Published online Nov 27, 2025. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v17.i11.110080

Revised: July 1, 2025

Accepted: October 10, 2025

Published online: November 27, 2025

Processing time: 182 Days and 20.5 Hours

Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) requires ac

Core Tip: Current biomarkers (fibrosis-4, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease fibrosis score) provide accessible first-line screening for metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) fibrosis but require age/obesity-adjusted thresholds. Patented panels (enhanced liver fibrosis, FibroMeter) enhance precision through metabolic/extracellular matrix markers yet need MASLD-specific validation. Emerging biomarkers (propeptide of type 3 collagen, Mac-2 binding protein glycosylation isomer, epigenetic regulators like proliferator-activated receptor-γ methylation, angiopoietin-like proteins such as angiopoietin-like protein a family of eight glycoproteins) show monitoring potential but need validation. No single biomarker replaces biopsy. Combining existing tools with novel multi-omics approaches and MASLD-specific diagnostic frameworks is critical for improving clinical outcomes in this epidemic.

- Citation: Zhao YH, Leng SS, Wang Y, Kui FZ, Gan W. Non-invasive blood biomarkers for assessment of liver fibrosis in metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. World J Hepatol 2025; 17(11): 110080

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v17/i11/110080.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v17.i11.110080

Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), previously known as non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), has emerged as one of the most prevalent chronic liver diseases globally, with an estimated prevalence exceeding 30% of the general population[1-3]. This alarming rise is closely associated with the increasing incidence of obesity and type 2 diabetes (T2DM), key components of the metabolic syndrome[4]. The global burden of MASLD is further exacerbated by its significant association with severe liver-related outcomes, including cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma, and liver failure[5]. Liver fibrosis is a pivotal factor influencing the prognosis of MASLD[6]. The extent of fibrosis correlates strongly with disease severity, the incidence of complications, and overall patient survival[7]. Early identification and staging of liver fibrosis are therefore crucial for the clinical management of MASLD. Timely inter

Currently, liver biopsy is considered the “gold standard” for assessing liver fibrosis[9]. However, this invasive procedure is associated with several limitations, including procedural risks, sampling variability, and significant costs[10,11]. Moreover, the invasiveness and potential complications of liver biopsy render it unsuitable for widespread ap

According to MASLD clinical-pathological staging, fibrosis is classified as none/mild fibrosis (F0-1), significant fibrosis (≥ F2), advanced fibrosis (≥ F3), and cirrhosis (F4)[13]. Although the ultimate goal is for non-invasive fibrosis tests to provide information comparable to liver biopsy, none of these tests currently achieves equivalent accuracy to liver biopsy in assessing hepatic fibrosis when used alone. MASLD affects a substantial proportion of the general population, but only a minority progress to advanced hepatic fibrosis[14]. Patients with advanced fibrosis face an elevated risk of liver-related complications and mortality[15,16]. However, even in the presence of advanced fibrosis, individuals with MASLD often remain asymptomatic. Their first clinical presentation may coincide with hepatic decompensation, thereby missing opportunities for preventive interventions[17]. Currently, widespread screening for MAFLD in the general population, followed by treatment, is not deemed justified unless further evidence emerges. Therefore, proactive case-finding in high-risk populations is more appropriate. In current clinical practice, ultrasonography is the most common method for diagnosing hepatic steatosis and serves as a primary screening tool to aid in the diagnosis of MASLD. Among patients with T2DM, the prevalence of MASLD is significantly higher, and these individuals are at increased risk of developing steatohepatitis and advanced fibrosis[18,19]. Therefore, patients with metabolic syndrome, particularly those with T2DM, represent a key target population for identifying MASLD and advanced fibrosis. In this context, this can be achieved through simple blood tests and blood-based biomarkers or risk scores.

Blood biomarkers have garnered considerable attention due to their non-invasive nature, ease of acquisition, and cost-effectiveness. These biomarkers offer a practical alternative for large-scale screening and monitoring of liver fibrosis in MASLD[20,21]. By measuring specific proteins, enzymes, and other molecules in the blood, serum biomarkers can provide valuable insights into the presence and severity of liver fibrosis. Their ability to be repeatedly measured and their relatively low cost make them particularly suitable for longitudinal monitoring and risk stratification in clinical practice[22]. Despite the potential of serum biomarkers, no single marker has yet been able to completely replace liver biopsy. The accuracy and reliability of these biomarkers vary, and their performance can be influenced by factors such as age, obesity, and the presence of other metabolic conditions[20]. These tools help exclude advanced fibrosis in affected populations and identify which patients require further risk stratification. Therefore, this review aims to provide a comprehensive evaluation of the current landscape of blood biomarkers for the assessment of liver fibrosis in MASLD. We will discuss the strengths and limitations of existing biomarkers, their clinical applications, and future directions for research and development.

Elevated serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) levels should prompt suspicion of liver injury and warrant further investigation to determine the underlying cause. However, normal serum ALT and AST levels do not exclude underlying liver disease. Patients with MASLD, advanced fibrosis, or cirrhosis may have serum ALT and AST levels within the normal range[23,24]. Therefore, relying solely on elevated liver enzyme levels for risk stratification in MASLD patients is insufficient.

The earliest serum-based biomarker scores to emerge were the AST/ALT ratio and the AST-to-platelet ratio index (APRI)[25,26]. Originally developed and validated for fibrosis staging in patients with chronic hepatitis C, these indices demonstrate moderate accuracy in predicting advanced fibrosis in individuals with MASLD. The AST/ALT ratio achieved an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) of 0.66-0.90 for excluding advanced fibrosis, while APRI showed AUROC values of 0.67-0.83 for advanced fibrosis detection[27-32]. Although APRI demonstrated high diagnostic efficacy for advanced fibrosis in MASLD patients (AUROC: 0.85, specificity 99%), its limited sensitivity (16%) and potential confounding effects from high-risk cohort sampling raise concerns about the generalizability of these findings to broader MASLD populations at risk (Table 1)[33].

| Serum biomaker | Components | Interpretation | Strength of recommendation |

| AST-to-ALT ratio[25,26] | ALT, ALT | Advanced fibrosis > 1.0 | One star |

| AST-to-platelet ratio index[27-33] | AST, platelet count | Rules out fibrosis < 0.5 | Two stars |

| Significant fibrosis >1.0 | |||

| Fibrosis-4[29,33-38] | Age, platelet count, AST, and ALT | Rules out fibrosis < 1.3 | Three stars |

| Advanced fibrosis > 2.671 | |||

| NAFLD fibrosis score[22,28,39-44] | Body mass index, age | Rules out fibrosis < -1.455 | Three stars |

| AST/ALT ratio, platelet count, albumin, hyperglycemia | Advanced fibrosis > 0.675 | ||

| BARD score[28,45-48] | BMI > 28 kg/m2, AST/ALT ratio > 0.8, diabetes | Low risk for advanced fibrosis 0-1 | Two stars |

| High risk for advanced fibrosis 0-1 | |||

| Hepascore fibrosis score[32,49-51] | Age, diabetes, sex, AST, albumin, platelet count, HOMA-IR | Significant fibrosis > 0.50 | Two stars |

| Advanced fibrosis > 0.65 | |||

| N-terminal PRO-C3[52-58] | Reflect true synthesis of type III collagen | Advanced fibrosis >25 U/L | Two stars |

| ADAPT[55] | Age, diabetes status, PRO-C3, and thrombocyte count | Rules out advanced fibrosis ≤ 6.3287 | Three stars |

| Advanced fibrosis > 9.8 | |||

| Mac-2 binding protein glycosylation isomer[59-65] | A glycoprotein expressed by activated hepatic stellate cells | Advanced fibrosis > 0.71 COI | Two stars |

| Enhanced liver fibrosis score[22,28,43,66-68] | PIIINP, HA, TIMP-1 | Rules out fibrosis < 7.7 | Three stars |

| Advanced fibrosis > 9.8 | |||

| FibroTest[22,69,70] | GGT, total bilirubin | Rules out fibrosis < 0.3 | Three stars |

| α2-macroglobulin | |||

| Apolipoprotein A-I | Advanced fibrosis > 0.7 | ||

| Haptoglobin, cholinesterase | |||

| FibroMeter[21,22,71-73] | Age, weight, AST, ALT, platelet count, blood glucose, and ferritin | Rules out fibrosis < 0.31 | Three stars |

