Published online Jan 27, 2026. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v18.i1.114366

Revised: November 3, 2025

Accepted: December 15, 2025

Published online: January 27, 2026

Processing time: 132 Days and 18.8 Hours

Patients with decompensated cirrhosis frequently experience severe psychological distress, anxiety, and depression, yet psychological support is often fragmented in conventional care.

To investigate the effect of interdisciplinary team scheduling on psychological outcomes in decompensated cirrhosis.

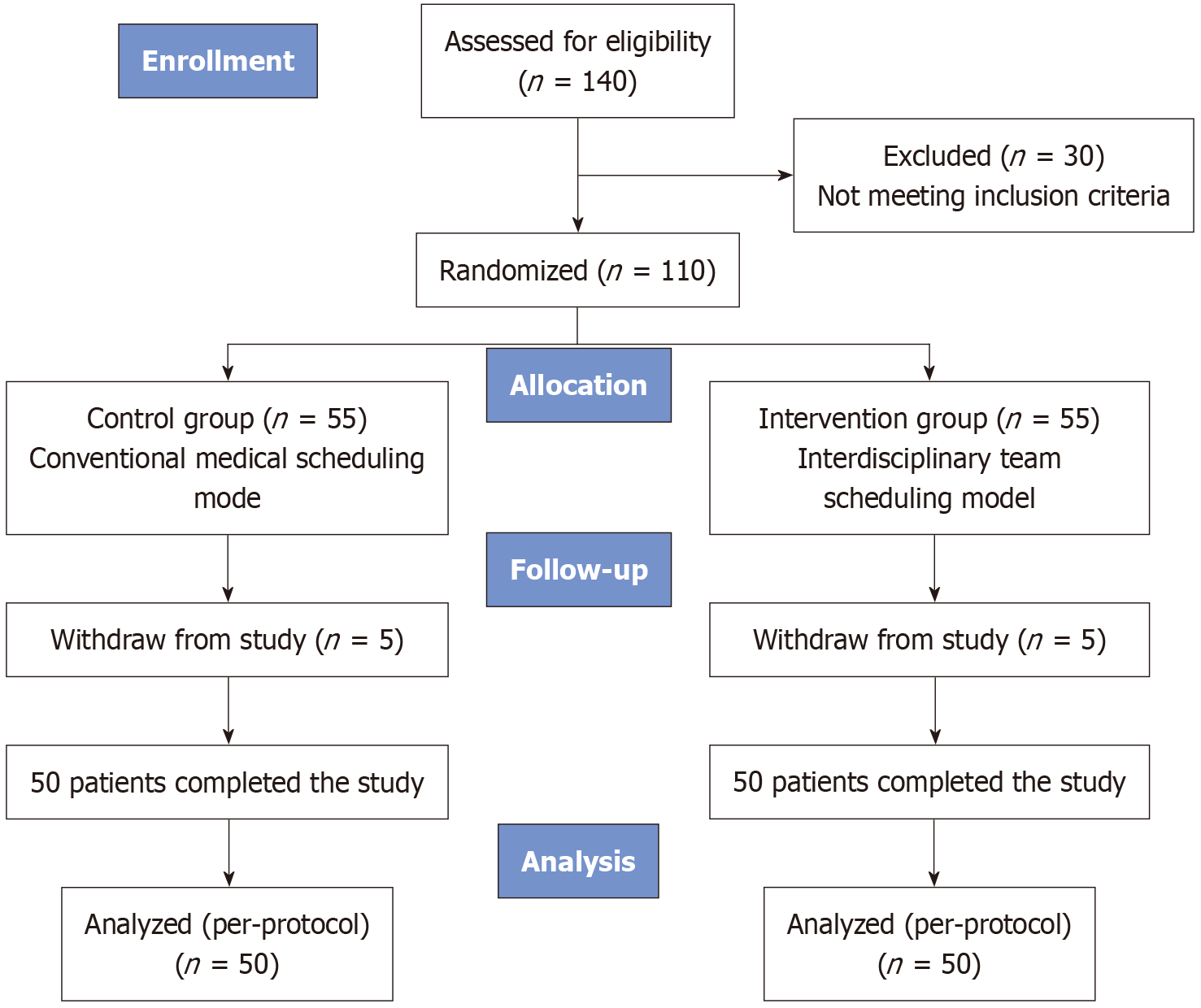

A randomized, single-blind, single-center trial was conducted from January 2022 to December 2024 in Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region. A total of 110 patients with decompensated cirrhosis (Distress Thermometer ≥ 4) were randomized to interdisciplinary team scheduling (n = 55) or conventional scheduling (n = 55). Psychological distress, anxiety, depression, and quality of life were assessed using the Distress Thermometer, Self-Rating Anxiety Scale, Self-Rating Depression Scale, and World Health Organization Quality of Life 100 questionnaire, respec

