Published online Dec 27, 2025. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v17.i12.110993

Revised: July 22, 2025

Accepted: November 11, 2025

Published online: December 27, 2025

Processing time: 189 Days and 3.6 Hours

About 35%-50% of patients with hepatocellular cancer (HCC) present with portal venous tumor thrombosis (PVTT). Stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) offers a promising approach for locoregional treatment in patients with HCC with PVTT. This study aimed to report the clinical characteristics and early outcomes of patients with unresectable HCC and PVTT treated with SBRT.

To report the clinical characteristics and early outcomes of patients with unre

This retrospective, single-institution study included adult HCC patients with PVTT treated between March 2020 and December 2023. Eligibility criteria included Child-Pugh A-B liver function, serum bilirubin < 3 mg/dL, Eastern Co-operative Oncology Group performance status 0-2, a normal liver volume > 700 cc, and a tumor-lumen distance > 5 mm. SBRT dose and fractionation were determined based on tumor volume and organ-at-risk constraints. Baseline clinical and dosimetric parameters were recorded. Survival analysis was performed using Kaplan-Meier curves, response was assessed at 3 months post-SBRT using the Revised Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors 1.1 criteria, and toxicity was graded per Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events 4.0.

Thirty patients (median age: 65 years, 90% male) were included. Sixteen (53.3%) were Child-Pugh A, and fourteen (46.6%) were Child-Pugh B. Sixty percent had VP4 disease. SBRT doses ranged from 30-50 Gy in 5-6 fractions. The median tumor diameter was 6.1 cm, and the median follow-up was 15 months. The overall response rate was 83.3%, with a median overall survival of 13 months and progression-free survival of 10.2 months. No grade 4 toxi

SBRT has the potential to be an effective modality for locoregional control in patients with unresectable HCC with PVTT.

Core Tip: Portal vein tumor thrombosis is a common and challenging presentation in hepatocellular carcinoma, significantly limiting treatment options. This retrospective study highlights the safety and efficacy of stereotactic body radiation therapy as a locoregional treatment in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma and portal vein tumor thrombosis. With an encouraging response rate of 83.3% and a median overall survival of 13 months, stereotactic body radiation therapy de

- Citation: Khosla D, Gade VKV, Kapoor R, Singh G, Singh R, Taneja S, Premkumar M, Kalra N, De A, Bhujade H, Verma N, Duseja A, Gupta R. Stereotactic body radiation therapy in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma and portal vein tumor thrombosis. World J Hepatol 2025; 17(12): 110993

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v17/i12/110993.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v17.i12.110993

Liver cancer is the eleventh most common cancer in India, accounting for 2.7% of all cases (38700 new cases), and ranks eighth in terms of mortality[1]. Hepatocellular cancer (HCC) represents more than 90% of primary liver cancers and is a major global health problem. Epidemiological information regarding HCC is scant in India, but studies show viral hepatitis, aflatoxin exposure, and alcoholic cirrhosis as major causes[2,3]. The majority of cases involve underlying ch

Patients with advanced HCC who exhibit macrovascular invasion, extrahepatic metastasis, or impaired performance status are classified as BCLC-C HCC. Typically, these patients are managed with systemic therapy. According to the up

About 35%-50% of HCC patients present with PVTT. The presence of PVTT is a negative predictive factor with patients having an increased risk of systemic thromboembolism and metastasis[10]. PVTT is also a contraindication for liver transplantation. The treatment options for patients with PVTT include locoregional therapies, which include transarterial radioembolization, SBRT, and proton beam therapy, in addition to systemic therapy. A study of 24 patients from South Korea assessed the efficacy of combining SBRT and TACE for HCC with PVTT. SBRT was administered at a dose of 45 Gy in 3 fractions, targeting the thrombus with dose modification required in 29.2%, followed by TACE in 66.7% of patients. This treatment approach achieved a median survival of 20.8 months[11]. Shui et al[12] investigated the use of SBRT as the initial treatment in 70 patients with extensive PVTT. The median survival was 10 months, with SBRT demonstrating sig

This study presents a comprehensive evaluation of early clinical outcomes in patients with unresectable HCC complicated by PVTT who were treated with SBRT at a single institution. The analysis includes detailed information on treatment responses, side effects, and overall impact on disease progression, contributing valuable data to the ongoing assessment of SBRT in the management of advanced HCC with PVTT.

