Published online Feb 28, 2026. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v32.i8.114268

Revised: November 7, 2025

Accepted: January 4, 2026

Published online: February 28, 2026

Processing time: 141 Days and 18.5 Hours

Endoscopic treatment is the primary therapy for type I gastric neuroendocrine tumors (G-NETs), but it may not address the underlying pathogenesis, increasing the risk of progression.

To investigate the effectiveness of endoscopic treatment and identify progression risk factors.

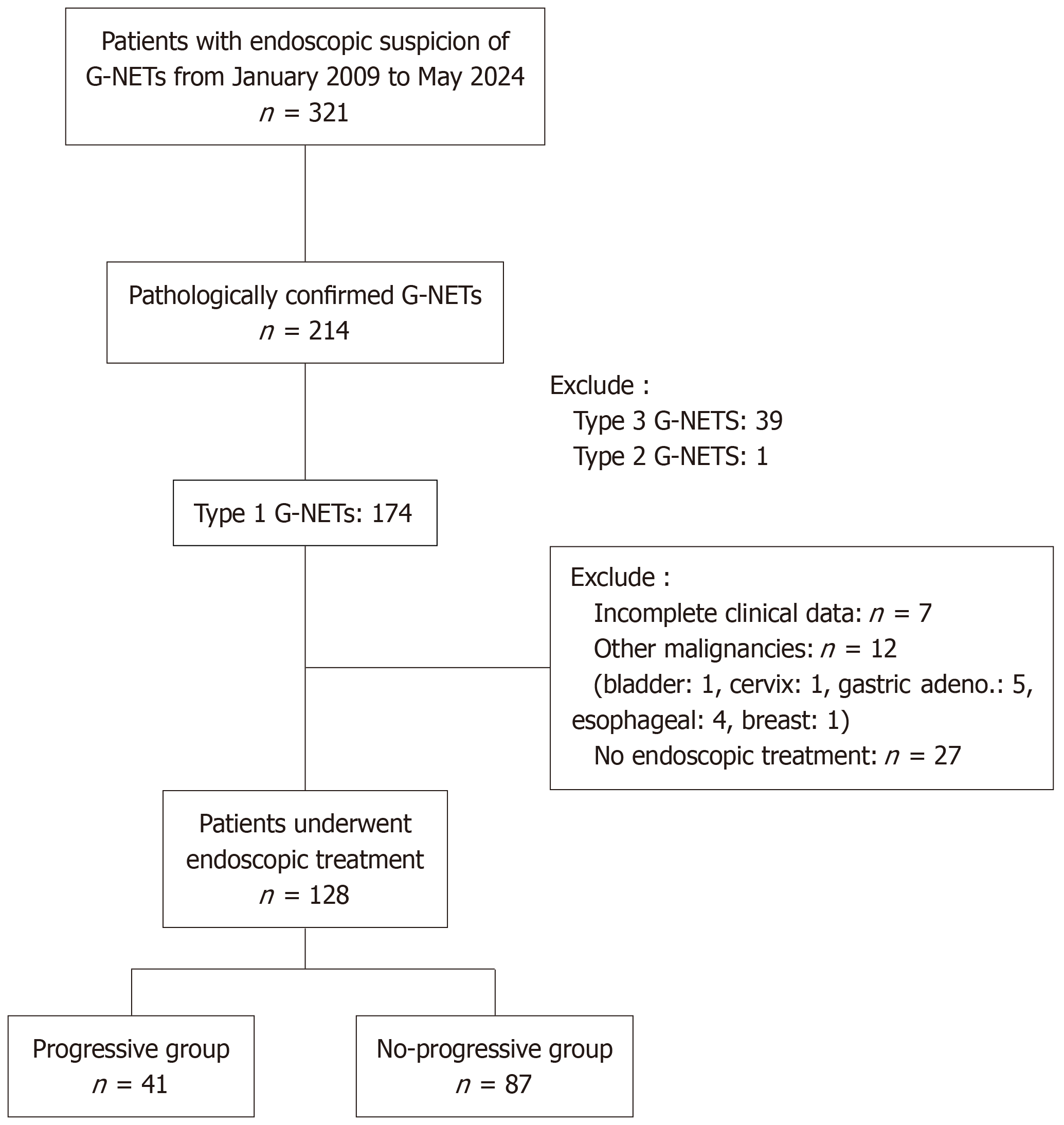

This retrospective study involved 128 patients with type I G-NETs treated between January 2009 and May 2024. The patients were categorized into non-progressive (n = 87) and progressive (n = 41) groups. Baseline characteristics, treatment details, and follow-up data were analyzed using univariate and multi

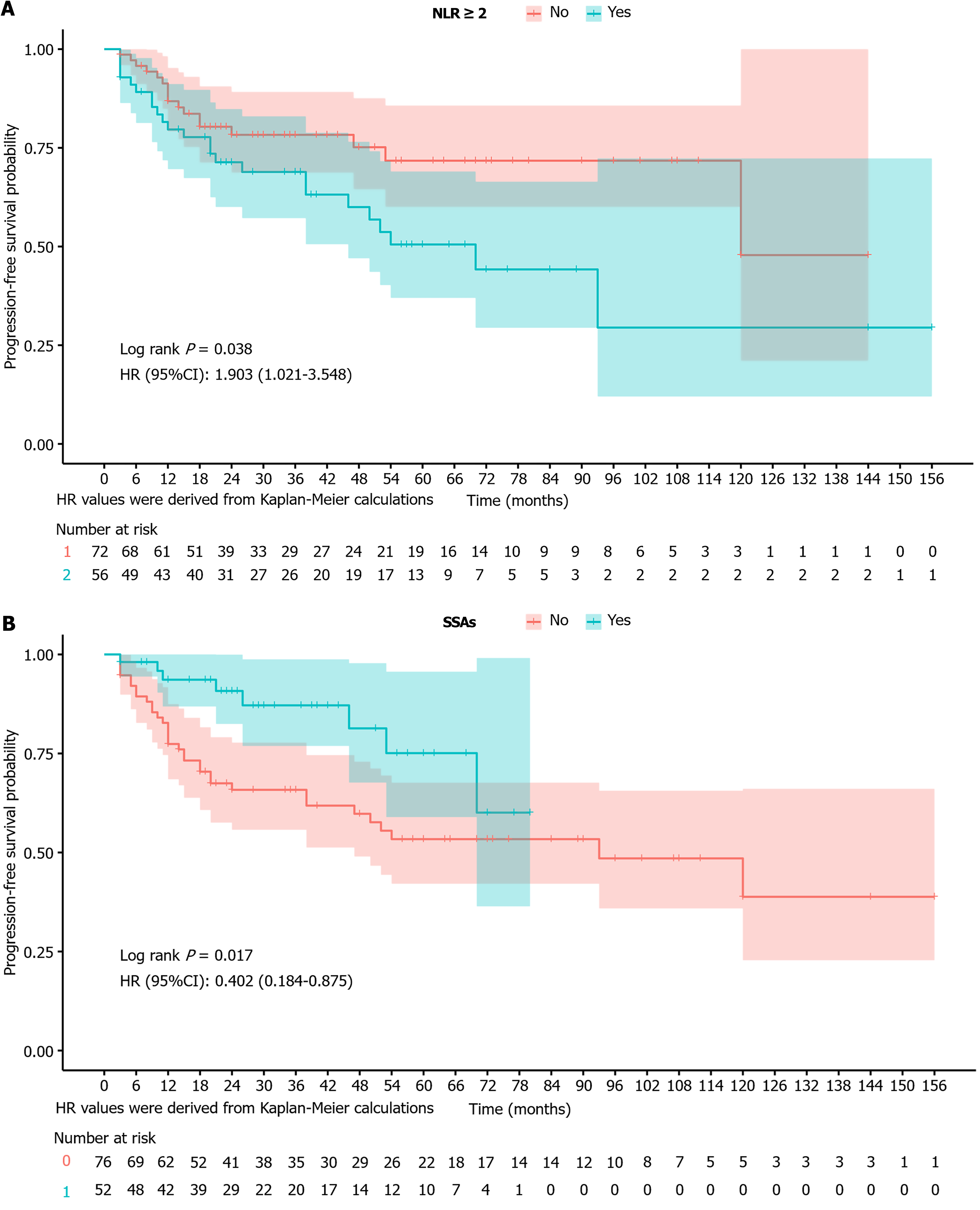

The baseline characteristics analysis showed no significant differences between the groups. The median follow-up time was 25.5 months (14.00-58.50 months). The univariate and multivariate analyses confirmed that endoscopic treatment combined with adjuvant somatostatin analogs (SSAs) was associated with a lower risk of progression (hazard ratio = 0.38, 95% confidence interval: 0.17-0.90, P = 0.027), whereas a neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) of ≥ 2 indicated a higher risk (hazard ratio = 2.14, 95% confidence interval: 1.08-4.26, P = 0.030). Kaplan-Meier analysis confirmed NLR ≥ 2 and adjuvant SSA use as independent prognostic variables.