Following the intervention, the interdisciplinary group achieved significantly lower psychological distress [3 (2-3) vs 3 (3-4)], anxiety (41.65 ± 4.29 vs 46.38 ± 4.18), and depression scores (45.79 ± 3.25 vs 50.14 ± 3.69) compared with the control group (all P < 0.05). Quality of life scores also improved significantly in the physical, psychological, and social domains (P < 0.05).

The interdisciplinary team scheduling model effectively alleviates psychological symptoms and enhances quality of life among patients with decompensated cirrhosis. This model addresses unmet psychosocial needs through early, continuous, and collaborative care, providing a practical framework for integrating psychological support into chronic liver disease management.

Core Tip: This randomized controlled trial evaluated an innovative interdisciplinary team scheduling model integrating physicians, nurses, and psychologists for patients with decompensated cirrhosis. Embedding psychological consultation and narrative nursing into daily clinical routines significantly reduced psychological distress, anxiety, and depression while improving quality of life and patient satisfaction. Compared with conventional medical-nursing scheduling, this model provided earlier and more comprehensive psychological care. The findings highlight the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration in bridging gaps in psychosocial support and offer a novel, practical approach for chronic disease management in cirrhosis.

- Citation: Xu WY, Li YQ, Wei XP, Qin HP, Feng LF. Evaluation of the impact of an interdisciplinary team scheduling model on psychological outcomes in patients with decompensated cirrhosis. World J Hepatol 2026; 18(1): 114366

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v18/i1/114366.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v18.i1.114366

Decompensated cirrhosis represents a growing global health burden, affecting approximately 2 million adults to 8 million adults in the United States. Its pathophysiological features (e.g., portal hypertension, hepatic encephalopathy) result in frequent hospitalizations, complex clinical management, and substantial psychological strain. The one-year mortality rate reaches 43.8% in patients with two decompensated complications[1]. Psychiatric comorbidities are highly prevalent in this population: Anxiety affects 25%-45%, and depression 29%-72% of cirrhotic patients[2]. These symptoms often ex

Despite this high burden, psychological care for cirrhosis patients remains fragmented and reactive. In most clinical settings, care teams consist of only physicians and nurses; psychological consultation is typically initiated only after overt symptoms emerge, often resulting in delayed and disjointed support. To address this gap, emerging care models advocate embedding psychological support into routine clinical workflows. One such model is the interdisciplinary team scheduling approach, which integrates psychologists into daily care activities to deliver early, proactive, and continuous psychosocial interventions.

The interdisciplinary team scheduling model is based on the biopsychosocial medical theory by Fricchione[6], em

This study aimed to construct a “physiological-psychological-narrative” triadic intervention model and evaluate its clinical effects in patients with decompensated cirrhosis. Specifically, we conducted a randomized controlled trial to assess whether this interdisciplinary team scheduling model improves psychological distress, anxiety, depression, and quality of life, compared to conventional physician-nurse scheduling. We hypothesized that embedding narrative-based psychological support into routine care would yield superior patient-reported outcomes and offer a scalable solution for psychosocial integration in chronic disease management.

The purpose of this intervention was to improve self-management and self-efficacy in patients with decompensated cirrhosis through a randomized, single-blind, single-center trial. From January 2022 to December 2024, 110 inpatients with decompensated cirrhosis and Distress Thermometer (DT) score ≥ 4 admitted to the gastroenterology department of a tertiary hospital in Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region were recruited.

Randomization was performed using a random number table by an independent statistician uninvolved in-patient care or outcome assessment. Two associate chief nurses, responsible for pre-intervention and post-intervention evaluations, were blinded to group assignments. Given the nature of the intervention, patients and care providers were not blinded; however, patients were unaware of the expected benefits of either model to reduce expectancy bias. A total of 55 patients were assigned to the interdisciplinary team scheduling group and 55 to the conventional scheduling (control) group.

This study enrolled patients with decompensated cirrhosis who met all of the following inclusion criteria: (1) Age ≥ 18 years; (2) Diagnosis of decompensated cirrhosis according to the cirrhosis diagnostic criteria proposed in the 13th edition of Practical Internal Medicine[10]; and (3) Consent to participate in this study. Exclusion criteria were: (1) Patients with language communication disorders; (2) Patients with cognitive impairment; (3) Expected survival < 3 months; and (4) History of prior systematic psychological intervention. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Red Cross Hospital of Yulin City (Approval No. 2021-K001-01). All patients provided informed consent after understanding the study procedures.

Sample size was calculated using G*Power 3.1. Based on literature, the effect size was set at 0.77, α = 0.05, and power = 0.90, yielding a minimum of 36 patients per group. Allowing for a 20% dropout rate, a total of 110 patients (55 in the intervention group and 55 in the control group) were planned for inclusion. A random number generator was used to produce random numbers in a 1:1 ratio. Participants with odd random numbers were allocated to group A, and those with even random numbers to group B; the specific assignment was concealed from the corresponding author (group A designated as the intervention group, group B as the control group).

This study is grounded in the biopsychosocial medical model, integrating narrative medicine and prehabilitation psychological interventions to construct a “physiological-psychological-narrative” closed-loop intervention chain[11]. Patients with decompensated cirrhosis commonly experience high rates of anxiety, depression, and a dual psychological burden of “chronic stress-acute fear”, necessitating multidimensional interventions. Through interdisciplinary collaboration (physicians, nurses, psychologists), physiological management is optimized and psychologists are embedded into routine scheduling to enable early psychological intervention. Narrative therapy is employed to guide patients in reconstructing illness perceptions[12], thereby alleviating depressive symptoms; concurrently, prehabilitation interventions enhance patients’ coping abilities for treatment-related stress, breaking the “psychological distress-somatic deterioration” cycle. Under this theoretical framework, the closed-loop intervention chain aims to strengthen patients perceived control over symptoms, improve self-management and quality of life, provide a theoretical basis for chronic disease management, reduce medical burden, and enhance survival outcomes.

Establishment of a triadic medical-nursing-psychological scheduling management team: A dedicated interdisciplinary team was formed, comprising: 2 associate chief physicians, 3 attending physicians, 1 nationally certified level-2 psychological counselor, 1 chief nurse (head nurse), 2 associate chief nurses, 3 charge nurses, and 3 staff nurses. Physicians were responsible for diagnosis and medical treatment. The psychological counselor provided personalized psychological consultation and care addressing patients’ distress factors. Two associate chief nurses, after training, were responsible for assessing psychological distress, anxiety, depression, and quality of life in patients with decompensated cirrhosis; they did not participate directly in treatment or psychological nursing. Six charge nurses and staff nurses were responsible for routine treatment care and general psychological support.

The psychological counselor received 9 hours of structured face-to-face training (three 3-hour sessions) conducted by two senior faculty members specializing in narrative nursing and psychosocial care. The training was based on the narrative therapy framework proposed by White and Epston and included detailed instruction on the five core tech

Intervention group - implementation of the triadic medical-nursing-psychological scheduling model: On the basis of the original medical-nursing scheduling, from Monday to Friday during daytime an additional psychological con

Externalization: Separate the person from the disease, enabling the patient to focus on the disease or problem and increasing their sense of control over it. For example, for a patient “Guan” with cirrhosis complicated by hepatocellular carcinoma, based on the psychological state “fear of death” at that time, the issue was named “fear of death”, thereby separating patient Guan from the disease. Concurrently, this shifts healthcare providers’ focus from the disease and nursing tasks to the patient as an individual.

Deconstruction: Explore the sociocultural context underlying the problem or behavior. For example, if patient Guan is repeatedly readmitted because family cultural attitudes have shaped him to feel useless and near death, this under

Re-authoring: Based on the omitted fragments and exceptions identified through the “externalizing conversation”, alter the storyline. For instance, identify the “exception” that patient Guan accompanies and educates his daughter, who is a top student in a key high school class; praise and affirm his contribution to his daughter, guiding him to continue accompanying and educating her, forming a new narrative strand in which his daughter is admitted to a good university.

External witnesses: Use others’ “perspectives” and “statements” to strengthen the patient’s empowerment. For example, presenting patient Guan with a certificate of recognition in the presence of all medical staff makes the department’s entire staff serve as external witnesses, making the change real and reinforcing the behavior.

Therapeutic documents: Use artifacts to reinforce beliefs and achieve genuine therapeutic effect. For instance, the certificate awarded to patient Guan can serve as a therapeutic document, helping him continuously reinforce the belief that he has control over his own destiny.

