Published online Dec 15, 2025. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v17.i12.113387

Revised: September 28, 2025

Accepted: October 31, 2025

Published online: December 15, 2025

Processing time: 109 Days and 22.4 Hours

Pancreatic cancer has an extremely poor prognosis. Although surgery is the first-line treatment for pancreatic cancer, its role is ultimately limited because patients often present too late for resection. Thus, multidisciplinary treatment approaches are needed. In particular, chemotherapy, targeted therapy, and immunotherapy can be ineffective for locally advanced pancreatic cancer (LAPC) because of its resistance to these modalities, but cryoablation has shown significant promise for treating this entity and prolonging survival.

To investigate the safety and efficacy of cryoablation for LAPC.

Clinical and laboratory data, including surgical procedure, postoperative complications, immunobiochemical markers (e.g., carbohydrate antigen 19-9), and follow-up visits, of 24 LAPC patients treated with cryoablation at the department of hepatobiliary and pancreatic surgery of our hospital from January 2023 to De

Surgery was smooth in all patients, with no perioperative deaths. Postoperative pancreatic fistulas occurred in 18 patients (75.0%), including biochemical leak in 14 cases and grade B (fistula) in 4 cases. Three patients (12.5%) had delayed gastric emptying. The carbohydrate antigen 19-9 level remained low on postoperative day 30 (P < 0.05). Immune markers (natural killer cells and tumor necrosis factor-alpha) significantly increased on days 7 and 30 (P < 0.01 or P < 0.05), whereas cluster of differentiation CD4+ T cells levels on day 30 significantly differed from baseline. Day 30 pain scores were significantly lower than preoperative ones (P < 0.01). Tumor volume was reduced on postoperative computed tomography. Survival was prolonged. The overall survival time of LAPC patients treated with cryoablation was 16.8 months.

Cryoablation can directly inactivate LAPC and boost immunity, thus delaying tumor progression, alleviating pain, improving quality of life, and prolonging survivals. Therefore, it is a safe and effective treatment option for LAPC.

Core Tip: Pancreatic cancer has an extremely poor prognosis. In particular, chemotherapy, targeted therapy, and immunotherapy may be ineffective for locally advanced pancreatic cancer (LAPC) because of its resistance to these modalities. In this retrospective study, 24 LAPC patients were treated with cryoablation at our hospital. The outcomes show that cryoablation can directly inactivate LAPC and boost immunity, thus delaying tumor progression, alleviating pain, improving quality of life, and prolonging survivals. Therefore, it is a safe and effective treatment option for LAPC that deserves wider adoption in clinical settings.

- Citation: Kang LM, He XL, Lang L, Wang AY, Wang X, Liu YH, Zhao YH, Xu L, Yu FK, Zhang FW. Safety and efficacy of cryoablation in treating locally advanced pancreatic cancer. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2025; 17(12): 113387

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v17/i12/113387.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v17.i12.113387

Pancreatic cancer is a highly malignant digestive system solid tumor characterized by insidious onset, difficult early diagnosis, rapid progression, and extremely poor prognosis. According to Global Cancer Statistics 2020, pancreatic cancer is the seventh leading cause of global cancer deaths[1]. Surgery remains the mainstay of treatment for pancreatic cancer, with the main procedures including pancreaticoduodenectomy (Whipple procedure), removal of the pancreatic body and tail with splenectomy, and total pancreatectomy. However, a significant proportion of patients present too late for a curative surgery, with less than 20% of pancreatic cancers being resectable[2]. Therefore, surgery alone has a limited role in treating pancreatic cancer, and multidisciplinary approaches are essential for the diagnosis and treatment of pancreatic cancer.

Locally advanced pancreatic cancer (LAPC) refers to pancreatic tumors with arterial encasement (> 180°) of the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) or celiac trunk; involving the celiac trunk and abdominal aorta; invading or embolizing the superior mesenteric vein (SMV) or portal vein (which makes the SMV and portal vein unresectable and/or unreconstructable); and/or extensively invading the distal jejunal drainage branch of the SMV[3]. Currently, the main treatments for LAPC include chemotherapy (based on gemcitabine, nab–paclitaxel, fluorouracil, oxaliplatin, irinotecan, tegafur/gimeracil/oteracil, and capecitabine)[4], targeted therapy (e.g., erlotinib), and immunotherapy[5]. However, due to its unique microenvironment, pancreatic cancer is often resistant to chemotherapy, targeted therapy, and immunotherapy, resulting in poor treatment outcomes[6,7]. While ablative therapies such as microwave ablation and high-intensity focused ultrasound have shown promise for solid tumors (e.g., liver cancer)[8], their use in pancreatic cancer, including LAPC, is limited because pancreatic cancer often invades many neighboring vital and complex blood vessels and tissues, making the ablation procedure extremely technically difficult and easily leading to fatal complications such as pancreatic leakage, bile leakage, intestinal perforation, and massive bleeding due to the heat generated[9]. Finding better treatments for LAPC is currently a major research focus. Cryoablation is an emerging therapy showing satisfactory results in treating liver, prostate, kidney, and breast cancers[10]. Recently, this technology has been increasingly applied to LAPC, showing significant progress. Here, we investigated the safety and effectiveness of ultrasound-guided laparotomic cryoablation in LAPC patients.

