Published online Feb 21, 2026. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v32.i7.116264

Revised: November 22, 2025

Accepted: December 29, 2025

Published online: February 21, 2026

Processing time: 92 Days and 6.8 Hours

Enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) has reshaped perioperative care in gastrointestinal oncology, but its application in elderly gastric cancer patients requires a shift from feasibility toward a biologically grounded understanding of recovery. Aging is characterized by frailty, sarcopenia, multimorbidity, chronic inflammation, and circadian vulnerability, which collectively influence post

Core Tip: Enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) has demonstrated safety and feasibility for elderly patients with gastric cancer, but feasibility alone does not define success. This editorial reframes ERAS as a pathway toward functional recovery-restoring biological resilience, metabolic homeostasis, and circadian stability while preserving independence. By integrating psychophysiological support, nutritional-inflammatory modulation, and digital monitoring, ERAS can evolve into an adaptive, precision rehabilitation model that bridges chronological age and biological potential.

- Citation: Wang G, Pan SJ. From feasibility to biological recovery: Reframing enhanced recovery pathways after surgery in elderly gastric cancer patients. World J Gastroenterol 2026; 32(7): 116264

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v32/i7/116264.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v32.i7.116264

Enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) has redefined perioperative management across gastrointestinal oncology by integrating multimodal, evidence-based elements into a coherent, team-delivered pathway[1-3]. Beyond accelerating postoperative milestones, ERAS attenuates neuroendocrine-inflammatory stress, facilitates early mobilization and nutritional repletion, and yields reproducible gains in safety, efficiency, and value across diverse settings[4,5]. Yet de

The retrospective analysis by Li et al[9] directly addresses this question in the context of gastrectomy for gastric cancer. In a cohort of 161 patients-82 aged ≥ 65 years-the authors report comparable ERAS adherence, inflammatory biomarker trajectories, and short-term outcomes between older and younger groups, without excess complications or mortality under standardized care[9]. Taken together with prior geriatric-focused series, these results counter the assumption that chronological age per se attenuates the gains of ERAS, and instead suggest that protocolized, physiology-sparing care can be delivered safely and effectively in older patients when implemented with rigor[7-9].

At the same time, not all reports are uniformly optimistic. Studies in colorectal, hepatopancreatobiliary, and mixed gastrointestinal surgery have shown that frailty, cognitive impairment, chronic inflammation, and multimorbidity may attenuate the expected gains of ERAS, leading to higher rates of postoperative complications, delayed mobilization, or failure to meet pathway milestones-even under standardized protocols[10-13]. These findings emphasize that physiologic heterogeneity-not chronological age-is the key determinant of pathway responsiveness, and that certain high-risk sub

Taken together, current evidence portrays a balanced landscape: ERAS can be delivered safely and effectively in older adults, but its impact is modulated by frailty status, baseline functional reserve, sarcopenia burden, and inflammatory load. This underscores the need to move beyond feasibility and toward a more biologically informed understanding of recovery in an aging surgical population.

Nevertheless, feasibility should be regarded as the floor, not the ceiling, of progress. As perioperative science pivots from logistics toward biology, the central question becomes: What constitutes meaningful recovery for the aging surgical body? Answering this requires a shift from measuring speed to quantifying restoration-of immune-metabolic balance, functional independence, sleep-circadian stability, and psychosocial well-being-domains that together determine long-term resilience[1-3,6].

Conventional metrics-length of stay, time to ambulation, and crude complication counts-are pragmatic but reductionist; they capture throughput, not depth of recovery[1,6]. In older adults, homeostasis is a multi-system equilibrium spanning physiology (inflammation, metabolism), function (mobility, nutrition), and mind-brain health (sleep, mood, cognition). Recovery in geriatric oncology should therefore be conceptualized as resilience reconstruction: The capacity to regain immune-metabolic equilibrium, restore circadian synchrony, and sustain autonomy in daily living after major surgical stress[14-16].

Biologically, aging is accompanied by a chronic, low-grade inflammatory tone-inflammaging-that lowers anabolic efficiency and impairs tissue repair[17]. Superimposed surgical stress can amplify catabolism, reflected by elevations in interleukin (IL)-6 and C-reactive protein (CRP) that correlate with infectious and non-infectious morbidity[14-16]. Under standardized ERAS care, Li et al[9] observed that older patients achieved inflammatory trajectories comparable to those of younger counterparts, reinforcing the principle that biologic adaptability, rather than chronological age, governs post

Operationalizing this reinterpretation entails two practical moves. First, upgrade outcome hierarchies: Retain efficiency metrics but co-primary endpoints should index host biology (e.g., resolution of inflammatory perturbation), functional reserve (nutrition, mobility), and lived experience (sleep quality, mental health)[14-16,18]. Second, align pathway levers with these endpoints: Prioritize early, targeted nutrition and anti-catabolic strategies; protect sleep-circadian integrity in the ward environment; and embed scalable psychobehavioral support-each a modulator of the same immune-metabolic network that determines recovery depth in the elderly[1,2,6,18].

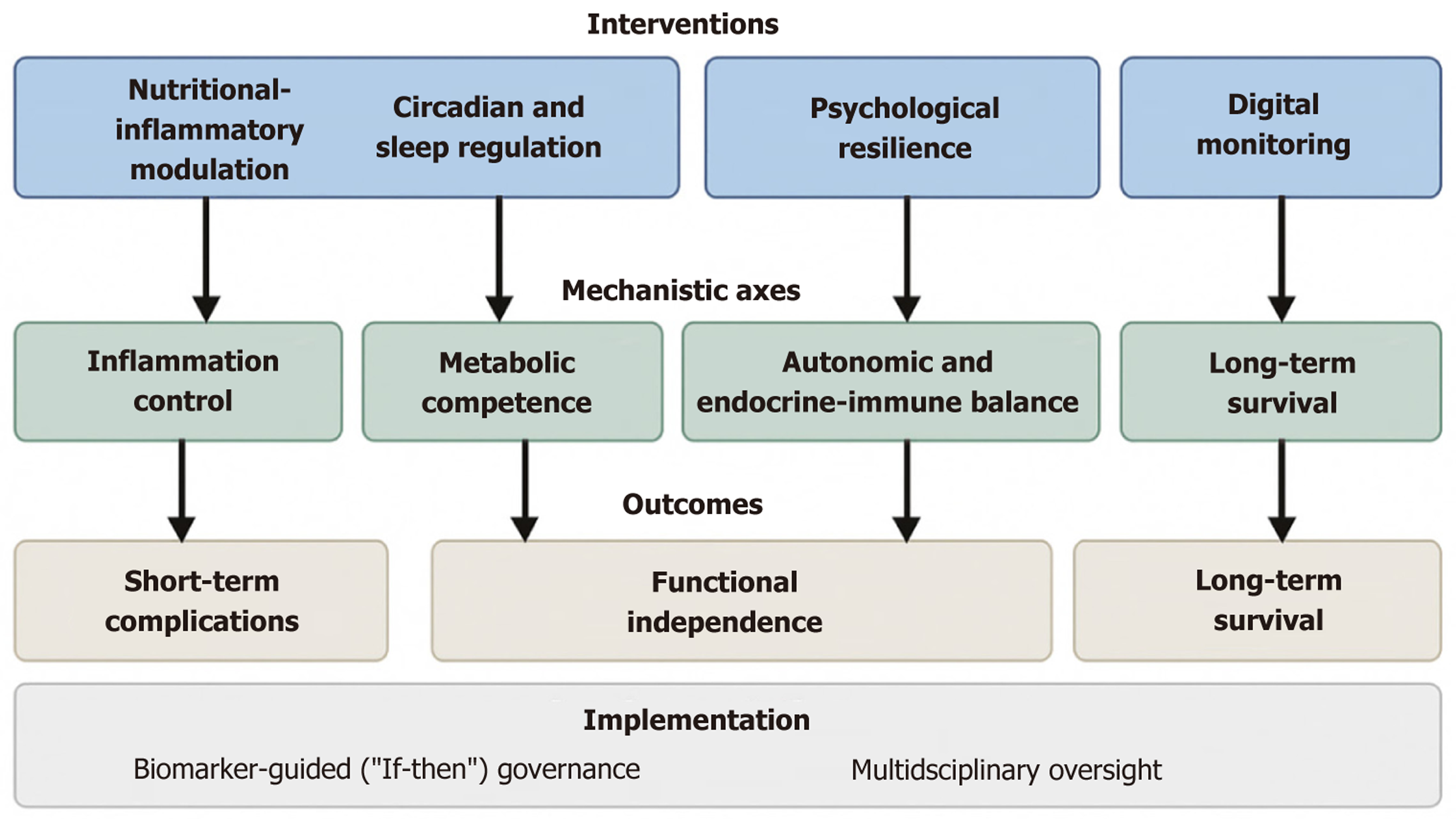

Elderly surgical patients embody a complex interface of biological frailty and psychosocial vulnerability[19-21]. Surgical recovery in this population is shaped by intersecting biological, behavioral, and environmental determinants rather than physiological stabilization alone. To evolve ERAS from feasible to transformative, perioperative pathways should address these axes simultaneously, harmonizing cellular, systemic, and psychological recovery processes. An integrative conceptual framework of these multidimensional axes and their hypothesized relationships is illustrated in Figure 1.

