Published online Jan 27, 2026. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v18.i1.114291

Revised: November 2, 2025

Accepted: December 9, 2025

Published online: January 27, 2026

Processing time: 131 Days and 23.6 Hours

This report describes the development of schizophrenia in a 63-year-old female patient approximately six months after undergoing liver transplantation. The patient exhibited no previous indications of psychiatric conditions and did not have any familial background of schizophrenia.

This particular case serves as an illustration of the intricate interaction of various elements, such as the liver transplantation process, surgical trauma, intraoperative narcosis, and immunosuppression, which may potentially contribute to the onset of schizophrenia. This report examines the clinical trajectory, diagnostic assess

This report emphasizes the significance of identifying and managing psychiatric issues during the post-transplant phase, highlighting potential underlying mecha

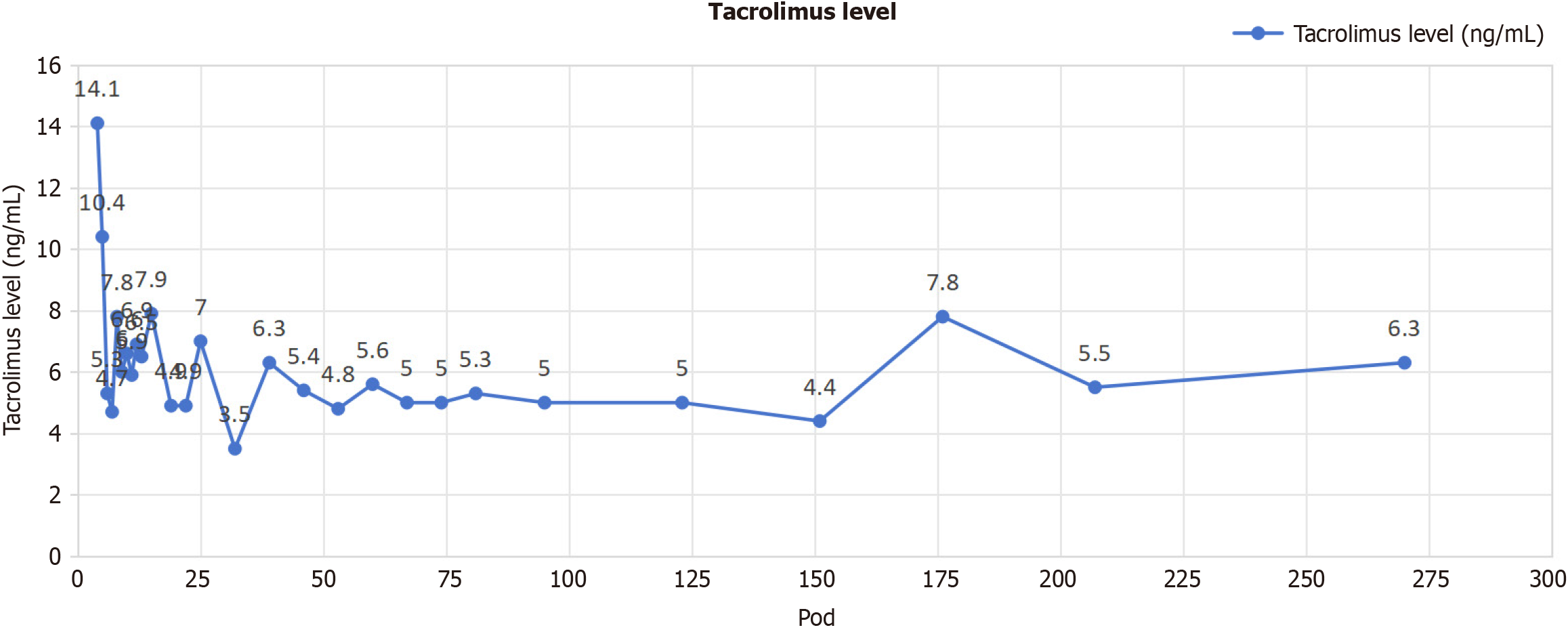

Core Tip: We present the inaugural instance of new-onset schizophrenia occurring within one year post-liver transplantation in a 63-year-old female patient. The diagnosis was determined using structured interviews, sequential Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale scores, and thorough exclusion of metabolic, viral, and toxic variables. Following the commencement of antipsychotic treatment alongside low-dose tacrolimus and mycofenolate mofetil immunosuppression, the patient showed rapid improvement of symptoms, indicating calcineurin-inhibitor neurotoxicity as a direct catalyst; and surgical stress and anesthesia likely exacerbated individual vulnerability. This instance highlights the necessity for proactive neuropsychiatric monitoring and tailored immunosuppression in liver transplant recipients.

- Citation: Qin JW, Wu JC, Zheng H, Qi C, Zhu ZB, Li XF, Wang N, Yuan XD, Xu ZJ, Wu W, Zhang SG, Nashan B. De novo schizophrenia after liver transplantation: A case report. World J Hepatol 2026; 18(1): 114291

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v18/i1/114291.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v18.i1.114291

Schizophrenia is a highly debilitating and enduring psychiatric condition marked by the presence of hallucinations, de

In this report, we describe a 63-year-old female patient who developed symptoms of schizophrenia approximately six months after liver transplantation. The temporal correlation between the transplantation operation and the subsequent manifestation of psychiatric symptoms suggests the potential existence of a causal connection. Based on the available information, this is a rare case in which the onset of schizophrenia was observed subsequent to liver transplantation, potentially linked to surgical stress[5], intraoperative narcosis[6], and the administration of immunosuppressive agents[7-10]. It is imperative to comprehend the potential correlation between liver transplantation and the onset of schizophrenia in order to ensure the best patient care. Enhanced consciousness among healthcare practitioners engaged in the field of transplantation, encompassing surgeons, anesthesiologists, psychiatrists, and transplant coordinators, has the potential to expedite the prompt recognition, timely intervention, and suitable implementation of management approaches for patients encountering psychiatric complications.

A 63-year-old woman who underwent liver transplantation for primary biliary cirrhosis presented with persecutory delusions and auditory hallucinations six months post-operation.

Six months ago, the patient received an orthotopic liver transplantation due to primary biliary cirrhosis and was placed on a long-term immunosuppressive protocol with tacrolimus as the cornerstone, following an uncomplicated pos

The patient had no history of diabetes, hypertension, heart disease, tuberculosis, chronic hepatitis B or hepatitis C infection, cerebrovascular disease, psychiatric disorders, or any other systemic diseases.

The patient did not have a history of smoking or alcohol consumption, and there was no family history of similar di

Physical examination revealed altered mental status with restlessness and uncooperativeness. Respiration was stable. The patient presented with a sallow complexion but showed no evidence of jaundice in the skin or sclerae. The abdomen was mildly distended, with no edema in the lower extremities. No hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, or significant ascites was detected.

The laboratory results indicated that white blood cells, red blood cells, hemoglobin, platelets, blood electrolytes, glucose, urea, creatinine, total bilirubin, alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, alkaline phosphatase, albumin, blood ammonia, C-reactive protein, toxoplasmosis and other infections including syphilis, human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis viruses, varicella virus and parvovirus B19, rubella, cy

Brain magnetic resonance imaging revealed no acute pathology.

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) criteria were confirmed using the structured clinical interview for DSM-5-revised version, conducted independently by two psychiatrists; criteria A-D and F were met. Initial Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale scores were as follows: Positive sub-score 32, negative sub-score 24, general psychopathology 46, total 102 (severe range). Plus, Clinical Global Impression-Severity Scale 6 (critically sick). No fundamental characteristics of delirium, such as variable attention and sleep-wake reversal, were detected in the patient[11]. Based on the DSM-5 criteria, a diagnosis of schizophrenia was established. The patient met the criteria for hallucinations, delusions, disorganized speech, and negative symptoms. Prior to the initiation of antipsychotic therapy, the subsequent assessments were conducted: The laboratory results indicated that white blood cells, red blood cells, hemoglobin, platelets, blood electrolytes, glucose, urea, creatinine, total bilirubin, aminotransferase, aspartate amino

Treatment for schizophrenia was promptly initiated. The patient was prescribed an antipsychotic medication (olanzapine and quetiapine fumarate) at a low dose, which was gradually increased to achieve symptom alleviation [olanzapine was started at 5 mg quaque nocte (qn) and increased by 5 mg every 3 days to 15 mg qn; quetiapine was started at 50 mg qn, and titrated to 200 mg qn]. Since neither olanzapine nor quetiapine exhibit cytochrome P450 inhibitory or inducing properties, their administration is not expected to have an impact on the blood concentration of tacrolimus[12-14]. Regular psy

The patient had partial improvement in psychotic symptoms following the initiation of antipsychotic treatment. Auditory hallucinations decreased in frequency and intensity, and paranoid ideation became less pronounced. Disorganized speech and negative symptoms showed limited response to treatment. The patient is currently undergoing psychiatric care and will continue to be monitored for any changes in symptomatology or adverse medication effects. Throughout the entire psychiatric treatment duration, the patient’s liver function was consistently monitored and maintained within normal parameters.

