Published online Dec 27, 2025. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v17.i12.111418

Revised: September 1, 2025

Accepted: November 5, 2025

Published online: December 27, 2025

Processing time: 180 Days and 14.9 Hours

Advanced chronic liver disease is a progressive condition associated with high mor

To evaluate the prognostic value of hepatic enhancement (HE) and signal int

In this retrospective cohort study, 100 patients with advanced chronic liver disease underwent gadoxetate-enhanced MRI. HE and signal intensity were measured quantitatively in liver segments III, VI, VIII, and the caudate lobe, and global values were calculated by averaging segmental measurements. Correlations were assessed with FLIS, Child-Pugh, MELD 3.0, ALBI, FIB-4, liver stiffness (FibroScan), and hepatic venous pressure gradient. Cox regression and receiver operating characteristic analysis were used to evaluate associations with hepatic decompensation, mortality, and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) occurrence during follow-up.

Global HE showed a significant correlation with FLIS (r = 0.797), Child-Pugh (r = -0.589), MELD 3.0 (r = -0.658), ALBI (r = -0.599), FIB-4 (r = -0.308), liver stiffness (r = -0.470), and hepatic venous pressure gradient (r = -0.340). Lower HE was significantly associated with a higher risk of decompensation and mortality in univariate Cox regression. After adjustment for MELD 3.0, etiology, and prior HCC, segment VI HE remained independently predictive of mortality. At 12 months, HE improved risk stratification for mortality and reduced unnecessary interventions by 11 per 100 patients at a 10% threshold in the decision curve analysis. HE had an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve of 0.74 for predicting decompensation and 0.74 for predicting mortality. HE was higher in patients who developed or experienced recurrence of HCC during follow-up, but this was not statis

Lower HE in segment VI improved prognostic classification of high-risk patients. These patients align with Baveno VII criteria for intensified management, supporting the potential role of HE in risk-adapted surveillance.

Core Tip: This study investigated whether quantitative gadoxetate-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging can enhance prognostic assessment in patients with advanced chronic liver disease. Among 100 patients, hepatic enhancement (HE) and signal intensity were measured segmentally and globally. Global HE correlated strongly with Functional Liver Imaging Score, clinicobiological scores, liver stiffness, and portal pressure. Notably, lower HE independently predicted hepatic deco

- Citation: Stanciu BI, Iojiban M, Morariu-Barb A, Caraiani C, Procopet B, Stefanescu H, Lupsor-Platon M. Hepatic enhancement and signal intensity analysis on magnetic resonance imaging as prognostic biomarkers in advanced chronic liver disease. World J Hepatol 2025; 17(12): 111418

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v17/i12/111418.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v17.i12.111418

Advanced chronic liver disease (ACLD) encompasses a range of progressive hepatic conditions with escalating global prevalence, accounting for approximately two million deaths annually[1]. The growing prevalence of metabolic dys

Although vaccination efforts and antiviral therapies have started to lower the rates of viral hepatitis, chronic hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus infections still play a significant role in the worldwide burden of liver disease. At the same time, alcohol-related liver disease is rising due to increasing alcohol consumption worldwide[1]. Cirrhosis, the final stage of ACLD, entails persistent damage to liver structure and function and is associated with a high risk of complications such as portal hypertension, clinical decompensation, and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

In clinical practice, evaluating liver function is crucial for making informed treatment decisions, assessing prognosis, and planning surgical procedures. Current methods include laboratory tests (e.g., transaminases, albumin, bilirubin, and international normalized ratio [INR])[6], clinical scoring systems (e.g., Child-Pugh and MELD), and dynamic assessments including indocyanine green clearance[6,7]. Conventional prognostic models, such as the Child-Pugh and MELD scores, continue to be the primary tools for predicting outcomes in ACLD. The MELD 3.0 score, a recent update to the original model, was designed to enhance prognostic accuracy and mitigate sex-related disparities. Several validation studies have confirmed its superior prognostic performance compared to the traditional MELD score[8]. Although MELD 3.0 has already been adopted in selected clinical settings, its integration into routine transplant allocation policies is still ongoing[9]. Despite their established role in assessing disease severity, both Child-Pugh and MELD 3.0 scores are limited by poor sensitivity in detecting early functional decline, especially in compensated disease. The Child-Pugh score also includes subjective factors, such as the presence of ascites and encephalopathy, which reduce consistency and detail by grouping patients into only three broad categories. Overall, these tools provide a static and often incomplete view of liver health, with limited ability to detect dynamic changes or responses to treatment, underscoring the need for modern, objective, and adaptable prognostic methods[10,11].

Conventional imaging techniques, including ultrasound, computed tomography, MRI, and elastography, have traditionally been used to evaluate liver morphology, characterize lesions, and determine the stage of fibrosis. However, in the context of ACLD, these methods provide limited insight into hepatic functional reserve and lack standardized, reproducible measurement protocols. Recent advances in hepatobiliary contrast-enhanced MRI, particularly with gadoxetate disodium (Gd-EOB-DTPA; Primovist), have enabled non-invasive evaluation of liver function[12,13]. Healthy hepatocytes take up this liver-specific contrast agent via organic anion-transporting polypeptides (OATPs), whose expression diminishes in cases of hepatocellular damage and fibrosis-related structural alterations. As a result, hepatic uptake of gadoxetate during the hepatobiliary phase may serve as a marker of liver function and a predictor of patient prognosis.

Emerging evidence suggests that specific MRI-derived parameters, such as the liver-to-spleen signal intensity (SI) ratio and liver-to-spleen volume ratio, can predict decompensation and mortality in patients with ACLD, thereby serving as prognostic markers[14]. Additionally, some imaging markers demonstrate a strong correlation with liver stiffness measured by elastography and serologic fibrosis markers, indicating their broader usefulness for non-invasive fibrosis staging[15]. The quantitative nature of these metrics enhances their value for clinical research and future risk stratification in ACLD. To facilitate the non-invasive assessment of liver function, semi-quantitative imaging scores such as the Functional Liver Imaging Score (FLIS) have been developed. FLIS is based on the visual evaluation of gadoxetate-enhanced MR images during the hepatobiliary phase and includes three components: Hepatic parenchymal enhan

Despite these promising developments, the use of functional MRI biomarkers in clinical practice remains limited. Many proposed parameters lack standardization and have not yet been integrated into current clinical guidelines. Additionally, most existing research mainly focuses on correlations with clinical scores without thoroughly evaluating the ability of imaging biomarkers to independently predict the risk of decompensation or mortality, particularly in the compensated stages of liver disease. Accordingly, the aims of this study are as follows: (1) To assess the efficacy of gadoxetate-en

This study included 100 adult patients (aged 18 years and older) with a confirmed diagnosis of ACLD following current clinical guidelines[17,18]. All participants underwent gadoxetate disodium-enhanced liver MRI (Primovist) between January 2020 and July 2021 at the Regional Institute of Gastroenterology and Hepatology “Octavian Fodor” in Cluj-Napoca. Imaging features indicative of ACLD, identified through ultrasound, elastography, computed tomography, or MRI before enrollment, included nodular liver morphology, caudate lobe hypertrophy, splenomegaly, signs of portal hypertension (e.g., portosystemic collaterals, ascites, and portal vein dilation), parenchymal heterogeneity, and liver stiffness values exceeding 10 kPa.

Patients were excluded from the study if they exhibited renal dysfunction (glomerular filtration rate < 30 mL/minute/1.73 m2), advanced heart failure (New York Heart Association class III-IV), or severe imaging artifacts during the hepatobiliary phase that could impede MRI interpretation. The following laboratory parameters were collected for all participants: Hemoglobin, platelet count, aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, gamma-glutamyl transferase, total and direct bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase, sodium, potassium, urea, creatinine, albumin, INR, C-reactive protein, and alpha-fetoprotein. Using these values, the Child-Pugh score[19], MELD 3.0 score[8], ALBI score[20], and FIB-4 index[21] were calculated. All patients also underwent abdominal ultrasound to assess liver structure, detect signs of portal hypertension (e.g., splenomegaly, portal vein dilation, and portosystemic collaterals), and monitor or identify ascites.

Seventy-eight patients underwent upper gastrointestinal endoscopy following current recommendations[11] for screening esophageal varices, portal hypertensive gastropathy, and gastric varices. Endoscopic findings were utilized to assess bleeding risk and to guide decisions regarding primary prophylaxis. Each patient underwent liver elastography using vibration-controlled transient elastography (VCTE) via the FibroScan system (Echosens, Paris, France). The examinations were performed while the subjects were fasting, in accordance with established guidelines[22]. A subset of 26 patients underwent measurement of HVPG via transjugular catheterization. Normal HVPG values were delineated as 1-5 mmHg; values exceeding 5 mmHg indicated subclinical portal hypertension, whereas measurements of 10 mmHg or higher signified clinically significant portal hypertension[23]. All procedures were conducted under stable conditions, with patients positioned supine and at rest, in accordance with international protocols[24]. Each patient underwent a comprehensive clinical, laboratory, and ultrasound evaluation at baseline, and at subsequent 6-month intervals, to do

Hepatic decompensation was defined as the documented occurrence of any of the following: Ascites, upper gas

All patients underwent imaging using a 1.5 T MRI scanner (Magnetom Aera; Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) with a six-channel body coil. The native MRI protocol consisted of axial scans of the liver using a fat-suppressed T1-weighted gradient echo sequence (T1 volume-interpolated breath-hold examination fat suppression). Following the unenhanced scan, a hepatobiliary-specific contrast agent, gadoxetate disodium (Primovist; Bayer AG, Leverkusen, Germany), was administered intravenously via an automated injector at a dosage of 0.025 mmol/kg of body weight. The injection rate was set at 1 mL/second, followed by a saline flush of 25 mL. Multiphase contrast-enhanced imaging was conducted in the axial plane utilizing T1 volume-interpolated breath-hold examination fat suppression sequences at designated post-injection time points: Arterial phase (20 seconds), portal venous phase (70 seconds), equilibrium phase (3 minutes), transitional phase (6 minutes), and hepatobiliary phase (20 minutes). The acquisition parameters remained consistent across all phases: Slice thickness of 3 mm, repetition time of 4.49 milliseconds, echo time of 2.19 milliseconds, number of excitations = 1, flip angle = 10°, matrix = 320 × 195, and pixel bandwidth = 345 Hertz.

All MRI images were examined utilizing a picture archiving and communication system supplied by PixelData (Cluj-Napoca, Romania), which facilitates digital imaging and communication in medicine-format image storage, access, and analysis. An abdominal radiologist, blinded to the clinical and laboratory information, conducted the image review. The FLIS was assessed on hepatobiliary-phase images as a semi-quantitative method to evaluate hepatic function. The FLIS was established through a visual assessment of three components: Hepatic parenchymal enhancement in comparison to the right kidney, biliary excretion of the contrast agent, and portal vein SI relative to the liver parenchyma[12] (Table 1). The total score was calculated by adding the scores from its three components, resulting in a range from 0 to 6. A FLIS score of 5 to 6 indicates preserved liver function, whereas a score of 3 to 4 reflects moderate dysfunction. Conversely, a score of 0 to 2 suggests significant liver impairment, often associated with portal hypertension and a poor prognosis[16,25].

| Parameter | Score 0 | Score 1 | Score 2 |

| Hepatic enhancement (liver signal intensity vs right kidney) | Hypointense | Isointense | Hyperintense |

| Biliary excretion (presence of contrast in biliary structures) | No excretion | Intrahepatic bile ducts | Common bile duct or duodenum |

| Portal vein signal (portal vein intensity vs liver parenchyma) | Hyperintense | Isointense | Hypointense |

SI measurements were conducted utilizing the built-in tools of the viewer three-dimensional pro application within the PixelData picture archiving and communication system. Circular regions of interest (ROIs), each with a standardized area of 1 cm2, were manually positioned within the hepatic parenchyma. The software automatically computed SI values as the mean of all pixel intensities within each ROI. To ensure precision, ROIs were exclusively placed in homogeneous regions of the liver parenchyma, deliberately avoiding vascular structures, bile ducts, and focal lesions such as HCC, regenerative nodules, or vascular malformations.

The liver was divided into eight anatomical segments following the Couinaud classification. Segments III, VI, VIII, and I (caudate lobe) were chosen for analysis to cover both hepatic lobes, anterior and posterior territories, and the caudate lobe. This selection aimed to maximize the representation of regional functional differences while allowing consistent ROI placement in parenchyma that is relatively free of large vessels, bile ducts, or artifacts. Although direct evidence for segment-specific perfusion differences is limited, recent studies suggest that these regions show greater perfusion heterogeneity in portal hypertension, justifying the inclusion of multiple vascular territories[26].

