Published online Jan 7, 2026. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v32.i1.113181

Revised: October 3, 2025

Accepted: November 17, 2025

Published online: January 7, 2026

Processing time: 137 Days and 13 Hours

Chronic atrophic gastritis (CAG) is a clinically refractory gastric disease often cha

To investigate the therapeutic mechanisms of AWD against CAG from an inte

In this study, N-methyl-N’-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine was used to establish a CAG rat model. Serum-derived con

AWD notably reduced serum levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1β, IL-18, tumor necrosis factor-α, and lipopolysaccharide, demonstrating significant statistical differences (all P < 0.01). Additionally, AWD substantially inhibited NLRP3 mRNA expression in gastric mucosal tissue (P < 0.01) and concurrently decreased the protein abundance of NLRP3, IL-1β, and caspase-1 (all P < 0.01), thereby suppressing inflammasome signaling activation. GM analysis indicated that AWD intervention significantly increased the relative abundance of be

AWD alleviates the pathological progression of CAG through multi-target synergistic mechanisms. On one hand, AWD directly suppresses gastric mucosal inflammation by inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome activation. On the other hand, AWD remodels intestinal microbiota-metabolite homeostasis, enhances intestinal barrier function, and regulates mucosal immune responses.

Core Tip: Chronic atrophic gastritis (CAG) is a precancerous lesion of the stomach, with a prevalence of 34.7% in China and a risk of gastric cancer that is 4 times that of ordinary people. Existing therapies have high side effects and cannot reverse pathological damage. Traditional Chinese medicine Anwei decoction inhibits NLRP3 inflammasomes, reshapes the balance of microflora, breaks through the limitations of single targets, and provides a new strategy for CAG treatment, which can delay cancer and reverse pathological damage through the regulation of the “microbiota-metabolism-immunity” network.

- Citation: Qin H, Liu YY, Li Q, Wei SY, Huang LY, Zhou CF, Tan LY, Zhang JW, Wu DK, Tang YM. Anwei decoction alleviates chronic atrophic gastritis by modulating the gut microbiota-metabolite axis and NLRP3 inflammasome activity. World J Gastroenterol 2026; 32(1): 113181

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v32/i1/113181.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v32.i1.113181

Chronic atrophic gastritis (CAG) is a precancerous lesion characterized by chronic inflammatory infiltration of the gastric mucosa, glandular atrophy, and intestinal metaplasia[1]. Its global prevalence ranges from 20% to 40%, with East Asia showing notably high rates (34.7% in China)[2,3]. Studies indicate that patients with CAG have a four-fold greater risk of gastric cancer compared to healthy individuals[4]. Gastric cancer remains among the top three cancers globally in terms of mortality rates[5]. Therefore, developing effective interventions to control inflammation and delay carcinogenesis is of significant clinical importance. Current CAG management primarily involves lifestyle interventions and pharmacotherapy, such as proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), histamine H2 receptor antagonists, Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) eradication therapy, and gastric mucosal protective agents[6]. However, prolonged PPI use may increase the risks of gastric cancer[7] and cardiovascular events[8]. Standard H. pylori eradication regimens face resistance issues that compromise efficacy and may exacerbate complications[9]. Additionally, existing treatments can alleviate symptoms and eliminate H. pylori but cannot reverse established gastric mucosal atrophy or intestinal metaplasia[10]. Some patients continue to experience lesion progression even after successful H. pylori eradication.

Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) has demonstrated clear advantages in enhancing gastric mucosal defense, improving gastric microcirculation[11], regulating inflammation and immune responses, and modulating intestinal microbiota[12]. Jianwei Xiaoyan Granule has shown efficacy by inhibiting angiogenesis through the hypoxia inducible factor-1α-vascular endothelial growth factor pathway and reducing gastric mucosal inflammation[13]. Additionally, the incidence of adverse reactions associated with TCM is significantly lower compared to Western medicine. The therapeutic benefits of TCM are attributed to its multi-system regulatory effects, which not only enhance the overall functional status of patients but also strengthen immune function. This dual mechanism allows TCM to effectively relieve clinical symptoms and enhance patient tolerance, making it suitable for long-term chronic disease management.

In recent years, TCM’s advantages in treating chronic inflammatory diseases have gained attention. Anwei decoction (AWD), developed by Professor Lin PX, a renowned Chinese medicine physician, exemplifies TCM prescriptions used to treat chronic gastric diseases. Based on the principles of “strengthening the spleen, clearing heat, resolving blood stasis, and promoting tissue regeneration”, AWD comprises ten traditional herbal medicines, including Coptis chinensis, Pinellia ternata, dried ginger, white peony, lily, black medicine, salvia, coix seed, licorice, and woody fragrance. According to TCM theory, CAG primarily results from spleen and stomach qi deficiency combined with dampness, heat, and blood stasis. In this prescription, Astragalus and Coptis chinensis is the principal herb, effectively tonifying qi, strengthening the spleen, and clearing heat and dampness. Pinellia ternata strengthens the spleen and invigorates qi, while salvia promotes blood circulation and eliminates stasis. The balanced combination of these herbs aligns closely with the etiology and pathogenesis of CAG. Previous experiments by our research group demonstrated that AWD improves the intestinal epithelial cell microenvironment by regulating the expression of glucose regulated protein 78, phosphoenolpyruvate carboxy kinase, ATF6, CCAAT/enhancer binding protein homologous protein, and caspase 12 and alleviates gastric mucosal pathology through autophagy[14]. Clinically, AWD is widely employed for gastric diseases, significantly reducing gastric discomfort and promoting mucosal repair. However, its multi-target mechanisms still require systematic clarification.

Gut microbiota (GM) imbalance contributes to the progression of CAG through two primary pathways. Firstly, dysbiosis initiates NLRP3 inflammasome activation, resulting in elevated secretion of interleukin (IL)-1β and IL-18. Secondly, it decreases gastrin production, causing hypoacidity and subsequently creating a self-perpetuating cycle[15]. H. pylori infection activates the NLRP3 inflammasome through stimulation of the Toll-like receptor (TLR) 2/4-nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-κB) signaling axis. Additionally, H. pylori-derived virulence factors provoke the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), facilitating inflammasome formation, and exacerbating inflammation via caspase-1-dependent pyroptosis and the secretion of IL-1β and IL-18[16]. Importantly, the NLRP3/IL-1β signaling cascade triggers gastric epithelial cell proliferation through activation of NF-κB and signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) pathways, promoting intestinal metaplasia, which is recognized as a precancerous gastric stomach[17].

Recent studies indicate that TCM treats CAG by regulating immune responses, improving the gastric mucosal environment, and modulating GM[18]. Inflammation plays a crucial role in the initiation and progression of CAG[19]. Activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome is central to CAG pathogenesis, promoting inflammation and gastric epithelial dysplasia via the caspase-1/IL-1β/IL-18 axis[20,21]. H. pylori triggers NLRP3 inflammasome activation through the TLR2/4-NF-κB-ROS pathway, subsequently enhancing inflammation through cleavage of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β and IL-18 and inducing pyroptotic cell death[22]. The NLRP3 inflammasome also activates downstream caspase-1, converting pro-IL-1β into mature IL-1β, which then stimulates the STAT3 and NF-κB pathways in an autocrine or paracrine manner, promoting abnormal gastric epithelial proliferation and subsequent intestinal metaplasia[23]. Moreover, GM is closely associated with host health, and its dysregulation contributes to CAG development[24]. Additionally, altered gut microbial metabolites can influence host physiological and pathological processes.

The integration of multi-omics approaches, including 16S rRNA sequencing, metabolomics, and bioinformatics, has become a powerful paradigm for elucidating the complexity of chronic diseases[25]. In this study, we applied such an integrated strategy to investigate the mechanism of AWD. An interactive regulatory network of “GM-metabolism-immunity” was constructed, enhancing the comprehensiveness and credibility of the findings. Furthermore, AWD significantly reduced gastric mucosal inflammation by modulating multiple metabolic pathways, including the Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus infection pathway, autophagy-related pathways, glycerophospholipid metabolism, and endocrine resistance. These discoveries expand the understanding of inflammatory regulatory pathways and provide novel therapeutic targets and intervention strategies for CAG. AWD also restores gastrointestinal microenvironment balance by targeting the GM-metabolite axis, offering a new perspective of “microecological regulation” for CAG treatment and overcoming limitations of existing therapies involving acid suppression and antibiotics. Additionally, AWD inhibits NLRP3 inflammasome activity, reducing the risk of CAG progression to gastric cancer and preventing malignant transformation. This study integrates the multi-dimensional “microbiota-metabolism-inflammation” re

Fifty healthy specific pathogen free (SPF)-grade Wistar rats (25 males and 25 females, 6 weeks old, weight 150 ± 20 g) were provided by Hunan Tianqin Biotechnology Co., Ltd. [production license number: No. SCXK (Xiang) 2019-0013]. All experimental procedures complied rigorously with the Animal Ethics Code for Laboratory Welfare [animal use license No. SYXK (Gui) 2019-0001] and were officially authorized by the Animal Ethics Committee at Guangxi University of Traditional Chinese Medicine (approval No. DW20211117-178).

To minimize the confounding effects of diet and environment on the GM, all experimental rats were housed in the same SPF-grade facility under strictly controlled environmental conditions. They were allowed free access to the same standard feed, and rats from different experimental groups were randomly co-housed in different cages on the same rack to avoid cage effects.

AWD consists of the following medicinal herbs: Coptis chinensis (3 g), Pinellia ternata (9 g), ginger (3 g), white peony (10 g), lily (10 g), black medicine (6 g), Salvia miltiorrhiza (10 g), coix seed (15 g), licorice root (5 g), and muxiang (5 g). All herbal ingredients were obtained from the Chinese Medicine Pharmacy at Ruikang Hospital, which is affiliated with Guangxi University of Chinese Medicine.

For AWD preparation, herbs were added to 1000 mL distilled water. The mixture was boiled over high heat and then simmered for 30 minutes. After the initial decoction, the solution was filtered through gauze. The herbs were decocted a second time using the same procedure, and both filtrates were combined. The final solution was concentrated to obtain AWD at 2 g crude drug per mL for subsequent experiments.

The positive control group received Weifuchun capsules (WFC) (Hangzhou Huqingyutang Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., National Drug Approval No. Z20090697, 0.35 g per capsule). This medication has a well-established efficacy and strong evidence-based support. It was officially approved by the China Food and Drug Administration in 1982 and is currently the only Chinese patent medicine approved for the treatment of precancerous lesions of gastric cancer in China. It has been included in authoritative documents such as the consensus on integrated traditional Chinese and western medicine diagnosis and treatment of chronic gastritis in China and the expert consensus on clinical application of Weifuchun in treating precancerous lesions of gastric cancer, with a clearly defined clinical position.

The animal dosage of AWD in this study (10.7 g/kg) was converted from its clinical human dosage using the body surface area normalization method. The routine daily clinical dosage of AWD is one dose per day, with the total amount of medicinal materials per dose approximately 102 g. Based on an average adult weight of 60 kg, the clinical equivalent dosage is approximately 1.7 g/kg. According to the conversion factor between humans and rats for body surface area from a simple practice guide for dose conversion between animals and humans (typically 6.3), the equivalent dosage for rats was calculated as: Clinical equivalent dosage (g/kg) × 6.3 approximately 10.7 g/kg/day[26]. The animal dosage of WFC (0.43 g/kg) was also calculated using the same method.

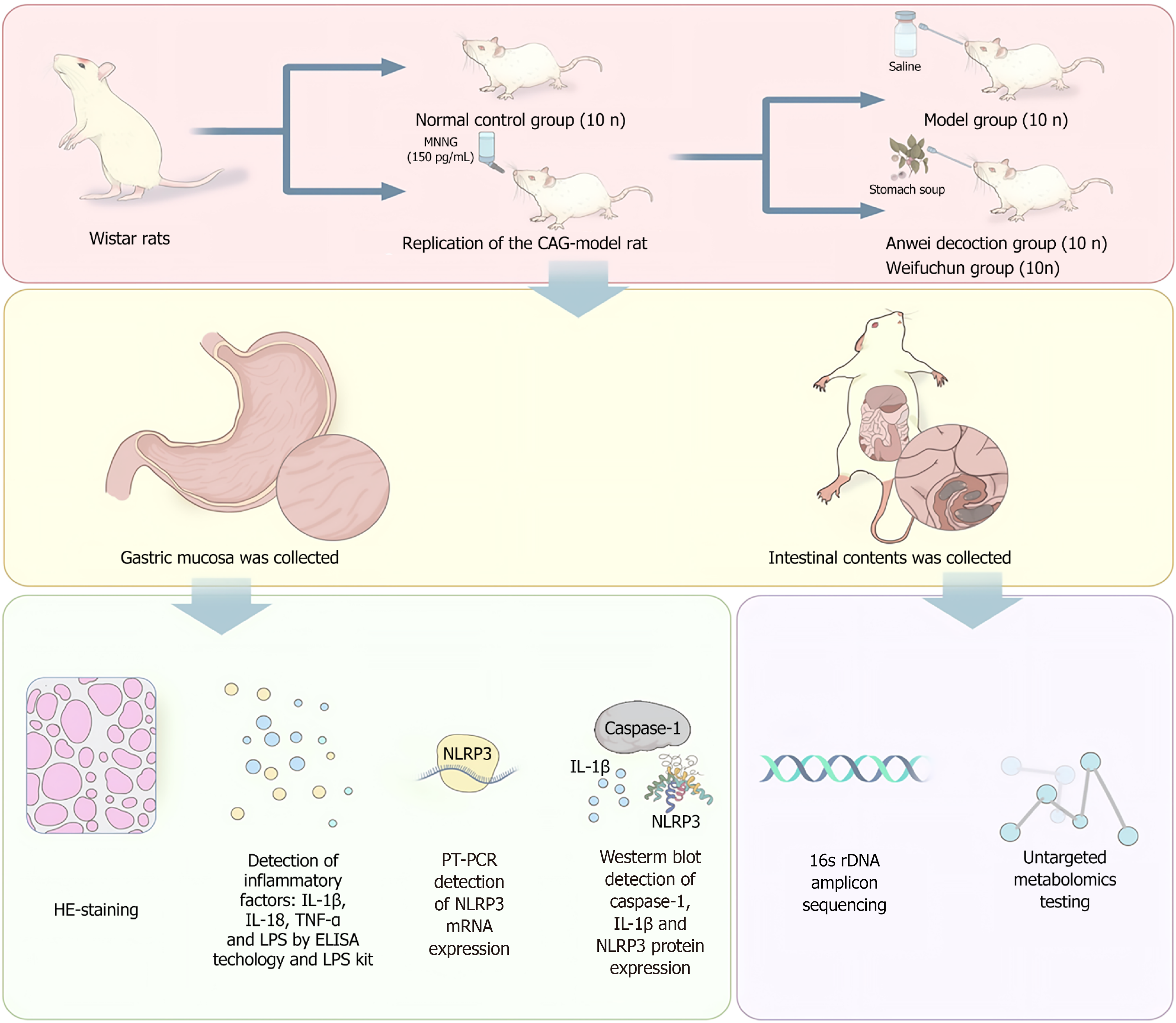

The experimental design (Figure 1) included three groups: A normal control group (NC), a model group (MD), an AWD intervention group, and a WFC intervention group. The CAG rat model was established according to a previously described method[14]. After successful model establishment, rats in the AWD group received AWD (10.71 g/kg), WFC (0.43 g/kg) by gavage daily for 8 consecutive weeks. Gastric mucosal tissues from each group were collected the day after the drug intervention. Histopathological examination of gastric mucosal tissues was performed using hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining. Serum concentrations of inflammatory markers [IL-1β, IL-18, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, and lipopolysaccharide (LPS)] were quantified through enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and an LPS detection kit. Expression levels of NLRP3 inflammasome messenger RNA (mRNA) were assessed using quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR), while Western blotting (WB) was employed to determine protein expression levels of caspase-1, IL-1β, and NLRP3. Additionally, intestinal contents were collected for 16S rDNA amplicon sequencing and non-targeted metabolomics to comprehensively evaluate AWD’s effects on GM and metabolite profiles.

After an initial adaptive feeding period of one week, fifty SPF-grade Wistar rats, evenly divided by sex, were randomly allocated into two distinct groups: NC group (n = 10) and MD group (n = 50). The CAG model was established by administering N-methyl-N’-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine (MNNG) dissolved in drinking water at a concentration of 150 μg/mL for 24 weeks. To control the daily intake of MNNG, rats were individually housed and provided with a graduated drinking bottle. Every day, 40 mL of either MNNG solution (MD group) or plain water (NC group) was provided per rat, and the remaining volume was recorded to monitor consumption. Starting from the 8th week after modeling initiation, two rats from the MD group were randomly selected every two weeks for gastric histopathological assessment via HE staining to monitor lesion progression. At the 24th week, gastric mucosal specimens were collected for HE staining, and the pathological status was quantitatively evaluated according to the updated Sydney system. The results indicated successful construction of the CAG rat model. Rats in the MD group scoring ≥ 2 (moderate to severe) in either glandular atrophy or chronic inflammatory infiltration were considered successful models. Based on this criterion, 45 out of 50 rats were successfully modeled, yielding a modeling success rate of 90%. All subsequent interventions and analyses were performed on these 45 successfully modeled rats and the 10 NC rats.

All data were presented as mean ± SD from three independent repetitions. SPSS 22.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, United States) was used to analyze the data. Data between two groups were analyzed using the t test, and the quantitative data in multiple groups were tested by one-way analysis of variance. Differences were defined as statistically significant at P < 0.05.