This retrospective single-institution study, conducted from March 2020 to December 2023, aimed to report the clinical characteristics and early outcomes of patients with unresectable HCC and PVTT treated with SBRT. This study was approved by the Institute Ethics Committee (No. IEC-INT/2025/Study-2980). Adult patients of unresectable HCC with PVTT were included in the study. Patients who received prior radiotherapy or had a second malignancy were excluded from the study. Japanese VP classification was used for the thrombus which distinguished four grades of PVTT and three grades of hepatic vein tumor involvement [VP1: Presence of a tumor thrombus distal to the second-order branches of portal vein (but not involving them directly); VP2: Invasion of the second-order branches of portal vein; VP3: Presence of the thrombus in the first-order branches; VP4: Tumor thrombus in the main trunk of the portal vein and/or a portal vein branch contralateral to the primarily involved lobe; VV1: Tumor thrombus in a branch of the hepatic vein; VV2: Tumor thrombus in the main trunk of the hepatic veins; VV3: Thrombus reaching the right atrium][14]. Patients were considered for SBRT if they met the following eligibility criteria: Child Pugh score A-B, serum bilirubin levels less than 3 mg/dL, Eastern Co-operative Oncology Group performance status of 0 to 2, normal liver volume of more than 700 cc, and dis

Patients underwent a four dimension and multiphase computed tomography (CT) (arterial phase, portal venous and delayed phase), using custom immobilization on a patient-to-patient basis (vacuum cushion immobilization, patient positioning boards, knee cushions, and abdominal compression). The primary tumor and/or the tumor vascular thrombus were included in the gross tumor volume (GTV). The GTV was delineated on contrast-enhanced arterial and portal venous phases, as well as on minimum intensity projection (minIP) of four dimension-CT, to generate the Internal Target Volume. A 0.5 cm margin was given to the GTV to generate the planning target volume (PTV). For all patients, image-guided radiotherapy using cone beam CT for every fraction was mandatorily performed.

The patients were planned with volumetric modulated arc therapy on the Monaco treatment planning system from Elekta (version 5.11). Treatment was delivered in 5-6 fractions with a dose ranging from 30-50 Gy. The dose to the tumor and PVTT was planned respecting the tolerance of the liver and other organs at risk (OARs). The number of fractions was chosen based on the volume of normal tissues irradiated, considering the dose constraints for OARs such as stomach, duodenum, small and large bowel, and liver. The prescription dose was intended to cover the PTV, and the minimum permitted dose to 99% of the PTV was 90% of the prescription dose. The maximum permitted dose within PTV was 120% of the prescription dose. Sub-volumes close to critical OARs were allowed to receive a lower dose to avoid toxicities. OARs contoured included the remaining liver (liver minus GTV), esophagus, stomach, duodenum, bowel, spinal cord, kidneys, heart, chest wall, skin, and overlying ribs[15]. Patients were monitored with blood tests, which included hemogram, liver function tests, while on treatment to monitor acute toxicity. Two and four weeks after SBRT, blood tests including hemogram, renal function tests, liver function tests, coagulogram, alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), and protein induced by vitamin K absence-II (PIVKA-II) were performed.

Treatment responses were evaluated using the international criteria proposed in the Revised Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors Guideline version 1.1[16] from a panel of an experienced radiologist and radiation oncologist. Response assessment included the response of the tumor thrombus, physical examination, and blood tests. Acute Toxicity was evaluated using Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 5[17]. At 3 months post-SBRT, patients were assessed with laboratory and radiological examination. Triple phase CT or dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging with diffusion weighted imaging was performed for response assessment. Imaging and tumor markers were performed 3 months or as clinically indicated. If HCC recurred, appropriate treatment was provided based on the clinical guidelines after multidisciplinary tumor board discussion.

Continuous variables were reported as median with the corresponding range (minimum and maximum), and categorical variables were presented as absolute and relative frequencies unless stated otherwise. OS was calculated as time from the start of treatment until death from any cause, with censoring at the date last seen alive. Progression-free survival (PFS) was calculated as time from the start of treatment until death or documentation of progression. PFS times were censored at the date patients were last seen alive without disease progression. OS and PFS were estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method. Mean serum AFP levels at baseline were compared with AFP levels obtained 3 months after SBRT with the help of the Paired t-test. Univariate analysis for factors affecting the OS was done with the help of log rank test. The Cox proportional hazard method was used for multivariate analysis of factors influencing the OS.

The median age of the study group was 65 years. While 90% of the study group was male, 10% was female. About a third of patients had a history of viral hepatitis. While 5 patients had a history of hepatitis B, another 5 patients had a history of hepatitis C. Sixteen patients belonged to Child-Pugh class A, and fourteen patients belonged to Child-Pugh class B. Twenty-two patients (73.3%) had a single liver lesion, whereas six patients (20%) had two liver lesions, with one patient each (3.3%) having three and four lesions, respectively. Based on the Japanese classification of venous thrombosis in HCC, one patient (3.3%) belonged to VP2, whereas eight patients (26.7%) belonged to VP3, eighteen patients (60%) belonged to VP4, one patient (3.3%) belonged to VV2, and two patients (6.7%) belonged to VV3. Table 1 presents a summary of the patients’ clinical characteristics. While seven patients (23.3%) underwent prior TACE, five patients (16.7%) underwent prior transarterial radioembolization, two patients (6.7%) underwent prior RFA, and one patient (3.3%) underwent prior cryoablation. Six patients (20%) were on sorafenib at the time of SBRT, while sixteen patients (53.3%) were on lenvatinib, and one patient (3.3%) was on atezolizumab and bevacizumab (Table 2).

| Patient characteristics | Value (n = 30) |

| Age (median in years) (range) | 65 (38-83) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 27 (90) |

| Female | 3 (10) |

| Viral serology | |

| Hepatitis B positive | 5 (16.7) |

| Hepatitis C positive | 5 (16.7) |

| Child-Pugh class at diagnosis | |

| Child-Pugh class A | 16 (53.3) |

| Child-Pugh class B | 14 (46.7) |

| ALBI score (median) (range) | -2.34 (-1.11-3.43) |

| ALBI grade | |

| Grade 1 | 7 (23.3) |

| Grade 2 | 21 (70) |

| Grade 3 | 2 (6.7) |

| Number of liver lesions | |

| One | 22 (73.3) |

| Two | 6 (20) |

| Three | 1 (3.3) |

| Four | 1 (3.3) |

| Thrombus classification (Japanese) | |

| VP2 | 1 (3.3) |

| VP3 | 8 (26.7) |

| VP4 | 18 (60) |

| VV2 | 1 (3.3) |

| VV3 | 2 (6.7) |

| Prior focal treatment | |

| TACE | 7 (23.3) |

| TARE | 5 (16.7) |

| RFA | 2 (6.7) |

| Cryoablation | 1 (3.3) |

| Prior systemic therapy | |

| Sorafenib | 6 (20) |

| Lenvatinib | 16 (53.3) |

| Atezolizumab + bevacizumab | 1 (3.3) |

| Baseline AST (IU/mL) (mean ± SD) | 46 ± 12 |

| Baseline ALT (IU/mL) (mean ± SD) | 49 ± 15 |

| Treatment characteristics | Value (n = 30) | |

| Dose fractionation | ||

| 30 Gy/6 # | 1(3.3) | |

| 30 Gy/5 # | 4 (13.3) | |

| 50 Gy/5 # | 5 (16.7) | |

| 40 Gy/5 # | 6 (20) | |

| 48 Gy/4 # | 1 (13.3) | |

| 35 Gy/5 # | 6 (20) | |

| 33 Gy/6 # | 1(3.3) | |

| 36 Gy/3 # | 3 (10) | |

| 48 Gy/6 # | 1(3.3) | |

| 45 Gy/5 # | 2 (6.7) | |

| Treatment volumes | ||

| GTV diameter (median cm) (range) | 6.1 (2.54-10.63) | |

| GTV volume (median cc) (range) | 49.05 (8.6-308) | |

| PTV diameter (median cm) (range) | 7.9 (3.7-20.54) | |

| PTV volume (median cc) (range) | 165.22 (27.3-453.6) | |

| Serum AFP (prior to SBRT) (mean ± SD) (ng/mL) | 7181.14 ± 17948 | P value = -0.049 |

| Serum AFP (3 months after SBRT) (mean ± SD) (ng/mL) | 2183.44 ± 7323 | |

Various dose fractionations were used, ranging from 30 to 50 Gy in 5-6 fractions, with 16.7% of patients receiving 50 Gy/

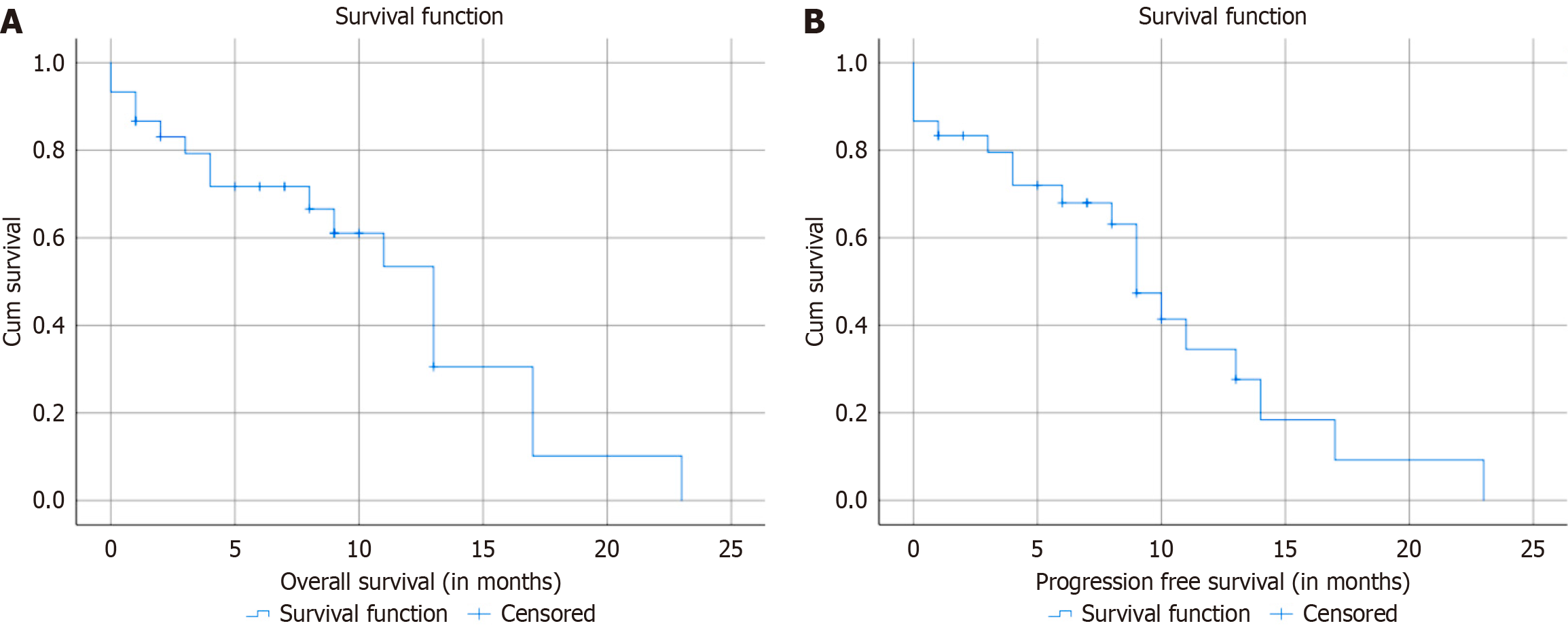

The median follow-up duration was 15 months (range 5-23 months). Overall response rate was 83.3%. The median OS of the group was 13 months. The 6-month and 1-year OS were 71% and 53%, respectively. The median PFS was 10.2 months. The 6-month and 1-year PFS were 72% and 33%, respectively (Table 3). Figure 1 present Kaplan-Meier survival curves for OS and PFS, respectively. Survival factors analysis showed no significant differences between Child-Pugh class A and B at baseline (13 months vs 10 months, P = 0.106). On analyzing the Child-Pugh score 2 weeks after SBRT, it was seen that eighteen patients (60%) had no change from baseline. While the Child-Pugh score improved in 10 patients (33.3%), it worsened by one point in two patients (6.7%), who got better at one month after SBRT. Albumin-Bilirubin score at baseline did not significantly influence survival, with median survival times of 17 months for grade 1, 11 months for grade 2, and 1 month for grade 3 (P = 0.309) (Table 4). Table 5 shows that none of the factors analyzed, including age, baseline AFP, bilirubin, Child-Pugh score, Albumin-Bilirubin score, GTV diameter and volume, PTV diameter and volume, significantly impacted survival outcomes. All hazard ratios were close to 1, and P-values were above the common threshold for significance (0.05), indicating no strong associations between these factors and survival.

| Time | OS | PFS |

| Median | 13 months | 10.2 months |

| 6-month | 71 | 72 |

| 1-year | 53 | 33 |

| Factor | Comparison (median overall survival) | Log-rank χ2 (P value) |

| Child-Pugh class at baseline; A vs B | 13 months vs 10 months | 2.6 (0.106) |

| CP class 2 weeks post SBRT; A vs B vs C | 17 months vs 13 months vs 3 months | 5.3 (0.069) |

| ALBI grade at baseline; Grade 1 vs Grade 2 vs Grade 3 | 17 months vs 11 months vs 1 month | 2.35 (0.309) |