| Advanced fibrosis > 0.45 | |||

| Agile 3+ score[74,75] | LSM, platelets, AST, ALT, diabetes status, sex, and age | Rules out fibrosis < 0.351 | Three stars |

| Advanced fibrosis > 0.679 |

The fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) index, incorporating age, platelet count, AST, and ALT, is recommended as a first-line screening tool for fibrosis assessment in general clinical practice[34]. Validation studies defined cutoff values for advanced fibrosis risk stratification as follows: < 1.45 for low risk, > 3.25 for high risk, and values between these thresholds classified as intermediate risk[34]. It exhibits distinct diagnostic performance in MASLD compared to NAFLD. Studies on NAFLD focus optimizing thresholds [e.g., > 3.25 for high specificity 98%, positive predictive value (PPV) 75% vs > 1.3 for sensitivity 85%][29], while MASLD cohorts using the conventional cutoff (> 2.67) show strong specificity (97%-99%) and AUROCs of 0.80-0.82 for advanced fibrosis[33,35]. However, MASLD-specific analyses reveal reduced diagnostic precision, particularly in severely obese patients, where the > 2.67 threshold yielded an AUROC of 0.57; adjusting to > 1.53 marginally improved AUROC to 0.69 but remained inferior to NAFLD benchmarks[36]. Age significantly impacts FIB-4 reliability, with elevated false-positive rates in patients ≥ 65 years, necessitating age-adjusted thresholds (> 2.0 for patients ≥ 65 years old) to improve specificity (Table 1)[37,38]. These disparities highlight the need for MASLD-specific diagnostic frameworks to address metabolic comorbidities and age-related variability.

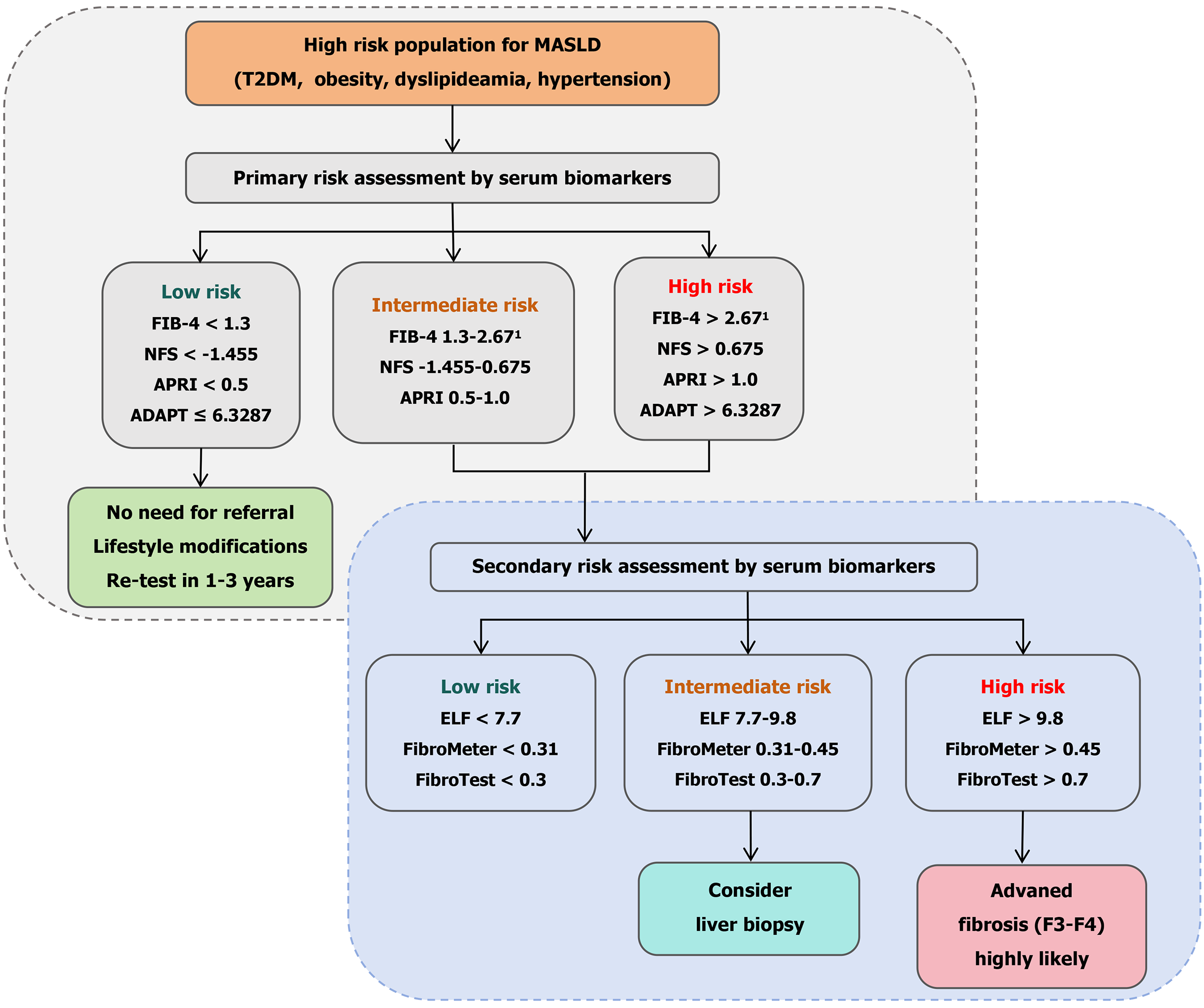

While FIB-4 effectively distinguishes advanced fibrosis from no/mild fibrosis in MASLD, it demonstrates limited discriminatory power for intermediate fibrosis stages. The score’s simplicity and reproducibility render it a valuable first-line screening tool, particularly advantageous in resource-limited clinical environments. Despite remaining a cornerstone of non-invasive fibrosis evaluation in MASLD, FIB-4 exhibits significant divergence in optimal diagnostic thresholds and performance characteristics compared to established NAFLD benchmarks. Crucially, age-specific cutoff adjustments are imperative to mitigate age-related false-positive rates and enhance diagnostic precision in elderly MASLD cohorts (Figure 1).

NAFLD fibrosis score (NFS), incorporating body mass index (BMI), age, impaired glucose metabolism, AST/ALT ratio, albumin, and platelet count, was originally developed from a cohort of NAFLD patients[39]. The cutoffs validated for this score are < -1.455 and > 0.675, with the lower cutoff having an negative predictive value (NPV) of 88% and the highest cutoff a PPV of 82%[39]. Jointly endorsed with FIB-4 by the European Association for the Study of the Liver, NFS remains one of the most widely utilized scoring systems for fibrosis severity assessment in clinical practice (Figure 1)[22]. It has been demonstrated reproducible accuracy in stratifying low-risk and high-risk groups for advanced fibrosis[29,40-42]. However, recent studies in MASLD cohorts reveal significantly reduced diagnostic performance compared to its established utility in NAFLD. Key limitations include elevated false-positive rates driven by BMI- and age-related score inflation[28], as well as compromised accuracy in patients with extreme platelet count abnormalities (e.g., asplenia or post-transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt)[43]. Notably, emerging evidence suggests that in MASLD patients with low BMI, NFS (cutoff > -1.455) outperforms FIB-4 in specificity for advanced fibrosis prediction (AUROC 0.85 vs 0.79)[44], highlighting its context-dependent utility in specific subpopulations.

The BARD score is calculated by summing three parameters: BMI > 28 kg/m2 (1 point), AST/ALT ratio > 0.8 (2 points), and diabetes (1 point), yielding a total range of 0-4 points[45]. Scores of 0-1 indicate low risk for advanced fibrosis, while 2-4 denote high risk. Initial validation studies reported promising performance (AUROC: 0.81%, NPV: 96%), though with limited PPV (43%)[45]. However, subsequent external validations revealed significantly reduced accuracy, with AUROCs of 0.59-0.61, PPVs of 27%-53%, and NPVs of 69%-89%[46,47]. Key limitations include poor reproducibility across cohorts and restricted applicability in obese populations. Additionally, the score’s performance may be confounded in ethnic groups predisposed to obesity-related complications at lower BMI thresholds, such as South Asian populations with hepatic steatosis development at relatively lean body weights[28,48].