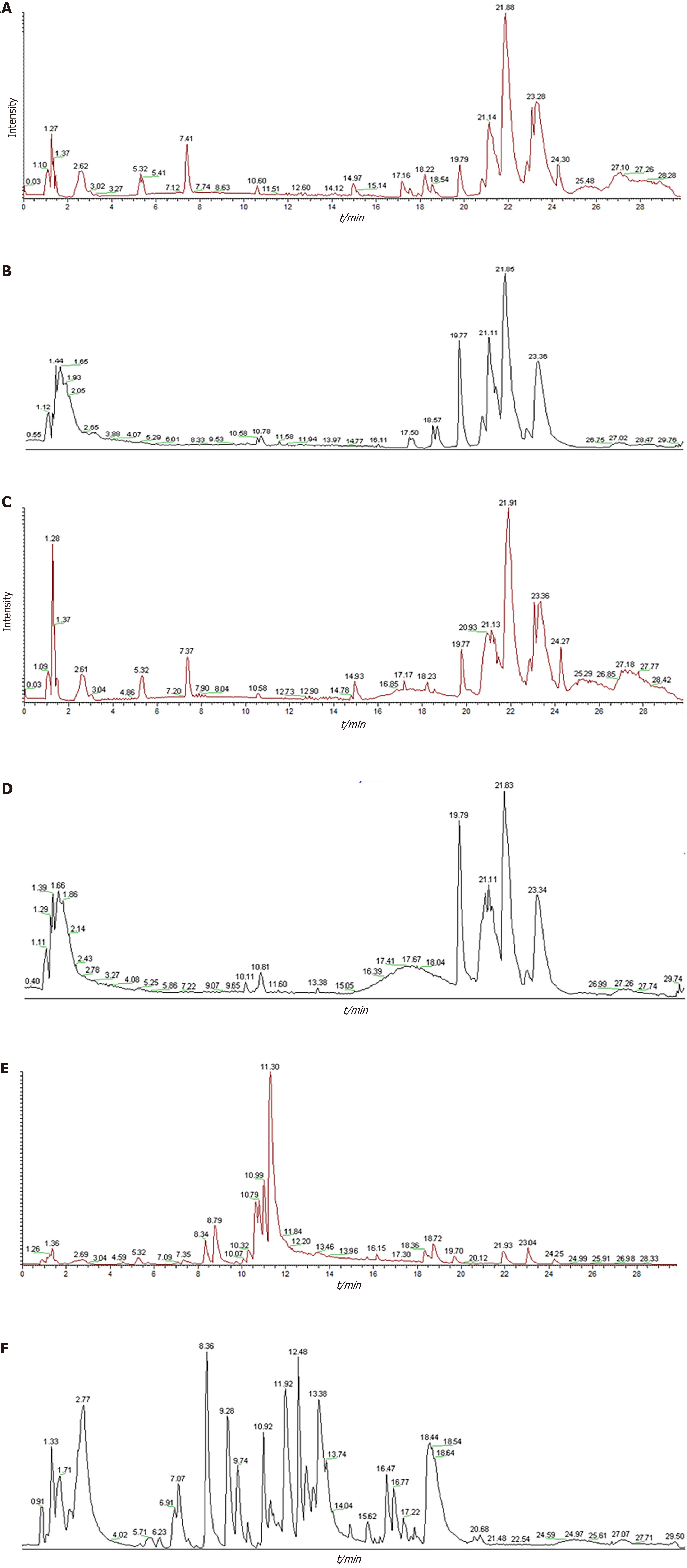

Ultra-high performance liquid chromatography with quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry analysis identified AWD components in medicated serum. Nineteen serum-migrating compounds (Table 1) were successfully identified by acquiring total ion chromatograms (Figure 2) in positive and negative ion modes. Relevant studies have shown that these compounds, such as isoliquiritigenin and caffeic acid, exhibit significant anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects[27-30].

| No | Compound | Reference lon | Formula | RT/m | m/z (actual) | m/z (theoretical) | Annotation MW | Calculate MW | δ/ppm | Sort |

| 1 | Isoliquiritigenin[1] | [M+H]+1 | C15H12O4 | 12.241 | 257.08105 | 257.08054 | 256.07356 | 256.07378 | 0.00022 | Flavonoids |

| 2 | Methyl succinic acid[2] | [M-H]-1 | C5H8O4 | 6.224 | 131.0338 | 131.03375 | 132.04226 | 132.04107 | -0.00118 | Dicarboxylic acid |

| 3 | 4-oxoproline[3] | [M-H]-1 | C5H7NO3 | 2.761 | 128.03412 | 128.03406 | 129.04259 | 129.0414 | -0.0012 | Amino acids |

| 4 | Caffeic acid[4] | [M+H]+1 | C9H8O4 | 18.562 | 149.02344 | 179.03419 | 180.04226 | 148.01615 | -32.02611 | Phenolic acids |

| 5 | Citric acid[5] | [M-H]-1 | C6H8O7 | 3.046 | 191.01913 | 191.01883 | 192.027 | 192.02641 | -0.00059 | Tricarboxylic acids |

| 6 | 2-phenoxypropanoic acid | [M+FA-H]-1 | C9H10O3 | 9.34 | 165.05478 | 165.05458 | 166.06299 | 120.05657 | -46.00642 | Carboxylic acids |

| 7 | Nor-9-carboxy-δ9-THC[6] | [M+H-H2O]+1 | C21H28O4 | 14.998 | 345.20596 | 345.20358 | 344.19876 | 362.20915 | 18.01039 | Cannabinoids |

| 8 | (2E)-4-hydroxy-3,7-dimethyl-2,6-octadien-1-ylbeta-D-glucopyranoside | [M-H]-1 | C16H28O7 | 19.81 | 377.18655 | 377.18167 | 332.1835 | 378.19383 | 46.01033 | Glycoside |

| 9 | 1-[2-(1,3-Benzodioxol-5-yl)-3-methyl-1-benzofuran-5-yl]-1,2-propanediol | [M+H-H2O]+1 | C19H18O5 | 16.836 | 309.11191 | 309.11212 | 368.10962 | 368.1121 | 0.00248 | Alcohols |

| 10 | Ethyl palmitoleate | [M+H]+1 | C18H34O2 | 20.671 | 283.26306 | 283.2634 | 282.25588 | 282.25578 | -0.0001 | Aliphatic |

| 11 | Gibberellin A7[7] | [M-H]-1 | C19H22O5 | 15.936 | 329.13959 | 329.13947 | 330.14672 | 330.14686 | 0.00014 | Diterpenoids |

| 12 | (2R)-2-[(2R,5S)-5-[(2S)-2-hydroxybutyl] oxolan-2-yl] propanoic acid | [M+H]+1 | C11H20O4 | 13.463 | 217.14366 | 217.14362 | 216.13616 | 216.13638 | 0.00023 | Carboxylic acids |

| 13 | Avocadyne 1-acetate[8] | [M+H]+1 | C19H34O4 | 19.822 | 309.24216 | 277.21643 | 326.24571 | 308.23502 | -18.01068 | Aliphatic |

| 14 | 4-{[(3S)-3-{5-[4-(dimethyl amino) phenyl]-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl}-1-pyrrolidinyl] methyl} benzoic acid | [M-H]-1 | C22H24N4O3 | 17.359 | 391.17963 | 391.17639 | 392.18484 | 392.1869 | 0.00206 | Heteroaromatic |

| 15 | 6-acetylmorphine[9] | [M+H]+1 | C19H21NO4 | 8.764 | 328.15442 | 328.15405 | 327.14706 | 327.14714 | 0.00008 | Morphinans |

| 16 | Methyl 3-(methylamino)-2-[(4-methyl-1,2,3-thiadiazol-5-yl)carbonyl] but-2-enoate | [M-H]-1 | C10H13N3O3S | 17.614 | 357.10123 | 357.10373 | 255.06776 | 358.1085 | 103.04074 | Esters |

| 17 | 4-(dimethylamino)-N-{[(2R,4S,5S)-5-(1-piperidinylmethyl)-1-azabicyclo[2.2.2] oct-2-yl]methyl} benzamide | [M+Na]+1 | C23H36N4O | 22.502 | 367.28183 | 367.28198 | 384.28891 | 344.29257 | -39.99635 | Amides |

| 18 | 2-hydroxymyristic acid | [M-H]-1 | C14H28O3 | 19.672 | 243.1964 | 243.19646 | 244.20384 | 244.20367 | -0.00017 | Long-chain fatty |

| 19 | 4-(1-adamantyl)-2-methyl-1,3-thiazole | [M+H]+1 | C14H19NS | 8.375 | 234.13382 | 234.1333 | 233.12382 | 233.12635 | 0.00253 | Thiazoles |

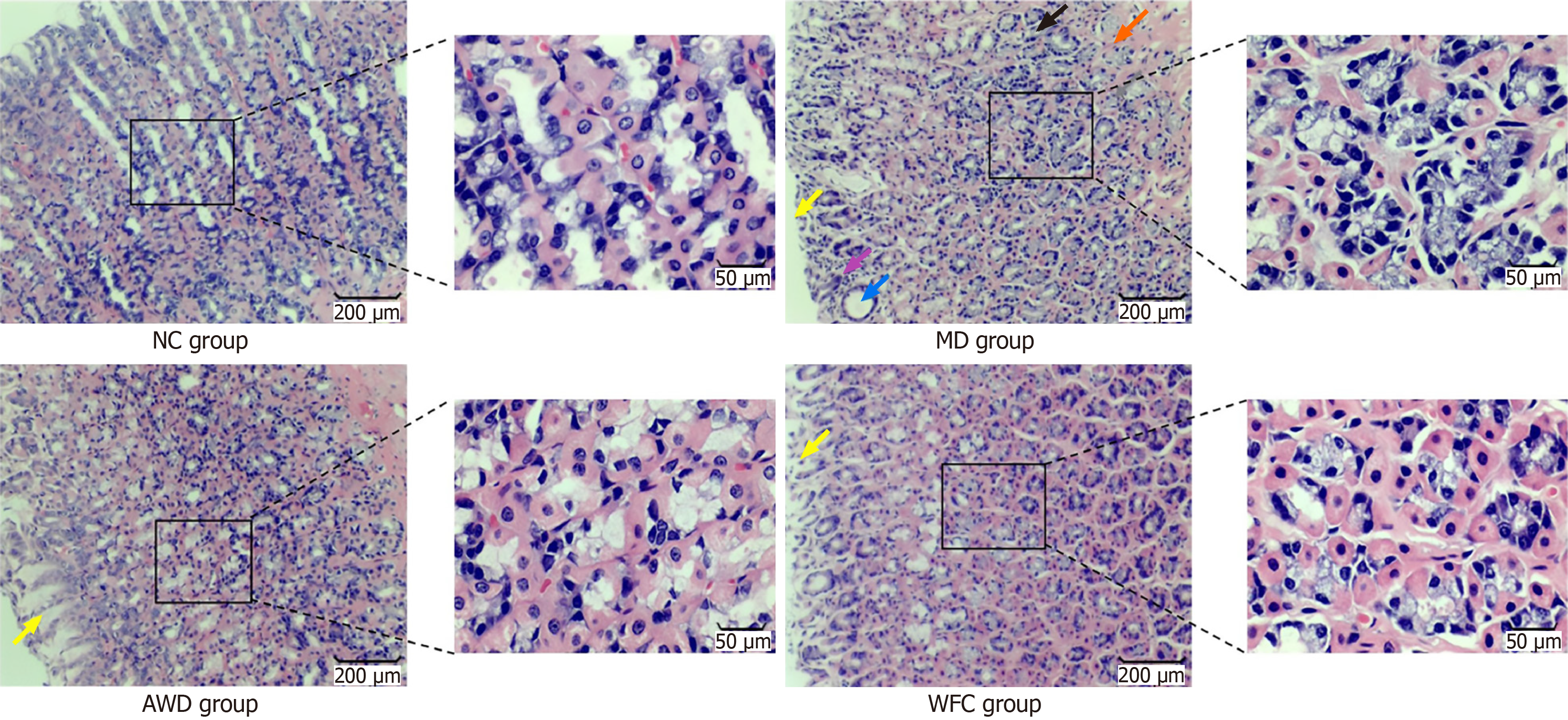

Significant differences in gastric mucosal pathology were observed among the groups through HE staining (Figure 3). Gastric mucosal histopathology was scored according to the updated Sydney system; results are presented in Figure 3 and Table 2. The MD group exhibited pronounced inflammatory cell infiltration, neutrophil infiltration, and glandular atrophy or reduction in the lamina propria. In contrast, pathological changes in gastric mucosa from the AWD and WFC groups were significantly alleviated (P < 0.01), with the AWD group demonstrating greater improvement.