The clinical data of 24 LAPC patients treated with ultrasound-guided laparotomic cryoablation at the Department of Hepatobiliary and Pancreatic Surgery of our hospital from January 2023 to December 2024 were retrospectively analyzed. The study had been approved by the Ethics Committee of our hospital. The inclusion criteria included: (1) Radiologically and pathologically confirmed unresectable LAPC; (2) Adequate cardio-pulmonary function for general anesthesia; (3) Males and females aged 18-80 years; and (4) Willing to comply with the procedural requirements and provide written informed consent. The exclusion criteria were: (1) A history of arrhythmia, myocardial infarction, epilepsy, and/or pacemaker placement; (2) Severe cardiac/pulmonary/renal insufficiency or inability to tolerate anesthesia; (3) American Joint Committee on Cancer stage IV pancreatic cancer (i.e., with distant metastases); (4) Acute infections; and (5) A history of psychiatric illness or mental abnormality and/or unable to cooperate voluntarily. All cases were confirmed as pancreatic cancer by intraoperative frozen pathology and postoperative immunohistochemistry. Of the 24 patients, there were 16 males and 8 females, with an average age of 63.25 ± 10.06 years. The tumors were located at the pancreatic head/neck in 6 cases and at the pancreatic body/tail in 18 cases. All cases in this study had unresectable LAPC that invaded the celiac trunk or portal vein or SMA and vein. Among them, one case (20.83%) had invasion of the SMA, four cases had invasion of celiac trunk and common hepatic artery, 6 cases (25.00%) had invasion of portal vein-SMV, and 13 cases (54.17%) had both arterial and venous invasion (Table 1).

| Characteristics | Values |

| Male/female | 16 (66.66)/8 (33.33) |

| Age, mean ± SD (years) | 63.25 ± 10.06 |

| Tumor site | |

| Head and neck of the pancreas | 6 (25.00) |

| Body and tail of the pancreas | 18 (75.00) |

| AJCC tumor stage | |

| II | 16 (66.66) |

| III | 8 (33.33) |

| Preoperative comorbidities | |

| Pain | 20 (83.33) |

| Obstructive jaundice | 4 (16.67) |

| Gastrointestinal obstruction | 2 (8.33) |

| Tumor invasion of blood vessels | |

| Superior mesenteric artery | 1 (4.16) |

| Celiac trunk/common hepatic artery | 4 (16.67) |

| Portal vein/superior mesenteric vein | 6 (25.00) |

| Both arterial and venous invasion | 13 (54.17) |

Instruments and materials: The instruments and materials used in the surgeries included an abdominal surgical kit (SMIC, Shanghai, China), the MindrayC5-1s convex probe for the M9 system (Mindray, Shenzhen, China), a cryoablation needle (01HW1530 L; AccuTargetMed, Shanghai, China), a cryoablation system (AT-2008-II; AccuTargetMed, Shanghai, China), and a biopsy needle (MC1816; Bard PeripheralVascular, Inc., Shanghai, China).

