Published online Jan 7, 2026. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v32.i1.113232

Revised: September 3, 2025

Accepted: September 30, 2025

Published online: January 7, 2026

Processing time: 139 Days and 0.7 Hours

Post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis (PEP) is a prevalent and potentially serious complication in patients undergoing endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography.

To comprehensively assess the efficacy of indomethacin therapy in reducing PEP risk.

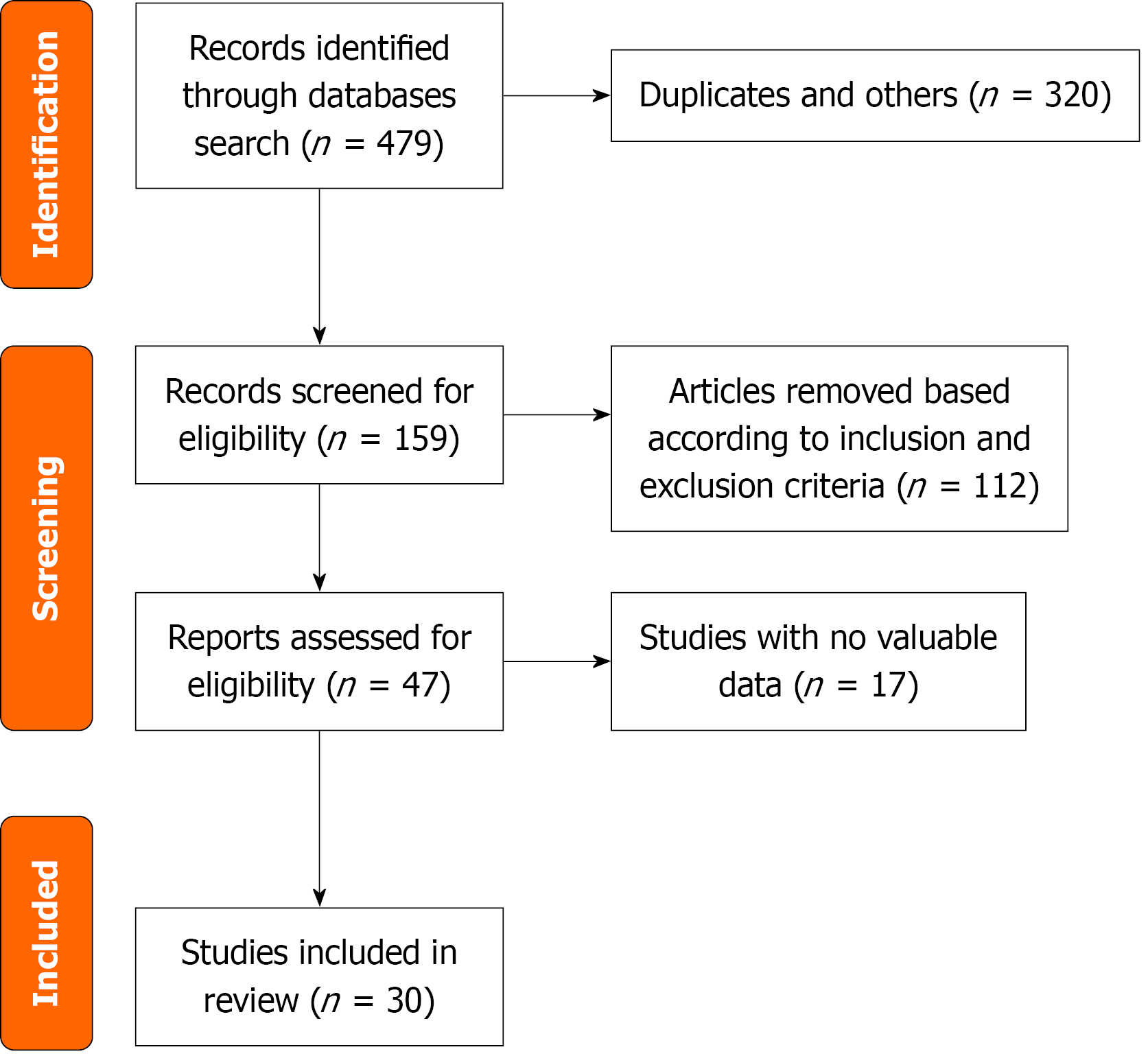

We searched PubMed, EMBASE, Scopus, and Cochrane Library databases to identify randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that compared rectal indomethacin with a control group to prevent PEP. Duplicates were removed, and studies were included based on the established inclusion criteria. We used the Cochrane Colla

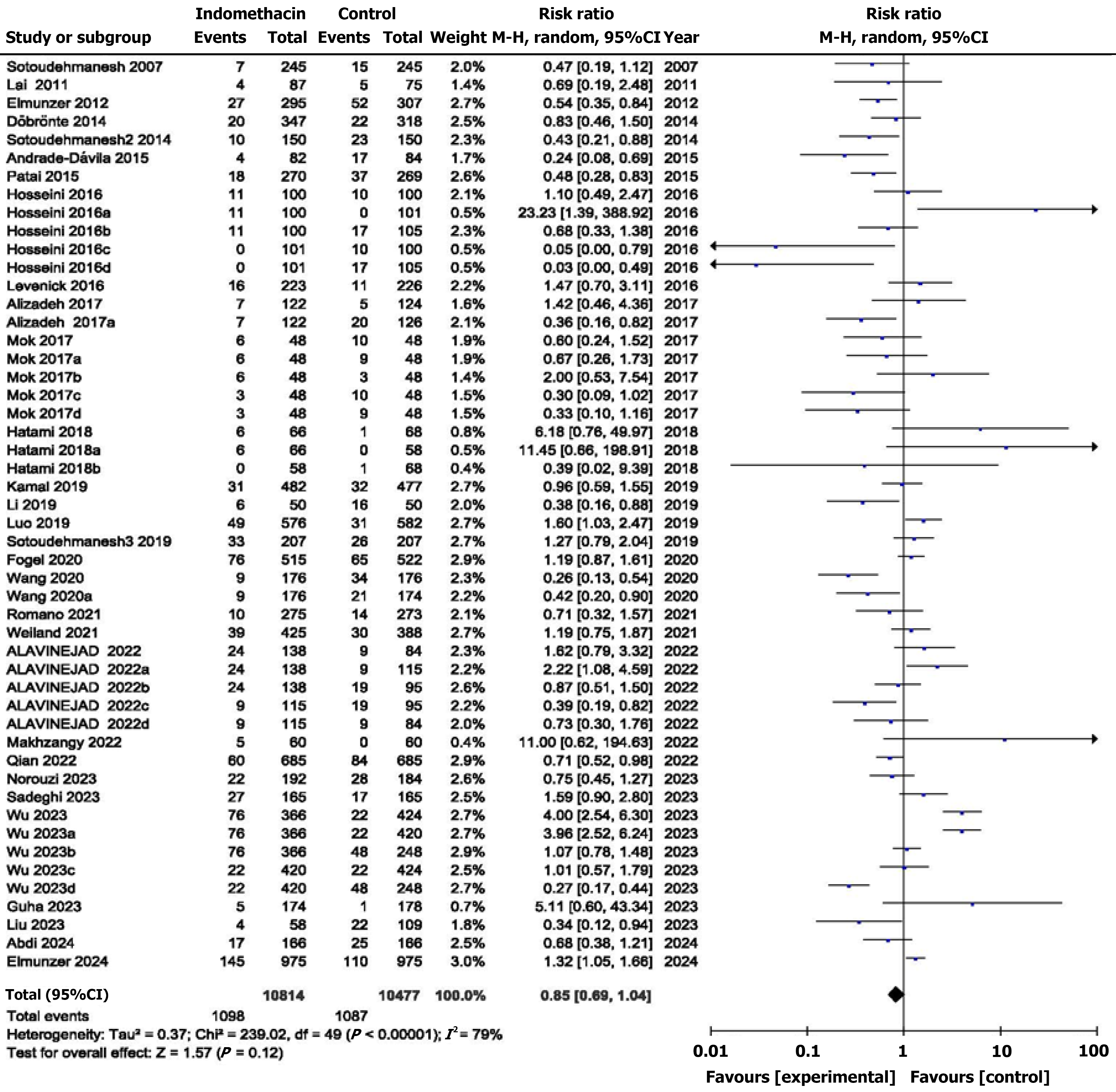

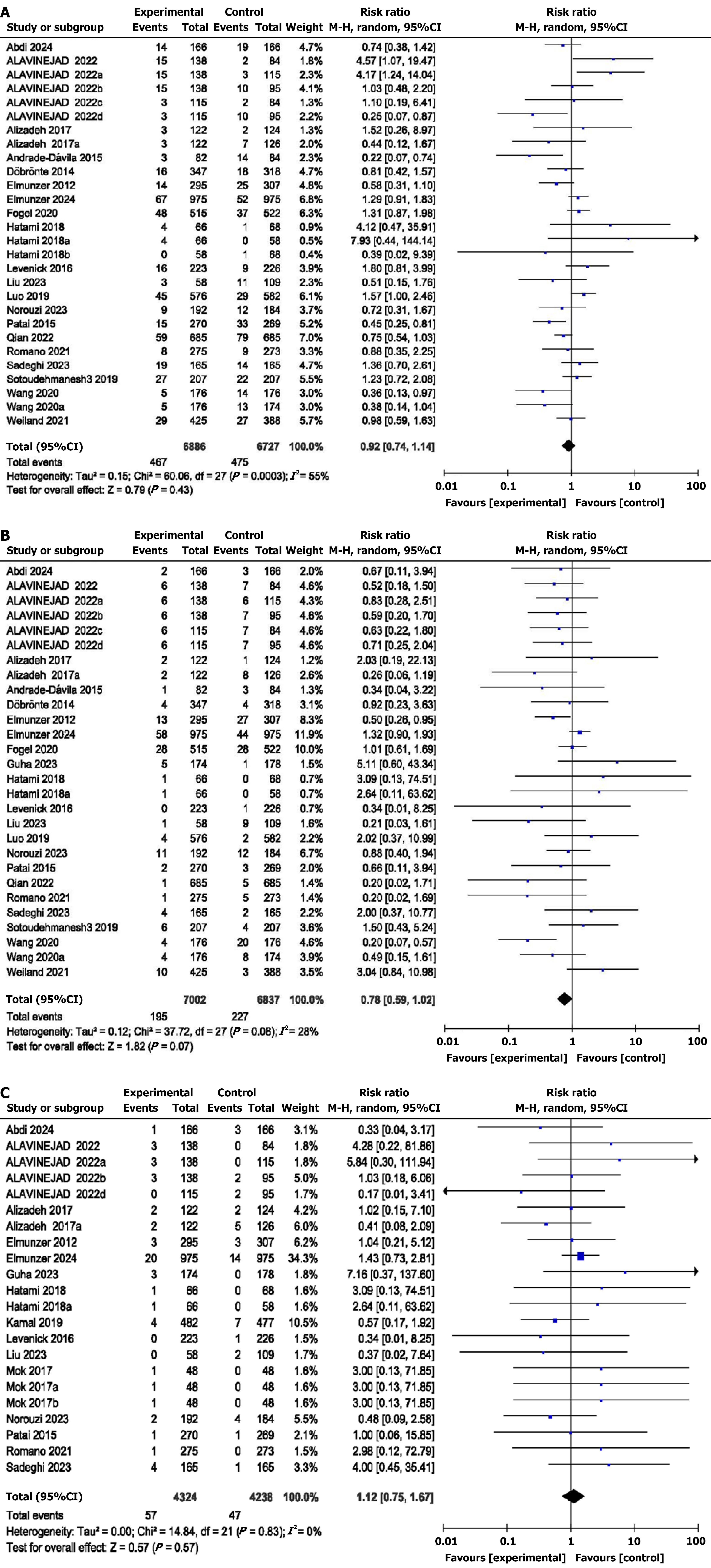

We included a total of 30 RCTs involving 16977 patients. Compared to the control group, rectal indomethacin showed comparable rates of overall PEP (PEP; RR = 0.85, 95%CI: 0.69-1.04, I2 = 79%) with no statistically significant difference of RR in mild (RR = 0.92, 95%CI: 0.74-1.14), moderate (RR = 0.78, 95%CI: 0.59-1.02), or severe PEP (RR = 1.12, 95%CI: 0.75-1.67). There was also no difference in cases of adverse events (RR = 0.97, 95%CI: 0.69-1.35), abdominal pain (RR = 1.14, 95%CI: 0.80-1.62), bleeding (RR = 1.07, 95%CI: 0.70-1.63), or mortality (RR = 0.86, 95%CI: 0.56-1.33) between the two groups. Subgroup analyses were also performed.

Rectal indomethacin appears to be safe and may offer benefit in selected high-risk patients, though findings should be interpreted with caution due to high heterogeneity.

Core Tip: This meta-analysis assessed the efficacy of rectal indomethacin in the prevention of post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis by reviewing the results of 30 randomized controlled trials. Indomethacin didn’t show a significant reduction in overall post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis rates or adverse events relative to controls, however, it may be beneficial in particular high-risk patients, but with caution given to significant heterogeneity in the results.

- Citation: Tian F, Huang ZC, Khizar H, Qiu K. Efficacy of indomethacin for the prevention of post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis: A comprehensive meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. World J Gastroenterol 2026; 32(1): 113232

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v32/i1/113232.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v32.i1.113232

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is a frequently used medical procedure for diagnosing and treating pancreaticobiliary diseases[1,2]. However, post-ERCP pancreatitis (PEP) remains a prevalent and potentially serious adverse event, occurring in 3%-10% of patients without any particular criteria and resulting in significant mor

For several decades, the insertion of a temporary, prophylactic stent in the pancreatic duct during ERCP was the sole effective preventative measure for patients at high risk for PEP[8-10]. Given the significant consequences of PEP, there has been a tremendous amount of interest in studying pharmacologic and procedural interventions to lower its prevalence[11-15]. Rectal indomethacin is a highly promising agent because of its affordability, ease of administration, and favorable safety profile[16,17]. Research indicates that certain agents involved in inflammation, such as phospholi

Over the past decade, several randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have evaluated the efficacy of prophylactic indomethacin in preventing PEP, but the results have been mixed and inconclusive[20-23]. Previous meta-analyses have also reached conflicting conclusions, likely due to differences in trial inclusion criteria, quality assessment, and analytical methods[8,22,24-26]. To better understand the actual efficacy of indomethacin in PEP prophylaxis, a comprehensive review of RCTs is required, given the conflicting data and potential impact on clinical practice.

This study aims to offer a more accurate estimate of the treatment impact and investigate potential sources of variation by combining data from multiple high-quality trials. Therefore, we conducted an updated and comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis to critically evaluate the evidence and provide the most reliable estimates of the pros and cons of indomethacin for preventing PEP.

This meta-analysis was conducted by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses statement[27].

We registered this study at Prospero with the number CRD42024563974. (https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/view/CRD42024563974).

Author (Tian F) searched the PubMed/MEDLINE, EMBASE, Scopus, and Cochrane Library databases from inception to June 30, 2024 to identify relevant studies. The search strategy used keywords and medical subject headings terms related to ERCP, indomethacin, and pancreatitis, with no restrictions on language. We also manually searched the reference lists of the included studies and previous meta-analyses for additional eligible trials (search strategy in Supplementary material).

Two reviewers (Tian F and Huang ZC) independently screened titles and abstracts and then full-text articles for eligi

Inclusion criteria: (1) Had a RCT design; (2) Compared rectal indomethacin with a control for PEP prophylaxis; and (3) Reported the incidence of PEP.

Exclusion criteria: (1) Observational studies, case reports, and trials that used other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs); (2) Studies that used non-rectal routes of indomethacin administration; and (3) Duplicate publications or studies in which the required outcomes were missing.

Two reviewers (Tian F and Huang ZC) independently extracted data, including study characteristics (author, year, country, study settings, sample size, and ERCP indications), patient demographics, indomethacin dose, and outcome data, via a standardized form. Discrepancies were resolved by a rereview of the primary articles. We employed the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomized trials to evaluate the risk of bias[28]. This tool explores various domains, including random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and staff members, blinding of outcome evaluation, inadequate outcome data, selective reporting, and other sources of bias. We evaluated each domain and assigned a rating of low, some concern, or high risk of bias for the studies.

The primary outcome evaluated was the incidence of PEP, which is typically defined by the onset or worsening of abdominal discomfort that is consistent with pancreatitis, followed by an elevation in serum amylase or lipase ≥ 3 times the upper limit of normal at 24 hours post-procedure. The secondary outcomes included the severity of pancreatitis (based on criteria), length of hospital stay, and adverse events. We conducted subgroup analyses via the following comparisons: Indomethacin alone vs indomethacin combined, indomethacin combined vs control, indomethacin vs placebo, indomethacin combined vs placebo, indomethacin vs saline/saline combined, indomethacin vs glycerin/epinephrine or combined, indomethacin vs indomethacin + stent, two-arm vs multiple-arm studies, selected patients vs unselected patients, single-center vs multicenter studies, and patients aged < 60 vs > 60 years.

We pooled dichotomous outcomes using risk ratios (RRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The continuous outcomes were pooled by calculating the mean differences (MDs) along with their 95%CIs. A random effects model with the Mantel-Haenszel method was applied to evaluate the variation among studies. We pooled the multivariance analysis outcomes of the studies via the generic inverse variance and random effect methods to compute the pooled RRs and 95%CIs. We evaluated heterogeneity via the Cochran Q test and calculated the I2 statistic. The heterogeneity was classified as low, moderate, or high on the basis of I2 values of 30%-49%, 50%-74%, and more than 75%, respectively[29]. Whereas less than 30 was regarded as negligible.

Assessing publication bias involved visually inspecting funnel plots and conducting Egger’s regression test[30]. We evaluated to determine the impact of individual studies on the pooled estimate. This was done via sensitivity analysis via the leave-one-out method. We conducted subgroup analyses to examine various patient and procedural factors. P ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant. We conducted our analyses via Review Manager 5.4 (Cochrane Collaboration).

The literature search yielded 479 records, of which the meta-analysis included 30 RCTs with a total of 16977 patients[20,31-38] (Figure 1).

The characteristics of the studies are presented in Tables 1 and 2. The mean age varied between 42 and 66 years, with female participants constituting 29% to 100% of the total. The primary indications for ERCP were choledocholithiasis and other standard reasons for the procedure. Most trials used a single 100 mg rectal dose; exceptions included 200 mg escalation (Fogel et al[36], 2020) and split dosing (Lai et al[37], 2019), either alone or in combination, before or immediately after the procedure. These studies were conducted worldwide, with seven of them conducted in China, six in the United States, seven in Iran, two in Mexico, two in India, two in Hungary and other different countries. Seven studies were conducted as multiple-arm RCTs[32,39-44]. We analyzed the data from all these studies for the indomethacin group, which were classified as arms (a, b, c, d). Consequently, we analyzed a total of 50 double-arm comparisons to determine the primary outcome. Ten studies used indomethacin in conjunction with other medications, whereas twenty studies used it as a single therapy in comparison with a control group. Seventeen studies included all eligible patients receiving ERCP for many different indications, whereas thirteen trials included selected patients with moderate to high risk of PEP.

| Ref. | Setting | Intervention | Control | Indication | Patients | Age | Female | PEP | |||

| Overall | Mild | Moderate | Severe | ||||||||

| Romano-Munive et al[50], 2021, Mexico | Multicenter, double blinded, unselected patients | 100 mg of rectal indomethacin with 10 mL water | 100 mg of rectal indomethacin with 1:10000 epinephrine dilution (0.1 mg/mL) | Naïve papilla and indication for ERCP | EI = 275 | 50.3 ± 21.4 | 188 | 10 | 8 | 1 | 1 |

| WI = 273 | 51.8 ± 20.3 | 192 | 14 | 9 | 5 | 0 | |||||

| Patai et al[22], 2017, Hungary | Single-center, double blinded, unselected patients | 100 mg of rectal indomethacin | Placebo | Intact papilla undergoing biliary endoscopic therapy | Indomethacin = 270 | 66.25 | 181 | 18 | 15 | 2 | 1 |

| Placebo = 269 | 64.51 | 181 | 37 | 33 | 3 | 1 | |||||

| Elmunzer et al[35], 2012, United States | Multicenter, single blinded, selected patients | 100 mg of rectal indomethacin suppositories | Placebo | Risk of post-ERCP pancreatitis | Indomethacin = 295 | 44.4 ± 13.5 | 229 | 27 | 14 | 13 | 3 |

| Placebo = 307 | 46.0 ± 13.1 | 247 | 52 | 25 | 27 | 3 | |||||

| Levenick et al[51], 2016, United States | Single-center, single blinded, unselected patients | 100 mg of rectal indomethacin suppositories | Placebo | Patients undergoing ERCP | Indomethacin = 223 | 64.9 | 118 | 16 | 16 | 0 | 0 |

| Placebo = 226 | 64.3 | 118 | 11 | 9 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Liu et al[52], 2024, China | Single-center, single blinded, unselected patients | 100 mg of rectal indomethacin suppositories | Placebo | Patients undergoing ERCP for bile duct stones | Indomethacin = 58 | 61.6 ± 15.6 | 29 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 0 |

| Placebo = 109 | 62.9 ± 15.2 | 49 | 22 | 11 | 9 | 2 | |||||

| Li et al[53], 2019, China | Single-center, single blinded, unselected patients | 100 mg indomethacin suppositories | Glycerin suppository | Patients undergoing ERCP for bile duct stones | Indomethacin = 50 | 55.68 ± 13.58 | 31 | 6 | NA | NA | NA |

| Glycerin = 50 | 58.70 ± 13.60 | 37 | 16 | ||||||||

| Mohammad Alizadeh et al[44], 2017, Iran | Single-center, single blinded, unselected patients | 100 mg indomethacin | 100 mg diclofenac and 500 mg naproxen | Patients undergoing ERCP | Indomethacin = 122 | 58.0 ± 16.8 | 65 | 7 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| Diclofenac = 124 | 56.5 ± 18.7 | 66 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 2 | |||||

| Naproxen = 126 | 54.8 ± 13.7 | 66 | 20 | 7 | 8 | 5 | |||||

| Alavinejad et al[32], 2022, multiple countries | Multicenter, single blinded, unselected patients | 100 mg indomethacin | 1200 mg oral N-acetyl cysteine, N-acetyl cysteine plus indomethacin, placebo | Standard indications for ERCP | Indomethacin = 138 | 55.36 | 85 | 24 | 15 | 6 | 3 |

| N-acetyl cysteine = 84 | 57.44 | 49 | 9 | 2 | 7 | 0 | |||||

| N-acetyl cysteine + indomethacin = 115 | 56.11 | 62 | 9 | 3 | 6 | 0 | |||||

| Placebo = 95 | 61.53 | 55 | 19 | 10 | 7 | 2 | |||||

| Guha et al[38], 2023, India | Single-center, single blinded, unselected patients | 100 mg indomethacin | Vigorous hydration | Standard indications for ERCP | Indomethacin = 174 | 43.7 ± 14.4 | 119 | 5 | NA | 5 | 3 |

| Aggressive hydration = 178 | 44.3 ± 14.7 | 127 | 1 | 1 | 0 | ||||||

| Sotoudehmanesh et al[23], 2007, Iran | Single-center, double blinded, unselected patients | 100 mg indomethacin | Placebo | Standard indications for ERCP | Indomethacin = 245 | 58.4 ± 17.1 | 134 | 7 | NA | NA | NA |

| Placebo = 245 | 58.1 ± 16.8 | 130 | 15 | ||||||||

| Andrade-Dávila et al[33], 2015, Mexico | Single-center, single blinded, selected patients | 100 mg indomethacin | Glycerin suppository | Risk of post-ERCP pancreatitis | Indomethacin = 82 | 51.59 ± 18.55 | 51 | 4 | 3 | 1 | |

| Glycerin = 84 | 54.0 ± 17.85 | 59 | 17 | 14 | 3 | ||||||

| Qian et al[54], 2022, China | Single-center, double blinded, unselected patients | 100 mg indomethacin | Glycerin suppository | Risk of post-ESWL pancreatitis | Indomethacin = 685 | 46 (35-54) | 194 | 60 | 59 | 1 | 0 |

| Glycerin = 685 | 47 (37-54) | 197 | 84 | 79 | 5 | 0 | |||||

| Wu et al[43], 2023, China | Single-center, single blinded, selected patients | 100 mg indomethacin | 0.25 mg of somatostatin indomethacin + somatostatin placebo | Risk of post-ERCP pancreatitis | Indomethacin = 366 | 52.7 ± 14.2 | 196 | 76 | NA | NA | NA |

| Somatostatin = 424 | 49.3 ± 16.6 | 163 | 22 | ||||||||

| Somatostatin + Indomethacin = 420 | 51.9 ± 16.2 | 196 | 22 | ||||||||

| Placebo = 248 | 50.4 ± 15.9 | 116 | 48 | ||||||||

| Döbrönte et al[34], 2014, Hungary | Multicenter, single blinded, unselected patients | 100 mg indomethacin | Placebo | Risk of post-ERCP pancreatitis | Indomethacin = 347 | NA | 214 | 20 | 16 | 4 | NA |

| Placebo = 318 | 212 | 22 | 18 | 4 | |||||||

| Fogel et al[36], 2020, United States | Multicenter, double blinded, selected patients | 100 mg indomethacin | 200 mg indomethacin | High risk of post-ERCP pancreatitis | Indomethacin = 515 | 49.3 (15.2) | 392 | 76 | 48 | 28 | NA |

| Placebo = 522 | 50.4 (15) | 421 | 65 | 37 | 28 | ||||||

| Norouzi et al[55], 2023, Iran | Single-center, double blinded, selected patients | 100 mg indomethacin + somatostatin | 100 mg indomethacin + saline | High risk of post-ERCP pancreatitis | Indomethacin = 192 | 63.03 (16.57) | 116 | 22 | 9 | 11 | |

| Control group = 184 | 62.95 (15.58) | 98 | 28 | 12 | 12 | ||||||

| Sadeghi et al[56], 2023, Iran | Single-center, unselected patients | 100 mg indomethacin | 100mg indomethacin + vitamin C | Standard indications for ERCP | Indomethacin = 165 | 59.0 ± 14.4 | 96 | 27 | 19 | 4 | 4 |

| Control group = 165 | 62.0 ± 14.1 | 93 | 17 | 14 | 2 | 1 | |||||

| Kamal et al[57], 2019, United States, India | Multicenter, double blinded, selected patients | 100 mg indomethacin | 100 mg indomethacin + 20 mL of 0.02% epinephrine | High risk of post-ERCP pancreatitis | Indomethacin = 482 | 52.16 (14.3) | 275 | 31 | NA | NA | 4 |

| Control group = 477 | 52.56 (15.6) | 276 | 32 | 7 | |||||||

| Elmunzer et al[20], 2024, Canada | Multicenter, double blinded, selected patients | 100 mg indomethacin | 100 mg indomethacin + stent | High risk of post-ERCP pancreatitis | Indomethacin = 975 | 55.6 (16.4) | 599 | 145 | 67 | 58 | 20 |

| Control group = 975 | 55.8 (16.3) | 596 | 110 | 52 | 44 | 14 | |||||

| Makhzangy et al[21], 2022, Egypt | Single-center, unselected patients | 100 mg indomethacin | 100 mg indomethacin + saline | Standard indications for ERCP | Indomethacin = 60 | 45.27 ± 15.39 | 29 | 5 | NA | NA | NA |

| Control group = 60 | 42.3 ± 14.28 | 37 | 0 | ||||||||

| Luo et al[58], 2019, China | Multicenter, double blinded, unselected patients | 100 mg indomethacin + epinephrine | 100 mg indomethacin + saline | Standard indications for ERCP | Indomethacin = 576 | 62 (50-71) | 281 | 49 | 45 | 4 | NA |

| Control group = 582 | 61 (49-71) | 280 | 31 | 29 | 2 | ||||||

| Hosseini et al[40], 2016, Iran | Single-center, double blinded, selected patients | 100 mg indomethacin | 3 L normal saline. Indomethacin + normal saline 2 g glycerin suppositories | Standard indications for ERCP for CBD | Indomethacin = 100 | 51.20 ± 12.12 | 40 | 11 | NA | NA | NA |

| Intravenous saline = 100 | 50.76 ± 13.32 | 53 | 10 | ||||||||

| Normal saline + indomethacin = 101 | 47.91 ± 11.06 | 62 | 0 | ||||||||

| Glycerin = 105 | 49 ± 14.26 | 49 | 17 | ||||||||

| Abdi et al[31], 2024, Iran | Single-center, double blinded, unselected patients | 100 mg indomethacin plus CoQ10 | Indomethacin plus placebo | Standard indications for ERCP | Indomethacin = 166 | 55.0 ± 13.1 | 92 | 17 | 14 | 2 | 1 |

| Placebo = 166 | 58.0 ± 13.4 | 87 | 25 | 19 | 3 | 3 | |||||

| Mok et al[41], 2017, United States | Single-center, double blinded, selected patients | 100 mg Indomethacin plus normal saline | Normal saline + placebo LR + placebo LR + India | High risk of post-ERCP pancreatitis | Indomethacin + normal saline = 48 | 62 | 33 | 6 | NA | NA | 1 |

| Normal saline + placebo = 48 | 58 | 29 | 10 | 0 | |||||||

| LR + placebo = 48 | 58 | 35 | 9 | 0 | |||||||

| LR + indomethacin = 48 | 63 | 23 | 3 | 0 | |||||||

| Sotoudehmanesh et al[59], 2014, Iran | Single-center, double blinded, selected patients | 100 mg indomethacin + dinitrate tablet | 100 mg indomethacin + placebo | Standard indications for ERCP | Indomethacin = 150 | 58.4 ± 17.8 | 74 | 10 | NA | NA | NA |

| Placebo = 150 | 58.6 ± 17.5 | 80 | 23 | ||||||||

| Wang et al[42], 2020, China | Single-center, double blinded, selected patients | Indomethacin + nitroglycerin | Placebo suppository PSP with placebo suppository + tablet | Standard indications for ERCP only female | Indomethacin = 176 | 66.87 ± 13.04 | 176 | 9 | 5 | 4 | 0 |

| Placebo = 176 | 63.5 ± 14.4 | 176 | 34 | 14 | 20 | 0 | |||||

| PSP = 174 | 66.30 ± 12 | 174 | 21 | 13 | 8 | 0 | |||||

| Lai et al[37], 2019, Taiwan | Single-center, double blinded, unselected patients | 100 mg rectal indomethacin pre-ERCP + 100 post | 100 mg rectal indomethacin post-ERCP | Standard indications for ERCP | Indomethacin = 87 | 60.5 ± 16.9 | 33 | 4 | NA | NA | NA |

| Placebo = 75 | 59.3 ± 15.7 | 28 | 5 | ||||||||

| Sotoudehmanesh et al[60], 2019, Iran | Single-center, double blinded, unselected patients | 100 mg rectal indomethacin + 5 mg isosorbide | 100 mg rectal indomethacin + 5 mg isosorbide + pancreatic duct stent | Standard indications for ERCP | Indomethacin = 207 | 56.8 (17.2) | 120 | 33 | 27 | 6 | NA |

| PSP = 207 | 53.9 (16.8) | 131 | 26 | 22 | 4 | ||||||

| Sperna Weiland et al[61], 2021, Netherlands | Multicenter, double blinded, selected patients | 100 mg rectal diclofenac or indomethacin | 100 mg rectal diclofenac or indomethacin + hydration | Moderate to high risk of post-ERCP pancreatitis | Indomethacin = 425 | 60 (49-71) | 250 | 39 | 29 | 10 | NA |

| Indomethacin + hydration = 388 | 57 (44-71) | 232 | 30 | 27 | 3 | ||||||

| Hatami et al[39], 2018, Iran | Single-center, double blinded, selected patients | 100 mg indomethacin | 10 mL epinephrine (diluted to 1/10000 in saline) epinephrine + indomethacin | High-risk post-ERCP pancreatitis | Indomethacin = 6 | 58.06 ± 17.1 | 27 | 6 | 4 | 1 | 1 |

| Epinephrine = 68 | 59.59 ± 15.68 | 33 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Epinephrine + indomethacin = 58 | 59.62 ± 15.36 | 34 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Ref. | Total adverse events | Abdominal pain | Bleeding | Cholangitis | Mortality |

| Romano-Munive et al[50], 2021, Mexico | EI = 40 | 9 | 9 | 5 | 2 |

| WI = 41 | 5 | 3 | 10 | 6 | |

| Patai et al[22], 2017, Hungary | Indomethacin = 30 | NA | 9 | 2 | NA |

| Placebo = 42 | 3 | 2 | |||

| Elmunzer et al[35], 2012, United States | Indomethacin = 4 | NA | 4 | NA | NA |

| Placebo = 9 | 7 | ||||

| Levenick et al[51], 2016, United States | Indomethacin = 4 | NA | 4 | NA | 0 |

| Placebo = 6 | 6 | 3 | |||

| Liu et al[52], 2024, China | Indomethacin = NA | NA | NA | NA | 0 |

| Placebo = NA | 1 | ||||

| Guha et al[38], 2023, India | Indomethacin = 11 | 43 | 3 | NA | 3 |

| Placebo = 8 | 40 | 4 | 3 | ||

| Andrade-Dávila et al[33], 2015, Mexico | Indomethacin = 2 | NA | 2 | NA | NA |

| Placebo = 3 | 3 | ||||

| Qian et al[54], 2022, China | Indomethacin = 65 | NA | NA | 5 | NA |

| Placebo = 99 | 13 | ||||

| Wu et al[43], 2023, China | Indomethacin = 62 | NA | 45 | NA | 2 |

| Somatostatin = 21 | 18 | 3 | |||

| Somatostatin + indomethacin = 25 | 21 | ||||

| Placebo = 43 | 30 | ||||

| Fogel et al[36], 2020, United States | Indomethacin = 6 | NA | 6 | NA | NA |

| Placebo = 8 | 8 | ||||

| Kamal et al[57], 2019, United States, India | Indomethacin = 6 | NA | 0 | NA | 3 |

| Placebo = 8 | 10 | 3 | |||

| Luo et al[58], 2019, China | Indomethacin = 42 | NA | 4 | 8 | |

| Placebo = 44 | 6 | 9 | |||

| Mok et al[41], 2017, United States | NA | NA | NA | NA | 2 |

| 1 | |||||

| 2 | |||||

| 1 | |||||

| Sotoudehmanesh et al[59], 2014, Iran | NA | 1 | NA | NA | NA |

| 2 | |||||

| Wang et al[42], 2020, China | NA | NA | 4 | 4 | NA |

| 6 | 8 | ||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||

| Sperna Weiland et al[61], 2021, Netherlands | Indomethacin = 30 | NA | NA | NA | 12 |

| Indomethacin + hydration = 24 | 11 |

The risk of bias assessment is presented in Supplementary Figure 29. Fifteen studies had some concern regarding risk of bias, whereas the remaining fifteen studies had a low risk of bias across all domains. Most studies raised concerns about the randomization procedures and the participant recruitment processes. The overall quality of evidence was rated as high to moderate via the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation approach.

The analysis of the included studies revealed that rectal indomethacin did not significantly reduce the risk of PEP (RR = 0.85, 95%CI: 0.69-1.04, P = 0.12, I2 = 79%), despite significantly high heterogeneity (Figure 2).

Indomethacin did not reduce the risk of mild PEP (RR = 0.92, 95%CI: 0.74-1.14, P = 0.43, I2 = 55%) or moderate PEP (RR = 0.78, 95%CI: 0.59-1.02, P = 0.07, I2 = 28%), and severe PEP (RR = 1.12, 95%CI: 0.75-1.67, P = 0.57, I2 = 0%) in patients undergoing ERCP (Figure 3). The adverse events RR (RR = 0.97, 95%CI: 0.69-1.35; P = 0.84; I2 = 83%) was also not significantly different between the indomethacin group and the control group. Abdominal pain (RR = 1.14, 95%CI: 0.80-1.62; P = 0.47; I2 = 0%) and bleeding (RR = 1.07, 95%CI: 0.70-1.63; P = 0.77; I2 = 71%) also showed no differences. However, there was a significant difference in the number of patients with cholangitis (RR = 0.56, 95%CI: 0.34-0.93; P = 0.02; I2 = 0%). There was also no difference in the mortality rate (RR = 0.86, 95%CI: 0.56-1.33; P = 0.51; I2 = 0%) between the two groups. There was also no difference in the pooled MD of hospital stay (MD = 0.00, 95%CI: 0.03-0.02; P = 0.95; I2 = 0%) between the two groups (Supplementary Figures 1-6).

The results of the multivariate analysis also revealed that there was a significant difference in the number of cases of PEP between the two groups concerning patients with prior cholecystectomy (pooled RR = 0.42, 95%CI: 0.24-0.71; P = 0.001; I2 = 0%), a history of pancreatitis (RR = 0.67, 95%CI: 0.47-0.95; P = 0.03, I2 = 0%), difficult cannulation (RR = 0.62, 95%CI: 0.44-0.89; P = 0.009; I2 = 59%), pancreatic sphincterotomy (RR = 0.29, 95%CI: 0.14-0.48; P < 0.00001; I2 = 25%), biliary sphincterotomy (RR = 0.85, 95%CI: 0.74-0.99; P = 0.03; I2 = 0%), and a pancreatic duct stent (RR = 1.14, 95%CI: 1.19-1.67; P < 0.0001; I2 = 0%). However, there was no impact of patient age > 40 years (RR = 0.79, 95%CI: 0.59-1.05; P = 0.10; I2 = 62%), female sex (RR = 0.80, 95%CI: 0.60-1.07, P = 0.13, I2 = 56%), or trainee involvement (RR = 1.79, 95%CI: 0.89-3.60; P = 0.10, I2 = 84%) on PEP cases (Table 3 and Supplementary Figures 7-15).

| Outcomes | Studies | RR | 95%CI | P value | Heterogeneity |

| Age > 40 years | 13 | 0.79 | 0.59-1.05 | 0.10 | 62% |

| Female patients | 14 | 0.80 | 0.60-1.07 | 0.13 | 56% |

| Prior cholecystectomy | 4 | 0.42 | 0.24-0.71 | < 0.01 | 0% |

| History of pancreatitis | 7 | 0.67 | 0.47-0.95 | 0.03 | 0% |

| Difficult cannulation | 11 | 0.62 | 0.44-0.89 | < 0.01 | 59% |

| Pancreatic sphincterotomy | 9 | 0.29 | 0.18-0.46 | < 0.01 | 25% |

| Biliary sphincterotomy | 7 | 0.85 | 0.74-0.99 | 0.03 | 0% |

| Trainee involvement | 6 | 1.79 | 0.89-3.60 | 0.10 | 84% |

| Pancreatic duct stent | 6 | 1.41 | 1.19-1.67 | < 0.01 | 0% |

The positive impact of indomethacin on PEP was the same in all subgroups, including those that were given indome

Asymmetry in the funnel plot, especially the absence of studies at the bottom center, suggests possible publication bias, in which smaller studies with non-significant results may be neglected. However, the prevalence of studies on both sides of the center line, including those with negative impacts, suggests that if a bias exists, it may not be significant. While there are indications of potential publication bias, real heterogeneity between studies may also contribute to the observed pattern; that’s why this can be neglected (Supplementary Figures 22-28). Egger’s test results also showed that there is minor risk of bias (P > 0.05).

This meta-analysis of 30 RCTs, including 16977 patients, evaluated the efficacy and safety of rectal indomethacin in preventing PEP across diverse patient groups and clinical environments. Our data indicate that rectal indomethacin may confer a protective effect against PEP. However, the aggregate findings lacked statistical significance, and there was significant heterogeneity across the studies included. These advantages were noted across patient subgroups and indications for ERCP, accompanied by an excellent safety profile.

A preliminary analysis of all the trials (50 comparisons) that were included did not reveal a significant decrease in the number of cases of PEP between the two groups (RR = 0.85, 95%CI: 0.69-1.04; P = 0.12). The heterogeneity was sig

We performed subgroups analyses on the basis of indomethacin alone vs indomethacin combined, indomethacin combined vs control, indomethacin vs placebo, indomethacin combined vs placebo, indomethacin vs saline/saline combined, indomethacin vs glycerin/epinephrine or combined, indomethacin vs the indomethacin + stent, study groups with two arms vs studies with multiple arms, selected patients vs unselected patients, and patients aged < 60 vs patients aged > 60. But the results also suggested that the heterogeneity was higher in most of the analysis and we were unable to find the real cause of this heterogeneity.

According to multivariate analysis, rectal indomethacin significantly reduced the risk of PEP in certain groups of patients who had a history of cholecystectomy, pancreatitis, difficult cannulation, pancreatic sphincterotomy, biliary sphincterotomy, or pancreatic duct stenting. These results indicate that rectal indomethacin may be especially advan

Subgroup and sensitivity analyses revealed that the beneficial impact of rectal indomethacin on PEP was consistent across diverse trial designs, comparator groups, and patient demographics. The aggregated estimates remained consis

Rectal indomethacin should be considered alongside additional preventative measures for PEP. According to the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy/American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy guidelines, patients are classified as high-risk if they exhibit at least one definite risk factor or two or more likely risk factors[18,45-47] (Supplementary Table 3). Procedural methods such as guidewire-assisted cannulation, pancreatic duct stenting, and early precut sphincterotomy have been linked to a reduced risk[18,47]. Patient selection is most important because characteristics such as sphincter Oddi dysfunction, difficult cannulation, prior cholecystectomy, pancreatic sphincterotomy, biliary sphincterotomy, and a history of pancreatitis increase vulnerability, as demonstrated by the analysis[48]. A comprehensive strategy that includes pharmacologic prevention and risk assessment may yield the most significant advantage[8].

Our data demonstrated that the combination of indomethacin exhibited superior efficacy and reduced the risk of PEP compared with the control/placebo combination. Subgroup analysis demonstrated that indomethacin outperforms glycerin/epinephrine. A meta-analysis between indomethacin and topical epinephrine for PEP prevention also stated that combination of indomethacin and topical epinephrine also showed similar results[26]. Patients with a mean age over 60 years, as well as those with a high to moderate risk of pancreatitis, showed increased treatment efficacy. Another study between indomethacin and diclofenac in the prevention of PEP also showed that both performs similarly that align with our study results[22,49].

The meta-analysis suggested potential benefits of rectal indomethacin in reducing PEP risk, especially in moderate cases. However, study heterogeneity and inconsistent results necessitate further research. The evidence is strongest in high-risk patients, but given the safety profile and major society recommendations, many centers administer rectal NSAIDs universally. Future studies should focus on large-scale trials with standardized protocols, optimal dosing, and patient subgroups. Investigating the underlying mechanisms of the protective effect of indomethacin could refine its use and guide new prevention strategies.

This meta-analysis offers multiple strengths, such as a comprehensive literature review, rigorous study selection and data extraction processes, and thorough subgroup and sensitivity analyses. However, certain limits must be acknowledged. The significant heterogeneity among the included studies may restrict the generalizability of the findings and necessitate careful interpretation. Second, the quality of the included studies was inconsistent, with some exhibiting relatively small sample sizes or being conducted in single centers, potentially introducing bias. The optimal timing, dosage, and amount of rectal indomethacin administration for PEP prevention remain unclear and necessitate additional research. Some studies applied co-interventions (e.g., aggressive hydration, prophylactic pancreatic duct stenting, nitrates, topical epinephrine) that may have influenced the pooled results.

This meta-analysis found that rectal indomethacin did not show a statistically significant difference in the incidence of PEP. But the pharmacological safety profile appears favorable, with no significant increase in adverse events compared to controls. The evidence is strongest in high-risk patients, but given the safety profile and major society recommendations, many centers administer rectal NSAIDs universally. However, careful interpretation of these results is required due to the significant heterogeneity among studies.

| 1. | AbiMansour JP, Martin JA. Biliary Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2024;53:627-642. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Huang LY, Liu YX, Wu CR, Cui J, Zhang B. Application of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in biliary-pancreatic diseases. Chin Med J (Engl). 2009;122:2967-2972. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Akshintala VS, Kanthasamy K, Bhullar FA, Sperna Weiland CJ, Kamal A, Kochar B, Gurakar M, Ngamruengphong S, Kumbhari V, Brewer-Gutierrez OI, Kalloo AN, Khashab MA, van Geenen EM, Singh VK. Incidence, severity, and mortality of post-ERCP pancreatitis: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis of 145 randomized controlled trials. Gastrointest Endosc. 2023;98:1-6.e12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 30.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Mutneja HR, Vohra I, Go A, Bhurwal A, Katiyar V, Palomera Tejeda E, Thapa Chhetri K, Baig MA, Arora S, Attar B. Temporal trends and mortality of post-ERCP pancreatitis in the United States: a nationwide analysis. Endoscopy. 2021;53:357-366. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Cahyadi O, Tehami N, de-Madaria E, Siau K. Post-ERCP Pancreatitis: Prevention, Diagnosis and Management. Medicina (Kaunas). 2022;58:1261. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Khizar H, Hu Y, Wu Y, Ali K, Iqbal J, Zulqarnain M, Yang J. Efficacy and Safety of Radiofrequency Ablation Plus Stent Versus Stent-alone Treatments for Malignant Biliary Strictures: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2023;57:335-345. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ding X, Zhang F, Wang Y. Risk factors for post-ERCP pancreatitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Surgeon. 2015;13:218-229. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Akshintala VS, Sperna Weiland CJ, Bhullar FA, Kamal A, Kanthasamy K, Kuo A, Tomasetti C, Gurakar M, Drenth JPH, Yadav D, Elmunzer BJ, Reddy DN, Goenka MK, Kochhar R, Kalloo AN, Khashab MA, van Geenen EJM, Singh VK. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, intravenous fluids, pancreatic stents, or their combinations for the prevention of post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;6:733-742. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Shou-Xin Y, Shuai H, Fan-Guo K, Xing-Yuan D, Jia-Guo H, Tao P, Lin Q, Yan-Sheng S, Ting-Ting Y, Jing Z, Fang L, Hao-Liang Q, Man L. Rectal nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and pancreatic stents in preventing post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis in high-risk patients: A network meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99:e22672. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Sahar N, Ross A, Lakhtakia S, Coté GA, Neuhaus H, Bruno MJ, Haluszka O, Kozarek R, Ramchandani M, Beyna T, Poley JW, Maranki J, Freeman M, Kedia P, Tarnasky P; Pancreatic Stenting Registry Group. Reducing the risk of post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis using 4-Fr pancreatic plastic stents placed with common-type guidewires: Results from a prospective multinational registry. Dig Endosc. 2019;31:299-306. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Borrelli de Andreis F, Mascagni P, Schepis T, Attili F, Tringali A, Costamagna G, Boškoski I. Prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis: current strategies and novel perspectives. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2023;16:17562848231155984. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Park TY, Oh HC, Fogel EL, Lehman GA. Prevention of post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis with rectal non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Korean J Intern Med. 2020;35:535-543. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Pekgöz M. Post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis: A systematic review for prevention and treatment. World J Gastroenterol. 2019;25:4019-4042. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Akshintala VS, Boparai IS, Barakat MT, Husain SZ. Post Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography Pancreatitis: Novel Mechanisms and Prevention by Drugs. United European Gastroenterol J. 2025;13:78-85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Wang AY, Strand DS, Shami VM. Prevention of Post-Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography Pancreatitis: Medications and Techniques. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:1521-1532.e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Oh HC, Kang H, Park TY, Choi GJ, Lehman GA. Prevention of post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis with a combination of pharmacological agents based on rectal non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;36:1403-1413. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Yu S, Shen X, Li L, Bi X, Chen P, Wu W. Rectal indomethacin and diclofenac are equally efficient in preventing pancreatitis following endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in average-risk patients. JGH Open. 2021;5:1119-1126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Buxbaum JL, Freeman M, Amateau SK, Chalhoub JM, Coelho-Prabhu N, Desai M, Elhanafi SE, Forbes N, Fujii-Lau LL, Kohli DR, Kwon RS, Machicado JD, Marya NB, Pawa S, Ruan WH, Sheth SG, Thiruvengadam NR, Thosani NC, Qumseya BJ; (ASGE Standards of Practice Committee Chair). American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy guideline on post-ERCP pancreatitis prevention strategies: summary and recommendations. Gastrointest Endosc. 2023;97:153-162. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 36.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Zuo J, Li H, Zhang S, Li P. Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs for the Prevention of Post-endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography Pancreatitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2024;69:3134-3146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Elmunzer BJ, Foster LD, Serrano J, Coté GA, Edmundowicz SA, Wani S, Shah R, Bang JY, Varadarajulu S, Singh VK, Khashab M, Kwon RS, Scheiman JM, Willingham FF, Keilin SA, Papachristou GI, Chak A, Slivka A, Mullady D, Kushnir V, Buxbaum J, Keswani R, Gardner TB, Forbes N, Rastogi A, Ross A, Law J, Yachimski P, Chen YI, Barkun A, Smith ZL, Petersen B, Wang AY, Saltzman JR, Spitzer RL, Ordiah C, Spino C, Durkalski-Mauldin V; SVI Study Group. Indomethacin with or without prophylactic pancreatic stent placement to prevent pancreatitis after ERCP: a randomised non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2024;403:450-458. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 32.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Makhzangy HE, Samy S, Shehata M, Albuhiri A, Khairy A. Combined rectal indomethacin and intravenous saline hydration in post-ERCP pancreatitis prophylaxis. Arab J Gastroenterol. 2022;23:95-101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Patai Á, Solymosi N, Mohácsi L, Patai ÁV. Indomethacin and diclofenac in the prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective controlled trials. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;85:1144-1156.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Sotoudehmanesh R, Khatibian M, Kolahdoozan S, Ainechi S, Malboosbaf R, Nouraie M. Indomethacin may reduce the incidence and severity of acute pancreatitis after ERCP. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:978-983. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in RCA: 155] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 24. | Márta K, Gede N, Szakács Z, Solymár M, Hegyi PJ, Tél B, Erőss B, Vincze Á, Arvanitakis M, Boškoski I, Bruno MJ, Hegyi P. Combined use of indomethacin and hydration is the best conservative approach for post-ERCP pancreatitis prevention: A network meta-analysis. Pancreatology. 2021;21:1247-1255. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 25. | Yang J, Wang W, Liu C, Zhao Y, Ren M, He S. Rectal Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs for Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography Postoperative Pancreatitis Prevention: A Network Meta-Analysis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2020;54:305-313. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Aziz M, Ghanim M, Sheikh T, Sharma S, Ghazaleh S, Fatima R, Khan Z, Lee-Smith W, Nawras A. Rectal indomethacin with topical epinephrine versus indomethacin alone for preventing Post-ERCP pancreatitis - A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pancreatology. 2020;20:356-361. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Moher D. Updating guidance for reporting systematic reviews: development of the PRISMA 2020 statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2021;134:103-112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 407] [Cited by in RCA: 1393] [Article Influence: 278.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, Elbers RG, Blencowe NS, Boutron I, Cates CJ, Cheng HY, Corbett MS, Eldridge SM, Emberson JR, Hernán MA, Hopewell S, Hróbjartsson A, Junqueira DR, Jüni P, Kirkham JJ, Lasserson T, Li T, McAleenan A, Reeves BC, Shepperd S, Shrier I, Stewart LA, Tilling K, White IR, Whiting PF, Higgins JPT. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2019;366:l4898. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6581] [Cited by in RCA: 18723] [Article Influence: 2674.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21:1539-1558. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21630] [Cited by in RCA: 27029] [Article Influence: 1126.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Lin L, Chu H. Rejoinder to "quantifying publication bias in meta-analysis". Biometrics. 2018;74:801-802. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Abdi S, Qobadighadikolaei R, Jamali F, Shahrokhi M, Dastan F, Abbasinazari M. Effect of CoQ10 Addition to Rectal Indomethacin on Clinical Pancreatitis and Related Biomarkers in Post-endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography. J Cell Mol Anesth. 2024;9:e145362. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 32. | Alavinejad P, Tran NN, Eslami O, Shaarawy OE, Hormati A, Seiedian SS, Parsi A, Ahmed MH, Behl NS, Abravesh AA, Tran QT, Vignesh S, Salman S, Sakr N, Ara TF, Hajiani E, Hashemi SJ, Patai ÁV, Butt AS, Lee SH. Oral N-acetyl cysteine versus rectal indomethacin for prevention of post ERCP pancreatitis: A multicenter multinational randomized controlled trial. Arq Gastroenterol. 2022;59:508-512. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Andrade-Dávila VF, Chávez-Tostado M, Dávalos-Cobián C, García-Correa J, Montaño-Loza A, Fuentes-Orozco C, Macías-Amezcua MD, García-Rentería J, Rendón-Félix J, Cortés-Lares JA, Ambriz-González G, Cortés-Flores AO, Alvarez-Villaseñor Adel S, González-Ojeda A. Rectal indomethacin versus placebo to reduce the incidence of pancreatitis after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography: results of a controlled clinical trial. BMC Gastroenterol. 2015;15:85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Döbrönte Z, Szepes Z, Izbéki F, Gervain J, Lakatos L, Pécsi G, Ihász M, Lakner L, Toldy E, Czakó L. Is rectal indomethacin effective in preventing of post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis? World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:10151-10157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Elmunzer BJ, Scheiman JM, Lehman GA, Chak A, Mosler P, Higgins PD, Hayward RA, Romagnuolo J, Elta GH, Sherman S, Waljee AK, Repaka A, Atkinson MR, Cote GA, Kwon RS, McHenry L, Piraka CR, Wamsteker EJ, Watkins JL, Korsnes SJ, Schmidt SE, Turner SM, Nicholson S, Fogel EL; U. S. Cooperative for Outcomes Research in Endoscopy (USCORE). A randomized trial of rectal indomethacin to prevent post-ERCP pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1414-1422. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 478] [Cited by in RCA: 530] [Article Influence: 37.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Fogel EL, Lehman GA, Tarnasky P, Cote GA, Schmidt SE, Waljee AK, Higgins PDR, Watkins JL, Sherman S, Kwon RSY, Elta GH, Easler JJ, Pleskow DK, Scheiman JM, El Hajj II, Guda NM, Gromski MA, McHenry L Jr, Arol S, Korsnes S, Suarez AL, Spitzer R, Miller M, Hofbauer M, Elmunzer BJ; US Cooperative for Outcomes Research in Endoscopy (USCORE). Rectal indometacin dose escalation for prevention of pancreatitis after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in high-risk patients: a double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5:132-141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Lai JH, Hung CY, Chu CH, Chen CJ, Lin HH, Lin HJ, Lin CC. A randomized trial comparing the efficacy of single-dose and double-dose administration of rectal indomethacin in preventing post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019;98:e15742. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Guha P, Patra PS, Misra D, Ahammed SM, Sarkar R, Dhali GK, Ray S, Das K. An Open-Label Randomized Controlled Trial Comparing Effectiveness of Aggressive Hydration Versus High-dose Rectal Indomethacin in the Prevention of Postendoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatographic Pancreatitis (AHRI-PEP). J Clin Gastroenterol. 2023;57:524-530. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Hatami B, Kashfi SMH, Abbasinazari M, Nazemalhosseini Mojarad E, Pourhoseingholi MA, Zali MR, Mohammad Alizadeh AH. Epinephrine in the Prevention of Post-Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography Pancreatitis: A Preliminary Study. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2018;12:125-136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Hosseini M, Shalchiantabrizi P, Yektaroudy K, Dadgarmoghaddam M, Salari M. Prophylactic Effect of Rectal Indomethacin Administration, with and without Intravenous Hydration, on Development of Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography Pancreatitis Episodes: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Arch Iran Med. 2016;19:538-543. [PubMed] |

| 41. | Mok SRS, Ho HC, Shah P, Patel M, Gaughan JP, Elfant AB. Lactated Ringer's solution in combination with rectal indomethacin for prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis and readmission: a prospective randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;85:1005-1013. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Wang Y, Xu B, Zhang W, Lin J, Li G, Qiu W, Wang Y, Sun D, Wang Y. Prophylactic effect of rectal indomethacin plus nitroglycerin administration for preventing pancreatitis after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in female patients. Ann Palliat Med. 2020;9:4029-4037. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Wu Z, Xiao G, Wang G, Xiong L, Qiu P, Tan S. Effects of Somatostatin and Indomethacin Mono or Combination Therapy on High-risk Hyperamylasemia and Post-pancreatitis Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography Patients: A Randomized Study. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2023;33:474-479. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Mohammad Alizadeh AH, Abbasinazari M, Hatami B, Abdi S, Ahmadpour F, Dabir S, Nematollahi A, Fatehi S, Pourhoseingholi MA. Comparison of rectal indomethacin, diclofenac, and naproxen for the prevention of post endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;29:349-354. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | ASGE Standards of Practice Committee; Buxbaum JL, Freeman M, Amateau SK, Chalhoub JM, Chowdhury A, Coelho-Prabhu N, Das R, Desai M, Elhanafi SE, Forbes N, Fujii-Lau LL, Kohli DR, Kwon RS, Machicado JD, Marya NB, Pawa S, Ruan WH, Sadik J, Sheth SG, Thiruvengadam NR, Thosani NC, Zhou S, Qumseya BJ; (ASGE Standards of Practice Committee Chair). American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy guideline on post-ERCP pancreatitis prevention strategies: methodology and review of evidence. Gastrointest Endosc. 2023;97:163-183.e40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Dumonceau JM, Andriulli A, Elmunzer BJ, Mariani A, Meister T, Deviere J, Marek T, Baron TH, Hassan C, Testoni PA, Kapral C; European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. Prophylaxis of post-ERCP pancreatitis: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline - updated June 2014. Endoscopy. 2014;46:799-815. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 378] [Cited by in RCA: 418] [Article Influence: 34.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Dumonceau JM, Kapral C, Aabakken L, Papanikolaou IS, Tringali A, Vanbiervliet G, Beyna T, Dinis-Ribeiro M, Hritz I, Mariani A, Paspatis G, Radaelli F, Lakhtakia S, Veitch AM, van Hooft JE. ERCP-related adverse events: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline. Endoscopy. 2020;52:127-149. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 707] [Cited by in RCA: 588] [Article Influence: 98.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 48. | Mine T, Morizane T, Kawaguchi Y, Akashi R, Hanada K, Ito T, Kanno A, Kida M, Miyagawa H, Yamaguchi T, Mayumi T, Takeyama Y, Shimosegawa T. Clinical practice guideline for post-ERCP pancreatitis. J Gastroenterol. 2017;52:1013-1022. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Sethi S, Sethi N, Wadhwa V, Garud S, Brown A. A meta-analysis on the role of rectal diclofenac and indomethacin in the prevention of post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2014;43:190-197. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Romano-Munive AF, García-Correa JJ, García-Contreras LF, Ramírez-García J, Uscanga L, Barbero-Becerra VJ, Moctezuma-Velázquez C, Ochoa-Rubí JA, Toledo-Cuque J, Vázquez-Anaya G, Keil-Ríos D, Grajales-Figueroa G, Ramírez-Luna MÁ, Valdovinos-Andraca F, Zamora-Nava LE, Tellez-Avila F. Can topical epinephrine application to the papilla prevent pancreatitis after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography? Results from a double blind, multicentre, placebo controlled, randomised clinical trial. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2021;8:e000562. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Levenick JM, Gordon SR, Fadden LL, Levy LC, Rockacy MJ, Hyder SM, Lacy BE, Bensen SP, Parr DD, Gardner TB. Rectal Indomethacin Does Not Prevent Post-ERCP Pancreatitis in Consecutive Patients. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:911-7; quiz e19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 153] [Article Influence: 15.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Liu KJ, Hu Y, Guo SB. Effect of rectal indomethacin on the prevention of pancreatitis after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography for choledocholithiasis: a prospective randomized clinical trial. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2024;116:20-208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Li L, Liu M, Zhang T, Jia Y, Zhang Y, Yuan H, Zhang G, He C. Indomethacin down-regulating HMGB1 and TNF-α to prevent pancreatitis after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2019;54:793-799. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Qian YY, Ru N, Chen H, Zou WB, Wu H, Pan J, Li B, Xin L, Guo JY, Tang XY, Hu LH, Jin ZD, Wang D, Du YQ, Wang LW, Li ZS, Liao Z. Rectal indometacin to prevent pancreatitis after extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (RIPEP): a single-centre, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;7:238-244. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Norouzi A, Ghasem Poori E, Kaabe S, Norouzi Z, Sohrabi A, Amlashi FI, Tavasoli S, Besharat S, Ezabadi Z, Amiriani T. Effect of Adding Intravenous Somatostatin to Rectal Indomethacin on Post-Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) Pancreatitis in High-risk Patients: A Double-blind Randomized Placebo-controlled Clinical Trial. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2023;57:204-210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Sadeghi A, Jafari-Moghaddam R, Ataei S, Asadiafrooz M, Abbasinazari M. Role of vitamin C and rectal indomethacin in preventing and alleviating post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis: a clinical study. Clin Endosc. 2023;56:214-220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Kamal A, Akshintala VS, Talukdar R, Goenka MK, Kochhar R, Lakhtakia S, Ramchandani MK, Sinha S, Goud R, Rai VK, Tandan M, Gupta R, Elmunzer BJ, Ngamruengphong S, Kumbhari V, Khashab MA, Kalloo AN, Reddy DN, Singh VK. A Randomized Trial of Topical Epinephrine and Rectal Indomethacin for Preventing Post-Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography Pancreatitis in High-Risk Patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019;114:339-347. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Luo H, Wang X, Zhang R, Liang S, Kang X, Zhang X, Lou Q, Xiong K, Yang J, Si L, Liu W, Liu Y, Zhou Y, Wang S, Yang M, Chen W, Han Y, Shang G, Yang X, He Y, Zou Q, Guo W, Dai Y, Zeng W, Zhu X, Gong R, Li X, Nie Z, Wang Q, Wang L, Pan Y, Guo X, Fan D. Rectal Indomethacin and Spraying of Duodenal Papilla With Epinephrine Increases Risk of Pancreatitis Following Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17:1597-1606.e5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Sotoudehmanesh R, Eloubeidi MA, Asgari AA, Farsinejad M, Khatibian M. A randomized trial of rectal indomethacin and sublingual nitrates to prevent post-ERCP pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:903-909. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Sotoudehmanesh R, Ali-Asgari A, Khatibian M, Mohamadnejad M, Merat S, Sadeghi A, Keshtkar A, Bagheri M, Delavari A, Amani M, Vahedi H, Nasseri-Moghaddam S, Sima A, Eloubeidi MA, Malekzadeh R. Pharmacological prophylaxis versus pancreatic duct stenting plus pharmacological prophylaxis for prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis in high risk patients: a randomized trial. Endoscopy. 2019;51:915-921. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Sperna Weiland CJ, Smeets XJNM, Kievit W, Verdonk RC, Poen AC, Bhalla A, Venneman NG, Witteman BJM, da Costa DW, van Eijck BC, Schwartz MP, Römkens TEH, Vrolijk JM, Hadithi M, Voorburg AMCJ, Baak LC, Thijs WJ, van Wanrooij RL, Tan ACITL, Seerden TCJ, Keulemans YCA, de Wijkerslooth TR, van de Vrie W, van der Schaar P, van Dijk SM, Hallensleben NDL, Sperna Weiland RL, Timmerhuis HC, Umans DS, van Hooft JE, van Goor H, van Santvoort HC, Besselink MG, Bruno MJ, Fockens P, Drenth JPH, van Geenen EJM; Dutch Pancreatitis Study Group. Aggressive fluid hydration plus non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs versus non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs alone for post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis (FLUYT): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;6:350-358. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/