Combining endoscopic treatment with SSAs is effective for managing type I G-NETs. SSAs and NLR were identified as independent prognostic factors, highlighting their potential to reduce recurrence risk and improve outcomes.

Core Tip: Endoscopic treatment is the standard therapy for type I gastric neuroendocrine tumors, but it may not address underlying disease mechanisms. In this retrospective study of 128 patients, 41 experienced progression. Multivariate Cox regression identified adjuvant somatostatin analog use as a protective factor (hazard ratio = 0.38, 95% confidence interval: 0.17-0.90, P = 0.027) and neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio ≥ 2 as a risk factor (hazard ratio = 2.14, 95% confidence interval: 1.08-4.26, P = 0.030). Kaplan-Meier analysis confirmed both as independent prognostic variables. These findings suggest that combining endoscopic therapy with somatostatin analogues improves outcomes. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio may serve as a simple marker to guide risk stratification.

- Citation: Yang ZL, Wang HK, Liu Y, Dou LZ, Zhang YM, Ng HI, He S, Chi YB, Wang GQ. Progression after endoscopic treatment for type I gastric neuroendocrine tumors: A single-center retrospective study. World J Gastroenterol 2026; 32(8): 114268

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v32/i8/114268.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v32.i8.114268

Gastric neuroendocrine tumors (G-NETs) are a group of highly heterogeneous tumors originating from enterochromaffin-like (ECL) cells in the gastric mucosa. According to the World Health Organization classification, G-NETs are categorized into three types. Type I G-NETs are predominantly associated with autoimmune gastritis and are frequently multifocal. Type II G-NETs are linked to gastrinomas and are often multifocal. Type III G-NETs are usually sporadic and present as solitary lesions[1,2]. With advances in endoscopic techniques, G-NET incidence rates have increased. A study reported a 6.4-fold increase in the age-adjusted incidence of neuroendocrine tumors, from 1.09 (1973) to 6.98 (2012) per 100000 persons[3]. The age-standardized incidence rate for neuroendocrine neoplasms in China was 1.14 per 100000 in 2017, with gastric neuroendocrine neoplasms (G-NENs) accounting for 19.7% of all neuroendocrine neoplasms[4].

G-NET pathogenesis is closely associated with hypergastrinemia. Under long-term stimulation by elevated gastrin levels, ECL cells may exhibit hyperplasia and dysplasia, resulting in neoplastic transformation, often presenting as multiple lesions[5-8]. Multiple G-NETs typically represent a major proportion of type I cases[9]. Although the overall prognosis of multiple G-NETs is relatively favorable, the risk of metastasis still exists, requiring treatment[10-12].

G-NETs are treated using endoscopic, surgical, and pharmacological therapies[13,14]. Endoscopic therapy is primarily indicated for tumors not invading the muscularis propria[15]. Endoscopic treatment for G-NETs included endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) and endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD). Current clinical studies have not yet clearly defined the specific indications for ESD and EMR in the treatment of G-NETs. A meta-analysis showed that ESD and EMR techniques demonstrated similar outcomes in terms of R0 resection and en bloc resection (97.4% vs 98.7%, and 92.3% vs 96.3%, respectively)[15]. Surgical treatment should be considered if the tumor invades the muscularis propria[16]. The relevant guidelines clearly state that somatostatin therapy should be initiated when the tumor is not amenable to surgical or endoscopic resection[16]. Notably, for large preoperative lesions that cannot be endoscopically resected, neoadjuvant treatment with somatostatin analogs (SSAs) should be considered. Studies have shown that long-acting SSAs can exhibit significant therapeutic effects in the treatment of metastatic NETs. In the treatment of multiple G-NETs, the response rate to long-acting SSAs can reach up to 84.5%; however, there is a notable recurrence rate following treatment discontinuation[17].

Patients with type I G-NETs are stratified by endoscopic morphology and histopathological features, and SSAs can be administered perioperatively. Available evidence is limited to data from cohorts of patients treated with either endoscopic resection or SSAs alone, and the efficacy of this combined strategy remains unexplored. Studies have indicated that type I G-NETs have a high recurrence rate, ranging from 2.4% to 63.6% after endoscopic treatment alone[18-21]. To address this knowledge gap, we conducted a single-center, retrospective cohort study of patients with type I G-NETs who underwent endoscopic resection, irrespective of whether adjuvant SSA therapy was subsequently introduced. We aimed to analyze the effectiveness of endoscopic treatment and SSAs as adjuvant therapy and identify the progressive risk factors of G-NETs following endoscopic treatment, thereby generating strong evidence to improve contemporary management algorithms.

This single-center, retrospective study involved 128 consecutive patients diagnosed with type I G-NETs who were treated at the Cancer Hospital of the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences between January 2009 and May 2024. Type I G-NETs were diagnosed by clinicians based on endoscopic findings, pathology, and background mucosal changes. Patients with poorly differentiated tumor morphology, other cancer, other severe chronic diseases, multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN1), or incomplete clinical data were excluded (Figure 1). This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of National Cancer Center/Cancer Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College in accordance with the ethical standards outlined in the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its subsequent amendments. As the study involved the analysis of pre-existing, anonymized data, informed consent was not required.

All participants underwent upper gastrointestinal endoscopy to assess the lesions’ size, tumor number, morphology, and location, as well as the presence and severity of atrophic gastritis. Endoscopic ultrasonography was used to determine the depth of tumor invasion. The presence of lymph node or distant metastasis was assessed preoperatively using computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, or positron emission tomography/computed tomography. Functional imaging examinations, including somatostatin receptor scintigraphy, were performed when necessary. The following clinical data were extracted from medical records: Basic demographic characteristics, physical measurements, laboratory test results, endoscopic characteristics, histopathological features, treatment-related details (including endoscopic treatment methods and postoperative adjuvant therapy), genetic sequencing, and follow-up outcomes.

Grading of G-NETs was performed according to the 2019 World Health Organization Classification of Tumours of the Digestive System, Fifth Edition. Neuroendocrine tumors were graded based on mitotic count per 10 HPFs and/or the Ki-67 index from a 500-cell hotspot. Grades were defined as G1 (< 2 mitoses, Ki-67 ≤ 2%), G2 (2-20 mitoses, Ki-67 3%-20%), or G3 (> 20 mitoses, Ki-67 > 20%)[2].

The treatment strategy for G-NETs was formulated based on a comprehensive assessment of histological grading, size, and tumor number, invasion depth, lymph node or distant metastasis. Endoscopic treatment (EMR or ESD) was performed for tumors with mucosal/submucosal involvement and without nodal or distant metastases. For type I G-NETs, before or after endoscopic treatment, the decision to administer SSA therapy (20/30 mg octreotide acetate every 4 weeks) was based on a comprehensive assessment of tumor number, lymphovascular invasion, and grade. The SSA therapy was continued for ≥ 12 months unless disease progression or intolerance occurred. Endoscopic treatment was performed by experienced endoscopic surgeons (each having independently performed more than 500 upper gastrointestinal endoscopic procedures), and SSA treatment was administered by experienced specialists in neuroendocrine tumors.

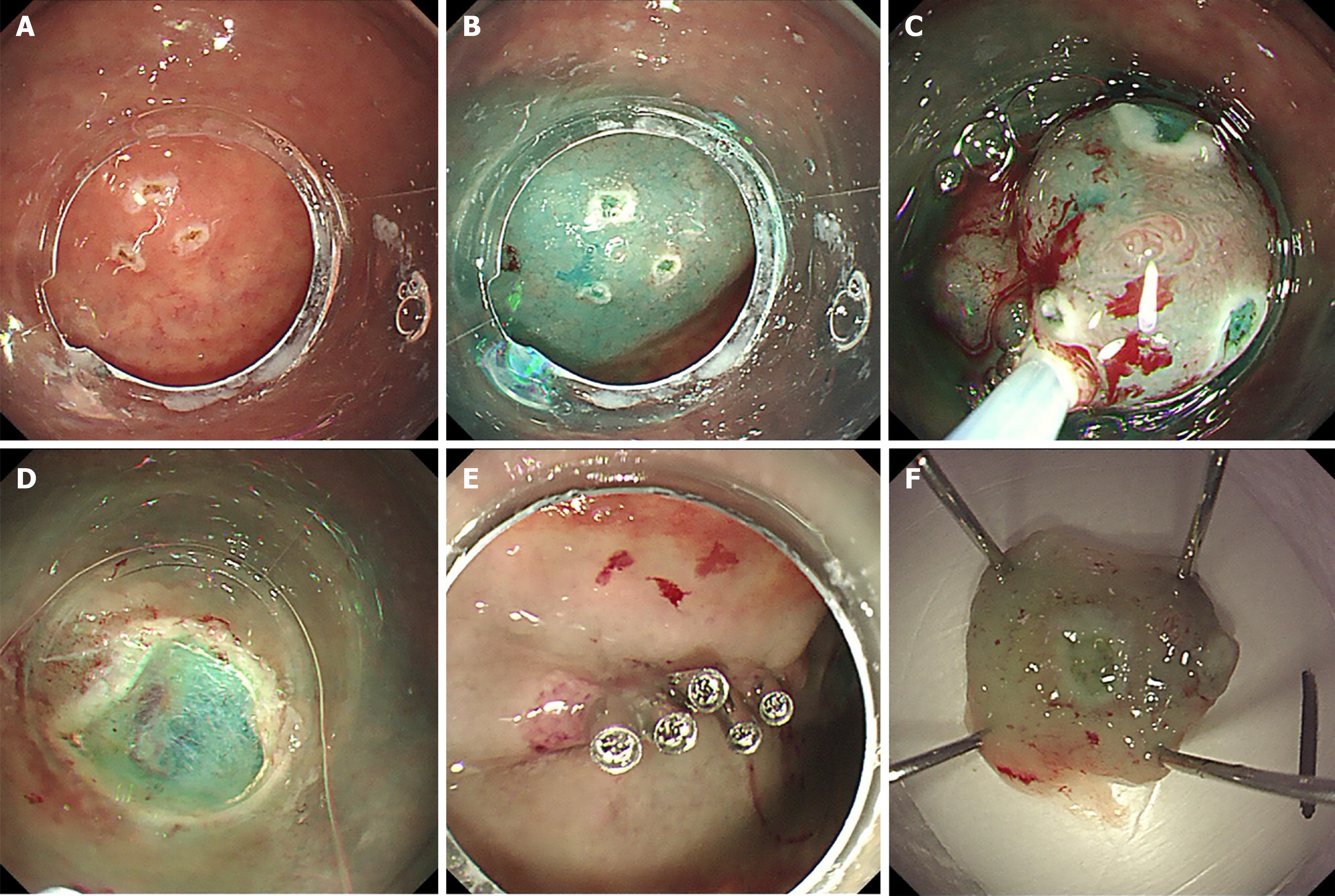

Circumferential marking around the lesion margin was performed using a dual knife (Figure 2A). Thereafter, a submucosal fluid cushion was created by injecting a diluted methylene blue solution to achieve adequate lift (Figure 2B). A standard monofilament snare was advanced to ensnare the target mucosa. While the snare was gradually tightened, a blended electrosurgical current was applied to transect the tissue, achieving en bloc resection (Figure 2C). Immediate hemostasis of the post-resection ulcer was achieved using targeted coagulation (Figure 2D-F).

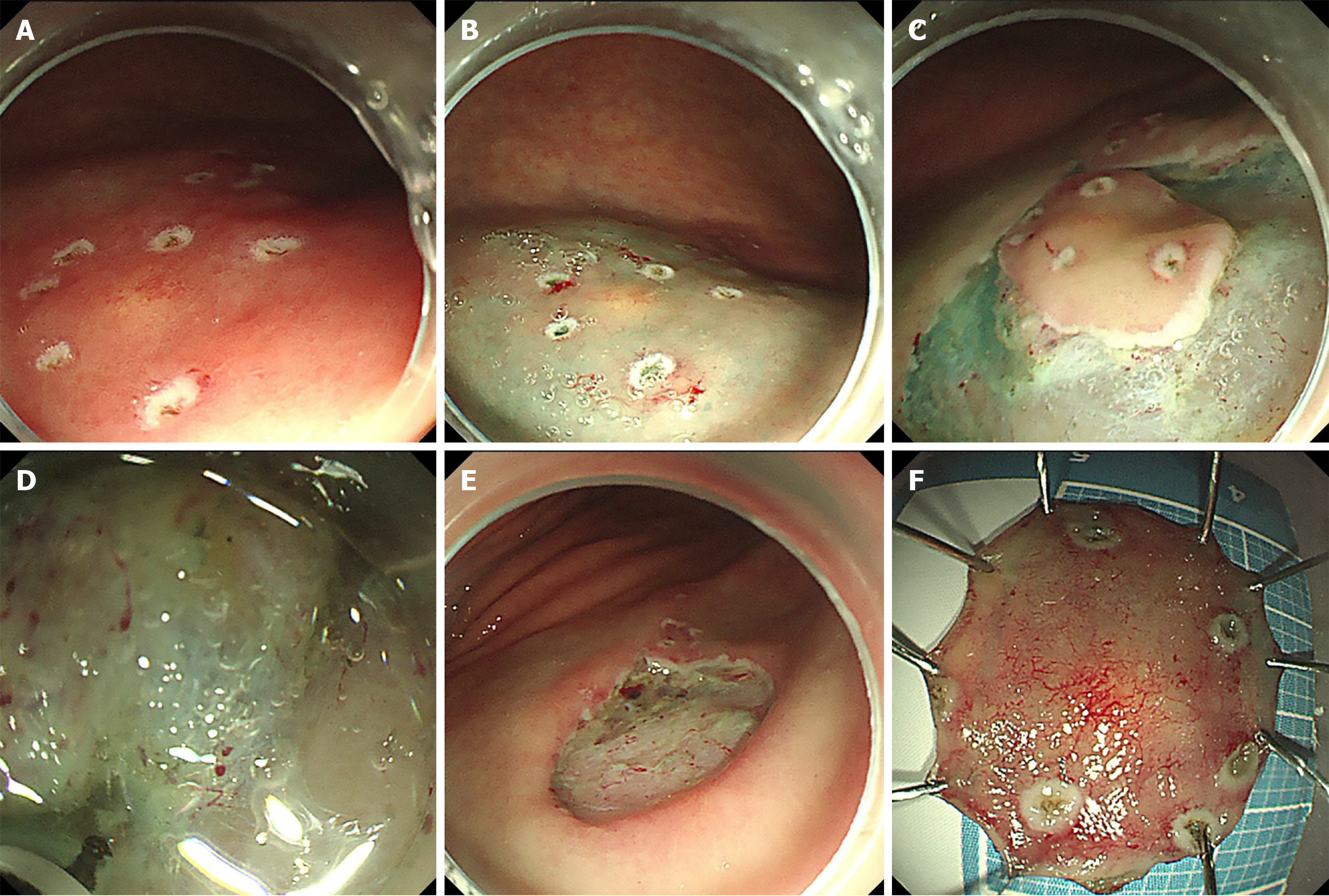

A precise circumferential delineation was marked using a dual knife (Figure 3A). Submucosal injection of methylene blue-saline solution resulted in sustained mucosal elevation (Figure 3B). A mucosal pre-incision was made along the outermost marking using a dual knife (Figure 3C). Systematic submucosal dissection was carried out under direct endoscopic visualization, with repeated submucosal injections administered until complete en bloc excision was achieved (Figure 3D). Following resection, meticulous hemostasis was accomplished using coagulation forceps, and the exposed muscularis propria was secured with endoclips (Figure 3E and F).

Treatment responses were defined as follows: Complete response as the disappearance of all lesions for > 4 weeks; partial response as a > 30% reduction in tumor size with partial symptom disappearance for > 4 weeks; and stable disease as a tumor size change within -30% to +20% with no new lesions. Disease progression was defined as endoscopic evidence of an increase in tumor size of > 20% after treatment or the appearance of new lesions histopathologically confirmed as neuroendocrine tumors.

Patient follow-up was conducted through regular outpatient assessments (including endoscopy, imaging, and blood tests), medical record (complications including bleeding, perforation, positive margin), and telephone follow-ups.

Bleeding: Refers to hemorrhage occurring after endoscopic treatment. It is generally defined as the presence of clinically significant hematochezia or the need for hemostatic intervention (such as repeat endoscopic hemostasis).

Perforation: A full-thickness defect in the gastrointestinal wall resulting from an endoscopic procedure.

En bloc resection: The lesion is removed as a single, intact piece during endoscopy, resulting in one complete specimen.

Positive horizontal (vertical) margin: A positive horizontal margin is defined by the presence of tumor cells at the lateral cut edge of the specimen upon microscopic examination, whereas tumor cell involvement at the deep basal cut edge is termed a positive vertical margin.

Follow-up duration was defined as the period from the date initial endoscopic treatment to the date of the last endoscopic examination. Follow-up ended on August 1, 2025. Gastroscopy was performed at 3 months, 6 months, and 12 months after endoscopic resection and repeated annually thereafter in both endoscopy group and endoscopy + SSAs group.

The primary outcome was the factors influencing tumor progression. All statistical analyses were performed using RStudio 2024.09.1 (Vienna, Austria). A formal sample size calculation was not performed as this retrospective study incorporated all consecutive eligible patients from our institution during the study period (2009-2024) to maximize data inclusion. Categorical variables are presented as n (%). Depending on their normality, as determined by the Shapiro-Wilk test, continuous variables are expressed as mean ± SD (normally distributed) or median (interquartile range) (non-normally distributed). Statistical analysis was performed with the Mann-Whitney U test or one-way ANOVA for continuous variables and with the Pearson χ2 or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables.

Univariate analysis was conducted using the Pearson χ2 test. Given the limited cohort size (n = 128), propensity score matching would have further reduced statistical power. Instead, we used multivariable adjustment to control for confounding, which is acceptable in small observational studies; all tests were two-sided. We employed least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) regression (α = 1) for variable selection, using 10-fold cross-validation and setting the number of λ values to 100. The λ value that minimized the mean squared error was used for variable screening. The following variables were selected by LASSO regression (when λ = 0.026091006791604) and can be used for subsequent modeling: Sex, lesion, max-diameter, SSAs, pathology, horizontal margin, lymphovascular invasion, perineural invasion, invasion depth, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) (Supplementary Figures 1-3). Using the restricted cubic spline models, we determined the NLR cut-off value as 2 and divided the groups into NLR ≥ 2 and NLR < 2 (Supplementary Figure 4 and Supplementary Table 1). Variables with P < 0.05 and those selected factors in previous studies were included in the subsequent multivariate Cox regression analysis. The level of significance was set at P < 0.05.

In this study, significant differences were observed between the endoscopy and endoscopy + SSAs groups in terms of the maximum tumor diameter, pathology grade, and progression. The significant discrepancy between the maximum lesion diameter and pathology grade suggests a historical treatment tendency of combining endoscopic therapy with SSAs for patients with G-NENs in clinical practice. There were no significant differences in the body mass index, sex, age, number of lesions, bleeding, perforation, status of horizontal and vertical margins, perineural invasion, invasion depth, lymphovascular invasion, NLR, or follow-up time between the groups (Table 1). During the entire follow-up period, a total of 41 disease progression events were documented. The predominant pattern of progression constituted metachronous gastric lesions (40 cases, 97.6%), with local recurrence representing a minor subset (1 case, 2.4%). The 3-year cumulative recurrence rates were significantly different between the two treatment cohorts: 32.89% in the endoscopy group vs 9.62% endoscopy + SSAs group (Table 2).

| Variables | Total | Endoscopy group | Endoscopy + SSAs group | Statistic | P value | SMD |

| Sex | χ2 = 0.10 | 0.748 | ||||

| Male | 52 (40.62) | 30 (39.47) | 22 (42.31) | 0.057 | ||

| Female | 76 (59.38) | 46 (60.53) | 30 (57.69) | -0.057 | ||

| Age | χ2 = 1.19 | 0.276 | ||||

| < 60 | 97 (75.78) | 55 (72.37) | 42 (80.77) | 0.213 | ||

| ≥ 60 | 31 (24.22) | 21 (27.63) | 10 (19.23) | -0.213 | ||

| BMI, median (Q1, Q3) | 23.94 (21.48, 26.42) | 23.86 (21.48, 26.35) | 23.94 (21.50, 27.47) | Z = -0.151 | 0.880 | 0.120 |

| Lesion | χ2 = 0.69 | 0.406 | ||||

| < 6 | 96 (75.00) | 59 (77.63) | 37 (71.15) | -0.143 | ||

| ≥ 6 | 32 (25.00) | 17 (22.37) | 15 (28.85) | 0.143 | ||

| Max-diameter | χ2 = 6.68 | 0.010 | ||||

| < 10 mm | 90 (70.31) | 60 (78.95) | 30 (57.69) | -0.430 | ||

| ≥ 10 mm | 38 (29.69) | 16 (21.05) | 22 (42.31) | 0.430 | ||

| Bleed | χ2 = 0.02 | 0.897 | ||||

| No | 124 (96.88) | 73 (96.05) | 51 (98.08) | 0.147 | ||

| Yes | 4 (3.12) | 3 (3.95) | 1 (1.92) | -0.147 | ||

| Perforation | χ2 = 0.11 | 0.738 | ||||

| No | 125 (97.66) | 75 (98.68) | 50 (96.15) | -0.132 | ||

| Yes | 3 (2.34) | 1 (1.32) | 2 (3.85) | 0.132 | ||

| Pathology | χ2 = 4.76 | 0.029 | ||||

| G1 | 105 (82.03) | 67 (88.16) | 38 (73.08) | -0.340 | ||

| G2 | 23 (17.97) | 9 (11.84) | 14 (26.92) | 0.340 | ||

| Horizontal margin | χ2 = 1.70 | 0.192 | ||||

| Negative | 117 (91.41) | 72 (94.74) | 45 (86.54) | -0.240 | ||

| Positive | 11 (8.59) | 4 (5.26) | 7 (13.46) | 0.240 | ||

| Vertical margin | χ2 = 2.32 | 0.127 | ||||

| Negative | 125 (97.66) | 76 (100.00) | 49 (94.23) | -0.247 | ||

| Positive | 3 (2.34) | 0 (0.00) | 3 (5.77) | 0.247 | ||

| Lymphovascular invasion | χ2 = 0.86 | 0.353 | ||||

| Negative | 120 (93.75) | 73 (96.05) | 47 (90.38) | -0.192 | ||

| Positive | 8 (6.25) | 3 (3.95) | 5 (9.62) | 0.192 | ||

| Perineural invasion | -2 | 1.000 | ||||

| Negative | 127 (99.22) | 75 (98.68) | 52 (100.00) | 0.150 | ||

| Positive | 1 (0.78) | 1 (1.32) | 0 (0.00) | -0.150 | ||

| Invasion depth | χ2 = 0.11 | 0.737 | ||||

| M | 49 (38.28) | 30 (39.47) | 19 (36.54) | -0.061 | ||

| SM | 79 (61.72) | 46 (60.53) | 33 (63.46) | 0.061 | ||

| NLR | χ2 = 0.01 | 0.928 | ||||

| < 2 | 72 (56.25) | 43 (56.58) | 29 (55.77) | -0.016 | ||

| ≥ 2 | 56 (43.75) | 33 (43.42) | 23 (44.23) | 0.016 | ||

| Progression | χ2 = 11.15 | < 0.001 | ||||

| No | 87 (67.97) | 43 (56.58) | 44 (84.62) | 0.777 | ||

| Yes | 41 (32.03) | 33 (43.42) | 8 (15.38) | -0.777 | ||

| Follow-up time, median (Q1, Q3) | 25.50 (14.00, 58.50) | 31.00 (13.50, 64.25) | 24.50 (18.25, 51.50) | Z = -0.741 | 0.461 | -0.491 |

| Recurrence rate | Endoscopy group | Endoscopy + SSAs group |

| 1 year | 22.37% | 5.77% |

| 2 years | 32.89% | 7.69% |

| 3 years | 32.89% | 9.62% |

| 4 years | 36.84% | 11.54% |

| 5 years | 40.79% | 13.46% |

| 10 years | 43.42% | 15.38% |

The 128 patients were divided into the non-progressive (n = 87) and progressive (n = 41) groups. The median follow-up time was 25.5 months (14.00-58.50 months). Analysis of baseline characteristics showed no significant differences between the groups in terms of body mass index, sex, age, number of lesions, maximum tumor diameter, bleeding, perforation, pathological grade, status of the horizontal and vertical margins, perineural invasion, invasion depth, and lymphova

| Variables | Total | Non-progressive group | Progressive group | Statistic | P value | SMD |

| Sex | χ2 = 1.05 | 0.306 | ||||

| Male | 52 (40.62) | 38 (43.68) | 14 (34.15) | -0.201 | ||

| Female | 76 (59.38) | 49 (56.32) | 27 (65.85) | 0.201 | ||

| Age | χ2 = 0.00 | 0.975 | ||||

| < 60 | 97 (75.78) | 66 (75.86) | 31 (75.61) | -0.006 | ||

| ≥ 60 | 31 (24.22) | 21 (24.14) | 10 (24.39) | 0.006 | ||

| BMI, median (Q1, Q3) | 23.94 (21.48, 26.42) | 24.22 (21.83, 26.97) | 22.86 (21.30, 26.31) | Z = -1.351 | 0.177 | -0.343 |

| Lesion | χ2 = 4.32 | 0.038 | ||||

| < 6 | 96 (75.00) | 70 (80.46) | 26 (63.41) | -0.354 | ||

| ≥ 6 | 32 (25.00) | 17 (19.54) | 15 (36.59) | 0.354 | ||

| Max-diameter | χ2 = 1.73 | 0.188 | ||||

| < 10 mm | 90 (70.31) | 58 (66.67) | 32 (78.05) | 0.275 | ||

| ≥ 10 mm | 38 (29.69) | 29 (33.33) | 9 (21.95) | -0.275 | ||

| SSAs | χ2 = 11.15 | < 0.001 | ||||

| No | 76 (59.38) | 43 (49.43) | 33 (80.49) | 0.784 | ||

| Yes | 52 (40.62) | 44 (50.57) | 8 (19.51) | -0.784 | ||

| Bleed | χ2 = 0.06 | 0.812 | ||||

| No | 124 (96.88) | 85 (97.70) | 39 (95.12) | -0.120 | ||

| Yes | 4 (3.12) | 2 (2.30) | 2 (4.88) | 0.120 | ||

| Perforation | - | 1.000 | ||||

| No | 125 (97.66) | 85 (97.70) | 40 (97.56) | -0.009 | ||

| Yes | 3 (2.34) | 2 (2.30) | 1 (2.44) | 0.009 | ||

| Pathology | χ2 = 0.03 | 0.856 | ||||

| G1 | 105 (82.03) | 71 (81.61) | 34 (82.93) | 0.035 | ||

| G2 | 23 (17.97) | 16 (18.39) | 7 (17.07) | -0.035 | ||

| Horizontal margin | χ2 = 0.00 | 0.987 | ||||

| Negative | 117 (91.41) | 79 (90.80) | 38 (92.68) | 0.072 | ||

| Positive | 11 (8.59) | 8 (9.20) | 3 (7.32) | -0.072 | ||

| Vertical margin | - | 1.000 | ||||

| Negative | 125 (97.66) | 85 (97.70) | 40 (97.56) | -0.009 | ||

| Positive | 3 (2.34) | 2 (2.30) | 1 (2.44) | 0.009 | ||

| Lymphovascular invasion | χ2 = 0.69 | 0.406 | ||||

| Negative | 120 (93.75) | 80 (91.95) | 40 (97.56) | 0.363 | ||

| Positive | 8 (6.25) | 7 (8.05) | 1 (2.44) | -0.363 | ||

| Perineural invasion | -2 | 0.320 | ||||

| Negative | 127 (99.22) | 87 (100.00) | 40 (97.56) | -0.158 | ||

| Positive | 1 (0.78) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (2.44) | 0.158 | ||

| Invasion depth | χ2 = 2.07 | 0.150 | ||||

| M | 49 (38.28) | 37 (42.53) | 12 (29.27) | -0.291 | ||

| SM | 79 (61.72) | 50 (57.47) | 29 (70.73) | 0.291 | ||

| NLR | χ2 = 5.36 | 0.021 | ||||

| < 2 | 72 (56.25) | 55 (63.22) | 17 (41.46) | -0.442 | ||

| ≥ 2 | 56 (43.75) | 32 (36.78) | 24 (58.54) | 0.442 | ||

| Follow-up time, median (Q1, Q3) | 25.50 (14.00, 58.50) | 36.00 (20.00, 66.50) | 14.00 (9.00, 38.00) | Z = -4.211 | < 0.001 | -0.843 |

In this study, univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses were performed on data from 128 patients to evaluate the prognostic impact of clinical and pathological variables (Table 4). The univariate analysis demonstrated that both SSA use and NLR were significantly associated with prognosis. Patients who underwent endoscopic treatment combined with SSAs had a lower risk of adverse outcomes [hazard ratio (HR) = 0.40, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.18-0.88, P = 0.022], whereas those with NLR ≥ 2 exhibited a higher risk (HR = 1.90, 95%CI: 1.02-3.55, P = 0.043). The multivariate analysis confirmed the independent prognostic value of these two factors. Specifically, combined endoscopic treatment with SSAs was associated with a significantly reduced risk (HR = 0.38, 95%CI: 0.17-0.90, P = 0.027), whereas NLR ≥ 2 was related to a significantly increased risk (HR = 2.14, 95%CI: 1.08-4.26, P = 0.030). Other variables - including sex, age, number of lesions, maximum tumor diameter, bleeding, perforation, pathological type, margin status, lymphovascular invasion, neural invasion, and depth of invasion - showed no significant prognostic associations in either analysis. Collectively, these results indicated SSA use and NLR as independent prognostic factors in this patient cohort.

| Variables | Single factor analysis | Multi-factor analysis | ||||

| HR | 95%CI | P value | HR | 95%CI | P value | |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | ||

| Female | 1.57 | 0.82-3.01 | 0.174 | 1.36 | 0.67-2.73 | 0.394 |

| Age | ||||||

| < 60 | 1.00 | Reference | ||||

| ≥ 60 | 0.96 | 0.47-1.96 | 0.911 | |||

| Lesion | ||||||

| < 6 | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | ||

| ≥ 6 | 1.83 | 0.96-3.48 | 0.065 | 1.64 | 0.83-3.25 | 0.158 |

| Max-diameter | ||||||

| < 10 mm | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | ||

| ≥ 10 mm | 0.59 | 0.28-1.23 | 0.161 | 0.57 | 0.23-1.41 | 0.223 |

| SSAs | ||||||

| No | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | ||

| Yes | 0.40 | 0.18-0.88 | 0.022 | 0.38 | 0.17-0.90 | 0.027 |

| Pathology | ||||||

| G1 | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | ||

| G2 | 1.15 | 0.51-2.62 | 0.731 | 2.13 | 0.88-5.18 | 0.094 |

| Horizontal margin | ||||||

| Negative | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | ||

| Positive | 1.25 | 0.38-4.09 | 0.709 | 2.26 | 0.63-8.13 | 0.213 |

| Vertical margin | ||||||

| Negative | 1.00 | Reference | ||||

| Positive | 1.31 | 0.18-9.59 | 0.793 | |||

| Lymphovascular invasion | ||||||

| Negative | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | ||

| Positive | 0.29 | 0.04-2.11 | 0.221 | 0.42 | 0.05-3.38 | 0.415 |

| Perineural invasion | ||||||

| Negative | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | ||

| Positive | 5.94 | 0.79-44.35 | 0.083 | 6.20 | 0.60-64.04 | 0.126 |

| Invasion depth | ||||||

| M | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | ||

| SM | 1.60 | 0.82-3.14 | 0.171 | 1.74 | 0.81-3.71 | 0.153 |

| NLR | ||||||

| ≥ 2 | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | ||

| < 2 | 1.90 | 1.02-3.55 | 0.043 | 2.14 | 1.08-4.26 | 0.030 |

Progression-free survival analysis based on the NLR: Figure 4A presents the Kaplan-Meier curves of survival probability for patients grouped according to the NLR. The curves represent patients with NLR < 2 (red) and NLR ≥ 2 (blue). Patients with NLR ≥ 2 had a significantly lower progression-free survival probability throughout the follow-up period than those with NLR < 2. A significant difference in progression-free survival was observed between the groups by the log-rank test (P = 0.038). The multivariate Cox regression analysis further confirmed that NLR ≥ 2 was an independent predictor of poor prognosis, indicating that patients with NLR ≥ 2 had nearly twice the risk of progression compared to those with NLR < 2.

Progression-free survival analysis based on the use of SSAs: Figure 4B presents the Kaplan-Meier curves of progression-free survival probability for patients grouped according to the use of SSA. The curves represent patients who received endoscopic treatment alone (red) and those who received endoscopic treatment combined with SSAs (blue). The results showed that patients who underwent endoscopic treatment combined with SSAs had a significantly higher progression-free survival probability throughout the follow-up period than those who underwent endoscopic treatment alone. A significant difference in progression-free survival was observed between the groups (log-rank test, P = 0.017). The multivariate Cox regression analysis further confirmed endoscopic treatment combined with SSAs as an independent predictor of good prognosis, indicating that patients who received endoscopic treatment combined with SSAs had a significantly lower risk of disease progression than those who received endoscopic treatment alone.

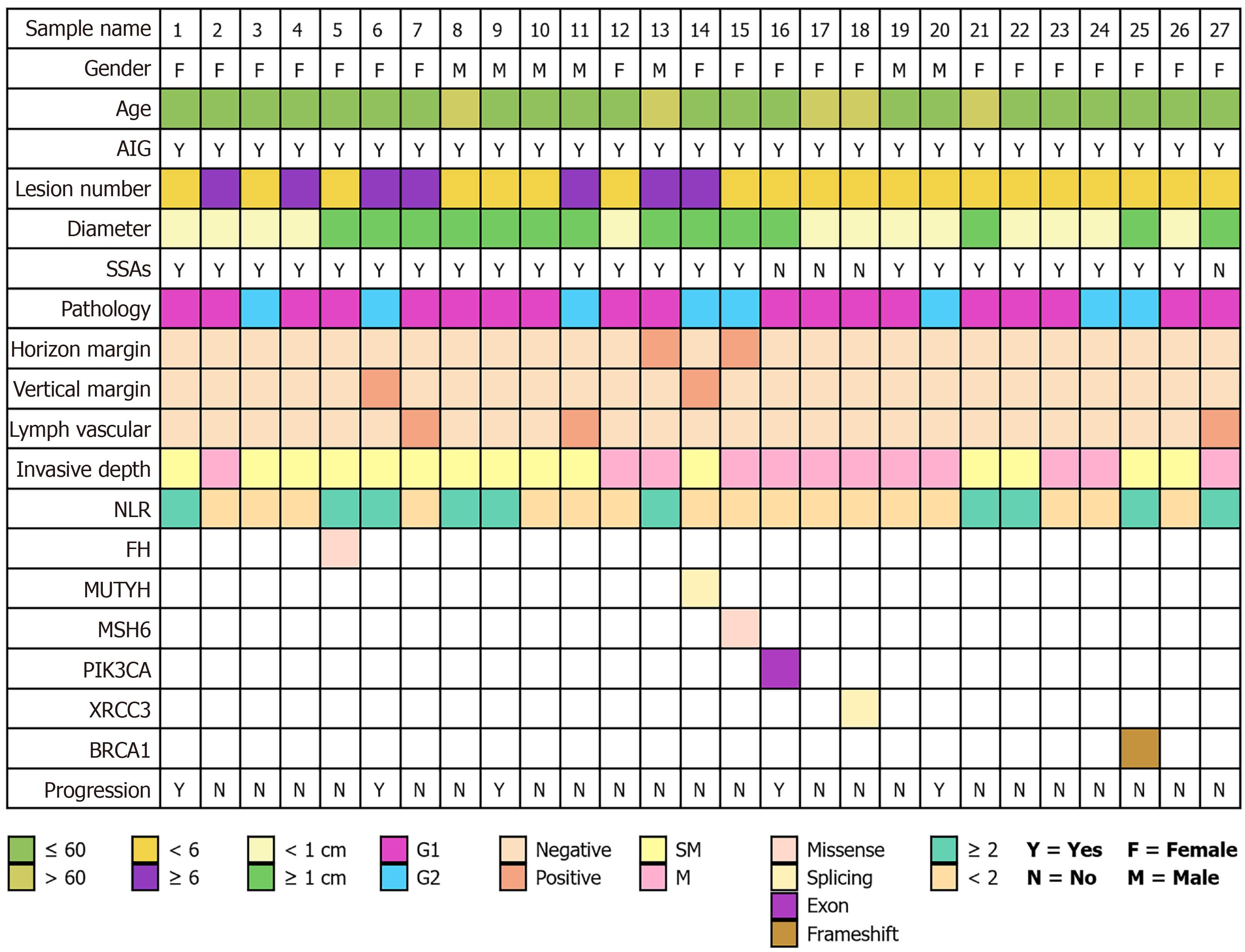

We concurrently collected germline genetic sequencing data from patients during their treatment to comprehensively characterize the gene expression patterns of this patient population as comprehensively as possible. Among the 128 patients, 27 underwent germline genetic testing, with 25 sequencing samples being saliva, 1 sample being blood, and 1 sample being lesioned tissue. Pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants were identified in 6 of these 27 individuals, yielding a mutation detection rate of 22.22%. The molecular alterations identified included a missense variant in fumarate hydratase (FH), a splice-site variant in MutY DNA glycosylase (MUTYH), a missense variant in MutS homolog 6 (MSH6), an exonic variant in phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit alpha (PIK3CA), a splice-site variant in X-ray repair cross-complementing protein 3 (XRCC3), and a frameshift variant in breast cancer 1 (BRCA1). The BRCA1 frameshift alteration was classified as definitively pathogenic. Functional predictions indicated that the MSH6 and FH variants may impair protein function, XRCC3 variant may interfere with mRNA splicing, and PIK3CA variant may constitutively activate the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-protein kinase B-mammalian target of rapamycin signaling pathway. In contrast, the clinical relevance of the MUTYH variant remains uncertain (Figure 5).

G-NETs are heterogeneous tumors originating from ECL cells in the gastric mucosa. Endoscopic treatment has become the standard therapeutic approach for type I G-NETs. Although endoscopic treatment can remove lesions, it does not alter the underlying pathogenesis of the disease. Therefore, some patients receive adjuvant therapy with SSAs before or after endoscopic treatment. In this study, we retrospectively collected the data of patients with type I G-NETs treated with endoscopy to analyze the prognosis following endoscopic treatment and the risk factors related to disease progression.

Endoscopic treatment plays a key role in managing G-NETs. Multiple studies have shown that the en bloc resection rate achieved by endoscopic treatment is 91.5%-100%, whereas the R0 resection rate is 83.3%-94.9%[18,22,23]. The safety of endoscopic treatment is high, with postoperative complications, including bleeding and perforation rates, remaining at a low level. A study involving 50 patients with G-NETs indicated that the postoperative bleeding rate after endoscopic treatment was 7.1% and the perforation rate was 3.6%[24]. In this study, the en bloc resection rate with endoscopic treatment was 100%, whereas the R0 resection rate was 89.0%. However, endoscopic treatment removes lesions without addressing the underlying pathogenesis, allowing gastrin to continue stimulating neuroendocrine cell growth. Therefore, G-NETs may recur after endoscopic treatment. Studies have shown that the recurrence rate of G-NETs after endoscopic treatment ranges from 2.4% to 63.6%[18,20,21,25]. In this study, during the median follow-up period, the progression rate in patients with NETs treated with endoscopy alone was 43.42%. Previous studies have suggested that elevated gastrin levels and positive surgical margins might be high-risk factors for recurrence[26,27]. However, in this study, gastrin levels were not comprehensively collected, as gastrin assays are not frequently performed in routine clinical practice. Other factors were not found to be significantly related to tumor recurrence. Additionally, lesion size > 10 mm and muscularis propria invasion are recognized as high-risk factors for metastasis[12]. However, after excluding lymph node metastasis and muscularis propria invasion through preoperative imaging and ultrasonography in this study, no metastasis occurred in patients with NETs > 10 mm.

In this study, we found that preoperative and postoperative adjuvant treatment with SSAs was a protective factor for type I G-NETs, effectively reducing the risk of postoperative tumor progression to improve prognosis. The mechanism of action of SSAs mainly involves the reduction in gastrin levels and direct inhibition of tumor growth[17]. Previous studies have shown that SSAs can delay tumor progression. The PROMID and CLARINET randomized controlled trials demonstrated that SSAs can delay the progression of metastatic well-differentiated gastroenteropancreatic-NENs[28,29]. A meta-analysis showed that SSAs have considerable advantages in treating recurrent or multiple G-NETs, effectively reducing the tumor recurrence rate. However, there may be a risk of disease progression following drug discontinuation[17]. The number of patients included in this study was relatively small, but it still had a specific reference significance. In our study, the timing of SSA administration formed a sequential diagnostic and treatment model for endoscopic therapy. The analysis showed that combining endoscopic treatment with SSAs has clinical advantages as it directly treats the disease by removing the lesions and reduces the possibility of recurrence by lowering gastrin production. This study further confirmed the value of combining SSAs and endoscopic treatment, particularly in reducing recurrence.

We found that the NLR was associated with disease recurrence. The NLR is a systemic inflammatory indicator based on routine blood tests and is calculated by dividing the neutrophil count by the lymphocyte count. The NLR reflects the body’s inflammatory state and immune function. A higher NLR indicates as enhanced inflammatory response and immune suppression, which may promote tumor recurrence and progression. Cao et al[30] through an analysis of 147 patients diagnosed with G-NENs and treated with radical surgery, reported that a high NLR is associated with poor prognosis. A meta-analysis showed that an elevated NLR based on blood tests is associated with poorer survival rates, in not only patients with G-NETs but also those with GEP-NEN. Unlike previous studies, the NETs included in this study were type I G-NETs, which are more indolent in biological behavior than neuroendocrine carcinomas. However, in this study, elevated NLR was still associated with disease progression. The NLR cutoff in this study was 2.0, as values greater than 2.0 are considered abnormal. Currently, the mechanism linking elevated NLR to poor prognosis remains unclear, but it may be related to tumor-associated neutrophils. Tumor-associated neutrophils in solid tumors are divided into two phenotypes: Antitumor (N1) and pro-tumor (N2). Within the tumor microenvironment, a high density of N2 neutrophils is linked to aggressive features. Conversely, N1 cells exert anti-tumor effects, while N2 cells promote progression via immune suppression and angiogenesis[31]. The mechanism by which an elevated NLR is associated with tumor progression requires further investigation, and more advanced techniques, including single-cell sequencing combined with spatial omics sequencing, should be considered for exploration.

Moreover, in this study, we analyzed the tumor grade, size, number, and presence of lymphovascular invasion; however, the results showed no significant differences between these indicators and disease recurrence. There are several possible explanations for this observation. First, type I G-NETs are relatively indolent in their biological behavior compared to neuroendocrine carcinomas. Second, the tumor sizes included in this study did not reach the critical value that could affect prognosis. A previous study reported that a tumor size of > 2 cm is associated with the prognosis of G-NETs. Additionally, this was a retrospective study, and some patients with a higher number of tumors, deeper invasion, and lymphovascular invasion, which may affect prognosis, received additional systemic therapy after endoscopic resection. Moreover, we confirmed that SSA treatment offers protective benefits against G-NETs. A previous study has suggested that surgical treatment is needed for G-NETs with > 6 lesions[32]. However, in this study, there was no significant correlation between the tumor number and recurrence, which provides a new direction for further research and reference for the formulation and optimization of future guidelines. Finally, individual differences among patients and the diversity of treatment responses may have led to the lack of significant differences in these indicators.

Genetic mutations are relatively uncommon in type I G-NETs. In this study, genetic testing was conducted on 27 patients, revealing mutations in six individuals. Due to the limited sample size and the heterogeneous, non-systematic nature of the testing within our cohort, formal statistical analysis for significance was not feasible or intended for this exploratory presentation. Based on the sequencing results, the identified aberrant genes included PIK3CA, FH, MUTYH, BRCA1, MSH6, and XRCC3. PIK3CA encodes the p110αcatalytic subunit of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, which converts PIP2 to PIP3 and activates the oncogenic protein kinase B/mammalian target of rapamycin signaling pathway. Mutations in PIK3CA may therefore contribute to tumor progression through this mechanism[33]. FH gene mutations have been associated with renal pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma, but no reports currently link them to G-NETs[34]. The MUTYH gene encodes a DNA glycosylase, which is essential for base excision repair. Its primary function is to correct specific base mismatches that occur during DNA replication, thereby safeguarding genomic stability. MUTYH mutations are associated with increased risk of colorectal polyposis and cancer[35]. BRCA1 facilitates DNA double-strand break repair via homologous recombination to maintain genomic integrity. Mutations in BRCA1 compromise this repair, leading to genomic instability and tumorigenesis[36]. MSH6 mutations cause defects in the DNA mismatch repair system, resulting in failure to correct base mismatches during DNA replication. This increases the risk of malignant transformation and promotes tumor development[37]. XRCC3 mutations may impair the function of its encoded protein, affecting the efficiency of the homologous recombination repair pathway. This compromises the cell’s ability to effectively repair DNA damage, such as double-strand breaks, thereby increasing genomic instability and creating conditions conducive to tumorigenesis[38].

However, the significance of these mutations remains unclear. Current research suggests that the pathogenesis of type I G-NETs is not solely driven by hypergastrinemia but also involves genetic alterations, including mutations in transforming growth factor-alpha, basic fibroblast growth factor, and MEN1. Heterozygous deletions of MEN1 is detected in 17%-73% of patients with type I G-NETs[39]. Future studies should include large-scale genetic assessments to clarify genetic alterations in type I G-NETs.

This study has some limitations. First, as a single-center retrospective study, its inherent design may have led to selection and information biases, thereby affecting the accuracy of the results. Second, the cohort size was relatively small, mainly attributable to the rarity of the tumor and the limited number of patients treated with SSAs, which precluded the use of propensity score matching and necessitated the use of data-driven variable selection (LASSO regression) to control for confounding. Third, we were unable to further analyze the impact of autoimmune gastritis severity, elevated gastrin levels, vitamin B12 status, anti-parietal cell antibodies, anti-intrinsic factor antibodies, or prior proton pump inhibitor use on disease progression. This limitation may affect the prognostic evaluation, and prospective studies are warranted to assess the influence of these factors on patient outcomes. Another limitation pertains to our classification of SSA administration as a baseline exposure. While this approach was chosen to reflect the initial clinical decision to initiate therapy, it is susceptible to immortal time bias. Finally, we did not conduct a more detailed stratified analysis of individualized treatment plans for patients. There may be differences in the treatment responses among patients, and we did not explore the influence of these differences on the results.

In this study, we investigated the risk factors for disease progression following endoscopic treatment in patients with type I G-NETs. Analysis of data from 128 patients revealed that combining SSAs with endoscopic treatment significantly reduced disease progression risk. Elevated NLR showed a close association with poor prognosis. These results suggest that incorporating SSAs into adjuvant endoscopic treatment is effective and that NLR has potential as a clinical prognostic tool, offering a new strategy for patient management. In addition, the limited genomic sequencing data provided valuable insight into the mutational profile. Future large-scale sequencing studies are warranted to definitively characterize the genetic alterations in G-NETs. In summary, we investigated risk factors for progression in type I G-NETs. The results highlighted the benefit of combining endoscopy with SSAs to reduce the risk of progression and improve prognosis. In the future, more attention should be paid to the risk factors for progression, including NLR. In clinical practice, further optimization of treatment strategies should be undertaken to improve the treatment efficacy for type I G-NETs and patient prognosis. Additionally, future research should increase cohort size and explore tumor biology to provide more comprehensive evidence for the management of type I G-NETs.

| 1. | Exarchou K, Stephens NA, Moore AR, Howes NR, Pritchard DM. New Developments in Gastric Neuroendocrine Neoplasms. Curr Oncol Rep. 2022;24:77-88. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Nagtegaal ID, Odze RD, Klimstra D, Paradis V, Rugge M, Schirmacher P, Washington KM, Carneiro F, Cree IA; WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board. The 2019 WHO classification of tumours of the digestive system. Histopathology. 2020;76:182-188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2554] [Cited by in RCA: 2764] [Article Influence: 460.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 3. | Dasari A, Shen C, Halperin D, Zhao B, Zhou S, Xu Y, Shih T, Yao JC. Trends in the Incidence, Prevalence, and Survival Outcomes in Patients With Neuroendocrine Tumors in the United States. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:1335-1342. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1510] [Cited by in RCA: 2666] [Article Influence: 296.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 4. | Zheng R, Zhao H, An L, Zhang S, Chen R, Wang S, Sun K, Zeng H, Wei W, He J. Incidence and survival of neuroendocrine neoplasms in China with comparison to the United States. Chin Med J (Engl). 2023;136:1216-1224. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Biancotti R, Dal Pozzo CA, Parente P, Businello G, Angerilli V, Realdon S, Savarino EV, Farinati F, Milanetto AC, Pasquali C, Vettor R, Grillo F, Pennelli G, Luchini C, Mastracci L, Vanoli A, Milione M, Galuppini F, Fassan M. Histopathological Landscape of Precursor Lesions of Gastro-Entero-Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Neoplasms. Dig Dis. 2023;41:34-48. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | McCarthy DM. Proton Pump Inhibitor Use, Hypergastrinemia, and Gastric Carcinoids-What Is the Relationship? Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:662. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Calvete O, Herraiz M, Reyes J, Patiño A, Benitez J. A cumulative effect involving malfunction of the PTH1R and ATP4A genes explains a familial gastric neuroendocrine tumor with hypothyroidism and arthritis. Gastric Cancer. 2017;20:998-1003. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Tatsuguchi A, Hoshino S, Kawami N, Gudis K, Nomura T, Shimizu A, Iwakiri K. Influence of hypergastrinemia secondary to long-term proton pump inhibitor treatment on ECL cell tumorigenesis in human gastric mucosa. Pathol Res Pract. 2020;216:153113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Lamberti G, Panzuto F, Pavel M, O'Toole D, Ambrosini V, Falconi M, Garcia-Carbonero R, Riechelmann RP, Rindi G, Campana D. Gastric neuroendocrine neoplasms. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2024;10:25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Exarchou K, Howes N, Pritchard DM. Systematic review: management of localised low-grade upper gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumours. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2020;51:1247-1267. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Exarchou K, Hu H, Stephens NA, Moore AR, Kelly M, Lamarca A, Mansoor W, Hubner R, McNamara MG, Smart H, Howes NR, Valle JW, Pritchard DM. Endoscopic surveillance alone is feasible and safe in type I gastric neuroendocrine neoplasms less than 10 mm in diameter. Endocrine. 2022;78:186-196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Tsolakis AV, Ragkousi A, Vujasinovic M, Kaltsas G, Daskalakis K. Gastric neuroendocrine neoplasms type 1: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2019;25:5376-5387. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Roberto GA, Rodrigues CMB, Peixoto RD, Younes RN. Gastric neuroendocrine tumor: A practical literature review. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2020;12:850-856. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (8)] |

| 14. | Assis Filho AC, Tercioti Junior V, Andreollo NA, Ferrer JAP, Coelho Neto JS, Lopes LR. Gastric Neuroendocrine Tumor: When Surgical Treatment Is Indicated? Arq Bras Cir Dig. 2023;36:e1768. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Panzuto F, Magi L, Esposito G, Rinzivillo M, Annibale B. Comparison of Endoscopic Techniques in the Management of Type I Gastric Neuroendocrine Neoplasia: A Systematic Review. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2021;2021:6679397. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Panzuto F, Ramage J, Pritchard DM, van Velthuysen MF, Schrader J, Begum N, Sundin A, Falconi M, O'Toole D. European Neuroendocrine Tumor Society (ENETS) 2023 guidance paper for gastroduodenal neuroendocrine tumours (NETs) G1-G3. J Neuroendocrinol. 2023;35:e13306. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 36.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Rossi RE, Invernizzi P, Mazzaferro V, Massironi S. Response and relapse rates after treatment with long-acting somatostatin analogs in multifocal or recurrent type-1 gastric carcinoids: A systematic review and meta-analysis. United European Gastroenterol J. 2020;8:140-147. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Noh JH, Kim DH, Yoon H, Hsing LC, Na HK, Ahn JY, Lee JH, Jung KW, Choi KD, Song HJ, Lee GH, Jung HY. Clinical Outcomes of Endoscopic Treatment for Type 1 Gastric Neuroendocrine Tumor. J Gastrointest Surg. 2021;25:2495-2502. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Esposito G, Cazzato M, Rinzivillo M, Pilozzi E, Lahner E, Annibale B, Panzuto F. Management of type-I gastric neuroendocrine neoplasms: A 10-years prospective single centre study. Dig Liver Dis. 2022;54:890-895. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Uygun A, Kadayifci A, Polat Z, Yilmaz K, Gunal A, Demir H, Bagci S. Long-term results of endoscopic resection for type I gastric neuroendocrine tumors. J Surg Oncol. 2014;109:71-74. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Merola E, Sbrozzi-Vanni A, Panzuto F, D'Ambra G, Di Giulio E, Pilozzi E, Capurso G, Lahner E, Bordi C, Annibale B, Delle Fave G. Type I gastric carcinoids: a prospective study on endoscopic management and recurrence rate. Neuroendocrinology. 2012;95:207-213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Jang JO, Jang WJ, Choi CW, Choi EJ, Kim SJ, Ryu DG, Park SB, Chung JH, Lee SH, Hwang SH. A single center retrospective analysis of feasibility of diagnostic endoscopic resection for grade 1 or 2 gastric neuroendocrine tumors. Sci Rep. 2025;15:16315. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Kim HH, Kim GH, Kim JH, Choi MG, Song GA, Kim SE. The efficacy of endoscopic submucosal dissection of type I gastric carcinoid tumors compared with conventional endoscopic mucosal resection. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2014;2014:253860. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 24. | Varas Lorenzo MJ, Abad Belando R, Muñoz Agel F, Gornals Soler JB. Endoscopic management of gastric neuroendocrine tumors: an analysis of 50 cases. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2024;116:47-48. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Chen YY, Guo WJ, Shi YF, Su F, Yu FH, Chen RA, Wang C, Liu JX, Luo J, Tan HY. Management of type 1 gastric neuroendocrine tumors: an 11-year retrospective single-center study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2023;23:440. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Huang J, Liu H, Yang D, Xu T, Wang J, Li J. Personalized treatment of well-differentiated gastric neuroendocrine tumors based on clinicopathological classification and grading: A multicenter retrospective study. Chin Med J (Engl). 2024;137:720-728. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Sheikh-Ahmad M, Saiegh L, Shalata A, Bejar J, Kreizman-Shefer H, Sirhan MF, Matter I, Swaid F, Laniado M, Mubariki N, Rainis T, Rosenblatt I, Yovanovich E, Agbarya A. Factors Predicting Type I Gastric Neuroendocrine Neoplasia Recurrence: A Single-Center Study. Biomedicines. 2023;11:828. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Rinke A, Wittenberg M, Schade-Brittinger C, Aminossadati B, Ronicke E, Gress TM, Müller HH, Arnold R; PROMID Study Group. Placebo-Controlled, Double-Blind, Prospective, Randomized Study on the Effect of Octreotide LAR in the Control of Tumor Growth in Patients with Metastatic Neuroendocrine Midgut Tumors (PROMID): Results of Long-Term Survival. Neuroendocrinology. 2017;104:26-32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 184] [Cited by in RCA: 277] [Article Influence: 30.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Caplin ME, Pavel M, Ćwikła JB, Phan AT, Raderer M, Sedláčková E, Cadiot G, Wolin EM, Capdevila J, Wall L, Rindi G, Langley A, Martinez S, Blumberg J, Ruszniewski P; CLARINET Investigators. Lanreotide in metastatic enteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:224-233. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1142] [Cited by in RCA: 1352] [Article Influence: 112.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Cao LL, Lu J, Lin JX, Zheng CH, Li P, Xie JW, Wang JB, Chen QY, Lin M, Tu RH, Huang CM. A novel predictive model based on preoperative blood neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio for survival prognosis in patients with gastric neuroendocrine neoplasms. Oncotarget. 2016;7:42045-42058. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Wang Y, Wen B, Zhang Y, Dong K, Tian S, Li L. Prognostic value of neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio in gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasm: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PeerJ. 2025;13:e19186. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Corey B, Chen H. Neuroendocrine Tumors of the Stomach. Surg Clin North Am. 2017;97:333-343. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 33. | Morin GM, Zerbib L, Kaltenbach S, Fraissenon A, Balducci E, Asnafi V, Canaud G. PIK3CA-Related Disorders: From Disease Mechanism to Evidence-Based Treatments. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2024;25:211-237. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Castro-Vega LJ, Buffet A, De Cubas AA, Cascón A, Menara M, Khalifa E, Amar L, Azriel S, Bourdeau I, Chabre O, Currás-Freixes M, Franco-Vidal V, Guillaud-Bataille M, Simian C, Morin A, Letón R, Gómez-Graña A, Pollard PJ, Rustin P, Robledo M, Favier J, Gimenez-Roqueplo AP. Germline mutations in FH confer predisposition to malignant pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas. Hum Mol Genet. 2014;23:2440-2446. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 254] [Cited by in RCA: 302] [Article Influence: 23.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Thet M, Plazzer JP, Capella G, Latchford A, Nadeau EAW, Greenblatt MS, Macrae F. Phenotype Correlations With Pathogenic DNA Variants in the MUTYH Gene: A Review of Over 2000 Cases. Hum Mutat. 2024;2024:8520275. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Buckley KH, Niccum BA, Maxwell KN, Katona BW. Gastric Cancer Risk and Pathogenesis in BRCA1 and BRCA2 Carriers. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14:5953. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Frederiksen JH, Jensen SB, Tümer Z, Hansen TVO. Classification of MSH6 Variants of Uncertain Significance Using Functional Assays. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:8627. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Han S, Zhang HT, Wang Z, Xie Y, Tang R, Mao Y, Li Y. DNA repair gene XRCC3 polymorphisms and cancer risk: a meta-analysis of 48 case-control studies. Eur J Hum Genet. 2006;14:1136-1144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Asa SL, La Rosa S, Basturk O, Adsay V, Minnetti M, Grossman AB. Molecular Pathology of Well-Differentiated Gastro-entero-pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors. Endocr Pathol. 2021;32:169-191. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/