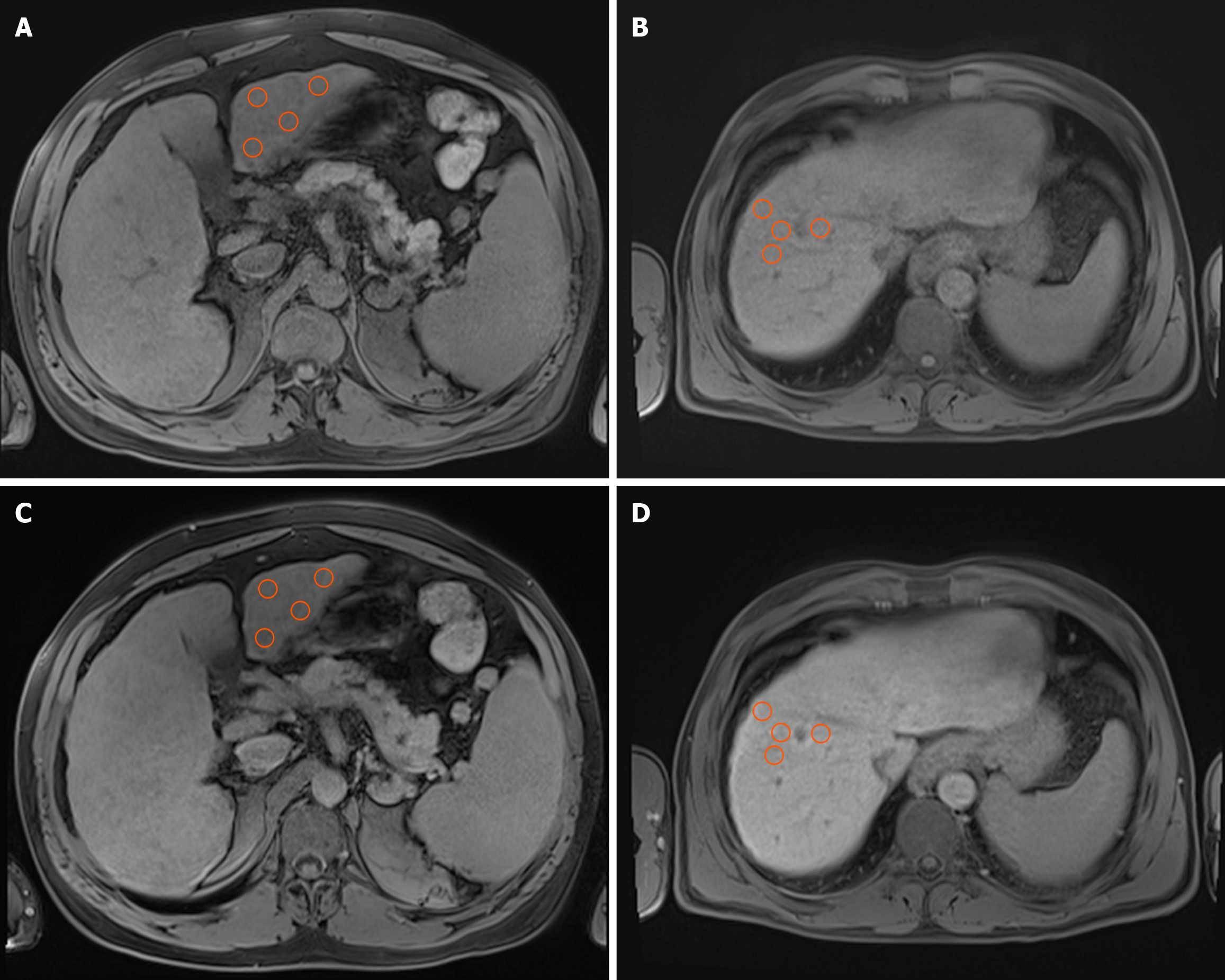

To reduce potential variability from manual ROI placement, ROIs were positioned using standardized coordinates based on vascular landmarks (with the portal vein bifurcation as the reference point), following recommendations for reproducibility in radiomics modeling[27]. Within each chosen segment, four independent ROIs were placed, and the final SI value for each segment was determined by averaging these four individual measurements. This methodology was applied to both unenhanced (native) images and hepatobiliary-phase images (Figure 1). For each patient, SI was mea

Statistical analyses were performed utilizing SPSS software, version 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States) and R version 4.5.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Data are expressed as the mean ± SD. Correlations between imaging parameters (HE and SI) and clinical scores (Child-Pugh, MELD 3.0, ALBI, FIB-4), the FLIS score, liver stiffness (VCTE), and HVPG were assessed using Pearson or Spearman correlation coefficients (ρ), depending on the data type and distribution.

To minimize variability resulting from manual ROI placement, intraobserver agreement analysis was conducted. All ROI measurements were repeated for the entire study cohort (n = 100) by the same observer, who was blinded to the initial results. Agreement was assessed using the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC; two-way mixed-effects, single-rater, absolute agreement model), coefficient of variation (CV%), and Bland-Altman analysis. ICCs were interpreted as: < 0.50 poor, 0.50-0.75 moderate, 0.75-0.90 good, and > 0.90 excellent reproducibility. To assess the variations in HE and SI based on FLIS score categories, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted, followed by Tukey’s honest significant difference (HSD) post-hoc test. For HE, polynomial contrasts were employed to test for linear trends across FLIS scores, and deviations from linearity were also assessed. Homogeneity of variances was tested with Levene’s test. When this assumption was violated, Welch’s ANOVA was performed as a robust alternative. Effect sizes were reported using partial eta squared (η2).

Comparisons of HE values between different clinical outcome groups (with vs without decompensation, with vs without HCC, and survivors vs deceased) were performed utilizing independent samples t-tests. Time-to-event analyses for decompensation and overall mortality were performed using Cox proportional hazards models. HE was evaluated as a continuous variable per 10-unit increase, for individual segments (VI, VIII, III, caudate lobe) and for the global value. Univariate Cox regressions were conducted first, followed by multivariable models adjusted for MELD 3.0, disease etiology, and prior HCC before the MRI. Hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) are reported. Receiver operating characteristic analysis was performed to evaluate the discriminatory ability of HE, FLIS, MELD 3.0, and ALBI for predicting mortality and decompensation. For each predictor, the area under the (receiver operating characteristic [ROC]) curve (AUC) with 95%CIs was calculated. Optimal cut-off values were identified using the Youden index, and the diagnostic performance was summarized with sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value. Pairwise comparisons of AUCs between HE measures and FLIS, MELD 3.0, or ALBI were conducted using DeLong’s test, with Benjamini-Hochberg correction for multiple comparisons. Sensitivity analyses were conducted to evaluate the potential impact of confounding factors. Separate analyses were conducted after excluding patients with a history of HCC before MRI and within subgroups based on disease etiology (viral vs alcoholic). The mixed-etiology group was not analyzed separately due to a small sample size (n = 6). To account for multiple testing, a false discovery rate (FDR) adjustment was applied using the Benjamini-Hochberg method.

We assessed the additional prognostic value of HE measures - segment VI HE and global HE - beyond a reference model comprising FLIS, MELD 3.0, etiology, and prior HCC status. For each endpoint, namely decompensation and death, Cox proportional hazards models were fitted for the reference specification (M0) and two extensions (M1a: M0 + segment VI HE; M1b: M0 + global HE). Model-based risks were calculated at predefined horizons of 12 months and 24 months; the binary outcome for horizon-based analyses was defined as “event by fixed horizon” (yes/no). The time-dependent AUC and Brier score were computed at 12 months and 24 months, employing inverse probability of censoring weighting. Changes in discrimination and calibration were summarized as ΔAUC and ΔBrier relative to M0. Incremental classification performance was quantified using both categorical and continuous net reclassification improvement (NRI) metrics, comparing M1a and M1b with M0 at each horizon. The risk categories for the categorical NRI were < 10%, 10%-20%, and > 20%, selected a priori to represent low, intermediate, and high clinical risk. The total NRI and its components for cases (NRI event; upward movement desirable) and non-cases (NRI non-event; downward movement desirable) were reported. Clinical utility was evaluated via decision-curve analysis (DCA) and the quantitative net benefit, under an opt-in policy (treat if predicted risk ≥ threshold probability). Decision curves were plotted across 5%-30% to illustrate net benefit. Primary decision thresholds of 10% and 20% were predefined for objective, threshold-specific summaries. At each threshold and horizon, the incremental net benefit relative to M0 (ΔNB) and its 95%CI were reported. For interpretability, ΔNB was translated into the net reduction in interventions per 100 patients at the corresponding true-positive rate. Calibration at 12 months was visually evaluated through plots of observed outcome proportions by deciles of predicted risk against the 45° line for M0, M1a, and M1b. As a quantitative sensitivity analysis, logistic calibration-in-the-large (intercept) and calibration slope were estimated by regressing the 12-month outcome on the logit of predicted risk. CIs for NRI and ΔNB were derived using a nonparametric bootstrap with 1000 replicates at the specified analysis horizons and thresholds. P value/q value (adjusted P value) less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

A total of 100 patients participated in the study, with a mean age of 65.65 ± 9.77 years. Most participants were male (68%) and diagnosed with ACLD caused by viral (53%), alcoholic (41%), or mixed (6%) etiologies. At the time of the MRI examination, 20 patients had a history of treated HCC. The average liver stiffness was 30.18 ± 22.86 kPa, whereas the mean HVPG was 12.38 ± 5.46 mmHg. During the follow-up period after the MRI examination, 37 patients experienced episodes of clinical decompensation. HCC developed in 25 patients during surveillance. None of the patients underwent liver transplantation, either because they were not eligible or because there was no immediate therapeutic indication. Additionally, 13 patients died during the post-MRI follow-up period. Analysis of hepatic SI revealed an overall increase in SI values during the hepatobiliary phase compared to the native phase across all evaluated liver segments. The mean values exhibited a uniform distribution among the segments, with minimal variation observed. Furthermore, HE values were consistent across the segments. The distribution of FLIS scores was as follows: Score 1 (n = 2), score 2 (n = 13), score 3 (n = 9), score 4 (n = 19), score 5 (n = 15), and score 6 (n = 42). The biochemical characteristics, mean SI, and HE in the study cohort are delineated in Table 2.

| Parameter/score | mean ± SD |

| Platelets (× 103/µL) | 126.12 ± 73.48 |

| AST (U/L) | 62.65 ± 54.04 |

| ALT (U/L) | 43.61 ± 38.15 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 2.40 ± 2.76 |

| Sodium (mEq/L) | 135.98 ± 4.03 |

| Potassium (mEq/L) | 4.18 ± 0.54 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.86 ± 0.23 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.64 ± 0.79 |

