Published online Feb 26, 2026. doi: 10.4252/wjsc.v18.i2.116184

Revised: November 28, 2025

Accepted: January 15, 2026

Published online: February 26, 2026

Processing time: 101 Days and 23.9 Hours

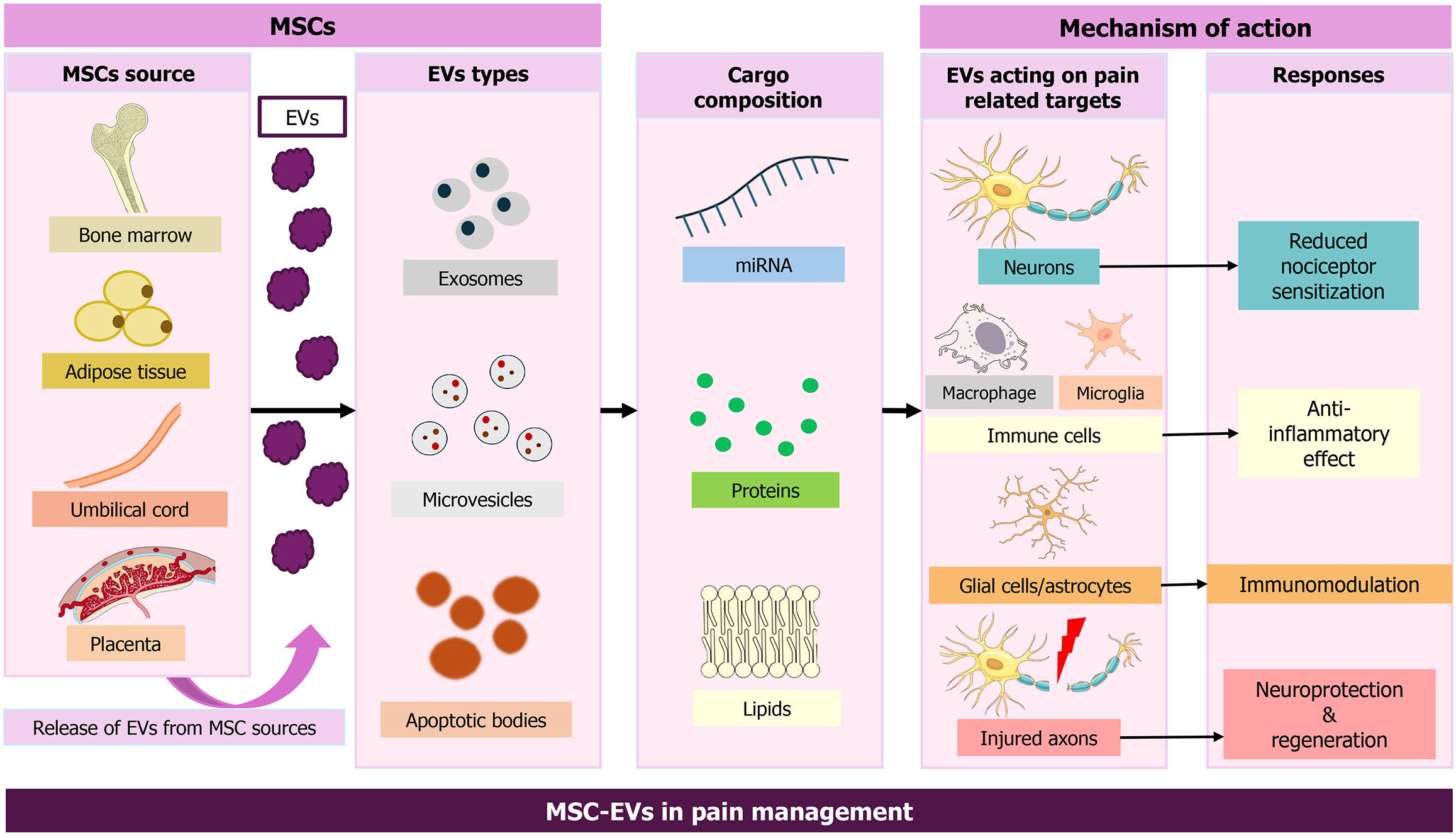

Pain remains a major clinical challenge because current therapies often have limited efficacy and substantial adverse effects. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles (MSC-EVs) are emerging as promising candidates with anti-inflammatory, immunomodulatory, and neuroprotective actions. Preclinical studies show that MSC-EVs alleviate inflammatory, neuropathic, and cancer-related pain by modulating immune responses and promoting neural repair, thereby reducing nociceptor sensitization. MSC-EVs also hold potential as drug-delivery vehicles and as biomarkers for pain diagnosis due to their stability and bioactive cargo (e.g., microRNAs and proteins). This narrative review summarizes terminology, mechanisms, therapeutic applications, and translational challenges of MSC-EVs in pain management, emphasizing their capacity to reshape the treatment landscape. Despite hurdles in scalable manufacturing, dosing, and regulation, ongoing clinical investigations support their promise as a biologically driven strategy for pain therapy.

Core Tip: This review summarizes the mechanistic and translational evidence on how mesenchymal stem cell-derived ex

- Citation: Khan SA, Gangadaran P, Tiwari P, Rajendran RL, Jamal A, Hattiwale SH, Anand K, Jha SK, Hong CM, Ahn BC, Parvez S. Therapeutic applications of mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles in pain management: A narrative review of emerging evidence and future directions. World J Stem Cells 2026; 18(2): 116184

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-0210/full/v18/i2/116184.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4252/wjsc.v18.i2.116184

Pain is a complex, subjective experience and a leading cause of disability worldwide[1]. According to the International Association for the Study of Pain, pain is an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage or described in terms of such damage[2]. Nociceptive input from dorsal root ganglion neurons, via peripheral nociceptor terminals, axons, and presynaptic terminals, converges on the central nervous system (CNS), where it is encoded and perceived as pain[3-5]. Acute pain serves as a protective signal, alerting the brain to potentially harmful stimuli such as injury, heat, or pressure. However, when pain persists beyond tissue healing, it becomes ma

Despite advances in medical science, effective pain control remains a global challenge. More than 30% of the world’s population experiences some form of pain[16]. Moreover, pain and opioid analgesic misuse, suicide, depression, and related conditions significantly impair quality of life and create substantial personal and economic burdens[17]. Traditional therapies - nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, opioids, and adjuvant medications - often provide only partial relief and are associated with adverse effects (e.g., gastrointestinal toxicity, organ injury), dependence, and limited long-term efficacy[18-20]. This therapeutic gap underscores the need for novel, safe, and targeted approaches to pain management.

Stem cell-based therapies offer a promising alternative[21]. Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) - adult mesoderm-derived stem cells - modulate immune responses, attenuate inflammation, and promote tissue repair, while retaining proliferative and multipotent capacity[22-24]. MSCs may reduce pain by dampening neuroinflammation and limiting glial and neuronal overactivation[25-27]. To date, MSCs have demonstrated efficacy in preclinical models and in clinical studies across multiple indications[28,29]. Their immunomodulatory properties are well established in preclinical research[30-32], and clinical data supports benefits in immune regulation among transplant recipients[33,34]. The low immunogenicity of MSCs supports allogeneic use and broadens clinical applicability in pain therapy. MSCs can be administered via local injection at the injury site or by intrathecal or intravenous (IV) routes. MSC homing is the process by which cells are recruited to injured tissues by cytokines, chemokines, adhesion molecules, and growth factors released from the local microenvironment[35-38].

Given the functional properties of MSCs, MSC-derived analgesic therapies have the potential to become a new ap

Given their inherent anti-inflammatory, neuromodulatory, and neuroprotective properties, MSC-EVs are emerging as potential therapeutics for pain management. By modulating nociceptors, supporting neural and tissue repair, and transporting therapeutic cargo, they offer a cell-free alternative to conventional medicines. The purpose of this review is to summarize recent data, mechanisms, and therapeutic uses of MSC-EVs in pain, emphasizing their possible use as biomarkers and drug delivery systems. Additionally, we highlight current challenges, translational barriers, and emer

EVs are categorized into three major types based on size and biogenesis: (1) Exosomes (30-150 nm), which originate from endosomes; (2) MVs, also called ectosomes, 100-1000 nm, which are derived from the plasma membrane; and (3) Apo

MSC-EVs include at least 730 distinct proteins, identified via liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry analysis[58,59], and display characteristics of both MSCs and EVs. For example, 25 proteins in MSC-EVs are associated with MSC differentiation genes, whereas 53 are linked to MSC self-renewal genes. One study showed that MSC-EV proteins include MSC surface markers and MSC-specific signaling proteins. Proteins in MSC-EVs also participate in EV biogenesis, trafficking, docking, and fusion. Modulation of MSC therapeutic potential has been attributed to EV proteins, including the surface receptors platelet-derived growth factor receptor-beta (PDGFR-β) and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR); signaling molecules from the RAS-mitogen-activated protein kinase, CDC42, and RHO pathways; cell-adhesion molecules; and other MSC antigens. These proteins may promote tissue regeneration and repair. Additionally, 171 microRNAs (miRNAs) have been identified in MSC-EVs, 23 of which target 5481 genes that regulate specific pathways. For example, miR-199a and miR-130a-3p are involved in preventing apoptosis, stimulating angiogenesis, and enhancing cellular proliferation. Furthermore, the proteome of purified MSC-derived exosomes has 938 distinct gene products encompassing diverse biochemical and cellular processes[58,59].

MSC-EVs also contribute to intercellular communication by delivering proteins, mRNAs, and miRNAs. Similar to MSCs, they play vital roles in both pathological and physiological processes, such as tissue repair and angiogenesis. MSC-EVs exhibit low immunogenicity and high stability, making them suitable for treating autoimmune diseases[60-62]. They can reprogram target cells, improving viability and migration, and have been reported to possess greater regenerative potential than intact stem cells[63]. Their molecular cargo supports disease monitoring, enabling MSC-EVs to serve as biomarkers. Multiple studies indicate that MSC-EVs show promise for treating rheumatoid arthritis and myocardial infarction, offering cell-free therapeutic approaches[60,64]. Additional advantages include targeted delivery, prevention of long-term maldifferentiation, and lower toxicity[65]. Further research focusing on process optimization is needed to unlock the full benefits of MSC-EVs in regenerative medicine[66].

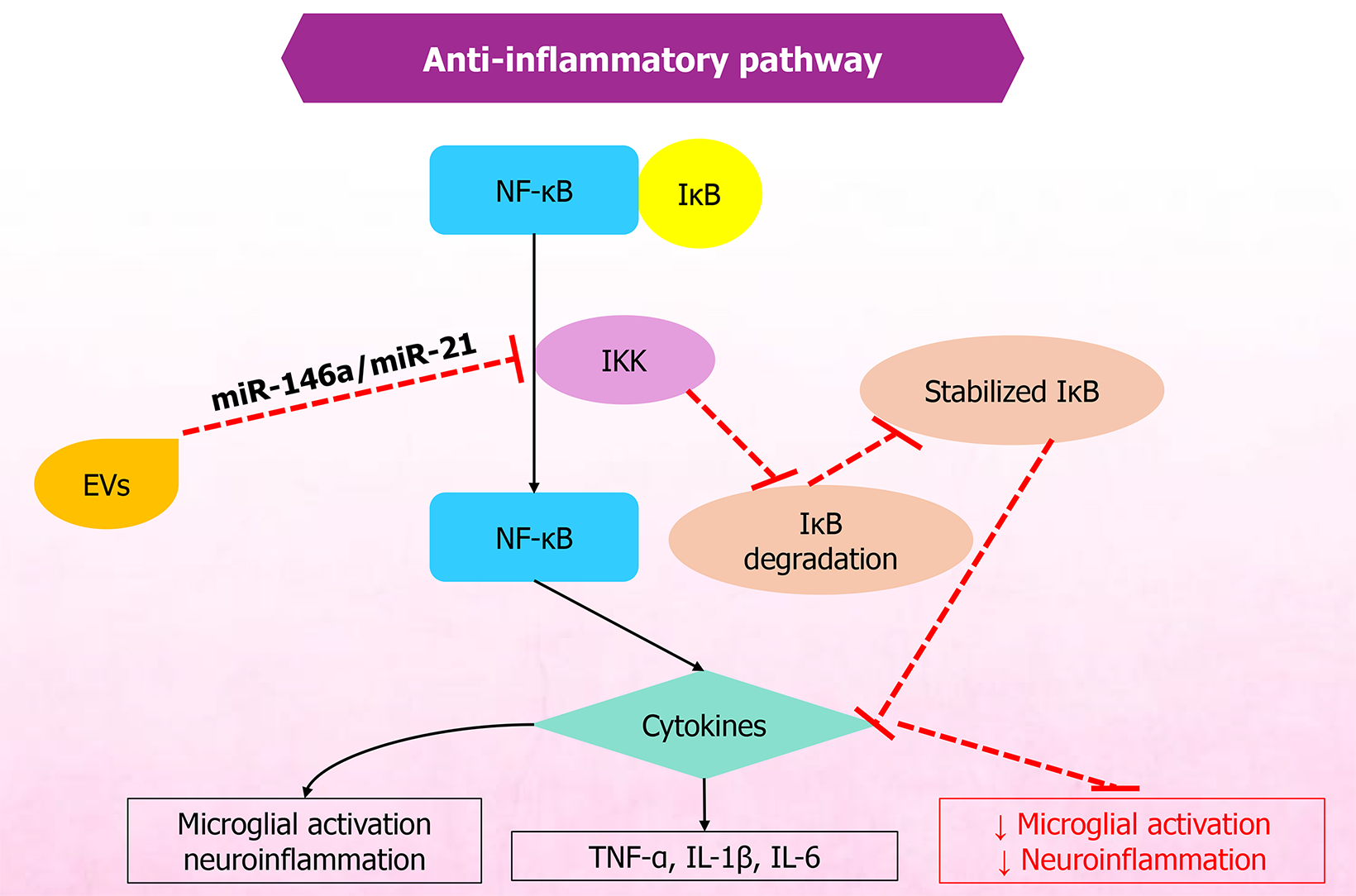

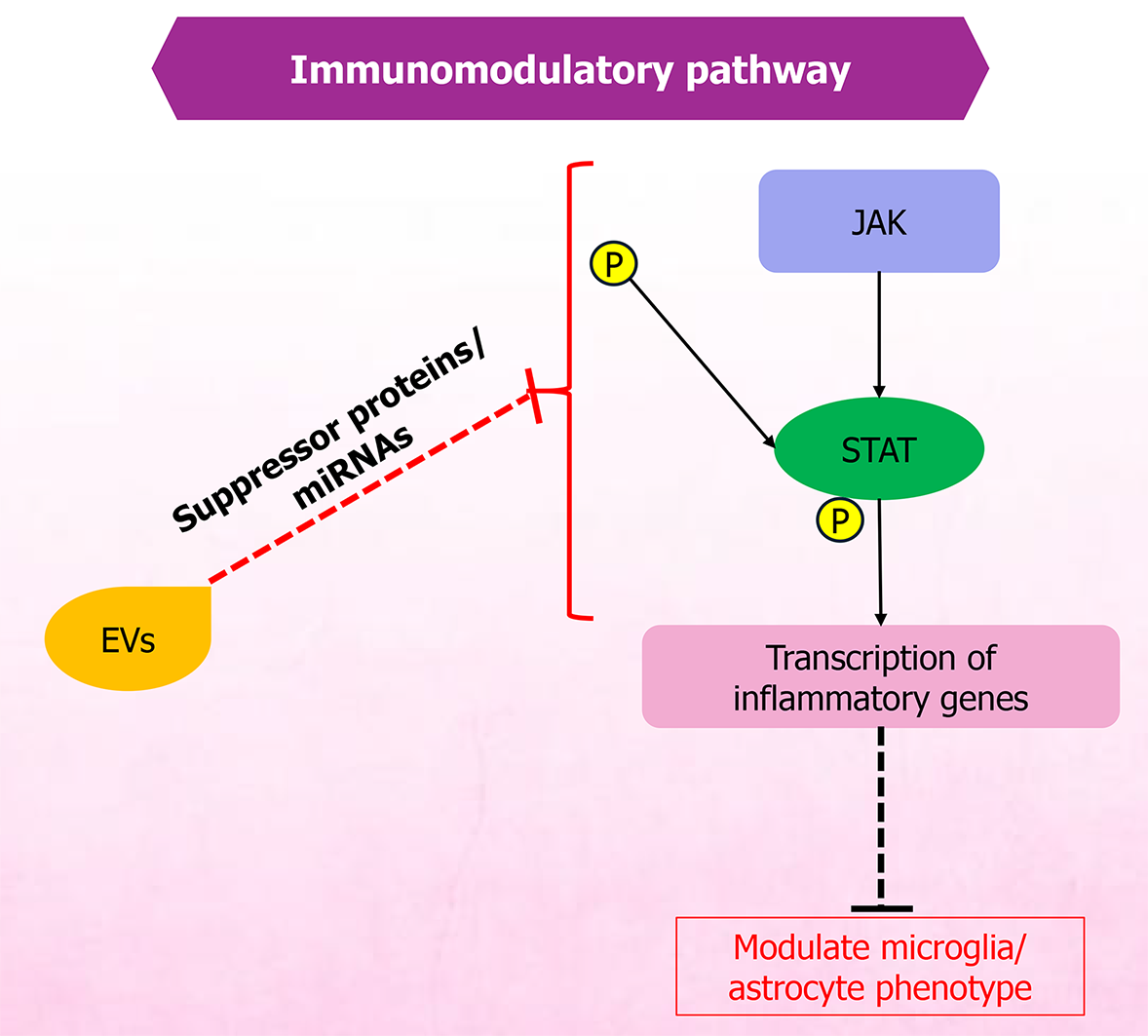

The immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory actions of MSC-EVs are tightly interconnected and are central to pain modulation. MSC-EVs are rich in bioactive cargo that can recalibrate immune responses, thereby reducing inflammation and associated pain. As potent mediators of immune regulation, MSC-EVs carry miRNAs, proteins, and lipids that modulate immune pathways affecting T cells, B cells, and macrophages implicated in pain and inflammation[67]. These immunomodulatory effects establish a pro-regenerative microenvironment that allows subsequent neural repair processes. A simplified overview of the anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory pathways is provided in Figures 1 and 2, respectively.

The anti-inflammatory effects of MSC-EVs depend on the transfer of immunoregulatory miRNAs and immunomodulatory proteins to inflammatory cells, including M1 macrophages, dendritic cells, CD4+ T cells, T helper 1 cells, and T helper 17 cells, thereby promoting transformation to immunosuppressive M2 macrophages, tolerogenic dendritic cells, and T regulatory cells. This, in turn, enhances immunosuppressive functions and decreases inflammation[68,69]. Furthermore, MSC-EVs inhibit the Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)/nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) pathway and NACHT, LRR and PYD domains-containing protein 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome activation in models of neuroinflammation, thereby reducing glial activation and proinflammatory cytokines and decreasing pain sensitivity and mechanical allodynia in conditions such as interstitial cystitis[70,71]. Moreover, miR-124-enriched MSC-EVs decrease proinflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), interleukin (IL)-6, and IL-1β, while increasing anti-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-10 and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β). These changes help balance immune responses, inhibit macrophage activation, reduce apoptosis and oxidative stress via delivered noncoding RNAs, mRNAs, and miRNAs, modulate pain pathways, and promote regeneration and pain relief in inflammation-related conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis (OA)[68,69,72,73].

Other studies have also shown the potential of MSC-EVs to reduce proinflammatory cytokine release, thereby pro

Despite consistent results of anti-inflammatory effects, findings across MSC-EVs remain difficult to compare, as EV isolation protocols are inconsistent and variable across studies, making it more challenging to even compare the immunomodulatory effects. Heterogeneity in EV cargo across MSC sources, and MSC culture conditions are also respon