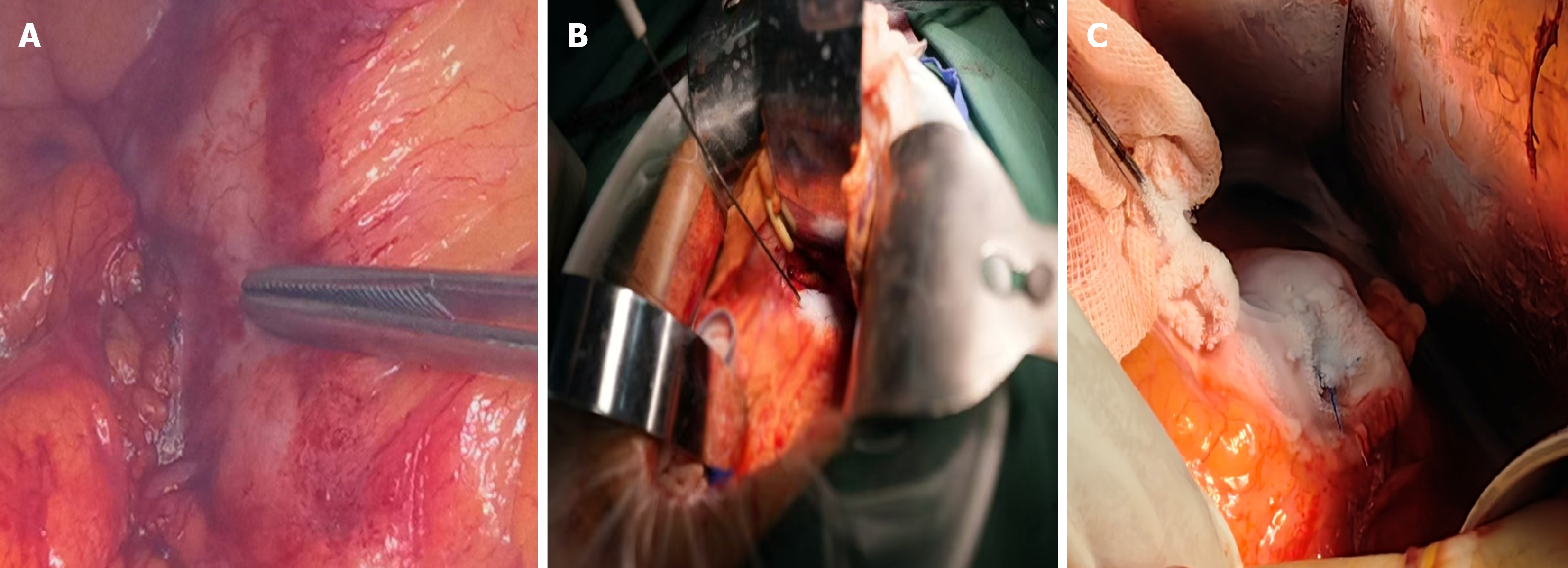

Surgical procedure: Under general anesthesia, the patient was positioned supine, with the use of a lumbar support pillow. Disinfection, draping, and application of surgical films were routinely performed. An incision was created in the midline of the upper abdomen. Tissues were dissected layer by layer to access the abdominal cavity. Abdominal exploration, supplemented by intraoperative ultrasound, further confirmed that the pancreatic tumor was inoperable; however, there were no visible metastatic lesions (naked eye and ultrasound). The gastrocolic ligament was divided to fully expose the pancreas and tumors. For tumors located in the head/neck of the pancreas, the Kocher maneuver was performed to mobilize the duodenum and pancreatic head posterior to the tumors. For tumors located in the body/tail of the pancreas, gauze pads were applied at the ligament of Treitz, below the transverse mesocolon and behind the stomach, for tamponade and protection. For positioning, intraoperative ultrasound was performed by sonographers with extensive experience in abdominal ultrasound. During the intraoperative ultrasound-guided biopsy, 2-3 tissue strips were collected at the tumor site using disposable biopsy needles for rapid intraoperative pathological examination.