| INR | 1.37 ± 0.40 |

| MELD 3.0 score | 13.75 ± 6.14 |

| ALBI score | -2.14 ± 0.83 |

| FIB-4 index | 6.58 ± 6.21 |

| Native SI segment III | 147.25 ± 26.15 |

| Native SI segment VI | 167.20 ± 24 |

| Native SI segment VIII | 153.90 ± 19.57 |

| Native SI caudate lobe | 161.91 ± 22.95 |

| Native SI global | 157.56 ± 21.28 |

| Hepatobiliary SI segment III | 230.75 ± 55.40 |

| Hepatobiliary SI segment VI | 262.60 ± 59.38 |

| Hepatobiliary SI segment VIII | 245.85 ± 50.18 |

| Hepatobiliary SI caudate lobe | 255.50 ± 57.92 |

| Hepatobiliary SI global | 248.68 ± 53.90 |

| HE segment III | 83.50 ± 37.16 |

| HE segment VI | 95.40 ± 43.01 |

| HE segment VIII | 91.95 ± 36.72 |

| HE caudate lobe | 93.59 ± 40.90 |

| HE global | 91.11 ± 38.15 |

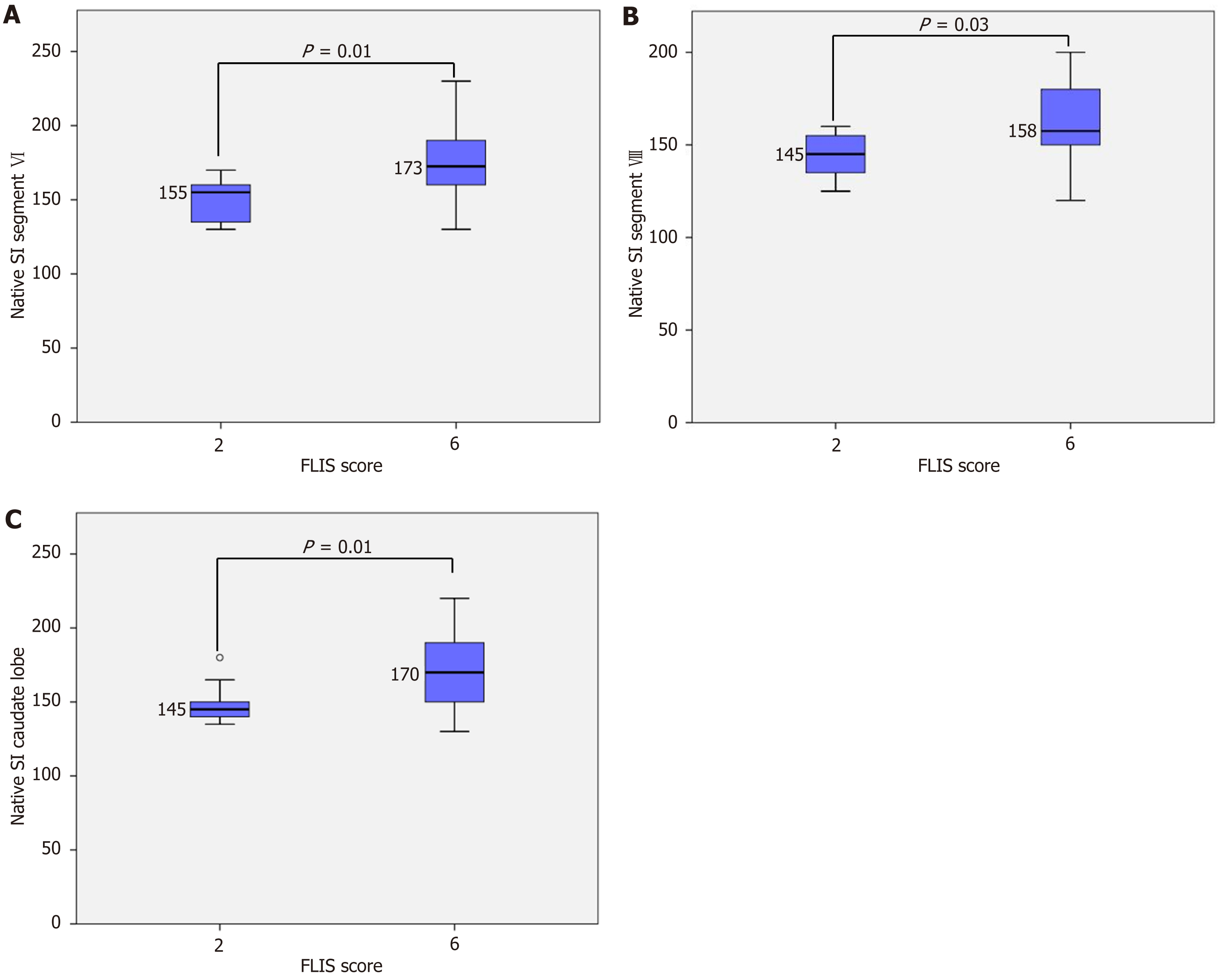

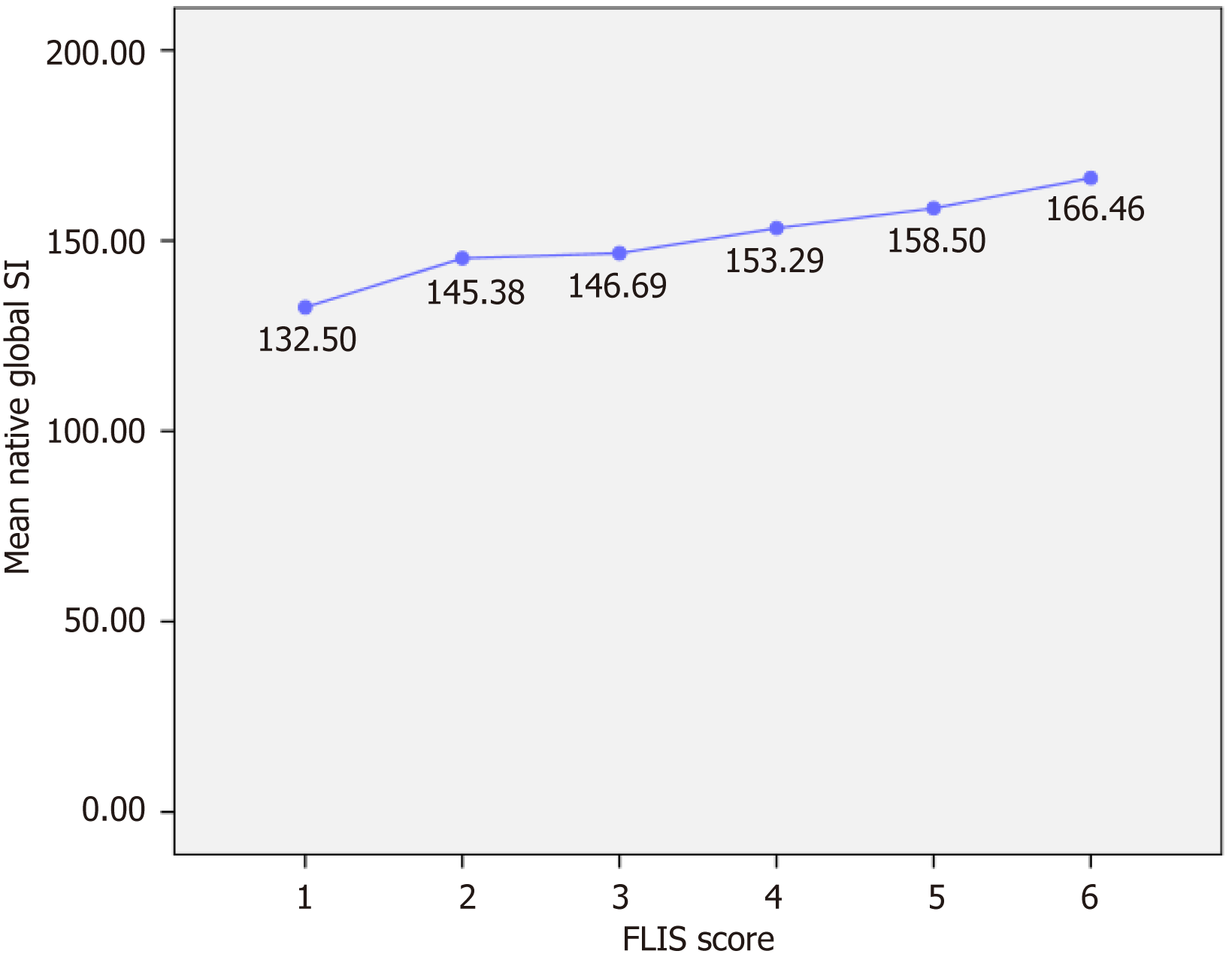

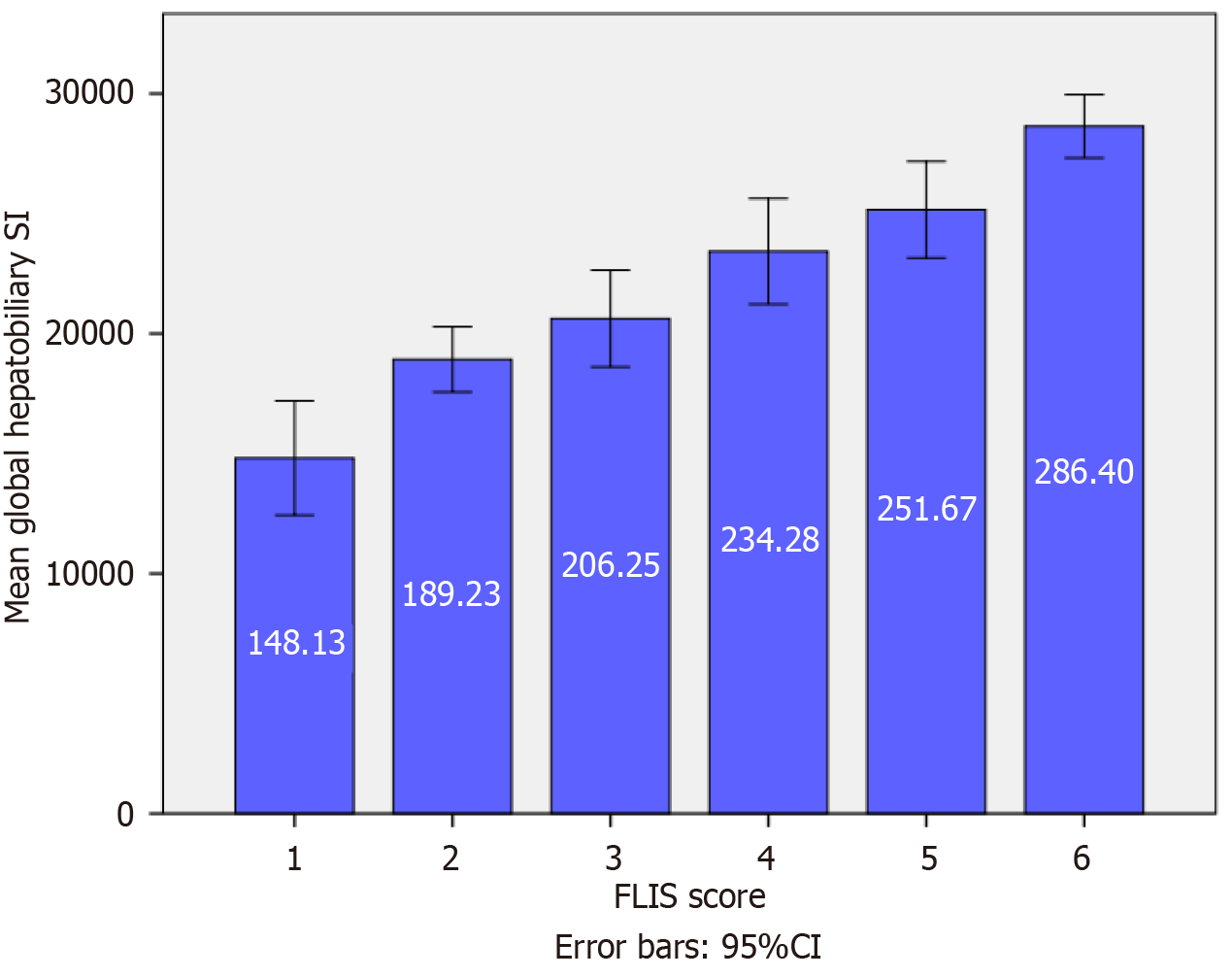

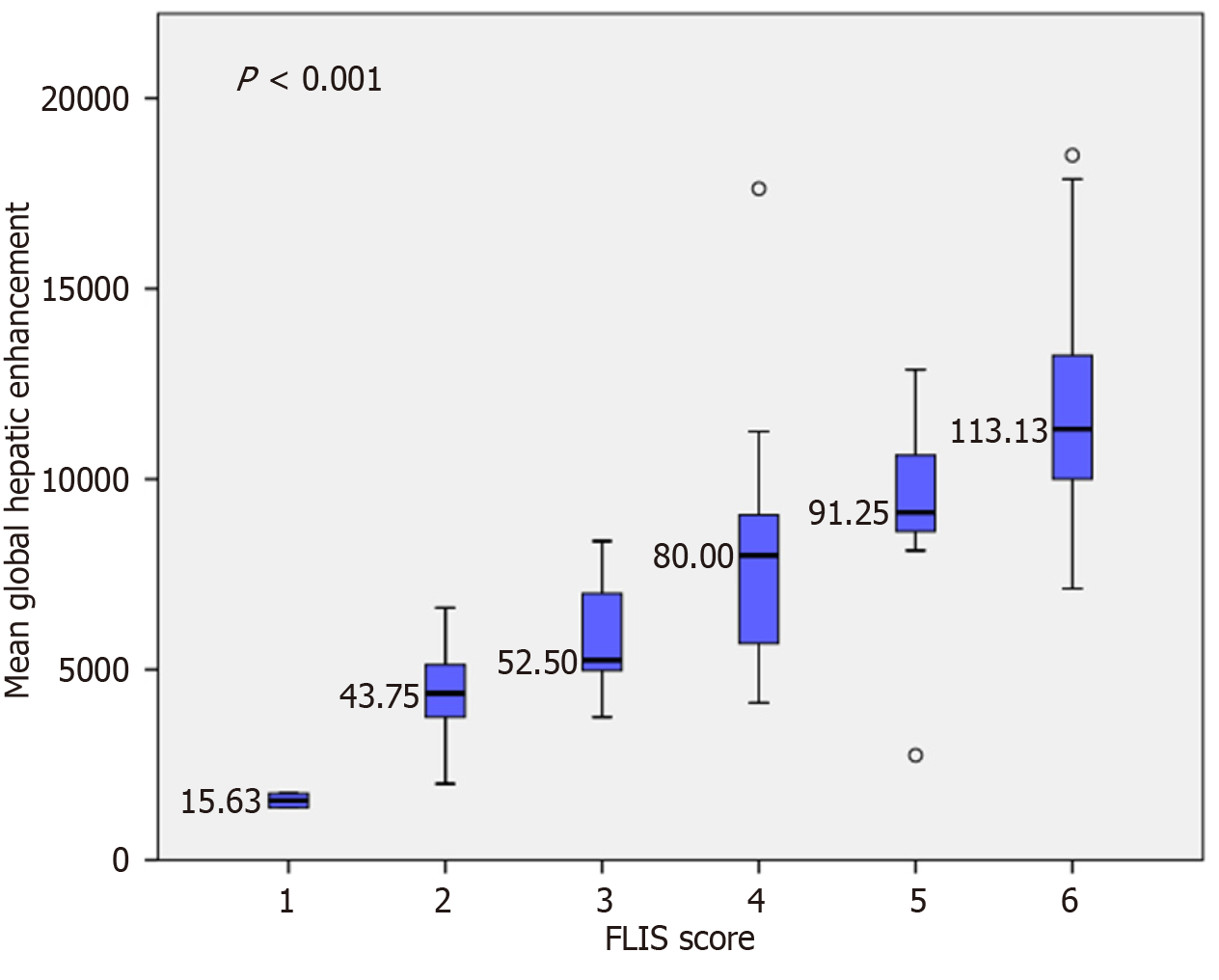

Variation in segmental and global SI according to FLIS score: In the native phase, a statistically significant difference in segmental SI was observed only between FLIS class 2 and FLIS class 6 (Figure 2). Conversely, global SI did not demonstrate substantial differences across FLIS categories (Figure 3). These results indicate that native SI is comparatively independent of hepatocellular function. Significant differences in hepatobiliary-phase SI were observed among the various FLIS score groups across all analyzed regions (P < 0.001). SI values showed a consistent increase, correlating with higher FLIS scores at both the segmental and global levels. The highest discriminatory ability was seen in the SI of segment VI and the global SI. The post hoc Tukey’s HSD analysis demonstrated statistically significant differences not only between distant FLIS categories (e.g., FLIS 1-2 vs FLIS 4-6) but also between neighboring scores (e.g., FLIS 4 vs FLIS 6, FLIS 5 vs FLIS 6). Segments III, VIII, and the caudate lobe exhibited similar trends, although they did not significantly differentiate between closely related FLIS scores. Overlaps were observed between FLIS 1 and 2, FLIS 2 and 3, and FLIS 5 and 6. The global hepatobiliary phase SI exhibited a gradual increase from 148.13 in FLIS 1 to 286.40 in FLIS 6 (P < 0.001). Figure 4 illustrates the distribution of mean global SI values according to the FLIS score.