In summary, narrative nursing methods, through multidimensional operations, aim to help patients re-examine and resolve life issues (Simone[8]), enhance self-identity and coping ability for disease, and promote recovery and psychological health.

Two trained associate chief nurses specifically assessed newly admitted patients with decompensated cirrhosis (di

Inclusion and exclusion criteria were strictly followed to minimize selection bias and ensure data comparability among study subjects. A database was established in Excel using double-entry: All data were entered in pairs and consistency checked. Any inconsistent entries were verified until 100% consistency was achieved.

A questionnaire designed by the research team was used to collect patients’ demographic and clinical characteristics, including sex, age, marital status, type of insurance coverage, and Child-Pugh score for liver function. Clinical factors included cirrhosis duration, presence of pain, and sleep disturbances, which were assessed based on patient self-report at admission. The selection of these variables was informed by a prior cross-sectional survey conducted by the authors involving 300 patients with decompensated cirrhosis. That study identified marital status, economic burden, method of healthcare payment, disease duration, pain, and sleep problems as key contributors to psychological distress in this population. Accordingly, these variables were incorporated into the baseline comparison of general information between groups in the present study.

DT serves as a rapid screening tool for identifying psychological distress. We used the Chinese version of the DT[13]. The reliability and validity of this scale have been verified in multiple countries and regions, with a diagnostic cutoff ≥ 4 points[14]. The DT comprises two parts: (1) The DT scale, ranging from 0 (no distress) to 10 (extreme distress) on an 11-point scale, instructing patients to mark their experienced distress level over the past week; and (2) A problem checklist of 39 items covering five domains: Practical problems, family problems, emotional problems, physical problems, and spiritual/religious concerns. Participating patients respond “yes” or “no” to each of the 39 specific items; the spiritual/religious domain contains no specific items. Scores of 1-3 indicate mild distress, 4-6 moderate distress, 7-9 severe distress, and 10 extreme distress. At the cutoff of 4 points, sensitivity and specificity are 0.80 and 0.70, respectively.

Anxiety and depression were assessed using the Self-Rating Anxiety Scale and Self-Rating Depression Scale[15]. These scales comprehensively, accurately, and rapidly reflect the respondent’s anxiety and depression symptoms, severity, and subsequent changes. Scores below 50 are considered within the normal range; scores of 50-59 indicate mild anxiety or depression; 60-69 indicate moderate anxiety or depression; and scores ≥ 70 indicate severe anxiety or depression. The Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient for these scales’ ranges from 0.80 to 0.90.

Quality of life was measured using the World Health Organization Quality of Life 100 (WHOQOL-100) questionnaire scale (Skevington et al[16]). This instrument has been applied in China among the general population and patients with chronic diseases; the Chinese version demonstrates good reliability and validity. The scale comprises six domains - physical, psychological, independence, social relationships, environment, and spirituality/religion/personal beliefs - encompassing 24 facets, plus one item evaluating overall health status and overall quality of life. The total score ranges up to 100 points, with higher scores indicating better quality of life.

Patient satisfaction with caring nursing practices was evaluated using the caring nursing work satisfaction questionnaire revised by Jiang et al[17]. The instrument contains 30 nursing behavior items, each rated on a five-point scale from 5 to 1, representing “very satisfied”, “satisfied”, “neutral”, “dissatisfied”, and “very dissatisfied”, respectively. Content validity index assessed by peer experts is 0.82, and the questionnaire’s reliability coefficient is 0.85. Higher scores denote greater patient satisfaction.

A dedicated, independent psychological consultation room was prepared according to design requirements for counseling spaces[18]. The room is quiet and soundproof, with suitable lighting and harmonious color tones, primarily light blue, light yellow, and light green. Furnishings include a desk with a computer, a filing cabinet, two chairs, and a sofa. The overall environment aims to make patients feel warm, welcoming, and relaxed.

The psychological consultation shift is executed by a counselor holding a national level-2 psychological counselor certificate with rich clinical counseling experience. Working hours are Monday to Friday, 08:00 to 17:30. At 08:00 each morning, the counselor participates in the handover meeting with physicians and nurses. Subsequently, for patients with DT score ≥ 4 admitted to the intervention group, personalized psychological interventions are provided based on assessment results and the DT problem checklist, primarily employing narrative nursing methods. Narrative nursing has been demonstrated to facilitate emotional regulation in oncology patients[19]. Its five core techniques are externalization, deconstruction, re-authoring, external witnesses, and therapeutic documents.

