Published online Dec 27, 2025. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v17.i12.111414

Revised: August 11, 2025

Accepted: November 21, 2025

Published online: December 27, 2025

Processing time: 180 Days and 19.5 Hours

The global incidence of hyperlipidemia has been increasing on an annual basis, concomitant with improvements in living standards and dietary changes. Hy

We present a special case of refractory hyperlipidemia associated with cholestatic liver disease in a 49-year-old woman.

In the treatment of clinical cases of drug-induced cholestatic liver disease and hyperlipidemia, it is essential for medical professionals to consider the patient’s overall condition, formulate an individualized treatment plan, and closely mo

Core Tip: Hyperlipidemia is closely associated with the development of multiple diseases and is widely recognized as a major risk factor for cardiovascular disease. In clinical settings, drug-induced cholestatic liver disease can increase blood cholesterol and triglyceride levels, a condition known as secondary hyperlipidemia. Furthermore, lipid overload can ex

- Citation: Xu MJ, Wei X, Lu Y, Sun L, Xie Y, Li MH. Severe hyperlipidemia associated with drug-induced cholestatic liver disease: A case report. World J Hepatol 2025; 17(12): 111414

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v17/i12/111414.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v17.i12.111414

Hyperlipidemia, characterized by elevated levels of lipids in the blood, is a significant risk factor for cardiovascular diseases, impacting heart function and circulation. One of the mechanisms by which hyperlipidemia exerts its deleterious effects is the release of circulating microparticles (MPs) during dyslipidemia. These MPs have been shown to modulate endothelial cell function, contributing to vascular inflammation and damage. In a study involving dyslipidemic Psammomys obesus, it was observed that MPs isolated from animals on a high-energy diet led to a significant decrease in endothelial nitric oxide synthase expression and an increase in reactive oxygen species production. This suggests that MPs play a dual role in vascular function by acting as vectors of bioactive information that contribute to endothelial dys

Furthermore, hyperlipidemia is closely linked to the formation of blood clots, a process that can lead to thrombosis and other cardiovascular complications. Hyperhomocysteinemia (HHcy), a condition often associated with elevated lipid levels, has been shown to affect platelet-driven contraction of blood clots. In vitro studies and rat models of HHcy demonstrated that homocysteine enhances clot contraction at moderate levels but suppresses it at higher concentrations. This is likely due to homocysteine-induced platelet activation followed by exhaustion, which can lead to larger and more obstructive clots. The study highlights the complex role of HHcy in modulating clot contraction, which may serve as an underappreciated mechanism in thrombosis[2].

In addition to the direct effects of lipids on blood vessels and clot formation, hyperlipidemia also influences blood viscosity, which is a critical factor in circulatory health. Alterations in blood rheology, such as increased viscosity, can enhance the risk of thrombosis by affecting the flow properties of blood and the shear forces acting on endothelial cells. This relationship is further complicated by drug-induced conditions that exacerbate hyperviscosity and thrombotic risk, such as the use of oral contraceptives and chemotherapy. These findings underscore the importance of understanding the rheological properties of blood in the context of hyperlipidemia and its associated cardiovascular risks[3].

Excessive fat intake and abnormalities in the synthesis and metabolism of lipoproteins can lead to dyslipidemia, which can be classified into primary and secondary according to the cause of the disease. Dyslipidemia caused by other diseases and known causes is known as secondary hyperlipidemia. Common diseases and medications that can cause this condition include hypothyroidism, cholestatic liver disease, chronic kidney disease, atypical antipsychotic drugs, corticosteroids, cyclosporine, and others. Drug-induced cholestasis is a specific type of liver injury that is usually caused by the direct toxic effects or allergic reactions of drugs or their metabolites on hepatocytes. This condition can result in obstruction of bile flow, leading to bile stasis, which can develop into intrahepatic cholestasis in severe cases. Hepatic lipid metabolism is regulated by the uptake and export of fatty acids, de novo lipogenesis, and the utilization of fat by β-oxidation. Altering the balance between these pathways leads to hepatic lipid accumulation, which can progress to worsen liver disease through long-term activation of inflammatory and fibrotic pathways. The relationship between cholestatic liver disease and hyperlipidemia is complex and may involve multiple mechanisms. For these reasons, understanding the molecular mechanisms underlying hyperlipidemia’s affects is crucial for developing effective therapeutic strategies to manage hyperlipidemia-related diseases, in order to mitigate and prevent the risk of the diseases.

Progressive yellowing of the skin and sclera for 1 week, accompanied by yellowish urine, lighter stool, skin itching, and fatigue.

A 49-year-old woman presented to a local hospital on November 25, 2023 with the above symptoms. Initial lab tests showed elevated hepatobiliary enzymes [alanine aminotransferase (ALT) 378 U/L, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) 396 U/L, total bilirubin (TBIL) 229.8 μmol/L, direct bilirubin (DBIL) 206.8 μmol/L, gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) 591 U/L, and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) 649 U/L)] and hypercholesterolemia (total cholesterol 14.35 mmol/L). Auto

Repeated use of traditional Chinese medicinal remedies in the year prior to onset; no other remarkable medical history.

The patient denied any family history of genetic diseases.

General appearance: The patient appeared fatigued but conscious and cooperative. No acute distress was observed.

Skin and mucous membranes: Marked jaundice was noted in the skin and sclera. Skin itching was reported, with no visible scratch marks or rashes. Palmar erythema and spider angiomas were absent.

Abdomen: The abdomen was soft and non-tender on palpation. Mild tenderness was present in the right upper quadrant. No hepatosplenomegaly or abdominal masses were palpable. Bowel sounds were normal. No ascites was detected by shifting dullness or fluid wave.

Other systems: No lymphadenopathy was found. Cardiopulmonary auscultation revealed no abnormalities. Neur

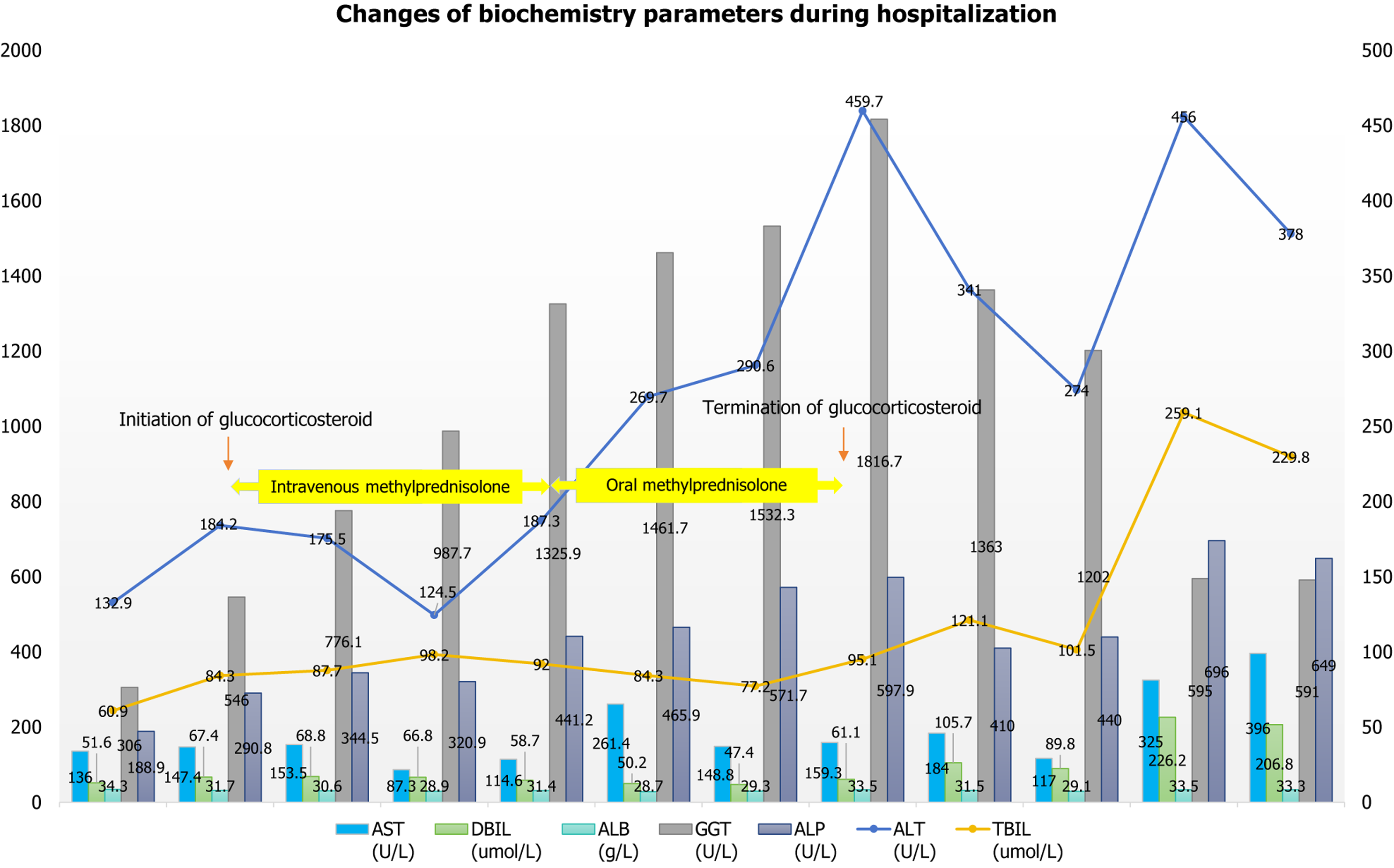

Liver function: The patient had elevated ALT (378 U/L → 456 U/L → 132.9U/L), AST (396 U/L → 325 U/L → 136.0 U/L), TBIL (229.8 μmol/L → 259.1 μmol/L → 60.9 μmol/L→ 84.3 μmol/L), DBIL (206.8 μmol/L → 226.2 μmol/L → 51.6 μmol/L), GGT (591 U/L → 595 U/L → 306 U/L → 197.2 U/L), and ALP (649 U/L → 696 U/L → 188.9 U/L → 192.9 U/L), as well as decreased albumin (33.3 g/L → 33.5 g/L → 34.3 g/L). She had a normal prothrombin time activity (84%). Changes in these indicators are detailed in Figure 1.

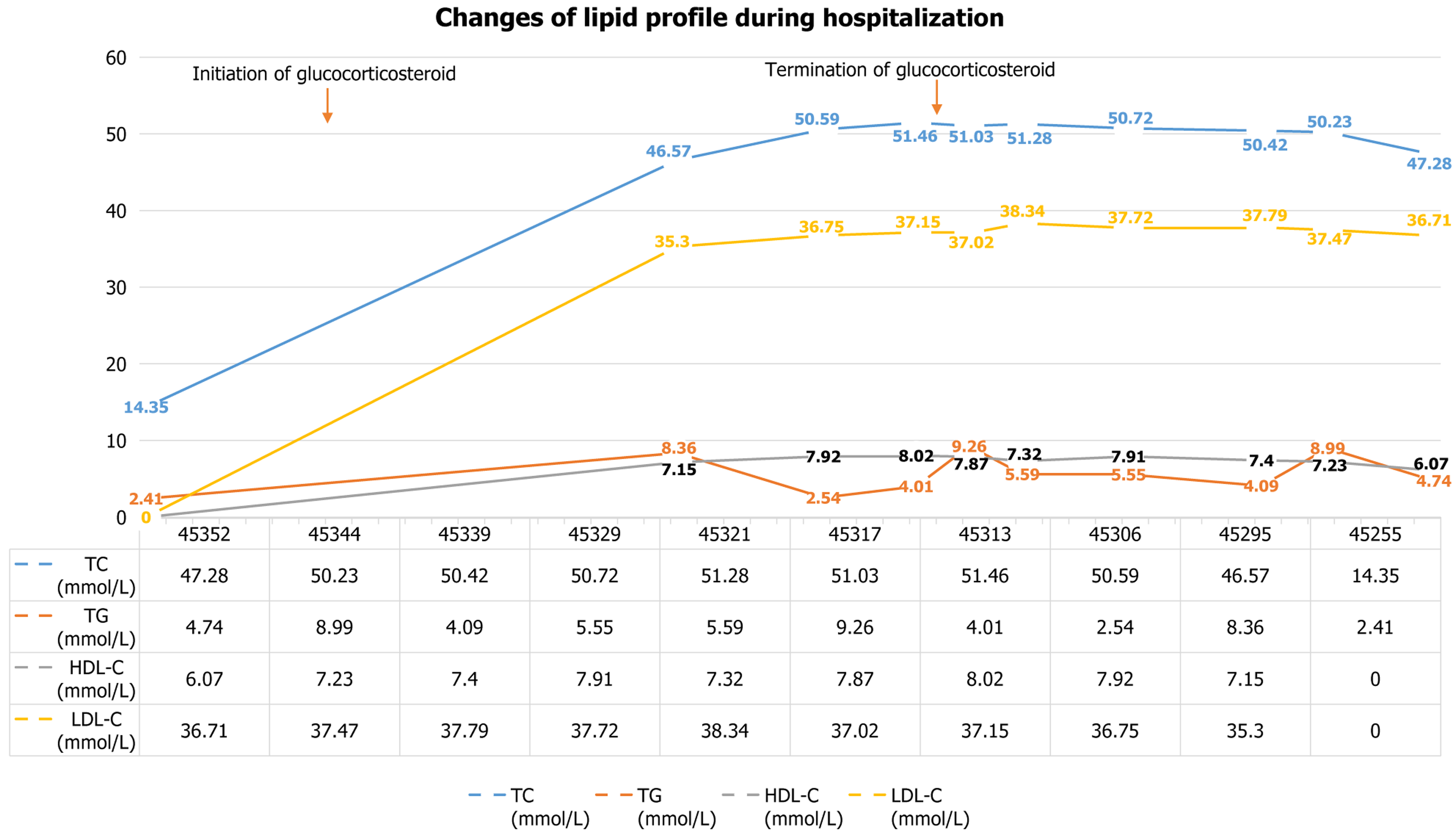

Lipids: The patient’s lipid levels include: Total cholesterol 14.35 mmol/L → 50.59 mmol/L → 6.28 mmol/L → 6.47 mmol/L, triglycerides 2.41 mmol/L→ 2.54 mmol/L → normal, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol 7.92 mmol/L, and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) 36.75 mmol/L (refractory to lipid-lowering drugs). Changes in these indicators are detailed in Table 1 and Figure 2.

| March 1, 2024 | February 22, 2024 | February 17, 2024 | February 2, 2024 | January 30, 2024 | January 26, 2024 | January 22, 2024 | January 15, 2024 | January 4, 2024 | November 25, 2023 | |

| TC (mmol/L) | 47.28 | 50.23 | 50.42 | 50.72 | 51.28 | 51.03 | 51.46 | 50.59 | 46.57 | 14.35 |

| TG (mmol/L) | 4.74 | 8.99 | 4.09 | 5.55 | 5.59 | 9.26 | 4.01 | 2.54 | 8.36 | 2.41 |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | 6.07 | 7.23 | 7.4 | 7.91 | 7.32 | 7.87 | 8.02 | 7.92 | 7.15 | - |

| LDL-C (mmol/L) | 36.71 | 37.47 | 37.79 | 37.72 | 38.34 | 37.02 | 37.15 | 36.75 | 35.3 | - |

Autoimmune/viral tests: The patient had an antinuclear antibody titer of 1:100; normal immunoglobulin G, immunoglobulin M, and immunoglobulin G4; and negative antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, hepatitis A-E, treponema pallidum, and human immunodeficiency virus.

Others: The patient had normal tumor markers, blood glucose, ammonia, and electrolytes. Genetic testing excluded familial hypercholesterolemia/urea cycle disorders.

MRCP and abdominal contrast-enhanced computed tomography: Localized stenosis of the common hepatic duct, mild low-level biliary obstruction, slightly thickened common bile duct walls, suspicious nodules in the duodenal area, cholecystitis, and diffuse liver lesions were observed. There was no signs of cirrhosis (local hospital, November 2023).

Abdominal ultrasound: There were no abnormal changes after methylprednisolone treatment (local hospital, December 25, 2023).

MRCP and abdominal contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging: There was no evidence of cirrhosis, biliary dilatation/obstruction, or definite malignant lesions (our hospital, January 2024).

Drug-induced cholestatic hepatitis.

Initial management: The patient was administered with liver-protecting medications (glycyrrhizic acid, UDCA, and S-adenosylmethionine), but her liver function deteriorated (local hospital, November 25, 2023 to December 6, 2023).

Anti-inflammatory therapy: The patient was diagnosed with drug-cholestatic hepatitis via Roussel Uclaf Causality Assessment Method and treated with intravenous methylprednisolone, which led to improved bilirubin and appetite by December 25, 2023 (local hospital, from December 6, 2023).

Dose adjustment and transfer: Liver function rebounded on methylprednisolone tapering (suspected drug-induced auto

Management of hyperlipidemia: Severe hyperlipidemia (total cholesterol 50.59 mmol/L) was unresponsive to feno

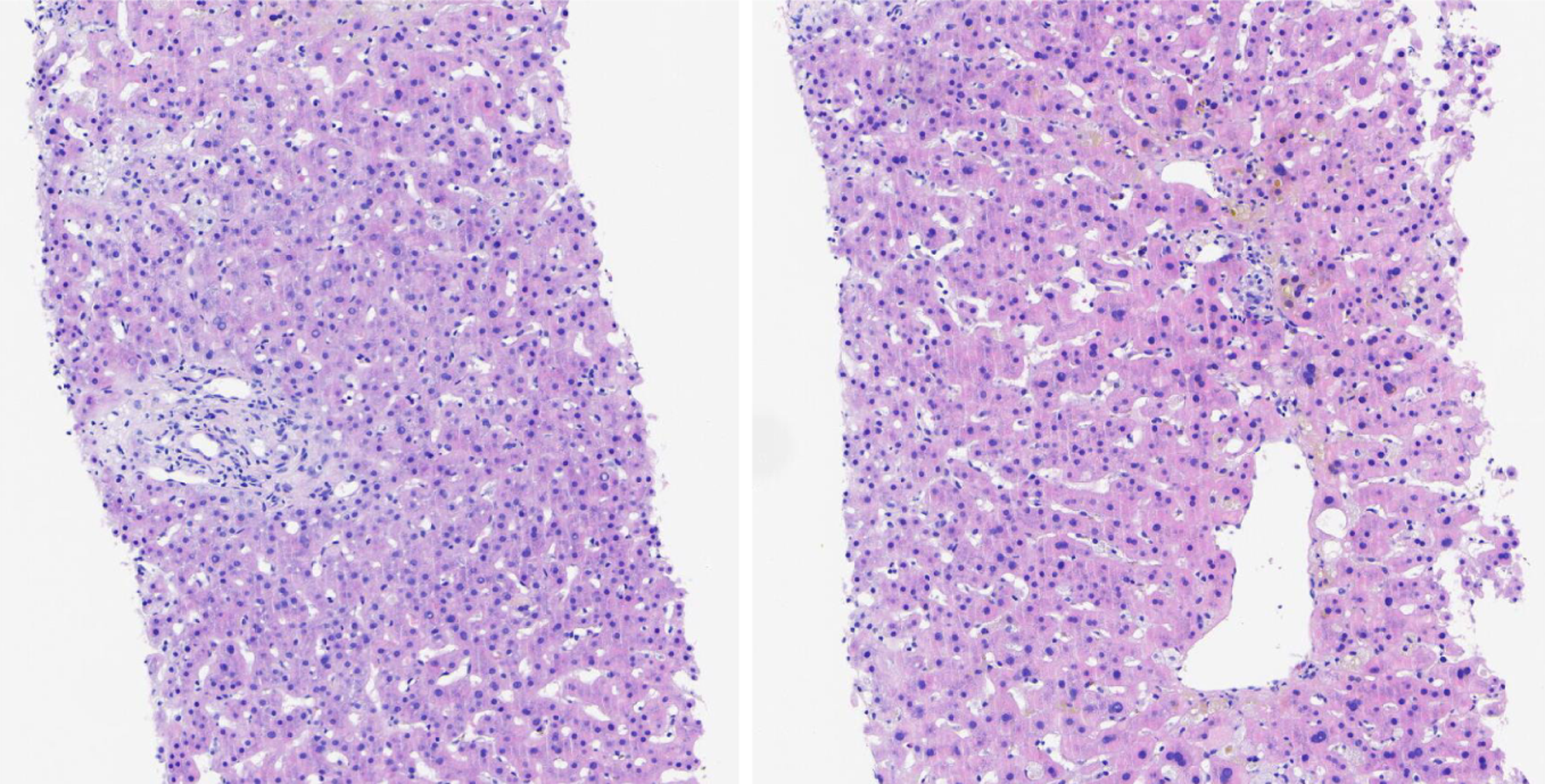

Glucocorticoid withdrawal and confirmation: Methylprednisolone was gradually reduced (transaminases improved) and stopped on January 22 (bilirubin 84.3 μmol/L). Liver biopsy (Figure 3) on January 31, 2024 confirmed drug-induced cholestatic hepatitis (no autoimmune liver disease).

On March 1, after the last liver function review (ALT 132.9 U/L, AST 136.0 U/L, TBIL 60.9 μmol/L, DBIL 51.6 μmol/L, albumin 34.3 g/L, GGT 306.0 U/L, and ALP 188.9 U/L), the patient was discharged from our hospital and continued regular liver-protecting medications, with monitored liver function improving steadily. As of July 26, the patient exhibited liver function abnormality, characterized by elevated GGT and ALP levels, with total cholesterol dropping to 6.28 mmol/L and triglycerides returning to normal. The therapeutic regimen of UDCA and statin therapy was main

For this study, the patient underwent routine examinations, including a complete blood count, urinalysis, and tests for liver and kidney function, thyroid function, coagulation function, lipid profile, blood glucose, electrolyte levels, auto

Patients who meet the definition of hyperlipidemia should first be evaluated for secondary causes. If there are no secondary causes, they should be further evaluated for a significant family history of high level of either LDL-C or high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels.When both are present, it is necessary to analyze whether the disease is monogenic or polygenic.

Risk factors that may cause hyperlipidemia include a high-fat diet, metabolic syndrome, chronic kidney disease (eGFR < 30 mL/minute/1.73 m2), alcohol intake > 30 g/d, and the use of certain medications [e.g., oestrogens, progestogens, corticosteroids (in small doses), thiazide diuretics, atypical antipsychotics, retinoids, and interferons][4]. The presence of the aforementioned factors in isolation may not be sufficient to cause a significant increase in cholesterol levels. However, when considered in conjunction with a background of multiple endogenous risk genes, these triggers may promote the development of hyperlipidemia. The elevated serum cholesterol and LDL-C levels associated with cholestatic liver disease are due to multiple impairments in cholesterol regulation, including increased production of free cholesterol, and the development of chronic cholestasis typified by the formation of abnormal lipoproteins that are not effectively re

A review of domestic and international literature suggests that the pathophysiological mechanism of hyperlipidemia caused by drug-induced cholestatic liver disease in this case may be related to the following.

Glucocorticoids: The body’s release of endogenous glucocorticoids during acute drug-induced liver injury has been shown to promote the synthesis and release of hepatic interleukin-10. Through the action of their homologous nuclear receptors, glucocorticoids have been observed to stimulate the expression of metabolic genes while inhibiting the pro-inflammatory gene network, thus exacerbating the hypercholesterolemia associated with acute cholestasis[5]. Conversely, persistent elevation of plasma glucocorticoid levels (hypercortisolism), a significant risk factor for metabolic complications, can further result in hypercholesterolemia and hypertriglyceridemia[6]. Furthermore, severe hyperlipidemia has been demonstrated to exacerbate intrahepatic cholestasis via a variety of pathways, including oxidative stress, inflammatory response, and enterohepatic circulation of bile acids[7]. In this case, during the early stages of acute, drug-induced cholestasis, endogenous glucocorticoid levels increased in response to the enhanced hepatic inflammatory state. However, subsequent treatment with exogenous hormones led to accelerated lipolysis and fatty acid oxidation[8], which further aggravated the level of secondary hyperlipidemia.

Disorders of bile acid metabolism: Drug-induced cholestatic liver disease is characterized by the interruption of bile flow, reduced secretion of bile acids as a result of the obstruction, and reflux of cholesterol and bile salts into the circulation. This leads to an increase in biliary lipoproteins and further affects cholesterol metabolism and excretion. This is based on enhancing liver 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase activity and inhibiting cytochrome P450 family 7 activity, which leads to increased cholesterol synthesis and impaired bile acid conversion. The result is abnormal basal metabolism of plasma lipoproteins. In the early stages of drug reactions, elevated concentrations of intrahepatic bile acids stimulate the synthesis of bile phospholipids. As cholestasis becomes chronic, however, impaired bile acid excretion prevents the maintenance of normal plasma cholesterol levels and the effective clearance of abnormal lipoproteins. Ultimately, this leads to the accumulation of bile phospholipids and free cholesterol in plasma. Concurrently, bile acids have been demonstrated to interfere with the catabolism of glucocorticoids in the liver, affect various enzymatic reactions, stimulate the production of steroid hormones, and further exacerbate lipid metabolism disorders[9].

Hepatocyte injury: Free cholesterol can be excreted into the bile as neutral sterols or converted to bile acids, esterified and stored in the liver as cholesteryl esters, or assembled into very low-density lipoproteins (LDL) and secreted into the circulation[10]. Drug-induced cholestasis has been demonstrated to result in hepatocellular injury and a decrease in the number of functional LDL receptors in damaged hepatocytes, thereby affecting the liver’s capacity to metabolize lipids and consequently causing elevated lipid levels.

Genetic factors: It has been demonstrated that individual susceptibility to drug-induced cholestasis and changes in lipid levels may be related to genetic background[11].

Lifestyle and diet: It is evident that dietary habits and lifestyle choices can also influence lipid levels, particularly in cases where drug-induced cholestasis is present.

The patient’s severe chylous plasma may have an impact on specimen testing, leading to artifactual errors such as pseudohyponatremia. Cholestasis can cause hyperlipidemia by increasing serum lipoprotein X (Lp-X)[12], but Lp-X and LDL have the same density and cannot be distinguished by standard lipoprotein ultracentrifugation. Lp-X is the primary cholesterol transporter protein in plasma, formed when serum is incubated with bilipids derived from unesterified cholesterol and phospholipids released from the bile ducts into the bloodstream[13]. Elevated Lp-X levels, characterized by substantial phospholipid and free cholesterol content, promote the development of pseudohyponatremia, a process that is further exacerbated by severe hypercholesterolemia[14]. After processing blood samples using high-speed centrifugation and performing corrections, blood sodium levels can generally be restored to normal.

In cases of Lp-X-associated hypercholesterolemia, statin therapy is ineffective in reducing cholesterol levels due to the inability of Lp-X to undergo LDL receptor-mediated hepatic clearance. Additionally, cholesterol absorption decreases in patients with severe cholestasis due to impaired micelle formation, resulting in a limited pharmacological effect of ezetimibe in lowering cholesterol levels by reducing intestinal cholesterol absorption[15]. This also explains why statins and ezetimibe were ineffective for this patient during the acute phase of cholestatic liver disease. When the patient’s condition did not improve with lipid-lowering drugs and there was no evidence of primary genetic defects, we concluded that the primary cause of the patient’s severely abnormal lipid levels was drug-induced cholestatic liver disease, even though her lipid levels exceeded the highest recorded levels of hyperlipidemia associated with cholestatic hepatitis. Treatment focused on promoting bile excretion and promptly reducing or discontinuing steroid use without overly emphasizing lipid-lowering therapy. Follow-up data after treatment revealed that the patient’s lipid levels did not increase after corticosteroid discontinuation and gradually returned to normal as intrahepatic cholestasis levels de

At the same time, we observed that the patient’s blood ammonia levels were consistently high. However, there were no clinical manifestations of hepatic encephalopathy, nor were there any abnormal findings on cranial magnetic resonance imaging. The high blood ammonia may be attributed to two primary causes: (1) The glucocorticoid application resulted in a significant decrease in the level of prealbumin, indicating the occurrence of vigorous protein catabolism. The amino acids resulting from protein catabolism serve as the primary source of nitrogenous compounds within the intestinal lumen. This, in turn, can lead to an increase in the production of ammonia in the intestinal tract; and (2) The urea diffused into the intestine during the hepatointestinal circulation process produces ammonia under the action of urease released by intestinal bacteria, which also increases blood ammonia levels.

In recent years, there have been an increasing number of reports of hyperlipidemia and cholestatic liver disease, both domestically and internationally. However, the etiology is often attributed to hyperlipidemia, and treatment primarily focuses on aggressive lipid-lowering therapy. The case that we present is relatively uncommon in clinical practice. It provides a complementary perspective to conventional diagnostic and therapeutic approaches and offers important evidence for further investigating the association between the two conditions. We present a unique case of a patient diagnosed with drug-induced cholestatic hepatitis complicated by hyperlipidemia, with lipid levels surpassing those reported in previous cases. For patients like this one, we recommend the following: (1) Using high-speed centrifugation to process laboratory test samples and correcting pseudohyponatremia caused by extremely high lipid levels; and (2) Addressing the underlying liver damage before initiating lipid-lowering therapy, especially for patients with Lp-X-driven hyperlipidemia. Using statins/ezetimibe blindly not only fails to effectively lower lipid levels, but also carries the risk of further exacerbating liver damage.

It is evident that patients treated with glucocorticoids at replacement levels or above experience a roughly fivefold increase in the risk of atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease in comparison to the general population. Furthermore, glucocorticosteroids have been observed to exert different effects on lipid indices and cardiovascular disease risk depending on various factors. The necessity for such assessment arises from the fact that glucocorticosteroids have different effects on lipid indices and cardiovascular disease risk depending on the dose, duration of treatment, and underlying diseases/indications. It is therefore recommended that a wide range of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular risk factors be routinely assessed, with a view to preventing and treating associated diseases such as diabetes, hyper

| 1. | Ousmaal MEF, Gaceb A, Khene MA, Ainouz L, Giaimis J, Andriantsitohaina R, Martínez MC, Baz A. Circulating microparticles released during dyslipidemia may exert deleterious effects on blood vessels and endothelial function. J Diabetes Complications. 2020;34:107683. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Litvinov RI, Peshkova AD, Le Minh G, Khaertdinov NN, Evtugina NG, Sitdikova GF, Weisel JW. Effects of Hyperhomocysteinemia on the Platelet-Driven Contraction of Blood Clots. Metabolites. 2021;11:354. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Baskurt OK, Meiselman HJ. Iatrogenic hyperviscosity and thrombosis. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2012;38:854-864. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Garcia-Cortes M, Robles-Diaz M, Stephens C, Ortega-Alonso A, Lucena MI, Andrade RJ. Drug induced liver injury: an update. Arch Toxicol. 2020;94:3381-3407. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 176] [Article Influence: 29.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | van der Geest R, Ouweneel AB, van der Sluis RJ, Groen AK, Van Eck M, Hoekstra M. Endogenous glucocorticoids exacerbate cholestasis-associated liver injury and hypercholesterolemia in mice. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2016;306:1-7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Arnaldi G, Scandali VM, Trementino L, Cardinaletti M, Appolloni G, Boscaro M. Pathophysiology of dyslipidemia in Cushing's syndrome. Neuroendocrinology. 2010;92 Suppl 1:86-90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 136] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Zhao DT, Yan HP, Han Y, Zhang WM, Zhao Y, Liao HY. Prevalence and prognostic significance of main metabolic risk factors in primary biliary cholangitis: a retrospective cohort study of 789 patients. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023;14:1142177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Karr S. Epidemiology and management of hyperlipidemia. Am J Manag Care. 2017;23:S139-S148. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Baptissart M, Vega A, Martinot E, Baron S, Lobaccaro JM, Volle DH. Farnesoid X receptor alpha: a molecular link between bile acids and steroid signaling? Cell Mol Life Sci. 2013;70:4511-4526. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Hussain MM. Intestinal lipid absorption and lipoprotein formation. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2014;25:200-206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 211] [Cited by in RCA: 246] [Article Influence: 20.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Fan L, You Y, Fan Y, Shen C, Xue Y. Association Between ApoA1 Gene Polymorphisms and Antipsychotic Drug-Induced Dyslipidemia in Schizophrenia. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2021;17:1289-1297. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ashorobi D, Liao H. Lipoprotein X-Induced Hyperlipidemia. 2024 Jan 8. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Adashek ML, Clark BW, Sperati CJ, Massey CJ. The Hyperlipidemia Effect: Pseudohyponatremia in Pancreatic Cancer. Am J Med. 2017;130:1372-1375. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Song L, Hanna RM, Nguyen MK, Kurtz I, Wilson J. A Novel Case of Pseudohyponatremia Caused by Hypercholesterolemia. Kidney Int Rep. 2019;4:491-493. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Reshetnyak VI, Maev IV. Features of Lipid Metabolism Disorders in Primary Biliary Cholangitis. Biomedicines. 2022;10:3046. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/