INTRODUCTION

Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) is the predominant cause of liver disease worldwide. Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH), previously known as non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, represents a clinically advanced stage of MASLD and is associated with an increased risk of end-stage liver disease[1]. MASH is characterized by hepatic steatosis, inflammation, hepatocyte ballooning and fibrosis. However, the degree of fibrosis defines the severity of disease progression[2]. The major causes of MASH pathogenesis are lifestyle risk factors, such as sedentary work, excessive consumption of Western food (high carbohydrate and fat content), smoking, alcohol intake, and environmental exposure[3]. A meta-analysis published in 2023[4] indicated that the global prevalence of MASLD and MASH is approximately 30.05% and 5.27%, respectively. Based on current statistics, MASLD and its aggressive form, MASH, have emerged as significant global health and economic burdens worldwide.

Plastic pollution is an enormous global concern that affects public and environmental health[5]. In 1960, global emission rates for plastic were 0.5 million tons, whereas by 2021, annual production rose to approximately 390.7 million tons[6]. According to recent data, only 9.8% of plastics are recycled or biodegradable, and the vast majority of plastics contribute to environmental pollution through their release into terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems[7]. MPs < 5 mm and nanoplastics (NPs) < 1 μm are continuously produced during plastic processing and environmental degradation. Various studies have shown the presence of MPs and NPs in human surroundings, including air, soil, water bodies, and food sources, which are directly or indirectly ingested by humans[8]. Recent studies have demonstrated that humans are exposed to MPs through the ingestion of contaminated food and inhalation, and these reactive forms of plastics accumulate in the liver, kidneys, placenta, lungs, semen, and blood[9-11]. In recent years, the negative impact of MPs on liver health has been demonstrated in several studies using preclinical models[12]. Additionally, a study found that MPs concentrations in human cirrhotic liver tissues were significantly higher than those without liver disease[13]. Mechanistic studies have shown that MPs alter hepatic lipid metabolism by activating cellular stress pathways, such as steatosis, inflammation, oxidative stress, ER stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, altered immune response, and fibrosis[12,14]. Despite clear mechanistic evidence from in vitro and in vivo models linking MP exposure to key pathological processes seen in MASLD/MASH, several limitations impede definitive conclusions regarding the role of MPs in MASH pathogenesis and our understanding of the mutual crosstalk among the different cellular pathways affected by MPs. Accordingly, this review aims to summarize the current state of knowledge in these areas and provide mechanistic insights into the toxic effects of MPs on liver metabolism and their deleterious effects on MASLD.

MOLECULAR MECHANISMS OF MPS INDUCED MASLD PROGRESSION

It has been increasingly recognized that exposure to MPs has become an environmental and health risk factor for the onset and progression of MASLD[15]. Ingestion of MPs leads to their accumulation in multiple organs, including the liver, and alters hepatic functions by activating several pathways, such as oxidative stress, endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, gut dysbiosis, and perturbation of endocrine action. Thus, it has been proposed that MPs promote MASLD progression via both hepatic and extrahepatic mechanisms, as described below.

Direct effect of MPs on liver steatosis

Hepatic lipid metabolism is a nutritionally and hormonally regulated process involving synthesis, storage, and degradation. Various studies have demonstrated that exposure to MPs, particularly polystyrene (PS) and polyethylene, increases the incidence of steatosis in the liver[16,17]. Many studies have shown that MPs alter the genomic and proteomic network landscapes of lipid metabolism, resulting in MASLD progression[18]. MPs can adsorb other toxicants, including persistent organic pollutants, and trigger nuclear receptors, such as peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) and liver X receptors[19-21]. Low levels of PPARα reduce anti-inflammatory responses and increase oxidative stress, thereby increasing MASLD[22]. Experimental mice exposed to MPs showed a consistent decline in the expression of PPARα target genes, including carnitine palmitoyltransferase I, thereby highlighting the negative effects of these pollutants on liver health and fatty acid metabolism[23]. Bisphenol A, a plasticiser often associated with MPs that acts like xenoestrogens, can also directly cause sterol regulatory element-binding protein (SREBP)-1c overexpression[24,25].

