Published online Jan 27, 2026. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v18.i1.114045

Revised: October 9, 2025

Accepted: November 25, 2025

Published online: January 27, 2026

Processing time: 139 Days and 15.9 Hours

Autoantibodies, including anti-nuclear antibodies (ANA), are typically present in autoimmune hepatitis (AIH), but may be detected in other liver conditions, inc

To identify predictive factors for the non-confirmation of AIH diagnosis in pa

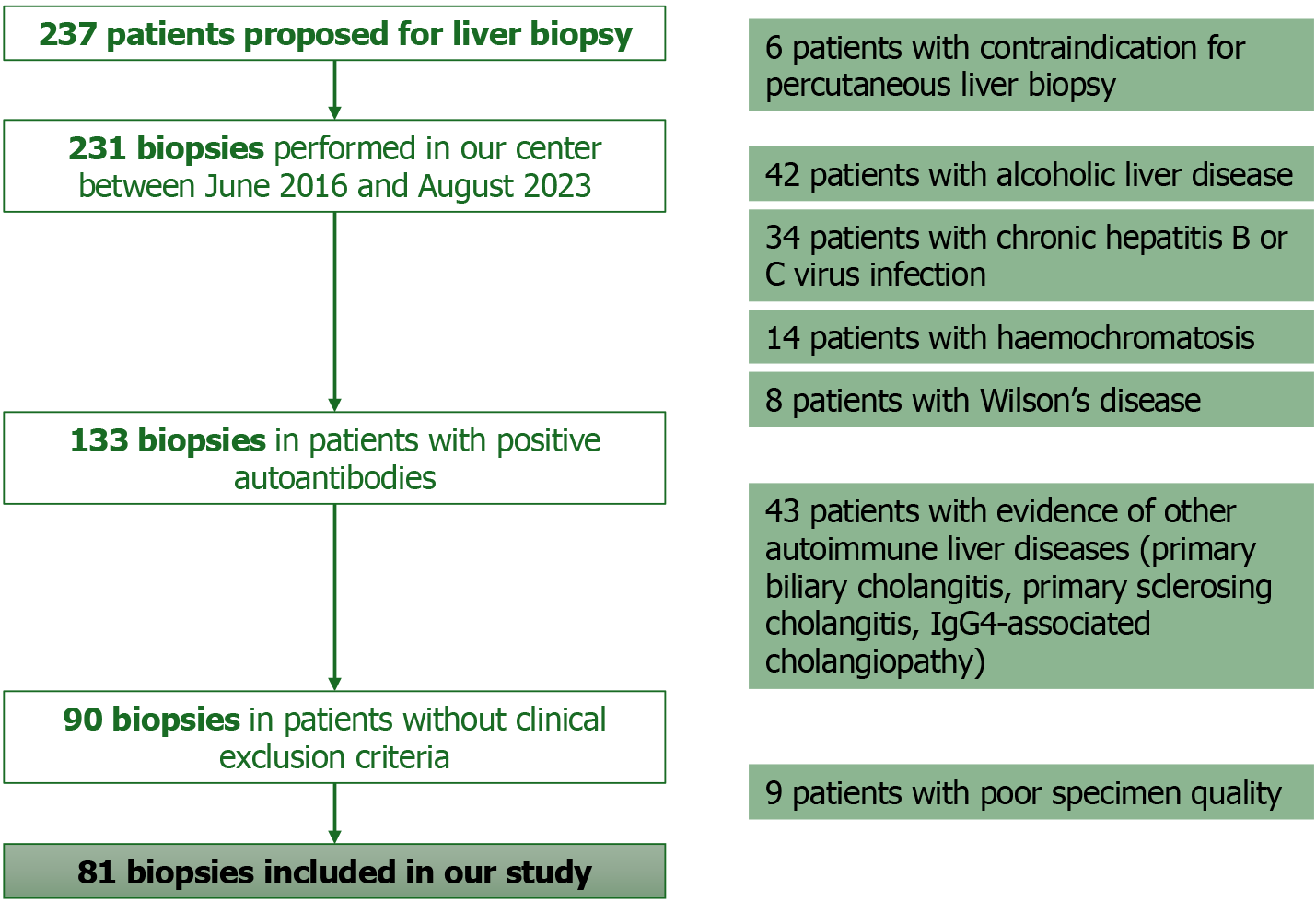

A retrospective cohort study was conducted in a university-affiliated hospital, including consecutive adult patients with liver dysfunction of unknown etiology and positive autoantibodies typically present in hepatic autoimmune disorders, who underwent liver biopsy, between June 2016 and August 2023. Patients with other known liver diseases or contraindications to liver biopsy were excluded, as well as those who underwent liver biopsy and had a poor specimen quality.

A total of 81 patients were included, of whom 53.1% were diagnosed with AIH and 46.9% with MASLD. ANA had a high sensitivity (83.7%) in diagnosing AIH but the lowest specificity (18.4%). In patients with ANA positivity, male, diabetic and obese individuals were more likely to have a non-confirmed AIH (P = 0.022, P = 0.039 and P = 0.046, respectively). Higher controlled attenuation parameter (CAP) values in patients with ANA positivity were associated with non-confirmed AIH diagnosis (288 ± 56 vs 244 ± 60, P = 0.012). In multivariate analysis, male gender and higher CAP values were independent predictive factors for non-confirmed AIH diagnosis (P = 0.011 and P = 0.034, respectively).

AIH was not confirmed in 47% of patients with liver dysfunction and positive autoantibodies. Multivariate analysis identified male gender and elevated CAP values as independent predictive factors for a non-confirmed diagnosis of AIH in patients with liver dysfunction and ANA positivity. Further prospective and multicenter validation is re

Core Tip: This retrospective study included 81 consecutive adult patients with liver dysfunction and positive autoantibodies undergoing liver biopsy. Autoimmune hepatitis was not confirmed in 47% of patients. In patients with anti-nuclear antibodies positivity, male gender and higher controlled attenuation parameter values emerged as independent predictive factors associated with non-confirmed diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis. These findings generate a valuable hypothesis that may inform future updates to clinical decision algorithms, particularly considering the rising prevalence of metabolic dys

- Citation: Ferreira AI, Costa Azevedo M, Macedo Silva V, Xavier S, Magalhães J, Cotter J. Not always autoimmune hepatitis: Hepatic steatosis is associated with autoantibodies positivity in patients with hepatocellular dysfunction. World J Hepatol 2026; 18(1): 114045

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v18/i1/114045.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v18.i1.114045

Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) is a chronic, progressive, immune-mediated liver disorder characterized by the presence of specific autoantibodies and elevated serum immunoglobulins, with a higher prevalence among women[1,2]. AIH can present in a variety of clinical presentations, ranging from acute hepatic dysfunction to established cirrhosis[1,2]. The diagnosis of AIH relies on a combination of histological findings, clinical and biochemical features and the detection of characteristic autoantibodies[1,2]. These include non-organ-specific autoantibodies, namely anti-nuclear antibodies (ANA) and smooth muscle antibodies (SMA), and the organ-specific autoantibodies, such as anti-liver kidney microsomal antibodies (anti-LKM), anti-liver cytosol type 1 (anti-LC-1) and antibodies against soluble liver antigen/liver pancreas autoantigen (anti-SLA/LP)[1].

Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) is defined as a steatotic liver disease in the presence of one or more cardiometabolic risk factors in the absence of harmful alcohol intake[3]. It is the leading cause of chronic liver disease globally, with a prevalence estimated to be 25%-30% of the general adult population[4]. MASLD also en

Autoantibodies, including ANA, are typical of AIH; however, they are not disease-specific and may also be detected in other conditions, including non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and the recently classified MASLD, even in the absence of an autoimmune disorder[5,6]. The prevalence of positive ANA in patients with NAFLD has been reported to be 13%-43%[7-9]. The presence of ANA in NAFLD leads to the activation of pro-inflammatory cytokines during immune responses, which in turn stimulates macrophages and hepatic stellate cells, contributing to liver damage progression[10]. It remains uncertain whether more advanced stages of steatosis are associated with a higher likelihood of positive au

Liver biopsy is indicated in patients with liver dysfunction of unknown etiology and is the cornerstone in the diagnosis of AIH[1,2,11]. Furthermore, liver biopsy can identify patients with liver dysfunction of other etiologies besides AIH[10].

The aim of this study was to identify predictive factors for the non-confirmation of AIH diagnosis in patients with liver dysfunction of unknown etiology and positive autoantibodies. Other secondary aims were to compare the sensitivities and specificities of distinct autoantibodies for AIH diagnosis and to create a valuable hypothesis that may inform future updates to clinical decision algorithms for the management of patients with positive autoantibodies in suspected AIH.

A retrospective cohort study was conducted in a university-affiliated hospital, including consecutive adult patients with liver dysfunction of unknown etiology and positive autoantibodies typically present in hepatic autoimmune disorders, who underwent liver biopsy, between June 2016 and August 2023. Patients with evidence of other autoimmune liver diseases (primary biliary cholangitis, primary sclerosing cholangitis, IgG4-associated cholangiopathy); chronic hepatitis B or C virus infection; Wilson’s disease; alcoholic liver disease; haemochromatosis; and/or contraindication for percu

AIH diagnosis relied on the presence of compatible histological findings supported by elevation of serum aminotransferases, positivity of characteristic autoantibodies and elevated IgG levels, as well as the exclusion of other liver diseases, according to the established criteria[1,2]. The histological features were categorized as typical, compatible or atypical of AIH[1,12]. The presence of interface hepatitis, lymphocytic or lymphoplasmacytic infiltrates in portal tracts and ex

MASLD diagnosis was based on evidence of hepatic steatosis identified by imaging or liver biopsy in adult patients, associated with any cardiometabolic criteria and in the absence of alcohol consumption superior to 20 g per day in women or superior to 30 g per day in men[3]. The cardiometabolic criteria included: Overweight or obesity [body mass index (BMI) ≥ 25 kg/m2 and/or a waist circumference ≥ 94 cm in men and ≥ 80 cm in women]; prediabetes (HbA1c 5.7%-6.4% or fasting plasma glucose 100-125 mg/dL), T2DM (HbA1c ≥ 6.5% or fasting plasma glucose ≥ 126 mg/dL) or treatment for T2DM; plasma triglycerides ≥ 150 mg/dL or lipid-lowering treatment; high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol ≤ 39 mg/dL in men or ≤ 50 mg/dL in women or lipid-lowering treatment; blood pressure ≥ 130/85 mmHg or treatment for hypertension[3].

Transient elastography (FibroScan® Compact 530, Echosens, Paris, France) was performed after a minimum fasting period of 2 hours[13]. Liver stiffness measurement (LSM) and controlled attenuation parameter (CAP) were recorded and reported in kilopascals and decibels per square meter (db/m2), respectively. The procedure was conducted with the patient in the dorsal decubitus position, with the right arm in maximal abduction. The probe, covered with ultrasound gel, was placed over the right hepatic lobe through the 9th to 11th intercostal spaces along the mid-axillary line. The LSM was considered valid if at least 10 valid measurements were obtained and the interquartile range (IQR) to median (M) ratio was below 30%[13]. The M probe was used initially for all patients, except for those with a skin-to-liver capsule distance greater than 25 mm which is an independent predictor of M probe failure[14]. In cases of M probe failure, measurements were repeated using the XL probe. Patients with conditions known to impair LSM reliability, such as extrahepatic cholestasis, serum aminotransferase levels equal or superior to five times the upper limit of normality, right heart failure or other causes of hepatic congestion, were excluded from assessment. The LSM and CAP values considered were the ones closest to the liver biopsy, with a maximum interval of three months between the TE and the liver biopsy.

Liver biopsy was performed via a percutaneous transthoracic approach, with the patient in the supine position. Biopsy location was determined using a prior abdominal ultrasound, with the patient holding their breath in deep expiration[11]. Local anaesthesia was administered at the selected intercostal space along the mid-axillary line, midway between the dome and the tip of the liver, and a small skin incision was made[11]. A 16G Menghini needle was then inserted through the intercostal space, just above the lower rib, and advanced toward the xiphisternum, parallel to the bed surface[11]. Following the procedure, patients were positioned on their right side for 2 hours, and vital signs, including pulse and blood pressure, were monitored regularly to detect any adverse events[11]. All included patients underwent liver biopsy with a high-quality specimen, measuring at least 15 mm and showing a minimum of 11 portal tracts on histological ass

Demographic, clinical, biochemical, imaging and histological data were collected and registered anonymously in a database. Patients’ demographics included gender and age. The patients’ cardiometabolic comorbidities were reported, namely, arterial hypertension, T2DM, dyslipidemia, obesity and previous history of cardiovascular events. Obesity was regarded as a BMI equal or superior to 30.0 kg/m2. Additionally, the presence of other autoimmune disorders was reported. Biochemical data included total bilirubin, aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) and alkaline phosphatase (ALP), as well as the IgG levels and the autoantibodies ANA, SMA, anti-LKM, anti-LC-1 and anti-SLA/LP. The LSM and the CAP values were evaluated by transient elasto

Categorical variables were described as frequencies and percentages, and continuous variables as mean and SD if normally distributed, or as median and IQR if not normally distributed. Comparison of categorical variables was per

A total of 81 patients were included, most were female (70.4%), with a mean age of 55 ± 15 years. The most commonly detected autoantibody was ANA in 67 patients (82.7%), followed by anti-SLA/LP in 13 (16.0%) and SMA in 10 patients (12.3%). A total of 19 patients (23.5%) tested positive for ANA concurrently with at least one other autoantibody, such as SMA, anti-LKM, anti-LC-1 or anti-SLA/LP.

Liver biopsy was performed in all patients, with 55 patients (67.9%) having lymphocyte infiltrate, 39 (48.1%) hepatic steatosis and 5 patients (6.2%) interface hepatitis. AIH was diagnosed in 43 patients (53.1%), and the remaining 38 pa

One patient (1.2%) experienced a self-limited hemorrhage following liver biopsy, which led to hospitalization due to hemoperitoneum. The patients’ baseline demographic and clinical characteristics, presence of autoantibodies and his

| Variable | Patients’ characteristics |

| Gender | |

| Female | 57 (70.4) |

| Male | 24 (29.6) |

| Age (years) | 55 ± 15 |

| Cardiometabolic factors | |

| Arterial hypertension | 31 (38.3) |

| T2DM | 18 (22.2) |

| Dyslipidaemia | 32 (39.5) |

| Obesity | 26 (32.1) |

| Previous cardiovascular event | 4 (4.9) |

| Presence of other autoimmune disorders | 6 (7.4) |

| Positivity of autoantibodies | |

| ANA | 67 (82.7) |

| SMA | 10 (12.3) |

| Anti-LKM | 5 (6.3) |

| Anti-LC-1 | 6 (9.0) |

| Anti-SLA/LP | 13 (16.0) |

| Elevated IgG levels | 21 (29.6) |

| Histological findings | |

| Hepatic steatosis | 39 (48.1) |

| Lymphocyte infiltrate | 55 (67.9) |

| Interface hepatitis | 5 (6.2) |

| Emperipolesis | 0 (0.0) |

| Hepatocyte rosettes | 0 (0.0) |

| Histological criteria for AIH | |

| Typical | 5 (6.2) |

| Compatible | 38 (46.9) |

| Atypical | 38 (46.9) |

ANA had a high sensitivity (83.7%) in diagnosing AIH but the lowest specificity (18.4%) of all autoantibodies. The other evaluated autoantibodies had high specificity and low sensitivity in diagnosing AIH. The sensitivity and specificity of each autoantibody is presented in Table 2.

| Autoantibody | Sensitivity | Specificity |

| ANA | 83.7% | 18.4% |

| SMA | 18.6% | 94.7% |

| Anti-LKM | 7.0% | 94.7% |

| Anti-LC-1 | 11.4% | 93.8% |

| Anti-SLA/LP | 14.0% | 81.6% |

The presence of elevated levels of IgG had a sensitivity of 38.5% and a specificity of 81.3% in diagnosing AIH.

A total of 67 patients (82.7%) had ANA positivity. In these patients, AIH diagnosis was confirmed in 36 patients (53.7%) and the remaining 31 patients (46.3%) were diagnosed with MASLD. The ANA titers showed no correlation with the diagnosis of AIH (P = 0.274), as well as positivity of two or more autoantibodies (P = 0.126).

Male patients were 4 times more likely to have a non-confirmed diagnosis of AIH (OR = 3.61, 95%CI: 1.17-11.24, P = 0.022). Diabetics and obese patients were 3 times more likely to have a non-confirmed AIH diagnosis (OR = 3.42, 95%CI: 1.03-11.24, P = 0.039 and OR = 2.88, 95%CI: 1.00-8.26, P = 0.046, respectively). A higher CAP value was associated with non-confirmed diagnosis of AIH (288 ± 56 vs 244 ± 60, P = 0.012).

Patients with elevated IgG were 3 times more likely to have a confirmed diagnosis of AIH (OR = 3.27, 95%CI: 0.984-10.841, P = 0.048). Patients with confirmed AIH diagnosis had a higher median value of ALT [85 (154) vs 50 (54), P = 0.021].

Factors associated with AIH diagnosis in patients with ANA positivity are detailed in Table 3. In multivariate analysis, presented in Table 4, male gender and higher CAP values were independent predictive factors associated with non-confirmed diagnosis of AIH (P = 0.011 and P = 0.034, respectively).

| Variable | AIH diagnosis confirmed (n = 36) | AIH diagnosis not confirmed (n = 31) | P value |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 30 (83.3) | 18 (58.1) | 0.022 |

| Male | 6 (16.7) | 13 (41.9) | |

| Age (years) | 55 ± 16 | 58 ± 13 | 0.333 |

| Arterial hypertension | 13 (36.1) | 14 (45.2) | 0.451 |

| T2DM | 5 (13.9) | 11 (35.5) | 0.039 |

| Dyslipidaemia | 13 (36.1) | 16 (51.6) | 0.202 |

| Obesity | 8 (22.2) | 14 (45.2) | 0.046 |

| Previous cardiovascular event | 2 (5.6) | 2 (6.5) | 1.000 |

| Other autoimmune disorders | 4 (11.1) | 1 (3.2) | 0.363 |

| Positivity of autoantibodies | |||

| SMA | 7 (19.4) | 1 (3.2) | 0.060 |

| Anti-LKM | 2 (5.6) | 1 (3.2) | 1.000 |

| Anti-LC-1 | 4 (11.1) | 1 (3.2) | 0.353 |

| Elevated IgG levels | 14 (38.9) | 5 (16.1) | 0.048 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL), median (IQR) | 0.67 (0.52) | 0.68 (0.60) | 0.905 |

| AST (UI/L), median (IQR) | 66 (105) | 36 (40) | 0.092 |

| ALT (UI/L), median (IQR) | 85 (154) | 50 (54) | 0.021 |

| GGT (UI/L), median (IQR) | 99 (150) | 52 (94) | 0.065 |

| ALP (UI/L), median (IQR) | 106 (76) | 91 (48) | 0.258 |

| CAP (dB/m2) | 244 ± 60 | 288 ± 56 | 0.012 |

| LSM (kPa), median (IQR) | 5.4 (3.1) | 6.7 (14.9) | 0.205 |

| Variable | Exp (B) | 95%CI | P value |

| Male gender | 6.883 | 1.549-30.578 | 0.011 |

| T2DM | 3.944 | 0.791-19.661 | 0.094 |

| CAP (dB/m2) | 1.014 | 1.001-1.027 | 0.034 |

Patients with significant liver steatosis, such as those with NAFLD, and liver dysfunction often present with positive serum autoantibodies, a feature also commonly seen in AIH[10]. Liver biopsy is frequently required to establish an acc

The most commonly detected autoantibody was ANA in 83% of patients. In fact, ANA had a high sensitivity in dia

This retrospective study, which included adult patients with liver dysfunction and positive autoantibodies who underwent liver biopsy, aimed to identify predictive factors for the non-confirmation of AIH diagnosis in patients with liver dysfunction of unknown etiology and positive autoantibodies. In our cohort, AIH was diagnosed in only 53% of the patients, with the remaining 47% being diagnosed with MASLD. A recent meta-analysis revealed that the overall prevalence of ANA positivity in patients with NAFLD was 23%[10]. Other studies have reported the presence of positive autoantibodies in up to one third of patients with NAFLD without concurrent AIH, both in children and in adults[17,18,20-22]. Therefore, the approach to these patients should be reconsidered. Liver biopsy could be postponed in patients with non-specific autoantibody positivity and higher risk of non-confirmation of AIH diagnosis, since it is an invasive di

Our study also evaluated the presence of elevated levels of IgG, which had a low sensitivity but a high specificity of more than 80% in diagnosing AIH. Additionally, in patients with ANA positivity, those with elevated IgG were more likely to have a confirmed diagnosis of AIH. This parameter is also important in the diagnosis of AIH and has been previously demonstrated to be typical of AIH, although not necessarily present[1,2,23]. In a study which evaluated the prevalence of non-specific autoantibody positivity in overweight and obese children with NAFLD, a normal level of IgG was the most significant negative predictor of AIH[24].

Since ANA was the most commonly detected autoantibody and revealed the highest sensitivity with the lowest specificity, we particularly evaluated patients with ANA positivity to identify possible predictive factors for the non-confirmation of AIH diagnosis in these patients. Notably, we found that male patients were more likely to exhibit positive ANA without a subsequent diagnosis of AIH, suggesting that ANA positivity in men may not be indicative of underlying autoimmune liver disease. In fact, MASLD has been established as a pro-inflammatory condition[25], which can suggest that, in our male population, this inflammatory environment was likely the underlying mechanism leading to the deve

In our cohort, patients with T2DM and obesity, which are typical features of cardiometabolic syndrome, were more likely to have a non-confirmed diagnosis of AIH. More importantly, our analysis also revealed that patients with liver dy

In multivariate analysis, male gender and higher CAP values were independent predictive factors associated with non-confirmed diagnosis of AIH. We created a hypothesis that could be used in prospective studies and may inform future updates to clinical decision algorithms for the management of patients with positive autoantibodies in suspected AIH, represented in the Supplementary material. Since liver biopsy is invasive and carries potential risks, we suggest an expectant, non-invasive approach in male patients with advanced steatosis (S3), particularly in the absence of progressive or severe liver dysfunction. In such cases, prioritizing the management of metabolic and cardiovascular risk factors alongside close monitoring of liver tests could help avoid unnecessary biopsies while maintaining surveillance. However, it is important to note our findings need external validation, particularly in large multi-center studies in order to support the reliability and applicability of the algorithm. Our study has some limitations, including its retrospective design and relatively small sample size. Nonetheless, it is the first study to identify predictive factors for the non-confirmation of AIH diagnosis in patients with liver dysfunction of unknown etiology and positive autoantibodies.

AIH was not confirmed in nearly half of the patients with liver dysfunction and positive autoantibodies. Among the autoantibodies typically associated with AIH, ANA showed the lowest specificity despite its high sensitivity. In this context, male gender and elevated CAP values emerged as independent predictors of a non-confirmed AIH diagnosis. These findings offer important insights for updating clinical decision algorithms, especially given the rising prevalence of MASLD. In male patients with advanced steatosis (CAP values above 280 dB/m2), we advocate for a more conservative approach, focusing on metabolic risk factor control and weight reduction, before proceeding with invasive diagnostics such as liver biopsy.

| 1. | European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines on the management of autoimmune hepatitis. J Hepatol. 2025;83:453-501. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 44.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Mack CL, Adams D, Assis DN, Kerkar N, Manns MP, Mayo MJ, Vierling JM, Alsawas M, Murad MH, Czaja AJ. Diagnosis and Management of Autoimmune Hepatitis in Adults and Children: 2019 Practice Guidance and Guidelines From the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology. 2020;72:671-722. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 282] [Cited by in RCA: 650] [Article Influence: 108.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL); European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD); European Association for the Study of Obesity (EASO). EASL-EASD-EASO Clinical Practice Guidelines on the management of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD). J Hepatol. 2024;81:492-542. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 993] [Article Influence: 496.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Rinella ME, Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Siddiqui MS, Abdelmalek MF, Caldwell S, Barb D, Kleiner DE, Loomba R. AASLD Practice Guidance on the clinical assessment and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2023;77:1797-1835. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1465] [Cited by in RCA: 1606] [Article Influence: 535.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Sebode M, Weiler-Normann C, Liwinski T, Schramm C. Autoantibodies in Autoimmune Liver Disease-Clinical and Diagnostic Relevance. Front Immunol. 2018;9:609. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 12.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (6)] |

| 6. | Loria P, Lonardo A, Leonardi F, Fontana C, Carulli L, Verrone AM, Borsatti A, Bertolotti M, Cassani F, Bagni A, Muratori P, Ganazzi D, Bianchi FB, Carulli N. Non-organ-specific autoantibodies in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: prevalence and correlates. Dig Dis Sci. 2003;48:2173-2181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Cotler SJ, Kanji K, Keshavarzian A, Jensen DM, Jakate S. Prevalence and significance of autoantibodies in patients with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;38:801-804. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 8. | Younes R, Govaere O, Petta S, Miele L, Tiniakos D, Burt A, David E, Vecchio FM, Maggioni M, Cabibi D, Fracanzani AL, Rosso C, Blanco MJG, Armandi A, Caviglia GP, Zaki MYW, Liguori A, Francione P, Pennisi G, Grieco A, Valenti L, Anstee QM, Bugianesi E. Presence of Serum Antinuclear Antibodies Does Not Impact Long-Term Outcomes in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;115:1289-1292. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Zhou YJ, Zheng KI, Ma HL, Li G, Pan XY, Zhu PW, Targher G, Byrne CD, Wang XD, Chen YP, Li XB, Zheng MH. Association between positivity of serum autoantibodies and liver disease severity in patients with biopsy-proven NAFLD. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2021;31:552-560. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Luo L, Ma Q, Lin L, Wang H, Ye J, Zhong B. Prevalence and Significance of Antinuclear Antibodies in Biopsy-Proven Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Dis Markers. 2022;2022:8446170. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Neuberger J, Patel J, Caldwell H, Davies S, Hebditch V, Hollywood C, Hubscher S, Karkhanis S, Lester W, Roslund N, West R, Wyatt JI, Heydtmann M. Guidelines on the use of liver biopsy in clinical practice from the British Society of Gastroenterology, the Royal College of Radiologists and the Royal College of Pathology. Gut. 2020;69:1382-1403. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 257] [Cited by in RCA: 282] [Article Influence: 47.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Hennes EM, Zeniya M, Czaja AJ, Parés A, Dalekos GN, Krawitt EL, Bittencourt PL, Porta G, Boberg KM, Hofer H, Bianchi FB, Shibata M, Schramm C, Eisenmann de Torres B, Galle PR, McFarlane I, Dienes HP, Lohse AW; International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group. Simplified criteria for the diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatology. 2008;48:169-176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1205] [Cited by in RCA: 1311] [Article Influence: 72.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 13. | Mikolasevic I, Orlic L, Franjic N, Hauser G, Stimac D, Milic S. Transient elastography (FibroScan(®)) with controlled attenuation parameter in the assessment of liver steatosis and fibrosis in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease - Where do we stand? World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:7236-7251. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 205] [Cited by in RCA: 214] [Article Influence: 21.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Arieira C, Monteiro S, Xavier S, Dias de Castro F, Magalhães J, Marinho C, Pinto R, Costa W, Pinto Correia J, Cotter J. Transient elastography: should XL probe be used in all overweight patients? Scand J Gastroenterol. 2019;54:1022-1026. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Zhang WC, Zhao FR, Chen J, Chen WX. Meta-analysis: diagnostic accuracy of antinuclear antibodies, smooth muscle antibodies and antibodies to a soluble liver antigen/liver pancreas in autoimmune hepatitis. PLoS One. 2014;9:e92267. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Muñoz-Sánchez G, Pérez-Isidro A, Ortiz de Landazuri I, López-Gómez A, Bravo-Gallego LY, Garcia-Ormaechea M, Julià MR, Viñas O, Ruiz-Ortiz E, On Behalf Of The Geai-Sei Workshop Participants. Working Algorithms and Detection Methods of Autoantibodies in Autoimmune Liver Disease: A Nationwide Study. Diagnostics (Basel). 2022;12:697. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | De Roza MA, Lamba M, Goh GB, Lum JH, Cheah MC, Ngu JHJ. Immunoglobulin G in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis predicts clinical outcome: A prospective multi-centre cohort study. World J Gastroenterol. 2021;27:7563-7571. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 18. | McPherson S, Henderson E, Burt AD, Day CP, Anstee QM. Serum immunoglobulin levels predict fibrosis in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol. 2014;60:1055-1062. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Soria A, Díaz A, Iruzubieta P, Martín-Mateos R, Salcedo-Allende MT, Jiménez-Masip A, Fuster-Anglada C, Arias-Loste MT, Perna C, El Maimouni C, Pericas JM, Ferrer-Gómez A, González CJ, Muñoz-Martínez S, Padilla M, Crespo J, Calixto Z, Sabiote C, Albillos A, Cervera M, Olivas I, Arvaniti P, Hernández-Évole H, Jiménez-Esquivel N, Gratacós-Ginès J, Juanola A, Pose E, Coll M, Nadal R, Pérez-Guasch M, Fabrellas N, Ginès P, Londoño MC, Graupera I. Autoantibodies are associated with worse outcomes in MASLD. JHEP Rep. 2025;7:101470. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Schwimmer JB, Newton KP, Awai HI, Choi LJ, Garcia MA, Ellis LL, Vanderwall K, Fontanesi J. Paediatric gastroenterology evaluation of overweight and obese children referred from primary care for suspected non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;38:1267-1277. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 173] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Yatsuji S, Hashimoto E, Kaneda H, Taniai M, Tokushige K, Shiratori K. Diagnosing autoimmune hepatitis in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: is the International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group scoring system useful? J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:1130-1138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Yodoshi T, Orkin S, Arce-Clachar AC, Bramlage K, Xanthakos SA, Mouzaki M, Valentino PL. Significance of autoantibody seropositivity in children with obesity and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Pediatr Obes. 2021;16:e12696. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Ducazu O, Degroote H, Geerts A, Hoorens A, Schouten J, Van Vlierberghe H, Verhelst X. Diagnostic and prognostic scoring systems for autoimmune hepatitis: a review. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 2021;84:487-495. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Khayat A, Vitola B. Prevalence and Clinical Significance of Autoantibodies in Children with Overweight and Obesity with Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. J Pediatr. 2021;239:155-160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Chiang CH, Huang CC, Chan WL, Chen JW, Leu HB. The severity of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease correlates with high sensitivity C-reactive protein value and is independently associated with increased cardiovascular risk in healthy population. Clin Biochem. 2010;43:1399-1404. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Wilkinson NM, Chen HC, Lechner MG, Su MA. Sex Differences in Immunity. Annu Rev Immunol. 2022;40:75-94. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 156] [Article Influence: 39.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Oliver JE, Silman AJ. Why are women predisposed to autoimmune rheumatic diseases? Arthritis Res Ther. 2009;11:252. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 136] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Shrestha R, Kc S, Thapa P, Pokharel A, Karki N, Jaishi B. Estimation of Liver Fat by FibroScan in Patients With Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Cureus. 2021;13:e16414. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Pu K, Wang Y, Bai S, Wei H, Zhou Y, Fan J, Qiao L. Diagnostic accuracy of controlled attenuation parameter (CAP) as a non-invasive test for steatosis in suspected non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Gastroenterol. 2019;19:51. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in RCA: 154] [Article Influence: 22.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Castera L, Friedrich-Rust M, Loomba R. Noninvasive Assessment of Liver Disease in Patients With Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Gastroenterology. 2019;156:1264-1281.e4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 619] [Cited by in RCA: 1124] [Article Influence: 160.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 31. | Vuppalanchi R, Gould RJ, Wilson LA, Unalp-Arida A, Cummings OW, Chalasani N, Kowdley KV; Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis Clinical Research Network (NASH CRN). Clinical significance of serum autoantibodies in patients with NAFLD: results from the nonalcoholic steatohepatitis clinical research network. Hepatol Int. 2012;6:379-385. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Jain K, Rastogi A, Thomas SS, Bihari C. Autoantibody Positivity Has No Impact on Histological Parameters in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Diseases. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2023;13:730-735. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Cebi M, Yilmaz Y. Immune system dysregulation in the pathogenesis of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: unveiling the critical role of T and B lymphocytes. Front Immunol. 2024;15:1445634. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/