INTRODUCTION

Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH) previously known as non-alcoholic steatohepatitis is clinically alarming state of a broader disease spectrum known as metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) or non-alcoholic fatty liver disease[1]. MASH pathogenesis involves complex interactions among metabolic, inflammatory, and fibrotic processes[1]. The progression from simple steatosis to MASH is driven by multiple factors, including insulin resistance, lipotoxicity, oxidative stress, and mitochondrial dysfunction[1]. Alcoholic steatohepatitis (ASH) is a severe form of alcoholic liver disease characterized by fat accumulation, inflammation, and liver injury due to excessive alcohol consumption[2]. ASH pathogenesis involves complex mechanisms, including alcohol-induced oxidative stress, inflammation, and alterations in the gut microbiome[2]. Interestingly, ASH shares many histological features with MASH despite their different etiologies. Both conditions involve macrovesicular steatosis, neutrophilic inflammation, and ballooning degeneration of hepatocytes[3].

Notably, a common feature of both MASH and ASH involves cellular plasticity of common cell types, including hepatocytes, macrophages, and hepatic stellate cells (HSCs)[4,5]. This cellular plasticity involves dramatic changes in the transcriptome of hepatic cells in response to diet and alcohol, which transform them from a physiological quiescent state to a pathologically activated state associated with the expression of several pro-lipogenic, pro-inflammatory, and pro-fibrotic proteins[4,5].

Histone modifications play a significant role in the pathogenesis of MASH and ASH, which are major contributors to altered transcriptomic-driven cellular plasticity[6,7]. Epigenetic alterations, including histone modifications, dynamically regulate the expression of genes involved in hepatic lipid metabolism, insulin resistance, mitochondrial damage, oxidative stress response, and the release of inflammatory cytokines in response to intracellular nutrient/energy status, all of which are implicated in MASH/ASH development[6,7]. These modifications can influence gene expression without altering the underlying DNA sequence, thereby offering a new perspective on MASH pathogenesis.

Histone lactylation is a novel PTM discovered in 2019[8] that primarily occurs on the lysine residues of histone proteins. It is a metabolic stress-related histone modification that plays a crucial role in regulating gene expression[9]. Histone lactylation is intrinsically connected to cell metabolism, particularly glycolysis, and serves as an indicator of cellular lactate levels[10]. This modification is induced by hypoxia and lactate production, which links metabolic reprogramming with epigenetic modifications. Since increased lactate production is generally associated with MASH[11-13] and ASH[14] progression, both histone and non-histone lactylation may have a profound effect on the pathogenesis of these diseases.

In this review, we discuss our present understanding of the role of histone lactylation in the pathobiology of MASH and ASH, and its therapeutic targeting to counter disease progression.

HISTONE MODIFICATION: REGULATION, VERSATILITY AND IMPLICATIONS IN GENE REGULATION

Histone modifications are post-translational, dynamic, and reversible covalent modifications that regulate chromatin structure and gene expression without altering DNA sequence[15]. These modifications occur on the N-terminal tails of histone proteins, primarily histones H2A, H2B, H3, and H4, and various covalent changes constitute the histone code. This code is dynamically regulated by three classes of proteins: “Writers” that add modifications, such as histone acetyltransferases (HATs), histone methyltransferases (HMTs), kinases, and ubiquitin ligases, deposit specific chemical groups on histones. “Erasers” that remove modifications such as histone deacetylases (HDACs), histone demethylases (HDMs), phosphatases, and deubiquitination, and “readers” of these proteins with domains such as bromodomains, chromodomains, Tudor domains, and plant homeodomain fingers bind modified histones and interpret the modifications to facilitate biological function. The most common types of histone modifications include acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation, ubiquitination, and sumoylation[15]. Each modification occurs at specific amino acid residues and is catalyzed by epigenetic regulators. These modifications can either activate or repress gene expression depending on the type of modification and the context in which it occurs[16]. Histone acetylation is typically associated with transcriptional activation. This involves the addition of acetyl groups to lysine residues, which neutralizes their positive charge and reduces the affinity between histones and DNA[16]. This leads to a more relaxed chromatin structure, allowing transcription factors to access DNA. HATs mediate this process, whereas HDACs remove acetyl groups to restore a compact chromatin state and repress transcription[16]. However, histone methylation is complex. Methylation can occur on lysine or arginine residues and may lead to either activation or repression, depending on the site and degree of methylation. For example, the trimethylation of histone H3 at lysine 4 is generally associated with active promoters, whereas trimethylation at lysine 27 is linked to gene repression[16]. Enzymes known as HMTs and HDMs regulate this dynamic process. Phosphorylation of histones, particularly serine and threonine residues, is often associated with chromatin condensation during mitosis and DNA damage responses[16]. For example, the phosphorylation of histones H2A at serine 139 (γH2AX) is a marker of DNA double-strand breaks and recruits DNA repair machinery to the site of damage. The ubiquitination of histones involves the covalent attachment of ubiquitin molecules. Mono-ubiquitination of H2B is generally linked to active transcription, whereas ubiquitination of H2A is often correlated with repression[16]. In recent years, new types of histone modifications have been discovered, such as crotonylation such as H3K18 crotonylation is associated with active transcription, especially in germ cells[15]. Similarly, β-hydroxybutyrylation is another metabolic-linked modification observed under conditions such as fasting and ketogenic diets, and possibly promotes gene activation[15]. Lactylation, the most recently discovered histone modification, is associated with metabolic activity and immune regulation. The enzyme p300 has been identified as a potential lactyltransferase that adds a lactyl group to H3K18[15].

HISTONE MODIFICATION AND MASH/ASH DISEASE BIOLOGY

Histone methylation is catalyzed by HMTs, while HDMs remove methylation marks on lysine or arginine residues. Loss of HMTs has a pleiotropic effect on MASH pathogenesis in mice. In mice lacking the histone 3 at lysine 9 (H3K9) methyltransferase known as suppressor of variegation 39 homolog 2 a milder form of MASH was observed when compared to their wild-type counterparts, after being fed a diet high in fat and carbohydrates[17]. Mechanistically, this was linked to the repression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma transcription in macrophages by variegation 39 homolog 2, which promoted a pro-inflammatory macrophage 1 (M1) phenotype rather than an anti-inflammatory macrophage 2 (M2) phenotype, thereby increasing hepatic inflammation[17]. By contrast, haploinsufficiency of the HMTs myeloid-lineage leukemia gene results in hyperglycemia, hyperinsulinemia, and development of MASLD in mice[18]. However, under MASH conditions, mice that lack one allele of the histone methyl transferase myeloid lineage leukemia-4 (MLL4) gene show resistance to liver steatosis, inflammation, and fibrosis when compared to wild-type controls[19]. Furthermore, transcriptome analysis of the livers of control and MLL4 (+/-) mice identified pro-inflammatory genes regulated by the nuclear factor kappa B signaling pathway as major target genes of MLL4[20]. In line with these findings, inhibition of another HMT, enhancer of zeste homolog 2, reduced the expression of pro-inflammatory and fibrosis markers in MASH mice[21]. Moreover, the genetic ablation of methyltransferase like 3 (METTL3) specifically in hepatocytes promotes the transition from non-alcoholic fatty liver to MASH by enhancing the uptake of hepatic free fatty acids (FFAs) through cluster of differentiation and triggering inflammation via chemokine ligand 2[22]. Conversely, the pharmacological inhibition of euchromatic histone lysine N-methyltransferase, also known as G9a, significantly exacerbates the progression of MASH in mice and heightens the susceptibility of human hepatic cells to apoptosis and intracellular stress induced by palmitic acid[23].

In a similar manner, the HDM known as Jumonji domain-containing protein 2B is involved in eliminating the repressive histone marks, dimethylation of H3K9 and trimethylation at lysine 9, at the promoter of lipogenic genes, which may play a part in the development of hepatic steatosis[24]. Moreover, when HDM lysine 7A was overexpressed in mice, it led to hepatic steatosis, which was associated with an upregulation of hepatic diacylglycerol O-acyltransferase 2 expression[25]. Activation of histone acetylation by histone acetylase p300 has been linked to the increased progression of MASLD[26,27], and pharmacological inhibition of p300 has been shown to mitigate MASH severity in mice[28-30]. Consistent with this HDACs namely sirtuin 1 (SIRT1) has been shown to prevent MASH pathogenesis in animal models[31].

Histone methylation, alongside histone acetylation, plays a crucial role in the development of alcoholic liver disease[6,32]. Studies have shown that alcohol consumption alters the patterns of histone methylation in hepatocytes, with observed changes including reduced dimethylation of H3K9, increased dimethylation of H3K4, and increased trimethylation of H3K27[33]. These alterations in histone methylation patterns are associated with changes in gene expression, suggesting a direct link between histone modifications and ASH[33]. For instance, increased H3K9 methylation at promoter regions correlates with the downregulation of genes such as l-serine dehydratase and cytochrome P450 2C11[33], while increased H3K4 methylation and reduced H3K9 methylation in regulatory regions are associated with the upregulation of genes such as alcohol dehydrogenase I (ADH I) and glutathione S-transferase Yc2[33].The relationship between alcohol consumption and histone methylation is further complicated by the role of S-adenosyl-l-methionine (SAM), a key molecule in histone methylation processes. SAM, which is primarily produced in the liver, serves as the major methyl donor for histone methylation. Alcohol consumption has been shown to cause hepatic SAM deficiency through various mechanisms, potentially disrupting normal histone methylation processes[34]. SAM supplementation has been found to attenuate alcohol-induced liver injury, suggesting that restoring SAM levels may help reverse alcohol-induced histone demethylation[34].

Alcohol intake activates HATs and inhibits HDACs by altering the histone acetylation levels[6]. Ethanol increases H3K9 acetylation in rat hepatocytes[35]. Chronic ethanol treatment enhances H3K9 acetylation in the ADH I gene regions, increasing its expression[36]. H3K9 acetylation affects lipid metabolism genes, promotes lipogenesis, and inhibits lipolysis in ASH[37]. HDACs, SIRT1, and SIRT2 also play a role in balancing gene silencing and activation in ASH through histone acetylation[38,39]. Inhibition of the histone acetylation reader bromodomain-4 suppresses chemokine expression and reduces neutrophil infiltration in alcoholic hepatitis models[40]. Histone acetylation in ASH affects alcohol metabolism, fat accumulation, and hepatic inflammation through the regulation of specific genes such as ADH I, carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1 alpha, and patatin-phospholipase containing-domain protein[41].

HISTONE LACTYLATION, CROSSTALK WITH OTHER HISTONE MODIFICATION AND REGULATION OF GENE EXPRESSION

Lactate, produced during both aerobic and anaerobic glycolysis, is increasingly being recognized as a bio-signaling molecule beyond its traditional metabolic role[9]. Under aerobic conditions lactate production can occur under conditions of high glucose levels, local hypoxia or via Warburg effect in neoplastic liver cells[42,43]. Under anaerobic conditions that inhibit the tricarboxylic acid cycle, pyruvate is reduced to lactate in the cytoplasm by lactate dehydrogenase. Additionally, glutaminolysis in cancer cells can lead to a higher production of lactate[42,43]. Lactate metabolism follows two pathways: It is either oxidized to pyruvate via Cori cycle, or it is converted to lactyl-CoA, catalyzed by HAT for histone lysine lactylation.

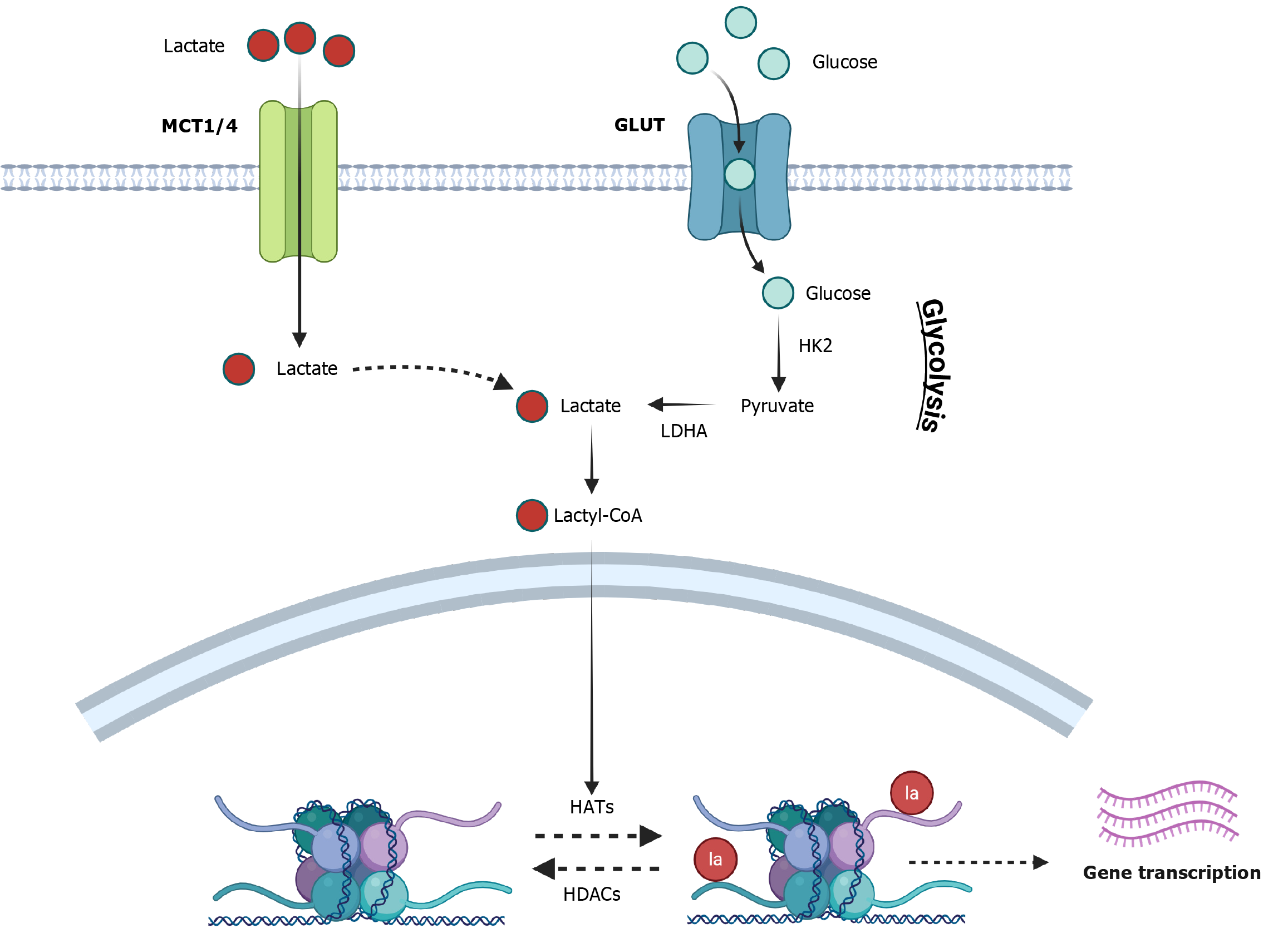

Histone lysine lactylation, identified in 2019[8], represents a novel PTM that connects lactate metabolism to epigenetic regulation, thereby influencing gene transcription and immune responses (Figure 1). This process, mediated by lactate, exhibits kinetic differences from acetylation, occurring over a 24-hour period[8]. It has been hypothesized that lactylation involves a “lactate clock” mechanism, wherein accumulated lactate initiates modification[8]. Histone lactylation involves “writers,” such as p300, a HAT that facilitates lactylation, and “erasers,” including HDAC1-3 and SIRT1-3, which function as delactylases[8] (Figure 1). Given that writers, such as the p300/CBP family of acetyltransferases, and erasers, such as HDACs, for histone lactylation and acetylation may exhibit overlapping substrate specificities, this can result in direct competition or cooperation on identical lysine residues. This dynamic and competitive interaction is pivotal in the regulation of gene activation and repression, particularly under conditions of metabolic stress or alterations in glycolytic flux[44]. The interplay between lactylation and acetylation is contingent upon cell type and stimulus, indicating intricate regulatory dynamics. In macrophages, the lactylation and acetylation of histones are responsive to distinct stimuli and exhibit unique temporal dynamics. For instance, following bacterial challenge, acetylation occurs early, facilitating the activation of pro-inflammatory genes, whereas lactylation increases subsequently, promoting a transition to reparative, anti-inflammatory gene programs[8]. This suggests that crosstalk is not only spatial, involving the same or adjacent residues, but also temporal, contributing to gene expression shifts during immune responses[45].

Figure 1 Molecular mechanism of histone lactylation.

Lactate acts as a bio-signaling molecule beyond its metabolic role. Lactate transport from lactate transporters, such as monocarboxylate transporter 1 and 4, (MCT1/4) and its synthesis via glycolysis involving hexokinase 2 (HK2) and lactate dehydrogenase A (LDHA) results in the conversion of lactate into lactyl-coenzyme A. Following this “writers” like p300 facilitate lactylation, while “erasers” such as histone deacetylases (HDACs) 1-3 and sirtuin 1-3 act as delactylases. The lactylation of histone 3 at lysine 18 results in the expression of target genes. GLUT: Glucose transporter; HATs: Histone acetyltransferases; la: Lactyl.

Direct competition for lysine residues and the recruitment of shared “reader” proteins involving lactylation and other histone modification is also observed. For example, lysine methylation and acetylation can compete or cooperate at specific sites (e.g., H3K9 or H3K27), sometimes with direct metabolic input, as acetyl-CoA, SAM, and lactate concentrations are interdependent[46]. Similarly, crotonylation, another acylation, displays site overlap and may functionally antagonize lactylation- or acetylation-driven transcriptional outputs[47]. Similarly, “reader” selectivity with specific histone modification such as for lactylation, the tripartite motif containing 33 bromodomain appears to uniquely recognize lactylated lysines over acetylated ones conferring preferential histone modification readouts[48].