Direct effect of MPs on cellular stress pathways in the liver

Oxidative stress pathway: MPs can accumulate in various tissues, especially the liver, where they induce oxidative stress and cause cellular damage. Multiple studies have revealed that MPs increase hepatic reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, thereby promoting MASLD progression[26]. In this connection, co-exposure of zebrafish to a high-fat diet and MPs caused upregulation of inflammatory and lipogenic genes, coupled with increased oxidative stress, resulting in liver steatosis[27]. PS-MPs (PS-MPs) of 5 μm size caused extensive liver damage by suppressing the expression levels of oxidative stress-related proteins, such as sirtuin 3 and superoxide dismutase, to exacerbate oxidative stress in hepatocytes[28]. MPs, in conjunction with mercury exposure, increase the hepatic accumulation of mercury and oxidative stress[29]. Polyvinyl chloride MPs combined with cadmium-induced oxidative stress promotes hepatic lipid accumulation, fibrosis, and hepatocyte apoptosis in birds[30]. Furthermore, prenatal exposure to high-fat diets combined with MPs induces lipid peroxidation, oxidative stress, and liver injury in mouse offspring[31].

ER stress and unfolded protein response pathway: The ER is a major component of protein folding, modification, and trafficking. Exposure to MPs promotes the accumulation of unfolded or misfolded proteins in the ER lumen, resulting in the activation of the unfolded protein response within cells[32]. Heavy metals, such as lead, mercury, and cadmium, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, and endocrine disruptors, are adsorbed by MPs, and the adsorption of other carriers promotes cellular uptake, aggravating ER stress by producing ROS and enhancing protein misfolding and oxidative stress[31,33,34]. PS-NPs increase ER stress markers in the liver, such as CCAAT-enhancer-binding proteins homologous protein, activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4), binding immunoglobulin protein, and X-box binding protein 1[35,36]. The upregulation of protein kinase RNA-like ER kinase, eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 alpha, ATF4, and spliced X-box binding protein 1 is correlated with ER homeostasis disturbances. The inositol-requiring enzyme 1 pathway and other unfolded protein response components boost lipogenesis and cholesterol synthesis genes such as SREBP-1c, FASN, and ACC1[37,38]. MPs disrupt ER-mediated lipid signaling and accelerate hepatic steatosis and fibrosis in mice[39]. These effects hinder the nuclear translocation of nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2, causing ER stress and MASH[40]. Another study indicated that PS-NPs induce ER stress by activating the protein kinase RNA-like ER kinase-ATF4 pathway and increases lipid synthesis via ATF4-PPARγ/SREBP-1 signaling. The ER stress inhibitor 4-phenylbutyric acid also reduced lipid metabolic dysfunction, confirming the central importance of ER in PS-NP-induced hepatotoxicity[38].

Mitochondrial dysfunction and energy imbalance: Mitochondria are the powerhouses of the cell and are responsible for oxidative phosphorylation to generate adenosine triphosphate. Moreover, they regulate other cellular processes, such as the generation of ROS and apoptosis[41]. In vivo studies have revealed that the penetration of MPs into the mitochondria can cause their enlargement and loss of cristae[42]. In addition to morphological changes, MPs disrupt mitophagy and mitochondrial dynamics, alter calcium homeostasis, and reduce mitochondrial membrane potential[43].

Another study showed that PS-NPs accumulated in mitochondria and activated PTEN Induced kinase 1/parkin-mediated mitophagy in mice[44]. Mitophagy is the autophagic degradation of damaged mitochondria[45]. However, constitutive activation of mitophagy reduces the number of mitochondria necessary for viability and causes cell death[46]. Along with mitophagy, MPs/NPs also affect the mitochondrial fission/fusion process, which is crucial for maintaining mitochondrial number and function[47]. According to recent findings, the interaction of PS-NPs with mitochondria leads to an increase in the expression of dynamin-associated protein situated in the cytosol and on the mitochondrial surface, which tends to increase its fission process[48]. Notably, the inhibition of dynamin-associated protein mitigated the adverse effects of MPs on human hepatic cells[48].

Direct effect of effect of MPs on hepatic inflammation

MPs trigger inflammatory responses in the liver. They cause the release of damage-associated molecular patterns and cytokines from stressed hepatocytes which can activate immune cells in the liver. MPs also induce the expression of inflammatory signals, such as tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) and interleukin-6 (IL-6), which promote liver injury[37,49,50]. TNF-α is primarily produced by Kupffer cells and hepatocytes in response to stressors. Exposure to MPs increased the TNF-α levels and induced apoptosis in hepatocytes. Increased TNF-α levels disrupt insulin signaling, causing increased lipid accumulation in the liver[51]. Chronic exposure to MPs increases IL-6 levels, leading to inflammation and fibrosis[52]. Furthermore, both zebrafish and rodents exposed to MPs have elevated IL-6 levels[53-55], which are associated with hepatocellular ballooning and fibrosis. Exposure to MPs activates the inflammasome complex comprised of IL-1β via nucleotide-binding and oligomerization domain-leucine rich repeats, and pyrin domain-containing protein 3[56-58]. Moreover, increased IL-1β recruits leukocytes and activates stellate cells, which further promotes fibrogenic potential[59]. A recent study suggested that exposure to murine PS-MPs increased IL-1β expression and showed histological evidence of hepatic damage[60].