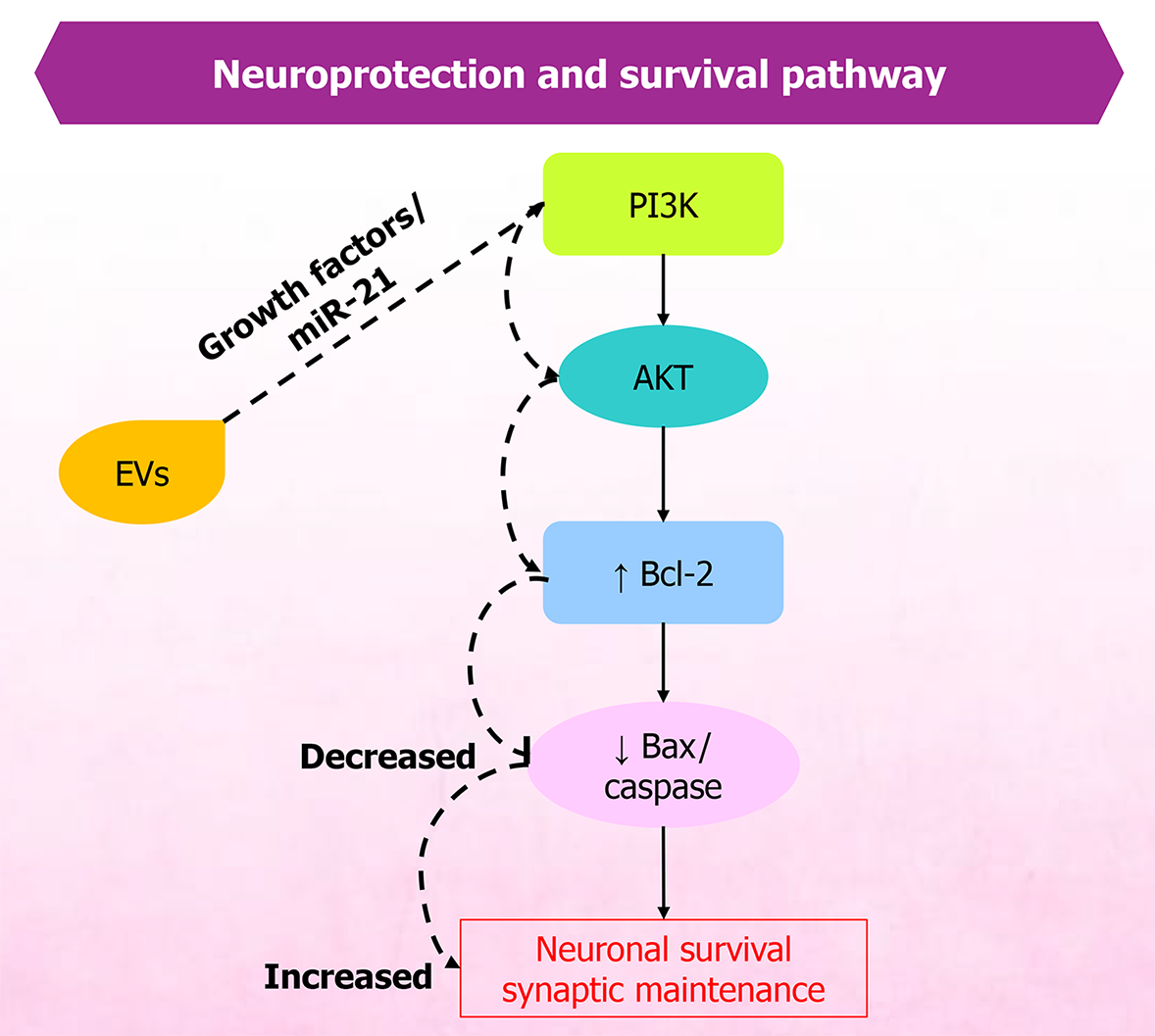

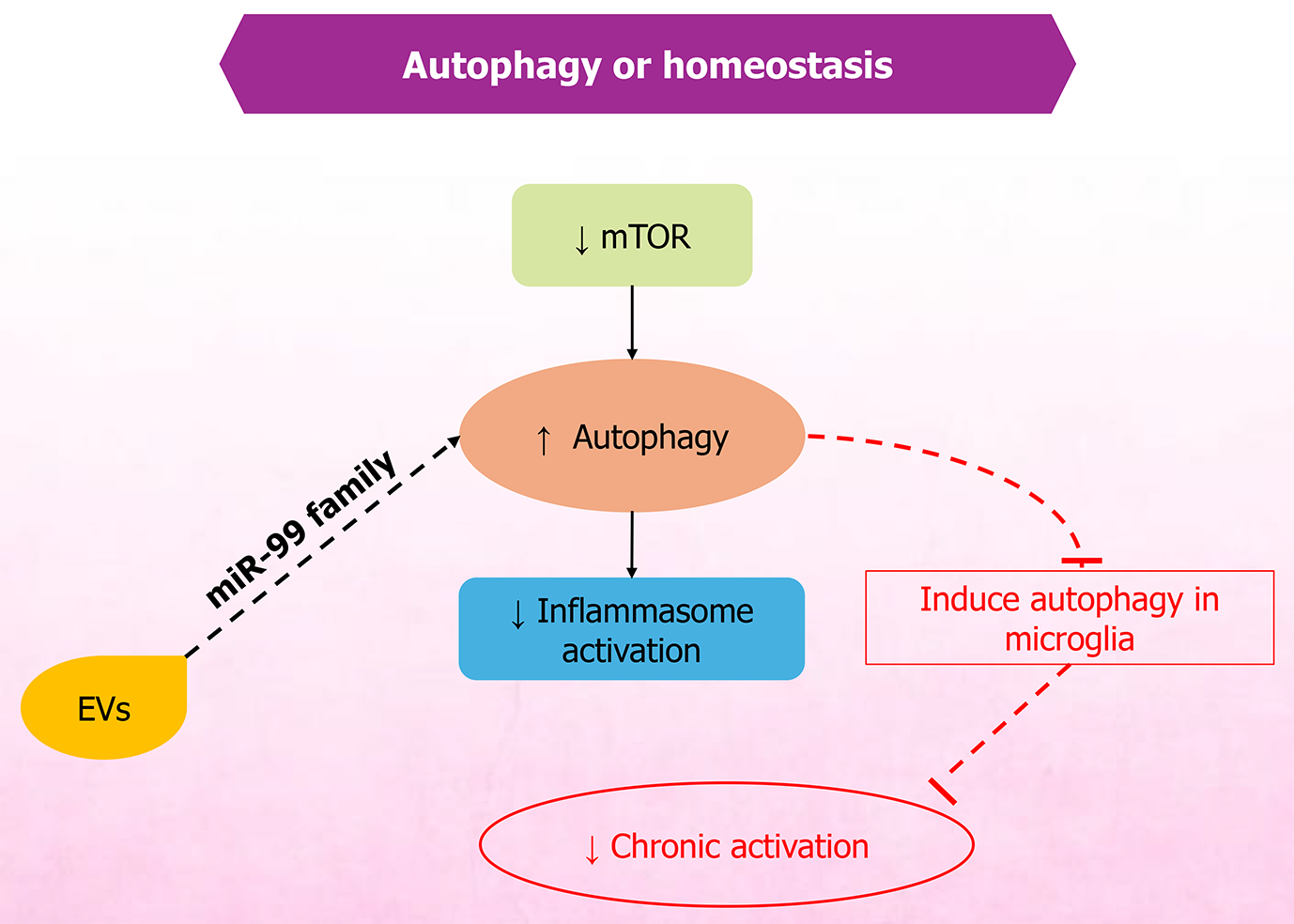

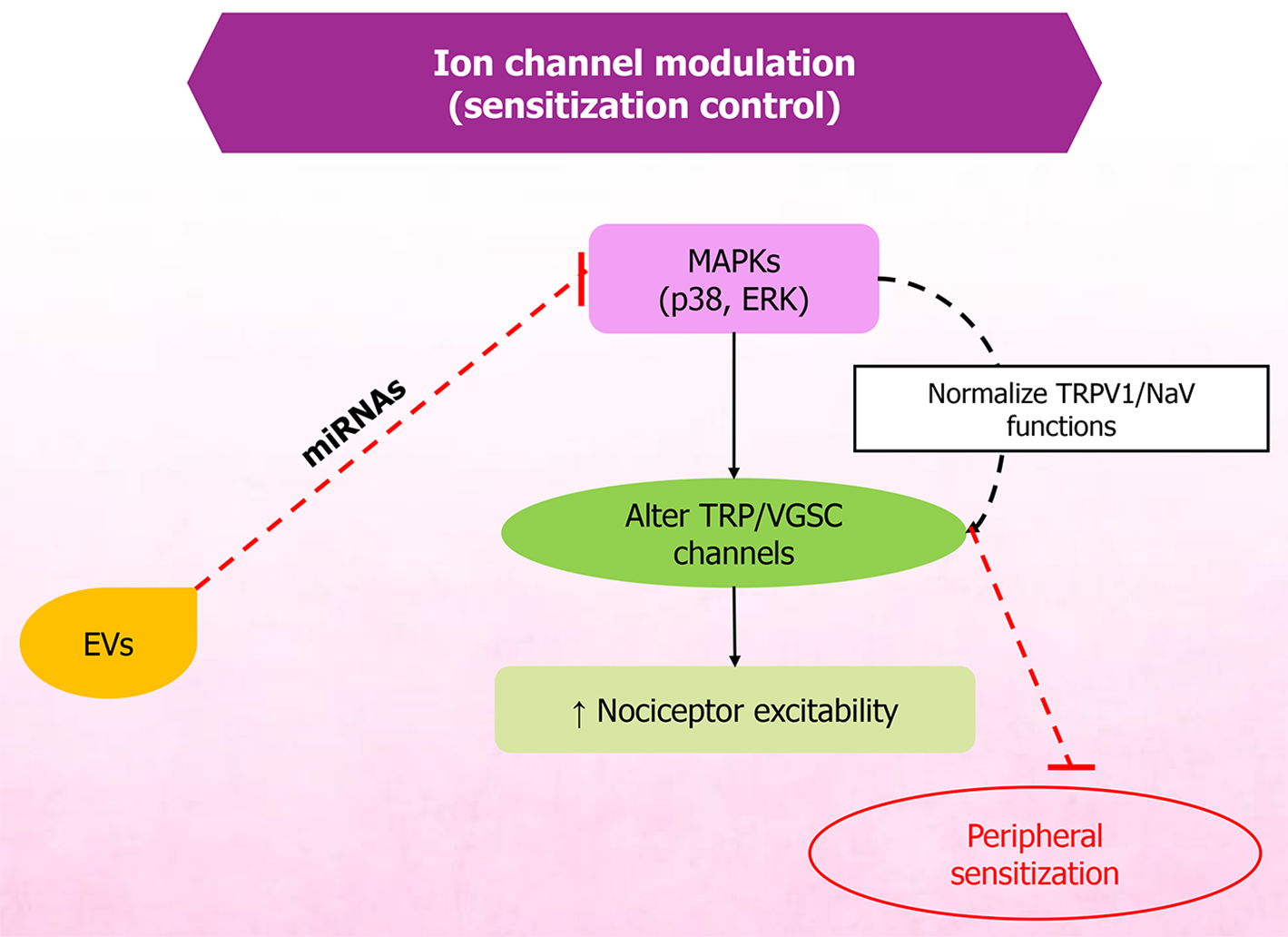

MSC-EVs have demonstrated the potential to mitigate pain and support recovery in conditions such as spinal cord injury and related disorders. Therapeutic effects are primarily attributed to EV cargo - particularly miRNAs - that regulate inflammation, oxidative stress, and neuronal excitability. Owing to their anti-inflammatory and regenerative properties, MSC-EVs support neuronal repair, neuroprotection (Figure 3), and homeostasis (Figure 4). Restoration of neural structure and synaptic function ultimately contributes to reduced nociceptor signaling (Figure 5). They reduce inflammation and modulate oxidative stress, thereby influencing apoptosis through exosomal miRNAs, which in spinal cord injury models decreases inflammation linked with pain and recovery processes[79]. MSC-EVs also enhance neuroprotection by modulating pathways such as phosphoinositide 3-kinase/protein kinase B, helping prevent neuronal death during ischemia. Studies further indicate that EV-mediated neuroprotection involves diverse paracrine factors and pathways[80,81].

Furthermore, MSC-EVs have been shown to normalize hyperexcitability in sensory neurons, suggesting direct action on peripheral sensory neurons to modulate pain-related behaviors in OA models[82]. These EVs have also shown utility for chronic pain, including chemotherapy-induced and degenerative-disease-related pain[48]. They also protect against intracerebral hemorrhage-induced neuronal damage by modulating ferroptosis, further suggesting therapeutic potential in brain disorders[83].

Although MSC-EVs have shown neuroprotective effects, most evidence is based on early treatment rodent models and high EV doses that may not be translationally realistic. Studies often fail to differentiate whether improvement arises from direct neuronal repair or secondary immune modulation process[84]. Additionally, bulk EV preparations restrict the potential to identify which EV subtypes or cargo components play roles in neuroprotection.

Nociceptors are sensory nerve endings in the skin, joints, muscles, and viscera that respond to noxious or potentially damaging stimuli. Nociceptors undergo sensitization, which increases their excitability. Sensitization typically follows tissue injury and inflammation, lowering activation thresholds and increasing response magnitude to a noxious stimulus, thereby rendering previously ineffective stimuli painful and promoting spontaneous activity[85,86].

Nociceptor sensitization is regulated by reciprocal signaling between immune cells and sensory neurons. Inflammatory mediators lower nociceptor thresholds during inflammation, driving peripheral sensitization. Mast cells release cytokines such as IL-5, IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-1β, as well as histamine and nerve growth factor, which activate transient receptor potential and voltage-gated sodium channels. This activation induces hyperalgesia[48,87,88]. Macrophages and mono

Nociceptors release neuropeptides such as substance P, vasoactive intestinal peptide, and calcitonin gene-related peptide, which mediate neurogenic inflammation through vasodilation and plasma extravasation, while simultaneously regulating immune cell functions and thereby shaping immune responses. For example, calcitonin gene-related peptide upregulates IL-10 and downregulates TNF-α in macrophages[94-99]. Together, this bidirectional neuroimmune process regulates the initiation, persistence, and resolution of pain and guides its management. Research on MSC-EV regulatory management of nociceptor sensitization is still preliminary. Differences in EV cargo and neuronal culture systems often yield conflicting data, whereas others show minimal effects. A few studies include neuroimmune interactions and hence limit the interpretation of how these results translate to chronic pain conditions.

Preclinical in vitro models have become key tools for advancing diverse research. In this context, they are essential for studying the therapeutic potential of EVs across pain conditions. These systems enable mechanism-based studies showing how EVs - especially exosomes - modulate pain by targeting key signaling pathways, thereby informing novel treatment approaches.

As described earlier, exosomes target inflammation and neuronal excitability through their molecular constituents, and thus, benefit chronic pain conditions like OA and neuropathic pain[100]. In vitro neuronal models assess the effects of exosomes on neuronal cells, providing insight into pain modulation and aiding phenotypic screening to identify pain-mitigating compounds[101]. EVs have also been investigated as potential alternatives to conventional cell-based therapies by modulating inflammatory responses and promoting tissue regeneration. Studies have shown that MSC-EVs effectively modulate pain pathways in animal models, indicating potential clinical applicability[76,102]. Moreover, MSC-EVs have produced significant analgesia in neuropathic pain models, including rat chronic constriction injury and mouse partial sciatic nerve ligation[103,104]. Their pain-modulating and regenerative properties also suggest applicability to cancer pain management[105]. Despite this promise, challenges in EV isolation, optimization, and characterization, as well as in elucidating mechanisms of action and therapeutic outcomes, necessitate further research to enable clinical translation[105,106]. Some preclinical studies were described earlier; a summary of recent work is presented in Table 1[48,82,103,104,107-111].

| MSC source | In vitro experimental model | In vivo experimental model | Pain type | Key findings (qualitative analysis) | Mechanistic outcomes | Ref. |

| Mouse bone marrow MSCs | - | Partial sciatic nerve ligation in male C57BL/6 | Neuropathic pain | MSCs produced long-lasting anti-nociception | Decreased IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6 | [103] |

| Reduced thermal hyperalgesia and mechanical allodynia | Increased IL-10 | |||||

| Secretome factors (VEGF, HGF chemerin, angiopoietin-1) mediating neuroprotection and immune modulation | ||||||

| Mouse bone marrow MSCs | - | Diabetic db/db mouse model | Neuropathic pain | Increased thermal and mechanical sensitivity | Suppressed inflammatory cytokines | [107] |

| Increased motor and sensory nerve conduction velocities | Macrophage polarization from M1 to M2 | |||||

| Increased intraepidermal nerve fiber density, myelin thickness, and axonemal diameter | Exosomal miRNAs targeted the TLR4/NF-κB pathway, reducing inflammation | |||||

| Reduced neuroinflammation and macrophage infiltration in the sciatic nerve | ||||||

| Rat bone marrow MSCs | IL-1β-treated rat chondrocytes | Rat OA model induced by sodium iodoacetate | Osteoarthritis pain | BMSC exosomes prolonged paw-withdrawal latency in OA rats | Reduced nociceptor mediator CGRP, decreasing neuronal sensitization | [108] |

| Reduced CGRP and iNOS protein levels in DRG tissue | Reduced iNOS and inflammation | |||||

| Indicated relief of both inflammatory and neuropathic components of pain | Modulated anti-inflammatory cytokines | |||||

| Protected cartilage, indirectly reducing pain drivers | ||||||

| hPMSCs | - | Nerve injury mouse model | Neuropathic pain | An intrathecal dose reversed mechanical allodynia | miR-26a-5p targeted Wnt5a and downstream Wnt5a/Ryk/CaMKII/NFAT signaling | [109] |

| Produced long-lasting analgesia | Reduced neuroinflammation | |||||

| Labeled EVs localized to microglia and neurons in the dorsal horn | Decreased TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 | |||||

| miR-26a-5p-rich hPMSC-EVs significantly reduced neuropathic pain and neuroinflammation | Inhibited microglial activation | |||||

| Mediated anti-neuroinflammatory and analgesic effects | ||||||

| hUC-MSCs | LPS and ATP-stimulated BV2 microglia | CFA-induced inflammatory pain in C57BL/6 mice | Inflammatory pain | hUC-MSC exosomes reduced mechanical allodynia and thermal hyperalgesia | Attenuated inflammation-driven pain via the miR-146a-5p/TRAF6/autophagy-pyroptosis axis | [110] |

| Reduced microglial activation and neuroinflammation | ||||||

| Increased autophagy | ||||||

| hUC-MSCs | LPS-stimulated BV2 microglia | CCI rat model | Neuropathic pain | MSC-EVs reduced pain | EV miR-99b-3p inhibited the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway | [104] |

| Reduced microglial activation and inflammation | Increased autophagy | |||||

| Restored autophagy via miR-99b-3p delivery | Reduced proinflammatory cytokines | |||||

| Human bone marrow MSCs | - | High-fat diet plus groove surgery in rats | Osteoarthritis pain | MSC-EVs reduced structural joint degeneration and inflammation more than MSCs | Lower immunogenicity; reduced inflammation and cartilage catabolism | [111] |

| EV-treated rats showed less cartilage damage, osteophytosis, synovitis, and pain-associated behavior | Synovitis drove pain and osteophyte formation | |||||

| Human bone marrow MSCs | NGF-sensitized DRG neurons | DMM-induced OA in mice | Osteoarthritis pain | Prevented pain-related behaviors | Direct action of MSC-EVs on sensory neurons normalized hyperexcitability | [82] |

| MSC-EVs prevented NGF-induced hyperexcitability in cultured DRG neurons in vitro | Reduced release of proinflammatory mediators in the joint environment | |||||

| hUC-MSCs | DRG primary culture from SD rats | Paclitaxel-induced peripheral neuropathy in C57BL/6J mice | Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy | Cannabidiol-loaded hUC-MSC-EVs reduced paclitaxel-induced mechanical allodynia and thermal hyperalgesia | AMPK pathway activation | [48] |

| Normalized mitochondrial function in DRG and spinal cord of treated mice | Increased mitochondrial function and bioenergetics | |||||

| Modulated oxidative stress and inflammation by upregulating Nrf2 and downregulating NF-кB | ||||||

| Provided additional regenerative support |

Preclinical MSC-EV studies often lack blinding, use small cohort sizes and apply inconsistent behavioral endpoints leading concerns for replication or reproducibility. Many neuropathic pain models vary widely, thereby limiting comparability. Moreover, in vivo biodistribution is rarely rigorously characterized, and the same is true for pharmacokinetic data. Dosing metrics vary widely, and most of the studies rely on single pain models, thus limiting generalizability. Publication bias is very likely, as only a few studies report negative results.

Clinical studies of MSC-EVs in the context of pain remain at an early stage and primarily focus on pain-related disorders or on safety and feasibility. Several phase I trials are evaluating intra-articular or local delivery of MSC-EV-based or exosome-based products for OA-related joint pain, whereas others are testing exosome injections for neuropathic pain, craniomaxillofacial neuralgia, and low back pain. Most of the translational studies are in their early phases with small sample sizes. The heterogeneity in EV preparations, doses, delivery routes and quality controls also plays a vital role in study success. There are no data for long term toxicity, safety or immunogenicity, making it difficult to properly carry out the trials. Additionally, there are no proper comparisons being made with existing pain treatments. Many studies lack robust control, and regulatory compliance differs, underscoring the requirement for larger, rigorously designed studies.

To date, the clinical landscape for MSC-EV-based pain interventions remains in early phases. After repeated searches and with various keywords, we identified only seven studies that are interventional in nature, mostly phase I or pilot designs with small sample sizes. The most rigorous published study is a randomized, triple blind clinical trial assessing a single intra-articular dose of placental MSC-EVs in knee OA patients (IRCT20210423051054N1). One study demonstrated insightful yet short term improvements in Visual Analogue Scale pain scores and functional outcomes without any serious data on adverse events. However, the study lacked mechanistic biomarkers, dose optimization and long-term evaluation that restricts confidence regarding the durability of the benefit[112]. In contrast, most of the other studies remain in recruitment or early safety-only phases. For example, a study on the intra-articular EV injections for OA (NCT06431152; NCT06466850; NCT05060107) have not yet reported clinical outcomes, suggesting the nascency of the field. Furthermore, the ExoFlo epidural pilot for lumbar/cervical radiculopathy includes only ten participants and is currently reported solely in conference proceedings without any peer reviewed outcome confirmation. Table 2 sum

| Study start year | Trial/study ID | Pain condition | Phase | Estimated enrollment | Intervention | Source |

| 2024 | NCT06431152 | Knee osteoarthritis | Phase I | 12 | Intra-articular small EVs from umbilical cord MSCs | ClinicalTrials.gov |

| 2024 | NCT06466850 | Osteoarthritis | N/A | 20 | Intra-articular MSC-derived exosomes | ClinicalTrials.gov |

| 2021 | NCT05060107 | Knee osteoarthritis | Phase I | 10 | Single intra-articular MSC-derived exosome injection | ClinicalTrials.gov |

| 2023 | NCT04202783 | Craniofacial neuralgia | Early phase (safety and efficacy) | 100 | Intravenous infusion of exosomes | ClinicalTrials.gov |

| 2021 | NCT04849429 | Chronic low back pain (discogenic; intradiscal approach) | Phase I | 30 | Intradiscal injection of platelet-rich plasma with exosomes | [113] |

| 2022 (approved year) | IRCT20210423051054N1 | Knee osteoarthritis | Randomized, triple-blind clinical trial | 31 | Single intra-articular injection of placental MSC-EVs | [112] |

| - | ExoFlo interlaminar epidural safety study | Lumbar or cervical radiculopathy | Small open safety pilot study | 10 | Epidural injection of BM-MSC-EV isolate (ExoFlo); safety pilot | [114] |

The heterogeneity in administration approaches suggests a lack of consensus on optimal biodistribution. IV infusion is being evaluated for craniofacial neuralgia (NCT04202783), hypothesized to reach injured trigeminal branches through the systemic circulation and immune neuroinflammatory alteration. This remains speculative, as IV delivery may suffer from pulmonary trapping and may not efficiently reach the nerves. Therefore, direct comparisons with methods like perineural and intra-ganglionic delivery are required. On the other hand, intradiscal or intra-articular approaches (NCT04849429 for discogenic pain) aim to maximize local tissue exposure but encounter various challenges, including mechanical leakage, rapid clearance and unknown retention. Table 2 summarizes the reported trials[112-114].

Despite strong biological plausibility, clinical translation barriers remain substantial. Table 3 provides a concise summary of current challenges and concerns associated with that challenge. Without addressing the mentioned gap (Table 3), efficacy effects will remain ambiguous even if early safety seems promising. Therefore, MSC-EV therapeutics should be regarded as investigational in some respects, with safety profiles currently outpacing true and clear evidence of translational benefits. Stronger trial designs using standardized potency metrics and longer follow-up are essential before the therapeutic positioning can be justified.

| Challenges | Concerns |

| Study design | Lack of placebo/sham controls; open label designs dominate |

| Limited inference of true clinical effect | |

| Follow up duration | < 6 months endpoints |

| Short for chronic pain assessment | |

| Dosing and potency | No standardized unit of potency |

| Prevents cross-trial comparison | |

| Manufacturing | Heterogeneity in EV isolation protocols, and hence, unpredictable therapeutic consistency |

| Inconsistent EV product quality | |

| Inconsistent therapeutic predictability | |

| Regulatory | Unclear categorization (biologic vs cell-derived drug vs advanced therapy) |

| Unclear oversight requirements |

MSC-EVs are increasingly recognized as a versatile drug-delivery platform for pain management. Their favorable size distribution, intrinsic biocompatibility, ability to traverse biological barriers, capacity to carry bioactive cargo, and low immunogenicity provide advantages over traditional nanocarriers. These EVs can be engineered to display specific ligands, such as streptavidin, which bind biotinylated drugs and enhance targeting to specific cells or tissues[115]. Other approaches, such as pH-sensitive fusogenic peptide modification, allow MSC-EVs to release cargo in inflamed tissues[115,116].

Engineering strategies for MSC-EVs generally fall into two categories: (1) Cargo-loading approaches (passive incubation, electroporation, sonication, or chemical permeabilization) that encapsulate small molecules, peptides, or small interfering RNAs (siRNAs); and (2) Surface-modification approaches that attach peptides, antibodies, or aptamers to EV membranes to improve tissue targeting and therapeutic specificity. For example, engineered EVs loaded with siRNAs or analgesic peptides have shown promise in preclinical models of neuropathic and inflammatory pain, where they su

Compared with synthetic nanoparticles, MSC-EVs provide several benefits in drug delivery systems like better biocompatibility, intrinsic target based on membrane proteins and reduced clearance by mononuclear phagocyte system, characteristic features that widen their translational potential in pain management. Their lipid bilayer membrane provides protection for the cargo against degradation, while the intrinsic proteins and miRNAs help in cellular uptake, enhancing therapeutic efficacy[121-124]. Also, MSC-EVs shows better stability and longer half-life compared to liposomes, which can be prone to degradation[125]. Unlike polymeric nanoparticles that require complex engineering for drug release, MSC-EVs naturally alter therapeutic effects through their cargo, thereby providing a more integrated approach to pain management[126]. In contrast to the polymeric nanoparticles or liposomes, MSC-EVs are much less likely to cause any adverse immune reactions; instead they can synergize their own endogenous cargo, which includes regenerative and anti-inflammatory molecules[49]. Additional advantages include low or no toxicity and improved tissue penetration across barriers such as the BBB. MSC-EVs can also be bioengineered to evade immune clearance, e.g., by expressing CD47[127].

Despite various benefits, there are several limitations that create obstruction in clinical translation. Drug loading efficiency remains low and inconsistent, with active methods often causing EV membrane damage or even cargo leakage[128]. Heterogeneity in EV population and difficulty in large-scale, reproducible isolation complicates the standardized dose process. Additionally, ensuring stability during storage and transport as well as regulatory concerns regarding safety, identity and potency remail unsolved mystery[129]. Further, the efficient drug loading and long-term stability of MSC-EVs remain tough to achieve. Evidence of BBB/blood spinal-cord barrier crossing is mixed with disease state and EV source affecting transport[130]. In the context of pain management, available data remain relatively low compared with oncology or neurodegenerative research. While preclinical studies in models of neuropathic or inflammatory pain have shown promising analgesic results via MSC-EVs, evidence specific to chronic pain syndrome, cancer pain or clinical application in very much limited.

Emerging bioengineering approaches that include synthetic EV mimetics, hybrid EV nanoparticles and 3D cell culture systems, hold promises to overcome the major limitations of EV therapy, particularly in regenerative medicine and pain management. Natural EV production is usually low and biodistribution non-specific, which hinders dosing and targeting in inflammatory, neuropathic or cancer pain models. To address this issue, EV mimetics like ‘nanoghosts’ or cell-membrane nanovesicles can be engineered at scale with EV-like contents. For example, sonication-derived MSC nanoghosts generated approximately twice as many vesicles per cell than native MSC-EVs, while retaining key bioactive proteins[131]. These mimetics can be loaded with analgesic cargo and targeting ligands to provide a place for injured nerves or inflamed tissue. Basically, synthetic EV mimetics can be produced using top-down approaches, improving yield while retaining biological properties like natural EVs[132]. Moreover, EV mimetics can be engineered to have better targeting abilities by incorporating specific peptides or antibodies, which can lead them to pain-affected tissues[133]. Likewise, hybrid nanoparticles that fuse EV membranes or surface proteins with synthetic cores/Liposomes combine EV tropism with tunable payloads and stability. One such example is the cartilage-targeted EV-liposome hybrids that have successfully achieved increased retention and sustained anti-inflammatory action in osteoarthritic joints[134,135]. Therefore, hybrid nanoparticles that integrate EV characteristics can achieve immune evasion and prolonged circulation, thus making them suitable for targeted drug delivery in various pain models. Therapeutic agents can be loaded into these nanoparticles, improving their efficacy in managing pain through the administration of drugs to the exact locations[136]. Furthermore, 3D culture platforms like spheroids, scaffold-based bioreactors and organoids significantly boost EV yield and function. This is because they provide a more physiologically relevant environment for pain mechanisms studies and testing EV-based therapies, and this will likely lead to a better result in preclinical models[137]. For example, dental-MSC spheroids grown in a 3D hydrogel produced approximately six times more exosomal protein than identical cells in 2D[135], and the EVs showed better regenerative effects. When combined with engineered EVs, the 3D systems can drive and enhance tissue regeneration while also alleviating pain by mimicking the natural extracellular matrix[133]. These systems have the potential to provide clinically relevant EV doses through any delivery route and allow for surface engineering (peptides or antibodies) to concentrate EVs at pain sites by enabling high-volume production. Above all, preliminary translational studies imply that EVs can relieve pain. In a clinical study in 2025 on the use of MSC-EVs in thumb joint OA, the intra-articular injection of MSC-EVs significantly decreased pain scores during the course of 1 year[135]. Hence, synthetic EV mimetic, hybrid carriers and 3D biomanufacturing together could provide better yield and generate targeted EV therapies for broader pain indications.

The intersection of EVs and pain management encompasses two distinct but complementary areas: (1) The analysis of patient-derived circulating EVs as diagnostic biomarkers (liquid biopsy); and (2) The profiling of MSC-EVs to predict therapeutic potency. Liquid biopsy procedures using EVs have demonstrated better sensitivity and specificity compared with conventional diagnostic techniques, especially in terms of cancer that is now translating to pain medicine[138]. In the context of pain, circulating EVs, derived primarily from neurons, glial cells, and immune cells rather than MSCs, carry specific protein and miRNA signatures that reflect the pathological state. For example, circulating miRNAs exhibit altered expression in chronic pain conditions and offer stability that allows for retrospective studies by the utilization of archived samples[139]. These signatures assist in categorizing patients based on severity and identifying specific pain phenotypes, potentially acting as objective metrices for pain, a condition historically reliant on subjective self-reporting and moni

Unlike patient-derived EVs used for diagnosis, MSC-EVs are primarily used as therapeutic agents. However, the proper analysis of their molecular cargo i.e., biomarker profiling, is crucial for predicting their therapeutic efficacy outcomes, often referred to as “potency marking”. For example, MSC-EVs are rich in some specific miRNAs, such as miR124 and miR9, which have shown anti-inflammatory effects in pain models of arthritis and interstitial cystitis by the regulation of various inflammatory pathways[71,73].

Consequently, characterizing the levels of these miRNAs within MSC-EVs serves as a quality control biomarker to ensure the batch will be effective prior to its administration. While the detection of endogenous MSC-EVs in patient blood for diagnostics remains theoretical and technically challenging due to their low abundance relative to hematopoietic EVs, the profiling of exogenous or therapeutic MSC-EVs provides a “fingerprint” of their immunomodulatory potential[44,141]. Furthermore, modified MSC-EVs are being explored in theragnostic, simultaneously delivering analgesia while carrying imaging agents to monitor or track retention in injured tissues[142,143].

Despite the promise of circulating EVs as diagnostic tools and MSC-EV cargo as potency markers, significant cha

Successful clinical translation of MSC-EVs for pain management requires rigorous study designs and compliant re

Manufacturing clinic grade MSC-EVs remains a major challenge, as it is very expensive. For example, one analysis estimated that producing a 5 × 1012 EV lot (approximately 125 human doses of about 4 × 1010 EVs) costs on the order of $1 million, equaling roughly $8000 per dose[149]. Purification using ultracentrifugation, tangential flow filtration, chromatography and extensive quality control with sterility, identity, purity, potency, etc. add substantially to the cost. Even the use of automated bioreactors only modestly reduces costs. One study found only approximately $1000 per dose savings using a 3D closed system[150], and consumables/Labor remains costly. Thus, the “cost of gold” per MSC-EV dose often runs into the tens of thousand dollars.

Scaling EV production poses additional technical and biological hurdles. Ultracentrifugation-based workflows are poorly suited for clinical manufacturing, whereas tangential-flow filtration coupled with size-exclusion chromatography can improve yield while limiting vesicle damage. Nonetheless, heterogeneity arising from source-cell selection, culture conditions, and suboptimal purification remains a major determinant of cost and reproducibility[147,151]. The scale-up is also limited by yield. Conventional 2D flask culture produces about 107-109 EVs per liter, only thereby forcing large cultures to obtain a therapeutic dose. Methods like bioreactor methods (hollow-fiber, microcarriers or stirred up tanks) can boost yield, as reports cite (5-140) × higher EV recovery vs flasks, and closed systems permit cGMP production. However, making ≥ 1011 EVs per batch still requires massive cell banks and large volumes. Every scale-up step must meet strict GMP standards, thereby adding complexity[152-155]. Downstream isolation is a bottleneck: Ultracentrifugation is not scalable, and while tangential flow filtration is more scalable, it requires expensive equipment and still yields limited concentration gains. Also, dosing is very important and in pain and injury models, as rodents are usually treated with approximately 109-1010 EVs/kg. Allometric scaling, meaning body-surface area scaling, implies a human equivalent dose on the order of 1011-1012 EVs for a 70 kg patient[156-158]. Such large doses stretches manufacturing capacity and cost. Route of administration further influences dose; IV delivery helps achieve better EV distribution, necessitating high total doses, whereas localized routes can achieve therapeutic concentrations with far fewer EVs[159].

Additionally, safety concerns specific to pain indications also warrant scrutiny, including risks of protumorigenic or profibrotic signaling, unintended immunomodulation, and off-target distribution, necessitating long-term preclinical evaluation[148]. Moreover, factors underlying clinical failures with MSCs include poor quality control and variability in immunocompatibility, differentiation, and migratory capacity[160].

Future directions include synthetic EV mimetics, surface engineering, nucleic-acid loading, and designer EVs to enhance cargo loading and targeting, enabling delivery of analgesics, siRNAs, or neurotrophic factors[161,162]. However, these strategies introduce additional quality-control and regulatory challenges, such as immunogenicity and novel impurities, that require systematic head-to-head comparisons with natural EVs and early-phase clinical study designs. Identifying key therapeutic miRNAs within MSC-EVs and optimizing their production may further enhance efficacy[79,142]. Ultimately, coordinated efforts across academia, industry, and regulators - adhering to Minimum Information for Studies of Extracellular Vesicles-aligned standards, validated potency and safety assays, and GMP-compatible bioprocessing - are needed to transition MSC-EVs from promising preclinical candidates to reliable, approved pain therapies.