| Factor | Hazard ratio (95%CI) | P value |

| Age | 0.998 (0.891-1.11) | 0.967 |

| Baseline AFP | 1.000 (0.96-1.43) | 0.265 |

| Baseline bilirubin | 0.897 (0.32-2.49) | 0.834 |

| Child-Pugh score at baseline | 0.594 (0.22-1.58) | 0.296 |

| ALBI score at baseline | 1.217 (0.26-5.6) | 0.801 |

| GTV diameter | 0.77 (0.40-1.47) | 0.435 |

| GTV volume | 0.992 (0.956-1.02) | 0.992 |

| PTV diameter | 0.996 (0.663-1.49) | 0.985 |

| PTV volume | 1.080 (0.97-1.19) | 0.446 |

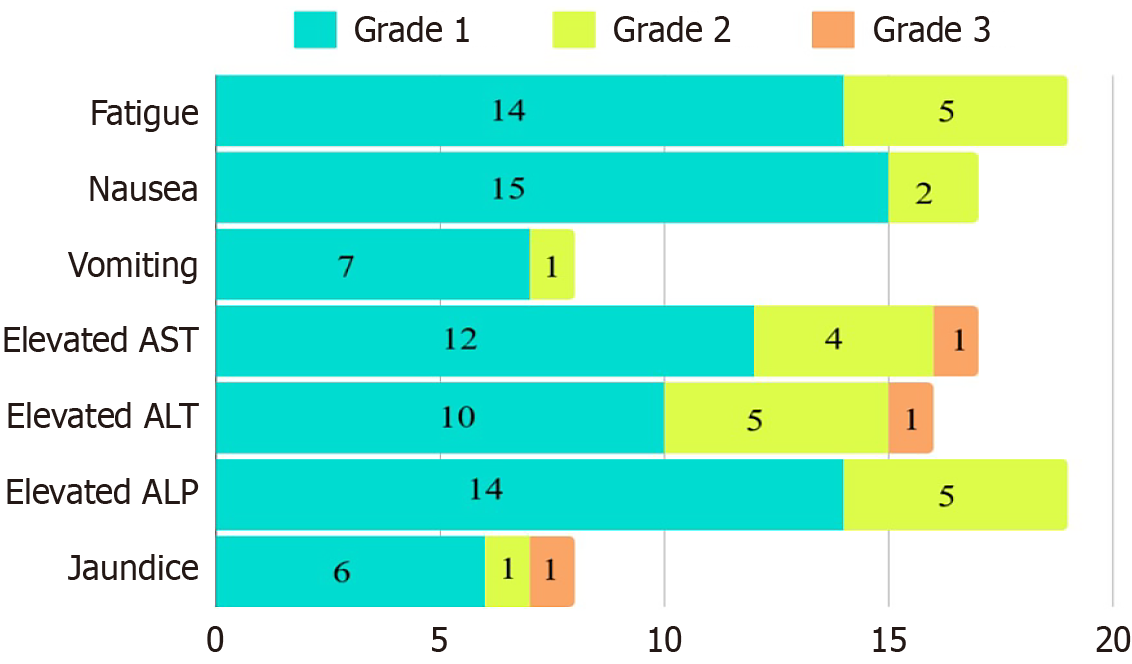

There were no grade 4 adverse effects. One patient had grade 3 deterioration of liver function with transaminitis and jaundice within 2 weeks of SBRT. This subsided over 10 days with conservative management. Fourteen patients (46 %) reported mild fatigue, and five patients (16.6%) reported moderate fatigue after SBRT. Fifteen patients (50%) reported mild nausea, and two patients (6.7%) reported moderate nausea after SBRT. About 50%-55% of patients reported varying degrees of transaminitis. Seven patients (23.3%) had grade 1 vomiting that was managed with oral antiemetics. Six patients (20%) had grade 1 elevation, and 1 patient (3.3%) had grade 2 elevation of serum bilirubin (Figure 2).

One of the major challenges in managing HCC is the common occurrence of PVTT, which complicates treatment choices and negatively impacts patient prognosis. This retrospective study aimed to assess the clinical characteristics and early outcomes of patients with unresectable HCC and PVTT treated with SBRT. The cohort consisted of 30 patients, predominantly male (90%), with a median age of 65 years, reflective of the typical demographic affected by HCC. The distribution of Child-Pugh class A (53.3%) and class B (46.6%) indicates a balance between relatively well-preserved liver function and those with more compromised hepatic reserve. This distribution is crucial, as the Child-Pugh score significantly influences treatment decisions and outcomes. The inclusion criteria ensured that patients had manageable liver function and adequate performance status, optimizing the potential for therapeutic benefit from SBRT.

Though HCC was initially considered a radioresistant tumor, recent studies have shown that it is as radiosensitive as other epithelial tumors[16]. The primary challenge in delivering external beam radiotherapy to HCC lies in respecting the radiation tolerance of the surrounding normal liver tissue[18]. SBRT addresses this issue by delivering a high biological dose of radiation to a precisely defined extracranial target with ablative intent. This approach allows for the administration of high doses per fraction to the tumor while effectively sparing normal hepatic parenchyma. Over the past de

The presence of PVTT makes HCC unresectable and transplant ineligible. The objective of locoregional therapies, including SBRT, is to improve the patency of the portal venous system by dissolving the tumor thrombus, thereby im

Kang et al[21] reported a large series of 101 patients of HCC with PVTT that were treated with SBRT and TACE. SBRT was delivered by static intensity-modulated radiation therapy with a dose ranging from 21-60 Gy in 6 fractions. The median OS ranged from 12-17 months with a response rate of 70.3%[21]. Xi et al[22] reported a retrospective series of 41 patients of HCC with PVTT in whom SBRT was delivered by volumetric modulated arc therapy with a dose ranging from 30-48 Gy in 6 fractions. They reported a response rate of 75.6% and a median OS of 13 months[22]. Choi et al[11] reported a series of 24 patients of HCC with PVTT that were treated with SBRT by Cyberknife. The dose prescription ranged from 39-45 Gy in 3-4 fractions. The authors reported a response rate of 54.2% and a median OS of 20.8 months[11].

About half of the patients received prior treatment in the form of TACE, transarterial radioembolization, RFA, or cryoablation before undergoing SBRT. The combination of TACE, SBRT, and TKIs in unresectable HCC with PVTT is being increasingly explored in prospective studies. In a single-center prospective randomized trial conducted by Duan et al[13], patients with HCC and PVT were randomized to either SBRT + TACE + TKIs or the TACE + TKI group. They found that the addition of SBRT to TACE and TKI therapy improved PFS (9.75 months vs 4.89 months) and

Unlike many previous reports that included patients with varying degrees of PVTT, our cohort predominantly com

In conclusion, SBRT represents a viable and effective treatment modality for patients with unresectable HCC and PVTT. Our findings indicate that SBRT can achieve an overall response rate of 83.3%, with a median OS of 13 months. The treatment was generally well-tolerated, with no grade 4 toxicities reported. These results highlight SBRT as a promising locoregional therapy for patients with this challenging condition. The results emphasize the need for further integration of SBRT into multidisciplinary treatment strategies for HCC. Future research, including prospective trials, is warranted to refine patient selection criteria, compare SBRT with systemic therapy, and explore combination treatment approaches.

| 1. | Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024;74:229-263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5690] [Cited by in RCA: 12729] [Article Influence: 6364.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (8)] |

| 2. | Kar P. Risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma in India. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2014;4:S34-S42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Tohra S, Duseja A, Taneja S, Kalra N, Gorsi U, Behera A, Kaman L, Dahiya D, Sahu S, Sharma B, Singh V, Dhiman RK, Chawla Y. Experience With Changing Etiology and Nontransplant Curative Treatment Modalities for Hepatocellular Carcinoma in a Real-Life Setting-A Retrospective Descriptive Analysis. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2021;11:682-690. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Llovet JM, Fuster J, Bruix J; Barcelona-Clínic Liver Cancer Group. The Barcelona approach: diagnosis, staging, and treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Transpl. 2004;10:S115-S120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 500] [Cited by in RCA: 516] [Article Influence: 23.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Llovet JM, Schwartz M, Mazzaferro V. Resection and liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin Liver Dis. 2005;25:181-200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 662] [Cited by in RCA: 669] [Article Influence: 31.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Rhim H, Lim HK. Radiofrequency ablation of hepatocellular carcinoma: pros and cons. Gut Liver. 2010;4 Suppl 1:S113-S118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Lencioni R, Petruzzi P, Crocetti L. Chemoembolization of hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2013;30:3-11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in RCA: 155] [Article Influence: 12.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Reig M, Forner A, Rimola J, Ferrer-Fàbrega J, Burrel M, Garcia-Criado Á, Kelley RK, Galle PR, Mazzaferro V, Salem R, Sangro B, Singal AG, Vogel A, Fuster J, Ayuso C, Bruix J. BCLC strategy for prognosis prediction and treatment recommendation: The 2022 update. J Hepatol. 2022;76:681-693. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1904] [Cited by in RCA: 3134] [Article Influence: 783.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (61)] |