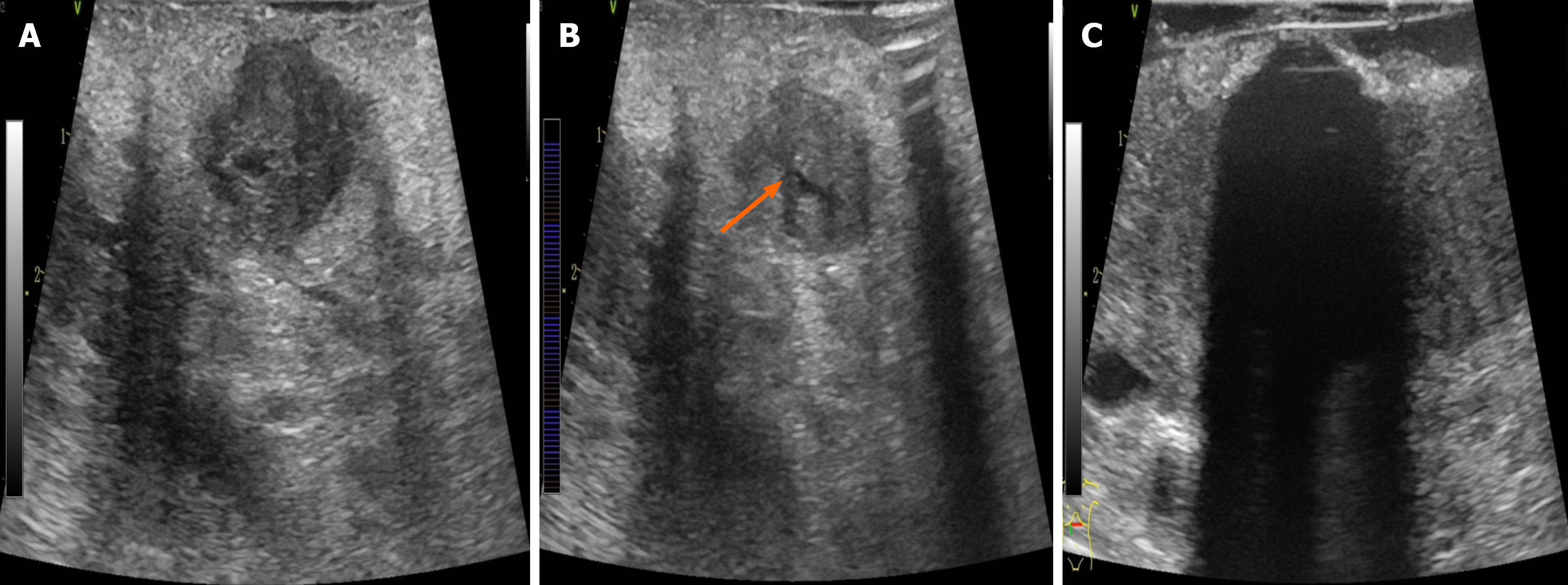

After the tumor location, size, and vascular/ductal relationships were identified by ultrasound, an ablation plan was developed to determine the needling site/direction, freezing duration, and therapeutic cycles. The 8 MHz linear array probe was used to explore the location of the tumor and its relationship with important structures such as blood vessels, biliary and pancreatic ducts, and duodenum to determine the puncture site, angle, and needle depth. During intraoperative ultrasound examination, the SMA/SMV, splenic artery and vein, portal vein, common hepatic artery, gastroduodenal artery, common bile duct, and pancreatic duct were exposed. Care should be taken to avoid injury during puncture and freezing. It was worth noting that when the portal vein-SMV or splenic vein is invaded, it will lead to systemic or regional portal hypertension, and varicose thickening of the peripancreatic vein. LAPC is usually combined with pancreatic duct dilatation, especially when puncture is performed. Cryoablation has a unique “hot pool effect”. The large blood vessels will expand with cold stimulation, the blood flow rate will accelerate, and the cold energy will be taken away quickly. Therefore, during the cryoablation process, large blood vessels above 3 mm should not be frozen and destroyed so as to avoid the damage of major blood vessels. This is the unique advantage of cryoablation in the treatment of LAPC. Typically, a 17-G 01HW1530 L needle was inserted under ultrasound guidance up to the tumor base (Figure 1A and B). The cryoablation system was initiated to rapidly freeze the target area to -140 °C to -160 °C, which took 5-15 minutes; subsequently, rewarming mode (approximately 3 minutes) was initiated to heat the target area to > 30 °C, thus completing one treatment cycle. During cryoablation, the ice ball was initially ellipsoidal in shape but became more rounded with longer treatment time. During freezing, the puncture site was continuously rinsed with flowing water to prevent frostbite injury to the surrounding tissues. The size of the ice ball and its relationships with the tumor and surrounding structures were monitored with ultrasound throughout freezing, thus ensuring satisfactory coverage (i.e., reaching or exceeding the tumor margins as far as possible without damaging surrounding structures, such as blood vessels, intestines, and bile ducts) (Figure 1C). The ice ball was droplet-shaped and centered on the tip of the needle on the ultrasound image, along with small, pointed, cone-shaped strong echoes at the edge, homogeneous low-amplitude echoes inside, and posterior acoustic shadowing, which gradually expanded to two sides and the rear. The lower edge of the ice ball was difficult to distinguish due to artifacts, so the morphology of the ice ball needed to be observed from multiple angles (Figure 2). Upon completion of freezing, the site was rewarmed to 30 °C for one cycle. Two cycles were typically required. The needle was rotated gently and then withdrawn at a moderate speed. If the ice ball failed to completely cover the margins of the lesion (defined as the edge of the ice ball, > 5 mm beyond the tumor range) after two ablation cycles, the position of the ablation needle was adjusted after rewarming, and an additional cycle was performed. Upon completion of the treatment, a 4-0 Prolene suture was used to close the puncture site to prevent bleeding and pancreatic leakage. For patients with biliary or gastrointestinal obstruction, cryoablation therapy might be followed by palliative cholangiojejunostomy and/or gastrojejunal anastomosis, depending on the situation.

The main measures included: (1) Perioperative indicators (operation time, blood loss, cryoablation cycles, and surgical procedures); (2) Complications (post operative bleeding, pancreatic leakage, gastric emptying disorders, etc.). Postoperative complications were graded according to the Clavien-Dindo grading system (for general surgical complications), and the International Study Group of Pancreatic Fistula criteria (for pancreatic fistula), and International Study Group of Pancreatic Fistula definitions (for delayed gastric emptying); (3) Immunohistochemical markers [amylase levels on postoperative days 1, 3, and 5, pre-/post-operative carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA199), and pre-/post-operative CD4+/CD8+ T cells]; and (4) Tumor size, as assessed by regular abdominal contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scans at follow-up visits. Pain was scored using a visual analogue scale. Survival was assessed through outpatient or phone visits. Follow-up continued until either December 31, 2024 or until a participant was lost to follow-up or died, which ever occurred first.

Data were statistically analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 19.0 (IBMCorp., Armonk, NY, United States), and plotted using GraphPad Prism 9.0 software (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, United States). Measurement data are expressed as mean ± SD. The paired-samples t test was used for comparing means between two samples, one-way analysis of variance for comparing means among multiple samples, and the least significant difference method for pairwise comparison of means. For data with unequal variance, Tamhane’s T2 test was used to correct for multiple tests. The χ2 test was applied for analyzing count data. The Kaplan-Meier method and log-rank test were employed for survival analysis. A P value < 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant.

