Published online Dec 21, 2025. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v31.i47.113496

Revised: October 11, 2025

Accepted: November 11, 2025

Published online: December 21, 2025

Processing time: 114 Days and 19 Hours

Liver fibrosis is a global health issue that lacks effective treatments. Tibetan medi

To investigate the efficacy of the Saf-Cal b therapy in treating liver fibrosis and explored its underlying mechanism.

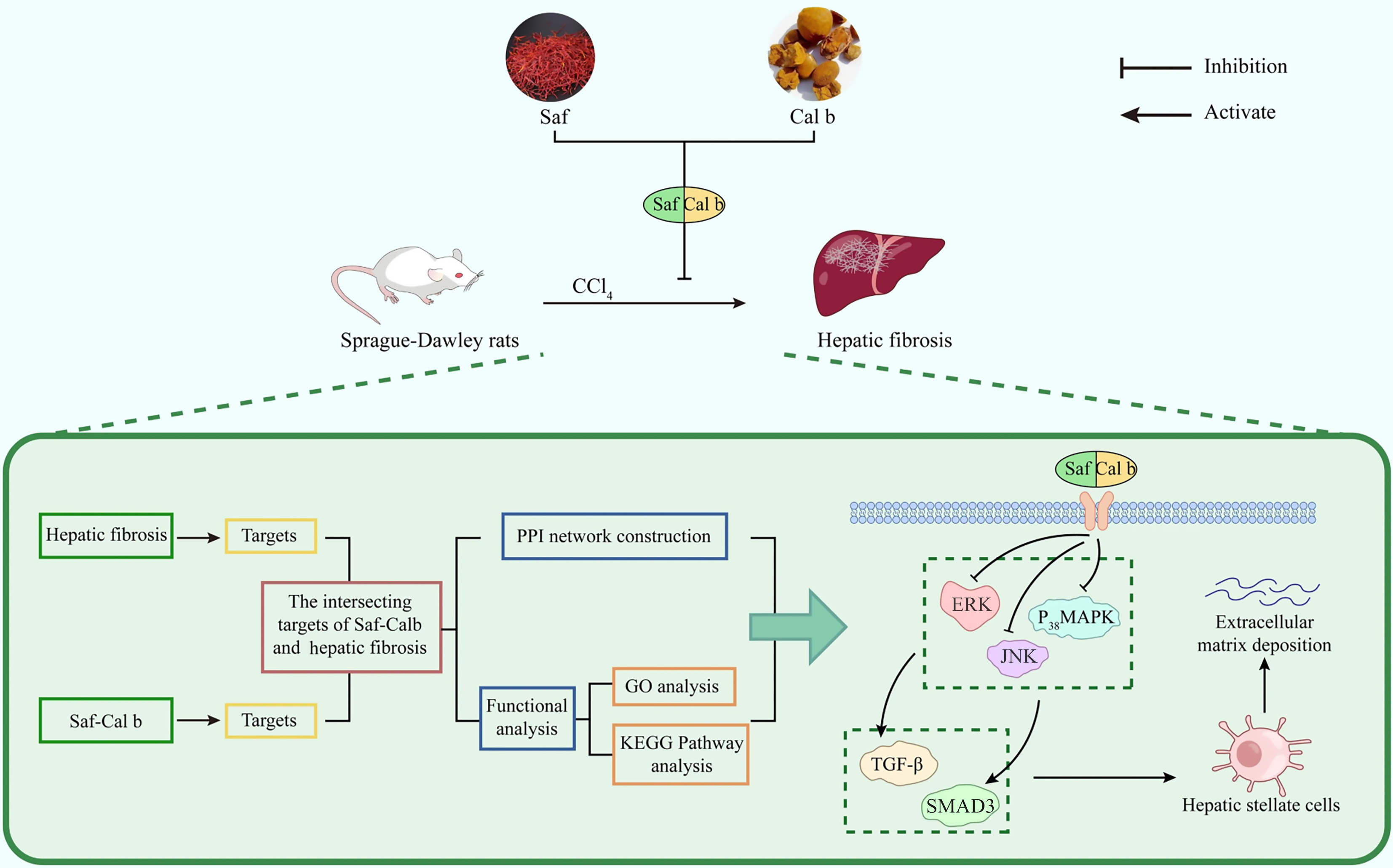

We initially established a carbon tetrachloride-induced rat liver fibrosis model to assess Saf-Cal b’s anti-fibrotic effects. Subsequently, we conducted network phar

Saf-Cal b combination therapy exerted superior effects in ameliorating liver fibrosis in model rats compared with Saf or Cal b monotherapy. Through network pharmacology prediction, key targets of the combination were identified. Mecha

These findings demonstrate that Saf-Cal b combination therapy is more effective than either monotherapy in alleviating liver fibrosis, with its therapeutic effect mediated through the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinases/transforming growth factor-β/small mother against decapentaplegic signaling axis, providing a potential therapeutic strategy for liver fibrosis.

Core Tip: Liver fibrosis, a health issue of global concern, lacks effective treatments. Using Tibetan medicine experience and network pharmacology, this study explored the potential mechanism of the saffron-Calculus bovis combination against liver fibrosis in rats. After CCl4 induction of rats, intragastric intervention was performed, followed by assessments of liver pathology, liver function, inflammation, and hepatic stellate cell activation. The results showed that the combination exerted more significant anti-fibrotic effects compared with single treatment, and it may act by regulating the mito

- Citation: Sun SN, Wang K, Xu Y, Ye F, Xia WN, Wang ZW, Liu F, He ZX, Chen M, Du QH. Saffron and Calculus bovis combination exerts anti-hepatic fibrotic effect in liver fibrosis rats via the mitogen-activated protein kinases pathway. World J Gastroenterol 2025; 31(47): 113496

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v31/i47/113496.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v31.i47.113496

Liver disease causes 2 million deaths worldwide annually, with mortality primarily attributed to end-stage liver fibrosis[1]. Liver fibrosis is a healing reaction that is in

Tibetan medicine, with a millennia-old historical legacy, has evolved into a comprehensive medical system characterized by a systematic, well-established, and distinctive theoretical foundation. As a result of the special geographical environment and dietary habits of the Tibetan people, as well as long-term clinical practices, Tibetan medicine has developed unique insights into liver diseases[4]. In current clinical practice of Tibetan medicine, there are 22 compound formulations used for the treatment of chronic liver diseases. Among these, the formulations containing Saffron (Saf) and Cal b include Shisanwei Shugan Capsules, Ershiwuwei Songshi Pills, and Bawei Honghua Qingganre Powder, etc. Saf is the most prevalent medicinal component and incorporated in 18 formulations (81.8%). Calculus bovis (Cal b) is present in 13 preparations (59.1%)[5]. The Saf-Cal b combination is the predominant therapeutic pairing for chronic hepatic dis

Crocus sativus Linnaeus, commonly referred to as Saf or Tibetan Saf, is a perennial herbaceous species in the Iridaceae family, genus Crocus. This commercially valuable spice crop exhibits a broad geographical distribution and is predominantly cultivated in temperate regions spanning Europe, the Mediterranean basin, and Central Asia. In the 2020 edition of the Chinese Pharmacopoeia, Saf is pharmacologically characterized by its sweet flavor profile and neutral thermal property, with specific tropism toward the heart and liver meridians[7]. This medicinal agent exhibits multiple therapeutic properties, including blood-activating and stasis-resolving effects, blood-cooling and detoxification actions, and mood-regulating and sedative functions. Clinically, Saf is indicated for various pathological conditions such as menstrual disorders, postpartum complications, heat-toxin-induced dermatological manifestations, depressive disorders, and psychosomatic symptoms including anxiety and agitation[8].

Cal b is the dried gallstone from the cow Bos taurus domesticus Gmelin. The 2020 edition of the Chinese Pharmacopoeia reports that Cal b has distinct bitter medicinal properties and a cooling nature, with specific meridian tropism targeting the cardiac and hepatic systems[7]. This traditional medicinal substance exhibits multi-modal therapeutic actions, including cardiac heat-clearing and phlegm-resolving properties, orifice-opening and hepatic-cooling effects, and wind-extinguishing and detoxification capabilities. Clinical applications primarily include neurological disorders (e.g., febrile delirium and cerebrovascular events with phlegm obstruction), convulsive disorders (including epilepsy and seizure-related conditions), psychiatric manifestations (such as manic episodes), and inflammatory conditions (including pharyngolaryngeal inflammation, oral ulcerations, and suppurative dermatological lesions)[9].

Hepatic stellate cell (HSC) activation is a crucial driving force underlying fibrogenic progression in chronic liver diseases[10,11]. Following HSC activation, α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) expression is significantly upregulated, establishing α-SMA as a reliable molecular marker for HSC activation. Some mechanistic studies have demonstrated that the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathway plays a crucial regulatory role in modulating α-SMA protein expression in activated HSCs, while simultaneously influencing cell cycle progression, thereby contributing to the pathogenesis and progression of hepatic fibrosis[12]. Qiu et al[9] found that activation of p38/MAPK promotes liver cell proliferation and chronic liver inflammation[13]. p38 MAPKs not only participate in cell proliferation and differentiation, but also in cell apoptosis. p38 MAPK influences the development of liver fibrosis through multiple pathways, including regulating the inflammatory response of the liver, inducing cell apoptosis, and regulating cytokine release[14]. To explore the potential mechanism of the Saf-Cal b in intervening hepatic fibrosis, we employed network pharmacology. Based on the “disease-gene-drug-target” interaction network, network pharmacology analyzes drug mechanisms at the systemic level. When predicting targets and pathways, it integrates multi-omics data to rapidly screen key targets, enrich related pathways, reduce experimental blindness, reveal the synergistic effects of drugs on multiple targets, and improve research efficiency[11]. This study explored the potential mechanism of the anti-hepatic fibrotic effect of the Saf-Cal b combination. The ultimate goal is to enhance the scientific understanding of Tibetan medicinal interventions for hepatic fibrosis and provide new perspectives for ethnopharmacological research.

The following drugs and reagents were used in this study: Saf (Jiuyuanci Traditional Chinese Medicine Co., Ltd., Bozhou City, China), Cal b (Tongrentang, Beijing, China), Biejia Ruangan tablet (BJRG; Furui Medical Technology Co., Ltd., Inner Mongolia, China), carbon tetrachloride (CCl4, Macklin, Shanghai, China), and olive oil (Macklin, Shanghai, China).

The solutions were prepared as follows. CCl4 solution: A mixture of CCl4 and olive oil was prepared at a 1:1 ratio. Saf solution: Five grams of Saf was added to deionized water; the sample was soaked, decocted twice in distilled water, and concentrated to 500 mL to obtain Saf solution (0.01 g/mL). The solution was stored in a refrigerator at 4 °C until use. Cal b solution: Cal b powder (0.35 g) was added to 100 mL of distilled water, sonicated, and mixed for 20 minutes to obtain the final solution (0.0035 g/mL). The solution was stored in a refrigerator at 4 °C until use. Saf-Cal b solution: Cal b powder (0.35 g) was added to 100 mL of 0.01 g/mL Saf solution. The mixture was ultrasonicated for 20 minutes. The solution was stored in a refrigerator at 4 °C until use. Referring to the drug ratio in classic Tibetan medicines for treating liver fibrosis (e.g., Ershiwuwei Songshi Wan), we set the ratio of Saf to Cal b at 1:1[7]. BJRG solution: BJRG (0.6 g) was added to 10 mL of 0.9% saline solution. The mixture was sonicated for 20 minutes and homogenized, yielding a final solution of 0.06 g/mL. The solution was stored in a refrigerator at 4 °C until use.

Sprague Dawley rats (male, 200 ± 20 g, n = 145) were purchased from SPF (Beijing, China) Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China), certification number: SCXK [jing] 2019-0010. The rats were housed in the Animal Experiment Center of Liangxiang Campus of Beijing University of Chinese Medicine, under specific pathogen-free conditions. The certificate number was BUCM-2023041904-2025. The animal protocol was designed to minimize pain or discomfort. Prior to experimentation, rats were acclimatized to laboratory conditions for one week, with controlled environment parameters: Temperature 23 ± 2 °C, 12 hours light/12 hours dark cycle, humidity 50% ± 10%, and ad libitum access to standard chow and tap water.

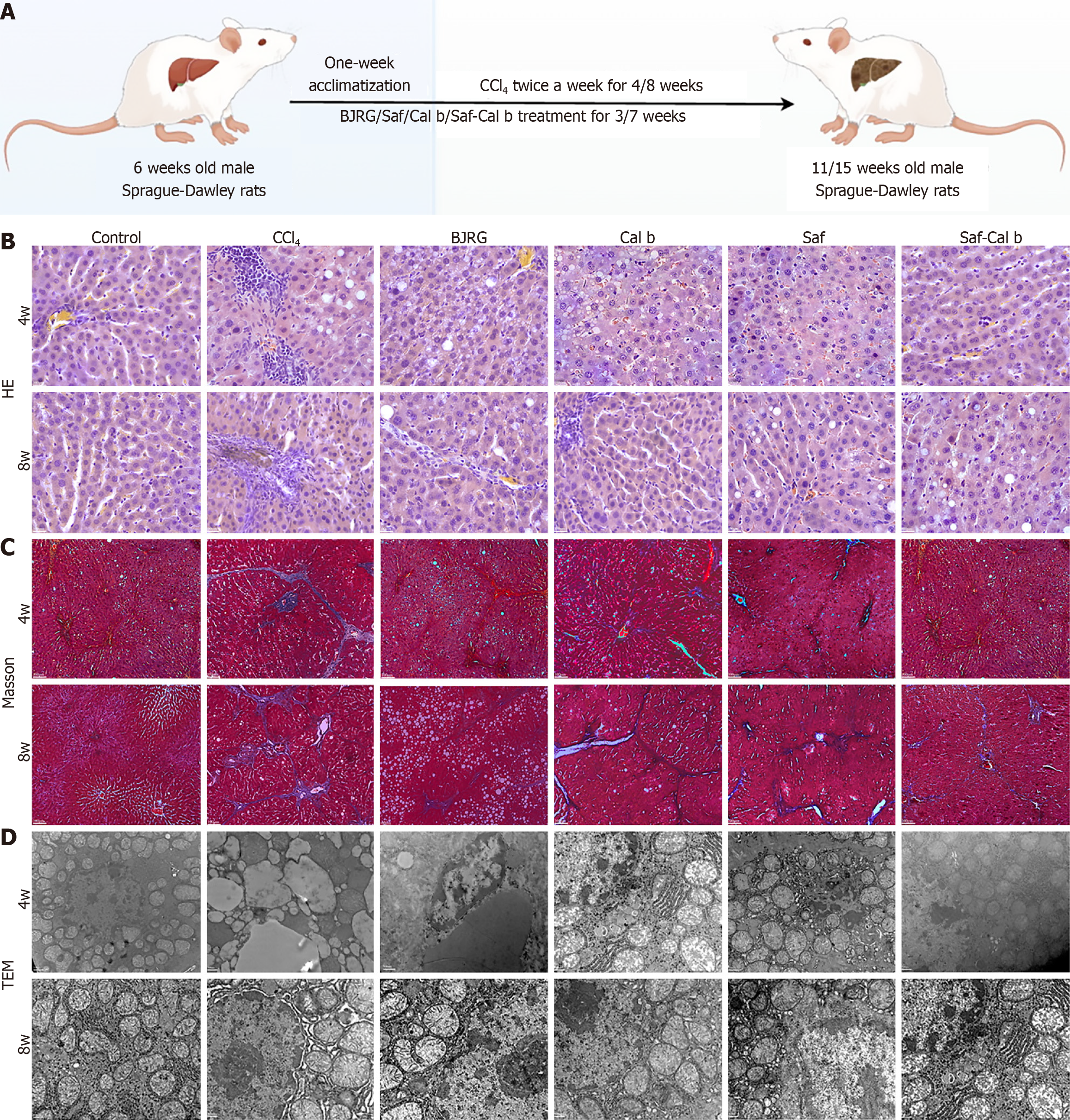

The rats were acclimatized for one week. On the second week, the rats were randomly allocated into the following groups: Control rats, CCl4 rats, BJRG rats, Saf rats, Cal b rats, and Saf-Cal b rats (10 rats/group). CCl4 (2 mL/kg, CCl4:olive oil = 1:1) was administered by gavage twice a week for 4 or 8 weeks to induce liver fibrosis in all groups except the control group[15]. Intragastric gavage was performed using straight gavage needles appropriate for the rat size (200 ± 20 g body weight: 16-gauge, 2-inch length, 2.0 mm ball diameter) with conscious animals to avoid unnecessary stress. Saf (0.1 g/kg), Cal b (0.035 g/kg), Saf 0.1 g/kg + Cal b 0.035 g/kg, and BJRG (0.6 g/kg) were administered by gavage after 1 week. BJRG was used as a positive control. Because a dose of Saf and Cal b has not been established, the dose was calculated following the recommended dose in the 2020 edition of the Chinese Pharmacopoeia[7]. Control and CCl4 rats received an identical volume of 0.9% saline (Figure 1A). At the end of weeks 4 and 8, rats were euthanized by intravenous injection of pentobarbital sodium (150 mg/kg) for tissue collection.

To evaluate liver histopathological changes (steatosis, lobular inflammation, hepatocellular ballooning), hematoxylin-eosin staining was used. Collagen accumulation, a key feature of liver fibrosis, was detected via Masson’s trichrome staining. Procedures followed previous methods with minor modifications[16]. Briefly, 4 μm paraffin-embedded liver sections were deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated through graded ethanol. For hematoxylin-eosin staining, sections were incubated in hematoxylin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, United States) for 5 minutes, differentiated in 1% hydrochloric acid-ethanol for 30 seconds, and counterstained with eosin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, United States) for 3 minutes. Masson staining used Weigert’s iron hematoxylin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, United States) for 10 minutes, Masson’s trichrome solution (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, United States) for 30 minutes, and 1% acetic acid differentiation for 1 minutes. Stained sections were dehydrated, cleared, mounted with neutral balsam, and imaged via Olympus BX53 (Tokyo, Japan) microscope.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) observed hepatocyte ultrastructures (mitochondrial morphology, endop

At the time of sampling, the wet weight of the liver and spleen, as well as the body weight of the rats, were measured. The liver and spleen indices were calculated using the formula: Organ index = organ wet weight (g)/body weight (g) × 100%. Serum was separated from whole blood by centrifugation. The serum levels of aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), and total bilirubin (TBIL) were determined using a fully automated biochemical analyzer. The hyaluronic acid (HA) content was measured with Mindray reagents using a fully automated chemiluminescent immunoassay analyzer. Liver hydroxyproline (HYP) levels were determined using the HYP assay kit (Nanjing Institute of Bioengineering, China), following the manufacturer’s instructions.

The levels of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin-1β (IL-1β), matrix metalloproteinase 2 (MMP-2) and tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases-1 (TIMP-1) in liver were measured with ELISA kits (Thermo Fisher, MA, United States; RayBiotech, GA, United States) following the manufacturers’ protocols. Glutathione peroxidase (GSH-PX) was evaluated using the GSH-PX assay kit (Nanjing Institute of Bioengineering, China). Malondialdehyde (MDA) levels were determined with the Lipid Peroxidation MDA Assay Kit (Beyotime, China). Liver superoxide dismutase (SOD) levels were determined with the SOD Assay Kit (Beyotime, China).

The chemical components of Saf and Cal b were retrieved from Traditional Chinese Medicine Systems Pharmacology Database and Analysis Platform (TCMSP) (http://tcmspw.com/tcmsp.php) and Bioinformatics Annotation Database for Molecular Mechanism of Traditional Chinese Medicine (BATMAN-TCM) (http://bionet.ncpsb.org/batman-tcm). From TCMSP, active components with oral bioavailability ≥ 30% and drug-likeness ≥ 0.18 (per absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion properties) and their targets were selected; from BATMAN-TCM, targets meeting a score cutoff ≥ 20 and adjusted P value < 0.05 were included, with literature supplementing missing components and targets.

Target proteins were standardized via UniProt (https://www.uniprot.org/). Duplicates were removed to establish a Saf-Cal b component-target database and imported into Cytoscape 3.8.2 to construct a drug-component-target network. Liver fibrosis-related genes were retrieved from GeneCards (https://www.genecards.org/) and OMIM (http://www.omim.org/) using “liver fibrosis”, “hepatic fibrosis”, and ”cirrhosis”. After UniProt standardization (Homo sapiens, excluding non-human targets), overlapping targets between Saf-Cal b and liver fibrosis were identified via Venn diagram analysis (https://bioinfogp.cnb.csic.es/tools/venny/index.html).

A protein-protein interactions (PPI) network diagram was generated for the overlapping targets identified above using the STRING database (https://string-db.org/cgi/). Cluster analysis was performed using the Cytoscape 3.8.2 software plug-in molecular complex detection (MCODE); the best protein module and hub gene was selected by the score of the node[17].

The Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery (http://david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov/) was used for visualization and analysis of Saf-Cal b target proteins. The target genes were pasted into the gene list section of Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery and labeled as “official gene symbol”. The species was set as “Homo sapiens” with a threshold of P < 0.05. The results obtained from Gene Ontology and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) analyses were analyzed.

The preparation of paraffin sections from liver tissue was performed as for histopathology. For antigen retrieval, the sections were boiled in 6 mmol/L citrate buffer (pH = 6.0) for 15 minutes and then cooled at room temperature for 20 minutes. To reduce non-specific binding, the sections were blocked with PBS containing 5% bovine serum albumin for 1 hour at room temperature. Immunofluorescence analysis was performed following previously described methods[16]. Antibodies against p38 MAPK (1:200, Cell Signaling Technology, MA, United States) and α-SMA (1:200, ProteinTech, IL, United States) were used as primary antibodies. α-SMA was used to label HSCs. For secondary antibody staining, immunoglobulin G-horseradish peroxidase (1:250; ZSGB-BIO, Beijing, China) was used, and the nucleus was stained with DAPI. The cells were observed and analyzed using a fluorescent inverted microscope.

Protein extracts were prepared from rat liver tissue using radio-immunoprecipitation assay buffer containing 1% phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride and 1% phosphatase and protease inhibitors. Western blot analysis was performed using standard methods. The primary antibodies included p-p38 (1:1000), p38 (1:1000), phosphorylated c-Jun N-terminal kinases (JNK) (1:1000), JNK (1:1000), phosphorylated extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) (1:2000), ERK (1:1000), and type I collagen (Col-I, 1:1000) (all from Cell Signaling Technology, MA, United States). Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (1:5000; LABLEAD, China) was used as a loading control.

Total RNA was extracted from liver tissue using the FastPure whole cell/tissue isolation kit (Accurate Biotech, Changsha, China). RNA was reverse transcribed into complementary DNA (cDNA) using a cDNA synthesis kit. cDNA was subjected to real-time polymerase chain reaction analysis on a Bio Rad CFX-96 system using a reverse transcription kit (Accurate Biotech, Changsha, China). The rat-specific polymerase chain reaction primers were purchased from Hunan Aikeli Bioengineering Company, China (Table 1).

| Target gene | Forward sequence (5′-3′) | Reverse sequence (5′-3′) |

| P38 MAPK | GGATATTTGGTCCGTGGGCT | TCATGGCTTGGCATCCTGTTA |

| ERK | CATGAAGGCCCGAAACTACCT | AGCCACTGGTTCATCTGTCG |

| JNK | CTCTCCAGCACCCGTACATC | TTGACAGACGGCGAAGAGAC |

| GAPDH | GGCAAGTTCAACGGCACAG | GCCAGTAGACTCCACGACAT |

All experimental data are presented as mean ± SD. Statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism software (version 9.5; GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, United States). Intergroup comparisons were conducted through one-way analysis of variance followed by Fisher’s least significant difference post hoc test. P < 0.05 indicated statistical significance. All in vivo experiments in this study included six biological replicates and three technical replicates per sample to ensure the reliability of the results. The statistical methods of this study were reviewed by Fang Liu from Beijing University of Chinese Medicine, who confirmed the appropriateness of the analytical approaches.

To evaluate the therapeutic effect of Saf-Cal b on liver fibrosis, we established liver fibrosis rat models. The rats were acclimatized for one week, followed by CCl4 gavage for 4 weeks or 8 weeks. After the first week of gavage, drug treat

Hematoxylin and eosin staining revealed preserved hepatic architecture in controls, with intact lobules, radial hepatic cords/sinusoids, and no inflammation (Figure 1B). The 4-week CCl4 rats developed perivenular inflammation, hepatocyte steatosis, and spotty necrosis, which progressed to confluent necrosis, lobular disorganization, and exacerbated inflammation by 8 weeks. In the group treated with Saf-Cal b, the hepatic tissue structure was arranged neatly, and the hepa

Ultrastructural analysis via TEM revealed marked mitochondrial injury of hepatocytes in CCl4 rats, including progressive swelling, cristae disruption, and quantitative reduction, with maximal severity at week 8 (Figure 1D). The combination therapy demonstrated superior cytoprotective effects compared with monotherapy, markedly attenuating mitochondrial damage and maintaining structural integrity.

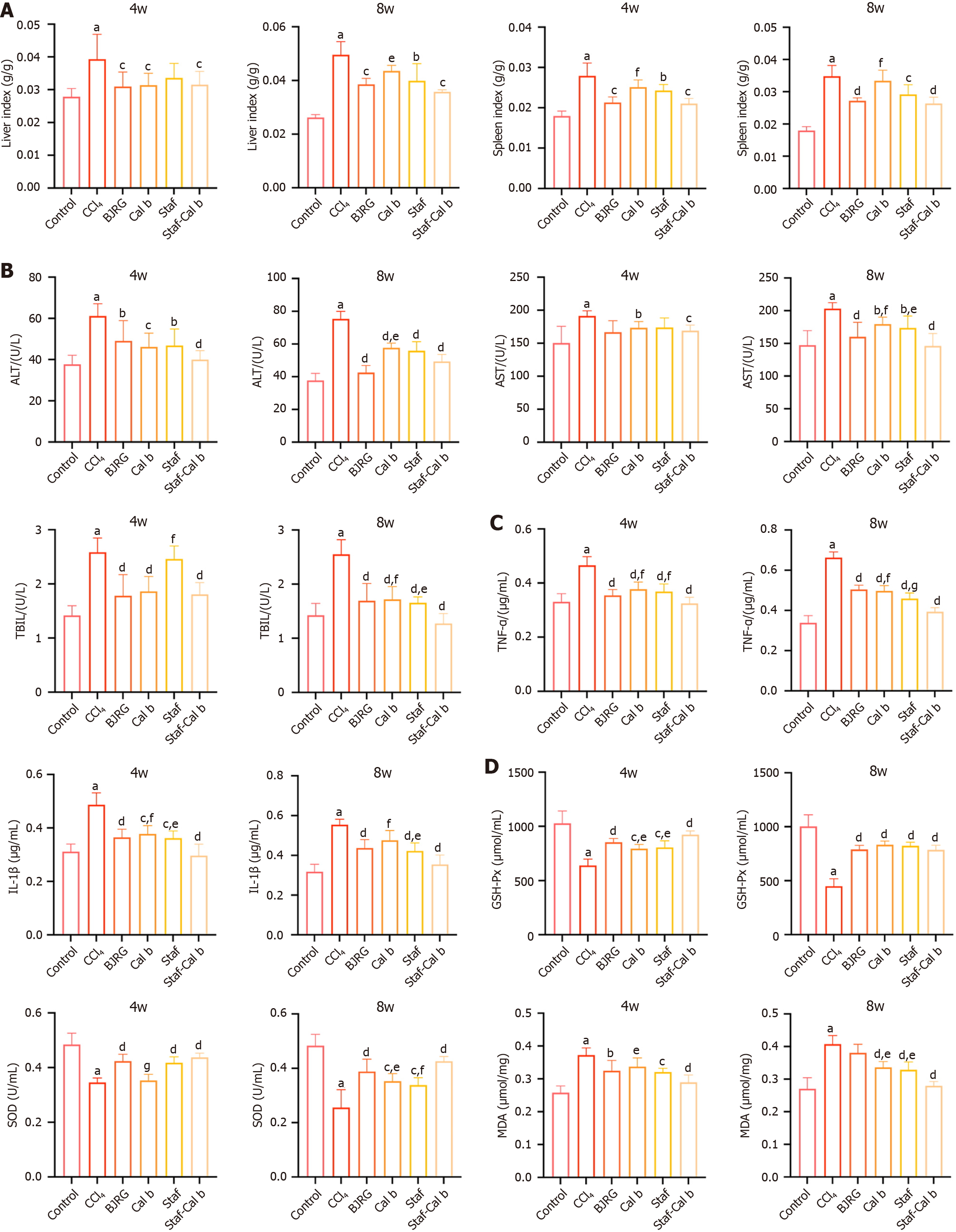

At both 4 weeks and 8 weeks, the liver index and spleen index of rats in the CCl4 group were significantly higher than those in the control group (P < 0.001; Figure 2A). Compared with results in the model group, the liver index and spleen index of animals treated with BJRG, the positive control, were significantly reduced at both 4 and 8 weeks. Similarly, compared with the model group, both Cal b and Saf monotherapy also reduced the liver index and spleen index at 8 weeks. Notably, at 4 weeks, the spleen index in the Saf-Cal b combination treatment group was significantly lower than that in the Cal b monotherapy group (P < 0.05). At 8 weeks, both the spleen index and liver index in the Saf-Cal b combination treatment group were significantly lower than those in the Cal b monotherapy group (P < 0.01).

After 4 and 8 weeks, the serum markers of liver injury (AST, ALT and TBIL) were significantly elevated in rats in the CCl4 group compared with the control group (P < 0.001; Figure 2B). At 4 weeks, the BJRG-positive control exhibited significant hepatoprotective effects, specifically manifested by a significant reduction in AST and TBIL levels (P < 0.05). The levels of liver enzymes in the Cal b treatment group were significantly reduced (P < 0.05). Notably, compared with results in the Saf group, the TBIL level in the Saf-Cal b combination treatment group was significantly lower (P < 0.05). By 8 weeks, the positive control drug BJRG showed significant hepatoprotective effects, as indicated by reduced levels of AST, ALT, and TBIL (P < 0.05). Similarly, both Cal b and Saf monotherapy also reduced the levels of liver injury markers at 8 weeks. At 8 weeks, the Saf-Cal b combination treatment group had lower levels of liver enzymes (AST, TBIL) com

Cytokine profiling by ELISA quantification revealed significant upregulation of pro-inflammatory mediators (TNF-α, IL-1β) in liver tissues of CCl4 model rats compared with controls at both 4 weeks and 8 weeks (Figure 2C; P < 0.001). The levels were significantly reduced in the BJRG-positive control group at both 4 weeks and 8 weeks. At 4 weeks, monotherapy with Saf and Cal b reduced the levels of TNF-α and IL-1β (P < 0.05). At 8 weeks, Saf and Cal b monotherapy led to reduced TNF-α levels, while IL-1β levels were reduced by monotherapy with Saf only (P < 0.05). Notably, signi

Oxidative stress evaluation revealed significant impairment of hepatic antioxidant defense mechanisms in CCl4 rats compared with controls, characterized by reduced GSH-PX and SOD activities, along with elevated MDA levels (P < 0.001; Figure 2D). The BJRG-positive control showed significantly increased GSH-PX activity and SOD at 4 weeks and 8 weeks, and significant improvement in MDA only at 4 weeks (P < 0.05). At 4 weeks, compared with the model group, all treatment groups showed significant improvements in GSH-PX and SOD levels (P < 0.05), while only the Saf group and the Saf-Cal b group showed significantly improved levels of MDA (P < 0.05). The Saf-Cal b monotherapy group showed significant improvement in all parameters compared with model rats at 8 weeks (P < 0.05). At 8 weeks, Saf-Cal b had similar effects on GSH-PX as monotherapy treatments, while it was more effective in increasing SOD and decreasing MDA compared with monotherapy treatments (P < 0.05).

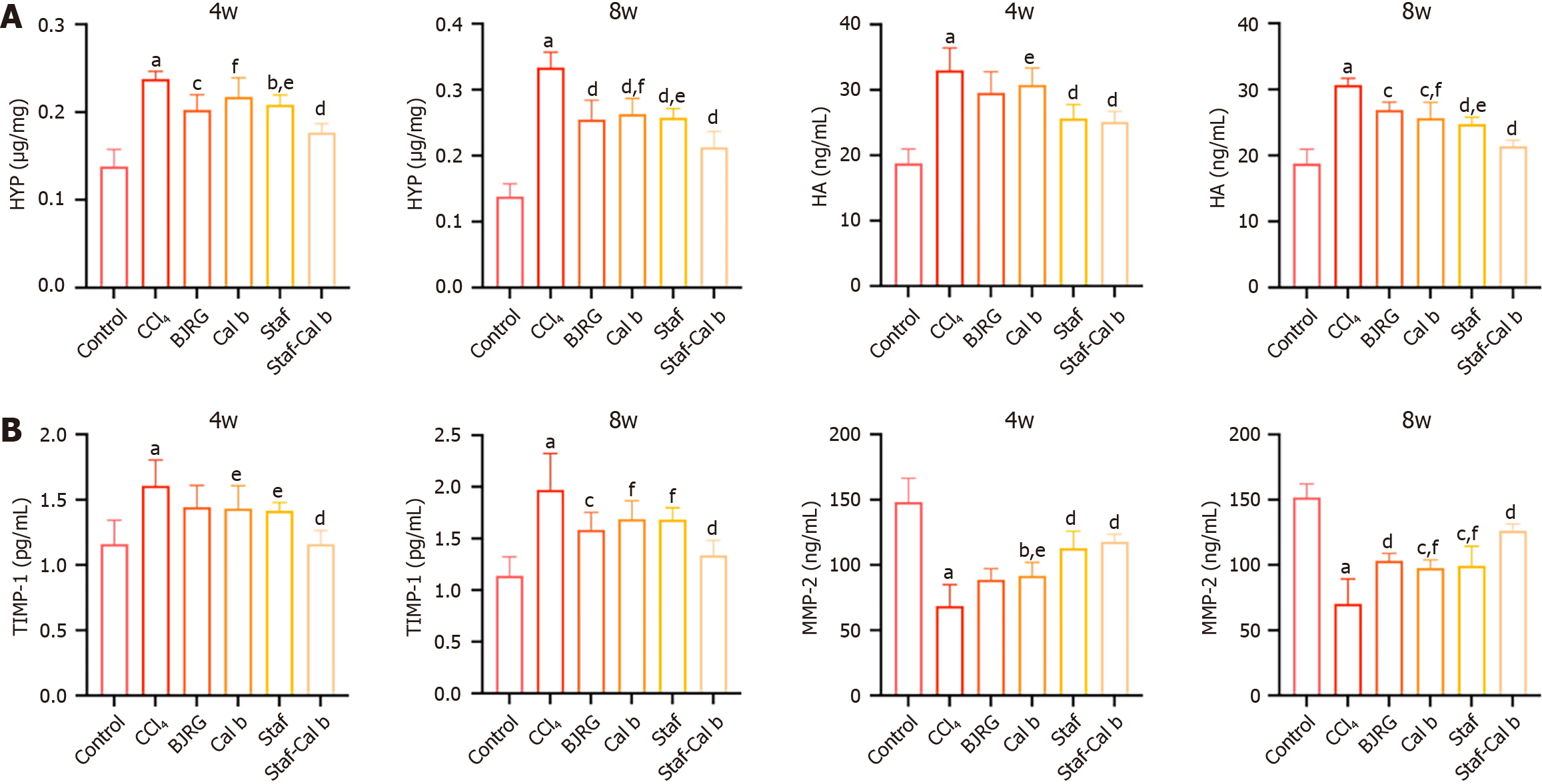

At both 4 weeks and 8 weeks, the level of HYP, a marker of collagen deposition, was significantly elevated in the CCl4 rat group (P < 0.001; Figure 3A). The HYP level in the BJRG-positive control group was significantly reduced at both 4 and 8 weeks. At 4 weeks, the HYP levels in all groups except for the Cal b group were significantly decreased (P < 0.05). Notably, at 4 weeks and 8 weeks, the HYP level in the Saf-Cal b combination treatment group was significantly lower than that in the Cal b monotherapy group and the Saf monotherapy group (P < 0.05).

Serological analysis revealed that the level of HA, which is positively correlated with HSC activation[18], was significantly increased in the serum of rats in the CCl4 model group (P < 0.001; Figure 3A). The HA level in the BJRG-positive control group was significantly reduced at 8 weeks, and the level was also significantly decreased after therapeutic intervention (P < 0.01). At 4 weeks, the HA content was significantly reduced in both the Saf monotherapy group and the Saf-Cal b combination treatment group compared with the CCl4 model group (P < 0.05). By 8 weeks, the HA levels in all drug-treated groups were significantly decreased (P < 0.01). Notably, the HA level in the Saf-Cal b combination treatment group was lower than that in the Saf monotherapy group and the Cal b monotherapy group (P < 0.05).

We next examined ECM production and degradation. TIMP-1 and MMP-2 precisely regulate ECM metabolism through a dynamic equilibrium in hepatic fibrosis[19,20]. TIMP-1 was elevated and MMP-2 was reduced in the liver tissue of CCl4 rats at both 4 and 8 weeks (P < 0.01; Figure 3B). At 8 weeks, the BJRG-positive control group showed a significant decrease in TIMP-1 levels and a significant increase in MMP-2 levels, suggesting improved deposition and balance of ECM in liver tissues (P < 0.05). The Cal b group, Saf group, and Saf-Cal b group all showed significantly downregulated TIMP-1 levels and significantly upregulated MMP-2 levels at 4 and 8 weeks (P < 0.05). Notably, at 4 weeks, the effect of the Saf-Cal b treatment on improving TIMP-1 levels was significantly superior to that of Saf and Cal b, and the effect on improving MMP-2 levels was significantly superior to that of Cal b (P < 0.05). Similarly, at 8 weeks, the efficacy of the Saf-Cal b combination on improving TIMP-1 and MMP-2 levels was also significantly superior to that of Saf and Cal b (P < 0.05). Together, these experimental results confirm that Saf-Cal b treatment has a significant ameliorative effect on hepatic fibrosis in rats.

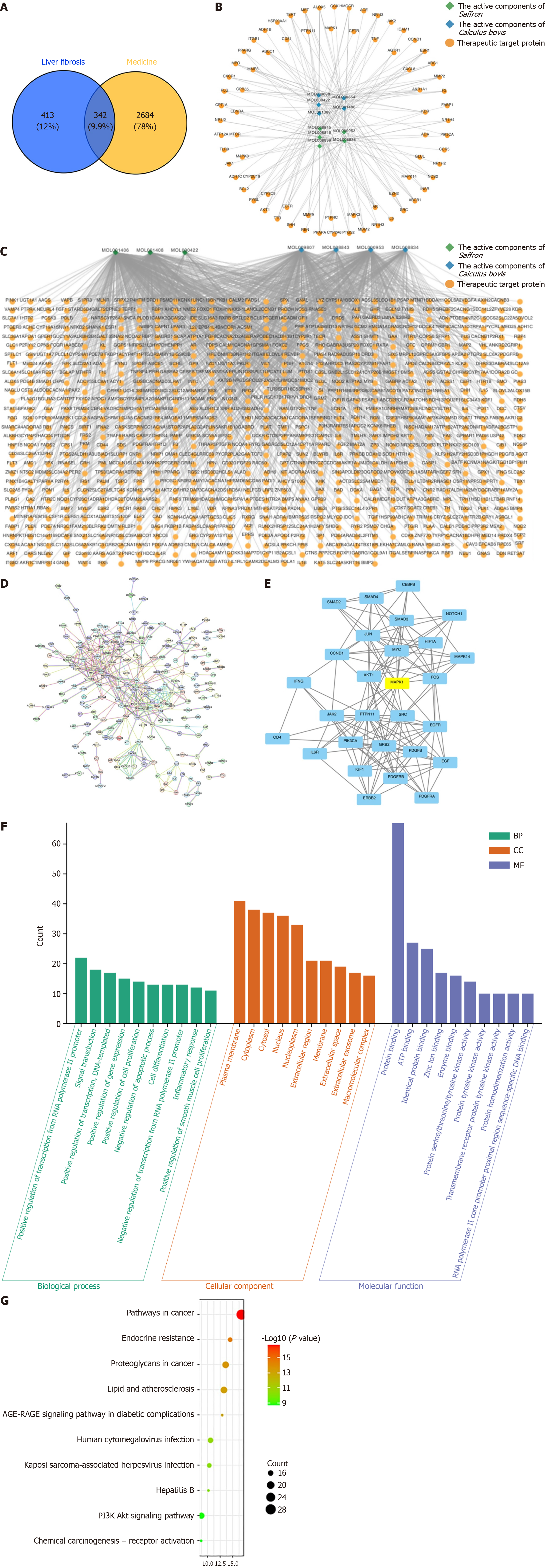

Our results indicate that Saf-Cal b treatment has a significant ameliorative effect on hepatic fibrosis. To investigate the mechanism of the anti-fibrotic action of the Saf-Cal b combination, we used network pharmacology methods to predict the potential key targets and signaling pathways. We first used network pharmacology prediction to identify potential targets of Saf and Cal b in anti-liver fibrosis. A total of 3026 potential targets of Saf and Cal b were collected using the TCMSP database and BAT-MAN database (Table 2). We also collected 755 liver fibrosis-related targets using the Genecard database and OMIM database. Venn diagram analysis revealed 342 intersecting targets between the targets of Saf and Cal b and liver fibrosis-related targets (Figure 4A). On the basis of these targets, we constructed the “plant active ingredient-target” network diagram of Saf-Cal b (Figure 4B and C). We constructed a PPI network of the interactions of the intersecting targets (Figure 4D).

| Medicine | Component | Component ID | Database |

| Saffron | Quercetin | MOL000098 | TCMSP |

| Kaempferol | MOL000422 | ||

| Isorhamnetin | MOL000354 | ||

| Crocetin | MOL001406 | ||

| Crocetin | MOL001406 | BATMAN-TCM | |

| Kaempferol | MOL000422 | ||

| Picrocrocin | MOL001408 | ||

| Calculus bovis | Bilirubin | MOL008838 | TCMSP |

| Methyl desoxycholate | MOL008839 | ||

| ZINC01280365 | MOL008846 | ||

| CLR | MOL000953 | ||

| Cherianoine | MOL008843 | BATMAN-TCM | |

| Bilicerdin | MOL008834 | ||

| Cholic Acid | MOL009807 | ||

| CLR | MOL000953 |

The 342 targets were analyzed for protein interaction relationships (confidence > 0.9), and the protein interaction relationships were expressed in Cytoscape 3.8.2. Cluster analysis was performed using the MCODE plugin, and the highest score clustering network was obtained using K-core values (Figure 4E). MCODE analysis results showed that MAPK, IL-6R, mothers against decapentaplegic homolog 3 (SMAD3), EGF, CEBPB, IFNG, SMAD2, ERBB2, NOTCH1, CD4, IGF1, JUN, JAK2, MAPK1, SMAD4, AKT1, CCND1, HIF1A, GRB2, PDGFRB, FOS, PDGFB, SRC, PTPN11, EGFR, PIK3CA, MYC, and PDGFRA genes were the hub genes for clustering. Integrated network pharmacology analysis of PPI networks and MCODE module clustering identified the MAPK signaling pathway (highest K-core value) as the central potential mechanism underlying the anti-fibrotic effects of the Saf-Cal b combination (Figure 4E). The MAPK cascade critically modulates transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β)/SMAD3 signaling transduction, thereby driving HSC activation and ECM deposition, which are central to the pathogenesis of liver fibrosis[12,21]. Thus, we focused on the MAPK signaling pathway for in-depth mechanistic investigation.

Gene Ontology enrichment analysis of the 342 target proteins was conducted using the Majorbio Cloud Platform with a significance threshold of P < 0.001. The results identified 114 biological processes, 15 cellular components, and 21 molecular functions with significant enrichment. The top 10 ranked terms per category revealed that biological processes predominantly involved transcriptional regulation (RNA polymerase II promoter), signal transduction, and modulation of cell proliferation/apoptosis; cellular components was enriched in cytoplasmic, plasma membrane, nuclear, and extracellular compartments; while molecular function highlighted critical functional domains, including protein kinase activity (serine/threonine/tyrosine), ATP zinc ion binding, and DNA/enzyme interactions (Figure 4F).

KEGG pathway enrichment analysis identified 44 significantly enriched signaling pathways (P < 0.001). The top 10 entries (ranked by descending gene count) included pathways in cancer, endocrine resistance, proteoglycans in cancer, lipid metabolism and atherosclerosis, advanced glycation end products-receptor for advanced glycation end products signaling in diabetic complications, human cytomegalovirus infection, Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus infection, hepatitis B infection, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/protein kinase B signaling pathway, and chemical carcinogenesis-receptor activation (Figure 4G).

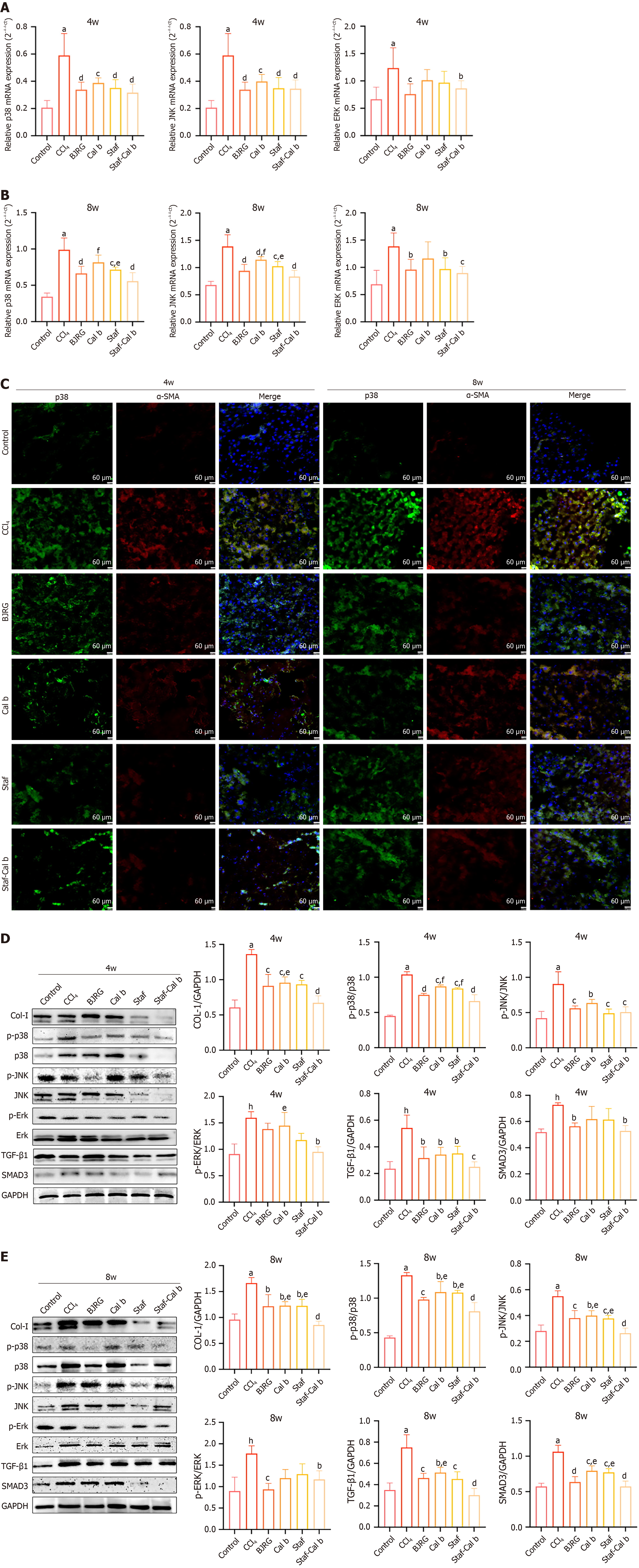

Next, we evaluated the effects of Saf, Cal b, and Saf-Cal b on the MAPK pathway. Quantitative real time polymerase chain reaction analysis showed that the mRNA levels of p38 MAPK, JNK, and ERK in the liver tissues of CCl4 rats were all increased at 4 weeks and 8 weeks (P < 0.001; Figure 5A and B). In the BJRG-positive control group, the mRNA levels of these factors were significantly decreased at both 4 weeks and 8 weeks (P < 0.05). The Cal b group, Saf group, and Saf-Cal b group also showed significantly downregulated p38 MAPK and JNK mRNA levels at 4 weeks and 8 weeks (P < 0.05). While the mRNA level of ERK in the Saf-Cal b group was significantly downregulated at 4 weeks (P < 0.05), monotherapy treatment had no significant effect. At 8 weeks, Saf and Saf-Cal b treatments significantly downregulated ERK mRNA (P < 0.05). Notably, compared with Saf or Cal b monotherapy, the Saf-Cal b regimen had a superior effect on downregulating p38 and JNK mRNA levels in CCl4 rats (P < 0.05).

Activation of HSCs is a central event in hepatic fibrosis, with α-SMA serving as a classical marker of HSC activation[22]. Following activation, HSCs exhibit massive secretion of ECM components. Immunofluorescence analysis de

Col-I has been established as a core pathological biomarker in hepatic fibrosis[23]. Western blot analysis revealed that while the protein expression of Col-I was significantly elevated in CCl4-induced fibrotic rats at both 4 weeks and 8 weeks (P < 0.01), Col-I levels were significantly reduced in all treatment groups (P < 0.05; Figure 5D and E). The Col-I protein level in the Saf-Cal b group was significantly lower than that in the Cal b group at 4 weeks and 8 weeks (P < 0.05).

Additionally, the phosphorylated protein levels of p38, JNK, and ERK in CCl4 model rats were significantly upre

p38 MAPK may directly regulate HSC activation, thereby influencing hepatic fibrogenesis[9]. Structural biology studies revealed significant conformational homology between the ATP-binding domain of the TGF-β type I receptor and the kinase domain of p38 MAPK[24]. Inhibition of p38 MAPK signaling leads to downregulation of the TGF-β/SMAD3 pathway[25]. Our experimental data showed that the protein expression levels of TGF-β and SMAD3 were significantly elevated in CCl4-induced fibrotic rats at both 4 weeks and 8 weeks (P < 0.01; Figure 5E). The protein expression levels of TGF-β in all drug-treated groups were significantly downregulated at 4 weeks and 8 weeks compared with levels in the CCl4 model group (P < 0.05). While SMAD3 protein was induced in CCl4 model rats, Saf-Cal b treatment exerted a significant inhibitory effect on SMAD3 levels at 4 weeks (P < 0.05). Notably, at 8 weeks, TGF-β protein expression was significantly lower in the Saf-Cal b group compared with the Cal b group, and SMAD3 protein expression was significantly lower than that in the Saf and Cal b groups (P < 0.05).

Liver fibrosis is a common pathological stage in most chronic liver diseases, representing a significant global health issue, with no targeted therapeutic options currently available[26]. Recent studies have increasingly demonstrated the potential of Tibetan medicine in the treatment of liver fibrosis[16]. In Tibetan medicine theory, the Saf-Cal b combination is the predominant therapeutic pairing for chronic hepatic diseases. However, the pharmacological mechanisms of this drug combination remain unclear.

Saf-Cal b is a commonly used drug pair in Tibetan medicine for treating chronic liver diseases. Because of the scarcity and high cost of natural bezoar, substitutes such as artificially synthesized derivatives and bioengineered bezoar preparations have been developed. Artificially synthesized derivatives show similar efficacy and replicate the main components of natural bezoar, while bioengineered preparation balances yield and quality. Synthetic preparations, with high cost-effectiveness and stable efficacy, are highly recognized in Tibetan clinical practice; thus, artificial bezoar was used in this experiment.

The CCl4-induced toxic liver fibrosis rat model simulates the pathological state of human liver fibrosis, resulting in mitochondrial damage of hepatocytes, decreased ATP levels, and increased reactive oxygen species, thereby triggering oxidative stress[27]. This model stimulates the production of inflammatory factors in the liver, further igniting the inflammatory response and promoting the progression of liver fibrosis[28]. This study systematically evaluated the temporal therapeutic effects of the combination of Saf and Cal b in the CCl4-induced liver fibrosis rat model at two time points (4 weeks and 8 weeks).

In the Guidelines for the Integrated Traditional Chinese and Western Medicine Treatment of Liver Diseases, BJRG is recommended for the treatment of liver cirrhosis induced by hepatitis B[29]. Therefore, we used BJRG as a positive control drug in this study. Our experimental results revealed that both BJRG and Saf-Cal b exert anti-hepatic fibrosis effects, and there are both similarities and differences in their anti-hepatic fibrosis mechanisms. BJRG and Saf-Cal b exerted highly consistent effects at the TGF-β/SMAD3 pathway level; this is consistent with the conclusion from Yang et al’s study[27]. BJRG and Saf-Cal b also exhibit differences in their mechanisms of action against liver fibrosis. At 4 weeks, BJRG had no effects on rat AST, HA, TIMP-1, and MMP-2 levels or ERK phosphorylation; at 8 weeks, it still failed to significantly improve rat MDA levels. In contrast, Saf-Cal b exerted a regulatory effect on all the above factors[30].

Histopathological assessment revealed that, compared with monotherapy, the Saf-Cal b combination resulted in significant improvements in liver structure, characterized by alleviated fatty degeneration and necrosis of hepatocytes and reduced ECM accumulation. The change in HYP and HA levels, markers of liver fibrosis severity, confirmed the anti-liver fibrosis effect of Saf-Cal b, and the effects were better than those of monotherapy treatments. Furthermore, Saf-Cal b effectively restored ECM homeostasis, as evidenced by a rebalancing of TIMP-1 and MMP-2. Lipid peroxidation reaction in chronic liver injury is an important inducer of liver fibrosis[31]. Notably, Saf-Cal b demonstrated a stronger hepatoprotective effect and alleviated hepatic oxidative damage, with significant reductions in AST, ALT, and TBIL levels, enhancing GSH-PX and SOD activities while reducing MDA levels, indicating that Saf-Cal b possesses superior anti-fibrotic potential. From the change of inflammatory factors and oxidative stress indicators, the Saf-Cal b combination demonstrated a more significant therapeutic effect at the 8-week time point than at the 4-week time point, which indicated better effects over a longer treatment time. These results provide insights into why the Saf-Cal b combination was the most common combination treatment for chronic liver disease in Tibetan medicine.

To clarify the molecular mechanisms by which the Saf-Cal b regulates liver fibrosis, we conducted network pharmacology analyses. The analysis of both the predicted targets and signaling pathways served as a foundation for the subsequent validation experiments. From the pathway results, we observed a low correlation between certain top-ranked pathways and hepatic fibrosis. Consequently, we decided to prioritize the target data, supplemented by insights from published mechanisms. Since a detailed examination of these unrelated pathways was beyond the primary scope of this study, we deem it prudent to reserve them for future research. Using PPI and MCODE analyses, MAPK signaling was identified as a potential mechanism underlying the anti-fibrotic effects of the Saf-Cal b combination. KEGG pathway enrichment analysis revealed that the anti-fibrotic mechanisms of Saf-Cal b involve multiple pathways. Notably, substantial evidence indicates close associations between MAPK signaling and the identified pathways[32,33]. Our results showed that as liver fibrosis progressed, the expression of p38 MAPK and α-SMA in the liver tissues was significantly upregulated, accompanied by the activation of HSCs. Following Saf-Cal b intervention, the expression of p38 MAPK was significantly downregulated, effectively inhibiting HSC activation[34]. Multiple studies have indicated that p38 MAPK can influence HSC activation by regulating the downstream TGF-β signaling pathway, thereby promoting the progression of liver fibrosis[35,36]. Our results showed that Saf-Cal b significantly inhibits the mRNA and protein expression levels of p38 MAPK, JNK, and ERK and their phosphorylation. These changes in kinase activity may further downregulate the TGF-β/SMAD3 pathway, ultimately directly influencing the development of liver fibrosis.

Our study also generated some notable results. At the 4-week timepoint, Cal b treatment exhibited relative superiority in improving serum liver function parameters, whereas Saf monotherapy exerted more pronounced effects on restoring hepatic fibrotic metabolic homeostasis. The Saf-Cal b combination therapy exhibited enhanced efficacy over mono

Our experimental data demonstrate that Saf-Cal b exerts significant anti-fibrotic effects against hepatic fibrosis. The therapeutic efficacy of Saf-Cal b treatment surpassed that of Saf or Cal b monotherapy. Further experimental results suggested that the Saf-Cal b combination simultaneously inhibited the p38 MAPK and TGF-β/SMAD pathways, thereby intervening in the progression of hepatic fibrosis. Finally, we present a concise overview of the core research framework of this study in Figure 6.

| 1. | Devarbhavi H, Asrani SK, Arab JP, Nartey YA, Pose E, Kamath PS. Global burden of liver disease: 2023 update. J Hepatol. 2023;79:516-537. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1224] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 2. | Khanam A, Saleeb PG, Kottilil S. Pathophysiology and Treatment Options for Hepatic Fibrosis: Can It Be Completely Cured? Cells. 2021;10:1097. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 18.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Yip TC, Wong VW, Wong GL. Does hepatic steatosis impact chronic hepatitis B? Hepatology. 2023;77:1478-1481. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Jia Z, Zheng Y, Fu S, Qu J, Tian J, Qu W, Mei Z. Tibetan Medicine Shi-Wei-Gan-Ning-San Alleviates Carbon Tetrachloride-Induced Chronic Liver Injury by Inhibiting TGF-β1 in Wistar Rats. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2022;2022:2011876. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Tsering BZ, Gu J, Shi ZL. [To explore the compatibility characteristics of tibetan medicine 25 flavor turquoise pills and the core combination components in the treatment of liver diseases]. Shijie Kexue Jishu-Zhongyao Xiandaihua. 2018;20:1840-1845. |

| 6. | Li Q, Li HJ, Xu T, Du H, Huan Gang CL, Fan G, Zhang Y. Natural Medicines Used in the Traditional Tibetan Medical System for the Treatment of Liver Diseases. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Committee National Pharmacopoeia. [Pharmacopoeia of People’ Republic of China]. Beijing: China Medical Science Press, 2020: 72-134. |

| 8. | Shahi T, Assadpour E, Jafari SM. Main chemical compounds and pharmacological activities of stigmas and tepals of ‘red gold’; saffron. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2016;58:69-78. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Dong W, Kong M, Liu H, Xue Y, Li Z, Wang Y, Xu Y. Myocardin-related transcription factor A drives ROS-fueled expansion of hepatic stellate cells by regulating p38-MAPK signalling. Clin Transl Med. 2022;12:e688. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Baghaei K, Mazhari S, Tokhanbigli S, Parsamanesh G, Alavifard H, Schaafsma D, Ghavami S. Therapeutic potential of targeting regulatory mechanisms of hepatic stellate cell activation in liver fibrosis. Drug Discov Today. 2022;27:1044-1061. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Jiang N, Zhang J, Ping J, Xu L. Salvianolic acid B inhibits autophagy and activation of hepatic stellate cells induced by TGF-β1 by downregulating the MAPK pathway. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:938856. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Qiu B, Lawan A, Xirouchaki CE, Yi JS, Robert M, Zhang L, Brown W, Fernández-Hernando C, Yang X, Tiganis T, Bennett AM. MKP1 promotes nonalcoholic steatohepatitis by suppressing AMPK activity through LKB1 nuclear retention. Nat Commun. 2023;14:5405. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Wang R, Zhang H, Wang Y, Song F, Yuan Y. Inhibitory effects of quercetin on the progression of liver fibrosis through the regulation of NF-кB/IкBα, p38 MAPK, and Bcl-2/Bax signaling. Int Immunopharmacol. 2017;47:126-133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 12.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Chen Y, Li Q, Ren S, Chen T, Zhai B, Cheng J, Shi X, Song L, Fan Y, Guo D. Investigation and experimental validation of curcumin-related mechanisms against hepatocellular carcinoma based on network pharmacology. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2022;23:682-698. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Liu H, Zhang Z, Hu H, Zhang C, Niu M, Li R, Wang J, Bai Z, Xiao X. Protective effects of Liuweiwuling tablets on carbon tetrachloride-induced hepatic fibrosis in rats. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2018;18:212. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Wang S, Ye F, Ren Q, Sun S, Xia W, Wang Z, Guo H, Li H, Zhang S, Lowe S, Chen M, Du Q, Weihong Li. The anti-liver fibrosis effect of Tibetan medicine (Qiwei Tiexie capsule) is related to the inhibition of NLRP3 inflammasome activation in vivo and in vitro. J Ethnopharmacol. 2024;319:117283. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Guo WL, Jiang HJ, Li YR, Yang JL, Chen YC. Medication Rules of Hub Herb Pairs for Insomnia and Mechanism of Action: Results of Data Mining, Network Pharmacology, and Molecular Docking. Chin Med Sci J. 2024;39:249-260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Lichtinghagen R, Pietsch D, Bantel H, Manns MP, Brand K, Bahr MJ. The Enhanced Liver Fibrosis (ELF) score: normal values, influence factors and proposed cut-off values. J Hepatol. 2013;59:236-242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 208] [Cited by in RCA: 277] [Article Influence: 21.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (10)] |

| 19. | Naim A, Pan Q, Baig MS. Matrix Metalloproteinases (MMPs) in Liver Diseases. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2017;7:367-372. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 12.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Duarte S, Baber J, Fujii T, Coito AJ. Matrix metalloproteinases in liver injury, repair and fibrosis. Matrix Biol. 2015;44-46:147-156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 260] [Cited by in RCA: 367] [Article Influence: 33.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Wang H, Che J, Cui K, Zhuang W, Li H, Sun J, Chen J, Wang C. Schisantherin A ameliorates liver fibrosis through TGF-β1mediated activation of TAK1/MAPK and NF-κB pathways in vitro and in vivo. Phytomedicine. 2021;88:153609. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Rippe RA, Brenner DA. From quiescence to activation: Gene regulation in hepatic stellate cells. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:1260-1262. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Zhou L, Liang Q, Li Y, Cao Y, Li J, Yang J, Liu J, Bi J, Liu Y. Collagenase-I decorated co-delivery micelles potentiate extracellular matrix degradation and hepatic stellate cell targeting for liver fibrosis therapy. Acta Biomater. 2022;152:235-254. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Laping NJ, Grygielko E, Mathur A, Butter S, Bomberger J, Tweed C, Martin W, Fornwald J, Lehr R, Harling J, Gaster L, Callahan JF, Olson BA. Inhibition of transforming growth factor (TGF)-beta1-induced extracellular matrix with a novel inhibitor of the TGF-beta type I receptor kinase activity: SB-431542. Mol Pharmacol. 2002;62:58-64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 534] [Cited by in RCA: 519] [Article Influence: 21.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Tsukada S, Westwick JK, Ikejima K, Sato N, Rippe RA. SMAD and p38 MAPK signaling pathways independently regulate alpha1(I) collagen gene expression in unstimulated and transforming growth factor-beta-stimulated hepatic stellate cells. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:10055-10064. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in RCA: 147] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Xu JH, Yu YY, Xu XY. Management of chronic liver diseases and cirrhosis: current status and future directions. Chin Med J (Engl). 2020;133:2647-2649. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Ezhilarasan D, Karthikeyan S, Najimi M, Vijayalakshmi P, Bhavani G, Jansi Rani M. Preclinical liver toxicity models: Advantages, limitations and recommendations. Toxicology. 2025;511:154020. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Unsal V, Cicek M, Sabancilar İ. Toxicity of carbon tetrachloride, free radicals and role of antioxidants. Rev Environ Health. 2021;36:279-295. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 155] [Article Influence: 31.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Hong M, Li S, Tan HY, Wang N, Tsao SW, Feng Y. Current Status of Herbal Medicines in Chronic Liver Disease Therapy: The Biological Effects, Molecular Targets and Future Prospects. Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16:28705-28745. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Yang FR, Fang BW, Lou JS. Effects of Fufang Biejia Ruangan pills on hepatic fibrosis in vivo and in vitro. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:5326-5333. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Dat NQ, Thuy LTT, Hieu VN, Hai H, Hoang DV, Thi Thanh Hai N, Thuy TTV, Komiya T, Rombouts K, Dong MP, Hanh NV, Hoang TH, Sato-Matsubara M, Daikoku A, Kadono C, Oikawa D, Yoshizato K, Tokunaga F, Pinzani M, Kawada N. Hexa Histidine-Tagged Recombinant Human Cytoglobin Deactivates Hepatic Stellate Cells and Inhibits Liver Fibrosis by Scavenging Reactive Oxygen Species. Hepatology. 2021;73:2527-2545. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Zhu Y, Zhao Y, Ning Z, Deng Y, Li B, Sun Y, Meng Z. Metabolic self-feeding in HBV-associated hepatocarcinoma centered on feedback between circulation lipids and the cellular MAPK/mTOR axis. Cell Commun Signal. 2024;22:280. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Jang H, Ham J, Song J, Song G, Lim W. Alpinumisoflavone Impairs Mitochondrial Respiration via Oxidative Stress and MAPK/PI3K Regulation in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells. Antioxidants (Basel). 2022;11:1929. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Szuster-Ciesielska A, Mizerska-Dudka M, Daniluk J, Kandefer-Szerszeń M. Butein inhibits ethanol-induced activation of liver stellate cells through TGF-β, NFκB, p38, and JNK signaling pathways and inhibition of oxidative stress. J Gastroenterol. 2013;48:222-237. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Sun YM, Wu Y, Li GX, Liang HF, Yong TY, Li Z, Zhang B, Chen XP, Jin GN, Ding ZY. TGF-β downstream of Smad3 and MAPK signaling antagonistically regulate the viability and partial epithelial-mesenchymal transition of liver progenitor cells. Aging (Albany NY). 2024;16:6588-6612. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Ji J, Yu Q, Dai W, Wu L, Feng J, Zheng Y, Li Y, Guo C. Apigenin Alleviates Liver Fibrosis by Inhibiting Hepatic Stellate Cell Activation and Autophagy via TGF-β1/Smad3 and p38/PPARα Pathways. PPAR Res. 2021;2021:6651839. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/