestinal (PGI) diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) represents the most prevalent subtype of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) affecting the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Analysis of the Epstein-Barr virus-encoded RNA (EBER) database by Feng et al[1] revealed that PGI-DLBCL constitutes the majority of primary GI lymphomas, with gastric involvement occurring most frequently (53.3%), followed by the small intestine (26.3%) and colorectum (20.5%)[1].

As the most common extranodal NHL subtype globally, PGI-DLBCL comprises 10%-15% of all NHLs and 20%-40% of extranodal cases, with DLBCL being the predominant histological variant[2,3]. Within the Chinese population, this malignancy typically manifests in middle-aged to elderly men, with disease onset occurring around 55-57 years of age. However, regarding the Chinese population specifically, large-scale studies establishing the stomach as the most common site of involvement remain lacking. In a report involving 88 patients, the small intestine was identified as the most frequently affected site[4]. The disease pathogenesis involves multiple factors, including Helicobacter pylori infection, autoimmune conditions such as celiac disease, chronic inflammatory processes, and immunocompromised states[2,5].

The clinical presentation of PGI-DLBCL poses significant diagnostic challenges due to its nonspecific symptomatology. Patients commonly experience abdominal pain, bloating, unintentional weight loss, nausea, or GI bleeding-symptoms that overlap considerably with benign conditions such as gastric ulcers and enteritis, as well as other malignancies including tuberculosis and conventional GI cancers. This clinical ambiguity contributes to frequent misdiagnosis and diagnostic delays[6]. The submucosal origin of these tumors further complicates diagnosis, as conventional endoscopic biopsies often yield false-negative results. Consequently, most patients receive their diagnosis only after progression to advanced disease (Lugano stage III-IV), when therapeutic options become limited and prognosis deteriorates substantially[7]. Given these challenges, establishing an early risk stratification model based on readily available clinical parameters could facilitate timely identification of high-risk individuals and guide therapeutic decision-making.

To address this clinical need, we conducted a multicenter retrospective analysis combining least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) regression with Cox proportional hazards modeling to develop and validate a practical risk prediction tool for PGI-DLBCL. Our objective was to create an accessible, clinically relevant assessment instrument that could enhance early detection capabilities and support individualized patient management approaches for this uncommon but significant malignancy.

We enrolled patients with biopsy-confirmed DLBCL diagnosed between January 2010 and April 2022 where the GI tract was the primary disease site based on staging workup; and patients who required complete baseline data and adequate follow-up for survival analysis.

We excluded patients with secondary GI involvement from nodal disease, concurrent malignancies, transformed low-grade lymphomas, primary central nervous system lymphoma, human immunodeficiency virus-associated cases, post-transplant disorders, incomplete immunostaining preventing subtype classification, or loss to follow-up within 3 months without documented progression.

We gathered demographic information, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status performance status, and B symptoms (fever > 38 °C, night sweats, or > 10% weight loss within 6 months). Laboratory examinations included lactate dehydrogenase (LDH, elevated if > 250 U/L) and β2-microglobulin (β2-MG, elevated if > 2.2 mg/L). Disease staging followed the Lugano criteria, with bulky disease defined as > 5 cm. We calculated International Prognostic Index scores and grouped patients into low-risk (0-2) vs high-risk (3-5) categories.

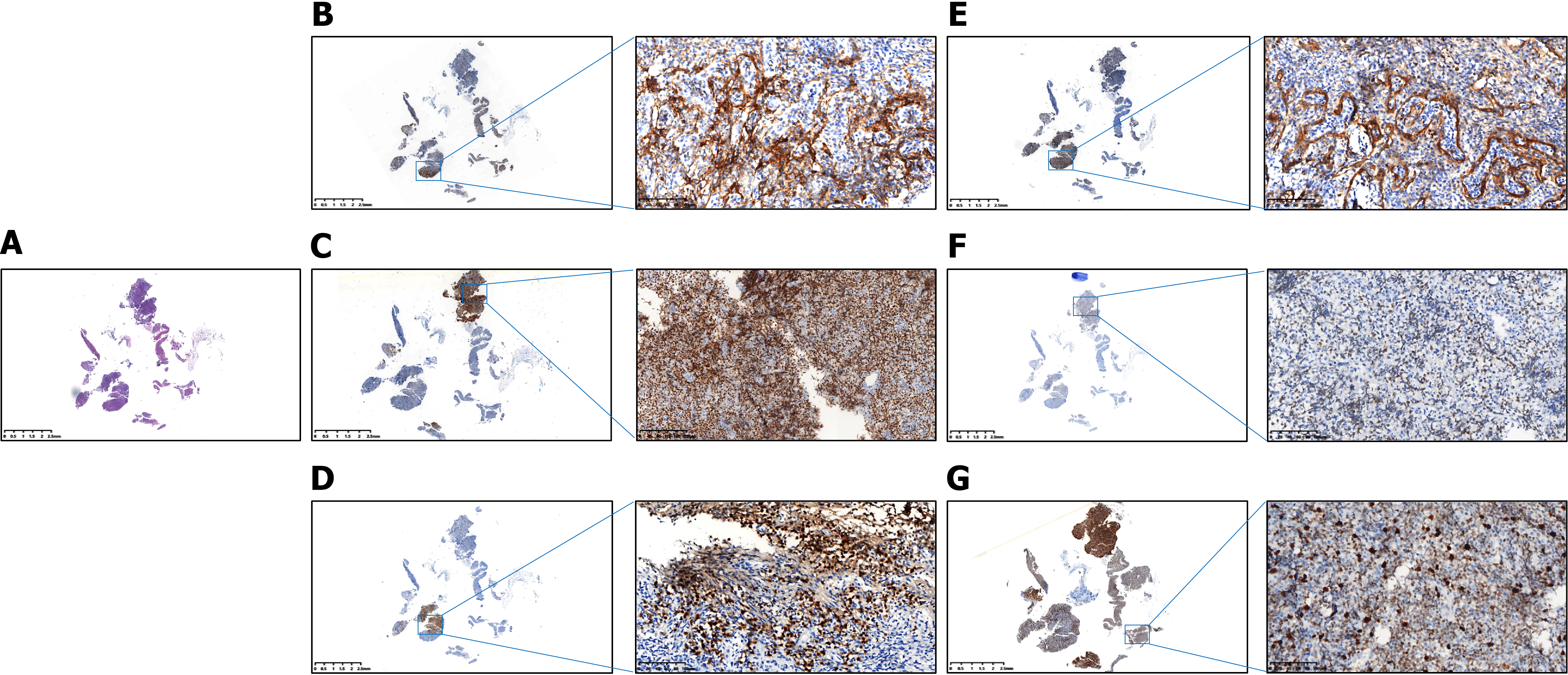

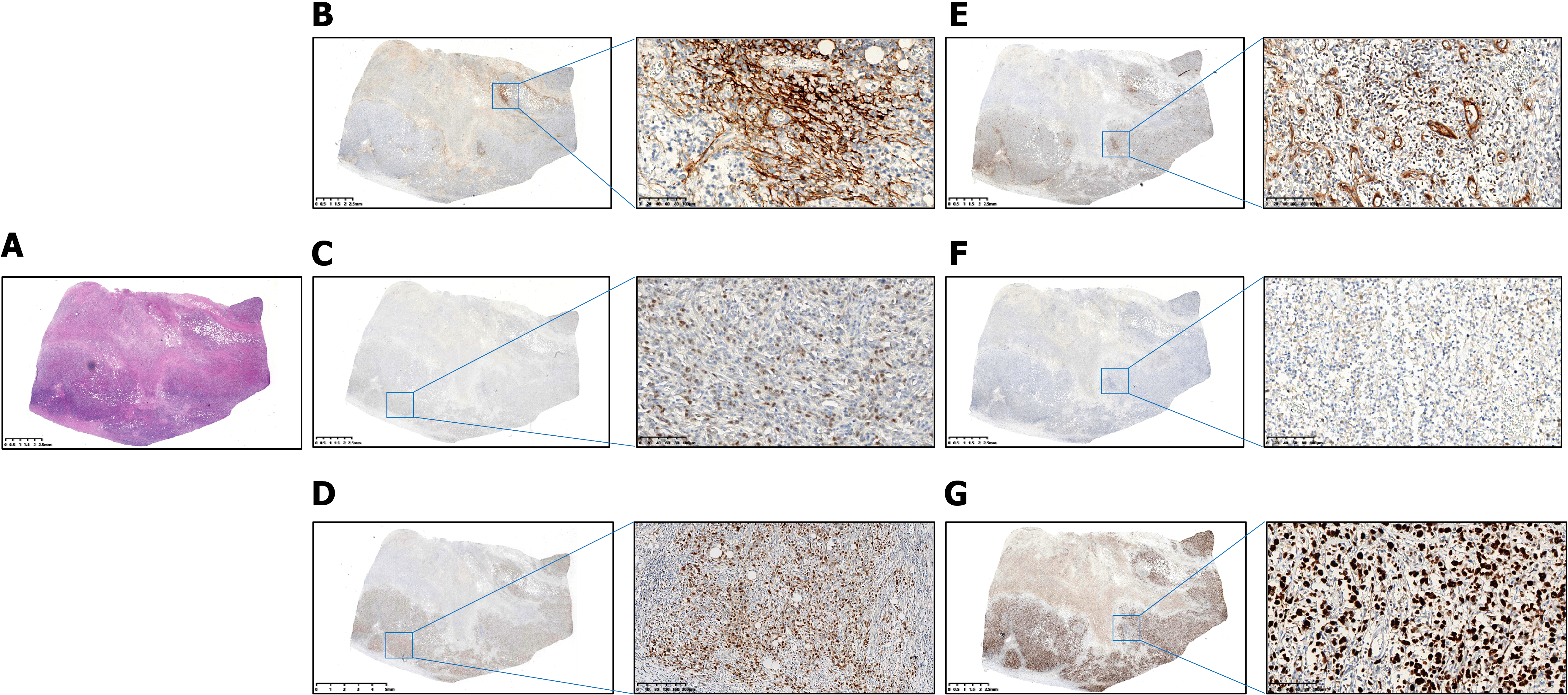

Tissues were obtained from endoscopic biopsies (6-8 fragments), surgical specimens, or core needle biopsies. We stained 4-μm sections for CD20, CD3, CD10, B-cell lymphoma (BCL)-6, multiple myeloma oncogene 1 (MUM-1), BCL-2, myelocytomatosis viral oncogene homolog (C-MYC), Ki-67, and CD5. Two pathologists independently reviewed all cases, with the Hans algorithm determining germinal center B-cell-like lymphoma (GCB) vs non-GCB subtypes. We set positivity cutoffs at CD10/BCL-6/MUM-1 ≥ 30%, BCL-2 ≥ 70%, C-MYC ≥ 50%, and Ki-67 ≥ 70%.

Patients received chemotherapy, surgery, combined therapy, or supportive care only. We assessed responses using the Lugano criteria after 3-4 cycles and at completion. Follow-up occurred every 3 months for 2 years, then every 6 months until year 5, and then annually. Data were obtained from clinic visits, hospital records, and phone calls in June 2022.

Using R software, we randomly split our 319 patients into the training (70%, n = 223) and validation (30%, n = 96) groups. LASSO Cox regression identified key prognostic factors while avoiding overfitting, with 10-fold cross-validation selecting the optimal lambda. We built a nomogram from the final model and calculated individual risk scores. We also tested the model performance through time-dependent receiver operating characteristic curves [area under the curve (AUC) at 1 year, 3 years, 5 years], calibration plots with 1000 bootstrap samples, and decision curve analysis (DCA) for clinical utility. The validation cohort used the same risk formula, with Kaplan-Meier curves comparing survival between risk groups. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

A total of 319 patients with PGI-DLBCL were included in this study, divided into the training cohort (n = 223, 70%) and the validation cohort (n = 96, 30%). The median age was 55 years (interquartile range: 36-69 years), with 48% of patients older than 60 years. Gender distribution was almost balanced, with 48.9% male and 51.1% female patients. ECOG performance status ≥ 2 was observed in 40.8% of patients. Lugano staging revealed stage I in 45.8%, stage II in 26.6%, and stage IV in 27.6%. Extranodal invasion at ≥ 2 sites was observed in 47% of patients, and tumor diameter exceeded 5 cm in 46.1%. Elevated serum biomarkers included β2-MG > 2.2 mg/L in 50.5% and LDH > 250 U/L in 27%. The International Prognostic Index score was 3-5 in 69.9% of patients, and the non-GCB subtype predominated at 59.9%. B symptoms were present in 55.8%, with primary symptoms including abdominal pain (22.9%), abdominal distension (17.6%), abdominal discomfort (15.4%), nausea and vomiting (7.2%), anorexia and weight loss (11.0%), altered bowel habits (6.9%), melena (6.6%), and space-occupying lesions (12.5%). Lesion morphology was ulcerative in 31.7%, raised in 28.8%, diffuse in 22.9%, and mixed in 16.6%, primarily located in the gastric body (26.0%), antrum (18.5%), angular incisure (21.3%), fundus (4.7%), and intestinal sites such as the duodenum (6.6%), jejunum (2.5%), ileum (2.8%), ileocecum (4.7%), and colon (12.9%). Treatment modalities included chemotherapy alone (34.5%), surgery alone (10.7%), combined surgery and chemotherapy (33.2%), and no treatment (21.6%). Tissue origin was primarily endoscopic biopsies (82.1%), with surgical tissue (16.0%) and abdominal mass puncture tissue (1.9%) less common.

Immunohistochemical analysis of the 319 PGI-DLBCL patients revealed the following protein expression frequencies (Table 1, Figures 1 and 2): CD10 was positive in 51.1% of patients; BCL-6 was positive in 53.3%; MUM-1 in 40.1%; BCL-2 in 49.2%; C-MYC in 48.3%; Ki-67 in 67.1%; CD5 in 42.6%; and EBER in 3.1%. Within the training cohort (n = 223), positivity rates were CD10: 53.8%, BCL-6: 56.1%, MUM-1: 40.4%, BCL-2: 47.5%, C-MYC: 47.1%, Ki-67: 68.2%, CD5: 43.9%, and EBER: 2.2%. Corresponding rates in the validation cohort (n = 96) were CD10: 44.8%, BCL-6: 46.9%, MUM-1: 39.6%, BCL-2: 53.1%, C-MYC: 51.0%, Ki-67: 64.6%, CD5: 39.6%, and EBER: 5.2%.

| Characteristics | Total population (n = 319) | Training cohort (n = 223) | Validation cohort (n = 96) | P value |

| Age, years, median (IQR) | 55 (36, 69) | 53 (36, 68) | 59.5 (36.8, 70.2) | 0.48 |

| Age > 60 years | 0.62 | |||

| No | 166 (52) | 114 (51.1) | 52 (54.2) | |

| Yes | 153 (48) | 109 (48.9) | 44 (45.8) | |

| Gender | 0.62 | |||

| Male | 156 (48.9) | 107 (48) | 49 (51) | |

| Female | 163 (51.1) | 116 (52) | 47 (49) | |

| ECOG ≥ 2 | 0.78 | |||

| No | 189 (59.2) | 131 (58.7) | 58 (60.4) | |

| Yes | 130 (40.8) | 92 (41.3) | 38 (39.6) | |

| Lugano stage | 0.79 | |||

| I | 146 (45.8) | 104 (46.6) | 42 (43.8) | |

| II | 85 (26.6) | 57 (25.6) | 28 (29.2) | |

| IV | 88 (27.6) | 62 (27.8) | 26 (27.1) | |

| Extranodal invasion site ≥ 2 | 0.60 | |||

| No | 169 (53) | 116 (52) | 53 (55.2) | |

| Yes | 150 (47) | 107 (48) | 43 (44.8) | |

| Tumor diameter > 5 cm | 0.30 | |||

| No | 172 (53.9) | 116 (52) | 56 (58.3) | |

| Yes | 147 (46.1) | 107 (48) | 40 (41.7) | |

| β2-MG > 2.2 mg/L | 0.89 | |||

| No | 158 (49.5) | 111 (49.8) | 47 (49) | |

| Yes | 161 (50.5) | 112 (50.2) | 49 (51) | |

| LDH > 250 U/L | 0.98 | |||

| No | 233 (73) | 163 (73.1) | 70 (72.9) | |

| Yes | 86 (27) | 60 (26.9) | 26 (27.1) | |

| IPI | 0.17 | |||

| 0-2 | 96 (30.1) | 62 (27.8) | 34 (35.4) | |

| 3-5 | 223 (69.9) | 161 (72.2) | 62 (64.6) | |

| Immunophenotyping | 0.11 | |||

| Non-GCB | 191 (59.9) | 140 (62.8) | 51 (53.1) | |

| GCB | 128 (40.1) | 83 (37.2) | 45 (46.9) | |

| B symptoms | 0.38 | |||

| No | 141 (44.2) | 95 (42.6) | 46 (47.9) | |

| Yes | 178 (55.8) | 128 (57.4) | 50 (52.1) | |

| Primary symptom | 0.38 | |||

| Abdominal pain | 73 (22.9) | 46 (14.4) | 27 (8.5) | |

| Abdominal distension | 56 (17.6) | 36 (11.3) | 20 (6.3) | |

| Abdominal discomfort | 49 (15.4) | 37 (11.6) | 12 (3.8) | |

| Nausea and vomiting | 23 (7.2) | 19 (6) | 4 (1.3) | |

| Anorexia and weight loss | 35 (11) | 28 (8.8) | 7 (2.2) | |

| Altered bowel habits | 22 (6.9) | 15 (4.7) | 7 (2.2) | |

| Melena | 21 (6.6) | 13 (4.1) | 8 (2.5) | |

| Space occupying lesion in the gastrointestinal tract | 40 (12.5) | 29 (9.1) | 11 (3.4) | |

| Lesion type | 0.24 | |||

| Ulceration | 101 (31.7) | 65 (29.1) | 36 (37.5) | |

| Raised | 92 (28.8) | 62 (27.8) | 30 (31.2) | |

| Diffuse | 73 (22.9) | 55 (24.7) | 18 (18.8) | |

| Mixed | 53 (16.6) | 41 (18.4) | 12 (12.5) | |

| Lesion site | 0.87 | |||

| Gastric fundus | 15 (4.7) | 12 (3.8) | 3 (0.9) | |

| Gastric body | 83 (26) | 58 (18.2) | 25 (7.8) | |

| Angular cisature | 68 (21.3) | 49 (15.4) | 19 (6) | |

| Gastric antrum | 59 (18.5) | 38 (11.9) | 21 (6.6) | |

| Intestinal duodenum | 21 (6.6) | 16 (5) | 5 (1.6) | |

| Jejunum | 8 (2.5) | 6 (1.9) | 2 (0.6) | |

| Ileum | 9 (2.8) | 6 (1.9) | 3 (0.9) | |

| Ileocecum | 15 (4.7) | 12 (3.8) | 3 (0.9) | |

| Colon | 41 (12.9) | 26 (8.2) | 15 (4.7) | |

| Treatment-modalities | 0.37 | |||

| Untreated | 69 (21.6) | 49 (22) | 20 (20.8) | |

| Chemotherapy | 110 (34.5) | 71 (31.8) | 39 (40.6) | |

| Surgery | 34 (10.7) | 27 (12.1) | 7 (7.3) | |

| Chemotherapy + surgery | 106 (33.2) | 76 (34.1) | 30 (31.2) | |

| Tissue origin | 0.98 | |||

| Endoscopic biopsies | 262 (82.1) | 183 (82.1) | 79 (82.3) | |

| Surgical tissue | 51 (16) | 36 (16.1) | 15 (15.6) | |

| Abdominal mass puncture tissue | 6 (1.9) | 4 (1.8) | 2 (2.1) | |

| CD10 | 0.14 | |||

| Negative | 156 (48.9) | 103 (46.2) | 53 (55.2) | |

| Positive | 163 (51.1) | 120 (53.8) | 43 (44.8) | |

| BCL-6 | 0.13 | |||

| Negative | 149 (46.7) | 98 (43.9) | 51 (53.1) | |

| Positive | 170 (53.3) | 125 (56.1) | 45 (46.9) | |

| MUM-1 | 0.90 | |||

| Negative | 191 (59.9) | 133 (59.6) | 58 (60.4) | |

| Positive | 128 (40.1) | 90 (40.4) | 38 (39.6) | |

| BCL-2 | 0.36 | |||

| Negative | 162 (50.8) | 117 (52.5) | 45 (46.9) | |

| Positive | 157 (49.2) | 106 (47.5) | 51 (53.1) | |

| C-MYC | 0.52 | |||

| Negative | 165 (51.7) | 118 (52.9) | 47 (49) | |

| Positive | 154 (48.3) | 105 (47.1) | 49 (51) | |

| CD5 | 0.47 | |||

| Negative | 183 (57.4) | 125 (56.1) | 58 (60.4) | |

| Positive | 136 (42.6) | 98 (43.9) | 38 (39.6) | |

| EBER | 0.27 | |||

| Negative | 309 (96.9) | 218 (97.8) | 91 (94.8) | |

| Positive | 10 (3.1) | 5 (2.2) | 5 (5.2) | |

| Ki-67 | 0.26 | |||

| Negative | 105 (32.9) | 71 (31.8) | 34 (35.4) | |

| Positive | 214 (67.1) | 152 (68.2) | 62 (64.6) | |

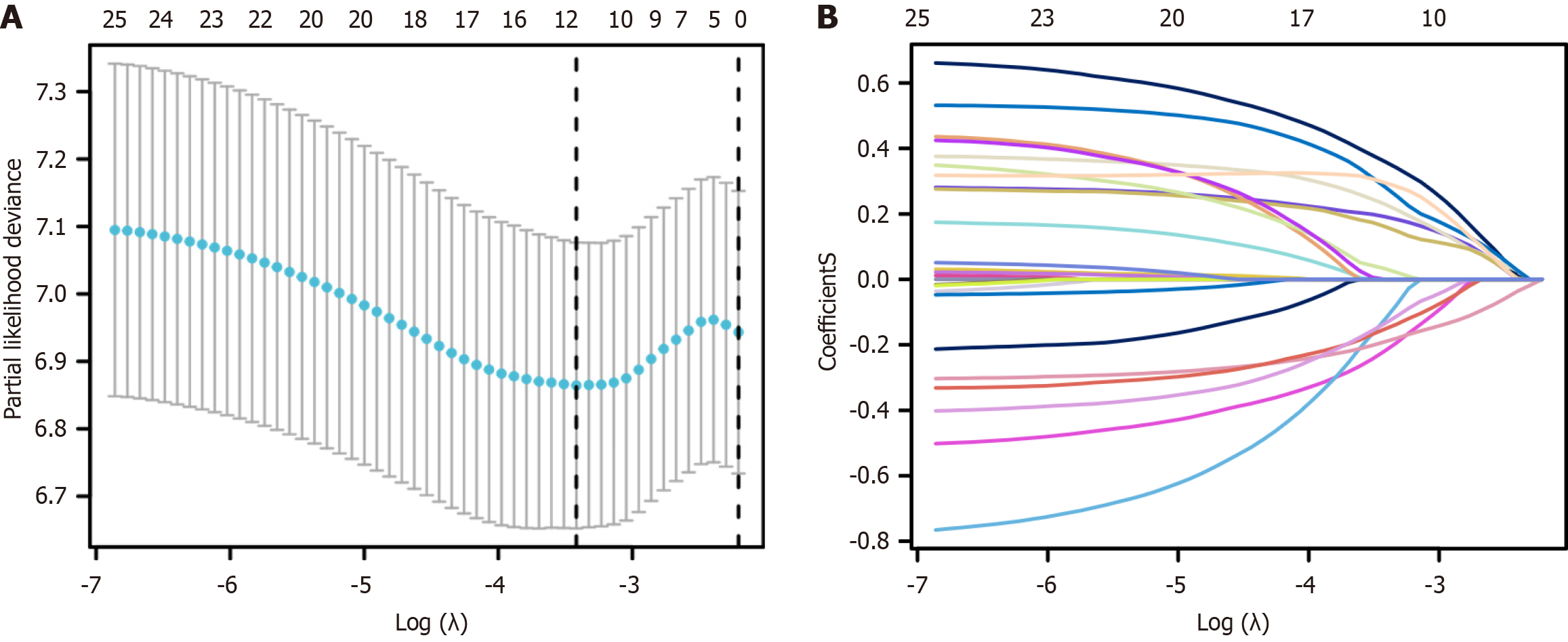

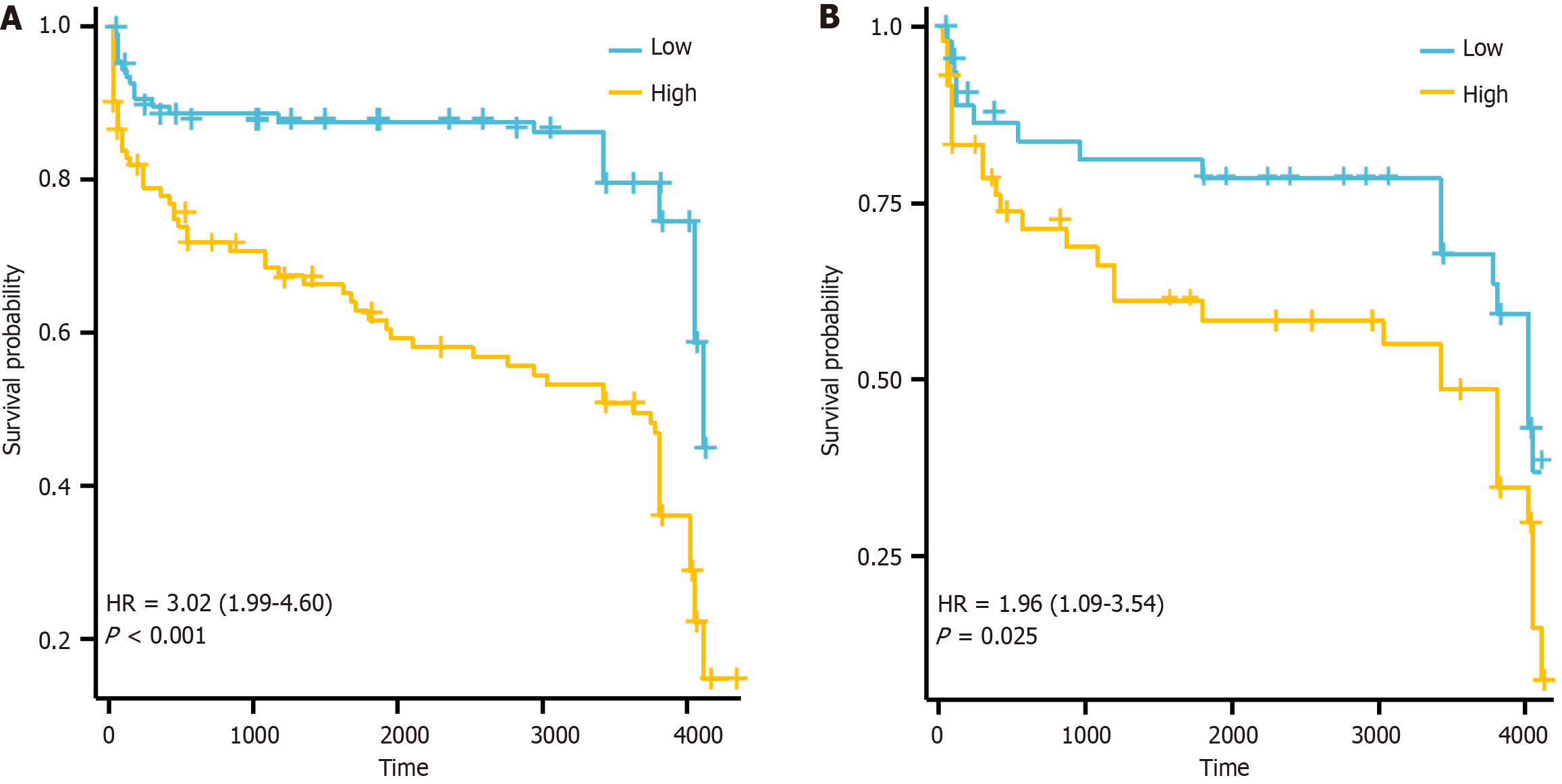

LASSO regression analysis identified the following variables with non-zero regression coefficients: Age > 60 years, gender, ECOG ≥ 2, extranodal invasion site ≥ 2, β2-MG > 2.2 mg/L, LDH > 250 U/L, B symptoms, lesion type, tissue origin, BCL-6, MUM-1, BCL-2, and CD5 (Figure 3, Table 2). Based on univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses, extranodal sites ≥ 2, B symptoms, mixed lesion type, and negative MUM-1 expression were identified as independent risk factors for PGI-DLBCL (Table 3). Based on the optimal risk cut-off value, patients were categorized into high- and low-risk groups. Survival analysis demonstrated that the overall survival of high-risk patients was significantly shorter than that of low-risk patients in the training cohort (Figure 4). The AUC values for predicting 1-, 3-, and 5-year overall survival were 0.625, 0.663, and 0.723, respectively (Figure 5). Comparable findings were observed in the validation cohort using the unified formula, confirming the robustness of the risk model (Figures 4 and 5). The DCA curve also suggested good predictive power (Figure 6).

| Characteristics | LASSO (minute) |

| Age > 60 years | 0.191848352 |

| Gender | -0.219651952 |

| ECOG ≥2 | 0.360853083 |

| Extranodal invasion site ≥ 2 | -0.123956342 |

| β2-MG > 2.2 mg/L | 0.230048478 |

| LDH > 250 U/L | 0.161655196 |

| B symptoms | 0.283986826 |

| Lesion type | -0.19044022 |

| Tissue origin | 0.033236256 |

| BCL-6 | -0.15250168 |

| MUM-1 | 0.295835406 |

| BCL-2 | -0.135437307 |

| CD5 | 0.191848352 |

| Characteristic | Category | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

| HR (95%CI) | P value | HR (95%CI) | P value | ||

| Age (year) | ≤ 60 | Reference | - | Reference | - |

| > 60 | 1.49 (1.01-2.21) | 0.045 | 1.34 (0.90-2.02) | 0.153 | |

| Gender | Male | Reference | - | NA | NA |

| Female | 1.27 (0.86-1.89) | 0.232 | NA | NA | |

| ECOG PS ≥ 2 | 0-1 | Reference | - | Reference | - |

| ≥ 2 | 1.52 (1.03-2.25) | 0.034 | 1.52 (0.96-2.41) | 0.075 | |

| Extranodal sites ≥ 2 | No | Reference | - | NA | NA |

| Yes | 1.00 (0.68-1.48) | 0.992 | NA | NA | |

| β2-MG (mg/L) | ≤ 2.2 | Reference | - | Reference | - |

| > 2.2 | 1.56 (1.05-2.31) | 0.029 | 1.39 (0.91-2.11) | 0.126 | |

| LDH (U/L) | ≤ 250 | Reference | - | Reference | - |

| > 250 | 0.65 (0.44-0.95) | 0.028 | 0.79 (0.52-1.20) | 0.266 | |

| B symptoms | No | Reference | - | Reference | - |

| Yes | 1.64 (1.08-2.48) | 0.019 | 1.56 (1.00-2.41) | 0.048 | |

| Lesion type | Ulcerative | Reference | - | Reference | - |

| Mixed | 0.23 (0.10-0.53) | < 0.001 | 0.21 (0.09-0.49) | < 0.001 | |

| Raised | 1.09 (0.64-1.87) | 0.742 | 1.14 (0.65-1.98) | 0.647 | |

| Diffuse | 1.62 (0.99-2.64) | 0.053 | 1.30 (0.77-2.21) | 0.331 | |

| Tissue origin | Endoscopic (1) | Reference | - | NA | NA |

| Abdominal mass (3) | 1.27 (0.80-2.01) | 0.307 | NA | NA | |

| Surgical (2) | 0.81 (0.49-1.34) | 0.405 | NA | NA | |

| BCL-6 | Negative | Reference | - | NA | NA |

| Positive | 0.72 (0.49-1.07) | 0.104 | NA | NA | |

| MUM-1 | Positive | Reference | - | Reference | - |

| Negative | 0.68 (0.46-1.02) | 0.062 | 0.63 (0.41-0.97) | 0.034 | |

| CD5 | Negative | Reference | - | NA | NA |

| Positive | 0.73 (0.49-1.09) | 0.122 | NA | NA | |

According to GLOBOCAN of the World Health Organization, there were 92834 new cases of NHL in China in 2020. The GI tract is the most common site of NHL invasion, accounting for 20%-40% of all extranodal lymphomas, and most of these cases are primary lesions involving the GI tract[3]. PGI-DLBCL poses significant diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. We analyzed 319 patients from Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region to characterize the clinical features and develop a prognostic model for risk stratification. Our findings provide insights into regional disease patterns and highlight opportunities for improved management strategies.

The demographic profile of our cohort - the median age was 55 years (interquartile range: 36-69 years), with 48% of patients older than 60 years and a slight male predominance (48.9%) - aligns with Chinese[8] reports but shows a younger trend than Western populations[9]. Abdominal pain (22.9%) and distension (17.6%) were the predominant presenting symptoms, frequently accompanied by B symptoms (55.8%) and elevated LDH (27%) or β2-MG (50.5%). These nonspecific manifestations often delay diagnosis, with many patients presenting at advanced stages. Endoscopic examination revealed ulcerative (31.7%) and raised lesions (28.8%) as the most common findings, primarily affecting the gastric body and antrum. The submucosal origin of these tumors complicates diagnosis, as superficial biopsies frequently yield false-negative results.

Based on these clinical observations, we developed a LASSO-Cox prognostic model incorporating clinical variables (age > 60, ECOG ≥ 2, LDH, B symptoms) and immunohistochemical markers (BCL-6, MUM-1, BCL-2, CD5). This model effectively stratified patients into high- and low-risk groups with significantly different survival outcomes (P < 0.05), underscoring its discriminative value. The time-dependent receiver operating characteristic curves further supported its robustness, with AUCs of 0.625, 0.663, and 0.723 at 1 year, 3 years, and 5 years in the training cohort, closely mirrored by the validation cohort. Importantly, DCA indicated good clinical utility, suggesting that its application could inform real-time clinical decisions by balancing prognostic benefit against intervention risks. Beyond prognostication, our model - leveraging routinely accessible clinical and immunohistochemical variables - facilitates early diagnosis by identifying high-risk patients for expedited management, making it particularly valuable in resource-limited settings, while also providing a practical bridge toward future molecular stratification in precision medicine.

In our multivariate analysis of PGI-DLBCL, the following four independent prognostic factors were identified, extranodal involvement at ≥ 2 sites, presence of B symptoms, mixed lesion morphology, and negative MUM-1 expression, which align with the established understanding of DLBCL biology. Multiple extranodal sites indicate disseminated disease and a higher risk of involvement of sanctuary organs, reflecting aggressive tumor biology and enhanced invasive capacity of tumor cells[10,11]. B symptoms were present in over half of our cohort, reflecting systemic tumor burden and inflammatory response, resulting from increased cytokine production by malignant B cells and the tumor microenvironment. Mixed lesion morphology was associated with better survival, possibly due to heterogeneous tumor biology or improved accessibility for early detection and treatment[6,7]. Negative MUM-1 expression emerged as a protective factor, potentially reflecting distinct GI tumor biology influenced by the local microenvironment, differing from nodal DLBCL[12,13]. Integrating these factors captured the multifaceted nature of PGI-DLBCL, encompassing disease extent, systemic impact, morphological characteristics, and molecular features, and may offer more precise prognostic guidance than traditional staging alone.

Most tumors in our series showed high Ki-67 indices, which is expected given the aggressive proliferative nature of PGI-DLBCL. Surprisingly, traditional markers such as BCL-2, C-MYC, and BCL-6 failed to predict survival when we controlled for other variables. While this contradicts some published reports, it underscores how tricky immunohistochemistry interpretation can be when used alone. Our experience suggests that immunohistochemistry, although practical and widely available, works best when combined with molecular testing rather than relied upon in isolation[14-16]. For example, recent investigations have revealed that certain molecular biomarkers outperform traditional immunohistochemical markers in predicting adverse outcomes in PGI-DLBCL. Notably, miR-130a, which post-transcriptionally represses both BCL-6 and C-MYC, has been identified by Chen et al[17] as a more effective prognostic indicator for DLBCL. Similarly, miR-150, a known negative regulator of MYB, has also been validated as a sensitive predictor of clinical outcomes in this disease[18]. Non-GCB subtype was dominant in our patient population. Although we did not specifically analyze treatment response differences between GCB and non-GCB subtypes to rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisolone (R-CHOP) in our cohort, numerous studies have demonstrated that non-GCB DLBCL shows poorer responses to standard R-CHOP treatment, as reported by Li et al[19] these tumors simply do not respond as well to standard R-CHOP treatment. The biology helps explain why non-GCB tumors often carry mutations in genes such as MYD88, CD79B, IGLL5, and LRP1B that hijack cellular pathways[20-23], fueling tumor growth and creating resistance to chemotherapy. This underlying molecular chaos probably explains both why individual immunohistochemical markers have limited predictive value and why these tumors prove so stubborn when treated with conventional therapy.

Thus, it is necessary to move beyond immunohistochemistry alone and start combining it with genetic testing such as regulatory biomarker or targeted sequencing for better predictions. More urgently, new treatment options are needed such as Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibitors, lenalidomide, antibody-drug conjugates, and chimeric antigen receptor-T cell therapy[24], especially for high-risk patients that we can now identify through combined clinical and molecular profiling.

Our Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region patients showed some interesting regional variables as they were younger at diagnosis and had more non-GCB tumors than international cohorts. Their survival matched other Chinese studies but fell short of Western results, probably due to delayed diagnosis, treatment access issues, or genetic differences in our population. We recognize that our single-center retrospective approach has some limitations, including missing data and treatment variations; however, it does capture what actually happens in clinical practice. Going forward, we need well-designed multicenter studies that incorporate molecular testing and sensitive disease monitoring to develop risk strategies that work in our local setting. Building tissue banks for molecular analysis, and creating treatment plans that match the correct therapy to each patient’s molecular profile will further personalized treatment.

In summary, our study of 319 PGI-DLBCL patients from Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region sheds light on the distinctive clinical and biological features of this disease in a regional Chinese population. We identified the following four independent prognostic factors, extranodal involvement at ≥ 2 sites, B symptoms, mixed lesion morphology, and negative MUM-1 expression, that together offer a practical framework for risk stratification. These results highlight how disease burden, systemic symptoms, tumor morphology, and molecular characteristics collectively influence patient outcomes, emphasizing the importance of a comprehensive approach beyond conventional staging. Although traditional immunohistochemical markers such as BCL-2, C-MYC, and BCL-6 showed limited predictive power when considered alone, integrating clinical parameters with immunohistochemistry enabled us to construct a prognostic model to effectively distinguish high- and low- risk patients.

