Published online Feb 28, 2026. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v32.i8.115077

Revised: November 24, 2025

Accepted: December 12, 2025

Published online: February 28, 2026

Processing time: 127 Days and 4.9 Hours

Alcoholic liver disease (ALD) is driven by oxidative stress, lipid metabolism, inflammation, and apoptosis. Current therapies lack efficacy in targeting multi-pathway mechanisms. Xing-Pi-Qing-Gan decoction (XPQG) is an improved tra

To illustrate the therapeutic targets and molecular pathways of XPQG for the treatment of ALD by integrating chemical profiling, network pharmacology, transcriptomics, and experimental verification in vivo and in vitro.

The components of XPQG were analyzed using ultra-high performance liquid chromatography quadrupole-time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Then, the pro

In ethanol-treated HepG2 cells, XPQG dose-dependently reduced the formation of lipid droplets, inhibited the expression of tumor necrosis factor-α, interleukin-6, interleukin-1β, and alleviated oxidative stress. In mice, XPQG (15.2 g/kg) lowered the liver/body weight ratio, alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, γ-glutamyl transferase; H&E and Oil Red O demonstrated a reduction in steatosis. Network pharmacology and RNA-seq converged on MAPK signaling, suggesting DDIT3 as a likely key effector in XPQG-mediated protection. DDIT3 knockdown in HepG2 cells attenuated the benefits of XPQG, supporting DDIT3 as a critical effector mechanism in XPQG-mediated protection. The use of NAC further illustrates the correlation of drugs to oxidative stress in disease effects.

In summary, the results of the study suggest that XPQG is effective in improving ethanol-induced acute liver injury (ALD). Its mechanism involves the suppression of DDIT3 and the enhancement of Nrf2/HO-1 pathway activity.

Core Tip: Xing-Pi-Qing-Gan decoction (XPQG) is effective in improving ethanol-induced acute liver injury. XPQG alleviates alcoholic liver disease by suppressing DDIT3 and enhancing Nrf2/HO-1-mediated antioxidant responses, reduce lipid accumulation, inflammation, and apoptosis, as validated through multi-omics and experimental studies.

- Citation: Huang NF, Ling P, Xu YJ, Feng XF, Zheng Y, Sun T. Xing-Pi-Qing-Gan decoction alleviates alcoholic liver disease by down-regulating DDIT3 and restoring Nrf2/HO-1 antioxidant signaling: Multi-omics and experimental evidence. World J Gastroenterol 2026; 32(8): 115077

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v32/i8/115077.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v32.i8.115077

Alcohol abuse is one of the overriding threats to global health. It has been identified as the primary factor risking premature mortality among individuals aged 15-49 years[1]. As reported by World Health Organization[2], alcoholic liver disease (ALD) has a worldwide impact. Excessive alcohol consumption has caused about 3 million deaths annually, accounting for 5.3% of the global sum. Its clinical scope includes progressive pathological processes from fibrosis, hepatitis, steatosis, to cirrhosis[3]. Abstinence is widely recognized as the cornerstone for ALD treatment, but sustained remission is difficult. Relapse remains a common clinical challenge[4,5]. Current clinical interventions mainly focus on symptomatic liver protection measures, including nutritional support and anti-inflammatory drugs[6]. The clinical drug N-acetylcysteine (NAC) exhibits antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties during ALD treatment. However, it is difficult to operate independently and lacks evidence of long-term benefit[7]. Current therapeutic strategies under constraints need novel drugs that mitigate liver injury by modulating critical signaling networks.

Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) stands out in the prevention and treatment of ALD. TCM compound preparations achieve synergistic effects through “multi-component, multi-target” approaches. This method effectively relieves oxidative stress and inflammation, regulating liver function and lipid metabolism, in line with the complex pathogenesis of ALD[2]. Xing-Pi-Qing-Gan decoction (XPQG) is derived from the classic prescription Ge-Hua-Jie-Cheng decoction, with significant effects in clinical applications. Its composition includes: (1) Pueraria lobata (Ge Hua) for alcohol-toxin resolution; (2) Poria cocos (Fu Ling) and Polyporus umbellatus (Zhu Ling) for spleen strengthening and dampness elimination; (3) Penthorum chinense (Gan Huangcao) for blood stasis resolution and jaundice alleviation; (4) Gardenia jasminoides (Zhi Zi) for bile promoting and heat clearing; and (5) Glycyrrhiza uralensis (Gan Cao) for herbal harmony. As found, Ge Hua is capable of protecting the liver and lowering enzymes, with regulation effects on fatty acid oxidation and anti-inflammatory reactions through PPARα[8]. The TLR4/NF-κB inflammatory pathway is blocked by the flavonoid components in Gan Huangcao[9]. As suggested by the TCM theory, despite reasonable compatibility, the overall mechanism of the XPQG compound is unclear, especially the lack of systematic interpretation for inflammation and oxidative stress.

According to the research, the regulation of ALD involves pathways, including oxidative stress, inflammatory response, lipid metabolism and alcohol metabolism[10]. Notably, oxidative stress is a toxic byproduct of ethanol metabolism as a “common pathway” for driving ALD from steatosis to fibrosis and hepatitis[11]. However, characterization of the chemical composition of XPQG is insufficient. It is difficult to study the potential complex mechanism of ALD. Therefore, the chemical composition of XPQG was analyzed through the ultra-high performance liquid chromatography quadrupole-time-of-flight mass spectrometry (UPLC-Q/TOF-MS). After validating the efficacy of XPQG against ALD based on an ALD mouse model, the potential mechanisms and targets were predicted by network pharmacology and transcriptomic analysis. These hypotheses were subsequently validated through Western blot, quantitative RT-PCR and cell transfection experiments. This study may provide experimental evidence for the development and application of XPQG, implying its potential value in the prevention or treatment of ALD.

Aspartate aminotransferase (AST) detection kit, alanine aminotransferase (ALT) detection kit, triglyceride (TG) detection kit, malondialdehyde (MDA) detection kit, alkaline phosphatase (AKP) detection kit, superoxide dismutase (SOD) detection kit, and γ-glutamyl transferase (GGT) detection kit were obtained from Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Research Institute (Nanjing, China). Mitochondrial membrane potential assay kit and reactive oxygen species (ROS) assay kit were purchased from Shanghai Beyotime Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Additionally, serum levels of interleukin-1β (IL-1β), interleukin-6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) were measured using the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit [Wuhan Elabscience Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Wuhan, China)]. NACs were purchased from MedChemExpress LLC (NJ, United States).