From January 2022 to December 2024, for all patients in both the intervention and control groups, pre-intervention and post-intervention assessments of psychological distress, anxiety/depression scores, and quality of life scores were collected by two associate chief nurses blinded to group allocation. Data were cross-checked by two individuals to ensure completeness and accuracy of recorded information (Figure 1).

Data were entered into SPSS version 17.0 statistical software, with double verification of entries. Continuous variables conforming to a normal distribution were expressed as mean ± SD and analyzed using independent-samples t-tests; non-normally distributed continuous variables were expressed as median (P25-P75) and analyzed using nonparametric tests; categorical variables were described by n (%) and analyzed using χ2 tests. A two-sided P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Initially, 55 patients were enrolled in each group. During the study, 10 patients were lost to follow-up (5 in the intervention group and 5 in the control group), yielding a loss rate of 9.09%. Ultimately, 50 patients in the experimental group and 50 patients in the control group completed the study. There were no statistically significant differences in demographic characteristics between the two groups (P > 0.05), indicating comparability (Table 1).

| Variable | Intervention group (n = 50) | Control group (n = 50) | Test statistic | P value |

| Sex | χ2 = 1.190 | 0.275 | ||

| Male | 40 (80.00) | 44 (88.00) | ||

| Female | 10 (20.00) | 6 (12.00) | ||

| Age (years) | 51.62 ± 9.17 | 54.98 ± 8.76 | t = -1.864 | 0.065 |

| Liver function grade (Child-Pugh score) | Z = -0.157 | 0.875 | ||

| Grade A | 11 (22.00) | 13 (26.00) | ||

| Grade B | 29 (58.00) | 26 (52.00) | ||

| Grade C | 10 (20.00) | 11 (22.00) | ||

| Marital status | χ2 = 0.332 | 0.564 | ||

| Married | 42 (84.00) | 44 (88.00) | ||

| Widowed/divorced | 8 (16.00) | 6 (12.00) | ||

| Medical payment method | Z = -0.923 | 0.356 | ||

| Urban medical insurance | 8 (16.00) | 12 (24.00) | ||

| Rural medical insurance | 36 (72.00) | 33 (66.00) | ||

| Self-pay | 6 (12.00) | 5 (10.00) | ||

| Duration of cirrhosis (years) | 8.32 ± 3.43 | 8.34 ± 3.37 | t = -0.029 | 0.977 |

| Presence of pain | χ2 = 0.367 | 0.545 | ||

| Yes | 30 (60.00) | 27 (54.00) | ||

| No | 20 (40.00) | 23 (46.00) | ||

| Presence of sleep problems | χ2 = 0.407 | 0.523 | ||

| Yes | 35 (70.00) | 32 (64.00) | ||

| No | 15 (30.00) | 18 (36.00) |

Comparison of psychological distress, anxiety, and depression scores between groups: At baseline (upon admission), there were no statistically significant differences between the intervention and control groups in DT scores, Self-Rating Anxiety Scale scores, or Self-Rating Depression Scale scores (P > 0.05). After the intervention, the intervention group demonstrated significantly greater improvements in distress, anxiety, and depression scores compared with the control group (P < 0.05; Table 2).

| Group | n | Psychological distress score | Anxiety score | Depression score | |||

| Pre-intervention | Post-intervention | Pre-intervention | Post-intervention | Pre-intervention | Post-intervention | ||

| Intervention | 50 | 4 (4-5) | 3 (2-3) | 47.95 ± 5.33 | 41.65 ± 4.29 | 53.96 ± 4.82 | 45.79 ± 3.25 |

| Control | 50 | 4 (4-5) | 3 (3-4) | 48.54 ± 4.23 | 46.38 ± 4.18 | 53.32 ± 4.47 | 50.14 ± 3.69 |

| Z/t | Z = -0.807 | Z = -5.771 | t = -0.618 | t = -5.583 | t = 0.677 | t = -6.25 | |

| P value | 0.420 | 0.000 | 0.538 | 0.000 | 0.500 | 0.000 | |

Comparison of quality of life scores pre-intervention and post-intervention: Before the intervention, there was no statistically significant difference in WHOQOL-100 quality of life scores between the two groups (P > 0.05). Following the intervention, the intervention group showed significantly higher quality of life scores than the control group (P < 0.05; Table 3).