Hepamet fibrosis score incorporates variables such as age, presence of diabetes, AST levels, albumin, platelet count, sex, and insulin resistance assessed via the homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance in non-diabetic individuals[49]. It demonstrates strong performance in ruling out advanced fibrosis, with sensitivity and NPV ranging from 74%-90% and 90%-98%, respectively[32,50,51]. However, its clinical utility is constrained in primary care settings due to the requi

N-terminal propeptide of type 3 collagen (PRO-C3) is a biomarker reflecting collagen synthesis during fibrogenesis. As a byproduct of extracellular matrix (ECM) remodeling, PRO-C3 is released during the cleavage of type 3 collagen pre

Building on the diagnostic potential of PRO-CC3, the algorithm integrates this biomarker with clinically accessible variables - age, diabetes status, PRO-C3, and thrombocyte (platelet) count (ADAPT) - to enhance fibrosis risk stratification[55]. In the ADAPT validation study, this composite score demonstrated superior diagnostic accuracy for advanced fibrosis in MASLD compared to established non-invasive tests (NITs). Across derivation and validation cohorts (431 biopsy-proven patients), ADAPT achieved robust AUROCs of 0.86 and 0.87, respectively, significantly outperforming APRI (AUROC: 0.73-0.78), FIB-4 (AUROC: 0.78-0.85), and NFS (AUROC: 0.78-0.79) in most comparisons. Further supporting its reliability, ADAPT maintained a standardized AUROC (0.89) and high NPV (> 90% across subpopulations). Critically, it eliminated the “indeterminate zone” plaguing other scores, correctly classifying 92% of advanced fibrosis cases and 74% of non-advanced cases using a single cutoff (6.3287)[55]. Unlike FIB-4 and NFS, ADAPT’s exclusion of liver enzymes reduced age-related confounding and enhanced applicability in normo-enzymatic patients, solidifying its position as a precise, clinically practical tool for first-line MASLD risk stratification.

However, PRO-C3 interpretation requires clinical contextualization. A critical limitation arises in advanced fibrotic stages, where reduced collagen synthetic activity in “burnt-out” fibrotic nodules may paradoxically normalize PRO-C3 levels, potentially leading to false-negative results[58]. Future studies should focus on longitudinal PRO-C3 monitoring to elucidate its role in tracking fibrosis regression during therapeutic interventions.

Mac-2 binding protein glycosylation isomer (M2BPGi), a glycoprotein predominantly expressed by activated hepatic stellate cells during liver injury, drives fibrogenesis through modulation of transforming growth factor β signaling, promoting ECM deposition. It further contributes to fibrosis by dysregulating matrix metalloproteinases, impairing ECM degradation and accelerating collagen accumulation. M2BPGi also exacerbates inflammation and fibrosis by upregulating pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., interleukin-6, tumor necrosis factor α) and suppressing the antifibrotic adipokine adip

In MASLD, elevated serum M2BPGi levels correlate with fibrosis severity, insulin resistance, and metabolic dysregulation, reflecting disease progression. At a cutoff of 0.71 cut-off index, M2BPGi demonstrates 78% sensitivity and 74% specificity with an AUROC of 0.823 for detecting advanced fibrosis[60]. Its diagnostic performance is particularly notable in pediatric MASLD, where it achieves an AUROC of 0.742 with a cutoff of 1.35 cut-off index for advanced fibrosis[61]. M2BPGi consistently outperforms conventional NITs for detecting advanced fibrosis. For example, in the study by Nah et al[62] (≥ F3), M2BPGi had an AUROC of 0.836, compared to 0.766 for FIB-4 and 0.735 for APRI[62]. Similarly, in the study by Jang et al[63] (≥ F3), M2BPGi had an AUROC of 0.900, compared to 0.641 for FIB-4, 0.894 for APRI, and 0.926 for MASLD[63]. Seko et al[64] conducted a comparative analysis of M2BPGi, the enhanced liver fibrosis (ELF), and FIB-4 for assessing fibrosis severity, emphasizing the potential clinical advantages of M2BPGi. Combination panels, such as M2BPGi + FIB-4, can further enhance diagnostic sensitivity, reaching a sensitivity of 87.1%, specificity of 82.5% for advan

However, standardization of M2BPGi assays is needed, as inter-laboratory variability necessitates harmonized protocols. The cost-effectiveness of routine M2BPGi testing also requires validation. Future research should focus on validating M2BPGi in diverse cohorts (e.g., non-Asian populations, pediatric patients) and developing multi-marker algorithms (e.g., combining M2BPGi with the ELF).

The ELF test, a patented serum-based panel, integrates three biomarkers: Hyaluronic acid, tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 1, and the N-terminal propeptide of type III procollagen is used to non-invasively assess hepatic fibrosis[66]. Originally derived from the European Liver Fibrosis test, this FDA-approved prognostic tool has demonstrated superior diagnostic accuracy in MASLD compared to other liver diseases, reflecting its ability to quantify ECM remodeling dynamics[66]. The ELF test exhibits robust diagnostic utility for advanced fibrosis in MASLD. A meta-analysis reported a sensitivity of 0.93 and specificity of 0.34 at a low cutoff value of 7.7 for excluding significant fibrosis, with NPVs ranging from 0.82 to 0.99 in low-prevalence (< 50%) cohorts. For advanced fibrosis detection, the recommended threshold of 9.8 achieves an AUROC of 0.83, with 65% sensitivity and 86% specificity (Table 1)[67]. Notably, in a Danish population-based study, ELF demonstrated a lower false-positive rate than FIB-4, positioning it as a reliable first-line screening tool to optimize referrals and reduce unnecessary biopsies[68].

Current guidelines endorse ELF as part of sequential diagnostic algorithms (Figure 1). The European Association for the Study of the Liver advocates combining ELF > 9.8 with FIB-4 > 1.30 and liver stiffness measurement (LSM) > 8 kPa to confirm high-risk advanced fibrosis[4,22]. Conversely, the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases incor

FibroTest is a multi-parametric serum assay combining age, gender, and six biochemical markers: Α2-macroglobulin, haptoglobin, apolipoprotein A-I, gamma-glutamyl transferase, total bilirubin, and cholinesterase to non-invasively evaluate liver fibrosis. This algorithm quantifies fibrotic activity by integrating markers reflecting hepatic inflammation, synthetic dysfunction, and cholestasis[69]. In MASLD cohorts, FibroTest demonstrates clinically relevant accuracy for fibrosis staging. At a low cutoff of 0.3 (90% sensitivity), it effectively excludes significant fibrosis, while a high cutoff of 0.7 (90% specificity) confirms its presence, aligning with guidelines recommending dual thresholds for rule-out and rule-in strategies. For intermediate risk stratification, a cutoff range of 0.30-0.48 achieves balanced performance, with 72% sensitivity and 85% specificity for detecting significant fibrosis[70]. Notably, at the 0.48 threshold, FibroTest exhibits utility in excluding advanced fibrosis, though its validation in MASLD remains less extensive compared to ELF and FibroMeter[22].

FibroTest leverages routine biochemical parameters, enabling integration into standard clinical workflows without specialized assays. However, its interpretation requires caution in conditions affecting non-hepatic markers (e.g., hemolysis altering haptoglobin levels or Gilbert’s syndrome elevating bilirubin), which may confound results[69]. Additionally, while FibroTest has demonstrated cross-etiology validity, MASLD-specific data are limited, necessitating further studies to optimize thresholds for metabolic-driven fibrosis phenotypes.

FibroMeter is an algorithm-based serum test specifically designed for MASLD, integrating parameters such as age, weight, AST, ALT, platelet count, blood glucose, and ferritin to systematically evaluate liver fibrosis[71]. This test demonstrates excellent diagnostic performance in MASLD, with an AUROC of 0.80-0.94 for diagnosing advanced fibrosis. A cutoff value of 0.45 is recommended to exclude advanced fibrosis, while a cutoff of 0.31 maximizes sensitivity and specificity in high-risk populations[71,72]. In a cross-sectional study of MASLD patients, FibroMeter showed diagnostic accuracy comparable to liver stiffness measurement, with enhanced predictive capability for advanced fibrosis[21]. Its unique advantage lies in incorporating metabolic markers such as glucose and ferritin, which directly reflect MASLD’s core pathological mechanisms-insulin resistance and iron overload-distinguishing it from tests focused solely on ECM remodeling (e.g., ELF)[73]. However, ferritin levels may be confounded by inflammation or hereditary hemochromatosis, and validation across diverse ethnic populations remains incomplete[73]. Current guidelines recommend combining FibroMeter with FIB-4 and LSM in a stepwise diagnostic workflow, optimizing referral decisions through a dual-threshold strategy (0.31 for initial screening and 0.45 for exclusion) to reduce unnecessary biopsies[22]. Although cost-effective in routine clinical practice, future studies should refine thresholds for metabolic-specific phenotypes and conduct longitudinal research to validate its utility in monitoring therapeutic responses.

Given the suboptimal performance of standalone NITs, combining serum biomarkers with LSM enhances diagnostic precision for liver fibrosis staging. Agile scores are composite biomarkers integrating LSM with routine clinical/Laboratory parameters (platelets, AST, ALT, diabetes, sex ± age) to stage fibrosis in MASLD. The Agile 3+ score diagnoses advanced fibrosis, while Agile 4 identifies cirrhosis (F4)[74]. External validation confirms their diagnostic accuracy equals LSM alone in MASLD (Agile 3+ AUC: 0.86 vs LSM: 0.86; Agile 4 AUC: 0.89 vs LSM: 0.90), but significantly reduces indeterminate classifications by 25%-55% when using dual thresholds (90% sensitivity/specificity). Agile 3+ cut-offs (< 0.351 rule-out; > 0.679 rule-in) correctly classify 67% of patients (vs 61% for LSM), with only 21% indeterminates (vs 28% for LSM). Agile 4 further optimizes cirrhosis diagnosis (79% correct classification; 11% indeterminates). Sequential use with FIB-4 (FIB-4 < 1.3 and Agile 3+) boosts correct classification to 75% and cuts indeterminates to 12%. Concurrently, concordant high-risk results (e.g., Agile 3+ > 0.679 + LSM > 12 kPa) increase specificity to 93% for advanced fibrosis[75]. Agile scores thus refine MASLD fibrosis staging by minimizing diagnostic uncertainty and enhancing integration into risk-stratification algorithms, though they require elastography access.

Given the dynamic nature of epigenetic markers and their critical role in mediating gene-environment interactions, multiple epigenetic markers have emerged as potential biomarkers for MASLD[76,77]. Emerging biomarkers for advanced fibrosis evaluation in MASLD demonstrate multi-modal diagnostic potential. Epigenetic markers, exemplified by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ plasma DNA methylation, exhibit promising diagnostic accuracy with an AUROC of 0.91, achieving 91% PPV and 87% NPV in distinguishing advanced fibrosis[78]. Immunological pathways also show utility, where macrophage activation markers such as soluble CD163 achieve an AUROC of 0.83 when combined with NFS. Similarly, macrophage-derived deaminase markers independently predict advanced fibrosis with an AUROC of 0.82[79,80]. While these novel biomarkers exhibit strong initial performance, current evidence predominantly derives from small-scale cross-sectional cohorts. Further validation through large-scale prospective studies and external cohorts is essential to confirm their diagnostic robustness and establish standardized clinical thresholds.

Genetic variants regulating core pathophysiological pathways in MASLD, including lipid metabolism, insulin/adipokine signaling, and inflammatory modulation, play pivotal roles in disease progression[76,81]. Among fibrosis-associated polymorphisms, the most extensively studied single-nucleotide polymorphisms involve the PNPLA3, TM6SF2, and MBOAT7 genes[82-84]. A cohort study evaluated 515 NAFLD patients demonstrated significant associations between these loci and hepatic injury: PNPLA3 variants concurrently elevate risks of steatosis and fibrosis, TM6SF2 primarily correlates with steatosis severity, while MBOAT7 specifically drives fibrogenesis[85]. Combining PNPLA3 and TM6SF2 genotypes with the FIB-4 slope facilitates the identification of patients at high risk for accelerated fibrosis progression, especially those with a baseline FIB-4 < 2.67, guiding early interventions such as lifestyle modifications and pharmacotherapy[86].

Emerging research focuses on constructing polygenic risk scores integrating clinical parameters (e.g., BMI, glycemic status) with genetic data to enhance predictive accuracy for fibrosis trajectories[76]. However, persisting challenges hinder clinical translation: (1) Ambiguous boundaries between risk stratification and prognostic prediction in polygenic risk scores applications; and (2) Limited generalizability due to Eurocentric bias in existing genome-wide association studies, necessitating validation in ethnically diverse cohorts[76].

The intimate linkage between MASLD and metabolic dysregulation has driven growing interest in leveraging meta

Emerging evidence highlights their specific associations with liver fibrosis staging. While circulating ANGPTL levels demonstrate inconsistent correlations with MASLD across studies[88,89], a meta-analysis of 13 clinical trials revealed that ANGPTL8 is significantly elevated in MASLD patients compared to healthy controls, with levels progressively increasing from mild to moderate-severe disease stages[88,90]. Notably, this gradient pattern suggests ANGPTL8’s potential utility in non-invasive fibrosis monitoring, particularly for distinguishing advanced fibrosis (F3-F4) from early-stage disease (F0-F2)[90]. Mechanistically, ANGPTL8 may exacerbate fibrogenesis by amplifying hepatic lipotoxicity and insulin resistance-key drivers of stellate cell activation. However, the fibrosis-specific regulatory roles of other ANGPTL family members (e.g., ANGPTL3 in lipoprotein remodeling, ANGPTL4 in adipose-liver crosstalk) remain underexplored, warranting longitudinal studies to dissect their stage-dependent contributions to fibrotic progression. Their dual role as metabolic regulators and fibrosis modulators underscores the need for standardized assays and multi-center validation to establish clinical thresholds aligned with histopathological staging criteria.

Targeting the underlying mechanisms of hepatic fibrogenesis to identify relevant biomarkers offers superior diagnostic value compared to conventional approaches. Verschuren et al[91] developed and validated a novel, mechanism-based blood biomarker panel (insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 7, systemic sclerosis 5-domain protein, semaphorin 4-domain protein) for non-invasive staging of hepatic fibrosis in MASLD. Utilizing a translational approach starting from a diet-induced fibrotic mouse model (LDLr-/-.Leiden) and progressing through human liver transcriptomics and serum protein analysis, the panel targets pathways linked to active collagen turnover. Evaluated using LightGBM modeling in a testing cohort (n = 128), the panel demonstrated high accuracy: AUCs of 0.82 for distinguishing no/mild fibrosis (F0/F1), 0.89 for significant fibrosis (F2), and 0.87 for advanced fibrosis/cirrhosis (F3/F4). This performance was validated in an independent cohort (n = 156), yielding AUCs of 0.84 for both F0/F1 and F3/F4 stages (though F2 prediction was more modest, AUC 0.62). Crucially, the overall diagnostic accuracy of the panel, termed timely liver model 3 model sig

Moreover, serum thrombospondin-2 (TSP2) levels are closely associated with the severity of liver fibrosis in patients with MASLD, particularly those with obesity. Levels increase progressively with higher fibrosis stages (F0 to F3), showing a significant positive correlation (after adjusting for confounders). Logistic regression analysis confirms that elevated serum TSP2 is an independent predictor of significant fibrosis (≥ F1: Odds ratio = 1.59; ≥ F2: Odds ratio = 1.93, after adjustment for sex, age, and BMI)[92]. The mechanism may be the high expression of TSP2 in hepatic stellate cells, which may promote collagen secretion and fibrosis progression by activating the ECM receptor interaction pathway and the phosphoinositide 3 - kinase and protein kinase B signaling pathway.

In summary, non-invasive blood biomarkers offer a promising alternative to liver biopsy for assessing liver fibrosis in MASLD. Established scores like FIB-4 and NFS, along with patented serum markers such as ELF and FibroTest, provide valuable tools for clinical diagnosis and risk stratification (Figure 1). Despite advances, barriers to widespread adoption persist, including inter-laboratory variability in proprietary assays (e.g., M2BPGi, ELF), insufficient validation in African and Latin American cohorts, and cost constraints limiting access to patented panels. Their performance, however, can vary across populations, necessitating further validation and refinement. While significant progress has been made in identifying novel diagnostics, including biomarkers and algorithms, none have yet achieved sufficient performance to fully replace liver biopsy. Future work should focus on developing and validating novel biomarkers, integrating multi-modal approaches, and standardizing protocols to enhance diagnostic accuracy and clinical utility. Future validation studies should prioritize ethnically diverse cohorts to optimize biomarker thresholds for MASLD subpopulations worldwide. While blood biomarkers provide accessible first-line tools, their integration with imaging optimizes risk stratification. Future studies should formalize cost-benefit analyses of multi-modal algorithms. Continued research is crucial to optimize patient outcomes and address the global burden of MASLD.

| 1. | Rinella ME, Lazarus JV, Ratziu V, Francque SM, Sanyal AJ, Kanwal F, Romero D, Abdelmalek MF, Anstee QM, Arab JP, Arrese M, Bataller R, Beuers U, Boursier J, Bugianesi E, Byrne CD, Narro GEC, Chowdhury A, Cortez-Pinto H, Cryer DR, Cusi K, El-Kassas M, Klein S, Eskridge W, Fan J, Gawrieh S, Guy CD, Harrison SA, Kim SU, Koot BG, Korenjak M, Kowdley KV, Lacaille F, Loomba R, Mitchell-Thain R, Morgan TR, Powell EE, Roden M, Romero-Gómez M, Silva M, Singh SP, Sookoian SC, Spearman CW, Tiniakos D, Valenti L, Vos MB, Wong VW, Xanthakos S, Yilmaz Y, Younossi Z, Hobbs A, Villota-Rivas M, Newsome PN; NAFLD Nomenclature consensus group. A multisociety Delphi consensus statement on new fatty liver disease nomenclature. Ann Hepatol. 2024;29:101133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 387] [Cited by in RCA: 401] [Article Influence: 200.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Teng ML, Ng CH, Huang DQ, Chan KE, Tan DJ, Lim WH, Yang JD, Tan E, Muthiah MD. Global incidence and prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2023;29:S32-S42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 448] [Article Influence: 149.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Riazi K, Azhari H, Charette JH, Underwood FE, King JA, Afshar EE, Swain MG, Congly SE, Kaplan GG, Shaheen AA. The prevalence and incidence of NAFLD worldwide: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;7:851-861. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 149] [Cited by in RCA: 1466] [Article Influence: 366.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Rinella ME, Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Siddiqui MS, Abdelmalek MF, Caldwell S, Barb D, Kleiner DE, Loomba R. AASLD Practice Guidance on the clinical assessment and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2023;77:1797-1835. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1465] [Cited by in RCA: 1598] [Article Influence: 532.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Armstrong MJ, Adams LA, Canbay A, Syn WK. Extrahepatic complications of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2014;59:1174-1197. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 387] [Cited by in RCA: 447] [Article Influence: 37.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Hagström H, Nasr P, Ekstedt M, Hammar U, Stål P, Hultcrantz R, Kechagias S. Fibrosis stage but not NASH predicts mortality and time to development of severe liver disease in biopsy-proven NAFLD. J Hepatol. 2017;67:1265-1273. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 540] [Cited by in RCA: 823] [Article Influence: 91.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (7)] |