MSC-EVs have surfaced as a promising therapeutic approach for pain management in the preclinical setting due to their potential to modulate the critical molecular and cellular pathways underlying nociception, but they still require robust clinical validation. Preclinical evidence indicates that MSC-EVs downregulate proinflammatory mediators - particularly IL-1β and TNF-α - while upregulating anti-inflammatory cytokines such as TGF-β and IL-10. Their regenerative effects are also associated with reduced glial activation, thereby attenuating peripheral and central sensitization in models of neuropathic, inflammatory, and cancer pain. Furthermore, EV-borne miRNAs and proteins regulate apoptosis, oxidative stress, and synaptic plasticity, promoting neuronal survival, axonal regeneration, and functional recovery. MSC-EVs also facilitate tissue repair by delivering growth factors and regulatory RNAs that enhance cartilage regeneration and mitigate pain. MSC-EVs have not only shown potential in OA and neuropathic pain in the preclinical phase, but also in a variety of other pains like chronic pain, thereby suggesting avenues to reshape pain management paradigms (Figure 6). Also, further studies are required for the successful transition of the preclinical to clinical phase, and more importantly, to late clinical phases, as almost no studies have reached phase III.

MSC-EVs possess intrinsic therapeutic activity and can function as biocompatible nanocarriers for targeted drug delivery. Their lipid bilayer confers stability and helps evade immune surveillance. Engineering approaches enable drug loading and efficient delivery of analgesics, siRNAs, and peptides to target tissues, often with greater efficacy than synthetic nanoparticles. Meanwhile, different engineering approaches are utilized to allow the drug loading processes and effective delivery of analgesics, siRNAs and peptides to its target with greater efficacy. EV-linked molecular si

Despite substantial progress, significant challenges remain, including EV heterogeneity, limitations in isolation and evaluation methods, scalability, dosing reliability, and long-term safety. Furthermore, despite promising preclinical results, there is a lack of clinical studies validating these findings in human subjects, necessitating further research. Moreover, priority should be given to placebo-controlled phase II trials in diseases like OA with at least ≥ 1 year follow up. It is crucial to address all the related concerns for the translational application of EV based therapies. Moreover, despite promising preclinical results, clinical validation in humans is limited and warrants further study. Addressing these issues is crucial for the translational application of EV-based therapies. To realize clinical value, well-designed mechanistic studies, standardized manufacturing procedures, and carefully controlled clinical trials are needed. Thus, MSC-EVs can be utilized as a versatile and multifunctional therapeutic platform and possess the potential to change the landscape of pain in future.

| 1. | Rahman S, Kidwai A, Rakhamimova E, Elias M, Caldwell W, Bergese SD. Clinical Diagnosis and Treatment of Chronic Pain. Diagnostics (Basel). 2023;13:3689. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Raja SN, Carr DB, Cohen M, Finnerup NB, Flor H, Gibson S, Keefe FJ, Mogil JS, Ringkamp M, Sluka KA, Song XJ, Stevens B, Sullivan MD, Tutelman PR, Ushida T, Vader K. The revised International Association for the Study of Pain definition of pain: concepts, challenges, and compromises. Pain. 2020;161:1976-1982. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2257] [Cited by in RCA: 2637] [Article Influence: 439.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Yam MF, Loh YC, Tan CS, Khadijah Adam S, Abdul Manan N, Basir R. General Pathways of Pain Sensation and the Major Neurotransmitters Involved in Pain Regulation. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19:2164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 451] [Cited by in RCA: 370] [Article Influence: 46.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Ahimsadasan N, Reddy V, Khan Suheb MZ, Kumar A. Neuroanatomy, Dorsal Root Ganglion. 2022 Sep 21. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Berta T, Qadri Y, Tan PH, Ji RR. Targeting dorsal root ganglia and primary sensory neurons for the treatment of chronic pain. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2017;21:695-703. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 196] [Article Influence: 21.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Cheng J. Mechanisms of Pathologic Pain. In: Cheng J, Rosenquist R. Fundamentals of Pain Medicine. Cham: Springer, 2018. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 7. | Zhang YH, Adamo D, Liu H, Wang Q, Wu W, Zheng YL, Wang XQ. Editorial: Inflammatory pain: mechanisms, assessment, and intervention. Front Mol Neurosci. 2023;16:1286215. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Prescott SA, Ratté S. Chapter 23 - Somatosensation and Pain. In: Conn's Translational Neuroscience. United States: Academic Press, 2017: 517-539. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 9. | Cancer Pain (PDQ®): Health Professional Version. 2025 Apr 24. In: PDQ Cancer Information Summaries [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Cancer Institute (US); 2002 . [PubMed] |

| 10. | Pharmacological Interventions for Chronic Pain in Pediatric Patients: A Review of Guidelines [Internet]. Ottawa (ON): Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health; 2020. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Lucas JW, Sohi I. Chronic Pain and High-impact Chronic Pain in U.S. Adults, 2023. NCHS Data Brief. 2024;CS355235. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Yong RJ, Mullins PM, Bhattacharyya N. Prevalence of chronic pain among adults in the United States. Pain. 2022;163:e328-e332. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 180] [Cited by in RCA: 525] [Article Influence: 131.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | McGeeney BE. Pharmacological management of neuropathic pain in older adults: an update on peripherally and centrally acting agents. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;38:S15-S27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Gangadhar M, Mishra RK, Sriram D, Yogeeswari P. Future directions in the treatment of neuropathic pain: a review on various therapeutic targets. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2014;13:63-81. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Meacham K, Shepherd A, Mohapatra DP, Haroutounian S. Neuropathic Pain: Central vs. Peripheral Mechanisms. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2017;21:28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 181] [Cited by in RCA: 310] [Article Influence: 38.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Al-Mahrezi A. Towards Effective Pain Management: Breaking the Barriers. Oman Med J. 2017;32:357-358. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Cohen SP, Vase L, Hooten WM. Chronic pain: an update on burden, best practices, and new advances. Lancet. 2021;397:2082-2097. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 274] [Cited by in RCA: 1501] [Article Influence: 300.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Ghlichloo I, Gerriets V. Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs). 2023 May 1. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Virgen CG, Kelkar N, Tran A, Rosa CM, Cruz-Topete D, Amatya S, Cornett EM, Urits I, Viswanath O, Kaye AD. Pharmacological management of cancer pain: Novel therapeutics. Biomed Pharmacother. 2022;156:113871. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Queremel Milani DA, Davis DD. Pain Management Medications. 2023 Jul 3. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Padda J, Khalid K, Zubair U, Al Hennawi H, Yadav J, Almanie AH, Mehta KA, Tasnim F, Cooper AC, Jean-Charles G. Stem Cell Therapy and Its Significance in Pain Management. Cureus. 2021;13:e17258. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Abdelrazik H, Giordano E, Barbanti Brodano G, Griffoni C, De Falco E, Pelagalli A. Substantial Overview on Mesenchymal Stem Cell Biological and Physical Properties as an Opportunity in Translational Medicine. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:5386. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Wu X, Jiang J, Gu Z, Zhang J, Chen Y, Liu X. Mesenchymal stromal cell therapies: immunomodulatory properties and clinical progress. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2020;11:345. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 213] [Cited by in RCA: 225] [Article Influence: 37.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Li J, Wu Z, Zhao L, Liu Y, Su Y, Gong X, Liu F, Zhang L. The heterogeneity of mesenchymal stem cells: an important issue to be addressed in cell therapy. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2023;14:381. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 33.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Lee SY, Lee SH, Na HS, Kwon JY, Kim GY, Jung K, Cho KH, Kim SA, Go EJ, Park MJ, Baek JA, Choi SY, Jhun J, Park SH, Kim SJ, Cho ML. The Therapeutic Effect of STAT3 Signaling-Suppressed MSC on Pain and Articular Cartilage Damage in a Rat Model of Monosodium Iodoacetate-Induced Osteoarthritis. Front Immunol. 2018;9:2881. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Gao X, Gao LF, Zhang YN, Kong XQ, Jia S, Meng CY. Huc-MSCs-derived exosomes attenuate neuropathic pain by inhibiting activation of the TLR2/MyD88/NF-κB signaling pathway in the spinal microglia by targeting Rsad2. Int Immunopharmacol. 2023;114:109505. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Rahbaran M, Zekiy AO, Bahramali M, Jahangir M, Mardasi M, Sakhaei D, Thangavelu L, Shomali N, Zamani M, Mohammadi A, Rahnama N. Therapeutic utility of mesenchymal stromal cell (MSC)-based approaches in chronic neurodegeneration: a glimpse into underlying mechanisms, current status, and prospects. Cell Mol Biol Lett. 2022;27:56. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Lu W, Allickson J. Mesenchymal stromal cell therapy: Progress to date and future outlook. Mol Ther. 2025;33:2679-2688. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 23.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Han X, Liao R, Li X, Zhang C, Huo S, Qin L, Xiong Y, He T, Xiao G, Zhang T. Mesenchymal stem cells in treating human diseases: molecular mechanisms and clinical studies. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2025;10:262. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 41.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (15)] |