Histone lactylation promotes oncogene expression and tumor progression, particularly in ocular melanoma and tumor-infiltrating myeloid cells[49]. Additionally, lactylation modulates macrophage polarization (M1 to M2), influencing inflammatory responses and sepsis severity[50]. Lactylated H3K18 (H3K18 La) has been implicated in uterine receptivity and gene activation during early development[51]. Lactate from myofibroblasts induces histone lactylation in macrophages, thereby promoting pro-fibrotic gene expression[52]. Thus, histone lactylation constitutes a significant epigenetic mechanism with extensive physiological and pathological relevance. Its regulation, interaction with other PTMs, and its role in disease pathogenesis warrant further investigation.

HISTONE LACTYLATION AND HEPATIC STEATOSIS IN MASH

Recently, Meng et al[13] investigated the role of lactate dehydrogenase A (LDHA)-mediated histone lactylation in MASLD progression. The study used a high-fat diet-treated mouse model and FFA-treated L-02 cells[13]. This study showed that LDHA and H3K18 La levels were upregulated in FFA-treated cells and high-fat diet-fed mice, and LDHA knockdown prevented lipid accumulation, decreased total cholesterol and triglyceride levels, and downregulated lipogenesis-related proteins both in vitro and in vivo. Furthermore, LDHA-induced H3K18 La was enriched in the proximal promoter of METTL3, which increased its expression. The study concluded that LDHA-induced H3K18 La promotes MASLD progression by elevating METTL3 expression, which in turn promotes N6-methyladenosine methylation and stabilizes stearoyl-coenzyme A desaturase 1, thereby increasing steatosis in hepatocytes[13] (Figure 2). Thus, this study provides direct evidence of histone lactylation-mediated alterations in lipogenesis in MASLD/MASH. In contrast, a study on the effects of Huazhuo Tiaozhi granule (HTG), a traditional Chinese medicine formula, on dyslipidemia showed that the beneficial effects of HTG total cholesterol and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels in both human patients and animal models were associated with increased lactylation in hepatocytes, particularly affecting histones H2B and H4[53]. This contrasts with the findings of Meng et al[13]. This study argues that HTG-mediated anti-steatotic effects were positively correlated with enhanced histone lactylation-mediated downregulation of miR-155-5p expression, which drives MASH pathogenesis[53]. Therefore, the differential effect of histone lactylation on hepatic steatosis appears to be related to the lactylation of specific histone subunits.

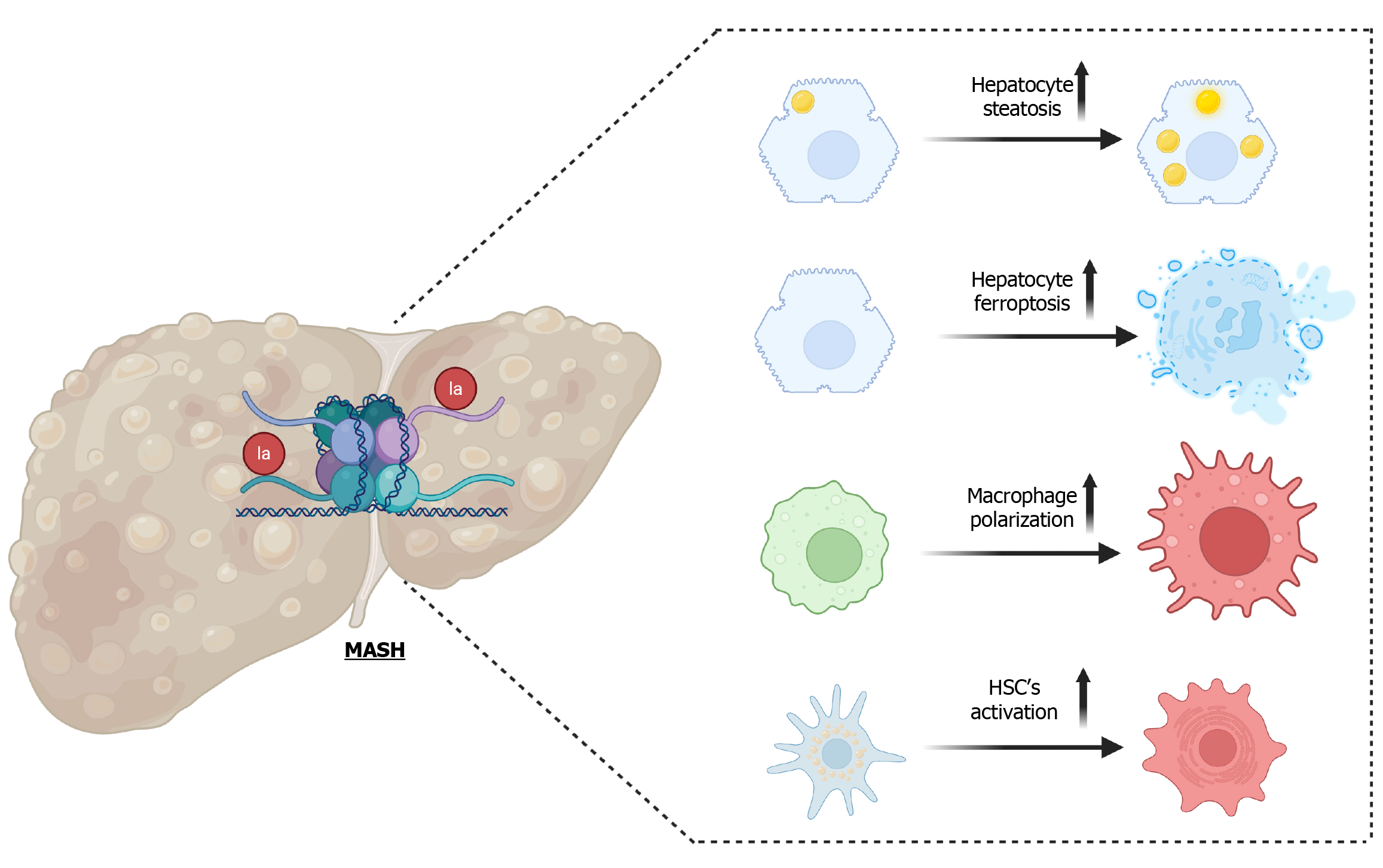

Figure 2 Role of histone lactylation in metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis pathogenesis.

Preclinical models of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH) have shown increased cellular plasticity in response to histone lactylation in the hepatic cells. In particular, increased hepatocyte steatosis and cell death were associated with fat-induced histone lactylation. Similarly, increased histone lactylation has been linked to hepatic macrophages and hepatic stellate cell activation in MASH. These findings highlight the complex interplay between metabolic reprogramming and epigenetic remodeling in MASH progression and suggest potential therapeutic targets to counter lipogenic, inflammatory, and fibrotic events in MASH.

HISTONE LACTYLATION AND HEPATOCYTE INJURY IN MASH

A study investigating the role of tectorigenin (TEC), an anthocyanin monomer, in improving MASH found that TEC significantly inhibited FFA-induced ferroptosis in hepatocytes both in vitro and in vivo[54]. Mechanistically, a novel transfer RNA-derived fragment, tRF-31R9J, which serves as a key mediator of TEC’s hepatoprotective effects of TEC, recruits HDAC1 to reduce histone lactylation and acetylation modifications on pro-ferroptosis genes such as activating transcription factor 3 (ATF3), activating ATF4, and glutathione-specific gamma-glutamylcyclotransferase 1, thereby inhibiting their expression[54]. Consequently, overexpression of tRF-31R9J suppressed ferroptosis and enhanced cell viability in steatotic hepatocytes, whereas knockdown of tRF-31R9J partially counteracted TEC’s inhibitory effects of TEC on ferroptosis[54]. Similarly, experiments in MASH mouse models demonstrated that TEC treatment reduced lipid accumulation, decreased ferroptosis markers, and improved liver function, all of which are partially dependent on tRF-31R9J. Furthermore, transcriptome analysis revealed that tRF-31R9J regulated multiple ferroptosis-related genes and pathways. Chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing and chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by quantitative polymerase chain reaction experiments confirmed that tRF-31R9J reduced histone lactylation levels near the promoters of ATF3, ATF4, and gamma-glutamylcyclotransferase 1 through HDAC1 recruitment. This study thus provides a novel insight into the molecular mechanisms underlying TEC’s hepatoprotective effects of TEC in MASH, highlighting the importance of transfer RNA-derived fragments and histone lactylation in regulating ferroptosis and offering potential new targets for MASH treatment[54] (Figure 2).

HISTONE LACTYLATION AND HEPATIC INFLAMMATION AND FIBROSIS IN MASH

Cellular plasticity in macrophages and HSCs in response to metabolic stress in MASH results in the phenotypic transformation of liver macrophages to a pro-inflammatory state and HSCs to a fibroblast-like pro-fibrotic state. This study investigated the role of hexokinase 2 (HK2) in liver macrophage function and its contribution to MASLD progression. A recent study by Li et al[55] identified an HK2/glycolysis/H3K18 La positive feedback loop that exacerbated metabolic stress and inflammation in liver macrophages. They showed that HK2, which is upregulated in liver macrophages of MASLD patients and mouse models, causes liver macrophages to produce lactate. Concurrently, increased lactate production leads to increased histone lactylation on H3K18 at the promoters of glycolytic and inflammatory genes, leading to macrophage activation and MASH progression[55]. This study demonstrates that HK2-mediated metabolic rewiring and the resulting inflammatory burden in liver macrophages play a crucial role in MASLD progression[55] (Figure 2). The HK2/glycolysis/H3K18 La positive feedback loop regulates the histone lactylation landscape and M1 polarization of liver macrophages, revealing a previously unrecognized amplification-type pathogenic mechanism in MASLD. Inhibition of the transcription factor hypoxia inducible factor-1 α, associated with glycolytic gene regulation, significantly disrupts this deleterious cycle[55]. These findings suggest that targeting this amplified pathogenic loop may offer a promising therapeutic strategy for MASH, and provide insights into the complex interplay between metabolic reprogramming and epigenetic remodeling in liver macrophages during MASH progression. Similar to its role in inducing macrophage plasticity, HK2 and histone lactylation have also been implicated in HSC activation and liver fibrosis[56]. This study found that HK2 expression in activated HSCs led to increased lactate production and histone lactylation, particularly H3K18 La[56]. This histone modification is enriched in the promoters of genes induced during HSC activation. Genetic deletion or pharmacological inhibition of HK2 reduces H3K18 La levels and inhibits HSC activation, which can be rescued by exogenous lactate supplementation[56]. The study also revealed competition between histone lactylation and acetylation, with class I HDAC inhibitors increasing acetylation of H3K18 and decreasing H3K18 La[56]. In vivo experiments using HSC-specific and systemic HK2 deletion in mice demonstrated reduced liver fibrosis in both carbon tetrachloride-induced and bile duct ligation models. However, specific diet-induced MASH models were not used in this study[56]. Thus, it was concluded that HK2-mediated lactate production and subsequent histone lactylation play a critical role in HSC activation and liver fibrosis, suggesting that HK2 is a potential therapeutic target for liver fibrosis treatment. Another study showed that insulin-like growth factor 2 messenger RNA binding protein 2, an N6-methyladenosine-binding protein expressed in HSCs, plays a crucial role in modulating glycolysis by stabilizing the messenger RNA of aldolase, fructose-bisphosphate A, a key glycolytic enzyme[57]. Increased aldolase, fructose-bisphosphate A augments lactate production, resulting in histone lactylation and activation of profibrotic genes, leading to HSC activation in liver fibrosis[57]. Additionally, H3K18 La on the sex-determining region Y-type high-mobility group box protein 9 promoter has been associated with increased liver fibrosis in animals and HSCs stimulated with transforming growth factor-beta[58]. Collectively, these findings suggest a potential link between metabolic alterations and epigenetic regulation in the context of liver fibrosis, and suggest that inhibition of histone lactylation is a possible therapeutic strategy for MASH (Figure 2).

HISTONE LACTYLATION IN ASH

Excessive alcohol consumption significantly affects the lactate levels in the body. Clinical studies have demonstrated that alcohol misuse can impair lactate clearance, primarily because alcohol metabolism depletes nicotinamide adenine dinucleotides, which are crucial for lactate clearance. This can result in lactate accumulation, contributing to conditions such as metformin-associated lactic acidosis in patients with compromised renal function[59]. Research on human alcohol consumption has shown that ethanol intake elevates lactate levels in the body. The alcohol-induced increase in plasma lactate levels can be modulated by ADH activity, and interventions that inhibit this enzyme, such as 4-methylpyrazole, have been found to mitigate the alcohol-induced increase in lactate levels[60]. In individuals with type 2 diabetes, acute alcohol consumption was observed to increase the lactate area under the curve, indicating elevated lactate levels during alcohol intake[61]. This study revealed that while alcohol improved insulin sensitivity, it also resulted in higher lactate levels in both diabetic and non-diabetic subjects[61]. These findings suggest that excessive alcohol consumption is associated with elevated lactate levels owing to metabolic processes involving alcohol breakdown and inhibitory effects on lactate clearance. These findings strongly suggest that histone lactylation may be altered in ASH, similar to that observed in MASH. While specific studies directly linking alcohol consumption to histone lactylation have not been identified, the general understanding of the impact of alcohol on metabolic processes and histone modifications suggests a likely influence on histone lactylation in the pathogenesis of ASH.

PHARMACOLOGICAL MODULATION OF HISTONE LACTYLATION AS A NOVEL THERAPY FOR MASH/ASH

The modulation of histone lactylation can be achieved through several mechanisms: (1) Inhibitors of intracellular lactate production: Reduction of lactate production and lactylation can be accomplished by targeting glycolytic enzymes. For instance, 2-deoxy-d-glucose acts as an inhibitor of hexokinase, thereby decreasing lactate production and histone lactylation in hepatocellular carcinoma[62]. Similarly, LDHA inhibitors, such as oxamate[63] and GSK2837808A[64], as well as natural products such as salvianolic acid B[65], royal jelly acid[66], and demethylzeylasteral[67], have demonstrated efficacy in reducing lactate production and histone lactylation. Dichloroacetic acid, known to target pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase, results in a reduction in intracellular lactate and subsequent H3K18 La levels, thereby decelerating the progression of liver fibrosis[68]; (2) Inhibition of lactate transport via monocarboxylate transporters is a potential therapeutic strategy, wherein monocarboxylate transporter inhibitors effectively block lactate accumulation and provide protection against hepatic steatosis[11,69]; and (3) Modulators of lactylation enzymes, including p300 and, in some cases, Class I HDAC inhibitors, such as apicidin and MS-275, which upregulate acetylation of H3K18, compete with H3K18 La, resulting in the downregulation of H3K18 La-dependent pro-fibrotic gene expression induced by HSC activation[56]. Therefore, pharmacological strategies targeting glycolytic enzymes, lactate transporters, and lactylation-associated enzymes offer diverse intervention pathways to manage the progression of liver disease in MASH and ASH patients. However, optimizing the specificity and minimizing the off-target effects of these compounds within the complex hepatic microenvironment remains a significant challenge before they can be translated into therapies with clinical applications.

FUTURE CLINICAL UTILITY OF HISTONE LACTYLATION IN DISEASE DIAGNOSIS AND THERAPEUTICS IN MASH/ASH

While the specific clinical implications of histone lactylation in MASH and ASH require further direct investigation, evidence from other studies[50,70] suggests its considerable potential as a diagnostic and therapeutic target for metabolic liver diseases. Previous research has demonstrated that the detection of histone modifications in the bloodstream can serve as a surrogate marker for disease progression. Consequently, the identification of histone lactylation in patient blood samples could function as a biomarker for systemic metabolic alterations and cellular activity, particularly when analyzed in conjunction with serum lactate levels in patients with MASH and ASH. Although, lactylation dynamics is not fully understood during MASH/ASH pathogenesis, the application of inhibitors targeting lactate uptake in hepatic cells may represent a novel therapeutic strategy for individuals with MASH and ASH[71,72]. Therefore, future clinical studies should prioritize evaluating the potential prognostic and therapeutic roles of histone lactylation in MASH/ASH.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, histone modifications, particularly recently identified histone lactylation, play pivotal roles in the pathogenesis of chronic liver diseases, including MASH and ASH. These epigenetic alterations, which are influenced by intracellular lactate levels, affect gene expression patterns that contribute to disease pathogenesis. Lactylation of specific histone residues, such as H3K18, has been associated with increased lipogenesis, hepatocyte injury, and activation of pro-inflammatory and pro-fibrotic pathways in liver macrophages and HSCs in MASH. Although direct evidence linking alcohol consumption to histone lactylation in ASH is limited, the established effects of alcohol on lactate metabolism suggest a potential role of this modification in ASH pathogenesis. Moreover, pharmacological modulation of histone lactylation, by targeting lactate production, transport, or lactylation enzymes, offers a promising avenue for therapeutic intervention in both MASH and ASH. However, further research is required to fully elucidate the complex interplay between these epigenetic modifications and liver disease progression as well as to develop targeted therapies with minimal off-target effects.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: India

Peer-review report’s classification

Scientific Quality: Grade B, Grade B, Grade D

Novelty: Grade C, Grade C, Grade D

Creativity or Innovation: Grade B, Grade C, Grade D

Scientific Significance: Grade B, Grade C, Grade D

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P-Reviewer: Fan XC, MD, PharmD, PhD, Post Doctoral Researcher, Research Assistant Professor, China; Li WJ, MD, China S-Editor: Hu XY L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Xu J