| 1. | Feng Y, Zheng S, Sun Y, Liu L. Location-specific analysis of clinicopathological characteristics and long-term prognosis of primary gastrointestinal diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Sci Rep. 2025;15:19574. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Alvarez-Lesmes J, Chapman JR, Cassidy D, Zhou Y, Garcia-Buitrago M, Montgomery EA, Lossos IS, Sussman D, Poveda J. Gastrointestinal Tract Lymphomas. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2021;145:1585-1596. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Olszewska-Szopa M, Wróbel T. Gastrointestinal non-Hodgkin lymphomas. Adv Clin Exp Med. 2019;28:1119-1124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Chen X, Wang J, Liu Y, Lin S, Shen J, Yin Y, Wang Y. Primary intestinal diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: novel insights and clinical perception. Front Oncol. 2024;14:1404298. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ghimire P, Wu GY, Zhu L. Primary gastrointestinal lymphoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:697-707. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 245] [Cited by in RCA: 281] [Article Influence: 18.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 6. | Juárez-Salcedo LM, Sokol L, Chavez JC, Dalia S. Primary Gastric Lymphoma, Epidemiology, Clinical Diagnosis, and Treatment. Cancer Control. 2018;25:1073274818778256. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Liu YM, Yang XJ. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided cutting of holes and deep biopsy for diagnosis of gastric infiltrative tumors and gastrointestinal submucosal tumors using a novel vertical diathermic loop. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:2795-2801. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Chen Y, Chen Y, Chen S, Wu L, Xu L, Lian G, Yang K, Li Y, Zeng L, Huang K. Primary Gastrointestinal Lymphoma: A Retrospective Multicenter Clinical Study of 415 Cases in Chinese Province of Guangdong and a Systematic Review Containing 5075 Chinese Patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94:e2119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Dizengof V, Levi I, Etzion O, Fich A, Blum A, Chertok IRA, Ben-Yakov G, Rouvio O, Greenbaum U. Incidence rates and clinical characteristics of primary gastrointestinal non-Hodgkin lymphoma: a population study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;32:569-574. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Roschewski M, Staudt LM, Wilson WH. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma-treatment approaches in the molecular era. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2014;11:12-23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 303] [Cited by in RCA: 318] [Article Influence: 26.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Klener P, Klanova M. Drug Resistance in Non-Hodgkin Lymphomas. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:2081. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Craig VJ, Cogliatti SB, Arnold I, Gerke C, Balandat JE, Wündisch T, Müller A. B-cell receptor signaling and CD40 ligand-independent T cell help cooperate in Helicobacter-induced MALT lymphomagenesis. Leukemia. 2010;24:1186-1196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Shaffer AL, Lin KI, Kuo TC, Yu X, Hurt EM, Rosenwald A, Giltnane JM, Yang L, Zhao H, Calame K, Staudt LM. Blimp-1 orchestrates plasma cell differentiation by extinguishing the mature B cell gene expression program. Immunity. 2002;17:51-62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 800] [Cited by in RCA: 810] [Article Influence: 33.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Xu-Monette ZY, Wei L, Fang X, Au Q, Nunns H, Nagy M, Tzankov A, Zhu F, Visco C, Bhagat G, Dybkaer K, Chiu A, Tam W, Zu Y, Hsi ED, Hagemeister FB, Sun X, Han X, Go H, Ponzoni M, Ferreri AJM, Møller MB, Parsons BM, van Krieken JH, Piris MA, Winter JN, Li Y, Xu B, Albitar M, You H, Young KH. Genetic Subtyping and Phenotypic Characterization of the Immune Microenvironment and MYC/BCL2 Double Expression Reveal Heterogeneity in Diffuse Large B-cell Lymphoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2022;28:972-983. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Pătraşcu AM, Rotaru I, Olar L, Pătraşcu Ş, Ghiluşi MC, NeamŢu SD, Nacea JG, Gluhovschi A. The prognostic role of Bcl-2, Ki67, c-MYC and p53 in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2017;58:837-843. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Balikó A, Szakács Z, Kajtár B, Ritter Z, Gyenesei A, Farkas N, Kereskai L, Vályi-Nagy I, Alizadeh H, Pajor L. Clinicopathological analysis of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma using molecular biomarkers: a retrospective analysis from 7 Hungarian centers. Front Oncol. 2023;13:1224733. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Chen L, Kan Y, Wang X, Ge P, Ding T, Zhai Q, Wang Y, Yu Y, Wang X, Zhao Z, Yang H, Liu X, Li L, Qiu L, Zhang H, Qian Z, Zhao H. Overexpression of microRNA-130a predicts adverse prognosis of primary gastrointestinal diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Oncol Lett. 2020;20:93. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Wang X, Kan Y, Chen L, Ge P, Ding T, Zhai Q, Yu Y, Wang X, Zhao Z, Yang H, Liu X, Li L, Qiu L, Qian Z, Zhang H, Wang Y, Zhao H. miR-150 is a negative independent prognostic biomarker for primary gastrointestinal diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Oncol Lett. 2020;19:3487-3494. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Li L, Li Y, Que X, Gao X, Gao Q, Yu M, Ma K, Xi Y, Wang T. Prognostic significances of overexpression MYC and/or BCL2 in R-CHOP-treated diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: A Systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2018;8:6267. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Li SS, Zhai XH, Liu HL, Liu TZ, Cao TY, Chen DM, Xiao LX, Gan XQ, Cheng K, Hong WJ, Huang Y, Lian YF, Xiao J. Whole-exome sequencing analysis identifies distinct mutational profile and novel prognostic biomarkers in primary gastrointestinal diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Exp Hematol Oncol. 2022;11:71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Shen R, Fu D, Dong L, Zhang MC, Shi Q, Shi ZY, Cheng S, Wang L, Xu PP, Zhao WL. Simplified algorithm for genetic subtyping in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023;8:145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Chen R, Zhou D, Wang L, Zhu L, Ye X. MYD88(L265P) and CD79B double mutations type (MCD type) of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: mechanism, clinical characteristics, and targeted therapy. Ther Adv Hematol. 2022;13:20406207211072839. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Leveille E, Kothari S, Müschen M. Genetic Modeling of B-cell State Transitions for Rational Design of Lymphoma Therapies. Blood Cancer Discov. 2023;4:8-11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | D'Alò F, Bellesi S, Maiolo E, Alma E, Bellisario F, Malafronte R, Viscovo M, Campana F, Hohaus S. Novel Targets and Advanced Therapies in Diffuse Large B Cell Lymphomas. Cancers (Basel). 2024;16:2243. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/