Published online Feb 28, 2026. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v32.i8.113861

Revised: November 10, 2025

Accepted: January 6, 2026

Published online: February 28, 2026

Processing time: 158 Days and 18.6 Hours

Pancreatic acinar cell carcinoma (PACC) and pancreatoblastoma (Pb) are rare exocrine pancreatic malignancies with liver-dominant metastatic patterns and poor prognosis. Limited treatment options exist beyond the extrapolated pan

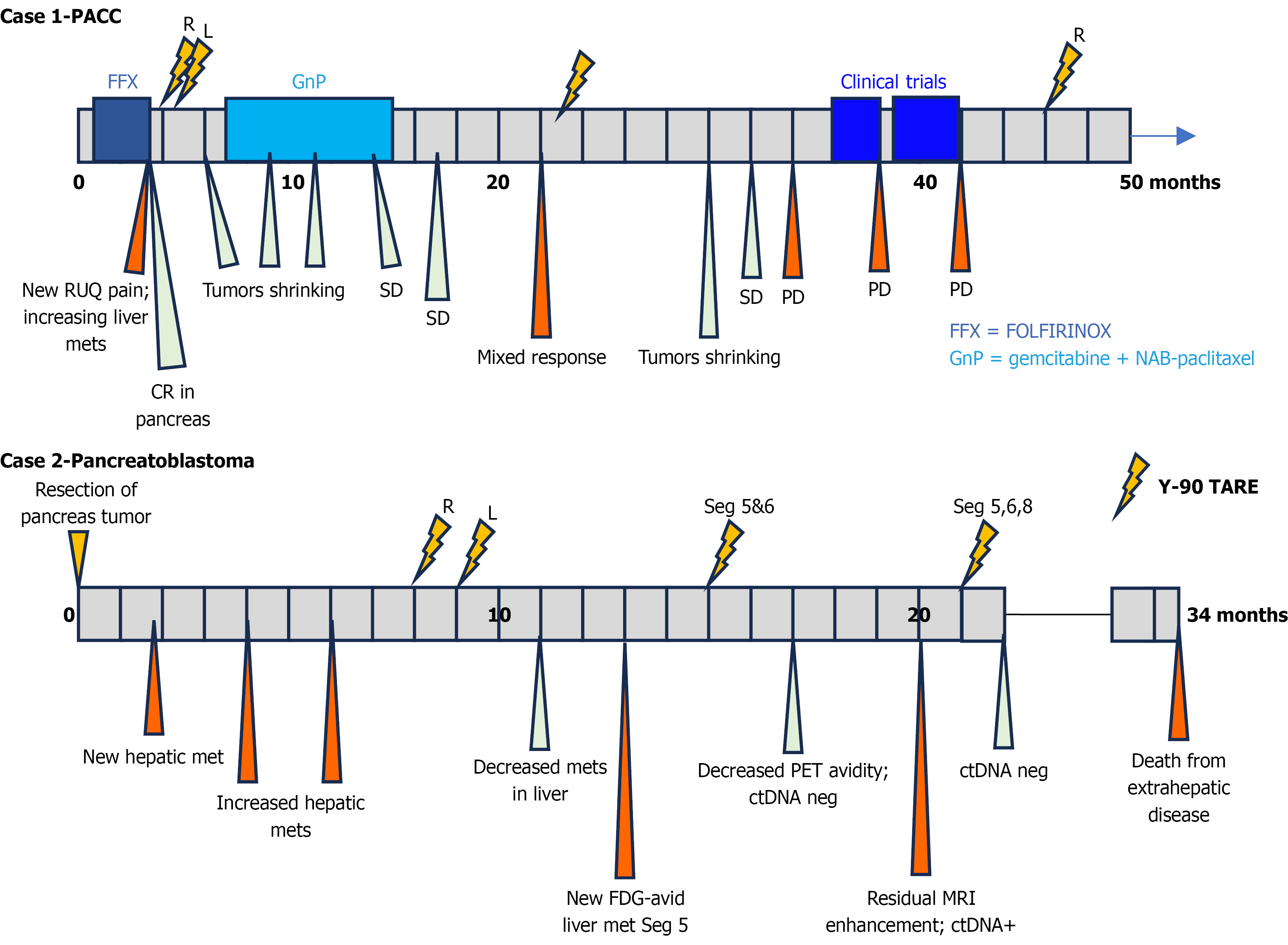

Case 1: A 62-year-old man with metastatic PACC underwent four Y-90 radioembolizations over 46 months, achieving partial responses after each treatment with sustained disease control exceeding one year without systemic therapy. Case 2: A 78-year-old woman with metastatic Pb following radical pancreaticoduodenectomy received four sequential Y-90 treatments targeting hepatic metastases, demonstrating partial responses to the treated metastases which established ongoing local disease control. Both patients tolerated multiple Y-90 sessions well with minimal complications. The treatments were successfully integrated with systemic therapies and provided meaningful symptom relief. These cases demonstrate the radiosensitivity of these rare malignancies and the feasibility of repeated Y-90 administrations over extended intervals in selected patients.

Y-90 radioembolization achieves durable hepatic response in rare pancreatic exocrine malignancies with a favorable safety profile.

