Published online Feb 26, 2026. doi: 10.4252/wjsc.v18.i2.114980

Revised: November 10, 2025

Accepted: January 15, 2026

Published online: February 26, 2026

Processing time: 133 Days and 22.9 Hours

Steroid-induced avascular necrosis of the femoral head is a debilitating condition caused by prolonged glucocorticoid exposure, leading to bone death and disru

Core Tip: Silencing sclerostin in human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells enhances their bone-regenerative potential by activating the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, providing a novel therapeutic approach for steroid-induced avascular necrosis of the femoral head. In the study by Lv et al, sh-human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells demonstrated better osteogenesis, suppressed adipogenesis, and improved bone architecture in a steroid-induced rat model compared to unmo

- Citation: Sharma P, Maurya DK. Sclerostin silencing in human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells enhances bone regeneration via Wnt pathway activation. World J Stem Cells 2026; 18(2): 114980

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-0210/full/v18/i2/114980.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4252/wjsc.v18.i2.114980

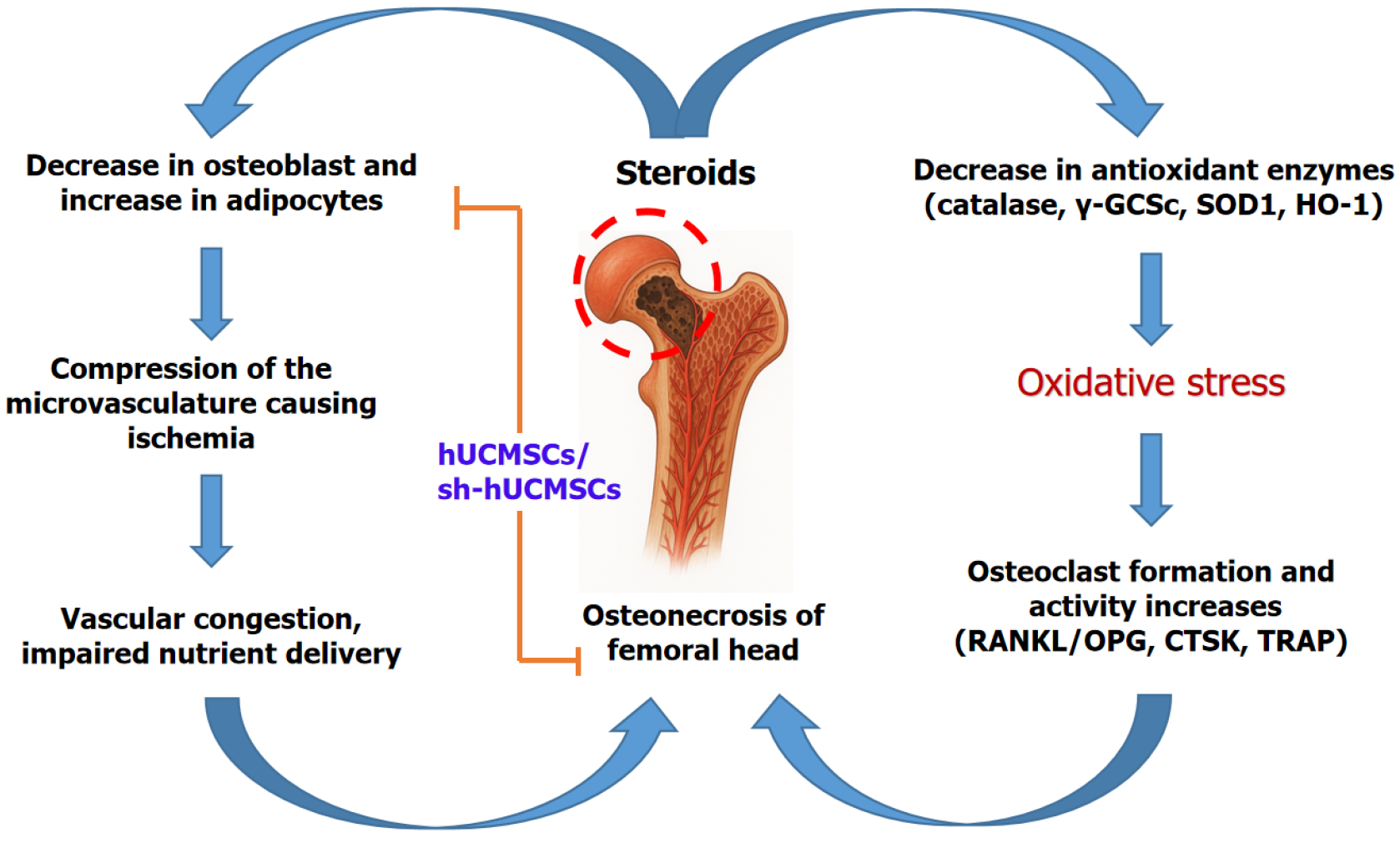

Steroid-induced avascular necrosis of the femoral head (SANFH) is a serious complication from glucocorticoid therapy, where bone death occurs due to impaired blood supply within the hip joint’s ball (femoral head)[1,2]. Corticosteroids, commonly used during organ transplantation and inflammatory disorders management, increase pressure inside the confined space of the femoral head, causing damage to delicate blood vessels[3]. This elevated pressure leads to ischemia, a restriction in blood flow, depriving bone tissue of oxygen and nutrients[4]. The resulting lack of blood supply causes osteonecrosis i.e., death of bone cells and marrow, progressively weakening the bone structure. Clinically, steroid-induced avascular necrosis (AVN) presents with groin pain that worsens with weight-bearing, leading to joint dys

Conventional pharmacotherapies are largely ineffective at reversing advanced SANFH, necessitating hip replacement in many cases. Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), especially those derived from human umbilical cord tissue (hUCMSCs), have gained attention for their regenerative and immunomodulatory capabilities[8]. However, modulation of these cells’ bone-forming efficiency remains a challenge. Sclerostin (SOST), a glycoprotein secreted by osteocytes, antagonizes the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, thereby suppressing osteoblast differentiation and bone formation. Targeting SOST through gene silencing could potentiate MSC-mediated bone repair. While hUCMSCs are a promising therapeutic vehicle, their bone-forming efficacy is naturally limited by inhibitory pathways within the bone microenvironment. Therefore, strategies to enhance their osteogenic potential are critically needed. Lv et al[9] addressed this gap by exploring SOST silencing to potentiate hUCMSC-mediated bone regeneration. This editorial discusses Lv et al’s study[9] that investigates SOST-silenced hUCMSCs as a novel cellular therapy to restore bone metabolic balance in SANFH.

SANFH incidence is rising globally due to widespread glucocorticoid use for autoimmune and inflammatory diseases. MSCs are promising candidates for cell-based therapy due to their multipotency and paracrine effects promoting osteogenesis and angiogenesis. hUCMSCs provide several clinical advantages, including ethical accessibility, low immunogenicity, and abundant supply[8,10,11]. However, MSCs’ efficacy is often limited by inherent regulatory pa

Lv et al[9] employed a comprehensive approach combining molecular biology, cell culture, animal modeling, and multiple histological and biochemical assays. The authors employed a multi-target RNA interference approach, wherein several distinct shRNAs targeting different sites on the SOST mRNA were designed and tested to achieve efficient gene silencing. This strategy was validated by sequencing, fluorescence, and protein/mRNA expression analysis in hUCMSCs, ensuring effective genetic modification. The SANFH rat model was robustly established involving lipopolysaccharide and methylprednisolone injections, with histological confirmation of osteonecrosis. Treatment groups allowed direct comparison between unmodified MSCs and SOST-silenced MSCs. The use of micro-computed tomography provided a detailed quantitative analysis of bone microarchitecture. Furthermore, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and western blotting measured circulating and local regulatory factors central to bone remodeling, offering mechanistic insights.

The key findings of the study demonstrate that these modified stem cells maintained their typical fibroblast-like morphology and multilineage differentiation potential, as confirmed by flow cytometry and staining assays. Importantly, SOST expression was significantly reduced in sh-hUCMSCs, as validated by both western blot and quantitative real-time reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction analyses, without impairing the cells’ proliferative capacity, indicating the absence of cytotoxic effects due to gene silencing. The gene-silenced MSCs displayed enhanced osteogenic differentiation, marked by the upregulation of key osteogenic markers including alkaline phosphatase, osteoprotegerin (OPG), and runt-related transcription factor 2, while adipogenic markers such as peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma and CCAAT-enhancer-binding proteins were significantly downregulated. This shift in differentiation was consistently observed both in vitro and in vivo. Histological examinations revealed diminished adipocyte infiltration and increased deposition of new bone collagen in femoral heads treated with sh-hUCMSCs, reflecting a favorable remodeling environment.

Moreover, micro-computed tomography analyses uncovered marked improvements in bone microarchitecture in mice treated with sh-hUCMSCs. Specifically, there were significant increases in bone volume, trabecular number, and tra

The findings of Lv et al[9] suggest that SOST silencing in hUCMSCs may influence the Wnt/β-catenin signaling axis, as reflected by elevated β-catenin expression in bone tissue samples post-treatment. This study elucidates the mechanism whereby SOST silencing activates the Wnt/β-catenin signaling axis, leading to enhanced osteoblast differentiation and proliferation, and concurrent suppression of osteoclastogenesis via modulation of the OPG/RANK ligand/RANK axis. By repressing adipogenic differentiation, these modified MSCs prevent marrow fat expansion that exacerbates trabecular weakening. Clinically, sh-hUCMSCs could offer a cell-based regenerative therapy addressing SANFH’s underlying pathophysiology rather than merely symptomatic relief or structural replacement. Gene silencing techniques enhance MSCs’ therapeutic efficacy, highlighting the potential of precision genetic modification in stem cell therapy (Figure 1). These observed improvements in osteogenesis and inhibition of adipogenesis imply a potential role of Wnt pathway modulation, but further targeted studies are required to validate this mechanistic link.

While the findings of the present study are highly promising, several important limitations must be addressed to fully validate the therapeutic potential and safety of SOST-silenced MSCs in bone regeneration. Long-term safety, off-target effects, and immunogenic potential of gene-modified MSCs require thorough evaluation in larger preclinical models. It is crucial to assess possible off-target genetic modifications, as well as the immunogenicity of gene-edited MSCs, which may not manifest until extended post-transplant surveillance in larger and more diverse animal models. Another important limitation of the current study, as also acknowledged by Lv et al[9], is the lack of direct mechanistic evidence confirming the activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling following SOST silencing in hUCMSCs. Future investigations should employ targeted molecular analyses such as reporter assays, phosphorylation studies of β-catenin, and Wnt target gene profiling in isolated SOST-silenced hUCMSCs to substantiate this proposed pathway interaction. Further, the interaction between SOST inhibition and chondrogenic or cartilage remodeling pathways remains poorly understood; exploring this mo

Lv et al’s study[9] presents compelling evidence that silencing SOST in hUCMSCs robustly improves bone regeneration and metabolic balance in a steroid-induced femoral head necrosis model. This strategy leverages the intrinsic osteogenic potential of MSCs while overcoming inhibitory pathways through RNA interference, thereby activating Wnt/β-catenin signaling to drive bone repair. Such advancements epitomize the shift towards genetically enhanced stem cell therapies in orthopedics, which could revolutionize treatment paradigms for SANFH and related skeletal disorders. Further research and clinical translation hold promise for meaningful improvements in patients afflicted by this challenging condition.

| 1. | Chang C, Greenspan A, Gershwin ME. The pathogenesis, diagnosis and clinical manifestations of steroid-induced osteonecrosis. J Autoimmun. 2020;110:102460. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 174] [Article Influence: 29.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Motta F, Timilsina S, Gershwin ME, Selmi C. Steroid-induced osteonecrosis. J Transl Autoimmun. 2022;5:100168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Dashti-Khavidaki S, Saidi R, Lu H. Current status of glucocorticoid usage in solid organ transplantation. World J Transplant. 2021;11:443-465. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Roberts T, Penn A, Hanson L. Avascular Necrosis With Complete Fragmentation and Collapse of the Femoral Head Treated With Cementless Total Hip Arthroplasty: A Case Report. Cureus. 2025;17:e86976. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Birla V, Vaish A, Vaishya R. Risk factors and pathogenesis of steroid-induced osteonecrosis of femoral head - A scoping review. J Clin Orthop Trauma. 2021;23:101643. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Wang A, Ren M, Wang J. The pathogenesis of steroid-induced osteonecrosis of the femoral head: A systematic review of the literature. Gene. 2018;671:103-109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 138] [Article Influence: 17.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Tang H, Yuan L, Xu Z, Jiang G, Liang Y, Li C, Ding P, Qian M. Glucocorticoids induce femoral head necrosis in rats through the HIF-1α/VEGF signaling pathway. Sci Rep. 2025;15:29205. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Bandekar M, Maurya DK, Sharma D, Checker R, Gota V, Mishra N, Sandur SK. Xenogeneic transplantation of human WJ-MSCs rescues mice from acute radiation syndrome via Nrf-2-dependent regeneration of damaged tissues. Am J Transplant. 2020;20:2044-2057. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Lv H, Zheng CF, Chen XY, Wei JH, Tao YZ, Feng L, Feng Z, Lu SJ. Sclerostin-silenced human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells ameliorate bone metabolism in steroid-induced femoral head necrosis. World J Stem Cells. 2025;17:110190. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Weiss ML, Anderson C, Medicetty S, Seshareddy KB, Weiss RJ, VanderWerff I, Troyer D, McIntosh KR. Immune properties of human umbilical cord Wharton's jelly-derived cells. Stem Cells. 2008;26:2865-2874. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 420] [Cited by in RCA: 437] [Article Influence: 24.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 11. | Maurya DK, Bandekar M, Sandur SK. Soluble factors secreted by human Wharton's jelly mesenchymal stromal/stem cells exhibit therapeutic radioprotection: A mechanistic study with integrating network biology. World J Stem Cells. 2022;14:347-361. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Huang J, Ma T, Wang C, Wang Z, Wang X, Hua B, Jiang C, Yan Z. SOST/Sclerostin impairs the osteogenesis and angiogesis in glucocorticoid-associated osteonecrosis of femoral head. Mol Med. 2024;30:167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Vasiliadis ES, Evangelopoulos DS, Kaspiris A, Benetos IS, Vlachos C, Pneumaticos SG. The Role of Sclerostin in Bone Diseases. J Clin Med. 2022;11:806. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Ozawa Y, Takegami Y, Osawa Y, Asamoto T, Tanaka S, Imagama S. Anti-sclerostin antibody therapy prevents post-ischemic osteonecrosis bone collapse via interleukin-6 association. Bone. 2024;181:117030. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Li X, Ominsky MS, Niu QT, Sun N, Daugherty B, D'Agostin D, Kurahara C, Gao Y, Cao J, Gong J, Asuncion F, Barrero M, Warmington K, Dwyer D, Stolina M, Morony S, Sarosi I, Kostenuik PJ, Lacey DL, Simonet WS, Ke HZ, Paszty C. Targeted deletion of the sclerostin gene in mice results in increased bone formation and bone strength. J Bone Miner Res. 2008;23:860-869. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 719] [Cited by in RCA: 727] [Article Influence: 40.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/