| 9. | Kumar A, Acharya SK, Singh SP, Duseja A, Madan K, Shukla A, Arora A, Anand AC, Bahl A, Soin AS, Sirohi B, Dutta D, Jothimani D, Panda D, Saini G, Varghese J, Kumar K, Premkumar M, Panigrahi MK, Wadhawan M, Sahu MK, Rela M, Kalra N, Rao PN, Puri P, Bhangui P, Kar P, Shah SR, Baijal SS, Shalimar, Paul SB, Gamanagatti S, Gupta S, Taneja S, Saraswat VA, Chawla YK. 2023 Update of Indian National Association for Study of the Liver Consensus on Management of Intermediate and Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma: The Puri III Recommendations. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2024;14:101269. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Manzano-Robleda Mdel C, Barranco-Fragoso B, Uribe M, Méndez-Sánchez N. Portal vein thrombosis: what is new? Ann Hepatol. 2015;14:20-27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Choi HS, Kang KM, Jeong BK, Jeong H, Lee YH, Ha IB, Song JH. Effectiveness of stereotactic body radiotherapy for portal vein tumor thrombosis in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma and underlying chronic liver disease. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2021;17:209-215. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Shui Y, Yu W, Ren X, Guo Y, Xu J, Ma T, Zhang B, Wu J, Li Q, Hu Q, Shen L, Bai X, Liang T, Wei Q. Stereotactic body radiotherapy based treatment for hepatocellular carcinoma with extensive portal vein tumor thrombosis. Radiat Oncol. 2018;13:188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Duan J, Zhou J, Liu C, Jiang H, Zhou J, Xie K, Wu H, Zeng Y, Wang X. Stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) combined with transcatheter arterial chemoembolization (TACE) and tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) versus TACE and TKIs alone for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (uHCC) with portal vein tumor thrombus (PVTT): A randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2024;42:4102-4102. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 14. | Ikai I, Itai Y, Okita K, Omata M, Kojiro M, Kobayashi K, Nakanuma Y, Futagawa S, Makuuchi M, Yamaoka Y. Report of the 15th follow-up survey of primary liver cancer. Hepatol Res. 2004;28:21-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Dawson LA, Winter KA, Knox JJ, Zhu AX, Krishnan S, Guha C, Kachnic LA, Gillin MT, Hong TS, Craig TD, Williams TM, Hosni A, Chen E, Noonan AM, Koay EJ, Sinha R, Lock MI, Ohri N, Dorth JA, Delouya G, Swaminath A, Moughan J, Crane CH. Stereotactic Body Radiotherapy vs Sorafenib Alone in Hepatocellular Carcinoma: The NRG Oncology/RTOG 1112 Phase 3 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2025;11:136-144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 42.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, Schwartz LH, Sargent D, Ford R, Dancey J, Arbuck S, Gwyther S, Mooney M, Rubinstein L, Shankar L, Dodd L, Kaplan R, Lacombe D, Verweij J. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:228-247. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15860] [Cited by in RCA: 22835] [Article Influence: 1343.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 17. | United States Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute. Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) Version 5.0. November 27, 2017. [cited 27 November 2021]. Available from: https://dctd.cancer.gov/research/ctep-trials/for-sites/adverse-events/ctcae-v5-8x11.pdf. |

| 18. | Benson R, Madan R, Kilambi R, Chander S. Radiation induced liver disease: A clinical update. J Egypt Natl Canc Inst. 2016;28:7-11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Chen W, Chiang CL, Dawson LA. Efficacy and safety of radiotherapy for primary liver cancer. Chin Clin Oncol. 2021;10:9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Apisarnthanarax S, Barry A, Cao M, Czito B, DeMatteo R, Drinane M, Hallemeier CL, Koay EJ, Lasley F, Meyer J, Owen D, Pursley J, Schaub SK, Smith G, Venepalli NK, Zibari G, Cardenes H. External Beam Radiation Therapy for Primary Liver Cancers: An ASTRO Clinical Practice Guideline. Pract Radiat Oncol. 2022;12:28-51. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 150] [Article Influence: 37.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Kang J, Nie Q, DU R, Zhang L, Zhang J, Li Q, Li J, Qi W. Stereotactic body radiotherapy combined with transarterial chemoembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma with portal vein tumor thrombosis. Mol Clin Oncol. 2014;2:43-50. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Xi M, Zhang L, Zhao L, Li QQ, Guo SP, Feng ZZ, Deng XW, Huang XY, Liu MZ. Effectiveness of stereotactic body radiotherapy for hepatocellular carcinoma with portal vein and/or inferior vena cava tumor thrombosis. PLoS One. 2013;8:e63864. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/