| 7. | Vilar-Gomez E, Calzadilla-Bertot L, Wai-Sun Wong V, Castellanos M, Aller-de la Fuente R, Metwally M, Eslam M, Gonzalez-Fabian L, Alvarez-Quiñones Sanz M, Conde-Martin AF, De Boer B, McLeod D, Hung Chan AW, Chalasani N, George J, Adams LA, Romero-Gomez M. Fibrosis Severity as a Determinant of Cause-Specific Mortality in Patients With Advanced Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Multi-National Cohort Study. Gastroenterology. 2018;155:443-457.e17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 612] [Cited by in RCA: 641] [Article Influence: 80.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kumar V, Xin X, Ma J, Tan C, Osna N, Mahato RI. Therapeutic targets, novel drugs, and delivery systems for diabetes associated NAFLD and liver fibrosis. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2021;176:113888. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 25.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Rockey DC, Caldwell SH, Goodman ZD, Nelson RC, Smith AD; American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Liver biopsy. Hepatology. 2009;49:1017-1044. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1449] [Cited by in RCA: 1636] [Article Influence: 96.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 10. | Bedossa P, Dargère D, Paradis V. Sampling variability of liver fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2003;38:1449-1457. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1193] [Cited by in RCA: 1408] [Article Influence: 61.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Bravo AA, Sheth SG, Chopra S. Liver biopsy. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:495-500. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1843] [Cited by in RCA: 1761] [Article Influence: 70.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 12. | Loomba R, Adams LA. Advances in non-invasive assessment of hepatic fibrosis. Gut. 2020;69:1343-1352. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 251] [Article Influence: 41.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 13. | Cataldo I, Sarcognato S, Sacchi D, Cacciatore M, Baciorri F, Mangia A, Cazzagon N, Guido M. Pathology of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Pathologica. 2021;113:194-202. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Wong VW, Chu WC, Wong GL, Chan RS, Chim AM, Ong A, Yeung DK, Yiu KK, Chu SH, Woo J, Chan FK, Chan HL. Prevalence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and advanced fibrosis in Hong Kong Chinese: a population study using proton-magnetic resonance spectroscopy and transient elastography. Gut. 2012;61:409-415. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 356] [Cited by in RCA: 401] [Article Influence: 28.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Mózes FE, Lee JA, Vali Y, Alzoubi O, Staufer K, Trauner M, Paternostro R, Stauber RE, Holleboom AG, van Dijk AM, Mak AL, Boursier J, de Saint Loup M, Shima T, Bugianesi E, Gaia S, Armandi A, Shalimar, Lupșor-Platon M, Wong VW, Li G, Wong GL, Cobbold J, Karlas T, Wiegand J, Sebastiani G, Tsochatzis E, Liguori A, Yoneda M, Nakajima A, Hagström H, Akbari C, Hirooka M, Chan WK, Mahadeva S, Rajaram R, Zheng MH, George J, Eslam M, Petta S, Pennisi G, Viganò M, Ridolfo S, Aithal GP, Palaniyappan N, Lee DH, Ekstedt M, Nasr P, Cassinotto C, de Lédinghen V, Berzigotti A, Mendoza YP, Noureddin M, Truong E, Fournier-Poizat C, Geier A, Martic M, Tuthill T, Anstee QM, Harrison SA, Bossuyt PM, Pavlides M; LITMUS investigators. Performance of non-invasive tests and histology for the prediction of clinical outcomes in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: an individual participant data meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;8:704-713. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 42.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Chan WL, Chong SE, Chang F, Lai LL, Chuah KH, Nik Mustapha NR, Mahadeva S, Chan WK. Long-term clinical outcomes of adults with metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease: a single-centre prospective cohort study with baseline liver biopsy. Hepatol Int. 2023;17:870-881. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Hussain A, Patel PJ, Rhodes F, Srivastava A, Patch D, Rosenberg W. Decompensated cirrhosis is the commonest presentation for NAFLD patients undergoing liver transplant assessment. Clin Med (Lond). 2020;20:313-318. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kwok R, Choi KC, Wong GL, Zhang Y, Chan HL, Luk AO, Shu SS, Chan AW, Yeung MW, Chan JC, Kong AP, Wong VW. Screening diabetic patients for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease with controlled attenuation parameter and liver stiffness measurements: a prospective cohort study. Gut. 2016;65:1359-1368. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 298] [Cited by in RCA: 372] [Article Influence: 37.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Lai LL, Wan Yusoff WNI, Vethakkan SR, Nik Mustapha NR, Mahadeva S, Chan WK. Screening for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus using transient elastography. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;34:1396-1403. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Abdelhameed F, Kite C, Lagojda L, Dallaway A, Chatha KK, Chaggar SS, Dalamaga M, Kassi E, Kyrou I, Randeva HS. Non-invasive Scores and Serum Biomarkers for Fatty Liver in the Era of Metabolic Dysfunction-associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD): A Comprehensive Review From NAFLD to MAFLD and MASLD. Curr Obes Rep. 2024;13:510-531. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 47.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Boursier J, Vergniol J, Guillet A, Hiriart JB, Lannes A, Le Bail B, Michalak S, Chermak F, Bertrais S, Foucher J, Oberti F, Charbonnier M, Fouchard-Hubert I, Rousselet MC, Calès P, de Lédinghen V. Diagnostic accuracy and prognostic significance of blood fibrosis tests and liver stiffness measurement by FibroScan in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol. 2016;65:570-578. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 247] [Cited by in RCA: 311] [Article Influence: 31.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines on non-invasive tests for evaluation of liver disease severity and prognosis - 2021 update. J Hepatol. 2021;75:659-689. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 993] [Cited by in RCA: 1305] [Article Influence: 261.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 23. | Verma S, Jensen D, Hart J, Mohanty SR. Predictive value of ALT levels for non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) and advanced fibrosis in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Liver Int. 2013;33:1398-1405. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 201] [Cited by in RCA: 248] [Article Influence: 19.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 24. | Wong VW, Wong GL, Tsang SW, Hui AY, Chan AW, Choi PC, Chim AM, Chu S, Chan FK, Sung JJ, Chan HL. Metabolic and histological features of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease patients with different serum alanine aminotransferase levels. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;29:387-396. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Sheth SG, Flamm SL, Gordon FD, Chopra S. AST/ALT ratio predicts cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:44-48. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 393] [Cited by in RCA: 379] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Wai CT, Greenson JK, Fontana RJ, Kalbfleisch JD, Marrero JA, Conjeevaram HS, Lok AS. A simple noninvasive index can predict both significant fibrosis and cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2003;38:518-526. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2762] [Cited by in RCA: 3346] [Article Influence: 145.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Vilar-Gomez E, Chalasani N. Non-invasive assessment of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: Clinical prediction rules and blood-based biomarkers. J Hepatol. 2018;68:305-315. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 331] [Cited by in RCA: 467] [Article Influence: 58.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Li G, Zhang X, Lin H, Liang LY, Wong GL, Wong VW. Non-invasive tests of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Chin Med J (Engl). 2022;135:532-546. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | McPherson S, Stewart SF, Henderson E, Burt AD, Day CP. Simple non-invasive fibrosis scoring systems can reliably exclude advanced fibrosis in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Gut. 2010;59:1265-1269. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 572] [Cited by in RCA: 699] [Article Influence: 43.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Xiao G, Zhu S, Xiao X, Yan L, Yang J, Wu G. Comparison of laboratory tests, ultrasound, or magnetic resonance elastography to detect fibrosis in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A meta-analysis. Hepatology. 2017;66:1486-1501. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 492] [Cited by in RCA: 677] [Article Influence: 75.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Peleg N, Issachar A, Sneh-Arbib O, Shlomai A. AST to Platelet Ratio Index and fibrosis 4 calculator scores for non-invasive assessment of hepatic fibrosis in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Dig Liver Dis. 2017;49:1133-1138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Rigor J, Diegues A, Presa J, Barata P, Martins-Mendes D. Noninvasive fibrosis tools in NAFLD: validation of APRI, BARD, FIB-4, NAFLD fibrosis score, and Hepamet fibrosis score in a Portuguese population. Postgrad Med. 2022;134:435-440. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Kouvari M, Valenzuela-Vallejo L, Guatibonza-Garcia V, Polyzos SA, Deng Y, Kokkorakis M, Agraz M, Mylonakis SC, Katsarou A, Verrastro O, Markakis G, Eslam M, Papatheodoridis G, George J, Mingrone G, Mantzoros CS. Liver biopsy-based validation, confirmation and comparison of the diagnostic performance of established and novel non-invasive steatotic liver disease indexes: Results from a large multi-center study. Metabolism. 2023;147:155666. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 19.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Sterling RK, Lissen E, Clumeck N, Sola R, Correa MC, Montaner J, S Sulkowski M, Torriani FJ, Dieterich DT, Thomas DL, Messinger D, Nelson M; APRICOT Clinical Investigators. Development of a simple noninvasive index to predict significant fibrosis in patients with HIV/HCV coinfection. Hepatology. 2006;43:1317-1325. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2633] [Cited by in RCA: 3817] [Article Influence: 190.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Younossi ZM, Paik JM, Stepanova M, Ong J, Alqahtani S, Henry L. Clinical profiles and mortality rates are similar for metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol. 2024;80:694-701. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in RCA: 203] [Article Influence: 101.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Green V, Lin J, McGrath M, Lloyd A, Ma P, Higa K, Roytman M. FIB-4 Reliability in Patients With Severe Obesity: Lower Cutoffs Needed? J Clin Gastroenterol. 2024;58:825-829. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | McPherson S, Hardy T, Dufour JF, Petta S, Romero-Gomez M, Allison M, Oliveira CP, Francque S, Van Gaal L, Schattenberg JM, Tiniakos D, Burt A, Bugianesi E, Ratziu V, Day CP, Anstee QM. Age as a Confounding Factor for the Accurate Non-Invasive Diagnosis of Advanced NAFLD Fibrosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:740-751. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 644] [Cited by in RCA: 711] [Article Influence: 79.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Ishiba H, Sumida Y, Tanaka S, Yoneda M, Hyogo H, Ono M, Fujii H, Eguchi Y, Suzuki Y, Yoneda M, Takahashi H, Nakahara T, Seko Y, Mori K, Kanemasa K, Shimada K, Imai S, Imajo K, Kawaguchi T, Nakajima A, Chayama K, Saibara T, Shima T, Fujimoto K, Okanoue T, Itoh Y; Japan Study Group of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (JSG-NAFLD). The novel cutoff points for the FIB4 index categorized by age increase the diagnostic accuracy in NAFLD: a multi-center study. J Gastroenterol. 2018;53:1216-1224. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Angulo P, Hui JM, Marchesini G, Bugianesi E, George J, Farrell GC, Enders F, Saksena S, Burt AD, Bida JP, Lindor K, Sanderson SO, Lenzi M, Adams LA, Kench J, Therneau TM, Day CP. The NAFLD fibrosis score: a noninvasive system that identifies liver fibrosis in patients with NAFLD. Hepatology. 2007;45:846-854. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1917] [Cited by in RCA: 2374] [Article Influence: 124.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 40. | Cichoż-Lach H, Celiński K, Prozorow-Król B, Swatek J, Słomka M, Lach T. The BARD score and the NAFLD fibrosis score in the assessment of advanced liver fibrosis in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Med Sci Monit. 2012;18:CR735-CR740. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Ruffillo G, Fassio E, Alvarez E, Landeira G, Longo C, Domínguez N, Gualano G. Comparison of NAFLD fibrosis score and BARD score in predicting fibrosis in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol. 2011;54:160-163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Fujii H, Enomoto M, Fukushima W, Tamori A, Sakaguchi H, Kawada N. Applicability of BARD score to Japanese patients with NAFLD. Gut. 2009;58:1566-7; author reply 1567. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Altamirano J, Qi Q, Choudhry S, Abdallah M, Singal AK, Humar A, Bataller R, Borhani AA, Duarte-Rojo A. Non-invasive diagnosis: non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and alcoholic liver disease. Transl Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5:31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Dabbah S, Ben Yakov G, Kaufmann MI, Cohen-Ezra O, Likhter M, Davidov Y, Ben Ari Z. Predictors of advanced liver fibrosis and the performance of fibrosis scores: lean compared to non-lean metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) patients. Minerva Gastroenterol (Torino). 2024;70:322-331. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Harrison SA, Oliver D, Arnold HL, Gogia S, Neuschwander-Tetri BA. Development and validation of a simple NAFLD clinical scoring system for identifying patients without advanced disease. Gut. 2008;57:1441-1447. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 545] [Cited by in RCA: 651] [Article Influence: 36.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Wu YL, Kumar R, Wang MF, Singh M, Huang JF, Zhu YY, Lin S. Validation of conventional non-invasive fibrosis scoring systems in patients with metabolic associated fatty liver disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2021;27:5753-5763. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 47. | Chen X, Goh GB, Huang J, Wu Y, Wang M, Kumar R, Lin S, Zhu Y. Validation of Non-invasive Fibrosis Scores for Predicting Advanced Fibrosis in Metabolic-associated Fatty Liver Disease. J Clin Transl Hepatol. 2022;10:589-594. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Zhou JH, Cai JJ, She ZG, Li HL. Noninvasive evaluation of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Current evidence and practice. World J Gastroenterol. 2019;25:1307-1326. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 173] [Cited by in RCA: 176] [Article Influence: 25.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 49. | Ampuero J, Pais R, Aller R, Gallego-Durán R, Crespo J, García-Monzón C, Boursier J, Vilar E, Petta S, Zheng MH, Escudero D, Calleja JL, Aspichueta P, Diago M, Rosales JM, Caballería J, Gómez-Camarero J, Lo Iacono O, Benlloch S, Albillos A, Turnes J, Banales JM, Ratziu V, Romero-Gómez M; HEPAmet Registry. Development and Validation of Hepamet Fibrosis Scoring System-A Simple, Noninvasive Test to Identify Patients With Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease With Advanced Fibrosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18:216-225.e5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 21.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Zambrano-Huailla R, Guedes L, Stefano JT, de Souza AAA, Marciano S, Yvamoto E, Michalczuk MT, Vanni DS, Rodriguez H, Carrilho FJ, Alvares-da-Silva MR, Gadano A, Arrese M, Miranda AL, Oliveira CP. Diagnostic performance of three non-invasive fibrosis scores (Hepamet, FIB-4, NAFLD fibrosis score) in NAFLD patients from a mixed Latin American population. Ann Hepatol. 2020;19:622-626. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Chong SE, Chang F, Chuah KH, Sthaneshwar P, Nik Mustapha NR, Mahadeva S, Chan WK. Validation of the Hepamet fibrosis score in a multi-ethnic Asian population. Ann Hepatol. 2023;28:100888. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Karsdal MA, Hjuler ST, Luo Y, Rasmussen DGK, Nielsen MJ, Holm Nielsen S, Leeming DJ, Goodman Z, Arch RH, Patel K, Schuppan D. Assessment of liver fibrosis progression and regression by a serological collagen turnover profile. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2019;316:G25-G31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Nielsen MJ, Leeming DJ, Goodman Z, Friedman S, Frederiksen P, Rasmussen DGK, Vig P, Seyedkazemi S, Fischer L, Torstenson R, Karsdal MA, Lefebvre E, Sanyal AJ, Ratziu V. Comparison of ADAPT, FIB-4 and APRI as non-invasive predictors of liver fibrosis and NASH within the CENTAUR screening population. J Hepatol. 2021;75:1292-1300. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Hansen JF, Juul Nielsen M, Nyström K, Leeming DJ, Lagging M, Norkrans G, Brehm Christensen P, Karsdal M. PRO-C3: a new and more precise collagen marker for liver fibrosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2018;53:83-87. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Daniels SJ, Leeming DJ, Eslam M, Hashem AM, Nielsen MJ, Krag A, Karsdal MA, Grove JI, Neil Guha I, Kawaguchi T, Torimura T, McLeod D, Akiba J, Kaye P, de Boer B, Aithal GP, Adams LA, George J. ADAPT: An Algorithm Incorporating PRO-C3 Accurately Identifies Patients With NAFLD and Advanced Fibrosis. Hepatology. 2019;69:1075-1086. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 202] [Cited by in RCA: 208] [Article Influence: 29.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Mak AL, Lee J, van Dijk AM, Vali Y, Aithal GP, Schattenberg JM, Anstee QM, Brosnan MJ, Zafarmand MH, Ramsoekh D, Harrison SA, Nieuwdorp M, Bossuyt PM, Holleboom AG. Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis: Diagnostic Accuracy of Pro-C3 for Hepatic Fibrosis in Patients with Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Biomedicines. 2021;9:1920. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Karsdal MA, Henriksen K, Nielsen MJ, Byrjalsen I, Leeming DJ, Gardner S, Goodman Z, Patel K, Krag A, Christiansen C, Schuppan D. Fibrogenesis assessed by serological type III collagen formation identifies patients with progressive liver fibrosis and responders to a potential antifibrotic therapy. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2016;311:G1009-G1017. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Luo Y, Oseini A, Gagnon R, Charles ED, Sidik K, Vincent R, Collen R, Idowu M, Contos MJ, Mirshahi F, Daita K, Asgharpour A, Siddiqui MS, Jarai G, Rosen G, Christian R, Sanyal AJ. An Evaluation of the Collagen Fragments Related to Fibrogenesis and Fibrolysis in Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. Sci Rep. 2018;8:12414. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Sotoudeheian M. Value of Mac-2 Binding Protein Glycosylation Isomer (M2BPGi) in Assessing Liver Fibrosis in Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Liver Disease: A Comprehensive Review of its Serum Biomarker Role. Curr Protein Pept Sci. 2025;26:6-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Moon SY, Baek YH, Jang SY, Jun DW, Yoon KT, Cho YY, Jo HG, Jo AJ. Proposal of a Novel Serological Algorithm Combining FIB-4 and Serum M2BPGi for Advanced Fibrosis in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Gut Liver. 2024;18:283-293. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Kwon Y, Kim ES, Choe YH, Kim MJ. Stratification by Non-invasive Biomarkers of Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Children. Front Pediatr. 2022;10:846273. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Nah EH, Cho S, Kim S, Kim HS, Cho HI. Diagnostic performance of Mac-2 binding protein glycosylation isomer (M2BPGi) in screening liver fibrosis in health checkups. J Clin Lab Anal. 2020;34:e23316. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Jang SY, Tak WY, Park SY, Kweon YO, Lee YR, Kim G, Hur K, Han MH, Lee WK. Diagnostic Efficacy of Serum Mac-2 Binding Protein Glycosylation Isomer and Other Markers for Liver Fibrosis in Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Diseases. Ann Lab Med. 2021;41:302-309. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Seko Y, Takahashi H, Toyoda H, Hayashi H, Yamaguchi K, Iwaki M, Yoneda M, Arai T, Shima T, Fujii H, Morishita A, Kawata K, Tomita K, Kawanaka M, Yoshida Y, Ikegami T, Notsumata K, Oeda S, Kamada Y, Sumida Y, Fukushima H, Miyoshi E, Aishima S, Okanoue T, Nakajima A, Itoh Y; Japan Study Group of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (JSG-NAFLD). Diagnostic accuracy of enhanced liver fibrosis test for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis-related fibrosis: Multicenter study. Hepatol Res. 2023;53:312-321. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Kim M, Jun DW, Park H, Kang BK, Sumida Y. Sequential Combination of FIB-4 Followed by M2BPGi Enhanced Diagnostic Performance for Advanced Hepatic Fibrosis in an Average Risk Population. J Clin Med. 2020;9:1119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Guha IN, Parkes J, Roderick P, Chattopadhyay D, Cross R, Harris S, Kaye P, Burt AD, Ryder SD, Aithal GP, Day CP, Rosenberg WM. Noninvasive markers of fibrosis in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Validating the European Liver Fibrosis Panel and exploring simple markers. Hepatology. 2008;47:455-460. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 583] [Cited by in RCA: 555] [Article Influence: 30.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Vali Y, Lee J, Boursier J, Spijker R, Löffler J, Verheij J, Brosnan MJ, Böcskei Z, Anstee QM, Bossuyt PM, Zafarmand MH; LITMUS systematic review team(†). Enhanced liver fibrosis test for the non-invasive diagnosis of fibrosis in patients with NAFLD: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hepatol. 2020;73:252-262. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 225] [Article Influence: 37.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Kjaergaard M, Lindvig KP, Thorhauge KH, Andersen P, Hansen JK, Kastrup N, Jensen JM, Hansen CD, Johansen S, Israelsen M, Torp N, Trelle MB, Shan S, Detlefsen S, Antonsen S, Andersen JE, Graupera I, Ginés P, Thiele M, Krag A. Using the ELF test, FIB-4 and NAFLD fibrosis score to screen the population for liver disease. J Hepatol. 2023;79:277-286. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 151] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Ratziu V, Massard J, Charlotte F, Messous D, Imbert-Bismut F, Bonyhay L, Tahiri M, Munteanu M, Thabut D, Cadranel JF, Le Bail B, de Ledinghen V, Poynard T; LIDO Study Group; CYTOL study group. Diagnostic value of biochemical markers (FibroTest-FibroSURE) for the prediction of liver fibrosis in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. BMC Gastroenterol. 2006;6:6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 311] [Cited by in RCA: 329] [Article Influence: 16.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | López Tórrez SM, Ayala CO, Ruggiro PB, Costa CAD, Wagner MB, Padoin AV, Mattiello R. Accuracy of prognostic serological biomarkers in predicting liver fibrosis severity in people with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease: a meta-analysis of over 40,000 participants. Front Nutr. 2024;11:1284509. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Calès P, Boursier J, Oberti F, Hubert I, Gallois Y, Rousselet MC, Dib N, Moal V, Macchi L, Chevailler A, Michalak S, Hunault G, Chaigneau J, Sawadogo A, Lunel F. FibroMeters: a family of blood tests for liver fibrosis. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2008;32:40-51. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Guillaume M, Moal V, Delabaudiere C, Zuberbuhler F, Robic MA, Lannes A, Metivier S, Oberti F, Gourdy P, Fouchard-Hubert I, Selves J, Michalak S, Peron JM, Cales P, Bureau C, Boursier J. Direct comparison of the specialised blood fibrosis tests FibroMeter(V2G) and Enhanced Liver Fibrosis score in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease from tertiary care centres. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2019;50:1214-1222. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Calès P, Lainé F, Boursier J, Deugnier Y, Moal V, Oberti F, Hunault G, Rousselet MC, Hubert I, Laafi J, Ducluzeaux PH, Lunel F. Comparison of blood tests for liver fibrosis specific or not to NAFLD. J Hepatol. 2009;50:165-173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 190] [Cited by in RCA: 170] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Sanyal AJ, Foucquier J, Younossi ZM, Harrison SA, Newsome PN, Chan WK, Yilmaz Y, De Ledinghen V, Costentin C, Zheng MH, Wai-Sun Wong V, Elkhashab M, Huss RS, Myers RP, Roux M, Labourdette A, Destro M, Fournier-Poizat C, Miette V, Sandrin L, Boursier J. Enhanced diagnosis of advanced fibrosis and cirrhosis in individuals with NAFLD using FibroScan-based Agile scores. J Hepatol. 2023;78:247-259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 153] [Article Influence: 51.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Papatheodoridi M, De Ledinghen V, Lupsor-Platon M, Bronte F, Boursier J, Elshaarawy O, Marra F, Thiele M, Markakis G, Payance A, Brodkin E, Castera L, Papatheodoridis G, Krag A, Arena U, Mueller S, Cales P, Calvaruso V, Delamarre A, Pinzani M, Tsochatzis EA. Agile scores in MASLD and ALD: External validation and their utility in clinical algorithms. J Hepatol. 2024;81:590-599. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Alharthi J, Eslam M. Biomarkers of Metabolic (Dysfunction)-associated Fatty Liver Disease: An Update. J Clin Transl Hepatol. 2022;10:134-139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Bayoumi A, Grønbæk H, George J, Eslam M. The Epigenetic Drug Discovery Landscape for Metabolic-associated Fatty Liver Disease. Trends Genet. 2020;36:429-441. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 78. | Hardy T, Zeybel M, Day CP, Dipper C, Masson S, McPherson S, Henderson E, Tiniakos D, White S, French J, Mann DA, Anstee QM, Mann J. Plasma DNA methylation: a potential biomarker for stratification of liver fibrosis in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Gut. 2017;66:1321-1328. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 138] [Cited by in RCA: 183] [Article Influence: 20.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Kazankov K, Barrera F, Møller HJ, Rosso C, Bugianesi E, David E, Younes R, Esmaili S, Eslam M, McLeod D, Bibby BM, Vilstrup H, George J, Grønbaek H. The macrophage activation marker sCD163 is associated with morphological disease stages in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Liver Int. 2016;36:1549-1557. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Jiang ZG, Sandhu B, Feldbrügge L, Yee EU, Csizmadia E, Mitsuhashi S, Huang J, Afdhal NH, Robson SC, Lai M. Serum Activity of Macrophage-Derived Adenosine Deaminase 2 Is Associated With Liver Fibrosis in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16:1170-1172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Campos-Murguía A, Ruiz-Margáin A, González-Regueiro JA, Macías-Rodríguez RU. Clinical assessment and management of liver fibrosis in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2020;26:5919-5943. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 82. | Schwimmer JB, Celedon MA, Lavine JE, Salem R, Campbell N, Schork NJ, Shiehmorteza M, Yokoo T, Chavez A, Middleton MS, Sirlin CB. Heritability of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:1585-1592. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 381] [Cited by in RCA: 366] [Article Influence: 21.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 83. | Koo BK, Joo SK, Kim D, Bae JM, Park JH, Kim JH, Kim W. Additive effects of PNPLA3 and TM6SF2 on the histological severity of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;33:1277-1285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 84. | Mancina RM, Dongiovanni P, Petta S, Pingitore P, Meroni M, Rametta R, Borén J, Montalcini T, Pujia A, Wiklund O, Hindy G, Spagnuolo R, Motta BM, Pipitone RM, Craxì A, Fargion S, Nobili V, Käkelä P, Kärjä V, Männistö V, Pihlajamäki J, Reilly DF, Castro-Perez J, Kozlitina J, Valenti L, Romeo S. The MBOAT7-TMC4 Variant rs641738 Increases Risk of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Individuals of European Descent. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:1219-1230.e6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 385] [Cited by in RCA: 538] [Article Influence: 53.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 85. | Krawczyk M, Rau M, Schattenberg JM, Bantel H, Pathil A, Demir M, Kluwe J, Boettler T, Lammert F, Geier A; NAFLD Clinical Study Group. Combined effects of the PNPLA3 rs738409, TM6SF2 rs58542926, and MBOAT7 rs641738 variants on NAFLD severity: a multicenter biopsy-based study. J Lipid Res. 2017;58:247-255. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 156] [Article Influence: 15.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 86. | Kaplan DE, Teerlink CC, Schwantes-An TH, Norden-Krichmar TM, DuVall SL, Morgan TR, Tsao PS, Voight BF, Lynch JA, Vujković M, Chang KM. Clinical and genetic risk factors for progressive fibrosis in metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. Hepatol Commun. 2024;8:e0487. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 87. | Su X, Xu Q, Li Z, Ren Y, Jiao Q, Wang L, Wang Y. Role of the angiopoietin-like protein family in the progression of NAFLD. Heliyon. 2024;10:e27739. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 88. | Lee YH, Lee SG, Lee CJ, Kim SH, Song YM, Yoon MR, Jeon BH, Lee JH, Lee BW, Kang ES, Lee HC, Cha BS. Association between betatrophin/ANGPTL8 and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: animal and human studies. Sci Rep. 2016;6:24013. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 89. | Altun Ö, Dikker O, Arman Y, Ugurlukisi B, Kutlu O, Ozgun Cil E, Aydin Yoldemir S, Akarsu M, Ozcan M, Kalyon S, Ozsoy N, Tükek T. Serum Angiopoietin-like peptide 4 levels in patients with hepatic steatosis. Cytokine. 2018;111:496-499. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 90. | Ke Y, Liu S, Zhang Z, Hu J. Circulating angiopoietin-like proteins in metabolic-associated fatty liver disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lipids Health Dis. 2021;20:55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 91. | Verschuren L, Mak AL, van Koppen A, Özsezen S, Difrancesco S, Caspers MPM, Snabel J, van der Meer D, van Dijk AM, Rashu EB, Nabilou P, Werge MP, van Son K, Kleemann R, Kiliaan AJ, Hazebroek EJ, Boonstra A, Brouwer WP, Doukas M, Gupta S, Kluft C, Nieuwdorp M, Verheij J, Gluud LL, Holleboom AG, Tushuizen ME, Hanemaaijer R. Development of a novel non-invasive biomarker panel for hepatic fibrosis in MASLD. Nat Commun. 2024;15:4564. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 92. | Wu X, Cheung CKY, Ye D, Chakrabarti S, Mahajan H, Yan S, Song E, Yang W, Lee CH, Lam KSL, Wang C, Xu A. Serum Thrombospondin-2 Levels Are Closely Associated With the Severity of Metabolic Syndrome and Metabolic Associated Fatty Liver Disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2022;107:e3230-e3240. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/