| Group (n = 5) | Physiological domain | Psychological domain | Independence domain | Social relationships domain | Environment domain | Spiritual support/religion/personal belief | Overall quality of life score | |||||||

| Pre-intervention | Post-intervention | Pre-intervention | Post-intervention | Pre-intervention | Post-intervention | Pre-intervention | Post-intervention | Pre-intervention | Post-intervention | Pre-intervention | Post-intervention | Pre-intervention | Post-intervention | |

| Experimental group | 11.27 ± 1.65 | 14.40 ± 1.17 | 12.16 ± 1.52 | 14.57 ± 1.09 | 11.77 ± 1.59 | 14.08 ± 0.89 | 12.56 ± 1.05 | 13.15 ± 1.36 | 12.98 ± 1.37 | 13.34 ± 1.13 | 12 (12-13) | 13 (12-14) | 10 (10-12) | 12 (12-13) |

| Control group | 11.49 ± 1.43 | 12.37 ± 1.20 | 12.41 ± 1.19 | 13.05 ± 1.45 | 11.71 ± 1.61 | 12.11 ± 1.64 | 12.11 ± 1.29 | 12.25 ± 1.29 | 13.03 ± 0.97 | 13.13 ± 1.05 | 12 (11-13) | 12 (11-13) | 10 (9-12) | 10 (10-12) |

| Z/t | t = -0.711 | t = 8.559 | t = -0.912 | t = 5.908 | t = 0.191 | t = 7.495 | t = 0.968 | t = 3.397 | t = -0.249 | t = 0.990 | Z = -0.813 | Z = -2.744 | Z = -0.443 | Z = -6.330 |

| P value | 0.479 | 0 | 0.364 | 0 | 0.849 | 0 | 0.337 | 0.001 | 0.804 | 0.325 | 0.416 | 0.006 | 0.658 | 0 |

Comparison of caring nursing work satisfaction between groups: At baseline, there was no statistically significant difference in caring nursing work satisfaction scores between the intervention and control groups (P > 0.05). After the intervention, patient satisfaction with caring nursing practices was significantly higher in the intervention group compared with the control group (P < 0.05; Table 4).

| Group | Sample size | Pre-intervention | Post-intervention |

| Experimental group | 50 | 112.90 ± 6.24 | 144.28 ± 4.43 |

| Control group | 50 | 113.50 ± 7.26 | 125.78 ± 8.39 |

| t value | -0.44 | 14.23 | |

| P value | 0.66 | 0.001 |

This study was a randomized controlled trial designed to evaluate the clinical effects of an interdisciplinary team scheduling model on improving the psychological distress index, alleviating anxiety and depressive symptoms, and enhancing quality of life in patients with decompensated cirrhosis. Our results support the validity of both hypotheses: That the interdisciplinary team scheduling model is an effective intervention to improve patients’ psychological distress index, relieve anxiety and depression symptoms, and enhance quality of life, with efficacy surpassing that of the tra

Our findings align closely with prior literature. Zhang et al[20] demonstrated that patients with decompensated cirrhosis endure substantial psychological distress and a marked decline in quality of life; they emphasized that beyond monitoring clinical indicators, providing psychological support early in the disease course is key to improving disease-related quality of life. In our study, by integrating psychological intervention with medical and nursing care through an interdisciplinary scheduling model, we effectively alleviated patients’ anxiety and depression, consistent with Scriney et al[7] who concluded that “early psychological support is critical for improving quality of life”. Furthermore, Chu

The effects of the interdisciplinary scheduling model can be attributed to the synergistic action of multidimensional strategies. First, team collaboration enabled dynamic integration of psychological intervention with the medical process. Zhang et al[25] demonstrated that humane nursing significantly improved nutritional status and psychological stress in colorectal cancer patients; similarly, in our model the psychological counselor adjusted counseling approaches according to the treatment stage (e.g., for patients reluctant to face their disease, counseling modified their attitude, and, with family and staff witness, certificates were awarded to reinforce positive behavior), reflecting a parallel logic. Second, the application of narrative nursing and positive psychological priming enhanced patients’ sense of control over their illness. Zhu et al[26] showed that strength-based narrative therapy can improve depressive symptoms and quality of life in older adults; our study likewise found that, through the “person is not the disease” narrative framework, patients progressively rebuilt confidence in life, with significant improvements in the independence and social relationship domains of quality of life. Finally, flexible scheduling ensured continuity of support. In traditional scheduling models, information gaps can delay psychological assessment (e.g., failure to identify patient anxiety promptly), whereas our model’s seamless coordination among medical, nursing, and psychological staff prevented this issue, consistent with Zhang et al[20] advocating for “continuous psychological support”. These strategies not only alleviated psychological distress in the short term but may also drive long-term improvements in quality of life by enhancing treatment adherence and fostering a positive attitude toward life.