The XPQG was provided by the Second Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang Chinese Medical University and identified by Professor Tao Sun. The herbal blend was added with Ge Hua (45 g), Zhu Ling (30 g), Fu Ling (36 g), Gan Huangcao (30 g), Zhi Zi (18 g) and Gan Cao (18 g), which were boiled together with 177 mL of water for 1.5 hours. An additional 177 mL of water was then added and boiled for another 1.5 hours. Eventually, the XPQG extract was obtained by concentration using the rotary evaporator.

UPLC-Q/TOF-MS were used to analyze XPQG components with an ACQUITY UPLC Cortecs T3 column (2.1 mm × 100 mm, 1.6 μm). The parameters included: Flow rate = 0.3 mL/minute; autosampler temperature = 25 °C; column temperature = 35 °C; and injection volume = 2 μL. Acetonitrile and 0.1% formic acid in water formed mobile phases A and B. The gradient elution conditions included: (1) 5% A, 0-2 minutes; (2) 5%-10% A, 2-32 minutes; (3) 100% A, 32-33 minutes; (4) 100%-5% A, 33-33.5 minutes; and (5) 5% A, 33.5-35 minutes. Then, electrospray ionization-MS analysis was conducted using a Q-TOF SYNAPT G2-Si High-Definition Mass Spectrometer with the parameters as follows: Capillary voltage: 3.0 kV (positive) and 2.5 kV (negative), sample cone voltage: 40 V, flow rate: 1000 L/hour, and gas temperature: 500 °C.

Male Sprague Dawley rats (200-220 g) were obtained from Shanghai SLAC Laboratory Animal Co., Ltd. Rats were adaptively maintained for 1 week under controlled environmental conditions: 12 hours light/dark cycle, ad libitum diet, relative humidity 55% ± 5%, constant temperature 22 ± 2 °C. Eight rats were then randomly classified into the XPQG group and the blank serum group. The administration dose of XPQG was calculated by the body surface area. The daily gavage dose was 10.6 g/kg. The blank group received the same amount of normal saline, and rats were gavaged twice daily for 5 days. Rats were anesthetized with isoflurane 1 hour after the last administration. Blood samples were gathered from the abdominal aorta and left at room temperature for 1 hour. To isolate the serum, blood samples were centrifuged at 4 °C for 10 minutes at 3500 rpm. The obtained serum was inactivated for 30 minutes at 56 °C, filtered through a 0.22 μm filter, and kept at -20 °C for later use. The animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Zhejiang University of Chinese Medicine (Approval No. IACUC-202410-15).

Specific pathogen free C57BL/6J male mice (18-22 g, 6-8 weeks old) were purchased from Shanghai SLAC Laboratory Animal Co. Ltd. The NIAAA model was constructed by feeding mice as previously published[12]. After 1 week of acclimatization, randomization was performed using a computer-generated random number table (http://www.random.org) to ensure equal distribution of body weight and baseline characteristics among groups. Mice were randomly classi

The liver tissue was fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin. Subsequently, paraffin-embedded liver samples were sectioned into 4 μm thick slices. After hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining, the images were captured under a light microscope at 40 × magnification. The frozen liver slices were sliced and stained with Oil Red O to histologically investigate hepatic steatosis. Liver tissues were cut into 1 mm3 cubes and fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde for transmission electron microscopy to observe ultrastructural changes.

The main chemical ingredients of the herbs Ge Hua, Zhu Ling, Fu Ling, Gan Huangcao, Zhi Zi and Gan Cao were determined in reference to the Traditional Chinese Medicine Systems Pharmacology Database and Analysis Platform (https://tcmspw.com/tcmsp.php). The selected ingredients met the criteria of oral bioavailability ≥ 30% and drug-like activity ≥ 18%. We used "ALD" as the search term to obtain disease targets from five databases, which included Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (https://omim.org/), GeneCards (http://www.genecards.org), Therapeutic Target Database (http://db.idrblab.net/ttd/), Disgenet (https://www.disgenet.org/), and Drugbank (https://go.drugbank.com/), and then integrated cross-target data from the disease and drug. The protein interaction network of intersecting targets was analyzed through the Cytoscape 3.7.2 software and the STRING 12.0 database. Additionally, overlapping targets for Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment were assessed based on the DAVID database. The web tool Bioinformatics (https://www.bioinformatics.com.cn/) was used to plot and dis

Total RNA was extracted from mouse liver tissue with the TRIzol reagent. An RNA quality control (QC) approach was used for analysis of RNA content, purity, and integrity. The workflow contained PCR amplification, adaptor ligation, A-tailing, end repair to generate blunt ends, cDNA amplification, and mRNA enrichment. The Illumina RNA sequencing and analysis were performed by Tsingke Biotechnology Co., Ltd. Based on a Log2 (fold change) ≥ 1 and P < 0.05, we identified differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in liver tissues of the XPQG vs EtOH group.

The human hepatocellular carcinoma cell line HepG2 was obtained from Sunncell Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Wuhan, China). Cells were cultured in an incubator of 5% CO2 at 37 °C in DMEM containing 10% FBS, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, and 100 U/mL penicillin. DMEM and FBS were purchased from Gibco. Cells are grouped into control group, EtOH, EtOH + XPQG-L, EtOH + XPQG-M, EtOH + XPQG-H, and EtOH + silymarin (100 μmol/L).

Cells were replaced with antibiotic-free in Opti-MEM (Gibco) medium after HepG2 cells in DMEM/F12 medium reached approximately 30%-50%. Then, DDIT3 siRNA (1000 ng/mL) was transfected using LipofectamineTM 3000. Cells were replaced in fresh medium for 24-48 hours after incubation at 5% CO2 and 37 °C for 6-8 hours to collect for the next experiment. The siRNA sequences are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

HepG2 cells (5000 cells/well) were cultured in 96-well plates and intervened by different ethanol concentrations (3.125 uM, 6.25 uM, 12.5 uM, 25 uM, 50 uM, 100 uM, and 200 uM) or XPQG (5.2%, 6.6%, 8.2%, 10.2%, 12.8%, 16%, 20%, and 25%) for 24 hours, respectively. The duplicated well was set for each concentration. Cell viability was determined by CCK-8 assay, and relative viability was calculated by measuring the absorbance at 450 nm using a microplate reader. Cell viability (% of control) = [(A treatment group – A blank group)/(A control group – A blank group)] × 100%.

Total RNA was extracted from mouse liver tissue, and HepG2 cells and cDNA was collected by the reverse transcription kit. The amplification levels of mRNAs and miRNAs were calculated by the 2ΔΔCt method. GAPDH were used as an endogenous control to normalize quantitative RT-PCR data. The 2 × S6 Universal SYBR qPCR Mix and HyperScript III RT SuperMix for qPCR with gDNA remover were purchased from EnzyArtisan Biotech Co., Ltd. (NovaBio; Shanghai, China). Supplementary Table 1 shows the primer sequence information of the tested gene. Total protein was extracted by the RIPA buffer. Proteins were isolated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to the nitrocellulose membrane. After blocking, the membrane was incubated with primary antibodies overnight. Furthermore, the membrane was incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated IgG and visualized by chemiluminescence.

The resulting data were presented as mean ± SEM. The t-test for unpaired groups was used for comparison. More than two groups were analyzed by the one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). P < 0.05 indicated statistically significant differences.

The main active components of XPQG were identified by generating the total ion chromatogram of XPQG in both positive and negative models (Figure 1), which are known for their anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects.

The CCK-8 kit was used to determine HepG2 cell activity induced by different concentrations of ethanol (Figure 2A). The experimental results showed that ethanol could inhibit the relative survival rate of HepG2 cells in a concentration-dependent manner, and the relative survival rate of cells decreased to 64.39% when the concentration reached 100 mmol/L. In the follow-up experiment, we used this concentration of ethanol to intervene with the drug, during which the medium was changed every 6 hours to achieve a more stable effect.

The rate of cell survival was gradually reduced in a concentration-dependent manner with an increase in the concentration of drug-containing serum. Hence, in subsequent experiments, the concentration within 20% was chosen for pharmacodynamic screening (Figure 2B). By contrast, alcohol induction increased the levels of AST, ALT, TG, and AKP, which decreased with the increase of XPQG concentration. This means that the modeling method is effective in the XPQG high-dose group, with the best drug effect (Figure 2C). Interestingly, XPQG administration also significantly reduced alcohol-induced hepatic lipid accumulation in a dose-dependent manner and decreased the mRNA expression of hepatic SREBP-1c, ACC, and FASN (Figure 2D and E). Further detection of inflammation-related genes demonstrated that XPQG also significantly reduced the expression of pro-inflammatory genes in IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α (Figure 2F-H). Additionally, XPQG correspondingly affected the apoptosis of HepG2 cells. Relative mRNA levels and Western blot analysis showed that the anti-apoptotic gene Bcl-2 was reduced after ethanol intervention. Meanwhile, the expression increased by dose after drug intervention, while that of pro-apoptotic genes Caspase-3 and BAX was the opposite (Figure 2I-K).

The results of JC-1 staining indicated that the red/green fluorescence intensity of the administration group was increased compared to the EtOH group, which suggested that XPQG improved the mitochondrial membrane potential function (Figure 3A). The state of oxidative stress is usually reflected by the levels of ROS and MDA, while the actual antioxidant level was often assessed by glutathione (GSH), SOD and other antioxidant indicators. Consistently, the XPQG drug-containing serum alleviated the oxidative stress induced by alcohol incubation in HepG2, as evidenced by a dose-dependent reduction in ROS generation (Figure 3B). Similarly, treatment with different doses of XPQG significantly increased ALD-reduced SOD and GSH levels, as well as ALD-elevated MDA levels (Figure 3C-E). In conclusion, XPQG plays a profound role in preventing alcohol-induced hepatic lipid accumulation, inflammation, apoptosis, and oxidative stress.

It is assumed that XPQG may ameliorate alcohol-feeding induced ALD in mice when considering its effectiveness on oxidative stress in HepG2. Hence, mice were gavaged with different daily doses of XPQG. In ALD mice, XPQG treatment (3.8 g/kg, 7.6 g/kg, and 15.2 g/kg) reduced the liver weight/body weight ratio in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 4A and B). Biochemical analysis showed that AST, ALT, TG, and GGT were increased in the EtOH group, but were decreased with XPQG administration in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 4C-F). Furthermore, H&E staining and Oil Red O showed that XPQG (15.2 g/kg) treatment reduced alcohol-induced liver injury and lipid deposition (Figure 4G). XPQG also reduced the level of SREBP-1c mRNA associated with lipid synthesis and the expression of downstream genes, such as ACC, FASN in ALD mice (Figure 4H-J). Overall, XPQG had a significant hepatoprotective effect on alcohol-induced hepatotoxicity.

Furthermore, the effects of XPQG on inflammation, apoptosis, and oxidative stress—three key drivers of ALD progression were investigated. The relative mRNA expression of inflammatory factors in the liver was measured (Figure 5A). After XPQG treatment, the expression of IL-6, IL-1β and TNF-α was significantly reduced. The same validation indexes in serum were also measured by ELISA (Figure 5B), and the results showed that XPQG significantly reduced inflammation in ALD mice. Apoptosis is associated with changes in the expression of Caspase-3, Bcl-2 and BAX. Compared to the control group, the EtOH group showed a low expression level of Bcl-2 and a high expression level of BAX and Caspase-3 (Figure 5C). XPQG treatment increased the levels of Bcl-2 and decreased the levels of BAX and Caspase-3. Consistently, the expression of pro-apoptotic Caspase-3 was up-regulated in the Ethanol group, while that of anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 was down-regulated, which was significantly reversed by XPQG treatment (Figure 5D). After XPQG administration, MDA levels decreased while hepatic GSH and SOD levels increased as expected (Figure 5E-G). The results demonstrate that XPQG effectively mitigates alcohol-induced liver injury by suppressing inflammatory responses, inhibiting apoptosis, and attenuating oxidative stress, thereby reinforcing its therapeutic potential for ALD.

The network pharmacological analysis was conducted to investigate the pharmacodynamic components and molecular mechanisms of XPQG in alleviating ALD. First, 270 potential targets were identified by overlapping the compound targets of XPQG with ALD targets (Figure 6A). The Protein-Protein Interaction analysis indicated that the core targets were SRC, AKT1, JAK2, EGFR, JAK1, MAPK1, MAPK3, IL-6, RAF1, Bcl-2 (Figure 6B). GO analysis showed that the primary biological processes of DEGs were the positive regulation of MAPK cascade, the negative regulation of apoptosis, and the response to hypoxia. The main cellular component was mitochondria, while the main molecular functions were transmembrane receptor protein tyrosine kinase activity, ATP binding, and protein tyrosine kinase activity (Figure 6C). KEGG pathway enrichment analysis showed that DEGs were related to PI3K-Akt, MAPK and Ras signaling pathways, as well as lipid and atherosclerosis (Figure 6D).

To investigate the hepatoprotective mechanism of XPQG, the profiles of liver gene expression were analyzed using RNA sequencing. During the acquisition process, QC samples were detected to ensure the accuracy and repeatability of data. It was found that there was a clear separation between EtOH and XPQG models, which indicated a high reliability of the established model (Figure 7A). DEGs in the liver tissue of XPQG (15.2 g/kg) vs EtOH groups were identified given Log2 ≥ 1 and P < 0.05 (Figure 7B). GO enrichment analysis demonstrated that the focus was put on biological processes, including endoplasmic reticulum (ER) unfolded protein response, ER stress response, and positive regulation of lipid metabolism. These targets acted on cell regions, including ER lumen, smooth ER, and ER chaperone complex (Figure 7C). The potential signaling pathways were determined by KEGG pathway enrichment analysis to deeply understand the DEGs obtained from RNA sequencing. Further analysis found that the most important pathways were metabolic, PPAR, and MAPK signaling pathways (Figure 7D). Gene Set Enrichment Analysis showed that the MAPK signaling pathway was enriched after XPQG treatment (Figure 7E). According to GO and KEGG analysis, there were a large number of genes in the ER, which required further analysis. Heatmap showed ER-related DEGs, such as DDIT3 and HO-1 (Figure 7F). Combined with network pharmacological prediction and transcriptome results, it was found that XPQG may be based on the MAPK signaling pathway to realize the “mitochondria-ER” bicellular organelle linkage by regulating the ER stress marker DDIT3 and the downstream antioxidant key target HO-1. As a result, it systematically inhibited lipid deposition, apoptosis and oxidative stress, with the hepatoprotective effect of multi-target-multiplexing integration.

The relative mRNA and protein expression of in vitro and in vivo experiments showed an increase in p38 and DDIT3 after modeling and a gradual decrease after drug gradient intervention. Meanwhile, Nrf2 and HO-1 decreased after modeling and increased after drug intervention (Figure 8A and B). Western blot analysis showed the same results (Figure 8C-F), which supported that the hepatoprotective effect of XPQG was involved in DDIT3 activation.

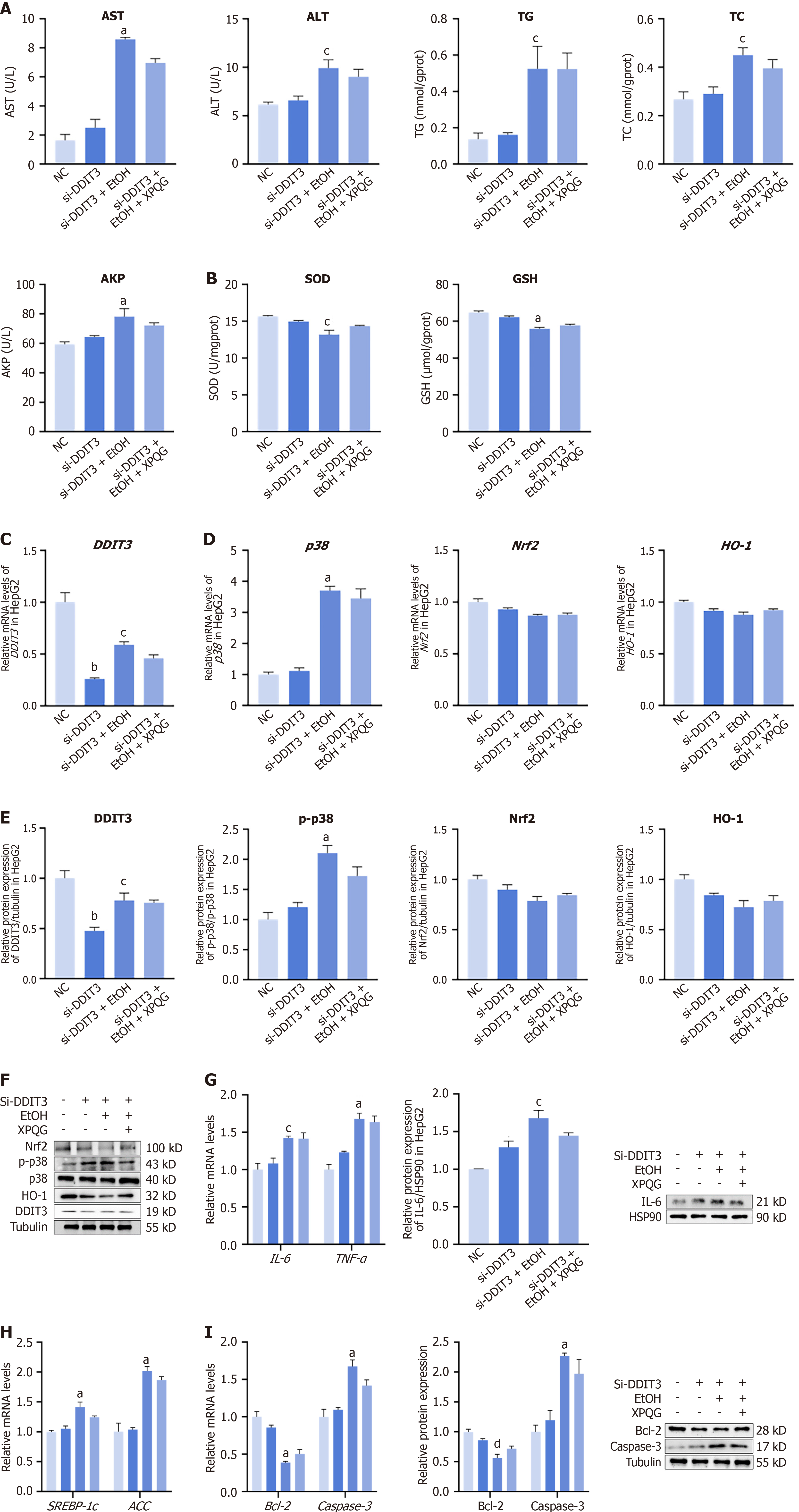

After knockdown of DDIT3, ethanol modeling and re-administration of XPQG showed no significant difference in the expression levels of ALT, AST, TG, TC and AKP in HepG2 cells. This indicated the limited effect of the drug on hepatocyte damage and lipid deposition at this time (Figure 9A). In SOD and GSH detection, the expression of the EtOH group was low and not increased after XPQG administration (Figure 9B). The expression of DDIT3 for further validation of the target protein of XPQG (Figure 9C). Further experiments showed that p38 was not significantly affected after DDIT3 knockdown. The expression levels of Nrf2 and HO-1 in HepG2 cells decreased to a certain extent. Meanwhile, alcohol treatment further reduced the expression level, while XPQG treatment did not change significantly (Figure 9D-F). XPQG also had no significant impact on the relative mRNA levels of lipid metabolism, inflammation, and apoptosis-associated factors in HepG2 cells after transfection, while the protein expression of SREBP1-c, ACC, IL-6, TNF-α, Bcl-2 and Caspase-3 was no longer regulated (Figure 9G-I). After knockout of DDIT3, the improvement effect of XPQG on ethanol-induced liver damage, lipid deposition, oxidative stress, inflammation, and apoptosis basically disappeared. Taken toge

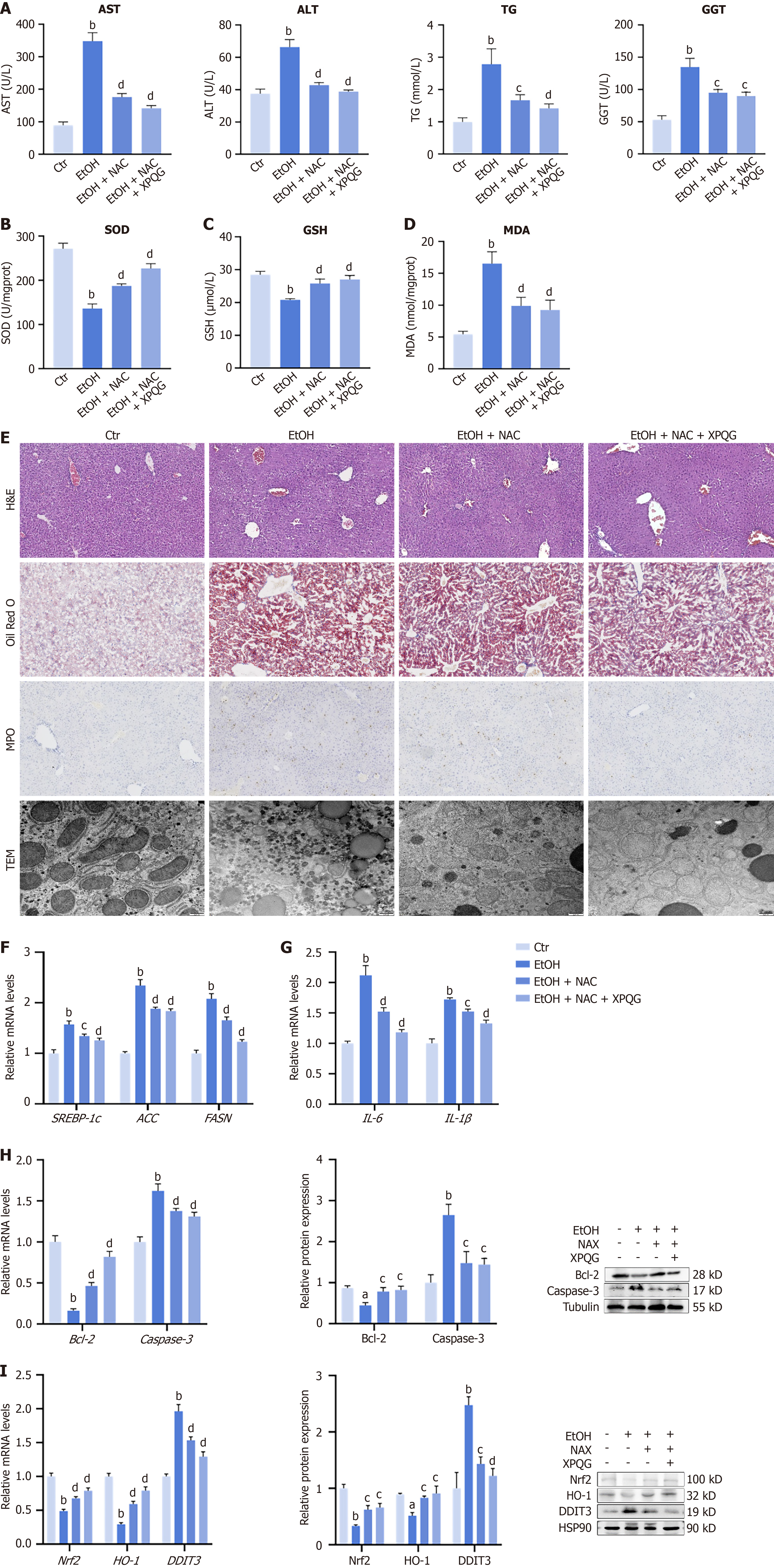

After XPQG administration, the ROS content in HepG2 was found to be reduced at the cellular level. Alcohol-induced liver damage was significantly reversed by NAC treatment, which showed reduced levels of AST, ALT, TG, TC and GGT (Figure 10A). Additionally, alcohol-induced oxidative damage was reversed by NAC administration, which led to an increase in the levels of SOD, GSH and a decrease in the accumulation of MDA (Figure 10B-D). NAC was used experimentally to investigate whether XPQG exerts an oxidative stress inhibition effect on the basis of NAC. Furthermore, H&E staining and Oil Red O revealed that treatment with NAC and XPQG significantly attenuated alcohol-induced liver injury and lipid deposition (Figure 10E). The core value of liver MPO detection is to reflect the degree of neutrophil-mediated inflammation and oxidative stress, which is significantly expressed in the model and decreased after NAC and XPQG intervention (Figure 10E). Compared to the EtOH group, the mitochondrial morphology of hepatocytes in the pair-fed control group, EtOH + NAC group and EtOH + NAC + XPQG group was normal, elongated or oval, the mitochondrial ridge was clear and densely arranged, and there was no mitochondrial swelling (Figure 10E).

In addition, NAC and XPQG also significantly reduced the damage of lipid metabolism, apoptosis and inflammation in the liver tissue (Figure 10F-H). The relative mRNA levels of DDIT3 were reduced, and those of Nrf2 and HO-1 were increased in NAC and NAC + XPQG groups (Figure 10I). To clarify the molecular mechanisms behind these effects, a western blot was applied to explore the decreased expression of DDIT3 and the increased expression of Nrf2, HO-1 in NAC and NAC+XPQG groups (Figure 10I). In conclusion, NAC and XPQG significantly reduced alcohol-induced oxidative stress, inflammatory apoptosis, lipid deposition, and hepatocyte damage by reducing DDIT3 and up-regulating the Nrf2/HO-1 antioxidant axis to restore mitochondrial morphology and function.

The pathological nature of ALD is the vicious cycle of inflammation and oxidative stress. When alcohol is metabolized in the liver, the formation of acetaldehyde is catalyzed by ethanol dehydrogenase and cytochrome P450 2E1 (CYP2E1), accompanied by the release of a large amount of ROS[13]. In addition, alcohol metabolism consumes reduced GSH, the major endogenous antioxidant in the liver, thereby weakening antioxidant defenses[14]. ROS also activates Kupffer cells to release inflammatory factors, which further amplify oxidative damage and drive hepatocyte apoptosis[11]. This highlights the central role of oxidative stress as a “common pathway” for disease progression. DDIT3, also known as CHOP, is a key integrator of oxidative stress and ERS[11]. This study shows that XPQG effectively alleviates liver dysfunction in ALD models, thereby weakening apoptosis, inflammatory response and hepatic steatosis. This protective effect is associated with the suppression of DDIT3, thereby enhancing the Nrf2/HO-1-mediated antioxidant defense. It is further verified that with hepatocyte-specific DDIT3 knockout cells, liver damage was reduced by reduced DDIT3 expression separately. After DDIT3 was knocked down, the effect of XPQG on ALD was significantly weakened. Mechanistically, XPQG may enhance the transcriptional activity of HO-1 by reducing DDIT3 expression and decreasing its competitive binding to Nrf2. Furthermore, when ROS inhibitors such as NAC were used to eliminate free radicals, DDIT3 protein levels also decreased synchronously. It indicates that oxidative stress maintains the stability of DDIT3. In summary, XPQG enhances hepatic antioxidant capacity by suppressing DDIT3 expression, which weakens Nrf2/HO-1 signaling. These findings lay a theoretical foundation for supporting XPQG as a potential therapeutic agent against ALD.

DDIT3, as a key regulator of ERS, has been identified as a central hub connecting liver injury and oxidative stress and emerges as a potential therapeutic target[15]. Key subfamilies of the MAPK family are activated by ethanol and its metabolites through multiple pathways[16]. MAPK can upregulate DDIT3 expression at the level of transcriptional, translational[17]. As a key pro-damage factor downstream of ERS, DDIT3 exacerbates oxidative stress, induces apoptosis and amplifies inflammatory responses through signal interaction and specific target gene regulation, respectively, thereby promoting the progression of disease[18,19]. The effect of XPQG on ALD may be based on MAPK, DDIT3, and HO-1-related genes. It is further verified through experiments that XPQG treatment markedly enhanced the reduction of DDIT3 mRNA and protein expression levels, while increasing the expression of Nrf2 and its target gene HO-1.

Based on the effects of XPQG on DDIT3, Nrf2 and HO-1, whether the decoction can fight alcohol-induced oxidative stress and enhance the antioxidant capacity of the liver is further investigated. XPQG exhibits potent antioxidant effects. Treatment with XPQG significantly reduces MDA levels—a key marker of lipid peroxidation—in both mouse livers and ALD cells. Simultaneously, it enhances the concentration of crucial antioxidants such as GSH and SOD, which effectively suppress the production of ROS in the liver. It is further verified through cell transfection experiments that the regulation of DDIT3 by XPQG is essential for its antioxidant effect in ALD. Baseline expression levels of both Nrf2 and HO-1 are significantly improved by knockdown of DDIT3. However, XPQG had no obvious effect on Nrf2 and HO-1 deficiency. This indicates the unique therapeutic effect of XPQG stems not only from direct activation of the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway. More importantly, inhibition of DDIT3 in this pathway is modulated partially. In the Temporomandibular Joint Osteoarthritis model, DDIT3 overexpression down-regulated HO-1 and markedly suppressed Nrf2 nuclear translocation, with increased ROS levels. DDIT3 deletion reversed these effects, confirming that DDIT3 drives chondrocyte oxidative stress via inhibition of the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway[20].

The pivotal role of XPQG extends beyond its function as a key amplifier of oxidative stress. It drives multiple interconnected pathological processes in ALD—apoptosis, inflammatory cascades and lipid metabolism disorders, generating a complex injury network. In lipid metabolism, the antioxidant reserve of hepatocytes is depleted quickly by massive free radicals generated by alcohol metabolism, thereby triggering steatosis and forcing the abnormal accumulation of TGs[21]. It is verified by experiments based on Oil Red O staining and gene expression analysis that the lipid synthesis is effectively reversed by XPQG treatment. According to mechanistic studies, DDIT3 can activate SREBP-1c, a key regulator of fatty acid synthesis[22]. This activation enhances gene expression of FASN and ACC, thereby promoting hepatic lipid biosynthesis directly. In addition, XPQG also reduces inflammatory responses. The expression of IL6, IL-1β and TNF-α was decreased due to XPQG intervention. Inflammation is exacerbated by alcohol metabolites themselves, which stimulate Kupffer cells and induce oxidative stress[23]. DDIT3 may amplify the inflammatory response in ALD. As found, DDIT3 regulates the inflammatory response by inducing caspase-11 expression, thereby promoting IL-1β maturation and activating caspase-1[24].

Further, XPQG was found to effectively regulate apoptosis in ALD. Hepatocyte apoptosis is not only initiated by death receptor signaling and oxidative stress, but is also effectively regulated by the MAPK cascade and DDIT3[25,26]. MAPK activation, particularly via the p38 pathway, leads to upregulation of DDIT3 transcription and subsequent protein accumulation, contributing to ER stress-mediated apoptosis[19]. Subsequently, the stabilized DDIT3 suppresses the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2, upregulates the pro-apoptotic protein Bim, activates Caspase-9/Caspase-3 cascade, releases cytochrome c, increases MOMP, and triggers apoptosis[27]. As found, XPQG may effectively inhibit hepatocyte apoptosis through suppression of Caspase-3 activation, dose-dependent inhibition of MAPK phosphorylation, reduction of DDIT3 expression, and decrease of the BAX/Bcl-2 ratio. Although this result conforms to observations from other hepatoprotective agents such as silymarin, the unique efficacy of XPQG in ALD is further confirmed. Anti-apoptotic effects are exerted via the MAPK-DDIT3 cascade. In a study of oleic acid-loaded lipid nanoparticles, apoptosis in hepatocytes is induced by DDIT3-mediated activation of the Bcl-2/BAX/Caspase-3 pathway, with increased caspase-3 shear activation and its activity[17]. It is worth noting that although XPQG tended to lower lipid apoptosis, inflammation and deposition after DDIT3 knock-down, the changes no longer reached statistical significance. It means protection is largely DDIT3-dependent. Collectively, these data establish DDIT3 as a crucial driver of ethanol-induced apoptosis, inflammation, steatosis and oxidative stress. XPQG benefits the liver primarily by suppressing DDIT3, thereby relieving the brake on Nrf2/HO-1 antioxidant signalling.

Experiments were conducted using ROS scavenger NAC to further confirm the central role of oxidative stress in the mechanisms of ALD and XPQG. The distinction between XPQG and direct antioxidants was clarified. As found, NAC treatment could directly eliminate ROS and mimic some key protective effects of XPQG, such as reducing liver injury markers (AST, ALT, and TG). Hepatic histological damage and antioxidant levels (SOD and GSH) are increased. Despite no significant interaction between the NAC + XPQG group and the NAC group, it was found that the NAC + XPQG combination produced a superimposed improvement compared to NAC separately. DDIT3 protein is reduced, with higher expression of Nrf2 and HO-1. NAC removed some ROS sources. XPQG seems to be able to further function by inhibiting DDIT3 to drive Nrf2 and HO-1. These findings further support XPQG’s effective restraining of ROS accumulation. More importantly, this independent experiment confirms oxidative stress as a key therapeutic target. XPQG’s protection is achieved by inhibiting DDIT3, which in turn liberates the Nrf2/HO-1 antioxidant axis.

It is clarified that XPQG protects against ALD primarily by suppressing DDIT3 and thereby unleashing Nrf2/HO-1 antioxidant signaling. There are still several limitations. First, XPQG as a multicomponent decoction contains various bioactive compounds with synergistic effects. The individual potency requires verification. Second, the limitation of this study is that the HepG2 cell line used has low levels of alcohol dehydrogenase and CYP2E1. Hence, the process of alcohol metabolism in vivo cannot be fully simulated, despite the induction of oxidative stress through ethanol. Moreover, NAC combination therapy and XPQG can further reduce oxidative stress, but the interaction term was not statistically significant. The superiority of this combination regimen is still descriptive rather than statistically synergistic. Larger studies are required to confirm any true interactions.

This study provides insights into the potential central role of oxidative stress in ALD and its multiple pathological effects on the key molecular hub DDIT3, while revealing the therapeutic targets and mechanisms of the candidate drug XPQG. This study supports the hypothesis that alcohol-induced oxidative stress stabilizes and enhances DDIT3 protein expression through activation of the MAPK pathway. The DDIT3 plays a dual destructive role: On the one hand, it suppresses antioxidant defense by inhibiting Nrf2 nuclear translocation and expression of downstream key antioxidant enzymes such as HO-1, which severely weakens hepatic antioxidant capacity; on the other hand, it promotes apoptosis by activating the BAX/Bcl-2/Caspase-3 pathway, which directly drives hepatocyte death. Additionally, DDIT3 exacerbates hepatic steatosis and inflammatory response by activating lipid synthesis genes and pro-inflammatory signals. These processes reinforce each other to form a vicious cycle of “oxidative stress-inflammatory response-apoptosis-metabolic disorder” that drives ALD progression. The core protective mechanism of XPQG is the effective inhibition of DDIT3 expression. By relieving the dual suppression of DDIT3 (competitive binding and transcriptional inhibition) on the Nrf2/HO-1 antioxidant axis, XPQG significantly enhances hepatic antioxidant capacity. Simultaneously, inhibition of DDIT3 directly blocks its mediated pro-apoptotic, pro-inflammatory, and pro-lipid synthesis signaling pathways. The multi-target inhibition of DDIT3 enables XPQG to comprehensively alleviate alcohol-induced hepatic steatosis, inflammatory response, and apoptosis, which effectively protects liver function. In summary, XPQG disrupts the ALD pathological cycle by inhibiting DDIT3 and thereby enhancing Nrf2/HO-1 antioxidant signaling, rather than targeting a linear DDIT3-Nrf2/HO-1 pathway. This study not only supports the traditional therapeutic value of XPQG from the perspective of modern molecular pharmacology but also provides insights into its mechanism of multi-component synergy, which provides a theoretical foundation for comprehensive treatment strategies.

We thank the staff of the Laboratory Animal Science and Technology Center of Zhejiang University of Chinese Medicine for their professional support in animal husbandry and welfare. We are also grateful to our colleagues in the Department of Hepatology for their helpful discussions and technical assistance during the study.

| 1. | Kourkoumpetis T, Sood G. Pathogenesis of Alcoholic Liver Disease: An Update. Clin Liver Dis. 2019;23:71-80. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Yan C, Hu W, Tu J, Li J, Liang Q, Han S. Pathogenic mechanisms and regulatory factors involved in alcoholic liver disease. J Transl Med. 2023;21:300. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Gao B, Bataller R. Alcoholic liver disease: pathogenesis and new therapeutic targets. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:1572-1585. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1244] [Cited by in RCA: 1546] [Article Influence: 103.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 4. | Kong LZ, Chandimali N, Han YH, Lee DH, Kim JS, Kim SU, Kim TD, Jeong DK, Sun HN, Lee DS, Kwon T. Pathogenesis, Early Diagnosis, and Therapeutic Management of Alcoholic Liver Disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:2712. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 145] [Article Influence: 20.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Mathurin P, Bataller R. Trends in the management and burden of alcoholic liver disease. J Hepatol. 2015;62:S38-S46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 199] [Cited by in RCA: 232] [Article Influence: 21.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Singal AK, Bataller R, Ahn J, Kamath PS, Shah VH. ACG Clinical Guideline: Alcoholic Liver Disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113:175-194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 446] [Cited by in RCA: 595] [Article Influence: 74.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Jophlin LL, Singal AK, Bataller R, Wong RJ, Sauer BG, Terrault NA, Shah VH. ACG Clinical Guideline: Alcohol-Associated Liver Disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2024;119:30-54. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 177] [Cited by in RCA: 156] [Article Influence: 78.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Qu J, Chen Q, Wei T, Dou N, Shang D, Yuan D. Systematic characterization of Puerariae Flos metabolites in vivo and assessment of its protective mechanisms against alcoholic liver injury in a rat model. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:915535. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Tu Y, Zhu S, Wang J, Burstein E, Jia D. Natural compounds in the chemoprevention of alcoholic liver disease. Phytother Res. 2019;33:2192-2212. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Mackowiak B, Fu Y, Maccioni L, Gao B. Alcohol-associated liver disease. J Clin Invest. 2024;134:e176345. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 212] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | LeFort KR, Rungratanawanich W, Song BJ. Contributing roles of mitochondrial dysfunction and hepatocyte apoptosis in liver diseases through oxidative stress, post-translational modifications, inflammation, and intestinal barrier dysfunction. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2024;81:34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Bertola A, Mathews S, Ki SH, Wang H, Gao B. Mouse model of chronic and binge ethanol feeding (the NIAAA model). Nat Protoc. 2013;8:627-637. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 558] [Cited by in RCA: 980] [Article Influence: 75.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Zhang X, Dong Z, Fan H, Yang Q, Yu G, Pan E, He N, Li X, Zhao P, Fu M, Dong J. Scutellarin prevents acute alcohol-induced liver injury via inhibiting oxidative stress by regulating the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway and inhibiting inflammation by regulating the AKT, p38 MAPK/NF-κB pathways. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2023;24:617-631. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 14.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Ding Q, Cao F, Lai S, Zhuge H, Chang K, Valencak TG, Liu J, Li S, Ren D. Lactobacillus plantarum ZY08 relieves chronic alcohol-induced hepatic steatosis and liver injury in mice via restoring intestinal flora homeostasis. Food Res Int. 2022;157:111259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Liu YN, Zhu HX, Li TY, Yang X, Li XJ, Zhang WK. Lipid nanoparticle encapsulated oleic acid induced lipotoxicity to hepatocytes via ROS overload and the DDIT3/BCL2/BAX/Caspases signaling in vitro and in vivo. Free Radic Biol Med. 2024;222:361-370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Chen Y, Gao T, Bai J, Yu L, Liu Y, Li Y, Zhang W, Niu S, Liu S, Guo J. Ge-Zhi-Jie-Jiu decoction alleviates alcoholic liver disease through multiple signaling pathways. J Ethnopharmacol. 2025;337:118840. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Xu D, Wu H, Tian M, Liu Q, Zhu Y, Zhang H, Zhang X, Shen H. Isolinderalactone suppresses pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma by activating p38 MAPK to promote DDIT3 expression and trigger endoplasmic reticulum stress. Int Immunopharmacol. 2024;143:113497. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Verma S, Crawford D, Khateb A, Feng Y, Sergienko E, Pathria G, Ma CT, Olson SH, Scott D, Murad R, Ruppin E, Jackson M, Ronai ZA. NRF2 mediates melanoma addiction to GCDH by modulating apoptotic signalling. Nat Cell Biol. 2022;24:1422-1432. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Reference Citation Analysis (14)] |

| 19. | Li M, Thorne RF, Shi R, Zhang XD, Li J, Li J, Zhang Q, Wu M, Liu L. DDIT3 Directs a Dual Mechanism to Balance Glycolysis and Oxidative Phosphorylation during Glutamine Deprivation. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2021;8:e2003732. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Yang C, Dong W, Wang Y, Dong X, Xu X, Yu X, Wang J. DDIT3 aggravates TMJOA cartilage degradation via Nrf2/HO-1/NLRP3-mediated autophagy. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2024;32:921-937. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Albano E. Oxidative mechanisms in the pathogenesis of alcoholic liver disease. Mol Aspects Med. 2008;29:9-16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 205] [Cited by in RCA: 223] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Lu J, Wang C. Ferulic acid from Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels ameliorates lipid metabolism in alcoholic liver disease via AMPK/ACC and PI3K/AKT pathways. J Ethnopharmacol. 2025;338:119118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Chadha P, Aghara H, Johnson D, Sharma D, Odedara M, Patel M, Kumar H, Thiruvenkatam V, Mandal P. Gardenin A alleviates alcohol-induced oxidative stress and inflammation in HepG2 and Caco2 cells via AMPK/Nrf2 pathway. Bioorg Chem. 2025;161:108543. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 24. | Diaz-Perez JA, Kerr DA. Gene of the month: DDIT3. J Clin Pathol. 2024;77:211-216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Li D, Li Z, Dong L, Zhang Y, Lu Y, Wang J, Sun H, Wang S. Coffee prevents IQ-induced liver damage by regulating oxidative stress, inflammation, endoplasmic reticulum stress, autophagy, apoptosis, and the MAPK/NF-κB signaling pathway in zebrafish. Food Res Int. 2023;169:112946. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Xiao F, Li H, Feng Z, Huang L, Kong L, Li M, Wang D, Liu F, Zhu Z, Wei Y, Zhang W. Intermedin facilitates hepatocellular carcinoma cell survival and invasion via ERK1/2-EGR1/DDIT3 signaling cascade. Sci Rep. 2021;11:488. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Šrámek J, Němcová-Fürstová V, Kovář J. Molecular Mechanisms of Apoptosis Induction and Its Regulation by Fatty Acids in Pancreatic β-Cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:4285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/