Liver transplantation is a multifaceted medical operation that entails surgical intervention, potentially leading to both physical and psychological strain for the recipient. Neuropsychiatric symptoms have been linked to surgical trauma, including those related to disease process, fear of surgery, anesthetic drugs, drug interactions, tissue damage, and body responses to postoperative medications[6,15,16]. The following immunological response and inflammation may po

Immunosuppressive drugs, such as tacrolimus and mycofenolate mofetil (MMF), are employed in the context of organ transplantation to mitigate the risk of graft vs host disease. However, it has been found that there is an association between certain pharmaceutical substances and adverse psychological effects. The calcineurin inhibitors (CNIs) en

When assessing the incidence of schizophrenia after liver transplantation, it is imperative to consider individual predisposing variables. The potential impact of inherited predisposition and pharmacogenetic variations on an indi

This particular case underscores the necessity of employing a multidisciplinary methodology when addressing individuals who experience psychological issues subsequent to undergoing liver transplantation. The recognition and addressing of potential contributory factors necessitate a close coordination among transplant surgeons, hepatologists, anesthesiologists, and psychiatrists. The timely recognition and intervention of a condition are of utmost importance in order to maximize results and customize treatment strategies according to the unique requirements of each individual.

A systematic search of PubMed utilizing the terms (“liver transplantation” OR “hepatic transplant”) AND (“schizophrenia” OR “schizophreniform disorder”) AND (“new-onset” OR “de-novo”) resulted in the identification of a singular previously documented case of psychosis subsequent to liver transplantation, involving a female who experienced an episode of schizophrenia 20 years post-transplantation[26]. This case report is the first instance of new schizophrenia in a patient subsequent to liver transplantation within a brief timeframe worldwide. It offers valuable insights into the potential correlation between liver transplantation, surgical trauma, intraoperative narcosis, immunosuppressive medications, and the onset of schizophrenia. However, it is crucial to recognize the inherent limitations of a solitary case study. Additional study is necessary, particularly in the form of larger-scale studies and prospective investigations, in order to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the underlying mechanisms involved, determine the prevalence of these events, and develop evidence-based strategies for managing them.

In summary, this case report underscores the probable correlation between liver transplantation and the eventual onset of schizophrenia. Potential risk factors that necessitate careful evaluation include surgical trauma, intraoperative narcosis, and the use of immunosuppressive drugs. Gaining a thorough comprehension of these intricate relationships would enhance the ability to promptly identify, implement specific interventions, and enhance the outcomes for individuals who encounter neuropsychiatric issues after liver transplantation. Further investigation is warranted to broaden our under