This study offers three practical implications for clinical nursing. First, it is essential to promote the interdisciplinary scheduling model. Zou et al[24] emphasized that quality of life in liver disease patients is affected by both physical and psychological burdens; our model’s multidisciplinary collaboration (e.g., physician-nurse-psychologist team) delivers comprehensive support, aligning closely with Zhang et al[20] recommendation to “integrate medical and psychological resources”. Second, strengthening training in psychological intervention skills for healthcare staff is necessary. Ma et al[22] noted that humanistic nursing care needs closely relate to psychological distress; in our model, nurses employed narrative nursing techniques (e.g., preparing patients through pre-treatment disease information) to effectively alleviate patient fear, suggesting these skills should be incorporated into routine training. Third, a dynamic psychological assessment mechanism should be established. Chukwuemeka et al[21] showed that psychological distress is dynamic; our model’s psychologist conducted regular weekly assessments (systematic screening Monday to Friday), ensuring timeliness and personalization of interventions. Additionally, health education grounded in self-efficacy theory (e.g., using successful case examples to boost patient confidence) can serve as an effective supplement to the three-in-one model, resonating with Zhang et al’s view[25] that “humane nursing must align with individualized patient needs”, further optimizing patient treatment experience and health outcomes.

This study has several limitations. The sample size is relatively small and drawn from a single institution, which may affect the generalizability of results. Additionally, the single-center design may introduce potential selection bias, as the enrolled patients may not fully represent the broader population of individuals with decompensated cirrhosis. Moreover, the intervention period was relatively short, precluding assessment of long-term effects. Although improvements in psychological distress, anxiety, and depression were observed one month post-discharge, the long-term sustainability of these effects remains uncertain, especially given the chronic and progressive nature of cirrhosis. Extended follow-up is warranted to evaluate durability over time. The lack of significant improvement in the environmental domain also indicates a need to explore more comprehensive intervention strategies. Future research could expand sample size, extend follow-up duration, and incorporate environmental intervention measures to further validate and refine this model.

Our findings suggest that an interdisciplinary team scheduling model is an effective intervention to improve psychological distress index, alleviate anxiety and depressive symptoms, and enhance quality of life in patients with de

| 1. | Mohammadi M, Hasjim BJ, Balbale SN, Polineni P, Huang AA, Paukner M, Banea T, Dentici O, Vitello DJ, Obayemi JE, Duarte-Rojo A, Nadig SN, VanWagner LB, Zhao L, Mehrotra S, Ladner DP. Disease trajectory and competing risks of patients with cirrhosis in the US. PLoS One. 2025;20:e0313152. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Philips CA. Commonly encountered symptoms and their management in patients with cirrhosis. Front Med (Lausanne). 2024;11:1442525. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Hansen L, Chang MF, Hiatt S, Dieckmann NF, Lyons KS, Lee CS. Symptom Frequency and Distress Underestimated in Decompensated Cirrhosis. Dig Dis Sci. 2022;67:4234-4242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Klankaew S, Temthup S, Nilmanat K, Fitch MI. The Effect of a Nurse-Led Family Involvement Program on Anxiety and Depression in Patients with Advanced-Stage Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Healthcare (Basel). 2023;11:460. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Hockey M, Rocks T, Ruusunen A, Jacka FN, Huang W, Liao B, Aune D, Wang Y, Nie J, O'Neil A. Psychological distress as a risk factor for all-cause, chronic disease- and suicide-specific mortality: a prospective analysis using data from the National Health Interview Survey. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2022;57:541-552. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Fricchione G. Mind body medicine: a modern bio-psycho-social model forty-five years after Engel. Biopsychosoc Med. 2023;17:12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Scriney A, Russell A, Loughney L, Gallagher P, Boran L. The impact of prehabilitation interventions on affective and functional outcomes for young to midlife adult cancer patients: A systematic review. Psychooncology. 2022;31:2050-2062. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Simone CB 2nd. Palliative therapies in hepatocellular carcinoma, palliative care in geriatric clinics, and the introduction of narrative medicine. Ann Palliat Med. 2024;13:1309-1311. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Hu G, Han B, Gains H, Jia Y. Effectiveness of narrative therapy for depressive symptoms in adults with somatic disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Clin Health Psychol. 2024;24:100520. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Xu L, Qian T. IDDF2025-ABS-0172 Association between the triglyceride glucose-body mass index and cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic syndrome risk in chronic liver disease: a nationwide prospective cohort study. Clin Hepatol. 2025;74:A253-A254. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 11. | Hjulstad K, Bondevik H, Hem MH, Nortvedt P. "Struck down by cancer with no old life to fall back on" a clinical study of illness experiences among Norwegian adolescent and young adult cancer survivors investigating the ethical implications of their illness narratives. Cancer Rep (Hoboken). 2023;6:e1765. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kitta A, Masel EK. Unveiling narrative medicine in palliative care. Ann Palliat Med. 2024;13:751-753. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Qi WJ, Hu J, Li LY. [Interpretation of NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Distress Management (Version 1.2018)]. Zhongguo Quanke Yixue. 2018;21:1765-1768. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 14. | Limonero JT, Maté-Méndez J, Gómez-Romero MJ, Mateo-Ortega D, González-Barboteo J, Bernaus M, López-Postigo M, Sirgo A, Viel S, Sánchez-Julve C, Bayés R, Gómez-Batiste X, Tomás-Sábado J. Family caregiver emotional distress in advanced cancer: the DME-C scale psychometric properties. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2023;13:e177-e184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Duan H, Gong M, Zhang Q, Huang X, Wan B. Research on sleep status, body mass index, anxiety and depression of college students during the post-pandemic era in Wuhan, China. J Affect Disord. 2022;301:189-192. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Skevington SM, Schick-Makaroff K, Rowland C, Molzahn A; and the WHOQOL Group. Women's environmental quality of life is key to their overall quality of life and health: Global evidence from the WHOQOL-100. PLoS One. 2024;19:e0310445. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Jiang RX, Pan SS, Liu YL, Guo SJ, Zhang HX, Sun HY, Li HL, Zhang HM, Li YN, Zhou CL, Xing CX, Yu RY, Wang YL, Wang L, Zhang FJ. [Current situation and influencing factors of humanistic care satisfaction of Chinese patients]. Zhonghua Yiyuan Guanli Zazhi. 2023;39:210-215. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 18. | Rodríguez-Labajos L, Kinloch J, Grant S, O'Brien G. The Role of the Built Environment as a Therapeutic Intervention in Mental Health Facilities: A Systematic Literature Review. HERD. 2024;17:281-308. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Yu XL, Zhu XP, Qiu CC, Wang JN. [Research progress in implementing narrative nursing among cancer patients]. Hulixue Zazhi. 2020;35:106-109. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 20. | Zhang M, Li Y, Fan Z, Shen D, Huang X, Yu Q, Liu M, Ren F, Wang X, Dai L, Wang P, Ye H, Shi J, Yang X, Zhang S, Zhang J. Assessing health-related quality of life and health utilities in patients with chronic hepatitis B-related diseases in China: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2021;11:e047475. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Chukwuemeka NA, Yinka Akintunde T, Uzoigwe FE, Okeke M, Tassang A, Oloji Isangha S. Indirect effects of health-related quality of life on suicidal ideation through psychological distress among cancer patients. J Health Psychol. 2024;29:1061-1073. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Ma F, Zhu Y, Liu Y. The relationship between psychological distress and the nursing humanistic care demands in postoperative cancer inpatients: a cross-sectional study. BMC Nurs. 2024;23:26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Wang GF, Xi N, Ai CQ. [Analysis of the impact of psychological nursing interventions on improving quality of life in patients with chronic renal failure]. Zhongguo Shangcan Yixue. 2016;4:165-166. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 24. | Zou H, Li M, Lei Q, Luo Z, Xue Y, Yao D, Lai Y, Ung COL, Hu H. Economic Burden and Quality of Life of Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Greater China: A Systematic Review. Front Public Health. 2022;10:801981. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Zhang Y, Wang H, Shan W, Cao J, Huang Y. Effects of humanized nursing interventions on psychological well-being and quality of life in rectal cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. Am J Transl Res. 2024;16:5728-5734. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Zhu S, Liao Q, Yuan H. Effect of Strength-Based Narrative Therapy on Depression Symptoms and Quality of Life in the Elderly. Iran J Public Health. 2025;54:124-132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/