Malnutrition, sarcopenia, and chronic inflammation may form a reinforcing triad that undermines resilience in older adults[21,22]. Catabolism, immune suppression, and impaired wound repair share a common metabolic substrate-inefficient protein synthesis and energy imbalance. Recent prospective studies in elderly gastrointestinal surgery populations have shown that perioperative immunonutrition can modestly reduce infectious complications and support early functional recovery, particularly in patients with sarcopenia or elevated inflammatory tone[23]. Additional meta-analytic evidence from 2023 suggests that immunonutrition may shorten length of stay and improve short-term nut

Sleep architecture is a sentinel of systemic homeostasis. Circadian disruption is associated with amplified surgical inflammation, reduced insulin sensitivity, and delayed anabolism[18]. Hospital lighting/noise and nocturnal care interruptions routinely fragment sleep and may exacerbate cytokine activation. Recent clinical trials in older inpatients have dem

Psychological resilience-the adaptive capacity to restore equilibrium under stress-correlates with perioperative outcomes[28]. Anxiety, depression, and helplessness can heighten sympathetic tone and IL-6-mediated inflammation, reinforcing catabolism. Prospective studies in geriatric oncology have shown that brief perioperative psychological interventions-including structured education, coping-skills training, and narrative-based approaches-may reduce postoperative anxiety and support earlier functional mobilization[29]. Early evidence also suggests that resilience training may modulate inflammatory markers modestly in older adults undergoing major cancer surgery, though confirmatory data are required[30]. Prehabilitation strategies-narrative therapy, cognitive-behavioral interventions, and structured education-are plausible routes to down-modulate hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal-axis reactivity and support immune competence[19,20]. Integrating these modalities positions recovery as a biopsychosocial phenomenon, in which immune restoration and psychological adaptation may mutually reinforce a positive loop; causality remains to be tested.

These concepts are supported by our recent randomized trial in gastric cancer, in which combined psychological and sleep-focused interventions were associated with improved inflammatory profiles, enhanced sleep quality, and favorable oncologic outcomes[31].

Wearables quantifying sleep efficiency, mobility, and heart-rate variability (HRV) provide continuous proxies of autonomic and metabolic recovery[6]. Analytics can flag deviations from expected recovery curves ahead of overt clinical deterioration, aligning ERAS with predictive, preventive, and personalized principles[1,2,6]. Recent feasibility studies in elderly abdominal surgery patients demonstrate that step-count trajectories and HRV indices derived from consumer-grade wearables correlate with complication risk and delayed mobilization, supporting their potential role as low-burden adjuncts in perioperative monitoring[32]. To make this tractable without overstating causality, we propose if-then ope

| Trigger | Definition/threshold | Rationale/mechanistic link | Prompted action (MDT-governed) | Governance/notes |

| Autonomic-sleep dysregulation (≤ 72 hours post-op) | HRV ↓ ≥ 20% from baseline and sleep efficiency < 80% | Autonomic imbalance → sympathetic predominance → catabolic & inflammatory surge | Review analgesia/sedation timing. Activate sleep-protection bundle (timed light, noise reduction, melatonin). Screen for early delirium/uncontrolled pain (geriatric input as needed) | Process prompt; not therapeutic. Requires prospective validation |

| Reduced mobility trajectory (POD 2-5) | Step-count ↓ ≥ 30% from prior day or below ward target ≥ 48 hours | Impaired recovery reserve → pulmonary and thrombotic risk | Escalate physiotherapy/mobilization. Reassess nutrition (protein ≥ 1.2 g/kg). Check orthostatic vitals | Needs wearable or nurse-logged data; align with ERAS mobility KPIs |

| Metabolic stress signature (any time) | Resting nocturnal HR ↑ ≥ 10 bpm for ≥ 2 nights plus appetite decline | Hypermetabolic state; low-grade inflammation; energy deficit | Rule out infection/pain. Review fluid/glucose management. Consider early immunonutrition based on PINI trend | MDT review trigger; actions supervised jointly by surgical, geriatric, and nutrition teams |

| Inflammatory-nutritional deviation (POD 3-7) | PINI > 1 or PNI < 40 or CRP > 50 mg/L persistent ≥ 48 hours | Sustained inflammation & malnutrition predict delayed recovery | Initiate targeted nutrition (ω-3, arginine, nucleotides). Evaluate infection source. Recheck markers in 48 hours | Exploratory markers; standardization needed for multicenter use |

| Behavioral-psychological distress (pre- or early post-op) | HADS-A ≥ 8 or PHQ-9 ≥ 10 | Psychological stress → HPA activation → IL-6 ↑ → impaired healing | Initiate CBT/narrative-based support. Arrange mental-health professional review. Consider IL-6 monitoring if available | Optional; integrate with perioperative mental-health resources under psychology/geriatric oversight |

Trigger A (within 72 hours post-op): HRV (time-domain metric) decreases ≥ 20% from individual baseline and nocturnal sleep efficiency < 80% → Action: Review analgesia/sedation timing; initiate or upgrade the sleep-protection bundle (timed light, noise control, melatonin); assess for uncontrolled pain or early delirium risk (screen only).

Trigger B (post-op days 2-5): Step-count trajectory falls ≥ 30% from the prior day or fails to reach ward target for 48 hours → Action: Escalate physiotherapy and mobilization goals; reassess nutrition (protein/energy adequacy); check orthostatic vitals.

Trigger C (any time): Resting nocturnal heart rate ≥ 10 bpm above baseline for two consecutive nights with appetite score decline → Action: Rule-out infection/pain, review fluid balance, and consider early immunonutrition supplement pending PINI/CRP trends.

These triggers are process prompts, not outcome guarantees; they should operate within a continuous quality-imp

The success of ERAS has long been gauged by compliance rates-how closely clinicians adhere to standardized elements[9]. While essential for quality assurance, compliance is a surrogate, not a destination. The true benchmark should be bio

A next-generation model of precision rehabilitation envisions a continuous feedback loop linking host biology, patient behavior, and system adaptation. Serial monitoring of inflammatory markers (IL-6, CRP, albumin), behavioral metrics (sleep efficiency, mobility), and psychometric scores (resilience, fatigue) can generate individualized recovery trajectories[14-16,18]. Predictive algorithms can then flag stagnation or regression, prompting targeted adjustments-more intensive nutritional support, revised mobilization pacing, or psychological reinforcement[19-21].

In this vision, MDT-surgeons, anesthesiologists, geriatricians, nutritionists, psychologists, and data scientists-operate not in silos but as an ecosystem of recovery engineering[1,2,6]. ERAS thus evolves from a protocol to an adaptive system, guided by continuous physiologic intelligence.

Despite its conceptual appeal, operationalizing an adaptive and biologically informed ERAS pathway in an aging society presents several practical challenges. First, implementation requires substantial clinical bandwidth: Nursing workload, geriatric assessment, structured sleep protection, and nutritional optimization all demand time and coor

Addressing these barriers will require incremental innovation rather than wholesale redesign. Scalable approaches-such as simplified frailty screening, targeted sleep-protection bundles, basic wearable metrics (step count, nocturnal heart rate), and brief psychological support-may offer high-yield entry points that align with existing ERAS elements. As population aging accelerates globally, the evolution of ERAS will hinge on its ability to accommodate physiologic div

Global research trends, highlighted through Reference Citation Analysis, reveal four converging trajectories redefining perioperative science[1,4,6,9]: (1) Inflammation-based prognostic modeling, quantifying the host response as a therapeutic target; (2) Nutritional and sarcopenic optimization, reframing recovery through metabolic competence; (3) Psychophysiological and circadian interventions, uniting mental health with immunologic recalibration; and (4) Digital precision monitoring, operationalizing recovery through continuous data analytics.

Li et al’s findings[9] reinforce the first pillar-validating the physiologic tolerance of ERAS in the elderly-and indirectly affirm the others, demonstrating that aging biology can accommodate complex, multimodal recovery frameworks with

Persisting exclusion of older adults from intensive perioperative programs reflects a vestige of ageism rooted in outdated assumptions of fragility[7-9]. The evidence by Li et al[9] dismantles this bias: Age alone is a poor surrogate for recovery potential. Physiologic age-quantified through frailty indices, sarcopenia scores, and inflammatory load-offers a more rational basis for personalization[21,22].

From an ethical standpoint, the future of ERAS must prioritize inclusivity-designing adaptive frameworks that accommodate physiologic heterogeneity rather than restricting participation because of it[6,9,25,28]. The elderly, heterogeneous yet resilient, should be reimagined not as the limits of surgical possibility but as the testing ground for perioperative innovation. Their outcomes will ultimately define whether modern surgery can deliver humane precision me

The study by Li et al[9] represents a pivotal inflection point in ERAS evolution. By proving that standardized, evidence-based recovery pathways are safe and feasible for elderly gastric cancer patients, it dissolves the conceptual ceiling that age equates to vulnerability. The future imperative is clear: Elevate ERAS from procedural compliance to a biologically intelligent, patient-centered paradigm that restores not merely function but wholeness.

In this reframed paradigm, recovery transcends the linear journey from operation to discharge. It becomes a dynamic continuum of reintegration-encompassing immune equilibrium, metabolic vitality, cognitive clarity, and emotional stea

ERAS began as a revolution in perioperative logistics; its next revolution must be in meaning. The true measure of success will no longer be hours saved but lives restored to harmony and dignity.

The author extends sincere appreciation to Li JY, Ge MM, Pan HF, and Jiang ZW for their valuable contributions to the evidence base of ERAS in elderly gastric cancer patients.

| 1. | Ljungqvist O, Scott M, Fearon KC. Enhanced Recovery After Surgery: A Review. JAMA Surg. 2017;152:292-298. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1487] [Cited by in RCA: 2429] [Article Influence: 269.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Kehlet H. Multimodal approach to control postoperative pathophysiology and rehabilitation. Br J Anaesth. 1997;78:606-617. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1691] [Cited by in RCA: 1817] [Article Influence: 62.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 3. | Mortensen K, Nilsson M, Slim K, Schäfer M, Mariette C, Braga M, Carli F, Demartines N, Griffin SM, Lassen K; Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS®) Group. Consensus guidelines for enhanced recovery after gastrectomy: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS®) Society recommendations. Br J Surg. 2014;101:1209-1229. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 386] [Cited by in RCA: 547] [Article Influence: 45.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Wang LH, Zhu RF, Gao C, Wang SL, Shen LZ. Application of enhanced recovery after gastric cancer surgery: An updated meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24:1562-1578. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Beamish AJ, Chan DS, Blake PA, Karran A, Lewis WG. Systematic review and meta-analysis of enhanced recovery programmes in gastric cancer surgery. Int J Surg. 2015;19:46-54. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Jung MR, Ryu SY, Park YK, Jeong O. Compliance with an Enhanced Recovery After a Surgery Program for Patients Undergoing Gastrectomy for Gastric Carcinoma: A Phase 2 Study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2018;25:2366-2373. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Xiao SM, Ma HL, Xu R, Yang C, Ding Z. Enhanced Recovery After Surgery protocol for elderly gastric cancer patients: A prospective study for safety and efficacy. Asian J Surg. 2022;45:2168-2171. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Cao S, Zheng T, Wang H, Niu Z, Chen D, Zhang J, Lv L, Zhou Y. Enhanced Recovery after Surgery in Elderly Gastric Cancer Patients Undergoing Laparoscopic Total Gastrectomy. J Surg Res. 2021;257:579-586. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Li J, Ge M, Pan H, Wang G, Jiang Z. Feasibility and safety of enhanced recovery after surgery in elderly patients with gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2025;31. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | McGinn R, Agung Y, Grudzinski AL, Talarico R, Hallet J, McIsaac DI. Attributable Perioperative Cost of Frailty after Major, Elective Noncardiac Surgery: A Population-based Cohort Study. Anesthesiology. 2023;139:143-152. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Lee C, Mabeza RM, Verma A, Sakowitz S, Tran Z, Hadaya J, Lee H, Benharash P. Association of frailty with outcomes after elective colon resection for diverticular disease. Surgery. 2022;172:506-511. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | STARSurg Collaborative; EuroSurg Collaborative. Association between multimorbidity and postoperative mortality in patients undergoing major surgery: a prospective study in 29 countries across Europe. Anaesthesia. 2024;79:945-956. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 13. | Suraarunsumrit P, Srinonprasert V, Kongmalai T, Suratewat S, Chaikledkaew U, Rattanasiri S, McKay G, Attia J, Thakkinstian A. Outcomes associated with postoperative cognitive dysfunction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Age Ageing. 2024;53:afae160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Shi J, Wu Z, Wang Q, Zhang Y, Shan F, Hou S, Ying X, Huangfu L, Li Z, Ji J. Clinical predictive efficacy of C-reactive protein for diagnosing infectious complications after gastric surgery. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2020;13:1756284820936542. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | van Winsen M, McSorley ST, McLeod R, MacDonald A, Forshaw MJ, Shaw M, Puxty K. Postoperative C-reactive protein concentrations to predict infective complications following gastrectomy for cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2021;124:1060-1069. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Desborough JP. The stress response to trauma and surgery. Br J Anaesth. 2000;85:109-117. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1231] [Cited by in RCA: 1336] [Article Influence: 51.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Franceschi C, Garagnani P, Parini P, Giuliani C, Santoro A. Inflammaging: a new immune-metabolic viewpoint for age-related diseases. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2018;14:576-590. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1183] [Cited by in RCA: 2211] [Article Influence: 276.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (9)] |

| 18. | Irwin MR, Olmstead R, Carroll JE. Sleep Disturbance, Sleep Duration, and Inflammation: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Cohort Studies and Experimental Sleep Deprivation. Biol Psychiatry. 2016;80:40-52. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1387] [Cited by in RCA: 1457] [Article Influence: 145.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Chen X, Li K, Yang K, Hu J, Yang J, Feng J, Hu Y, Zhang X. Effects of preoperative oral single-dose and double-dose carbohydrates on insulin resistance in patients undergoing gastrectomy:a prospective randomized controlled trial. Clin Nutr. 2021;40:1596-1603. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Talutis SD, Lee SY, Cheng D, Rosenkranz P, Alexanian SM, McAneny D. The impact of preoperative carbohydrate loading on patients with type II diabetes in an enhanced recovery after surgery protocol. Am J Surg. 2020;220:999-1003. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Sun G, Li Y, Peng Y, Lu D, Zhang F, Cui X, Zhang Q, Li Z. Impact of the preoperative prognostic nutritional index on postoperative and survival outcomes in colorectal cancer patients who underwent primary tumor resection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2019;34:681-689. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Chen F, Chi J, Liu Y, Fan L, Hu K. Impact of preoperative sarcopenia on postoperative complications and prognosis of gastric cancer resection: A meta-analysis of cohort studies. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2022;98:104534. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Lin Z, Yan M, Lin Z, Xu Y, Zheng H, Peng Y, Li Y, Yang C. Short-term outcomes of distal gastrectomy versus total gastrectomy for gastric cancer under enhanced recovery after surgery: a propensity score-matched analysis. Sci Rep. 2024;14:17594. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Matsui R, Sagawa M, Sano A, Sakai M, Hiraoka SI, Tabei I, Imai T, Matsumoto H, Onogawa S, Sonoi N, Nagata S, Ogawa R, Wakiyama S, Miyazaki Y, Kumagai K, Tsutsumi R, Okabayashi T, Uneno Y, Higashibeppu N, Kotani J. Impact of Perioperative Immunonutrition on Postoperative Outcomes for Patients Undergoing Head and Neck or Gastrointestinal Cancer Surgeries: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Ann Surg. 2024;279:419-428. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Jeong O, Jang A, Jung MR, Kang JH, Ryu SY. The benefits of enhanced recovery after surgery for gastric cancer: A large before-and-after propensity score matching study. Clin Nutr. 2021;40:2162-2168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Matsuura Y, Ohno Y, Toyoshima M, Ueno T. Effects of non-pharmacologic prevention on delirium in critically ill patients: A network meta-analysis. Nurs Crit Care. 2023;28:727-737. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Chen P, Song H, Xu W, Guo J, Wang J, Zhou J, Kang X, Jin C, Cai Y, Feng Z, Gao H, Lu F, Li L. Corrigendum: Validation of the GALAD model and establishment of a new model for HCC detection in Chinese patients. Front Oncol. 2023;13:1170066. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Wang G, Pan S. Synergistic Effects of Psychological Resilience Training and Nutritional Support on Postoperative Recovery, Nutritional Reconstitution, Sleep Quality, and Long-Term Survival in Gastric Cancer: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Ann Surg Oncol. 2025. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Włodarczyk J. Molecular Mechanisms and Clinical Implications of Complex Prehabilitation in Colorectal Cancer Surgery: A Comprehensive Review. Int J Mol Sci. 2025;26:7242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Chou YJ, Lee YH, Lin BR, Jiang JK, Yang HY, Lin HY, Shun SC. Serial multiple mediation model of fear of cancer recurrence in patients with colorectal cancer. Health Psychol. 2025;44:955-962. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Wang G, Pan S. Psychological Interventions and Sleep Improvement for Patients with Gastric Cancer: Effects on Immune Function, Inflammation, and Tumor Progression-A Randomized Controlled Trial. Ann Surg Oncol. 2025;32:6858-6876. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Wells CI, Xu W, Penfold JA, Keane C, Gharibans AA, Bissett IP, O'Grady G. Wearable devices to monitor recovery after abdominal surgery: scoping review. BJS Open. 2022;6:zrac031. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/