Core Tip: We report the use of yttrium-90 (Y-90) radioembolization in pancreatic acinar cell carcinoma and adult pancreatoblastoma hepatic metastases. Both patients achieved durable partial responses with multiple Y-90 treatments over extended periods, and tolerated the therapy well. These rare exocrine pancreatic malignancies exhibited marked radiosensitivity, supporting early consideration of Y-90 radioembolization in liver-dominant disease. The successful integration with systemic therapies and ability to repeat treatments safely over multi-year intervals highlights Y-90’s potential as a cornerstone locoregional therapy for these challenging cancers.

- Citation: Skorupan N, Sperling D, Nutting C, Miettinen M, Cohn A, Alewine C. Use of yttrium-90 radioembolization to control liver metastases in pancreatic acinar cell carcinoma and pancreatoblastoma: Two case reports. World J Gastroenterol 2026; 32(8): 113861

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v32/i8/113861.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v32.i8.113861

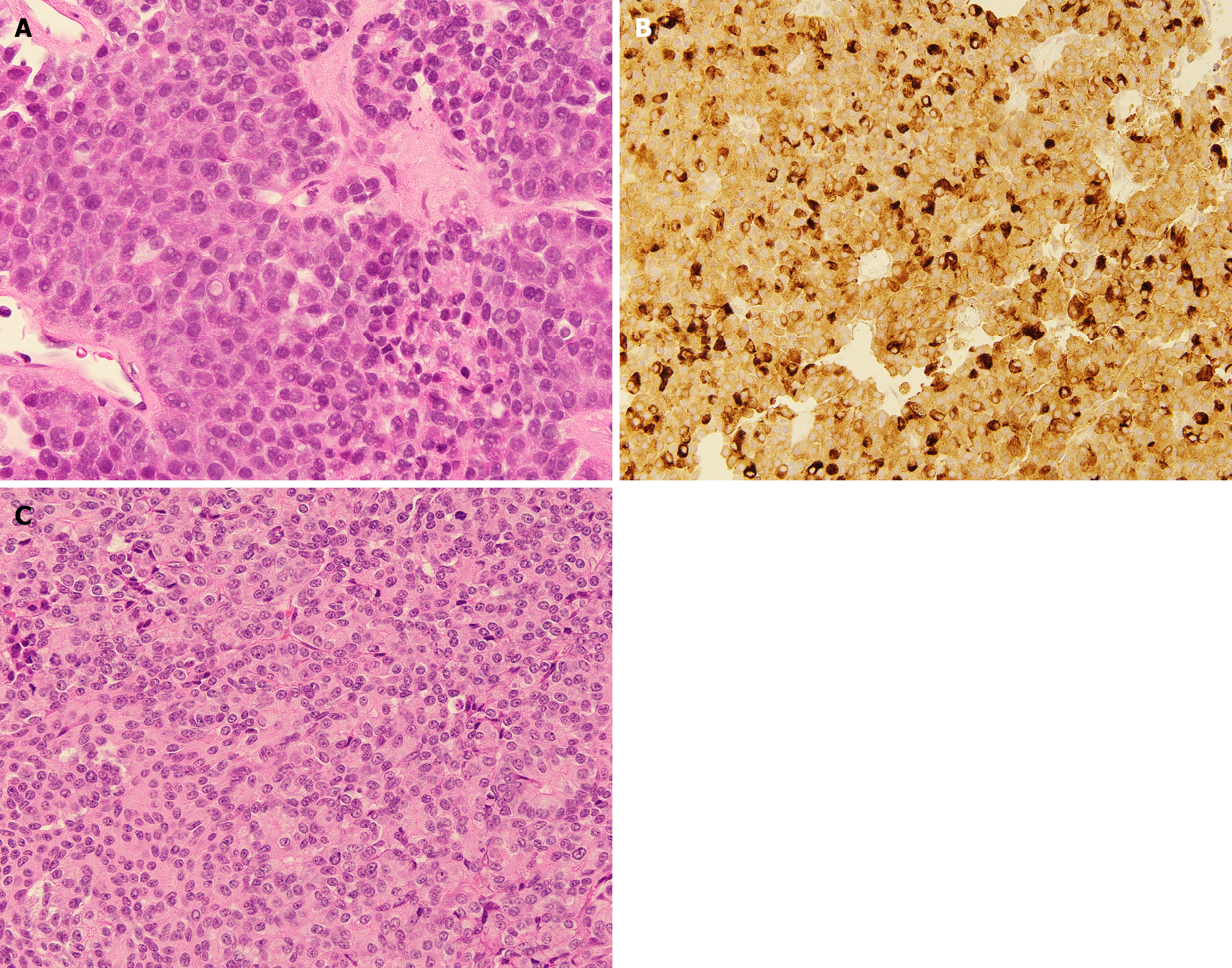

Pancreatic acinar cell carcinoma (PACC) and pancreatoblastoma (Pb) are rare exocrine pancreatic malignancies that present unique clinical challenges, particularly when metastatic to the liver. PACC accounts for approximately 1%-2% of adult pancreatic tumors[1] while Pb is predominantly a pediatric malignancy that rarely occurs in adults[2]. These malignancies represent distinct entities with unique biological and molecular features that differentiate them from pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), the most common histology of pancreatic cancer. Both PACC and Pb arise from pancreatic acinar cells and are characterized by acinar differentiation (Figure 1), frequent alterations in the Wnt signaling pathway, and recurrent loss of heterozygosity on chromosome 11p[3]. A large national database analysis revealed that nearly half of PACC and over 50% of Pb patients present with stage IV disease[4]. For both PACC and Pb, liver is the most common site of metastasis[5,6].

In PACC and Pb, the clinical presentation of metastatic disease is often nonspecific. Patients frequently report abdominal pain or weight loss, while others are diagnosed incidentally during imaging studies for another indication. The prognosis for metastatic disease remains poor, with median overall survival (OS) of 11.2 months for stage IV PACC and 24.1 months for Pb[4]. Due to the rarity of these tumors, treatment approaches for advanced disease are frequently extrapolated from the PDAC literature, utilizing regimens such as FOLFIRINOX[1]. In addition, Pb may may be treated by pediatric-inspired protocols that are cisplatin- or doxorubicin-based[6].

Increasing evidence suggests that locoregional therapies, including radiofrequency ablation, transarterial radioembolization, and transarterial chemoembolization improve outcomes in selected PDAC patients[7]. Radioembolization with yttrium-90 (Y-90) microspheres has demonstrated useful anti-tumor activity with a favorable safety profile in PDAC[8,9], but there is limited data available for PACC or Pb. Due to the liver-dominant metastatic pattern of PACC and Pb, the uninspiring outcomes with existing systemic therapies given for advanced disease, and the favorable safety profile of Y-90, it is reasonable to consider whether Y-90 microspheres might also benefit patients with PACC and Pb.

Here, we present two cases of rare exocrine pancreatic cancer (PACC and Pb) in which Y-90 was successfully emp

Case 1: A 62-year-old white American man presented with worsening right upper quadrant pain at 4 months after his initial pancreatic cancer diagnosis.

Case 2: A 78-year-old white American woman presented with a new enhancing hepatic lesion on surveillance imaging two months after pancreaticoduodenectomy for Pb.

Case 1: Four months prior, the patient had been diagnosed with PACC after presenting with several months of intermittent abdominal discomfort accompanied by left shoulder pain and abnormal liver tests. Initial imaging revealed multiple hepatic lesions (1.0-7.5 cm) and a 2.4 cm × 2.2 cm mass in the pancreatic uncinate process, with an indeterminate 3 mm right upper lobe pulmonary nodule. Positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) confirmed extensive liver metastases without pancreatic uptake. Ultrasound-guided liver biopsy demonstrated metastatic carcinoma with acinar differentiation, positive B-cell lymphoma 2 and chymotrypsin immunostains, consistent with PACC. FOLFIRINOX was initiated and he completed 4 cycles with stable disease on short-interval restaging CT. However, he returned to clinic with worsening right upper quadrant pain.

Case 2: Two months prior, the patient underwent distal pancreatectomy and splenectomy for a large pancreatic mass. Her initial presentation had been elevated creatinine on routine blood work after returning from a trip, though she was asymptomatic at that time. Physical examination revealed a firm, nontender, left upper quadrant mass extending about 6 cm below the left costal margin. Renal ultrasound showed a large mass in the left upper abdomen, confirmed on CT as a large mass with central necrosis measuring 17 cm × 14 cm × 12 cm, exerting mass effect on intraabdominal organs and displacing the left kidney. Initial endoscopic biopsy suggested acinar or neuroendocrine tumor, prompting surgical exploration. Final pathology demonstrated moderately differentiated Pb, with lymphovascular invasion, negative margins and no nodal involvement (0/17, pT3pN0). She now presented with a new 1.3 cm enhancing lesion noted in the left hepatic lobe on surveillance imaging.

Case 1: He had a history of irritable bowel syndrome, depression and insomnia, and no history of cirrhosis or liver dysfunction.

Case 2: The patient had a history of hyperlipidemia on atorvastatin, osteoporosis for which she took vitamin D, and noncancerous polyps seen on colonoscopy in 2020. She had no history of cirrhosis or liver dysfunction.

Case 1: His mother was a non-smoker and died of non-small cell lung cancer in her 60s, his maternal uncle died in his 40s from colon cancer and his paternal grandfather who was a smoker died of lung cancer in his 70s.

Case 2: No significant family history.

Case 1: Unavailable from the outside documentation at the time of presentation.

Case 2: No physical exam was performed at this telehealth visit.

Case 1: Bilirubin was reported as 1.5 mg/dL per the patient’s treating interventional radiologist. Other laboratory studies are unavailable from the outside documentation at the time of presentation.

Case 2: Unremarkable.

Case 1: Early restaging CT showed enlarging liver lesions consistent with disease progression and no evidence of cirrhosis or portal vein involvement by tumor. PET/CT confirmed extensive liver metastases without tracer uptake in the pancreas.

Case 2: Surveillance imaging at two months post-surgery revealed a 1.3 cm enhancing lesion in the left hepatic lobe. By four months, this lesion had grown to 1.6 cm, with additional subcentimeter foci in segments 5 and 6. At six months, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) confirmed a new 2.0 cm × 2.0 cm lesion in segment 6 and 1.1 cm × 1.1 cm lesion in segment 2. The tumor did not involve the portal vein.

Metastatic PACC. Ultrasound-guided liver biopsy demonstrated metastatic carcinoma with acinar differentiation, and positive B-cell lymphoma 2 and chymotrypsin immunostains, consistent with PACC. Next generation sequencing revealed pathogenic mutations in KRAS (Q61H), CREBBP, PRKAR1A, and TGFBR2.

Metastatic Pb to the liver following surgical resection. Molecular profiling identified pathogenic CTNNB1 and GRIN2A mutations (Table 1).

| Tumor type | Mutated gene |

| Pancreatoblastoma: (NCI COMPASS) | Pathogenic: CTNNB1, GRIN2A |

| VUS: ACIN1, CDKL2, CHRNA2, DCHS2, ERBIN, FCRL3, FNDC1, GLDC, GMPS, GRID2, IL23A, JAK3, KRT34, L3MBTL3, LTBP2, MAML1, MRPS30, NRP2, OR51M1, PCDH19, PPM1N, PRDM10, SETD6, SGPL1, SLC27A6, SMAD4, SORBS3, SP100, SPATC1 L, TBXA2R, TCHP | |

| PACC: (NCI COMPASS) | Pathogenic: KRAS Q61H, CREBBP, PRKAR1A, TGFBR2 |

| CNV: Amplification, AKT3, NTRK1, MDM4; loss: RB1, BRCA2 | |

| VUS: ATR, CHD4, FGF6, FGFR3, LAMP1, LRP1B, MGA, PRKDC, SETD2, SLX4, ZBTB7A, ZFHX3 |

The patient was referred to an interventional radiologist who recommended Y-90 radioembolization based on disease location, lack of cirrhosis, and lack of portal vein involvement. The patient underwent two lobar Y-90 treatments at 4 and 5 months after his initial diagnosis, targeting first the right and then the left hepatic lobe. Restaging at 6 months after diagnosis demonstrated a partial response (PR) in the treated lesions, with significant reduction in lesion size and in

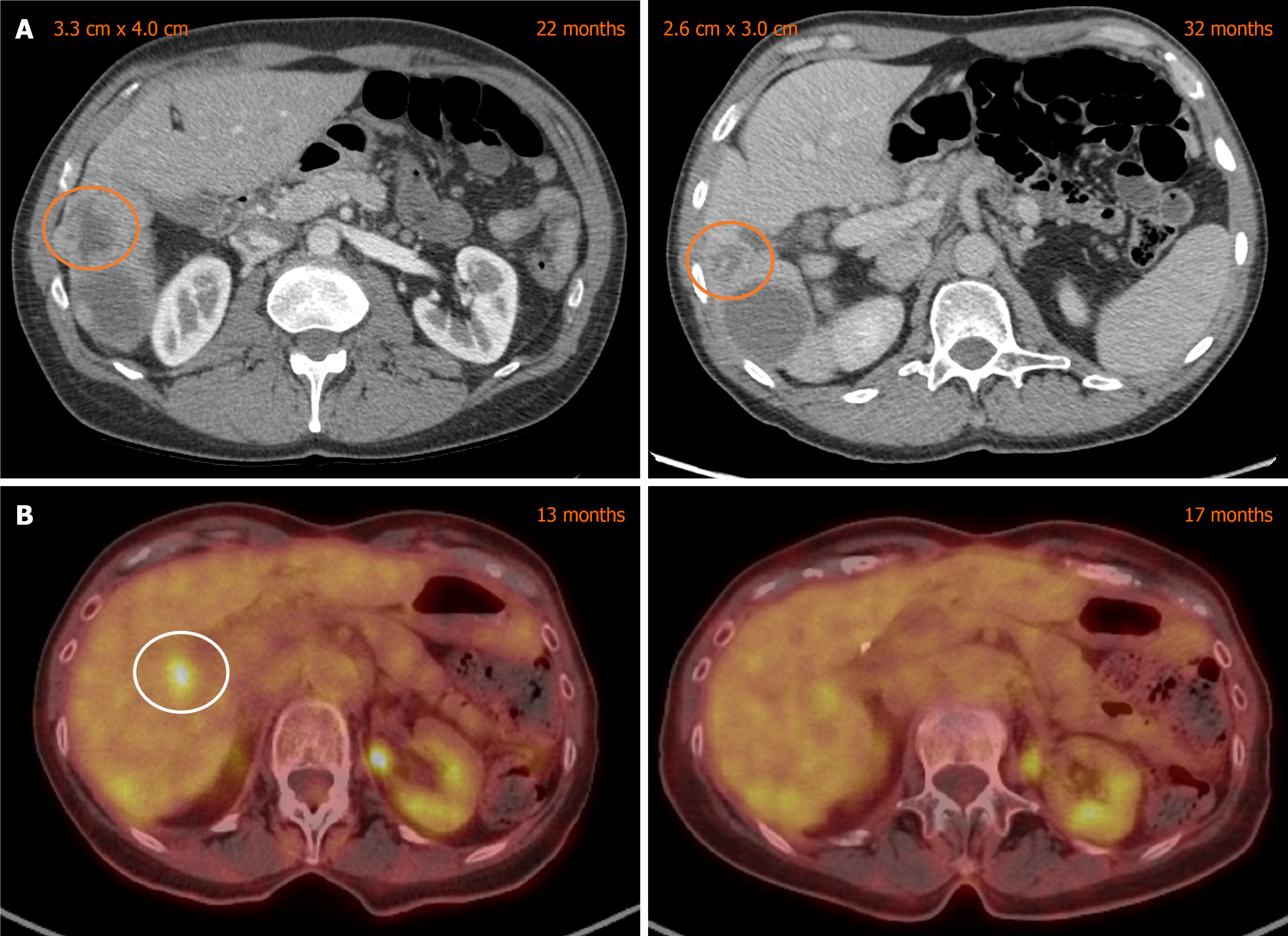

Accordingly, a third Y-90 session was administered at 23 months to retreat growing tumors, which he tolerated well, apart from post-interventional fatigue. Follow up CT at 30 months showed a renewed response (Figure 2A) in treated lesions, and scans at 32 months continued to show stability. However, progression in the right lobe at 34 months let to enrollment in an olaparib clinical trial at 36 months, discontinued 2 months later for hepatic progression. At 39 months, the patient enrolled on a clinical trial testing a bromodomain and extraterminal domain inhibitor plus talazoparib, achieving stable hepatic disease through two cycles. The study treatment was paused due to biliary obstruction that caused bilirubin elevation to 4.0 mg/dL, leading to biliary stent placement. He was ultimately taken off clinical trial treatment for disease progression.

Once the bilirubin normalized, a fourth Y-90 radioembolization was delivered to the right lobe at 46 months which the patient tolerated well and led to symptom relief. Notably, outside of the aforementioned biliary obstruction, the patient’s bilirubin remained stable at approximately 1.5 mg/dL throughout his disease course, and he did not suffer any Y-90 treatment-related complications.

Given the absence of evidence supporting systemic chemotherapy in Pb and the patient’s preference to avoid cytotoxic treatment, the multidisciplinary tumor board recommended locoregional therapy with Y-90 radioembolization. She was deemed eligible with normal liver function, lack of cirrhosis and no portal vein involvement. She received two sequential Y-90 treatments: To the right hepatic lobe at eight months post-surgery and to the left lobe at nine months. She had no complications from these procedures.

A restaging MRI at eleven months demonstrated a PR in segments 2, 5, and 6. At fourteen months, imaging showed no viable enhancement in the initially treated lesions but progression in segment 5, which was confirmed as fluorodeoxyglucose-avid on PET/CT. A third Y-90 session targeting segments 5 and 6 was administered at 16 months. Follow-up PET at 18 months revealed decreased metabolic activity in the treated sites (Figure 2B). However, MRI at 20 months showed residual enhancement in segment 5, so a fourth Y-90 treatment encompassing segments 5, 6, and 8 was delivered at 21 months.

Restaging CT at 49 months post-diagnosis (and 45 months since initial Y-90 treatment) demonstrated a PR with decreased lesion size and no new extrahepatic sites. He remains under close multidisciplinary surveillance.

Throughout her course, the patient tolerated all interventions well, without any Y-90-related complications. She later developed bone metastases and succumbed to extrahepatic disease progression. Notably, the hepatic metastatic disease remained stable per her latest available imaging at the time of our follow-up cut-off.

We report two patients with rare pancreatic exocrine malignancies, PACC and Pb, who achieved durable hepatic responses after multiple Y-90 radioembolization sessions (Figure 3). These cases illustrate the radiosensitivity of these uncommon pancreatic subtypes, the safety of repeated Y-90 administrations in this patient population, and the value of integrating transarterial radioembolization with multimodal treatment strategies. Y-90 radioembolization has emerged as a potent locoregional therapy for hepatic malignancies[10,11], delivering high-dose, targeted beta-radiation to hepatic tumors via the arterial circulation by exploiting the preferential arterial blood supply of metastatic lesions relative to normal liver parenchyma[12]. It is generally well tolerated and frequently used in primary hepatocellular carcinoma, or neuroendocrine and colorectal liver metastases[13]. We performed a comprehensive literature review using PubMed to examine the use of Y-90 radioembolization in PDAC and rarer subtypes of pancreatic cancer (Table 2).

| Ref. | Time period | Report type | Tumor type | Intervention | Patients (n) | Setting/Location | Clinical outcomes | Safety notes |

| Nasser et al[14], 2017 | Case report | PACC | Y-90 | 1 | Brazil | > 50% tumor shrinkage in all liver metastases; 3 lesions complete response; disease control | No Y-90-related toxicity reported; lipase tumor marker normalized | |

| Blume et al[15], 2025 | 2013-2023 | Retrospective study | PACC | Y-90, HAE | 9 (18 sessions: 14 HAE, 4 Y-90) | United States (MSKCC) | LTPFS 6.77 months after 1st treatment; 6 months; LTPFS: 59.83%: Extended to 22.3 months with repeat treatments; 1-year OS 66.67% (mOS not reached at approximately 16 months follow-up) | 28% of treatments had AEs, mostly mild (grade 1 post-embolization syndrome); 1 fatal hepatic abscess (post-Whipple patient). 1 grade 3 PE. Concludes acceptable safety |

| Krug et al[18], 2012 | Case report | SPNP | Y-90 | 1 | Germany | Durable complete remission of liver metastases for 4 years postY-90 and 10 years after initial diagnosis | No complications | |

| Dyas et al[19], 2020 | Case report | SPNP | Y-90 | 1 | United States (University of Colorado) | Y-90 enabled right hemi-hepatectomy for recurrent SPNP; 50% residual viability | No complications | |

| Cao et al[21], 2010 | Retrospective study | PC | Y-90 | 7 | Australia | 2/5 PR, 1/5 SD | No major complications | |

| Michl et al[9], 2014 | 2004-2011 | Retrospective study | PC | Y-90 | 19 | Germany | Objective liver ORR: 47%; liver mPFS 3.4 months; mOS 9.0 months after Y-90 (24% 1-year survival) | Mostly mild acute toxicity (≤ grade 3); noted long-term risks: Abscess, ulcer, cholangitis in few |

| Gibbs et al[20], 2015 | 2006-2009 | Prospective phase II trial | PDAC | Y-90 + chemotherapy | 14 | Australia (2 centers) | Whole-liver Y-90 + 5FU, gem chemotherapy; liver DCR 93% (PR or SD); median liver PFS 5.2 months; OS 5.5 months overall (12.2 months for patients with liver-only disease) | Grade 3/4 biochemical/clinical toxicity in 57% of patients; 1 treatment-related death (liver failure). Advised careful selection (better outcomes if primary resected) |

| Kim et al[23], 2016 | 2012-2015 | Retrospective study | PDAC | Y-90 + chemotherapy | 16 | United States (Georgetown) | Y-90 integrated with chemotherapy in 15 patients; mOS 22 months from metastasis diagnosis, 12.5 months post-Y-90; liver ORR 31% (4/13), SD 38% (4/13) | 2 patients with grade 3 events (bilirubin elevation, cholecystitis); no grade 4-5 toxicity |

| Kim et al[22], 2019 | 2011-2017 | Multicenter retrospective study | PDAC | Y-90 + chemotherapy | 33 | United States (3 centers) | Y-90 as 2nd-line; RECIST: 42% PR, 37% SD; mOS 8.1 months after Y-90 (20.8 months from diagnosis) | No grade 4-5 toxicity; 3 patients with grade 3 LFT elevations; 2 patients showing short-term grade 3 pain or ascites (approximately 6%) |

| Nezami et al[24], 2019 | Phase Ib trial | PDAC, ICC | Y-90 + gemcitabine | 8 (3 PDAC, 5 ICC) | United States (Yale) | Combined Y-90 glass microspheres + gemcitabine (up to 600 mg/m2): PC + ICC: Median hepatic PFS 8.7 months; ORR 62%; 1/8 patients with CR; PC: Hepatic mPFS 2.37 months, mPFS 4.4 months, best response: SD | All patients had grade 1 AEs, 3/8 grade 2 hepatobiliary toxicity, 1/8 grade 3 (short hospitalization); no treatment-related deaths | |

| Kayaleh et al[8], 2020 | 2010-2017 | Retrospective study | PDAC | 26 | United States (Moffitt) | Y-90 (glass microspheres) as 2nd line; mOS 7.0 months from Y-90, mOS from diagnosis 33.0 months; at 3 months: 1/22 PR, 9/22 SD, on imaging | 4/26 (15%) had grade 3 toxicities (LFT or bilirubin elevations); clinical side effects mostly grade 1-2 fatigue, pain | |

| Helmberger et al[13], 2021 | 2015-2017 | Prospective observational study (CIRT registry) | Tumors with liver metastases | 1027 total; 32 PC | Europe (multicenter) | All indications: 68.2% palliative intent; PC metastases: MOS 5.6 months | All patients 2.5% grade 3-4 AEs within 30 days |

Our PACC patient underwent four Y-90 treatments, achieving radiologic decrease in tumor size after each session, one of which led to a sustained clinical response to the treated sites that lasted more than a year without any systemic therapy. This is consistent with Nasser et al’s report[14] of > 50% liver lesion shrinkage and complete response in some nodules, with > 12 months of disease control, although with adjunct chemotherapy. A retrospective series of 9 PACC patients at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, including four Y-90 sessions, demonstrated a local tumor progression-free survival (LTPFS) of 6.8 months after first treatment, with a 6-month LTPFS rate of 60%. The benefit was extended to a median LTPFS of 22 months with repeated treatments (“assisted LTPFS”), with a median OS of 66.67% at 1 year. Three patients who received Y-90 radioembolization were evaluable for radiologic response, one had PR, one had stable disease, and one progressed[15]. The treatment was generally well tolerated with 3/18 evaluable patients developing grade 1 post-embolization syndrome. Notable exceptions included one grade 5 hepatic abscess in a patient who received bland chemoembolization and one grade 3 pulmonary embolism in a patient with prior history of venous thromboembolism[15]. Our patient’s pattern of initial PR, systemic control and subsequent PRs at 30 and 50 months since the diagnosis mirrors this “assisted” durability and confirms the feasibility of multiple Y-90 sessions over extended intervals.

Pb, primarily a pediatric tumor, frequently metastasizes to the liver in adults. To our knowledge, this is the first case of adult Pb treated with Y-90 radioembolization reported in the literature. Our patient received a total of four Y-90 treat

Additionally, solid pseudopapillary neoplasm of the pancreas exemplifies another rare exocrine subtype responsive to Y-90 radioembolization. Krug et al[18] describe a patient with recurrent metastatic solid pseudopapillary neoplasm of pancreas who achieved a four-year complete metabolic and radiographic remission following a single radioembolization session. Similarly, Dyas et al[19] report a case in which Y-90 was utilized used as a bridge to a curative metastasectomy in a 59-year-old patient. These cases underscore the potential of Y-90 in managing rare pancreatic tumors metastatic to the liver. Comparative data in metastatic PDAC serve as a benchmark, retrospective studies and a phase II trial report response rates of 20%-50%, disease control rates of 60%-80%, and a median OS of 6 to 12 months following Y-90 radioembolization. However, Y-90 was typically integrated with systemic chemotherapy in these studies, which confounds as

Although Y-90 radioembolization is reported as generally well tolerated in this patient population who typically do not have underlying liver dysfunction, most patients do experience short-term toxicities. A case series from Germany reported occurrence of post-embolization syndrome manifested as fever, nausea, fatigue and abdominal pain in 11 out of 11 evaluable patients, the majority of which were low grade[9]. However, occurrences of fatal hepatic failure and abscess formation have been reported, highlighting the importance of strict patient selection and the routine use of prophylactic antibiotics[9,20]. In our PACC patient, chemotherapy was initiated after the first two Y-90 administrations, demonstrating Y-90’s role as consolidative therapy. Additionally, Y-90 ablated residual liver lesions in both patients, delaying the need for further chemotherapy and illustrating effective multidisciplinary sequencing.

Optimal therapeutic sequencing integrates Y-90 with systemic and surgical modalities. When administered during first-line chemotherapy, radioembolization may downstage unresectable hepatic lesions, making them amenable to resection or ablation. As salvage therapy in chemorefractory disease, Y-90 may provide meaningful local control and symptomatic relief. Furthermore, serial radioembolizations can sustain disease control over multi-year intervals in select patients, as demonstrated in our PACC and Pb cases. These observations support early evaluation for Y-90 radioembolization in patients with rare pancreatic exocrine neoplasms presenting with liver-dominant disease, emphasizing the need for multidisciplinary care in this patient population.

The current literature on Y-90 embolization in rare pancreatic malignancies consists only of case reports and small case series with inherent selection bias and patient heterogeneity. Despite the challenges of studying rare tumors, prospective trials in PACC are feasible[25] and should be pursued through either centralized national institutions or collaborative registries. Conduct of such trials in the future would be important for optimizing Y-90 dosing, defining how to sequence with chemotherapy, and refining safety criteria for patient selection, but are not currently planned. Additionally, biomarker-driven investigations to identify predictors of radiosensitivity could help to identify patients with tumors most likely to respond to Y-90.

These cases reinforce Y-90 radioembolization as an effective and safe locoregional therapy for selected patients with PACC and Pb liver metastases. The durable responses seen over extended intervals demonstrate Y-90’s capacity to achieve long term local control in rare pancreatic tumors. Incorporating Y-90 into multidisciplinary management, guided by tumor histology and patient status, may significantly extend disease control and improve outcomes in this underserved population. Prospective trials are needed to identify patients who would derive the most benefit.

This work was completed while Nebojsa Skorupan was affiliated with the National Cancer Institute. The author’s current affiliation is AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals LP.

| 1. | Skorupan N, Ghabra S, Maldonado JA, Zhang Y, Alewine C. Two rare cancers of the exocrine pancreas: to treat or not to treat like ductal adenocarcinoma? J Cancer Metastasis Treat. 2023;9:5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Omiyale AO. Adult pancreatoblastoma: Current concepts in pathology. World J Gastroenterol. 2021;27:4172-4181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Tanaka A, Ogawa M, Zhou Y, Hendrickson RC, Miele MM, Li Z, Klimstra DS, Wang JY, Roehrl MHA. Proteomic basis for pancreatic acinar cell carcinoma and pancreatoblastoma as similar yet distinct entities. NPJ Precis Oncol. 2024;8:221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Qian J, Tirukkovalur NV, Ceuppens S, Singhi A, Lee KK, Zureikat AH, Paniccia A. Comparative Study of Pancreatic Acinar Cell Carcinoma and Pancreatoblastoma: Insights From the National Cancer Database. J Surg Res. 2025;311:250-258. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Sridharan V, Mino-Kenudson M, Cleary JM, Rahma OE, Perez K, Clark JW, Clancy TE, Rubinson DA, Goyal L, Bazerbachi F, Visrodia KH, Qadan M, Parikh A, Ferrone CR, Casey BW, Fernandez-Del Castillo C, Ryan DP, Lillemoe KD, Warshaw AL, Krishnan K, Hernandez-Barco YG. Pancreatic acinar cell carcinoma: A multi-center series on clinical characteristics and treatment outcomes. Pancreatology. 2021;21:1119-1126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Yuan J, Guo Y, Li Y. Diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis of adult pancreatoblastoma. Cancer Med. 2024;13:e70132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Timmer FEF, Geboers B, Nieuwenhuizen S, Schouten EAC, Dijkstra M, de Vries JJJ, van den Tol MP, Meijerink MR, Scheffer HJ. Locoregional Treatment of Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer Utilizing Resection, Ablation and Embolization: A Systematic Review. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13:1608. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Kayaleh R, Krzyston H, Rishi A, Naziri J, Frakes J, Choi J, El-Haddad G, Parikh N, Sweeney J, Kis B. Transarterial Radioembolization Treatment of Pancreatic Cancer Patients with Liver-Dominant Metastatic Disease Using Yttrium-90 Glass Microspheres: A Single-Institution Retrospective Study. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2020;31:1060-1068. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Michl M, Haug AR, Jakobs TF, Paprottka P, Hoffmann RT, Bartenstein P, Boeck S, Haas M, Laubender RP, Heinemann V. Radioembolization with Yttrium-90 microspheres (SIRT) in pancreatic cancer patients with liver metastases: efficacy, safety and prognostic factors. Oncology. 2014;86:24-32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Damm R, Seidensticker R, Ulrich G, Breier L, Steffen IG, Seidensticker M, Garlipp B, Mohnike K, Pech M, Amthauer H, Ricke J. Y90 Radioembolization in chemo-refractory metastastic, liver dominant colorectal cancer patients: outcome assessment applying a predictive scoring system. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:509. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Salem R, Gordon AC, Mouli S, Hickey R, Kallini J, Gabr A, Mulcahy MF, Baker T, Abecassis M, Miller FH, Yaghmai V, Sato K, Desai K, Thornburg B, Benson AB, Rademaker A, Ganger D, Kulik L, Lewandowski RJ. Y90 Radioembolization Significantly Prolongs Time to Progression Compared With Chemoembolization in Patients With Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2016;151:1155-1163.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 448] [Cited by in RCA: 516] [Article Influence: 51.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (30)] |

| 12. | Ahmadzadehfar H, Biersack HJ, Ezziddin S. Radioembolization of liver tumors with yttrium-90 microspheres. Semin Nucl Med. 2010;40:105-121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 130] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Helmberger T, Golfieri R, Pech M, Pfammatter T, Arnold D, Cianni R, Maleux G, Munneke G, Pellerin O, Peynircioglu B, Sangro B, Schaefer N, de Jong N, Bilbao JI; On behalf of the CIRT Steering Committee; On behalf of the CIRT Principal Investigators. Clinical Application of Trans-Arterial Radioembolization in Hepatic Malignancies in Europe: First Results from the Prospective Multicentre Observational Study CIRSE Registry for SIR-Spheres Therapy (CIRT). Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2021;44:21-35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Nasser F, Motta Leal Filho JM, Affonso BB, Galastri FL, Cavalcante RN, Martins DLN, Segatelli V, Yamaga LYI, Gansl RC, Tranchesi Junior B, Macedo ALV. Liver Metastases in Pancreatic Acinar Cell Carcinoma Treated with Selective Internal Radiation Therapy with Y-90 Resin Microspheres. Case Reports Hepatol. 2017;2017:1847428. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Blume H, Petre EN, Ziv E, Yuan G, Rodriguez L, Sotirchos V, Zhao K, Alexander ES. Safety and efficacy of transarterial therapies for pancreatic acinar cell carcinoma metastases. Clin Imaging. 2025;121:110463. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Aguado A, Dunn SP, Averill LW, Chikwava KR, Gresh R, Rabinowitz D, Katzenstein HM. Successful use of transarterial radioembolization with yttrium-90 (TARE-Y90) in two children with hepatoblastoma. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2020;67:e28421. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Balli HT, Aikimbaev K, Guney IB, Piskin FC, Yagci-Kupeli B, Kupeli S, Kanmaz T. Trans-Arterial Radioembolization with Yttrium-90 of Unresectable and Systemic Chemotherapy Resistant Hepatoblastoma in Three Toddlers. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2022;45:344-348. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Krug S, Bartsch DK, Schober M, Librizzi D, Pfestroff A, Burbelko M, Moll R, Michl P, Gress TM. Successful selective internal radiotherapy (SIRT) in a patient with a malignant solid pseudopapillary pancreatic neoplasm (SPN). Pancreatology. 2012;12:423-427. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Dyas AR, Johnson DT, Rubin E, Schulick RD, Kumar Sharma P. Yttrium-90 selective internal radiotherapy as bridge to curative hepatectomy for recurrent malignant solid pseudopapillary neoplasm of pancreas: case report and review of literature. J Surg Case Rep. 2020;2020:rjaa325. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Gibbs P, Do C, Lipton L, Cade DN, Tapner MJ, Price D, Bower GD, Dowling R, Lichtenstein M, van Hazel GA. Phase II trial of selective internal radiation therapy and systemic chemotherapy for liver-predominant metastases from pancreatic adenocarcinoma. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:802. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Cao C, Yan TD, Morris DL, Bester L. Radioembolization with yttrium-90 microspheres for pancreatic cancer liver metastases: results from a pilot study. Tumori. 2010;96:955-958. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kim AY, Frantz S, Brower J, Akhter N. Radioembolization with Yttrium-90 Microspheres for the Treatment of Liver Metastases of Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma: A Multicenter Analysis. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2019;30:298-304.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Kim AY, Unger K, Wang H, Pishvaian MJ. Incorporating Yttrium-90 trans-arterial radioembolization (TARE) in the treatment of metastatic pancreatic adenocarcioma: a single center experience. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:492. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Nezami N, Camacho JC, Kokabi N, El-Rayes BF, Kim HS. Phase Ib trial of gemcitabine with yttrium-90 in patients with hepatic metastasis of pancreatobiliary origin. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2019;10:944-956. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Skorupan N, Arda E, Kozlov S, Alewine CC. Phase II study of olaparib in patients with advanced pancreatic acinar cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2025;43:TPS789. [DOI] [Full Text] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/