Published online Nov 27, 2025. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v17.i11.110185

Revised: July 5, 2025

Accepted: November 7, 2025

Published online: November 27, 2025

Processing time: 180 Days and 23.7 Hours

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is increasingly recognized not only for its immediate obstetric complications but also for its long-term metabolic consequ

Core Tip: Gestational diabetes mellitus does not only affect maternal glucose metabolism, but it can also program lifelong metabolic vulnerabilities in the offspring. This article emphasizes the underappreciated role of the maternal liver as a metabolic sensor that detects pregnancy-related physiological stress and modulates systemic signals accordingly. When impaired by gestational diabetes mellitus, the maternal liver becomes a source of maladaptive endocrine, inflammatory, and metabolic cues that are transmitted to the fetus. These signals can reprogram fetal liver development and increase the risk of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and type 2 diabetes mellitus in later life. Recognizing the liver’s central role in this process opens new avenues for preventive and therapeutic strategies targeting both maternal and offspring health.

- Citation: Abdalla MMI, Ismail-Khan M. Liver as a metabolic sensor in gestational diabetes: Implications for offspring’s liver and diabetes risk. World J Hepatol 2025; 17(11): 110185

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v17/i11/110185.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v17.i11.110185

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM), defined as glucose intolerance with onset or first recognition during pregnancy, affects up to 15% of pregnancies globally and is rising alongside increasing rates of obesity and metabolic syndrome among reproductive-age women[1]. While GDM is often transient and resolves postpartum, it is now widely regarded as a powerful predictor of future cardiometabolic disease in both the mother and her child[2,3]. Longitudinal studies and mechanistic models consistently demonstrate that in utero exposure to GDM confers elevated risks of obesity, insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) in offspring. This is a process und

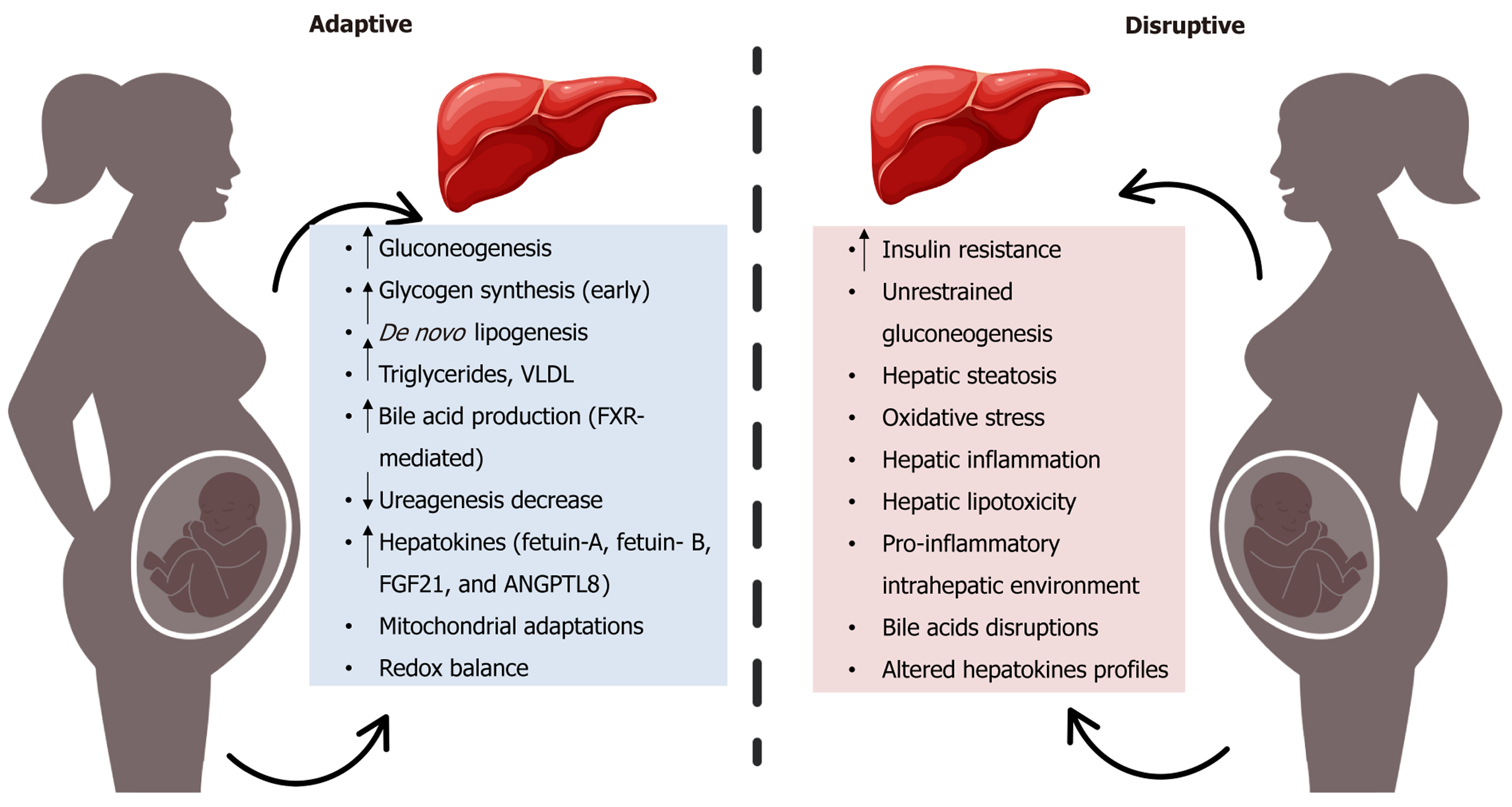

Among the numerous organs involved in the complex metabolic reprogramming of pregnancy, the maternal liver emerges as a pivotal yet underexplored regulator. In healthy gestation, the liver undergoes finely coordinated ada

However, in pregnancies complicated by GDM, these hepatic adaptations become pathologically disrupted. Women with GDM exhibit early-onset hepatic insulin resistance, hypertriglyceridemia, and often subclinical steatosis. These alterations are detectable as early as the first trimester, evidenced by elevated hepatic enzymes such as alanine ami

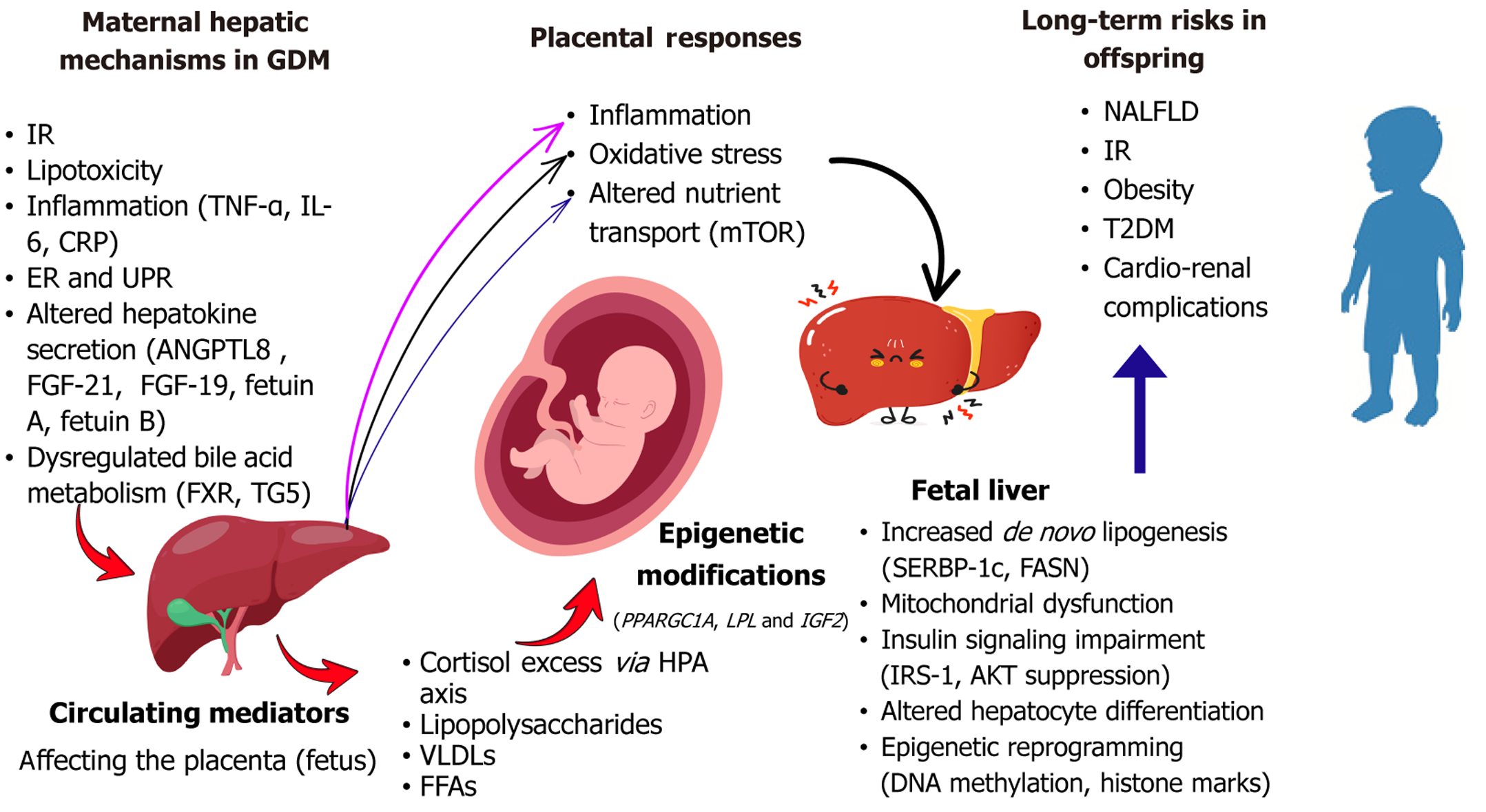

Emerging research reframes the maternal liver not just as a passive responder to metabolic stress, but as a metabolic sensor and intergenerational signal integrator. In the setting of GDM, dysregulated hepatic output modifies the int

Large prospective cohort studies, such as hyperglycemia and adverse pregnancy outcome-follow-up study and exploring perinatal outcomes among children, reinforce these observations. Offspring of GDM pregnancies demonstrate increased visceral adiposity, hepatic steatosis, and insulin resistance, effects often independent of postnatal body mass index (BMI) or lifestyle[21-23]. Furthermore, maternal hepatic biomarkers such as fetuin-A and FGF21 are increasingly associated with offspring outcomes ranging from lipid dysregulation to impaired glucose handling in childhood[24].

Despite these findings, the maternal liver remains relatively underrepresented in GDM research, which has tra

This article addresses that gap by repositioning the maternal liver as a central regulator of intergenerational metabolic programming in GDM. It begins by outlining the physiological hepatic adaptations of pregnancy and then explores how these are disrupted in GDM. The review critically examines key mechanistic pathways, including hepatokine signaling, dysregulated lipid metabolism, inflammatory cascades, and epigenetic remodeling, through which maternal liver dysfunction influences fetal liver development and long-term metabolic risk. Drawing on both human cohort studies and experimental animal models, the review offers a new conceptual framework in which the maternal liver is not just a metabolic effector, but a central architect of intergenerational health or disease.

The maternal liver plays a pivotal role in orchestrating the metabolic adaptations required to support a healthy pregnancy. Far from being a passive metabolic depot, the liver actively senses and responds to hormonal, nutritional, and physiological cues. This dynamic regulation ensures a balance between maternal metabolic needs and the increasing demands of the developing fetus. Broadly, the liver’s role evolves over the course of pregnancy from promoting nutrient storage and anabolic processes in early gestation to mobilizing energy substrates during the later stages to support rapid fetal growth[8].

During early gestation, the liver promotes glycogen synthesis and storage, largely driven by elevated estrogen and insulin levels. As pregnancy advances, maternal peripheral tissues such as skeletal muscle and adipose tissue develop insulin resistance, a physiological adaptation that spares glucose for the fetus. In response, hepatic gluconeogenesis is upregulated to maintain maternal euglycemia and meet fetal glucose demands, particularly during fasting[3,8,25].

Concurrently, hepatic lipid metabolism undergoes substantial remodeling. De novo lipogenesis increases, acco

Beyond glucose and lipids, the liver also adjusts amino acid metabolism to prioritize fetal protein synthesis. Urea

The liver’s endocrine function is critical during pregnancy. It secretes hepatokines, including fetuin-A, FGF21, and ANGPTL8 that regulate systemic insulin sensitivity, lipid oxidation, and placental nutrient exchange[35,36]. Additionally, the hepatic synthesis of hormone-binding globulins, such as sex hormone-binding globulin and corticosteroid-binding globulin, ensures balanced hormone bioavailability in both maternal and fetal compartments[37]. Moreover, mito

In GDM, the finely balanced metabolic functions of the maternal liver become pathologically dysregulated. GDM exacerbates the physiological insulin resistance of pregnancy, particularly within hepatic tissues, where impaired insulin signaling leads to unrestrained gluconeogenesis and elevated fasting glucose levels. This hyperglycemic environment contributes to fetal overexposure to glucose and fuels macrosomia and metabolic programming[41,42].

Hepatic lipid handling is similarly dysregulated. Increased lipogenesis, combined with impaired fatty acid oxidation, promotes hepatic triglyceride accumulation and steatosis, as reflected in elevated ALT and GGT concentrations detectable in early pregnancy[11,43,44]. Mitochondrial remodeling is also compromised, contributing to oxidative stress, reactive oxygen species accumulation, and lipid peroxidation, all of which exacerbate hepatic inflammation and lipotoxicity[45,46].

Maternal obesity, frequently coexisting with GDM, amplifies hepatic dysfunction. This dual burden results in a pro-inflammatory intrahepatic environment, marked by elevated IL-6, CRP, while protective adiponectin is reduced. This imbalance further impairs hepatic insulin sensitivity and accelerates intrahepatic inflammation and dysfunction[14,45,47].

Disruptions in bile acid homeostasis and hormonal regulation also contribute to metabolic deterioration. Impaired signaling via FXR and Takeda G-protein-coupled receptor 5 (TGR5), along with increased hepatic expression of 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 (11β-HSD1), enhances local cortisol activation and promotes systemic and fetal insulin resistance[32,48,49].

Endocrine dysfunction of the liver becomes evident through altered hepatokine profiles. In GDM, fetuin-A levels are elevated, while FGF21 and ANGPTL8 levels are often reduced[9,35]. These changes worsen maternal insulin resistance and dyslipidemia, disrupt placental nutrient transport, and may influence fetal gene expression related to lipid storage and glucose metabolism[50].

Emerging evidence suggests that the fetal liver may respond to these maladaptive signals in a sex-specific manner. Male fetuses appear particularly vulnerable to lipid accumulation and hepatic insulin resistance in the context of maternal GDM[21]. Additionally, the gut-liver axis has emerged as a potential contributor, where alterations in maternal mic

Taken together, these findings illustrate how GDM transforms the maternal liver from a responsive metabolic integrator into a source of maladaptive signaling. This hepatic dysfunction not only worsens maternal glycemic and lipid profiles but also acts as a transmitter of endocrine, inflammatory, and nutritional stressors that program fetal liver development and elevate long-term metabolic risk in the offspring. Figure 1 visually contrasts the physiological hepatic adaptations of pregnancy with the pathological derangements induced by GDM, providing a framework for under

In pregnancies affected by GDM, maternal hepatic function becomes dysregulated, giving rise to endocrine, metabolic, and inflammatory disturbances that may program the developing fetus for long-term cardiometabolic vulnerability. A growing body of evidence supports the role of the maternal liver as a key transmitter of metabolic stress signals to the fetus, through a range of mechanistic pathways that are now being elucidated with increasing molecular precision. This section presents a comprehensive analysis of these pathways, with emphasis on their molecular underpinnings, phy

Hepatokines are liver-derived proteins that influence systemic metabolic regulation. In GDM, their altered secretion profiles reflect underlying hepatic dysfunction and contribute to fetal metabolic programming. Elevated levels of fetuin-A and fetuin-B, frequently observed in GDM, impair insulin signaling through toll-like receptor 4-mediated inhibition of insulin receptor substrate-1 (IRS-1) phosphorylation. Fetuin-B is also elevated in cord blood of neonates born to GDM mothers, correlating with increased low-density lipo

FGF21, an adaptive hepatokine induced by metabolic stress, exhibits an inconsistent pattern in GDM. While some studies report elevated maternal FGF21 Levels, others suggest hepatic FGF21 resistance due to reduced β-Klotho co-receptor expression and impaired downstream signaling via extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha pathways[56-58]. Similarly, ANGPTL8, a regulator of lipo

These hepatokine imbalances may cross the placenta or alter placental nutrient transport, collectively promoting excess nutrient storage and lipogenesis in fetal tissues. This environment contributes to early adiposity, hepatic steatosis, and insulin resistance in the offspring.

In a healthy pregnancy, the maternal liver adapts to support fetal growth by enhancing de novo lipogenesis and increasing lipoprotein production. However, in GDM, these processes become pathologically dysregulated, resulting in excessive lipid delivery to the fetus and altered fetal liver development[61].

Hepatic insulin resistance in GDM upregulates sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1c (SREBP-1c), a transc

This hepatic lipid overload contributes to maternal hypertriglyceridemia, driven by increased hepatic secretion of VLDLs and reduced clearance of circulating lipids due to insulin-resistant adipose tissue. Elevated maternal triglycerides are hydrolyzed by placental LPL, releasing FFAs that readily cross the placenta. This results in excessive lipid accumulation in fetal tissues, particularly the liver, where it contributes to hepatic steatosis and may impair mitochondrial function and insulin sensitivity postnatally[5].

Fetal exposure to excess lipids also enhances lipogenic gene expression through increased hepatic activation of carbohydrate response element-binding protein and SREBP-1c, setting the stage for NAFLD in early life. Neonatal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies have confirmed increased intrahepatic lipid content in infants born to mothers with GDM, even in those with normal birth weight, suggesting that altered hepatic lipid metabolism operates inde

However, conflicting evidence exists regarding the magnitude and clinical impact of these lipid alterations. While several studies report strong associations between third-trimester maternal triglyceride levels and large-for-gestational-age births, others have found only weak or non-significant relationships when adjusting for maternal BMI and glycemic control[64,66,68]. Moreover, some investigations suggest that lipid transfer may be modulated by placental adaptations, such as altered expression of fatty acid transport proteins and CD36, which vary with maternal metabolic status and fetal sex, introducing further variability in outcomes. Adding to the complexity, not all fetuses respond similarly to lipid overexposure. Evidence from sex-specific analyses indicates that male fetuses may exhibit greater hepatic lipid accumulation and insulin resistance than females under comparable maternal metabolic conditions, potentially due to differential placental lipid handling or fetal hepatic receptor expression patterns[69-71].

Thus, while GDM is clearly associated with enhanced maternal hepatic lipogenesis and increased fetal lipid exposure, the downstream effects on fetal liver development are modulated by several variables, including maternal adiposity, placental transporter activity, fetal sex, and epigenetic responses. These factors may account for inconsistencies across studies and highlight the need for mechanistic research using standardized definitions, longitudinal sampling, and tissue-specific analyses.

Insulin signaling in the maternal liver is central to glucose regulation during pregnancy. Under physiological conditions, hepatic insulin binding activates IRS-1 and downstream protein kinase B (AKT) phosphorylation, suppressing gluconeogenesis via inhibition of forkhead box protein O1 and its targets, including phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase and glucose-6-phosphatase[72]. In GDM, this cascade is blunted by hepatic insulin resistance, resulting in persistent glucose production despite elevated insulin levels[2]. Consequently, maternal hyperglycemia ensues, and since glucose crosses the placenta via facilitated diffusion, the fetus is exposed to elevated glucose levels[73]. The ensuing maternal hyper

GDM also disrupts hepatic and placental nutrient-sensing networks. Chronic nutrient excess and inflammation inhibit AMP-activated protein kinase and activate mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR), shifting cellular metabolism toward lipogenesis and protein synthesis. In placental tissues, heightened mTOR activity increases nutrient transporter ex

These molecular alterations are supported by transcriptomic studies showing upregulation of lipogenic genes and reduced expression of antioxidant defenses in GDM-exposed fetal livers[77]. Placental samples from such pregnancies consistently demonstrate enhanced mTOR signaling[78]. However, heterogeneity remains: Some women with lean GDM phenotypes or early intervention maintain preserved hepatic insulin sensitivity[79], and mTOR suppression has been observed in placentas from growth-restricted GDM pregnancies. Furthermore, while most investigations show mTOR upregulation in the placenta, others have identified suppressed mTOR signaling in growth-restricted fetuses of GDM mothers, indicating that fetal growth dynamics and placental pathology may modulate these pathways differentially[80].

Such variability highlights the multifactorial nature of hepatic and placental dysfunction in GDM, shaped by maternal adiposity, timing of diagnosis, treatment adequacy, and fetal sex. Clarifying the relative contributions of maternal hepatic vs placental nutrient sensing in shaping fetal liver development requires targeted, tissue-specific models and longitudinal studies.

Beyond insulin resistance and lipid dysregulation, hepatic inflammation and oxidative stress represent key amplifiers of metabolic dysfunction in GDM. While pregnancy is associated with a mild physiological inflammatory state, GDM intensifies this response, particularly in the liver and adipose tissue. The maternal liver, acting as both a metabolic and immunologic organ, becomes a source of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-α, IL-6, and CRP, which can disrupt insulin signaling and placental function[81].

Elevated IL-6 and tumor necrosis factor-α have been observed in maternal serum, cord blood, and placental tissue from GDM pregnancies, suggesting transplacental propagation of inflammation. IL-6, in particular, has been shown to interfere with fetal hepatic insulin signaling and lipid metabolism. Within the maternal liver, inflammation activates nuclear factor nuclear factor kappa B and c-Jun N-terminal kinase signaling, which promote serine phosphorylation of IRS-1, further impairing insulin responsiveness[82,83].

Simultaneously, oxidative stress is exacerbated by impaired mitochondrial lipid oxidation and excess substrate flux. In experimental models of GDM, the maternal liver exhibits elevated markers of oxidative stress such as malondialdehyde and 4-hydroxynonenal alongside reduced expression of antioxidant enzymes like superoxide dismutase and catalase[45,46]. These imbalances are also reflected in placental and fetal liver tissues, supporting a model of systemic oxidative pro

However, findings are not uniform. Some studies report no significant elevations in inflammatory markers in well-managed or diet-controlled GDM, and oxidative stress levels can be influenced by coexisting factors such as maternal obesity, nutrient deficiencies, or environmental exposures[85]. Furthermore, it remains unclear whether fetal oxidative injury stems directly from maternal hepatic dysfunction or is mediated via placental inflammation and barrier disruption[86,87].

Taken together, inflammation and oxidative stress form a self-reinforcing loop that disrupts maternal hepatic metabolism and influences fetal hepatic development. Their combined effects exacerbate insulin resistance, promote hepatic steatosis, and alter redox-sensitive transcriptional programs in fetal tissues. Yet, the degree of disruption may vary depending on maternal phenotype, glycemic control, and gestational age at diagnosis. Disentangling the direct hepatic origins of these effects from systemic metabolic and placental mediators remains an important area for future study, with implications for targeted antioxidant and anti-inflammatory therapies during high-risk pregnancies.

Among the most enduring consequences of maternal liver dysfunction in GDM is the epigenetic and transcriptomic reprogramming of the developing fetal liver, which shapes long-term metabolic trajectories. Epigenetic modifications, including DNA methylation, histone modifications, and non-coding RNA regulation serve as mechanisms through which maternal metabolic cues induce long-term changes in gene expression without altering the DNA sequence. In the context of GDM, a hyperglycemic, lipotoxic, and inflammatory intrauterine environment may modulate fetal chromatin structure and transcriptional landscapes in a way that predisposes offspring to insulin resistance, hepatic steatosis, and cardio

Human studies have consistently shown differential DNA methylation patterns in cord blood and placental tissues from GDM pregnancies. Key metabolic genes involved in mitochondrial function, lipid metabolism, and insulin sensitivity, including PPARGC1A, LPL, and IGF2 exhibit altered methylation states. For instance, hypomethylation of PPARGC1A, a regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis and oxidative metabolism, has been observed in fetal hepatic tissue and cord blood, suggesting early-life impairments in energy handling[19,88-90]. These epigenetic changes align with transcriptomic data showing increased expression of lipogenic genes such as SREBP-1c, FASN and reduced expression of antioxidant enzymes in the GDM-exposed fetal liver[62,77].

In addition, histone modifications further shape transcriptional responses. Experimental models indicate that maternal hyperglycemia increases histone acetylation at loci controlling gluconeogenesis, such as H3K9ac at PEPCK and G6Pase, sustaining elevated hepatic glucose production into postnatal life[90-93]. While these findings are compelling, histone modification patterns in human fetal liver remain understudied due to limited tissue access.

Non-coding RNAs, particularly microRNAs (miRNAs), also play a significant role in this reprogramming. Altered levels of miR-122, miR-29a, and miR-126 have been detected in cord blood and placental exosomes from GDM pre

Despite these advances, several critical gaps remain. First, the causality between observed epigenetic modifications and long-term metabolic outcomes has not been firmly established in humans. While animal studies demonstrate that maternal hyperglycemia can directly induce hepatic DNA methylation changes that persist into adulthood, translating these findings to human fetal programming is complex. Second, it is not yet clear whether these epigenetic alterations are directly induced by maternal hepatic dysfunction or are secondary to systemic metabolic changes[88,90]. Given the centrality of the liver in metabolic sensing and signaling, it is plausible that hepatic stressors such as increased reactive oxygen species production or altered hepatokine secretion mediate these epigenetic effects via circulating signals, but definitive mechanistic links remain to be elucidated.

Furthermore, the reversibility of these epigenetic marks remains an open question. Some studies suggest that postnatal interventions, including diet and physical activity may partially normalize epigenetic alterations, offering hope for mitigating long-term risk[96,97]. However, the durability and plasticity of these changes, particularly those established during late gestation, require further exploration.

Taken together, GDM-induced maternal liver dysfunction can leave lasting molecular imprints on the fetal liver via epigenetic and transcriptomic reprogramming. These modifications may underpin increased susceptibility to insulin resistance, NAFLD, and metabolic syndrome later in life. Future longitudinal studies using integrated multi-omics approaches are essential to disentangle maternal hepatic-specific signals from systemic and placental influences and to identify biomarkers of modifiable vs permanent reprogramming.

Emerging evidence highlights the role of the gut-liver-placenta axis in mediating GDM’s effects on the fetus. The maternal gut microbiome undergoes pronounced changes during GDM, beyond the typical shifts seen in normal pregnancy. Most studies report that GDM is associated with gut dysbiosis characterized by reduced microbial diversity and an increase in opportunistic gram-negative bacteria. This dysbiosis can compromise intestinal barrier integrity, leading to increased translocation of bacterial endotoxins such as lipopolysaccharide into the maternal bloodstream, a phenomenon termed metabolic endotoxemia[98].

Lipopolysaccharide activates hepatic Kupffer cells via toll-like receptor 4, triggering inflammatory cascades that further impair hepatic insulin sensitivity[99]. In parallel, beneficial microbial metabolites such as short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), including acetate, propionate, and butyrate are often depleted in GDM. SCFAs normally act through G-protein coupled receptors 41/43 to suppress inflammation and enhance insulin sensitivity. Their depletion removes a key regulatory buffer and contributes to systemic and hepatic dysfunction[100].

Importantly, SCFAs and other microbial metabolites can reach the placenta and fetal circulation. Experimental studies suggest that maternal SCFA depletion leads to reduced fetal signaling through SCFA-responsive pathways, altering hepatic energy metabolism and inflammatory tone[101]. In GDM placentas, decreased expression of SCFA receptors and increased histone deacetylase activity have been documented, contributing to a more pro-inflammatory and metabolically stressed microenvironment[102].

Rodent models provide compelling support for this axis. High-fiber diets that enrich SCFAs-producing bacteria such as Lachnospiraceae have been shown to restore gut barrier integrity, reduce maternal and placental inflammation, and prevent GDM onset. Supplementation with butyrate alone has yielded similar benefits, improving placental function and fetal metabolic outcomes[101,103]. However, mechanistic data in humans remain limited, and it is unclear whether SCFA-related fetal programming is directly mediated by maternal hepatic changes or secondarily through placental and systemic effects. Further, variability in maternal diet, antibiotic exposure, and host genotype may modulate microbiota com

Hence, the gut-liver-placenta axis represents a promising but underexplored pathway linking maternal metabolic health to fetal development. Dysbiosis-associated endotoxemia and SCFAs deficiency may potentiate hepatic inflammation, disrupt placental function, and contribute to fetal liver programming. Longitudinal human studies incorporating microbial profiling, metabolomics, and placental analysis are needed to elucidate this axis and inform microbiota-targeted interventions during pregnancy.

Bile acids (BAs) are not only digestive agents but also potent endocrine signals that regulate hepatic glucose and lipid metabolism. In pregnancy, BAs signaling through FXR and TGR5 is modulated to accommodate changing metabolic demands. Under normal conditions, intestinal FXR activation induces fibroblast growth factor 19 (FGF19), which suppresses hepatic BAs synthesis via CYP7A1 and limits gluconeogenesis. During late gestation, FXR activity is physiologically downregulated to facilitate increased lipid absorption and energy availability for the fetus. In GDM, this adaptive suppression is exaggerated. Studies have reported significantly reduced maternal FGF19 levels, correlating with elevated hepatic glucose production and worsened insulin resistance[104,105].

Concurrently, FGF21, a stress responsive hepatokine often rises in circulation but shows limited efficacy, possibly due to receptor desensitization or downstream signaling defects, as discussed earlier[57,106].

The influence of altered BA signaling extends beyond the maternal system. Both FXR and TGR5 are expressed in the placenta, and excessive maternal BAs can cross the placenta and disrupt fetal metabolic homeostasis[107]. In animal models, elevated maternal BAs impair fetal β-cell function, induce lipid accumulation, and contribute to hepatic dys

Pharmacological activation of FXR or FGF19 pathways has shown promise in improving glycemic control and hepatic insulin sensitivity in preclinical GDM models[110]. However, the safety of such interventions in pregnancy remains unestablished, and their impact on fetal development, particularly hepatic and placental maturation, requires careful eva

Collectively, exaggerated suppression of FXR-FGF19 signaling in GDM contributes to dysregulated hepatic glucose output and systemic insulin resistance. Disrupted BAs signaling may also affect fetal liver development via placental cross-talk and direct metabolic interference. Further studies are needed to clarify the extent of fetal exposure to BA derivatives in GDM and assess the therapeutic viability of targeting these pathways in pregnancy.

Metabolic overload in GDM induces endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress in the maternal liver, triggering the unfolded protein response (UPR), a cellular adaptation aimed at restoring proteostasis. The UPR is activated via three major signaling arms: Inositol-requiring enzyme 1α, protein kinase RNA-like ER kinase, and activating transcription factor 6. In GDM, prolonged activation of these pathways leads to downstream c-Jun N-terminal kinase and nuclear factor nuclear factor kappa B signaling, which amplify inflammation and promote serine phosphorylation of IRS-1, impairing insulin signaling[63,111].

Elevated markers of ER stress such as C/EBP homologous protein and glucose-regulated protein 78 have been detected in maternal serum and placental tissue, even in well-controlled GDM cases. Within the placenta, ER stress contributes to impaired glucose and amino acid transport, increased apoptosis in syncytiotrophoblasts, and disrupted endocrine sign

Notably, experimental studies suggest that ER stress in GDM is not solely driven by hyperglycemia; instead, it requires coexisting lipotoxicity or oxidative stress to reach pathological thresholds. This multifactorial origin aligns with ob

Therapeutically, chemical chaperones such as tauroursodeoxycholic acid have shown efficacy in reducing ER stress and improving insulin sensitivity in preclinical models of GDM. However, human trials are limited, and placental safety profiles remain uncertain. Additionally, not all placentas from GDM pregnancies exhibit overt ER dilation or stress marker elevation, particularly in mild or diet-controlled cases[114,115].

Altogether, ER stress functions as both a mediator and amplifier of hepatic and placental dysfunction in GDM. Its interplay with inflammation, lipotoxicity, and nutrient signaling suggests that targeting the UPR may offer a promising strategy to restore maternal metabolic balance and protect fetal development. Future studies should stratify GDM populations by phenotype and severity to determine when and where ER stress-targeted interventions are most appr

Extracellular vesicles (EVs), particularly exosomes, have emerged as key mediators of intercellular communication during pregnancy. In GDM, alterations in the quantity and molecular cargo of maternal EVs may contribute to fetal metabolic programming by transferring regulatory RNAs and proteins that influence insulin signaling, lipid metabolism, and inf

Exosomes released from hepatocytes and syncytiotrophoblasts carry miRNAs and long non-coding RNAs capable of modulating gene expression in distal tissues. Studies have identified dysregulated levels of miR-122, miR-29a, and miR-126-3p in circulating exosomes from GDM pregnancies. These miRNAs are known to regulate hepatic pathways such as the AMP-activated protein kinase and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/AKT signaling axes, with downstream effects on gluconeogenesis, lipogenesis, and insulin sensitivity[118,119].

Importantly, EVs can cross the placental barrier, delivering their contents into fetal circulation. In animal models, fetal exposure to GDM-derived exosomes has been shown to alter hepatic gene expression, particularly genes involved in lipid storage and glucose metabolism. These findings suggest that maternal EVs serve as non-genomic vectors that transmit metabolic stress signals from the mother to the fetus[116,120].

Nevertheless, human data remain limited and heterogeneous. Challenges in tracing the tissue origin of circulating EVs and differences in EV isolation methods contribute to inconsistent findings across studies. Some investigations report upregulation of specific miRNAs, while others note their suppression[120,121]. These discrepancies may reflect dif

Together, these observations support the role of EVs as a mechanistic link between maternal hepatic dysfunction and fetal metabolic reprogramming. However, further studies are needed to determine the stability, specificity, and functional impact of GDM-related EVs on fetal liver development, as well as their potential as biomarkers or therapeutic targets.

Dysregulation of the maternal hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in GDM may further contribute to fetal metabolic programming by increasing fetal exposure to glucocorticoids[123,124]. This axis is regulated in part by the placental and hepatic expression of 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase enzymes; 11β-HSD1, which activates cortisol, and 11β-HSD2, which inactivates it. Under normal conditions, the placenta limits fetal cortisol exposure via 11β-HSD2. However, in GDM, this protective barrier may be compromised. Elevated 11β-HSD1 activity in maternal liver and placenta, coupled with reduced placental 11β-HSD2 expression, has been reported in GDM pregnancies, leading to enhanced local and fetal cortisol availability[125,126].

This increased glucocorticoid exposure has been shown in animal studies to induce fetal hepatic overexpression of gluconeogenic enzymes, impair insulin sensitivity, and alter stress-axis reactivity into postnatal life[127,128].

Some human studies support these findings, linking reduced placental 11β-HSD2 expression with increased neonatal adiposity and elevated fasting insulin levels. However, results are inconsistent. Other cohorts report no significant differences in 11β-HSD2 levels between GDM and control placentas, suggesting that maternal phenotype, fetal sex, or epigenetic regulation may modulate enzyme activity[126,129]. These discrepancies underline the complexity of glucocorticoid-mediated programming and its sensitivity to both maternal metabolic status and placental function. Moreover, it remains unclear whether increased fetal cortisol exposure is a direct consequence of maternal hepatic dysfunction or a broader manifestation of systemic endocrine dysregulation.

Taken together, alterations in glucocorticoid metabolism and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis modulation may act synergistically with other GDM-related stressors to shape fetal hepatic function and metabolic risk. Clarifying the tissue-specific drivers of these changes, particularly within the maternal liver vs the placenta - will be critical for identifying safe and effective interventions.

Beyond established pathways, several emerging mechanisms may contribute to fetal liver programming in GDM, although they remain incompletely characterized. One such mechanism is mitochondrial dysfunction, which may be maternally transmitted or induced by intrauterine stress. Altered mitochondrial DNA content has been reported in placental and cord blood samples from GDM pregnancies, indicating disruptions in mitochondrial biogenesis and energy metabolism. However, direct assessment of mitochondrial integrity in fetal hepatocytes remains scarce[130-132].

Another area of interest is fetal hepatic stem cell fate and liver zonation. Maternal metabolic stress may interfere with the balance between hepatocyte and cholangiocyte lineage differentiation during liver development, potentially impairing regenerative capacity or altering zonal metabolic programming. Although supported by animal studies, human evidence remains limited[133-135].

Inter-organ communication between the maternal liver and fetal hypothalamus has also been hypothesized[136,137]. This cross-talk may occur indirectly through placental signaling of neuroactive substances such as leptin or serotonin, or directly via metabolic intermediates like glucose, lipids, and ketone bodies that cross the placenta. These signals can influence fetal neurodevelopment and metabolic set points, but evidence for direct liver-to-brain signaling remains speculative. Moreover, while hepatokines such as FGF21 are unlikely to cross the placenta due to their size and polarity, they may still affect fetal physiology by modulating maternal metabolism, placental transport, or systemic inflammatory tone[78,138-140].

Overall, these underexplored mechanisms underscore the need for more integrative and tissue-specific research. Limitations in accessing human fetal liver tissue, distinguishing maternal from placental influences, and capturing dynamic changes across gestation have constrained progress in this area. Prospective, longitudinal studies incorporating functional imaging, multi-omics profiling, and advanced in vitro or organoid models will be essential for revealing the full spectrum of maternal hepatic influences on fetal development. Figure 2 summarizes the mechanisms linking maternal liver dysfunction to fetal outcomes in GDM.

Fetal exposure to maternal GDM, particularly when accompanied by hepatic dysfunction, has been strongly implicated in programming adverse liver and cardiometabolic outcomes in the offspring. The intrauterine milieu is characterized by excess glucose, lipids, inflammatory cytokines, and dysregulated hepatokines serve as a potent modifier of fetal hepatic development, with implications extending into adolescence and adulthood[133].

MRI studies have shown that neonates of mothers with GDM exhibit increased hepatic fat accumulation, even in the absence of macrosomia or overt metabolic disease, suggesting early lipid reprogramming[16,141]. Consistent findings in animal models have shown upregulated hepatic lipogenic genes such as SREBP-1c and FASN and mitochondrial dysfunction in offspring exposed to maternal hyperglycemia[39,62]. However, the trajectory of these changes remains under debate. While some longitudinal human studies report normalization of hepatic markers by early childhood, others indicate persistent hepatic steatosis, particularly when postnatal environments are obesogenic[142,143]. This suggests that prenatal metabolic programming may establish a latent susceptibility, with disease expression modulated by postnatal exposures.

Growing evidence implicates GDM as a significant risk factor for NAFLD in both the mother and her offspring. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis of 20 studies, including 12 in quantitative synthesis, demonstrated that women with a history of GDM have a 50% increased risk of developing NAFLD during a follow-up period ranging from 16 months to 25 years post-pregnancy. This intergenerational risk is even more pronounced in offspring, who exhibit nearly double the risk of NAFLD, with some cases documented up to 17.8 years after birth[4].

A meta-analysis from South Asia further supports this association, reporting that women with a history of GDM had a 2.11-fold increased risk of developing NAFLD compared to non-GDM counterparts[144]. Ethnic-specific factors such as increased visceral adiposity, insulin resistance at lower BMI thresholds, dietary differences, and disparities in prenatal care may contribute to these observed variations[145]. These findings underscore the importance of studying ethnically diverse populations to refine risk prediction and design culturally tailored preventive strategies.

Neonates born to mothers with GDM exhibit reduced gut microbial diversity and compositional shifts marked by an elevated Firmicutes-to-Bacteroidetes ratio and increased abundance of pro-inflammatory taxa such as Escherichia and Clostridium sensu stricto. Concurrently, colonization by beneficial genera like Bifidobacterium is often delayed, particularly in breastfed infants. These alterations may impair gut barrier integrity and promote systemic inflammation, contributing to metabolic programming and increased susceptibility to insulin resistance and hepatic steatosis later in life[146].

Beyond liver-specific outcomes, in utero exposure to maternal GDM also increases the offspring’s risk for systemic metabolic disorders. Epidemiological studies have consistently demonstrated higher rates of insulin resistance, impaired glucose tolerance, and obesity in GDM-exposed children and adolescents[147-149]. These risks are partially attributed to altered hepatic insulin signaling in the offspring, including reduced expression of key proteins such as IRS-1, AKT, and gluconeogenic enzymes. Sex-specific patterns have also been observed, with male offspring showing greater vulnerability to hepatic steatosis and insulin resistance. Potential mechanisms include differential placental gene expression, hormonal influences, and hepatic sensitivity to glucocorticoids and inflammatory stimuli[21,126].

In addition to metabolic outcomes, GDM exposure has been associated with early-life cardiovascular and renal alterations. A recent meta-analysis of 31 observational studies involving 4373 infants reported that newborns of diabetic mothers exhibited increased interventricular septal thickness, suggestive of cardiac hypertrophy, along with reduced myocardial performance index and decreased left ventricle early-to-late atrial filling velocity ratio, markers of impaired global and diastolic function. These abnormalities were most pronounced within the first week of life and, in some cases, persisted up to six months. Interestingly, left ventricular systolic function remained largely preserved. By early childhood, most of these parameters normalized, though it remains unclear whether this reflects true resolution or dia

The renal system also appears vulnerable to in utero exposure to GDM. A prospective study of 30-40-day-old infants born to mothers with poorly controlled GDM revealed significantly lower renal volumes and elevated urinary biomarkers of tubular injury, including N-acetyl-β-D-glucosaminidase and cathepsin B. In contrast, neonates born to mothers who achieved good glycemic control showed renal profiles comparable to those of healthy controls[151]. These data suggest that metabolic derangements during gestation can initiate early renal structural and functional impairments, potentially predisposing offspring to hypertension and chronic kidney disease later in life. These findings advocate for strict prenatal glycemic control and multidisciplinary postnatal surveillance in this high-risk population.

Emerging evidence also links GDM exposure with neurodevelopmental alterations in offspring. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis of 202 studies encompassing over 56 million mother-child pairs revealed that children born to mothers with diabetes have significantly increased risks of multiple neurodevelopmental disorders. Adjusting for confounders, GDM exposure was associated with higher risks of autism spectrum disorder [risk ratio (RR) = 1.25], ADHD (RR = 1.30), intellectual disability (RR = 1.32), and other learning, communication, and motor disorders[152]. While pregestational diabetes posed a higher relative risk, GDM remained an independent contributor to neurodevelopmental impairment.

Animal studies provide mechanistic insight, demonstrating that maternal hyperglycemia impairs hippocampal synaptic development, increases oxidative stress, and disrupts neuroplasticity, resulting in memory and learning deficits in offspring. Additionally, altered DNA methylation in neurodevelopmental genes such as OR2 L13 and CYP2E1 has been documented in GDM-exposed neonates, suggesting epigenetic contributions to long-term cognitive risk[88,153]. Collectively, these findings emphasize the need for early neurodevelopmental screening and support in children born to GDM pregnancies, even in the absence of macrosomia or overt metabolic dysfunction.

Evidence from both clinical and experimental studies suggests that GDM disrupts fetal liver development through multiple, intersecting mechanisms, ultimately reducing hepatic resilience and increasing susceptibility to postnatal metabolic stressors. In animal models, maternal hyperglycemia leads to hepatocyte edema, elevated liver-to-body weight ratio, increased apoptosis and autophagy, and dysregulation of metabolic and apoptotic protein expression. Notably, these impairments were partially attenuated by taurine supplementation, highlighting the potential of nutritional stra

In human cohorts, intrauterine hyperglycemia has been linked to early hepatic steatosis, oxidative stress, and subclinical inflammation in offspring, mediated in part by impaired insulin signaling and elevated pro-inflammatory cytokines. These alterations appear to persist into childhood, especially when compounded by obesogenic environments[125,149].

Epigenetic reprogramming further amplifies long-term hepatic vulnerability. Persistent changes in DNA methylation of genes related to metabolism, redox balance, and cellular stress, alongside shifts in gut microbiota composition may prime the liver for exaggerated responses to secondary metabolic insults such as high-fat diets or environmental toxins. These findings align with the “multiple-hit” model of NAFLD pathogenesis, in which prenatal hepatic priming creates a subclinical susceptibility that is later exacerbated by lifestyle and environmental exposures[149,154,155].

Emerging research indicates that GDM-related epigenetic alterations may be transmitted across generations, extending metabolic vulnerability beyond the directly exposed offspring. Animal studies have shown that DNA methylation changes in genes such as Dlk1, Gtl2, and POMC which are involved in adipogenesis, glucose regulation, and hepatic function can persist into F2 and even F3 generations, despite no further direct exposure to maternal hyperglycemia[156-158].

These heritable epigenetic modifications raise concern about the perpetuation of metabolic disease risk and underscore the critical need for early preventive strategies. While direct evidence in humans remains limited, longitudinal epigenetic tracking in high-risk birth cohorts could offer valuable insight into intergenerational programming mechanisms and intervention windows.

As understanding of GDM evolves, clinical strategies must expand beyond glycemic control to encompass maternal liver function as a central driver of both maternal and fetal health. Recognizing the liver’s role in metabolic adaptation offers new opportunities for earlier detection, targeted maternal interventions, and long-term prevention of intergenerational disease.

Traditional GDM screening relies primarily on glycemic thresholds, yet hepatic dysfunction often precedes overt hyperglycemia, particularly in women with obesity or metabolic syndrome. Early elevations in ALT, GGT, or hepatic steatosis indices may provide actionable signals of early risk[43,159]. Incorporating these hepatic markers into first-trimester metabolic panels could enhance detection of subclinical GDM.

Additionally, fetal liver volume that is measurable via ultrasonography or MRI, has emerged as a potential marker of intrauterine metabolic stress, correlating with maternal dysglycemia and dyslipidemia[16]. Though underused, this approach may be enhanced by artificial intelligence-assisted biometry platforms such as CUPID, which offer highly accurate and scalable fetal assessment[160].

While glycemic control remains the cornerstone of GDM management, it does not fully mitigate risks associated with hepatic insulin resistance and dysregulated lipid metabolism[161]. Maternal hypertriglyceridemia, driven in part by impaired hepatic lipid clearance, has been independently associated with fetal overgrowth and early-onset NAFLD in offspring, even in pregnancies where glucose levels are well-controlled[4,161]. Expanding maternal care protocols to include regular lipid profiling, particularly in the third trimester, could help identify high-risk pregnancies that would otherwise be overlooked.

Lifestyle interventions focused on hepatic health, including dietary fiber, omega-3 fatty acid intake, and moderate physical activity have shown efficacy in improving liver insulin sensitivity and reducing lipotoxicity[39,162-166]. In parallel, modulation of the gut–liver axis through prebiotic and probiotic strategies may reduce inflammatory and meta

Physical activity during pregnancy is a well-established intervention that can improve maternal metabolic health and reduce transgenerational risk. In animal models, gestational exercise reduced hepatic lipid accumulation and promoted mitochondrial biogenesis in both mothers and offspring[169].

In human studies, maternal exercise is associated with improved pregnancy outcomes, including higher rates of full-term delivery, lower risk of macrosomia, and normalized birth measures[170,171]. Aerobic exercise during pregnancy has also been shown to enhance newborn neurobehavioral performance and promote improved cardiac autonomic regulation in infants[172-175]. Furthermore, infants born to physically active mothers demonstrate better motor development and a greater capacity for spontaneous movement, which may translate into increased physical activity during infancy and a reduced risk of early-onset obesity[176].

These physiological and behavioral benefits suggest that prenatal exercise may positively influence metabolic pro

Offspring of GDM pregnancies show increased risk for metabolic syndrome, hepatic steatosis, and insulin resistance - often rooted in prenatal hepatic reprogramming[133,150,153,155]. Pediatric follow-up protocols should include liver enzyme testing, ultrasonography, and growth tracking, particularly for children with early weight gain or central adipo

Sex-specific vulnerabilities also warrant attention. Male offspring appear more susceptible to hepatic lipid accumulation and insulin resistance, suggesting that follow-up strategies should account for fetal sex and perinatal exposures[21,126,153].

Prenatal nutrition offers a low-risk and scalable tool to protect maternal liver function and fetal outcomes. Diets rich in choline, omega-3 fatty acids, and fiber not only support hepatic insulin sensitivity but also beneficially shape the maternal microbiota and bile acid profile[34,162,164].

Personalized nutrition tailored to maternal liver phenotype may further optimize outcomes[179,180]. On the therapeutic front, hepatocyte-targeted agents such as FXR agonists, FGF19 analogues, and tauroursodeoxycholic acid show promise in preclinical studies, though safety and efficacy trials in pregnant populations are needed[110,114,181].

Despite considerable advances in understanding the hepatic dimension of GDM, important gaps persist. Most existing studies are observational or cross-sectional, limiting causal inference between maternal hepatic dysfunction and offspring outcomes. Longitudinal cohort studies with repeated maternal-fetal liver assessments (biochemical, imaging, and transcriptomic) are urgently needed. Additionally, while early elevations in hepatic enzymes and steatosis indices are frequently reported in GDM, these markers have yet to be standardized or integrated into clinical screening algorithms[159]. Similarly, although fetal liver imaging shows promise as a non-invasive biomarker, it has not been widely inte

Moreover, nutritional and microbiome-targeted strategies show promise in preclinical models but lack robust clinical trial validation[179]. Hepatocyte-specific agents require careful evaluation in pregnancy due to potential placental and fetal effects[110]. Systems biology approaches integrating liver-microbiota-placenta axes could provide deeper mec

Although preclinical and small-scale studies provide encouraging evidence for interventions such as exercise, omega-3 fatty acids, and microbiota modulation, robust clinical validation remains limited. Large-scale, multicenter randomized controlled trials are essential to assess the safety, timing, and efficacy of these strategies across diverse maternal popu

Animal models have demonstrated that epigenetic changes in hepatic regulators such as Dlk1, POMC, Sirt1 can persist across generations, even without continued metabolic stress, suggesting a risk of transgenerational transmission[149,156]. However, robust multigenerational human data remain scarce.

Future research should prioritize prospective birth cohorts that track maternal liver parameters, fetal hepatic development, and offspring outcomes across multiple decades, and ideally, generations. Integrating epigenetic profiling, microbiome sequencing, and metabolomics into these cohorts could illuminate the molecular mechanisms driving transgenerational risk. Such studies would not only inform prevention but also enable the development of precision health models aimed at breaking intergenerational cycles of liver-related metabolic disease.

A hepatocentric framework not only informs clinical care but also opens avenues for precision medicine and public health innovation. Stratifying prenatal interventions based on hepatic phenotypes may enable individualized risk prediction and targeted nutritional or therapeutic strategies. For example, omega-3 supplementation may be selectively effective in pregnancies with steatosis-linked hyperlipidemia.

Incorporating liver-specific endpoints into perinatal trials may also enhance treatment precision and efficacy. At the policy level, recognizing maternal liver health as a determinant of offspring outcomes may support revisions to prenatal screening guidelines and dietary frameworks. Interdisciplinary collaboration among hepatology, obstetrics, pediatrics, and public health will be crucial to operationalize this model.

GDM must be reframed not only as a disorder of glucose regulation, but as a systemic metabolic condition in which the maternal liver plays a central and dynamic role. From influencing lipid and insulin homeostasis to shaping the fetal liver’s development and function, the maternal liver emerges as both regulator and messenger in the intergenerational transmission of health and disease. A hepatocentric approach to GDM, integrating early liver-based screening, personalized maternal nutrition, fetal hepatic surveillance, and pediatric follow-up offers a promising path toward improving outcomes for mothers, children, and future generations. Bridging mechanistic insights with clinical innovation will be the key to translating this model into practice.

| 1. | American Diabetes Association. Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2022 Abridged for Primary Care Providers. Clin Diabetes. 2022;40:10-38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in RCA: 379] [Article Influence: 94.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Wicklow B, Retnakaran R. Gestational Diabetes Mellitus and Its Implications across the Life Span. Diabetes Metab J. 2023;47:333-344. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Barbour LA, McCurdy CE, Hernandez TL, Kirwan JP, Catalano PM, Friedman JE. Cellular mechanisms for insulin resistance in normal pregnancy and gestational diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2007;30 Suppl 2:S112-S119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 457] [Cited by in RCA: 515] [Article Influence: 27.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Foo RX, Ma JJ, Du R, Goh GBB, Chong YS, Zhang C, Li LJ. Gestational diabetes mellitus and development of intergenerational non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) after delivery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine. 2024;72:102609. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Zeng J, Shen F, Zou ZY, Yang RX, Jin Q, Yang J, Chen GY, Fan JG. Association of maternal obesity and gestational diabetes mellitus with overweight/obesity and fatty liver risk in offspring. World J Gastroenterol. 2022;28:1681-1691. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Gluckman PD, Hanson MA. The Developmental Origins of Health and Disease. In: Wintour EM, Owens JA, editors. Early Life Origins of Health and Disease. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. Boston: Springer, 2006: 1-7. |

| 7. | Meek CL. An unwelcome inheritance: childhood obesity after diabetes in pregnancy. Diabetologia. 2023;66:1961-1970. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Fang H, Li Q, Wang H, Ren Y, Zhang L, Yang L. Maternal nutrient metabolism in the liver during pregnancy. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2024;15:1295677. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Miao X, Alidadipour A, Saed V, Sayyadi F, Jadidi Y, Davoudi M, Amraee F, Jadidi N, Afrisham R. Hepatokines: unveiling the molecular and cellular mechanisms connecting hepatic tissue to insulin resistance and inflammation. Acta Diabetol. 2024;61:1339-1361. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kim TH, Hong DG, Yang YM. Hepatokines and Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: Linking Liver Pathophysiology to Metabolism. Biomedicines. 2021;9:1903. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Wu P, Wang Y, Ye Y, Yang X, Huang Y, Ye Y, Lai Y, Ouyang J, Wu L, Xu J, Yuan J, Hu Y, Wang YX, Liu G, Chen D, Pan A, Pan XF. Liver biomarkers, lipid metabolites, and risk of gestational diabetes mellitus in a prospective study among Chinese pregnant women. BMC Med. 2023;21:150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Lee SM, Kwak SH, Koo JN, Oh IH, Kwon JE, Kim BJ, Kim SM, Kim SY, Kim GM, Joo SK, Koo BK, Shin S, Vixay C, Norwitz ER, Park CW, Jun JK, Kim W, Park JS. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in the first trimester and subsequent development of gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia. 2019;62:238-248. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 12.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Varlamov O. Metabolic reprogramming of fetal hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells by maternal obesity. Front Hematol. 2025;4:1575143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Ortiz M, Sánchez F, Álvarez D, Flores C, Salas-Pérez F, Valenzuela R, Cantin C, Leiva A, Crisosto N, Maliqueo M. Association between maternal obesity, essential fatty acids and biomarkers of fetal liver function. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2023;190:102541. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Wang S, Chen S, Sun J, Han P, Xu B, Li X, Zhong Y, Xu Z, Zhang P, Mi P, Zhang C, Li L, Zhang H, Xia Y, Li S, Heikenwalder M, Yuan D. m(6)A modification-tuned sphingolipid metabolism regulates postnatal liver development in male mice. Nat Metab. 2023;5:842-860. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Strobel KM, Kafali SG, Shih SF, Artura AM, Masamed R, Elashoff D, Wu HH, Calkins KL. Pregnancies complicated by gestational diabetes and fetal growth restriction: an analysis of maternal and fetal body composition using magnetic resonance imaging. J Perinatol. 2023;43:44-51. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Brumbaugh DE, Tearse P, Cree-Green M, Fenton LZ, Brown M, Scherzinger A, Reynolds R, Alston M, Hoffman C, Pan Z, Friedman JE, Barbour LA. Intrahepatic fat is increased in the neonatal offspring of obese women with gestational diabetes. J Pediatr. 2013;162:930-6.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 151] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kerr B, Leiva A, Farías M, Contreras-Duarte S, Toledo F, Stolzenbach F, Silva L, Sobrevia L. Foetoplacental epigenetic changes associated with maternal metabolic dysfunction. Placenta. 2018;69:146-152. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Kelstrup L, Hjort L, Houshmand-Oeregaard A, Clausen TD, Hansen NS, Broholm C, Borch-Johnsen L, Mathiesen ER, Vaag AA, Damm P. Gene Expression and DNA Methylation of PPARGC1A in Muscle and Adipose Tissue From Adult Offspring of Women With Diabetes in Pregnancy. Diabetes. 2016;65:2900-2910. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Xie X, Gao H, Zeng W, Chen S, Feng L, Deng D, Qiao FY, Liao L, McCormick K, Ning Q, Luo X. Placental DNA methylation of peroxisome-proliferator-activated receptor-γ co-activator-1α promoter is associated with maternal gestational glucose level. Clin Sci (Lond). 2015;129:385-394. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Luo SS, Zhu H, Huang HF, Ding GL. Sex differences in glycolipidic disorders after exposure to maternal hyperglycemia during early development. J Endocrinol Invest. 2023;46:1521-1531. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Scholtens DM, Kuang A, Lowe LP, Hamilton J, Lawrence JM, Lebenthal Y, Brickman WJ, Clayton P, Ma RC, McCance D, Tam WH, Catalano PM, Linder B, Dyer AR, Lowe WL Jr, Metzger BE; HAPO Follow-up Study Cooperative Research Group; HAPO Follow-Up Study Cooperative Research Group. Hyperglycemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcome Follow-up Study (HAPO FUS): Maternal Glycemia and Childhood Glucose Metabolism. Diabetes Care. 2019;42:381-392. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 176] [Cited by in RCA: 209] [Article Influence: 29.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Cohen CC, Perng W, Bekelman TA, Ringham BM, Scherzinger A, Shankar K, Dabelea D. Childhood nutrient intakes are differentially associated with hepatic and abdominal fats in adolescence: The EPOCH study. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2022;30:460-471. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Cai Z, Yang Y, Zhang J. Hepatokine levels during the first or early second trimester of pregnancy and the subsequent risk of gestational diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Biomarkers. 2021;26:517-531. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Kalhan S, Rossi K, Gruca L, Burkett E, O'Brien A. Glucose turnover and gluconeogenesis in human pregnancy. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:1775-1781. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Herrera E, Ortega-Senovilla H. Disturbances in lipid metabolism in diabetic pregnancy - Are these the cause of the problem? Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;24:515-525. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 163] [Cited by in RCA: 178] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Trivett C, Lees ZJ, Freeman DJ. Adipose tissue function in healthy pregnancy, gestational diabetes mellitus and pre-eclampsia. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2021;75:1745-1756. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Della Torre S, Mitro N, Fontana R, Gomaraschi M, Favari E, Recordati C, Lolli F, Quagliarini F, Meda C, Ohlsson C, Crestani M, Uhlenhaut NH, Calabresi L, Maggi A. An Essential Role for Liver ERα in Coupling Hepatic Metabolism to the Reproductive Cycle. Cell Rep. 2016;15:360-371. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Duggleby SL, Jackson AA. Protein, amino acid and nitrogen metabolism during pregnancy: how might the mother meet the needs of her fetus? Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2002;5:503-509. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Elango R, Ball RO. Protein and Amino Acid Requirements during Pregnancy. Adv Nutr. 2016;7:839S-844S. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Fan HM, Mitchell AL, Williamson C. ENDOCRINOLOGY IN PREGNANCY: Metabolic impact of bile acids in gestation. Eur J Endocrinol. 2021;184:R69-R83. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Van Mil SW, Milona A, Dixon PH, Mullenbach R, Geenes VL, Chambers J, Shevchuk V, Moore GE, Lammert F, Glantz AG, Mattsson LA, Whittaker J, Parker MG, White R, Williamson C. Functional variants of the central bile acid sensor FXR identified in intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:507-516. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 186] [Cited by in RCA: 187] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Ourlin JC, Lasserre F, Pineau T, Fabre JM, Sa-Cunha A, Maurel P, Vilarem MJ, Pascussi JM. The small heterodimer partner interacts with the pregnane X receptor and represses its transcriptional activity. Mol Endocrinol. 2003;17:1693-1703. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Obeid R, Schön C, Derbyshire E, Jiang X, Mellott TJ, Blusztajn JK, Zeisel SH. A Narrative Review on Maternal Choline Intake and Liver Function of the Fetus and the Infant; Implications for Research, Policy, and Practice. Nutrients. 2024;16:260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Yakout SM, Hussein S, Al-Attas OS, Hussain SD, Saadawy GM, Al-Daghri NM. Hepatokines fetuin A and fetuin B status in women with/without gestational diabetes mellitus. Am J Transl Res. 2023;15:1291-1299. [PubMed] |

| 36. | Abdeltawab A, Zaki ME, Abdeldayem Y, Mohamed AA, Zaied SM. Circulating micro RNA-223 and angiopoietin-like protein 8 as biomarkers of gestational diabetes mellitus. Br J Biomed Sci. 2021;78:12-17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Faal S, Abedi P, Jahanfar S, Ndeke JM, Mohaghegh Z, Sharifipour F, Zahedian M. Sex hormone binding globulin for prediction of gestational diabetes mellitus in pre-conception and pregnancy: A systematic review. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2019;152:39-52. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Grilo LF, Martins JD, Diniz MS, Tocantins C, Cavallaro CH, Baldeiras I, Cunha-Oliveira T, Ford S, Nathanielsz PW, Oliveira PJ, Pereira SP. Maternal hepatic adaptations during obese pregnancy encompass lobe-specific mitochondrial alterations and oxidative stress. Clin Sci (Lond). 2023;137:1347-1372. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Stevanović-Silva J, Beleza J, Coxito P, Rocha H, Gaspar TB, Gärtner F, Correia R, Fernandes R, Oliveira PJ, Ascensão A, Magalhães J. Exercise performed during pregnancy positively modulates liver metabolism and promotes mitochondrial biogenesis of female offspring in a rat model of diet-induced gestational diabetes. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 2022;1868:166526. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Stevanović-Silva J, Beleza J, Coxito P, Pereira S, Rocha H, Gaspar TB, Gärtner F, Correia R, Martins MJ, Guimarães T, Martins S, Oliveira PJ, Ascensão A, Magalhães J. Maternal high-fat high-sucrose diet and gestational exercise modulate hepatic fat accumulation and liver mitochondrial respiratory capacity in mothers and male offspring. Metabolism. 2021;116:154704. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Sun YY, Juan J, Xu QQ, Su RN, Hirst JE, Yang HX. Increasing insulin resistance predicts adverse pregnancy outcomes in women with gestational diabetes mellitus. J Diabetes. 2020;12:438-446. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Zhang R, Xing B, Zhao J, Zhang X, Zhou L, Yang S, Wang Y, Yang F. Astragaloside IV relieves gestational diabetes mellitus in genetic mice through reducing hepatic gluconeogenesis. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2020;98:466-472. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Cui L, Yang X, Li Z, Gao Y, Zhang Z, Xu D, Liu X. Elevated liver enzymes in the first trimester are associated with gestational diabetes mellitus: A prospective cohort study. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2024;40:e3799. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Zhao W, Zhang L, Zhang G, Varkaneh HK, Rahmani J, Clark C, Ryan PM, Abdulazeem HM, Salehisahlabadi A. The association of plasma levels of liver enzymes and risk of gestational diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of observational studies. Acta Diabetol. 2020;57:635-644. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Jiménez-Osorio AS, Carreón-Torres E, Correa-Solís E, Ángel-García J, Arias-Rico J, Jiménez-Garza O, Morales-Castillejos L, Díaz-Zuleta HA, Baltazar-Tellez RM, Sánchez-Padilla ML, Flores-Chávez OR, Estrada-Luna D. Inflammation and Oxidative Stress Induced by Obesity, Gestational Diabetes, and Preeclampsia in Pregnancy: Role of High-Density Lipoproteins as Vectors for Bioactive Compounds. Antioxidants (Basel). 2023;12:1894. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Saucedo R, Ortega-Camarillo C, Ferreira-Hermosillo A, Díaz-Velázquez MF, Meixueiro-Calderón C, Valencia-Ortega J. Role of Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Antioxidants (Basel). 2023;12:1812. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Sormunen-Harju H. Maternal obesity: Associations between obesity, pregnancy complications, and maternal and newborn metabolome. M.Sc. Thesis, University of Helsinki. 2024. Available from: https://helda.helsinki.fi/server/api/core/bitstreams/322b1e99-6f98-47ad-a086-5e0b69be6915/content. |

| 48. | Gao S, Su S, Zhang E, Zhang Y, Liu J, Xie S, Yue W, Liu R, Yin C. The effect of circulating adiponectin levels on incident gestational diabetes mellitus: systematic review and metaanalysis. Ann Med. 2023;55:2224046. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Shirif AZ, Kovačević S, Brkljačić J, Teofilović A, Elaković I, Djordjevic A, Matić G. Decreased Glucocorticoid Signaling Potentiates Lipid-Induced Inflammation and Contributes to Insulin Resistance in the Skeletal Muscle of Fructose-Fed Male Rats Exposed to Stress. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:7206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Puppala S, Li C, Glenn JP, Saxena R, Gawrieh S, Quinn A, Palarczyk J, Dick EJ Jr, Nathanielsz PW, Cox LA. Primate fetal hepatic responses to maternal obesity: epigenetic signalling pathways and lipid accumulation. J Physiol. 2018;596:5823-5837. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Singh P, Elhaj DAI, Ibrahim I, Abdullahi H, Al Khodor S. Maternal microbiota and gestational diabetes: impact on infant health. J Transl Med. 2023;21:364. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Zheng J, Xiao X, Zhang Q, Mao L, Yu M, Xu J, Wang T. The Placental Microbiota Is Altered among Subjects with Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: A Pilot Study. Front Physiol. 2017;8:675. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Ferrocino I, Ponzo V, Gambino R, Zarovska A, Leone F, Monzeglio C, Goitre I, Rosato R, Romano A, Grassi G, Broglio F, Cassader M, Cocolin L, Bo S. Changes in the gut microbiota composition during pregnancy in patients with gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM). Sci Rep. 2018;8:12216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 156] [Cited by in RCA: 184] [Article Influence: 23.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Kralisch S, Hoffmann A, Lössner U, Kratzsch J, Blüher M, Stumvoll M, Fasshauer M, Ebert T. Regulation of the novel adipokines/ hepatokines fetuin A and fetuin B in gestational diabetes mellitus. Metabolism. 2017;68:88-94. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Wang WJ, He H, Fang F, Liu X, Yang MN, Chen ZL, Wu T, Huang R, Li F, Zhang J, Ouyang F, Luo ZC. Cord Blood Fetuin-B, Fetal Growth Factors, and Lipids in Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2025;110:e1540-e1546. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Yuan D, Wu BJ, Henry A, Rye KA, Ong KL. Role of fibroblast growth factor 21 in gestational diabetes mellitus: A mini-review. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2019;90:47-55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Cao Z, Deng Z, Lu J, Yuan Y. Circulating fibroblast growth factor 21 levels in gestational diabetes mellitus and preeclampsia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2025;25:34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Wang N, Sun B, Guo H, Jing Y, Ruan Q, Wang M, Mi Y, Chen H, Song L, Cui W. Association of Elevated Plasma FGF21 and Activated FGF21 Signaling in Visceral White Adipose Tissue and Improved Insulin Sensitivity in Gestational Diabetes Mellitus Subtype: A Case-Control Study. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2021;12:795520. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Huang Y, Chen X, Chen X, Feng Y, Guo H, Li S, Dai T, Jiang R, Zhang X, Fang C, Hu J. Angiopoietin-like protein 8 in early pregnancy improves the prediction of gestational diabetes. Diabetologia. 2018;61:574-580. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Seyhanli Z, Seyhanli A, Aksun S, Pamuk BO. Evaluation of serum Angiopoietin-like protein 2 (ANGPTL-2), Angiopoietin-like protein 8 (ANGPTL-8), and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) levels in patients with gestational diabetes mellitus and normoglycemic pregnant women. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2022;35:5647-5652. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Marques Puga F, Borges Duarte D, Benido Silva V, Pereira MT, Garrido S, Vilaverde J, Sales Moreira M, Pichel F, Pinto C, Dores J. Maternal Hypertriglyceridemia in Gestational Diabetes: A New Risk Factor? Nutrients. 2024;16:1577. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 62. | Eroglu N, Yerlikaya FH, Onmaz DE, Colakoglu MC. Role of ChREBP and SREBP-1c in gestational diabetes: two key players in glucose and lipid metabolism. Int J Diabetes Dev Ctries. 2023;43:587-591. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | He M, Guo X, Jia J, Zhang J, Zhou X, Wei L, Yu J, Wang S, Feng L. Regulatory mechanisms underlying endoplasmic reticulum stress involvement in the development of gestational diabetes mellitus entail the CHOP-PPARα-NF-κB pathway. Placenta. 2023;142:46-55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Farag A. Role of third-trimester serum triglycerides in the prediction of large-for-gestational-age (LGA) in pregestational and gestational diabetes mellitus. Minia J Med Res. 2022;0:258-266. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 65. | Barbour LA, Hernandez TL. Maternal Non-glycemic Contributors to Fetal Growth in Obesity and Gestational Diabetes: Spotlight on Lipids. Curr Diab Rep. 2018;18:37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Liu PJ, Liu Y, Ma L, Yao AM, Chen XY, Hou YX, Wu LP, Xia LY. The Predictive Ability of Two Triglyceride-Associated Indices for Gestational Diabetes Mellitus and Large for Gestational Age Infant Among Chinese Pregnancies: A Preliminary Cohort Study. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2020;13:2025-2035. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Chagovets V, Frankevich N, Starodubtseva N, Tokareva A, Derbentseva E, Yuryev S, Kutzenko A, Sukhikh G, Frankevich V. Early Prediction of Fetal Macrosomia Through Maternal Lipid Profiles. Int J Mol Sci. 2025;26:1149. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Ott R, Stupin JH, Loui A, Eilers E, Melchior K, Rancourt RC, Schellong K, Ziska T, Dudenhausen JW, Henrich W, Plagemann A. Maternal overweight is not an independent risk factor for increased birth weight, leptin and insulin in newborns of gestational diabetic women: observations from the prospective 'EaCH' cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18:250. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |