Published online Dec 28, 2025. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v31.i48.114049

Revised: October 12, 2025

Accepted: November 10, 2025

Published online: December 28, 2025

Processing time: 107 Days and 19.9 Hours

Chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection acquired in childhood frequently presents with mild or nonspecific symptoms, yet a distinct subset of pediatric patients develops rapid progression to liver cirrhosis (LC) before adulthood.

To identify clinical and pathological characteristics of pediatric HBV-related LC.

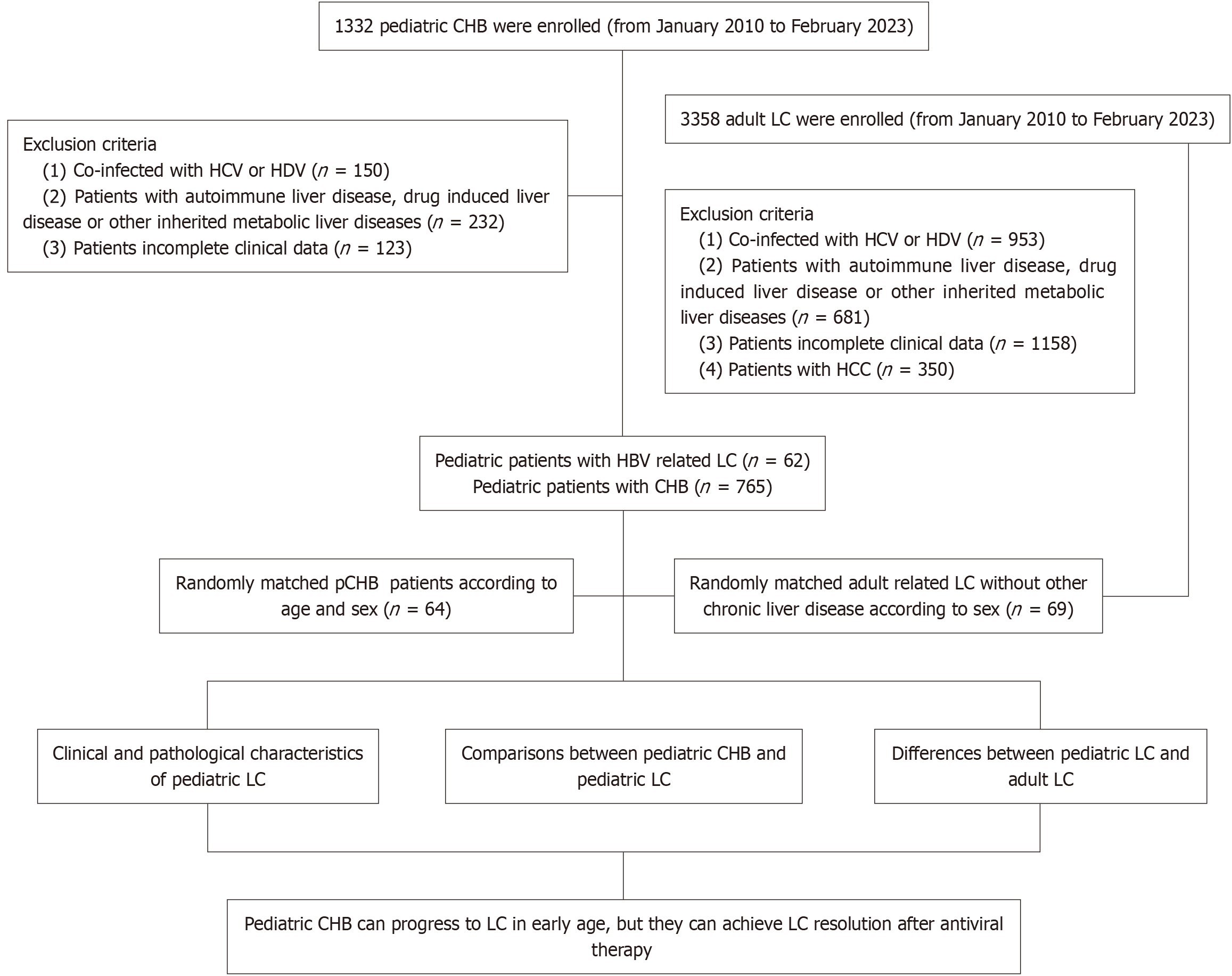

A total of 1332 pediatric patients with chronic HBV infection from the Fifth Medical Center of PLA General Hospital from January 2010 to January 2023 were included in this study. We identified 62 pediatric HBV-related LC by liver biopsy from the group. Subsequently, we described the clinical and pathological characteristics of pediatric LC. And 64 pediatric chronic hepatitis B (CHB; age and sex were matched with pediatric LC group) and 69 adult HBV-related LC (sex were matched with pediatric LC group) were enrolled to further demonstrate clinical and pathological differences between pediatric LC, pediatric CHB and adult LC.

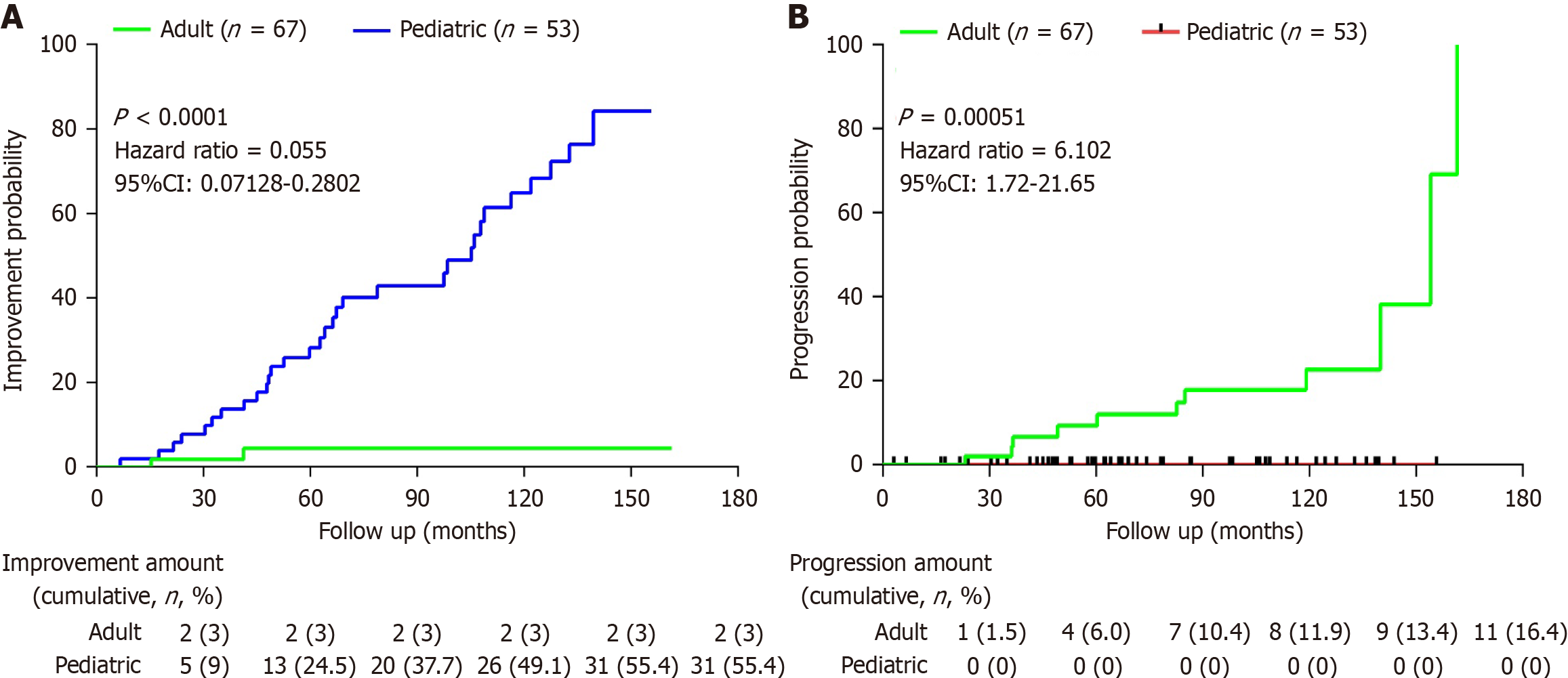

We enrolled 62 pediatric LC, including 54 (87.1%) males and 8 (12.9%) females. The median age was 11 (4-14) years old. The pediatric LC group showed significantly lower median quantitative HBV DNA loads (log10IU/mL: 6.3 vs 17.4, P < 0.001), reduced HBsAg titers (log10IU/mL: 3.11 vs 8.956, P < 0.0001), and diminished hepatitis B e antigen-positive positive rate (81.4% vs 93.8%, P < 0.05) compared with pediatric CHB. A higher proportion of pediatric patients were asymptomatic (77.4%) compared to adult patients (11.6%) as they first diagnosed as LC, pediatric LC showed milder initial symptoms compared with adult patients such as fatigue (4.8% vs 27.5%), abdominal discomfort (9.7% vs 23.2%), nausea (0% vs 10.1%), and poor appetite (6.5% vs 8.7%; all P < 0.0001). Notably, pediatric LC can achieve a significant percentage of functional cure compared with adult LC as 17.4% and 0%. The incidence of progression of LC in children after antiviral therapy continues to be much lower than that in adult LC (hazard ratio = 6.102, 95% confidence interval: 1.72-21.65, P = 0.00051). While the incidence of LC remission in children after antiviral therapy continues to be much higher than that in adult LC (hazard ratio = 0.055, 95% confidence interval: 0.07128-0.2802, P < 0.0001).

Pediatric patients with HBV-related cirrhosis exhibit elevated virological para

Core Tip: Pediatric cirrhosis is mostly detected via physical examination with rare symptoms, whereas adults typically present with jaundice, hematochezia, and fatigue. Pediatric cirrhosis has a better prognosis than adult cases, with higher hepatitis B surface antigen seroclearance rates and potential rapid reversal in some instances, while adult cirrhosis generally carries a poor prognosis. Pediatric cirrhosis progresses more rapidly (even occurring in children < 3 years old), whereas adult cases follow a slower clinical course. Children with cirrhosis often have a history of liver dysfunction and frequently experience disease recurrence due to self-discontinuation of hepatoprotective/antiviral/traditional Chinese medicine treatments.

- Citation: Zhao BK, Li Y, Jiang YY, Li ML, Jiang Y, Zhu L, Guo CN, Liu SH, Chen L, Jiang LN, Niu JQ, Zhao JM. Clinical, pathological characteristics and long-term outcomes of hepatitis B virus related cirrhosis in pediatric observational study. World J Gastroenterol 2025; 31(48): 114049

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v31/i48/114049.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v31.i48.114049

Liver cirrhosis (LC) is a leading cause of end-stage liver disease in children, with a more complex etiological spectrum than adults, involving multiple mechanisms such as genetic metabolic disorders, congenital developmental defects, infectious factors, and autoimmune conditions[1-3]. LC, typically develops over decades in adults[4], ho

Globally, LC cases among children and adolescents have risen concerningly, increasing from 724200 in 1990 to 917800 in 2017, with an annual growth rate of 0.13%[6]. Children with LC face significantly higher mortality risks, particularly in early childhood[7,8]. In the study by Hu et al[9], the incidence rates of mild to moderate fibrosis and cirrhosis in children with chronic hepatitis B (CHB) were 80.2% and 8.3%, respectively, indicating that HBV-related cirrhosis in the pediatric population still requires close attention[9].

The transmission routes of HBV include mother-to-child transmission, blood transmission, and sexual transmission, etc. With the implementation of large-scale vaccination programs, the incidence of HBV infection in children has been declining annually. However, China, as a high-endemic region for HBV, still exhibits a high proportion of children with CHB. Due to reasons such as failures in mother-to-child blockade and vaccination inefficacy, vertical transmission remains the primary route of CHB infection among children in China. Therefore mother-to-child transmission is still the primary route of HBV infection in pediatric cases[10-12]. Notably, some of these children rapidly develop advanced fibrosis (F4), exhibiting distinct clinical and pathological features compared to adults with HBV-related cirrhosis.

Despite these critical observations, research on early-onset LC in young children - particularly infants, toddlers, and preschoolers - remains scarce. Existing studies predominantly focus on adult populations, with only limited reports addressing pediatric HBV-associated cirrhosis. To bridge this gap, our study systematically compared cirrhotic and non-cirrhotic pediatric HBV patients, as well as contrast early-onset pediatric cases with adult-onset cirrhosis following vertical transmission. Additionally, potential risk factors for pediatric LC were identified. These findings may provide a theoretical foundation for early intervention strategies and improved prognostic prediction in high-risk pediatric popu

From January 2010 to February 2023, we enrolled 1332 patients aged ≤ 18 years with CHB infection from the Fifth Medical Center of PLA General Hospital. Among them, 150 patients coinfected with hepatitis C virus (HCV) or hepatitis D virus (HDV). The total number of patients being excluded by other etiologies was 232. The number of patients with auto

CHB were diagnosed as hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) positivity lasts more than 6 months accompanied by different degrees of liver inflammation, necrosis, and/or liver fibrosis[17]. The diagnostic criteria for children with LC are based on the 2019 Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of LC: In the compensated stage of LC, it includes (any one of the following 3 items): (1) Histological evidence of LC; (2) Endoscopy showing esophageal and gastric varices or ectopic varices in the digestive tract, excluding non-LC-related portal hypertension; and (3) Imaging examinations such as B-ultrasound, computed tomography (CT), or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) indicating the characteristics of LC or portal hypertension. The diagnostic criteria for decompensated LC include: On the basis of LC, complications of portal hypertension and/or liver function decline occur[18]. At admission, informed consent was obtained from each child's parents. The study was approved by the ethics committees of the Fifth Medical Center of PLA General Hospital.

The routine preoperative examination included liver and renal function tests, HCV and HDV detection, blood ammonia, serum alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) level, prothrombin time (PT), and blood routine test. HBV DNA quantification was detected with a lower limit of 20 IU/mL (Roche COBAS AmpliPrep, Roche Molecular Systems, Inc., NJ, United States) and HBsAg quantification (anti-HBsAg) was quantified with a lower limit of 0.05 IU/mL (Roche COBAS AmpliPrep, Roche Molecular Systems, Inc., NJ, United States). Abdominal ultrasonography was routinely performed. Other imaging examinations, including X-ray, CT, MRI and liver stiffness measurement, were carried out wherever necessary.

Liver biopsy specimens were obtained under strict aseptic precautions. All samples were processed through hematoxylin and eosin, Masson’s trichrome and reticulin staining. All slides were independently evaluated by three experienced pathologists without inter-observer consultation. All pathologists performed their evaluations independently initially. Subsequently, they participated in a consensus conference where any discrepant cases were discussed jointly under a multi-head microscope until a unanimous final diagnosis was achieved. Histological features were quantitatively assessed according to the Brunt criteria to determine inflammatory activity (distinct grade) and fibrosis stage. Grading ranges from grade 0 (no inflammation) to grade 3 (severe inflammation with ballooning degeneration and necrosis), while staging progresses from stage 0 (no fibrosis) to stage 4 (cirrhosis), characterized by nodular regeneration, bridging fibrosis, and disrupted liver architecture. Cirrhosis diagnosis required definitive evidence of nodular regeneration surrounded by diffuse fibrosis with loss of normal hepatic architecture, with findings validated through collagen proportionate area quantification in select cases[19,20].

Statistical analyses were performed and visualized using SPSS version 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States) and GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, United States). Continuous variables were subjected to normality testing (Shapiro-Wilk) and expressed appropriately: mean ± SD for parametric data (compared via two-tailed t-tests) or median (interquartile range) for non-parametric data (analyzed with Mann-Whitney U test). Categorical variables were reported as frequencies [n (%)] and compared using χ2/Fisher’s exact tests. Cox regression was used to analyze factors influencing the remission/progression of LC in both pediatric and adult patients. Survival analysis was conducted via Kaplan-Meier test, with between-group differences assessed by the log-rank test. All statistical tests were two-sided, and a P < 0.05 defined statistical significance.

Our study enrolled 62 pediatric patients with cirrhosis, including 54 (87.1%) males and 8 (12.9%) females. The median age was 11 (4-14) years. The median BMI was 16.77 (15.45-20.67) kg/m2. There were 4 cases (6.5%) with ascites, and no cases of hepatic encephalopathy or gastrointestinal bleeding were observed when they first diagnosed as LC. A total of 77.4% (n = 48) were asymptomatic, 9.7% (n = 6) had jaundice, 6.5% (n = 4) exhibited aberration, 4.8% (n = 3) presented fatigue, 3.2% (n = 2) showed discomfort in the liver area. Thoracoabdominal bleeding points, recurrent epistaxis, and progressive elevation of AFP were presented in one patient each, respectively. Liver function tests revealed significant abnormalities with median alanine aminotransferase as 107.5 (58.5-207.25) U/L, aspartate aminotransferase as 110.5 (64.25-169.5) U/L, and gamma-glutamyltransferase (GGT) as 70.5 (48-105) U/L. The median value of platelets (PLT), albumin (ALB) and PT levels were within the normal range as 16 (113.5-221) × 109/L, 39 (36-41.25) g/L and 12.3 (11.55-13.35) seconds, respectively. The median Child-Pugh score was 5 (5-6), and the median pediatric end-stage liver disease/model for end-stage liver disease score was 3.5 (0.75-8). Virologically, genotype C predominated (69.4%, n = 43) in all the 62 LC patients. The hepatitis B e antigen-positive (HbeAg) positive rate was 81.4% (n = 48). Median log10HBsAg was 3.11 (0-3.69) and median log10(HBV DNA load) was 6.3 (4.58-7.54) IU/mL. Notably, only 12.9% (n = 8) received antiviral therapy before being diagnosed as LC (Table 1).

| Variable | Total (N = 62) |

| Demographics | |

| Age (years) | 11 (4-14) |

| Male | 54 (87.1) |

| Female | 8 (12.9) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 16.76 (15.45-20.67) |

| Comorbidity | |

| Hepatic encephalopathy | 0 (0) |

| Ascites | 4 (6.5) |

| Gastrointestinal bleeding | 0 (0) |

| No comorbidity | 58 (93.5) |

| Presenting symptoms of cirrhosis | |

| Asymptomatic | 48 (77.4) |

| Fatigue | 3 (4.8) |

| Aberration | 4 (6.5) |

| Jaundice | 6 (9.7) |

| Discomfort in the liver area | 2 (3.2) |

| Bleeding points on the chest and abdomen | 1 (1.6) |

| Repeated epistaxis | 1 (1.6) |

| AFP progressively increases | 1 (1.6) |

| Antiviral therapy before LC | 8 (12.9) |

| Genotype | |

| Unknown | 14 (22.6) |

| B | 5 (8.1) |

| C | 43 (69.4) |

| Biochemistry | |

| ALT (U/L) | 107.5 (58.5-207.25) |

| AST (U/L) | 110.5 (64.25-169.5) |

| GGT (U/L) | 70.5 (48-105) |

| ALP (U/L) | 299 (232.25-373) |

| ALB (g/L) | 39 (36-41.25) |

| TBIL (μmol/L) | 11.05 (8.1-19.15) |

| DBIL (μmol/L) | 4.7 (3.08-8.48) |

| Glucose (mmol/L) | 4.5 (4.08-4.89) |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | 1.15 (0.97-1.4) |

| LDL-C (mmol/L) | 2.27 (2.02-2.85) |

| TG (mmol/L) | 0.94 (0.75-1.28) |

| Cr (μmol/L) | 48.68 ± 14.11 |

| HGB (g/L) | 127.84 ± 14.45 |

| PLT (109/L) | 165 (113.5-221) |

| WBC (109/L) | 6.19 (4.67-7.63) |

| 3.15 (2.12-4.26) | |

| Neutrophil (109/L) | 3.175 (2.15-4.27) |

| log10(qHBV DNA) | 6.3 (4.58-7.54) |

| log10(qHBsAg) | 3.11 (0-3.69) |

| HBeAg(+) | 48 (81.4) |

| Child-Pugh score | 5 (5-6) |

| PELD/MELD score | 3.5 (0.75-8) |

| AFP (ng/mL) | 51 (13.73-255) |

| T lymphocyte | 2060.62 ± 1121.46 |

| B lymphocyte | 599.5 (437-940) |

| NK | 183.5 (113-327.25) |

| CD8+ | 718 (502.25-1012) |

| CD4+ | 1003.5 (722.25-1422.85) |

| CD4/CD8 | 1.44 (1.11-1.81) |

| PT (seconds) | 12.3 (11.55-13.35) |

| INR | 1.06 (0.99-1.14) |

A total of 46 children received antiviral therapy after being diagnosed as LC, including 82.6% (n = 38) males and 17.4% (n = 8) females. Among them, 5 patients were treated with nucleos(t)ide analogues monotherapy, among whom 4 achieved HBV DNA seroclearance, with a median seroclearance time as 14.93 (4.99-54.47) months. And 41 patients were treated with interferon combined with nucleos(t)ide analogues. In the combined treatment group, the HBsAg sero

| Variable | Total (N = 46) |

| Demographics | |

| Age (years) | 8 (3.5-13) |

| Male | 38 (82.6) |

| Female | 8 (17.4) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 16.38 (15.3-18.15) |

| Antiviral regimen | |

| NA | 5 (10.8) |

| NA-HBV DNA loss | 4 (80) |

| NA-HBV DNA loss time (months) | 14.93 (4.99-54.47) |

| IFN + NA | 41 (89.2) |

| IFN + NA HBsAg loss | 8 (20) |

| IFN + NA HBeAg loss | 26 (65) |

| IFN + NA HBV DNA loss | 38 (95) |

| IFN + NA HBsAg loss time (months) | 35.17 ± 21.51 |

| IFN + NA HBeAg loss time (months) | 10.54 (3.52-37.87) |

| IFN + NA HBV DNA loss time (months) | 7.77 (5.22-14.41) |

| LC resolution at EOT | |

| HBsAg loss | 8 (17.4) |

| HBeAg loss | 26 (56.5) |

| HBV DNA loss | 42 (91.3) |

| HBsAg loss time (months) | 35.17 ± 21.51 |

| HBeAg loss time (months) | 42.14 (14.07-151.46) |

| HBV DNA loss time (months) | 7.77 (4.79-14.46) |

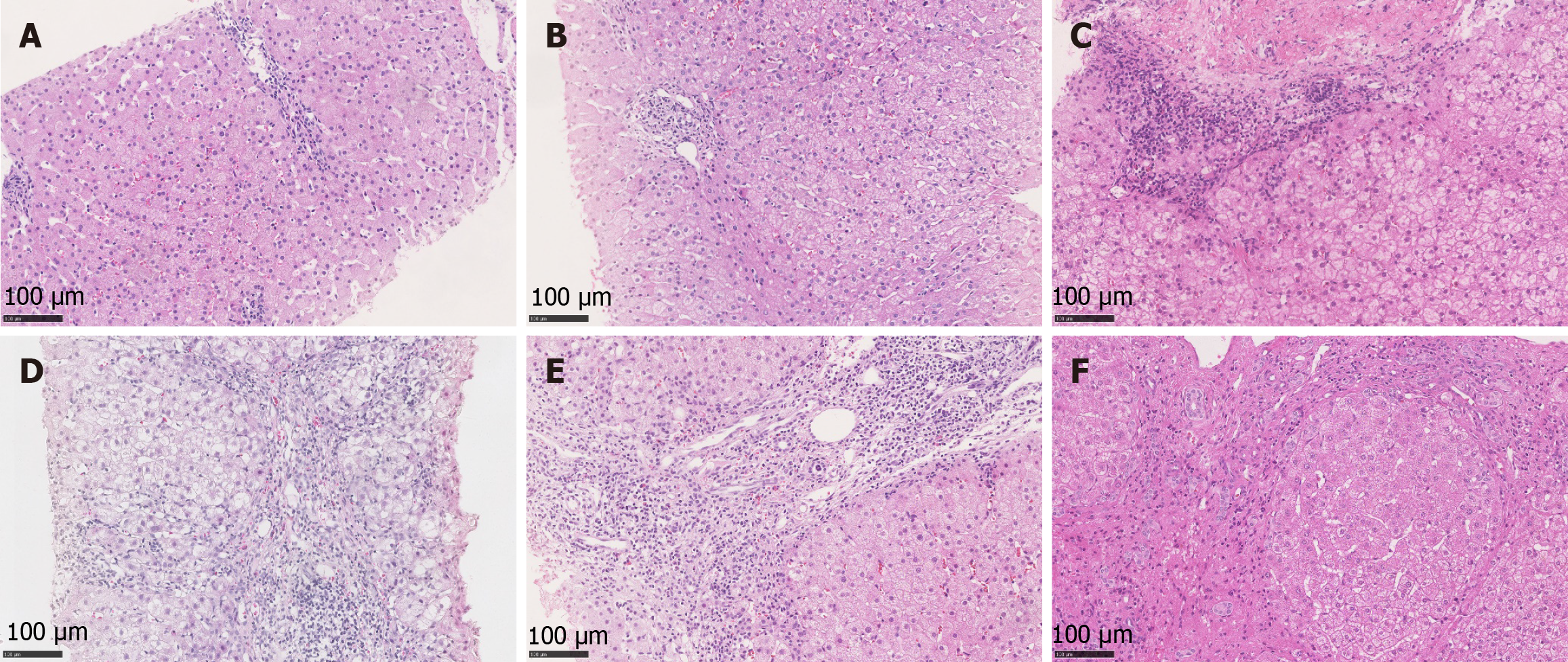

The pathological changes of CHB in children are generally similar to those in adults. However, during the inactive phase, hepatocytes with ground-glass appearance due to HBsAg overexpression are frequently observed in the hepatic lobules of pediatric patients, while inflammatory necrosis is typically absent or minimal. In the active phase, children with CHB usually demonstrate mixed inflammatory necrosis and ground-glass hepatocytes. Most pediatric patients exhibit rela

Specifically, due to their immature immune systems, children demonstrate prolonged immune tolerance and slower progression of hepatic fibrosis. Early stages are characterized predominantly by periportal fibrosis with rare bridging fibrosis, often resulting in micronodular cirrhosis. These patients typically show mild inflammatory activity with sparse lymphocyte infiltration. Although hepatocyte regenerative capacity is strong, cellular atypia is uncommon, leading to lower HCC risk.

In contrast, adult patients mount vigorous immune responses that drive rapidly progressive inflammatory necrosis. Bridging fibrosis and extensive pseudolobule formation are common, frequently progressing to macronodular or mixed cirrhosis. Adult cases exhibit marked inflammatory activity featuring prominent interface hepatitis, spotty necrosis, and dense inflammatory cell infiltration. The fibrous septa are broad and densely packed, with significant vascular re

As delineated in Table 3, a control group of 64 pediatric CHB patients was matched based on age and sex to the pediatric LC group. Cirrhosis patients exhibited substantially elevated GGT (70.5 U/L vs 23 U/L, P < 0.0001) alongside depressed ALB levels [39 (36-41.25) vs 40 (38-43); P < 0.001]. PLT counts were dramatically reduced in cirrhosis (P < 0.0001), correlating with relatively prolonged PT (P < 0.0001). Triglycerides were higher in cirrhosis (P < 0.05) than that in pediatric CHB, but they were all within the normal range. Notably, the cirrhosis group showed significantly lower median quantification HBV DNA loads (log10IU/mL: 6.3 vs 17.4, P < 0.001), reduced HBsAg titers (log10IU/mL: 3.11 vs 8.956, P < 0.0001), and diminished HBeAg positive rate (81.4% vs 93.8%, P < 0.05). These multidimensional disparities underscore distinct pathophysiological trajectories between pediatric CHB and established cirrhosis.

| Variable | Liver cirrhosis (n = 62) | Chronic hepatitis B (n = 64) | P value |

| Demographics | |||

| Age (years) | 11 (4-14) | 10.5 (3-15) | 0.7237 |

| Sex | 0.128 | ||

| Male | 54 (87.1) | 49 (76.6) | |

| Female | 8 (12.9) | 15 (23.4) | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 16.76 (15.45-20.67) | 17.28 (15.43-19.87) | 0.6623 |

| Biochemistry | |||

| ALT (U/L) | 107.5 (58.5-207.25) | 95 (44-176) | 0.9829 |

| AST (U/L) | 110.5 (64.25-169.5) | 76 (56-147) | 0.6596 |

| GGT (U/L) | 70.5 (48-105) | 23 (14-54) | < 0.0001 |

| ALP (U/L) | 299 (232.25-373) | 273 (193-349) | 0.0852 |

| ALB (g/L) | 39 (36-41.25) | 40 (38-43) | 0.0011 |

| TBIL (μmol/L) | 11.05 (8.1-19.15) | 8.5 (6.3-11.7) | 0.0277 |

| DBIL (μmol/L) | 4.7 (3.08-8.48) | 3.1 (2-4.7) | 0.0008 |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | 1.15 (0.97-1.4) | 1.18 (1.02 1.35) | 0.7982 |

| LDL-C (mmol/L) | 2.27 (2.02-2.85) | 2.28 (2.04-2.86) | 0.631 |

| TG (mmol/L) | 0.94 (0.75-1.28) | 0.86 (0.68-1) | 0.0461 |

| Cr (μmol/L) | 48.68 ± 14.11 | 51.6 ± 15.41 | 0.2733 |

| HGB (g/L) | 127.84 ± 14.45 | 131.19 ± 12.05 | 0.1622 |

| PLT (109/L) | 165 (113.5-221) | 236 (206.75-284.75) | < 0.0001 |

| WBC (109/L) | 6.19 (4.67-7.63) | 6.56 (5.04-8.45) | 0.0718 |

| Lymphocyte (109/L) | 3.15 (2.12-4.26) | 2.97 (2.17-4.1) | 0.726 |

| Neutrophil (109/L) | 3.175 (2.15-4.27) | 2.5 (1.94-3.11) | 0.002 |

| log10(qHBV DNA) | 6.3 (4.58-7.54) | 17.4 (15.41-18.62) | 0.0003 |

| log10(qHBsAg) | 3.11 (0-3.69) | 8.956 (7.78-10.28) | < 0.0001 |

| HBeAg(+) | 48 (81.4) | 60 (93.8) | 0.0361 |

| PT (seconds) | 12.3 (11.55-13.35) | 11.5 (10.98-12.2) | < 0.0001 |

We analyzed differences in key clinical and demographic characteristics between 62 pediatric LC and 69 adult LC patients. Pediatric patients had no cases of hepatic encephalopathy or gastrointestinal bleeding, whereas 5.8% and 59.4% of adult patients experienced these serious conditions, respectively, and ascites was present in 6.5% of pediatric patients compared to 8.7% of adults (P < 0.0001). We also find that a notably higher proportion of pediatric patients were asymptomatic (77.4%) compared to adult patients (11.6%) as they first diagnosed as LC, pediatric LC showed milder initial symptoms compared with adult patients such as fatigue (4.8% vs 27.5%), abdominal discomfort (9.7% vs 23.2%), nausea (0% vs 10.1%), and poor appetite (6.5% vs 8.7%; all P < 0.0001). Only 12.9% of pediatric patients had received antiviral therapy before LC, which was significantly lower than that of 53.8% in adult LC (P < 0.0001).

Biochemical analyses revealed that pediatric patients had significantly higher alanine aminotransferase [107.5 (58.5–207.25) U/L vs 29 (18–42) U/L], aspartate aminotransferase [110.5 (64.25–169.5) U/L vs 39 (26–53.5) U/L], ALP [299 (232.25-373) U/L vs 70.5 (58–86) U/L], and GGT [70.5 (48–105) U/L vs 28 (18–46.5) U/L; all P < 0.0001] than adult LC. Pediatric patients also had higher ALB [39 (36–41.25) g/L vs 36 (32-38.5) g/L; P = 0.0003] compared with adult LC. In contrast, total bilirubin in pediatric patients was 11.05 (8.1–19.15) μmol/L, which was lower than that in adult patients as 11.9 (12.65–24.9) μmol/L (P = 0.0002), and direct bilirubin was 4.7 (3.08–8.48) μmol/L in pediatric patient’s vs 8.3 (5.3–11.25) μmol/L in adult patients (P < 0.0001). Metabolic parameters showed that pediatric patients had higher low-density lipoprotein [2.27 (2.02-2.85) mmol/L vs 1.79 (1.56-2.56) mmol/L; P = 0.0018] and lower high-density lipoprotein [1.15 (0.97–1.4) mmol/L vs 1.83 (1.57–2.63) mmol/L; P = 0.008] than those in adult patients. Pediatric patients had lower creatinine (48.68 ± 14.11 μmol/L vs 75.61 ± 15.29 μmol/L; P < 0.0001) and lower glucose [4.5 (4.08–4.89) mmol/L vs 5 (4.26–6.29) mmol/L; P = 0.004) than those in adult patients.

Hematological analyses demonstrated that pediatric patients had elevations in haemoglobin (127.84 ± 14.45 g/L vs 103.38 ± 22.29 g/L, P < 0.0001), PLT [165 (113.5-221) × 109/L vs 91 (53.5-149) × 109/L, P = 0.0072], and lymphocytes [3.15 (2.12-4.26) × 109/L vs 0.79 (0.55-1.49) × 109/L; P < 0.0001], but reduced white blood cell [6.19 (4.67-7.62) × 109/L vs 7.24 (3.31-10.91) × 109/L; P = 0.0062] and neutrophils [2.02 (1.43-2.75) × 109/L vs 5.05 (2.14-9.18) × 109/L; P < 0.0001] than those in adult patients.

Virological profiling revealed that pediatric patients had significantly higher median log10(quantification HBV DNA) [6.3 (4.58-7.54) vs 0 (0–5.43); P < 0.0001] and log10(quantification HBsAg) [3.11 (0-3.69) vs 5.19 (3-9.11); P < 0.0001], with a greater proportion of HBeAg positive patients (81.4% vs 39.1%; P < 0.0001) than those in adult patients. Moreover, AFP levels were higher in pediatric patients [51 (13.73-26) ng/mL vs 3.97 (1.96-12.5) ng/mL; P = 0.0261] than that in adult patients. While pediatric patients had shorter PT [12.3 (11.55-13.35) seconds vs 13.7 (12.9-15) seconds; P < 0.0001] and lower international normalized ratio [1.055 (0.99-1.14) vs 1.18 (1.11-1.28; P < 0.0001] than those in adult patients (Table 4).

| Variable | Pediatric (n = 62) | Adult (n = 69) | P value |

| Demographics | |||

| Age (years) | 11(4-14) | 43(34-46.5) | < 0.0001 |

| Sex | 0.9812 | ||

| Male | 54 (87.1) | 60 (87) | |

| Female | 8 (12.9) | 9 (13) | |

| Comorbidity | < 0.0001 | ||

| Hepatic encephalopathy | 0 (0) | 4 (5.8) | |

| Ascites | 4 (6.5) | 6 (8.7) | |

| Gastrointestinal bleeding | 0 (0) | 41 (59.4) | |

| Presenting symptoms of cirrhosis | < 0.0001 | ||

| Asymptomatic | 48 (77.4) | 8 (11.6) | |

| Fatigue | 3 (4.8) | 19 (27.5) | |

| Jaundice | 4 (6.5) | 3 (4.4) | |

| Abdominal discomfort | 6 (9.7) | 16 (23.2) | |

| Gastrointestinal bleeding | 2 (3.2) | 41 (59.4) | |

| Nausea | 0 (0) | 7 (10.1) | |

| Poor appetite | 4 (6.5) | 6 (8.7) | |

| Antiviral therapy before LC | 8 (12.9) | 35 (53.8) | < 0.0001 |

| History of self-discontinuation of antiviral therapy | 8 (12.9) | 8 (11.6) | 0.821 |

| Biochemistry | |||

| ALT (U/L) | 107.5 (58.5-207.25) | 29 (18-42) | < 0.0001 |

| AST (U/L) | 110.5 (64.25-169.5) | 39 (26-53.5) | < 0.0001 |

| GGT (U/L) | 70.5 (48-105) | 28 (18-46.5) | < 0.0001 |

| ALP (U/L) | 299 (232.25-373) | 70.5 (58-86) | < 0.0001 |

| ALB (g/L) | 39 (36-41.25) | 36 (32-38.5) | 0.0003 |

| TBIL (μmol/L) | 11.05 (8.1-19.15) | 11.9 (12.65-24.9) | 0.0002 |

| DBIL (μmol/L) | 4.7 (3.08-8.48) | 8.3 (5.3-11.25) | < 0.0001 |

| Glucose (mmol/L) | 4.5 (4.08-4.89) | 5 (4.26-6.29) | 0.004 |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | 1.15 (0.97-1.4) | 1.83 (1.57-2.63) | 0.008 |

| LDL-C (mmol/L) | 2.27 (2.02-2.85) | 1.79 (1.56-2.56) | 0.0018 |

| TG (mmol/L) | 0.94 (0.75-1.28) | 0.78 (0.57-1.17) | 0.06226 |

| Cr (μmol/L) | 48.68 ± 14.11 | 75.61 ± 15.29 | < 0.0001 |

| HGB (g/L) | 127.84 ± 14.45 | 103.38 ± 22.29 | < 0.0001 |

| PLT (109/L) | 165 (113.5-221) | 91 (53.5-149) | 0.0072 |

| WBC (109/L) | 6.19 (4.67-7.62) | 7.24 (3.31-10.91) | 0.0062 |

| Lymphocyte (109/L) | 3.15(2.12-4.26) | 0.79 (0.55-1.49) | < 0.0001 |

| Neutrophil (109/L) | 3.175 (2.15-4.27) | 5.05 (2.14-9.18) | < 0.0001 |

| log10(qHBV DNA) | 6.3 (4.58-7.54) | 0 (0-5.43) | < 0.0001 |

| log10(qHBsAg) | 3.11 (0-3.69) | 5.19 (3-9.11) | 0.465 |

| HBeAg(+) | 48 (81.4) | 27 (39.1) | < 0.0001 |

| AFP (ng/mL) | 51 (13.73-255) | 3.97 (1.96-12.5) | 0.0261 |

| PT (seconds) | 12.3 (11.55-13.35) | 13.7 (12.9-15) | < 0.0001 |

| INR | 1.06 (0.99-1.14) | 1.18 (1.11-1.28) | < 0.0001 |

We defined LC patients’ progression to HCC or liver failure as end point event, and a reduction in fibrosis by at least one degree in cirrhosis patients was defined as remission (diagnosed by either CT/MRI/Liver stiffness measurement). The number of adults progressing to end point event was 11 (16.41%), and none of the children progressed after regular antiviral therapy. In contrast, none of the adult LC patients get remission after regular antiviral therapy, but 31 (58.49%) of the pediatric LC achieved fibrosis remission of varying degrees. The survival analysis showed that the incidence of progression of cirrhosis in children after antiviral therapy continues to be much lower than that in adults LC (hazard ratio = 6.102, 95% confidence interval: 1.72-21.65, P = 0.00051). While the incidence of remission of LC in children after antiviral therapy continues to be much higher than that in adults LC (hazard ratio = 0.055, 95% confidence interval: 0.07128-0.2802, P < 0.0001; Figure 3).

Moreover, correlation analysis revealed distinct prognostic markers between pediatric and adult cirrhosis patients. The remission of pediatric LC was significantly associated with multiple indicators, including glucose, HBV DNA, HBsAg, AFP, and immune cell subsets (T lymphocytes, B lymphocytes, natural killer cells, and cluster of differentiation 4 positive T cells). While in adult cirrhosis patients the progression or remission exhibited differential correlations with international normalized ratio and genotype, as detailed in Tables 5 and 6.

| Variable | Univariate Cox [HR (95%CI)] | P value | Multivariate Cox [HR (95%CI)] | P value |

| Sex | 1.743 (0.659-4.607) | 0.263 | ||

| Age | 0.955 (0.893-1.021) | 0.177 | ||

| Genotype | 1.367 (0.771-2.423) | 0.285 | ||

| Biochemistry | ||||

| ALT | 1.001 (0.999-1.003) | 0.284 | ||

| AST | 1.001 (0.998-1.003) | 0.587 | ||

| GGT | 1.006 (1.003-1.009) | 0.0001 | 1 (0.992-1.008) | 0.939 |

| ALP | 1.001 (0.997-1.004) | 0.741 | ||

| ALB | 1.007 (0.927-1.093) | 0.873 | ||

| TBIL | 1.008 (0.985-1.031) | 0.507 | ||

| DBIL | 1.009 (0.976-1.042) | 0.608 | ||

| Glucose | 0.356 (0.167-0.756) | 0.007 | 0.159 (0.032-0.788) | 0.024 |

| HDL | 2.183 (0.638-7.469) | 0.213 | ||

| LDL | 1.592 (0.937-2.707) | 0.086 | ||

| TG | 0.556 (0.233-1.325) | 0.185 | ||

| HGB | 1.005 (0.978-1.033) | 0.717 | ||

| PLT | 1.004 (0.999-1.008) | 0.121 | ||

| WBC | 1.149 (0.992-1.33) | 0.064 | ||

| Lymphocyte | 1.214 (0.974-1.514) | 0.085 | ||

| Neutrophil | 1.155 (0.823-1.62) | 0.404 | ||

| HBV DNA | 1.296 (1.046-1.605) | 0.018 | 1.133 (0.748-1.718) | 0.555 |

| HBsAg | 1.428 (1.089-1.873) | 0.01 | 1.951 (0.954-3.993) | 0.067 |

| HBeAg | 2.109 (0.638-6.973) | 0.222 | ||

| AFP | 1.001 (1-1.001) | 0.002 | 1.001 (1-1.002) | 0.003 |

| T lymphocyte | 1 (1-1.001) | 0.043 | 0.999 (0.998-1.001) | 0.33 |

| B lymphocyte | 1 (1-1.001) | 0.045 | 0.999 (1.001-1.003) | 0.43 |

| NK | 1.003 (1.001-1.005) | 0.003 | 1.004 (1-1.008) | 0.063 |

| CD8+ | 1 (1-1.001) | 0.137 | ||

| CD4+ | 1.001 (1-1.002) | 0.014 | 1 (0.997-1.003) | 0.819 |

| CD4/CD8 | 1.061 (0.512-2.199) | 0.874 | ||

| PT | 1.02 (0.801-1.299) | 0.873 | ||

| INR | 0.905 (0.027-30.07) | 0.956 | ||

| Cr | 0.993 (0.996-1.02) | 0.603 | ||

| Variable | Progression univariate Cox [HR (95%CI)] | P value | Remission univariate Cox [HR (95%CI)] | P value |

| Sex | 0.036 (0-77.861) | 0.397 | 0.04 (0-1544639.826) | 0.714 |

| Age | 1.045 (0.936-1.167) | 0.437 | 0.66 (0.411-1.061) | 0.086 |

| Genotype | 0.178 (0.001-43.643) | 0.539 | 7.533 (1.388-40.875) | 0.019 |

| Biochemistry | ||||

| ALT | 1.011 (0.975-1.049) | 0.549 | 0.994 (0.908-1.088) | 0.889 |

| AST | 1.01 (0.983-1.038) | 0.473 | 0.967 (0.877-1.066) | 0.501 |

| GGT | 1.008 (0.995-1.021) | 0.236 | 1.003 (0.976-1.03) | 0.847 |

| ALP | 1.022 (0.995-1.049) | 0.107 | 1.028 (0.986-1.071) | 0.196 |

| ALB | 0.997 (0.88-1.128) | 0.956 | 1.345 (0.913-1.983) | 0.134 |

| TBIL | 1.055 (0.981-1.135) | 0.15 | 1 (0.859-1.164) | 0.997 |

| DBIL | 1.051 (0.936-1.181) | 0.397 | 1.098 (0.912-1.323) | 0.322 |

| Glucose | 1.239 (0.973-1.577) | 0.083 | 0.536 (0.097-2.972) | 0.476 |

| HDL | 0.382 (0.076-1.913) | 0.241 | 1.348 (0.213-8.539) | 0.751 |

| LDL | 0.483 (0.029-8.003) | 0.611 | 0.232 (0.003-16.995) | 0.505 |

| TG | 0.836 (0.078-8.926) | 0.883 | 1.111 (0.036-34.669) | 0.952 |

| HGB | 1.003 (0.977-1.03) | 0.826 | 0.984 (0.922-1.051) | 0.636 |

| PLT | 0.999 (0.991-1.006) | 0.75 | 0.996 (0.975-1.017) | 0.718 |

| WBC | 1.012 (0.926-1.107) | 0.788 | 0.857 (0.585-1.254) | 0.426 |

| Lymphocyte | 0.463 (0.108-1.979) | 0.299 | 1.812 (0.274-11.985) | 0.537 |

| Neutrophil | 1.018 (0.926-1.12) | 0.708 | 0.789 (0.451-1.383) | 0.408 |

| HBV DNA | 0.821 (0.637-1.059) | 0.129 | 1.148 (0.916-1.439) | 0.231 |

| HBeAg | 2.45 (0.585-10.262) | 0.22 | 0.021 (0-2501.23) | 0.518 |

| AFP | 1.001 (0.999-1.002) | 0.534 | 1.001 (0.998-1.004) | 0.528 |

| PT | 1.316 (0.978-1.771) | 0.069 | 0.394 (0.079-1.95) | 0.254 |

| INR | 16.58 (1.057-260.027) | 0.046 | 0.01 (0-2444.004) | 0.468 |

| Cr | 1 (0.958-1.044) | 0.992 | 1.013 (0.927-1.107) | 0.778 |

LC represents one of the most significant global public health challenges, with its complex pathophysiology and variable clinical manifestations presenting substantial burdens to healthcare systems worldwide[21]. While traditionally considered a disease of adulthood, our study reveals that pediatric cirrhosis exhibits distinct epidemiological, clinical and pathological characteristics that challenge this paradigm. The progression from hepatic fibrosis to end-stage cirrhosis, while often insidious, can sometimes be prevented or delayed through early intervention - particularly relevant for pediatric cases where the disease course appears markedly accelerated compared to adults.

HBV infection emerged as the predominant cause of cirrhosis among young children, which reflects both the endemic nature of HBV in our region and the consequences of vertical transmission. Maternal HBV DNA levels are closely correlated with neonatal infection risk, with higher transmission rates observed in HBeAg-positive mothers or those with elevated HBV viral loads[22]. In our group, children aged younger than 2 years old can progress to LC [13 (20.97%)]. Clinically, pediatric cirrhosis demonstrated a "silent" presentation pattern, with 48 (77.4%) of cases detected incidentally during routine examinations, compared to only 8 (11.6%) of adults. And adult patients predominantly presented with overt symptoms including gastrointestinal bleeding (59.4% vs 3.2%), abdominal discomfort (23.2% vs 9.7%), nausea (10.1% vs 0%), poor appetite (8.7% vs 6.5%) and fatigue (27.5% vs 4.8%; P < 0.001). This discrepancy likely reflects both immunological and developmental factors: (1) Immature immune responses in children may result in less vigorous inflammatory reactions; and (2) Limited symptom reporting capability in pediatric populations. Paradoxically, this asymptomatic progression may contribute to diagnostic delays, therefore, the management plan for pediatric CHB should be clearly distinguished from that in CHB adults.

Pediatric LC had comparable HBsAg levels as adult LC [log10(quantification HBsAg) 3.11 (0-3.69) vs 5.19 (3-9.11), P = 0.465]. But they had higher levels of HBV DNA compared with adult LC [log10(quantification HBV DNA) 6.3 (4.58-7.54) vs 0 (0-5.43); P < 0.0001]. This may be attributed to the fact that most pediatric patients not received antiviral therapy before LC was diagnosed, while most adult patients had received antiviral therapy before LC (12.9% vs 53.8%, P < 0.0001). At the histopathological level, pediatric livers exhibited enhanced vulnerability to fibrogenesis. Risk factors accelerated fibrotic progression may be attributed to developmental factors including: (1) Persistent activation of growth factor pathways (e.g., transforming growth factor-beta) promoting hepatic stellate cell activation; (2) Immature antioxidant defense systems increasing susceptibility to oxidative damage; and (3) Ongoing liver maturation processes that may alter extracellular matrix remodeling[23-25]. Although these mechanisms have also been reported in adults, they may be more pronounced in children due to differences in developmental stages[26].

Therapeutic outcomes revealed important age-related differences. Pediatric patients showed superior responses to antiviral therapy, with 17.4% achieving functional cure compared to 0% of adults (P < 0.0001). This result is also reflected in the study of Wang et al[27] with 3/320 adult patients achieved functional cure. Extensive research has consistently demonstrated that pediatric patients with CHB achieved higher cure rates after receiving antiviral therapy compared to adults’ patients. This study further reveals that even among patients with CHB-related LC, the rate of HBV clearance remains significantly higher in the pediatric population than that in adults. Most remarkably, one child aged 10 years old demonstrated fibrosis stage regression on follow-up biopsy, from LC to stage 1 liver fibrosis after antiviral therapy for 4.66 years using interferon and nucleos(t)ide analogue combination therapy. The number of adults progressing to HCC or liver failure was 11 (16.41%), and none of the children progressed after regular antiviral therapy. In contrast, none of the adult LC patients get remission after regular antiviral therapy, but 31 (58.49%) of the pediatric LC achieved fibrosis remission of varying degrees. This large difference in prognosis can be explained by their cirrhosis status, the ALB levels [39 (36-41.25) g/L vs 36 (32-38.5) g/L; P = 0.0003], haemoglobin levels (127.84 ± 14.45 g/L vs 103.38 ± 22.29 g/L; P < 0.0001) and PLT levels [165 (113.5-221) × 109/L vs 91 (53.5-149) × 109/L; P = 0.0072] in pediatric patients were higher compared to those in adult patients. However, a study indicated that four patients who had cirrhosis at baseline (Ishak fibrosis score ≥ 5) all showed improvement in their Ishak fibrosis scores, with a median decrease of 3 points[28]. These findings challenge traditional concepts about cirrhosis irreversibility and suggest enhanced regenerative capacity in developing livers. However, treatment adherence remains a significant challenge, with 8 (12.9%) of pediatric cases and 8 (11.6%) reporting treatment interruptions - none of them achieved functional cure in our group.

From a public health perspective, our data support several strategic recommendations for HBV-endemic regions: (1) Implementation of early screening protocols (since they were diagnosed with CHB) for vertically infected children; (2) Development of pediatric-specific risk prediction models incorporating viral, genetic and clinical parameters; and (3) Enhanced family education programs to improve treatment adherence.

Our study provides actionable insights for managing pediatric HBV-related cirrhosis. The identified clinical and pathological features enable better risk stratification, helping clinicians identify children at high risk for rapid fibrosis progression who would benefit from closer monitoring and earlier intervention. The characteristically elevated virological markers and transaminase levels occurring without symptoms highlight the need for increased vigilance in at-risk pediatric populations. Our data support early initiation of potent antiviral therapy, particularly interferon and nucleos(t)ide analogue combinations, which achieved high functional cure and fibrosis regression rates. Additionally, pediatric-specific prognostic markers such as GGT, platelet count, and HBsAg titer can guide individualized treatment and long-term follow-up. Integrating these findings into practice will allow clinicians to optimize treatment timing, enhance adherence through family education, and ultimately improve long-term outcomes in children with HBV-related cirrhosis.

Several limitations must be acknowledged: The study’s limitations include: (1) Its limited sample size, which may constrain statistical power. The single-center design and biopsy-confirmed group may overrepresent advanced disease may limit generalizability. Lack of data on antiviral prevention measures for pregnant women, hepatitis B vaccination for newborns, and injection of hepatitis B immune globulin. Future research should require multicenter studies to validate our findings; (2) Long-term outcome data require extended follow-up, future efforts should prioritize the development of non-invasive pediatric fibrosis biomarkers; (3) Mother-to-child transmission was the primary route of pediatric HBV infection, lack of other transmission routes (e.g. horizontal transmission, regional variations, or the impact of large-scale vaccination programs) due to the characteristics in our group; (4) The molecular mechanisms underlying cirrhosis regression remain incompletely understood, and therefore future research should prioritize mechanistic investigations of liver regeneration in developing organisms; and (5) Collect cases that contain data related to antiviral prevention measures for pregnant women, hepatitis B vaccination for newborns, and injection of hepatitis B immune globulin.

This study delineates pediatric HBV-related cirrhosis as a distinct clinical entity characterized by rapid progression, subtle presentations but favorable treatment responses. These insights not only advance our understanding of liver disease pathogenesis across developmental stages but also provide evidence-based rationale for optimizing management strategies in this vulnerable population. Through integrated approaches combining early detection, targeted therapies and comprehensive care systems, we can potentially transform outcomes for children with cirrhosis worldwide.

The authors wish to thank all the patients and family members that participated in the study.

| 1. | Ginès P, Krag A, Abraldes JG, Solà E, Fabrellas N, Kamath PS. Liver cirrhosis. Lancet. 2021;398:1359-1376. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 211] [Cited by in RCA: 1071] [Article Influence: 214.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 2. | Hindson J. New insights into aetiology of paediatric liver cirrhosis. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;19:623. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Flores-Calderón J, Cisneros-Garza LE, Chávez-Barrera JA, Vázquez-Frias R, Reynoso-Zarzosa FA, Martínez-Bejarano DL, Consuelo-Sánchez A, Reyes-Apodaca M, Zárate-Mondragón FE, Sánchez-Soto MP, Alcántara-García RI, González-Ortiz B, Ledesma-Ramírez S, Espinosa-Saavedra D, Cura-Esquivel IA, Macías-Flores J, Hinojosa-Lezama JM, Hernández-Chávez E, Zárate-Guerrero JR, Gómez-Navarro G, Bilbao-Chávez LP, Sosa-Arce M, Flores-Fong LE, Lona-Reyes JC, Estrada-Arce EV, Aguila-Cano R. Consensus on the management of complications of cirrhosis of the liver in pediatrics. Rev Gastroenterol Mex (Engl Ed). 2022;87:462-485. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Hsu YC, Huang DQ, Nguyen MH. Global burden of hepatitis B virus: current status, missed opportunities and a call for action. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;20:524-537. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 366] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Zhong YW, Di FL, Liu C, Zhang XC, Bi JF, Li YL, Wu SQ, Dong H, Liu LM, He J, Shi YM, Zhang HF, Zhang M. Hepatitis B virus basal core promoter/precore mutants and association with liver cirrhosis in children with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2016;22:379.e1-379.e8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Liu Z, Mao X, Jin L, Zhang T, Chen X. Global burden of liver cancer and cirrhosis among children, adolescents, and young adults. Dig Liver Dis. 2020;52:240-243. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Cordova J, Jericho H, Azzam RK. An Overview of Cirrhosis in Children. Pediatr Ann. 2016;45:e427-e432. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Dong Y, Li A, Zhu S, Chen W, Li M, Zhao P. Biopsy-proven liver cirrhosis in young children: A 10-year cohort study. J Viral Hepat. 2021;28:959-963. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Hu Y, Wu X, Ye Y, Ye L, Han S, Wang X, Yu H. Liver histology of treatment-naïve children with chronic hepatitis B virus infection in Shanghai China. Int J Infect Dis. 2022;123:112-118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Yin X, Wang W, Chen H, Mao Q, Han G, Yao L, Gao Q, Gao Y, Jin J, Sun T, Qi M, Zhang H, Li B, Duan C, Cui F, Tang W, Chan P, Liu Z, Hou J; SHIELD Study Group. Real-world implementation of a multilevel interventions program to prevent mother-to-child transmission of HBV in China. Nat Med. 2024;30:455-462. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 20.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Abdel-Hady M, Kelly D. Chronic hepatitis B in children and adolescents: epidemiology and management. Paediatr Drugs. 2013;15:311-317. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Chinese Society of Hepatology; Chinese Medical Association; Chinese Society of Infectious Diseases, Chinese Medical Association. [Guidelines for the prevention and treatment of chronic hepatitis B (version 2022)]. Zhonghua Gan Zang Bing Za Zhi. 2022;30:1309-1331. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Mack CL, Adams D, Assis DN, Kerkar N, Manns MP, Mayo MJ, Vierling JM, Alsawas M, Murad MH, Czaja AJ. Diagnosis and Management of Autoimmune Hepatitis in Adults and Children: 2019 Practice Guidance and Guidelines From the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology. 2020;72:671-722. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 282] [Cited by in RCA: 648] [Article Influence: 108.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Fontana RJ, Liou I, Reuben A, Suzuki A, Fiel MI, Lee W, Navarro V. AASLD practice guidance on drug, herbal, and dietary supplement-induced liver injury. Hepatology. 2023;77:1036-1065. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 44.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Strassburg CP. Hyperbilirubinemia syndromes (Gilbert-Meulengracht, Crigler-Najjar, Dubin-Johnson, and Rotor syndrome). Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;24:555-571. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Ferreira CR, Cassiman D, Blau N. Clinical and biochemical footprints of inherited metabolic diseases. II. Metabolic liver diseases. Mol Genet Metab. 2019;127:117-121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 17. | You H, Sun YM, Zhang MY, Nan YM, Xu XY, Li TS, Wang GQ, Hou JL, Duan ZP, Wei L, Wang FS, Jia JD, Zhuang H. [Interpretation of the essential updates in guidelines for the prevention and treatment of chronic hepatitis B (Version 2022)]. Zhonghua Gan Zang Bing Za Zhi. 2023;31:385-388. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Chinese Society of Hepatology; Chinese Medical Association. [Chinese guidelines on the management of liver cirrhosis]. Zhonghua Gan Zang Bing Za Zhi. 2019;27:846-865. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Brunt EM, Janney CG, Di Bisceglie AM, Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Bacon BR. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: a proposal for grading and staging the histological lesions. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:2467-2474. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2702] [Cited by in RCA: 2930] [Article Influence: 108.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 20. | Brunt EM. Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: Pros and Cons of Histologic Systems of Evaluation. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17:97. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Li M, Wang ZQ, Zhang L, Zheng H, Liu DW, Zhou MG. Burden of Cirrhosis and Other Chronic Liver Diseases Caused by Specific Etiologies in China, 1990-2016: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Biomed Environ Sci. 2020;33:1-10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Lu Y, Zhu FC, Liu JX, Zhai XJ, Chang ZJ, Yan L, Wei KP, Zhang X, Zhuang H, Li J. The maternal viral threshold for antiviral prophylaxis of perinatal hepatitis B virus transmission in settings with limited resources: A large prospective cohort study in China. Vaccine. 2017;35:6627-6633. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Neshat SY, Quiroz VM, Wang Y, Tamayo S, Doloff JC. Liver Disease: Induction, Progression, Immunological Mechanisms, and Therapeutic Interventions. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:6777. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Lin J, Wu JF, Zhang Q, Zhang HW, Cao GW. Virus-related liver cirrhosis: molecular basis and therapeutic options. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:6457-6469. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | You H, Wang X, Ma L, Zhang F, Zhang H, Wang Y, Pan X, Zheng K, Kong F, Tang R. Insights into the impact of hepatitis B virus on hepatic stellate cell activation. Cell Commun Signal. 2023;21:70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Parola M, Pinzani M. Liver fibrosis: Pathophysiology, pathogenetic targets and clinical issues. Mol Aspects Med. 2019;65:37-55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 286] [Cited by in RCA: 864] [Article Influence: 108.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Wang Q, Zhao H, Deng Y, Zheng H, Xiang H, Nan Y, Hu J, Meng Q, Xu X, Fang J, Xu J, Wang X, You H, Pan CQ, Xie W, Jia J. Validation of Baveno VII criteria for recompensation in entecavir-treated patients with hepatitis B-related decompensated cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2022;77:1564-1572. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 21.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Chang TT, Liaw YF, Wu SS, Schiff E, Han KH, Lai CL, Safadi R, Lee SS, Halota W, Goodman Z, Chi YC, Zhang H, Hindes R, Iloeje U, Beebe S, Kreter B. Long-term entecavir therapy results in the reversal of fibrosis/cirrhosis and continued histological improvement in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2010;52:886-893. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 721] [Cited by in RCA: 788] [Article Influence: 49.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/