Cryoablation was smoothly performed in all the 24 patients (Table 2). The surgery lasted 90-152 minutes (average, 127.67 ± 18.79 minutes), with an intraoperative blood loss of 40-130 mL (average, 70.08 ± 27.42 mL). The cycle number was 1 in 8 patients, 2 in 12 patients, and 3 in 4 patients (Table 2).

| Variables | Values |

| Operative time (minutes) | 127.67 ± 18.79 |

| Blood loss (mL) | 70.08 ± 27.42 |

| Cryotherapy cycle | |

| 1 | 8 |

| 2 | 12 |

| 3 | 4 |

| Surgical method | |

| Cryoablation alone | 20 (83.33) |

| Cryoablation choledochojejunostomy | 4 (16.67) |

| Cryoablation choledochojejunostomy gastrointestinal anastomosis | 2 (8.33) |

No perioperative death occurred. The amylase level in the abdominal drainage fluid showed a transient increase after surgery. Biochemical leak, B, and C postoperative pancreatic fistulas occurred in 14, 4, and 0 patients, respectively. One patient suffered from delayed bleeding, which was resolved with conservative treatment. Other complications included gastric emptying disorders (n = 3) and pancreatic pseudocysts (n = 2). No patient required a second open surgery. Thus, cryoablation appears safe for LAPC; there were no fatal complications (Table 3).

| Complications | Value |

| Amylase level in the abdominal drainage fluid (U/mL) | |

| Postoperative day 1 | 2323.23 ± 1410.15 |

| Postoperative day 2 | 1735.41 ± 978.00 |

| Postoperative day 3 | 1261.69 ± 692.00 |

| Postoperative pancreatic fistulas | |

| Biochemical leak | 14 (58.33) |

| Grade B | 4 (16.66) |

| Grade C | 0 |

| Postoperative complications | |

| Delayed bleeding | 1 |

| Gastric emptying disorders | 3 |

| Pancreatic pseudocysts | 2 |

Changes in pre- and postoperative serum immunochemical markers (CA199, CD4+ T cells, etc.) and contrast-enhanced CT findings were compared. Compared with the preoperative levels, the CA199 level significantly decreased on postoperative day 30 (P < 0.001); natural killer cells and tumor necrosis factor-alpha, which reflect immune function, significantly increased on postoperative days 7 and 30 (P < 0.01 or P < 0.05); and CD4+ T cells differed significantly on postoperative day 30 (P < 0.01), suggesting that cryoablation helped to improve the immune function of patients with LAPC. The visual analogue scale pain score on day 30 was 2.58 ± 1.39; this was significantly lower than the preoperative one (P < 0.01), indicating cryoablation was effective in alleviating pain for LAPC patients and helped to improve the quality of life for those in advanced stages. A contrast-enhanced abdominal CT scan performed on day 30 revealed the maximum diameter of the tumors had decreased significantly after cryoablation (P < 0.01), suggesting cryoablation had a certain role in suppressing tumor growth (Table 4).

| Variables | Preoperative | Postoperative day 7 | P value | Postoperative day 30 | P value |

| CA199 (U/mL) | 542.10 ± 309.56 | 518.16 ± 297.83 | 0.340 | 159.30 + 120.79 | 0.001 |

| CD4+ T cells (cells/μL) | 510.91 ± 120.63 | 714.08 ± 229.63 | 0.014 | 811.75 ± 222.92 | 0.000 |

| CD8+ T cells (cells/μL) | 268.67 ± 43.05 | 266.33 ± 47.26 | 0.319 | 261.58 ± 45.58 | 0.189 |

| Natural killer cells (cells/μL) | 153.83 ± 33.25 | 197.83 ± 33.92 | 0.000 | 190.17 ± 36.97 | 0.012 |

| TNF-α (pg/mL) | 0.71 ± 0.20 | 1.38 ± 0.41 | 0.000 | 1.36 ± 0.33 | 0.000 |

| Pain scores | 5.08 ± 2.47 | 5.67 ± 1.50 | 0.189 | 2.58 ± 1.39 | 0.000 |

| Tumor size on CT (cm) | 3.79 ± 0.90 | 3.13 ± 0.53 | 0.001 |

After cryoablation, all 24 patients received further treatment in the department of oncology at our hospital: 10 received gemcitabine + albumin-bound paclitaxel, 6 received folinic acid, fluorouracil, irinotecan, and oxaliplatin; 6 received tegafur/gimeracil/oteracil monotherapy; and 2 refused chemotherapy and underwent regular follow-up visits. To further verify the efficacy of cryoablation, 24 additional patients with inoperable LAPC receiving chemotherapy at our hospital during the same period were enrolled as the chemotherapy group. Their age, gender, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group physical strength score and American Joint Committee on Cancer tumor stages were matched to the cryoablation group (n = 24). Survival times were compared between the two groups (Table 5).

| Characteristics | Cryoablation group | Chemotherapy group | P value |

| Age (years) | 63.25 ± 10.06 | 65.25 ± 9.38 | 0.620 |

| Male/female | 16/8 | 14/10 | 0.340 |

| Tumor site | |||

| Head and neck of the pancreas | 6 | 8 | 0.333 |

| Body and tail of the pancreas | 18 | 16 | |

| AJCC tumor stage | |||

| II | 16 | 10 | 0.207 |

| III | 8 | 14 | |

| Tumor size on CT (cm) | 3.79 ± 0.90 | 3.67 ± 0.67 | 0.718 |

| ECOG physical score | |||

| 0 | 8 | 7 | 0.625 |

| 1 | 11 | 10 | |

| 2 | 4 | 5 | |

| 3 | 1 | 2 | |

| NRS-2002 nutrition score | |||

| 1 | 11 | 9 | 0.755 |

| 2 | 12 | 13 | |

| 3 | 1 | 2 | |

The patients in these groups were followed up for 3.3-22.6 months (median, 12.1 months). The 6-month overall survival (OS) rate showed no significant difference between the cryoablation group and the chemotherapy group (80.0% vs 75%, P = 0.73), whereas the 1-year OS rate was significantly higher in the cryoablation group (66.7% vs 37.5%, P = 0.041). Survival analysis also showed a significant difference in OS between these two groups (16.8 months vs 11.4 months, χ2 = 5.309, P = 0.021; Figure 3).

Despite the annual rise in R0 resection rates caused by improved pancreatic surgeries, the prognosis of pancreatic cancer remains poor, with less than 20% of patients with resectable pancreatic cancer benefiting from the optimized surgical techniques[11]. Feasible and effective treatments (in terms of survival and quality of life) for advanced pancreatic cancer, which accounts for more than 80% of all diagnosed pancreatic tumors, is the key to improving the overall treatment outcomes of pancreatic cancer[12]. For inoperable LAPC, multidisciplinary treatments including chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and targeted immunotherapy have been recommended but showed minimal efficacy[13,14]. Thermal ablation therapies, such as radiofrequency ablation and microwave ablation, have been attempted for treating pancreatic cancer[15,16] but their roles are limited by the risk of damaging nearby vital structures (i.e., bile ducts, the celiac trunk, and superior mesenteric arteries and veins) that are often invaded by the tumors[17].

Cryoablation is an anti-tumor treatment that kills tumor cells physically[18]. First, through precise ultrasound-guided puncture of the lesion, cryoablation technology enables the rapid freezing of the diseased tissue to below -160 °C within tens of seconds, forming an ice ball at the tip of the needle; subsequently, it quickly rewarms the frozen tissue to 30 °C. During the repeated freezing-rewarming processes, the intracellular ice crystals and extracellular fluid osmotic pressure gradients can directly cause tumor cells to dehydrate and burst[19]. Second, freezing can damage the microvascular endothelial cells around the tumor, causing platelet aggregation and thrombosis, which destroys the blood supply to the tumor and thus indirectly kills it[20]. Third, microstructures released from the broken tumor cells can serve as antigens that activate a specific immune response, potentially reversing systemic immunosuppression and improving tumor control[21]. Shao et al[21] compared the immune responses associated with focal thermal therapy, irreversible electroporation, and cryosurgery and found that cryosurgery released more total and native (not denatured) proteins, suggesting cryosurgery helps trigger the immune system. Gu et al[22] discovered that cryoablation reprogrammed the intratumoral immune microenvironment and increased CD8 T cell infiltration in lung cancer, showing a stronger effector signature, stronger interferon response, and greater cytolytic activity. In the present study, we analyzed immune cells following cryoablation for LAPC and found that CD4+ T cells, natural killer cells, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha significantly were increased on postoperative days 7 and 30, suggesting cryoablation facilitates improvement in immune function in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer.

Cryoablation, used clinically for over 20 years, is a mature anti-tumor treatment with proven effectiveness[23]. Cryoablation is subject to a unique “hot pool effect”, which means that the large blood vessels will be dilated during cold exposure, thus accelerating the blood flow and quickly taking away the cold energy. This effect can effectively protect large blood vessels more than 3 mm from the site of a cold injury. Thus, cryoablation is safer than thermal methods (e.g., radiofrequency ablation), especially for the pancreas due to its proximity to vital blood vessels[24]. A 2012 systematic review found that complications of cryoablation in advanced pancreatic cancer included gastric emptying disorders (incidence: 0%-40.9%) and pancreatic and biliary fistulas (incidence: 0%-6.8%)[25]. Of our 24 patients undergoing cryoablation, 14, 4, and 0 had biochemical leak, B, and C pancreatic fistulas, respectively. The total incidence of pancreatic fistula in 24 patients with LAPC was as high as 75%, which was much higher than that of pancreatic fistula complications related to general pancreatic surgery[26]. However, pancreatic fistula after cryoablation was mainly biochemical leak, and no fatal complications caused by pancreatic fistula occurred. The high incidence of pancreatic fistula may be related to the long-time cryoablation, and LAPC was usually associated with pancreatic duct expansion and pancreatic duct obstruction. In the later stage, it is necessary to further optimize the pancreatic cryoablation operation, strengthen the suture of the cryoablation puncture point during the operation, and enhance the perioperative management after the operation, which may help to reduce the incidence of pancreatic fistula. Other complications included delayed bleeding (n = 1), gastric emptying disorders (n = 3), and pancreatic pseudocysts (n = 2). There was no need for reoperation. The incidence of complication was similar to other studies[27]. Clinical observations indicate cryoablation is relatively safe and reliable for LAPC, with mild and controllable complications.

Pain in advanced pancreatic cancer seriously affects quality of life[28]. Li et al[29] performed cryoablation in 26 pancreatic cancer patients and observed that both painkiller use and pain scores significantly decreased after surgery. Cryoablation significantly alleviated clinical symptoms and reduced 30-day pain scores in LAPC patients, improving their quality of life. In addition, post-treatment CT on day 30 showed tumor shrinkage and a significant drop in CA199 levels, confirming the effectiveness of cryoablation in treating pancreatic cancer. The 6- and 12-month-postoperative survival rates were 80.0% and 66.7%, respectively, consistent with a previous study[18]. Finally, cryoablation plus chemotherapy prolonged the OS in LAPC patients compared to chemotherapy alone, suggesting there might be a synergistic effect between cryoablation and chemotherapy, which will be our future research focus.

Preliminary evidence indicates cryoablation is safe and reliable for LAPC, with minor postoperative complications that can be addressed by symptomatic management. The surgery improves immune function and reduces the CA199 level and tumor size; when combined with chemotherapy, it significantly extends survival compared to chemotherapy alone. Cryoablation can directly inactivate pancreatic tumors, control disease progression, and improve quality of life, showing clinically proven safety and effectiveness. Laparotomic ultrasound-guided cryoablation for LAPC reduces the incidence of accidental injury and complications, enabling more accurate and reliable punctures, which maximizes efficacy and minimizes the risk of cryoablation. Thus, this surgical technique is worthy of clinical promotion.

| 1. | Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75126] [Cited by in RCA: 68525] [Article Influence: 13705.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (201)] |

| 2. | Chen J, Chen H, Zhang T, Yin X, Man J, Yang X, Lu M. Burden of pancreatic cancer along with attributable risk factors in China from 1990 to 2019, and projections until 2030. Pancreatology. 2022;22:608-618. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Boggi U, Kauffmann EF, Napoli N, Barreto SG, Besselink MG, Fusai GK, Hackert T, Hilal MA, Marchegiani G, Salvia R, Shrikhande SV, Truty M, Werner J, Wolfgang C, Bannone E, Capretti G, Cattelani A, Coppola A, Cucchetti A, De Sio D, Di Dato A, Di Meo G, Fiorillo C, Gianfaldoni C, Ginesini M, Hidalgo Salinas C, Lai Q, Miccoli M, Montorsi R, Pagnanelli M, Poli A, Ricci C, Sucameli F, Tamburrino D, Viti V, Cameron J, Clavien PA, Asbun HJ; REDISCOVER guidelines group. REDISCOVER guidelines for borderline-resectable and locally advanced pancreatic cancer: management algorithm, unanswered questions, and future perspectives. Updates Surg. 2024;76:1573-1591. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Mastrantoni L, Chiaravalli M, Spring A, Beccia V, Di Bello A, Bagalà C, Bensi M, Barone D, Trovato G, Caira G, Giordano G, Bria E, Tortora G, Salvatore L. Comparison of first-line chemotherapy regimens in unresectable locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer: a systematic review and Bayesian network meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2024;25:1655-1665. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Lai ECH, Ung AKY. Update on management of pancreatic cancer: a literature review. Chin Clin Oncol. 2024;13:41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Di Y, Song J, Wang Y, Meng L. Impact of radiotherapy on the survival of unresectable locally advanced pancreatic cancer. Asian J Surg. 2024;47:3564-3566. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Jiang L, Huang X, Hua X, Li Q, Zhang Y, Wang J, Li S. Treatment of locally advanced pancreatic cancer with irreversible electroporation and intraoperative radiotherapy. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr. 2024;13:1087-1090. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Charalel RA, Mushlin AI, Li D, Mao J, Ibrahim S, Carlos RC, Kwan SW, Fortune B, Talenfeld AD, Brown RS Jr, Madoff DC, Johnson MS, Sedrakyan A. Long-Term Survival After Surgery Versus Ablation for Early Liver Cancer in a Large, Nationally Representative Cohort. J Am Coll Radiol. 2022;19:1213-1223. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Farmer W, Hannon G, Ghosh S, Prina-Mello A. Thermal ablation in pancreatic cancer: A scoping review of clinical studies. Front Oncol. 2022;12:1066990. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kwak K, Yu B, Lewandowski RJ, Kim DH. Recent progress in cryoablation cancer therapy and nanoparticles mediated cryoablation. Theranostics. 2022;12:2175-2204. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 17.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Liu M, Wei AC. Advances in Surgery and (Neo) Adjuvant Therapy in the Management of Pancreatic Cancer. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2024;38:629-642. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Yu B, Shao S, Ma W. Frontiers in pancreatic cancer on biomarkers, microenvironment, and immunotherapy. Cancer Lett. 2025;610:217350. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 46.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Safyan RA, Kim E, Dekker E, Homs M, Aguirre AJ, Koerkamp BG, Chiorean EG. Multidisciplinary Standards and Evolving Therapies for Patients With Pancreatic Cancer. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2024;44:e438598. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Zheng R, Liu X, Zhang Y, Liu Y, Wang Y, Guo S, Jin X, Zhang J, Guan Y, Liu Y. Frontiers and future of immunotherapy for pancreatic cancer: from molecular mechanisms to clinical application. Front Immunol. 2024;15:1383978. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 16.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Ran L, Yang W, Chen X, Zhang J, Zhou K, Zhu H, Jin C. High-Intensity Focused Ultrasound Ablation Combined With Pharmacogenomic-Guided Chemotherapy for Advanced Pancreatic Cancer: Initial Experience. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2024;50:1566-1572. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Zhou J, Dong G, Jing X, Huang G, Wang Z, Peng M, Zhou Y, Yu X, Yu J, Han Z, Liu F, Gao H, Zhang Y, Cheng Z, Ye X, Liang P. Image-guided percutaneous microwave ablation for unresectable pancreatic cancers: A multicenter retrospective study. Eur J Radiol. 2024;181:111720. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Birrer M, Saad B, Drews S, Pradella C, Flaifel M, Charitakis E, Ortlieb N, Haberstroh A, Ochs V, Taha-Mehlitz S, Burri E, Heigl A, Frey DM, Cattin PC, Honaker MD, Taha A, Rosenberg R. Radiofrequency ablation (RFA) in unresectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma: meta-analysis & systematic review. Surg Endosc. 2025;39:141-152. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Xue K, Liu X, Xu X, Hou S, Wang L, Tian B. Perioperative outcomes and long-term survival of cryosurgery on unresectable pancreatic cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Surg. 2024;110:4356-4369. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Son H, Kim TI, Lee J, Han SY, Kim DU, Kim D, Kim GH. A Preliminary Study of a Prototype Cryoablation Needle on Porcine Livers for Pancreatic Cancer Treatment. J Clin Med. 2024;13:4998. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Kovach SJ, Hendrickson RJ, Cappadona CR, Schmidt CM, Groen K, Koniaris LG, Sitzmann JV. Cryoablation of unresectable pancreatic cancer. Surgery. 2002;131:463-464. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Shao Q, O'Flanagan S, Lam T, Roy P, Pelaez F, Burbach BJ, Azarin SM, Shimizu Y, Bischof JC. Engineering T cell response to cancer antigens by choice of focal therapeutic conditions. Int J Hyperthermia. 2019;36:130-138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 13.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 22. | Gu C, Wang X, Wang K, Xie F, Chen L, Ji H, Sun J. Cryoablation triggers type I interferon-dependent antitumor immunity and potentiates immunotherapy efficacy in lung cancer. J Immunother Cancer. 2024;12:e008386. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Zhang W, Wang Y, Zhao X, Gao W, Liu C, Si T, Yang X, Xing W, Yu H. Efficacy and Safety of CT-guided Percutaneous Cryoablation for Hepatocellular Carcinoma at High-risk Sites. Acad Radiol. 2024;31:4434-4444. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Xu K, Niu L, Yang D. Cryosurgery for pancreatic cancer. Gland Surg. 2013;2:30-39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Tao Z, Tang Y, Li B, Yuan Z, Liu FH. Safety and effectiveness of cryosurgery on advanced pancreatic cancer: a systematic review. Pancreas. 2012;41:809-811. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Nebbia M, Capretti G, Nappo G, Zerbi A. Updates in the management of postoperative pancreatic fistula. Int J Surg. 2024;110:6135-6144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 27. | Wu Y, Gu Y, Zhang B, Zhou X, Li Y, Qian Z. Laparoscopic ultrasonography-guided cryoablation of locally advanced pancreatic cancer: a preliminary report. Jpn J Radiol. 2022;40:86-93. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 28. | Nikoloudi M, Tsilika E, Kostopoulou S, Mystakidou K. Hope and Distress Symptoms of Oncology Patients in a Palliative Care Setting. Cureus. 2023;15:e38041. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Li J, Sheng S, Zhang K, Liu T. Pain Analysis in Patients with Pancreatic Carcinoma: Irreversible Electroporation versus Cryoablation. Biomed Res Int. 2016;2016:2543026. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/