A statistically significant positive correlation was observed between the FLIS score and hepatobiliary-phase SI at both the segmental and global levels. The strongest associations were seen for segment VI SI and global SI. By contrast, hepatobiliary-phase SI showed moderate yet statistically significant negative correlations with established clinical scores, including the Child-Pugh score, MELD 3.0, ALBI, and FIB-4. The strongest correlations occurred with MELD 3.0 and ALBI (especially for segment VI), as well as Child-Pugh (notably at the global level and in the caudate lobe). Additionally, hepatobiliary-phase SI demonstrated significant negative correlations with liver stiffness measured by VCTE, at both segmental and global levels. Conversely, no significant correlation was found between SI and HVPG. Detailed correlation coefficients and significance levels are provided in Table 3.

| Region | FLIS | Child-Pugh | MELD 3.0 | ALBI | FIB-4 | Liver stiffness | HVPG |

| SI segment III | 0.661a | -0.496a | -0.521a | -0.519a | -0.222a | -0.389a | -0.167 (P = 0.208) |

| SI segment VI | 0.763a | -0.589a | -0.623a | -0.603a | -0.268a | -0.390a | -0.267 (P = 0.094) |

| SI segment VIII | 0.683a | -0.463a | -0.545a | -0.493a | -0.259a | -0.422a | -0.302 (P = 0.067) |

| SI caudate lobe | 0.727a | -0.532a | -0.563a | -0.562a | -0.266a | -0.461a | -0.289 (P = 0.076) |

| Global SI | 0.736a | -0.540a | -0.584a | -0.565a | -0.263a | -0.429a | -0.261 (P = 0.099) |

In the entire cohort (n = 100), HE steadily increased with higher FLIS categories across all liver segments (Figure 5). Segment VI exhibited the strongest association (F = 38.448, P < 0.001; partial η2 = 0.672), with the mean HE rising from 7.5 at FLIS 1 to 129.9 at FLIS 6. Global HE also showed a similarly strong relationship (F = 28.060, P < 0.001; η2 = 0.599), while segments VIII, III, and the caudate lobe all demonstrated significant increases with large effect sizes (η2 ranging from 0.502 to 0.565; Table 4). Polynomial contrasts confirmed significant linearity across all regions (all P < 0.001), with no deviations from linearity observed (all P > 0.49). Homogeneity of variances was confirmed through Levene’s tests (all P > 0.05). Post-hoc Tukey’s HSD analyses indicated that HE values at higher FLIS scores (5-6) were significantly greater than those at lower categories (1-3) in all regions (all P < 0.01). Conversely, differences between neighboring categories (e.g., 1 vs 2, 2 vs 3) were less consistent. Sensitivity analyses were conducted to evaluate the influence of HCC status and disease etiology. Excluding patients with prior HCC (n = 80) yielded results very similar to those of the entire cohort (Table 4). Segment VI again showed the strongest association (F = 36.974, P < 0.001; η2 = 0.713), and global HE maintained a large effect size (F = 26.237, P < 0.001; η2 = 0.639). Tukey’s HSD test confirmed significant differences between the low (FLIS 1-3) and high (FLIS 5-6) groups.

| Region | F (ANOVA) | P value | Partial η² | Linear trend F | Linear trend P | Deviation F | Deviation P | Levene’s P |

| Full cohort (n = 100) | ||||||||

| Segment VI | 38.448 | < 0.001 | 0.672 | 190.171 | < 0.001 | 0.518 | 0.723 | 0.062 |

| Segment VIII | 18.960 | < 0.001 | 0.502 | 91.378 | < 0.001 | 0.855 | 0.494 | 0.246 |

| Caudate lobe | 24.369 | < 0.001 | 0.565 | 120.883 | < 0.001 | 0.240 | 0.915 | 0.340 |

| Segment III | 19.393 | < 0.001 | 0.508 | 95.767 | < 0.001 | 0.299 | 0.878 | 0.157 |

| Global HE | 28.060 | < 0.001 | 0.599 | 138.949 | < 0.001 | 0.337 | 0.852 | 0.072 |

| Non-HCC subgroup (n = 80) | ||||||||

| Segment VI | 36.974 | < 0.001 | 0.714 | 179.371 | < 0.001 | 1.375 | 0.251 | 0.086 |

| Segment VIII | 16.262 | < 0.001 | 0.524 | 77.487 | < 0.001 | 0.956 | 0.437 | 0.457 |

| Caudate lobe | 23.305 | < 0.001 | 0.612 | 114.939 | < 0.001 | 0.396 | 0.811 | 0.429 |

| Segment III | 17.696 | < 0.001 | 0.545 | 85.235 | < 0.001 | 0.811 | 0.522 | 0.174 |

| Global HE | 26.237 | < 0.001 | 0.639 | 128.016 | < 0.001 | 0.792 | 0.534 | 0.125 |

| Viral subgroup (n = 53) | ||||||||

| Segment VI | 15.968 | < 0.001 | 0.571 | 61.566 | < 0.001 | 0.769 | 0.517 | 0.017 |

| Segment VIII | 6.230 | < 0.001 | 0.342 | 22.909 | < 0.001 | 0.671 | 0.574 | 0.547 |

| Caudate lobe | 11.256 | < 0.001 | 0.484 | 43.029 | < 0.001 | 0.665 | 0.578 | 0.061 |

| Segment III | 8.940 | < 0.001 | 0.426 | 34.033 | < 0.001 | 0.576 | 0.634 | 0.152 |

| Global HE | 11.244 | < 0.001 | 0.484 | 43.239 | < 0.001 | 0.579 | 0.632 | 0.035 |

| Alcoholic subgroup (n = 41) | ||||||||

| Segment VI | 22.325 | < 0.001 | 0.761 | 103.808 | < 0.001 | 1.955 | 0.123 | 0.751 |

| Segment VIII | 9.116 | < 0.001 | 0.566 | 41.884 | < 0.001 | 0.925 | 0.461 | 0.636 |

| Caudate lobe | 7.551 | < 0.001 | 0.519 | 36.680 | < 0.001 | 0.269 | 0.896 | 0.849 |

| Segment III | 8.439 | < 0.001 | 0.566 | 38.439 | < 0.001 | 0.938 | 0.453 | 0.174 |

| Global HE | 12.871 | < 0.001 | 0.648 | 60.830 | < 0.001 | 0.881 | 0.485 | 0.803 |

Stratification by etiology confirmed the same pattern (Table 4). In the viral subgroup (n = 53), HE increased significantly across FLIS categories, with Segment VI showing the most notable effect (F = 15.968, P < 0.001; η2 = 0.571). Levene’s test indicated heterogeneity of variances for Segment VI (P = 0.017) and global HE (P = 0.035), while all other regions met the homogeneity criteria (P > 0.05). Robust testing confirmed that both associations remained significant (Welch F = 36.684, P < 0.001 for Segment VI; Welch F = 54.844, P < 0.001 for global HE). Post-hoc Tukey’s HSD, where applicable, revealed significant differences between low (FLIS 2-3) and high (FLIS 6) categories, with partial overlap among intermediate categories. In the alcoholic subgroup (n = 41), the associations were even more pronounced, especially in Segment VI (F = 22.325, P < 0.001; η2 = 0.762) and global HE (F = 12.871, P < 0.001; η2 = 0.648). Post-hoc tests (Tukey’s HSD and Games-Howell) were not performed within this subgroup due to small and uneven group sizes. Nonetheless, strong linear trends persisted across all regions (all P < 0.001). These results confirm the robustness of the associations. The small sample size of the mixed-etiology group (n = 6) precluded meaningful analysis, and therefore, it was not evaluated separately.

Global HE showed a strong positive correlation with FLIS across the entire cohort (ρ = 0.797, q < 0.001). Similar relationships were seen in the non-HCC subgroup (ρ = 0.820, q < 0.001) and in the alcoholic subgroup (ρ = 0.796, q < 0.001). In patients with viral etiology, the correlation remained moderately strong (ρ = 0.649, q < 0.001). Segmental analyses revealed strong patterns, with enhancement values from segment VI and the caudate lobe consistently showing the highest correlations with FLIS (e.g., segment VI, ρ = 0.819 in the entire cohort, ρ = 0.858 in non-HCC patients, and ρ = 0.834 in alcoholic patients). Other segments displayed slightly lower but still significant coefficients, confirming that the relationship was not limited to a single hepatic region.

Inverse correlations were found between global HE and three clinical severity indices. In the entire cohort, HE showed a negative correlation with Child-Pugh score (ρ = -0.589, P < 0.001), MELD 3.0 (ρ = -0.658, P < 0.001), and ALBI grade (ρ =

By contrast, correlations with FIB-4 were weaker across all groups (e.g., global HE: Ρ = -0.308 in the whole cohort, -0.301 in non-HCC, -0.318 in viral, and -0.123 in alcoholic). In the alcoholic subgroup, segmental correlations did not reach statistical significance after FDR adjustment (q = 0.269-0.936), indicating that the fibrosis burden, as measured by FIB-4, is less closely related to hepatocellular function than HE or FLIS. A complete set of correlation coefficients and adjusted q-values for global and segmental HE with FLIS and each clinical severity score across all cohorts is shown in Table 5.

| Cohort | Region | FLIS | Child-Pugh | MELD 3.0 | ALBI | FIB-4 |

| Full cohort (n = 100) | HE segment VI | 0.819a | -0.611a | -0.683a | -0.624a | -0.306a |

| HE segment VIII | 0.718a | -0.469a | -0.584a | -0.490a | -0.300a | |

| HE caudate lobe | 0.765a | -0.592a | -0.634a | -0.590a | -0.312a | |

| HE segment III | 0.741a | -0.580a | -0.625a | -0.579a | -0.253a | |

| Global HE | 0.797a | -0.589a | -0.658a | -0.599a | -0.308a | |

| Non-HCC (n = 80) | HE segment VI | 0.858a | -0.616a | -0.649a | -0.624a | -0.301a |

| HE segment VIII | 0.716a | -0.475a | -0.551a | -0.463a | -0.278a | |

| HE caudate lobe | 0.790a | -0.601a | -0.599a | -0.576a | -0.302a | |

| HE segment III | 0.761a | -0.582a | -0.583a | -0.568a | -0.265a | |

| Global HE | 0.820a | -0.596a | -0.622a | -0.591a | -0.301a | |

| Viral (n = 53) | HE segment VI | 0.656a | -0.423a | -0.574a | -0.444a | -0.287a |

| HE segment VIII | 0.589a | -0.320a | -0.542a | -0.410a | -0.287a | |

| HE caudate lobe | 0.633a | -0.456a | -0.533a | 0.485a | -0.342a | |

| HE segment III | 0.610a | -0.471a | -0.631a | -0.530a | -0.312a | |

| Global HE | 0.649a | -0.433a | -0.594a | -0.485a | -0.318a | |

| Alcoholic (n = 41) | HE segment VI | 0.834a | -0.603a | -0.611a | -0.594a | -0.148 (q = 0.418) |

| HE segment VIII | 0.714a | -0.412a | -0.431a | -0.396a | -0.198 (q = 0.269) | |

| HE caudate lobe | 0.739a | -0.537a | -0.513a | -0.476a | -0.074 (q = 0.682) | |

| HE segment III | 0.707a | -0.530a | -0.414a | -0.458a | -0.013 (q = 0.936) | |

| Global HE | 0.796a | -0.546a | -0.531a | -0.511a | -0.123 (q = 0.492) |

In the entire cohort (n = 100), HE was inversely related to liver stiffness in all segments (ρ = from -0.418 to -0.503, all q ≤ 0.002), with the strongest link found in segment VIII (ρ = -0.503, q = 0.001). In the non-HCC subgroup (n = 80), this relationship stayed consistent (ρ = -0.358 to -0.470, q = 0.003-0.014). In patients with viral cirrhosis (n = 53), the relationship between liver stiffness and disease progression was weakened. Nominal correlations appeared for segment VIII and III (ρ = -0.328 and -0.323), but none remained significant after FDR correction (all q ≥ 0.059). Conversely, in alcoholic cirrhosis (n = 41), HE showed strong inverse correlations with hepatic rigidity across all regions (ρ = -0.455 to -0.604, q = 0.020-0.038).

For HVPG, analyses were limited to the 26 patients who underwent invasive measurement. In this subgroup, HE correlated inversely with HVPG in four of five segments (ρ = -0.340 to -0.389, q = 0.042-0.049), except for segment III (ρ =

| Cohort | Region | Liver stiffness (ρ/q) | HVPG (ρ/q) |

| Full cohort (n = 100) | HE segment VI | -0.428/0.002a | -0.345/0.049a |

| HE segment VIII | -0.503/0.001a | -0.389/0.042a | |

| HE caudate lobe | -0.477/0.001a | -0.362/0.049a | |

| HE segment III | -0.418/0.002a | -0.232/0.127 | |

| Global HE | -0.470/0.001a | -0.340/0.049a | |

| Non-HCC (n = 80) | HE segment VI | -0.358/0.014a | -0.200/0.261 |

| HE segment VIII | -0.470/0.003a | -0.235/0.255 | |

| HE caudate lobe | -0.447/0.003a | -0.169/0.261 | |

| HE segment III | -0.399/0.008a | -0.049/0.416 | |

| Global HE | -0.430/0.003a | -0.167/0.261 | |

| Viral (n = 53) | HE segment VI | -0.211/0.127 | 0.160/0.492 |

| HE segment VIII | -0.328/0.059 | -0.081/0.492 | |

| HE caudate lobe | -0.217/0.120 | -0.042/0.492 | |

| HE segment III | -0.323/0.059 | 0.071/0.492 | |

| Global HE | -0.286/0.120 | 0.093/0.492 | |

| Alcoholic (n = 41) | HE segment VI | -0.513/0.022a | -0.552/0.061 |

| HE segment VIII | -0.604/0.020a | -0.533/0.061 | |

| HE caudate lobe | -0.533/0.020a | -0.508/0.061 | |

| HE segment III | -0.455/0.038a | -0.433/0.092 | |

| Global HE | -0.552/0.020a | -0.524/0.061 |

Within the entire cohort (n = 100), global HE did not differ significantly between patients who developed HCC and those who did not (87.5 ± 37.9 vs 102.0 ± 37.7). Conversely, patients who experienced decompensation showed significantly lower HE compared to those who remained compensated (74.5 ± 39.1 vs 100.9 ± 34.3). A similar pattern was seen regarding mortality, with patients who died displaying reduced HE relative to survivors (69.5 ± 42.5 vs 94.3 ± 36.7). These associations persisted within the subgroup with no prior HCC (n = 80). HE remained significantly lower in patients experiencing decompensation (73.5 ± 39.2 vs 93.7 ± 33.6) and in those who died from the condition (63.0 ± 31.3 vs 95.3 ± 37.0). Conversely, differences in the occurrence of HCC were not statistically significant (q = 0.152).

Within etiologic subgroups, results showed greater variability due to the small number of events. In viral cirrhosis (n = 53), none of the outcome comparisons (HCC, decompensation, death) remained statistically significant after FDR correction (all q > 0.140). In alcoholic cirrhosis (n = 41), patients experiencing decompensation again showed a markedly lower HE (61.6 ± 32.7 vs 94.5 ± 27.1, P = 0.001, q = 0.003; d = 1.09), while no significant differences were seen for HCC (HCC) or mortality after adjustment. The mixed-etiology cohort (n = 6) was excluded from analysis due to an insufficient sample size. Detailed mean values, t-test interpretations, and FDR-adjusted q-values for all segments are shown in Table 7.

| Cohort | Outcome | Group | Mean HE ± SD | t (df) | P value | q value | Cohen’s d |

| Full cohort (n = 100) | HCC development | No HCC | 87.48 ± 37.86 | -1.662 (98) | 0.100 | 0.100 | 0.384 |

| HCC | 102 ± 37.71 | ||||||

| Decompensation | No decompensation | 100.87 ± 34.30 | 3.526 (98) | 0.001a | 0.003a | 0.717 | |

| Decompensation | 74.48 ± 39.07 | ||||||

| Mortality | Survivor | 94.34 ± 36.65 | 2.231 (98) | 0.028a | 0.042a | 0.625 | |

| Dead | 69.52 ± 42.47 | ||||||

| Non-HCC (n = 80) | HCC development | No HCC | 81.12 ± 37.64 | -1.448 (78) | 0.152 | 0.152 | 0.379 |

| HCC | 95 ± 35.45 | ||||||

| Decompensation | No decompensation | 93.66 ± 33.63 | 2.478 (78) | 0.015a | 0.026a | 0.552 | |

| Decompensation | 73.50 ± 39.16 | ||||||

| Mortality | Survivor | 95.26 ± 37.02 | 2.622 (78) | 0.011a | 0.033a | 0.941 | |

| Dead | 63 ± 31.29 | ||||||

| Viral cirrhosis (n = 53) | HCC development | No HCC | 98.44 ± 37.70 | -1.713 (51) | 0.093 | 0.140 | 0.517 |

| HCC | 116.69 ± 32.74 | ||||||

| Decompensation | No decompensation | 105.57 ± 34.89 | 1.293 (51) | 0.202 | 0.303 | 0.368 | |

| Decompensation | 91.56 ± 39.24 | ||||||

| Mortality | Survivor | 105.99 ± 34.54 | 1.181 (51) | 0.243 | 0.243 | 0.448 | |

| Dead | 83.44 ± 62.18 | ||||||

| Alcoholic cirrhosis (n = 41) | HCC development | No HCC | 77.57 ± 33.92 | 0.523 (39) | 0.604 | 0.604 | 0.218 |

| HCC | 70.78 ± 28.05 | ||||||

| Decompensation | No decompensation | 94.49 ± 27.14 | 5.523 (39) | 0.001a | 0.003a | 1.095 | |

| Decompensation | 61.57 ± 32.72 | ||||||

| Mortality | Survivor | 79.88 ± 32.01 | 1.357 (39) | 0.182 | 0.273 | 0.505 | |

| Dead | 63.33 ± 33.40 |

In univariate Cox regression, lower HE (per 10-unit decrease) was consistently associated with increased risk of both decompensation and death. For decompensation, all segmental and global HE measures were significant predictors (HRs = 0.77-0.81; all P < 0.001, FDR < 0.001). For mortality, the associations showed a similar trend, with significant predictive value across all segments except segment VIII (HR = 0.75-0.80; all P ≤ 0.004, FDR ≤ 0.005). After adjusting for MELD 3.0, etiology, and prior HCC, only the segment VI HE remained independently linked to decompensation (HR = 0.87, 95%CI: 0.77-0.99, P = 0.029). In contrast, no HE measure was independently associated with mortality. The full Cox regression results are presented in Table 8.

| Model | Endpoint | Predictor | HR (95%CI) | P (raw) | q (FDR) |

| Univariate | Decompensation | HE segment VI | 0.77 (0.70-0.85) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| HE segment VIII | 0.81 (0.73-0.90) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||

| HE segment III | 0.79 (0.70-0.88) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||

| HE caudate lobe | 0.79 (0.72-0.87) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||

| HE global | 0.77 (0.69-0.86) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||

| Mortality | HE segment VI | 0.78 (0.68-0.90) | < 0.001 | 0.004 | |

| HE segment VIII | 0.86 (0.74-1.01) | 0.065 | 0.065 | ||

| HE segment III | 0.75 (0.62-0.90) | 0.002 | 0.005 | ||

| HE caudate lobe | 0.80 (0.69-0.93) | 0.004 | 0.005 | ||

| HE global | 0.79 (0.67-0.93) | 0.004 | 0.005 | ||

| Adjusted (MELD3.0, etiology, prior HCC)1 | Decompensation | HE segment VI | 0.87 (0.77-0.99) | 0.029 | 0.145 |

| HE segment VIII | 0.93 (0.83-1.05) | 0.248 | 0.310 | ||

| HE segment III | 0.91 (0.80-1.04) | 0.178 | 0.237 | ||

| HE caudate lobe | 0.92 (0.81-1.04) | 0.178 | 0.237 | ||

| HE global | 0.89 (0.79-1.02) | 0.108 | 0.180 | ||

| Mortality | HE segment VI | 0.87 (0.69-1.09) | 0.227 | 0.695 | |

| HE segment VIII | 1.07 (0.87-1.30) | 0.417 | 0.695 | ||

| HE segment III | 0.88 (0.69-1.11) | 0.284 | 0.710 | ||

| HE caudate lobe | 0.97 (0.78-1.20) | 0.733 | 0.733 | ||

| HE global | 0.94 (0.74-1.20) | 0.627 | 0.783 |

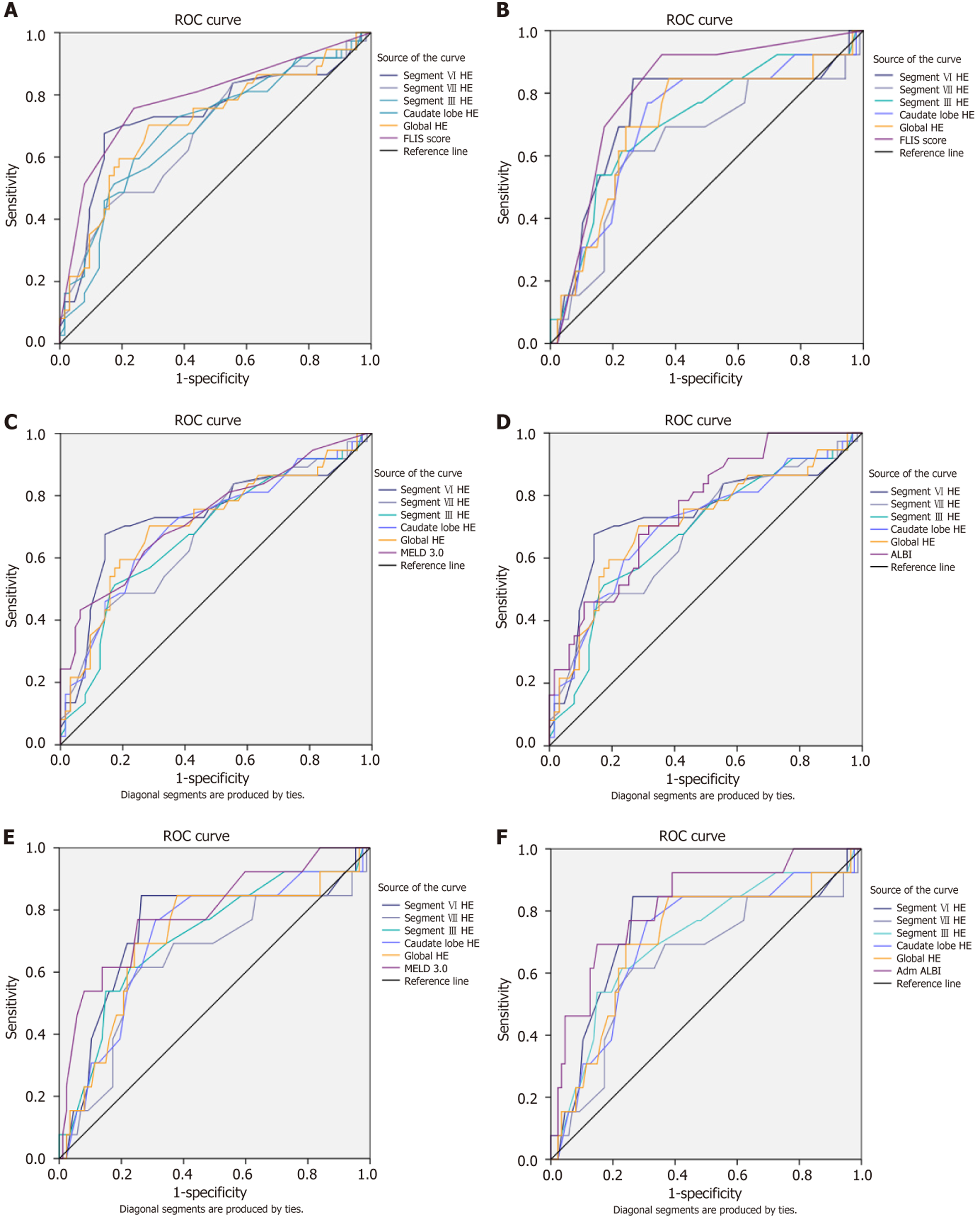

For decompensation, FLIS achieved the highest discriminatory accuracy, with an AUC of 0.79 (95%CI: 0.69-0.88). Among HE measures, segment VI performed best, with an AUC of 0.74 (95%CI: 0.62-0.85), and a Youden-derived cut-off of 75, which resulted in a sensitivity of 0.68, a specificity of 0.86, and a negative predictive value (NPV) of 0.88. Global HE showed similar accuracy, with an AUC of 0.71 (95%CI: 0.60-0.82), while other segmental HE measures had slightly lower AUCs, ranging from 0.68 to 0.70. In direct comparisons, most HE measures were significantly less accurate than FLIS, although segment VI showed no significant difference (ΔAUC = -0.05, q = 0.123). Compared to clinical scores, MELD 3.0 (AUC = 0.73, 95%CI: 0.63-0.83) and ALBI (AUC = 0.77, 95%CI: 0.67-0.86) slightly outperformed most HE parameters, with ΔAUC values from -0.05 to -0.11. However, these differences were not statistically significant, and segment VI performed closest to both scores (ΔAUC = 0.01 vs MELD; ΔAUC = -0.04 vs ALBI). These findings suggest that segment VI HE provides clinically relevant discrimination, especially as a non-invasive imaging biomarker.

For mortality prediction, ALBI achieved the best performance (AUC = 0.82, 95%CI: 0.69-0.95), followed by FLIS (AUC = 0.81, 95%CI: 0.69-0.93). Among HE measures, segment VI again performed best (AUC = 0.74, 95%CI: 0.57-0.91), with the same cut-off of 75, providing sensitivity of 0.85, specificity of 0.74, and an excellent NPV of 0.97. Global HE achieved an AUC of 0.71 (95%CI: 0.54-0.84), while other segmental measures ranged from 0.64 to 0.71. In direct comparisons, segment VI HE did not differ significantly from either FLIS (ΔAUC = -0.07, q = 0.293) or ALBI (ΔAUC = -0.08, q = 0.220). By contrast, segment VIII HE was significantly inferior to FLIS (ΔAUC = –0.18, q = 0.025). MELD 3.0 performed similarly to HE (AUC = 0.79, 95%CI: 0.64–0.94), with ΔAUC values for segment VI vs MELD remaining small (-0.05, not significant). Overall, ALBI proved to be the most accurate score for mortality; however, HE - particularly segment VI - maintained a strong discriminative ability and a very high NPV, reinforcing its potential as a “rule-out” marker. Detailed AUC values, optimal cut-offs, diagnostic metrics, and pairwise DeLong comparisons are summarized in Tables 9 and 10, with the corresponding ROC curves illustrated in Figure 6.

| Marker | AUC (95%CI) | Youden cut-off | Se | Sp | PPV | NPV | Δ HE vs FLIS (q) | Δ HE vs MELD 3.0 (q) | Δ HE vs ALBI (q) |

| FLIS | 0.79 (0.69-0.88) | 4.5 | 0.76 | 0.76 | 0.57 | 0.88 | - | - | - |

| MELD 3.0 | 0.73 (0.63-0.86 | 18.5 | 0.43 | 0.94 | 0.8 | 0.74 | - | - | - |

| ALBI | 0.77 (0.68-0.86 | -2.1 | 0.70 | 0.73 | 0.60 | 0.81 | - | - | - |

| HE segment VI | 0.74 (0.62-0.85) | 75 | 0.68 | 0.86 | 0.64 | 0.88 | -0.05 (0.123) | 0.01 (0.964) | -0.04 (0.580) |

| HE segment VIII | 0.68 (0.55-0.79) | 67.5 | 0.43 | 0.86 | 0.64 | 0.72 | -0.08 (0.014) | -0.05 (0.400) | -0.09 (0.400) |

| HE segment III | 0.68 (0.56-0.79) | 65 | 0.51 | 0.82 | 0.63 | 0.74 | -0.08 (0.003) | -0.05 (0.400) | -0.09 (0.400) |

| HE caudate lobe | 0.70 (0.59-0.81) | 82.5 | 0.60 | 0.76 | 0.60 | 0.76 | -0.11 (0.017) | -0.03 (0.616) | -0.07 (0.400) |

| HE global | 0.71 (0.60-0.82) | 86.3 | 0.70 | 0.71 | 0.59 | 0.81 | -0.11 (0.023) | -0.02 (0.671) | -0.06 (0.400) |

| Marker | AUC (95%CI) | Youden cut-off | Se | Sp | PPV | NPV | Δ HE vs FLIS (q) | Δ HE vs MELD 3.0 (q) | Δ HE vs ALBI (q) |

| FLIS | 0.81 (0.69-0.93) | 4.5 | 0.92 | 0.64 | 0.28 | 0.98 | - | - | - |

| MELD 3.0 | 0.79 (0.64-0.94) | 15.5 | 0.77 | 0.75 | 0.31 | 0.96 | - | - | - |

| ALBI | 0.82 (0.69-0.95) | -1.4 | 0.69 | 0.85 | 0.41 | 0.95 | - | - | - |

| HE segment VI | 0.74 (0.57-0.91) | 75 | 0.85 | 0.74 | 0.32 | 0.97 | -0.07 (0.293) | -0.05 (0.369) | -0.08 (0.220) |

| HE segment VIII | 0.64 (0.46-0.82) | 75 | 0.62 | 0.74 | 0.26 | 0.93 | -0.18 (0.025) | -0.15 (0.082) | -0.18 (0.081) |

| HE segment III | 0.71 (0.56-0.87) | 87.5 | 0.77 | 0.69 | 0.28 | 0.95 | -0.09 (0.188) | -0.08 (0.267) | -0.11 (0.220) |

| HE caudate lobe | 0.71 (0.55-0.87) | 82.5 | 0.77 | 0.69 | 0.27 | 0.95 | -0.09 (0.140) | -0.08 (0.220) | -0.11 (0.170) |

| HE global | 0.71 (0.54-0.88) | 86.3 | 0.85 | 0.62 | 0.25 | 0.96 | -0.17 (0.140) | -0.08 (0.220) | -0.11 (0.170) |

The reference model, which encompasses FLIS, MELD-3.0, etiology, and prior HCC status, demonstrated robust per

At 12 months, the addition of HE did not significantly alter the risk classification or accuracy. With segment VI HE, the categorical NRI was 0.0% (95%CI: -13.6% to 12.9%) and the continuous NRI was 13.6% (95%CI: -58.7% to 31.0%); the AUC was 0.904 for the reference model compared to 0.903 with segment VI HE, and the Brier score was 0.103 for both. Results were similar for global HE. By 24 months, modest improvements in categorical reclassification were observed, primarily affecting non-events. With segment VI HE, the categorical NRI was +2.9%, and the continuous NRI was +9.5%; discrimination and accuracy experienced minimal change. The reclassification matrix indicated that two patients were reclassified downward from > 20% to the 10%-20% range, with no upward reclassifications, consistent with the non-event component. With global HE, the categorical NRI was +7.1%, again attributable entirely to correct downward reclassification among non-events; the continuous NRI was +21.9%, and discrimination and accuracy remained essentially unchanged (AUC increased from 0.843 to 0.846; Brier score changed from 0.1432 to 0.1428).

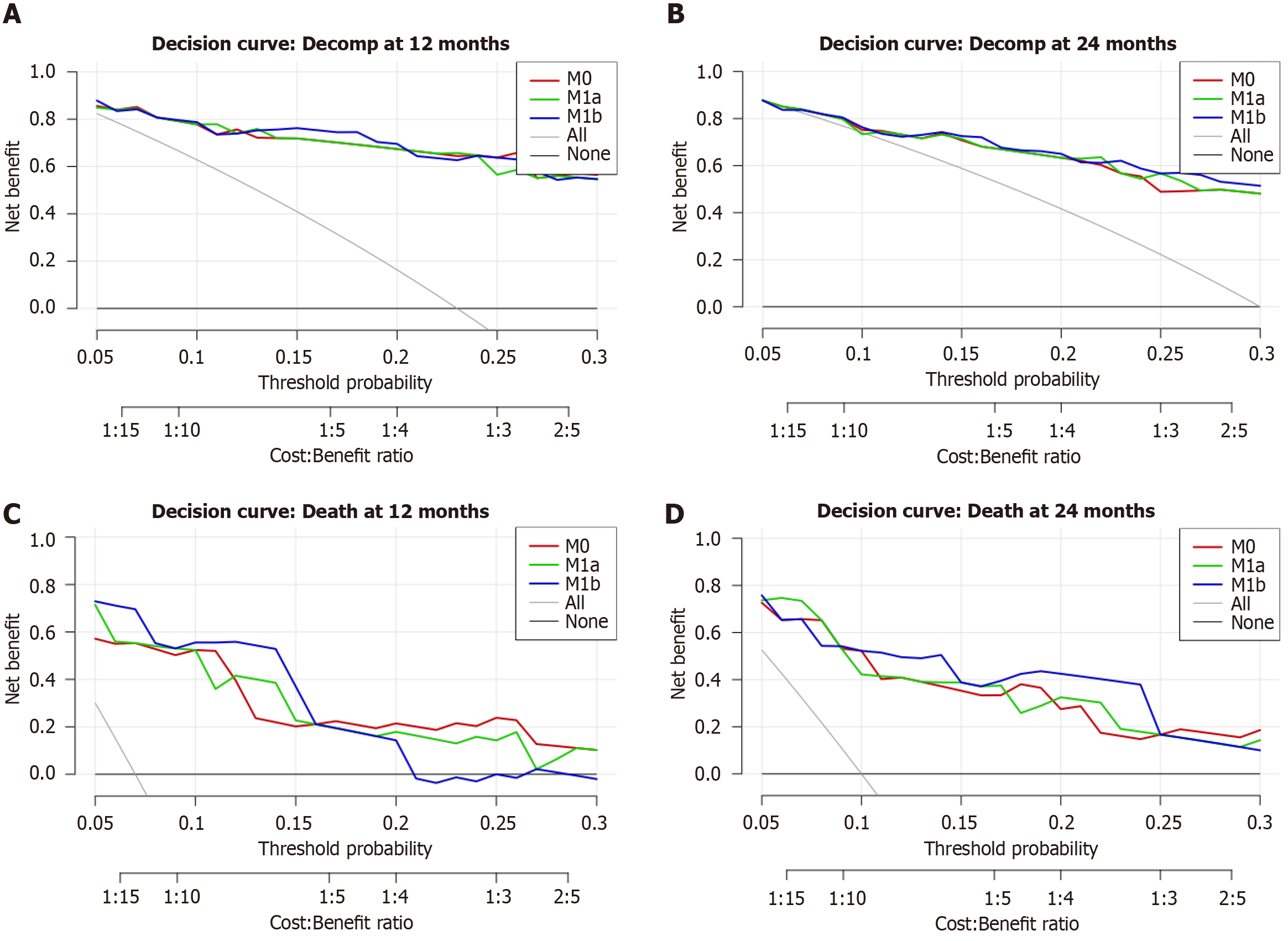

Quantitative decision curve analysis reflected these patterns: At 12 months, differences in net benefit were negligible; at 24 months, the global HE method achieved a small but statistically significant gain at a 20% threshold (ΔNB = 0.010; 95%CI: 0.0025-0.020), which is approximately four fewer unnecessary interventions per 100 patients with equivalent case detection. A borderline small effect was observed at the 10% threshold (ΔNB = 0.0011). Detailed NRI and performance metrics are presented in Table 11, while the quantitative DCA values at prespecified thresholds are summarized in Table 12. Corresponding decision-curve plots are provided in Figure 7A and B.

| Endpoint | Horizon (months) | Added variable to reference model | Categorical NRI (95%CI) | NRI event1 | NRI Non-event1 | Continuous NRI % (95%CI) | ΔAUC2 | ΔBrier2 |

| Decompensation | 12 months | + HE segment VI | 0.0 (-13.6; 12.9) | - | - | -13.6 (-58.7; 31.0) | -0.002 | +0.001 |

| + HE global | 0.0 (-14.6; 14.3) | - | - | +0.34 (-44.3; 45.5) | -0.003 | +0.0008 | ||

| 24 months | + HE segment VI | +2.9 (0.0; 7.6) | 0.0 | +2.9 | +9.5 (-33.1; 51.2) | +0.002 | -0.0006 | |

| + HE global | +7.1 (1.5; 13.9) | 0.0 | +7.1 | +21.9 (-20.6; 62.4) | +0.0029 | -0.00038 | ||

| Mortality | 12 months | + HE segment VI | +30.7 (1.0; 68.8) | +28.6 | +2.2 | +13.7 (-68.0; 94.3) | +0.012 | +0.0001 |

| + HE global | +31.8 (2.0; 69.9) | +28.6 | +3.2 | +24.4 (-58.8; 107.4) | +0.011 | -0.0011 | ||

| 24 months | + HE segment VI | +5.6 (-23.9; 35.6) | 0.0 | +5.6 | +12.2 (-53.4; 76.6) | +0.012 | +0.0005 | |

| + HE global | +6.7 (-24.4; 36.7) | 0.0 | +6.7 | +41.1 (-26.3; 107.9) | +0.006 | -0.0004 |

| Endpoint | Horizon (months) | Added variable to reference model | Threshold | ΔNB (95%CI) | Net reduction per 100 |

| Decompensation | 12 months | + HE global | 0.10 | -0.0020 (-0.0056; 0.001) | -2 |

| 24 months | + HE global | 0.10 | +0.0011 (0.000; 0.0033) | 1 | |

| 24 months | + HE global | 0.20 | +0.0100 (0.0025; 0.020) | 4 | |

| Mortality | 12 months | + HE segment VI | 0.10 | +0.0110 (0.000; 0.032) | 10 |

| 12 months | + HE global | 0.10 | +0.0120 (0.000; 0.033) | 11 | |

| 12 months | + HE global | 0.20 | +0.0225 (0.000; 0.055) | 9 | |

| 24 months | + HE global | 0.10 | +0.0067 (0.0011; 0.0133) | 6 |

Regarding 12-month mortality, both HE measures contributed to an improved risk classification. With segment VI HE, the categorical NRI was +30.7% (95%CI: 1.0%-68.8%), primarily attributable to the upward reclassification of cases (NRI event, 28.6%). The continuous NRI was +13.7% (95%CI: -68.0% to 94.3%). The AUC experienced a slight increase from 0.923 to 0.935, while the Brier score remained virtually constant (0.0521 vs 0.0522). A similar pattern was observed with global HE, showing marginally greater reclassification (categorical NRI, +31.8%; continuous NRI, +24.4%). The AUC increased to 0.934 from 0.923, with the Brier score exhibiting a slight decrease (0.0510 vs 0.0521). At 24 months, the esti

Quantitative DCA supported these findings: At 12 months, global HE increased net benefit at 10% (ΔNB = 0.012; 95%CI: 0.001-0.033; approximately 11 fewer interventions per 100) and at 20% (ΔNB = 0.0225; 95%CI: 0.001-0.055; approximately 9 fewer interventions per 100). Similar results were observed for segment VI HE at the 10% threshold (ΔNB = 0.011; 95%CI: 0.000-0.032). At 24 months, global HE demonstrated a statistically significant improvement at the 10% threshold (ΔNB = 0.0067; 95%CI: 0.0011-0.0133; approximately 6 fewer interventions per 100), with marginal and non-statistically significant differences at 20%. Complete numerical results are presented in Tables 11 and 12, and relevant decision-curve plots are depicted in Figure 7C and D.

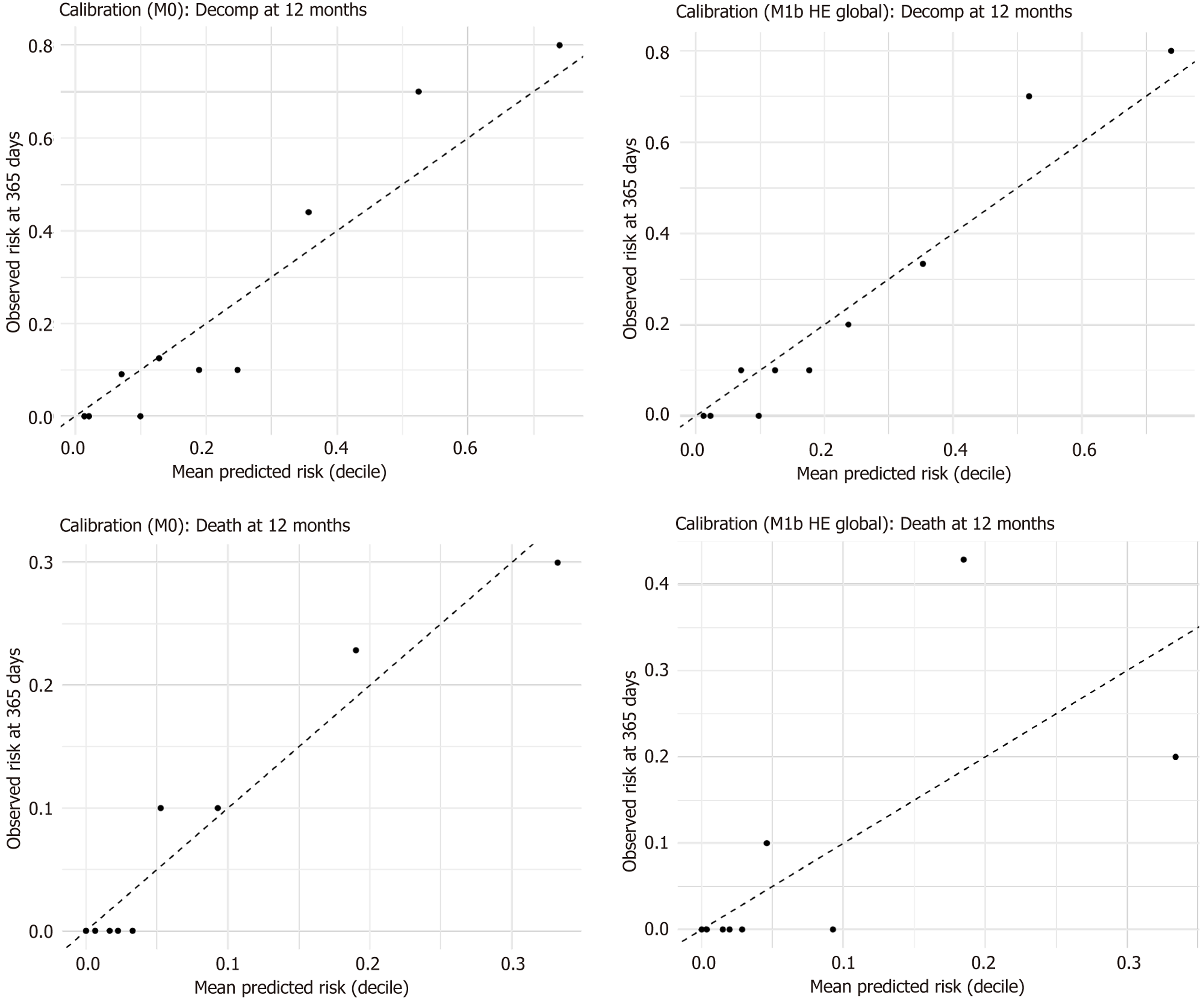

At the 12-month horizon, the visual calibration for both the reference and extended models was considered acceptable: The observed risks across deciles closely aligned with the mean predicted risks, with no significant miscalibration resulting from the inclusion of HE (Figure 8). The patterns observed at 24 months were analogous. Minor deviations at the highest deciles were minimal and consistent with the previously noted non-event reclassification.