| 30. | Anggelia MR, Cheng HY, Lai PC, Hsieh YH, Lin CH, Lin CH. Cell therapy in vascularized composite allotransplantation. Biomed J. 2022;45:454-464. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Norte-Muñoz M, García-Bernal D, García-Ayuso D, Vidal-Sanz M, Agudo-Barriuso M. Interplay between mesenchymal stromal cells and the immune system after transplantation: implications for advanced cell therapy in the retina. Neural Regen Res. 2024;19:542-547. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Cheng HY, Anggelia MR, Lin CH, Wei FC. Toward transplantation tolerance with adipose tissue-derived therapeutics. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1111813. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Erpicum P, Weekers L, Detry O, Bonvoisin C, Delbouille MH, Grégoire C, Baudoux E, Briquet A, Lechanteur C, Maggipinto G, Somja J, Pottel H, Baron F, Jouret F, Beguin Y. Infusion of third-party mesenchymal stromal cells after kidney transplantation: a phase I-II, open-label, clinical study. Kidney Int. 2019;95:693-707. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Zhang Y, Zhang J, Yi H, Zheng J, Cai J, Chen W, Lu T, Chen L, Du C, Liu J, Yao J, Zhao H, Wang G, Fu B, Zhang T, Zhang J, Wang G, Li H, Xiang AP, Chen G, Yi S, Zhang Q, Yang Y. A novel MSC-based immune induction strategy for ABO-incompatible liver transplantation: a phase I/II randomized, open-label, controlled trial. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2021;12:244. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Shan Y, Zhang M, Tao E, Wang J, Wei N, Lu Y, Liu Q, Hao K, Zhou F, Wang G. Pharmacokinetic characteristics of mesenchymal stem cells in translational challenges. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2024;9:242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 21.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Bagno LL, Salerno AG, Balkan W, Hare JM. Mechanism of Action of Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs): impact of delivery method. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2022;22:449-463. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Ullah M, Liu DD, Thakor AS. Mesenchymal Stromal Cell Homing: Mechanisms and Strategies for Improvement. iScience. 2019;15:421-438. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 381] [Cited by in RCA: 401] [Article Influence: 57.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Cornelissen AS, Maijenburg MW, Nolte MA, Voermans C. Organ-specific migration of mesenchymal stromal cells: Who, when, where and why? Immunol Lett. 2015;168:159-169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Dabrowska S, Andrzejewska A, Janowski M, Lukomska B. Immunomodulatory and Regenerative Effects of Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Extracellular Vesicles: Therapeutic Outlook for Inflammatory and Degenerative Diseases. Front Immunol. 2020;11:591065. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 164] [Article Influence: 32.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Williams T, Salmanian G, Burns M, Maldonado V, Smith E, Porter RM, Song YH, Samsonraj RM. Versatility of mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles in tissue repair and regenerative applications. Biochimie. 2023;207:33-48. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Li JK, Yang C, Su Y, Luo JC, Luo MH, Huang DL, Tu GW, Luo Z. Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles: A Potential Therapeutic Strategy for Acute Kidney Injury. Front Immunol. 2021;12:684496. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Kumar MA, Baba SK, Sadida HQ, Marzooqi SA, Jerobin J, Altemani FH, Algehainy N, Alanazi MA, Abou-Samra AB, Kumar R, Al-Shabeeb Akil AS, Macha MA, Mir R, Bhat AA. Extracellular vesicles as tools and targets in therapy for diseases. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2024;9:27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 441] [Cited by in RCA: 659] [Article Influence: 329.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Casadei M, Miguel B, Rubione J, Fiore E, Mengelle D, Guerri-Guttenberg RA, Montaner A, Villar MJ, Constandil-Córdova L, Romero-Sandoval AE, Brumovsky PR. Mesenchymal Stem Cell Engagement Modulates Neuroma Microenviroment in Rats and Humans and Prevents Postamputation Pain. J Pain. 2024;25:104508. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Zhang L, Liu J, Zhou C. Current aspects of small extracellular vesicles in pain process and relief. Biomater Res. 2023;27:78. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Nakazaki M, Yokoyama T, Lankford KL, Hirota R, Kocsis JD, Honmou O. Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Their Extracellular Vesicles: Therapeutic Mechanisms for Blood-Spinal Cord Barrier Repair Following Spinal Cord Injury. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25:13460. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Morelli AE, Larregina AT, Shufesky WJ, Sullivan ML, Stolz DB, Papworth GD, Zahorchak AF, Logar AJ, Wang Z, Watkins SC, Falo LD Jr, Thomson AW. Endocytosis, intracellular sorting, and processing of exosomes by dendritic cells. Blood. 2004;104:3257-3266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 690] [Cited by in RCA: 829] [Article Influence: 37.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Morad G, Carman CV, Hagedorn EJ, Perlin JR, Zon LI, Mustafaoglu N, Park TE, Ingber DE, Daisy CC, Moses MA. Tumor-Derived Extracellular Vesicles Breach the Intact Blood-Brain Barrier via Transcytosis. ACS Nano. 2019;13:13853-13865. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 244] [Cited by in RCA: 433] [Article Influence: 61.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Kalvala AK, Bagde A, Arthur P, Kulkarni T, Bhattacharya S, Surapaneni S, Patel NK, Nimma R, Gebeyehu A, Kommineni N, Meckes DG Jr, Sun L, Banjara B, Mosley-Kellum K, Dinh TC, Singh M. Cannabidiol-Loaded Extracellular Vesicles from Human Umbilical Cord Mesenchymal Stem Cells Alleviate Paclitaxel-Induced Peripheral Neuropathy. Pharmaceutics. 2023;15:554. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Lener T, Gimona M, Aigner L, Börger V, Buzas E, Camussi G, Chaput N, Chatterjee D, Court FA, Del Portillo HA, O'Driscoll L, Fais S, Falcon-Perez JM, Felderhoff-Mueser U, Fraile L, Gho YS, Görgens A, Gupta RC, Hendrix A, Hermann DM, Hill AF, Hochberg F, Horn PA, de Kleijn D, Kordelas L, Kramer BW, Krämer-Albers EM, Laner-Plamberger S, Laitinen S, Leonardi T, Lorenowicz MJ, Lim SK, Lötvall J, Maguire CA, Marcilla A, Nazarenko I, Ochiya T, Patel T, Pedersen S, Pocsfalvi G, Pluchino S, Quesenberry P, Reischl IG, Rivera FJ, Sanzenbacher R, Schallmoser K, Slaper-Cortenbach I, Strunk D, Tonn T, Vader P, van Balkom BW, Wauben M, Andaloussi SE, Théry C, Rohde E, Giebel B. Applying extracellular vesicles based therapeutics in clinical trials - an ISEV position paper. J Extracell Vesicles. 2015;4:30087. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 950] [Cited by in RCA: 1157] [Article Influence: 105.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Keshtkar S, Azarpira N, Ghahremani MH. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles: novel frontiers in regenerative medicine. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2018;9:63. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 315] [Cited by in RCA: 671] [Article Influence: 83.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Moghassemi S, Dadashzadeh A, Sousa MJ, Vlieghe H, Yang J, León-Félix CM, Amorim CA. Extracellular vesicles in nanomedicine and regenerative medicine: A review over the last decade. Bioact Mater. 2024;36:126-156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Lynch C, Panagopoulou M, Gregory CD. Extracellular Vesicles Arising from Apoptotic Cells in Tumors: Roles in Cancer Pathogenesis and Potential Clinical Applications. Front Immunol. 2017;8:1174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Witwer KW, Théry C. Extracellular vesicles or exosomes? On primacy, precision, and popularity influencing a choice of nomenclature. J Extracell Vesicles. 2019;8:1648167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 244] [Cited by in RCA: 413] [Article Influence: 59.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Sonbhadra S, Mehak, Pandey LM. Biogenesis, Isolation, and Detection of Exosomes and Their Potential in Therapeutics and Diagnostics. Biosensors (Basel). 2023;13:802. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 55. | Hade MD, Suire CN, Suo Z. Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes: Applications in Regenerative Medicine. Cells. 2021;10:1959. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 312] [Cited by in RCA: 391] [Article Influence: 78.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Gurunathan S, Kang MH, Qasim M, Khan K, Kim JH. Biogenesis, Membrane Trafficking, Functions, and Next Generation Nanotherapeutics Medicine of Extracellular Vesicles. Int J Nanomedicine. 2021;16:3357-3383. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 22.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Battistelli M, Falcieri E. Apoptotic Bodies: Particular Extracellular Vesicles Involved in Intercellular Communication. Biology (Basel). 2020;9:21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 227] [Cited by in RCA: 315] [Article Influence: 52.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Zhao AG, Shah K, Cromer B, Sumer H. Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles and Their Therapeutic Potential. Stem Cells Int. 2020;2020:8825771. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Kim HS, Choi DY, Yun SJ, Choi SM, Kang JW, Jung JW, Hwang D, Kim KP, Kim DW. Proteomic analysis of microvesicles derived from human mesenchymal stem cells. J Proteome Res. 2012;11:839-849. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 279] [Cited by in RCA: 325] [Article Influence: 21.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Wang Z, Yang C, Yan S, Sun J, Zhang J, Qu Z, Sun W, Zang J, Xu D. Emerging Role and Mechanism of Mesenchymal Stem Cells-Derived Extracellular Vesicles in Rheumatic Disease. J Inflamm Res. 2024;17:6827-6846. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Zhang X, Lu Y, Wu S, Zhang S, Li S, Tan J. An Overview of Current Research on Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles: A Bibliometric Analysis From 2009 to 2021. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2022;10:910812. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Tavasolian F, Inman RD. Biology and therapeutic potential of mesenchymal stem cell extracellular vesicles in axial spondyloarthritis. Commun Biol. 2023;6:413. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Gomzikova MO, James V, Rizvanov AA. Extracellular Vesicles Derived from Mesenchymal Stem Cells. In: Handbook of Stem Cell Therapy. Singapore: Springer, 2022. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 64. | Qin D, Wang X, Pu J, Hu H. Cardiac cells and mesenchymal stem cells derived extracellular vesicles: a potential therapeutic strategy for myocardial infarction. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2024;11:1493290. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Abd ElFattah L. Mesenchymal Stem Cells Derived Extracellular Vesicles. J Med Histol. 2017;1:1-7. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | do Rio Bamar LMM, Nunes DDG, Soares MBP. Extracellular Vesicles Derived From Mesenchymal Stem Cells with Therapeutic Potential: Isolation and Characterization. J Bioeng Technol Health. 2023;6:112-115. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 67. | Ahad Mir P, Hussain MS, Ahmad Khanday M, Mohi-Ud-Din R, Pottoo FH, Hassan Mir R. Immunomodulatory Roles of Mesenchymal Stem Cell-derived Extracellular Vesicles: A Promising Therapeutic Approach for Autoimmune Diseases. Curr Stem Cell Res Ther. 2025;20:949-965. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Conrad S, Younsi A, Bauer C, Geburek F, Skutella T. Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles as Mediators of Anti-inflammatory Effects. In: Pham P. Stem Cell Transplantation for Autoimmune Diseases and Inflammation. Stem Cells in Clinical Applications. Cham: Springer, 2019. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 69. | Harrell CR, Jovicic N, Djonov V, Arsenijevic N, Volarevic V. Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes and Other Extracellular Vesicles as New Remedies in the Therapy of Inflammatory Diseases. Cells. 2019;8:1605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 225] [Cited by in RCA: 586] [Article Influence: 83.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Zhang C, Huang Y, Ouyang F, Su M, Li W, Chen J, Xiao H, Zhou X, Liu B. Extracellular vesicles derived from mesenchymal stem cells alleviate neuroinflammation and mechanical allodynia in interstitial cystitis rats by inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome activation. J Neuroinflammation. 2022;19:80. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 15.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Cui X, Bi X, Zhang X, Zhang Z, Yan Q, Wang Y, Huang X, Wu X, Jing X, Wang H. MiR-9-enriched mesenchymal stem cells derived exosomes prevent cystitis-induced bladder pain via suppressing TLR4/NLRP3 pathway in interstitial cystitis mice. Immun Inflamm Dis. 2024;12:e1140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Ryan ST, Hosseini-Beheshti E, Afrose D, Ding X, Xia B, Grau GE, Little CB, McClements L, Li JJ. Extracellular Vesicles from Mesenchymal Stromal Cells for the Treatment of Inflammation-Related Conditions. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:3023. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Guo Z, He M, Shi D, Zhang Z, Wang L, Ren B, Wang Y, Wang J, Yang S, Yu H. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles enriched with miR-124 exhibit anti-inflammatory effects in collagen-induced arthritis. Arch Biol Sci. 2024;76:30. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 74. | Almahasneh F, Abu-El-Rub E, Khasawneh RR. Mechanisms of analgesic effect of mesenchymal stem cells in osteoarthritis pain. World J Stem Cells. 2023;15:196-208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Zhao X, Zhao Y, Sun X, Xing Y, Wang X, Yang Q. Immunomodulation of MSCs and MSC-Derived Extracellular Vesicles in Osteoarthritis. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2020;8:575057. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 16.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Liu H, Li R, Liu T, Yang L, Yin G, Xie Q. Immunomodulatory Effects of Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Front Immunol. 2020;11:1912. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 20.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Hu S, Xing H, Zhang J, Zhu Z, Yin Y, Zhang N, Qi Y. Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles: Immunomodulatory Effects and Potential Applications in Intervertebral Disc Degeneration. Stem Cells Int. 2022;2022:7538025. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Théry C, Witwer KW, Aikawa E, Alcaraz MJ, Anderson JD, Andriantsitohaina R, Antoniou A, Arab T, Archer F, Atkin-Smith GK, Ayre DC, Bach JM, Bachurski D, Baharvand H, Balaj L, Baldacchino S, Bauer NN, Baxter AA, Bebawy M, Beckham C, Bedina Zavec A, Benmoussa A, Berardi AC, Bergese P, Bielska E, Blenkiron C, Bobis-Wozowicz S, Boilard E, Boireau W, Bongiovanni A, Borràs FE, Bosch S, Boulanger CM, Breakefield X, Breglio AM, Brennan MÁ, Brigstock DR, Brisson A, Broekman ML, Bromberg JF, Bryl-Górecka P, Buch S, Buck AH, Burger D, Busatto S, Buschmann D, Bussolati B, Buzás EI, Byrd JB, Camussi G, Carter DR, Caruso S, Chamley LW, Chang YT, Chen C, Chen S, Cheng L, Chin AR, Clayton A, Clerici SP, Cocks A, Cocucci E, Coffey RJ, Cordeiro-da-Silva A, Couch Y, Coumans FA, Coyle B, Crescitelli R, Criado MF, D'Souza-Schorey C, Das S, Datta Chaudhuri A, de Candia P, De Santana EF, De Wever O, Del Portillo HA, Demaret T, Deville S, Devitt A, Dhondt B, Di Vizio D, Dieterich LC, Dolo V, Dominguez Rubio AP, Dominici M, Dourado MR, Driedonks TA, Duarte FV, Duncan HM, Eichenberger RM, Ekström K, El Andaloussi S, Elie-Caille C, Erdbrügger U, Falcón-Pérez JM, Fatima F, Fish JE, Flores-Bellver M, Försönits A, Frelet-Barrand A, Fricke F, Fuhrmann G, Gabrielsson S, Gámez-Valero A, Gardiner C, Gärtner K, Gaudin R, Gho YS, Giebel B, Gilbert C, Gimona M, Giusti I, Goberdhan DC, Görgens A, Gorski SM, Greening DW, Gross JC, Gualerzi A, Gupta GN, Gustafson D, Handberg A, Haraszti RA, Harrison P, Hegyesi H, Hendrix A, Hill AF, Hochberg FH, Hoffmann KF, Holder B, Holthofer H, Hosseinkhani B, Hu G, Huang Y, Huber V, Hunt S, Ibrahim AG, Ikezu T, Inal JM, Isin M, Ivanova A, Jackson HK, Jacobsen S, Jay SM, Jayachandran M, Jenster G, Jiang L, Johnson SM, Jones JC, Jong A, Jovanovic-Talisman T, Jung S, Kalluri R, Kano SI, Kaur S, Kawamura Y, Keller ET, Khamari D, Khomyakova E, Khvorova A, Kierulf P, Kim KP, Kislinger T, Klingeborn M, Klinke DJ 2nd, Kornek M, Kosanović MM, Kovács ÁF, Krämer-Albers EM, Krasemann S, Krause M, Kurochkin IV, Kusuma GD, Kuypers S, Laitinen S, Langevin SM, Languino LR, Lannigan J, Lässer C, Laurent LC, Lavieu G, Lázaro-Ibáñez E, Le Lay S, Lee MS, Lee YXF, Lemos DS, Lenassi M, Leszczynska A, Li IT, Liao K, Libregts SF, Ligeti E, Lim R, Lim SK, Linē A, Linnemannstöns K, Llorente A, Lombard CA, Lorenowicz MJ, Lörincz ÁM, Lötvall J, Lovett J, Lowry MC, Loyer X, Lu Q, Lukomska B, Lunavat TR, Maas SL, Malhi H, Marcilla A, Mariani J, Mariscal J, Martens-Uzunova ES, Martin-Jaular L, Martinez MC, Martins VR, Mathieu M, Mathivanan S, Maugeri M, McGinnis LK, McVey MJ, Meckes DG Jr, Meehan KL, Mertens I, Minciacchi VR, Möller A, Møller Jørgensen M, Morales-Kastresana A, Morhayim J, Mullier F, Muraca M, Musante L, Mussack V, Muth DC, Myburgh KH, Najrana T, Nawaz M, Nazarenko I, Nejsum P, Neri C, Neri T, Nieuwland R, Nimrichter L, Nolan JP, Nolte-'t Hoen EN, Noren Hooten N, O'Driscoll L, O'Grady T, O'Loghlen A, Ochiya T, Olivier M, Ortiz A, Ortiz LA, Osteikoetxea X, Østergaard O, Ostrowski M, Park J, Pegtel DM, Peinado H, Perut F, Pfaffl MW, Phinney DG, Pieters BC, Pink RC, Pisetsky DS, Pogge von Strandmann E, Polakovicova I, Poon IK, Powell BH, Prada I, Pulliam L, Quesenberry P, Radeghieri A, Raffai RL, Raimondo S, Rak J, Ramirez MI, Raposo G, Rayyan MS, Regev-Rudzki N, Ricklefs FL, Robbins PD, Roberts DD, Rodrigues SC, Rohde E, Rome S, Rouschop KM, Rughetti A, Russell AE, Saá P, Sahoo S, Salas-Huenuleo E, Sánchez C, Saugstad JA, Saul MJ, Schiffelers RM, Schneider R, Schøyen TH, Scott A, Shahaj E, Sharma S, Shatnyeva O, Shekari F, Shelke GV, Shetty AK, Shiba K, Siljander PR, Silva AM, Skowronek A, Snyder OL 2nd, Soares RP, Sódar BW, Soekmadji C, Sotillo J, Stahl PD, Stoorvogel W, Stott SL, Strasser EF, Swift S, Tahara H, Tewari M, Timms K, Tiwari S, Tixeira R, Tkach M, Toh WS, Tomasini R, Torrecilhas AC, Tosar JP, Toxavidis V, Urbanelli L, Vader P, van Balkom BW, van der Grein SG, Van Deun J, van Herwijnen MJ, Van Keuren-Jensen K, van Niel G, van Royen ME, van Wijnen AJ, Vasconcelos MH, Vechetti IJ Jr, Veit TD, Vella LJ, Velot É, Verweij FJ, Vestad B, Viñas JL, Visnovitz T, Vukman KV, Wahlgren J, Watson DC, Wauben MH, Weaver A, Webber JP, Weber V, Wehman AM, Weiss DJ, Welsh JA, Wendt S, Wheelock AM, Wiener Z, Witte L, Wolfram J, Xagorari A, Xander P, Xu J, Yan X, Yáñez-Mó M, Yin H, Yuana Y, Zappulli V, Zarubova J, Žėkas V, Zhang JY, Zhao Z, Zheng L, Zheutlin AR, Zickler AM, Zimmermann P, Zivkovic AM, Zocco D, Zuba-Surma EK. Minimal information for studies of extracellular vesicles 2018 (MISEV2018): a position statement of the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles and update of the MISEV2014 guidelines. J Extracell Vesicles. 2018;7:1535750. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6453] [Cited by in RCA: 8240] [Article Influence: 1030.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 79. | Poongodi R, Hsu YW, Yang TH, Huang YH, Yang KD, Lin HC, Cheng JK. Stem Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicle-Mediated Therapeutic Signaling in Spinal Cord Injury. Int J Mol Sci. 2025;26:723. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Davis C, Savitz SI, Satani N. Mesenchymal Stem Cell Derived Extracellular Vesicles for Repairing the Neurovascular Unit after Ischemic Stroke. Cells. 2021;10:767. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Turovsky EA, Golovicheva VV, Varlamova EG, Danilina TI, Goryunov KV, Shevtsova YA, Pevzner IB, Zorova LD, Babenko VA, Evtushenko EA, Zharikova AA, Khutornenko AA, Kovalchuk SI, Plotnikov EY, Zorov DB, Sukhikh GT, Silachev DN. Mesenchymal stromal cell-derived extracellular vesicles afford neuroprotection by modulating PI3K/AKT pathway and calcium oscillations. Int J Biol Sci. 2022;18:5345-5368. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 82. | Ai M, Hotham WE, Pattison LA, Ma Q, Henson FMD, Smith ESJ. Role of Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Derived Extracellular Vesicles in Reducing Sensory Neuron Hyperexcitability and Pain Behaviors in Murine Osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2023;75:352-363. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 83. | Yang Y, Gao L, Xi J, Liu X, Yang H, Luo Q, Xie F, Niu J, Meng P, Tian X, Wu X, Long Q. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles mitigate neuronal damage from intracerebral hemorrhage by modulating ferroptosis. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2024;15:255. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 84. | Drommelschmidt K, Serdar M, Bendix I, Herz J, Bertling F, Prager S, Keller M, Ludwig AK, Duhan V, Radtke S, de Miroschedji K, Horn PA, van de Looij Y, Giebel B, Felderhoff-Müser U. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles ameliorate inflammation-induced preterm brain injury. Brain Behav Immun. 2017;60:220-232. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 173] [Cited by in RCA: 228] [Article Influence: 25.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 85. | Kuner R. Central mechanisms of pathological pain. Nat Med. 2010;16:1258-1266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 473] [Cited by in RCA: 570] [Article Influence: 35.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 86. | Gold MS, Gebhart GF. Nociceptor sensitization in pain pathogenesis. Nat Med. 2010;16:1248-1257. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 625] [Cited by in RCA: 604] [Article Influence: 37.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 87. | Woolf CJ, Allchorne A, Safieh-Garabedian B, Poole S. Cytokines, nerve growth factor and inflammatory hyperalgesia: the contribution of tumour necrosis factor alpha. Br J Pharmacol. 1997;121:417-424. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 526] [Cited by in RCA: 531] [Article Influence: 18.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 88. | Chatterjea D, Martinov T. Mast cells: versatile gatekeepers of pain. Mol Immunol. 2015;63:38-44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 89. | Pinho-Ribeiro FA, Verri WA Jr, Chiu IM. Nociceptor Sensory Neuron-Immune Interactions in Pain and Inflammation. Trends Immunol. 2017;38:5-19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 428] [Cited by in RCA: 784] [Article Influence: 78.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 90. | Zarpelon AC, Rodrigues FC, Lopes AH, Souza GR, Carvalho TT, Pinto LG, Xu D, Ferreira SH, Alves-Filho JC, McInnes IB, Ryffel B, Quesniaux VF, Reverchon F, Mortaud S, Menuet A, Liew FY, Cunha FQ, Cunha TM, Verri WA Jr. Spinal cord oligodendrocyte-derived alarmin IL-33 mediates neuropathic pain. FASEB J. 2016;30:54-65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 91. | Xu J, Zhu MD, Zhang X, Tian H, Zhang JH, Wu XB, Gao YJ. NFκB-mediated CXCL1 production in spinal cord astrocytes contributes to the maintenance of bone cancer pain in mice. J Neuroinflammation. 2014;11:38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 92. | Ji RR, Berta T, Nedergaard M. Glia and pain: is chronic pain a gliopathy? Pain. 2013;154 Suppl 1:S10-S28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 786] [Cited by in RCA: 897] [Article Influence: 69.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 93. | Gao YJ, Ji RR. Chemokines, neuronal-glial interactions, and central processing of neuropathic pain. Pharmacol Ther. 2010;126:56-68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 404] [Cited by in RCA: 493] [Article Influence: 30.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |