Published online Feb 21, 2026. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v32.i7.115406

Revised: December 2, 2025

Accepted: December 26, 2025

Published online: February 21, 2026

Processing time: 109 Days and 5.9 Hours

Primary intestinal (PI) diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) represents a bio

To investigate whether intestinal laterality influences survival in PI-DLBCL and construct a location-integrated prognostic nomogram.

We retrospectively analyzed 3832 PI-DLBCL patients (SEER 2002-2021) and externally validated in 107 patients (Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center 2014-2024). A prognostic nomogram integrating age, Ann Arbor stage, chemotherapy, surgery, and tumor sidedness (left vs right of the splenic flexure) was constructed. To mitigate treatment-selection bias, we additionally performed propensity score matching (PSM) for left- vs right-sided PI-DLBCL.

Left-sided PI-DLBCL was independently associated with inferior overall survival (OS) (hazard ratio = 1.15, P = 0.035) and the association persisted after PSM. When compared with intra-abdominal N-DLBCL, right-sided PI-DLBCL showed superior OS, whereas left-sided PI-DLBCL had worse OS. The nomogram achieved superior discrimination vs the IPI (C-index: 0.749 vs 0.710) and higher time-dependent area under the curves (1-year: 0.865 vs 0.753; 2-year: 0.792 vs 0.731; 3-year: 0.786 vs 0.727) in the external validation cohort. The nomogram stratified patients into low-, median-, and high-risk groups with clear OS separation in both the training and external cohorts.

Intestinal laterality is an independent, clinically actionable determinant of survival in PI-DLBCL. The proposed nomogram provides individualized survival prediction and risk stratification and showed higher discrimination than the IPI, supporting the incorporation of tumor anatomical location into prognostic assessment and risk-adapted management.

Core Tip: This study identifies intestinal laterality (left vs right of the splenic flexure) as a key, previously overlooked prognostic factor in primary intestinal diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL): Left-sided disease confers worse overall survival, whereas right-sided disease even surpasses intra-abdominal nodal DLBCL. Leveraging SEER (n = 3832) and an external validation cohort (n = 107), we built and validated a simple nomogram (age, stage, chemotherapy, surgery, laterality) that delivered higher discrimination than the international prognostic index. The model operationalizes tumor location for individualized prognosis and may inform risk-adapted clinical decisions.

- Citation: Zeng RX, Wang CQ, Yang H, Sun P, Liu PP, Wei LC, Chen TT, Wang Z, Huang H, Li ZM, Tian XP, Wang Y. Anatomical laterality of primary intestinal diffuse large B-cell lymphoma independently stratifies survival: New prognostic nomogram incorporating tumor location. World J Gastroenterol 2026; 32(7): 115406

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v32/i7/115406.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v32.i7.115406

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most common non-Hodgkin lymphoma, yet clinical behavior varies markedly across primary sites[1]. Primary extranodal involvement is seen in approximately 30% of cases, with the gastrointestinal (GI) tract being the most common site[2,3]. Primary intestinal (PI)-DLBCL, involving the small intestine and colon, represents a distinct clinical entity with unique diagnostic and therapeutic challenges, yet its site-specific prognostic features remain incompletely characterized. However, the international prognostic index (IPI), derived from predominantly nodal DLBCL (N-DLBCL), does not incorporate intestinal laterality and is not tailored to PI-DLBCL. Although several SEER-based studies have proposed nomograms for intestinal lymphoma, most have not explicitly incorporated intraluminal anatomical location as a prognostic variable. Moreover, most existing studies treat the GI tract as a homogeneous entity, with limited exploration of spatial heterogeneity in outcomes[4-7].

In colorectal carcinoma, anatomical laterality relative to the splenic flexure is a robust prognostic determinant: Right-sided tumors often display inferior outcomes and distinct molecular profiles compared with left-sided lesions[8,9]. These differences are rooted in embryologic origin (midgut vs hindgut), divergent microbiota, and immune microenvironment composition[9]. Whether a comparable left-right survival disparity exists in PI-DLBCL remains entirely unexplored.

We therefore hypothesized that intestinal laterality (left vs right of the splenic flexure) may be associated with overall survival (OS) in PI-DLBCL, a question that has not been systematically investigated. Accordingly, we: (1) Quantified the prognostic impact of left- vs right-sided PI-DLBCL; (2) Developed and externally validated a laterality-integrated nomo

This retrospective study was designed to develop and externally validate a prognostic model for PI-DLBCL, with a specific focus on the impact of anatomical tumor location defined by the splenic flexure on patient outcomes.

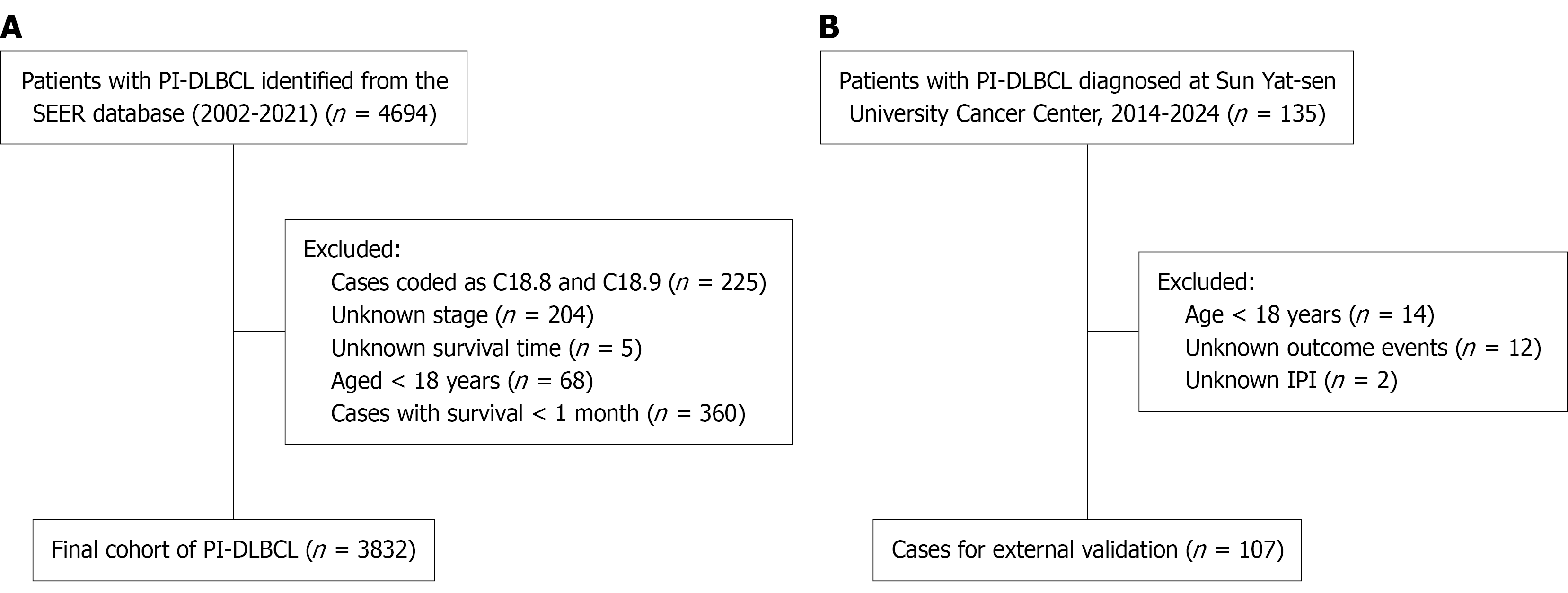

We conducted a retrospective, population-based training-cohort study. Data were obtained from the SEER-17 registry using SEER Stat software (version 8.4.4), covering cases diagnosed from 2002 to 2021. DLBCL was identified using International Classification of Disease for Oncology-3 (ICD-O-3) histology code 9680. PI-DLBCL was defined as lymphoma arising in the intestinal tract, with primary site codes C17.0-C20.9. ICD-O-3 topography codes were mapped to right- and left-sided groups using the splenic flexure as the anatomical border (Supplementary Table 1). Duodenum, jejunum, ileum, small intestine nitric oxide synthase (NOS), cecum, appendix, ascending colon, hepatic flexure and transverse colon (C17.0-C17.9, C18.0-C18.4) were classified as right-sided, whereas splenic flexure to rectum (C18.5-C20.9) were classified as left-sided. Cases coded as C18.8 (overlapping lesion of colon) and C18.9 (colon, NOS) were excluded a priori because laterality could not be determined. Details of the case-selection process and the mapping of ICD-O-3 topography codes to right- and left-sided disease are shown in Figure 1 and Supplementary Table 1. To serve as a comparison group, primary intra-abdominal N-DLBCL was also included, defined by the primary site code C77.2. Patients were excluded if they had unknown Ann Arbor stage, missing survival data, a survival time of less than one month, or were under 18 years of age at diagnosis.

An independent validation cohort of 107 patients diagnosed with PI-DLBCL between January 2014 and December 2024 at Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center was retrospectively collected using the same inclusion and exclusion criteria. All cases were confirmed by pathology, and data were extracted from hospital records. Informed consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study.

The following eight clinical variables were included in the analysis: Age at diagnosis, sex, primary tumor location, Ann Arbor stage, race, receipt of chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and surgical treatment. To evaluate the effect of anatomical location on prognosis, tumor sites were categorized as right-sided (duodenum to transverse colon) and left-sided (splenic flexure to rectum), using the splenic flexure as the anatomical boundary, analogous to classifications used in colorectal cancer studies. The primary outcome was OS, defined as the time from diagnosis to death from any cause. Patients alive at the last follow-up were censored.

Categorical variables were compared using the χ2 test, and continuous variables were assessed with the t-test. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate survival probabilities, and differences between groups were assessed using the log-rank test.

To contextualize laterality, we prespecified a benchmarking approach in the SEER cohort using intra-abdominal N-DLBCL as a reference: (1) Left-sided PI-DLBCL vs N-DLBCL; and (2) Right-sided PI-DLBCL vs N-DLBCL, followed by a direct left- vs right-sided comparison within PI-DLBCL. These comparisons were intended to screen for spatial heterogeneity before formal modeling of laterality.

To reduce confounding in the left- vs right-sided comparison within the SEER cohort, propensity scores were estimated by logistic regression (MatchIt package, R) with key baseline covariates. We then performed 1:3 nearest-neighbor matching with replacement, using a caliper width of 0.20 times the standard deviation of the logit of the propensity score to match each left-sided case to right-sided controls. Covariate balance was evaluated using standardized mean differences (SMDs) for all baseline variables, with |SMD| < 0.10 considered acceptable. Survival analyses (Kaplan-Meier) were repeated in the matched cohort as a sensitivity analysis.

Univariable Cox proportional hazards regression was initially performed to evaluate the association between each variable and OS. Variables with P < 0.05 were entered into a multivariable Cox regression model to identify independent prognostic factors. Hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were reported. Results from the multivariable model were displayed using a forest plot.

A prognostic nomogram was constructed based on the multivariate Cox model using the rms package in R. The nomogram generated point-based predictions of 1-, 2-, and 3-year OS. Model performance was assessed using the C-index and time-dependent receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves, both in the training cohort (SEER) and the external validation cohort (Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center), and was compared with the IPI in the external cohort using the same metrics. Calibration plots were used to assess agreement between predicted and observed survival. For clinical stratification, we applied X-tile to the total nomogram score in the training cohort to identify two optimal cut-offs, thereby defining low-, median-, and high-risk groups; the same cut-offs were applied unchanged to the external validation cohort. Kaplan-Meier curves and log-rank tests were used to assess survival separation across the nomogram-defined risk groups. All analyses were performed using R software (version 4.4.1), with two-sided P values < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

A total of 3832 patients with PI-DLBCL were included from the SEER database, comprising 474 (12.4%) with left-sided tumors and 3358 (87.6%) with right-sided tumors. Baseline characteristics between the two groups are summarized in Table 1. The median age at diagnosis was 69 years, and most patients were white. The age distribution was generally comparable between groups, with the majority of patients in both cohorts aged 70-89 years (47.5% in the left-sided group vs 44.2% in the right-sided group). The proportion of younger patients (< 50 years) was similarly low in both groups (13.5% vs 14.7%). In terms of treatment, patients with right-sided tumors were more likely to receive chemotherapy (73.9% vs 69.4%) and surgical intervention (66.3% vs 38.4%). Additionally, early-stage disease (Ann Arbor stage I/II) was more frequent in the right-sided group (73.4%) than in the left-sided group (70.9%). The gender distribution was similar between groups, with males comprising the majority (62.4% right-sided vs 62.9% left-sided). After propensity score matching (PSM), 474 left-sided and 1063 right-sided cases were retained in a 1:3 matched cohort, and baseline characteristics between groups were well balanced, with all |SMD| < 0.10 (Table 1; Supplementary Figure 1).

| Characteristics | Before propensity score matching | After propensity score matching | ||||

| Right side (n = 3358) | Left side (n = 474) | SMD | Right side (n = 1063) | Left side (n = 474) | SMD | |

| Age | 0.071 | 0.004 | ||||

| < 50 | 493 (14.7) | 64 (13.5) | 155 (14.6) | 64 (13.5) | ||

| 50-69 | 1269 (37.8) | 168 (35.4) | 396 (37.3) | 168 (35.4) | ||

| 70-89 | 1486 (44.2) | 225 (47.5) | 477 (44.9) | 225 (47.5) | ||

| ≥ 90 | 110 (3.3) | 17 (3.6) | 35 (3.3) | 17 (3.6) | ||

| Gender | 0.010 | 0.006 | ||||

| Female | 1263 (37.6) | 176 (37.1) | 396 (37.3) | 176 (37.1) | ||

| Male | 2095 (62.4) | 298 (62.9) | 667 (62.7) | 298 (62.9) | ||

| Race | 0.060 | 0.039 | ||||

| White | 2787 (83.0) | 403 (85.0) | 889 (83.6) | 403 (85.0) | ||

| Black | 177 (5.3) | 24 (5.1) | 55 (5.2) | 24 (5.1) | ||

| Other | 394 (11.7) | 47 (9.9) | 119 (11.2) | 47 (9.9) | ||

| Stage | 0.056 | < 0.001 | ||||

| Stage I/II | 2464 (73.4) | 336 (70.9) | 749 (70.5) | 336 (70.9) | ||

| Stage III/IV | 894 (26.6) | 138 (29.1) | 314 (29.5) | 138 (29.1) | ||

| Radiation | 0.284 | 0.002 | ||||

| Yes | 192 (5.7) | 67 (14.1) | 128 (12.0) | 67 (14.1) | ||

| No/unknown | 3166 (94.3) | 407 (85.9) | 935 (88.0) | 407 (85.9) | ||

| Surgery | 0.581 | 0.001 | ||||

| Yes | 2225 (66.3) | 182 (38.4) | 477 (44.9) | 182 (38.4) | ||

| No | 1133 (33.7) | 292 (61.6) | 586 (55.1) | 292 (61.6) | ||

| Chemotherapy | 0.099 | 0.002 | ||||

| Yes | 2481 (73.9) | 329 (69.4) | 760 (71.5) | 329 (69.4) | ||

| No/unknown | 877 (26.1) | 145 (30.6) | 303 (28.5) | 145 (30.6) | ||

In the external validation cohort from Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center (n = 107), 101 patients (94.4%) received first-line rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP) or R-CHOP-like rituximab-containing chemotherapy, 4 (3.7%) received other rituximab-based regimens, and 2 patients (1.9%) did not receive systemic chemotherapy. Surgery was performed in 65 patients (60.7%) and radiotherapy in 3 patients (2.8%) (Sup

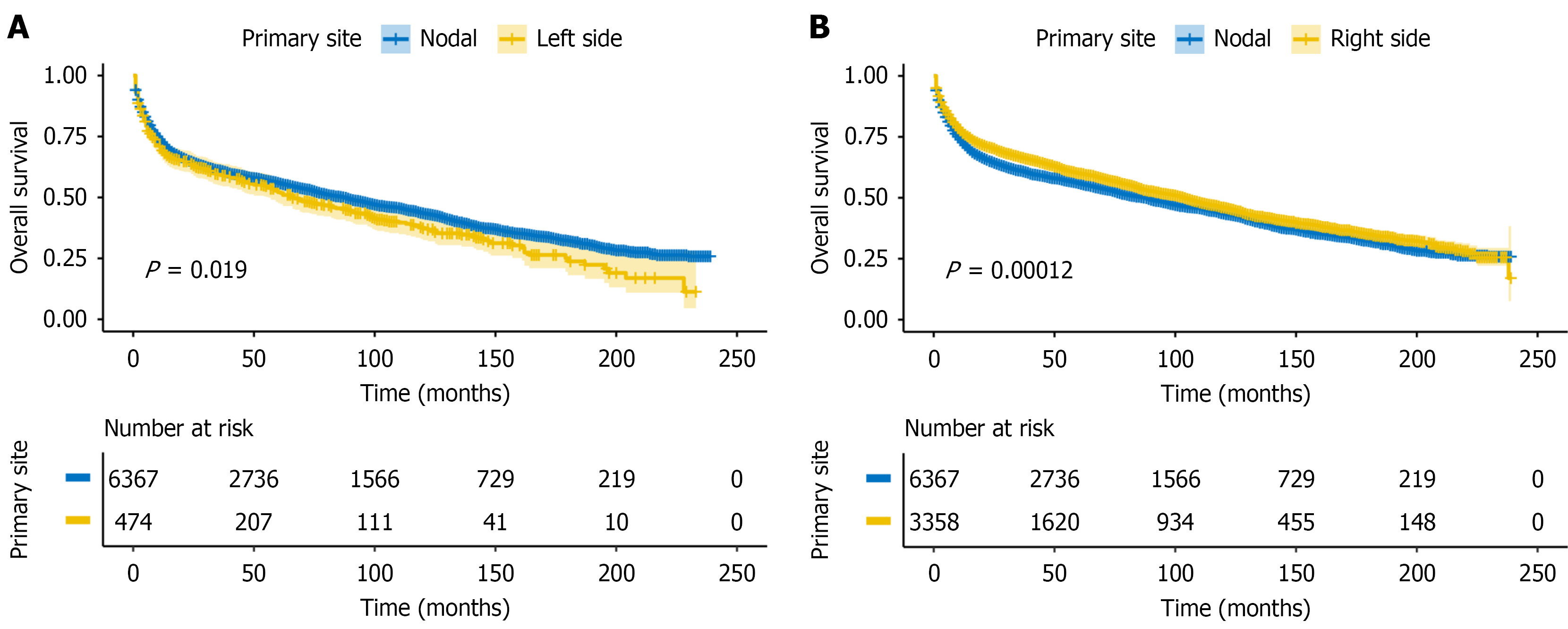

To evaluate whether anatomical location influences prognosis, we first compared the OS of patients with left-sided and right-sided PI-DLBCL to those with primary intra-abdominal N-DLBCL. Left-sided PI-DLBCL showed significantly worse OS than N-DLBCL (log-rank P = 0.019; Figure 2A), while right-sided PI-DLBCL demonstrated significantly better OS than N-DLBCL (log-rank P < 0.001; Figure 2B).

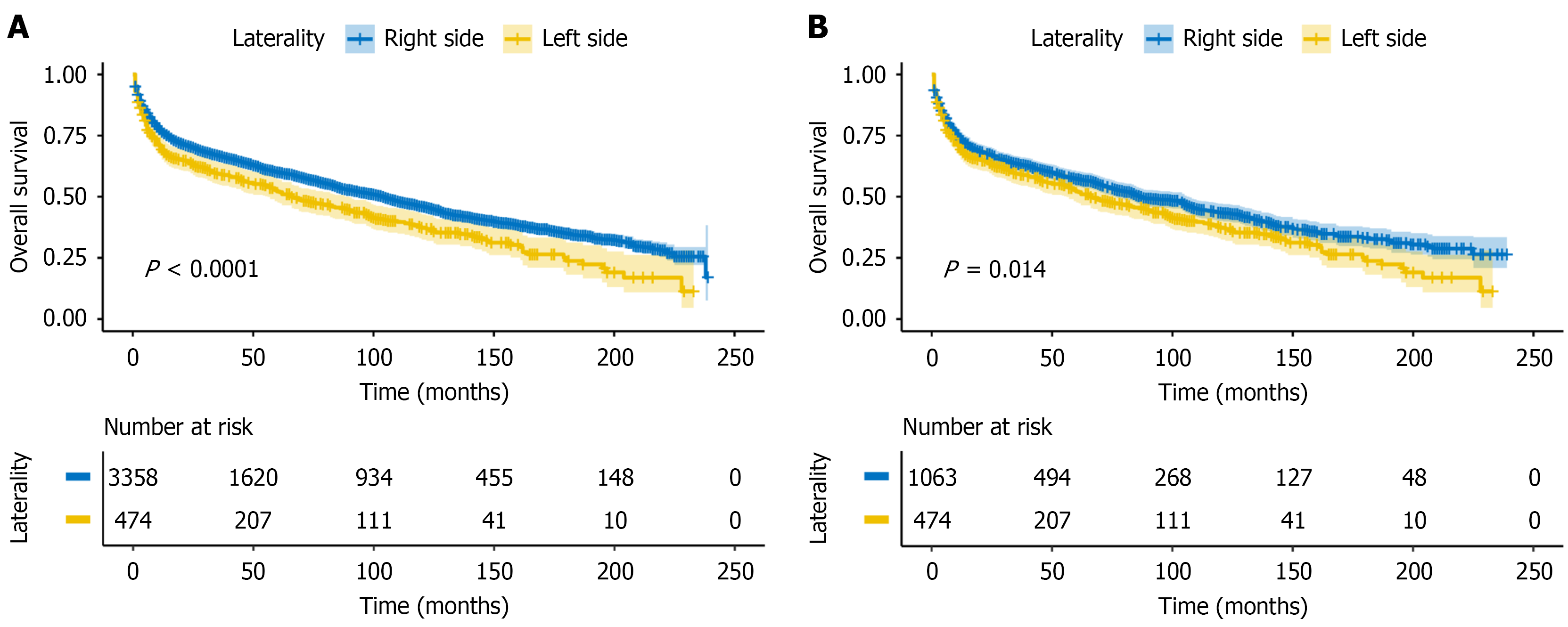

We then assessed the prognostic impact of laterality within PI-DLBCL. Right-sided tumors had significantly better OS than left-sided tumors (log-rank P < 0.001; Figure 3A). After PSM, this association persisted (log-rank P = 0.014; Figure 3B), supporting laterality as a prognostic factor in PI-DLBCL.

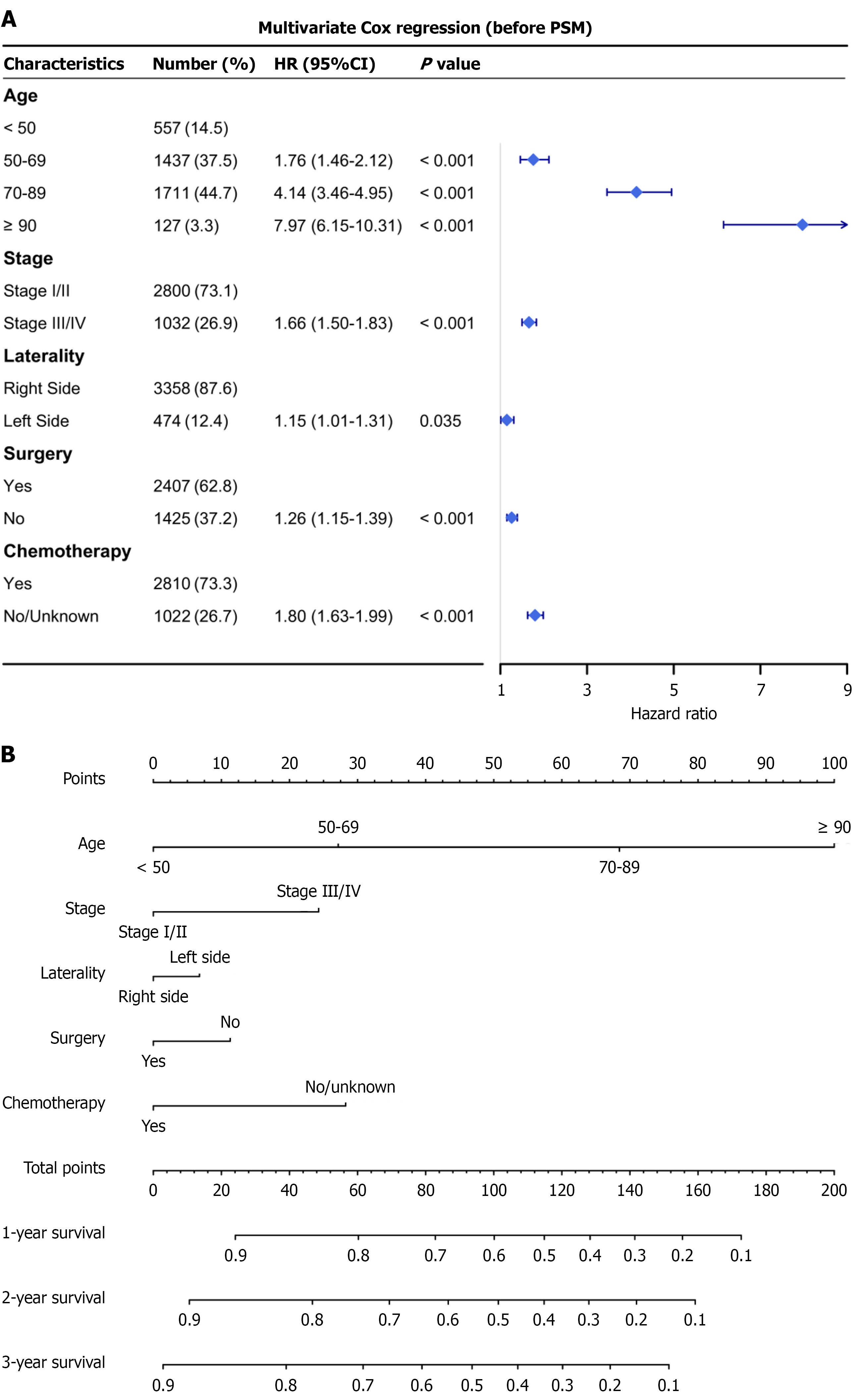

Univariable Cox regression identified age, stage, tumor laterality, surgery, and chemotherapy as significant predictors of OS in PI-DLBCL patients (all P < 0.001; Table 2). In multivariable analysis (Table 2), left-sided tumor location remained independently associated with poorer survival (HR = 1.15, 95%CI: 1.01-1.31, P = 0.035), along with older age, advanced stage, and lack of treatment. Specifically, lack of chemotherapy was associated with increased mortality (HR = 1.80, 95%CI: 1.63-1.99), and not undergoing surgery was likewise associated with worse OS (HR = 1.26, 95%CI: 1.15-1.39). In a sensitivity analysis restricted to the matched cohort, left-sided laterality remained adverse (HR = 1.16, 95%CI: 1.01-1.35, P = 0.040; Table 2).

| Analysis | Characteristics | Before propensity score matching | After propensity score matching | ||

| HR (95%CI) | P value | HR (95%CI) | P value | ||

| Univariate analysis | Age | ||||

| < 50 | Reference | Reference | |||

| 50-69 | 1.77 (1.47-2.13) | < 0.001 | 1.37 (1.03-1.80) | 0.028 | |

| 70-89 | 4.41 (3.69-5.27) | < 0.001 | 3.87 (2.98-5.02) | < 0.001 | |

| ≥ 90 | 10.20 (7.93-13.1) | < 0.001 | 8.47 (5.81-12.4) | < 0.001 | |

| Gender | |||||

| Female | Reference | Reference | |||

| Male | 0.95 (0.87-1.04) | 0.292 | 0.89 (0.77-1.02) | 0.103 | |

| Race | |||||

| White | Reference | Reference | |||

| Black | 0.96 (0.78-1.17) | 0.670 | 1.02 (0.74-1.39) | 0.922 | |

| Other | 0.88 (0.76-1.02) | 0.100 | 0.69 (0.54-0.89) | 0.004 | |

| Stage | |||||

| Stage I/II | Reference | Reference | |||

| Stage III/IV | 1.48 (1.34-1.63) | < 0.001 | 1.59 (1.38-1.84) | < 0.001 | |

| Laterality | |||||

| Right side | Reference | Reference | |||

| Left side | 1.31 (1.15-1.48) | < 0.001 | 1.22 (1.05-1.41) | 0.008 | |

| Radiation | |||||

| Yes | Reference | Reference | |||

| No/unknown | 0.88 (0.74-1.04) | 0.124 | 0.98 (0.80-1.20) | 0.857 | |

| Surgery | |||||

| Yes | Reference | Reference | |||

| No | 1.19 (1.09-1.30) | < 0.001 | 1.14 (0.99-1.31) | 0.057 | |

| Chemotherapy | |||||

| Yes | Reference | Reference | |||

| No/unknown | 1.97 (1.80-2.17) | < 0.001 | 2.14 (1.86-2.46) | < 0.001 | |

| Multivariate analysis | Age | ||||

| < 50 | Reference | Reference | |||

| 50-69 | 1.76 (1.46-2.12) | < 0.001 | 1.31 (0.99-1.72) | 0.061 | |

| 70-89 | 4.14 (3.46-4.95) | < 0.001 | 3.29 (2.53-4.38) | < 0.001 | |

| ≥ 90 | 7.97 (6.15-10.31) | < 0.001 | 6.17 (4.18-9.12) | < 0.001 | |

| Stage | |||||

| Stage I/II | Reference | Reference | |||

| Stage III/IV | 1.66 (1.50-1.83) | < 0.001 | 1.67 (1.44-1.93) | < 0.001 | |

| Laterality | |||||

| Right side | Reference | Reference | |||

| Left side | 1.15 (1.01-1.31) | 0.035 | 1.16 (1.01-1.35) | 0.040 | |

| Surgery | |||||

| Yes | Reference | Reference | |||

| No | 1.26 (1.15-1.39) | < 0.001 | 1.23 (1.06-1.42) | 0.006 | |

| Chemotherapy | |||||

| Yes | Reference | Reference | |||

| No/unknown | 1.80 (1.63-1.99) | < 0.001 | 1.86 (1.60-2.17) | < 0.001 | |

A prognostic nomogram was developed based on the five independent predictors identified in the multivariable Cox analysis: Age, stage, laterality, surgery, and chemotherapy (Figure 4). Each variable was assigned a point value, and the total score corresponded to predicted 1-, 2-, and 3-year OS. Higher total scores indicated lower survival probabilities.

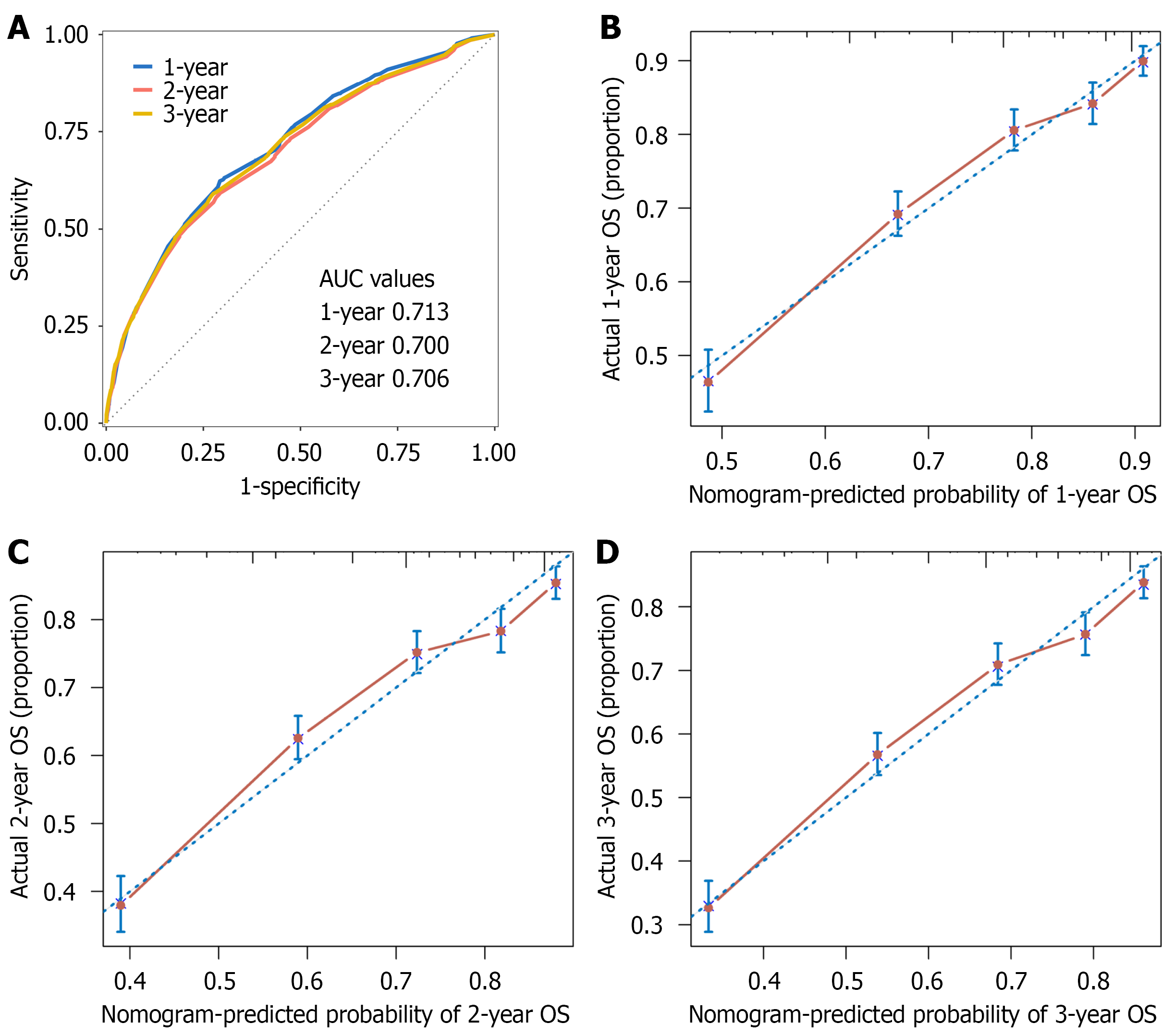

The predictive performance of the model was evaluated using time-dependent ROC curves in the SEER cohort (Figure 5), with area under the curves (AUCs) of 0.713 (95%CI: 0.693-0.733), 0.700 (95%CI: 0.678-0.716), and 0.706 (95%CI: 0.687-0.724) for 1-, 2-, and 3-year OS, respectively. Calibration plots demonstrated close agreement between predicted and observed survival at 1, 2, and 3 years (Figure 5).

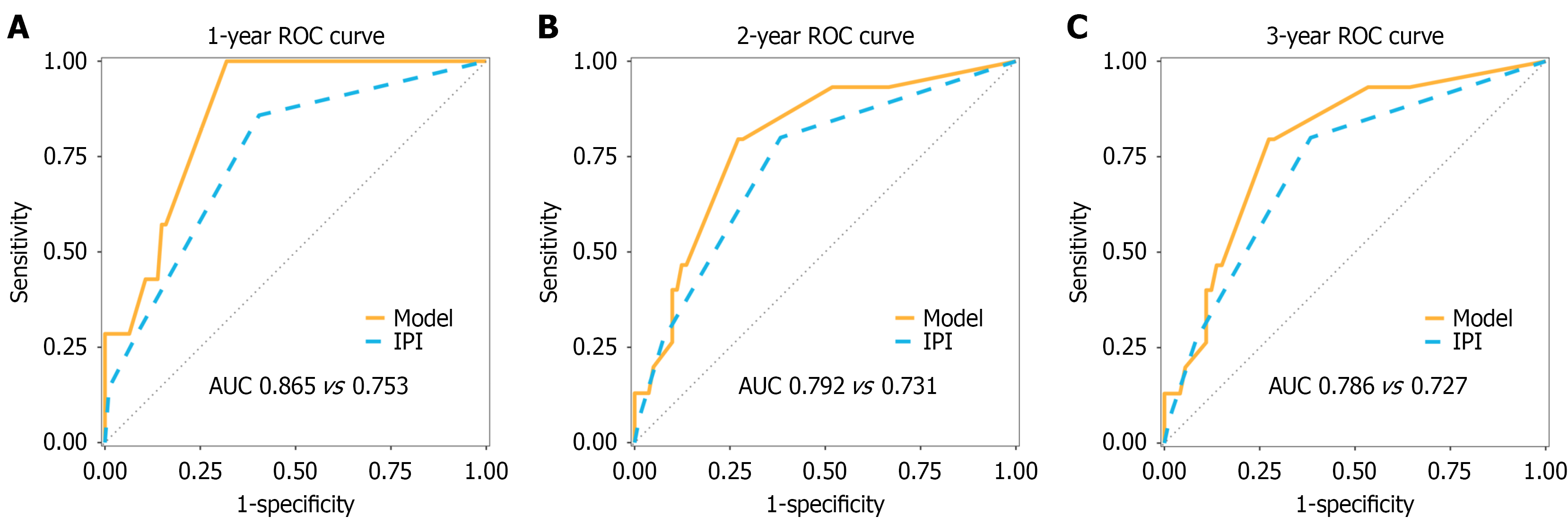

The prognostic model was externally validated in a cohort of 107 patients with PI-DLBCL from Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center. The nomogram showed higher discrimination than the IPI (C-index = 0.749, 95%CI: 0.646-0.853 vs C-index = 0.710, 95%CI: 0.604-0.817). Time-dependent ROC analysis also supported the nomogram’s superior discrimination: AUCs were 0.865 (95%CI: 0.776-0.953) vs 0.753 (95%CI: 0.591-0.915) at 1 year, 0.792 (95%CI: 0.675-0.910) vs 0.731 (95%CI: 0.604-0.857) at 2 years, and 0.786 (95%CI: 0.667-0.905) vs 0.727 (95%CI: 0.600-0.855) at 3 years (Figure 6).

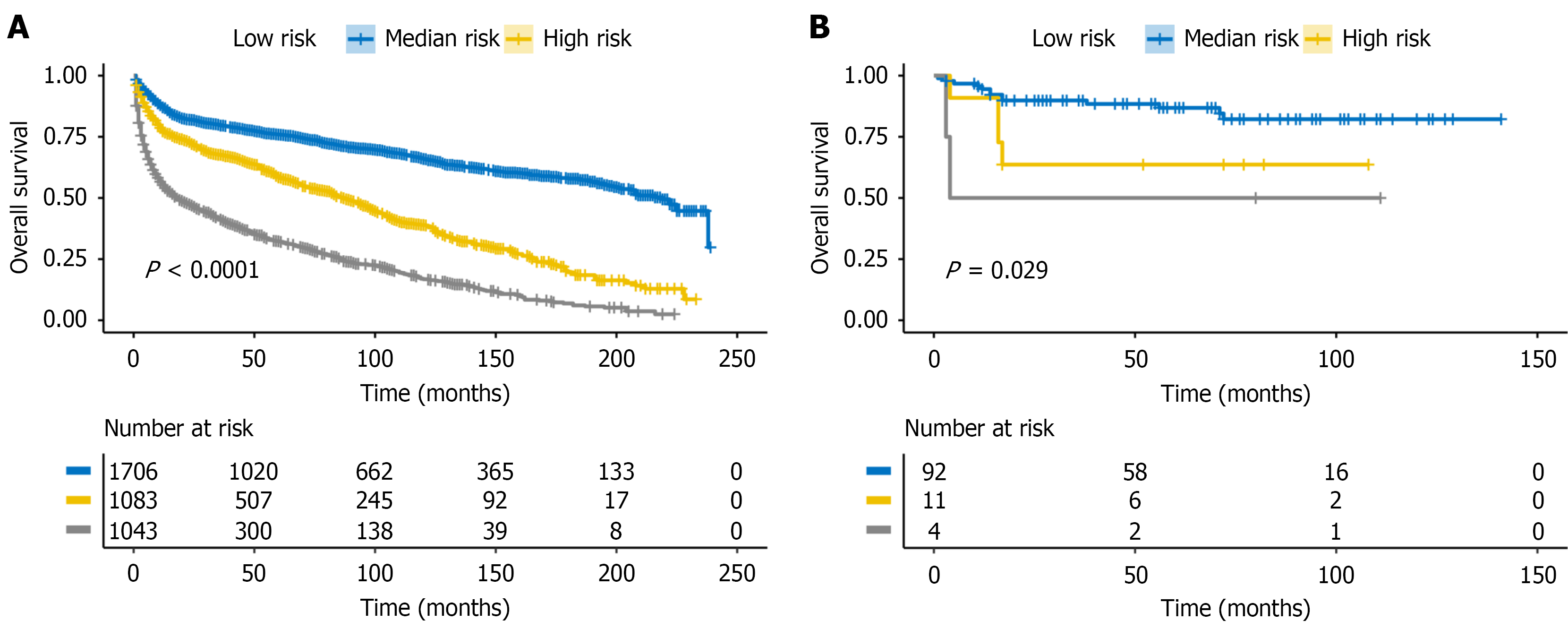

Patients were stratified into low-, median-, and high-risk groups by the total nomogram score (cut-offs 55.4 and 92.7). Kaplan-Meier curves showed clear, stepwise separation in the SEER training cohort (Figure 7A; P < 0.001), which was reproduced in the external validation cohort (Figure 7B; P = 0.029).

To our knowledge, this is the first study to assess the prognostic significance of tumor laterality in PI-DLBCL using a colon-based anatomical classification. We defined left- and right-sided lesions relative to the splenic flexure and found that left-sided PI-DLBCL was associated with significantly worse OS. Notably, previous studies have reported that primary N-DLBCL tends to have better survival than GI involvement[2]. However, this overall pattern did not apply uniformly. When PI-DLBCL was stratified by laterality, right-sided disease showed better OS than intra-abdominal N-DLBCL, whereas left-sided disease had worse OS. Laterality remained an independent prognostic factor after mul

We developed a prognostic nomogram based on five clinical variables age, stage, tumor laterality, surgery, and chemotherapy which showed good discrimination in the training cohort and outperformed the IPI in the external validation cohort (higher C-index and time-dependent AUCs). The model also demonstrated strong predictive performance at 1-3 years, supporting its utility for identifying early mortality risk. While the IPI was originally designed for N-DLBCL and most existing PI-DLBCL models focus on general clinical features[4,10-13], our model explicitly incorporates intestinal laterality as a site-specific prognostic predictor, which improved discrimination and provided clear three-tier risk stratification in both the training and external cohorts. Consistent with this, nomogram-defined risk groups derived by X-tile showed clear, stepwise separation in both the training and validation cohorts. Collectively, these findings underscore the nomogram’s clinical utility in refining prognosis and informing risk-adapted management in PI-DLBCL.

Differences in treatment patterns were observed between left- and right-sided PI-DLBCL. Patients with left-sided tumors were less likely to undergo surgery (38.4% vs 66.3%) or receive chemotherapy (69.4% vs 73.9%). Because surgery was associated with improved survival in our multivariable analysis and in prior studies[14,15], differential treatment exposure could plausibly contribute to the observed laterality gap. To further reduce confounding, we performed PSM using a 1:3 nearest-neighbor matching algorithm with replacement; the right-left difference in OS persisted in the matched cohort and likewise remained after multivariable adjustment, suggesting that differences in measured baseline characteristics alone do not fully explain the association.

Beyond treatment-related factors, biological heterogeneity across the intestinal tract may also contribute to the lateral survival difference. Prior studies have suggested that the right colon, including the ileocecal region, may harbor tumors with more favorable behavior[4,14]. Embryologically, the right colon derives from the midgut and the left colon from the hindgut, and recent microbiome studies in colorectal cancer have shown that this axis is accompanied by marked segment-specific differences in luminal bacterial communities. Specifically, left-sided tumors are enriched for potentially pro-tumorigenic, pro-inflammatory taxa such as Clostridium perfringens, Bacteroides vulgatus and Streptococcus gallolyticus, whereas right-sided tumors have relatively higher abundance of commensal species including Bifidobacterium dentium and Ruminococcus[16-18]. Single-cell RNA-sequencing has further demonstrated location-specific transcriptional programs in colorectal cancer, with distinct gene-expression signatures across tumor cells and multiple immune subsets [cluster of differentiation (CD) 4+ and CD8+ T cells, regulatory T cells and M1/M2-like macrophages] between left- and right-sided lesions, supporting the existence of anatomically defined immune microenvironments along the colon[19].

In DLBCL, 16S rRNA profiling of untreated patients has revealed pronounced gut dysbiosis compared with healthy controls, characterized by enrichment of Proteobacteria/Enterobacteriaceae and depletion of Bacteroidetes. Specific microbial signatures correlate with stage, IPI risk group and systemic immune indices such as lymphocyte counts and immunoglobulin levels, indicating that the gut microbiota is tightly linked to disease characteristics and host immune status[20]. Complementary data from a larger DLBCL cohort show that higher Enterobacteriaceae abundance is associated with inferior responses to R-CHOP, shorter progression-free survival and distinct cytokine profiles (elevated interleukin-6 and interferon-γ), suggesting that microbiome-driven immune modulation can influence lymphoma treatment outcomes[21]. Although we did not directly assess microbiota composition or mucosal immune markers (e.g., T helper cell 17/re

Our nomogram provides an individualized risk assessment tool for PI-DLBCL by incorporating intestinal-specific variables, including tumor laterality. Unlike traditional models such as the IPI, which overlook site-specific differences, the present model was externally validated in an independent Chinese cohort and maintained robust performance, supporting generalizability across populations and care settings. By operationalizing laterality (left vs right of the splenic flexure) within a clinically accessible tool, our work parallels the established relevance of laterality in colorectal cancer and extends it to PI-DLBCL in a prognostic context.

This study has limitations chiefly related to the use of the SEER registry: As a retrospective analysis it may be subject to selection bias and residual confounding despite multivariable adjustment and PSM; Key clinical and treatment details (e.g., B symptoms, bulky disease, lactate dehydrogenase levels, treatment regimen) are not captured in SEER and therefore could not be incorporated into model development, so the potential impact of these unmeasured prognostic factors cannot be formally quantified and residual confounding may persist even after adjustment for age, stage, surgery and chemotherapy; Molecular/genomic data, standardized cell-of-origin or double-expressor status, and fine-grained subsite coding within the left or right intestine are lacking; And the number of left-sided cases is relatively small compared with right-sided disease (474 vs 3358), which may reduce the precision of estimates for left-sided PI-DLBCL and should be considered when interpreting laterality-related findings. Prospective, multicenter studies with systematic collection of diagnostic intestinal biopsies and paired clinical data are warranted to validate our findings and to compare germinal center B-cell-like (GCB) vs non-GCB cell-of-origin subtypes, MYD88/CD79B mutations, MYC/BCL2 double expression, and immune microenvironment features (e.g., CD8+ and programmed cell death 1+ T-cell infiltration and macrophage polarization) between right- and left-sided PI-DLBCL. Integration of multi-omic tumor profiling (genomic, transcriptomic, and immune) and spatial analyses, gut microbiome data, and detailed treatment response information may help elucidate the mechanisms underlying site-specific prognostic differences. Future models could then incorporate validated molecular and immune biomarkers alongside anatomical laterality, evaluate clinical utility, and assess whether laterality-informed stratification can guide therapy selection or trial design.

In this study, we developed and externally validated a prognostic nomogram for PI-DLBCL that incorporates intestinal laterality as a novel independent predictor. The model demonstrated superior predictive performance compared with the IPI in the external validation cohort and supported clear three-tier risk stratification in both the training and external cohorts. These findings highlight the clinical relevance of tumor laterality and support laterality-informed prognostic assessment in PI-DLBCL.

We thank all the pathologists, oncologists, radiologists, surgeons, and nurses who contributed to this study. We thank all the patients and their families who participated in this study. We thank the High-Level Talent Support Program of Hunan Cancer Hospital.

| 1. | Wang SS. Epidemiology and etiology of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Semin Hematol. 2023;60:255-266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 27.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Castillo JJ, Winer ES, Olszewski AJ. Sites of extranodal involvement are prognostic in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in the rituximab era: an analysis of the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results database. Am J Hematol. 2014;89:310-314. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Li SS, Zhai XH, Liu HL, Liu TZ, Cao TY, Chen DM, Xiao LX, Gan XQ, Cheng K, Hong WJ, Huang Y, Lian YF, Xiao J. Whole-exome sequencing analysis identifies distinct mutational profile and novel prognostic biomarkers in primary gastrointestinal diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Exp Hematol Oncol. 2022;11:71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Wang Y, Song J, Wen S, Zhang X. A visual model for prognostic estimation in patients with primary diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of small intestine and colon: analysis of 1,613 cases from the SEER database. Transl Cancer Res. 2021;10:1842-1855. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Wang J, Zhou M, Zhou R, Xu J, Chen B. Nomogram for Predicting the Overall Survival of Adult Patients With Primary Gastrointestinal Diffuse Large B Cell Lymphoma: A SEER- Based Study. Front Oncol. 2020;10:1093. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Liu X, Cao D, Liu H, Ke D, Ke X, Xu X. Clinical Features Analysis and Survival Nomogram of Primary Small Intestinal Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma. Cancer Manag Res. 2022;14:2639-2648. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Wang J, Ren W, Zhang C, Wang X. A New Staging System Based on the Dynamic Prognostic Nomogram for Elderly Patients With Primary Gastrointestinal Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022;9:860993. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Petrelli F, Tomasello G, Borgonovo K, Ghidini M, Turati L, Dallera P, Passalacqua R, Sgroi G, Barni S. Prognostic Survival Associated With Left-Sided vs Right-Sided Colon Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:211-219. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 353] [Cited by in RCA: 565] [Article Influence: 62.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Lee MS, Menter DG, Kopetz S. Right Versus Left Colon Cancer Biology: Integrating the Consensus Molecular Subtypes. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2017;15:411-419. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 175] [Cited by in RCA: 280] [Article Influence: 31.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Gao F, Wang ZF, Tian L, Dong F, Wang J, Jing HM, Ke XY. A Prognostic Model of Gastrointestinal Diffuse Large B Cell Lymphoma. Med Sci Monit. 2021;27:e929898. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Cha RR, Baek DH, Lee GW, Park SJ, Lee JH, Park JH, Kim TO, Lee SH, Kim HW, Kim HJ; Busan Ulsan Gyeongnam Intestinal Study Group Society (BIGS). Clinical Features and Prognosis of Patients with Primary Intestinal B-cell Lymphoma Treated with Chemotherapy with or without Surgery. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2021;78:320-327. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Chen X, Wang J, Liu Y, Lin S, Shen J, Yin Y, Wang Y. Primary intestinal diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: novel insights and clinical perception. Front Oncol. 2024;14:1404298. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Ishikawa E, Nakamura M, Shimada K, Tanaka T, Satou A, Kohno K, Sakakibara A, Furukawa K, Yamamura T, Miyahara R, Nakamura S, Kato S, Fujishiro M. Prognostic impact of PD-L1 expression in primary gastric and intestinal diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. J Gastroenterol. 2020;55:39-50. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Fan X, Zang L, Zhao BB, Yi HM, Lu HY, Xu PP, Cheng S, Li QY, Fang Y, Wang L, Zhao WL. Development and validation of prognostic scoring in primary intestinal diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: a single-institution study of 184 patients. Ann Transl Med. 2021;9:1542. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Wang M, Ma S, Shi W, Zhang Y, Luo S, Hu Y. Surgery shows survival benefit in patients with primary intestinal diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: A population-based study. Cancer Med. 2021;10:3474-3485. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Missiaglia E, Jacobs B, D'Ario G, Di Narzo AF, Soneson C, Budinska E, Popovici V, Vecchione L, Gerster S, Yan P, Roth AD, Klingbiel D, Bosman FT, Delorenzi M, Tejpar S. Distal and proximal colon cancers differ in terms of molecular, pathological, and clinical features. Ann Oncol. 2014;25:1995-2001. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 374] [Cited by in RCA: 520] [Article Influence: 43.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kwak HD, Ju JK. Immunological Differences Between Right-Sided and Left-Sided Colorectal Cancers: A Comparison of Embryologic Midgut and Hindgut. Ann Coloproctol. 2019;35:342-346. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 18. | Zhong M, Xiong Y, Ye Z, Zhao J, Zhong L, Liu Y, Zhu Y, Tian L, Qiu X, Hong X. Microbial Community Profiling Distinguishes Left-Sided and Right-Sided Colon Cancer. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2020;10:498502. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Guo W, Zhang C, Wang X, Dou D, Chen D, Li J. Resolving the difference between left-sided and right-sided colorectal cancer by single-cell sequencing. JCI Insight. 2022;7:e152616. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 14.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Lin Z, Mao D, Jin C, Wang J, Lai Y, Zhang Y, Zhou M, Ge Q, Zhang P, Sun Y, Xu K, Wang Y, Zhu H, Lai B, Wu H, Mu Q, Ouyang G, Sheng L. The gut microbiota correlate with the disease characteristics and immune status of patients with untreated diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1105293. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 21. | Yoon SE, Kang W, Choi S, Park Y, Chalita M, Kim H, Lee JH, Hyun DW, Ryu KJ, Sung H, Lee JY, Bae JW, Kim WS, Kim SJ. The influence of microbial dysbiosis on immunochemotherapy-related efficacy and safety in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2023;141:2224-2238. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/