| 1. | Jauhar S, Johnstone M, McKenna PJ. Schizophrenia. Lancet. 2022;399:473-486. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 662] [Article Influence: 165.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Bugallo-Carrera C, Facal D, Domínguez-Lenogue C, Álvarez-Vidal V, Gandoy-Crego M, Caamaño-Ponte J. Neuropsychiatric Symptoms after Liver Transplantation in a 65-Year-Old Male Patient. Brain Sci. 2022;12:1721. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Te HS. Altered mental status after liver transplant. Clin Liver Dis (Hoboken). 2017;10:36-41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Mappin-Kasirer B, Hoffman L, Sandal S. New-onset Psychosis in an Immunosuppressed Patient With Kidney Transplantation: An Educational Case Report. Can J Kidney Health Dis. 2020;7:2054358120947210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ozyurtkan MO, Yildizeli B, Kuşçu K, Bekiroğlu N, Bostanci K, Batirel HF, Yüksel M. Postoperative psychiatric disorders in general thoracic surgery: incidence, risk factors and outcomes. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2010;37:1152-1157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Przybylo HJ, Przybylo JH, Todd Davis A, Coté CJ. Acute psychosis after anesthesia: the case for antibiomania. Paediatr Anaesth. 2005;15:703-705. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Draper HM. Depressive disorder associated with mycophenolate mofetil. Pharmacotherapy. 2008;28:136-139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Løhde LW, Bentzon A, Kornblit BT, Roos P, Fink-Jensen A. Possible Tacrolimus-Related Neuropsychiatric Symptoms: One Year After Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation: A Case Report. Clin Med Insights Case Rep. 2022;15:11795476221087053. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | de Sousa Arantes Ferreira G, Conde Watanabe AL, de Carvalho Trevizoli N, Felippe Jorge FM, Ferreira Figueira AV, de Fatima Couto C, Viana de Lima L, Liduario Raupp DR. Tacrolimus-Associated Psychotic Disorder: A Report of 2 Cases. Transplant Proc. 2020;52:1350-1353. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Nogueira JM, Freire MJ, Nova VV, Jesus G. When Paranoia Comes with the Treatment: Psychosis Associated with Tacrolimus Use. Case Rep Nephrol Dial. 2021;11:241-246. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Howard R, Rabins PV, Seeman MV, Jeste DV. Late-onset schizophrenia and very-late-onset schizophrenia-like psychosis: an international consensus. The International Late-Onset Schizophrenia Group. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:172-178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 490] [Cited by in RCA: 349] [Article Influence: 13.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Grimm SW, Richtand NM, Winter HR, Stams KR, Reele SB. Effects of cytochrome P450 3A modulators ketoconazole and carbamazepine on quetiapine pharmacokinetics. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;61:58-69. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Callaghan JT, Bergstrom RF, Ptak LR, Beasley CM. Olanzapine. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profile. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1999;37:177-193. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 372] [Cited by in RCA: 392] [Article Influence: 14.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 14. | Yuan X, Qin J, Zheng H, Qi C, Guo Y, Zhu Z, Wu W, Xu Z, Li X, Wang N, Chai X, Xie Y, Tao X, Liu H, Liu W, Liu G, Ye L, Deng K, Li Y, Ji X, Hou C, Yao Z, Huang Q, Song R, Zhang S, Wang J, Liu L, Nashan B. Enhanced recovery after liver transplantation-a prospective analysis focusing on quality assessment. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr. 2025;14:423-441. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Hackett TP, Weisman AD. Psychiatric management of operative syndromes. I. The therapeutic consultation and the effect of noninterpretive intervention. Psychosom Med. 1960;22:267-282. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Christodoulou C, Fineti K, Douzenis A, Moussas G, Michopoulos I, Lykouras L. Transfers to psychiatry through the consultation-liaison psychiatry service: 11 years of experience. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2008;7:10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Crabtree GR. Calcium, calcineurin, and the control of transcription. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:2313-2316. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 345] [Cited by in RCA: 342] [Article Influence: 13.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Anghel D, Tanasescu R, Campeanu A, Lupescu I, Podda G, Bajenaru O. Neurotoxicity of immunosuppressive therapies in organ transplantation. Maedica (Bucur). 2013;8:170-175. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Wijdicks EF. Neurotoxicity of immunosuppressive drugs. Liver Transpl. 2001;7:937-942. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 157] [Cited by in RCA: 158] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Balderramo D, Prieto J, Cárdenas A, Navasa M. Hepatic encephalopathy and post-transplant hyponatremia predict early calcineurin inhibitor-induced neurotoxicity after liver transplantation. Transpl Int. 2011;24:812-819. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Piotrowski PC, Lutkowska A, Tsibulski A, Karczewski M, Jagodziński PP. Neurologic complications in kidney transplant recipients. Folia Neuropathol. 2017;55:86-109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Sikavi D, McMahon J, Fromson JA. Catatonia Due to Tacrolimus Toxicity 16 Years After Renal Transplantation: Case Report and Literature Review. J Psychiatr Pract. 2019;25:481-484. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Bechstein WO. Neurotoxicity of calcineurin inhibitors: impact and clinical management. Transpl Int. 2000;13:313-326. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Lipsky JJ. Mycophenolate mofetil. Lancet. 1996;348:1357-1359. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 230] [Cited by in RCA: 233] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Rushlow WJ, Seah C, Sutton LP, Bjelica A, Rajakumar N. Antipsychotics affect multiple calcium calmodulin dependent proteins. Neuroscience. 2009;161:877-886. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Anraku Y, Akaho R, Matsui S, Sannomiya A, Fuchinoue S, Nishimura K. Graft Loss Following Onset of Schizophrenia Long After Liver Transplantation. Int Med Case Rep J. 2020;13:101-104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/