Published online Feb 21, 2026. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v32.i7.115876

Revised: December 11, 2025

Accepted: December 31, 2025

Published online: February 21, 2026

Processing time: 101 Days and 22.6 Hours

Enhancing the professionalism of physicians in diagnosing and treating Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection is crucial, given their pivotal role in the eradi

To explore the effectiveness of a single training course on H. pylori eradication the

This was a prospective, before-and-after, non-randomized interventional study based on real-world data. From March 2022 to December 2023, each physician enrolled 25 patients and acquired review outcomes, before they underwent professional training. Following this educational intervention, each physician proceeded to enroll an additional cohort of 25 patients and obtained subsequent review results for comparison. The primary outcome was a comparison of H. pylori eradication rate among gastroenterologists before and after training.

In total, 20 physicians and 1000 patients were finally analyzed. After training, the eradication rates improved significantly in both intention-to-treat analysis [58.6% vs 71.6%, odds ratio (OR) = 1.785, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.370-2.325, P < 0.001] and per-protocol analysis (81.2% vs 88.6%, OR = 1.788, 95%CI: 1.191-2.684,

A one-time training course on H. pylori eradication in physicians could improve H. pylori eradication rates, as well as therapy standardization rates and patient review rates.

Core Tip: A significant improvement in the effectiveness of Helicobacter pylori infection therapy was observed among gastroenterologists following a single structured training course, as demonstrated by this prospective, before-and-after, non-randomized interventional study based on real-world data. Following training, physicians achieved significantly higher eradication rates (58.6% vs 71.6% in intention-to-treat analysis) and improved therapy standardization. The intervention was particularly beneficial for less experienced physicians and those with historically lower success rates. These findings highlight that targeted professional education is a simple, effective strategy to improve clinical outcomes and standardize care in Helicobacter pylori eradication.

- Citation: Duan M, Kong QZ, Zuo XL, Yang XY, Li YY. Optimizing Helicobacter pylori therapy through gastroenterologist education: A prospective interventional study. World J Gastroenterol 2026; 32(7): 115876

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v32/i7/115876.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v32.i7.115876

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori), a gram-negative bacterium, can significantly affect several human systems, most notably the digestive system. In 2022, H. pylori was recognized as a class I carcinogen for gastric cancer[1]. Since the discovery of H. pylori in 1982, worldwide infection rates of H. pylori have declined from 58.2% in 1980-1990 to 43.1% in 2011-2022, attributed to the advancement of the global economy, increased attention to health, and efforts in eradication treatments spanning multiple years[2,3]. However, over the past few years, the eradication of H. pylori has emerged as a formidable challenge, despite the innovation in eradication therapies[4]. Notably, while the eradication rate of H. pylori has surpassed 90% in clinical trials, the eradication rate is not optimistic in real-world clinical practice, which drops to between 60% and 70%[5-7].

There is a discrepancy between the eradication rates of H. pylori in the real world and clinical studies[8]. The reasons for this are manifold. The patients and physicians play crucial roles as collaborative partners in the treatment of H. pylori. Physician awareness of H. pylori is vital, and is not sufficient in real world clinical practice. The efficacy of H. pylori eradication is significantly influenced by the diagnostic and treatment strategies employed by gastroenterologists, as determined by their adherence to established guidelines. In 2023, Xie et al[9] conducted a cross-sectional study that revealed various endogenous problems in prescribing H. pylori eradication, such as duplicate prescribing of drug-resistant antibiotics and the non-use of therapies recommended by eradication treatment guidelines. In 2022, Song et al[10] conducted a survey study that similarly elaborated on the deficiencies in physicians’ diagnosis, treatment, patient instruction, and follow-up of H. pylori. At the patient level, patient compliance is a prerequisite for successful H. pylori eradication[11]. Nevertheless, patient compliance largely depends on careful and conscientious patient education by the physician[12]. This underscores the importance of improving the awareness of physicians in H. pylori infection. However, there are still gaps in how to effectively conduct eradication training and assess its impact on the eradication rate. Thus, based on real-world data we designed a prospective, before-and-after, non-randomized interventional study to compare the effectiveness of a one-time training course for gastroenterologists on H. pylori eradication therapy.

This was a prospective, before-and-after, non-randomized interventional study based on real-world data. The study received approval from the Ethics Committee of Qilu Hospital and was registered with Clinicaltrials.gov under the registration number NCT05065138. All participants in the study were informed about the study details and provided their signed informed consent. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Gastroenterologists from various hospitals voluntarily participated. Data such as the age, gender, hospital and other information on the enrolled physicians were recorded. In phase I, each gastroenterologist was required to continuously record the details of 25 patients with H. pylori infection who fulfilled all inclusion criteria. In phase II, following re-evaluation of all patients, the researchers conducted training for the gastroenterologists on H. pylori eradication treatment. In phase III, following training, a further 25 patients with initial H. pylori infection were continuously recorded by each participating gastroenterologist. Throughout the study, all eradication therapies were meticulously documented without any restrictions.

A total of 21 gastroenterologists from 21 different hospitals were recruited. These physicians had to meet the following criteria: (1) Professional gastroenterology physicians; and (2) Have the capability to diagnose and treat H. pylori at their respective institutions. Physicians meeting any of the following criteria were excluded: (1) Unable or unwilling to provide informed consent; and (2) Physicians who had not previously diagnosed or treated patients with H. pylori. Physicians enrolled but who failed to complete the clinical protocol for any of the following reasons were excluded: (1) Physicians who requested withdrawal from the trial; and (2) Loss of contact.

For each participating physician, 25 patients who met the inclusion criteria were included before and after the training session, respectively. The inclusion criteria for participating patients were as follows: (1) Age 18 years or above, regard

Following enrollment in phase I, all patients received their re-evaluation results, a comprehensive training session was conducted for the participating physicians using the “2022 Chinese national clinical practice guideline on Helicobacter pylori eradication treatment” and “Management of Helicobacter pylori infection: The Maastricht VI/Florence consensus report”[13,14]. To maximize engagement and knowledge retention, the session utilized a blended learning approach, which integrated interactive lectures to deliver core knowledge, case-based discussions to solve complex clinical scenarios, and structured discussions centered on systematic analysis of practical challenges encountered in prior clinical practice.

Firstly, the training delved into the specifics of the two guidelines. Key focuses included the selection criteria for first-line therapies, with an emphasis on adapting choices to regional antibiotic resistance patterns. Additionally, precise medication dosages, treatment duration, and standardized therapies for managing adverse effects were thoroughly elucidated. Thirdly, a significant portion of time was dedicated to patient management, equipping physicians with standardized strategies for oral education and practical tools, such as medication diary cards, to enhance adherence. Furthermore, the training emphasized systematic follow-up procedures for monitoring adherence, documenting adverse drug reactions, and ensuring timely post-treatment assessment.

The primary outcome was the comparison of H. pylori eradication rates before and after the training course. To ensure the robustness of this comparison, H. pylori eradication rates were calculated using two distinct analytical methods. The intention-to-treat (ITT) population included all patients who were prescribed the eradication therapy and initiated treatment. The per-protocol (PP) population, a subset of the ITT group, comprised patients who completed the full treatment course and attended the follow-up assessment for the primary outcome. Participants with major protocol deviations, including loss to follow-up, refusal of re-examination, or poor medication adherence, were excluded from the PP analysis.

Furthermore, we classified physicians who had diagnosed and treated more than 300 cases of H. pylori infection as experienced, and those with fewer than 300 cases as inexperienced. This classification was based on an assessment of previous medical records. For the pre-training ITT analysis, an eradication rate of no less than 80% was considered high, while rates less than 80% were deemed low among the 20 physicians. Similarly, for the PP analysis, the cutoff value was set at 85%. Eradication rates within these subgroups were compared for both ITT and PP analyses.

One of the secondary study endpoints aimed to assess the therapy standardization rates among gastroenterologists before and after training. This rate was defined as the ratio of regimens that aligned with the recommendations in the Chinese guidelines for H. pylori eradication treatment to all implemented therapies[13,15]. Analyzing the patient review rate constituted another secondary endpoint. The patient review rate was defined as the proportion of patients who achieved an eradication outcome (whether successful or not), expressed as a percentage of those who signed the informed consent form. Examination of the recorded adverse event rate was identified as another secondary endpoint. This involved determining whether the adverse reactions of patients during medication were documented.

Based on previous real-world studies of H. pylori eradication treatments, the pre-training eradication rate was set at 60%, and the post-training eradication rate was anticipated to be 70%, with α set at 0.05 (bilateral) and β at 0.1[16]. The difference was assessed, and the sample size was determined using PASS 15.0.5. To achieve statistical significance, each group needed to recruit 473 participants, resulting in a total requirement of 946 participants for the two groups. To account for a 10% loss to follow-up, we planned to recruit 1040 participants in total.

Data analysis was performed using SPSS software (V26.0; IBM, Armonk, NY, United States). All demographic information, medication eradications etc. were meticulously recorded. Subsequently, all data were comprehensively described and underwent statistical testing. Data processing was facilitated using Microsoft Excel 2019 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, United States). Categorical variables are presented as n (%) while continuous variables are summarized as mean ± SD. For data not adhering to a normal distribution, we utilized the median and interquartile range for description, and employed statistical tests such as the Mann-Whitney U test and the Kruskall-Wallis H rank sum test. Pearson’s analysis was applied to categorical variables. Furthermore, Pearson’s test was utilized to evaluate changes in the eradication rate, the consistency of eradication therapies, patient review rate, and the recorded adverse event rate before and after the training course. A P value < 0.05 was considered indicative of a statistical difference. Finally, outcomes were further analyzed using logistic regression models, expressed as odds ratios (ORs) and accompanied by a 95% confidence interval (CI).

To account for the clustering effect of patients nested within physicians in the data structure, a multilevel logistic regression model was employed to further analyze patient baseline characteristics and outcome measures. In this model, the fixed effect was designated as the “training group”, while the 20 physicians were incorporated as random intercepts to capture between-physician variability. Continuous variables were analyzed using linear mixed models (LMM), and categorical variables were assessed via generalized LMMs. The results are presented as effect estimates alongside 95%CI, and a P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

This study was conducted from March 2022 to December 2023, and the training course was held on February 25, 2023. During phase II of the study, one physician withdrew from the study due to personal reasons. Complete eradication rates both before and after the training course were successfully obtained for 20 participating physicians (Supplementary Figure 1). The basic information regarding these 20 physicians is presented in Table 1. Of these, 16 (80.0%) physicians were aged 31-40 years and four (20.0%) were aged 41-50 years. There were nine male physicians (45.0%) and 11 female physicians (55.0%). Regarding education, 11 physicians (55.0%) held a bachelor’s degree, eight (40.0%) a master’s degree, and one (5.0%) a doctoral degree. In terms of professional qualifications, two (10.0%) were resident physicians, 10 (50.0%) were attending physicians or above, and eight (40.0%) were associate chief physicians. With regard to the monthly average number of H. pylori infection counseling cases, one physician (5.0%) reported fewer than five cases, five (25.0%) reported 6-10 cases, eight (40.0%) reported 11-20 cases, and six (30.0%) reported more than 20 cases. Additionally, 11 physicians (55.0%) had counseled fewer than 300 cumulative cases for H. pylori infection, while nine (45.0%) had counseled more than 300 cases.

| Variant | Result |

| Age | |

| 31-40 years old | 16 (80.0) |

| 41-50 years old | 4 (20.0) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 9 (45.0) |

| Female | 11 (55.0) |

| Education | |

| Bachelor | 11 (55.0) |

| Master | 8 (40.0) |

| Doctor and above | 1 (5.0) |

| Professional qualifications | |

| Resident physician | 2 (10.0) |

| Attending physician and above | 10 (50.0) |

| Associate chief physician | 8 (40.0) |

| Monthly average number of patients counseled for H. pylori infection | |

| Less than 5 cases | 1 (5.0) |

| 6-10 cases | 5 (25.0) |

| 11-20 cases | 8 (40.0) |

| More than 20 cases | 6 (30.0) |

| Number of patients counseled for H. pylori infection | |

| Less than 300 cases | 11 (55.0) |

| More than 300 cases | 9 (45.0) |

Due to the withdrawal of one physician in phase II, the patients enrolled in phase I were excluded. Consequently, in phases I and III, the remaining 20 physicians each included 500 patients, resulting in a total of 1000 patients. Table 2 shows the baseline characteristics of participating patients before and after training. The median age was 48.5 years in the pre-training group and 47.0 years in the post-training group. The proportion of male participants was 51.6% (pre-training) and 48.4% (post-training). The distribution of all other variables, including body mass index, smoking status, drinking habits, education level, and medical histories, was similar between the two groups, with no statistically significant differences observed (P > 0.05).

| Variant | Before training (n = 500) | After training (n = 500) | t/χ2 test | Multilevel logistic regression model | ||

| t/χ2 | P value | Coefficient/OR | P value | |||

| Age (years) | 48.5 (38.0, 58.0) | 47.0 (37.0, 57.0) | -0.934 | 0.346 | 1.034 | 0.216 |

| Sex | 1.02 | 0.312 | 0.88 | 0.312 | ||

| Male | 258 (51.6) | 242 (48.4) | ||||

| Female | 242 (48.4) | 258 (51.6) | ||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.0 (21.8, 26.2) | 24.0 (22.0, 25.7) | -0.099 | 0.921 | 0.033 | 0.871 |

| Smoking | 2.53 | 0.112 | 0.78 | 0.109 | ||

| Yes | 123 (24.6) | 102 (20.4) | ||||

| No | 377 (75.4) | 398 (79.6) | ||||

| Drinking | 2.05 | 0.152 | 0.81 | 0.150 | ||

| Yes | 143 (28.6) | 123 (24.6) | ||||

| No | 357 (71.4) | 377 (75.4) | ||||

| Education | ||||||

| Primary school | 221 (44.2) | 209 (41.8) | 1.43 | 0.489 | 1.21 | 0.239 |

| Middle school | 144 (28.8) | 139 (27.8) | 1.17 | 0.350 | ||

| College | 135 (27.0) | 152 (30.4) | ||||

| History of antibiotic allergy | 0.52 | 0.472 | 0.88 | 0.620 | ||

| Yes | 28 (5.6) | 23 (4.6) | ||||

| No | 472 (94.4) | 477 (95.4) | ||||

| Gastric cancer family history | 0.32 | 0.572 | 1.09 | 0.767 | ||

| Yes | 13 (2.6) | 16 (3.2) | ||||

| No | 487 (97.4) | 484 (96.8) | ||||

| Endoscopy | 0.07 | 0.799 | 0.96 | 0.787 | ||

| Yes | 220 (44.0) | 216 (43.2) | ||||

| No | 280 (56.0) | 284 (56.8) | ||||

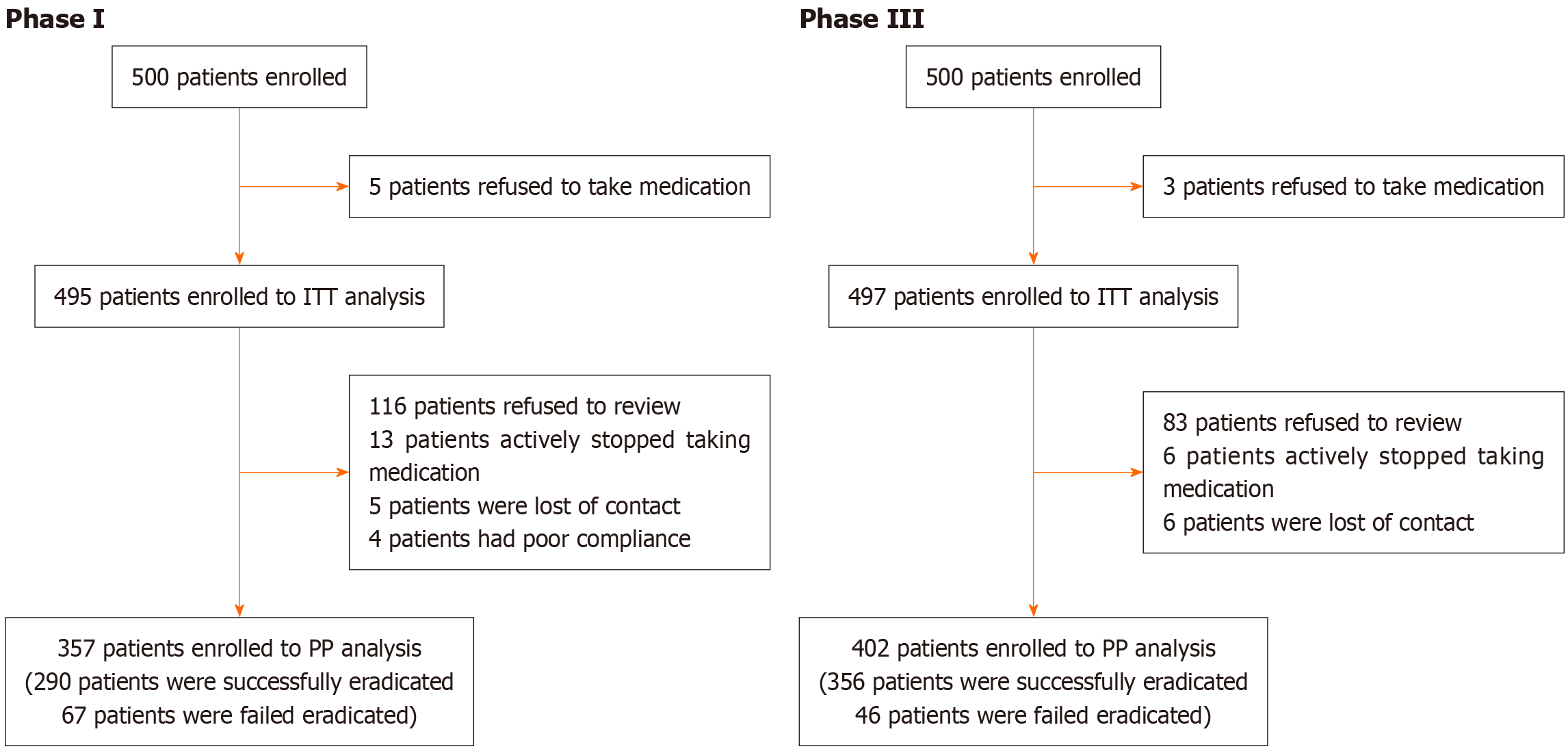

The participant flow chart summarized in Figure 1. In phase I, 500 patients were enrolled. The ITT population included 495 patients after excluding five for medication refusal. The PP population included 357 patients after further excluding 138 patients, specifically 116 refused follow-up, 13 stopped medication, five were lost to follow-up, and four cases showed poor compliance. In phase III, 500 enrolled patients yielded an ITT population of 497 after three medication refusals. The PP population was 402 after excluding 95 patients for protocol deviations, including 83 who refused follow-up, six stopped medication, and six were lost to follow-up.

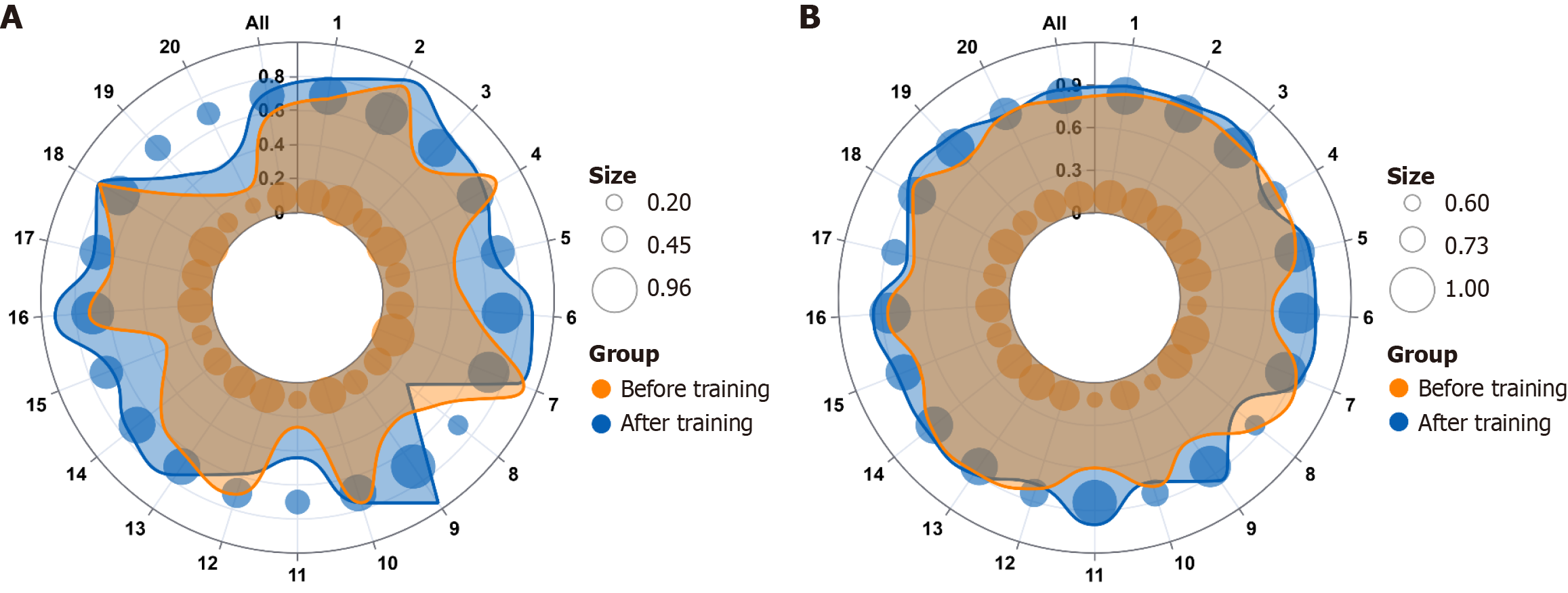

The eradication rates of the 20 physicians before and after training are detailed in Figure 2 and Supplementary Table 1, including both ITT and PP analyses. In the ITT analysis before training, eradication rates varied from 20.0% (5/25) to 92.0% (23/25) among physicians, with an overall eradication rate of 58.6% (290/495). Following training, the eradication rate for physicians ranged from 32.0% (8/25) to 96.0% (24/25), with an overall eradication rate of 71.6% (356/497). The overall eradication rate, as shown in Table 3, demonstrated a significant statistical difference (P < 0.001), with an OR of 1.785 (95%CI: 1.370-2.325). Analysis using the LMM revealed a significantly higher H. pylori eradication rate in the ITT analysis. The estimated mean increase was 0.1315 (95%CI: 0.049- 0.214, P = 0.004) compared to the pre-training period.

| Group A | Group B | χ2 test | Logistic regression model | Linear mixed model | |||||

| Before training | After training | χ2 | P value | OR | 95%CI | Effect size | 95%CI | P value | |

| H. pylori eradication rates | |||||||||

| ITT analysis | 58.59% (290/495) | 71.63% (356/497) | 18.58 | < 0.001 | 1.785 | 1.370-2.325 | 0.132 | 0.049-0.214 | 0.004 |

| PP analysis | 81.23% (290/357) | 88.56% (356/402) | 8.01 | 0.005 | 1.788 | 1.191-2.684 | 0.079 | 0.018-0.139 | 0.012 |

| Standardization rates of H. pylori eradication therapies | 71.0% (355/500) | 89.6% (448/500) | 54.57 | < 0.001 | 3.519 | 2.490-4.974 | 0.186 | 0.054-0.312 | 0.008 |

| Patient review rate | 71.4% (357/500) | 80.4% (402/500) | 11.07 | 0.001 | 1.643 | 1.225-2.204 | 0.090 | 0.031-0.149 | 0.005 |

| Adverse reaction documentation rates for physicians | 21.0% (103/490) | 21.2% (104/491) | 0.00 | 0.951 | 1.01 | 0.743-1.372 | -0.001 | -0.052-0.051 | 0.984 |

In the PP analysis before training, eradication rates ranged from 60.0% (6/10) to 92.0% (23/25) for physicians, with an overall eradication rate of 81.23% (290/357). After training, the eradication rate for physicians ranged from 66.7% (8/12) to 100.0% (11/11), with an overall eradication rate of 88.6% (356/402). The overall eradication rate, as shown in Table 3, indicated a significant statistical difference (P = 0.005), with an OR of 1.788 (95%CI: 1.191-2.684). Analysis using the LMM revealed a significantly higher H. pylori eradication rate in the PP analysis. The estimated mean increase was 0.079 (95%CI: 0.018-0.139, P = 0.012) compared to the pre-training period.

Additionally, the variation in eradication rates among physicians of different seniority levels before and after training is presented in Table 4, including both ITT and PP analyses. Based on treatment experience, the eradication rate in both ITT and PP analyses increased from 56.8% to 72.2% and from 78.7% to 86.0%, respectively, among inexperienced physicians before and after training. Experienced physicians saw improvements in their ITT and PP analysis eradication rates from 60.8% to 71.0% and from 84.4% to 91.9%, respectively. All differences were statistically significant (P < 0.05). According to the ITT analysis before training, physicians with H. pylori eradication rates below 80% experienced significant improvements in eradication after training (ITT analysis: 51.4% vs 68.3%, P < 0.001; PP analysis: 78.4% vs 88.3%, P = 0.001). Similarly, according to the PP analysis before training, physicians with eradication rates below 85% also showed significant improvements after training (ITT analysis: 45.7% vs 65.6%, P < 0.001; PP analysis: 72.7% vs 87.1%, P = 0.001).

| ITT analysis | PP analysis | |||||||

| Before training | After training | χ2 | P value | Before training | After training | χ2 | P value | |

| According to treatment experience | ||||||||

| Inexperienced physicians | 56.8% (155/273) | 72.2% (197/273) | 14.10 | < 0.001 | 78.7% (155/197) | 86.0% (197/229) | 3.98 | 0.046 |

| Experienced physicians | 60.8% (135/222) | 71.0% (159/224) | 5.14 | 0.023 | 84.4% (135/160) | 91.9% (159/173) | 4.56 | 0.033 |

| According to ITT analysis of H. pylori eradication rates before training | ||||||||

| Physicians with eradication rates below 80% | 51.4% (203/395) | 68.3% (271/397) | 23.45 | < 0.001 | 78.4% (203/259) | 88.3% (271/307) | 10.11 | 0.001 |

| Physicians with eradication rates no less than 80% | 87.0% (87/100) | 85.0% (85/100) | 0.17 | 0.684 | 88.8% (87/98) | 89.5% (85/95) | 0.02 | 0.876 |

| According to PP analysis of H. pylori eradication rates before training | ||||||||

| Physicians with eradication rates below 85% | 45.7% (112/245) | 65.6% (162/247) | 19.69 | < 0.001 | 72.7% (112/154) | 87.1% (162/186) | 10.11 | 0.001 |

| Physicians with eradication rates no less than 85% | 71.2% (178/250) | 77.6% (194/250) | 2.69 | 0.101 | 87.7% (178/203) | 89.8% (194/216) | 0.48 | 0.490 |

The therapy standardization rates before and after training are shown in Table 3 and Supplementary Table 2. Before training, therapy standardization rates among physicians varied from 0.0% to 100.0%, with five physicians exhibiting rates of less than 50%. After training, these rates ranged from 24.0% to 100.0%, with only two physicians displaying rates of less than 50%. Comparing the periods before and after training, the overall therapy standardization rates were 71.0% (355/500) and 89.6% (448/500), respectively, indicating a significant difference (P < 0.001). The OR value was 3.519 (95%CI: 2.490-4.974). A significant improvement in therapy standardization rates was observed following the training course. The LMM indicated that this increase was associated with an estimated mean difference of 0.186 (95%CI: 0.054-0.312, P = 0.008) compared to the pre-training period.

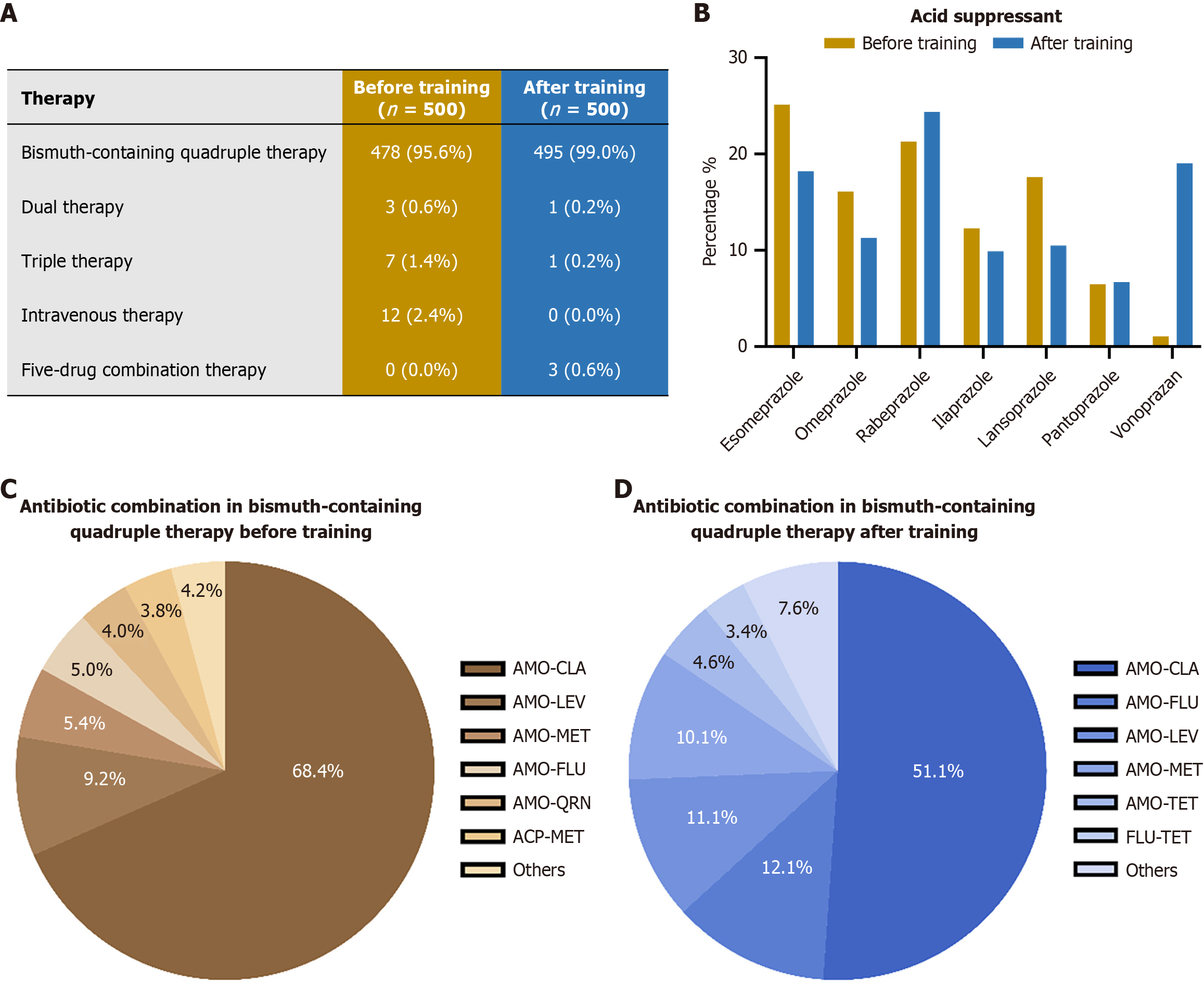

The changes in overall treatment regimens are shown in Figure 3A. Regarding the H. pylori eradication treatment therapies, following training, the utilization of bismuth-containing quadruple therapy (BcQT) increased from 95.6% (478/500) to 99.0% (495/500). Notably, the use of intravenous therapy, which is generally not recommended for routine eradication, was completely eliminated post-training (from 2.4% to 0%). Additionally, a more tailored approach was evidenced by the introduction of five-drug combination therapy in 0.6% (3/500) of cases after training, a regimen not observed prior to the intervention. Regarding the acid-suppressive drugs, the training influenced the choice of these used in BcQT (Figure 3B and Supplementary Table 3). The utilization rate of vonoprazan surged from 1.1% (5/478) before training to 19.0% (94/495) after training. Concurrently, the use of some conventional proton pump inhibitors decreased, such as esomeprazole (from 25.1% to 18.2%), omeprazole (from 16.1% to 11.3%), and lansoprazole (from 17.6% to 10.5%). Rabeprazole remained a popular choice, with a slight increase in its relative use (21.3% to 24.4%). Furthermore, the choice of antibiotic combinations in BcQT is revealed in Figure 3C and D and Supplementary Table 4. While the combination of amoxicillin-clarithromycin remained the most frequently prescribed, its prevalence decreased significantly from 68.4% (327/478) to 51.1% (253/495). There was an increased adoption of alternative regimens, such as amoxicillin-furazolidone (from 5.0% to 12.1%) and amoxicillin-levofloxacin (from 9.2% to 11.1%). Furthermore, the portfolio of antibiotic combinations broadened after training, with the emergence of several new options such as furazolidone-tetracycline (3.4%) and amoxicillin-minocycline (3.2%).

The patient review rates before and after training by physicians are detailed in Table 3 and Supplementary Table 5. Before and after training, the patient review rates were 71.4% (357/500) and 80.4% (402/500), respectively, demonstrating a statistical difference (P = 0.001). The OR value was 1.643 (95%CI: 1.225-2.204). The training intervention resulted in a significant increase in patient review rates. According to the LMM, the estimated mean difference was 0.090 (95%CI: 0.031-0.149, P = 0.005) compared to the pre-training period.

Documentation of adverse events was based on the population available for safety assessment. In phase I, 490 of 500 enrolled patients were included, after excluding five who refused medication and five who were lost to follow-up. In phase III, the analysis included 491 patients, following the exclusion of three for medication refusal and six who were lost to follow-up. The adverse reaction documentation rates before and after training by physicians are detailed in Table 3 and Supplementary Table 6. Before and after training, only two physicians had adverse reaction documentation rates of more than 50%. Following training, documentation rates showed a heterogeneous pattern of change. For some physicians, a marked increase was observed (e.g., physician 8: 20.8% to 48.0%; physician 9: 0.0% to 20.0%), while for others, the rates decreased (e.g., physician 10: 32.0% to 12.0%) or remained largely unchanged. Comparatively, before and after training, the overall adverse reaction documentation rates were 21.0% (103/490) and 21.2% (104/491), respectively, showing no statistical difference (P = 0.951). The OR value was 1.010 (95%CI: 0.743-1.372). The LMM indicated that adverse reaction documentation rates did not change significantly after training (mean difference: -0.001; 95%CI: -0.052 to 0.051; P = 0.984).

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the effectiveness of a training course by comparing H. pylori eradication rates before and after physicians received H. pylori training. In this prospective, before-and-after, non-randomized interventional study based on real-world data, we evaluated the impact of a one-time training course on H. pylori eradication, by examining changes in eradication rates, therapy standardization rates, patient review rates, and documentation of adverse reactions. Following training, a notable enhancement across all evaluated metrics was observed, with the exception of the documentation rates of adverse reactions.

Since its discovery in 1982, the focus of discussion regarding H. pylori has been on the diagnosis and treatment of the bacterium[17]. Over time, eradication guidelines have been revised in light of the emergence of antibiotic resistance in H. pylori[13,15,18]. Nevertheless, the eradication rate of H. pylori has remained at approximately 90% for some time, as reported by Zhou et al[19]. This may indicate that a plateau has been reached, which could not be elevated by modifying existing therapies or introducing novel drugs[20]. The importance of guidelines for H. pylori eradication treatment is unquestionable, yet the intricacies of the guidelines themselves present a challenge to their acceptability, comprehension, and adoption by clinicians at varying levels of expertise. Physicians can determine the best therapy after adequate understanding, for instance, BcQT is a low resistance rate antibiotic combination, or dual therapy with vonoprazan[21,22]. Thus, it is of the utmost importance to alter the prevailing mindset in order to enhance the eradication rates of H. pylori. Previous cross-sectional studies conducted by Song et al[10], Jukic et al[23], and Song et al[24] have indicated that a significant proportion of gastroenterologists lack the requisite knowledge and skills to adhere to clinical guidelines. These studies all highlighted the need for further physician training and education. In the present real-world study, prior to training, the H. pylori eradication rate for the 500 patients was only 58.6%, while therapy standardization rates were only 71.0%. It is therefore imperative that standardized training be implemented.

After undergoing just one training course, the overall H. pylori eradication rates, including both ITT and PP analyses, showed significant improvements. The standardized training demonstrated a cost-benefit ratio that is considerably more favorable than that of developing a new drug or improving an existing treatment therapy. This finding corroborates previous research. A 2019 study by Boltin et al[25], educated primary care physicians on three distinct pathways for H. pylori eradication treatment, and the findings suggested that educational activities could effectively enhance primary care physicians’ knowledge and adherence to eradication treatment guidelines. Despite a notable improvement in eradication rates among physicians in this study, these improved rates were still deemed unsatisfactory, with none reaching the 90% threshold[19]. This indicated that a solitary standardized training course on H. pylori eradication treatment is insufficient and underscores the necessity for organizing broader and more comprehensive training sessions and highlights the importance of further standardization and refinement of continuing medical education.

The benefits that physicians derive at different stages of their careers from a single standardized training vary significantly. Subgroup analysis revealed that physicians with less experience and historically lower eradication rates benefited more from training. For experienced physicians, whose treatment philosophies are already well-established, altering their practices significantly through just one training session proves challenging[26]. Similarly, physicians with a high historical eradication rate have limited potential for improvement following a one-time training course. It was observed that physicians who have accumulated experience receive comparatively less benefit from generic, one-size-fits-all training sessions. In the future, it is anticipated that tailored, comprehensive, and ongoing education training for different levels of physicians will result in further improvements.

The improvement in therapy standardization rates and the enhancement of H. pylori eradication rates occurred concurrently, further affirming the efficacy of standardized training. The key to a successful H. pylori eradication regimen lies in selecting the appropriate therapeutic strategy, combined with effective acid-suppressing drugs and antibiotics that demonstrate low regional resistance rates[4]. Prior to training, the physicians employed numerous incorrect treatment therapies. This observation aligns with previous studies which showed that the accuracy rate in choosing the correct eradication therapy and antibiotics was less than 70%[24,27]. In the present study, this training led to a marked decline in non-standard, low-efficacy regimens, specifically, triple therapy and intravenous treatment and promoted the use of BcQT, significantly improving the overall standardization of H. pylori eradication strategies. Furthermore, following training, the pronounced increase in vonoprazan use represents a meaningful advancement in optimizing therapy. As a potassium-competitive acid blocker, vonoprazan provides more potent and sustained acid suppression than conventional proton pump inhibitors[19]. This pharmacological advantage translates directly to clinical benefit by creating a gastric environment that maximizes the stability and efficacy of co-administered antibiotics, particularly acid-sensitive ones like clarithromycin and amoxicillin. This approach is especially valuable for ensuring reliable efficacy across a diverse patient population, including those with genetic variations affecting the metabolism of other acid suppressants[22]. The most clinically significant change was the strategic diversification of antibiotic combinations. The marked decrease in reliance on amoxicillin-clarithromycin therapy, coupled with the increased adoption of amoxicillin-furazolidone and other com

The adverse event documentation rate can serve as an indicator of a physician’s dedication to eradicating H. pylori[15,30]. Unfortunately, the frequency of recording adverse reactions remained low both before and after training. This low rate firstly highlights the challenges physicians face in conducting thorough follow-ups in the real world, often due to their heavy workloads. Physicians will only record the adverse reactions of patients during the clinical study. Secondly, with regard to the field of H. pylori, there has been a predominant focus on eradication rates, with less attention given to patient review rates and adverse effects[31]. As H. pylori eradication involves a combination of multiple drugs, patients often report poor treatment experiences due to the need to take several medications over the course of therapy. Therefore, the occurrence of adverse effects is frequently cited as a primary reason why patients discontinue their medication and harbor apprehensions towards treatment[26,32]. Paying increased attention to patients’ adverse drug reactions serves as an effective means to enhance medication adherence, which in turn leads to a higher eradication rate of H. pylori. This underscores the importance of encouraging physicians to diligently document patient adverse reactions and to prioritize patient follow-up as crucial components of training.

This study has several limitations. Primarily, the prospective self-controlled before-after design employed, while effective for detecting the intervention’s effect without a control group, inherently limits the ability to rule out confounding from external factors during the intervention period. Specifically, the observed improvement in H. pylori eradication rates might not solely be attributable to the training intervention. It could also be influenced by uncontrolled temporal trends such as natural changes in regional antibiotic resistance patterns, concurrent updates in clinical guidelines, or improvements in drug availability. Secondly, the absence of a control group which did not receive the training course makes it challenging to assess potential influences such as the Hawthorne effect, where physicians alter their behavior because they know they are being studied, or maturation effects, such as the natural accumulation of clinical experience over time. Collectively, these factors mean that the observed improvements cannot be attributed solely to the training program. Finally, as a pilot and small-scale study, the generalizability of its findings warrants further validation. Consequently, more rigorously designed randomized controlled trials and more extensive training initiatives will be undertaken in the future to generate higher-level evidence.

One-time training for H. pylori infection management could enhance gastroenterologists’ H. pylori eradication rates, patient review rates, and therapy standardization rates. Notably, for gastroenterologists who previously exhibited suboptimal eradication rates, the benefits of such training are even more pronounced. For the future, a multisystem, multidimensional, and sustainable approach to physician training could further enhance gastroenterologist professionalism in H. pylori infection management.

We thank the physicians from 21 hospitals and the patients who participated in the training.

| 1. | Chey WD, Leontiadis GI, Howden CW, Moss SF. ACG Clinical Guideline: Treatment of Helicobacter pylori Infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:212-239. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 744] [Cited by in RCA: 1070] [Article Influence: 118.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Li Y, Choi H, Leung K, Jiang F, Graham DY, Leung WK. Global prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection between 1980 and 2022: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;8:553-564. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 291] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Quaglia NC, Dambrosio A. Helicobacter pylori: A foodborne pathogen? World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24:3472-3487. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 4. | Moss SF, Shah SC, Tan MC, El-Serag HB. Evolving Concepts in Helicobacter pylori Management. Gastroenterology. 2024;166:267-283. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 34.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Choi YJ, Lee YC, Kim JM, Kim JI, Moon JS, Lim YJ, Baik GH, Son BK, Lee HL, Kim KO, Kim N, Ko KH, Jung HK, Shim KN, Chun HJ, Kim BW, Lee H, Kim JH, Chung H, Kim SG, Jang JY. Triple Therapy-Based on Tegoprazan, a New Potassium-Competitive Acid Blocker, for First-Line Treatment of Helicobacter pylori Infection: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Phase III, Clinical Trial. Gut Liver. 2022;16:535-546. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 14.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Chuah YY, Wu DC, Chuah SK, Yang JC, Lee TH, Yeh HZ, Chen CL, Liu YH, Hsu PI. Real-world practice and Expectation of Asia-Pacific physicians and patients in Helicobacter Pylori eradication (REAP-HP Survey). Helicobacter. 2017;22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Chen YI, Fallone CA. A 14-day course of triple therapy is superior to a 10-day course for the eradication of Helicobacter pylori: A Canadian study conducted in a 'real world' setting. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;29:e7-10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kong Q, Ju K, Li Y. Optimizing Helicobacter pylori Eradication Therapies: From Trial to Real World. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024;22:2542. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Xie J, Liu D, Peng J, Wu S, Liu D, Xie Y. Iatrogenic factors of Helicobacter pylori eradication failure: lessons from the frontline. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2023;21:447-454. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Song Z, Chen Y, Lu H, Zeng Z, Wang W, Liu X, Zhang G, Du Q, Xia X, Li C, Jiang S, Wu T, Li P, He S, Zhu Y, Zhang G, Xu J, Li Y, Huo L, Lan C, Miao Y, Jiang H, Chen P, Shi L, Tuo B, Zhang D, Jiang K, Wang J, Yao P, Huang X, Yang S, Wang X, Zhou L. Diagnosis and treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection by physicians in China: A nationwide cross-sectional study. Helicobacter. 2022;27:e12889. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kumar S, Araque M, Stark VS, Kleyman LS, Cohen DA, Goldberg DS. Barriers to Community-Based Eradication of Helicobacter pylori Infection. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024;22:2140-2142.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Fan W, Tao Y, Shi J, Ye F. Effects of New Media-Based Education on the Treatment of Helicobacter pylori Infection: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2025;27:e78387. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Zhou L, Lu H, Song Z, Lyu B, Chen Y, Wang J, Xia J, Zhao Z; on behalf of Helicobacter Pylori Study Group of Chinese Society of Gastroenterology. 2022 Chinese national clinical practice guideline on Helicobacter pylori eradication treatment. Chin Med J (Engl). 2022;135:2899-2910. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 145] [Article Influence: 36.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 14. | Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, Rokkas T, Gisbert JP, Liou JM, Schulz C, Gasbarrini A, Hunt RH, Leja M, O'Morain C, Rugge M, Suerbaum S, Tilg H, Sugano K, El-Omar EM; European Helicobacter and Microbiota Study group. Management of Helicobacter pylori infection: the Maastricht VI/Florence consensus report. Gut. 2022;gutjnl-2022. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 744] [Cited by in RCA: 848] [Article Influence: 212.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Liu WZ, Xie Y, Lu H, Cheng H, Zeng ZR, Zhou LY, Chen Y, Wang JB, Du YQ, Lu NH; Chinese Society of Gastroenterology, Chinese Study Group on Helicobacter pylori and Peptic Ulcer. Fifth Chinese National Consensus Report on the management of Helicobacter pylori infection. Helicobacter. 2018;23:e12475. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 382] [Cited by in RCA: 356] [Article Influence: 44.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 16. | Ozaki H, Harada S, Takeuchi T, Kawaguchi S, Takahashi Y, Kojima Y, Ota K, Hongo Y, Ashida K, Sakaguchi M, Tokioka S, Sakamoto H, Furuta T, Tominaga K, Higuchi K. Vonoprazan, a Novel Potassium-Competitive Acid Blocker, Should Be Used for the Helicobacter pylori Eradication Therapy as First Choice: A Large Sample Study of Vonoprazan in Real World Compared with Our Randomized Control Trial Using Second-Generation Proton Pump Inhibitors for Helicobacter pylori Eradication Therapy. Digestion. 2018;97:212-218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Warren JR, Marshall B. Unidentified curved bacilli on gastric epithelium in active chronic gastritis. Lancet. 1983;1:1273-1275. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O'Morain CA, Gisbert JP, Kuipers EJ, Axon AT, Bazzoli F, Gasbarrini A, Atherton J, Graham DY, Hunt R, Moayyedi P, Rokkas T, Rugge M, Selgrad M, Suerbaum S, Sugano K, El-Omar EM; European Helicobacter and Microbiota Study Group and Consensus panel. Management of Helicobacter pylori infection-the Maastricht V/Florence Consensus Report. Gut. 2017;66:6-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2220] [Cited by in RCA: 2088] [Article Influence: 232.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 19. | Zhou BG, Jiang X, Ding YB, She Q, Li YY. Vonoprazan-amoxicillin dual therapy versus bismuth-containing quadruple therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Helicobacter. 2024;29:e13040. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 20. | Nyssen OP, Vaira D, Pérez Aísa Á, Rodrigo L, Castro-Fernandez M, Jonaitis L, Tepes B, Vologzhanina L, Caldas M, Lanas A, Lucendo AJ, Bujanda L, Ortuño J, Barrio J, Huguet JM, Voynovan I, Lasala JP, Sarsenbaeva AS, Fernandez-Salazar L, Molina-Infante J, Jurecic NB, Areia M, Gasbarrini A, Kupčinskas J, Bordin D, Marcos-Pinto R, Lerang F, Leja M, Buzas GM, Niv Y, Rokkas T, Phull P, Smith S, Shvets O, Venerito M, Milivojevic V, Simsek I, Lamy V, Bytzer P, Boyanova L, Kunovský L, Beglinger C, Doulberis M, Marlicz W, Goldis A, Tonkić A, Capelle L, Puig I, Megraud F, Morain CO, Gisbert JP; European Registry on Helicobacter pylori Management Hp-EuReg Investigators. Empirical Second-Line Therapy in 5000 Patients of the European Registry on Helicobacter pylori Management (Hp-EuReg). Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20:2243-2257. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Suo B, Tian X, Zhang H, Lu H, Li C, Zhang Y, Ren X, Yao X, Zhou L, Song Z. Bismuth, esomeprazole, metronidazole, and minocycline or tetracycline as a first-line regimen for Helicobacter pylori eradication: A randomized controlled trial. Chin Med J (Engl). 2023;136:933-940. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Du RC, Hu YX, Ouyang Y, Ling LX, Xu JY, Sa R, Liu XS, Hong JB, Zhu Y, Lu NH, Hu Y. Vonoprazan and amoxicillin dual therapy as the first-line treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Helicobacter. 2024;29:e13039. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 23. | Jukic I, Vukovic J, Rusic D, Bozic J, Bukic J, Leskur D, Seselja Perisin A, Modun D. Adherence to Maastricht V/Florence consensus report for the management of Helicobacter pylori infection among primary care physicians and medical students in Croatia: A cross-sectional study. Helicobacter. 2021;26:e12775. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Song C, Xie C, Zhu Y, Liu W, Zhang G, He S, Zheng P, Lan C, Zhang Z, Hu R, Du Q, Xu J, Chen Y, Zeng Z, Cheng H, Wang X, Zuo X, Lu H, Guo T, Chen Z, Xie Y, Lu N. Management of Helicobacter pylori infection by clinicians: A nationwide survey in a developing country. Helicobacter. 2019;24:e12656. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Boltin D, Dotan I, Birkenfeld S. Improvement in the implementation of Helicobacter pylori management guidelines among primary care physicians following a targeted educational intervention. Ann Gastroenterol. 2019;32:52-59. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | O'Connor JP, Taneike I, O'Morain C. Improving compliance with helicobacter pylori eradication therapy: when and how? Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2009;2:273-279. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Ariño-Pérez I, Martínez-Domínguez SJ, Alfaro Almajano E, Carrera-Lasfuentes P, Lanas Á. Mistakes in the diagnosis and treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection in daily clinical practice. Helicobacter. 2023;28:e12957. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Wang L, Li Z, Tay CY, Marshall BJ, Gu B; Guangdong Center for Quality Control of Clinical Gene Testing and Study Group of Chinese Helicobacter pylori Infection and Antibiotic Resistance Rates Mapping Project (CHINAR-MAP). Multicentre, cross-sectional surveillance of Helicobacter pylori prevalence and antibiotic resistance to clarithromycin and levofloxacin in urban China using the string test coupled with quantitative PCR. Lancet Microbe. 2024;5:e512-e513. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 17.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Graham DY, Liou JM. Primer for Development of Guidelines for Helicobacter pylori Therapy Using Antimicrobial Stewardship. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20:973-983.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 22.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Nyssen OP, Perez-Aisa A, Tepes B, Castro-Fernandez M, Kupcinskas J, Jonaitis L, Bujanda L, Lucendo A, Jurecic NB, Perez-Lasala J, Shvets O, Fadeenko G, Huguet JM, Kikec Z, Bordin D, Voynovan I, Leja M, Machado JC, Areia M, Fernandez-Salazar L, Rodrigo L, Alekseenko S, Barrio J, Ortuño J, Perona M, Vologzhanina L, Romero PM, Zaytsev O, Rokkas T, Georgopoulos S, Pellicano R, Buzas GM, Modolell I, Gomez Rodriguez BJ, Simsek I, Simsek C, Lafuente MR, Ilchishina T, Camarero JG, Dominguez-Cajal M, Ntouli V, Dekhnich NN, Phull P, Nuñez O, Lerang F, Venerito M, Heluwaert F, Tonkic A, Caldas M, Puig I, Megraud F, O'Morain C, Gisbert JP; Hp-EuReg Investigators. Adverse Event Profile During the Treatment of Helicobacter pylori: A Real-World Experience of 22,000 Patients From the European Registry on H. pylori Management (Hp-EuReg). Am J Gastroenterol. 2021;116:1220-1229. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Shah SC, Bonnet K, Schulte R, Peek RM Jr, Schlundt D, Roumie CL. Helicobacter pylori Management Is Associated with Predominantly Negative Patient Experiences: Results from a Focused Qualitative Analysis. Dig Dis Sci. 2022;67:4387-4394. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Argueta EA, Moss SF. How We Approach Difficult to Eradicate Helicobacter pylori. Gastroenterology. 2022;162:32-37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/