The experimental results showed that, compared to the NC group, MD rats exhibited significantly increased inflammatory cytokine levels (P < 0.01). Following administration of AWD and WFC, the elevated cytokine levels in MD rats decreased significantly compared to untreated MD rats (P < 0.01). Notably, the AWD group demonstrated a more pronounced effect (Table 3).

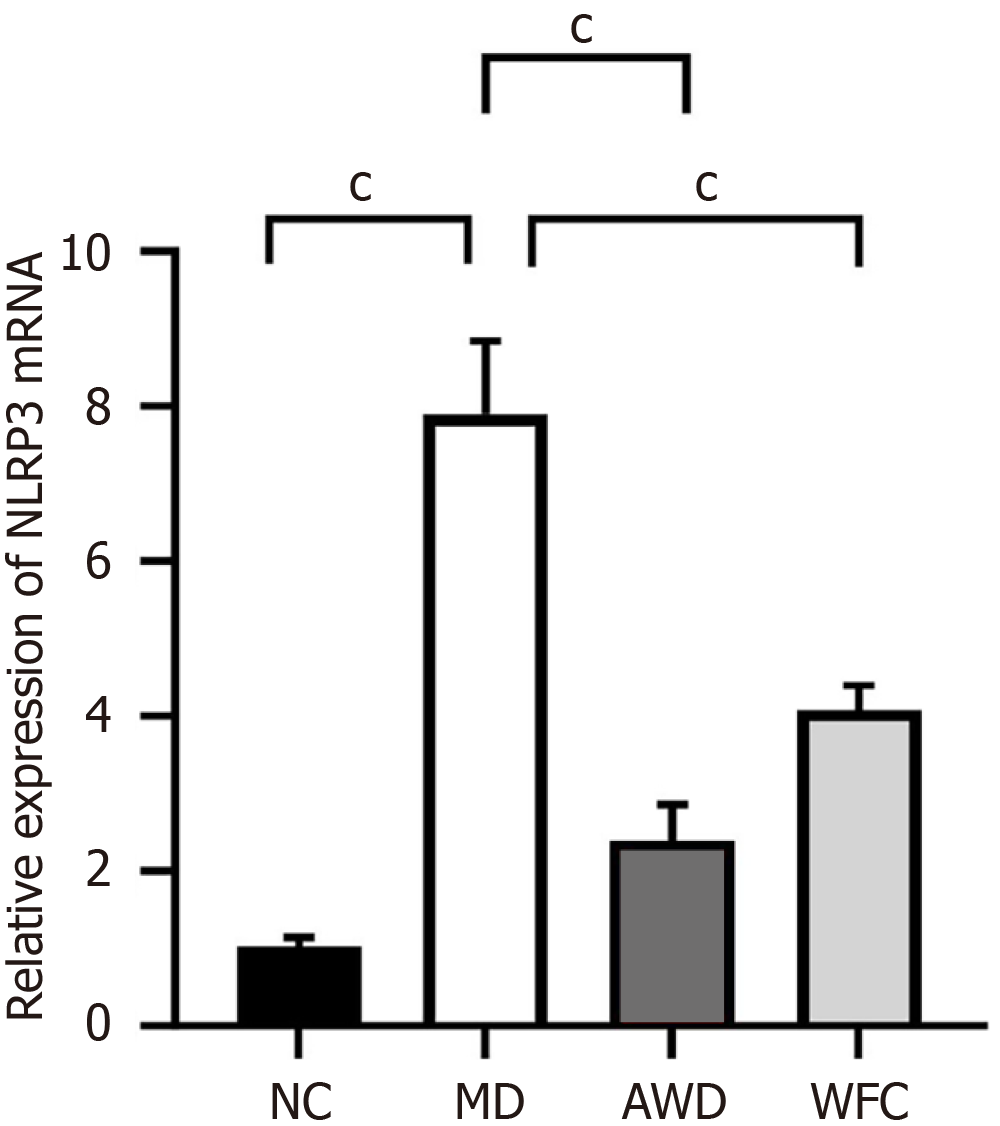

QRT-PCR analysis indicated significantly higher NLRP3 mRNA expression in the gastric mucosa of MD rats (7.89 ± 0.95) compared to the NC group (1.02 ± 0.12, P < 0.01, Figure 4). In contrast, NLRP3 mRNA expression was significantly reduced after AWD and WFC treatment (P < 0.01), with the AWD group showing a more pronounced effect. These results demonstrate that AWD markedly suppresses the gene expression of the NLRP3 inflammasome.

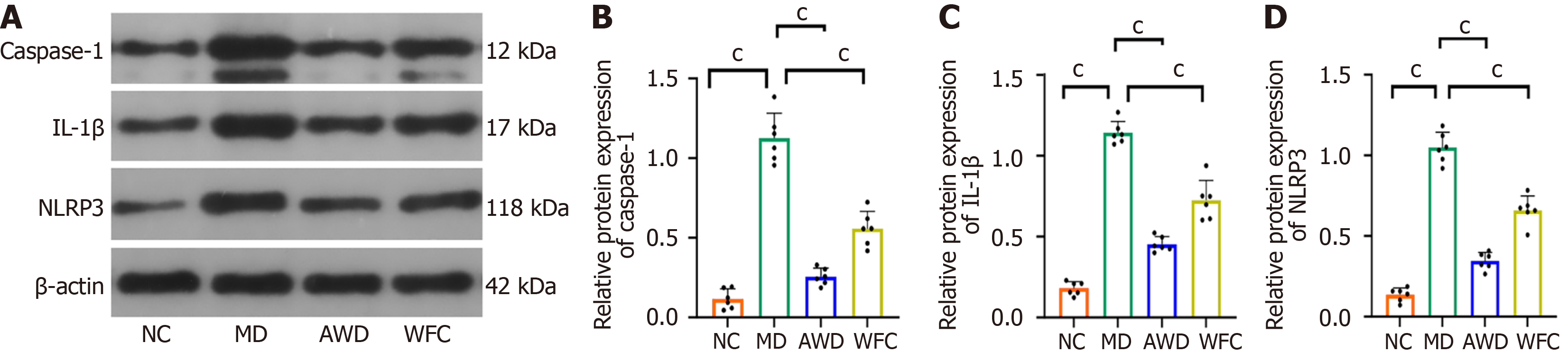

WB analysis was employed to measure protein expression of IL-1β, NLRP3, and caspase-1, revealing notably increased protein abundance in the MD group relative to NC animals (P < 0.01, Figure 5). Subsequent AWD and WFC treatments substantially reduced the expression of these proteins compared with untreated MD rats (P < 0.01). Notably, the AWD group showed a more pronounced effect.

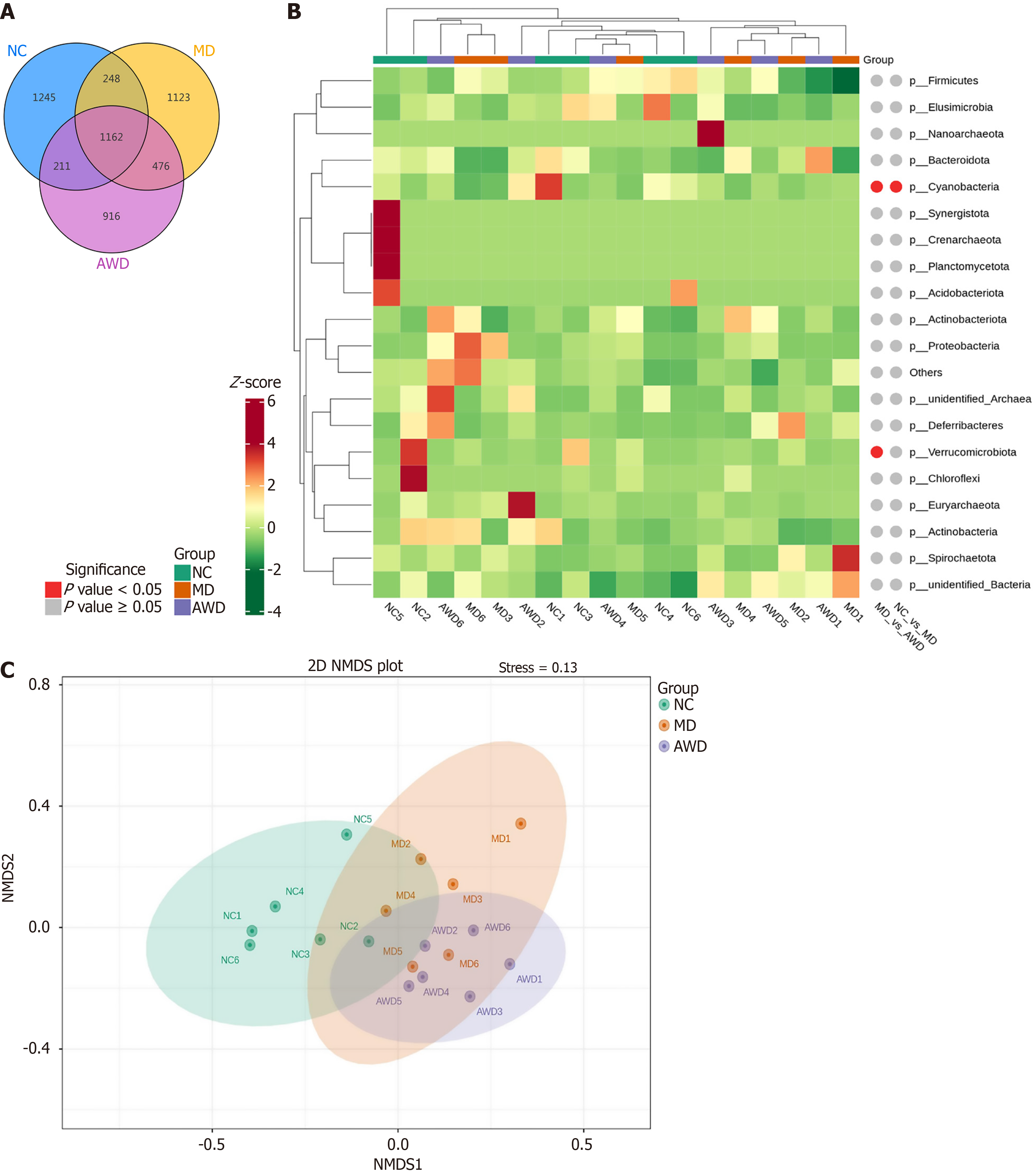

Intestinal content samples collected from 18 rats across the NC, MD, and AWD groups were analyzed by sequencing the 16S rRNA gene amplicon. After noise reduction, amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) were identified, resulting in 1162 unique ASVs across the three groups. Specifically, the ASV numbers detected were 1245 in the NC group, 1123 in the MD group, and 916 in the AWD group. The Venn diagram (Figure 6A) clearly illustrated notable differences in microbial composition among the three groups.

Species exhibiting significant differences among the groups were further analyzed. Using species abundance data at different taxonomic levels, the Metastats method was employed for hypothesis testing, and the resulting P values were adjusted to obtain Q values. Species significantly differing in abundance were identified based on P values and Q values, and integrated into a quantitative heatmap along with Metastats markers (Figure 6B). The results revealed considerable variation in the relative abundance and distribution patterns of microbial species among the three groups, suggesting that the structure and function of the microbial communities were altered.

Non-metric multidimensional scaling analysis (Figure 6C), yielded a stress value of less than 0.2, confirming that the analysis reliably depicted differences among samples.

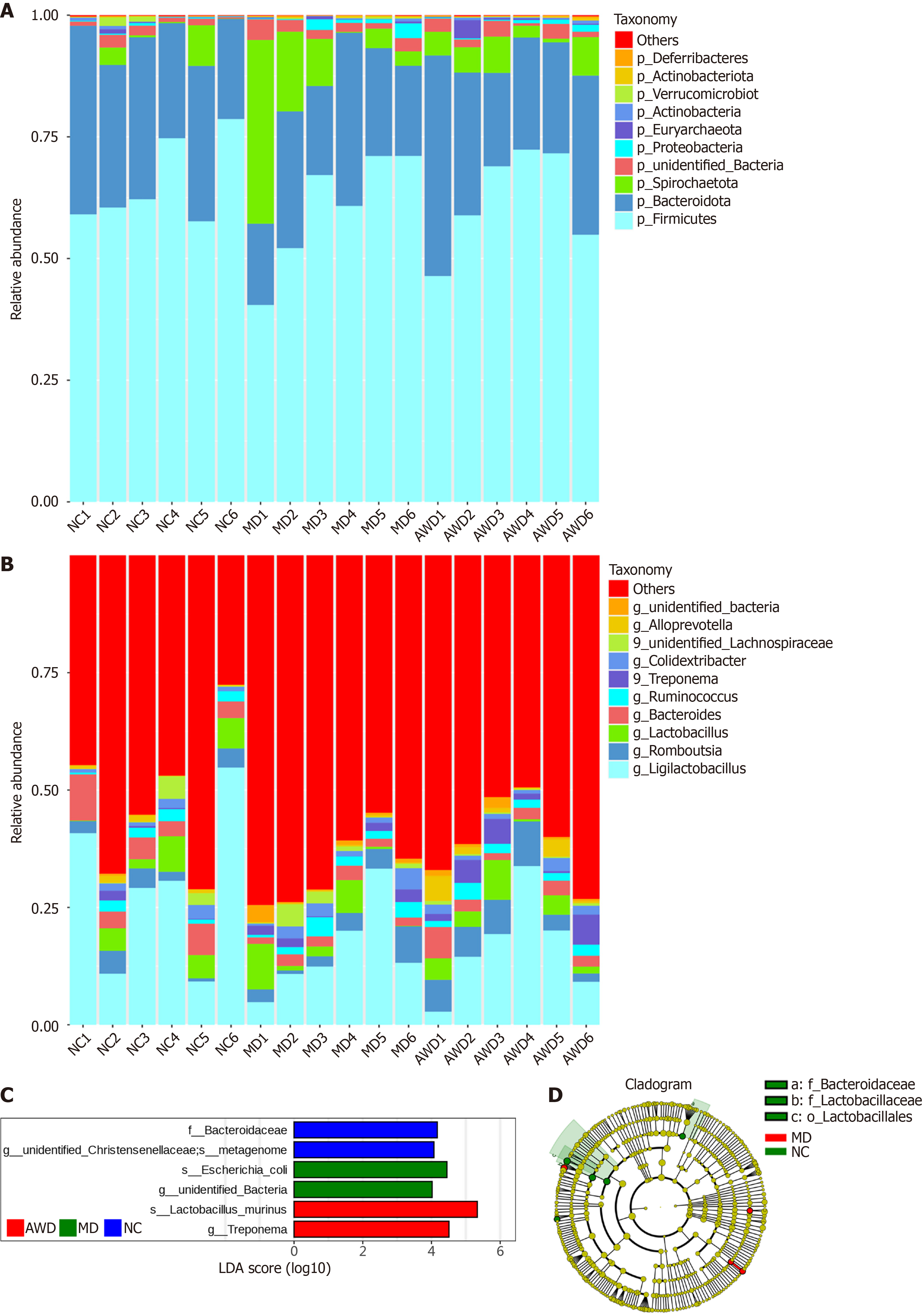

Composition of GM: Following sequencing data processing of intestinal contents from rats in the NC, MD, and AWD groups, species annotation based on ASV analysis was completed. The top 10 microbial taxa at the phylum and genus levels were selected according to relative abundance, and histograms depicting species abundance were constructed to visualize major bacterial community changes and the influence of AWD on microbiota composition.

The GM composition at the phylum level is illustrated in Figure 7A. Six dominant bacterial phyla were observed, including Spirochaetota, Bacteroidota, Firmicutes, Proteobacteria, Euryarchaeota, and Actinobacteria. The MD rats exhibited significantly increased levels of Spirochaetota relative to those in the NC group (P < 0.05). Conversely, AWD administration resulted in a notable decrease in the relative abundance of this phylum compared with untreated MD rats (P < 0.05).

Figure 7B illustrates the bacterial composition at the genus level, predominantly consisting of Ligilactobacillus, Rom

Differential microbial species among groups: The linear discriminant analysis effect size (LEfSe) method was sub

Results indicated that at the family level, the abundance of Bacteroidaceae and unidentified Christensenellaceae was significantly higher in the NC group than in other groups (P < 0.05). In the MD group, the abundance of Escherichia coli (species and genus level unidentified bacteria) significantly increased compared with other groups (P < 0.05). In the AWD group, the abundance of Lactobacillus murinus (species level) and Treponema (genus level) was significantly higher compared to other groups (P < 0.05).

These results suggest notable differences in microbial abundance among treatment groups at specific taxonomic levels, indicating potential biomarkers for differentiating microbial community structures among groups.

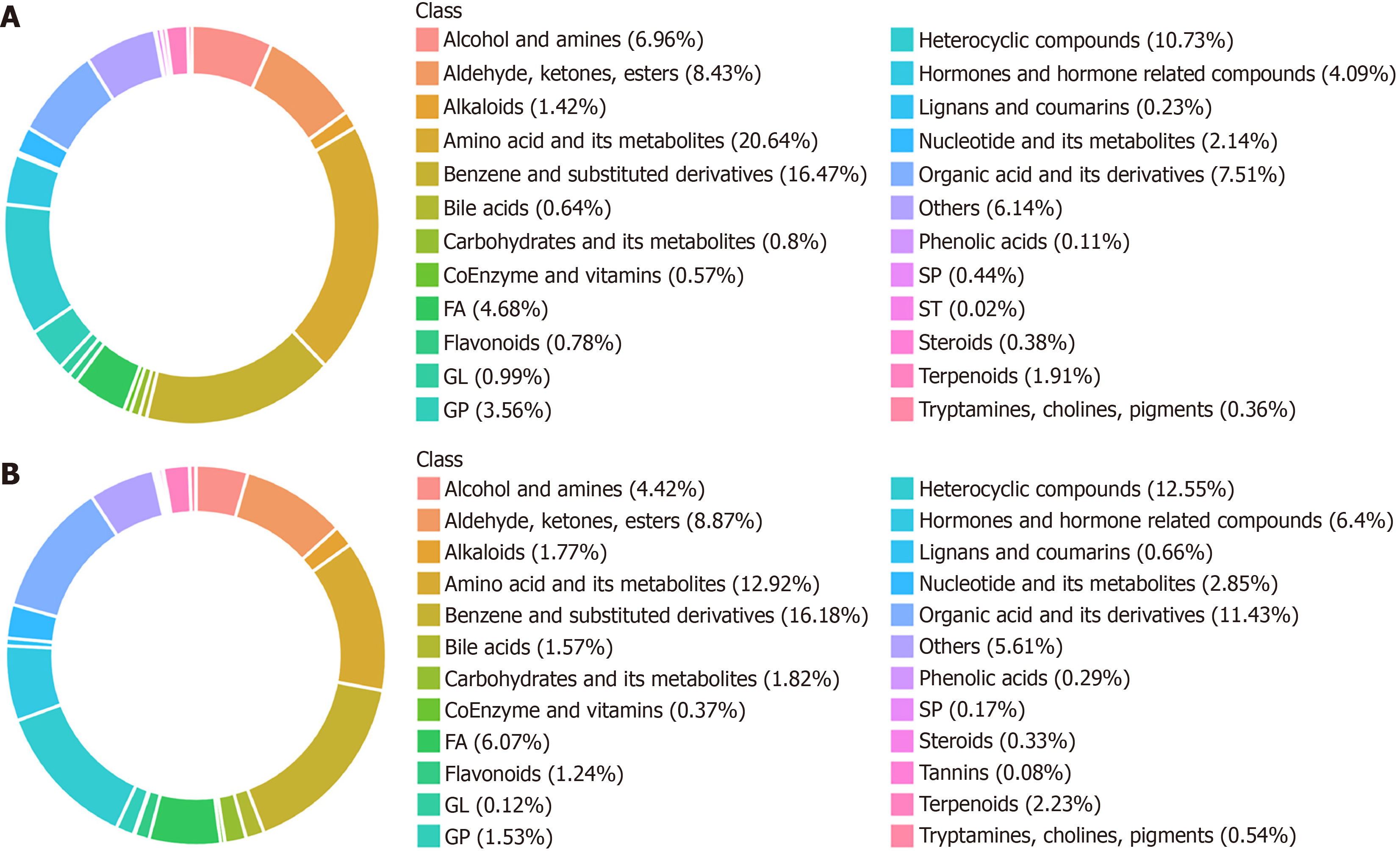

To clearly elucidate metabolic changes among the NC, MD, and AWD groups, primary and secondary metabolites in samples were comprehensively identified using ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry combined with broadly targeted metabolomics. A total of 6429 metabolites were detected, comprising 4385 positive-ion metabolites and 2044 negative-ion metabolites.

Among positive-ion metabolites, the top ten metabolite categories were amino acids and derivatives (20.64%), benzene and substituted derivatives (16.47%), heterocyclic compounds (10.73%), aldehydes, ketones, and esters (8.43%), fatty acids (4.68%), hormones and related compounds (4.09%), organic acids and derivatives (7.51%), glycerophospholipids (3.56%), nucleotides and derivatives (2.15%), and terpenoids (1.91%) (Figure 8A).

Among negative-ion metabolites, the top ten categories were benzene and substituted derivatives (16.18%), amino acids and derivatives (12.92%), heterocyclic compounds (12.55%), organic acids and derivatives (11.44%), aldehydes, ketones, and esters (8.87%), hormones and related compounds (6.4%), fatty acids (6.07%), alcohols and amines (4.42%), nucleotides and derivatives (2.85%), and carbohydrates and derivatives (1.82%) (Figure 8B).

Differential metabolite analysis showed significant changes in 132 metabolites between the MD and NC groups, with 34 upregulated and 98 downregulated (Figure 9A). Between the AWD and MD groups, 542 metabolites differed significantly, including 410 upregulated and 132 downregulated metabolites (Figure 9B). These results indicated distinct metabolic profiles across groups, highlighting unique metabolic signatures within each group.

To elucidate biological functions and pathways associated with significantly different metabolites (MD vs NC groups and AWD vs MD groups), differential metabolites were annotated and enriched using the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) database.

The differential metabolites identified between the MD and NC groups were annotated into various KEGG pathways, including 30 pathways under metabolism, 5 related to organismal systems, 6 under human diseases, 3 classified within environmental information processing, and 3 under cellular processes. Among these, 22 differential metabolites were annotated in the metabolism pathways, accounting for 91.67% of total annotated metabolites (Figure 10A). These meta

Differential metabolites distinguishing the AWD group from the MD group were annotated into 44 metabolism pathways, 14 organismal systems pathways, 11 human diseases pathways, 3 environmental information processing pathways, and 6 cellular processes pathways. Notably, 66 differential metabolites (82.5% of the total annotated meta

To systematically clarify possible interactions between host metabolites and GM, correlation analyses of the top 20 significantly differential metabolites and microorganisms were conducted. Heatmap analysis revealed the association patterns between key metabolites and GM.

As shown in Figure 11A, calcium carbonate in the NC and MD groups positively correlated with Bacteroides, All

As illustrated in Figure 11B, Alloprevotella in the AWD group (compared to MD group) positively correlated with cucurbitacin D, dTDP-galactose, histidine (His)-serine (Ser)-leucine (Leu)-Ser-glutamate (Glu), 17,23-epoxy-29-hydroxy-27-norlanost-8-ene-3,15,24-trione, tomenin, thyroxine sulfate, and 5alpha-ergosta-7,22-diene-3beta,5-diol (P < 0.05). Conversely, Alloprevotella negatively correlated with halcinonide, PE-NMe2 [18:0/18:1(9Z)], isoleucine-aspartate-Leu-arginine, and (+)-penbutolol (P < 0.05). Anaerovorax positively correlated with 8-iso-16-cyclohexyl-tetranor-pro

These positive and negative correlations indicate that certain microorganisms may promote or inhibit specific metabolite formation or accumulation. They also illustrate the complexity of the gut microbial community, potentially linked to microbial interactions, host physiological states, and environmental factors.

This study is the first to elucidate how AWD improves CAG by inhibiting the NLRP3 inflammasome and regulating GM. Experimental results confirmed that AWD reduces gastric mucosal inflammation by modulating the NLRP3/caspase-1/IL-1β signaling pathway. Additionally, AWD regulated GM composition and metabolic function, restored intestinal microecological balance, and effectively treated CAG. This finding offers a novel strategy for treating CAG via the “gut-stomach axis” and serves as a paradigm for investigating multi-target mechanisms of TCM formulations, holding significant clinical translational potential.

In this study, high-resolution mass spectrometry was innovatively employed to systematically analyze AWD and drug-containing serum. Prototype components, such as isoliquiritigenin, caffeic acid, citric acid, and (2E)-4-hydroxy-3,7-dimethyl-2,6-octadien-1-yl-β-D-glucopyranoside, along with their metabolic transformations, were identified in vivo. Metabolites, including calcium carbonate, dTDP-galactose, cucurbitacin D, His-Ser-Leu-Ser-Glu, 17,23-epoxy-29-hydroxy-27-norlanost-8-ene-3,15,24-trione, tomenin, thyroxine sulfate, and 5alpha-ergosta-7,22-diene-3beta,5-diol, may exert anti-inflammatory effects through the “microbiota-metabolite-immunity” axis. This provides a biochemical basis for elucidating AWD’s multi-target mechanisms.

From a TCM perspective, the compatibility of isoliquiritigenin, caffeic acid, and citric acid in AWD embodies the principles of “simultaneous treatment of spleen and stomach” and “harmonization of liver and stomach”[31,32].

Simultaneous treatment of spleen and stomach: Isoliquiritigenin repairs gastric mucosa by strengthening the spleen and invigorating qi, thus enhancing digestive function. Caffeic acid clears heat and dampness, and citric acid facilitates digestion by promoting fluid circulation. Their combined action strengthens the spleen-stomach axis and restores the physiological function of “spleen rising and stomach descending”.

Harmonization of liver and stomach: Isoliquiritigenin harmonizes liver and spleen, inhibiting mucosal damage caused by liver stagnation. Caffeic acid soothes the liver and promotes blood circulation, blocking pathological interactions between liver qi and stomach dysfunction. Citric acid regulates digestive juice secretion, relieving liver-stomach disharmony. Their synergistic effect aligns with the TCM principle “treating the stomach without neglecting the liver”. This compatibility reflects classical teachings such as “understanding spleen function first when encountering liver disorders”, as stated in “treatise on typhoid fever”, and “internal damage to the spleen-stomach leading to various diseases”, from Li DY’s “treatise on the spleen and stomach”.

From a modern medical viewpoint, isoliquiritigenin, caffeic acid, and citric acid exert anti-inflammatory effects through multiple mechanisms, influencing GM and inflammatory responses. Isoliquiritigenin increases probiotics (Akkermansia), enhances short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) production, and activates G protein-coupled receptors, reducing inflammation and lipid accumulation[33]. Isoliquiritigenin also inhibits NLRP3 inflammasome activation by streng

Caffeic acid suppresses inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6) and enzymes (cyclooxygenase-2) by inhibiting the NF-κB signaling pathway[36]. Its antioxidant activity prevents lipid peroxidation and inflammation from oxidative stress. Indirectly, caffeic acid inhibits NLRP3 inflammasome activation by downregulating NF-κB signaling[37]. In vivo, caffeic acid converts into ferulic acid or other bioactive metabolites via methylation or oxidation[38].

Citric acid reduces NLRP3 inflammasome activation by regulating intracellular metabolism, reducing energy supply to inflammatory cells[39]. It primarily metabolizes through the tricarboxylic acid cycle, yielding carbon dioxide and water while providing energy[40]. In the gut, citric acid promotes Bifidobacterium growth, enhancing SCFA production. Thus, citric acid indirectly influences GM and metabolites, supporting intestinal health[41].

In recent years, considerable attention has been focused on elucidating how the NLRP3 inflammasome becomes activated in numerous chronic inflammatory conditions. The activation of this inflammasome can trigger inflammatory cascades, subsequently damaging epithelial cells of the gastric mucosa, disrupting cellular homeostasis, and ultimately contributing to CAG[42,43]. In this study, multiple inflammatory cytokines and NLRP3 inflammasome-related proteins were quantified using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and WB techniques. Results indicated that AWD significantly inhibited these inflammatory markers. This finding is consistent with previous studies on NLRP3 inflammasome activation in various chronic inflammatory diseases[43-45]. These results further support targeting NLRP3 inflammasome activation as a potential therapeutic strategy for CAG.

Additionally, to explore interactions between GM and host health, this study employed both 16S rDNA amplicon sequencing and non-targeted metabolomic profiling. The regulatory effects of AWD on intestinal microbiota composition and metabolic activity in rats with CAG were comprehensively evaluated from diverse analytical dimensions. Our findings that AWD modulates the GM and associated metabolites suggest a potential crosstalk along the gut-stomach axis. The human microbiota is a complex ecosystem whose role in biomedical sciences and disease therapy is increasingly recognized[46]. However, further studies are needed to fully elucidate the specific microbial alterations induced by AWD. It could induce GM remodeling by increasing beneficial bacteria (Bacteroides, Firmicutes, Ligilactobacillus, and Lactobacillus) and decreasing harmful bacteria (Spirochaetota and Proteobacteria). Moreover, metabolomic analysis indicated significant enrichment of differential metabolites between the AWD and MD groups in metabolic pathways closely associated with various physiological and pathological processes. For example, the Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus infection pathway is implicated in multiple human cancers[47]. Autophagy-related pathways are essential for maintaining cellular homeostasis, stress responses, and disease progression[48]. Enrichment of the glycerophospholipid metabolism pathway may relate to cell membrane metabolism and signaling[49], while the endocrine resistance pathway is involved in mechanisms underlying resistance to endocrine therapies[50]. Changes in metabolites between groups are closely associated with disease onset, progression, and therapeutic responses. These findings suggest AWD may alleviate inflammation by modulating multiple metabolic pathways.

Compared with omeprazole, a PPI commonly prescribed in Western medicine for gastritis, AWD has demonstrated unique advantages in treating CAG, particularly in inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome activation and regulating GM. Omeprazole alleviates symptoms such as gastric pain and acid reflux by suppressing gastric acid secretion but has limited effects on gastric mucosal repair and inflammation. AWD can not only relieve symptoms but also promote mucosal repair and reduce inflammation through multi-target regulatory mechanisms. Some patients treated with omeprazole remain symptomatic and experience high recurrence rates[51]. Due to its multi-target regulation, AWD fundamentally improves pathological states and reduces recurrence risk. Long-term omeprazole use may lead to drug resistance and gastric wall thickening[52], while AWD follows the holistic principles of TCM and does not induce resistance. These characteristics suggest broad therapeutic potential for AWD in treating CAG.

While this study successfully delineates a novel GM metabolite NLRP3 axis through which AWD alleviates CAG, it has several limitations. First, the study was conducted in animal models, whose physiological and pathological mechanisms differ from those in humans; thus, clinical trials are essential to validate these findings. Second, although we described a novel GM metabolite NLRP3 axis for AWD, the precise molecular targets within gastric mucosa and the specific contributions of individual AWD components remain incompletely understood. The mechanisms discussed for constituents like isoliquiritigenin primarily rely on previous pharmacological reports, and direct causal relationships within the AWD CAG context require further confirmation. Additionally, other unmeasured confounding factors may have influenced the animal experiments. However, this study rigorously standardized diet, housing conditions, and the genetic background of animals, supporting the conclusion that observed microbial changes primarily resulted from AWD intervention.

To address these gaps, future research should employ a multifaceted strategy. Initially, transcriptomic and proteomic analyses of gastric tissues should identify key differentially expressed genes and proteins. Subsequent validation using gene knockout models or specific inhibitor interventions would conclusively establish causal molecular pathways and direct targets, shifting analysis from correlation to causation. Furthermore, constructing a network pharmacology model integrating AWD’s bioactive components, predicted targets, and associated signaling pathways can provide a more comprehensive, system-level perspective of its mechanism of action. Finally, long-term studies evaluating the durability and safety of AWD treatment are crucial to fully understand its effects on gastric mucosal pathology, inflammatory factor regulation, and GM stability, thereby providing a robust foundation for clinical application. Future research should also utilize germ-free mice colonized with specific microbiota or perform fecal microbiota transplantation experiments to establish direct causal evidence while minimizing confounding factors.

AWD alleviates the pathological progression of CAG through multi-target synergistic mechanisms. On one hand, AWD directly suppresses gastric mucosal inflammation by inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome activation. On the other hand, AWD remodels intestinal microbiota-metabolite homeostasis, enhances intestinal barrier function, and regulates mucosal immune responses.

| 1. | Li H, Li J, Lai M. Efficacy analysis of folic acid in chronic atrophic gastritis with Helicobacter pylori infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Gastroenterol. 2025;25:69. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Jia J, Zhao H, Li F, Zheng Q, Wang G, Li D, Liu Y. Research on drug treatment and the novel signaling pathway of chronic atrophic gastritis. Biomed Pharmacother. 2024;176:116912. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Yin Y, Liang H, Wei N, Zheng Z. Prevalence of chronic atrophic gastritis worldwide from 2010 to 2020: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Palliat Med. 2022;11:3697-3703. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Liu Y, Huang T, Wang L, Wang Y, Liu Y, Bai J, Wen X, Li Y, Long K, Zhang H. Traditional Chinese Medicine in the treatment of chronic atrophic gastritis, precancerous lesions and gastric cancer. J Ethnopharmacol. 2025;337:118812. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Zhang Z, Zhang X. Chronic atrophic gastritis in different ages in South China: a 10-year retrospective analysis. BMC Gastroenterol. 2023;23:37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kuang W, Xu J, Xu F, Huang W, Majid M, Shi H, Yuan X, Ruan Y, Hu X. Current study of pathogenetic mechanisms and therapeutics of chronic atrophic gastritis: a comprehensive review. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2024;12:1513426. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Abrahami D, McDonald EG, Schnitzer ME, Barkun AN, Suissa S, Azoulay L. Proton pump inhibitors and risk of gastric cancer: population-based cohort study. Gut. 2022;71:16-24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 23.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ohori K, Yano T, Katano S, Nagaoka R, Numazawa R, Yamano K, Fujisawa Y, Kouzu H, Koyama M, Nagano N, Fujito T, Nishikawa R, Ohwada W, Furuhashi M. Independent Association Between Use of Proton Pump Inhibitors and Muscle Wasting in Patients with Heart Failure: A Single-Center, Ambispective, Observational Study. Drugs Aging. 2023;40:731-739. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Tshibangu-Kabamba E, Yamaoka Y. Helicobacter pylori infection and antibiotic resistance - from biology to clinical implications. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;18:613-629. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 335] [Article Influence: 67.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Tong QY, Pang MJ, Hu XH, Huang XZ, Sun JX, Wang XY, Burclaff J, Mills JC, Wang ZN, Miao ZF. Gastric intestinal metaplasia: progress and remaining challenges. J Gastroenterol. 2024;59:285-301. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Wang L, Lian YJ, Dong JS, Liu MK, Liu HL, Cao ZM, Wang QN, Lyu WL, Bai YN. Traditional Chinese medicine for chronic atrophic gastritis: Efficacy, mechanisms and targets. World J Gastroenterol. 2025;31:102053. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 12. | Huang M, Li S, He Y, Lin C, Sun Y, Li M, Zheng R, Xu R, Lin P, Ke X. Modulation of gastrointestinal bacterial in chronic atrophic gastritis model rats by Chinese and west medicine intervention. Microb Cell Fact. 2021;20:31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Liu J, Li M, Chen G, Yang J, Jiang Y, Li F, Hua H. Jianwei Xiaoyan granule ameliorates chronic atrophic gastritis by regulating HIF-1α-VEGF pathway. J Ethnopharmacol. 2024;334:118591. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Wu DK, Huang RC, Tang YM, Jiang X. A mechanistic study of Anwei decoction intervention in a rat model of gastric intestinal metaplasia through the endoplasmic reticulum stress - Autophagy pathway. Tissue Cell. 2024;87:102317. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Rutsch A, Kantsjö JB, Ronchi F. The Gut-Brain Axis: How Microbiota and Host Inflammasome Influence Brain Physiology and Pathology. Front Immunol. 2020;11:604179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 255] [Cited by in RCA: 559] [Article Influence: 93.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kronsteiner B, Bassaganya-Riera J, Philipson C, Viladomiu M, Carbo A, Abedi V, Hontecillas R. Systems-wide analyses of mucosal immune responses to Helicobacter pylori at the interface between pathogenicity and symbiosis. Gut Microbes. 2016;7:3-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Zmora N, Levy M, Pevsner-Fishcer M, Elinav E. Inflammasomes and intestinal inflammation. Mucosal Immunol. 2017;10:865-883. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Zhou W, Zhang H, Wang X, Kang J, Guo W, Zhou L, Liu H, Wang M, Jia R, Du X, Wang W, Zhang B, Li S. Network pharmacology to unveil the mechanism of Moluodan in the treatment of chronic atrophic gastritis. Phytomedicine. 2022;95:153837. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 136] [Article Influence: 34.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Li J, Chen X, Mao C, Xiong M, Ma Z, Zhu J, Li X, Chen W, Ma H, Ye X. Epiberberine ameliorates MNNG-induced chronic atrophic gastritis by acting on the EGFR-IL33 axis. Int Immunopharmacol. 2025;145:113718. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Liu J, Chen Y, Zhang J, Zheng Y, An Y, Xia C, Chen Y, Huang S, Hou S, Deng D. Vitexin alleviates MNNG-induced chronic atrophic gastritis via inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome. J Ethnopharmacol. 2025;340:119272. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Chen CC, Liou JM, Lee YC, Hong TC, El-Omar EM, Wu MS. The interplay between Helicobacter pylori and gastrointestinal microbiota. Gut Microbes. 2021;13:1-22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 141] [Article Influence: 28.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 22. | Mommersteeg MC, Simovic I, Yu B, van Nieuwenburg SAV, Bruno IMJ, Doukas M, Kuipers EJ, Spaander MCW, Peppelenbosch MP, Castaño-Rodríguez N, Fuhler GM. Autophagy mediates ER stress and inflammation in Helicobacter pylori-related gastric cancer. Gut Microbes. 2022;14:2015238. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Chen B, Liu X, Yu P, Xie F, Kwan JSH, Chan WN, Fang C, Zhang J, Cheung AHK, Chow C, Leung GWM, Leung KT, Shi S, Zhang B, Wang S, Xu D, Fu K, Wong CC, Wu WKK, Chan MWY, Tang PMK, Tsang CM, Lo KW, Tse GMK, Yu J, To KF, Kang W. H. pylori-induced NF-κB-PIEZO1-YAP1-CTGF axis drives gastric cancer progression and cancer-associated fibroblast-mediated tumour microenvironment remodelling. Clin Transl Med. 2023;13:e1481. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 16.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Qu Q, Dou Q, Xiang Z, Yu B, Chen L, Fan Z, Zhao X, Yang S, Zeng P. Population-level gut microbiome and its associations with environmental factors and metabolic disorders in Southwest China. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes. 2025;11:24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Ogunjobi TT, Ohaeri PN, Akintola OT, Atanda DO, Orji FP, Adebayo JO, Abdul SO, Eji CA, Asebebe AB, Shodipe OO, Adedeji OO. Bioinformatics Applications in Chronic Diseases: A Comprehensive Review of Genomic, Transcriptomics, Proteomic, Metabolomics, and Machine Learning Approaches. Medinformatics. 2024;00: 1-17. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 26. | Nair AB, Jacob S. A simple practice guide for dose conversion between animals and human. J Basic Clin Pharm. 2016;7:27-31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2295] [Cited by in RCA: 4344] [Article Influence: 434.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Chen Z, Ding W, Yang X, Lu T, Liu Y. Isoliquiritigenin, a potential therapeutic agent for treatment of inflammation-associated diseases. J Ethnopharmacol. 2024;318:117059. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Kim YW, Zhao RJ, Park SJ, Lee JR, Cho IJ, Yang CH, Kim SG, Kim SC. Anti-inflammatory effects of liquiritigenin as a consequence of the inhibition of NF-kappaB-dependent iNOS and proinflammatory cytokines production. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;154:165-173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 185] [Cited by in RCA: 197] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Wan F, Zhong R, Wang M, Zhou Y, Chen Y, Yi B, Hou F, Liu L, Zhao Y, Chen L, Zhang H. Caffeic Acid Supplement Alleviates Colonic Inflammation and Oxidative Stress Potentially Through Improved Gut Microbiota Community in Mice. Front Microbiol. 2021;12:784211. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 21.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Cortez N, Villegas C, Burgos V, Cabrera-Pardo JR, Ortiz L, González-Chavarría I, Nchiozem-Ngnitedem VA, Paz C. Adjuvant Properties of Caffeic Acid in Cancer Treatment. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25:7631. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Liao YF, Luo FL, Tang SS, Huang JW, Yang Y, Wang S, Jiang TY, Man Q, Liu S, Wu YY. Network analysis and experimental pharmacology study explore the protective effects of Isoliquiritigenin on 5-fluorouracil-Induced intestinal mucositis. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:1014160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Wen X, Wan F, Wu Y, Liu Y, Zhong R, Chen L, Zhang H. Caffeic acid modulates intestinal microbiota, alleviates inflammatory response, and enhances barrier function in a piglet model challenged with lipopolysaccharide. J Anim Sci. 2024;102:skae233. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Ishibashi R, Furusawa Y, Honda H, Watanabe Y, Fujisaka S, Nishikawa M, Ikushiro S, Kurihara S, Tabuchi Y, Tobe K, Takatsu K, Nagai Y. Isoliquiritigenin Attenuates Adipose Tissue Inflammation and Metabolic Syndrome by Modifying Gut Bacteria Composition in Mice. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2022;66:e2101119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Usui-Kawanishi F, Kani K, Karasawa T, Honda H, Takayama N, Takahashi M, Takatsu K, Nagai Y. Isoliquiritigenin inhibits NLRP3 inflammasome activation with CAPS mutations by suppressing caspase-1 activation and mutated NLRP3 aggregation. Genes Cells. 2024;29:423-431. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Wang H, Jia X, Zhang M, Cheng C, Liang X, Wang X, Xie F, Wang J, Yu Y, He Y, Dong Q, Wang Y, Xu A. Isoliquiritigenin inhibits virus replication and virus-mediated inflammation via NRF2 signaling. Phytomedicine. 2023;114:154786. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Park JY, Yasir M, Lee HJ, Han ET, Han JH, Park WS, Kwon YS, Chun W. Caffeic acid methyl ester inhibits LPS‑induced inflammatory response through Nrf2 activation and NF‑κB inhibition in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Exp Ther Med. 2023;26:559. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Dai G, Jiang Z, Sun B, Liu C, Meng Q, Ding K, Jing W, Ju W. Caffeic Acid Phenethyl Ester Prevents Colitis-Associated Cancer by Inhibiting NLRP3 Inflammasome. Front Oncol. 2020;10:721. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Pavlíková N. Caffeic Acid and Diseases-Mechanisms of Action. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;24:588. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Etoh K, Araki H, Koga T, Hino Y, Kuribayashi K, Hino S, Nakao M. Citrate metabolism controls the senescent microenvironment via the remodeling of pro-inflammatory enhancers. Cell Rep. 2024;43:114496. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Mitome H, Takenishi M, Ono K, Kawagoe N, Imai T, Sasaki Y, Urita Y, Akira K. Preparation of [1'-(13) C]citric acid as a probe in a breath test to evaluate tricarboxylic acid cycle flux. J Labelled Comp Radiopharm. 2024;67:86-90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Hu P, Yuan M, Guo B, Lin J, Yan S, Huang H, Chen JL, Wang S, Ma Y. Citric Acid Promotes Immune Function by Modulating the Intestinal Barrier. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25:1239. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Wen J, Xuan B, Liu Y, Wang L, He L, Meng X, Zhou T, Wang Y. NLRP3 inflammasome-induced pyroptosis in digestive system tumors. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1074606. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Zou G, Tang Y, Yang J, Fu S, Li Y, Ren X, Zhou N, Zhao W, Gao J, Ruan Z, Jiang Z. Signal-induced NLRP3 phase separation initiates inflammasome activation. Cell Res. 2025;35:437-452. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Xu J, Zhang L, Duan Y, Sun F, Odeh N, He Y, Núñez G. NEK7 phosphorylation amplifies NLRP3 inflammasome activation downstream of potassium efflux and gasdermin D. Sci Immunol. 2025;10:eadl2993. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 20.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Cheng Z, Huang M, Li W, Hou L, Jin L, Fan Q, Zhang L, Li C, Zeng L, Yang C, Liang B, Li F, Chen C. HECTD3 inhibits NLRP3 inflammasome assembly and activation by blocking NLRP3-NEK7 interaction. Cell Death Dis. 2024;15:86. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Ogunjobi TT, Okafor AM, Ohuonu NI, Nebolisa NM, Abimbolu AK, Ajayi RO, Afuape AR, Ojajuni MG, Ogunbor OO, Elijah EU, Akinwande KG, Aigbagenode AA, Olaniran TS, Adewoyin AA, Kolapo EE, Musa A. Navigating the Complexity of the Human Microbiome: Implications for Biomedical Science and Disease Treatment. Medinformatics. 2024;. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 47. | Wu XJ, Zhang Z, Wong JP, Rivera-Soto R, White MC, Rai AA, Damania B. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus viral protein kinase augments cell survival. Cell Death Dis. 2023;14:688. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Wang Y, Ma Z, Peng W, Yu Q, Liang W, Cao L, Wang Z. 3,5,6,7,8,3',4'- Heptamethoxyflavonoid inhibits TGF-β1-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition by regulating oxidative stress and autophagy through MEK/ERK/PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway. Sci Rep. 2025;15:4567. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Zeng X, Yu T, Xia L, Ruan Z. Untargeted metabolomics analysis of glycerophospholipid metabolism in very low birth weight infants administered multiple oil lipid emulsions. BMC Pediatr. 2024;24:849. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Kan Z, Wen J, Bonato V, Webster J, Yang W, Ivanov V, Kim KH, Roh W, Liu C, Mu XJ, Lapira-Miller J, Oyer J, VanArsdale T, Rejto PA, Bienkowska J. Real-world clinical multi-omics analyses reveal bifurcation of ER-independent and ER-dependent drug resistance to CDK4/6 inhibitors. Nat Commun. 2025;16:932. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Zhuang Q, Chen S, Zhou X, Jia X, Zhang M, Tan N, Chen F, Zhang Z, Hu J, Xiao Y. Comparative Efficacy of P-CAB vs Proton Pump Inhibitors for Grade C/D Esophagitis: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2024;119:803-813. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Song H, Zhu J, Lu D. Long-term proton pump inhibitor (PPI) use and the development of gastric pre-malignant lesions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;2014:CD010623. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/