Published online Nov 27, 2025. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v17.i11.110050

Revised: June 18, 2025

Accepted: October 9, 2025

Published online: November 27, 2025

Processing time: 183 Days and 1.5 Hours

Laparoscopic surgery is increasingly used for complex hepatolithiasis; however, data on laparoscopic vs open surgery remain limited. This study was undertaken to test the hypothesis that laparoscopic surgery offers comparable safety and efficacy to open surgery, with added benefits in recovery outcomes.

To compare clinical outcomes between laparoscopic and open approaches in complex hepatolithiasis.

This retrospective cohort study was conducted at Ningde Municipal Hospital, a tertiary care center, and included 80 patients with complex hepatolithiasis treated between January 2020 and August 2024. Patients were non-randomly allocated to laparoscopic (n = 40) or open surgery (n = 40) groups based on the treatment period. Clinical, intraoperative, and postoperative data were analyzed using appropriate parametric or non-parametric tests; categorical data were analyzed using χ2 or Fisher’s exact test.

Laparoscopic surgery was associated with a longer median operative time (250.0 minutes vs 207.0 minutes, P = 0.003) but shorter postoperative hospital stay (9.0 days vs 14.0 days, P < 0.001) compared to open surgery. Wound infection rates were significantly less frequent in the laparoscopic group (5.0% vs 22.5%, P = 0.023). Stone clearance rates and overall complications were comparable. One case of perioperative mortality occurred in the open surgery cohort.

Laparoscopic surgery is a feasible and safe alternative to open surgery for complex hepatolithiasis, offering faster recovery and reduced wound-related complications.

Core Tip: This retrospective study compares laparoscopic and open surgical approaches for complex hepatolithiasis, a challenging condition involving intrahepatic bile duct stones and anatomical distortions. Despite a longer operative time, laparoscopic surgery resulted in significantly shorter hospital stays and lower wound infection rates, while maintaining similar stone clearance and complication rates. The study highlights the feasibility and safety of minimally invasive liver surgery in high-risk patients when performed under strict adherence to surgical indication selection criteria, skillful utilization of anatomical characteristics of Laennec’s capsule of the liver, and standardized operative protocols.

- Citation: Lin DX, Zhuo XB, Chang GJ, Lei WD, Huang J, Zhang Y, Qiu ZJ, Zhang SY. Laparoscopic vs open surgery for complex hepatolithiasis: A retrospective comparative study. World J Hepatol 2025; 17(11): 110050

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v17/i11/110050.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v17.i11.110050

Hepatolithiasis, characterized by the formation of stones within the intrahepatic bile ducts, remains prevalent in East Asia and poses significant surgical challenges due to its association with biliary strictures, hepatic atrophy, and recurrent cholangitis[1,2]. Surgical management becomes particularly challenging when prior biliary interventions, anatomical distortion, or cirrhosis co-exist, elevating intraoperative complexity and postoperative morbidity[3].

Although open surgery offers direct haptic feedback and broad exposure, it is linked to significant morbidity and extended hospital stays[4-6]. In contrast, laparoscopic approaches reduce surgical trauma and accelerate recovery, and are increasingly employed in hepatobiliary surgery[6,7]. The emergence of tools such as indocyanine green fluorescence imaging, intraoperative cholangioscopy, and robotic platforms has broadened the feasibility of laparoscopy in anatomically demanding hepatobiliary procedures.

However, evidence comparing laparoscopic and open surgery in complex hepatolithiasis remains limited. Here, we report a single-center retrospective study comparing the outcomes of laparoscopic vs open surgery in patients with high-risk hepatolithiasis. By evaluating perioperative metrics and long-term outcomes, we aim to define the role of minimally invasive surgery in this complex clinical setting.

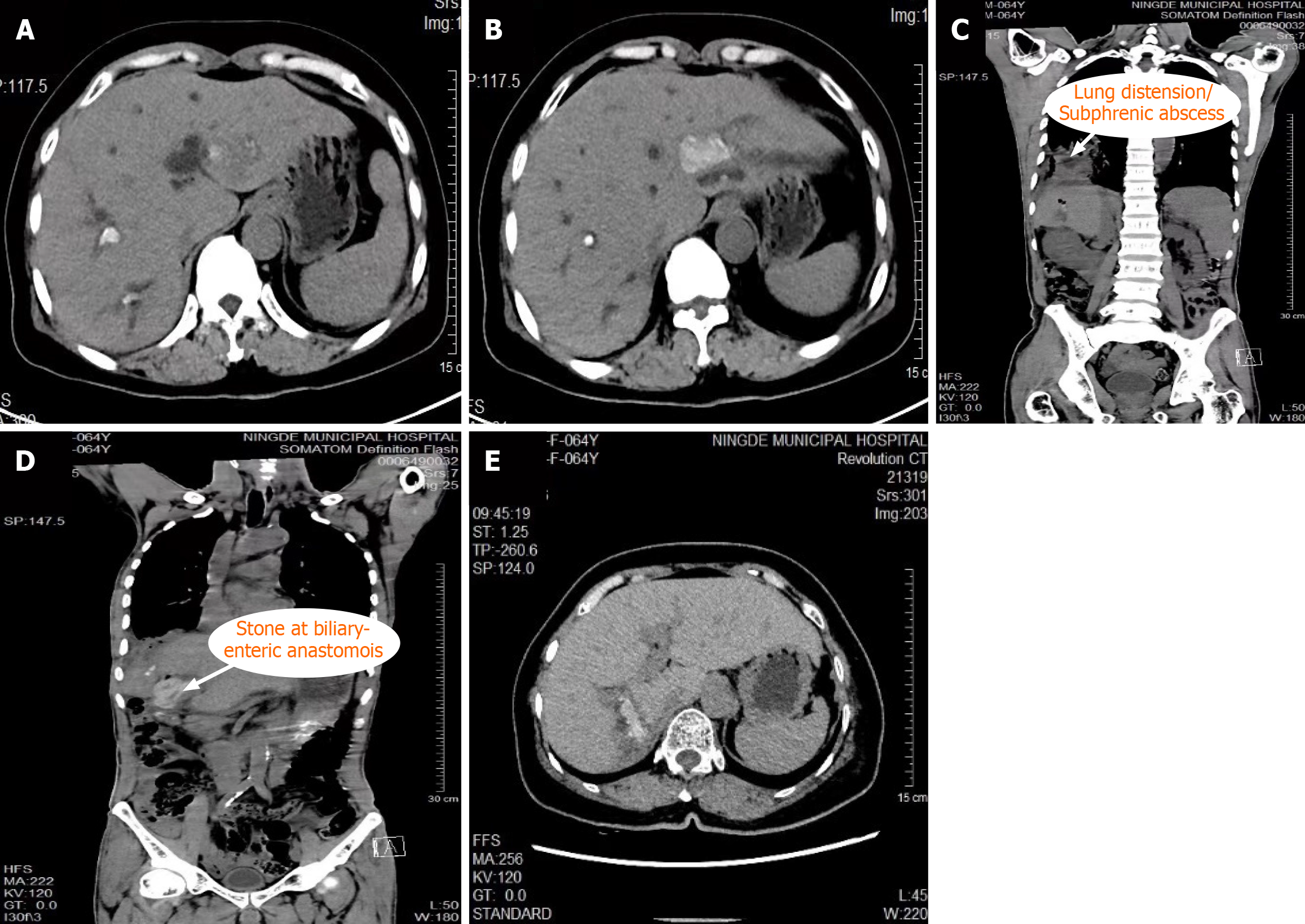

This retrospective study included 80 patients with complex hepatolithiasis who underwent surgery at Ningde Municipal Hospital, affiliated with Fujian Medical University, between January 2020 and August 2024. The patients met ≥ 1 of the following inclusion criteria: (1) Diffuse hepatolithiasis involving multiple segments (Figure 1A and B); (2) Recurrent cholangitis, liver or pulmonary abscess (Figure 1C); (3) Hepatic atrophy or anatomical distortion; (4) Biliary cirrhosis, portal hypertension, or cavernous transformation of the portal vein; (5) ≥ 1 prior hepatobiliary surgery, especially involving the hilum or bilioenteric anastomosis (Figure 1D); or (6) High or multiple bile duct strictures (Figure 1E). Exclusion criteria included isolated bile duct exploration; coexisting cholangiocarcinoma, or Child-Pugh class C liver function.

Patients were divided into the open surgery group (n = 40) and the laparoscopic surgery group (n = 40). At the time of admission, 38 patients in the laparoscopic group presented with symptoms such as acute cholangitis, acute pancreatitis, liver abscess, or pulmonary abscess, compared to 37 patients in the open surgery group. In the laparoscopic group, 35 patients had undergone more than one prior surgery, with a maximum of five surgeries, while in the open surgery group, 36 patients had undergone up to six surgeries. In addition to hepatolithiasis, all patients were diagnosed with other concomitant hepatobiliary diseases, including gallbladder stones, extrahepatic bile duct stones, hepatic atrophy, liver cirrhosis, and intrahepatic bile duct stenosis. Most patients in both groups exhibited intrahepatic bile duct stenosis.

Patients were allocated to either the laparoscopic or open surgery group based on the time period during which they received treatment, rather than by randomization. Most patients treated between 2020 and 2022 underwent open surgery, although a minority received laparoscopic procedures. Conversely, in 2023 and 2024, the majority of patients received laparoscopic surgery, with only a few undergoing open procedures. This temporal grouping reflects the institution’s progressive transition toward minimally invasive techniques. All patients met the inclusion criteria for complex hepatolithiasis, and the choice of surgical approach was guided by standardized preoperative imaging and clinical evaluation.

This research was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Ningde Municipal Hospital, Ningde Normal University, approval No. 20211009. Informed consent was acquired from all study participants and/or their legal guardians. All procedures adhered strictly to relevant ethical guidelines and regulations.

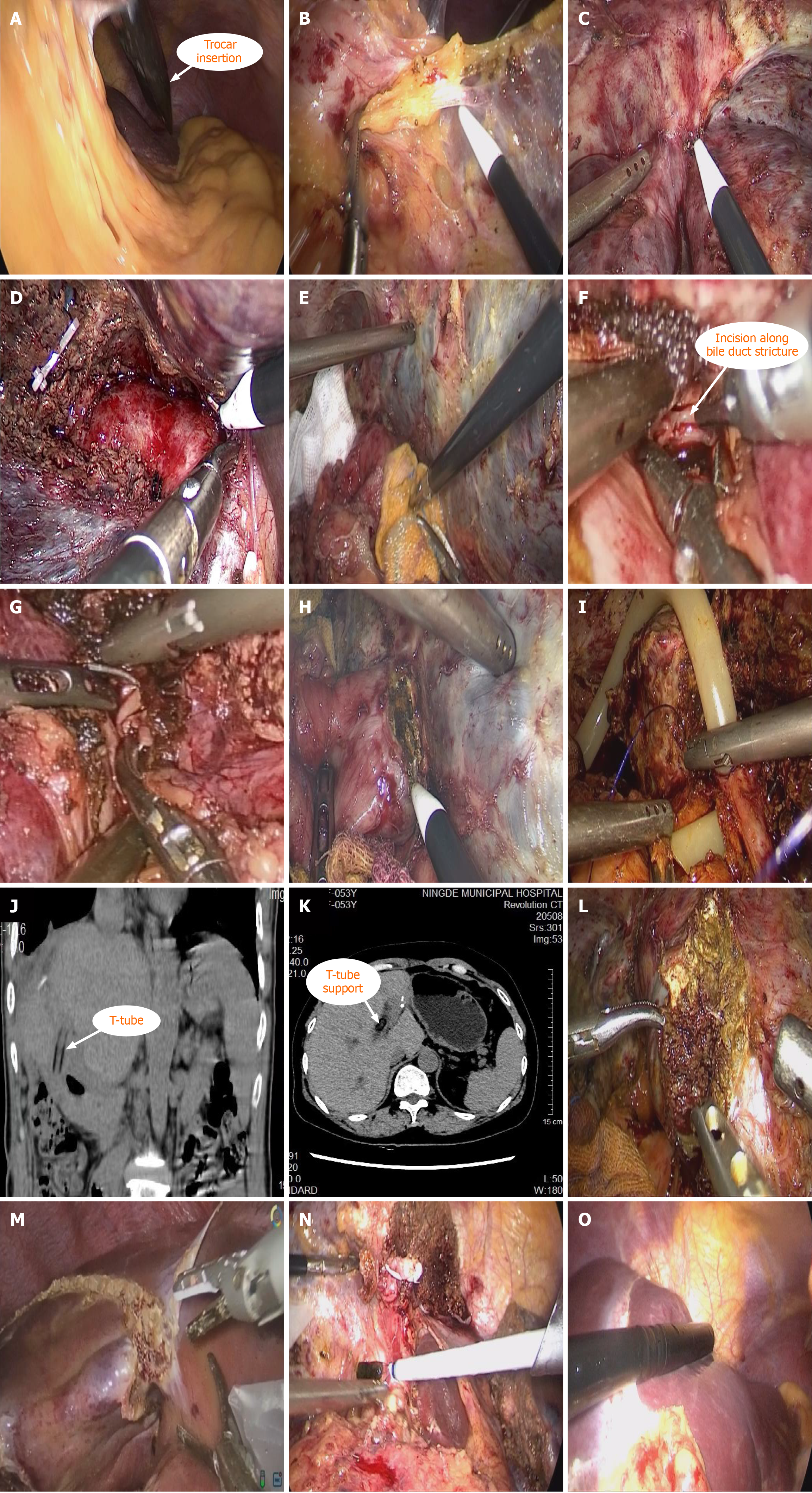

Adhesiolysis and hilum exposure: Patients with complex hepatolithiasis frequently present with dense intra-abdominal adhesions due to prior surgeries or chronic inflammation. These adhesions are often compounded by hepatic atrophy, deformation, or displacement, posing considerable challenges to surgical dissection (Figure 2A). Successful operative management hinges on meticulous adhesiolysis, precise identification of the hepatic hilum, and a thorough under

Following pneumoperitoneum establishment via a subumbilical port, additional trocars are strategically placed to optimize access. Adhesions are carefully divided in a stepwise fashion to avoid iatrogenic injury, particularly in cases where the gastrointestinal tract is firmly adhered to the liver capsule. Rather than aggressively seeking the hepatic hilum, dissection is conducted progressively along the visceral liver surface, using preoperative cross-sectional imaging to guide identification. In select cases, combined dissection through the round ligament and gallbladder fossa is required to adequately expose the hilum. When conventional landmarks are obscured, intraoperative indocyanine green fluorescence imaging or ultrasound is employed to assist in localizing critical structures.

In patients with multiple prior biliary interventions or biliobiliary fistulas, dense adhesions between the liver and diaphragm necessitate subcapsular dissection to preserve diaphragmatic integrity (Figure 2C).

Hilum dissection and stone removal: Dissection of the Glissonean pedicles is performed using a combination of sharp and blunt techniques, guided by the anatomical continuity of Laennec’s capsule. Intrahepatic stones are removed under direct visualization, with holmium laser lithotripsy applied in cases of impacted calculi (Figure 2D).

Prior to bile duct incision, iodine-soaked gauze is strategically placed around the duct to prevent intraperitoneal contamination by bile or dislodged stones (Figure 2E). A flexible cholangioscope is introduced to evaluate the function of the sphincter of Oddi and determine the necessity for bilioenteric reconstruction. The extent of ductal stricture is simultaneously assessed to guide decisions regarding ductoplasty or hepatic resection (Figure 2F and G).

In cases with proximal bile duct dilatation and distal stenosis, a longitudinal incision is made along the axis of the narrowed segment, followed by reconstruction using absorbable sutures to restore ductal patency. For patients with a history of bilioenteric anastomosis, posterior dissection is first undertaken to expose and safeguard the portal vein. The anastomosis is then opened; if stenotic, it is revised to ensure unobstructed biliary drainage (Figure 2H). The vertical limb of the T-tube is placed into the choledochoenterostomy via the common bile duct (Figure 2I-K).

This case illustrates a reoperation for recurrent hepatolithiasis with bilateral intrahepatic stone burden, managed successfully through a minimally invasive approach. This was the patient’s fifth surgical intervention, complicated by a biliary-bronchial fistula, pulmonary abscess, and biliary-enteric anastomotic stricture.

Liver parenchymal resection: Liver parenchymal resection represents one of the most technically demanding com

In cases with advanced intrahepatic strictures and poor drainage, anatomical resection of the affected liver territory is performed en bloc, encompassing both the obstructed biliary tree and the corresponding parenchyma. Chronic inflammation and stone-related ischemia often lead to regional atrophy and vascular distortion, complicating the use of traditional ischemic demarcation lines. In such instances, dilated bile ducts and preserved hepatic veins are used as anatomical landmarks for resection.

Prior to parenchymal resection, laparoscopic intraoperative ultrasound is routinely employed to delineate the extent of stones and map the positions of the hepatic veins (Figure 2O). This allows precise determination of the hepatic transection line, enabling the targeted removal of diseased liver tissue while maximizing the preservation of normal hepatic parenchyma. This was the patient’s third surgical procedure for hepatolithiasis complicated by hilar bile duct stricture.

The assessment criteria for this study include preoperative demographic data, as well as intraoperative and postoperative parameters: Surgical approach, intraoperative blood loss, Pringle maneuver time, surgical duration, postoperative hospital stay, stone clearance rate, final stone clearance rate, and postoperative complications. Postoperative complications were classified according to the standards set by the International Liver Surgery Study Group, with biliary leakage defined as a biliary concentration in the drainage fluid exceeding three times the serum bilirubin level 3 days or more after surgery. Residual stones were defined as bile duct stones detected within three months following hepatectomy. Follow-up protocol: Follow-up was conducted via telephone or outpatient visits. For the first three months post-surgery, patients were reviewed monthly using ultrasound or computed tomography scans and liver function tests. After the first three months, follow-up visits were scheduled every three months, and after one year, follow-up occurred every six months.

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 22.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States). Normality of continuous variables was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Variables that followed a normal distribution were expressed as mean ± SD and compared using the independent-sample t-test. Non-normally distributed variables were reported as median [interquartile range (IQR)] and compared using the Mann-Whitney U test. Categorical data are presented as frequencies (percentages), and comparisons were made using the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The required sample size was determined to ensure sufficient power to detect clinically significant differences between the laparoscopic and open surgery groups. Based on a pervious study, we estimated a medium effect size (Cohen’s d = 0.5) for differences[8]. With a significance level (α) of 0.05 and desired power of 80%, a total sample size of 64 patients (32 per group) was required. To account for potential dropouts and incomplete data, we enrolled 80 patients, which ensured sufficient statistical power.

The normality of continuous variables was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Only age followed a normal distribution (P > 0.05) and was analyzed using the Student’s t-test. In contrast, variables such as surgical time, intraoperative blood loss, Pringle maneuver time, body mass index, postoperative hospital stay, and follow-up duration exhibited non-normal distributions (P < 0.05). Therefore, these non-normally distributed variables were compared using the Mann-Whitney U test.

A total of 80 patients were included in the analysis, with 40 undergoing laparoscopic surgery and 40 undergoing open surgery. Baseline characteristics, including age, sex, body mass index, and comorbidities (e.g., hepatitis B, malnutrition, diabetes), were similar between the two groups (Table 1). The mean age was 52.7 ± 12.1 years in the laparoscopic group and 56.1 ± 12.9 years in the open group (P = 0.228). No statistically significant differences were observed in the prevalence of hepatic atrophy, biliary strictures, prior hepatobiliary procedures, or concurrent gallstones (all P > 0.05).

| Variable | Laparoscopic group (n = 40) | Open surgery group (n = 40) | χ2/t/Mann-Whitney U test | P value |

| Age (years, mean ± SD), (range) | 52.7 ± 12.1 (23.0-81.0) | 56.1 ± 12.9 (34.0-80.0) | -1.215 | 0.228 |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 24 (60.0) | 26 (65.0) | 0.213 | 0.644 |

| Male | 16 (40.0) | 14 (35.0) | - | - |

| BMI (kg/m2, IQR) | 20.0 (18.0-21.0) | 20.0 (19.0-22.5) | -0.998 | 0.318 |

| Hepatitis B | 8 (20.0) | 7 (17.5) | 0.082 | 0.775 |

| Malnutrition | 6 (15.0) | 8 (20.0) | 0.346 | 0.556 |

| Diabetes | 6 (15.0) | 7 (17.5) | 0.092 | 0.762 |

| Presentation | ||||

| Acute cholangitis | 37 (92.5) | 36 (90.0) | - | 1.0001 |

| Acute pancreatitis | 9 (22.5) | 8 (20.0) | 0.075 | 0.785 |

| Liver abscess | 12 (30.0) | 15 (37.5) | 0.503 | 0.478 |

| Lung abscess | 2 (5.0) | 1 (2.5) | - | 1.0001 |

| Previous operation | ||||

| Cholecystectomy | 34 (85.0) | 35 (87.5) | 0.105 | 0.745 |

| Bilioenteric anastomosis | 7 (17.5) | 7 (17.5) | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Exploration of bile duct | 35(87.5) | 33 (82.5) | 0.392 | 0.531 |

| Hepatectomy | 10 (25.0) | 11 (27.5) | 0.065 | 0.799 |

| Concomitant condition | ||||

| Gallbladder stones | 3 (7.5) | 4 (10.0) | - | 1.0001 |

| Extrahepatic biliary stones | 34 (85.0) | 33 (82.5) | 0.092 | 0.762 |

| Hepatic atrophy | 12 (30.0) | 15 (37.5) | 0.503 | 0.478 |

| Cirrhosis | 6 (15.0) | 7 (17.5) | 0.092 | 0.762 |

| Intrahepatic biliary stricture | 38 (95.0) | 38 (95.0) | - | 1.0001 |

Median surgical time was significantly longer in the laparoscopic group (250.0, IQR: 215.0-315.0 minutes vs 207.0, IQR: 185.8-255.0 minutes, P = 0.003). However, intraoperative blood loss and the duration of the Pringle maneuver did not differ significantly between the groups (P > 0.05). The laparoscopic group had significantly shorter postoperative hospital stays (median 9.0 days, IQR: 8.0-11.0) vs the open group (14.0 days, IQR: 12.0-17.0; P < 0.001). No significant differences were observed in the types of surgical resections or in the initial and final stone clearance rates (Table 2).

| Variables | Laparoscopic group (n = 40) | Open surgery group (n = 40) | χ2/Mann-Whitney U test | P value |

| Left lateral sectionectomy | 5 (12.5) | 5 (12.5) | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Periportal hepatectomy | 3 (7.5) | 3 (7.5) | - | 1.0001 |

| Left hepatectomy | 6 (15.0) | 3 (7.5) | - | 0.4811 |

| Right posterior segmentectomy | 5 (12.5) | 6 (15.0) | 0.105 | 0.745 |

| Right hepatectomy | 4 (10.0) | 4 (10.0) | - | 1.0001 |

| Left lateral sectionectomy + hilar cholangioplasty | 6 (15.0) | 7 (17.5) | 0.092 | 0.762 |

| Periportal hepatectomy + bilioenteric anastomosis | 4 (10.0) | 4 (10.0) | - | 1.0001 |

| Periportal hepatectomy + hilar cholangioplasty | 7 (17.5) | 8 (20.0) | 0.082 | 0.775 |

| Surgical time (minutes) | 250.0 (215.0-315.0) | 207.0 (185.8-255.0) | -2.984 | 0.003 |

| Intraoperative blood loss (mL, IQR) | 290.0 (200.0-350.0) | 300.0 (250.0-450.0) | -0.791 | 0.429 |

| Pringle maneuver time (minutes, IQR) | 35.0 (30.0-45.0) | 38.0 (25.0-45.0) | -0.445 | 0.656 |

| Postoperative hospital stay (days, IQR) | 9.0 (8.0-11.0) | 14.0 (12.0-17.0) | -5.545 | < 0.001 |

| Stone clearance | 31 (77.5) | 32 (80.0) | 0.075 | 0.785 |

| Choledochoscopic stone removal via T-canal sinus | 9 (22.5) | 8 (20.0) | 0.075 | 0.785 |

| Final stone clearance | 33 (82.5) | 34 (85.0) | 0.092 | 0.762 |

| Complications | 17 (42.5) | 18 (45.0) | 0.051 | 0.822 |

| Complication types | ||||

| Intra-abdominal bleeding | 3 (7.5) | 3 (7.5) | - | 1.0001 |

| Biliary leakage | 3 (7.5) | 4 (10.0) | - | 1.0001 |

| Wound infection | 2 (5.0) | 9 (22.5) | 5.165 | 0.023 |

| Pulmonary infection | 3 (7.5) | 5 (12.5) | - | 0.7121 |

| Pleural effusion | 8 (20.0) | 10 (25.0) | 0.287 | 0.592 |

| Abdominal infection | 3 (7.5) | 6 (15.0) | - | 0.4811 |

| Subphrenic abscess | 1 (2.5) | 2 (5.0) | - | 1.0001 |

| Residual stones | 7 (17.5) | 8 (15.0) | 0.092 | 0.762 |

Overall complication rates were similar between the groups: 42.5% in the laparoscopic group and 45.0% in the open group (P = 0.822). Common complications included biliary leakage, intra-abdominal bleeding, pulmonary infection, and pleural effusion, with no statistically significant differences observed for individual events except for wound infection (Table 2). Wound infection rates were significantly lower in the laparoscopic group compared to the open group (5.0% vs 22.5%, P = 0.023). Residual stones occurred in 17.5% of patients in the laparoscopic group and 15.0% in the open group (P = 0.762).

The follow-up duration was similar in both groups (P = 0.344). Rates of stone recurrence (25.0% vs 17.5%, P = 0.412), recurrent cholangitis (20.0% vs 25.0%, P = 0.592), and development of cholangiocarcinoma (7.5% vs 7.5%, P = 1.000) were comparable. One patient in the open surgery group died during follow-up; no deaths were recorded in the laparoscopic group (Table 3).

| Variable | Laparoscopic group (n = 40) | Open surgery group (n = 40) | χ2/ Mann-Whitney U test | P value |

| Follow-up duration (months), mean ± SD | 28.0 (20.0-30.8) | 28.5 (24.0-40.5) | -0.947 | 0.344 |

| Stone recurrence | 10 (25.0) | 7 (17.5) | 0.672 | 0.412 |

| Cholangitis | 8 (20.0) | 10 (25.0) | 0.287 | 0.592 |

| Cholangiocarcinoma | 3 (7.5) | 3 (7.5) | - | 1.0001 |

| Mortality | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.5) | - | 1.0001 |

This study supports the growing evidence that laparoscopic surgery, despite requiring significantly longer operative time (250.0 minutes vs 207.0 minutes), is a safe and effective alternative to open procedures for complex hepatolithiasis. The extended duration observed in laparoscopic cases reflects the technical demands of precise adhesiolysis, meticulous hilar dissection, and repeated cholangioscopic maneuvers under limited tactile feedback[9,10]. Importantly, this did not compromise safety: Laparoscopic surgery was associated with significantly lower wound infection rates (5.0% vs 22.5%) and shorter hospital stays (9.0 days vs 14.0 days), consistent with its minimally invasive nature.

Complex hepatolithiasis often entails anatomical distortion due to prior surgeries, biliary strictures, hepatic atrophy, or comorbid cirrhosis, contributing to high surgical complexity and risk[11,12]. Traditionally managed by open surgery, these cases are increasingly amenable to minimally invasive approaches, provided that patients are rigorously selected and advanced perioperative planning is employed[13]. In our cohort, no conversions to open surgery were required, underscoring the feasibility of a laparoscopic approach even in high-risk scenarios[14-16].

The surgical strategy emphasized Laennec’s capsule as a reliable anatomical landmark to facilitate bile duct exposure and segmental parenchymal resection. This technique, combined with intraoperative cholangioscopy and imaging modalities, enabled complete stone clearance in most cases. Although some patients required postoperative stone retrieval via T-tube, the final clearance rates did not differ significantly between the groups[17].

Preoperative planning remains essential. Multimodal imaging - such as contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography, and three-dimensional visualization - helps assess stone burden, vascular relationships, and residual liver volume, minimizing intraoperative risks. The presence of severe portal hypertension or cavernous transformation remains a relative contraindication, although carefully selected patients may still benefit from laparoscopic treatment. A multidisciplinary approach is crucial to optimize patient condition prior to surgery[18-20].

While initial resource utilization may be higher with laparoscopic surgery due to equipment costs and operative duration, these are likely offset by reduced complications, shorter hospitalization, and faster functional recovery - factors that may translate into cost-efficiency, particularly in high-volume centers.

Furthermore, as robotic-assisted surgery continues to evolve, its enhanced dexterity, precision, and three-dimensional visualization may offer additional advantages in managing anatomically complex cases of hepatolithiasis. Future studies should explore its role in extending the indications for minimally invasive hepatobiliary surgery.

This study has several limitations. It was retrospective, conducted at a single center, and all procedures were perfo

Laparoscopic management of complex hepatolithiasis, when guided by Laennec’s capsule and supported by rigorous patient selection and advanced surgical planning, is both feasible and effective. Although technically demanding, it offers meaningful benefits in recovery time and the complication profile. With further refinement and validation - particularly through randomized, multicenter trials - laparoscopic surgery may become a preferred approach in selected cases, potentially complemented by robotic-assisted techniques to enhance precision and control.

The authors would like to thank the staff of the Department of Hepatobiliary, Pancreatic and Splenic Surgery, Ningde Clinical Medicine College of Fujian Medical University, for their assistance in data collection and analysis.

| 1. | Motta RV, Saffioti F, Mavroeidis VK. Hepatolithiasis: Epidemiology, presentation, classification and management of a complex disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2024;30:1836-1850. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 17.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 2. | Ye YQ, Cao YW, Li RQ, Li EZ, Yan L, Ding ZW, Fan JM, Wang P, Wu YX. Three-dimensional visualization technology for guiding one-step percutaneous transhepatic cholangioscopic lithotripsy for the treatment of complex hepatolithiasis. World J Gastroenterol. 2024;30:3393-3402. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Patel J, Jones CN, Amoako D. Perioperative management for hepatic resection surgery. BJA Educ. 2022;22:357-363. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Troncone E, Mossa M, De Vico P, Monteleone G, Del Vecchio Blanco G. Difficult Biliary Stones: A Comprehensive Review of New and Old Lithotripsy Techniques. Medicina (Kaunas). 2022;58:120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Rennie O, Sharma M, Helwa N. Hepatobiliary anastomotic leakage: a narrative review of definitions, grading systems, and consequences of leaks. Transl Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024;9:70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Javed H, Olanrewaju OA, Ansah Owusu F, Saleem A, Pavani P, Tariq H, Vasquez Ortiz BS, Ram R, Varrassi G. Challenges and Solutions in Postoperative Complications: A Narrative Review in General Surgery. Cureus. 2023;15:e50942. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Potharazu AV, Gangemi A. Indocyanine green (ICG) fluorescence in robotic hepatobiliary surgery: A systematic review. Int J Med Robot. 2023;19:e2485. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Lakens D. Calculating and reporting effect sizes to facilitate cumulative science: a practical primer for t-tests and ANOVAs. Front Psychol. 2013;4:863. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3596] [Cited by in RCA: 5587] [Article Influence: 143.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Luo B, Wu SK, Zhang K, Wang PH, Chen WW, Fu N, Yang ZM, Hao JC. Development of a novel difficulty scoring system for laparoscopic liver resection procedure in patients with intrahepatic duct stones. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2024;16:3133-3141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Chen ZL, Fu H. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, endoscopic papillary balloon dilation, and laparoscopic hepatectomy for intra- and extrahepatic bile duct stones. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2025;17:100544. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Wei B, Huang Z, Tang C. Optimal Treatment for Patients With Cavernous Transformation of the Portal Vein. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022;9:853138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Liang SY, Lu JG, Wang ZD. Imaging misdiagnosis and clinical analysis of significant hepatic atrophy after bilioenteric anastomosis: A case report. World J Clin Cases. 2023;11:7234-7241. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Liu YY, Li TY, Wu SD, Fan Y. The safety and feasibility of laparoscopic approach for the management of intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile duct stones in patients with prior biliary tract surgical interventions. Sci Rep. 2022;12:14487. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Ye YQ, Li PH, Wu Q, Yang SL, Zhuang BD, Cao YW, Xiao ZY, Wen SQ. Evolution of surgical treatment for hepatolithiasis. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2024;16:3666-3674. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Li Z, Zhang Y, Chen Z, Chen J, Hou H, Wang C, Lu Z, Wang X, Geng X, Liu F. Correlation analysis and recurrence evaluation system for patients with recurrent hepatolithiasis: a multicentre retrospective study. Front Digit Health. 2024;6:1510674. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Tabibian N, Swehli E, Boyd A, Umbreen A, Tabibian JH. Abdominal adhesions: A practical review of an often overlooked entity. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2017;15:9-13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 137] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Sasturkar SV, Agrawal N, Arora A, Kumar MPS, Kilambi R, Thapar S, Chattopadhyay TK. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy in patients with portal cavernoma without portal vein decompression. J Minim Access Surg. 2021;17:351-355. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Cao YW, Lin JL, Chen DQ, Ding ZW, Li PH, Li RQ, Ye YQ. DynaCT biliary reconstruction via a 3D C-arm cholangiography system: clinical application in hepatolithiasis. Br J Radiol. 2025;98:1428-1435. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Huang Z, Zeng S, Zeng X, Wen S, Zhou Y, Cai P, Zhong H, Liu Z, Xiang N, Zhou C, Fang C, Zeng N. Efficacy of hepatectomy for hepatolithiasis using 3D visualization combined with ICG fluorescence imaging: A retrospective cohort study. World J Surg. 2024;48:1242-1251. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Guo Q, Chen J, Pu T, Zhao Y, Xie K, Geng X, Liu F. The value of three-dimensional visualization techniques in hepatectomy for complicated hepatolithiasis: A propensity score matching study. Asian J Surg. 2023;46:767-773. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/