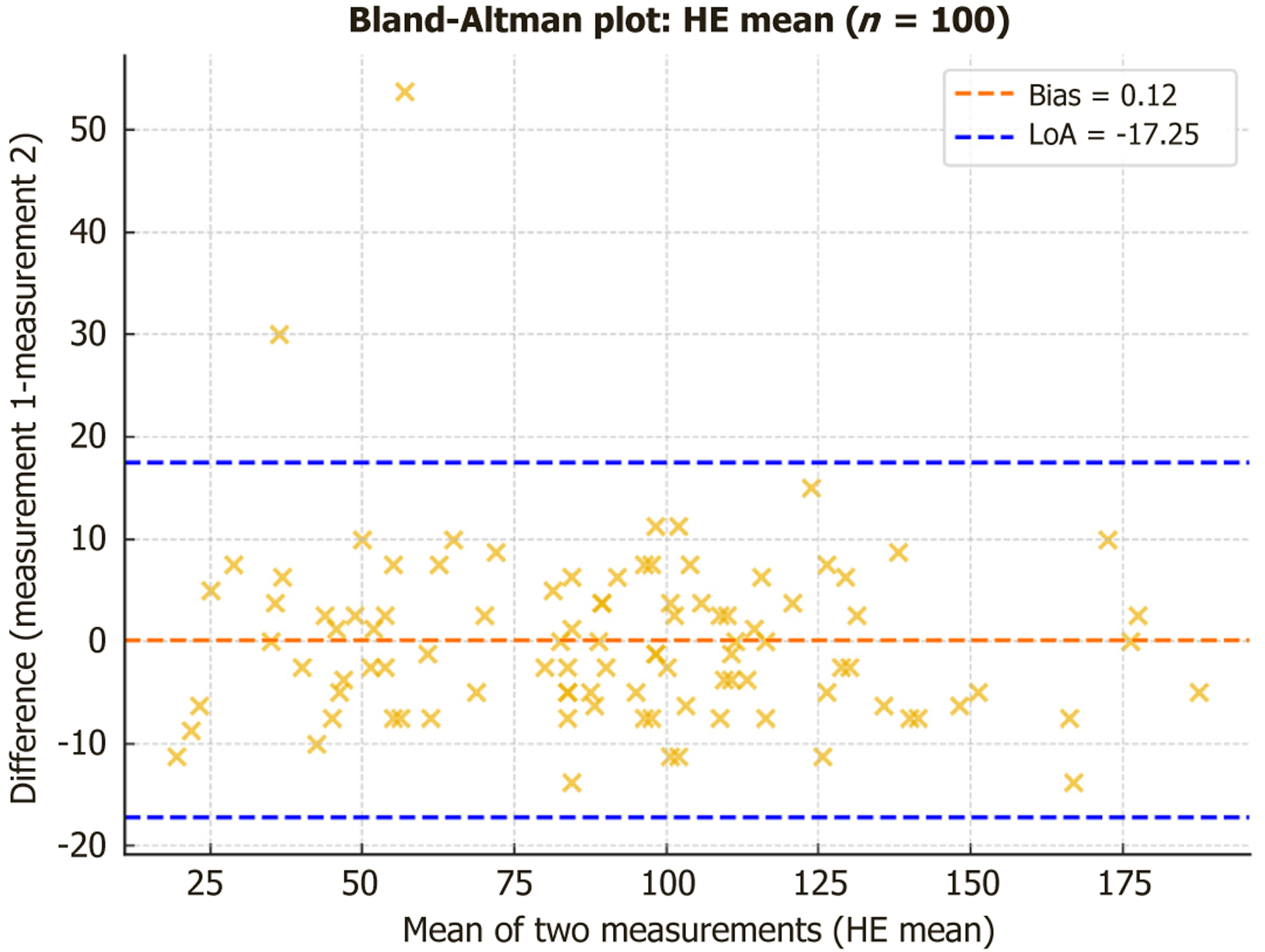

Intraobserver reproducibility was good to excellent across all parameters (Table 13). Native SI showed ICCs of 0.87-0.96 with CVs of 2%-5%, while hepatobiliary SI demonstrated excellent reproducibility (ICC: 0.99-0.995, CV: 2%-3%). HE measurements also achieved excellent ICCs (0.94-0.97), although with higher variability (CV: 9%-15%). Bland-Altman analysis confirmed minimal systematic bias across parameters; for example, mean HE showed a negligible bias (0.12) with 95% limits of agreement from -17.3 to 17.5 (Figure 9).

| Parameter | ICC | CV% | Bias | LoA (95%) |

| Native SI | ||||

| Segment VI | 0.927 | 3.2 | -1.05 | -18.57 to 16.47 |

| Segment VIII | 0.874 | 3.8 | -3.50 | -23.27 to 16.27 |

| Caudate lobe | 0.961 | 2.6 | 0.00 | -12.61 to 12.61 |

| Segment III | 0.928 | 4.6 | -0.35 | -20.06 to 19.36 |

| Global SI | 0.955 | 2.3 | -1.23 | -13.77 to 11.32 |

| Hepatobiliary SI | ||||

| Segment VI | 0.990 | 2.4 | -0.20 | -16.62 to 16.22 |

| Segment VIII | 0.990 | 2.2 | -2.90 | -16.84 to 11.04 |

| Caudate lobe | 0.993 | 1.8 | 0.20 | -13.15 to 13.55 |

| Segment III | 0.988 | 3.2 | -1.50 | -18.19 to 15.19 |

| Global SI | 0.995 | 1.8 | -1.10 | -11.33 to 9.13 |

| HE | ||||

| Segment VI | 0.955 | 14.9 | 0.85 | -25.02 to 26.72 |

| Segment VIII | 0.941 | 12.1 | 0.60 | -24.98 to 26.18 |

| Caudate lobe | 0.974 | 9.4 | 0.20 | -18.22 to 18.62 |

| Segment III | 0.943 | 14.8 | -1.15 | -26.02 to 23.72 |

| Global HE | 0.974 | 9.3 | 0.12 | -17.25 to 17.50 |

Chronic liver disease is a progressive condition characterized by the gradual loss of functional liver tissue, which is replaced by fibrotic tissue, leading to architectural distortion and increased portal pressure. The transition from com

In this study, we showed that hepatobiliary-phase HE on gadoxetate-enhanced MRI offers clinically relevant pro

Accurate and early assessment of liver function is essential for predicting the risk of decompensation, guiding treatment choices, and selecting suitable candidates for liver transplantation or hepatic resection. In this context, gadoxetate-enhanced MRI has become a valuable imaging tool that can assess both liver structure and hepatocellular function through well-defined physiological mechanisms[30-32]. Hepatocellular uptake of gadoxetate is mediated by OATP1B1/1B3 transporters, while biliary excretion depends on the MRP2 transporter[33]. Any dysfunction in these processes - whether due to the loss of hepatocytes or downregulation of transporters - leads to impaired uptake and re

The FLIS, introduced by Bastati et al[12], is a semi-quantitative MRI-based tool used to evaluate hepatic functional reserve and prognosis in patients with ACLD. Low FLIS scores (ranging from 0 to 3) indicate severe hepatocellular dysfunction and are associated with a higher risk of decompensation and death[12,16,25,35,36]. In our study, global HE and segment VI HE showed the strongest correlations with the FLIS score (r = 0.797 and r = 0.819, respectively), indicating that greater enhancement is associated with better liver function. ANOVA confirmed significant differences across FLIS groups, and post hoc analysis demonstrated that HE could distinguish between extreme FLIS categories. These findings link MRI-derived quantitative parameters with visually assessed, validated scores, accurately reflecting the extent of liver functional impairment. To our knowledge, few studies have examined the direct relationship between quantitative HE and the FLIS score. Eryuruk et al[37] demonstrated that relative enhancement indices were strongly correlated with ALBI grade and outperformed FLIS in this regard. These results indicate that quantitative parameters may improve the accuracy of liver function assessment. Unlike the FLIS score, quantitative measures such as HE offer an objective, reproducible, and sensitive method for estimating liver function. ROI-based measurements enable precise quantification of hepatocellular uptake, reducing subjectivity. This feature is essential in clinical practice, where treatment decisions require standardized and comparable long-term parameters. Therefore, HE may be superior to FLIS for early detection of liver dysfunction and monitoring disease progression, especially when subtle changes have significant prognostic implications.

A key element in the evolving biomarker landscape is the distinction between functional and structural measures. Elastography techniques, including VCTE and MRE, mainly assess hepatic stiffness as an indicator of fibrosis and structural remodeling. MRE is considered the most accurate non-invasive method for staging fibrosis, with superior diagnostic performance compared to transient elastography, especially in advanced fibrosis[18]. However, its clinical use remains limited due to high costs, technical complexity, and limited availability, making it more suitable for tertiary centers and research settings. In contrast, gadoxetate-derived HE reflects hepatocellular functional reserve rather than structural stiffness. In our cohort, HE strongly correlated with clinical indices of hepatic reserve (MELD 3.0, Child-Pugh, ALBI), particularly with FLIS, highlighting its role as a functional biomarker. These clinical scores assess liver dysfunction based on synthetic and excretory functions, relying on laboratory parameters such as bilirubin, albumin, INR, and creatinine[6,7,8,11,20]. By contrast, gadoxetate uptake directly reflects the viability and function of hepatocytes, depending on the expression and activity of OATP1B1/B3 and MRP2 transporters[34,35]. Therefore, reduced HE indicates not only the loss of viable hepatocytes but also impaired biliary excretion, providing an integrated imaging perspective on hepatic function. This finding aligns with those of Öcal et al[38] and Van Beers et al[39], who observed that hepatobiliary-phase enhancement parameters correlated with objective liver function indicators, such as albumin, bilirubin, sodium, and platelets, as well as clinical grading systems across multiple centers and vendors. This functional sensitivity may explain why HE appears to offer better prognostic performance in compensated ACLD, a stage where functional decline often precedes overt structural changes. Overall, MRE and HE highlight complementary aspects of disease assessment - structural vs functional - that could ultimately be incorporated into comprehensive risk stratification frameworks.

HE showed a significant negative correlation with liver stiffness measured by elastography. The strongest correlation was observed in segment VIII (r = -0.503), indicating that this imaging parameter is sensitive to structural changes in the liver and may reflect the severity of fibrosis. These results align with the findings of Öcal et al[38], which showed that hepatobiliary-phase uptake parameters gradually decrease as hepatic fibrosis progresses, further supporting the con

In addition to liver stiffness, HE values also demonstrated a weak but significant negative correlation with the HVPG in segments I, VI, and VIII. This supports the notion that gadoxetate uptake depends not only on hepatocellular function and density but also on intrahepatic vascular resistance and perfusion dynamics. Consistent with findings from Van Beers et al[39] and Semmler et al[40], our results suggest that HE could serve as a non-invasive imaging biomarker for assessing the severity of portal hypertension. Therefore, HE reflects both structural and functional changes in the liver, capturing the effects of fibrosis, microvascular impairment, and hepatocellular dysfunction. This makes HE a valuable tool for the comprehensive evaluation of ACLD.

Conversely, hepatobiliary-phase SI as a raw parameter did not show a significant correlation with HVPG. This may be due to its susceptibility to various confounding factors, such as steatosis, iron overload, or other variations in liver composition that occur when the signal is not normalized against the baseline (native) liver signal. In contrast, HE reflects the relative signal increase, making it more sensitive to physiological and pathological changes in hepatocellular function, microvascular integrity, and biliary transporter activity.

A key observation in this study is that segment VI exhibited the strongest correlations with functional and clinical scores and remained independently predictive of decompensation in a multivariate Cox analysis. This finding suggests that segment VI may function as a particularly sensitive region for assessing hepatobiliary-phase uptake. In contrast, segment VIII showed weaker associations, possibly due to greater susceptibility to motion artifacts or technical variability in ROI placement near the diaphragm. These results emphasize the importance of segmental analysis, suggesting that not all liver regions contribute equally to prognostic evaluation, and that measurements in the right lobe - especially in segment VI - may be optimal for functional risk stratification.

While most associations lost significance after adjustment for MELD 3.0, the persistence of segment VI HE as an independent predictor of decompensation suggests that functional imaging may provide additional prognostic information beyond conventional biochemical and structural scores. This interpretation is supported by our reclassification and decision-curve analyses, which demonstrated that HE improved risk stratification for short-term mortality, primarily by correctly reclassifying high-risk patients upward and reducing unnecessary interventions. NRI and DCA showed a limited impact on decompensation but a measurable benefit on mortality at 12 months. Adding global HE to a reference model (FLIS, MELD 3.0, etiology, HCC) yielded a categorical NRI of 31.8% and a ΔNB equivalent to 9-11 fewer unnecessary interventions per 100 patients at standard decision thresholds. Importantly, calibration analyses showed that adding HE did not compromise model fit. These findings indicate that HE, although not replacing established clinical scores, may improve prognostic assessment and strengthen individualized risk stratification when combined with them.

In discriminative analyses, FLIS and ALBI demonstrated the highest accuracy for predicting decompensation and mortality, respectively. However, segment VI HE was consistently the most effective among HE measures, with an AUC of 0.74 for both outcomes. Notably, a cutoff of 75 for segment VI reliably stratified risk across endpoints, achieving a specificity of up to 0.86 and negative predictive values as high as 0.97. This suggests that while FLIS and ALBI are slightly more accurate, HE - particularly in segment VI - offers dual clinical utility: It serves as a non-invasive marker for identifying patients who need intensive monitoring and also as a criterion to exclude disease, thereby lowering mortality risk. The small ΔAUC differences compared to MELD 3.0 and ALBI indicate that HE approaches the performance of established models. These results support the prognostic value of HE, aligning with previous findings from Heo et al[14], which showed that MRI indices based on deep learning can predict hepatic decompensation and liver-related death.

The clinical significance of HE as an imaging biomarker is further supported by recent advances in artificial in

The clinical implications of our findings are significant and align with current trends in medical practice. A threshold of HE < 75 U in segment VI identified patients at higher risk of mortality, overlapping with those considered for intensified treatment under the Baveno VII consensus on clinically significant portal hypertension[17]. In this context, HE could serve as a non-invasive gatekeeper for invasive procedures, such as HVPG measurement, or for initiating preemptive, non-selective beta-blocker therapy[17]. Although these models have not yet been prospectively integrated into clinical care pathways, incorporating functional imaging into risk-based surveillance could, in theory, reduce deco

Integrating segmental HE into AI-assisted platforms could automate risk stratification, decrease observer reliance, and enable personalized surveillance strategies. Preliminary cost-effectiveness analysis in cirrhotic patients at risk for HCC shows that AI-enhanced MRI surveillance has an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of about €9900 per quality-adjusted life-year gained, which is well below typical willingness-to-pay thresholds[42]. These findings support the potential economic and clinical benefits of including functional imaging biomarkers like HE in risk-based care pathways.

Quantitative measurements of hepatic uptake, especially segment VI HE and global HE, are emerging as promising imaging biomarkers that may supplement and, in certain cases, surpass traditional prognostic scores. While MELD, ALBI, and Child-Pugh scores remain essential in clinical decision-making, they can lack sensitivity to subtle functional declines. HE offers a sensitive, consistent, and spatially detailed estimate of hepatocellular function, improving functional imaging assessments.

Furthermore, HE is not only valuable for estimating hepatic reserve but also for assessing intrahepatic hemodynamics, illustrating broad applicability in the planning of invasive treatments. This is particularly significant when selecting candidates for liver transplantation or surgical resection, where balancing residual function and surgical risk is of utmost importance. In patients with ambiguous laboratory results, a low HE may indicate an increased perioperative risk, necessitating reevaluation of treatment options or closer monitoring. Moreover, integrating HE into personalized clinical algorithms could facilitate the early identification of patients at risk of decompensation, in line with current EASL guidelines that recommend using combined non-invasive methods for risk assessment in ACLD[18].

This study contributes to the growing evidence that gadoxetate-enhanced MRI offers valuable functional biomarkers in ACLD. Key strengths include the integration of multiple analytical methods - correlation analyses, univariate and multivariate Cox regression, ROC curves, and reclassification metrics - which provide a comprehensive assessment of HE. The use of NRI and DCA, demonstrating that HE improves short-term mortality prediction and reduces unnecessary interventions, is novel in this field and directly enhances clinical relevance. Another strength is the segmental analysis, which shows that segment VI has specific prognostic importance, supporting the idea that regional assessment can give additional insights beyond overall measures. Finally, intra-reader reproducibility was excellent, confirmed by both ICC and Bland-Altman analyses, confirming the reliability of HE measurement despite manual ROI placement.

Sensitivity analyses further underscored the potential influence of etiology and prior HCC history on gadoxetate uptake. Excluding patients with previous HCC, confirmed HE was a reliable predictor of decompensation, mortality, and liver stiffness, but stratified analyses by etiology showed more variability. In alcoholic cirrhosis, HE maintained a strong association with decompensation, consistent with previous data indicating impaired transporter function and biliary excretion in alcohol-related disease[35]. Conversely, in viral cirrhosis, these associations diminished and were no longer significant after adjusting for multiple testing, likely due to fewer outcome events. Similarly, the correlation between HE and HVPG was strong across the overall cohort but weakened in stratified analyses, possibly because of limited sample size rather than an actual lack of association. These findings highlight the need for larger, etiology-specific studies to determine whether HE's prognostic value differs across various underlying liver diseases.

Our study had several important limitations that should be recognized. First, the retrospective, single-center design may have introduced selection bias and thus restricts the generalizability of our findings. Although the study group was well-characterized and clinically balanced, external validation in a larger, more diverse population is needed to confirm the identified thresholds and improve their clinical usefulness. Second, imaging measurements were done manually, which can be prone to errors and observer variability; however, this was mitigated by demonstrating excellent intra-reader agreement. Using automated segmentation and quantification methods could greatly enhance accuracy and reproducibility. Third, heterogeneity in liver disease causes and including patients with prior HCC, may affect gadoxetate uptake, although sensitivity analyses showed consistent results across subgroups. Fourth, while segment VI remained an independent predictor of mortality after adjusting for MELD 3.0, most other associations were weakened in multivariate analysis, emphasizing the significant prognostic value of the MELD-based model. Another limitation is the absence of standardized HE quantification protocols across different MR vendors, which impacts measurement consistency and currently limits wider clinical application of this method. As recent European Society of Urogenital Radiology/European Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine and Biology[43] guidelines highlight, differences in spatial resolution and signal-to-noise ratio among various hardware and software platforms can influence the reproducibility of quantitative enhancement measurements. Phantom calibration and vendor-neutral normalization have been proposed as solutions, but we were unable to implement these in our retrospective, single-center study. Additionally, in our study, hepatobiliary phase images were only acquired at 20 minutes, as later acquisitions (≥ 30 minutes), which remain debated regarding their added value in advanced liver disease, were not included in our protocol. Future prospective studies that incorporate these standardization techniques will be essential to establish clinically relevant HE thresholds. Moreover, our analysis focused on mean segmental and global values, which simplifies comparison but does not account for possible intrahepatic functional differences. This could be clinically important, especially in cases of focal disease or post-treatment assessments.

Unmeasured confounders, such as nutritional status, concurrent therapies, or systemic comorbidities, could influence both gadoxetate uptake and clinical progression. The relatively small sample size of the subgroups analyzed for deco

Our findings demonstrate that HE on gadoxetate-enhanced MRI, particularly in segment VI, serves as a consistent and clinically significant biomarker of liver function in ACLD. HE correlates with established prognostic scores and liver stiffness, predicts adverse outcomes, and improves short-term mortality risk assessment in reclassification and decision-curve analyses. These results position HE as a complementary biomarker to structural imaging tools, such as elas

| 1. | Gan C, Yuan Y, Shen H, Gao J, Kong X, Che Z, Guo Y, Wang H, Dong E, Xiao J. Liver diseases: epidemiology, causes, trends and predictions. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2025;10:33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 90.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Rinella ME, Lazarus JV, Ratziu V, Francque SM, Sanyal AJ, Kanwal F, Romero D, Abdelmalek MF, Anstee QM, Arab JP, Arrese M, Bataller R, Beuers U, Boursier J, Bugianesi E, Byrne CD, Castro Narro GE, Chowdhury A, Cortez-Pinto H, Cryer DR, Cusi K, El-Kassas M, Klein S, Eskridge W, Fan J, Gawrieh S, Guy CD, Harrison SA, Kim SU, Koot BG, Korenjak M, Kowdley KV, Lacaille F, Loomba R, Mitchell-Thain R, Morgan TR, Powell EE, Roden M, Romero-Gómez M, Silva M, Singh SP, Sookoian SC, Spearman CW, Tiniakos D, Valenti L, Vos MB, Wong VW, Xanthakos S, Yilmaz Y, Younossi Z, Hobbs A, Villota-Rivas M, Newsome PN; NAFLD Nomenclature consensus group. A multisociety Delphi consensus statement on new fatty liver disease nomenclature. J Hepatol. 2023;79:1542-1556. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1676] [Cited by in RCA: 1824] [Article Influence: 608.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 3. | Giangregorio F, Mosconi E, Debellis MG, Provini S, Esposito C, Garolfi M, Oraka S, Kaloudi O, Mustafazade G, Marín-Baselga R, Tung-Chen Y. A Systematic Review of Metabolic Syndrome: Key Correlated Pathologies and Non-Invasive Diagnostic Approaches. J Clin Med. 2024;13:5880. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | D'Amico G, Garcia-Tsao G, Pagliaro L. Natural history and prognostic indicators of survival in cirrhosis: a systematic review of 118 studies. J Hepatol. 2006;44:217-231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1892] [Cited by in RCA: 2216] [Article Influence: 110.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 5. | Sohn W. Essential tools for assessing advanced fibrosis in metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease: Editorial on "Optimal cut-offs of vibration-controlled transient elastography and magnetic resonance elastography in diagnosing advanced liver fibrosis in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Clin Mol Hepatol. 2025;31:277-280. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Sharma P. Value of Liver Function Tests in Cirrhosis. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2022;12:948-964. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kotak PS, Kumar J, Kumar S, Varma A, Acharya S. Navigating Cirrhosis: A Comprehensive Review of Liver Scoring Systems for Diagnosis and Prognosis. Cureus. 2024;16:e57162. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kim WR, Mannalithara A, Heimbach JK, Kamath PS, Asrani SK, Biggins SW, Wood NL, Gentry SE, Kwong AJ. MELD 3.0: The Model for End-Stage Liver Disease Updated for the Modern Era. Gastroenterology. 2021;161:1887-1895.e4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 244] [Cited by in RCA: 442] [Article Influence: 88.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | O'leary JG, Bajaj JS. MELD 3.0: One Small Step for Womankind or One Big Step for Everyone? Gastroenterology. 2022;162:1780-1781. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Gülcicegi DE, Goeser T, Kasper P. Prognostic assessment of liver cirrhosis and its complications: current concepts and future perspectives. Front Med (Lausanne). 2023;10:1268102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kamath PS, Wiesner RH, Malinchoc M, Kremers W, Therneau TM, Kosberg CL, D'Amico G, Dickson ER, Kim WR. A model to predict survival in patients with end-stage liver disease. Hepatology. 2001;33:464-470. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3462] [Cited by in RCA: 3784] [Article Influence: 151.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 12. | Bastati N, Wibmer A, Tamandl D, Einspieler H, Hodge JC, Poetter-Lang S, Rockenschaub S, Berlakovich GA, Trauner M, Herold C, Ba-Ssalamah A. Assessment of Orthotopic Liver Transplant Graft Survival on Gadoxetic Acid-Enhanced Magnetic Resonance Imaging Using Qualitative and Quantitative Parameters. Invest Radiol. 2016;51:728-734. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Verde F, Romeo V, Maurea S. Advanced liver imaging using MR to predict outcomes in chronic liver disease: a shift from morphology to function liver assessment. Quant Imaging Med Surg. 2020;10:805-807. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Heo S, Lee SS, Kim SY, Lim YS, Park HJ, Yoon JS, Suk HI, Sung YS, Park B, Lee JS. Prediction of Decompensation and Death in Advanced Chronic Liver Disease Using Deep Learning Analysis of Gadoxetic Acid-Enhanced MRI. Korean J Radiol. 2022;23:1269-1280. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Jang HJ, Min JH, Lee JE, Shin KS, Kim KH, Choi SY. Assessment of liver fibrosis with gadoxetic acid-enhanced MRI: comparisons with transient elastography, ElastPQ, and serologic fibrosis markers. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2019;44:2769-2780. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Bastati N, Beer L, Mandorfer M, Poetter-Lang S, Tamandl D, Bican Y, Elmer MC, Einspieler H, Semmler G, Simbrunner B, Weber M, Hodge JC, Vernuccio F, Sirlin C, Reiberger T, Ba-Ssalamah A. Does the Functional Liver Imaging Score Derived from Gadoxetic Acid-enhanced MRI Predict Outcomes in Chronic Liver Disease? Radiology. 2020;294:98-107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | de Franchis R, Bosch J, Garcia-Tsao G, Reiberger T, Ripoll C; Baveno VII Faculty. Baveno VII - Renewing consensus in portal hypertension. J Hepatol. 2022;76:959-974. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1537] [Cited by in RCA: 1865] [Article Influence: 466.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 18. | European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines on non-invasive tests for evaluation of liver disease severity and prognosis - 2021 update. J Hepatol. 2021;75:659-689. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 993] [Cited by in RCA: 1305] [Article Influence: 261.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |