Published online Feb 28, 2026. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v32.i8.114571

Revised: November 19, 2025

Accepted: January 4, 2026

Published online: February 28, 2026

Processing time: 140 Days and 15 Hours

Primary melanomas of the gastrointestinal tract are rare malignancies, representing less than 2% of all melanomas and 37% of mucosal melanomas. They arise de novo from the mucosal gastrointestinal epithelium, most frequently in the anorectum and esophagus. Their etiology is unclear: Unlike cutaneous mela

Core Tip: Gastrointestinal primary melanomas are very rare, with literature comprised of isolated case reports and small series. Compared with cutaneous melanoma, they display distinct molecular profiles, more aggressive clinical behavior, poorer prognoses with less favorable response to systemic therapy. These tumors have been poorly researched, and, because of their rarity, development of standardized management has been delayed. The present review shows all the relevant domains, including epidemiology, etiology, molecular features, diagnosis, and therapy, offering a general profile of this challenging and poorly studied disease.

- Citation: De Nardi P, Guida S, Damiano G, Rizzo N, Samanes Gajate AM, Riva ST, Paolino G, Colombo M, Tummineri R, Rongioletti F, Mercuri SR, Chiti A, Sileri P, Russo V. Primary melanoma of the gastrointestinal tract. World J Gastroenterol 2026; 32(8): 114571

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v32/i8/114571.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v32.i8.114571

Melanoma is a malignant neoplasm arising from melanocytes, pigment-producing cells primarily located in the skin. Cutaneous melanoma accounts for most cases and has been extensively studied due to its increasing incidence worldwide. Mucosal melanoma is a rare subtype of melanoma that arises in the mucous membranes lining internal organs’ surface. Among them, primary melanoma of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract is an exceptionally rare entity, comprising less than 2% of all melanomas and about one-third of mucosal melanomas. The GI tract is more commonly a site of metastasis for cutaneous melanoma, making the diagnosis of a primary GI melanoma both unusual and controversial[1-4].

The present review synthesizes current knowledge on primary GI melanomas, and comprehensively addresses epidemiology, pathogenesis, molecular mechanisms, and genetic alterations, that may underlie their development, anatomical distribution, clinical presentation across different segments of the GI tract, diagnostic approach, treatment strategies, criteria used to confirm primary origin, prognostic outcomes, and future directions for research, including the potential of emerging therapies and the importance of multicenter collaboration in further advancing clinical understanding and improving patient outcomes.

To provide an updated and comprehensive overview, a literature search was conducted in PubMed and the Cochrane Database with no language or time restrictions. When multiple articles addressing the same topic were identified, the most recent studies were selected. Due to the paucity of available evidence, case reports and small series reports were also included. This approach was considered appropriate, as the rarity of the condition results in a lack of high-level evidence. By consolidating available evidence, we aim to clarify the unique features of this rare malignancy and highlight the knowledge gaps that hinder early diagnosis and effective treatment.

Primary GI melanoma is an exceedingly rare malignancy, accounting for a small fraction of all melanomas. Among mucosal melanomas, which represent approximately 1%-2% of all melanomas, almost 37% arise in the GI tract. Population-based studies have reported an incidence ranging from 0.36 to 0.58 cases per million, with a trend toward increasing frequency over recent decades[3]. This rise may reflect improved diagnostic capabilities and heightened clinical awareness, although the overall burden remains minimal compared to cutaneous melanoma. The anorectum is the most frequently affected location, with case reports ranging from several hundred to over a thousand, according to institutional and registry data[5]. Esophagus and stomach show an intermediate incidence with 300 and 50 cases respectively[6,7]. For colonic melanoma only 30 cases to 50 cases are reported after careful ruling out metastatic disease. Small bowel localizations are more rare and only a few dozen cases described in the literature are truly primary[8]. A key epidemiological distinction needs to be made between primary and metastatic GI melanomas. Metastatic involvement of the GI tract is far more common, occurring in up to 60% of patients with advanced cutaneous melanoma. These secondary lesions often present years after the initial diagnosis and are typically located in the small intestine, stomach, or colon[9].

Primary GI melanoma mostly affects older adults, with a median age of approximately 70 years at diagnosis. The disease has a slight male predominance (approximately 56%), and most cases occur among non-Hispanic whites. There is some geographic variation, with higher mucosal melanoma rates reported in Asian populations compared to Caucasians, suggesting potential genetic or environmental influences. Interestingly, patients residing in non-metropolitan areas seem to have worse outcomes, possibly due to delayed diagnosis and limited access to specialized care[10]. Risk factors are not well defined. Unlike cutaneous melanoma, which is strongly associated with ultraviolet (UV) radiation exposure, UV exposure plays no role in primary GI melanoma. Some studies have identified human immunodeficiency virus infection as a potential risk factor for anorectal mucosal melanoma, likely due to immunosuppression. However, no clear environmental or lifestyle-related risk factors have been consistently associated with primary GI melanoma, underscoring the need for further etiological research[6,11,12].

The development of primary GI melanoma, particularly in the stomach, challenges traditional concepts regarding melanocyte biology. Unlike cutaneous melanoma, which arises from melanocytes located in the epidermis, the GI tract is not typically considered a site rich in melanocytic cells. However, histological studies have identified melanocytes in the mucosa of the esophagus, stomach, and anorectum, even in healthy individuals, at rates up to 8% in some populations[7]. This supports the potential for de novo melanocytic transformation within the GI tract. Current hypotheses suggest that primary GI melanoma may arise from ectopic melanocytes, or their precursors, that aberrantly migrated from the neural crest during embryogenesis. Another hypothesis suggests that APUD cells, neuroendocrine cells of neural crest origin, may differentiate into melanocytes under certain conditions, though the exact biological process remains unclear. A third possibility involves Schwannian neuroblast cells, which also originate from the neural crest and contribute to the autonomic innervation of the gut. These cells may undergo malignant transformation into melanoma. Supporting this idea is the observation of melanosis in the upper GI tract of patients with rectal melanoma, indicating a potential pre-existing melanocytic substrate capable of neoplastic change[6].

From a molecular point of view, primary GI melanomas exhibit a distinct genetic profile compared to cutaneous melanoma[13]. Whole genome/exome studies demonstrate that mucosal melanoma shows a relatively low tumor mutational burden and lack UV radiation signature. They present instead a high number of structural variants and copy-number alteration[14]. Additionally, frequencies of mutations vary according to anatomical locations and accounts for 30%-40% of cases, being higher in anorectal districts. KIT mutations are the most frequent driving events, particularly in anorectal melanoma, ranging from 15% to 40%. In approximately 10%-20% of cases NRAS mutations are present and are reported as the most common in the esophagus in approximately 33% of cases. BRAF mutations are rare (5%-10%) and mainly found in gastric and small bowel melanomas. NF1 and SF3B1 mutations have also been identified in subsets of cases. This mutational pattern is very different from that seen in cutaneous melanoma, where BRAF V6000E prevails. Other genetic alterations include cyclin-dependent kinase pathway dysregulation, with amplification of cyclin D1 and loss of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A, implicated in mucosal melanoma pathogenesis and platelet-derived growth factor receptor α expression, more common in mucosal than UV-related melanomas, suggesting alternative oncogenic pathways[15-19].

These findings further emphasize the molecular heterogeneity of mucosal melanomas and highlight the need for genotyping in guiding personalized treatments. The distinct genetic landscape also reiterates that mucosal melanoma follows a different oncogenic trajectory than its cutaneous counterpart, with implications for both diagnosis and therapy. Table 1 compares epidemiology, pathogenesis, molecular features, and clinical outcomes of cutaneous and mucosal/GI melanomas.

| Feature | Cutaneous melanoma | Mucosal/GI melanoma |

| Incidence | > 90% of all melanomas. Increasing global incidence (approximately 25/100000) | 1%-2% of melanomas; GI primaries < 0.5% |

| Typical sites | Skin (trunk, extremities, head-neck) | Anorectum (55%-60%), esophagus (10%-15%), stomach (10%-12%), small bowel (5%-8%), colon (3%-5%) |

| Etiologic factors | Strongly related to UV exposure and intermittent sunburns; BRAF-driven oncogenesis common | Not related to UV radiation; may derive from ectopic melanocytes or APUD/Schwannian precursors |

| Median age at diagnosis | 55-60 years | Approximately 70 years |

| Gender distribution | Slight male predominance | Similar or slightly male-predominant |

| Clinical presentation | Visible or pigmented skin lesion; early detection frequent | Non-specific GI symptoms (bleeding, anemia, obstruction, pain); diagnosis often delayed |

| Stage at diagnosis | Approximately 80% localized; 10%-15% metastatic | < 35% localized; majority advanced or metastatic |

| Median OS | Localized > 10 years; stage IV ≈ 20-30 months (immunotherapy era) | Median 14-20 months overall; < 6 months for gastric, approximately 24 months for anorectal |

| Prognosis | Significantly improved with immunotherapy (5-year OS ≈ 52% in CheckMate-067) | Poorer outcomes due to late diagnosis and intrinsic aggressiveness; 5-year OS < 20% |

| Histopathology | Often pigmented, epidermal origin, radial/vertical growth phases | Frequently amelanotic, submucosal, polypoid or ulcerated; high mitotic index |

| Molecular profile | BRAF (40%-50%), NRAS (15%-25%), NF1 (10%), KIT rare (< 3%) | KIT (15%-40%), NRAS (10%-20%), BRAF (5%-10%), NF1 (10%-15%), SF3B1 (5%-10%) |

| Tumor mutational burden | High; UV-signature mutations frequent | Low; structural/copy-number variations |

| Response to immunotherapy | High (ORR = 40%-60%, OS: 20 months to > 50 months) | Lower (ORR = 20%-30%, OS: 11-16 months) |

| Targeted therapy options | BRAF/MEK inhibitors (dabrafenib, trametinib, vemurafenib) | KIT inhibitors (imatinib, nilotinib); rare BRAF-targeted cases |

| Main causes of death | Distant metastases (lung, brain, liver) | Distant metastasis (liver, peritoneum) |

| Molecular testing recommendation | BRAF testing standard for advanced disease | Mandatory KIT, NRAS, BRAF, and NF1 sequencing for all cases |

Primary GI melanomas arise from the mucosal or submucosal layer and may appear as polypoid, ulcerated, or infiltrative masses, often with variable pigmentation. Microscopically they are composed of sheets and large nodules of pleomorphic epithelioid cells or, less commonly, spindle-shaped or ovoid cells. The nuclei contain nucleoli and vesicular chromatin. The presence of an adjacent intraepithelial or superficially invasive component of atypical melanocytes supports a mucosal primary. Less frequently a lentiginous proliferation showing single atypical melanocytes along basal layer may be seen, occasionally accompanied by nests of confluent growth[20]. Primary GI melanomas often display an in-situ component characterized by junctional melanocytic proliferation or pagetoid spread within the overlying mucosa, findings that are absent in metastatic deposits, which typically reside in the submucosa or deeper layers without epithelial involvement. Demonstration of an in-situ component is considered the strongest histological evidence of a primary origin.

Melanin production is variable but usually at least locally present within both melanoma cells and background macrophages. Immunohistochemical staining is essential for diagnosis, particularly for amelanotic variants. S100 is the most sensitive marker, while HMB-45, PRAME, Melan-A (MART-1), and SOX10 are commonly used. SOX10 is particularly sensitive and specific for melanocytic lineage and CD117 being more frequent in mucosal melanoma. Ki-67 is typically elevated, reflecting the tumor’s high proliferative index. In amelanotic variants, these markers are particularly valuable to differentiate melanoma from poorly differentiated carcinoma, lymphoma, or GI stromal tumor[21,22]. Ultrastructural features, such as the presence of pre-melanosomes on electron microscopy, can confirm melanocytic origin when immunohistochemistry is equivocal.

Differential diagnosis between primary GI melanoma and metastatic melanoma is a challenge. Melanoma should be tested for BRAF and KIT mutations. BRAF V600E mutations favor a cutaneous origin, whereas the predominance of KIT or NRAS mutations, together with a low tumor mutational burden, without a UV radiation signature, numerous chromosomal structural variants and abundant copy-number changes, including multiple high-level amplifications, supports a mucosal or primary GI melanoma phenotype[23].

Integration of histological, immunophenotypic, and molecular data remains essential for accurate classification and for guiding therapeutic decisions. Currently, American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging system does not include mucosal melanomas of the GI tract, and therefore no specific tumor-node-metastasis classification is available for these tumors. In the 8th edition of the AJCC staging system, the classification is limited to mucosal melanoma of the head and neck within the upper aerodigestive tract. Consequently, the AJCC criteria cannot be fully applied to GI melanomas. Pathological report should describe parameters such as tumor size, tumor mitotic rate, ulceration, BRAF mutation status, margin involvement, invasion of surrounding tissues, and the number, size and status of the resected lymph-nodes. For mucosal melanoma of the upper airways, the AJCC system does not include T1-2 categories and local extent is cate

Primary GI melanomas pose a diagnostic challenge due to their symptoms overlap with more common GI disorders. Patients may remain asymptomatic until the tumor progresses. GI bleeding is the most frequent presenting sign. Depending on tumor location hematemesis or melena may occur. Occult bleeding, leading to iron-deficiency anemia, is also frequently observed, which may result in malaise and persistent fatigue. A case series reported GI bleeding in 57.1% of primary cases and in 70.4% of metastatic ones[26,27]. Abdominal pain is also very common, reported in up to 64% of cases[28,29]. Other common symptoms include unexplained and progressive weight loss, dyspepsia, loss of appetite, nausea and vomiting. Dysphagia may be an early symptom in case of esophagus involvement[30] while gastric melanoma may present with anorexia, vomiting and weight loss[6]. In case of small bowel melanoma, intestinal obstruction and intussusception may occur with melanoma being the lead point[31]. Bowel perforation has also been exceptionally reported as a possible emergent presentation[29]. These severe complications may prompt urgent clinical attention. Because of the nonspecific nature of these symptoms, diagnosed is often delayed.

Instrumental diagnosis plays a crucial role in identifying the site of origin, characterizing the lesion, and staging the disease. The most useful modalities include endoscopy with biopsy, contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and positron emission tomography-CT (PET-CT). Given that GI bleeding represents the most frequent presenting symptom, endoscopic evaluation is typically undertaken to identify the source. Endoscopy provides direct visualization and tissue sampling. When standard esophagogastroduodenoscopy and colonoscopy cannot identify any lesion the entire GI tract can be investigated with capsule enteroscopy (CE) and/or balloon assisted enteroscopy while cross-sectional imaging (CT, MRI) and PET-CT are essential for staging and for excluding cutaneous or ocular primaries[5,32].

Esophagus: Primary esophageal melanoma usually presents as submucosal or polypoid mass with moss on the surface, melanin pigmentation or amelanotic, with or without ulceration. A case of discoloration in the mid-distal esophagus without any obvious mass has been also described[25]. Endoscopic ultrasound is frequently employed to assess the depth of invasion and involvement of periesophageal lymph nodes, thus providing valuable staging information[32].

Stomach: Lesions are often detected incidentally during upper endoscopy performed for nonspecific symptoms. Endoscopically, they may appear as pigmented ulcerated masses, with sharp edges, although amelanotic variants, which resemble adenocarcinoma or GI stromal tumors, are not uncommon. More rarely multiple small black nodules or umbilicated gastric ulcer have been reported[27].

Small bowel: The diagnosis is particularly challenging because of limited endoscopic access. CE has a better resolution than conventional CT, allowing a better surgical planning[33]. Balloon-assisted enteroscopy is also valuable for direct visualization of the mucosa and tissue sampling. CT or MR enterography plays a central role in assessing mural infiltration and extraluminal extension[33].

Colon: Primary melanoma appears at colonoscopy as polypoid or ulcerated lesions, but most of them are amelanotic, which complicates the diagnosis. Biopsy followed by immunohistochemistry is therefore essential to confirm the diagnosis[34].

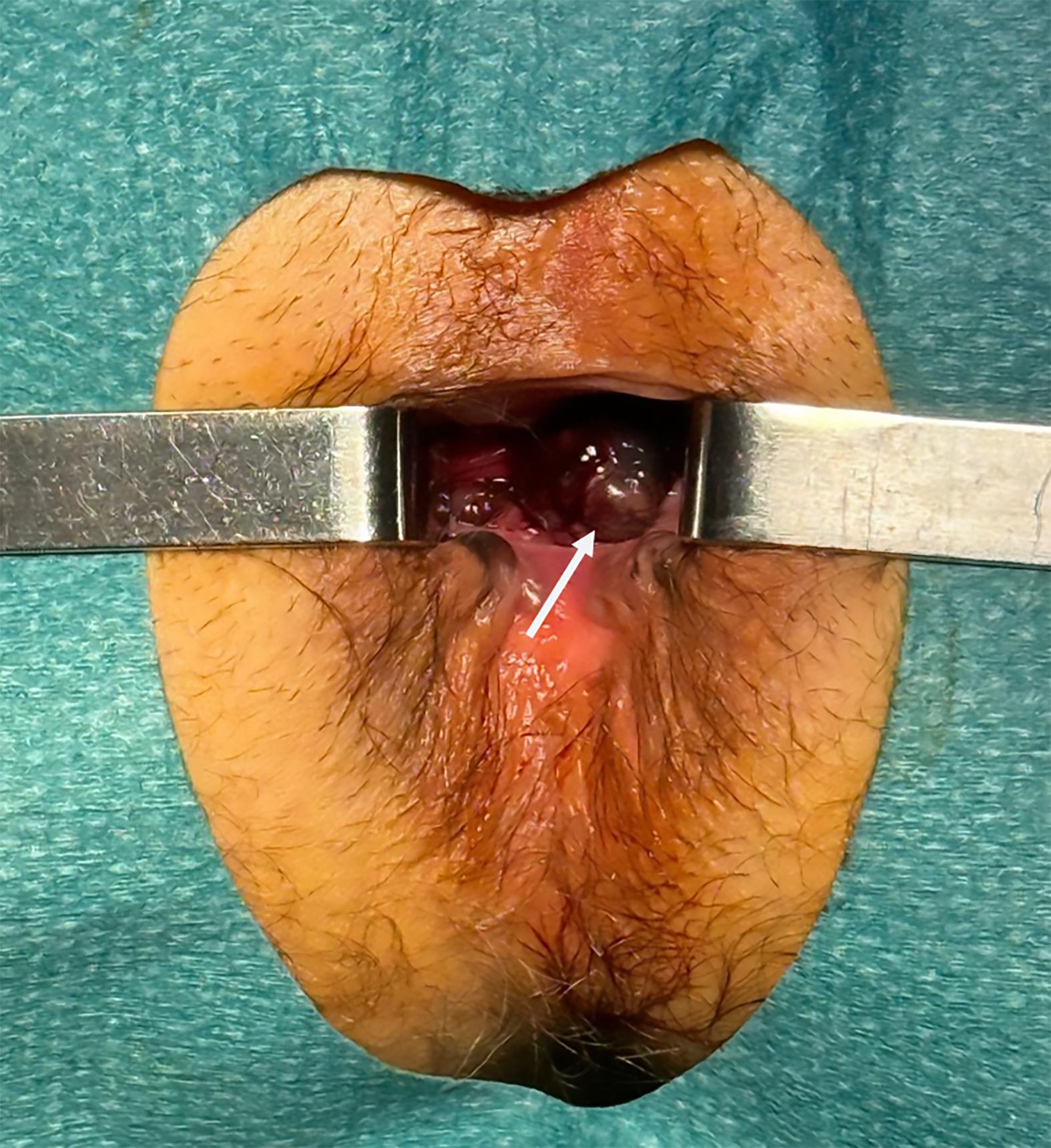

Anorectal: Clinical suspicion is often delayed as lesions may mimic benign conditions such as hemorrhoids or anal fissures. Endoscopy and digital rectal examinations generally reveal a pigmented polypoid or ulcerated mass, taking the shape of spots, patches, or sheets (Figure 1). In other cases, no melanion pigmentation is observed with lump-type lesions with superficial ulcer covered with yellow moss and little bleeding[32]. Pelvic MRI is the gold standard for local staging, as it provides high-resolution assessment of tumor extension and mesorectal and inguinal lymph node involvement[35].

Fluorodeoxyglucose PET (FDG-PET) or PET/CT, are recommended for staging and follow-up of patients with III and IV cutaneous melanoma[36] but their role in primary GI melanoma is less defined. In the GI tract, PET can support the diagnosis of primary lesions by excluding other primary sites[37]. For staging, FDG-PET has demonstrated superior sensitivity compared to conventional imaging in identifying nodal and distant metastases, also revealing occult metastases[38,39]. Limitations include false positives due to inflammatory conditions and reduced sensitivity for small-volume nodal disease[40].

Brain metastases appear less common in mucosal melanoma compared with cutaneous melanoma; a recent meta-analysis reported an incidence of brain metastasis at diagnosis, of 9.4% among 96 mucosal melanoma patients. Due to the low number and lack of high-quality evidence, no recommendations are available in guidelines for the decision on when imaging the brain in mucosal melanoma[41]. However, if radical resection is considered, brain MRI should be always performed.

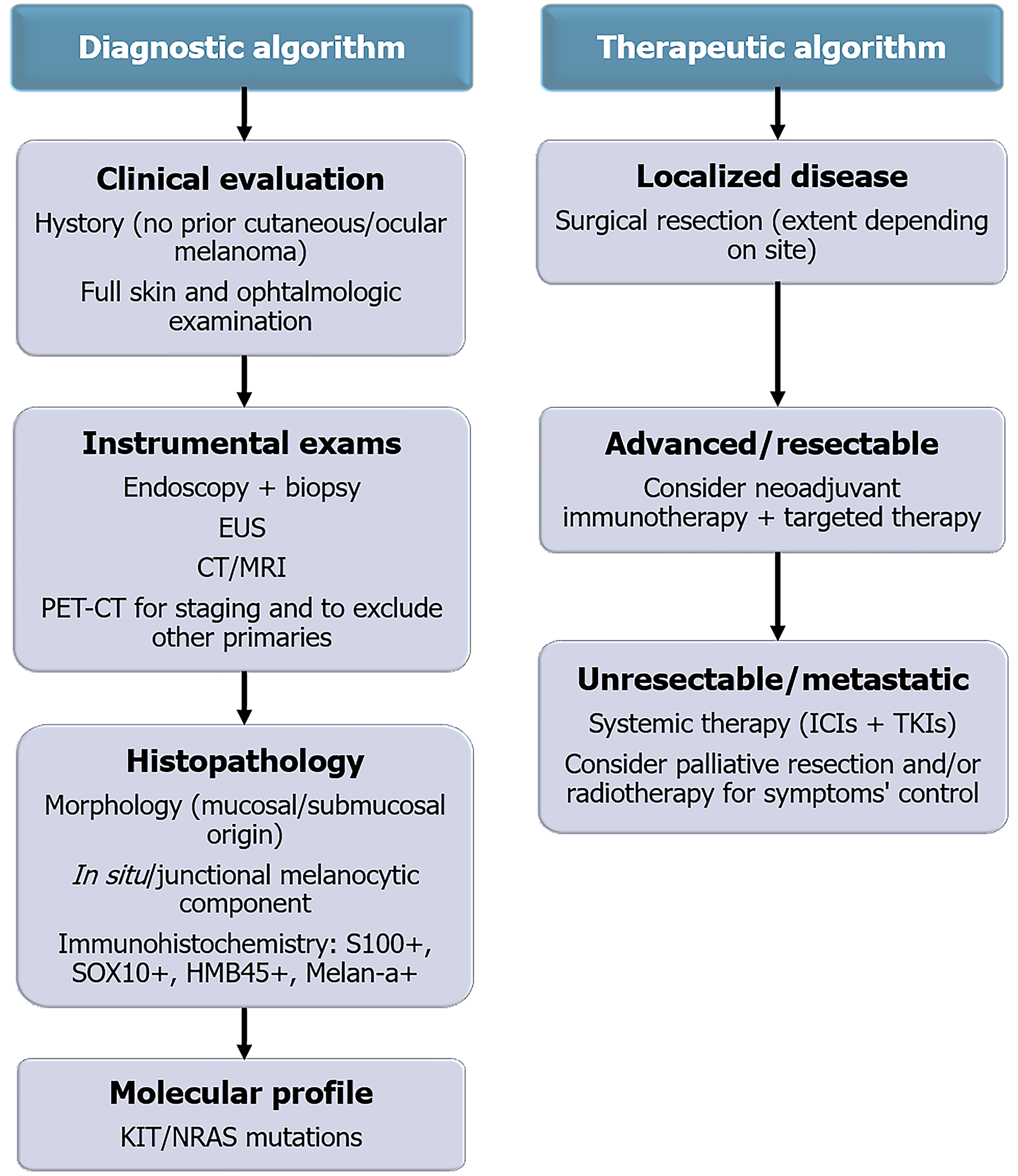

Distinguishing a primary GI melanoma from a metastatic lesion remains one of the greatest diagnostic challenges. A diagnosis of primary origin requires a multidisciplinary approach integrating clinical, radiologic, histologic, and molecular data. Clinically, the absence of any previous or concurrent cutaneous, ocular, or other mucosal melanoma must be confirmed through a full skin examination and ophthalmologic evaluation. Radiologically, whole-body FDG-PET/CT is essential to exclude other primary sites. Histologically, the demonstration of an intraepithelial component or junctional melanocytic proliferation within the mucosa overlying the tumor represents the most reliable evidence of a primary origin. Immunohistochemistry supports the diagnosis by confirming melanocytic lineage, while molecular profiling helps exclude metastatic disease from cutaneous melanoma. The integration of these elements allows a stepwise diagnostic approach, summarized in Figure 2.

Primary GI melanomas tend to present at advanced stage and are therefore associated with poor survival outcomes[42]. According to a SEER database, including 1080 patients diagnosed between 1975 and 2016, only 32.7% of primary GI melanoma had localized disease at presentation, while 24.7% and 30.8% had regional spread and distant metastasis respectively. The higher rate of metastatic involvement was seen in gastric (53.8%) and small intestinal melanoma (50%)[3].

Across all GI sites, systemic recurrence represents the predominant pattern of failure, while local or regional relapse is comparatively uncommon. Distant metastases, particularly to the liver, lungs, and peritoneum, occur in more than half of patients, often within the first 12-18 months after resection[3,12,42,43]. Median overall survival (OS) varies according to tumor location, ranging from 10-15 months for esophageal and gastric melanoma to 12-24 months for small bowel, colonic, and anorectal lesions, with 5-year survival rarely exceeding 20%. Table 2 summarizes the frequency and survival outcomes of primary GI melanoma by site.

| Site | Relative frequency | Median OS (months) |

| Anorectum | 50%-60% | 18-24 |

| Esophagus | 8%-12% | 10-15 |

| Stomach | 7%-10% | Approximately 6 |

| Small bowel | 7%-9% | 12-24 |

| Colon | 3%-5% | 15-20 |

When contextualized within the broader spectrum of mucosal melanomas, primary GI melanomas show survival outcomes and therapeutic challenges comparable to, and in some cases worse than, other mucosal sites. Al-Haseni et al[43] reported a 26.4 months, 43.9 months, and 19.5 months median survival for head and neck, genitourinary and GI cases, respectively. Sinonasal and vulvovaginal melanomas typically present at a locally advanced or metastatic stage and similarly carry a poor prognosis, with 5-year survival consistently below 20%. Genitourinary mucosal melanomas appear to have slightly better survival (median OS ≈ 20-26 months) than GI and sinonasal subtypes, although still inferior to cutaneous disease[44].

Surgery remains the cornerstone of treatment; however, the extent of resection, and the role of lymphadenectomy are being debated across different anatomical sites. The surgical decision making between limited and radical resections must balance oncological radicality with postoperative morbidity and quality of life, particularly in anorectal disease. Recently, the development of new systemic therapies, including immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), have also affected surgical strategies[45,46].

For primary esophageal melanoma esophagectomy with regional lymphadenectomy remains the most common procedure, which allows negative resection margins and nodal staging. However, high perioperative morbidity and early systemic failure with uncertain survival benefit, must be considered[46]. Limited resections or endoscopic resections are technically possible but seldom carried out because of the infiltrative growth, longitudinal spreads, and early nodal metastasis[47]. In case of non-metastatic primary gastric melanoma partial or total gastrectomy with regional lymph nodes removal is advised. While wedge/Local resections may be considered for very small, well-circumscribed lesions, these approaches are often inadequate due to the tumor tendency to be multifocal and biologically aggressive.

The standard treatment for primary melanoma of the small intestine is segmental resection with clear surgical margins. Extensive multivisceral or radical resections usually do not provide additional benefit. Lymphadenectomy is not routinely performed and is generally limited to nodes that appear clinically suspicious[46,48]. Treatment for primary melanoma of the colon generally follows the protocol for colon cancer, involving segmental colectomy or hemicolectomy[49-51]. Even with aggressive surgical approaches, the risk of recurrence remains high, and the therapeutic benefit of comprehensive lymph node dissection beyond staging purposes is uncertain.

At the time of diagnosis of anorectal melanoma about 60% of patients already have metastases in the mesorectal or inguinal lymph nodes[4,49]. Treatment typically involves either local excision (LE) or abdominoperineal resection (APR). While APR allows for higher rates of complete tumor removal (R0) and lymph node assessment, it also comes with significant risks, including major complications and the need for permanent stoma. LE, on the other hand, maintains bowel function but increases the likelihood of incomplete tumor removal and local recurrence and does not allow for lymph node evaluation[5,52,53]. Most studies have not found a survival benefit for APR over LE, as systemic relapse is the primary cause of death, affecting 50%-70% of patients within two years. On the other hand, local recurrence occurs in approximately 30%-40% of patients after LE, significantly higher than after APR. Negative resection margins, more likely to be achieved after APR, significantly predict long term survival[54,55]. Although organ-preserving approaches are increasingly favored in the era of immunotherapy, reflecting the limited impact of radical surgery on survival, a recent systematic review by Paolino et al[54] reported that APR is still performed in most patients (76%), underscoring the ongoing debate on the optimal extent of resection in this setting.

The role of sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) has been inconsistently studied. Unlike for cutaneous melanoma, in which the role of SLNB is established, for mucosal melanomas the supporting literature is sparce, particularly for those of the GI tract. In anorectal melanoma, although evaluated in small cohort, SLNB is technically feasible with a principal role in staging but with uncertain therapeutic advantage[56,57].

In conclusion, surgical therapy of GI tract mucosal melanomas must be customized for anatomical site, clinical stage of disease, and patient comorbidity. Radical resections may provide local control, however, often do not lead to better survival. In contrast limited resections, aiming to preserve function and quality of life, although not considered the standard of care, are becoming increasingly accepted, especially for the anorectal region. The question of lymphadenectomy remains controversial. Although nodal metastasis is frequent, especially for anorectum and esophagus, there has been no definitive demonstration of OS benefit with extensive nodal dissection. Its application now comes largely with staging and prognostic grouping only.

State-of-the-art systemic therapy, is redefining the treatment paradigm. Zhang et al[58] provided a comprehensive overview of current and emerging targeted therapies for acral and mucosal melanoma. The authors underscore the importance of integrating systemic therapy, particularly with ICIs, and molecularly targeted drugs, with regional approaches to allow less extensive and more function-preserving surgical or endoscopic procedures, even in cases previously deemed unresectable[45,59,60]. Neoadjuvant combinations of ICIs and anti-angiogenic agents, such as toripalimab with axitinib, have shown promising response rates and may improve operability[61]. Although radio

Immunotherapy represents the main systemic approach for advanced and metastatic melanoma. ICIs, including anti-programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) antibodies (nivolumab, pembrolizumab) and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 blockade (ipilimumab), have markedly improved OS in cutaneous melanoma; however, their activity in mucosal subtypes remains limited.

This reduced efficacy may be explained by the lower tumor mutational burden, absence of UV-induced mutational signatures, and a less inflamed tumor microenvironment typical of mucosal melanoma, characterized by reduced programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression and a lower density of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes. Consequently, response rates to single-agent PD-1 blockade remain around 15%-25%, and approximately one-third with dual checkpoint inhibition. Novel strategies under investigation include combined immunotherapy with anti-angiogenic agents (e.g., axitinib), adoptive T-cell transfer, and personalized neoantigen vaccines[67-69].

As previously discussed, the frequency of BRAF mutations in mucosal melanomas is much lower than that of cutaneous melanomas, while that of the c-KIT would prevail, with no significant differences depending on the anatomical districts. However, it is suggested that all mucosal melanomas patients are tested for BRAF mutations; the combined treatment with BRAF and MEK inhibitors may be considered when BRAF mutations or BRAF fusions are identified[25]. In a small cohort of 125 patients with advance (metastatic or unresectable), BRAF V600E-mutant mucosal melanoma, BRAF inhibitors therapy obtained an objective response rate (ORR) of 20% and a disease control rate of 70%[66]. Several tyrosine kinase inhibitors, such as imatinib or nilotinib, targeting mutated c-KIT, were shown to induce clinical responses in patients affected by mucosal melanomas. Although limited in number, some clinical experiences have shown significant responses with the use of c-KIT inhibitors in mucosal melanomas that present mutations in exon 9, 11 or 13 especially in anorectal and gastric mucosal melanoma[27,70-73]. Treatment with imatinib mesylate achieved a 64% of ORR in patients with mucosal melanoma carrying KIT mutation (in exon 11, 13, and 17), but it proved ineffective in patients with KIT amplifications, as shown in a multicenter phase 2 trial[74]. The effects of ICI treatment in mucosal melanomas are limited, due to the low number of patients deriving from small population studies, retrospective analyses, and case reports[74-77].

In a multicenter retrospective study, immunotherapy (anti-PD-1 and anti-cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4) was compared with chemotherapy (predominantly dacarbazine) in patients with advanced mucosal melanoma; a median OS of approximately 16 months and 8.8 moths was reported with ICIs and chemotherapy respectively[78]. A clinical trial on 121 patients with advanced mucosal melanomas, treated with nivolumab or nivolumab + ipilimumab, showed a response rate of approximately 23% for nivolumab single agent and 37.1% for the combination. The median progression-free survival (PFS) was 3.0 months for nivolumab and 5.9 months for nivolumab + ipilimumab, highlighting markedly lower efficacy compared with cutaneous melanoma[63]. A sub analysis of the CheckMate 067 study (randomized phase III first line in patients with advanced melanoma: Nivolumab + ipilimumab vs nivolumab vs ipilimumab) evaluated the activity and efficacy of immunotherapy in patients with mucosal melanoma (n = 79, out of 945 patients enrolled in the study). The mucosal origin of the melanoma was not a stratification factor for the study. Twenty-eight patients were treated with the nivolumab + ipilimumab combination, 23 with nivolumab and 28 with ipilimumab. Five years PFS and OS were 29%, 14% and 0%, and 36%, 17% and 7% in the combination, nivolumab single agent, ipilimumab single agent arms, respectively. The response rate was 43%, 30% and 7% in the combination, nivolumab single agent and ipilimumab single agent arms, respectively[78].

Efficacy data for pembrolizumab in mucosal melanoma from the KEYNOTE 001-002-006 trials were also presented. Of the 1567 patients studied, 84 had advanced mucosal melanoma. The ORR was 19%, while the median PFS and OS were 2.8 months and 11.3 months respectively. The treatment demonstrated comparable activity also in the subgroup pretreated with ipilimumab[79,80]. The phase 2/3 relativity-047 clinical trial, included 714 melanoma patients, 51 of whom were mucosal melanoma. No significant difference in PFS was observed in a subgroup analysis comparing 23 cases undergoing the relatlimab-nivolumab combo and 28 cases undergoing nivolumab alone. Additional studies were advocated to understand the efficacy of the relatlimab-nivolumab combo in this patient population often excluded from clinical trial due to small sample size and the rarity of disease[81].

Overall, it remains unclear why mucosal melanomas exhibit lower response rates to ICIs compared with cutaneous melanoma. One hypothesis suggests that this difference may reflect the lower proportion of mucosal melanoma cases with high PD-L1 expression (> 5%), as indicated in the pooled analyses, although no definitive evidence supports PD-L1 as a predictive biomarker for ICI response in these patients. Alternatively, the generally lower mutational burden of mucosal melanomas, with respect to cutaneous lesions, may help explain this clinical behavior. Additionally, the presence of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes may serve as a predictor of response to anti-PD-L1 therapy[62]. There is no data to date demonstrating the efficacy of adjuvant therapy in mucosal melanoma patients. Now, with the limitations of the lack of adequate available evidence, adjuvant treatment for mucosal melanomas could mimic that of cutaneous melanoma.

Primary mucosal melanoma of the GI tract is a rare but aggressive malignancy, most often located in the anorectum but occasionally seen in the esophagus, stomach, small bowel, or colon. It differs substantially from cutaneous melanoma, in terms of epidemiology, pathogenesis, molecular profile, and therapeutic response. Differentiating primary lesions from metastatic melanoma is challenging. Surgery is the mainstay of treatment, though the extent of resection and the role of lymphadenectomy remain debated. Systemic therapies, such as ICIs and targeted agents, have shown only modest efficacy compared with their impact in cutaneous melanoma, therefore the prognosis remains poor. The current literature on primary GI melanoma is largely based on retrospective case series and single-case reports, which are subject to major limitations, including small sample sizes, variability in diagnostic criteria, and potential publication bias. Overcoming these limitations through collaborative multicenter studies and standardized reporting is essential to achieve earlier recognition, a deeper understanding of disease biology, and the refinement of therapeutic strategies aimed at improving survival outcomes in this challenging disease.

| 1. | Kahl AR, Gao X, Chioreso C, Goffredo P, Hassan I, Charlton ME, Lin C. Presentation, Management, and Prognosis of Primary Gastrointestinal Melanoma: A Population-Based Study. J Surg Res. 2021;260:46-55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Zhong L, Zhao Z, Zhang X. Genetic differences between primary and metastatic cancer: a pan-cancer whole-genome comparison study. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023;8:363. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Zheng Y, Cong C, Su C, Sun Y, Xing L. Epidemiology and survival outcomes of primary gastrointestinal melanoma: a SEER-based population study. Int J Clin Oncol. 2020;25:1951-1959. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Qiu S, Chen R, Yu Z, Shao S, Yuan H, Han T. The Development and Validation of a Nomogram for Predicting Cancer-Specific Survival and a Risk Stratification System for Patients with Primary Gastrointestinal Melanoma. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2023;34:850-858. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Bleicher J, Cohan JN, Huang LC, Peche W, Pickron TB, Scaife CL, Bowles TL, Hyngstrom JR, Asare EA. Trends in the management of anorectal melanoma: A multi-institutional retrospective study and review of the world literature. World J Gastroenterol. 2021;27:267-280. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Mellotte GS, Sabu D, O'Reilly M, McDermott R, O'Connor A, Ryan BM. The challenge of primary gastric melanoma: a systematic review. Melanoma Manag. 2020;7:MMT51. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Patel P, Boudreau C, Jessula S, Plourde M. Primary esophageal melanoma: a case report. Melanoma Manag. 2022;9:MMT63. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Badakhshi H, Wang ZM, Li RJ, Ismail M, Kaul D. Survival and Prognostic Nomogram for Primary Gastrointestinal Melanoma (PGIM): A Population-based Study. Anticancer Res. 2021;41:967-974. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Sun TT, Liu FG. The analysis about the metastases to Gastrointestinal tract: a literature review, 2000-2023. Front Oncol. 2025;15:1552932. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Bangolo A, Fwelo P, Sagireddy S, Shah H, Trivedi C, Bukasa-Kakamba J, Patel R, Bharane L, Randhawa MK, Nagesh VK, Dey S, Terefe H, Kaur G, Dinko N, Emiroglu FL, Mohamed A, Fallorina MA, Kosoy D, Waqar D, Shenoy A, Ahmed K, Nanavati A, Singh A, Willie A, Gonzalez DMC, Mukherjee D, Sajja J, Proverbs-Singh T, Elias S, Weissman S. Interaction between Age and Primary Site on Survival Outcomes in Primary GI Melanoma over the Past Decade. Med Sci (Basel). 2023;11:32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Shah NJ, Aloysius MM, Bhanat E, Gupta S, Aswath G, John S, Tang SJ, Goyal H. Epidemiology and outcomes of gastrointestinal mucosal melanomas: a national database analysis. BMC Gastroenterol. 2022;22:178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Mihajlovic M, Vlajkovic S, Jovanovic P, Stefanovic V. Primary mucosal melanomas: a comprehensive review. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2012;5:739-753. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Santeufemia DA, Palmieri G, Miolo G, Colombino M, Doro MG, Frogheri L, Paliogiannis P, Capobianco G, Madonia M, Cossu A, Lo Re G, Corona G. Current Trends in Mucosal Melanomas: An Overview. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15:1356. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Zhou R, Shi C, Tao W, Li J, Wu J, Han Y, Yang G, Gu Z, Xu S, Wang Y, Wang L, Wang Y, Zhou G, Zhang C, Zhang Z, Sun S. Analysis of Mucosal Melanoma Whole-Genome Landscapes Reveals Clinically Relevant Genomic Aberrations. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25:3548-3560. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Lasota J, Kowalik A, Felisiak-Golabek A, Zięba S, Waloszczyk P, Masiuk M, Wejman J, Szumilo J, Miettinen M. Primary malignant melanoma of esophagus: clinicopathologic characterization of 20 cases including molecular genetic profiling of 15 tumors. Mod Pathol. 2019;32:957-966. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Nagarajan P, Piao J, Ning J, Noordenbos LE, Curry JL, Torres-Cabala CA, Diwan AH, Ivan D, Aung PP, Ross MI, Royal RE, Wargo JA, Wang WL, Samdani R, Lazar AJ, Rashid A, Davies MA, Prieto VG, Gershenwald JE, Tetzlaff MT. Prognostic model for patient survival in primary anorectal mucosal melanoma: stage at presentation determines relevance of histopathologic features. Mod Pathol. 2020;33:496-513. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Taskin OC, Sari SO, Yilmaz I, Hurdogan O, Keskin M, Buyukbabani N, Gulluoglu M. BRAF, NRAS, KIT, TERT, GNAQ/GNA11 Mutation Profile and Histomorphological Analysis of Anorectal Melanomas: A Clinicopathologic Study. Turk Patoloji Derg. 2023;39:23-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Alvarez J, Smith JJ. Anorectal mucosal melanoma. Semin Colon Rectal Surg. 2023;34:100990. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Yang HM, Hsiao SJ, Schaeffer DF, Lai C, Remotti HE, Horst D, Mansukhani MM, Horst BA. Identification of recurrent mutational events in anorectal melanoma. Mod Pathol. 2017;30:286-296. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Nagtegaal ID, Odze RD, Klimstra D, Paradis V, Rugge M, Schirmacher P, Washington KM, Carneiro F, Cree IA; WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board. The 2019 WHO classification of tumours of the digestive system. Histopathology. 2020;76:182-188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2554] [Cited by in RCA: 2764] [Article Influence: 460.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 21. | Ferreira I, Arends MJ, van der Weyden L, Adams DJ, Brenn T. Primary de-differentiated, trans-differentiated and undifferentiated melanomas: overview of the clinicopathological, immunohistochemical and molecular spectrum. Histopathology. 2022;80:135-149. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Liu HG, Kong MX, Yao Q, Wang SY, Shibata R, Yee H, Martiniuk F, Wang BY. Expression of Sox10 and c-kit in sinonasal mucosal melanomas arising in the Chinese population. Head Neck Pathol. 2012;6:401-408. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Newell F, Kong Y, Wilmott JS, Johansson PA, Ferguson PM, Cui C, Li Z, Kazakoff SH, Burke H, Dodds TJ, Patch AM, Nones K, Tembe V, Shang P, van der Weyden L, Wong K, Holmes O, Lo S, Leonard C, Wood S, Xu Q, Rawson RV, Mukhopadhyay P, Dummer R, Levesque MP, Jönsson G, Wang X, Yeh I, Wu H, Joseph N, Bastian BC, Long GV, Spillane AJ, Shannon KF, Thompson JF, Saw RPM, Adams DJ, Si L, Pearson JV, Hayward NK, Waddell N, Mann GJ, Guo J, Scolyer RA. Whole-genome landscape of mucosal melanoma reveals diverse drivers and therapeutic targets. Nat Commun. 2019;10:3163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 191] [Cited by in RCA: 228] [Article Influence: 32.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, Byrd DR. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. Germany: Springer, 2017. |

| 25. | Zeng J, Zhu L, Zhou G, Pan F, Yang Y. Prognostic models based on lymph node density for primary gastrointestinal melanoma: a SEER population-based analysis. BMJ Open. 2023;13:e073335. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | La Selva D, Kozarek RA, Dorer RK, Rocha FG, Gluck M. Primary and metastatic melanoma of the GI tract: clinical presentation, endoscopic findings, and patient outcomes. Surg Endosc. 2020;34:4456-4462. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Kosmas K, Vamvakaris I, Psychogiou E, Klapsinou E, Riga D. Primary Gastric Malignant Melanoma. Cureus. 2020;12:e11792. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Schizas D, Tomara N, Katsaros I, Sakellariou S, Machairas N, Paspala A, Tsilimigras DI, Papanikolaou IS, Mantas D. Primary gastric melanoma in adult population: a systematic review of the literature. ANZ J Surg. 2021;91:269-275. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Patti R, Cacciatori M, Guercio G, Territo V, Di Vita G. Intestinal melanoma: A broad spectrum of clinical presentation. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2012;3:395-398. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Yang L, Yang F. Case Report: Esophageal malignant melanoma with lung adenocarcinoma: a rare case of dual primary cancers. Front Oncol. 2025;15:1546806. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Sinagra E, Sciumè C. Ileal Melanoma, A Rare Cause of Small Bowel Obstruction: Report of a Case, and Short Literature Review. Curr Radiopharm. 2020;13:56-62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Wang S, Sun S, Liu X, Ge N, Wang G, Guo J, Liu W, Hu J. Endoscopic diagnosis of gastrointestinal melanoma. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2020;55:330-337. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Fernández Noël S, García Picazo A, Gutiérrez de Prado J, Otero Torrón B, Jara Casas D, Garfia Castillo C, Caso Maestro Ó, Jiménez Romero C. Capsule endoscopy diagnosis of gastrointestinal melanoma. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2023;115:750-751. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Yi NH, Lee SH, Lee SH, Kim JH, Jee SR, Seol SY. Primary malignant melanoma without melanosis of the colon. Intest Res. 2019;17:561-564. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Malaguarnera G, Madeddu R, Catania VE, Bertino G, Morelli L, Perrotta RE, Drago F, Malaguarnera M, Latteri S. Anorectal mucosal melanoma. Oncotarget. 2018;9:8785-8800. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Gershenwald JE, Scolyer RA, Hess KR, Sondak VK, Long GV, Ross MI, Lazar AJ, Faries MB, Kirkwood JM, McArthur GA, Haydu LE, Eggermont AMM, Flaherty KT, Balch CM, Thompson JF; for members of the American Joint Committee on Cancer Melanoma Expert Panel and the International Melanoma Database and Discovery Platform. Melanoma staging: Evidence-based changes in the American Joint Committee on Cancer eighth edition cancer staging manual. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67:472-492. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1294] [Cited by in RCA: 1706] [Article Influence: 189.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Huang W, Qiu Y, Xiao X, Li L, Yang Q, Gao J, Kang L. Malignant melanoma of gastrointestinal tract on (18)F-FDG PET/CT: three case reports. Am J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2023;13:279-288. [PubMed] |

| 38. | Agrawal A, Pantvaidya G, Murthy V, Prabhash K, Bal M, Purandare N, Shah S, Rangarajan V. Positron Emission Tomography in Mucosal Melanomas of Head and Neck: Results from a South Asian Tertiary Cancer Care Center. World J Nucl Med. 2017;16:197-201. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Zamani-Siahkali N, Mirshahvalad SA, Pirich C, Beheshti M. Diagnostic Performance of [(18)F]F-FDG Positron Emission Tomography (PET) in Non-Ophthalmic Malignant Melanoma: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of More Than 10,000 Melanoma Patients. Cancers (Basel). 2024;16:215. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Tang Y, Jiang M, Hu X, Chen C, Huang Q. Difficulties encountered in the diagnosis of primary esophageal malignant melanoma by 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography: a case report. Ann Palliat Med. 2021;10:4975-4981. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Tan XL, Le A, Tang H, Brown M, Scherrer E, Han J, Jiang R, Diede SJ, Shui IM. Burden and Risk Factors of Brain Metastases in Melanoma: A Systematic Literature Review. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14:6108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Kohoutova D, Worku D, Aziz H, Teare J, Weir J, Larkin J. Malignant Melanoma of the Gastrointestinal Tract: Symptoms, Diagnosis, and Current Treatment Options. Cells. 2021;10:327. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Al-Haseni A, Vrable A, Qureshi MM, Mathews S, Pollock S, Truong MT, Sahni D. Survival outcomes of mucosal melanoma in the USA. Future Oncol. 2019;15:3977-3986. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Spadafora M, Santandrea G, Lai M, Borsari S, Kaleci S, Banzi C, Mandato VD, Pellacani G, Piana S, Longo C. Clinical Review of Mucosal Melanoma: The 11-Year Experience of a Referral Center. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2023;13:e2023057. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Adileh M, Yuval JB, Huang S, Shoushtari AN, Quezada-Diaz F, Pappou EP, Weiser MR, Garcia-Aguilar J, Smith JJ, Paty PB, Nash GM. Anorectal Mucosal Melanoma in the Era of Immune Checkpoint Inhibition: Should We Change Our Surgical Management Paradigm? Dis Colon Rectum. 2021;64:555-562. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Sergi MC, Filoni E, Triggiano G, Cazzato G, Internò V, Porta C, Tucci M. Mucosal Melanoma: Epidemiology, Clinical Features, and Treatment. Curr Oncol Rep. 2023;25:1247-1258. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Cazzato G, Cascardi E, Colagrande A, Lettini T, Resta L, Bizzoca C, Arezzo F, Loizzi V, Dellino M, Cormio G, Casatta N, Lupo C, Scillimati A, Scacco S, Parente P, Lospalluti L, Ingravallo G. The Thousand Faces of Malignant Melanoma: A Systematic Review of the Primary Malignant Melanoma of the Esophagus. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14:3725. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 48. | Eng JY, Tahkin S, Yaacob H, Yunus NH, Sidek ASWM, Wong MP. Multiple gastrointestinal melanoma causing small bowel intussusception. Ann Coloproctol. 2023;39:85-88. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Khalid U, Saleem T, Imam AM, Khan MR. Pathogenesis, diagnosis and management of primary melanoma of the colon. World J Surg Oncol. 2011;9:14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Xie J, Dai G, Wu Y. Primary colonic melanoma: a rare entity. World J Surg Oncol. 2022;20:256. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Petrov B, Petrov PM, Alexov SA, Hadzhiev G, Vukova T. Laparoscopic Treatment of Primary Colon Melanoma: A Case Study. Am J Case Rep. 2023;24:e938914. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Carcoforo P, Raiji MT, Palini GM, Pedriali M, Maestroni U, Soliani G, Detroia A, Zanzi MV, Manna AL, Crompton JG, Langan RC, Stojadinovic A, Avital I. Primary anorectal melanoma: an update. J Cancer. 2012;3:449-453. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Zhang S, Gao F, Wan D. Abdominoperineal resection or local excision? a survival analysis of anorectal malignant melanoma with surgical management. Melanoma Res. 2010;20:338-341. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Paolino G, Podo Brunetti A, De Rosa C, Cantisani C, Rongioletti F, Carugno A, Zerbinati N, Valenti M, Mascagni D, Tosti G, Mercuri SR, Pampena R. Anorectal melanoma: systematic review of the current literature of an aggressive type of melanoma. Melanoma Res. 2024;34:487-496. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Nilsson PJ, Ragnarsson-Olding BK. Importance of clear resection margins in anorectal malignant melanoma. Br J Surg. 2010;97:98-103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Mistrangelo M, Picciotto F, Quaglino P, Marchese V, Lesca A, Senetta R, Leone N, Astrua C, Roccuzzo G, Orlando G, Bellò M, Morino M. Feasibility and impact of sentinel lymph node biopsy in patients affected by ano-rectal melanoma. Tech Coloproctol. 2025;29:38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Damin DC, Rosito MA, Spiro BL. Long-term survival data on sentinel lymph node biopsy in anorectal melanoma. Tech Coloproctol. 2010;14:367-368. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Zhang J, Tian H, Mao L, Si L. Treatment of acral and mucosal melanoma: Current and emerging targeted therapies. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2024;193:104221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Boutros A, Croce E, Ferrari M, Gili R, Massaro G, Marconcini R, Arecco L, Tanda ET, Spagnolo F. The treatment of advanced melanoma: Current approaches and new challenges. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2024;196:104276. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Lian B, Guo J. Therapeutic Approaches to Mucosal Melanoma. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2025;45:e4733858. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Lian B, Li Z, Wu N, Li M, Chen X, Zheng H, Gao M, Wang D, Sheng X, Tian H, Si L, Chi Z, Wang X, Lai Y, Sun T, Zhang Q, Kong Y, Long GV, Guo J, Cui C. Phase II clinical trial of neoadjuvant anti-PD-1 (toripalimab) combined with axitinib in resectable mucosal melanoma. Ann Oncol. 2024;35:211-220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Smart AC, Giobbie-Hurder A, Desai V, Xing JL, Lukens JN, Taunk NK, Sullivan RJ, Mooradian MJ, Hsu CC, Buchbinder EI, Schoenfeld JD. Multicenter Evaluation of Radiation and Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy in Mucosal Melanoma and Review of Recent Literature. Adv Radiat Oncol. 2024;9:101310. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Tyrrell H, Payne M. Combatting mucosal melanoma: recent advances and future perspectives. Melanoma Manag. 2018;5:MMT11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Xu Y, Chen Y. Editorial: Multidisciplinary treatment and precision medicine for acral and mucosal melanoma. Front Oncol. 2024;14:1429030. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Teo AYT, Yau CE, Low CE, Pereira JV, Ng JYX, Soong TK, Lo JYT, Yang VS. Effectiveness of immune checkpoint inhibitors and other treatment modalities in patients with advanced mucosal melanomas: a systematic review and individual patient data meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine. 2024;77:102870. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Nakamura Y, Mori T. Adjuvant therapy for mucosal melanoma in the era of immune checkpoint inhibitors. Chin Clin Oncol. 2024;13:13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Mao L, Qi Z, Zhang L, Guo J, Si L. Immunotherapy in Acral and Mucosal Melanoma: Current Status and Future Directions. Front Immunol. 2021;12:680407. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 22.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Vos JL, Traets JJ, Qiao X, Seignette IM, Peters D, Wouters MW, Hooijberg E, Broeks A, van der Wal JE, Karakullukcu MB, Klop WMC, Navran A, van Beurden M, Brouwer OR, Morris LG, van Poelgeest MI, Kapiteijn E, Haanen JB, Blank CU, Zuur CL. Diversity of the immune microenvironment and response to checkpoint inhibitor immunotherapy in mucosal melanoma. JCI Insight. 2024;9:e179982. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Dai J, Bai X, Gao X, Tang L, Chen Y, Sun L, Wei X, Li C, Qi Z, Kong Y, Cui C, Chi Z, Sheng X, Xu Z, Lian B, Li S, Yan X, Tang B, Zhou L, Wang X, Xia X, Guo J, Mao L, Si L. Molecular underpinnings of exceptional response in primary malignant melanoma of the esophagus to anti-PD-1 monotherapy. J Immunother Cancer. 2023;11:e005937. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Broit N, Johansson PA, Rodgers CB, Walpole ST, Newell F, Hayward NK, Pritchard AL. Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review of the Genomics of Mucosal Melanoma. Mol Cancer Res. 2021;19:991-1004. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Woodman SE, Davies MA. Targeting KIT in melanoma: a paradigm of molecular medicine and targeted therapeutics. Biochem Pharmacol. 2010;80:568-574. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Steeb T, Wessely A, Petzold A, Kohl C, Erdmann M, Berking C, Heppt MV. c-Kit inhibitors for unresectable or metastatic mucosal, acral or chronically sun-damaged melanoma: a systematic review and one-arm meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer. 2021;157:348-357. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Pham DDM, Guhan S, Tsao H. KIT and Melanoma: Biological Insights and Clinical Implications. Yonsei Med J. 2020;61:562-571. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Hodi FS, Corless CL, Giobbie-Hurder A, Fletcher JA, Zhu M, Marino-Enriquez A, Friedlander P, Gonzalez R, Weber JS, Gajewski TF, O'Day SJ, Kim KB, Lawrence D, Flaherty KT, Luke JJ, Collichio FA, Ernstoff MS, Heinrich MC, Beadling C, Zukotynski KA, Yap JT, Van den Abbeele AD, Demetri GD, Fisher DE. Imatinib for melanomas harboring mutationally activated or amplified KIT arising on mucosal, acral, and chronically sun-damaged skin. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3182-3190. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 408] [Cited by in RCA: 440] [Article Influence: 33.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Del Vecchio M, Di Guardo L, Ascierto PA, Grimaldi AM, Sileni VC, Pigozzo J, Ferraresi V, Nuzzo C, Rinaldi G, Testori A, Ferrucci PF, Marchetti P, De Galitiis F, Queirolo P, Tornari E, Marconcini R, Calabrò L, Maio M. Efficacy and safety of ipilimumab 3mg/kg in patients with pretreated, metastatic, mucosal melanoma. Eur J Cancer. 2014;50:121-127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | D'Angelo SP, Larkin J, Sosman JA, Lebbé C, Brady B, Neyns B, Schmidt H, Hassel JC, Hodi FS, Lorigan P, Savage KJ, Miller WH Jr, Mohr P, Marquez-Rodas I, Charles J, Kaatz M, Sznol M, Weber JS, Shoushtari AN, Ruisi M, Jiang J, Wolchok JD. Efficacy and Safety of Nivolumab Alone or in Combination With Ipilimumab in Patients With Mucosal Melanoma: A Pooled Analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:226-235. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 322] [Cited by in RCA: 467] [Article Influence: 46.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Postow MA, Luke JJ, Bluth MJ, Ramaiya N, Panageas KS, Lawrence DP, Ibrahim N, Flaherty KT, Sullivan RJ, Ott PA, Callahan MK, Harding JJ, D'Angelo SP, Dickson MA, Schwartz GK, Chapman PB, Gnjatic S, Wolchok JD, Hodi FS, Carvajal RD. Ipilimumab for patients with advanced mucosal melanoma. Oncologist. 2013;18:726-732. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Mignard C, Deschamps Huvier A, Gillibert A, Duval Modeste AB, Dutriaux C, Khammari A, Avril MF, Kramkimel N, Mortier L, Marcant P, Lesimple T, Gaudy-Marqueste C, Lesage C, Machet L, Aubin F, Meyer N, Beneton N, Jeudy G, Montaudié H, Arnault JP, Visseaux L, Trabelsi S, Amini-Adle M, Maubec E, Le Corre Y, Lipsker D, Wierzbicka-Hainaut E, Litrowski N, Stefan A, Brunet-Possenti F, Leccia MT, Joly P. Efficacy of Immunotherapy in Patients with Metastatic Mucosal or Uveal Melanoma. J Oncol. 2018;2018:1908065. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Wolchok JD, Chiarion-Sileni V, Gonzalez R, Grob JJ, Rutkowski P, Lao CD, Cowey CL, Schadendorf D, Wagstaff J, Dummer R, Ferrucci PF, Smylie M, Butler MO, Hill A, Márquez-Rodas I, Haanen JBAG, Guidoboni M, Maio M, Schöffski P, Carlino MS, Lebbé C, McArthur G, Ascierto PA, Daniels GA, Long GV, Bas T, Ritchings C, Larkin J, Hodi FS. Long-Term Outcomes With Nivolumab Plus Ipilimumab or Nivolumab Alone Versus Ipilimumab in Patients With Advanced Melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40:127-137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 864] [Article Influence: 216.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Bai X, Mao LL, Chi ZH, Sheng XN, Cui CL, Kong Y, Dai J, Wang X, Li SM, Tang BX, Lian B, Zhou L, Yan XQ, Guo J, Si L. BRAF inhibitors: efficacious and tolerable in BRAF-mutant acral and mucosal melanoma. Neoplasma. 2017;64:626-632. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Tawbi HA, Schadendorf D, Lipson EJ, Ascierto PA, Matamala L, Castillo Gutiérrez E, Rutkowski P, Gogas HJ, Lao CD, De Menezes JJ, Dalle S, Arance A, Grob JJ, Srivastava S, Abaskharoun M, Hamilton M, Keidel S, Simonsen KL, Sobiesk AM, Li B, Hodi FS, Long GV; RELATIVITY-047 Investigators. Relatlimab and Nivolumab versus Nivolumab in Untreated Advanced Melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2022;386:24-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 346] [Cited by in RCA: 1355] [Article Influence: 338.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/