Kuffer cells engulf MPs and activate the immune system via toll-like receptor 4, which further initiates the nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cell (nuclear factor kappa B) pathway, leading to increased production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α and IL-6[61]. Kupffer cell polarisation to the M1 or M2 phenotype plays an integral role in this process, as M1 polarisation induces a pro-inflammatory state, whereas M2 polarisation is anti-inflammatory and involved in tissue repair[55]. Interestingly, a recent study provided compelling evidence that PS-MPs significantly changed the M1/M2 ratio in mouse liver tissue. Furthermore, there was a marked increase in inducible nitric oxide synthase expression compared to arginase 1, indicating that M1 activation predominated over M2[62].

Direct effect of MPs on liver fibrosis

Numerous animal studies have described the significant profibrotic effects of MPs on the liver[16]. Specifically, MPs measuring 0.1 μm penetrated hepatocytes, resulting in liver and DNA damage and activation of the cyclic GMP-AMP synthase-stimulator of interferon genes pathway, which subsequently promoted hepatic inflammation and fibrosis[63]. Moreover, stimulator of interferon genes inhibition mitigates liver fibrosis by obstructing nuclear factor kappa B translocation and fibronectin expression[63]. Similarly, PS-MPs have been implicated in inducing liver fibrotic injury, macrophage recruitment, and macrophage extracellular trap formation, leading to inflammation and epithelial-mesenchymal transition associated with fibrosis[64]. Another study demonstrated that the ingestion of polyethylene microbeads altered hepatic fatty acid metabolism, increased inflammation, and exacerbated liver fibrogenesis in mice[16]. Additionally, exposure to MPs in diabetic mice disrupts liver structure and function, impairs glucose tolerance, promotes hepatic gluconeogenesis, and induces liver fibrosis via the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway[33]. A study revealed that oral exposure to polyethylene terephthalate MPs at a dose of 1 mg/day (with a diameter of 1 μm) over 42 days resulted in hepatocyte swelling, inflammatory cell infiltration, and collagen deposition[50]. Using a next-generation sequencing approach, a set of three genes, Acot3, Abcc3, and Nr1i3, was identified as being involved in the development of liver fibrosis under chronic exposure to PS-MPs[18]. Additionally, Li et al[60] investigated the effects of a 12-week exposure to 0.5 μm PS-MPs (submicroplastics) in drinking water administered to ApoE-deficient mice fed either a chow diet or a Western diet to examine the effects of MPs on fibrosis in MASH and found that MPs predominantly accumulated in the liver and were excreted in faeces[60]. Histologically, sub-MPs significantly increased non-alcoholic fatty liver activity scores, hepatic steatosis (Oil Red O-positive area), and fibrosis (Masson-positive area), with maximal severity observed in the Western diet + MP group[60]. Collectively, these studies demonstrate that various types of MPs induce liver damage, inflammation, and fibrosis through multiple mechanisms and underscore the potential health risks associated with MP exposure.

Extra-hepatic effects of MPs on MASLD via gut dysbiosis

Recent findings have provided evidence of the detrimental effects of MPs accumulation in several human organs[13,26]. Chronic exposure of mice to polyethylene terephthalate MPs induced gut dysbiosis, hepatotoxicity, and altered hepatic lipid metabolism via nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase, and paraoxonase 2[65]. Additionally, exposure to a low dose of PS-MPs decreased intestinal length and expression of occludin and zonula occludens-1 proteins, resulting in increased lipopolysaccharide (LPS) secretion in the intestine[66]. The increase in LPS levels is thought to promote “leaky gut” via the secretion of endotoxins and contribute to the progression of MASH[66-68]. Other studies have demonstrated that exposure to plastics promotes dysbiosis and leaky gut by increasing the expression of gasdermin and caspase-1[61].

MPs as endocrine disruptors: Impact on MASLD pathogenesis

The endocrine system comprises several glands that secrete hormones that perform distinct metabolic functions and maintain homeostasis[69,70]. Exposure to PS-MPs has been associated with thyroid dysfunction in zebrafish, resulting in developmental and growth-related problems[21]. Additionally, exposure of PS-MPs to male Swiss albino mice increased serum levels of thyroxin, aspartate aminotransferase, alanine transaminase, alkaline phosphatase, amylase, malondialdehyde, and calcium[71]. Moreover, MPs caused histological changes in the thyroid gland, such as a reduction in the number of parafollicular cells and an increase in the mean follicle length and width, compared with the control group[72]. Furthermore, combined exposure to MPs and polychlorinated biphenyls significantly decreased the levels of thyroid-stimulating hormone beta subunit, corticotropin-releasing hormone, and thyroxine[73]. Given the important role of thyroid hormones in liver metabolism[74] and MASLD progression, any alteration in their levels by MPs could have a detrimental effect on MASLD progression. Similarly, PS-MPs exposure in male mice caused dramatic changes in the structure of the adrenal gland, such as a reduction in cortical thickness and disarrangement of cortical cells in a dose-dependent manner[75]. Moreover, PS-MPs decreased serum corticosterone levels, accompanied by reductions in essential adrenal synthesising enzymes, such as steroidogenic acute regulatory protein, P450scc, and 3beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase/delta(5)-delta(4)-isomerase type 1[75]. Additionally, MPs disturb the male reproductive system through several mechanisms, including disruption of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis, toxicity in testicular cells, interference with the antioxidant defense system, and induction of oxidative stress[76]. The individual and combined effects of PS-NPs/PS-NPs + LPS in male mice significantly decreased plasma and testicular testosterone levels[77]. In females, MPs increase oxidative stress in the ovaries, followed by degradation of the granulosa cell layer, resulting in decreased serum oestradiol levels, which is also associated with reduced luteinizing hormone and follicle-stimulating hormone secretion by the pituitary gland in the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis[78,79]. Notably, a previous study showed that low serum estradiol levels were associated with MASLD pathogenesis in female mice[80].

Integrated effect of direct hepatic and extra-hepatic action of MPs on MASLD progression

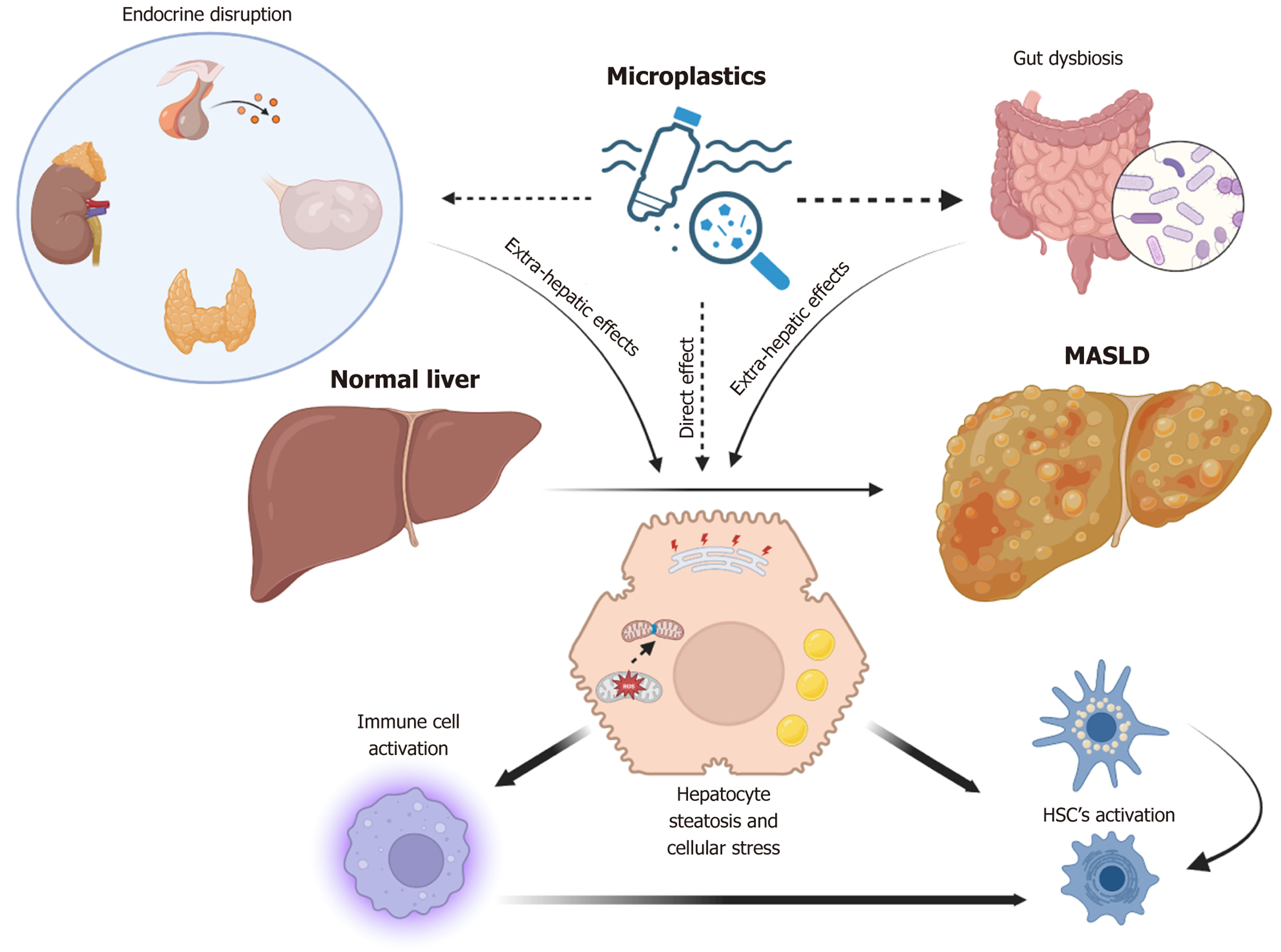

The influence of MPs on metabolic-associated steatotic liver disease appears to be due to cumulative effects on the mammalian endocrine system and gut microbiome, as well as on liver cells (Figure 1). Various endocrine-disrupting chemicals or toxic substances present in plastics, either as additives or adsorbed by MPs, can easily enter the human body. These substances act as agonists or antagonists of a wide array of hormonal receptors and can cause endocrine-related toxicity. This toxicity may significantly alter the functions(s) of hormones that regulate hepatic lipid metabolism and inflammation. Concurrently, the induction of gut dysbiosis may cause the release of several pro-inflammatory molecules and potentially exacerbate an already metabolically stressed liver in a lipotoxic environment. Furthermore, the direct entry of MPs into different liver cell types, including hepatocytes, immune cells/macrophages, and hepatic stellate cells, may intensify the prevailing pathological interactions among these cell types, thereby worsening MASLD or MASH.

Figure 1 Schematic representation showing both the extra-hepatic and direct hepatic effects of microplastics in contributing to metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease progression.

Microplastics, either directly or through extrahepatic signaling, lead to alterations in the cellular state of liver cells, including hepatocytes, immune cells, and hepatic stellate cells. Microplastics induce steatosis and cellular stress, including mitochondrial damage and fission in hepatocytes, which may result in the release of pro-inflammatory/pro-fibrotic cytokines. This release may subsequently activate immune cells and hepatic stellate cells, leading to increased inflammation and fibrosis in metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. MASLD: Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease; HSC: Hepatic stellate cells.

CONCLUSION

The conditions of MASLD and its more severe form, MASH, have become prominent global health and economic challenges because of their high prevalence worldwide. Concurrently, the escalating use of plastics poses a significant threat to human and environmental health. MPs have been identified as environmental risk factors that may exacerbate the progression of MASLD through mechanisms such as pro-lipogenic signaling, increased cellular stress pathways, and mitochondrial dysfunction. Additionally, MPs activate inflammatory pathways, elevating pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β, which may contribute to liver injury and fibrosis. Beyond their direct impact on the liver, MPs may influence MASLD pathogenesis by altering the gut microbiome and functioning as endocrine disruptors, thereby diminishing hormone synthesis and hepatic action (Figure 1). However, there are certain limitations to interpreting animal studies concerning MPs. Many of these studies utilized concentrations or exposure routes that do not accurately reflect typical human environmental or dietary exposure levels and methods, which may limit their translational applicability. Moreover, chronic low-level exposure to MPs and their interactions with other environmental stressors or metabolic risk factors remain insufficiently explored. Additionally, large-scale epidemiological studies or clinical investigations in humans linking MP burden to the incidence and/or progression of MASH are lacking. Consequently, future research should incorporate environmentally relevant exposure models, investigate the physicochemical properties of particles that influence hepatic toxicity, and conduct human cohort studies to establish causality and assess risk stratification. These insights should inform strategic global policies aimed at reducing both direct and indirect exposure to MPs and mitigating the health and economic burden of environmental and lifestyle-related risk factors causing metabolic diseases.